Abstract

Background:

Individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUDs) who smoke cigarettes experience greater health risks than those using either substance alone. Further, disparities exist in AUDs and smoking by race/ethnicity. Although smoking has declined in the general population, it is not known whether the smoking prevalence has changed over time for individuals with AUDs. The current study used representative U.S. data to estimate the prevalence of current cigarette use from 2002 to 2016 by AUD status and severity overall and by race/ethnicity.

Methods:

Data were drawn from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, an annual cross-sectional study of U.S. individuals, from 2002 to 2016 (total analytic sample n = 837,326). Cigarette smoking prevalence was calculated annually among those with and without past-year AUD and by AUD severity level (mild, moderate, severe AUD). Time trends in smoking prevalence by AUD status and severity were tested using logistic regression for the overall sample and significant interactions were subsequently stratified by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic [NH] White, NH Black, Hispanic, NH Other).

Results:

Cigarette use was persistently over twice as common among those with AUDs compared to without AUDs (2016: 37.84% vs. 16.29%). Cigarette use was also more common among those at each level of AUD severity criteria (2016: mild AUD 34.59%; moderate AUD 35.35%; severe AUD 52.23%). Approximately half of NH Black respondents with AUDs, and three-quarters of NH Black respondents with severe AUDs, reported smoking in 2016. The prevalence of smoking decreased significantly over time among respondents with and without AUDs; however, there were differences by race. There was no decline in smoking prevalence among NH Black respondents with AUDs over time in contrast to a significant decrease for every other racial/ethnic group with and without AUDs.

Conclusions:

Individuals with AUDs may need additional resources and interventions to quit smoking, especially NH Black individuals.

Keywords: Smoking, Cigarettes, Alcohol Use Disorders, Race, Epidemiology

ALCOHOL USE AND cigarette use are strongly associated (Adams, 2017; McKee and Weinberger, 2013) and cigarette smoking is common among a majority of adults with problematic alcohol use such as alcohol use disorders (AUDs; Weinberger et al., 2016). Approximately 14% of U.S. adults report past-year AUDs with 7.3% of adults reporting mild AUDs, 3.2% reporting moderate AUDs, and 3.4% reporting severe AUDs (Grant et al., 2015). The risks associated with alcohol misuse are well established (Tetrault and O’Connor, 2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016) and people with AUDs experience increased alcohol-related diseases and premature mortality (Rogers et al., 2015; Stahre et al., 2014). Further, greater disability is associated with greater severity of AUD (Grant et al., 2015).

The significant health risks of tobacco, the leading cause of preventable death and disease in the United States and a significant global cause of mortality, are also clear (USDHHS, 2014; WHO, 2012). Co-use of alcohol and tobacco increases the risk of several diseases (e.g., head and neck cancers, cirrhosis) well beyond use of either substance alone (Marrero et al., 2005; Pelucchi et al., 2006; Zheng, 2010). Use of cigarettes also has detrimental effects on aspects of cognition (e.g., executive function, memory; Durazzo et al., 2012; Wagner et al., 2013) and is associated with decreased cognitive recovery in adults with AUDs (Durazzo et al., 2006, 2014; Pennington et al., 2013). Importantly, cigarette smoking is associated with greater odds of relapse to AUDs among individuals with remitted AUDs (Weinberger et al., 2015). Consequently, reducing the prevalence of smoking among individuals with AUDs could have numerous important benefits for the health and treatment/recovery of individuals with AUDs.

The prevalence of smoking in the United States and many other industrialized countries has declined over the past 50 years (GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators, 2017; Jamal et al., 2016, Ng et al., 2014). Yet, there are some groups for whom tobacco control efforts may not have been as effective, such as individuals with AUDs. Understanding the extent to which cigarette use remains disproportionately prevalent among those with AUDs, and whether there have been recent changes in the prevalence of smoking, is of critical import in estimating the need for public health and clinical efforts to be directed toward people with AUDs.

Beyond examining the relationship between AUD and smoking in the general population, there are racial/ethnic disparities related both to AUDs and cigarette smoking in the United States. While AUDs are similarly or more prevalent among non-Hispanic (NH) White individuals than NH Black and Hispanic individuals, NH Black and Hispanic individuals have more persistent AUDs, greater likelihood of recurrent AUDs, and greater AUD-related negative consequences (Caetano et al., 2014; Chartier and Caetano, 2010; Vaeth et al., 2017; Witbrodt et al., 2014). Further, NH Black and Hispanic individuals with severe AUDs are less likely to use AUD treatment services and complete AUD treatment than NH White individuals (Chartier and Caetano, 2010). It should also be noted that in large samples of U.S. veterans, the prevalence of AUDs was higher among NH Black and Hispanic respondents than NH White respondents (Williams et al., 2016) while treatment utilization for AUDs did not differ by race/ethnicity (Bensley et al., 2017). Like AUDs, NH Black and Hispanic individuals report a lower prevalence of smoking, while NH Black individuals reported a similar prevalence of smoking compared to NH White individuals (Jamal et al., 2018). The leading causes of mortality among NH Black and Hispanic individuals, similar to NH White individuals, are smoking-related diseases (CDC, 2018a,b; USDHHS, 1998), yet these 2 racial/ethnic groups experience disproportionate tobacco-related medical consequences (DeLancey et al., 2008; Underwood et al., 2012, USDHHS, 1998) Identifying differences in the trends in smoking prevalence over time for those with, versus without, AUDs by race/ethnicity would further allow the targeting of public health and clinical efforts toward subgroups with the greatest AUD and smoking disparities.

The current study used annual, cross-sectional data of individuals age 12 and older in the United States to estimate the overall prevalence of current cigarette use from 2002 to 2016 among those with and without AUDs, adjusting for demographics. It was expected that persons with AUDs would report higher prevalence of smoking than persons without AUDs. As more severe AUDs are associated with increased odds of nicotine use disorder (Grant et al., 2015), the prevalence of smoking was also examined by severity of AUD to examine whether the prevalence of smoking increased with greater AUD severity. The current study also assessed racial/ethnic differences in smoking prevalence and AUD severity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Study data were drawn from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) public data portal (http://datafiles.samhsa.gov/) for the years 2002 to 2016. The NSDUH provides annual cross-sectional national data on the use of tobacco, other substance use, and mental health in the United States and is described in depth elsewhere (SAMHSA, 2016). A multistage area probability sample for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia has been conducted to represent the male and female civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population aged 12 and older. The data sets from each year were concatenated, adding a variable for the survey year. For this study, respondents in each year from 2002 to 2016 who reported current cigarette smoking status were included in the analyses of smoking prevalence (unweighted total n = 837,326).

Measures

Cigarette Smoking Prevalence.

Current (i.e., past-month) cigarette smoking prevalence was assessed using the following questions: (i) “Have you ever smoked part or all of a cigarette?” (ii) “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and (iii) “During the past 30 days, have you smoked part or all of a cigarette?” Current smokers were defined as respondents who reported smoking at least 100 lifetime cigarettes and at least 1 cigarette within the past 30 days. For the analyses, an “other smoking categories” group was defined as respondents who were not current smokers (e.g., never smokers, former smokers).

Alcohol Use Variables.

Past-year AUDs (alcohol dependence or alcohol abuse) were assessed using DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994) during each annual survey. Alcohol abuse was defined as meeting 1 or more of 4 alcohol abuse criteria in the past 12 months and not meeting criteria for alcohol dependence in the past 12 months. Alcohol dependence was defined as meeting 3 or more of 7 alcohol dependence criteria. Respondents who met criteria for past-year alcohol abuse or dependence were classified as having a past-year AUD. Among respondents who were categorized as having a past-year AUD, AUD severity levels were classified as mild, moderate, or severe (1 to 3, 4 to 5, or ≥6 criteria, respectively) consistent with the approach taken by Grant and colleagues (2015). Detailed AUD criteria can be found in the NSDUH 2016 Codebook (Appendix D Recoded Substance Dependence and Abuse Variable Documentation section; SAMHSA, 2016).

Demographics.

Demographic variables were classified into the following categories: age, gender, race/ethnicity, and total annual family income.

Statistical Analysis

To estimate cigarette smoking prevalence from 2002 to 2016 by AUD status, the prevalence of current smoking and associated standard errors among the whole population and stratified by past-year AUD status (AUD, no AUD) was calculated for each year from 2002 to 2016. Time trends in the prevalence of current smoking stratified by past-year AUD status were tested using logistic regression with continuous year as the predictor for the linear time trend. These analyses were conducted twice: first with no covariates (unadjusted) and subsequently adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and total annual family income. To determine whether there were differential time trends in current smoking by AUD status, additional logistic regression analyses were run that included the 2-way interaction of year by past-year AUD versus their respective comparison group (i.e., no past-year AUD). These analyses were repeated examining AUD severity categories (mild, moderate, severe AUD vs. no AUD).

The time trend analyses described above were repeated stratified by race/ethnicity. A logistic regression of current smoking found the 3-way interactions of year by AUD status by race/ethnicity was significant so the models examining race/ethnicity were stratified by past-year AUD status. Time trends in the prevalence of current smoking by past-year AUD status group within each racial/ethnic category were tested using logistic regression with continuous year as the predictor to test the linear time trend. These analyses were conducted twice: once with no covariates (unadjusted model) and once controlling for other demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, total annual family income; adjusted model). Differential time trends in current smoking between past-year AUD status were tested by 2-way interaction of year × past-year AUD status (with past-year AUD vs. without past-year AUD status) in logistic regressions stratified by each racial/ethnic group. When analyses were repeated using the AUD severity variable, the 3-way interaction was not significant (p = 0.093) so models were not run stratifying by race/ethnicity.

Sampling weights for the NSDUH were computed to control unit-level and individual-level nonresponse and were adjusted to ensure consistency with population estimates obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. In order to use data from the 15 years of combined data, a new weight was created upon aggregating the 15 data sets by dividing the original weight by the number of data sets combined. This approach is outlined in the NSDUH Public Use File Codebook (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2017) and is consistent with our prior work (e.g., Weinberger et al., 2018). Additional details regarding the weight components and the sample weighting procedures appear in the 2016 NSDUH Methodological Resource Book (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2017). Analyses were performed incorporating the NSDUH sampling weights and controlling for the complex clustered sampling using STATA SE version 13 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX) and SAS-callable SUDAAN Version 11.0.1 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC; http://www.rti.org/sudaan/), which used the Taylor series estimation methods to provide accurate standard errors.

RESULTS

Cigarette Smoking Prevalence from 2002 to 2016 for Those With and Without AUDs

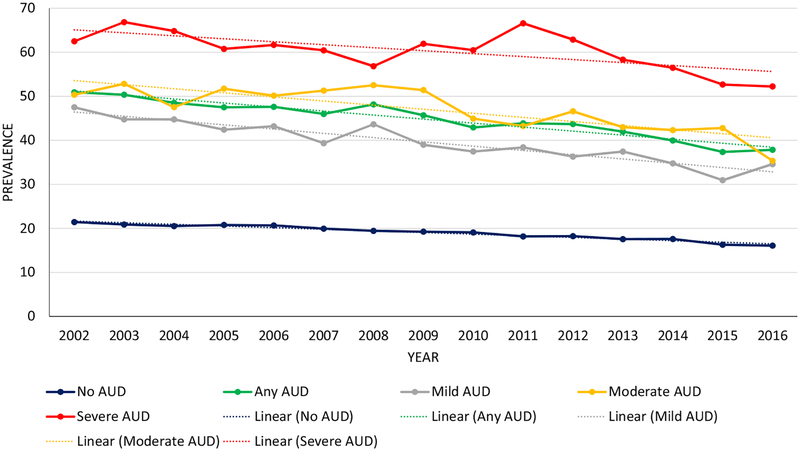

The prevalence of cigarette smoking declined significantly from 2002 to 2016 among respondents with AUDs (51.92 to 37.84%, p < 0.001) and among respondents without AUDs (21.44 to 16.07%, p < 0.001; see Table 1 and Fig. 1). These trends remained significant after controlling for demographic covariates. The year × AUD interaction was significant in unadjusted and adjusted analyses such that the decline in smoking prevalence from 2002 to 2016 was more rapid among respondents with AUDs than among respondents without AUDs. Yet, the cigarette smoking prevalence among respondents with AUDs was more than twice that of respondents without AUDs for every year in the study period including the most recent data year (2016).

Table 1.

Cigarette Smoking Prevalence from 2002 to 2016 by AUD Status and Severity (NSDUH, Age 12 and Older)

| Linear trends | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past-year AUD status | Total | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ORa (95% CI) |

t-Test p-value |

aORa,b (95% CI) |

t-Test p-value |

| No AUD (n) | 133,188 | 9,702 | 9,966 | 9,591 | 9,459 | 9,216 | 9,131 | 8,829 | 8,731 | 8,832 | 8,922 | 8,315 | 8,014 | 8,384 | 8,285 | 7,811 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.98) | −20.30 <0.001 | 0.98 (0.98, 0.99) | −13.12 <0.001 |

| wt% | 18.98 | 21.44 | 20.88 | 20.53 | 20.77 | 20.67 | 19.94 | 19.43 | 19.25 | 19.09 | 18.18 | 18.23 | 17.56 | 17.59 | 16.29 | 16.07 | ||||

| SE | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.30 | ||||

| Any AUD (n) | 35,050 | 2,969 | 2,929 | 2,923 | 2,887 | 1,686 | 2,691 | 2,589 | 2,556 | 2,344 | 2,169 | 2,018 | 1,855 | 1,593 | 1,482 | 1,359 | 0.96 (0.96, 0.97) | −13.45 <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | −9.87 <0.001 |

| wt% | 45.02 | 50.92 | 50.36 | 48.52 | 47.50 | 47.60 | 45.99 | 48.16 | 45.69 | 42.92 | 43.87 | 43.68 | 41.97 | 39.96 | 37.35 | 37.84 | ||||

| SE | 0.31 | 1.32 | 1.16 | 1.09 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.29 | 1.08 | 1.24 | 1.53 | 1.28 | 1.15 | 1.28 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.21 | ||||

| Mild AUD (n) | 18,747 | 1,641 | 1,601 | 1,604 | 1,574 | 1,437 | 1,425 | 1,373 | 1,330 | 1,273 | 1,180 | 1,035 | 1,000 | 822 | 771 | 681 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | −10.19 <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.97) | −7.86 <0.001 |

| wt% | 39.83 | 47.51 | 44.75 | 44.75 | 42.42 | 43.20 | 39.34 | 43.64 | 38.98 | 37.46 | 38.40 | 36.30 | 37.44 | 34.76 | 30.93 | 34.59 | ||||

| SE | 0.45 | 1.51 | 1.46 | 1.58 | 1.63 | 1.37 | 1.49 | 1.75 | 1.63 | 1.70 | 1.33 | 1.44 | 1.82 | 1.34 | 1.48 | 1.79 | ||||

| Moderate AUD (n) | 9,041 | 735 | 784 | 761 | 752 | 702 | 688 | 675 | 663 | 574 | 549 | 537 | 470 | 418 | 378 | 355 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | −6.39 <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | −4.87 <0.001 |

| wt% | 47.22 | 50.35 | 52.83 | 47.54 | 51.74 | 50.15 | 51.29 | 52.52 | 51.41 | 44.94 | 43.25 | 46.59 | 42.98 | 42.32 | 42.79 | 35.35 | ||||

| SE | 0.65 | 2.48 | 2.17 | 2.24 | 2.25 | 2.08 | 2.35 | 2.76 | 2.39 | 3.14 | 2.71 | 2.35 | 2.40 | 2.33 | 2.60 | 2.42 | ||||

| Severe AUD (n) | 7,262 | 593 | 544 | 558 | 561 | 547 | 578 | 541 | 563 | 497 | 440 | 446 | 385 | 353 | 333 | 323 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | −3.87 <0.001 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | −2.66 0.009 |

| wt% | 60.47 | 62.49 | 66.85 | 64.82 | 60.76 | 61.66 | 60.44 | 56.83 | 61.92 | 60.47 | 66.58 | 62.88 | 58.31 | 56.47 | 52.68 | 52.23 | ||||

| SE | 0.78 | 2.65 | 3.29 | 2.87 | 2.96 | 2.75 | 2.96 | 3.63 | 2.23 | 2.91 | 3.00 | 2.95 | 3.35 | 2.97 | 2.60 | 2.42 | ||||

| Chi-square tests (p-value)c | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Chi-square tests (p-value)d | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year AUD status (none vs. any) | F(1,170) = 17.77 | <0.001 | F(1,170) = 23.87 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year AUD severity status (none; mild; moderate; severe) | F(3,168) = 6.98 | <0.001 | F(3,168) = 8.99 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year no AUD versus mild AUD | F(1,170) = 16.19 | <0.001 | F(1,170) = 18.84 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year no AUD versus moderate AUD | F(1,170) = 4.54 | 0.035 | F(1,170) = 8.62 | 0.004 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year no AUD versus severe AUD | F(1,170) = 0.14 | 0.713 | F(1,170) = 0.40 | 0.530 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year mild AUD versus moderate AUD | F(1,170) = 0.29 | 0.592 | F(1,170) = 0.18 | 0.671 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year mild AUD versus severe AUD | F(1,170) = 3.07 | 0.082 | F(1,170) = 3.35 | 0.069 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year × past-year moderate AUD versus severe AUD | F(1,170) = 1.03 | 0.311 | F(1,170) = 1.44 | 0.233 | ||||||||||||||||

AUD, alcohol use disorder; NSDUH, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

OR compares current smoking versus other smoker categories (i.e., former smokers, never smokers); ORs reflect the linear time trends across all years.

Adjusted for age (12 to 17, 18 to 25, 26 to 34, 35 to 49, and 50 years old or older); gender (male, female); total annual family income (<$20,000, $20,000 to $49,999, $50,000 or more); and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic all other race or more than one race).

Chi-squared tests for the difference in percentage of current smokers by past-year AUD status (none vs. any AUD).

Chi-squared tests for the difference in percentage of current smokers by past-year AUD severity status (none; mild; moderate; severe).

Fig. 1.

Cigarette smoking prevalence from 2002 to 2016 for those with and without alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and by AUD severity (mild, moderate, and severe).

When examining severity of AUDs, the prevalence of cigarette smoking declined significantly from 2002 to 2016 among respondents with mild (47.51 to 30.93%, p < 0.001), moderate (50.35 to 35.35%, p < 0.001), and severe (62.49 to 52.23%, p < 0.001) AUD, as well as among respondents without AUDs (21.44 to 16.07%, p < 0.001; see Fig. 1 and Table 1). These trends remained significant after controlling for demographic covariates. The year × AUD severity interactions were significant in unadjusted and adjusted analyses such that the decline in smoking prevalence from 2002 to 2016 was more rapid among respondents with mild and moderate AUDs than among respondents without AUDs. The rate of decline in smoking prevalence did not differ significantly between other levels of AUD severity (no AUD vs. severe AUD, mild AUD vs. moderate AUD, mild AUD vs. severe AUD, or moderate AUD vs. severe AUD). Notably, the prevalence of cigarette smoking among respondents within each severity level of AUD was higher than those without AUD in every year of the study period. In 2016, the cigarette smoking prevalence among those with mild and moderate AUDs was 2 times higher than those with no AUD and the cigarette smoking prevalence among those with severe AUD was more than 3 times higher than those with no AUD.

Cigarette Smoking Prevalence from 2002 to 2016 by AUD Status and Race/Ethnicity

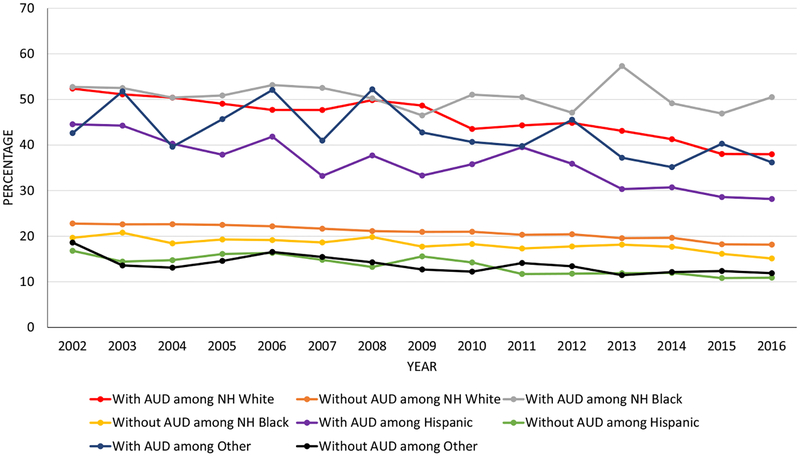

The 3-way interaction of time × AUD status (AUD, no AUD) × race/ethnicity was significant in unadjusted analyses, F(3, 168) = 2.84, p = 0.040, and after adjusting for demographics, F(3, 168) = 4.49, p = 0.005; see Fig. 2. In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, there was a significant decrease in cigarette smoking prevalence over time for respondents with any AUD and without AUDs in each racial/ethnic group except for NH Black respondents with AUDs. NH Black respondents with AUDs showed no change in smoking prevalence over time and half of Black respondents with AUDs (50.51%) reported smoking cigarettes in 2016. Among NH White respondents, the decrease in smoking prevalence over time was greater for respondents with AUDs compared to respondents without AUDs; trends over time did not differ by AUD status for the other racial/ethnic groups. The 3-way interaction of time × AUD severity (no, mild, moderate, severe AUD) × race/ethnicity was not significant.

Fig. 2.

Cigarette smoking prevalence from 2002 to 2016 by alcohol use disorder status and race/ethnicity. Note: AUD, alcohol use disorder; NH, non-Hispanic.

The prevalence of cigarette smoking was significantly higher among respondents with mild, moderate, and severe AUDs compared to respondents without AUDs within each racial/ethnic group for every year of the study period (see Table 2). In 2016, compared to NH White respondents without AUDs, NH White respondents with mild and moderate AUDs were approximately 2 times more likely, and persons with severe AUD were approximately 2.5 times more likely to report cigarette smoking (p < 0.001) Among NH Black participants in 2016, compared to those without AUDs, persons with mild and moderate AUDs were approximately 2.5 times more likely and those with severe AUD were approximately 5 times more likely to report smoking (p < 0.001). Among Hispanic participants in 2016, persons with mild and moderate AUDs were approximately 2.5 times more likely and those with severe AUD were approximately 3 times more likely to report cigarette smoking as compared to Hispanic participants without AUDs. Among individuals of other race/ethnicity in 2016, persons with mild and moderate AUDs were approximately 2.5 times more likely and those with severe AUD were approximately 4 times more likely than other participants without AUD to report cigarette smoking (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Cigarette Smoking Prevalence From 2002 to 2016 by AUD Status and Race/Ethnicity (NSDUH, Age 12 and Older)

| Linear trends | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past-year AUD status | Total | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ORa (95% CI) |

t-Test p-value |

aORa,b (95% CI) |

t-Test p-value |

| No AUD NH White (n) | 95,208 | 7,488 | 7,427 | 7,123 | 6,776 | 6,624 | 6,777 | 6,250 | 6,182 | 6,307 | 6,300 | 5,884 | 5,588 | 5,771 | 5,595 | 5,316 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.98) | −14.14 <0.001 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | −9.12 <0.001 |

| wt% | 20.89 | 22.78 | 22.59 | 22.62 | 22.47 | 22.17 | 21.64 | 21.13 | 20.93 | 20.97 | 20.31 | 20.42 | 19.56 | 19.64 | 18.22 | 18.15 | ||||

| SE | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.39 | ||||

| NH Black (n) | 13,549 | 855 | 923 | 871 | 953 | 896 | 889 | 935 | 859 | 927 | 945 | 878 | 873 | 930 | 947 | 868 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | −5.33 <0.001 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | −5.35 <0.001 |

| wt% | 18.19 | 19.65 | 20.77 | 18.43 | 19.28 | 19.14 | 18.62 | 19.82 | 17.71 | 18.27 | 17.30 | 17.75 | 18.15 | 17.68 | 16.13 | 15.11 | ||||

| SE | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.56 | ||||

| Hispanic (n) | 13,781 | 820 | 969 | 918 | 1,055 | 973 | 928 | 905 | 972 | 880 | 887 | 883 | 865 | 907 | 940 | 879 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.97) | −10.36 <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | −9.03 <0.001 |

| wt% | 13.43 | 16.79 | 14.42 | 14.74 | 16.10 | 16.32 | 14.80 | 13.25 | 15.57 | 14.24 | 11.71 | 11.78 | 11.87 | 11.93 | 10.82 | 10.90 | ||||

| SE | 0.20 | 1.08 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.52 | ||||

| NH Other (n) | 10,650 | 539 | 647 | 679 | 675 | 723 | 737 | 739 | 718 | 718 | 790 | 670 | 688 | 776 | 803 | 748 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | −4.86 <0.001 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | −4.08 <0.001 |

| wt% | 13.61 | 18.60 | 13.58 | 13.09 | 14.57 | 16.54 | 15.44 | 14.27 | 12.70 | 12.22 | 14.11 | 13.41 | 11.45 | 12.14 | 12.36 | 11.88 | ||||

| SE | 0.27 | 1.70 | 1.29 | 0.86 | 1.15 | 1.22 | 1.31 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 0.88 | 1.16 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.98 | 0.98 | ||||

| Chi-square test between race/ethnicity (p-value)c | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × race/ethnicity among no AUD | F(3, 168) = 5.61 | 0.001 | F(3, 168) = 3.82 | 0.011 | ||||||||||||||||

| Any AUD NH White (n) | 24,663 | 2,297 | 2,168 | 2,163 | 2,066 | 1,901 | 1,960 | 1,793 | 1,774 | 1,603 | 1,502 | 1,351 | 1,219 | 1,036 | 951 | 879 | 0.96 (0.96, 0.97) | −11.14 <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | −8.58 <0.001 |

| wt% | 46.34 | 52.38 | 51.12 | 50.40 | 49.06 | 47.71 | 47.69 | 49.85 | 48.66 | 43.53 | 44.32 | 44.85 | 43.11 | 41.27 | 38.03 | 37.98 | ||||

| SE | 0.38 | 1.64 | 1.24 | 1.34 | 1.23 | 1.37 | 1.47 | 1.29 | 1.55 | 1.71 | 1.42 | 1.54 | 1.37 | 1.24 | 1.34 | 1.47 | ||||

| NH Black (n) | 3,029 | 203 | 206 | 220 | 245 | 215 | 202 | 232 | 225 | 212 | 180 | 200 | 184 | 171 | 155 | 179 | 0.99 (0.97,1.01) | −0.81 0.418 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | −0.30 0.766 |

| wt% | 50.71 | 52.74 | 52.51 | 50.40 | 50.87 | 53.16 | 52.53 | 50.23 | 46.49 | 51.05 | 50.49 | 47.10 | 57.32 | 49.16 | 46.91 | 50.51 | ||||

| SE | 0.88 | 3.79 | 4.94 | 3.70 | 3.97 | 3.22 | 3.63 | 3.58 | 3.60 | 4.36 | 3.87 | 3.24 | 3.24 | 3.59 | 3.70 | 2.98 | ||||

| Hispanic (n) | 4,218 | 299 | 334 | 313 | 341 | 333 | 283 | 338 | 299 | 302 | 288 | 260 | 251 | 214 | 201 | 162 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | −5.82 <0.001 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | −4.99 <0.001 |

| wt% | 36.01 | 44.55 | 44.26 | 40.29 | 37.88 | 41.84 | 33.21 | 37.71 | 33.30 | 35.79 | 39.51 | 35.89 | 30.33 | 30.71 | 28.58 | 28.16 | ||||

| SE | 0.72 | 2.65 | 3.21 | 2.83 | 3.01 | 4.11 | 2.68 | 3.55 | 2.54 | 3.34 | 3.21 | 2.17 | 2.96 | 2.43 | 2.88 | 2.96 | ||||

| NH Other (n) | 3,140 | 170 | 221 | 227 | 235 | 237 | 246 | 226 | 258 | 227 | 199 | 207 | 201 | 172 | 175 | 139 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | −2.70 0.008 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | −2.66 0.009 |

| wt% | 42.58 | 42.62 | 51.77 | 39.61 | 45.68 | 52.09 | 40.97 | 52.22 | 42.76 | 40.67 | 39.77 | 45.55 | 37.21 | 35.15 | 40.29 | 36.18 | ||||

| SE | 1.20 | 5.15 | 4.39 | 5.64 | 5.72 | 5.17 | 4.29 | 4.98 | 4.05 | 4.17 | 5.06 | 5.97 | 4.78 | 3.97 | 3.90 | 3.81 | ||||

| Chi-square test between race/ethnicity (p-value)c | <0.001 | 0.050 | 0.268 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.153 | <0.001 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.124 | 0.035 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × race/ethnicity among any AUD | F(3, 1,680) = 4.28 | 0.006 | F(3, 168) = 4.26 | 0.006 | ||||||||||||||||

| Mild AUD NH White (n) | 13,587 | 1,308 | 1,218 | 1,222 | 1,143 | 1,054 | 1,078 | 975 | 964 | 896 | 849 | 724 | 668 | 543 | 494 | 461 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | −9.05 <0.001 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | −7.34 <0.001 |

| wt% | 41.07 | 49.98 | 45.12 | 47.26 | 43.39 | 43.72 | 40.74 | 44.44 | 42.39 | 37.85 | 38.22 | 37.81 | 38.20 | 35.52 | 30.61 | 34.88 | ||||

| SE | 0.54 | 1.79 | 1.58 | 1.93 | 1.82 | 1.77 | 1.80 | 2.17 | 2.03 | 1.99 | 1.68 | 1.82 | 2.46 | 1.63 | 1.97 | 2.19 | ||||

| NH Black (n) | 1,531 | 96 | 108 | 110 | 140 | 99 | 98 | 129 | 105 | 105 | 92 | 95 | 94 | 84 | 90 | 86 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 0.44 0.664 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.81 0.420 |

| wt% | 44.44 | 43.55 | 44.77 | 42.05 | 46.52 | 47.00 | 41.81 | 46.97 | 34.58 | 47.07 | 46.40 | 36.89 | 55.48 | 47.00 | 45.29 | 42.47 | ||||

| SE | 1.27 | 5.64 | 5.73 | 4.78 | 5.67 | 5.30 | 4.51 | 5.35 | 5.23 | 4.73 | 4.93 | 4.51 | 4.93 | 5.11 | 4.09 | 3.37 | ||||

| Hispanic (n) | 2,094 | 151 | 165 | 155 | 168 | 167 | 127 | 166 | 141 | 159 | 152 | 121 | 136 | 114 | 96 | 76 | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) | −4.27 <0.001 | 0.95 (0.93, 0.98) | −3.90 <0.001 |

| wt% | 30.97 | 40.38 | 39.46 | 35.80 | 31.34 | 27.21 | 35.25 | 27.55 | 31.47 | 34.89 | 27.42 | 25.41 | 26.80 | 26.80 | 21.61 | 26.74 | ||||

| SE | 0.92 | 3.86 | 5.04 | 4.11 | 3.84 | 4.92 | 3.43 | 3.70 | 3.72 | 4.50 | 4.04 | 3.34 | 3.82 | 3.62 | 2.40 | 4.09 | ||||

| NH Other (n) | 1,525 | 86 | 110 | 117 | 123 | 117 | 122 | 103 | 120 | 113 | 87 | 95 | 102 | 81 | 91 | 58 | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | −2.29 0.023 | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | −2.25 0.026 |

| wt% | 39.97 | 36.01 | 51.32 | 33.15 | 49.49 | 44.45 | 44.40 | 49.89 | 34.60 | 34.12 | 36.03 | 39.52 | 34.70 | 28.16 | 35.08 | 34.63 | ||||

| SE | 1.57 | 6.41 | 5.70 | 6.86 | 6.04 | 8.18 | 5.71 | 6.80 | 4.89 | 5.78 | 6.66 | 8.74 | 7.05 | 4.49 | 5.38 | 5.71 | ||||

| Chi-square test between race/ethnicity (p-value)c | <0.001 | 0.050 | 0.490 | 0.031 | 0.037 | 0.546 | 0.008 | 0.147 | 0.007 | 0.122 | 0.305 | 0.163 | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.047 | ||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × race/ethnicity among mild AUD | F(3, 168) = 5.79 | <0.001 | F(3, 168) = 6.16 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Moderate AUD NH White (n) | 6,251 | 558 | 576 | 560 | 546 | 478 | 479 | 464 | 436 | 387 | 352 | 343 | 314 | 268 | 263 | 227 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | −5.22 <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | −3.87 <0.001 |

| wt% | 48.69 | 51.00 | 54.00 | 49.93 | 54.21 | 47.89 | 52.68 | 56.70 | 53.73 | 46.30 | 44.39 | 47.52 | 44.99 | 44.12 | 42.73 | 37.11 | ||||

| SE | 0.71 | 2.96 | 2.26 | 2.32 | 2.76 | 2.43 | 2.83 | 2.73 | 2.78 | 3.92 | 3.53 | 3.14 | 3.16 | 2.66 | 3.31 | 3.20 | ||||

| NH Black (n) | 788 | 51 | 50 | 53 | 50 | 69 | 56 | 52 | 70 | 60 | 58 | 62 | 39 | 49 | 31 | 38 | 0.97 (0.94,1.01) | −1.41 0.162 | 0.98 (0.94,1.01) | −1.28 0.203 |

| wt% | 51.15 | 56.36 | 53.55 | 39.56 | 53.93 | 60.86 | 57.46 | 44.52 | 62.15 | 45.71 | 52.11 | 58.21 | 47.05 | 40.31 | 46.08 | 40.46 | ||||

| SE | 2.05 | 8.09 | 9.10 | 7.66 | 8.33 | 7.51 | 6.74 | 5.95 | 7.11 | 8.26 | 6.13 | 7.04 | 7.72 | 6.40 | 8.31 | 8.07 | ||||

| Hispanic (n) | 1,143 | 80 | 98 | 86 | 95 | 87 | 85 | 84 | 79 | 76 | 78 | 79 | 63 | 54 | 46 | 53 | 0.96 | −2.33 | 0.96 | −2.11 |

| (0.93, 0.99) | 0.021 | (0.93, 0.99) | 0.037 | |||||||||||||||||

| wt% | 39.71 | 41.72 | 47.76 | 40.92 | 46.78 | 47.60 | 45.15 | 39.45 | 33.86 | 41.91 | 39.36 | 37.96 | 34.28 | 35.54 | 37.22 | 28.96 | ||||

| SE | 1.79 | 6.27 | 6.09 | 6.05 | 5.41 | 6.76 | 6.12 | 7.41 | 5.45 | 7.79 | 6.52 | 5.65 | 7.36 | 4.71 | 7.79 | 5.18 | ||||

| NH Other (n) | 859 | 46 | 60 | 62 | 61 | 68 | 68 | 75 | 78 | 51 | 61 | 53 | 54 | 47 | 38 | 37 | 0.97 (0.93,1.00) | −1.80 0.073 | 0.96 (0.92,1.00) | −1.91 0.057 |

| wt% | 43.84 | 50.08 | 53.49 | 52.44 | 35.14 | 64.84 | 33.47 | 54.33 | 52.01 | 34.09 | 33.13 | 41.35 | 38.77 | 46.79 | 55.76 | 30.35 | ||||

| SE | 2.29 | 7.75 | 7.40 | 9.23 | 9.05 | 6.08 | 8.03 | 11.22 | 9.22 | 8.49 | 8.08 | 10.45 | 9.71 | 6.98 | 7.61 | 6.42 | ||||

| Chi-square test between race/ethnicity (p-value)c | <0.001 | 0.414 | 0.741 | 0.246 | 0.195 | 0.157 | 0.129 | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.741 | 0.355 | 0.193 | 0.482 | 0.390 | 0.501 | 0.436 | ||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × race/ethnicity among moderate AUD | F(3, 168) = 0.08 | 0.970 | F(3, 168) = 0.10 | 0.958 | ||||||||||||||||

| Severe AUD NH White (n) | 4,815 | 431 | 374 | 381 | 377 | 369 | 403 | 354 | 374 | 320 | 301 | 284 | 237 | 225 | 194 | 191 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | −3.22 0.002 | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | −2.34 0.020 |

| wt% | 63.34 | 62.66 | 70.81 | 64.95 | 65.34 | 66.75 | 65.35 | 58.67 | 64.97 | 62.26 | 68.84 | 65.22 | 60.32 | 60.64 | 60.51 | 50.50 | ||||

| SE | 0.99 | 3.19 | 3.32 | 3.67 | 3.63 | 3.08 | 3.23 | 4.05 | 2.92 | 3.70 | 3.60 | 3.84 | 4.04 | 3.75 | 3.60 | 3.15 | ||||

| NH Black (n) | 710 | 56 | 48 | 57 | 55 | 47 | 48 | 51 | 50 | 47 | 30 | 43 | 51 | 38 | 34 | 55 | 0.99 (0.95,1.03) | −0.35 0.727 | 1.00 (0.95,1.94) | −0.13 0.897 |

| Wt% | 68.14 | 66.99 | 68.51 | 91.47 | 59.89 | 61.07 | 73.72 | 66.87 | 59.71 | 68.94 | 66.14 | 62.78 | 72.91 | 67.39 | 54.32 | 75.46 | ||||

| SE | 1.84 | 5.72 | 10.67 | 3.55 | 8.10 | 7.15 | 7.12 | 7.54 | 8.96 | 9.73 | 9.54 | 7.62 | 6.92 | 7.52 | 8.87 | 6.46 | ||||

| Hispanic (n) | 981 | 68 | 71 | 72 | 78 | 79 | 71 | 88 | 79 | 67 | 58 | 60 | 52 | 46 | 59 | 33 | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | −2.02 0.045 | 0.97 (0.93,1.01) | −1.61 0.110 |

| wt% | 46.36 | 58.46 | 53.29 | 53.18 | 44.58 | 47.00 | 37.00 | 42.19 | 51.50 | 42.21 | 56.92 | 53.67 | 45.76 | 39.75 | 37.29 | 31.65 | ||||

| SE | 2.00 | 7.61 | 8.76 | 7.52 | 7.60 | 9.49 | 6.79 | 8.90 | 7.02 | 6.60 | 6.40 | 7.63 | 8.80 | 5.57 | 5.93 | 7.41 | ||||

| NH Other (n) | 756 | 38 | 51 | 48 | 51 | 52 | 56 | 48 | 60 | 63 | 51 | 59 | 45 | 44 | 46 | 44 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | −0.81 0.421 | 0.97 (0.92,1.01) | −1.43 0.156 |

| wt% | 52.45 | 58.95 | 51.65 | 45.43 | 54.68 | 59.13 | 41.51 | 60.58 | 57.56 | 70.86 | 67.73 | 66.34 | 42.62 | 39.82 | 39.04 | 49.32 | ||||

| SE | 2.90 | 10.49 | 11.29 | 12.44 | 8.59 | 9.02 | 7.16 | 7.78 | 11.52 | 8.18 | 10.45 | 8.01 | 12.60 | 9.82 | 9.09 | 9.78 | ||||

| Chi-square test between race/ethnicity (p-value)c | <0.001 | 0.756 | 0.175 | 0.002 | 0.048 | 0.084 | <0.001 | 0.090 | 0.330 | 0.056 | 0.399 | 0.410 | 0.076 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.002 | F(3, 168) = 0.43 | 0.735 | F(3, 168) = 0.47 | 0.701 |

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × race/ethnicity among severe AUD | F(3, 168) = 6.98 | <0.001 | F(3, 168) = 9.69 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD status (in 2 categories; none vs. any) among NH White participants | F(1, 170) = 23.38 | <0.001 | F(1, 170) = 30.80 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD status (in 2 categories; none vs. any) among NH Black participants | F(1, 170) = 1.28 | 0.259 | F(1, 170) = 2.60 | 0.109 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD status (in 2 categories; none vs. any) among Hispanic participants | F(1, 170) = 1.55 | 0.215 | F(1, 170) = 1.90 | 0.170 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD status (in 2 categories; none vs. any) among NH Other race/ethnicity participants | F(1, 170) = 0.13 | 0.722 | F(1, 170) = 0.94 | 0.334 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD severity status (in 4 categories) among NH White participants | F(3, 168) = 9.07 | <0.001 | F(3, 168) = 11.27 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD severity status (in 4 categories) among NH Black participants | F(3, 168) = 1.48 | 0.221 | F(3, 168) = 1.69 | 0.171 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD severity status (in 4 categories) among Hispanic participants | F(3, 168) = 0.50 | 0.680 | F(3, 168) = 0.76 | 0.520 | ||||||||||||||||

| Differential time trend: year as continuous × past-year AUD severity status (in 4 categories) among NH Other race/ethnicity participants | F(3, 168) = 0.17 | 0.915 | F(3, 168) = 0.65 | 0.582 | ||||||||||||||||

AUD, alcohol use disorder; NH, non-Hispanic; NSDUH, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; wt%, weighted percent.

OR compares current smoking versus other smoker categories (i.e., former smokers, never smokers); ORs reflect the linear time trends across all years.

Adjusted for age (12 to 17, 18 to 25, 26 to 34, 35 to 49, and 50 years old or older); gender (male, female); total annual family income (<$20,000, $20,000 to $49,999, ≥$50,000); and race/ethnicity (NH White, NH Black, Hispanic, NH all other race or more than one race).

Chi-squared tests for the difference in percentage of current smokers by race/ethnicity.

DISCUSSION

We examined trends in cigarette smoking prevalence over a 15-year period among individuals in the United States by AUD status and severity in the full sample and by race/ethnicity. The prevalence of smoking decreased over time among individuals with and without AUDs. Yet, the prevalence of smoking among individuals with AUDs was more than twice as high as those without AUDs in every year of the study period, including the most recent data year (2016:37.84% vs. 16.07%). When considering AUD severity, the discrepancy was even greater with more than half of persons with severe AUDs (52.23%) reporting cigarette smoking in 2016. Regarding racial/ethnic differences in AUDs and smoking, there was no change in smoking prevalence among NH Black individuals with AUDs over time while every other racial/ethnic group experienced declines in smoking. In 2016, approximately half (50.51%) of people with AUDs who identified as NH Black reported smoking cigarettes. Notably, three-quarters (75.46%) of NH Black persons with severe AUDs reported smoking in 2016. There was a decrease in cigarette smoking among both individuals with and without AUDs and a more rapid decrease in smoking among individuals with AUDs, specifically mild and moderate AUDs, compared to individuals without AUDs during the time period studied. The speed of the decline in smoking prevalence did not differ significantly between individuals with severe AUDs and those without AUDs or between those in various pairs of AUD severity levels (e.g., mild vs. moderate, severe vs. moderate). However, smoking remains significantly more common among individuals with AUDs, including those with mild, moderate, and severe AUDs, suggesting that those with AUDs of any severity level remain a highly vulnerable group disproportionately affected by cigarette use.

Alcohol and cigarettes are commonly used together and smoking quit rates are lower for individuals with AUD compared to those without AUD (Falk et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2014; Weinberger et al., 2016, 2017). There are several potential pharmacological, genetic, and environmental reasons for these high levels of co-use and maintenance of smoking among people with AUDs (Adams, 2017; McKee and Weinberger, 2013; Roche et al., 2016). For example, alcohol increases craving for nicotine and nicotine self-administration (Dermody and Hendershot, 2017; Verplaetse and McKee, 2017). Treatment programs for AUDs may present an important opportunity to aid these individuals with smoking cessation efforts. Although there may be concerns about providing smoking treatment concurrent with alcohol treatment, most studies find that concurrent smoking and alcohol treatment do not yield worse outcomes than treating alcohol alone (for recent reviews, see McKelvey et al., 2017; Thurgood et al., 2016). As cigarette use increases craving to use alcohol (Cooney et al., 2007; Dermody and Hendershot, 2017; Verplaetse and McKee, 2017), is related to decreased cognitive recovery in adults with AUDs (Durazzo et al., 2006, 2014; Pennington et al., 2013), and is associated with poorer AUD outcomes (Durazzo and Meyerhoff, 2017; Weinberger et al., 2015), combined smoking and alcohol treatment may offer significant benefits for alcohol treatment outcomes.

We identified racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between AUDs and smoking. One out of every 2 NH Black individuals with AUDs reported smoking in 2016, the highest prevalence among any racial/ethnic group. Further, approximately 75% of NH Black individuals with severe AUDs reported cigarette smoking. Individuals who identified as NH Black and had AUDs also did not show any change in smoking prevalence over time in contrast to a decrease in smoking for NH Black individuals without AUDs and every other racial/ethnic group across AUD status. These findings contrast with 1 study that did not find racial/ethnic differences in the cross-sectional relationship between AUD and smoking using 2011 to 2013 NSDUH data (Higgins et al., 2016).

A better understanding is needed of the disparities in smoking among NH Black persons with AUDs compared to persons with AUDs from other racial/ethnic groups (see Zemore et al., 2018). Factors proposed to impact racial/ethnic differences in AUDs include discrimination and prejudice, racial/ethnic stigma, poverty, neighborhood factors (e.g., ethnic density), and treatment access and utilization (Mulia et al., 2009; Vaeth et al., 2017; Zemore et al., 2016). NH Black persons are less likely than NH White persons access alcohol treatment services, especially at higher level of AUD severity (Chartier and Caetano, 2010), and the percentage of NH Black persons admitted for alcohol treatment decreased from 2002 to 2012 while the percentage of NH White and Hispanic persons increased during that time period (Vaeth et al., 2017).

In addition to understanding disparities in AUDs for NH Black persons, there is also a need for more information about racial/ethnic differences in smoking behavior (e.g., Cox et al., 2011). Although NH Black individuals in the general U.S. population have a similar smoking prevalence to NH White individuals (Jamal et al., 2018) and are more likely to report a desire to quit and quit attempts (Babb et al., 2017), NH Black individuals appear to be less likely to quit smoking (Babb et al., 2017). Several of the factors suggested to play a role in racial/ethnic disparities in AUD are also related to greater prevalences of cigarette smoking (e.g., discrimination, poverty; Borrell et al., 2007; Brandolo et al., 2015; Casetta et al., 2017; Lorant et al., 2003). In addition, NH Black individuals are more likely to use menthol cigarettes, which are associated with greater nicotine dependence and greater difficulty quitting (Delnevo et al., 2011; Foulds et al., 2010; Gandhi et al., 2009; Levy et al., 2011; Okuyemi et al., 2007; Villanti et al., 2017). Little is known about menthol smoking among persons with AUDs overall or by race/ethnicity. Among patients at 24 substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs in the United States, which included AUD treatment, the prevalence of menthol smoking of 53.3% and, within the sample of menthol users, 23.8% reported that alcohol was their primary substance (compared to 15.7% of nonmenthol smokers; Gubner et al., 2018). Menthol cigarette use, compared to nonmenthol cigarette use, was associated with NH Black and Hispanic race/ethnicity, female gender, and greater interest in quitting smoking during SUD treatment. Two U.S. studies reported that menthol use was not associated with past 30-day alcohol use (Rath et al., 2016; Villanti et al., 2018) while another U.S. study of smokers from the community found no relationship between menthol use and binge drinking, frequency of consuming alcohol, or number of drinks per drinking occasion (Cohn et al., 2017). It is not clear at this time whether menthol plays a role in the disparities of smoking among persons with and without AUD.

Together, more research is needed to understand the factors associated with AUD disparities and smoking behavior among NH Black persons as well as how these factors might interact with each other and impact smoking behavior among persons with AUDs. NH Black individuals with AUDs, especially those with severe AUDs, who smoke cigarettes may need additional targeted public health and clinical interventions, including attention to variables that may associated with smoking and AUDs among this group (e.g., stress, treatment access) and variables that may disproportionally impact quit success for NH Black persons such as menthol cigarettes. Attention to these variables may be critical to make progress in decreasing the smoking prevalence and consequences of smoking for persons with both cigarette smoking and AUDs.

There are several limitations of the current study. First, results would need to be replicated to determine generalizability to individuals who were not included in the NSDUH sample (e.g., non-U.S. adults). Second, the 15 years of data used in the current analyses were cross-sectional. It would be useful for studies with longitudinal data that can follow adults with and without AUDs over time to examine individual trajectories in AUD, cigarette smoking, and the relationship between the 2 behaviors over time as well as potential mediators and moderators of the relationship between AUD and cigarette smoking prevalence. Third, due to small sample sizes, races/ethnicities other than NH White, NH Black, and Hispanic were analyzed together as a single group. This group included races/ethnicities with both the highest (e.g., Native American) and lowest (e.g., Asian) AUD and smoking prevalences (Chartier and Caetano, 2010; Jamal et al., 2018). Similarly, subgroups within race/ethnicity (e.g., Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans as subgroups of the Hispanic group) demonstrate differences in AUD prevalence (Vaeth et al., 2017), but could not be examined separately due to sample size restrictions. It was also outside the scope of the current investigation to examine differences in the relationship between AUD and smoking prevalence for other demographics (e.g., gender, education) or demographic differences within racial/ethnic groups (e.g., gender differences in the relationship between AUD and smoking prevalence for NH Black respondents). These are important areas for future research. Fourth, smoking and AUDs were assessed using self-report measures, which may be subject to recall biases, reporting errors, and underreporting of substance use or problems related to substance use. Fifth, while outside the scope of the current study, it will be important for future research to examine factors associated with and/or underlying the relationship between AUD and smoking especially for NH Black individuals.

CONCLUSIONS

Individuals with AUDs bear a disproportionate burden of cigarette smoking in the United States, with a prevalence that is over twice the national average, with even higher prevalences seen among those with more severe AUDs. Cigarette smoking has not declined among NH Black individuals with AUDs, whereas a decline is observed among all other racial/ethnic groups. Approximately half of NH Black individuals with AUD, and three-quarters of NH Black individuals with severe AUDs, reported smoking in 2016. Because of the increased health risks associated with the smoking among persons with AUDs (Marrero et al., 2005; Pelucchi et al., 2006; Zheng, 2010), there is a need to focus greater scientific and public health efforts on tobacco control efforts for this subgroup. Individuals with AUDs may need additional resources and interventions to help reduce the high prevalence of smoking especially for those who identify as NH Black.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIDA (grants R01-DA20892 to RDG and K01-DA043413 to LRP).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- Adams S (2017) Psychopharmacology of tobacco and alcohol comorbidity: a review of current evidence. Curr Addict Rep 4:25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edAmerican Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A (2017) Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensley KM, Harris AH, Gupta S, Rubinsky AD, Jones-Webb R, Glass JE, Williams EC (2017) Racial/ethnic differences in initiation of and engagement with addictions treatment among patients with alcohol use disorders in the veterans health administration. J Subst Abuse Treat 73:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell L, Jacobs D, Williams D, Pletcher M, Houston T, Kiefe C (2007) Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the coronary artery risk development in adults study. Am J Epidemiol 166:1068–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandolo E, Monge A, Agosta J, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Standon C, Schwartz J (2015) Perceived ethnic discrimination and cigarette smoking: examining the moderating effects of race/ethnicity and gender in a sample of Black and Latino urban adults. J Behav Med 38:689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Vaeth PA, Chartier KG, Mills BA (2014) Epidemiology of drinking, alcohol use disorders, and related problems in US ethnic minority groups. Handb Clin Neurol 125:629–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casetta B, Videla AJ, Bardach A, Morello P, Soto N, Lee K, Camacho PA, Hermoza Moquillaza RV, Ciapponi A (2017) Association between cigarette smoking prevalence and income level: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 19:1401–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2018a) African Americans and tobacco use. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/african-americans/index.htm. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- CDC (2018b) Hispanics/Latinos and tobacco use. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/hispanics-latinos/index.htm. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2017) 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Public Use File Codebook. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, Caetano R (2010) Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health 33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn A, Johnson A, Pearson J, Rose S, Ehlke S, Ganz O, Niaura R (2017) Determining non-cigarette tobacco, alcohol, and substance use typologies across menthol and non-menthol smokers using latent class analysis. Tob Induc Dis 15:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney NL, Litt MD, Cooney JL, Pilkey DT, Steinberg HR, Oncken CA (2007) Alcohol and tobacco cessation in alcohol-dependent smokers: analysis of real-time reports. Psychol Addict Behav 21:277–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Okuyemi K, Choi WS, Ahluwalia JS (2011) A review of tobacco use treatments in U.S. ethnic minority populations. Am J Health Promot 25: S11–S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLancey JO, Thun MJ, Jemal A, Ward EM (2008) Recent trends in Black-White disparities in cancer mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:2908–2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delnevo CD, Gundersen DA, Hrywna M, Echeverria SE, Steinberg MB (2011) Smoking-cessation prevalence among U.S. smokers of menthol versus non-menthol cigarettes. Am J Prev Med 41:357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Hendershot CS (2017) A critical review of the effects of nicotine and alcohol co-administration in human laboratory studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:473–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ (2017) Psychiatric, demographic, and brain morphological predictors of relapse after treatment for an alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ, Nixon SJ (2012) A comprehensive assessment of neurocognition in middle-aged chronic cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 122:105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Pennington DL, Schmidt TP, Meyerhoff DJ (2014) Effects of cigarette smoking history on neurocognitive recovery over 8 months of abstinence in alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:2816–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Rothlind JC, Gazdzinski S, Banys P, Meyerhoff DJ (2006) A comparison of neurocognitive function in nonsmoking and chronically smoking short-term abstinent alcoholics. Alcohol 39:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhofel S (2006) An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health 29:162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Hooper MW, Pletcher MJ, Okuyemi KS (2010) Do smokers of menthol cigarettes find it harder to quit smoking? Nicotine Tob Res 12 (Suppl 2):S102–S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi KK, Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Lu SE, Williams JM (2009) Lower quit rates among African American and Latino menthol cigarette smokers at a tobacco treatment clinic. Int J Clin Pract 63:360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators (2017) Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 389:1885–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou P, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS (2015) Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72:757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubner NR, Williams DD, Pagano A, Campbell BK, Guydish J (2018) Menthol cigarette smoking among individuals in treatment for substance use disorders. Addict Behav 80:135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Kurti AN, Redner R, White TJ, Keith DR, Gaalema DE, Sprague BL, Stanton CA, Roberts ME, Doogan NJ, Priest JS (2016) Co-occurring risk factors for current cigarette smoking in a U.S. nationally representative sample. Prev Med 92:110–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, Graffunder CM (2016) Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:1205–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, Homa DM, Babb SD, King BA, Neff LJ (2018) Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67:53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Gonzalez ME, Ling PM, Glantz SA (2015) Relationship of smoke-free laws and alcohol use with light and intermittent smoking and quit attempts among US adults and alcohol users. PLoS One 10:e0137023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Blackman K, Tauras J, Chaloupka FJ, Villanti AC, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB (2011) Quit attempts and quit rates among menthol and nonmenthol smokers in the United States. Am J Public Health 101:1241–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M (2003) Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 157:98–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Fu S, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS (2005) Alcohol, tobacco and obesity are synergistic risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 42:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Weinberger AH (2013) How can our knowledge of alcohol-tobacco interactions inform treatment for alcohol use? Annu Rev Clin Psychol 9:649–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey K, Thrul J, Ramo D (2017) Impact of quitting smoking and smoking cessation treatment on substance use outcomes: an updated and narrative review. Addict Behav 65:161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE (2009) Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33:654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, Robinson M, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Thomson B, Wollum A, Sanman E, Wulf S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Gakidou E (2014) Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980–2012. JAMA 311:183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Faseru B, Sanderson Cox L, Bronars CA, Ahluwalia JS (2007) Relationship between menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among African American light smokers. Addiction 102:1979–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelucchi C, Gallus S, Garavello W, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C (2006) Cancer risk associated with alcohol and tobacco use: focus on upper aero-digestive tract and liver. Alcohol Res Health 29:193–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington DL, Durazzo TC, Schmidt TP, Mon A, Abe C, Meyerhoff DJ (2013) The effects of chronic cigarette smoking on cognitive recovery during early abstinence from alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:1220–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath JM, Villanti AC, Williams VF, Richardson A, Pearson JL, Vallone DM (2016) Correlates of current menthol cigarette and flavored other tobacco product use among U.S. young adults. Addict Behav 62:35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche DJO, Ray LA, Yardley MM, King AC (2016) Current insights into the mechanisms and development of treatments for heavy-drinking cigarette smokers. Curr Addict Rep 3:125–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RG, Boardman JD, Pendergast PM, Lawrence EM (2015) Drinking problems and mortality risk in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend 151:38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (2016) National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015. Code-book. SAMHSA, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA (2014) Smoking and mental illness in the US population. Tob Control 23:e147–e153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X (2014) Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis 11:E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetrault JM, O’Connor PG (2017) Risky Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Course, Assessment, and Diagnosis (Saitz R ed). UpToDate Inc., Waltham, MA: Available at: http://www.uptodate.com. Accessed December 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thurgood SL, McNeill A, Clark-Carter D, Brose LS (2016) A systematic review of smoking cessation interventions for adults in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Nicotine Tob Res 18:993–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Tai E, Davis SP, Stewart SL, White A, Momin B, Fairley TL (2012) Racial and regional disparities in lung cancer incidence. Cancer 118:1910–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016) Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS (1998) Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups-African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS (2014) The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth PA, Wang-Schweig M, Caetano R (2017) Drinking, alcohol use disorder, and treatment access and utilization among U.S. Racial/Ethnic groups. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:6–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse TL, McKee SA (2017) An overview of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in the human laboratory. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 43:186–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS, Gagosian SY, Abrams DB (2017) Menthol cigarettes and the public health standard: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 17:983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti AC, Gaalema DE, Tidey JW, Kurti AN, Sigmon SC, Higgins ST (2018) Co-occurring vulnerabilities and menthol use in U.S. young adult cigarette smokers: findings from Wave 1 of the PATH Study, 2013–2014. Prev Med 117:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Schulze-Rauschenbach S, Petrovsky N, Brinkmeyer J, von der Goltz C, Grunder G, Spreckelmeyer KN, Wienker T, Diaz-Lacava A, Mobascher A, Dahmen N, Clepce M, Thuerauf N, Kiefer F, de Millas JW, Gallinat J, Winterer G (2013) Neurocognitive impairments in non-deprived smokers–results from a population-based multi-center study on smoking-related behavior. Addict Biol 18:752–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Funk AP, Goodwin RD (2016) A review of epidemiologic research on smoking behavior among persons with alcohol and illicit substance use disorders. Prev Med 92:148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Goodwin RD (2017) Cigarette smoking quit rates among adults with and without alcohol use disorders and heavy alcohol use, 2002–2015: a representative sample of the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend 180:204–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Wall MM, Hasin DS, Zvolensky MJ, Goodwin RD (2018) Cigarette use is increasing among people with illicit substance use disorders in the United States, 2002–14: emerging disparities in vulnerable populations. Addiction 113:719–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Platt J, Jiang B, Goodwin RD (2015) Cigarette smoking and risk of alcohol use relapse among adults in recovery from alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:1989–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2012) WHO Global Report: Mortality Attributable to Tobacco. WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Gupta S, Rubinsky AD, Jones-Webb R, Bensley KM, Young JP, Hagedorn H, Gifford E, Harris AH (2016) Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of clinically recognized alcohol use disorders among patients from the U.S. Veterans Health Administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, Kerr WC (2014) Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol-related problems: differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:1662–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Mulia N, Kerr WC, Ehlers CL, Cook WK, Martinez P, Lui C, Greenfield TK (2018) The future of research on alcohol-related disparities across U.S. racial/ethnic groups: a plan of attack. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 79:7–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Ye Y, Martinez P, Jones-Webb R, Karriker-Jaffe K (2016) Poor, persecuted, young, and alone: toward explaining the elevated risk of alcohol problems among Black and Latino men who drink. Drug Alcohol Depend 163:31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng T (2010) Tobacco use and risk of oral cancer, in Tobacco: Science, Policy and Public Health, 2nd ed (Boyle P, Gray N, Henningfield J, Seffrin J, Zatonski W eds), pp 169–177. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]