Abstract

Thrombolytic drugs activate plasminogen which creates a cleaved form called plasmin, a proteolytic enzyme that breaks the crosslinks between fibrin molecules. The crosslinks create blood clots, so reteplase dissolves blood clots. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is a well-known thrombolytic drug and is fibrin specific. Reteplase is a modified nonglycosylated recombinant form of tPA used to dissolve intracoronary emboli, lysis of acute pulmonary emboli, and handling of myocardial infarction. This protein contains kringle-2 and serine protease domains. The lack of glycosylation means that a prokaryotic system can be used to express reteplase. Therefore, the production of reteplase is more affordable than that of tPA. Different methods have been proposed to improve the production of reteplase. This article reviews the structure and function of reteplase as well as the methods used to produce it.

Keywords: Bacterial expression, fibrin specificity, reteplase, thrombolytic drug

Introduction

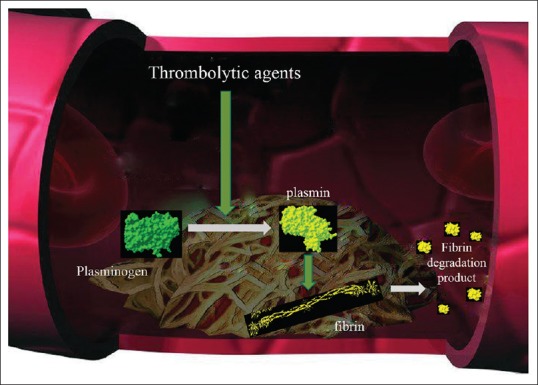

Thrombolytic drugs are used to treat a variety of venous and arterial thromboembolic complaints, especially acute myocardial infarction.[1] These agents are generally plasmin activators which can convert plasminogen to plasmin. The fibrinolytic action of plasmin dissolves insoluble fibrin clots.

Thrombolytic agents can be classified in several ways. One general classification is according to fibrin specificity. Nonfibrin-specific agents comprise streptokinase and urokinase, fibrin-specific agents comprise tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and next generations agents include reteplase, tenecteplase, monteplase, lanoteplase, pamiteplase, desmoteplase (Bat-PA), and chimeric thrombolytics. The drug tPA is the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug from this category. Agents such as reteplase and tenecteplase were created from tPA to modify the efficacy and safety. These new generation thrombolytic benefits such as a prolonged half-life and increased resistance, inhibition by plasminogen activator inhibitors, and increased fibrin specificity have been developed. Reteplase has been approved in Europe and the United States in 1996. According to the Iran FDA, reteplase is available in Iran as powder for solution parenteral containing 10.4 units costing about 5,250,000 rials with an annual sale of 40 vials and also as single-use vial (10 unit/10 ml) costing about 460,000 rials with an annual sale of 31,830 vials. In this review, reteplase is assessed in terms of its structure, function, expression, and production.

Structure of Reteplase

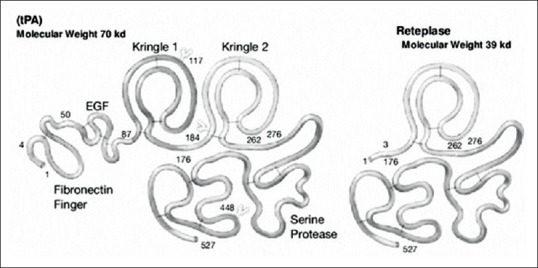

Reteplase is a single-chain deletion mutant of tPA containing 355 amino acids (starting with serine and ending with proline). The tPA molecule comprises five separate structural domains. The zymogen enzyme exists as a single chain, but in the presence of plasmin, it can be cleaved into activated heavy and light chain forms. The heavy chain comprises four domains: a finger domain that is homologous to a part of fibronectin, a growth factor domain that is homologous to the epidermal growth factor, and two unequal kringle domains. The light chains include the serine protease domain, which is homologous to trypsin and chymotrypsin.

Plasmin cleavage occurs at Arg278 in the C-terminal of the kringle-2 domain and produces the two-chain form of tPA. Reteplase comprises the C-terminal kringle-2 and serine protease domains of tPA that lacks valine-4 through the glutamate-175 residue [Figure 1]. Its total molecular weight is 39 kDa and it has nine disulfide bonds in its structure.[2,3,4,5,6,7] The reteplase molecule has three potential N-glycosylation sites which are Asn-12, Asn-48, and Asn-278, respectively.[8] Because the presence of carbohydrate side chains in the structure of reteplase is not necessary for its function, this protein can be expressed in Escherichia coli.

Figure 1.

Tissue plasminogen activator and reteplase schematic figure

Function and Thrombolytic Action of Reteplase

The kringle-2 domain is implicated in binding to fibrin as well as attachment to cytokeratin-8 and endothelial cell surface binding sites. In the protease domain, the functional regions are amino acids 176–527 and 1–3 from the N-terminal.[6,9,10,11,12,13] In contrast to tPA, the epidermal growth factor and fibronectin finger domains are absent in reteplase. The results of these deletions are extended plasma half-life, reduced fibrin specificity,[13] and the ability to penetrate into blood clots.[4,14] Reteplase and tPA do not differ with regard to inhibition by plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1).[15]

The thrombolytic action of reteplase, as for tPA, catalyzes the conversion of the inactive proenzyme plasminogen into the active protease plasmin, which cleaves the Arg-Val bond. This action degrades the fibrin matrix of the thrombus[16] [Figure 2]. In the absence of fibrin, reteplase shows plasminogen activator activity similar to that of tPA, but its binding affinity to fibrin is lower than that of tPA (about 5-fold) due to the deletion of the fibronectin finger region.[9] In the presence of fibrin, the kringle-2 domain is known to stimulate protease activity, but this effect is lower in reteplase than in tPA. This indicates that the fibronectin finger is involved in the stimulation of protease activity in this enzyme.[15] Like tPA, during fibrinolysis, reteplase can be converted into a double-chain form.[3]

Figure 2.

Thrombolytic action of plasminogen activators

Production of Reteplase

Suitable host

Reteplase has been expressed in hosts such as Bacillus subtilis,[17] seaweed such as Laminaria japonica,[18] yeast such as Pichia methanolica[19] and Pichia pastoris,[20,21] and insect cells.[22] The expression levels of reteplase vary significantly among all these systems with problems in protein instability. While literature exists about the expression of reteplase in bacterial systems such as E. coli,[23,24,25,26,27,28,29] some studies about recombinant production of reteplase in E. coli have not been published and the details of some experimental methods are not available.[29]

E. coli is currently considered to be the most widely used host organism for biopharmaceutical production of heterologous recombinant proteins. The expression system of E. coli is desirable because of its ability to quickly reach high cell density, its simplicity, low cost, and FDA approval for human applications.[30,31] Production of reteplase in E. coli remains a challenge. The presence of several disulfide bonds, its rare codon usage, and cytotoxicity are major drawbacks to reteplase expression in E. coli.[31,32] Fathi-Roudsari et al. assessed three E. coli strains (E. coli BL21 [DE3], Rosetta-gami [DE3], and SHuffle T7) for reteplase production. Their results suggest that BL21 (DE3) has the highest level of the expression of this protein, followed by Rosetta-gami (DE3) and Shuffle T7.[33]

Production strategy

Protein production in E. coli can be performed intracellularly (in the form of a soluble protein or inclusion body [IB]) and extracellularly (expressed in periplasmic space). The intercellular production of recombinant proteins has benefits over extracellular production. For example, it eludes proteolysis with periplasmic proteases and leads to continuous recombinant protein production.[34,35]

Intracellular production of reteplase

Although it is expressed intracellularly, reteplase cannot be folded appropriately into the E. coli cytoplasm but is accumulated as IBs.[32] This is caused by the disulfide bonds in reteplase; thus, it requires a refolding process. Fathi-Roudsari et al. used BL21 (DE3), Rosetta-gami (DE3), and SHuffle T7 for reteplase expression. SHuffle T7 is a genetically engineered E. coli strain that is appropriate for soluble production of disulfide-bonded proteins. Rosetta-gami B (DE3) is suitable for improving the expression of eukaryotic proteins in E. coli by overcoming codon bias. This strain increases disulfide bond formation in the cytosolic fraction because of trxB and gor gene mutations.[33]

They reported that, despite an alteration of expression conditions such as a decrease in temperature and a change in oxygen supply and inducer concentration, the oxidizing cytoplasm of Rosetta-gami and SHuffle could not be used for soluble production of reteplase. During the formation of IBs, which are completely insoluble, several folding intermediates also form. It appears that, in the folding intermediates, some disulfide bonds are created between correct cysteine pairs. The cytoplasms of engineered Rosetta-gami and SHuffle T7 can increase the folding intermediates of reteplase in the IBs. During renaturation, these folding intermediates will quickly transit to the native state of the proteins, so the yield of refolding will increase.[36,37,38] Fathi-Roudsari et al. reported that the lower concentration of reteplase gained from Rosetta-gami and SHuffle T7, in comparison with the higher concentrations of BL21, can provide an appropriate yield from refolding.[33]

Zhao et al. reported the reteplase cloning and expression in E. coli using the pET22b vector and an immovable experimental setting (1-mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG], 37°C, shaken for 14 h at 150 rpm) as IB.[6] Studies have tried to increase the expression and production of reteplase. Shafiee et al. examined the effect of conditions such as IPTG concentration, temperature, shaking speed, and glucose concentration on the reteplase expression in E. coli cells as IBs. They reported that maximum protein production was obtained with the addition of 1-mM IPTG at 37°C and 100 rpm of shaking in the absence of glucose.[4]

One parameter that influences the high expression of protein in E. coli is the type of promoter. One of the strongest promoters in E. coli is the tac promoter and a hybrid of trp and lac promoters with an efficacy that is 2–3 times greater than for trp and 7 times greater than lacUV5 promoters. This promoter can be repressed by the lac repressor and induced by IPTG.[39,40,41] Aghaabdollahian et al. used the pGEX-5x-1 plasmid with the tac promoter for expression of reteplase in E. coli TOP10. They successfully cloned and expressed reteplase using the tac promoter in the pGEX-5x-1 expression vector, which is a suitable selection for the optimization of the expression of reteplase in E. coli.[42] In the presence of the GST sequence at the beginning of the insert, the pGEX-5x-1 expression vector creates a pGEX GST fusion protein system, which is commonly used for high-level expression for rapid and efficient purification of fusion proteins expressed in bacterial lysates.[43,44]

Promoters (lac, tac, T7, and arabinose) have been compared in terms of reteplase expression in E. coli. After refolding and activity assays of the produced reteplase, the best results related to the arabinose promoter.[45] For IBs, refolding is necessary to achieve an active protein. Because reteplase has nine disulfide bonds, refolding can be performed by oxidizing/reducing glutathione. This method is used routinely in many studies.[4,46,47,48] In a comparative investigation, Liu et al. produced reteplase with thioredoxin as a fusion protein (Trx-r-PA). They reported a refolding strategy that included the posttreatments of solubilized Trx-r-PA IBs, on-column refolding by size-exclusion chromatography using three gel types, and urea gradient and two-stage temperature control in refolding. They finally removed the Trx-tag by digestion with enterokinase.[49]

Zhao et al. used protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) for reteplase refolding and claimed that their study was the first to apply PDI to succor protein folding of the nine disulfide bonds. They employed reteplase purification with two-step chromatography including lysine-affinity chromatography and CM-sepharose cation-exchange chromatography and reported over 5 × 105 IU/mg specific activity of the purified reteplase.[6] Zhuo et al. suggested that disulfide bonds are the major obstacle to proper folding of this protein and the creation of an IB. They used DsbA/DsbC foldases to enhance soluble expression of recombinant reteplase in E. coli for the first time. DsbA and DsbC simplified protein folding by catalyzing the construction and isomerization of disulfide bonds. Moreover, DsbA shows molecular chaperone activity; thus, Zhuo et al. achieved soluble expression of reteplase. Their results from the fluorescence spectra showed that the structural conformation of soluble reteplase was similar to its native state and they reported 2.35 × 105 IU/mg thrombolytic activity for this produced reteplase.[50]

Fathi-Roudsari et al. investigated optimization of the auto-induction procedure for reteplase expression in a soluble and active form in E. coli. They reported that the use of an auto-induction strategy at 37°C showed that Rosetta-gami (DE3) had the maximum level of active and soluble reteplase production compared to the E. coli strains of BL21 (DE3) and Shuffle T7. They said that temperature predominantly influenced the level of active reteplase production. In other words, decreasing the temperature to 25°C and 18°C improved the level of active reteplase by 20% and 60%, respectively. Another factor that affected the active production of reteplase in cytoplasm, they reported, is the composition of the auto-induction medium. The use of more highly enriched auto-induction medium with a super broth base that included trace elements considerably increased the biologically active reteplase by 30%.[51]

Extracellular production of reteplase

The secretory production of recombinant proteins in E. coli has been used for the production of pharmaceutical proteins.[34,52] Compared with cytoplasmic production, targeting of the expressed protein in periplasmic space or by the culture medium simplifies downstream processing and reduces production costs.[53] Two studies expressed reteplase in E. coli TOP10 with pBAD/gIIIA vector. This vector allows secretion of the expressed protein into periplasmic space. In these studies, low amounts of the expressed reteplase were detected in the periplasmic space. Most of them were present as IBs inside the cell. It has been reported that this might be due to the high expression of proteins which affect the export mechanisms of cells for sending recombinant proteins into periplasmic space.[48,54]

Chen et al. provided a strategy for the construction of leaky strains for the extracellular production of the target proteins.[55] Leaky strains can be created by knocking out the genes associated with the biosynthesis of the cell membranes and walls, particularly the outer membrane genes such as lpp encoding Braun's lipoprotein.[56] In their study, genes such as lpp and mrcB (encoding peptidoglycan synthetase) mutated.[57] Their results showed that mutants with in-frame single/double deletion of genes (mrcB and lpp) could not effectively leak reteplase due to protein expression in the cytoplasm. Khodabakhsh et al. compared the cytoplasmic and periplasmic production of reteplase. They reported that the cytoplasmic expression of reteplase was a more appropriate system for the expression of this protein and that high amounts of reteplase were obtained from the expressed protein in the form of IBs though it required an additional refolding step for activation.[54]

Discussion

Thrombolytic drugs are considered to be life-savers due to their action in dissolving thrombi and achieving reperfusion. Nevertheless, its immunogenicity, fibrin specificity, half-life, and the cost of treatment are determining factors that influence the use of such drugs. There is an ongoing need for developing novel molecules at lower costs to solve these problems.

In the developed countries, tPA is commonly used while, in developing countries, streptokinase remains the drug of choice for thrombolytic therapy because it is less expensive.[58] Because this medication is not fibrin specific, it can cause the breakdown of circulating fibrinogen, which will considerably affect hemostasis.[59] The use of recombinant DNA technology and optimized bioprocessing strategies can help to develop new drugs and reduce costs.

Conclusion

Reteplase is a thrombolytic drug that is a nonglycosylated derivation of tPA. Its production can be achieved in E. coli; thus, the cost of production is less than that of other expression systems, such as mammalian cells. With the use of the optimized production conditions such as the utilization of the best host strain, expression, and purification strategies, optimal production of this drug can be achieved.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Albers GW, Clark WM, Madden KP, Hamilton SA. ATLANTIS trial: Results for patients treated within 3 hours of stroke onset. Alteplase thrombolysis for acute noninterventional therapy in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2002;33:493–5. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver WD, Cerqueira M, Hallstrom AP, Litwin PE, Martin JS, Kudenchuk PJ, et al. Prehospital-initiated vs. hospital-initiated thrombolytic therapy. The myocardial infarction triage and intervention trial. JAMA. 1993;270:1211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llevadot J, Giugliano RP, Antman EM. Bolus fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2001;286:442–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shafiee F, Moazen F, Rabbani M, Sadeghi HM. Expression and activity evaluation of reteplase in Escherichia coli TOP10. J Param Sci. 2015;6:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appadu B, Barber K. Drugs affecting coagulation. Anaesth Intens Care Med. 2016;17:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y, Ge W, Kong Y, Zhang C. Cloning, expression, and renaturation studies of reteplase. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;13:989–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shojaosadati SA, Naeimipour S, Fazeli A. FTIR investigation of secondary structure of Reteplase inclusion bodies produced in Escherichia coli in terms of urea concentration (Spring 2017) Iran J Pharm Res. 2017:1–15. doi: 10.22037/ijpr.2020.1101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandi N, Sundaram KR, Tandra SK, Bandyopadhyay S, Padmanabhan S. Asn and asn: Critical residues for in vitro biological activity of reteplase. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:172484. doi: 10.1155/2010/172484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohnert U, Rudolph R, Verheijen JH, Weening-Verhoeff EJ, Stern A, Opitz U, et al. Biochemical properties of the kringle 2 and protease domains are maintained in the refolded t-PA deletion variant BM 06.022. Protein Eng. 1992;5:93–100. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin U, Bader R, Böhm E, Kohnert U, von Möllendorf E, Fischer S, et al. BM 06.022: a novel recombinant plasminogen activator. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 1993;11:299–311. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noble S, McTavish D. Reteplase. A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in the management of acute myocardial infarction. Drugs. 1996;52:589–605. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stringer KA. Biochemical and pharmacologic comparison of thrombolytic agents. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16:119S–26S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Pulicherla K, Ram KS, Rao K. Evolutionary trend of thrombolytics. Int J Bio Sci Bio Technol. 2010;2:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasbiswas A, Hiremath J, Trailokya A. Overview of reteplase, A novel thrombolytic agent in Indian context. Cardiol Pharmacol. 2015;4:136–142. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordt TK, Bode C. Thrombolysis: Newer thrombolytic agents and their role in clinical medicine. Heart. 2003;89:1358–62. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.11.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson D, Siddiqui MA, Scott LJ, Hilleman DE. Reteplase: A review of its use in the management of thrombotic occlusive disorders. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2006;6:265–85. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200606040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang LF, Hum WT, Kalyan NK, Lee SG, Hung PP, Doi RH, et al. Synthesis and refolding of human tissue-type plasminogen activator in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1989;84:127–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Jiang P, Gao J, Liao J, Sun S, Shen Z, et al. Recombinant expression of rt-PA gene (encoding reteplase) in gametophytes of the seaweed Laminaria japonica (Laminariales, phaeophyta) Sci China C Life Sci. 2008;51:1116–20. doi: 10.1007/s11427-008-0143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jie J, Cheng-Ying J, Lian-Xiang D. Cloning of rPA gene and expression of the gene in Pichia methanolica. J S China Univ Sci Technol. 2007;12:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu-Guang F, Ju C, Li H, Ying-Ping Z, Si-Liang Z. Degradation of reteplase expressed by recombinant Pichia pastoris. J East China Univ Sci Technol. 2006;3:2006–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang SG, Chu J, Huang L, Zhuang YP, Zhang SL. Effects of temperature on expression of reteplase in Pichia pastoris. Ind Microbiol. 2007;4:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aflakiyan S, Sadeghi HM, Shokrgozar M, Rabbani M, Bouzari S, Jahanian-Najafabadi A, et al. Expression of the recombinant plasminogen activator (reteplase) by a non-lytic insect cell expression system. Res Pharm Sci. 2013;8:9–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pennica D, Holmes WE, Kohr WJ, Harkins RN, Vehar GA, Ward CA, et al. Cloning and expression of human tissue-type plasminogen activator cDNA in E.coli. Nature. 1983;301:214–21. doi: 10.1038/301214a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuiper J, Van’t Hof A, Otter M, Biessen EA, Rijken DC, van Berkel TJ, et al. Interaction of mutants of tissue-type plasminogen activator with liver cells: Effect of domain deletions. Biochem J. 1996;313(Pt3):775–80. doi: 10.1042/bj3130775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manosroi J, Tayapiwatana C, Götz F, Werner RG, Manosroi A. Secretion of active recombinant human tissue plasminogen activator derivatives in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2657–64. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2657-2664.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattes R. The production of improved tissue-type plasminogen activator in Escherichia coli. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:325–36. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallejo LF, Rinas U. Strategies for the recovery of active proteins through refolding of bacterial inclusion body proteins. Microb Cell Fact. 2004;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dormiani K, Khazaie Y, Sadeghi HM, Rabbani M, Moazen F. Cloning and expression of a human tissue plasminogen activator variant: K2S in Escherichia coli. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10:946–9. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.946.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadeghi HM, Rabbani M, Rismani E, Moazen F, Khodabakhsh F, Dormiani K, et al. Optimization of the expression of reteplase in Escherichia coli. Res Pharm Sci. 2011;6:87–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marisch K, Bayer K, Cserjan-Puschmann M, Luchner M, Striedner G. Evaluation of three industrial Escherichia coli strains in fed-batch cultivations during high-level SOD protein production. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:58–69. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long X, Gou Y, Luo M, Zhang S, Zhang H, Bai L, et al. Soluble expression, purification, and characterization of active recombinant human tissue plasminogen activator by auto-induction in E.coli. BMC Biotechnol. 2015;15:13–22. doi: 10.1186/s12896-015-0127-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HJ, Im HN. Soluble expression and purification of human tissue-type plasminogen activator protease domain. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2010;31:2607–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fathi-Roudsari M, Akhavian-Tehrani A, Maghsoudi N. Comparison of three Escherichia coli strains in recombinant production of reteplase. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2016;8:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi JH, Lee SY. Secretory and extracellular production of recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;64:625–35. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosano GL, Ceccarelli EA. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: Advances and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:172. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudolph R, Lilie H. In vitro folding of inclusion body proteins. FASEB J. 1996;10:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baneyx F, Mujacic M. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1399–408. doi: 10.1038/nbt1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YD, Zhang GF, Li JJ, Chen J, Wang YJ, Ding H, et al. Identification of an oxidative refolding intermediate of recombinant consensus interferon from inclusion bodies and design of a two-stage strategy to promote correct disulfide-bond formation. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2007;48:189–98. doi: 10.1042/BA20070047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagdasarian MM, Amann E, Lurz R, Rückert B, Bagdasarian M. Activity of the hybrid trp-lac (tac) promoter of Escherichia coli in pseudomonas putida. Construction of broad-host-range, controlled-expression vectors. Gene. 1983;26:273–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Boer HA, Comstock LJ, Vasser M. The tac promoter: A functional hybrid derived from the trp and lac promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:21–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulligan ME, Brosius J, McClure WR. Characterization in vitro of the effect of spacer length on the activity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase at the TAC promoter. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3529–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aghaabdollahian S, Rabbani M, Ghaedi K, Sadeghi HM. Molecular cloning of reteplase and its expression in E.coli using tac promoter. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:190. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.140622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DB, Johnson KS. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guan KL, Dixon JE. Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: An improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal Biochem. 1991;192:262–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90534-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sadeghi HM. Cloning and expression of reteplase in E.coli using different prokaryotic promoters. Res Pharm Sci. 2012;7:941. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao L, Zhang C, Li L, Liang L, Deng X, Wu W, et al. Construction, expression and refolding of a bifunctional fusion protein consisting of C-terminal 12-residue of hirudin-PA and reteplase. Protein J. 2012;31:328–36. doi: 10.1007/s10930-012-9407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khodabakhsh F, Dehghani Z, Zia MF, Rabbani M, Sadeghi HM. Cloning and expression of functional reteplase in Escherichia coli TOP10. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2013;5:168–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shafiee F, Moazen F, Rabbani M, Mir Mohammad Sadeghi H. Optimization of the expression of reteplase in Escherichia coli TOP10 using arabinose promoter. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2015;10:1–8. doi: 10.17795/jjnpp-16676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu H, Zhou X, Zhang Y. A comparative investigation on different refolding strategies of recombinant human tissue-type plasminogen activator derivative. Biotechnol Lett. 2006;28:457–63. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-0001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhuo XF, Zhang YY, Guan YX, Yao SJ. Co-expression of disulfide oxidoreductases dsbA/DsbC markedly enhanced soluble and functional expression of reteplase in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 2014;192:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fathi-Roudsari M, Maghsoudi N, Maghsoudi A, Niazi S, Soleiman M. Auto-induction for high level production of biologically active reteplase in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2018;151:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mergulhão FJ, Summers DK, Monteiro GA. Recombinant protein secretion in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Adv. 2005;23:177–202. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoon SH, Kim SK, Kim JF. Secretory production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Recent Pat Biotechnol. 2010;4:23–9. doi: 10.2174/187220810790069550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khodabakhsh F, Zia MF, Moazen F, Rabbani M, Sadeghi HM. Comparison of the cytoplasmic and periplasmic production of reteplase in Escherichia coli. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;43:613–23. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2013.764896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen ZY, Cao J, Xie L, Li XF, Yu ZH, Tong WY, et al. Construction of leaky strains and extracellular production of exogenous proteins in recombinant Escherichia coli. Microb Biotechnol. 2014;7:360–70. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shin HD, Chen RR. Extracellular recombinant protein production from an Escherichia coli lpp deletion mutant. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;101:1288–96. doi: 10.1002/bit.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertsche U, Breukink E, Kast T, Vollmer W. In vitro murein peptidoglycan synthesis by dimers of the bifunctional transglycosylase-transpeptidase PBP1B from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38096–101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adivitiya, Khasa YP. The evolution of recombinant thrombolytics: Current status and future directions. Bioengineered. 2017;8:331–58. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2016.1229718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang X, Moreton FC, Kalladka D, Cheripelli BK, MacIsaac R, Tait RC, et al. Coagulation and fibrinolytic activity of tenecteplase and alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:3543–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]