Abstract

Vascular changes during spontaneous headache attacks have been studied over the last 30 years. The interest in cerebral vessels in headache research was initially due to the hypothesis of cerebral vessels as the pain source. Here, we review the knowledge gained by measuring the cerebral vasculature during spontaneous primary headache attacks with the use of single photon emission tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRA) and transcranial Doppler (TCD). Furthermore, the use of near-infrared spectroscopy in headache research is reviewed. Existing TCD studies of migraine and other headache disorders do not provide solid evidence for cerebral blood flow velocity changes during spontaneous attacks of migraine headache. SPECT studies have clearly shown cortical vascular changes following migraine aura and the differences between migraine with aura compared to migraine without aura. PET studies have shown focal activation in brain structures related to headache, but whether the changes are specific to different primary headaches have yet to be demonstrated. MR angiography has shown precise changes in large cerebral vessels during spontaneous migraine without aura attacks. Future development in more precise imaging methods may further elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms in primary headaches.

Keywords: Neuroimaging, migraine, cortical spreading depression, vascular changes and headache

Introduction

The interest in vascular mechanisms in primary headaches started with the pivotal study by Ray and Wolff1 showing that mechanical, chemical and electrical stimulation of cranial vessels resulted in migraine-like headache.1 This led to the concept that there is dilatation of intracranial vessels during migraine attacks2 and subsequently result in activation of trigeminal nociceptors leading to the perception of pain.3 Although this concept has been greatly challenged,4 there have been extensive research focusing on the cranial vessels in migraine and other primary headaches.3,5 Cranial vessels can be studied in experimental animal models6 and by the use of headache provocation models using vasoactive neuropeptides covered elsewhere in this special issue (Cerebral hemodynamics in the different phases of migraine and cluster headache by JM Hansen and CJ Schankin). Investigation of vascular changes during headache attacks are obviously of great interest and with the development of non-invasive imaging methods several decades after the pivotal studies by Ray and Wolff,1 it became possible to study the intracranial vasculature in vivo during spontaneous headache attacks. This evolved into studying several different aspects of headache pathophysiology: (1) cortical blood flow studies, primarily during migraine aura, with single photon emission tomography (SPECT),7 positron emission tomography (PET)8 and later magnetic resonance imaging (MRI);9 (2) measuring intracranial vessel diameter changes indirectly with transcranial Doppler (TCD)10 and later directly with MRI;11 (3) indirectly measuring brain activity through local blood flow changes using PET12 and later MRI13 (Table 1). This review attempts to give an overview of non-invasive imaging techniques that have been used when assessing vascular changes in neurovascular headaches. We will only focus on describing vascular changes during spontaneous attacks, as neurovascular mechanisms of primary headaches, imaging findings in induced attacks with signaling molecules, resting state and functional imaging will be covered elsewhere in this journal edition. In addition, we will review the use of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in headache imaging as this is a relatively new non-invasive technique, which is promising as a tool to measure cortical changes during spontaneous attacks. We will discuss the existing findings in relation to headache pathophysiology and highlight the importance and challenges in measuring vascular changes during spontaneous attacks and point to future studies.

Table 1.

Comparison of practical issues for TCD, SPECT, PET and MRI.

| Doppler | SPECT | PET | MRI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Price | < 20,000 USD | ∼ 1 million USD | ∼ 2 million USD | ∼ 1 million USD |

| Availability | High | Moderate | Limited | Moderate |

| Temporal resolution | Continuously | 5–10 min (i.a adminstration) 45 min (inhalation) | Every 90 s | Every 1 s |

| Spatial | Low, only the insonated vessel | 8–10 mm | 5 mm | < 1 mm |

| Blood flow | Indirectlya | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Radiation exposure | No | Yes | Yes | No |

blood flow assessment assumes constant diameter in the insonated vessel.

i.a: intra-arterial; PET: positron emission tomography; SPECT: single photon emission computer tomography; TCD: transcranial Doppler; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Methods

TCD

TCD was introduced in 1982 by Aaslid et al.14 and has over the last 30 years been used to measure blood flow velocity (BFV) in the middle cerebral artery (MCA), the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) in headache and other neurological disorders such as stroke.15 This was achieved by changing the Doppler frequency from the previous conventional 5–10 MHz to 1–2 MHz for which the attenuation in bone is much less. Furthermore, to achieve in-depth recordings, an acoustic lens with a focal length of 5 cm was applied.14 It is necessary to assume that the angle between the ultrasound beam and the intracranial artery is sharp, between 0 and 30°, which results in a maximum error of 15%.14 The blood velocity V can then be calculated by measuring the Doppler shift via the equation: V = 0.039 × f, where f is the Doppler frequency shift. When measuring changes in velocity and assuming that the cerebral blood flow is constant, it is also possible according to Dahl et al.16 to retrieve the diameter change Δd of the MCA by the equation:

The Dahl et al. study proposed this equation following infusion of the vasoactive drug nitroglycerin, but assuming or controlling for no changes in CBF during a spontaneous migraine, this equation can also be applied for analysis of spontaneous attacks. One important issue is that changes in respiration frequency may often lead to either hypocapnia or hypercapnia and thereby to a compensational change in CBF, whereas the diameter of the large arteries such as the MCA remains constant, which results in a proportional change in MCA blood velocity. This effect can be corrected by measuring end-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure (PCO2), and computing a corrected velocity normalized to a standard PCO2 value of 40 mmHg as detailed by Markwalder et al.17

This correction factor may, however, underestimate the effect of CO2 on the velocity change in some conditions. In a human migraine model testing pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide 38 (PACAP38), which causes hyperventilation,18 the MCA diameter dilation measured with TCD and calculated with the above equation was 9.5% at the end of a 20-min infusion of 10 ρ m/kg/min PACAP38.18 However, the exact same dosage in a MR angiography study only induced an insignificant 0.8% change in MCA circumference at 20 min.19 Thus, it is possible that under some circumstances, such as infusion of vasoactive substances, there is an underestimation of the CO2 effect on the velocity change in intracranial arteries as assessed by TCD.

The fact that some primary headaches, such as migraine and cluster headache (CH), are often or always unilateral in presentation makes TCD an ideal tool. Vessels from both hemispheres can be assessed simultaneously, with the MCA velocities being nearly equal on the two sides in the healthy adult,14 and with day-to-day variations of only 16% being reported.20 Today, the TCD technique can be used at the bedside with a swift application of the ultrasound probes, which makes the system ideal for experimental monitoring during headache attacks.

SPECT

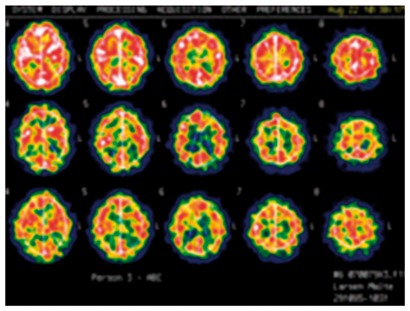

SPECT is a nuclear imaging technique, which measures and quantifies cerebral blood flow. In SPECT, a gamma ray is generated by the decay of a radioisotope, and directly or indirectly recorded by a gamma camera rotating around the head, which can then, via reconstruction algorithms, create two- or three-dimensional images. SPECT has a lower reconstructed spatial resolution from 8 to 10 mm,21 is less expensive, and is more widely available than PET (Table 1), and it utilizes radioisotopes with longer half-lives from hours to days, which makes it possible to have the radioisotopes delivered from an off-site supplier. Corrected CBF values, as with TCD, have to be corrected for significant changes in PetCO2 by 2% for each mmHg change in PetCO222 in order to measure changes related to changes occurring as a result of the headache attack and not due to a change in respiratory rate. Regional and global CBF measurements with 133Xe inhalation SPECT have been shown to be a reproducible method for assessing absolute changes17 with a day-to-day coefficient of variation of 8%,23 which makes it slightly better than MRI and approximately equal to PET.24 SPECT ictal recordings have been performed in headache research since the late 1970s to measure CBF alterations during migraine aura and migraine without aura attacks. The first studies used up to 16 collimated sodium iodide (NaI) crystal scintillation detectors placed over both hemispheres and thereby having a very limited spatial resolution.25 Later, a 254-channel instrument was developed leading to an improved spatial resolution.7 The temporal resolution can be brought down to 5–10 min using intra-arterial administration, but this is a relatively invasive procedure and therefore the use of SPECT in spontaneous headache attacks in larger studies has ceased over the last two decades.

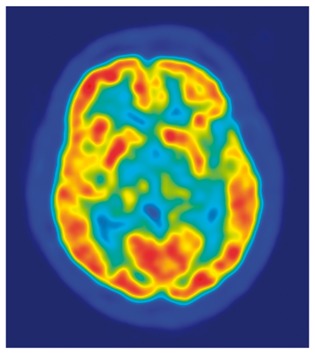

PET

PET can be used to study cerebral blood flow changes and spontaneous activation of brain areas. PET uses radiotracers that emit positrons when they decay. The emitted positron travels a few millimetres and then interacts with an electron, leading to annihilation of both particles, and thereby creation of two gamma rays going in opposite directions, which can then be detected simultaneously. Through this detection, a line of coincidence can be algorithmically constructed and the location of the original emitted proton can be topographically mapped from the detection of thousands of gamma ray pairs. The radiotracers used for PET can be physiologically relevant tracers such as [15O]H2O for CBF measurements26 or 2-[18F]flouro-2-deoxy-D-Glucose (FDG) for metabolism measurements.27 Specifically designed PET radiotracers can also be used to study pharmacological effects in the brain. As an example, Hostetler et al.28 showed in vivo quantification of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor occupancy by telcagepant in rhesus monkey and human brain using the PET radiotracer [11C]MK-4232, and showed a low receptor occupancy in the brain at an efficacious dose. Thus, it is unlikely that antagonism of central CGRP receptors are required for migraine efficacy, which point to extracerebral mechanisms being responsible for the generation of pain in migraine Similarly, Schankin et al.29 recently demonstrated in a PET study with the radiotracer (11)C-dihydroergotamine (DHE), which is chemically identical to pharmacologically active DHE, that DHE does not cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) during an induced migraine attack by a nitric oxide donor. Future studies may show the exact location of a CGRP or other signalling molecule antibodies used for migraine treatment.

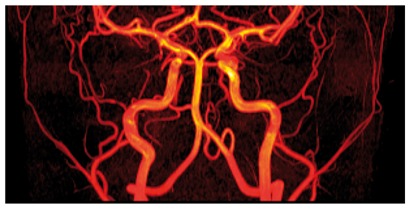

Magnetic resonance angiography

Three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) using the time-of-flight (3D-TOF-MRA) method has been one of the most important non-invasive approaches for in vivo examination of the human cephalic and cerebral arteries in headache studies during the last ten years.19,30–34 The 3D-TOF-MRA method provides high resolution (< 1 mm voxel size) images of the arteries in and the scanning requires no contrast agent,35 making it the method of choice when repeated measurements are required. The technique is based on flow-related enhancement of magnetically unsaturated blood entering stationary regions which have been previously magnetically saturated by multiple radio frequency (RF) pulses. Thus, the ‘fresh’ blood appears brighter compared to the background, enabling measurement of the luminal diameter and circumference of a given artery. This method was first introduced in the field of migraine research in 200834 and has since been used in several headache and migraine studies.11,19,32,33,36,37 The intra- and inter-observer variations using this method are less than 5%, while day-to-day and side-to-side variations in the luminal circumference of the MCA and the middle meningeal artery (MMA) are below 10%.37 Apart from non-contrast and radiation-free scans allowing repeated recordings, the advantages of this method are that it can measure several arteries simultaneously. Disadvantages of this method include the long image acquisition time compared to conventional computerized axial tomography (CAT-scan) angiography (i.e. acquisition time < 1 min), increasing the risk of movement artefacts and the audible noise produced by the scanner machine, which can aggravate pain in patients suffering from phonophobia during the migraine attack.

NIRS

NIRS is a non-invasive imaging modality that uses near-infrared light to measure changes in cerebral oxy- (HbO) and deoxy-hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations. It has become an effective tool to study normal and pathological brain physiology.38,39 Following the first proof-of-principle experiment in a human subject in 1977,40 the 1980s saw the development and clinical implementation of cerebral oximeters that use the NIRS technology to monitor trends in cerebral oxygenation, mainly for neuromonitoring during cardiovascular surgeries.41,42 In 1993, came the first demonstrations of the capability of NIRS to measure the functional hemodynamic response to cortical activation. 43–45

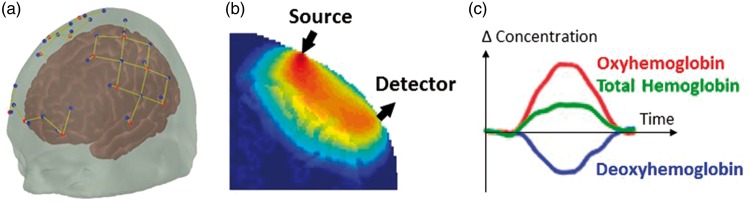

Functional NIRS (fNIRS) uses near-infrared light emitters – laser diodes or light-emitting diodes (LEDs) – at typically two wavelengths to illuminate the scalp. The light propagates diffusively through the scalp, skull and brain, and is partly absorbed by different chromophores, mainly the hemoglobin of the microvasculature blood. A photodetector – generally a photodiode or avalanche photodiode (APD) – is placed a few centimeters away from the source (3–5 cm) and detects part of the diffused light (Figure 1). As cerebral blood volume and oxygenation vary, the local absorption of light and therefore the detected light intensity change accordingly. Through models of light propagation in the head,46–48 and taking advantage of the differential absorption spectra of HbO and HbR, one can retrieve the concentration changes in these two hemoglobin species, and consequently total hemoglobin (Hbt). The normal hemodynamic response to the increased metabolic demand arising from neuronal activity is a focal increase in blood flow largely exceeding the increased oxygen consumption,49 resulting in the typical increase in HbO and decrease in HbR measured by fNIRS (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Array of NIRS sources and detectors (dots), and corresponding channels (lines). (b) Sensitivity profile of an fNIRS channel (source-detector pair) from Monte Carlo simulations. (c) Typical hemodynamic response to cortical activation measured by fNIRS.

Generally, an array of light sources and detectors is placed on the head, with each source-detector pair creating a measurement channel, and the combination of all channels allowing the retrieval of a two-dimensional map of the hemodynamic response to brain activation. Most traditional fNIRS systems employ optical fibers to deliver light to and from the head, but recent wearable devices instead place sources and detectors directly on the scalp.50–54 A variety of fNIRS devices are available commercially and in research settings,55 varying in flexibility and complexity, from simple forehead-only monitors to high-density whole-head systems.56

fNIRS offers many attractive features for a wide range of functional studies: relatively low-cost, non-invasiveness, portability, tolerance to motion, high temporal resolution, and functional contrast. Despite these assets, the modality also has limitations that need to be considered. First, its spatial resolution is roughly a couple of centimeters (roughly the source detector separation), although advances in instrumentation (e.g. high-density arrays) and image reconstruction algorithms (e.g. anatomical guidance57–59) can improve resolution potentially by a factor of 3.60 Second, as the light must travel back and forth through the scalp to reach the brain, measurements are only sensitive to the superficial cortex and are contaminated by the extracerebral vasculature that reflects systemic physiology. Multiple approaches have been proposed and are still being actively developed to minimize this contamination.61–63 Finally, because fNIRS is particularly suited to populations where subjects are moving or talking, it is prone to motion artifacts. Hardware and software methods can reduce this motion contamination,50,64 or partially correct for them during post-processing.65–67

The range of fNIRS applications and users has grown exponentially since the first demonstration of the technology,38,39 encompassing notably the fields of developmental neuroscience,68,69 psychiatric conditions,70 and neurological disorders and injuries such as migraine, epilepsy, movement disorders and stroke.71 It is particularly adapted to challenging populations that may not be amenable to other imaging modalities, including infants and children, neurocritical care patients, and freely-moving, behaving participants (testing of cognitive or executive functions, gait studies, speech studies). In addition to traditional evoked-response functional studies, some research has focused on the spontaneous oscillations in the fNIRS signals, driven either from neuronal or vascular fluctuations.72 In this context, fNIRS has been applied to study resting-state functional connectivity,73–76 and cerebral autoregulation and vascular reactivity.15,66,77

Studies of spontaneous attacks in migraine

TCD in migraine

A total of 17 studies of spontaneous migraine attacks have been published between 1990 and 2010.78 The studies have examined either migraine with or without aura or mixed populations of both migraine subtypes. Most of the studies reported no change in the BFV during spontaneous attacks versus outside of the attack. Measurement of the BFV has traditionally been used as a surrogate marker of dilation of the MCA in spontaneous migraine studies.17 This is possible if the change in cerebral blood flow (CBF) is known at the same time. SPECT studies have demonstrated that CBF changes during attacks of migraine with aura,7 but not without aura.79 It is therefore necessary to assess each migraine subgroup (i.e. with and without aura) separately to interpret possible MCA dilation based on BFV measurements. In a recent systematic review of TCD measurements of the MCA during spontaneous migraine attacks,78 data from all published studies were divided into three subgroups: (1) migraine with aura, (2) migraine without aura, and (3) mixed migraine (Table 2). In the migraine with aura group, four out of nine studies reported decreased BFV during migraine attacks, and four studies reported no change. In the migraine without aura group, only 2 out of 11 studies reported decreased BFV during attacks, whereas all others showed no change. Four studies reported data on mixed (with and without aura) migraine. Two studies reported decreased BFV, while two found no change. Overall, most studies showed unchanged BFV during spontaneous migraine attacks, but interestingly decreased BFV was more prevalent in migraine with aura studies.78 This trend was more pronounced in the earlier patients who were assessed with TCD during the attack.78 Six studies reported data on the comparison of pain side BFV versus the non-pain side BFV.78 Five of these studies reported no change, whereas one study reported significantly more decreased BFV in the MCA on the pain side in patients suffering from migraine without aura.78 The higher prevalence of BFV changes in migraine with aura in the earliest phase of the attack may suggest that TCD measurements in spontaneous migraine may be affected by changes in CBF. We cannot fully exclude that subtle CBF changes are also present in migraine without aura that could not be detected by conventional SPECT methods. Thus, inferences about vasodilation based on TCD measurement should be very cautious. In conclusion, existing TCD studies of migraine do not provide solid evidence for vasodilation (using BFV changes as a surrogate measure) during spontaneous attacks of migraine headache.

Table 2.

Studies investigating vascular changes during spontaneous migraine attacks using SPECT.

| Authors | Method | Patients | Recordings | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al.80 | SPECT 133xenon inhalation | 7 MA patients | MA attacks admission, 3–8 h, 20 to 24 h and 1 week later after the onset of symptoms | 19% reduced rCBF 3 h followed by 19% hyperperfusion in the affected hemisphere |

| Lauritzen et al.81 | SPECT 133xenon intraarterial injection | 9 FHM patients | MA attacks, series of rCBF studies, spaced by intervals of 5 to 10 min | Reduced rCBF. The hypoperfusion spread 2 mm/min over the hemisphere |

| Olesen et al.7 | SPECT 133xenon intraarterial injection | 9 MA patients + 1 MO patient. | MA attacks in 6 MA patients, series of rCBF studies, spaced by intervals of 5 to 10 min | The attacks were initiated by focal hyperemia in three patients followed by hypoperfusion gradually spread anteriorly in the course of 15 to 45 min. In four patients, a global hypoperfusion. was observed |

| Lauritzen et al.81 | SPECT 133xenon inhalation | 12 MO and 11 MA patients | Spontaneous attacks, MA patients investigated at a mean of 2 h into attacks, while MO patients were scanned at a mean of 7 h into the attack | Normal CBF during MO attacks in 12 patients. 8/11 MA patients displayed a unilateral region of hypoperfusion during attacks, while 3 had a normal flow pattern |

| Friberg et al.83 | SPECT 133xenon intraarterial injection | 3 FHM patients | FHM attacks | Focal hypoperfusion in the frontal lobe.In association with the rCBF changes the patients developed transient motor and/or sensory deficits |

| Olesen et al.7 | SPECT 133xenon inhalation | 12 MO patients | Food induced attacks. Up to four measurements | No change in CBF during MO attacks |

| Sakai and Meyer25 | SPECT 133xenon inhalation | 2 MA patients 3 MO patients 3 CH patients 7 TTH patients | Measurements during headache and 5–14 days later | The five MO/MA patients had a mean increase of 31% in total CBF compared to the interictal phase. The three CH patients had a mean increase of 45% in total CBF compared to the interictal phase. No increase in TTH patients |

| Ferrari et al.85 | SPECT using technetium Tc99m hexemethyl-propyleneamineoxime | 20 MO patients | Measurements outside an attack, during an attack and after attack treatment of with 6 mg of subcutaneous sumatriptan | No detectable focal changes of the rCBF during the different conditions |

| Kobari et al.86 | 133xenon inhalation | 18 MO patients 12 MA patients | During attacks (n = 9 MO and n = 7 MA) and without headache (n = 9 MO and n = 5 MA) | The rCBF increased in the fronto-temporal cortex, thalamus and basal ganglia. No significant diffences between MO and MA patients |

SPECT: single photon emission computer tomography; MA: migraine with aura; FHM: familial hemiplegic migraine; MO: migraine without aura; MA: migraine with aura; TTH: tension-type headache.

SPECT in migraine

In the late 1970s, SPECT studies began to emerge, which recorded regional CBF (rCBF) changes during spontaneous migraine attacks. Sakai and Meyer25 investigated migraine and CH patients during attacks compared to healthy controls as well as the interictal headache using the Xenon inhalation method with 16 detectors placed over both hemispheres and thereby having a very limited spatial resolution. The study compared three migraine without aura (MO) and two migraine with aura (MA) patients with serial images during the headache phase and when headache free.25 The authors found a mean increase of 31% in total CBF during attacks in these five patients with no apparent differences between migraine subtypes. Interestingly, one MA patient was described in detail, in which there was a local CBF reduction in the post-central gyrus corresponding to the contralateral loss of sensation.25 Three years later, the groundbreaking study by Olesen et al.7 was published, which used the intra-arterial Xenon 133 method and 254 channel equipment with repeated measurement by 5–10 min, which was able to detect that in migraine with aura, attacks were initiated by focal hyperemia and then an oligemia which gradually spread anteriorly in the course of 15 to 45 min.7 Thus, the study was the first to clearly show what may be the vascular footprint of cortical spreading depression in migraine aura. Then followed a series of studies, which replicated the findings.80–83 This was achieved using Xenon intraarterial injection and Xenon inhalation (Table 2). The studies from the Copenhagen group also showed that during familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM) attacks, a pattern similar to that of MA is observed.83 Furthermore, they observed no increase in CBF during MO attacks.82,84 This was also confirmed using the technetium Tc99m hexemethyl-propyleneamineoxime method.85 In contrast, Kobari et al.86 investigated MO and MA patients during attacks and observed that CBF increased by 20–40% in the fronto-temporal cortex, thalamus and basal ganglia, which may be due to cortical activation as a result of pain.87 In addition, they observed no differences between MO and MA patients, which is in contrast to the majority of studies, but similar to the Sakai study.25 The SPECT studies in migraine laid the foundation to describing the pathophysiological background behind migraine with aura and showed, in most cases, a clear difference in vascular alterations between spontaneous MO and MA attacks.

PET in migraine

To our knowledge, there have been a total of seven studies investigating spontaneous attacks with the PET technique (Table 3), and most of these studies have been recognised as pivotal studies, which moved the field of knowledge in migraine pathophysiology. The first study, which was in sharp contrast to the previous SPECT findings, was a result of an incident. A migraine without aura patient experienced a spontaneous migraine, while being in a PET scanner as a healthy subject undergoing 12 repeated measurements every 15 min during a visual test with a series of line drawings displayed at a rate of 2/s.88 Before the seventh scan, the patients experienced a headache fulfilling the criteria for MO, and without a clear aura prior or during the attack, except for the retrospective description by the patient 30 min after the headache that she had been “unable to focus her vision clearly on the screen”.88 This study has laid ground for an unresolved debate on whether this single finding is demonstrating so-called silent aura hemodynamic findings due to CSD or if the results are due to atypical migraine aura or methodological pitfalls.89–91 Another group demonstrated in nine MO patients scanned within 24 h from headache debut and compared to the headache-free interval a small but significant decrease in global CBF (10%) and CBV (10%).92 Later, Denuelle et al.93 also showed a 10% bilateral posterior cortical hypoperfusion during spontaneous MO attacks.94 The study contrasts with the original study by Weiller et al.,12 who demonstrated in nine MO patients with unilateral attack patients no ictal changes in rCBF between the hemispheres ipsilateral and contralateral to the headache side. However, the study showed a 11% rCBF increase during the acute attack compared to the headache-free interval in median brain stem slightly contralateral to the headache side. The PET resolution could not identify activation at specific brainstem nuclei, but the activation was in an area which harbours the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) and the locus coeruleus (LC), which have been suggested to provide autonomic control of the cerebral and dural blood flow.95 Other PET studies have shown focal activation in the brainstem, hypothalamus, anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, cerebellum, thalamus, insula, prefrontal cortex, and temporal lobes.96,97 In conclusion, some PET studies have shown a small decrease in global and occipital lobe CBF during spontaneous attacks, but the studies are hampered by the lack of serial ictal measurements and new more precise studies are highly needed. There have been findings of focal activation in brain structures related to migraine, but whether the changes are specific to migraine has yet to be demonstrated.

Table 3.

Studies investigating vascular changes during spontaneous migraine attacks using PET.

| Authors | Method | Patients | Recordings | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weiller et al.12 | PET with C15O2 inhalation | 9 MO patients with only unilateral attacks of migraine | rCBF during spontaneous attacks (< 6 h from debut), after the relief of headache by 6 mg s.c. sumatriptan and during headache-free interval > 3 days after the headache | No differences in rCBF were found between the hemispheres ipsilateral and contralateral to the headache side. 11% rCBF increase during the acute attack compared to the headache-free interval in median brain stem Structures contralateral to the headache side |

| Bednarczyk et al.92 | PET with C15O2 inhalation | 9 MO patients | Spontaneous attacks (< 24 h from debut) and during headache-free interval > 48 h | Global CBF decreased 10% and CBV 5% during migraine attacks compared to the headachefree state |

| Afridi et al. 200597 | PET with C15O2 iv infusion | 3 MO and 2 MA patients | Spontaneous attacks (< 24 h from debut) and during headache-free interval > 72 h. Three right-sided and two left-sided attacks | Activation seen in the dorsal pons, lateralized to the left, right anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, cerebellum, thalamus, insula, prefrontal cortex, and temporal lobes. An area of deactivation, located in the pons, lateralized to the right |

| Denuelle et al.96 | PET with C15O2 iv infusion | 7 MO patients | Spontaneous attacks (< 4 h), after headache relief following 6 mg sumatriptan s.c. and during headache-free interval (15 to 60 days later). Three right-sided, three left-sided and one bilateral | Activations in the midbrain bilateral, pons and hypothalamus bilateral, all persisting after sumatriptan |

| Denuelle et al.93 | PET with C15O2 iv infusion | 7 MO patients | Spontaneous attacks (< 4 h), after headache relief following 6 mg sumatriptan s.c. and during headache-free interval (15 to 60 days later). Three right-sided, three left-sided and one bilateral | 10% bilateral posterior cortical hypoperfusion, which persisted (12%) after headache relief following sumatriptan injection |

| Woods et al.88 | PET and oxygen-15 labelled water | 1 apparent MO patient | 1 unexpected attack. 12 measurements at 15 min interval | Bilateral hypoperfusion in the occipital lobes at headache onset. rCBF decreased 40% and spread forward |

| Andersson et al.94 | PET and oxygen-15 labelled water | 3 MO and 8 MA patients | Wine induced attacks. Scans at aura phase, headache phase, after sumatriptan and later a baseline scan | Reduced flow (23%) and metabolism (23%) in the occipital lobe during head ache phase |

PET: positron emission tomography; MA: migraine with aura; MO: migraine without aura; MA: migraine with aura; rCBF: regional cerebral blood flow.

MRA in migraine

Although several headache and migraine studies have been conducted using this method, there is only a single study reporting data on spontaneous migraine attacks.11 In this study, the long-standing theory of extracranial vasodilation as the cause of the pulsating migraine pain was tested using a 3D-TOF-MRA scan during spontaneous attacks of unilateral migraineous pain in 19 patients suffering from migraine without aura.11 These patients were subsequently scanned 30 min after subcutaneous injection of 6 mg sumatriptan on the migraine attack day, and again on another migraine- and headache-free day. The circumference of several intra- and extracranial arterial segments was measured and compared between the three conditions.11 Data revealed a 13.0% dilation of the MCA, 11.5% dilation of the cerebral ICA and 11.4% dilation of the cavernous ICA on the pain-side during attack compared to outside of attack. A modest dilation was also reported on the non-pain side MCA (6.1%) and cavernous ICA (4.9%).11 However, the side-to-side comparison of these arteries showed 9.1–14.4% more dilation on the pain-side versus non-pain side during the attack day. No day-to-day or side-to-side differences of the extracranial arteries were demonstrated in the study.11 After effective treatment with sumatriptan, all extracranial arteries and the cavernous ICA were constricted by 10–20%, whereas the MCA and cerebral ICA remained dilated.11 These segments are thought to be protected by the blood–brain barrier, which may explain the lack of constrictor effect of sumatriptan. The cavernous ICA was the only arterial segment that was dilated during attack and constricted after sumatriptan. This part of ICA is in the bone and is covered by nerve plexus, which may be compressed by the surrounding bone when the artery dilates. May et al.98 reported dilation of the cavernous ICA after activation of the trigeminovascular system by ipsilateral injection of capsaicin in the forehead. Thus, the conclusion of this study was that migraine pain may be associated with intra- but not extracranial vasodilation.98 However, dilation of the MCA and ICA was not regarded as the cause of the pain, as effective treatment with sumatriptan did not reverse the dilation of these arteries. The strengths of this study are the investigation of spontaneous migraine attacks and the fact that the attacks were unilateral. Thus, the non-pain side can be used as control for the pain side. The limitation of the study was that only 19 patients were included, so that subgroup analyses were not possible. Examination of untreated spontaneous migraine attacks in a MRI scanner is a difficult task that requires an effective and demanding collaboration between many different departments. Although, no statistical significant extracranial dilation was found, data revealed that circumferences of all extracranial arteries were numerically greater on the pain side versus non-pain side. Thus, subtle circumference changes (less than 10%) cannot be rejected based on these findings. A small (5%) dilation of MMA on the pain side has previously been reported in a case-report of one patient.99 Subtle dilation of the MMA per se may not be painful as drug-induced 30% dilation of this artery has been reported in migraine without aura patients who had no pain.36 The ipsilateral lateralisation of small circumference changes could indicate perivascular inflammation causing slight relaxation of the vessel walls.

NIRS in migraine

NIRS has been used in migraine research to investigate cortical vasomotor reactivity during metabolic,100–102 physiological,103,104 pharmacological105,106 and functional tests.107,108 NIRS has also been used in one study investigating neurostimulation in CH.109

Using a breath hold (BH) test to investigate vasoreactivity as a result of changes in arterial CO2 concentration,110 Akin et al.100 showed that interictal HbR increase following BH was smaller in MO than in healthy controls, while HbO increase was similar in the two groups. In a different study, Liboni et al.101 showed smaller HbO increases and lower HbR decreases in 30 MO patients than in healthy controls during BH, which may have been biased by a shorter breath holding duration in MO patients than in healthy subjects. Another method of assessing vasomotor reactivity is via head-down maneuver inducing an increase in frontal lobe pressure, which usually leads to elevated CBF. This maneuver produced a significantly smaller increase in right-sided HbT in migraineurs when compared to volunteers.103 Migraine patients showed a smaller increase in right-sided HbT than in left-sided HbT following the head down maneuver. In addition, migraine patients had a greater increase in right-sided HbT than healthy volunteers in left-sided HbT.103 It is difficult to draw clear conclusions from this study as the patients were not coded as having MO or MA. The lateralized vasoreactivity is difficult to understand, but has been attributed to a sympathetic lateralization in the right hemisphere,111,112 even though it is not known if this may lead to asymmetric vasomotor responses. Vernieri et al.102 investigated side differences in MA patients in the interictal period, showing an increased cerebral vasoreactivity to CO2 inhalation measured by NIRS on the side of most frequent attacks. A recent study investigated 10 MA and 10 MO patients during the interictal period of migraine in comparison to healthy controls.113 The time-delay between the R-wave of an electrocardiogram and the arterial pulse wave of cerebral microcirculation, detected by NIRS on the frontal cortex of both sides, was used to evaluate the presence of cerebral arteriolar vasoconstriction. Both migraine groups had a significantly longer time delay than the control subjects, but there were no differences between sides. The same group measured the amplitude of the arterial pulse wave in patients with prolonged aura (1 h to 7 days) and found during aura a significant decrease of the arterial pulse wave and an increase of cerebral tissue oxygen saturation ipsilateral to the pain side and contralateral to aura symptoms compared with the headache-free periods.104 Overall, the studies on vasomotor reactivity are few and do not translate into one concept of altered vasomotor reactivity following metabolic or physiological changes in migraine patients.

NIRS has been used to investigate sumatriptan treatment investigated MO patients during attacks followed by subcutaneous sumatriptan or sham injections.105 After sumatriptan injection HbO decreased,105 which was correlated to changes in skin blood flow measured by laser Doppler flowmetry. Human studies have not shown that sumatriptan constricts extracerebral arteries more than cerebral arteries,11,30,114 and the decrease found by may therefore very likely be a systemic extracerebral effect. Thus, NIRS monitoring using scalp probes are probably not entirely brain specific, and the clinical value of this type of investigation, when systemic changes are expected, is questionable. Studies attempting to separate superficial and cerebral signals would be useful to further explore these types of pharmacological effects. In patients with familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM), Schytz et al.106 investigated the changes in low-frequency oscillations following glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), a nitric oxide donor. Interestingly, only FHM patients with common migraine subtypes had a lower increase in LFO amplitude compared to healthy controls and pure FHM patients, which suggests that the vascular differences between FHM patients and healthy controls were due to the common migraine subtypes.106

fNIRS studies have been performed in a few studies. Schytz et al.107 investigated frontal activation using a Stroop test interictally in 12 MO patients compared to 12 healthy controls and observed a clear vascular response in both groups, but no differences in amplitude or time response between groups, pointing to a normal neurovascular coupling in the frontal cortex. In contrast, Coutts et al.108 investigated hemodynamic response to a range of visual stimuli in 15 MA and 5 MO patients. There were no differences in the amplitude of the response between migraine and control groups, but migraine patients had a faster hemodynamic response to visual stimuli, which, however, normalized after applying active lenses that reduced distortions of text and improved comfort. The underlying mechanism for the time differences in hemodynamic response and their normalization is unknown and needs further investigation. Thus, there may be differences in neuronal, vascular or neurovascular coupling in migraine patients following stimuli, but so far this has only been shown in the occipital cortical vasculature interictally. NIRS may also be used to investigate responses to neurostimulation, which was shown in a small study with five CH patients with sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) stimulators, in which high frequency SPG stimulation induced a relative increase in HbO in the frontal region primarily on the stimulated ipsilateral side.109 In conclusion, NIRS has been used as a non-invasive tool to measure cortical changes following different types of experimental stimulation paradigms. So far, there are no studies investigating vascular changes during spontaneous attacks. The development of new portable NIRS devices,115 which can even be controlled by smartphones116 may result in the opportunity to investigate cortical changes during spontaneous attacks. It is possible that patients could apply the equipment during spontaneous attacks at home and measure continuously for hours. The challenges of NIRS recording during spontaneous attacks would be the lower spatial resolution and motion artifacts.

Studies of spontaneous attacks in trigeminal automatic cephalalgias

TCD in TACs

TCD studies in trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are very rare, most likely due to the nature of the disorders. Most patients are agitated during the attacks making it difficult to lie still for TCD measurements. Afra et al.117 reported decreased BFV in the MCA on the pain side during CH compared to an attack-free period. In an earlier study,118 bilateral decreased BFV in the MCA was found during CH attacks in patients. However, the attacks were induced by nitroglycerin and the decrease was most probably an effect of the drug119 rather than attack-related changes.

SPECT in TACS

There are relatively few SPECT studies investigating CBF during spontaneous CH or other TACs and to our knowledge none have been performed over the last 20 years (Table 4). The advantage of these headache types is their unilateral nature, which makes it possible to study hemispheric differences, whereas the challenges in performing imaging during attacks are the relative short attack duration (CH:15–180 min, paroxysmal hemicrania (PH): 2–30 min, short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT): 1–600 s) and the fact that TACs patients can be restless or agitated during attacks, resulting in movement artifacts. There are three studies investigating CBF changes during spontaneous attacks compared to the interictal state (Table 4). Sakai et al.25 showed a total CBF increase in three CH patients during attacks compared to the interictal phase and measured extracerebral blood flow, which increased most markedly on the pain side. Kobari et al.86 showed that rCBF increased 36–66% bilaterally during CH attacks in al cortical and subcortical regions except the occipital cortex. However, Nelson et al.120 showed ictally an 11–28% decrease in right or left hemisphere CBF in 3/4 CH patients, but a 15% increase in 1/4 CH patient, in which the decrease was greater in the dominant hemisphere irrespective of the side of the headache.120 There was no apparent correlation between CBF change and intensity of the pain.120 The same study also studied the CBF changes following nitroglycerin provocation and found three patients with an increase of 15 to 34%, while two had a 5 to 11% decrease. In comparison, Krabbe et al.121 performed the largest study so far of induced attacks with 133-Xenon inhalation high-resolution SPECT (200 regions) in eight CH patients and showed that during the headache phase, no significant changes of mean CBF from baseline occurred.121 The Nelson et al. and Sakai et al. studies used inhalation or intravenous injection of 133-Xenon with external stationary detection, which has a poor spatial resolution, and cannot clearly discriminate extra- from intracerebral blood flow changes. Thus, there is no strong support for changes in rCBF in cortical regions to play a large pathophysiological role in the development of CH attack. In SUNCT, one study has been performed using SPECT and Tc99m hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime (HMPAO) injected intravenously during a bout and between attacks lasting 30–60 s in one patient in which the radiocompound was injected 5 to 10 s after the start of an attack and showed normal tracer uptake and symmetric perfusion during headache periods.122

Table 4.

Studies investigating vascular changes during spontaneous TAC attacks using SPECT and PET.

| Authors | Method | Patients | Recordings | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poughias and Aasly122 | SPECT using Tc99m HMPAO i.v. | 1 SUNCT patient | During bout and three days without pain | Normal tracer uptake and no differences between sides |

| Sakai and Meyer25 | SPECT 133xenon inhalation | 3CH patients | During CH attacks and headache free intervals | A 45% increase in rCBF during attacks |

| Nelson et al.120 | SPECT 133xenon intravenous | 4 CH patients | During and after attacks | In 3/4 patients rCBF decreased (range 11 to 28%). 1 patient had an 15% increase in CBF during attack |

| Kobari et al.86 | SPECT 133xenon inhalation | 5 CH patients | During attacks (n = 2) and without headache (n = 3) | rCBF increased bilateral during attacks in al cortical and subcortical regions except the occipital cortex (range compared 36–66%) |

| Matharu et al.125 | H215O PET | 7 paroxysmal hemicrania patients | 4–6 scans in pain and off indomethacin. 3–5 scans pain-free and off indomethacin. Pain-free after indomethacin i.m. randomized | No differences in rCBF during headache compared with the pain-free state when off indomethacin. But, increased rCBF in the contralateral posterior hypothalamus and contralateral ventral midbrain when comparing to patients receiving indomethacin |

| Sprenger et al.123 | H215O PET | 1 chronic CH patient with stereotactic electrode implantation in left posterior hypothalamus two months earlier. | During an experimental study the stimulator was turned off and then the patient experienced a spontaneous attack. Three PET scans of 90 s each were obtained during this period and compared to the no pain-phase | The CH attack induced activation increases in the ipsilateral hypothalamus, medial thalamus, and contralateral perigenual ACC compared to no pain-phase |

SPECT: single photon emission computer tomography; PET: positron emission tomography; SUNCT: short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks; CH: cluster headache; rCBF: regional cerebral blood flow. ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; TAC: trigeminal automatic cephalalgia.

PET in TACs

Two PET studies exist in TACs patients during spontaneous attacks (Table 4). Sprenger et al.123 published a case report of a spontaneous CH attack in a CH patient who two months earlier had underwent stereotactic electrode implantation for deep brain stimulation of the left posterior hypothalamus.123 During a planned experimental study of brain activation, the stimulator was turned off, and the patient had a spontaneous attack in which three PET scans of 90 s each were obtained over 30 min and compared to the no-pain phase. The study found activation increases in the ipsilateral hypothalamus, medial thalamus and contralateral perigenual ACC, which are similar to activation found during nitroglycerin-induced CH attacks.124 In paroxysmal hemicranias, Matharu et al.125 showed no differences in rCBF during headache compared with the pain-free state when patients were off indomethacin, whereas an increased rCBF in the contralateral posterior hypothalamus and contralateral ventral midbrain was demonstrated when comparing to patients receiving indomethacin treatment. Thus, no pronounced cortical alterations are found in TAC patients interictally using PET.

Studies of spontaneous attacks in tension-type headache

Andersen et al.126 investigated rCBF in 41 chronic tension-type headache (TTH) patients during habitual headache using Xenon inhalation or Tc99m HMPAO i.v. SPECT and found normal regional and global CBF when comparing to 33 healthy controls.126 In 21 headache-free episodic TTH patients, increased blood flow velocities were measured in the anterior, middle and posterior cerebral, with no significant asymmetries of blood flow velocities in corresponding arteries.127 The same group did not observe increased BFV in 20 chronic TTH patients.128 Thus, there is no clear evidence of hemodynamic changes in TTH patients.

Conclusion and future directions

This review has gathered the available studies of vascular changes during spontaneous attacks in primary headaches. In migraine, aura symptoms clearly have a pattern of gradually spreading cortical hyperperfusion followed by gradual spreading hypoperfusion as shown by SPECT studies. There is not a pattern in migraine without aura of uniform vascular changes during attacks, but local changes may occur due to neuronal activation. MRA and TCD studies point to a small increase in cerebral vessel diameter during the headache phase, which may be the result of vasoactive peptides being released from perivascular nociceptors or parasympathetic nerve fibers. There is no proof that the vasodilation per se leads to pain. In TACs, there is no evidence of a uniform vascular change during attacks, but focal changes likely reflect neuronal activity in pain pathways. NIRS may be a new tool to further investigate cortical changes, especially during migraine with aura, which may elucidate underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. Moreover, the MR-based arterial spin labeling (ASL) sequence may also provide important information of the cortical blood flow changes in future studies. MRI images may be improved and patients may be scanned during attacks with motion correction.129 The MMA has been suspected as the source of pain in migraine using primarily animal models and from surgical experience. To date, no studies have investigated the intracranial segment of the MMA during spontaneous attacks, which would be extremely valuable in future studies.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Ray BS, Wolff HG. Experimental studies on headache. Arch Surg 1940; 41: 813–856. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff HG. Headache and other head pain, 2nd ed New York: Oxford University Press, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olesen J, Burstein R, Ashina M, et al. Origin of pain in migraine: evidence for peripheral sensitisation. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goadsby PJ. The vascular theory of migraine – a great story wrecked by the facts. Brain 2009; 132: 6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May A. Pearls and pitfalls: neuroimaging in headache. Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akerman S, Holland PR, Hoffmann J. Pearls and pitfalls in experimental in vivo models of migraine: dural trigeminovascular nociception. Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 577–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olesen J, Larsen B, Lauritzen M. Focal hyperemia followed by spreading oligemia and impaired activation of rCBF in classic migraine. Ann Neurol 1981; 9: 344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson JL, Muhr C, Lilja A, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism during migraine with and without aura. Cephalalgia 1997; 17: 570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadjikhani N, Sanchez del Rio M, Wu O, et al. Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98: 4687–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friberg L, Olesen J, Iversen HK, et al. Migraine pain associated with middle cerebral artery dilatation: reversal by sumatriptan. Lancet 1991; 338: 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiller C, May A, Limmroth V, et al. Brain stem activation in spontaneous human migraine attacks. Nat Med 1995; 1: 658–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.May A, Bahra A, Buchel C, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in spontaneous attacks of SUNCT: short-lasting neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing. Ann Neurol 1999; 46: 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H. Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg 1982; 57: 769–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinhard M, Wehrle-Wieland E, Grabiak D, et al. Oscillatory cerebral hemodynamics – the macro- vs. microvascular level. J Neurol Sci 2006; 250: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahl A, Russell D, Nyberg-Hansen R, et al. Effect of nitroglycerin on cerebral circulation measured by transcranial Doppler and SPECT. Stroke 1989; 20: 1733–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markwalder TM, Grolimund P, Seiler RW, et al. Dependency of blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery on end-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure – a transcranial ultrasound Doppler study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1984; 4: 368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schytz HW, Birk S, Wienecke T, et al. PACAP38 induces migraine-like attacks in patients with migraine without aura. Brain 2009; 132: 16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amin FM, Asghar MS, Guo S, et al. Headache and prolonged dilatation of the middle meningeal artery by PACAP38 in healthy volunteers. Cephalalgia 2012; 32: 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomsen LL, Iversen HK. Experimental and biological variation of three-dimensional transcranial Doppler measurements. J Appl Physiol 1993; 75: 2805–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blake P, Johnson B, VanMeter JW. Positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT): clinical applications. J Neuroophthalmol 2003; 23: 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirahata N, Henriksen L, Vorstrup S, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow assessed by 133Xe inhalation and emission tomography: normal values. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1985; 9: 861–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vorstrup S. Tomographic cerebral blood flow measurements in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease and evaluation of the vasodilatory capacity by the acetazolamide test. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 1988; 114: 1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carroll TJ, Teneggi V, Jobin M, et al. Absolute quantification of cerebral blood flow with magnetic resonance, reproducibility of the method, and comparison with H2(15)O positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2002; 22: 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakai F, Meyer JS. Regional cerebral hemodynamics during migraine and cluster headaches measured by the 133Xe inhalation method. Headache 1978; 18: 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watabe H, Itoh M, Mejia M, et al. Validation of noninvasive quantification of rCBF compared with dynamic/integral method by using positron emission tomography and oxygen-15 labeled water. Ann Nucl Med 1995; 9: 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phelps ME, Huang SC, Hoffman EJ, et al. Tomographic measurement of local cerebral glucose metabolic rate in humans with (F-18)2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: validation of method. Ann Neurol 1979; 6: 371–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hostetler ED, Joshi AD, Sanabria-Bohorquez S, et al. In vivo quantification of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor occupancy by telcagepant in rhesus monkey and human brain using the positron emission tomography tracer [11C]MK-4232. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2013; 347: 478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schankin CJ, Maniyar FH, Seo Y, et al. Ictal lack of binding to brain parenchyma suggests integrity of the blood-brain barrier for 11 C-dihydroergotamine during glyceryl trinitrate-induced migraine. Brain 2016; 139: 1994–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asghar MS, Hansen AE, Amin FM, et al. Evidence for a vascular factor in migraine. Ann Neurol 2011; 69: 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amin FM, Asghar MS, Ravneberg JW, et al. The effect of sumatriptan on cephalic arteries: a 3 T MR-angiography study in healthy volunteers. Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arngrim N, Schytz HW, Asghar MS, et al. Association of acetazolamide infusion with headache and cranial artery dilation in healthy volunteers. Pain 2014; 155: 1649–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arngrim N, Schytz HW, Britze J, et al. Migraine induced by hypoxia: an MRI spectroscopy and angiography study. Brain 2016; 139: 723–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoonman GG, van der Grond J, Kortmann C, et al. Migraine headache is not associated with cerebral or meningeal vasodilatation–a 3 T magnetic resonance angiography study. Brain 2008; 131: 2192–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis WL, Blatter DD, Harnsberger HR, et al. Intracranial MR angiography: comparison of single-volume three-dimensional time-of-flight and multiple overlapping thin slab acquisition techniques. Am J Roentgenol 1994; 163: 915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amin FM, Hougaard A, Schytz HW, et al. Investigation of the pathophysiological mechanisms of migraine attacks induced by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-38. Brain 2014; 137: 779–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amin FM, Lundholm E, Hougaard A, et al. Measurement precision and biological variation of cranial arteries using automated analysis of 3 T magnetic resonance angiography. J Headache Pain 2014; 15: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrari M, Quaresima V. A brief review on the history of human functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) development and fields of application. Neuroimage 2012; 63: 921–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boas DA, Elwell CE, Ferrari M, et al. Twenty years of functional near-infrared spectroscopy: introduction for the special issue. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jobsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science 1977; 198: 1264–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slater JP, Guarino T, Stack J, et al. Cerebral oxygen desaturation predicts cognitive decline and longer hospital stay after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2009; 87: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genbrugge C, Dens J, Meex I, et al. Regional cerebral oximetry during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: useful or useless? J Emerg Med 2016; 50: 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villringer A, Planck J, Hock C, et al. Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS): a new tool to study hemodynamic changes during activation of brain function in human adults. Neurosci Lett 1993; 154: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kato T, Kamei A, Takashima S, et al. Human visual cortical function during photic stimulation monitoring by means of near-infrared spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1993; 13: 516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoshi Y, Tamura M. Detection of dynamic changes in cerebral oxygenation coupled to neuronal function during mental work in man. Neurosci Lett 1993; 150: 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delpy DT, Cope M, van der Zee P, et al. Estimation of optical pathlength through tissue from direct time of flight measurement. Phys Med Biol 1988; 33: 1433–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okada E, Firbank M, Schweiger M, et al. Theoretical and experimental investigation of near-infrared light propagation in a model of the adult head. Appl Opt 1997; 36: 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scholkmann F, Kleiser S, Metz AJ, et al. A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 6–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox PT, Raichle ME. Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory stimulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986; 83: 1140–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q, Yan X, Strangman GE. Development of motion resistant instrumentation for ambulatory near-infrared spectroscopy. J Biomed Opt 2011; 16: 087008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atsumori H, Kiguchi M, Katura T, et al. Noninvasive imaging of prefrontal activation during attention-demanding tasks performed while walking using a wearable optical topography system. J Biomed Opt 2010; 15: 046002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piper SK, Krueger A, Koch SP, et al. A wearable multi-channel fNIRS system for brain imaging in freely moving subjects. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von LA, Wabnitz H, Sander T, et al. M3BA: a mobile, modular, multimodal biosignal acquisition architecture for miniaturized EEG-NIRS based hybrid BCI and monitoring. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2016, pp. 64(6): 1199–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chitnis D, Airantzis D, Highton D, et al. Towards a wearable near infrared spectroscopic probe for monitoring concentrations of multiple chromophores in biological tissue in vivo. Rev Sci Instrum 2016; 87: 065112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scholkmann F, Kleiser S, Metz AJ, et al. A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 6–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eggebrecht AT, Ferradal SL, Robichaux-Viehoever A, et al. Mapping distributed brain function and networks with diffuse optical tomography. Nat Photonics 2014; 8: 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian F, Liu H. Depth-compensated diffuse optical tomography enhanced by general linear model analysis and an anatomical atlas of human head. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 166–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferradal SL, Eggebrecht AT, Hassanpour M, et al. Atlas-based head modeling and spatial normalization for high-density diffuse optical tomography: in vivo validation against fMRI. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aasted CM, Yucel MA, Cooper RJ, et al. Anatomical guidance for functional near-infrared spectroscopy: atlasviewer tutorial. Neurophotonics 2015; 2: 020801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carp SA, Dai GP, Boas DA, et al. Validation of diffuse correlation spectroscopy measurements of rodent cerebral blood flow with simultaneous arterial spin labeling MRI; towards MRI-optical continuous cerebral metabolic monitoring. Biomed Opt Exp 2010; 1: 553–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saager RB, Berger AJ. Direct characterization and removal of interfering absorption trends in two-layer turbid media. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 2005; 22: 1874–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Q, Brown EN, Strangman GE. Adaptive filtering for global interference cancellation and real-time recovery of evoked brain activity: a Monte Carlo simulation study. J Biomed Opt 2007; 12: 044014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gagnon L, Yucel MA, Boas DA, et al. Further improvement in reducing superficial contamination in NIRS using double short separation measurements. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yucel MA, Selb J, Boas DA, et al. Reducing motion artifacts for long-term clinical NIRS monitoring using collodion-fixed prism-based optical fibers. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yucel MA, Selb J, Cooper RJ, et al. Targeted principle component analysis: a new motion artifact correction approach for near-infrared spectroscopy. J Innov Opt Health Sci 2014; 7(2): 1350066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Selb J, Yucel MA, Phillip D, et al. Effect of motion artifacts and their correction on near-infrared spectroscopy oscillation data: a study in healthy subjects and stroke patients. J Biomed Opt 2015; 20: 56011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scholkmann F, Metz AJ, Wolf M. Measuring tissue hemodynamics and oxygenation by continuous-wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy – how robust are the different calculation methods against movement artifacts? Physiol Meas 2014; 35: 717–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quaresima V, Bisconti S, Ferrari M. A brief review on the use of functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) for language imaging studies in human newborns and adults. Brain Lang 2012; 121: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vanderwert RE, Nelson CA. The use of near-infrared spectroscopy in the study of typical and atypical development. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ehlis AC, Schneider S, Dresler T, et al. Application of functional near-infrared spectroscopy in psychiatry. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 478–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Obrig H. NIRS in clinical neurology – a ‘promising’ tool? Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Obrig H, Neufang M, Wenzel R, et al. Spontaneous low frequency oscillations of cerebral hemodynamics and metabolism in human adults. Neuroimage 2000; 12: 623–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eggebrecht AT, Ferradal SL, Robichaux-Viehoever A, et al. Mapping distributed brain function and networks with diffuse optical tomography. Nat Photonics 2014; 8: 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.White BR, Snyder AZ, Cohen AL, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity in the human brain revealed with diffuse optical tomography. Neuroimage 2009; 47: 148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mesquita RC, Franceschini MA, Boas DA. Resting state functional connectivity of the whole head with near-infrared spectroscopy. Biomed Opt Exp 2010; 1: 324–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Homae F. A brain of two halves: insights into interhemispheric organization provided by near-infrared spectroscopy. Neuroimage 2014; 85(Pt 1): 354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kainerstorfer JM, Sassaroli A, Tgavalekos KT, et al. Cerebral autoregulation in the microvasculature measured with near-infrared spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 959–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shaystagul NA, Christensen CA, Amin FM, et al. Measurement of blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery during spontaneous migraine attacks: a systematic review. Headache 2017; 57: 852–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Olesen J, Lauritzen M, Tfelt-Hansen P, et al. Spreading cerebral oligemia in classical- and normal cerebral blood flow in common migraine. Headache 1982; 22: 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Andersen AR, Friberg L, Olsen TS, et al. Delayed hyperemia following hypoperfusion in classic migraine. Single photon emission computed tomographic demonstration. Arch Neurol 1988; 45: 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lauritzen M, Skyhoj OT, Lassen NA, et al. Changes in regional cerebral blood flow during the course of classic migraine attacks. Ann Neurol 1983; 13: 633–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lauritzen M, Olesen J. Regional cerebral blood flow during migraine attacks by Xenon-133 inhalation and emission tomography. Brain 1984; 107(Pt 2): 447–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Friberg L, Olsen TS, Roland PE, et al. Focal ischaemia caused by instability of cerebrovascular tone during attacks of hemiplegic migraine. A regional cerebral blood flow study. Brain 1987; 110(Pt 4): 917–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Olesen J, Tfelt-Hansen P, Henriksen L, et al. The common migraine attack may not be initiated by cerebral ischaemia. Lancet 1981; 2: 438–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferrari MD, Haan J, Blokland JA, et al. Cerebral blood flow during migraine attacks without aura and effect of sumatriptan. Arch Neurol 1995; 52: 135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kobari M, Meyer JS, Ichijo M, et al. Cortical and subcortical hyperperfusion during migraine and cluster headache measured by Xe CT-CBF. Neuroradiology 1990; 32: 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Coghill RC, Sang CN, Berman KF, et al. Global cerebral blood flow decreases during pain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998; 18: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Woods RP, Iacoboni M, Mazziotta JC. Brief report: bilateral spreading cerebral hypoperfusion during spontaneous migraine headache. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 1689–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Purdy RA. Migraine with and without aura share the same pathogenic mechanisms. Neurol Sci 2008; 29(Suppl 1): S44–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sanchez-Del-Rio M, Reuter U, Moskowitz MA. New insights into migraine pathophysiology. Curr Opin Neurol 2006; 19: 294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wolthausen J, Sternberg S, Gerloff C, et al. Are cortical spreading depression and headache in migraine causally linked? Cephalalgia 2009; 29: 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bednarczyk EM, Remler B, Weikart C, et al. Global cerebral blood flow, blood volume, and oxygen metabolism in patients with migraine headache. Neurology 1998; 50: 1736–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Denuelle M, Fabre N, Payoux P, et al. Posterior cerebral hypoperfusion in migraine without aura. Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 856–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Andersson JL, Muhr C, Lilja A, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism during migraine with and without aura. Cephalalgia 1997; 17: 570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lance JW. A concept of migraine and the search for the ideal headache drug. Headache 1990; 30: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Denuelle M, Fabre N, Payoux P, et al. Hypothalamic activation in spontaneous migraine attacks. Headache 2007; 47: 1418–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Afridi SK, Giffin NJ, Kaube H, et al. A positron emission tomographic study in spontaneous migraine. Arch Neurol 2005; 62: 1270–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.May A, Buchel C, Turner R, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography in facial and other pain: neurovascular mechanisms of trigeminal sensation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2001; 21: 1171–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nagata E, Moriguchi H, Takizawa S, et al. The middle meningial artery during a migraine attack: 3 T magnetic resonance angiography study. Intern Med 2009; 48: 2133–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akin A, Bilensoy D. Cerebrovascular reactivity to hypercapnia in migraine patients measured with near-infrared spectroscopy. Brain Res 2006; 1107: 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liboni W, Molinari F, Allais G, et al. Spectral changes of near-infrared spectroscopy signals in migraineurs with aura reveal an impaired carbon dioxide-regulatory mechanism. Neurol Sci 2009; 30(Suppl 1): S105–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vernieri F, Tibuzzi F, Pasqualetti P, et al. Increased cerebral vasomotor reactivity in migraine with aura: an autoregulation disorder? A transcranial Doppler and near-infrared spectroscopy study. Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shinoura N, Yamada R. Decreased vasoreactivity to right cerebral hemisphere pressure in migraine without aura: a near-infrared spectroscopy study. Clin Neurophysiol 2005; 116: 1280–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Viola S, Viola P, Litterio P, et al. Pathophysiology of migraine attack with prolonged aura revealed by transcranial Doppler and near infrared spectroscopy. Neurol Sci 2010; 31(Suppl 1): S165–S166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Watanabe Y, Tanaka H, Dan I, et al. Monitoring cortical hemodynamic changes after sumatriptan injection during migraine attack by near-infrared spectroscopy. Neurosci Res 2011; 69: 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schytz HW, Hansen JM, Phillip D, et al. Nitric oxide modulation of low-frequency oscillations in cortical vessels in FHM – a NIRS study. Headache 2012; 52: 1146–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schytz HW, Ciftci K, Akin A, et al. Intact neurovascular coupling during executive function in migraine without aura: interictal near-infrared spectroscopy study. Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Coutts LV, Cooper CE, Elwell CE, et al. Time course of the haemodynamic response to visual stimulation in migraine, measured using near-infrared spectroscopy. Cephalalgia 2012; 32: 621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schytz HW, Barlose M, Guo S, et al. Experimental activation of the sphenopalatine ganglion provokes cluster-like attacks in humans. Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Settakis G, Lengyel A, Molnar C, et al. Transcranial Doppler study of the cerebral hemodynamic changes during breath-holding and hyperventilation tests. J Neuroimaging 2002; 12: 252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hilz MJ, Dutsch M, Perrine K, et al. Hemispheric influence on autonomic modulation and baroreflex sensitivity. Ann Neurol 2001; 49: 575–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Avnon Y, Nitzan M, Sprecher E, et al. Autonomic asymmetry in migraine: augmented parasympathetic activation in left unilateral migraineurs. Brain 2004; 127: 2099–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Viola S, Viola P, Litterio P, et al. A new near-infrared spectroscopy parameter as marker for patients with migraine. Neurol Sci 2013; 34(Suppl 1): S129–S131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Amin FM, Asghar MS, Ravneberg JW, et al. The effect of sumatriptan on cephalic arteries: a 3 T MR-angiography study in healthy volunteers. Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jeppesen J, Beniczky S, Johansen P, et al. Exploring the capability of wireless near infrared spectroscopy as a portable seizure detection device for epilepsy patients. Seizure 2015; 26: 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Watanabe T, Sekine R, Mizuno T, et al. Development of portable, wireless and smartphone controllable near-infrared spectroscopy system. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016; 923: 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Afra J, Ertsey C, Jelencsik H, et al. SPECT and TCD studies in cluster headache patients. Funct Neurol 1995; 10: 259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dahl A, Russell D, Nyberg-Hansen R, et al. Cluster headache: transcranial Doppler ultrasound and rCBF studies. Cephalalgia 1990; 10: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Iversen HK, Holm S, Friberg L, et al. Intracranial hemodynamics during intravenous infusion of glyceryl trinitrate. J Headache Pain 2008; 9: 177–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Nelson RF, du Boulay GH, Marshall J, et al. Cerebral blood flow studies in patients with cluster headache. Headache 1980; 20: 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Krabbe AA, Henriksen L, Olesen J. Tomographic determination of cerebral blood flow during attacks of cluster headache. Cephalalgia 1984; 4: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Poughias L, Aasly J. SUNCT syndrome: cerebral SPECT images during attacks. Headache 1995; 35: 143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sprenger T, Boecker H, Tolle TR, et al. Specific hypothalamic activation during a spontaneous cluster headache attack. Neurology 2004; 62: 516–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.May A, Bahra A, Buchel C, et al. Hypothalamic activation in cluster headache attacks. Lancet 1998; 352: 275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Matharu MS, Cohen AS, Frackowiak RS, et al. Posterior hypothalamic activation in paroxysmal hemicrania. Ann Neurol 2006; 59: 535–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Andersen AR, Langemark M, Olesen J. Regional cerebral blood flow in chronic tension-type headache. Migraine and other headaches: The vascular mechanisms, New York: Raven, 1991, pp. 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wallasch TM. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonic features in episodic tension-type headache. Cephalalgia 1992; 12: 293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wallasch TM. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonic features in chronic tension-type headache. Cephalalgia 1992; 12: 385–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Andersson JLR, Graham MS, Drobnjak I, et al. Towards a comprehensive framework for movement and distortion correction of diffusion MR images: within volume movement. Neuroimage 2017; 152: 450–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]