Abstract

Background:

Tumor board conferences are used by oncologic specialists to review patient cases, exchange knowledge, and discuss options for cancer management. These multidisciplinary meetings are often a cornerstone of treatment at leading cancer centers, and required for accreditation by certain groups, such as the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer. Little is known regarding skin cancer tumor board conferences. The objective of this study was to characterize the structure, function and impact of existing skin cancer tumor board conferences in the U.S.

Patients and Methods:

A cross-sectional online survey was administered to physician leaders of skin cancer tumor board conferences at NCI-designated Comprehensive and Clinical Cancer Centers.

Results:

Of the 59 centers successfully contacted, 14 (24%) reported not having a conference where skin cancer cases were discussed. Forty-five institutions identified 53 physician leaders. Thirty-eight physicians (72%) completed the survey. Medical and surgical oncologists comprised half of the meeting leaders and dermatologists led one-third of the meetings. Tumor board conference had a moderate to significant impact on patient care according to 97% of respondents. All respondents indicated that the meeting enhanced communication among physicians, and was an opportunity for involved specialists and professionals to discuss cases together. The most frequently cited barrier to organizing tumor board conference was finding a common available date and time for attendees (62%). The most common suggestion for improvement was an increase in attendance, specialists, and/or motivation.

Discussion:

Results showed overall consistency in meeting structure, but variability in function, which may be a reflection of institutional resources and investment in the conference. Future directions include defining metrics to evaluate changes in diagnosis or management plan after tumor board discussion, attendance, clinical trial enrollment, and cost analysis.

Conclusions:

The results of this survey may aid other institutions striving to develop and refine skin cancer tumor board conferences.

Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the United States (US). The incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), such as basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), has increased from an estimated 3.5 million cases in 2006 to 5.4 million cases in 2012.1,2 Additionally, the incidence of melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma is also on the rise.3,4 The majority of skin cancers are detected early and are easily cured with a single treatment modality. However, a subset of patients presents with recurrent and/or advanced skin cancer and require the expertise of several specialists for optimal management. Multidisciplinary team meetings, also known as tumor board conferences, provide an opportunity to discuss the full spectrum of diagnostic, therapeutic and social issues related to an individual patient and develop a coordinated plan for patients with complex skin cancer.5

Multidisciplinary management is often a cornerstone of treatment at leading cancer centers. In fact, a multidisciplinary tumor board conference is required for accreditation by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer®.6 In other countries, such as the United Kingdom (UK), multidisciplinary team meetings are an essential component of the national standard for cancer care.7 Multidisciplinary tumor board conferences have demonstrated value in the management of patients with various cancers, including breast, gynecologic, thoracic, and upper gastrointestinal malignancies.8–11 Tumor board conferences provide an opportunity to discuss treatment options among different specialists who offer a range of perspectives and management approaches. A study of the impact of a breast cancer tumor board conference found management plans are commonly modified to reflect the most current data and literature.8 Tumor board conferences also encourage adherence to clinical practice guidelines, improve communication among physicians, and provide a forum for continuing medical education.12

Despite the general benefits of tumor board conferences, there is a paucity of published information regarding the structure and function of these multidisciplinary meetings among skin cancer specialists. The current study aimed to characterize existing skin cancer tumor board conferences at NCI-designated Cancer Centers across the US, with the goal of better understanding institutional practices across the country.

Methods

In a cross-sectional study design, an online survey was created on SurveyMonkey®. The survey consisted of 26 questions that were formulated after a comprehensive literature review and discussion among the authors (Appendix 1). The questions were grouped into three categories: (1) structure, (2) function, and (3) impact. Structure included information regarding the attendees and format of the conference. Function was defined as conference activities and actions. Questions regarding impact addressed the value of the conference, as well as barriers. The survey was vetted internally by a multidisciplinary group of physicians involved in skin cancer management at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The study was determined to be exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of MSKCC.

In the US, the top 4% of cancer research institutions (n=69) are recognized as National Cancer Institute (NCI) – designated Cancer Centers. A subset of these institutions (n=49) also demonstrate expertise in transdisciplinary research, earning the designation of a Comprehensive Cancer Center.13 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) is another alliance of 27 leading cancer centers in the United States that have “pioneered the concept of the multidisciplinary team approach to patient care”.14 Of the 69 NCI-designated Cancer Centers, 7 are Basic Laboratory Cancer Centers that do not provide patient treatment, and therefore, were not included in the study. The remaining 62 centers (including all 27 NCCN Member Institutions) were contacted initially by telephone in order to determine whether there was an existing skin cancer tumor board conference. If an institution had one or more skin cancer tumor boards, the primary physician leader of the tumor board was administered the survey by e-mail. The survey was e-mailed up to three times to maximize response rate. If there was no response after the third attempt, the center was excluded.

Results

Target Study Population

Of the 62 NCI-designated Comprehensive and Clinical Cancer Centers, including our own institution, we were unable to contact 3 centers (5%) despite multiple attempts. Of the 59 centers successfully contacted, 14 (24%) reported not having a conference where skin cancer cases were discussed. Three centers (5%) did not have skin cancer-specific conferences, but did discuss skin cancer cases in a conference along with other cancers (i.e., sarcoma, head and neck cancer), and were included in the study. Seven cancer centers (12%) had more than one skin cancer tumor board conference (i.e., a melanoma conference and non-melanoma skin cancer conference).

Forty-five institutions identified 53 physician leaders for skin cancer conferences. In order to be included in the study analysis, at least 80% of the survey questions had to be completed. Of the 53 physician leaders, 38 (72%) completed the survey and were included in the final analysis.

Conference Structure

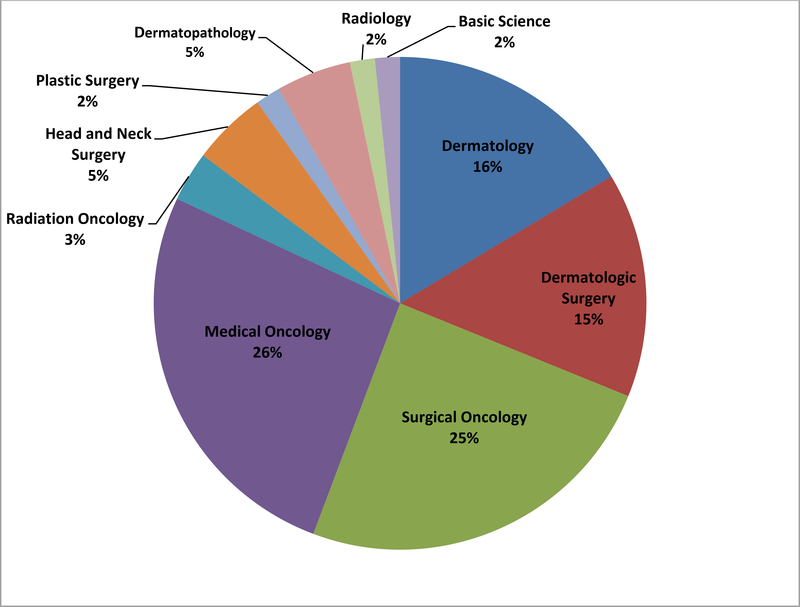

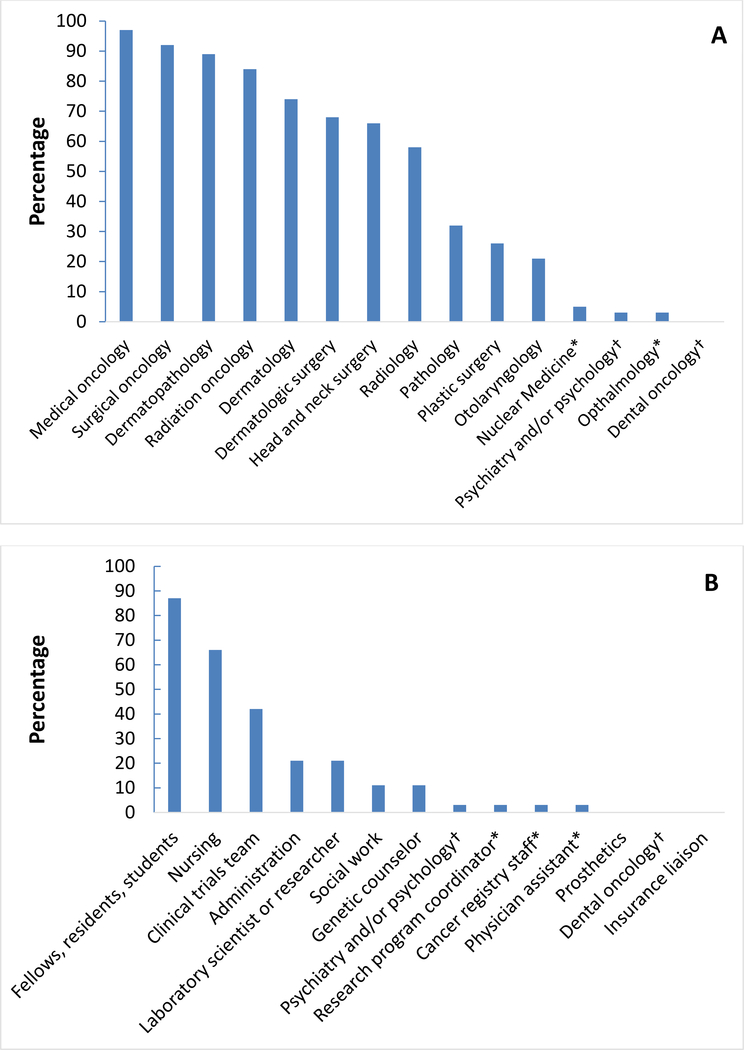

Table 1 summarizes survey responses regarding conference structure. The geographic distribution, according to the census regions identified by the US Census Bureau, was relatively equal among the survey respondents. The majority of respondents (87%) indicated that the meeting had a designated leader. Half of the respondents (52%) indicated that specialists from multiple clinical disciplines served as group co-leaders, while 48% indicated the leader(s) were from a single specialty. The distribution of the clinical specialties for group leaders is shown in Figure 1. Medical and surgical oncologists together comprised half of the meeting leaders. Dermatologists, including dermatologic surgeons and dermatopathologists, comprised roughly one-third of the leaders. The majority of respondents also indicated that a meeting secretary or coordinator was involved in the meeting (84%). The distribution of attendees (and clinical specialists) attending the meeting is shown in Figure 2. Over 90% of meetings were attended by medical and surgical oncologists. The meetings most often occurred weekly (45%) and lasted for one hour (74%). Fifty-eight percent of respondents used videoconferencing. The majority of meetings were financially supported by the institution or individual departments, and 24% indicated funding from a philanthropic source.

Table 1.

Skin cancer tumor board structure (N=38).

| Geographic location | |

| Northeast | 9/38 (24%) |

| South | 10/38 (26%) |

| Midwest | 8/38 (21%) |

| West | 11/38 (29%) |

| Designated meeting leader | |

| Yes | 33/38 (87%) |

| No | 5/38 (13%) |

| Designated meeting secretary or coordinator | |

| Yes | 32/38 (84%) |

| No | 6/38 (16%) |

| Number of attendees | |

| 1–5 | 7/38 (18%) |

| 6–10 | 18/38 (47%) |

| 11–15 | 13/38 (34%) |

| 16–20 | 0/38 (0%) |

| 21–30 | 0/38 (0%) |

| >30 | 0/38 (0%) |

| Duration of establishment | |

| <1 year | 0/38 (0%) |

| 1–3 years | 5/38 (13%) |

| 4–6 years | 7/38 (18%) |

| 7–10 years | 6/38 (16%) |

| 10–15 years | 7/38 (18%) |

| >15 years | 13/38 (34%) |

| Frequency of meeting | |

| Weekly | 17/38 (45%) |

| Twice per month | 14/38 (37%) |

| Monthly | 6/38 (16%) |

| As needed | 1/38 (3%) |

| Duration of meeting | |

| 30 minutes | 2/38 (5%) |

| 60 minutes | 28/38 (74%) |

| 90 minutes | 7/38 (18%) |

| 120 minutes | 1/38 (3%) |

| Number of cases discussed per meeting | |

| 1–5 | 13/38 (34%) |

| 6–10 | 11/38 (29%) |

| 11–15 | 10/38 (26%) |

| 16–20 | 1/38 (3%) |

| 20+ | 3/38 (8%) |

| Videoconferencing used | |

| Yes | 22/38 (58%) |

| No | 16/38 (42%) |

| Financial support of meeting | |

| Institution | 24/38 (63%) |

| Individual department(s) | 20/38 (53%) |

| Philanthropic source | 9/38 (24%) |

Figure 1.

Clinical specialties of skin cancer tumor board conference leaders. N= 61*.

*Of the 33/38 (87%) respondents that indicated a designated meeting leader, 16 respondents indicated a single specialty and 17 respondents indicated multiple specialties as leaders, resulting in 61 leaders among 10 specialties.

Figure 2.

Distribution of attendees of skin cancer tumor boards. Percentage on the vertical axis represents the percentage of survey respondents indicating the specified group as attending their meeting. (A) Physician attendees. (B) Non-physician attendees.

*Answer was written in by one or more respondents under the “other” option, and was not listed as one of the multiple choice options.

†Specialties that may include both physician and non-physician individuals.

Conference Function

A summary of the survey results regarding meeting function is shown in Table 2. Melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma were the skin cancers that most groups discussed, followed by cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. All meetings involved presentation of clinical history, and the majority also presented radiographic images (95%), histopathology images (92%), and clinical photos (87%). Molecular pathology and genetic test results were presented less frequently (74% and 61%, respectively). Half of the respondents indicated that radiographic images were reviewed by a radiologist. Research protocols were discussed in 61% of meetings, and research presentations or guest speakers were featured in 39% of meetings. Physicians followed up with patients after the meeting according to 76% of respondents. The conference led to further discussion among physicians according to 71% of respondents. Notes were recorded in the patient’s medical record by 58% of respondents, while 24% of meetings had minutes recorded. A database of skin cancer patients was maintained by 68% of the groups.

Table 2.

Skin cancer tumor board function (N=38).

| Diagnoses reviewed | |

| Melanoma | 35/38 (92%) |

| Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | 32/38 (84%) |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 31/38 (82%) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 35/38 (92%) |

| Cutaneous adnexal neoplasm | 31/38 (82%) |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | 27/38 (71%) |

| Cutaneous lymphoma | 8/38 (21%) |

| Type of cases | |

| Not yet diagnosed | 22/38 (58%) |

| Pre-surgical | 34/38 (89%) |

| Post-surgical | 37/38 (97%) |

| Challenging cases | 38/38 (100%) |

| Recurrent disease | 36/38 (95%) |

| Follow-up | 23/38 (61%) |

| Interest | 31/38 (82%) |

| Potential clinical trial enrollment* | 2/38 (5%) |

| Monitor response to treatment* | 1/38 (3%) |

| Type of information presented | |

| Clinical history | 38/38 (100%) |

| Clinical photos | 33/38 (87%) |

| Radiographic imaging | 36/38 (95%) |

| Histopathology slides | 35/38 (92%) |

| Molecular pathology | 28/38 (74%) |

| Genetic testing | 23/38 (61%) |

| Available clinical trials* | 1/38 (3%) |

| Confocal imaging* | 1/38 (3%) |

| Literature review* | 1/38 (3%) |

| Radiographic images reviewed by a radiologist | |

| Yes | 13/38 (34%) |

| No | 19/38 (50%) |

| Sometimes | 6/38 (16%) |

| Histopathology slides reviewed by a dermatopathologist | |

| Yes | 31/38 (82%) |

| No | 2/38 (5%) |

| Sometimes | 5/38 (13%) |

| Discussion of research protocols | |

| Yes | 23/38 (61%) |

| No | 15/38 (39%) |

| Research talks/Guest speakers | |

| Yes | 15/38 (39%) |

| No | 23/38 (61%) |

| Follow up action after meeting | |

| Minutes are recorded | 9/38 (24%) |

| Notes are recorded in patient’s chart | 22/38 (58%) |

| Physician contact with patient | 29/38 (76%) |

| Nursing/PA/ancillary staff contact with patient | 21/38 (55%) |

| Further discussion among physicians | 27/38 (71%) |

| Cases are entered in a database | 9/38 (24%) |

| No further contact | 5/38 (13%) |

| Does your program manage a skin cancer database? | |

| Yes | 26/38 (68%) |

| No | 12/38 (32%) |

Answer was written in by one or more respondents under the “other” option, and was not listed as one of the multiple choice options.

Conference Impact:

Results regarding the impact of tumor board are shown in Table 3. Ninety-seven percent of respondents indicated that their tumor board had a moderate to significant impact on patient care. All respondents indicated that the meeting enhanced communication among physicians, and was an opportunity for physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals to discuss cases together. Treatment options that were not previously considered were discussed in 92% of meetings, and 78% indicated that the meeting encouraged use of the most recent guidelines for management.

Table 3.

Skin cancer tumor board impact (N=37).

| Impact of meeting on patient care | |

| No impact | 0/37 (0%) |

| Minimal impact | 1/37 (3%) |

| Moderate impact | 12/37 (32%) |

| Significant impact | 24/37 (65%) |

| Value of meeting | |

| Enhanced communication among physicians | 37/37 (100%) |

| Continuing medication education for physicians | 27/37 (73%) |

| Encouraged use of most recent guidelines for management | 29/37 (78%) |

| More treatment options for patients | 34/37 (92%) |

| Reduced number of visits for patients | 15/37 (41%) |

| Opportunity for physicians, nurses, allied health professionals to discuss cases together | 37/37 (100%) |

| Drives development of new research protocols | 24/37 (65%) |

| Increased enrollment of patients in clinical trials | 25/37 (68%) |

| Improved standardization of care* | 2/37 (5%) |

| Barriers to setting up meeting | |

| Finding a common date and time | 23/37 (62%) |

| Lack of administrative support | 7/37 (19%) |

| Lack of specialties | 9/37 (24%) |

| Finding a physician to take on leadership role | 3/37 (8%) |

| Lack of time to prepare for meeting | 9/37 (24%) |

| High caseload | 8/37 (22%) |

| Lack of financial support | 13/37 (35%) |

| None of the above | 6/37 (16%) |

| Lack of technological support* | 1/37 (3%) |

| Time constraints of meeting* | 1/37 (3%) |

| Competing tumor boards* | 1/37 (3%) |

Answer was written in by one or more respondents under the “other” option, and was not listed as one of the multiple choice options.

The most frequently cited barriers to organizing tumor board conference was finding a common available date and time for attendees (62%) and lack of financial support (35%). The most common suggestion for improvement was an increase in attendance, specialties, and/or motivation to attend. One respondent specifically indicated that they would like community providers to attend the meeting as well. Five respondents suggested the implementation of a skin cancer database. Other suggestions were the inclusion of radiographic images or attendance by a radiologist, increased financial support, the provision of food at the meeting, and increased administrative support. Improved documentation of the meeting was also indicated by three respondents.

Discussion

In the US, NCCN guidelines recommend multidisciplinary tumor board consultation for complicated and high-risk skin cancer cases.15–17 However, it is not specifically stated what kind of format this tumor board should take. Furthermore, there is a paucity of information regarding skin cancer tumor board conferences, both within the medical literature and the websites of individual cancer centers. The current survey findings provide relevant information regarding the structure, function and impact of existing skin cancer tumor board conferences at cancer centers across the US. Among existing conferences, there was relative consistency in the meeting structure. There was heterogeneity in conference function, which may be explained by available resources of the institution and its investment in the tumor board conference or skin cancer program. Remarkably, we observed that nearly a quarter of NCI-designated Comprehensive and Clinical Cancer Centers did not have a tumor board conference in which skin cancer cases were discussed, either as a primary focus, or included among discussions of other cancers. This finding highlights the importance of defining the purpose and structure of skin cancer tumor board conferences for institutions who hope to start their own conference, as well as for patients who would benefit from multidisciplinary discussion and the providers who may refer them.

A model for standardization can be seen in the UK, where there is a greater availability of published information regarding multidisciplinary skin cancer management. The United Kingdom Multidisciplinary Guidelines for the management of NMSC recommend high-risk patients to be treated by a skin cancer multidisciplinary team.18 More specifically, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), which publishes national health guidance for England, recommends two levels of multidisciplinary teams for the management of skin cancer patients: one for local hospitals, and one for specialized cancer centers. These guidelines, which are based on best available evidence and consensus positions, describe the specialties that should be represented, the types of cases to be presented, the frequency of meetings, and the activities that should take place, including the recommended auditing of skin cancer cases on a regular basis.19 Adherence to these guidelines, as well as costs associated with their implementation, will require further investigation. However, this model may serve as a starting point for tumor board standardization.

The principal metric of the impact of tumor board conferences is the probability of change in individual patient management after formal multidisciplinary discussion. The majority of survey respondents (97%) indicated that their conference had a moderate to significant impact on patient care. As reported in the literature, patients discussed at multidisciplinary tumor board conferences may receive a change in diagnosis (18.4–29%) or treatment plan (20–52%).8–10,20 Tumor board conferences can improve coordination of patient care, clinical decision making, and increase adherence to nationally accepted guidelines.11,21 The multidisciplinary setting of these meetings facilitates the exchange of perspectives from different specialties and can lead to a more comprehensive discussion of each patient’s treatment options. The current survey findings are consistent with these previously described benefits of tumor board conferences. Documentation of tumor board discussion and follow-up of patients showed variability among survey respondents. These are essential areas in which standardization would be particularly beneficial in assessing meeting impact.

Costs were not directly assessed in the current survey; however, 41% of the respondents indicated that tumor board discussion led to reduced clinic visits for patients. A cost-analysis study of a multidisciplinary melanoma clinic found that patients treated in the multidisciplinary clinic saved a third party payer roughly $1,600 per patient when compared to those treated in the community.22 The lower costs were attributed to fewer office visits, blood tests, radiographic imaging, and procedures. It is also important to note the institutional costs required to maintain multidisciplinary meetings. An analysis of multidisciplinary team meetings in the UK found that the median cost per month of these meetings, based on attendees’ salaries and basic overhead costs, was £5,136, which is roughly $7,277 in US dollars.23 Beyond consideration of salary support, the majority of respondents indicated that tumor board conferences were funded by the institution and/or individual departments. Research funds or grants were not included as answer options; however, this could be a potential source of funding as well for tumor board conferences that utilize the meeting for research purposes.

These results suggest that institutions should do more to support a skin cancer tumor board conference. Studies have demonstrated that physicians affiliated with accredited cancer centers are more likely to participate in tumor boards.24 However, participation in tumor boards can be time-consuming, and therefore viewed as unfavorable by prospective attendees. Nearly a quarter of this study’s survey respondents indicated lack of time to prepare for the meeting as a barrier. Other common barriers included finding a common date and time for the meeting (62%) and lack of financial support (35%). A systematic review of multidisciplinary cancer teams found that insufficient time for preparation, excessive caseload, low attendance, lack of nursing input, and paucity of leadership affect management decisions.25 A study from the UK reported that the most frequently cited organizational improvement to multidisciplinary team working was to have more time dedicated to the meeting.26 In a follow-up analysis of these same survey results, the authors found that good relationships between team members, adequate skills in communication and leadership, and organizational support were key factors for effective teamworking.27 Further research into the appropriate amount and type of institutional support for the maintenance of an effective multidisciplinary skin cancer program is clearly needed.

There are several limitations to this study. One is that we may not have captured all tumor board conferences in which skin cancers are discussed, resulting in an underestimation of the true number of existing conferences. Another limitation is the inherent bias in those who responded to the survey. It is possible that those who did not respond to the survey were less satisfied with the structure or function of their tumor board conference. In addition, the survey population consists of a select group of physicians who are part of nationally-recognized cancer centers. The findings of this study may not be generalizable to all centers that treat skin cancer patients. In fact, further investigations into barriers to multidisciplinary care as well as the role of community hospitals and their inclusion in tumor board discussions are critical in developing a greater understanding of this form of care. The survey questions also focused on the clinical aspect of tumor board conferences. Although the vast majority of respondents indicated that these tumor boards resulted in changes in patient management, the magnitude of change, and the percentage of patients with change were not captured. Many tumor board conferences function as both a conduit for clinical care in a multidisciplinary setting, as well as an arena to facilitate research. The survey did not comprehensively assess the research component of tumor board conferences. Lastly, some of the survey questions included an “other” option where respondents wrote in an answer. If those answers were included in the multiple choice options, there may have been a greater number of respondents also choosing these answers.

Future directions for research include defining metrics for skin cancer tumor board conferences. These metrics may include reasons for presentation, changes in diagnosis or management plan following tumor board discussion, attendance, enrollment in clinical trials, and cost analysis. In addition, the optimal method in which to record the proceedings of the meeting, such as formal minutes, documentation in the patient’s medical record, or a tumor board database, remains to be determined. While assessing the value of tumor board conferences is difficult, standardizing the structure and recording these key metrics may be a step towards further understanding the potential impact of these multidisciplinary meetings.

Conclusions

Nearly one quarter of NCI-designated Comprehensive and Clinical Cancer Centers did not report having a tumor board conference where skin cancer cases were discussed. Existing skin cancer tumor board conferences show relative homogeneity in structure, but variability in function. The majority of respondents indicated moderate to significant impact on patient care, but further research into the objective value of skin cancer multidisciplinary meetings is needed. Existing conferences enhance communication among physicians and provide a valuable opportunity for involved specialties and professions to discuss cases. The results of this survey may aid other institutions striving to develop and refine skin cancer tumor board conferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This research is funded in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute / National Institutes of Health (P30-CA008748) made to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Michael A. Postow: scientific advisory board participation for NewLink Genetics, BMS, Novartis, Merck, Array Biopharma, and Incyte, and honoraria from BMS and Merck. Vivian T. Yin: consultant for Merz Pharmaceuticals and Genentech. Christopher A. Barker: scientific advisory board participation for Pfizer; research funding paid to institution by Merck, BMS, Elekta and Amgen.

Consent for publication: The authors consent to the publication of this submission.

IRB status: Approved for exemption.

References

- 1.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the united states, 2006. Archives of Dermatology. 2010;146(3):283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151(10):1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald TL, Dennis S, Kachare SD, Vohra NA, Wong JH, Zervos EE. Dramatic increase in the incidence and mortality from merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. The American Surgeon. 2015;81(8):802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Melanoma Skin Cancer. 2017; https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed December 28, 2017.

- 5.Definition of Tumor Board Review. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?cdrid=322893. Accessed August 30, 2017.

- 6.American College of Surgeons / Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care Chicago: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Manual for cancer services. London: Department of Health;2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman EA, Guest AB, Helvie MA, et al. Changes in surgical management resulting from case review at a breast cancer multidisciplinary tumor board. Cancer. 2006;107(10):2346–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greer HO, Frederick PJ, Falls NM, et al. Impact of a weekly multidisciplinary tumor board conference on the management of women with gynecologic malignancies. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2010;20(8):1321–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.vanHagen P, Spaander MCW, Gaast Avd, et al. Impact of a multidisciplinary tumour board meeting for upper-GI malignancies on clinical decision making: a prospective cohort study. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;18:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman RK, VanWoerkom JM, Vyverberg A, Ascioti AJ. The effect of a multidisciplinary thoracic malignancy conference on the treatment of patients with lung cancer. European Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2010;38:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Saghir NS, Chahara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. Journal of Global Oncology. 2015;1(2):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCI-Designated Cancer Centers. https://www.cancer.gov/research/nci-role/cancer-centers. Accessed December 8, 2017.

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. About NCCN. 2017; https://www.nccn.org/about/. Accessed December 29, 2017.

- 15.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Basal Cell Skin Cancer, Version 1.2018 2018.

- 16.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Squamous Cell Skin Cancer, Version 2.2018 2018.

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Melanoma, Version 2.2018 2018.

- 18.Newlands C, Currie R, Memon A, Whitaker S, Woolford T. Non-melanoma skin cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 2016;130(S2):S125–S132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Improving outcomes for people with skin tumours including melanoma. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence;2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basta YL, Bolle S, Fockens P, Tytgat KMAJ. The value of multidisciplinary team meetings for patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: A systematic review. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2017;24:2669–2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS National Cancer Action Team. Multidisciplinary care team members views about MDT working: Results from a survey commissioned by the National Cancer Action Team. London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fader DJ, Wise CG, Normolle DP, Johnson TM. The multidisciplinary melanoma clinic: A cost outcomes analysis of specialty care. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1998;38(5):742–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeIeso PB, Coward JI, Letsa I, et al. A study of the decision outcomes and financial costs of multidisciplinary team meetings (MDMs) in oncology. British Journal of Cancer. 2013;109:2295–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scher KS, Tisnado DM, Rose DE, et al. Physician and practice characteristics influencing tumor board attendance: results from the provider survey of the Los Angeles women’s health study. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2011;7(2):103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb BW, Brown KF, Nagpal K, Vincent C, Green JSA, Sevdalis N. Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2011;18:2116–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Arora S, Pinto A, Vincent C, Green JSA. Teamwork and team decision-making in multidisciplinary cancer conferences: barriers, facilitators, and opportunities for improvement. World Journal of Surgery. 2011;35:1970–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamb BW, Taylor C, Lamb JN, et al. Facilitators and barriers to teamworking and patient centeredness in multidisciplinary cancer teams: findings of a national study. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2013;20(5):1408–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.