Phosphate starvation, but not nitrogen starvation, changes the cytosolic free calcium signatures of Arabidopsis thaliana roots in response to mechanical, salt, osmotic, and oxidative stress as well as to extracellular nucleotides.

Abstract

Phosphate (Pi) deficiency strongly limits plant growth, and plant roots foraging the soil for nutrients need to adapt to optimize Pi uptake. Ca2+ is known to signal in root development and adaptation but has to be tightly controlled, as it is highly toxic to Pi metabolism. Under Pi starvation and the resulting decreased cellular Pi pool, the use of cytosolic free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt) as a signal transducer may therefore have to be altered. Employing aequorin-expressing Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), we show that Pi starvation, but not nitrogen starvation, strongly dampens the [Ca2+]cyt increases evoked by mechanical, salt, osmotic, and oxidative stress as well as by extracellular nucleotides. The altered root [Ca2+]cyt response to extracellular ATP manifests during seedling development under chronic Pi deprivation but can be reversed by Pi resupply. Employing ratiometric imaging, we delineate that Pi-starved roots have a normal response to extracellular ATP at the apex but show a strongly dampened [Ca2+]cyt response in distal parts of the root tip, correlating with high reactive oxygen species levels induced by Pi starvation. Excluding iron, as well as Pi, rescues this altered [Ca2+]cyt response and restores reactive oxygen species levels to those seen under nutrient-replete conditions. These results indicate that, while Pi availability does not seem to be signaled through [Ca2+]cyt, Pi starvation strongly affects stress-induced [Ca2+]cyt signatures. These data reveal how plants can integrate nutritional and environmental cues, adding another layer of complexity to the use of Ca2+ as a signal transducer.

Plant roots foraging in the soil have to sense, transduce, and respond to fluctuations in water and nutrients plus a multitude of stresses they may additionally be subjected to. Plants employ a wide range of signal transducers, with free calcium ion (Ca2+) being a common second messenger in the response to stress stimuli. Biotic and abiotic stresses (including mechanical, salt, osmotic, and oxidative stress) trigger rapid and transient modulations in cytosolic and organellar free Ca2+ (Knight et al., 1991, 1992, 1997a; Kiegle et al., 2000; Monshausen et al., 2009; Loro et al., 2012, 2016; Bonza et al., 2013; Laohavisit et al., 2013; Behera et al., 2018; Manishankar et al., 2018). These Ca2+ signatures are held to be specific to the stimulus and result in stimulus-specific outcomes, enabled by suites of decoding proteins (Whalley et al., 2011; Whalley and Knight, 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Lenzoni et al., 2018).

Recently, Ca2+ has been described as also functioning in signaling nutrient status and availability. In the model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), nitrate resupply to initially nitrate-starved roots prompted a rapid (within seconds) and monophasic increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt), followed by an increase in nuclear [Ca2+] (Riveras et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). Potassium (K+) deficiency was found to trigger two distinct [Ca2+]cyt elevations within the Arabidopsis root, the first response occurring within 1 to 4 min and the second response within 18 to 32 h after the onset of K+ deficiency (Behera et al., 2017). [Ca2+]cyt signaling was further found to be necessary for vacuolar magnesium (Mg2+) detoxification in a high Mg2+ environment (Tang et al., 2015).

Another nutrient of great importance for optimal plant growth is inorganic phosphate (Pi). Pi-limited conditions are known to induce profound changes in plant growth and metabolism. On a systemic level, root growth is favored over shoot growth, indicative of maximizing soil exploration and, thus, nutrient uptake (Gruber et al., 2013). In addition, root system architecture is remodeled, which has been well described in many crop species, such as barley (Hordeum vulgare), maize (Zea mays), rice (Oryza sativa), and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), as well as Arabidopsis (Péret et al., 2014). Multicomponent nutrient studies found Pi to be the predominant nutrient controlling primary root length (Gruber et al., 2013; Kellermeier et al., 2014). On a cellular level, metabolism shifts to alternative pathways that consume less Pi (Pratt et al., 2009; Plaxton and Tran, 2011; Nakamura, 2013; Pant et al., 2015). The Pi deficiency response is orchestrated by intricate signaling networks, involving hormones, nutrient cross talk, and transcriptional and translational feedback loops (for review, see Abel, 2017; Chien et al., 2018). Ca2+ has been hypothesized to be involved as a signal transducer (Chiou and Lin, 2011; Linn et al., 2017; Chien et al., 2018), but this has not been confirmed to date.

While the involvement of Ca2+ as a second messenger in nutrient signaling is now beginning to be explored, few studies have examined the impact of nutrient deficiency on Ca2+ signaling per se. Boron-deprived tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) BY-2 cells (expressing cytosolic aequorin as a luminometric reporter of [Ca2+]cyt) sustained an enhanced [Ca2+]cyt signature when challenged with 3 mM Ca2+ compared with boron-replete cells (Koshiba et al., 2010). Boron deficiency caused an increase in steady-state [Ca2+]cyt of Arabidopsis roots, but the consequences for stress-induced Ca2+ signatures were not examined (Quiles-Pando et al., 2013).

Thus, we set out to test how Pi starvation of Arabidopsis might influence the root’s use of Ca2+ as a signal, employing a range of abiotic stresses known to evoke robust, rapid, and transient [Ca2+]cyt signatures (mechanical, salt, osmotic, and oxidative stress). Additionally, as mechanical stimulation, salt, and osmotic stress increase the accumulation of extracellular ATP (eATP; Weerasinghe et al., 2009; Dark et al., 2011), which in turn transiently increases [Ca2+]cyt (Demidchik et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2010a, 2010b; Costa et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2014), we also tested the root response to extracellular purine nucleotides.

We show that Pi starvation, but not nitrogen (N) starvation, strongly altered [Ca2+]cyt signatures in response to all abiotic stresses and extracellular nucleotides tested. Furthermore, Pi-starved root apices of Arabidopsis showed a distinct spatiotemporal [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP. This was remodeled during development and was dependent on iron (Fe) availability and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production but could be reversed by Pi resupply. These data reveal how nutritional status adds another so far unexplored level of complexity to the use of [Ca2+]cyt as a signal transducer and further our understanding of how plants integrate various environmental cues.

RESULTS

Pi, But Not N, Starvation Dampens the [Ca2+]cyt Response to Abiotic Stresses in Arabidopsis Root Tips

To determine if Pi starvation alters stress-induced [Ca2+]cyt signatures, Arabidopsis seedlings ubiquitously expressing cytosolic (apo)aequorin were grown on Pi-replete conditions (0.625 mM KH2PO4; full Pi), lowered Pi conditions (0.1 mM KH2PO4; medium Pi), or chronically starved of Pi (0 mM KH2PO4; zero Pi). As has been reported previously (Williamson et al., 2001; Svistoonoff et al., 2007; Balzergue et al., 2017), Pi starvation for 10 d led to significantly shorter primary roots (mean root length ± se: full Pi, 6.01 ± 0.06 cm; medium Pi, 4.42 ± 0.04 cm; zero Pi, 2.69 ± 0.04 cm [P < 0.001 for all comparisons]; Supplemental Table S1). To account for differences in root growth and architecture induced by Pi growth regime, a fixed length of the primary root (the first 1 cm from the apex) from an 11-d-old seedling was challenged with acute abiotic stress and aequorin luminescence was recorded every 1 s for 155 s (Fig. 1). As the experimental setup necessitates the injection of treatment solutions, control solution treatments were run with every set of experiments to control for the effect of mechanical stimulation.

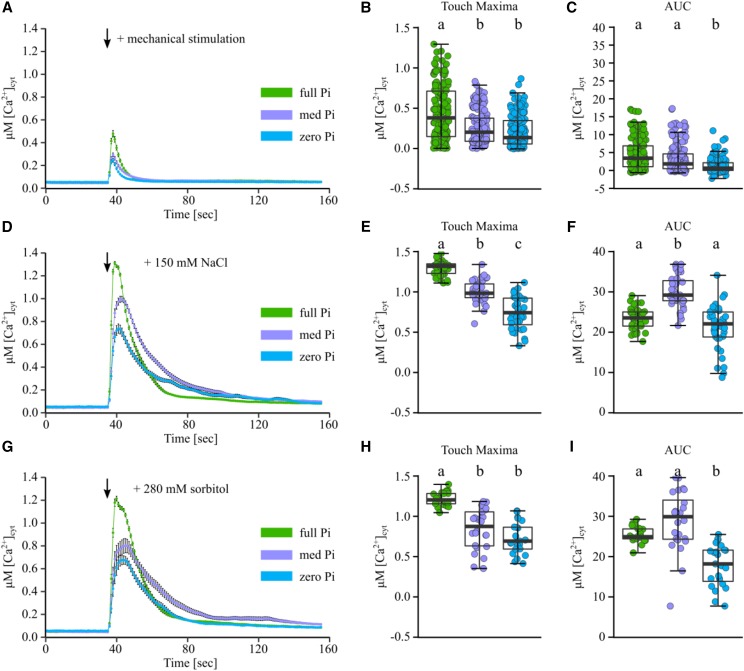

Figure 1.

Pi-starved root tips have a dampened [Ca2+]cyt response to mechanical, salt, and osmotic stress. Arabidopsis Columbia-0 (Col-0) aequorin-expressing seedlings were grown on full, medium (med), or zero Pi (green, purple, and blue traces, respectively). Individual root tips (1 cm) of 11-d-old seedlings were challenged with treatments applied at 35 s (black arrows), and [Ca2+]cyt was measured for 155 s. A, Mechanical stimulation (control solution). Time-course traces represent means ± se from 18 independent trials, with n = 150 to 155 root tips per growth condition averaged per data point. B and C, Time-course data were analyzed for touch maxima (B) and area under the response curve (AUC; C), both baseline subtracted, with each dot representing an individual data point (see Supplemental Fig. S1 for details). The middle line in the box plot denotes the median. D to F, Responses to 150 mM NaCl (three independent trials, n = 35–36 root tips). G to I, Responses to 280 mM sorbitol (three independent trials, n = 22–24 root tips). ANOVA with posthoc Tukey’s test was used to assess statistical differences; different lowercase letters denote significant differences (P < 0.05).

An immediate and monophasic increase in [Ca2+]cyt was observed upon mechanical stimulation (application of control solution; Fig. 1, A–C), salt stress (150 mM sodium chloride [NaCl]; Fig. 1, D–F), or an equivalent osmotic stress (280 mM d-sorbitol; Fig. 1, G–I). The response to mechanical stimulation was variable in root tips of all Pi growth conditions, likely due to limitations of the experimental setup, but overall, the Pi-starved root tip response was significantly lower. The response to salt and osmotic stress was as immediate as the response to mechanical stimulation, but of much greater amplitude and duration in root tips from all Pi growth conditions. In all cases, Pi starvation significantly dampened the stress-induced [Ca2+]cyt response (as quantified by peak maxima [Fig. 1, B, E, and H] and area under the curve [as a proxy of how much [Ca2+]cyt was mobilized upon stress treatment; Fig. 1, C, F, and I]; see Supplemental Fig. S1 for details). For all stress experiments, Pi-replete root tips showed the strongest [Ca2+]cyt response, medium Pi root tips showed a moderately dampened [Ca2+]cyt response, and Pi-starved root tips showed the most strongly impaired [Ca2+]cyt response.

To test if this dampened [Ca2+]cyt response was specific to Pi nutrition or due to a more general nutrient deficiency response, we assayed root tips starved of another macronutrient, N. Primary root lengths of severely N-starved plants (0 mM N) were comparable to zero Pi-grown roots (zero N, 2.5 ± 0.13 cm [P = 0.203]; Supplemental Table S1). However, N-starved root tips showed a [Ca2+]cyt response to mechanical stimulation, salt, and osmotic stress that was similar to that of nutrient-replete root tips (Supplemental Fig. S2). These results indicate that Pi nutrition specifically alters the [Ca2+]cyt response to abiotic stresses.

Pi Starvation Alters the Root Tip [Ca2+]cyt Response to Extracellular Nucleotides and ROS

Mechanical stimulation, salt, and osmotic stress are known to evoke the accumulation of eATP, which in turn triggers increases in ROS (Kim et al., 2006; Song et al., 2006; Demidchik et al., 2009, 2011; Chen et al., 2017), and ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) induce [Ca2+]cyt increases (Price et al., 1994; Rentel and Knight, 2004; Demidchik et al., 2007; Richards et al., 2014). Therefore, we next challenged aequorin-expressing root tips from 11-d-old seedlings, grown on full/medium/zero Pi conditions, with 0.1 or 1 mM eATP. eATP treatment evoked robust multiphasic [Ca2+]cyt increases in full Pi-grown root tips (Fig. 2), as reported previously (Demidchik et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2010b). The different phases of the response were classified as an immediate touch response (0–6 s after treatment application), followed by peak 1 (7–28 s after treatment application) and subsequent peak 2 (29–120 s after treatment application; see Supplemental Fig. S1 for details). The touch response elicited by eATP was variable but overall not significantly different from the application of control solution alone (Fig. 1A) and was nonresponsive to an increase in eATP concentration (0.1 mM eATP [Fig. 2B] and 1 mM eATP [Fig. 2G]), indicating that this initial response was due to the mechanical stimulation of treatment application rather than to eATP perception.

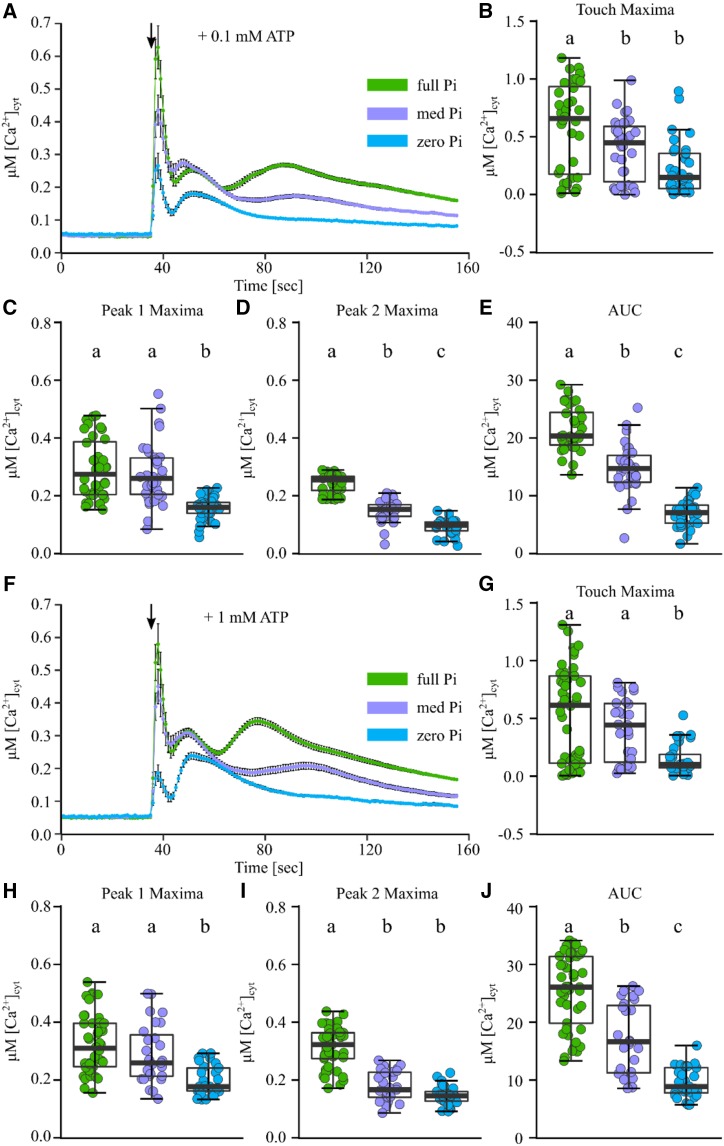

Figure 2.

Pi-starved root tips show a dampened [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP. Arabidopsis Col-0 aequorin-expressing seedlings were grown on full, medium (med), or zero Pi (green, purple, and blue traces, respectively). Individual root tips (1 cm) of 11-d-old seedlings were challenged with treatments applied at 35 s (black arrows), and [Ca2+]cyt was measured for 155 s. A, Treatment with 0.1 mM ATP. Time-course traces represent means ± se from six independent trials, with n = 34 to 36 individual root tips averaged per data point. B to E, Time-course data were analyzed for touch maxima (B), peak 1 maxima (C), peak 2 maxima (D), and area under the response curve (AUC; E), all baseline subtracted, with each dot representing an individual data point (see Supplemental Fig. S1 for details). The middle line in the box plot denotes the median. F to J, Responses to 1 mM ATP (five independent trials, n = 27–45 root tips per growth condition). ANOVA with posthoc Tukey’s test was used to assess statistical differences; different lowercase letters denote significant differences (P < 0.05).

In contrast, the subsequent [Ca2+]cyt increases (defined as peak 1 and peak 2) were specific to eATP treatment, and their magnitude was dependent on root Pi status. Peak 1 maxima were similar between full Pi- and medium Pi-grown root tips but significantly dampened in zero Pi-grown root tips in response to 0.1 mM ATP (Fig. 2C) and 1 mM ATP (Fig. 2H). Peak 2 maxima were significantly dampened in medium Pi root tips compared with full Pi root tips, with zero Pi root tips mostly lacking any apparent [Ca2+]cyt increase within that phase (Fig. 2, D and I). Overall, the more Pi starved the roots, the less [Ca2+]cyt was mobilized in response to eATP (based on the area under the response curves; Fig. 2, E and J). While increasing the eATP concentration 10-fold (from 0.1 to 1 mM eATP) significantly increased the [Ca2+]cyt mobilized in full Pi root tips, medium and zero Pi root tips were insensitive to an increase in eATP concentration.

As up to 2 mM Pi could potentially be liberated readily from 1 mM eATP, and this Pi pulse itself might evoke a [Ca2+]cyt response, we treated root tips with a Pi source alone. Application of 2 mM Pi led to a rapid and monophasic increase in [Ca2+]cyt, very similar in shape, duration, and amplitude to control solution treatment across all three Pi growth regimes (Supplemental Fig. S3). This indicated that under the Pi starvation conditions tested, Pi alone did not trigger an increase in [Ca2+]cyt, in contrast to what had been reported for nitrate resupply in a similar setup (Riveras et al., 2015). To further test if ATP hydrolysis played a role in the differing [Ca2+]cyt signatures, ADP and a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog (adenosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate tetralithium [γ-ATP]) were applied to root tips from the different Pi growth regimes. ADP and γ-ATP treatment (1 mM) resulted in [Ca2+]cyt signatures strikingly similar to those observed with 1 mM eATP treatment (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5), indicating that ATP hydrolysis could not mechanistically explain the altered [Ca2+]cyt signature of Pi-starved roots.

Next, we applied ROS, as 1 and 5 mM H2O2, to excised root tips. This treatment induced a rapid increase in [Ca2+]cyt followed by a pronounced secondary increase (Supplemental Fig. S6). Full Pi- and medium Pi-grown root tips showed a similar [Ca2+]cyt response, while zero Pi-grown root apices showed a significantly dampened secondary response to both H2O2 concentrations tested (Supplemental Fig. S6). N-starved root apices did not show a dampened response to either 1 mM eATP (Supplemental Fig. S7) or 1 mM H2O2 (Supplemental Fig. S8), again indicating that the severely altered [Ca2+]cyt signature observed in Pi-starved roots was not a general response to nutrient starvation but a consequence specific to Pi nutrition.

Pi-Starved Roots Respond to eATP at the Root Apex, But a Secondary [Ca2+]cyt Response in the Distal Region Is Lost

As the aequorin-based [Ca2+]cyt determinations did not allow spatial resolution, we employed ratiometric imaging to map the [Ca2+]cyt response of the root. Arabidopsis Col-0 constitutively expressing the ratiometric [Ca2+]cyt reporter Yellow Cameleon YC3.6 (nuclear export signal [NES]-YC3.6; Krebs et al., 2012) was grown on full Pi or zero Pi, and intact 10-d-old plants were mounted into a custom-built perfusion chamber (Behera and Kudla, 2013) with shoots exposed to air and roots constantly superfused with control imaging solution. This constant superfusion system circumvented mechanical stimulation due to treatment injection (present in aequorin-based assays), excluding any touch response. As eATP application had so far produced the most prominent Pi-dependent [Ca2+]cyt response and was at the crossroads of signaling in other stress pathways, we used it as the standard treatment from here onward.

In Pi-replete roots of NES-YC3.6-expressing seedlings (Fig. 3A), superfusion with 1 mM eATP led to a strong increase in cpVenus/cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) ratio over prestimulus levels in the apex (approximately within the first 1 mm), which was sustained over the period of eATP treatment (3 min; visualized as a representative kymograph in Figure 3B). Approximately 30 to 40 s after this initial response, a secondary increase in ratio occurred in the more distal part of the root tip (1 mm or more from the root apex), which appeared to propagate along the root (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Movie S1). These two distinct increases in [Ca2+]cyt were reminiscent of what had been termed peak 1 and peak 2 in aequorin-based assays (Fig. 2).

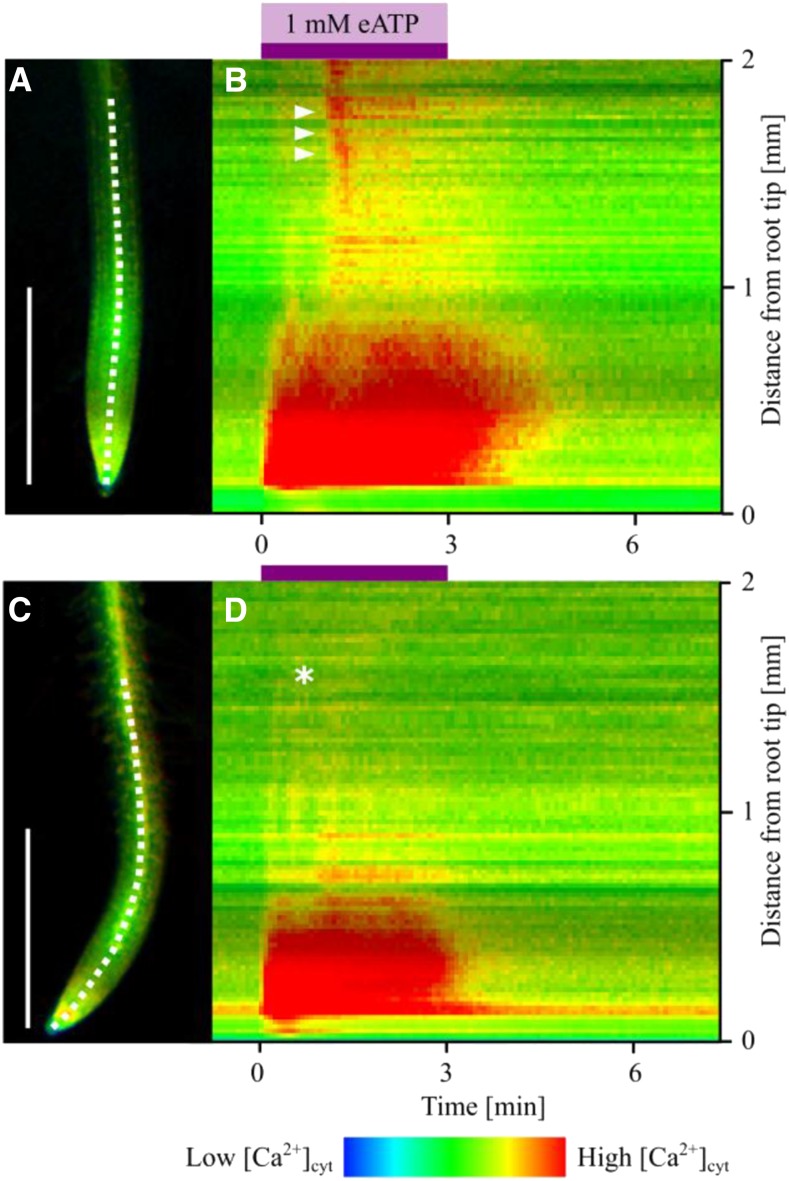

Figure 3.

eATP elicits two spatiotemporally distinct [Ca2+]cyt increases in the root, which are altered by Pi starvation. A, Representative full Pi-grown Arabidopsis Col-0 root expressing NES-YC3.6. The white dashed line in the root micrograph indicates the line used for kymograph extraction. B, Kymograph depicts temporal and spatial changes in [Ca2+]cyt of a representative full Pi-grown root in response to a 3-min 1 mM eATP treatment (purple bar), preceded and followed by superfusion with control imaging solution. C and D, Representative zero Pi-grown root. White triangles indicate secondary increase in [Ca2+]cyt in the full Pi root (B), which is missing in the zero Pi root (marked by the white star; D). Bars = 1 mm.

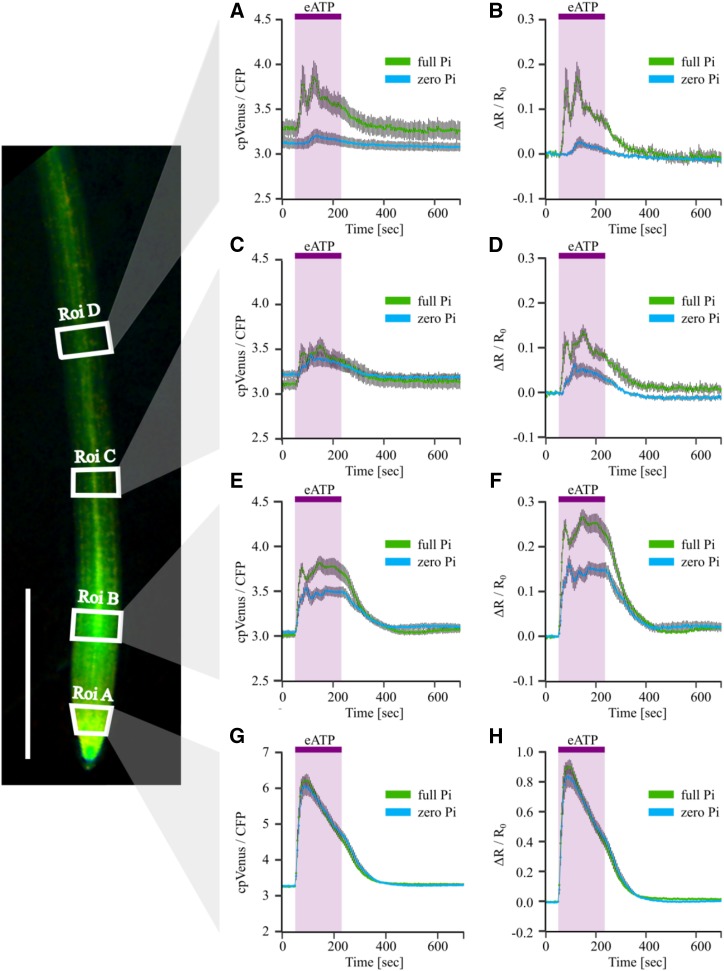

Pi-starved roots (Fig. 3C) sustained a similar increase of cpVenus/CFP ratio at the root apex in response to 1 mM eATP. In more distal parts of the roots (1 mm or more from the root apex), Pi-starved roots only showed a slight or no ratio increase at all in response to eATP treatment (Fig. 3D, representative kymograph; Supplemental Movie S2). This lack of a secondary response resembled the absence of peak 2 in Pi-starved aequorin-expressing root tips (Fig. 2). Quantifying the ratiometric changes occurring in response to eATP in specific regions of interest (ROIs) along the root (apical 2.5 mm; see micrograph in Fig. 4) corroborated these observations. Pi starvation effectively abolished an eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevation in more distal regions (Fig. 4, A–D) and dampened it nearer to the apex (Fig. 4, E and F). However, at the apex, Pi starvation had no effect on the eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevation (Fig. 4, G and H; n = 7–9 roots per growth condition), indicating that Pi-starved roots were not impaired in perceiving eATP per se.

Figure 4.

Quantification of differential [Ca2+]cyt responses of Pi-starved roots to eATP. Arabidopsis Col-0 expressing NES-YC3.6 was grown on full or zero Pi. In a superfusion chamber, a root of a 10-d-old seedling was superfused with imaging solution before switching to 1 mM eATP (applied 50–230 s after the start of image acquisition; purple shading), followed by washout with imaging solution. On the left, a representative root with annotated ROIs (Roi; white boxes), analyzed and plotted over time in A to H: Roi D (A and B); Roi C (C and D); Roi B (E and F); and Roi A (G and H). A, C, E, and G, Mean Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) ratio (cpVenus/CFP) ± se, background subtracted. B, D, F, and H, Normalized FRET ratio (ΔR/R0) ± se of full Pi roots (green traces) and zero Pi roots (blue traces). Data from three independent trials are shown, with n = 7 to 9 individual roots per growth condition. Bar in root image at left = 1 mm.

The Altered [Ca2+]cyt Signature Manifests during Prolonged Pi Starvation and Is Reversed by Pi Resupply

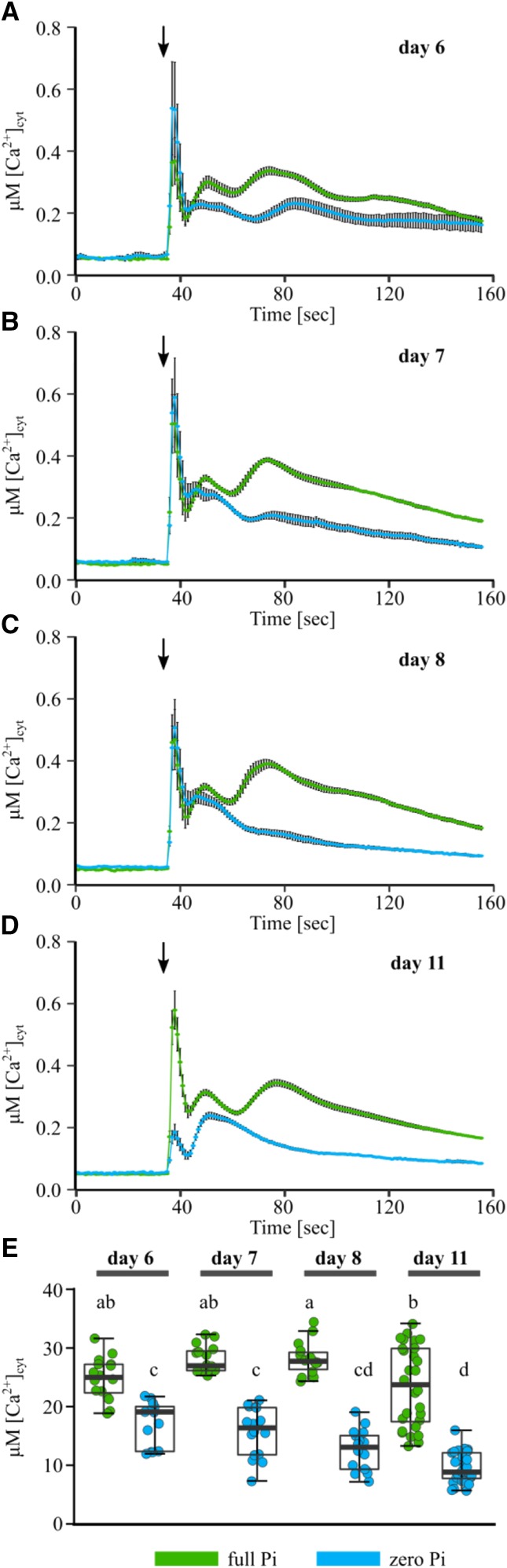

To place the response of Pi-starved root tips into developmental context, we next tested aequorin-expressing Arabidopsis of different ages for an altered [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP. The youngest root material tested (on day 6) did not yet significantly differ in primary root length between full Pi- and zero Pi-grown plants (mean primary root length ± se: full Pi, 1.99 ± 0.08 cm; zero Pi, 1.83 ± 0.04 cm [P = 0.908]). In 7-d-old (or older) material, a significantly shorter primary root was observed in Pi-starved seedlings (Supplemental Table S1).

Assaying 6-, 7-, 8-, and 11-d-old full Pi-grown root tips (1 cm) replicated the characteristic multiphasic [Ca2+]cyt response to 1 mM eATP throughout development (Fig. 5, A–D), as well as eliciting [Ca2+]cyt responses of comparable magnitude (quantified as area under the response curves; Fig. 5E). In contrast, 6-d-old Pi-starved root tips showed a [Ca2+]cyt response comparable in shape to the response of Pi-replete tips, but it was dampened in magnitude (Fig. 5A). Seven- and 8-d-old Pi-starved tips (1 cm) showed a much dampened peak 2, which was completely absent in 11-d-old tips (Fig. 5, B–D). Concomitantly, Pi-starved tips showed a decrease in total mobilized [Ca2+]cyt, with prolonged growth on zero Pi medium (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Pi starvation modulates the root tip [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP during development. Arabidopsis Col-0 aequorin-expressing seedlings were grown on full or zero Pi (green and blue traces, respectively). A to D, Root tips (1 cm) of 6-d-old (A), 7-d-old (B), 8-d-old (C), or 11-d-old (D) seedlings were challenged with 1 mM eATP applied at 35 s (black arrows), and [Ca2+]cyt was measured for 155 s. Time-course traces represents means ± se from three to five independent trials, with n = 13 to 45 individual root tips averaged per data point. E, Time-course data were analyzed for area under the response curve, baseline subtracted, with each dot representing an individual data point (see Supplemental Fig. S1 for details). The middle line in the box plot denotes the median. ANOVA with posthoc Tukey’s test was used to assess statistical differences; different lowercase letters indicate groups of significant statistical difference (P < 0.05), and the same letters indicate no statistical significance (P > 0.05).

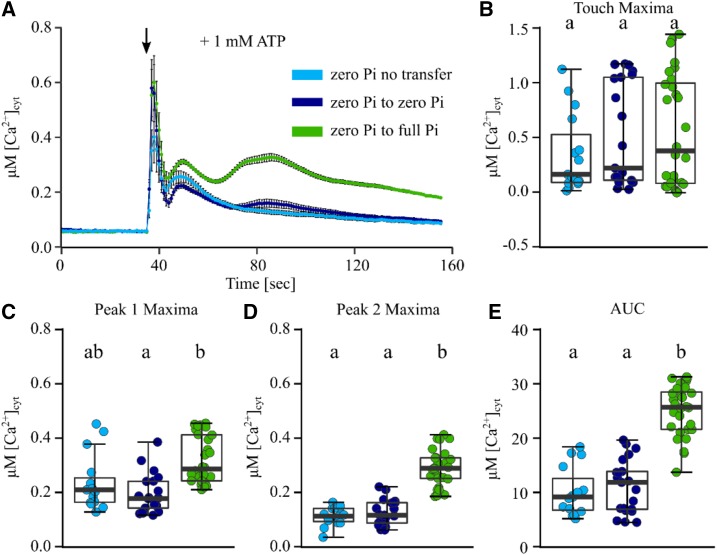

To test if the dampened and altered [Ca2+]cyt response of Pi-starved root tips could be rescued by Pi resupply or was irreversibly lost, we grew seedlings on zero Pi medium until the altered [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP would have manifested (day 8). On day 8, seedlings were (1) not transferred, (2) transferred to zero Pi growth medium (representing a transfer control), or (3) transferred to full Pi growth medium and grown for another 2 d. Pi-starved root tips (both not transferred and transferred to zero Pi) showed a dampened [Ca2+]cyt response to 1 mM eATP, with peak 2 being mostly absent. In contrast, seedlings that had been resupplied with Pi (zero Pi-to-full Pi transfer) showed a clear multiphasic [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP (Fig. 6A). Resupply of Pi significantly rescued the amplitude of peak 1 and peak 2 as well as the overall response magnitude (Fig. 6, C–E).

Figure 6.

Resupply of Pi to Pi-starved seedlings rescues the dampened root tip [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP. Arabidopsis Col-0 expressing aequorin was grown on zero Pi for 8 d, when plants were (1) not transferred (zero Pi no transfer), (2) transferred to zero Pi growth medium (zero Pi to zero Pi), or (3) transferred to full Pi growth medium (zero Pi to full Pi). After 2 d, individual excised root tips (1 cm) were challenged with treatments applied at 35 s (black arrow), and [Ca2+]cyt was measured for 155 s. A, Application of 1 mM ATP. Time-course traces represents means ± se from three independent trials, with n = 15 to 28 individual root tips averaged per data point. B to E, Time-course data were analyzed for touch maxima (B), peak 1 maxima (C), peak 2 maxima (D), and area under the response curve (AUC; E), all baseline subtracted, with each dot representing an individual data point (see Supplemental Fig. S1 for details). The middle line in the box plot denotes the median. ANOVA with posthoc Tukey’s test was used to assess statistical differences; different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

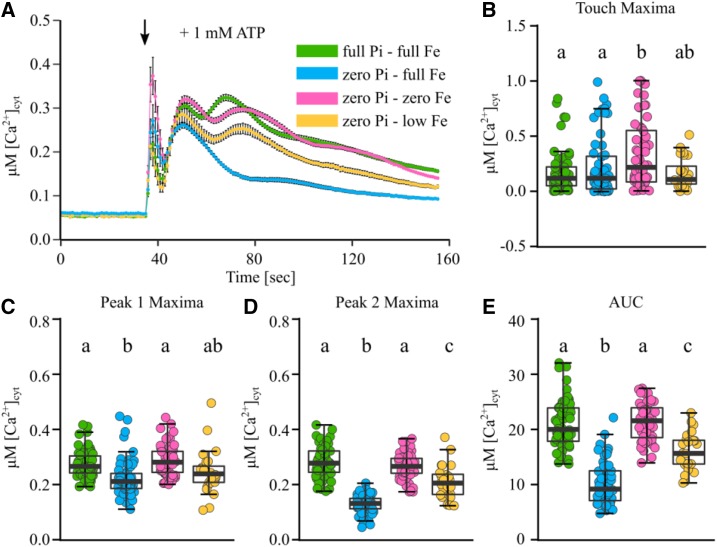

Fe Exclusion Restores the eATP-Induced [Ca2+]cyt Signature in Pi-Starved Root Tips

Pi starvation causes Fe accumulation in Arabidopsis root tips, and exclusion of Fe from the growth medium (as well as Pi) restores primary root growth (Svistoonoff et al., 2007; Ward et al., 2008; Ticconi et al., 2009; Müller et al., 2015; Balzergue et al., 2017). To test if Fe availability influences the Pi starvation effect on the eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt signature, we again grew aequorin-expressing plants on varied Pi levels (full Pi, 0.625 mM Pi; zero Pi, 0 mM Pi) while additionally varying Fe levels (full Fe, 50 µM Fe; low Fe, 10 µM Fe; zero Fe, 0 µM Fe). As expected, Fe exclusion in a zero Pi background rescued primary root growth (Supplemental Table S1). Strikingly, this growth condition (zero Pi-zero Fe) also rescued the altered root tip [Ca2+]cyt response to 1 mM eATP induced by Pi starvation alone (zero Pi-full Fe; Fig. 7A). Zero Pi-zero Fe-grown roots supported an eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt signature similar to those grown in nutrient-replete (full Pi-full Fe) conditions (Fig. 7, B–E).

Figure 7.

Fe levels modify the [Ca2+]cyt response of Pi-starved root apices to eATP. Arabidopsis Col-0 aequorin-expressing seedlings were grown on standard one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) growth medium, full Pi-full Fe (green trace), zero Pi-full Fe (blue trace), zero Pi-low Fe (pink trace), or zero Pi-zero Fe (orange trace). Excised root apices (1 cm) of 11-d-old seedlings were challenged with treatments applied at 35 s (black arrow), and [Ca2+]cyt was measured for 155 s. A, Application of 1 mM eATP. Time-course traces represent means ± se from three to six independent trials, with n = 24 to 61 individual root tips averaged per data point. B to E, Time-course data were analyzed for touch maxima (B), peak 1 maxima (C), peak 2 maxima (D), and area under the response curve (AUC; E), all baseline subtracted, with each dot representing an individual data point (see Supplemental Fig. S1 for details). The middle line in the box plot denotes the median. ANOVA with posthoc Tukey’s test was used to assess statistical differences; different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

An intermediate Fe level in a Pi-deplete background (zero Pi-low Fe) led to an intermediate [Ca2+]cyt response to 1 mM eATP for all parameters quantified (touch response [Fig. 7B], peak 1 maxima [Fig. 7C], peak 2 maxima [Fig. 7D], and area under the response curve [Fig. 7E]). This was particularly interesting, as zero Pi-low Fe-grown plants had longer root lengths than full Pi-full Fe-grown plants (Supplemental Table S1), indicating that long primary roots alone could not explain the rescued, altered [Ca2+]cyt signature. As a test of Fe specificity, copper (also a micronutrient transition metal) was excluded from the zero Pi growth medium. This treatment rescued neither primary root growth nor the eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt signature (Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Fig. S9).

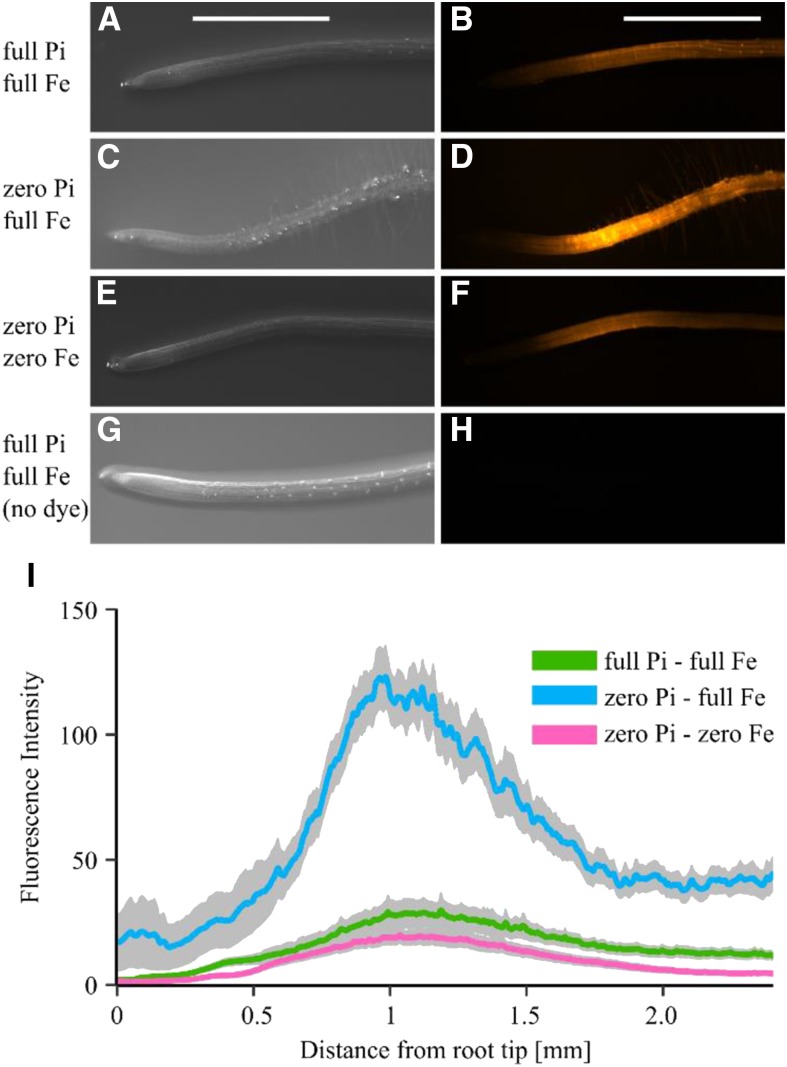

Pi and Fe Availability Influences Root Cellular ROS Level

Pi-dependent Fe accumulation has been linked to hotspots of ROS (Müller et al., 2015; Balzergue et al., 2017), implying a link between cellular redox status and aberrant [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP of Pi-starved root tips. Using the fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; which reports intracellular ROS), nutrient-replete roots showed low intracellular ROS levels along the root tip (Fig. 8, A and B). In Pi-starved root tips, we observed overall higher ROS levels, with a particular ROS hotspot localized at approximately 1 mm from the root apex (Fig. 8, C, D, and blue trace in I). Excluding Fe (in zero Pi background) reversed the higher ROS load back to nutrient-replete low ROS levels (Fig. 8, E and F). Thus, root tips sustaining a low ROS load qualitatively correlated with root tips capable of producing a multiphasic [Ca2+]cyt response to 1 mM eATP (compare with Fig. 7). Root tips showing a high ROS load correlated with root tips exhibiting a much dampened [Ca2+]cyt response to 1 mM eATP.

Figure 8.

Intracellular ROS are modified by Pi and Fe availability and influence root [Ca2+]cyt response to eATP. A to H, Ten- to 11-d-old Arabidopsis Col-0 grown on full Pi-full Fe (A and B), zero Pi-full Fe (C and D), and zero Pi-zero Fe (E and F) were stained for intracellular ROS using 20 µM CM-H2DCFDA. G and H represent the nonstained control root. A, C, E, and G, Representative bright-field images. B, D, F, and H, Representative false-colored fluorescence images. Bars = 1 mm. I, Fluorescence intensity was quantified, background subtracted, and averaged along the root length. Mean values (colored lines) ± se (gray shading) are shown. Data are from three independent trials, with n = 14 to 16 roots analyzed per growth condition.

DISCUSSION

[Ca2+]cyt is a seemingly ubiquitous second messenger in plant abiotic stress responses, with roots responding to such stresses with cell-specific Ca2+ signatures (Kiegle et al., 2000; Martí et al., 2013; Wilkins et al., 2016). Few studies have addressed the impact of nutrient status on Ca2+ signatures (Koshiba et al., 2010; Quiles-Pando et al., 2013). Here, we show that Pi but not N starvation could significantly affect the root tip [Ca2+]cyt response to a range of acute abiotic stressors and intermediate signaling agents (extracellular purine nucleotides and H2O2). Pi and Ca2+ have a particularly interesting relationship, as they can form undissociated complexes (Cole et al., 1953; Verkhratsky and Parpura, 2014; Edel and Kudla, 2015). In animals, Ca2+-Pi complexes play significant structural roles (Plattner and Verkhratsky, 2015), but in plants, these have only recently been discovered in trichomes of a variety of plant species, including Arabidopsis (Ensikat et al., 2016; Mustafa et al., 2018; Weigend et al., 2018). Pi and Ca2+ have even been shown to be stored in different plant cell types, presumably to avoid complexation (Conn and Gilliham, 2010). Cellular Pi levels have favored the evolution of a highly efficient and regulated Ca2+ flux apparatus to maintain low [Ca2+]cyt and prevent cytotoxicity (Verkhratsky and Parpura, 2014; Edel and Kudla, 2015). While Pi deficiency causes lower cellular and cytosolic Pi levels (Duff et al., 1989; Pratt et al., 2009), our results here show that [Ca2+]cyt signatures still proceed but in altered forms.

The impact of Pi depletion on the eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt signature was evident in 6-d-old root tips, at a stage where a Pi-dependent inhibition of primary root growth was not yet detectable. This suggests that changes in Ca2+ transport and possibly signaling systems are an early consequence of Pi deprivation. The observed dampening of [Ca2+]cyt signatures under Pi deprivation may have several causes. Pi deficiency causes remodeling of membranes such that phospholipids are replaced by glycolipids and sulfolipids (Andersson et al., 2005; Tjellström et al., 2010; Nakamura, 2013; Okazaki et al., 2013), which can be envisaged to have an impact on membrane-based signaling. Additionally, many studies have reported the effect of Pi starvation on gene expression and protein composition (Misson et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2011; Lan et al., 2012; Kellermeier et al., 2014; Hoehenwarter et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). However, these studies do not report an enrichment of (down-regulated) Ca2+-associated transport and signaling components to help explain dampening of the [Ca2+]cyt signature. As phosphorylated metabolites decrease and phosphorylation patterns reportedly change under Pi starvation (Duan et al., 2013; Pant et al., 2015), it could be envisaged that posttranslational modifications and an altered physicochemical cellular environment strongly affect the activity of the channels involved in generating the signatures.

Therefore, it is likely that as Pi starvation advances, there is a progressive remodeling of Ca2+ signaling machinery, affecting the transporters engaged in generating [Ca2+]cyt signatures. Our results show that this is not a determinate effect but is reversible by Pi resupply. These findings have implications for the downstream signaling events and responses, which may change under Pi deprivation. For example, Pi deprivation dampened the mechano-induced [Ca2+]cyt signature, which may have consequences for root penetration of Pi-deplete compacted soil. It also dampened the NaCl-induced [Ca2+]cyt signature, which may have consequences for regulation of the Ca2+-dependent SOS pathway (Quintero et al., 2011; Manishankar et al., 2018) and the observation that Pi starvation alleviated the inhibitory effect of low salt concentrations on root growth (Kawa et al., 2016).

The extracellular purine nucleotides ATP and ADP induce root [Ca2+]cyt increases, potentially for regulation of growth, stress responses, and defense (Demidchik et al., 2003, 2009; Rincón-Zachary et al., 2010; Tanaka et al., 2010a; Dark et al., 2011; Loro et al., 2012, 2016; Choi et al., 2014). In common with root [Ca2+]cyt imaging reports (Loro et al., 2012, 2016; Waadt et al., 2017), eATP was used here as a reliable stimulus of a robust [Ca2+]cyt signature as well as an agent of root signal transduction. Under Pi-replete conditions, the temporal biphasic eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt response found using aequorin mapped well to a spatial biphasic response found using YC3.6 as well as agreed with what has recently been reported using a range of other [Ca2+]cyt reporters (Waadt et al., 2017). This spatiotemporal pattern has been hypothesized to constitute a Ca2+ wave, propagating from the meristematic zone toward the elongation zone and into the mature zone (Rincón-Zachary et al., 2010; Loro et al., 2012; Costa et al., 2013).

The spatial resolution afforded by YC3.6 revealed that while Pi starvation had no effect on the eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase at the apex (Fig. 4, G and H), it caused the progressive diminution of the signal in increasingly distal regions in the mature zone (Fig. 4, A–F). Root accumulation of intracellular ROS under Pi deficiency was linked to Fe availability (Fig. 8), consistent with previous reports (Müller et al., 2015; Balzergue et al., 2017). Fe depletion under Pi starvation not only lowered ROS accumulation to that found under nutrient-replete conditions but also restored the second peak of the biphasic eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt signature (with good spatial coincidence of both phenomena). It is therefore reasonable to conclude that under Pi deprivation alone, aberrant Fe accumulation leads to intracellular ROS accumulation and that the greater oxidative state of that region helps suppress the second eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase. Abiotic stress has been shown previously to cause an increase in root ROS accumulation, with NADPH oxidases implicated in their generation (Foreman et al., 2003; Demidchik et al., 2009). However, the activity of NADPH oxidases is usually linked to amplification of a [Ca2+]cyt increase through activation of Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane (Foreman et al., 2003; Demidchik et al., 2009; Laohavisit et al., 2012; Demidchik, 2018). This is seemingly at odds with the loss of the second eATP-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase under Pi starvation, and the paradigm of the ROS/Ca2+ hub in signaling may not hold under Pi deprivation or in general conditions of high baseline ROS. The origin of the intracellular ROS under Pi deprivation may well include leakage from mitochondria, which increase their ROS production under stress (Gleason et al., 2011). It is feasible that the restoration of normal ROS levels with growth on zero Pi and zero Fe medium reflects the impaired mitochondrial function that occurs on chronic deprivation of Fe (Vigani and Briat, 2016), possibly leading to lower ROS production.

Overall, our results reveal how nutritional status adds another layer of complexity to Ca2+ signaling, allowing plants to integrate various cues such as nutritional status and environmental changes. While [Ca2+]cyt does not appear to be a second messenger in the sensing of Pi in either Pi-replete Arabidopsis roots (Demidchik et al., 2003) or Pi-starved roots (this study), its use is altered when Pi supply is limited. In addition to elucidating the mechanistic basis of these altered signatures in response to abiotic stress and determining downstream consequences for signaling, it is also now appropriate to investigate the impact of nutritional status on Ca2+ signaling in biotic interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

All plant material used was in the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Col-0 background, stably transformed with constitutively expressed cytosolic (apo)aequorin (pMAQ2; Knight et al., 1991) or the cytosolic sensor NES-YC3.6 (Krebs et al., 2012). Surface-sterilized seeds were sown aseptically on one-half-strength MS growth medium including vitamins (Duchefa), with pH adjusted to 5.6 using KOH, and solidified using 0.8% (w/v) agar (Bacto agar; BD Biosciences). Plates (12 cm × 12 cm; Greiner Bio-One) were sealed using micropore tape (3M) to allow for gas exchange. All seeds were stratified at 4°C and in darkness for 2 to 3 d prior to placing plates vertically into long-day conditions (16 h of light/8 h of dark) in a growth chamber with 78 µmol m−2 s−1 light intensity at 23°C (CLF Plant Climatics).

Standard one-half-strength MS comprised the full Pi and full N growth conditions. A custom-made MS medium without Pi was used for zero Pi conditions (Duchefa; DU1072) or without N for zero N conditions (PhytoTechnology Laboratories; M531). KCl was used to substitute for missing K+ whenever Pi (KH2PO4) or N (KNO3) was excluded. As the N-free medium was not available including vitamins, MS vitamin × 1,000 stock solution (Sigma-Aldrich; M7150) was added to zero N medium to the same final concentration. For all growth conditions requiring modified Fe or copper content, one-half-strength MS medium was prepared from stock solutions and vitamins were supplied from the MS vitamin × 1,000 stock. For transfer experiments, 8-d-old seedlings were transferred to fresh growth medium plates, containing full/zero Pi growth medium (as described in the text), and grown for an additional 2 d.

Quantification of Primary Root Length

Plates containing seedlings were scanned using a Perfection V300 Photo scanner (Epson) with 300-dpi resolution, saving the images in tiff format. The software ImageJ (Abràmoff et al., 2004) and plugin NeuronJ (Meijering et al., 2004) were used to trace primary root lengths.

Aequorin-Based [Ca2+]cyt Measurements

Nutrient growth conditions were maintained throughout the experiments (i.e. all incubation and treatment solutions were prepared in the respective liquid one-half-strength MS medium, including 1.175 mM MES, adjusted to pH 5.6 using Tris). Excised primary root tips of 11-d-old Arabidopsis expressing (apo)aequorin were used for luminescence-based quantification of [Ca2+]cyt dynamics, unless stated otherwise. Reconstitution of aequorin with coelenterazine in vivo was modified after Knight et al. (1997b). In short, an excised tip was placed individually in a well of a white 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One), incubated in 10 µM coelenterazine (NanoLight Technology) overnight, in darkness and at room temperature. A FLUOstar OPTIMA plate reader (BMG Labtech) was used to record baseline luminescence for 35 s, before injecting 100 µL of different treatment solutions with an injection speed of 150 µL s−1. Changes in luminescence signal were monitored for 120 s, before injecting 100 µL of discharge solution (final concentration, 10% [v/v] ethanol and 1 M CaCl2) and monitoring for another 45 s. Concentrations of [Ca2+]cyt were calculated as described (Knight et al., 1997b). Treatments included the following: ATP disodium salt trihydrate (ATP; Melford), ADP disodium salt dehydrate (ADP; Melford), nonhydrolyzable ATP-analog γ-ATP (Sigma), phosphoric acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific), NaCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific), osmotic control for NaCl treatments, d-sorbitol (Sigma-Aldrich), and H2O2 (Sigma). The accompanying ions (Na+ for ATP and ADP; Li+ for γ-ATP) were previously shown in our laboratory not to confound the response (Demidchik et al., 2009). Test treatments were pH adjusted to 5.6 using Tris and prepared at double strength, as in the well; a 1:2 dilution led to the desired final concentration. A Vapro5520 osmometer (Wescor) was used to check the osmolality of the NaCl and d-sorbitol treatment solutions.

Ratiometric [Ca2+]cyt Measurements

Ten-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings expressing NES-YC3.6 were mounted into a custom-built superfusion chamber (Behera and Kudla, 2013), stabilized with wetted cotton wool, and continuously superfused with imaging solution (IS; 5 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM MES, set to pH 5.8 using Tris; Loro et al., 2016) using an EconoPump system (Bio-Rad) with a tube diameter of 0.8 mm and a speed of 0.9 mL min−1. Seedlings were left to acclimatize to constant superfusion for 10 to 15 min before starting an experiment. At the start of an experiment, seedlings were imaged for 2 min while superfusing IS. Extracellular ATP treatment (1 mM ATP, in IS background, pH 5.8) was then superfused over the roots for 3 min before changing back to IS without ATP. Images were captured using a Ti-E wide-field inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon) with a Nikon Plan Fluor 4× 0.13 dry objective. The samples were excited at 440 nm using a Prior Lumen 200 PRO fluorescent light source (Prior Scientific). Images were collected with an ORCA-D2 Dual CCD camera (Hamamatsu) every 5 s for up to 30 min. NIS Elements AR 4.0 software (Nikon) was used to control the microscope, light source, and camera. ImageJ Fiji software was used to process the cpVenus and CFP fluorescence intensities. Using the Roi Manager tool, each root sample was individually fitted with comparable ROIs. The z axis profiles were plotted for each channel, individually background subtracted, and used to calculate FRET raw ratios (cpVenus/CFP). Normalization of data was carried out by taking into account differences in prestimulus baseline (ΔR/R0 = R – R0/R0, with R – cpVenus/CFP ratio, R0 – averaged cpVenus/CFP prestimulus baseline ratio, after Loro et al., 2016).

ROS Imaging

The membrane-permeable dye CM-H2DCFDA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used at a final concentration of 20 µM, in assay medium (0.1 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 1.175 mM MES, set to pH 6 using Tris; adapted from Foreman et al., 2003). Ten- to 11-d-old seedlings were incubated for 1 h (dark, 4°C), gently washed in fresh assay medium without dye, and placed on plates containing growth medium maintaining previous growth conditions for 1 h (light, room temperature) to acclimatize, before imaging primary root tips with a stereomicroscope, M205 FA (Leica), with a DFC365FX camera (Leica) and a Sola SE365 light source (Lumencor). Excitation at 470/40 nm was used and a GFP-ET filter collected emission at 525/50 nm, with a 400-ms exposure time, 70% light intensity, and a gain of 2 and 50× magnification. LAS X software (Leica) was used to control the microscope, light source, and camera. Image analysis was done using Fiji ImageJ software, tracing each root using the line tool (line width, 10) in combination with the plot profile function, which reports signal intensity along the root (Reyt et al., 2015). For each root, three lines were drawn (from root apex shootward through the center of the root, from root apex shootward along the upper side of the root, and from root apex shootward along the lower part of the root), and the intensity profiles were averaged per root (Reyt et al., 2015).

Data Analysis

Data analysis and all statistical tests were performed using the open-source software R (www.r-project.org; version 3.5.1) in an R studio environment. The package MESS was used to calculate area under the response curve. ANOVA and Tukey’s honestly significant difference posthoc test were employed to determine differences among the groups. A 95% family-wise confidence level was applied.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers M11394.1 (aequorin) and AB178712 (YC3.6).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Schematic representation of aequorin-based [Ca2+]cyt time-course analyses.

Supplemental Figure S2. The [Ca2+]cyt response of N-starved root tips to salt and osmotic stress.

Supplemental Figure S3. The [Ca2+]cyt response of Pi-starved root tips to mechanical stimulation and a Pi source.

Supplemental Figure S4. The [Ca2+]cyt response of Pi-starved root tips to extracellular ADP.

Supplemental Figure S5. The [Ca2+]cyt response of Pi-starved root tips to a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog.

Supplemental Figure S6. The [Ca2+]cyt response of Pi-starved root tips to oxidative stress.

Supplemental Figure S7. The [Ca2+]cyt response of N-starved root tips to eATP.

Supplemental Figure S8. The [Ca2+]cyt response of N-starved root tips to oxidative stress.

Supplemental Figure S9. The [Ca2+]cyt response of copper- and Pi-starved root tips to eATP.

Supplemental Table S1. Mean primary root lengths of Arabidopsis plants used in this study.

Supplemental Movie S1. Ratiometric false-color movie from a representative time series of a Pi-replete Col-0 root expressing NES-YC3.6, response to 1 mM eATP.

Supplemental Movie S2. Ratiometric false-color movie from a representative time series of a Pi-starved Col-0 root expressing NES-YC3.6, response to 1 mM eATP.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adeeba Dark (University of Cambridge) and Laura Luoni (University of Milan) for technical support and training and Alex Webb (University of Cambridge) for useful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Doctoral Training Programme (BB/J014540/1) and the Broodbank Trust, the Ministero dell’Istruzione dell’Università e della Ricerca, Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base (FIRB 2010 RBFR10S1LJ_001), a University of Milan Transition Grant (Horizon 2020, Fondo di Ricerca Linea 1A Progetto Unimi Partenariati H2020), and Piano di Sviluppo di Ateneo 2016, 2017.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Abel S. (2017) Phosphate scouting by root tips. Curr Opin Plant Biol 39: 168–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abràmoff MD, Hospitals I, Magalhães PJ, Abràmoff M (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton Int 11: 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- Andersson MX, Larsson KE, Tjellström H, Liljenberg C, Sandelius AS (2005) Phosphate-limited oat: The plasma membrane and the tonoplast as major targets for phospholipid-to-glycolipid replacement and stimulation of phospholipases in the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 280: 27578–27586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzergue C, Dartevelle T, Godon C, Laugier E, Meisrimler C, Teulon JM, Creff A, Bissler M, Brouchoud C, Hagège A, et al. (2017) Low phosphate activates STOP1-ALMT1 to rapidly inhibit root cell elongation. Nat Commun 8: 15300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera S, Kudla J (2013) High-resolution imaging of cytoplasmic Ca2+ dynamics in Arabidopsis roots. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2013: 670–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera S, Long Y, Schmitz-Thom I, Wang XP, Zhang C, Li H, Steinhorst L, Manishankar P, Ren XL, Offenborn JN, et al. (2017) Two spatially and temporally distinct Ca2+ signals convey Arabidopsis thaliana responses to K+ deficiency. New Phytol 213: 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera S, Zhaolong X, Luoni L, Bonza MC, Doccula FG, De Michelis MI, Morris RJ, Schwarzländer M, Costa A (2018) Cellular Ca2+ signals generate defined pH signatures in plants. Plant Cell 30: 2704–2719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonza MC, Loro G, Behera S, Wong A, Kudla J, Costa A (2013) Analyses of Ca2+ accumulation and dynamics in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis root cells using a genetically encoded Cameleon sensor. Plant Physiol 163: 1230–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Cao Y, Li H, Kim D, Ahsan N, Thelen J, Stacey G (2017) Extracellular ATP elicits DORN1-mediated RBOHD phosphorylation to regulate stomatal aperture. Nat Commun 8: 2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien PS, Chiang CP, Leong SJ, Chiou TJ (2018) Sensing and signaling of phosphate starvation: From local to long distance. Plant Cell Physiol 59: 1714–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou TJ, Lin SI (2011) Signaling network in sensing phosphate availability in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 62: 185–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Tanaka K, Cao Y, Qi Y, Qiu J, Liang Y, Lee SY, Stacey G (2014) Identification of a plant receptor for extracellular ATP. Science 343: 290–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole CV, Olsen SR, Scott CO (1953) The nature of phosphate sorption by calcium carbonate. Proc Soil Sci Soc Am 135: 352–356 [Google Scholar]

- Conn S, Gilliham M (2010) Comparative physiology of elemental distributions in plants. Ann Bot 105: 1081–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Candeo A, Fieramonti L, Valentini G, Bassi A (2013) Calcium dynamics in root cells of Arabidopsis thaliana visualized with selective plane illumination microscopy. PLoS ONE 8: e75646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dark A, Demidchik V, Richards SL, Shabala S, Davies JM (2011) Release of extracellular purines from plant roots and effect on ion fluxes. Plant Signal Behav 6: 1855–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V. (2018) ROS-activated ion channels in plants: Biophysical characteristics, physiological functions and molecular nature. Int J Mol Sci 19: 17–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V, Nichols C, Oliynyk M, Dark A, Glover BJ, Davies JM (2003) Is ATP a signaling agent in plants? Plant Physiol 133: 456–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V, Shabala SN, Davies JM (2007) Spatial variation in H2O2 response of Arabidopsis thaliana root epidermal Ca2+ flux and plasma membrane Ca2+ channels. Plant J 49: 377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V, Shang Z, Shin R, Thompson E, Rubio L, Laohavisit A, Mortimer JC, Chivasa S, Slabas AR, Glover BJ, et al. (2009) Plant extracellular ATP signalling by plasma membrane NADPH oxidase and Ca2+ channels. Plant J 58: 903–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V, Shang Z, Shin R, Colaço R, Laohavisit A, Shabala S, Davies JM (2011) Receptor-like activity evoked by extracellular ADP in Arabidopsis root epidermal plasma membrane. Plant Physiol 156: 1375–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan G, Walther D, Schulze WX (2013) Reconstruction and analysis of nutrient-induced phosphorylation networks in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci 4: 540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff SM, Moorhead GB, Lefebvre DD, Plaxton WC (1989) Phosphate starvation inducible ‘bypasses’ of adenylate and phosphate dependent glycolytic enzymes in Brassica nigra suspension cells. Plant Physiol 90: 1275–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edel KH, Kudla J (2015) Increasing complexity and versatility: How the calcium signaling toolkit was shaped during plant land colonization. Cell Calcium 57: 231–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensikat HJ, Geisler T, Weigend M (2016) A first report of hydroxylated apatite as structural biomineral in Loasaceae: Plants’ teeth against herbivores. Sci Rep 6: 26073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman J, Demidchik V, Bothwell JHF, Mylona P, Miedema H, Torres MA, Linstead P, Costa S, Brownlee C, Jones JDG, et al. (2003) Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature 422: 442–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason C, Huang S, Thatcher LF, Foley RC, Anderson CR, Carroll AJ, Millar AH, Singh KB (2011) Mitochondrial complex II has a key role in mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species influence on plant stress gene regulation and defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 10768–10773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber BD, Giehl RFH, Friedel S, von Wirén N (2013) Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiol 163: 161–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehenwarter W, Mönchgesang S, Neumann S, Majovsky P, Abel S, Müller J (2016) Comparative expression profiling reveals a role of the root apoplast in local phosphate response. BMC Plant Biol 16: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawa D, Julkowska M, Montero Sommerfeld H, ter Horst A, Haring MA, Testerink C (2016) Phosphate-dependent root system architecture responses to salt stress. Plant Physiol 172: 690–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermeier F, Armengaud P, Seditas TJ, Danku J, Salt DE, Amtmann A (2014) Analysis of the root system architecture of Arabidopsis provides a quantitative readout of crosstalk between nutritional signals. Plant Cell 26: 1480–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiegle E, Moore CA, Haseloff J, Tester MA, Knight MR (2000) Cell-type-specific calcium responses to drought, salt and cold in the Arabidopsis root. Plant J 23: 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Sivaguru M, Stacey G (2006) Extracellular ATP in plants: Visualization, localization, and analysis of physiological significance in growth and signaling. Plant Physiol 142: 984–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight H, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR (1997a) Calcium signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana responding to drought and salinity. Plant J 12: 1067–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight H, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR (1997b) Recombinant aequorin methods for measurement of intracellular calcium in plants. In Gelvin SB, Schilperoort RA, eds, Plant Molecular Biology Manual. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 1–22 [Google Scholar]

- Knight MR, Campbell AK, Smith SM, Trewavas AJ (1991) Transgenic plant aequorin reports the effects of touch and cold-shock and elicitors on cytoplasmic calcium. Nature 352: 524–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MR, Smith SM, Trewavas AJ (1992) Wind-induced plant motion immediately increases cytosolic calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 4967–4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba T, Kobayashi M, Ishihara A, Matoh T (2010) Boron nutrition of cultured tobacco BY-2 cells. VI. Calcium is involved in early responses to boron deprivation. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 323–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs M, Held K, Binder A, Hashimoto K, Den Herder G, Parniske M, Kudla J, Schumacher K (2012) FRET-based genetically encoded sensors allow high-resolution live cell imaging of Ca2+ dynamics. Plant J 69: 181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan P, Li W, Schmidt W (2012) Complementary proteome and transcriptome profiling in phosphate-deficient Arabidopsis roots reveals multiple levels of gene regulation. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: 1156–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laohavisit A, Shang Z, Rubio L, Cuin TA, Véry AA, Wang A, Mortimer JC, MacPherson N, Coxon KM, Battey NH, et al. (2012) Arabidopsis annexin1 mediates the radical-activated plasma membrane Ca2+- and K+-permeable conductance in root cells. Plant Cell 24: 1522–1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laohavisit A, Richards SL, Shabala L, Chen C, Colaço RDDR, Swarbreck SM, Shaw E, Dark A, Shabala S, Shang Z, et al. (2013) Salinity-induced calcium signaling and root adaptation in Arabidopsis require the calcium regulatory protein annexin1. Plant Physiol 163: 253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzoni G, Liu J, Knight MR (2018) Predicting plant immunity gene expression by identifying the decoding mechanism of calcium signatures. New Phytol 217: 1598–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WD, Liao YY, Yang TJW, Pan CY, Buckhout TJ, Schmidt W (2011) Coexpression-based clustering of Arabidopsis root genes predicts functional modules in early phosphate deficiency signaling. Plant Physiol 155: 1383–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn J, Ren M, Berkowitz O, Ding W, van der Merwe MJ, Whelan J, Jost R (2017) Root cell-specific regulators of phosphate-dependent growth. Plant Physiol 174: 1969–1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Whalley HJ, Knight MR (2015) Combining modelling and experimental approaches to explain how calcium signatures are decoded by calmodulin-binding transcription activators (CAMTAs) to produce specific gene expression responses. New Phytol 208: 174–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu KH, Niu Y, Konishi M, Wu Y, Du H, Sun Chung H, Li L, Boudsocq M, McCormack M, Maekawa S, et al. (2017) Discovery of nitrate-CPK-NLP signalling in central nutrient-growth networks. Nature 545: 311–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loro G, Drago I, Pozzan T, Schiavo FL, Zottini M, Costa A (2012) Targeting of Cameleons to various subcellular compartments reveals a strict cytoplasmic/mitochondrial Ca2+ handling relationship in plant cells. Plant J 71: 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loro G, Wagner S, Doccula FG, Behera S, Weinl S, Kudla J, Schwarzländer M, Costa A, Zottini M (2016) Chloroplast-specific in vivo Ca2+ imaging using Yellow Cameleon fluorescent protein sensors reveals organelle-autonomous Ca2+ signatures in the stroma. Plant Physiol 171: 2317–2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manishankar P, Wang N, Köster P, Alatar AA, Kudla J (2018) Calcium signaling during salt stress and in the regulation of ion homeostasis. J Exp Bot 61: 302–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí MC, Stancombe MA, Webb AAR (2013) Cell- and stimulus type-specific intracellular free Ca2+ signals in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 163: 625–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijering E, Jacob M, Sarria JC, Steiner P, Hirling H, Unser M (2004) Design and validation of a tool for neurite tracing and analysis in fluorescence microscopy images. Cytometry A 58: 167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misson J, Raghothama KG, Jain A, Jouhet J, Block MA, Bligny R, Ortet P, Creff A, Somerville S, Rolland N, et al. (2005) A genome-wide transcriptional analysis using Arabidopsis thaliana Affymetrix gene chips determined plant responses to phosphate deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11934–11939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen GB, Bibikova TN, Weisenseel MH, Gilroy S (2009) Ca2+ regulates reactive oxygen species production and pH during mechanosensing in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 21: 2341–2356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Toev T, Heisters M, Teller J, Moore KL, Hause G, Dinesh DC, Bürstenbinder K, Abel S (2015) Iron-dependent callose deposition adjusts root meristem maintenance to phosphate availability. Dev Cell 33: 216–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa A, Ensikat HJ, Weigend M (2018) Mineralized trichomes in Boraginales: Complex microscale heterogeneity and simple phylogenetic patterns. Ann Bot 121: 741–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y. (2013) Phosphate starvation and membrane lipid remodeling in seed plants. Prog Lipid Res 52: 43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki Y, Otsuki H, Narisawa T, Kobayashi M, Sawai S, Kamide Y, Kusano M, Aoki T, Hirai MY, Saito K (2013) A new class of plant lipid is essential for protection against phosphorus depletion. Nat Commun 4: 1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant BD, Pant P, Erban A, Huhman D, Kopka J, Scheible WR (2015) Identification of primary and secondary metabolites with phosphorus status-dependent abundance in Arabidopsis, and of the transcription factor PHR1 as a major regulator of metabolic changes during phosphorus limitation. Plant Cell Environ 38: 172–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péret B, Desnos T, Jost R, Kanno S, Berkowitz O, Nussaume L (2014) Root architecture responses: In search of phosphate. Plant Physiol 166: 1713–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner H, Verkhratsky A (2015) The ancient roots of calcium signalling evolutionary tree. Cell Calcium 57: 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxton WC, Tran HT (2011) Metabolic adaptations of phosphate-starved plants. Plant Physiol 156: 1006–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt J, Boisson AM, Gout E, Bligny R, Douce R, Aubert S (2009) Phosphate (Pi) starvation effect on the cytosolic Pi concentration and Pi exchanges across the tonoplast in plant cells: An in vivo 31P-nuclear magnetic resonance study using methylphosphonate as a Pi analog. Plant Physiol 151: 1646–1657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AH, Taylor A, Ripley SJ, Griffiths A, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR (1994) Oxidative signals in tobacco increase cytosolic calcium. Plant Cell 6: 1301–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiles-Pando C, Rexach J, Navarro-Gochicoa MT, Camacho-Cristóbal JJ, Herrera-Rodríguez MB, González-Fontes A (2013) Boron deficiency increases the levels of cytosolic Ca2+ and expression of Ca2+-related genes in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant Physiol Biochem 65: 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero FJ, Martinez-Atienza J, Villalta I, Jiang X, Kim WY, Ali Z, Fujii H, Mendoza I, Yun DJ, Zhu JK, et al. (2011) Activation of the plasma membrane Na/H antiporter Salt-Overly-Sensitive 1 (SOS1) by phosphorylation of an auto-inhibitory C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 2611–2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentel MC, Knight MR (2004) Oxidative stress-induced calcium signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 135: 1471–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyt G, Boudouf S, Boucherez J, Gaymard F, Briat JF (2015) Iron- and ferritin-dependent reactive oxygen species distribution: Impact on Arabidopsis root system architecture. Mol Plant 8: 439–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SL, Laohavisit A, Mortimer JC, Shabala L, Swarbreck SM, Shabala S, Davies JM (2014) Annexin 1 regulates the H2O2-induced calcium signature in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant J 77: 136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincón-Zachary M, Teaster ND, Sparks JA, Valster AH, Motes CM, Blancaflor EB (2010) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer-sensitized emission of yellow cameleon 3.60 reveals root zone-specific calcium signatures in Arabidopsis in response to aluminum and other trivalent cations. Plant Physiol 152: 1442–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveras E, Alvarez JM, Vidal EA, Oses C, Vega A, Gutiérrez RA (2015) The calcium ion is a second messenger in the nitrate signaling pathway of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 169: 1397–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CJ, Steinebrunner I, Wang X, Stout SC, Roux SJ (2006) Extracellular ATP induces the accumulation of superoxide via NADPH oxidases in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 140: 1222–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svistoonoff S, Creff A, Reymond M, Sigoillot-Claude C, Ricaud L, Blanchet A, Nussaume L, Desnos T (2007) Root tip contact with low-phosphate media reprograms plant root architecture. Nat Genet 39: 792–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Gilroy S, Jones AM, Stacey G (2010a) Extracellular ATP signaling in plants. Trends Cell Biol 20: 601–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Swanson SJ, Gilroy S, Stacey G (2010b) Extracellular nucleotides elicit cytosolic free calcium oscillations in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 154: 705–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang RJ, Zhao FG, Garcia VJ, Kleist TJ, Yang L, Zhang HX, Luan S (2015) Tonoplast CBL-CIPK calcium signaling network regulates magnesium homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 3134–3139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ticconi CA, Lucero RD, Sakhonwasee S, Adamson AW, Creff A, Nussaume L, Desnos T, Abel S (2009) ER-resident proteins PDR2 and LPR1 mediate the developmental response of root meristems to phosphate availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 14174–14179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjellström H, Hellgren LI, Wieslander A, Sandelius AS (2010) Lipid asymmetry in plant plasma membranes: Phosphate deficiency-induced phospholipid replacement is restricted to the cytosolic leaflet. FASEB J 24: 1128–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Parpura V (2014) Calcium signalling and calcium channels: Evolution and general principles. Eur J Pharmacol 739: 1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani G, Briat JF (2016) Impairment of respiratory chain under nutrient deficiency in plants: Does it play a role in the regulation of iron and sulfur responsive genes? Front Plant Sci 6: 1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waadt R, Krebs M, Kudla J, Schumacher K (2017) Multiparameter imaging of calcium and abscisic acid and high-resolution quantitative calcium measurements using R-GECO1-mTurquoise in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 216: 303–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Zhou X, Dong L, Guo J, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Wu L, Xu M (2018) iTRAQ-based analysis of the Arabidopsis proteome reveals insights into the potential mechanisms of anthocyanin accumulation regulation in response to phosphate deficiency. J Proteomics 184: 39–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JT, Lahner B, Yakubova E, Salt DE, Raghothama KG (2008) The effect of iron on the primary root elongation of Arabidopsis during phosphate deficiency. Plant Physiol 147: 1181–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerasinghe RR, Swanson SJ, Okada SF, Garrett MB, Kim SY, Stacey G, Boucher RC, Gilroy S, Jones AM (2009) Touch induces ATP release in Arabidopsis roots that is modulated by the heterotrimeric G-protein complex. FEBS Lett 583: 2521–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend M, Mustafa A, Ensikat HJ (2018) Calcium phosphate in plant trichomes: The overlooked biomineral. Planta 247: 277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley HJ, Knight MR (2013) Calcium signatures are decoded by plants to give specific gene responses. New Phytol 197: 690–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley HJ, Sargeant AW, Steele JFC, Lacoere T, Lamb R, Saunders NJ, Knight H, Knight MR (2011) Transcriptomic analysis reveals calcium regulation of specific promoter motifs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 4079–4095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins KA, Matthus E, Swarbreck SM, Davies JM (2016) Calcium-mediated abiotic stress signaling in roots. Front Plant Sci 7: 1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson LC, Ribrioux SP, Fitter AH, Leyser HM (2001) Phosphate availability regulates root system architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 126: 875–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]