Abstract

Background

The majority of children receiving care in the emergency department (ED) are discharged home, making discharge communication a key component of quality emergency care. Parents must have the knowledge and skills to effectively manage their child’s ongoing care at home. Parental fatigue and stress, health literacy, and the fragmented nature of communication in the ED setting may contribute to suboptimal parent comprehension of discharge instructions and inappropriate ED return visits. The aim of this study was to examine how and why discharge communication works in a pediatric ED context and develop recommendations for practice, policy, and research.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the published and gray literature. We searched electronic databases CINAHL, Medline, and Embase up to July 2017. Policies guiding discharge communication were also sought from pediatric emergency networks in Canada, USA, Australia, and the UK. Eligible studies included children less than 19 years of age with a focus on discharge communication in the ED as the primary objective. Included studies were appraised using relevant Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklists. Textual summaries, content analysis, and conceptual mapping assisted with exploring relationships within and between data. We implemented an integrated knowledge translation approach to strengthen the relevancy of our research questions and assist with summarizing our findings.

Results

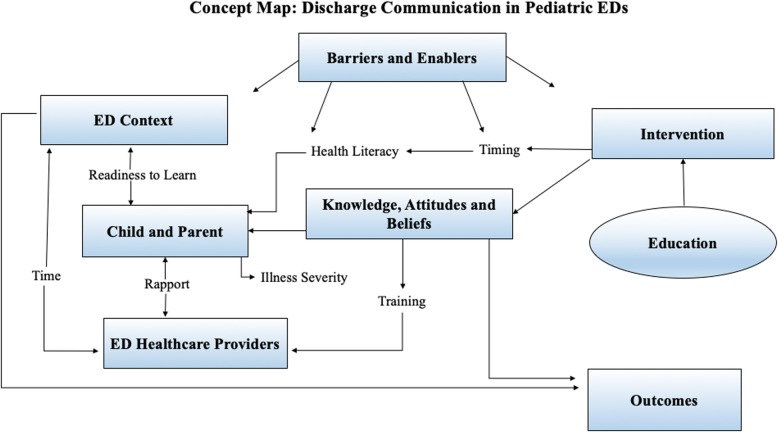

A total of 5095 studies were identified in the initial search, with 75 articles included in the final review. Included studies focused on a range of illness presentations and employed a variety of strategies to deliver discharge instructions. Education was the most common intervention and the majority of studies targeted parent knowledge or behavior. Few interventions attempted to change healthcare provider knowledge or behavior. Assessing barriers to implementation, identifying relevant ED contextual factors, and understanding provider and patient attitudes and beliefs about discharge communication were identified as important factors for improving discharge communication practice.

Conclusion

Existing literature examining discharge communication in pediatric emergency care varies widely. A theory-based approach to intervention design is needed to improve our understanding regarding discharge communication practice. Strengthening discharge communication in a pediatric emergency context presents a significant opportunity for improving parent comprehension and health outcomes for children.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42014007106.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13643-019-0995-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Discharge communication, Pediatric emergency care, Caregivers, Systematic review, Narrative synthesis, Integrated knowledge translation

Background

The discharge process in a pediatric emergency department (ED) can introduce vulnerability for parents and caregivers. Attention to this phenomenon is critical given that following a visit to the ED the majority of children are discharged home under the care of their parents [1, 2]. Ideally, parents should depart the ED with the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively manage their children’s care at home. However, following ED discharge, many caregivers and patients are unable to specify their diagnosis, list medications they received, outline post-ED care, or identify when to seek further medical attention [3–5]. The discharge process should include communication of important information about the child’s illness, verification of comprehension, and tailoring of the discharge instructions to address areas of misunderstanding [6]. Yet, this is not always the parents’ experience, and evidence supports that poor quality ED discharge communication can impact subsequent health care utilization, including unscheduled return visits to the ED [7, 8]. Comprehension of discharge communication has been shown to be an important factor in promoting adherence to discharge instructions and preventing unnecessary return visits; however, comprehension is rarely assessed in practice [9]. A number of factors are known to impact comprehension including quality of the communication provided [10], health literacy, numeracy, and reading ability [11–13].

A number of recent reviews have explored discharge communication, including a recent systematic review to establish the cost-effectiveness of implementing electronic discharge communication to support the transition between acute and community care [14]. Another review focused on the parent management of inpatient and ED discharge instructions [15]. We conducted a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the discharge communication literature to gain a better understanding of how and why discharge communication functions in a pediatric ED context and to inform the development of recommendations for future research, policy, and practice change. Our review addressed the following questions: (1) What types of interventions, processes, and policies have been examined regarding discharge communication in a pediatric ED context and (2) How does the discharge process impact parent, patient, and provider outcomes?

Methods

Study design

We conducted a systematic review with narrative synthesis following methods outlined by Popay et al. [16]. This type of review explores relationships within and between studies [17]. Techniques are employed to expose the context and characteristics of the included studies to facilitate comparison of similarities and differences across studies [18]. Further details of the review protocol have been published elsewhere [19]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42014007106).

We embedded an integrated knowledge translation (iKT) approach in our review, whereby we met with key knowledge users (e.g., ED clinicians, administrators, parents, and researchers) during each stage of the review to strengthen the relevancy of our research questions and tailor our recommendations. We employed a number of communication strategies to maximize engagement including email and face-to-face and teleconference meetings. Critical reflection of engagement was conducted through detailed documentation of team discussions at all meetings, outlining input from the different stakeholder groups, and underlying rationale for decisions made at each stage of the synthesis process. We also integrated a knowledge user check-in strategy, where at regular intervals during each meeting, we paused to summarize the discussion and solicit questions. Three key meetings included (1) a teleconference to refine the research question, (2) a face-to-face meeting to discuss the results of the preliminary analysis, and (3) a teleconference meeting to discuss findings and draft recommendations. Finally, authors from three of the included studies (all ED physicians from academic teaching hospitals) were contacted by email and invited to provide feedback on the preliminary findings. Expert feedback was provided through a brief telephone interview lasting 15–30 min.

We used the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) [20], a theory-based method for characterizing and designing behavior change interventions, as a guiding framework to examine the discharge communication interventions in the included studies. Pairs of two reviewers (KM, MB, AG, or JAC) independently coded the narrative descriptions of all interventions. A directed content analysis approach was used to classify intervention description according to the nine intervention function types (i.e., the mechanism by which the intervention is proposed to function) of the BCW [20]. Reviewers met to compare consistency after coding the first and third study and then after every five studies. Differences in coding were discussed to achieve consensus.

We also coded the 75 included studies to identify barriers and enablers to intervention implementation and effectiveness as reported by the study author. Full text articles were loaded into NVivo (QSR International) and were coded by two reviewers (JAC and AG) [21]. Reviewers met throughout the process to ensure consistent coding of barriers and enablers and to discuss sections that were challenging to code.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in consultation with a library scientist and peer reviewed by a second library scientist from the Alberta Research Centre for Child Health Evidence (ARCHE; University of Alberta) prior to being implemented in three databases from their date of inception to July 7th, 2017: CINAHL, Medline, and Embase. Please see Additional file 1 for the list of all search strategy terms. We also hand-searched relevant emergency pediatric journals for articles published between January 1st, 2009 and October 31st, 2018: Annals of Emergency Medicine, Academic Emergency Medicine, Pediatric Emergency Care, Journal of Emergency Medicine, and Journal of Emergency Nursing. Additionally, a further search was conducted by emailing the ED administrators of the 15 Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) sites and the Chairs of the Pediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative (PREDICT), Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee (PEM-CRC), Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN), and the Paediatric Emergency Research in the United Kingdom & Ireland (PERUKI) and reviewing relevant national and international websites to identify existing discharge communication policies and procedures that might be relevant in a pediatric ED context.

Study selection

Studies were included if they described or evaluated changes in the structure or process of care in the ED to enhance discharge communication as their primary objective. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods study designs were eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if interventions took place outside of the ED or primary outcomes were not relevant to discharge communication. The published protocol paper for this review provides further details on the process of selecting studies [19]. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies and abstracts can be found in Additional file 2.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by teams of two independent reviewers using a customized data abstraction form and discrepancies were assessed by JAC. Full data extraction included study design details (i.e., year of publication, country, type of ED), detailed description of the intervention (i.e., description of individual components, reported use of theory or assumptions about causal mechanisms supporting the different components, duration, and timing of the intervention), implementation strategies (i.e., training or instructions provided to participants, timing), participant details (i.e., age of the child, illness presentation, parent characteristics, health care provider characteristics), and author reported factors and/or processes identified as impacting implementation. Our primary outcome of interest was any change in process, parent, healthcare provider, or patient outcome related to the discharge communication intervention. We extracted details about authored reported primary outcomes (i.e., timing, measures, target of the intervention). Data was managed using excel and intervention descriptions were exported to NVivo 10 (QSR International) for analysis [19].

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed at the study level by two independent reviewers using critical appraisal checklists from Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [22]. Each study was appraised using the appropriate checklist for the study design. JBI checklists are designed to assess the quality of a study’s methodologies and outcomes, and to identify potential sources of bias or confounding variables within the study [22]. Options for checklist responses included “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” or “not applicable.” Each reviewer used the JBI definitions and checklists and provided evidence from the article to support the reasoning for their scoring. At two points in the appraisal process, the reviewers met to meet consensus and resolve discrepancies. A third reviewer was consulted when discrepancies could not be resolved.

Data synthesis

The primary aim of this review was to understand how and why discharge communication interventions and processes work in a pediatric ED context. To address this aim, we employed a number of data synthesis strategies proposed by Popay et al. [16] to examine the individual study findings. We developed summary tables, which outlined study design, clinical context, intervention components, intervention target, quality appraisal, outcome measures, and direction of effect. Findings of included studies did not lend themselves to quantitative analysis due to the wide range of intervention descriptions and outcome measures. We also developed structured textual summaries of all included studies that outlined primary objectives, details regarding context and setting, descriptions of any interventions and implementation strategies, relevant outcomes, and barriers reported by study authors. Content analysis was carried out on all extracted data to assist with identifying importing themes and gaps in the existing evidence.

Results

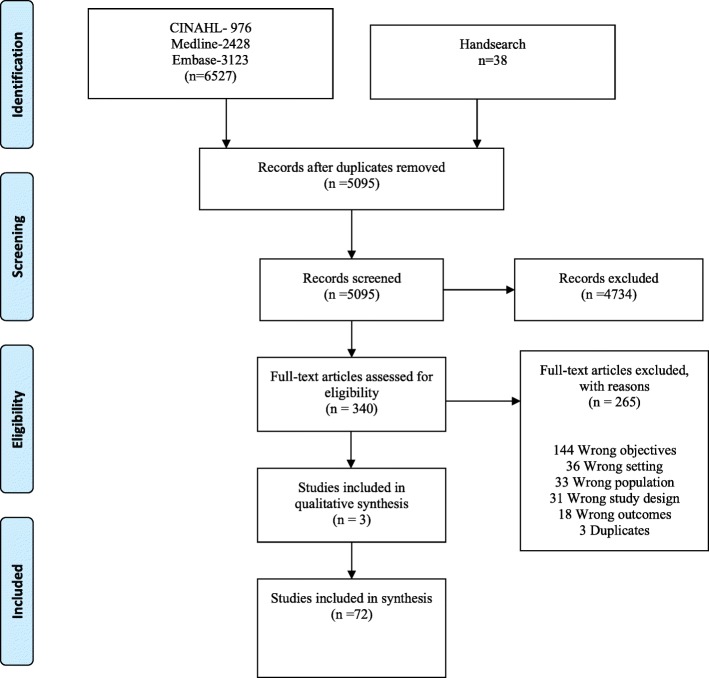

A total of 5095 studies were identified by the search. Of these studies, 4734 studies were excluded at the title and abstract phase and 342 were eligible for full text screening. A total of 265 articles were excluded at the full text screening stage (see Additional File 3), resulting in 75 articles included in the review (Fig. 1). Half of the included papers were observational studies (n = 37) [23–59] and 47% (n = 35) were either randomized controlled trials (RCT) or quasi-experimental studies [60–94]. Three qualitative studies were also included [95–97]. Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Detailed about excluded studies can be found in additional Table 2. Included studies covered a range of settings: pediatric ED, mixed ED (adult and pediatric), urban, rural, and academic teaching facilities. Although included studies focused on a variety of illness presentations, asthma (n = 20) was the most common [27, 29, 39, 42, 46, 61, 62, 65, 67, 70, 75, 77, 79–83, 85, 89, 90]. Other common illnesses were minor head injury (n = 12) [30, 34, 36, 44, 48, 50, 51, 56, 58, 68, 86, 94] and fever (n = 9) [35, 46, 64, 67, 68, 71, 72, 78, 88]. Outcomes varied across included studies but primarily involved improving parent adherence with discharge instructions or follow-up appointments (n = 12) [60, 61, 66, 75, 77, 81–85, 90, 93], improving parent knowledge of illness treatment (n = 7) [63, 65, 67, 68, 70–72], and reducing unnecessary return ED visits (n = 5) [62, 64, 69, 88, 89]. All studies were published from 1979 to 2018, with just over half (n = 41) of the studies published since 2009 [23–25, 30, 32–34, 37, 40, 42, 44–52, 55, 56, 59, 61, 64–68, 71–73, 75, 76, 79, 81, 83, 85, 92, 94, 96, 97].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram

Table 1.

Description of included studies (n = 75)

| Author, publication year | Study objective related to discharge communication | Study design | Appraisal checklist used | Country | Sample characteristics | Key findings as related to study objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Harthy et al. 2016 [24] | To determine the delivery and usefulness of discharge instructions received in the pediatric ED. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | Saudi Arabia | 173 parents who had a child discharged from a pediatric ED and attended a follow-up appointment. | 55% of parents received verbal discharge communication and 35% did not receive any form of instruction. The 6% of parents who received both verbal and written instructions were more knowledgeable about medication details compared the other groups. |

| Ali et al. 2012 [25] | To determine if discharge communication or poor provider-patient relationship were reasons for return visits to the ED within 72 h of initial visit. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 246 parents who returned to the ED within 72 h of the initial visit with their child (surveyed: n = 124, not surveyed: n = 122). | 75% of parents returned because their child’s symptoms had not improved. Almost all parents (94%) thought their discharge communication were informative and were satisfied with their care on the initial visit. |

| Chacon et al. 1994 [26] | To assess parents’ reading level, assess written information resources provided in pediatric ED to ensure information was an appropriate reading level, and update resources based on the findings. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | Canada | 1022 parents who attended a pediatric ED with their child. | Half of the written discharge communications provided in the ED were written at a university level, much higher than the recommended grade 6–7 reading level. Parents found the updated written instructions provided useful information and were easy to read and understand. |

| Demorest et al. 2004 [31] | To assess parents’ memory of receiving poison prevention information during the ED visit. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 75 parents of children (< 6 years) who were brought to ED for acute accidental poisoning. | 73% of parents did not recall receiving any information on poison prevention during their ED visit. |

| Grover et al. 1994 [57] | To examine parent recall of information and instruction provided during an ED visit. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 152 parents with children who presented to the ED with non-traumatic conditions. | 25% of parents could not properly recall their child’s diagnosis. When one medication was prescribed, only 30% of parents could recall the name of the medication, and only 13% could properly name all medications when multiple were prescribed. |

| Hanson et al. 2017 [33] | To determine if an illustrated education sheet was a feasible method to convey information to parents and children in the ED. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 50 parents and their child (4–18 years) who presented to the pediatric ED. | Comic module was feasible to use in the ED and could be independently read in less than 11 min. Children < 12 years needed help. At 3-day follow-up, 86% of parents remembered all components taught in the comic educational module. |

| Johnson 1999 [36] | To determine if parents valued and utilized written health information provided during an ED visit. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | Australia | 200 parents of children who received pamphlets when their child presented at the ED for gastroenteritis, croup, application of bandage, or head injury. | 95% of parents found the written information useful and 71% kept it for reference. Only half of parents indicated that a clinician reviewed the pamphlet with them during the ED visit. |

| Kaestli et al. 2015 [59] | To determine if the provision of customized drug information leaflets would improve parent knowledge. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | France | 125 French-speaking parents of children (0–16 years) who were discharged from ED (control: n = 56, intervention: n = 69). | Parents who received the drug information leaflets had significantly improved knowledge scores than controls about drug dosing (89.1% vs. 62.3%), frequency (85.5% vs. 57.9%), duration (66.7% vs. 34.2%), and indication (94.9% vs. 70.2%) (p ≤ 0.0001). |

| Lawson et al. 2011 [38] | To determine parents’ knowledge about child car seats and how many parents received car seat-specific discharge instructions in the ED. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 92 parents who attended the ED with their child following a car accident. | Most parents reported regular use of car seats for their child and knew of the requirements for car seats for children < 8 years. Only 18% of parents received information regarding child car seat safety during their ED visit. |

| Macy et al. 2013 [40] | To examine physicians’ awareness of and referrals to child passenger safety resources. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 638 ED physicians. | Physicians working in pediatric ED were significantly more likely to know about hospital resources to assist with child safety compared to physicians in non-pediatric centres (p < 0.001). More than half of physicians identified that they likely would not provide written discharge communication about car seats following a motor vehicle collision. |

| Melzer-Lange et al. 1998 [41] | To compare rates of follow-up care between ED violence related injuries and other presentations. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 426 medical records of adolescent patients (13–18 years) who presented to the pediatric ED. | Adolescents who presented with violence related injuries were less likely to receive discharge information about follow-up care compared to other ED presentations. |

| Philips 2009 [42] | To evaluate the implementation of a best practice-based asthma management policy. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | Australia | 100 parents who presented to the ED with a child (< 17 years) with asthma. | Parents’ asthma management greatly improved following the intervention. Responses to the follow-up survey improved after the intervention implementation. |

| Ray et al. 2016 [45] | To determine how adolescents who attend the ED prefer to receive discharge and follow-up communication. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 439 adolescents (14–19 years) who attended the pediatric ED. | 78% of adolescents preferred receiving ED discharge communication and follow-up appointment information via electronic means, with 57% of these participants preferring to receive this information in both printed and electronic formats. |

| Sargant and Milsom 2012 [47] | To develop a cellphone “app” to provide additional written and oral education for common ED presentations. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | UK | 520 parents who waited for care for at least 30 min in the ambulatory zone between 10 am and 10 pm. | 97% of survey respondents thought phone apps would be useful in providing additional information following an ED visit. |

| Stevens et al. 2010 [50] | To identify if parents were able to recognize post-concussive symptoms following ED discharge. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 105 parents of children (5–17 years) who were treated at pediatric ED for concussion. | Almost 70% of parents were not able to identify post-concussive symptoms in their child and 46.6% did not attribute their child’s symptom(s) to their concussion. |

| Wahl et al. 2011 [52] | To identify parents’ thoughts on the current methods of ED discharge communication and examine families’ needs for health information. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | UK | 1046 parents of children presenting to the pediatric ED. | 80.5% of parents enjoyed the current written discharge communication, but 47.9% noted a video format would be useful. Over half of parents also used friends and family (59.5%) and the internet (57.5%) for additional information following ED discharge. |

| Waisman et al. 2003 [53] | To examine parents’ level of understanding of discharge communication and factors that influence their understanding. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | Israel | 287 parents of children discharged home from the ED. | 75% of parents understood their child’s diagnosis and 84.5% understood the treatment plan. The use of medical terms and jargon was the primary reason for not fully understanding the information. |

| Waisman et al. 2005 [54] | To examine the impact of diagnosis-specific discharge communication sheets on parents’ understanding of ED discharge communication. | Cross-sectional | Analytical cross-sectional study | Israel | 95 parents of children discharged home from the ED. | Parents were significantly more likely to fully understand treatment instructions (p = 0.025) with the use of the information sheets, but it did not significantly improve understanding of their child’s diagnosis (p = 0.54). |

| Zonfrillo et al. 2011 [55] | To examine ED physicians’ knowledge of child passenger safety recommendations and their provision of this information. | Cross-sectional survey and retrospective chart review | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 317 physicians who reported routinely treating children involved in motor vehicle collisions. | 85% of physicians thought it was important to include discharge communication about child passenger safety recommendations, although a review of medical charts showed only 8.6% of visits contained child passenger information. |

| Fung et al. 2009 [58] | To review the content of written discharge information provided to mild traumatic brain injury patients and their caregivers, compared to six key evidence-based recommendations. | Cross-sectional study | Analytical cross-sectional study | Canada and USA | 10 ED in New York and five ED in Ontario | All of the written forms included in the study varied widely in the content and delivery of discharge information. Only one form included all six recommendations. The average reading level of the resources was 8.2, compared to the ideal level of 5–6. |

| Hawley et al. 2012 [34] | To evaluate printed resources provided to parents of children with head injuries. | Cross-sectional study | Analytical cross-sectional study | UK | 211 hospitals provided copies of their printed head injury resources for the study. | The quality of information provided in the printed resources varied. Thirty-three resources received a perfect score and an additional 33 resources were considered to include questionable information. |

| Qureshi et al. 2013 [44] | To evaluate written discharge information provided to parents of children with head injuries with the recommendations from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN). | Cross-sectional study | Analytical cross-sectional study | Scotland | 36 hospitals provided copies of the written head injury information. | The quality of written information for head injuries varied widely, with anywhere from 4 to 20 of the 20 SIGN urgent symptoms to monitor being listed (median score of 10/20 guidelines identified). Two leaflets contained the majority of head injury guidelines and four pamphlets provided erroneous or unclear details. |

| Thomas et al. 2017 [51] | To determine the effect of reinforcing written discharge communication with verbal instruction on parents’ recall of discharge communication. | Nested observational study | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 93 parents of pediatric patients presenting to the ED with mild traumatic brain injury. | Receiving verbal instructions in addition to written handouts on post-concussion care was associated with improved recall of instructions (67% vs 44%; p < 0.05). |

| Cheng et al. 2002 [27] | To assess factors associated with metered-dose inhaler spacers (MDIS) use at home in children with asthma who received asthma education during their ED visit. | Prospective observational | Analytical cross-sectional study | Australia | 73 parents of children (12 months–16 years) who attended a pediatric ED with asthma. | Compliance with MDIS use at home was significantly higher when MDIS was used during the ED visit (p = 0.05), the parents received written instructions on how to use MDIS at home (p = 0.003), and receiving a smaller sized spacer (p ≤ 0.001). Parent preferences and size of the spacers were factors in non-compliance at home. |

| Crain et al. 1999 [29] | To assess the development and use of a tool to code history taking and discharge planning during asthma related ED visits. | Prospective observational | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 154 parents of children (4–9 years) who presented to an ED with asthma. | Half of the items (7/13) on the ED asthma care checklist were endorsed by over 90% of physicians and allergists. Very few elements from the checklist were identified during ED visits. |

| Hemphill et al. 1998 [35] | To identify factors associated with compliance with recommended follow-up after ED visits. | Prospective observational | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 330 parents of children (3 months–10 years) who presented to the ED with fever. | Parents who received an appointment time were 2.5 times as likely to comply with follow-up than parents who had to make an appointment with a pediatrician. |

| Pizarro et al. 1979 [43] | To reduce hospitalizations by evaluating the effectiveness of training mothers in the ED to provide oral rehydration at home for their ill infants. | Prospective observational | Analytical cross-sectional study | Costa Rica | 100 infants (18 days–20 months) who presented to the ED with diarrhea. | Providing oral rehydration solutions and including parents in the rehydration care at the ED was beneficial in 92% of cases, and helped reduce length of hospital stay. |

| Samuels-Kalow et al. 2013 [46] | To examine how language impacted discharge communication and parents’ understanding of the information. | Prospective observational | Analytical cross-sectional study | USA | 210 parents of children (2 months–2 years) presenting at a pediatric ED with fever and/or respiratory illness. | 32% of parents demonstrated dosing errors during discharge, despite receiving written instructions for dosing. Spanish- vs English-speaking parents were significantly more likely to make a dosing error (54% vs. 25%). |

| Sauer et al. 2012 [49] | To determine if providing detailed information and a telephone hotline to help schedule follow-up appointments could reduce return ED visits. | Cohort study | Cohort | USA | 2120 patients attending a pediatric ED. | Patients who received the intervention were less likely to return to the ED following discharge. Only 10% of patients used the telephone hotline to schedule follow-up appointments. |

| Akinsola et al. 2017 [23] | To determine if a quality improvement project improved written discharge communication. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | USA | 1763 charts of children who presented to the ED with an emergency index score of 2 or 3. | The intervention significantly improved each of the eight individual (91–99% improvement) written discharge communication elements. There was a significant improvement in providing all eight elements of discharge communication to patients (p < 0.001). |

| Chorley 2005 [28] | To determine the ED discharge information provided for ankle sprains, follow-up appointments, and differences between instructions provided to adults and pediatric patients. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | USA | 374 patient charts. | None of the patients received all of the discharge communication components for ankle sprains. Younger patients were more likely than adult patients to receive the information to rest, ice, compress, elevate, and use analgesia medications. |

| De Maio et al. 2014 [30] | To assess the discharge information provided to pediatric patients following an ED visit for concussion. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | USA | 218 patients (6–18 years) who had presented to a pediatric ED with a possible concussion. | Most patients were not told to restrict activities following their concussion, although activity restriction was more likely to be discussed with patients with sports-based injuries. |

| Gaucher et al. 2011 [32] | To examine the effect of nurse counseling on common childhood illnesses on the return rates of patients who leave the ED without being seen by a physician. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | Canada | 10,323 children (< 19 years) who were triaged by a nurse but left the ED before being seen by a physician. | Nurse counseling for patients leaving the ED prior to seeing a physician significantly reduced likelihood of return to the ED within 48 h than those who were not counseled by a nurse (8.1% vs. 6.1%; OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.65–0.94). |

| Lawrence et al. 2009 [37] | To determine if standardized typed diagnosis-specific instructions decreased return visits to the pediatric ED. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | USA | 979 children who presented to the ED. | Diagnosis-specific typed discharge communication did not reduce inappropriate return (3% vs. 2.3%) or medically unnecessary (15% vs. 13%) visits to the ED compared to handwritten instructions. |

| Ly and Dennehy 2007 [39] | To examine ED management of pediatric asthma and if it followed national guidelines. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | USA | 141 patients (1–17 years) who presented to the ED with asthma. | Guidelines for discharge communication were not followed consistently. About two thirds (67.4%) did not receive asthma device training, 80.1% did not receive a written action plan, and 50% of patients over the age of six did not receive a peak flow meter. |

| Sarsfield et al. 2013 [48] | To determine if follow-up care and activity limitations were included in discharge information provided for head injuries. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | USA | 204 children (2–18 years) who presented to the trauma center with minor head injuries, traumas, or concussions. | 95% of patients were informed about follow-up care and 82% received information about anticipatory guidance. |

| Upchurch et al. 2015 [56] | To determine if a concussion-based intervention improved discharge communication provided in the ED. | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort | USA | 497 children who presented to the pediatric ED between 2004 and 2012 with a sports-related concussion. | 66% of patients received appropriate discharge communication, which improved to 75% after 2010 (p = 0.179). Referrals to specialists significantly improved after 2010 (p < 0.001). |

| Samuels-Kalow et al. 2015 [97] | To determine the impact of “teach-back” in the ED based on health literacy level. | Interviews | Qualitative | USA | 31 interviews with parents of pediatric asthma patients in the ED (15 with limited literacy); 20 interviews with adult ED asthma patients (12 with limited literacy). | Across all participants and health literacy levels, asthma teach-back in the ED was viewed as an important way to confirm understanding of information, helped to reinforce key messages, and improved communication with health care providers. |

| Samuels-Kalow et al. 2016 [96] | To identify barriers and facilitators of the ED discharge communication process. | Interviews | Qualitative | USA | 31 interviews with parents of pediatric asthma patients in the ED (15 with limited literacy); 20 interviews with adult ED asthma patients (12 with limited literacy). | Participants appreciated simple visuals and language, consistency in terms used, and having dedicated time for discharge communication during the ED visit. Some parents of pediatric patients also discussed feeling insecure disclosing to health care providers when they did not fully understand the content of discharge communication. |

| Leickly et al. 1998 [95] | To examine factors that affect adherence to asthma treatment plans. | Interviews and chart review | Qualitative | USA | 344 English- and Spanish-speaking children (4–9 years) presenting at inner city ED with asthma. | Interviews indicated that parents might overuse the ED due to lack of planning for acute asthma symptoms. Asthma management follow-up was also influenced by PCP recommendation of scheduling an appointment. |

| Boychuk et al. 2006 [70] | To develop and implement an ED-based, asthma education program based on National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEEP) guidelines. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | Phase 1: 590 patients (< 18 years) Phase 2: 313 patients (< 18 years) | Asthma education can be provided effectively in ED. The intervention was also effective at connecting ED and community physicians to encourage asthma education and treatment with patients. |

| Considine and Brennan 2007 [78] | To examine the effect of a staff educational intervention on discharge advice provided to parents leaving the ED. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | Australia | 40 parents of children who presented to the ED with fever. | Structured education of ED nurses through two 30-min tutorials improved discharge advice given to parents. |

| Kruesi et al. 1999 [87] | To examine if injury prevention education could reduce access to lethal means. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | 103 parents who brought a child (6–19 years) to the ED to receive a mental health assessment (control: n = 62, intervention: n = 41). | The intervention group was significantly more likely to take action to limit access to prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, and firearms (p ≤ 0.05). |

| O’Neill-Murphy et al. 2001 [88] | To examine if a fever education intervention could help reduce parent anxiety and improve home management of fevers. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | 87 parents of children (3 months–5 years) who presented to the ED with a fever (control: n = 43, intervention: n = 44). | Both groups had reduced anxiety levels at post-test. There were no significant differences in knowledge scores between groups. |

| Patel et al. 2009 [76] | To improve parent recall of verbal discharge information with the use of a bilingual discharge facilitator. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | 325 English- or Spanish-speaking parents who brought a child (3 months–18 years) to the ED (control: n = 270, intervention: n = 192). | Parents in the discharge facilitator group could recall more signs and symptoms than standard discharge group (mean 4.3 vs 3.3; mean difference 1.0) |

| Petersen et al. 1999 [77] | To determine if an asthma education tool improved rates of follow-up care. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | Children (5–16 years) who presented to the ED with asthma (before: n = 114; after: n = 97). | There was a significant increase in proportion of children told to return for follow-up (54% to 81%, p = < 0.0001), but there was no difference in follow-up rates (7% to 6%) following implementation of the tool. |

| Porter et al. 2006 [80] | To determine the effectiveness of an asthma information kiosk on parent satisfaction, and clinician use of the kiosk information. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | 273 parents were included in the implementation phase study (control: n = 131, intervention: n = 142). | Parents’ satisfaction with health care providers did not increase with the use of the kiosk (0.8 vs. 0.7). When clinicians used the kiosk information, there were fewer reported issues (0.6 vs. 1.1). |

| Rotheram-Borus et al. 2000 [91] | To implement a specialized ED and outpatient suicide prevention intervention to decrease suicidal behaviors. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | 140 females (12–18 years) who had attempted suicide and their parent presented in the ED (control: n = 75, intervention: n = 65). | Rates of reattempts (n = 11 control, n = 6 intervention) and suicide ideation across both groups were consistently low during the 18 months follow-up. |

| To et al. 2010 [79] | To determine if an asthma information card would improve asthma management in the ED. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | Canada | 432 children (2–17 years) who presented to the ED with an acute asthma exacerbation (control: n = 278, intervention: n = 154). | Use of an asthma management reminder card improved the provision of oxygen (p = 0.00074), salbutamol (p ≤ 0.0001), ipratropium bromide (p = 0.0161), and oral corticosteroids (p ≤ 0.0001) in the ED. However, there were no significant differences in providing information about asthma (p = 0.5940) or follow-up visits (p = 0.0705) between groups. |

| Williams et al. 2013 [75] | To improve parents’ understanding of their child’s asthma severity during the ED visit. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | Children with asthma aged 1–17 years (controls: n = 216, intervention: n = 70). | Parents who received the asthma education intervention were more likely to attend follow-up care in the week following discharge (p ≤ 0.0001). |

| Wood et al. 2017 [71] | To determine if providing video discharge communication would improve parents’ knowledge. | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies) | USA | 83 parents of children (up to 21 years) who presented to the ED with gastroenteritis, fever, or bronchiolitis (control: n = 42, intervention: n = 41). | Across the three illness presentations, parents who received the intervention had significantly higher knowledge scores compared to parents who received standard discharge communication (gastroenteritis 73% vs. 57%, p = 0.005; fever 76% vs. 69%, p ≤ 0.001; bronchiolitis 64% vs. 49%, p = 0.025). |

| Gorelick et al. 2006 [62] | To compare low, medium, and high intensity asthma interventions on ED return visits and quality of life (QOL). | RCT | RCT | USA | 352 children who presented to the ED with acute asthma (control: n = 116, intervention group 1: n = 118, intervention group 2: n = 118). | No differences between study groups for return visits to the ED (17.3% vs. 17.9% vs. 19.2%, p = 0.94). |

| Stevens et al. 2012 [66] | To determine the effect of a childhood pain management video on parents’ knowledge and pain meds use following ED discharge. | RCT | RCT | USA | 100 parents of children (1–18 years) who presented to the ED with pain (control: n = 41, intervention: n = 59). | The intervention group had significantly improved knowledge of pain (p = 0.04), the impact of pain on function (p ≤ 0.01), and misconceptions around pain medications (p ≤ 0.01). |

| Baker et al. 2009 [64] | To determine if an educational video about home management of fevers could reduce return ED visits. | Randomized cohort study | RCT | USA | 280 parents who presented to the ED with a child (3–36 months) with a fever (control: n = 140, intervention: n = 140). | Intervention group had significantly improved responses to appropriate knowledge and treatment of fever (p ≤ 0.0001). No difference between groups for return ED visits (p = 0.46). |

| Zorc et al. 2003 [82] | To determine if scheduling follow-up appointments during the ED visit improves follow-up rates. | Randomized trial | RCT | USA | 286 parents with children (2–18 years) who were treated for asthma and discharged from the ED. Eight potential participants were excluded; leaving 139 participants included in each the control and the intervention group. | The intervention group was more likely to follow-up with a primary health care provider (64% vs. 46%, p = 0.003), and in a shorter time frame (13 vs. 54 days, p = 0.004). |

| Asarnow et al. 2011 [92] | To evaluate a suicide prevention intervention to improve use of outpatient care and decrease suicide attempts. | RCT | RCT | USA | 181 suicidal youths (10–18 years) (control: n = 92, intervention: n = 89). | Intervention group significantly more likely to attend outpatient care (92% vs. 76%, p = 0.004), but was not significantly associated with decreased suicide attempts (13% vs. 13%). |

| Bloch and Bloch 2013 [67] | To determine if a video providing discharge information improved parents’ knowledge of the ED visit and follow-up care. | RCT | RCT | USA | 436 parents who presented to the ED with a child (< 18 years old) with asthma, fever, or vomiting/diarrhea (control: n = 220, intervention: n = 216). | Intervention group had significantly higher knowledge scores at (12.2 vs. 8.9, p < 0.0001) and following (11.1 vs. 7.9, p ≤ 0.0001) ED visit. |

| Brooks et al. 2017 [90] | To determine how useful symptom-specific discharge instructions were to parents in managing their child’s concussion symptoms and activities. | RCT | RCT | USA | 114 parents of children (7–17 years) who presented to the ED with a concussion (control: n = 56, intervention: n = 58). | The intervention group found the discharge instructions significantly more helpful compared to the control group (p < 0.05). Although the control group were more likely to contact their PCP regarding concussion follow-up care (p < 0.05). |

| Chande et al. 1996 [69] | To determine if educating parents could reduce unnecessary ED visits. | RCT | RCT | USA | 130 parents who presented to the ED with a child with a minor illness (control: n = 61, intervention: n = 48). | Six months following the initial ED discharge, there was no significant difference between groups returning to the ED (30% vs. 26%, p = 0.68). |

| Cushman et al. 1991 [86] | To encourage the purchase of helmets following a visit to the ED with a child with a bike injury. | RCT | RCT | Canada | 334 parents who presented to the ED with a child who had a bike injury (control: n = 173, intervention: n = 161). | There was no significant difference in helmet purchases between groups (9.3 vs. 8.1, p = 0.69). |

| Delp and Jones, 1996 [60] | To determine if parent comprehension was improved with the use of cartoon illustrations with discharge information. | RCT | RCT | USA | 234 patients and parents (of children under 14 years) who were released from the ED and had a telephone (control: n = 129, intervention: n = 105). | The intervention group was more likely to have read the discharge information (98% vs 79%, p ≤ 0.001), properly answer questions about care (46% vs 6%, p ≤ 0.001) and adhere to discharge information (77% vs. 54%, p ≤ 0.01). |

| Ducharme et al. 2011 [61] | To determine if providing written action plan and a prescription improved adherence to asthma controller medication. | RCT | RCT | Canada | 219 children diagnosed with asthma who had received albuterol nebulization treatment at least once, and were discharged home with albuterol and fluticasone in metered-dose inhalers (control: n = 110, intervention: n = 109). | Compliance with asthma discharge information was comparable between groups at 14 days, but by 4 weeks post-ED visit, the intervention group had double the compliance rate of the control group (mean group difference 16.1%). |

| Hart et al. 2015 [72] | To determine if an interactive online education resource improved parents’ knowledge of fever. | RCT | RCT | Canada | 203 parents of children who presented to the ED with fever (control: n = 67, interactive website intervention: n = 66, standard website intervention = 70). | Parents who received either intervention had significant improvements in mean knowledge scores compared to control group (3.9 vs. 3.5 vs. 0.2, p ≤ 0.001). No differences in knowledge scores between the two intervention groups (p = 0.55). |

| Hussain-Rizvi et al. 2009 [81] | To determine if parents providing MDIS with physician supervision improved compliance with asthma home management. | RCT | RCT | USA | 86 children (1–5 years) who had presented to the ED with acute asthma exacerbation (control: n = 46, intervention: n = 40). | Outcomes were comparable between groups. However, the intervention group had better MDIS use following ED discharge (95.0% vs. 71.7%, p = 0.04). |

| Isaacman et al. 1992 [74] | To determine if offering verbal or verbal and written discharge information would improve information recall. | RCT | RCT | USA | 197 parents of a child with otitis media (control/usual care: n = 84, standardized verbal: n = 52, standardized verbal + written intervention: n = 61). | Parents in all groups improved recall of medication data, signs of improvement, and worrisome signs from exit interview to day 1 and 3. Standardized instruction groups performed significantly better than control in all areas except medication data at all time points. Verbal + written group significantly better than written alone on signs of improvement at exit interview only (56.9% vs. 25.3%; p < 0.05) |

| Ismail et al. 2016 [68] | To determine if providing video discharge information would improve recall and comprehension. | RCT | RCT | USA | 63 parents who presented to the ED with a child with either a fever or closed head injury (control: n = 32, intervention: n = 31). | Intervention group had higher post-test scores compared to control group (88.89 vs. 75.73, p ≤ 0.0001). |

| Jones et al. 1989 [84] | To increase compliance with follow-up care through the use of health belief model (HBM) clinical nursing interventions. | RCT | RCT | USA | 59 patients who presented to the ED with otitis media (control: n = 19, HBM phone intervention: n = 12, HBM clinical intervention: n = 14, HBM phone and clinical intervention: n = 14). | All intervention groups had higher rates of scheduling (90% vs 26%, p ≤ 0.001) and keeping (73% vs. 21%, p ≤ 0.001) a follow-up appointment compared to the control group. No significant differences in compliance rates between the three intervention groups. |

| Komoroski et al. 1996 [93] | To determine the effectiveness of two interventions provided prior to ED discharge aimed at improving rates of follow-up care. | RCT | RCT | USA | 253 patients or parents of pediatric patients who presented to the ED with nonurgent conditions which required follow-up (control: n = 89, simple intervention: n = 85, intense intervention: n = 79) | Participants in the intense intervention group had the highest follow-up rates. The simple intervention group (p < 0.001) and the intense intervention group (p < 0.001) both had significantly higher rates compared to the control group. Those in the intense intervention group also had higher follow-up rates compared to the simple intervention, but it was not statistically significant. |

| LeMay et al. 2010 [73] | To test an education intervention about pediatric pain 24 h following ED discharge. | RCT | RCT | Canada | 195 parents who visited the ED with a child with a musculoskeletal injury, burn, deep laceration, or acute abdominal pain (control: n = 97, intervention: n = 98). | No differences between groups for pain intensity at triage (5.4 vs. 5.11) and 24 h post-discharge (3.3 vs. 3.1). No differences in the level of unpleasantness experienced at triage (4.9 vs. 4.8) or 24 h post triage (3.0 vs. 3.1) (p = 0.05 for all tests). |

| Macy et al. 2011 [65] | To determine if a discharge communication video about asthma improved parents’ knowledge. | RCT | RCT | USA | 129 parents of a child (2–14 years) who presented to the ED with asthma (control: n = 67, intervention: n = 62). | Parents with low literacy had improved asthma knowledge in both the intervention and control groups (p ≤ 0.0001). Parents with adequate health literacy had improved asthma knowledge in the intervention group, but this was not significant. |

| Scarfi et al. 2009 [83] | To determine if providing an allergen skin test for asthma and its results during an ED visit would improve follow-up rates at an asthma clinic. | RCT | RCT | USA | 77 children (2–12 years) who presented to the ED with an acute asthma exacerbation (control: n = 39, intervention: n = 38). | The intervention group was 2.6 times more likely to schedule and maintain their follow-up appointments at an asthma clinic. |

| Smith et al. 2006 [90] | To determine if providing asthma coaching and incentives would improve rates of follow-up care with a PCP. | RCT | RCT | USA | 92 parents who presented to the ED with a child with an acute asthma exacerbation (control: n = 42, intervention: n = 50). | Following ED discharge, there were no differences in follow-up rates between intervention and control groups (22% vs. 23.8%, p = 0.99). |

| Sockrider et al. 2006 [89] | To test a tailored asthma management intervention to improve parent confidence and reduce return ED visits. | RCT | RCT | USA | 464 parents with children (1–18 years) who presented to the ED with an acute asthma exacerbation (control: n = 201, intervention: n = 434). | Following ED discharge, the intervention group had higher confidence in preventing their child’s asthma symptoms (p = 0.05) and preventing symptoms from getting worse (p = 0.03). The intervention group also had significantly lower rates of return ED visits for intermittent asthma (odds ratio = 0.32, 95% CI 0.12–0.88). |

| Yin et al. 2008 [63] | To determine if the use of illustrated health literacy interventions helped decrease liquid medication dosing errors. | RCT | RCT | USA | 245 children (30 days–8 years) and parents who were given a prescription for a liquid medication in the pediatric ED (control: n = 121, intervention: n = 124). | The intervention group had fewer daily dosing errors (0% vs. 15.1%, p = 0.007) and higher use of standardized dosing instrument for daily (93.5% vs. 71.7%, p = 0.008) and as-needed (93.7% vs.74.7%, p = 0.002) dosing. |

| Zorc et al. 2009 [85] | To develop and test a 3-part asthma intervention to improve rates of follow-up care. | RCT | RCT | USA | 439 parents with an asthmatic child (1–18 years). Six participants were excluded, leaving 216 participants in the control group and 217 participants in the intervention group. | The intervention group was more likely to support and believe in the benefits of seeking follow-up care with a PCP, but there were no significant differences in follow-up care rates between groups. |

CI confidence interval, ED emergency department, MDIS metered-dose inhaler spacers, RCT randomized controlled trial, PCP primary care provider

Table 2.

Description of intervention studies (n = 44)

| Author, publication year | Intervention type | Description of intervention | Intervention target | Who delivered intervention | Description of primary outcome | Direction of effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Intervention function | ||||||

| Baker et al. 2009 [64] | Education | Parents watched a video (11 min) about how to manage child’s fever at home. | Parent | Research team | Reducing return ED visits. | + |

| Bloch and Bloch 2013 [67] | Education | Parents watched a video (3 min) regarding their child’s illness in addition to standard discharge communication. Parents were provided the opportunity to ask clarifying questions to a clinician prior to leaving the ED. | Parent | Medical student volunteers | Parent comprehension of treatment plan and follow-up information. | + |

| Boychuk et al. 2006 [70] | Education | Parents watched a video (6 min) outlining asthma and asthma management techniques, in addition to conversations with ED staff about the importance of asthma management and treatment, a review or written or verbal instructions, and a demonstration of how asthma affects the lungs. Health care providers also received asthma education. | Patient, parent, and health care provider | Research team, and physicians | Improving asthma management through written action plans and medications. | + |

| Brooks et al. 2017 [90] | Education | Parents received written discharge instructions specific to their child’s concussion level and symptoms they experienced. | Parent | Research team | Use of discharge instructions. | + |

| Chande et al. 1996 [69] | Education | Parents watched a video (10 min) and received an information booklet on pediatric illnesses. A research assistant reviewed the booklet with parents and answered parent questions. | Parent | Research team | Reducing return ED visits. | – |

| Cheng et al. 2002 [22] | Education | Caregivers received education about asthma and a demonstration of an appropriate MDIS technique during the ED visit. | Parent | Discharge facilitator and ED clinicians | Improving rates of MDIS use. | + |

| Considine and Brennan 2007 [78] | Education | Nurses in the ED attended two tutorials that reviewed the physiology and treatment of fevers to improve the content of discharge communication provided to parents. | Health care provider | Online tutorial | Information caregivers received about fever as part of their discharge instructions. | + |

| Delp and Jones 1996 [60] | Education | Parents received cartoon wound care instructions in addition to standard written instructions. | Patient and parent | Physicians | Patient compliance with ED discharge instructions. | + |

| Hanson et al. 2017 [29] | Education | Patients and parents received cartoon pain management information. | Patient and parent | Research team | Parent recall of information provided in the cartoon. | + |

| Hart et al. 2015 [72] | Education | Parents received one of two interventions. One intervention group received access to a standard fever education website. The second intervention group received accessed to an interactive fever education website. | Parent | Research team | Parent knowledge of fever. | + for both interventions |

| Hussain-Rizvi et al. 2009 [81] | Modeling | Physician demonstrated for the parent how to use of the albuterol MDIS. The parent then provided the treatment while under observation. | Parent | Physicians | Adherence to MDIS use at home following ED discharge. | + |

| Gaucher et al. 2011 [28] | Education | Parents who notified the triage nurse they were leaving without being seen by a physician received information about their child’s illness and when to seek additional care and return to ED | Parent | Triage nurse | Rates of return ED visits within 48 h of the initial visit. | + |

| Isaacman et al. 1992 [74] | Education | Parents whose child presented with otitis media received one of two interventions. One intervention group received verbal instructions. The second intervention group received the same verbal instructions in addition to a written copy of discharge communication. | Parent | Residents and medical students | Parent recall of medications and signs to monitor at home. | + for both interventions |

| Ismail et al. 2016 [68] | Education | Parents watched a video (3–5 min) about fever or closed head injury in addition to standard verbal discharge communication. Parents were also given the opportunity to ask questions to clinicians prior to leaving ED. | Parent | Clinicians | Parent comprehension of diagnosis and follow-up care. | + |

| Kaestli et al. 2015 [55] | Education | Parents received written information regarding drug dosing, indication, and frequency of administration. | Parent | Research team | Improving comprehension of prescribed drug usage. | + |

| LeMay et al. 2010 [73] | Education | Parents received a booklet about pain management and a bookmark printed with pain scale information in addition to standard care. | Parent | Research team | Children’s pain and parents’ perceptions of pain management 24 h following ED visit. | No change |

| Macy et al. 2011 [65] | Education | Parents watched a video (20 min) about an asthma management. | Parent | Health care providers and research assistants | Parent knowledge of asthma information provided during ED visit. | + |

| Patel et al. 2009 [76] | Education | Parents received verbal reinforcement of discharge communication from a discharge facilitator in addition to standard written information. | Parent | Discharge facilitator | Parent recall of discharge instructions. | + |

| Petersen et al. 1999 [77] | Education | Parents received personalized written asthma information about signs of asthma attack, medication doses, and following up with a PCP within 72 h of the ED visit. | Parent | Respiratory care providers and clinicians | Compliance with attending follow-up appointment and length of time before appointment was made. | No change |

| Porter et al. 2006 [80] | Environmental Restructuring | Parents used an interactive asthma kiosk to document asthma symptoms and care needs. Information generated from the kiosk was shared with ED clinicians through a reminder summary on chart. | Parent and health care provider | Research team and clinicians | Parent satisfaction with care and providers’ adoption of guideline-endorsed process measures. | No change |

| Stevens et al. 2012 [66] | Education | Parents watched a video (6 min) that provided information about common myths and misunderstandings surrounding home management of pain. | Parent | Research team | Parent use of pain management information provided at the ED following discharge. | + |

| Thomas et al. 2017 [47] | Education | Parents received verbal reinforcement of written discharge instructions. | Parent | Research team | Parent understanding of discharge instructions. | + |

| To et al. 2010 [79] | Environmental Restructuring | Health care providers received an evidence-based asthma guideline reminder card. | Health care provider | Research team | Changes to asthma medication, asthma education, and discharge planning provided to families in the ED. | +/ No change/ No change |

| Waisman et al. 2005 [50] | Education | Parents received a written information sheet regarding their child’s illness. | Parent | Physicians | Parent understanding of discharge instructions. | + |

| Williams et al. 2013 [75] | Education | Parents received an illustrated scale and were educated about their child’s asthma severity score along with standard discharge communication. | Parent | Research team and ED clinical providers | Parent compliance with scheduling follow-up care. | + |

| Wood et al. 2017 [71] | Education | Parents watched a video (3–5 min) specific to their child’s illness, in addition to standard verbal discharge communication and a written information sheet. | Parent | ED nurses from an evidence-based practice project | Parent comprehension of their child’s illness and treatment. | + |

| Zorc et al. 2003 [82] | Enablement | Researchers with the study brought parents to a phone in an attempt to get them to schedule follow-up care with their PCP. | Parent | Research team | Parent follow-up with PCP and improvements in asthma-related health outcomes and medication use. | + |

| 2 Intervention functions | ||||||

| Cushman et al. 1991 [86] | Education + Enablement | Physicians received a cue card with information to counsel parents on helmet use. Parents were provided with pamphlets and a card with the names and addresses of retailers selling helmets to take home to encourage the use and purchase of helmets. Follow-up phone calls were made to check if helmets had been purchased and to provide additional counseling, if needed. | Parent | Physicians | Measuring the purchase and use of bicycle helmets. | No change |

| Jones et al. 1989 [84] | Education + Enablement | Parents received one of three interventions. Group 1 received standard care in addition to a follow up telephone call. Group 2 received counseling during the ED visit with no follow-up call. Group 3 received both counseling in the ED and a follow-up call. | Parent | Research nurse and clinical nurse | Compliance with scheduling and attending a follow-up appointment based on a referral recommendation. | + |

| Kruesi et al. 1999 [87] | Education + Environmental Restructuring | Parents were informed of their child’s increased risk of suicide. Staff also educated and problem solved with parents to try and reduce suicide risk by limiting access to lethal means. Additionally, a safe disposal site was created for parents to encourage the removal of guns from the house. | Parent | ED staff | Reducing access to lethal means. | + |

| O’Neill-Murphy et al. 2001 [88] | Education + Modeling | Parents received a review of written fever information, had a discussion to have their questions answered, and received instructions and a demonstration of proper thermometer use. | Parent | Research team | Parent anxiety and rate of return ED visits for fever. | + |

| Pizarro et al. 1979 [39] | Education + Enablement | Following administration of oral rehydration fluid at the hospital, parents were sent home with the oral rehydration solution and were instructed of signs to monitor that would require a return visit to the ED. | Parent | ED nurses and interns | Reducing hospital length of stay. | + |

| Philips 2009 [38] | Education + Environmental Restructuring | Parents received asthma education packages, asthma discharge plans, and were provided with a spacer if their child did not have one. | Parent | ED staff | Improving parent’s treatment and home management of asthma. | + |

| Sauer et al. 2012 [45] | Education + Environmental Restructuring | Parents received written discharge information and access to a telephone hotline to assist with scheduling follow-up care in orthopedics. | Parent | Physicians | Reducing rates of ED use. | + |

| Scarfi et al. 2009 [83] | Education + Environmental Restructuring | Children in the intervention group received a skin allergen to determine allergens that could be linked to an asthma episode. Parents were provided with a copy of the allergen test to encourage follow-up care. | Patient and parent | Clinicians and administrator of the skin allergen test | Attending follow-up appointment. | + |

| Yin et al. 2008 [63] | Education + Enablement | Parents received illustrated resources about proper dosing of liquid medication. A research assistant reviewed resources with parents and had parent demonstrate how they would administer a medication dose. | Parent | Research team | Parent knowledge of medication dosing accuracy. | + |

| Zorc et al. 2009 [82] | Education + Environmental Restructuring | Parents watched a video and were mailed a letter to schedule follow-up care for their child’s asthma. Parents of children with persistent asthma also received an additional letter to encourage follow-up with a PCP. | Parent | Research team | Parent compliance with scheduling and attending follow-up appointment. | No change |

| Komoroski et al. 1996 [93] | Incentivization + Environmental Restructuring | Parents received one of two interventions. The first intervention group had their follow-up appointment booked for them and received a written reminder. The second intervention group received the same intervention as the first group with the addition of a mailed reminder one week prior to the appointment, a reminder phone call the day before the appointment, a work excuse, assistance with transportation to and from the appointment, and receiving child care. | Parent | Research team | Parent compliance with attending follow-up appointment. | + |

| 3 Intervention functions | ||||||

| Ducharme et al. 2011 [61] | Education + Enablement + Environmental Restructuring | Parents received a structured written action plan with information about asthma management, treatment, in addition to an asthma assessment tool and a prescription. A valved spacer and MDIS were also provided for children. Surveys and/or telephone calls were completed to determine parents’ completion of educational classes, follow-up visits with PCP and number of return visits to the ED. | Parent | ED physicians and pharmacists | Adherence to prescribed asthma medications four weeks following ED discharge. | + |

| Gorelick et al. 2006 [62] | Education + Enablement + Environmental Restructuring | Parents received one of two interventions. Group one received standardized information in addition to having information faxed to their PCP, and phone calls to offer assistance scheduling the follow-up care with PCP. The second group received the same care as intervention group one, in addition to being assigned a nurse or social worker to provide home visits, and additional education and links to community services. | Parent | Research team and home health care staff | Rates of return ED visits six months following initial ED asthma visit. | No change |

| Rotheram-Borus et al. 2000 [91] | Enablement + Training + Modeling | ED staff and health care providers received additional training surrounding mental health. Patients and parents were shown a video (20 min) in the ED about mental health treatments. Patients and parents also received therapy sessions, including identifying positive coping mechanisms, and outpatient treatments. Outpatient treatments included additional therapy sessions to use problem solving and roleplaying techniques to assist with family issues and future suicidal feelings. | Patient, parent and health care provider | Research team, ED staff and clinicians | Reducing suicidal behavior. | + |

| Smith et al. 2006 [90] | Enablement + Training + Incentivization | An asthma coach worked with parents to assist with their asthma concerns. Coaches also provided information about the importance of asthma follow-up care with a PCP and helped parents identify and address barriers to follow-up. Additionally, parents received a monetary incentive for attending follow-up care appointment after ED visit. | Parent | Asthma coach | Attending asthma planning visit with PCP. | No change |

| Sockrider et al. 2006 [89] | Education + Enablement + Environmental Restructuring | Asthma coaches utilized a computer-based resource that provided a customized written asthma action plan that was provided to parents and sent to their PCP. Asthma coaches conducted follow-up calls with parents to ensure follow-up with their PCP and to reinforce messages from the asthma plan. A phone line was also provided so parents could call with asthma management questions. | Health care provider and parent | Clinicians, respiratory care practitioners, and a layperson | Parent confidence managing asthma and reducing ED visits. | + |

| 4 Intervention functions | ||||||

| Asarnow et al. 2011 [92] | Education + Environmental Restructuring + Restriction + Training | Family members received education and training about the importance of mental health, outpatient treatment, how to provide support and ways to remove access to potential lethal means in the house. Patients and family members also received therapy sessions, including how to identify potential triggers and how to develop safe and healthier coping mechanisms for potential future suicidal thoughts. | Patient and parent | Clinicians | Rates of follow up outpatient treatment after ED discharge. | + |

ED emergency department, MDIS metered-dose inhaler spacers, PCP primary care provider

Quality of the evidence

Study quality was assessed using critical appraisal checklists from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [22]. The majority of the cross-sectional studies were of moderate quality (6/8 appraisal criteria present). The two appraisal questions that had mixed results were related to identifying and addressing potential confounding. Only a third of the studies (n = 9; 32%) identified possible confounders and even fewer studies noted how these confounders were adjusted for during data analysis (n = 8; 29%).

The 24 RCT were appraised using the Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials and 46% of the studies (n = 11) did not clearly identify if a true randomization method was used. Additionally, only four RCT clearly stated how allocation concealment was used during the study [60–63].

The Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies was used for 11 studies in the review. These quasi-experimental studies (n = 11) scored consistently well across all of the appraisal checklist criteria, with the exception of concerns about composition of the comparison groups. We found that just over half of studies (n = 6; 55%) had at least one or more key variables with a 10% difference or more between the study groups. These differences raise some concerns about potential selection bias.

Finally, the three included qualitative studies were assessed using the Checklist for Qualitative Research. Deficits were identified in all studies regarding reporting of the philosophical perspective guiding the study methods and clearly describing the role of the researchers within the studies.

Types of interventions

We identified 44 discharge communication interventions among the 75 included studies in the review (Table 2). Interventions were comprised of one to four intervention function types, according to the BCW (Table 3) [20]. The heterogeneity of intervention descriptions and outcome measures limited our ability to carry out meta-analysis.

Table 3.

Behavior change wheel domains identified in intervention studies (n = 44)

| Authors, publication year | Illness presentation | Identified BCW domains | Direction of Effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Incentivization | Training | Enablement | Modeling | Environmental restructuring | Restriction | |||

| Baker et al. 2009 [64] | Fever | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Bloch and Bloch 2013 [67] | Asthma, fever, vomiting, or diarrhea | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Boychuk et al. 2006 [70] | Asthma | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Brooks et al. 2017 [90] | Concussion | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Chande et al. 1996 [69] | Minor illnesses | ✓ | – | ||||||

| Cheng et al. 2002 [27] | Asthma | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Considine and Brennan 2007 [78] | Fever | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Delp and Jones 1996 [60] | Lacerations | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Hanson et al. 2017 [33] | Pain presentations | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Hart et al. 2015 [72] | Fever | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Gaucher et al. 2011 [32] | Various illnesses | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Isaacman et al. 1992 [74] | Otitis media | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Ismail et al. 2016 [68] | Fever and closed head injury | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Kaestli et al. 2015 [59] | Illnesses requiring prescription | ✓ | + | ||||||

| LeMay et al. 2010 [73] | Various injuries | ✓ | No change | ||||||

| Macy et al. 2011 [65] | Asthma | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Patel et al. 2009 [76] | Gastroenteritis | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Petersen et al. 1999 [77] | Asthma | ✓ | No change | ||||||

| Stevens et al. 2012 [66] | Pediatric pain | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Thomas et al. 2017 [51] | Mild traumatic brain injuries | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Waisman et al. 2005 [54] | Various illnesses | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Williams et al. 2013 [75] | Asthma | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Wood et al. 2017 [71] | Gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and fever | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Zorc et al. 2003 [82] | Asthma | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Hussain-Rizvi et al. 2009 [81] | Asthma | ✓ | + | ||||||

| Porter et al. 2006 [80] | Asthma | ✓ | No change | ||||||

| To et al. 2010 [79] | Asthma | ✓ | +/No change/No change | ||||||

| Cushman et al. 1991 [86] | Bike injury | ✓ | ✓ | No change | |||||

| Jones et al. 1989 [84] | Otitis media | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Pizarro et al. 1979 [43] | Diarrhea | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Yin et al. 2008 [63] | Various illnesses | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Kruesi et al. 1999 [87] | Mental health | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Phillips 2009 [42] | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Sauer et al. 2012 [49] | Fractures | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Scarfi et al. 2009 [83] | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Zorc et al. 2009 [85] | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | No change | |||||

| O’Neill-Murphy et al. 2001 [88] | Fever | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Komoroski et al. 1996 [93] | Minor, acute infections | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||||

| Ducharme et al. 2011 [61] | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | + | ||||

| Gorelick et al. 2006 [62] | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | No change | ||||

| Sockrider et al. 2006 [89] | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | + | ||||

| Smith et al. 2006 [90] | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | No change | ||||

| Rotheram-Borus et al. 2000 [91] | Mental health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | + | ||||

| Asarnow et al. 2011 [92] | Mental health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | + | |||

One intervention function type

The majority of studies (27/44) leveraged a single intervention function type and focused on a range of illness presentations (Table 3). Twenty-three of these involved an education (sharing information) function and primarily focused on evaluating different modes of delivering information about an illness or instructions for managing care at home [27, 32, 33, 51, 54, 59, 60, 64–78, 94]. Almost half (10/23) of these studies examined the use of technology, including video [64–71] or interactive websites [72, 78], as education delivery systems. Technology-enabled tools were used as stand-alone delivery systems [64–67, 72] or enhanced with written and/or face-to-face interaction with staff [68–70]. All studies targeting parents in the ED had a primary goal to increase knowledge [65–68, 71, 72], adherence to guidelines [70], or reduce unnecessary ED return visits [69]. Only one technology-enabled education type intervention targeted healthcare providers and evaluated the effect of two 30-min online tutorials for ED nursing staff focused on physiology and management of fever and febrile convulsions on the discharge advice given to parents [78]. Overall, technology-enabled education type interventions targeting parents had a positive impact on knowledge acquisition and adherence to guidelines, but were not effective in reducing unnecessary return visits to the ED (Table 2).

The remaining education type intervention studies (13/23) examined printed discharge communication alone [73, 77, 94] or with other supports such as cartoons [33, 60], verbal reinforcement of written instructions [51, 54, 59, 74–76], confirming appropriate understanding through observation of parent technique [27], or verbal instructions alone [32]. These studies targeted a range of illness presentations and examined a variety of outcomes including feasibility in the ED, improvement of parent’s knowledge, comprehension and/or recall about specific diagnosis, important signs and symptoms or treatment instructions, and adherence to instructions (including follow-up). Overall direction of effect was positive in most studies examining parent recall of discharge information [33, 51, 76] and knowledge and comprehension [54, 59, 60] (Table 2).

The four single intervention studies that did not involve education as an intervention function contained environmental restructuring (changing the physical and social context) [79, 80], modeling (providing an example for people to aspire to or imitate) [81], or enablement (increasing the means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity) [82]. Both environmental restructuring interventions targeted healthcare providers, focused on asthma, and included paper-based reminders. There was no significant change in provider behavior in either study (Table 2).

Two intervention function types