Leaf ER bodies constitutively occur in specific epidermal cells of Arabidopsis rosette leaves and play a role in plant defense against herbivory.

Abstract

ER bodies are endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived organelles specific to the order Brassicales and are thought to function in plant defense against insects and pathogens. ER bodies are generally classified into two types: constitutive ER bodies in the epidermal cells of seedlings, and wound-inducible ER bodies in rosette leaves. Herein, we reveal a third type of ER body found in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) rosette leaves and designate them “leaf ERbodies” (L-ER bodies). L-ER bodies constitutively occurred in specific cells of the rosette leaves: marginal cells, epidermal cells covering the midrib, and giant pavement cells. The distribution of L-ER bodies was closely associated with the expression profile of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor NAI1, which is responsible for constitutive ER-body formation. L-ER bodies were seldom observed in nai1 mutant leaves, indicating that NAI1 is involved in L-ER body formation. Confocal imaging analysis revealed that L-ER bodies accumulated two types of β-glucosidases: PYK10, the constitutive ER-body β-glucosidase; and BETA-GLUCOSIDASE18 (BGLU18), the wound-inducible ER-body β-glucosidase. Combined with the absence of L-ER bodies in the bglu18 pyk10 mutant, these results indicate that BGLU18 and PYK10 are the major components of L-ER bodies. A subsequent feeding assay with the terrestrial isopod Armadillidium vulgare revealed that bglu18 pyk10 leaves were severely damaged as a result of herbivory. In addition, the bglu18 pyk10 mutant was defective in the hydrolysis of 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate These results suggest that L-ER bodies are involved in the production of defensive compound(s) from 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate that protect Arabidopsis leaves against herbivory attack.

ER bodies are endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived organelles found in the order Brassicales (Nakano et al., 2014) that are thought to play a role in plant defense (Hara-Nishimura and Matsushima, 2003). ER bodies exhibit spindle-shaped morphology and primarily accumulate β-glucosidases with ER retention signals, such as PYK10/BETA-GLUCOSIDASE23 (BGLU23; Matsushima et al., 2003a). ER bodies have been observed in the epidermal cells of the cotyledons, hypocotyls, and roots of whole Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seedlings (Matsushima et al., 2002). Recently, PYK10 was shown to exhibit myrosinase activity toward indole-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate (I3G; Nakano et al., 2017). Glucosinolates are a group of secondary metabolites specific to the order Brassicales that are degraded to toxic compounds such as isothiocyanates and nitriles by enzymes called “myrosinases” (Halkier and Gershenzon, 2006). Glucosinolates and myrosinases are accumulated separately in intact tissues, but combine when these tissues are damaged as a result of herbivory, thus allowing the hydrolysis reaction to occur (Bones and Rossiter, 1996; Rask et al., 2000). This reaction, called the “mustard oil bomb,” is an effective defense against various herbivores, including insects (Borek et al., 1997; Beekwilder et al., 2008), nematodes (Buskov et al., 2002; Lazzeri et al., 2004), and mollusks (Noret et al., 2005; Falk et al., 2014).

In Arabidopsis rosette leaves, large amounts of myrosinases, namely THIOGLUCOSIDE GLUCOHYDROLASE1 (TGG1) and TGG2, are accumulated in the vacuoles of myrosin cells (Ueda et al., 2006). Therefore, myrosin cells are thought to be the primary reservoir for myrosinases of the glucosinolate-myrosinase defense system in Arabidopsis leaves. However, previous studies have reported that ER bodies are induced by wound stress or the treatment of methyl jasmonate in Arabidopsis rosette leaves (Matsushima et al., 2002, 2003a). These ER bodies are called “inducible ER bodies” to distinguish them from the constitutive ER bodies found in seedlings. Inducible ER bodies accumulate BGLU18, a β-glucosidase with the ER retention signal Arg-Glu-Glu-Leu (Ogasawara et al., 2009). It is suggested that myrosin cells and ER bodies, respectively, accumulate two distinct classes of myrosinases, TGGs and BGLUs, which have independently evolved to have myrosinase activity (Nakano et al., 2017). However, the functional differences between myrosin cells and ER bodies in defense against herbivory are not well understood.

Several factors involved in ER-body formation have been identified in Arabidopsis; the basic helix-loop-helix–type transcription factor NAI1 regulates the expression of PYK10 and is required for ER-body formation (Matsushima et al., 2003b, 2004). NAI1 also regulates the expression of NAI2, MEMBRANE PROTEIN OF ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM BODY1 (MEB1), and MEB2. NAI2 is responsible for the accumulation of PYK10 in ER bodies (Yamada et al., 2008), whereas MEB1 and MEB2 are ER-body–specific integral membrane proteins (Yamada et al., 2013).

In this study, we identified and characterized a novel type of ER body that exists constitutively in Arabidopsis rosette leaves. We refer to them as “leaf ER bodies” (L-ER bodies) to distinguish them from constitutive and inducible ER bodies. Interestingly, L-ER bodies display properties similar to both constitutive ER bodies and inducible ER bodies in terms of the types of β-glucosidases they accumulate, their transcriptional regulatory system, and the mechanism of their formation. Thus, L-ER bodies are considered the third type of ER body in Arabidopsis. The distribution pattern of L-ER bodies in leaves was different from that of myrosin cells. Dual-choice feeding assays revealed that L-ER bodies played a role in decreasing herbivory damage by Armadillidium vulgare. Overall, our results indicate that L-ER bodies play an important role in the defense against herbivory in Arabidopsis leaves.

RESULTS

Identification of L-ER Bodies in Arabidopsis Rosette Leaves

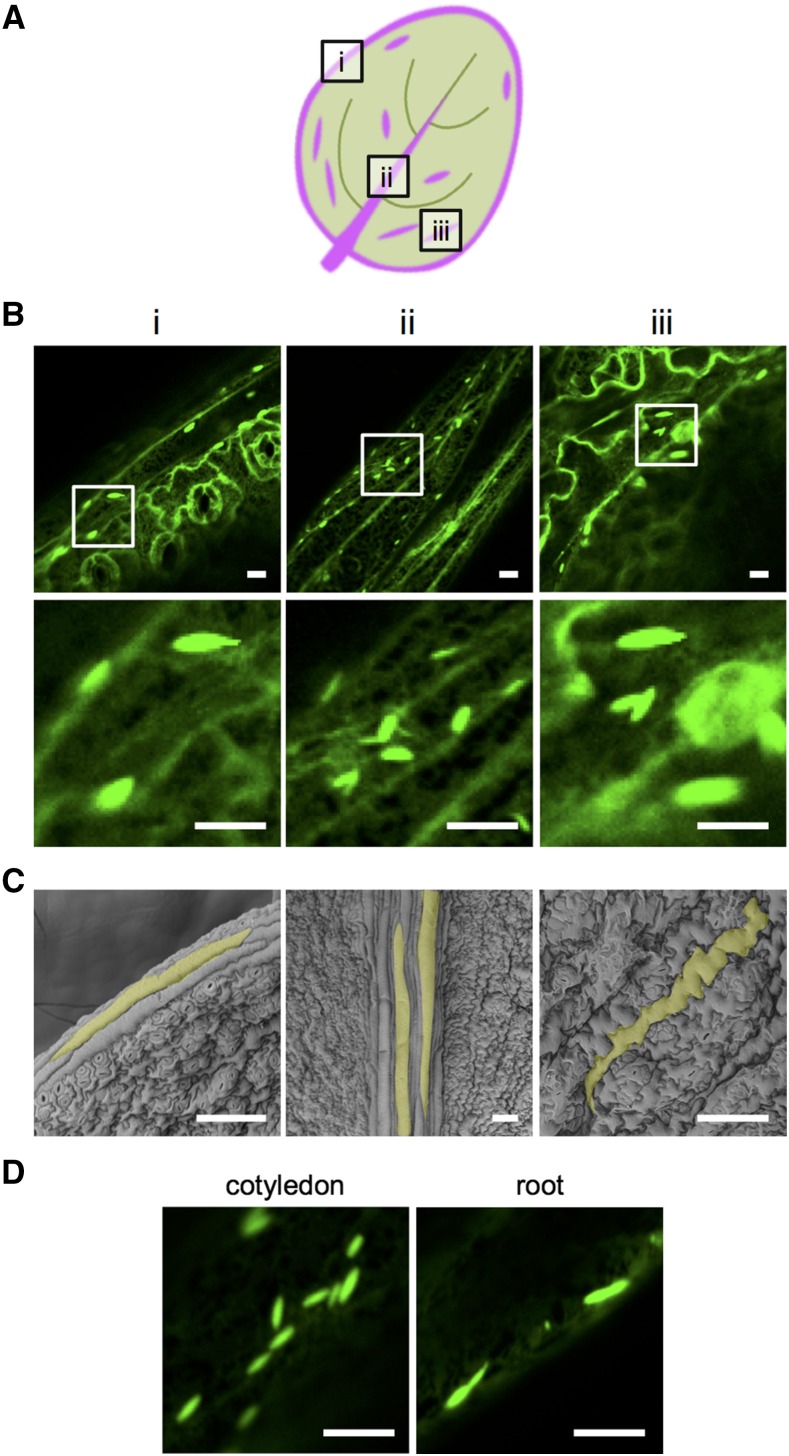

To elucidate the presence of ER bodies in rosette leaves, we carefully observed juvenile leaves of transgenic plants (GFP-h) expressing the green fluorescent protein fused with an ER-retension signal (GFP-HDEL, His-Asp-Glu-Leu) grown aseptically in plates for 2 weeks. ER bodies were found only in specific leaf cells (Fig. 1A). We named the ER bodies found in rosette leaves as “L-ER bodies.” L-ER bodies were always observed in three types of epidermal cells: marginal cells, epidermal cells covering the midrib, and giant pavement cells (Fig. 1, A and B). These epidermal cells were usually longer and larger than typical pavement cells without ER bodies (Fig. 1C). L-ER bodies were morphologically similar to typical spindle-shaped ER bodies found in cotyledons and roots (Fig. 1, B and D). A similar distribution of L-ER bodies was found in other leaves with different leaf positions (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

The distribution of L-ER bodies in Arabidopsis rosette leaves. A, Schematic representation of L-ER body distribution in Arabidopsis rosette leaves. L-ER bodies were found in the following three types of epidermal cells that are located in the regions indicated in magenta: marginal cells (i), epidermal cells covering the midrib (ii), and extremely large pavement cells (iii). L-ER bodies were not found in other types of epidermal cells. B, Confocal images of the abaxial epidermal surface of juvenile leaves from 2-week-old transgenic Arabidopsis (GFP-h) expressing ER-localized GFP-HDEL. Roman numerals represent the locations of the epidermal cells as shown in (A). (Bottom) Magnified images of the regions surrounded by open boxes (top). Bars = 10 μm. C, Scanning electron micrographs of the abaxial epidermal surface of juvenile leaves from 2-week-old Arabidopsis plants. Bars = 100 μm. D, Confocal images of epidermal cells from the cotyledons and roots of 7-d-old seedlings of GFP-h. Bars = 10 μm.

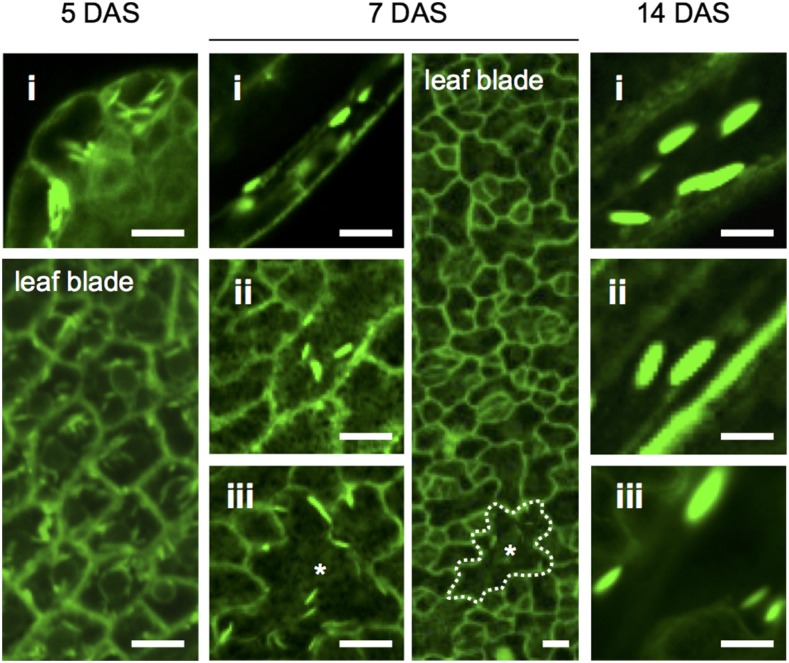

We next investigated the developmental changes in L-ER body distribution in juvenile leaves. In the early stages of leaf development (5 days after sowing [DAS]), when the juvenile leaf had just emerged, L-ER bodies were observed in the epidermal cells of the whole leaf (Fig. 2). In the middle stages of leaf development (7 DAS), the number of pavement cells containing L-ER bodies decreased, whereas L-ER bodies were constitutively observed in marginal elongated cells, epidermal cells covering the midrib, and some pavement cells (Fig. 2). In the later stages of leaf development (14 DAS), L-ER bodies were observed in only three types of the cells: marginal elongated cells, epidermal cells covering the midrib, and giant pavement cells (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Developmental changes in the distribution of ER bodies in rosette leaves. Confocal images of the epidermal surface of juvenile leaves of GFP-h. Roman numerals represent the locations of the epidermal cells in Arabidopsis rosette leaves as shown in Figure 1A: marginal cells (i), epidermal cells covering the midrib (ii), and giant pavement cells (iii). The number of DAS is indicated at the top of the panels. At 5 DAS, L-ER bodies were found in the entirety of a newly emerging leaf. At 7 DAS, L-ER bodies disappeared during leaf development, except in the three aforementioned types of epidermal cells (i–iii). Asterisks indicate the same cell that was larger than the other pavement cells in blade. At 14 DAS, L-ER bodies remained in the three types of epidermal cells (i–iii). The 7-DAS image on the right was processed using sd projection along the z axis with ImageJ software. Bars = 10 μm.

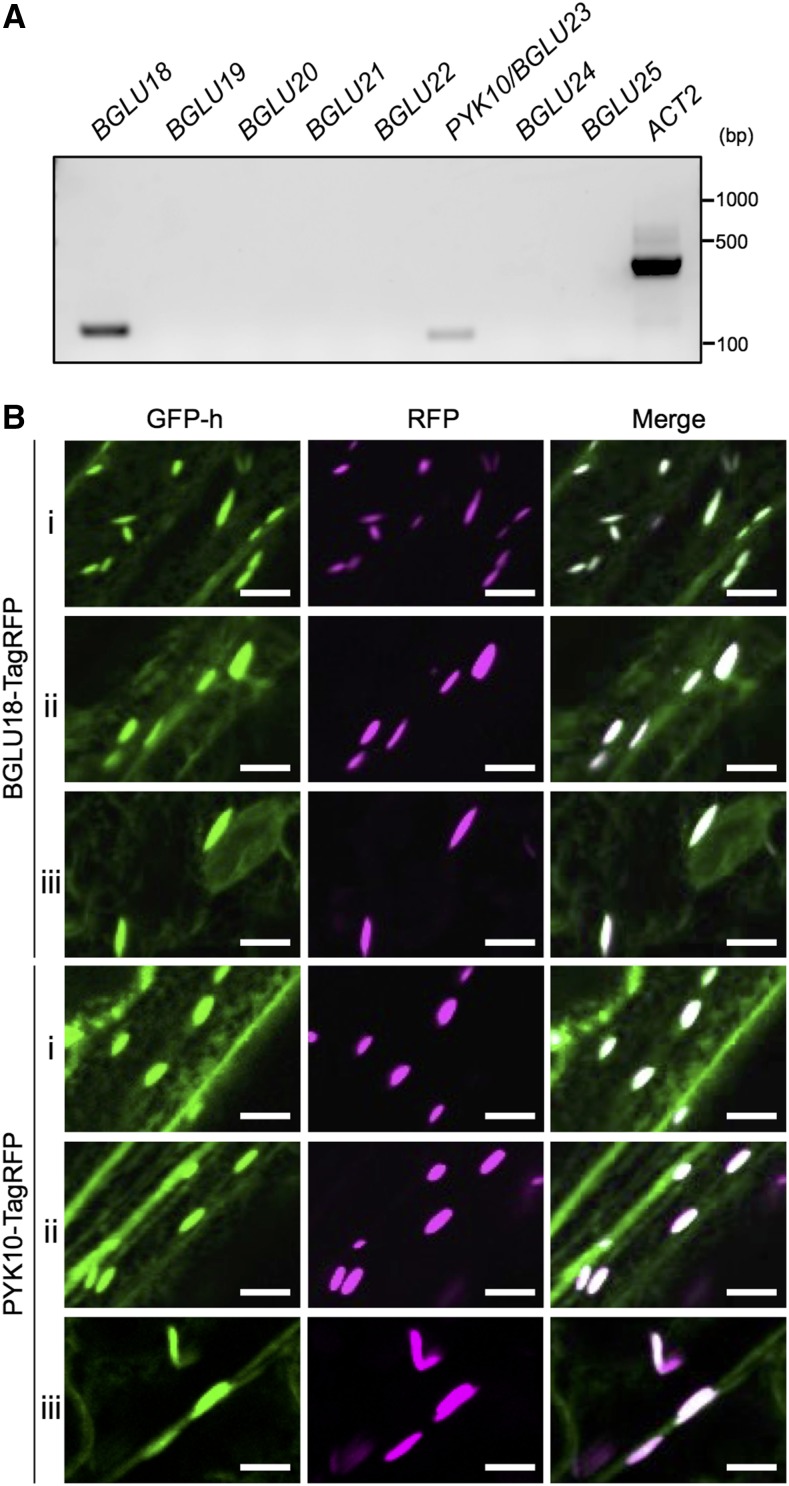

L-ER Bodies Accumulate BGLU18 and PYK10/BGLU23

Next, we investigated the compounds accumulated in L-ER bodies. Constitutive and inducible ER bodies accumulate distinct β-glucosidases, namely PYK10/BGLU23 and BGLU18, respectively (Ogasawara et al., 2009). The Arabidopsis genome contains eight members of BGLU subfamily III (BGLU18, BGLU19, BGLU20, BGLU21, BGLU22, PYK10/BGLU23, BGLU24, and BGLU25), all of which possess an ER retention signal at their C terminus (Xu et al., 2004; Nakano et al., 2014). Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analysis revealed that BGLU18 and PYK10/BGLU23 are expressed in rosette leaves (Fig. 3A). This result is consistent with a previous report showing that these two β-glucosidase genes are expressed in 16-d-old Arabidopsis shoots, using publicly available microarray data (Yamada et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

BGLU18 and PYK10/BGLU23 accumulate in L-ER bodies. A, RT-PCR analysis of the expression of eight BGLU genes (BGLU18, BGLU19, BGLU20, BGLU21, BGLU22, PYK10/BGLU23, BGLU24, and BGLU25) in Arabidopsis rosette leaves. The expression of BGLU18 and PYK10/BGLU23 was detected in rosette leaves. Total RNA from juvenile leaves of 2-week-old Arabidopsis wild-type plants was subject to RT. ACT2 was used as an internal control. B, Confocal images of rosette leaves from 2-week-old GFP-h harboring the ProBGLU18:BGLU18-TagRFP gene or the ProPYK10:PYK10-TagRFP gene. Fluorescence of BGLU18-TagRFP and PYK10-TagRFP was detected in L-ER bodies in marginal cells (i), epidermal cells covering the midrib (ii), and giant pavement cells (iii), the locations of which are shown in Figure 1A. RFP, red fluorescent protein. Bars = 10 μm.

To visualize the distribution and subcellular localization of BGLU18 and PYK10 in rosette leaves, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis lines carrying either ProBGLU18:BGLU18-TagRFP (red fluorescent protein) or ProPYK10:PYK10-TagRFP in a GFP-h background. Fluorescence of both BGLU18-TagRFP and PYK10-TagRFP fusion proteins was detected in the three types of epidermal cells that develop L-ER bodies (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, fluorescence of BGLU18-TagRFP and PYK10-TagRFP was specifically localized in L-ER bodies labeled with GFP (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that two types of β-glucosidases, BGLU18 and PYK10/BGLU23, are accumulated in L-ER bodies.

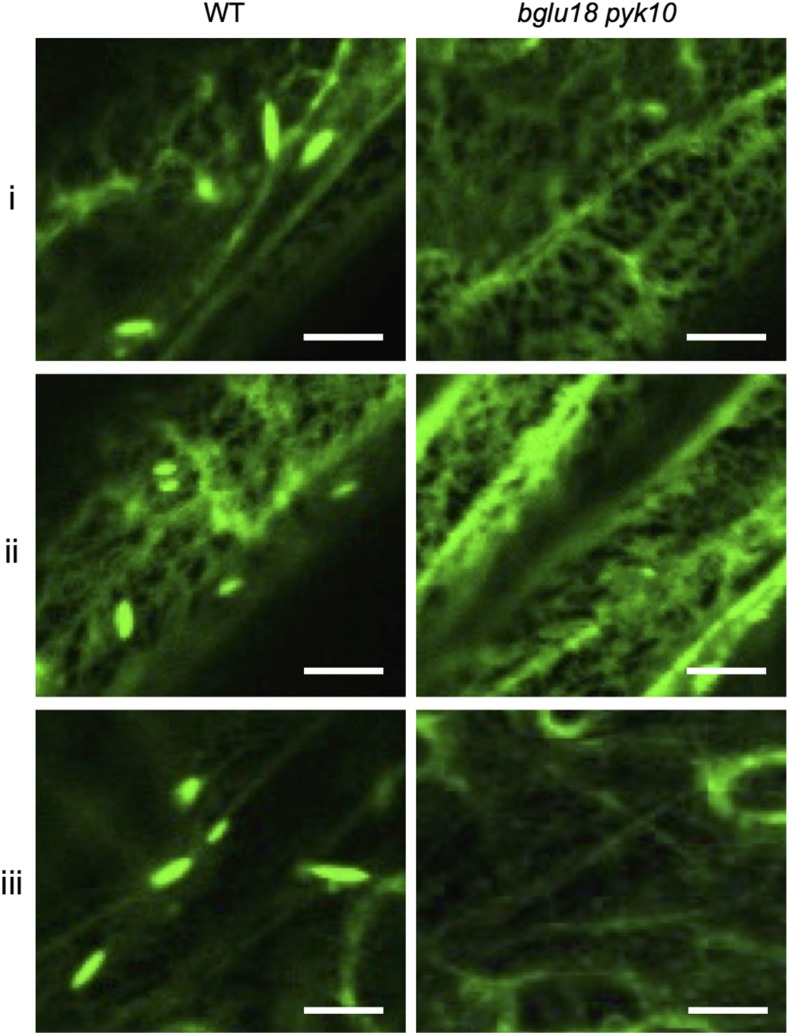

Next, we investigated the formation of L-ER bodies in the bglu18 pyk10 double mutant in the GFP-h background. No L-ER bodies were observed in the three types of epidermal cells in the bglu18 pyk10 mutant (Fig. 4). Thus, BGLU18 and PYK10 were required for L-ER body formation. These observations also suggest that BGLU18 and PYK10 are primary components of L-ER bodies.

Figure 4.

Typical spindle-shaped L-ER bodies are not found in bglu18 pyk10. Confocal images of rosette leaves from the wild type (WT) and bglu18 pyk10 mutants expressing GFP-HDEL. Spindle-shaped L-ER bodies were not found in leaf cells of bglu18 pyk10 mutants, including the marginal cells (i), epidermal cells covering the midrib (ii), and giant pavement cells (iii), the locations of which are shown in Figure 1A. Bars = 10 μm.

NAI1 Regulates Formation of L-ER Bodies

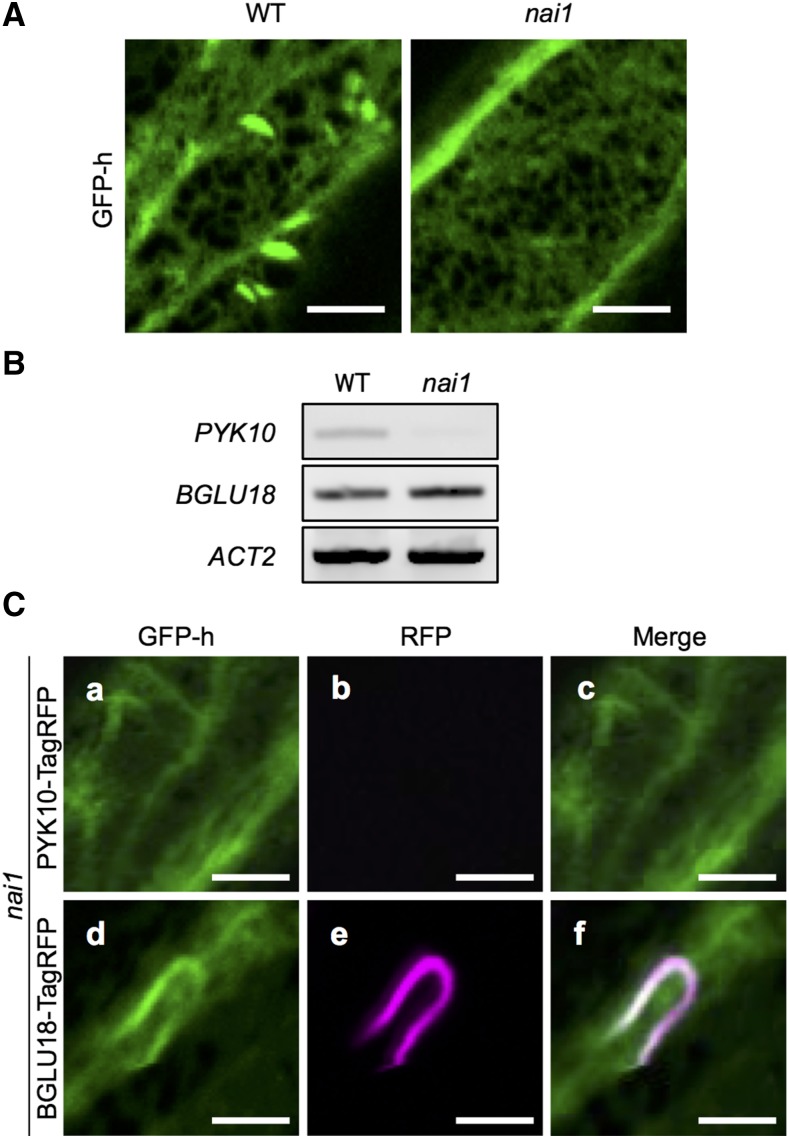

The basic helix-loop-helix–type transcription factor NAI1 is known to regulate ER-body formation in seedlings (Matsushima et al., 2004). To investigate the involvement of NAI1 in the formation of L-ER bodies, we observed rosette leaves of the nai1-1 mutant in the GFP-h background. L-ER bodies with a spindle-shaped structure were rarely observed in nai1 leaves (Fig. 5A), indicating that NAI1 is required for the formation of L-ER bodies. RT-PCR analysis revealed that, in nai1 leaves, no PYK10 transcripts were detectable, whereas BGLU18 transcripts were present (Fig. 5B). These results are in agreement with previous observations that the expression of PYK10 in seedlings is regulated by NAI1 (Matsushima et al., 2004), whereas the expression of BGLU18 is not regulated by NAI1 in wounded cotyledons (Ogasawara et al., 2009; Yamada et al., 2009). Confocal imaging revealed that the nai1 mutant showed no PYK10-TagRFP signals, suggesting that the expression of PYK10 in rosette leaves is regulated by NAI1 (Fig. 5C). However, we detected elongated BGLU18-containing structures in some parts of the ER in nai1 leaves (Fig. 5C). The irregular shape of the structures in the nai1 mutant may be caused by the lack of NAI2, which is responsible for the accumulation of PYK10 in ER bodies, as well as that of MEBs, which are integral membrane proteins found in constitutive ER bodies (Yamada et al., 2009, 2013). These results suggest that NAI1 is required for the formation of normal, spindle-shaped L-ER bodies and the expression of PYK10. The expression of BGLU18 is likely regulated by yet-unknown transcription factor(s).

Figure 5.

Expression of BGLU18 and PYK10 genes in nai1 leaves. A, Confocal images of 2-week-old leaf epidermal cells of the wild type (WT) and nai1 mutant expressing GFP-HDEL. No typical spindle-shaped ER bodies were found in nai1 mutant. Bars = 10 μm. B, RT-PCR analysis of the expression of PYK10 and BGLU18 genes in wild-type and nai1 leaves. The expression of BGLU18 was detected in nai1 leaves, whereas that of PYK10 was not. Total RNA from juvenile leaves from 2-week-old wild-type and nai1 plants was subjected to RT. ACT2 was used as an internal control. C, Confocal images of nai1 rosette leaves harboring the ProPYK10:PYK10-TagRFP gene (a–c) or the ProBGLU18:BGLU18-TagRFP gene (d–f). RFP, red fluorescent protein. No PYK10-TagRFP fluorescence was detected in nai1 leaves, whereas that of BGLU18-TagRFP was found in some parts of the ER tubules. Bars = 10 μm.

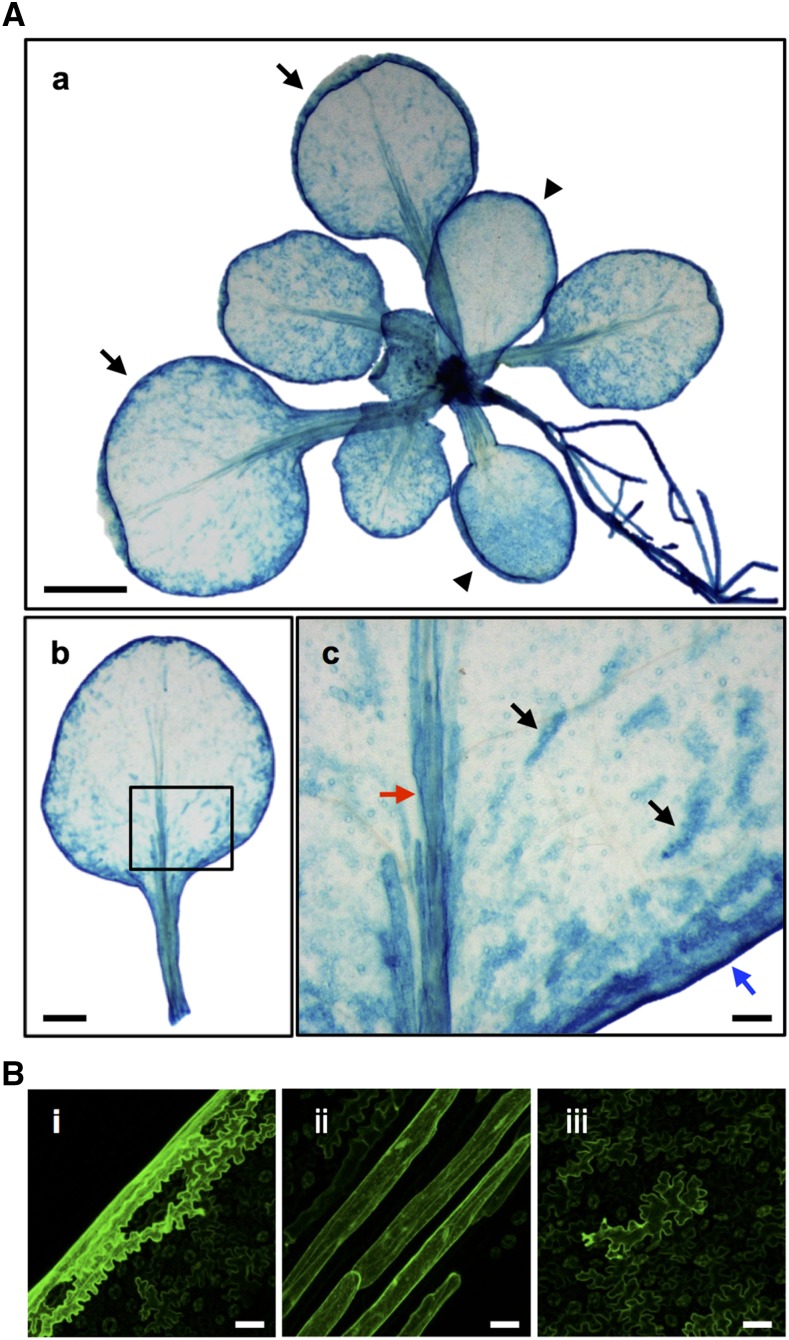

To further investigate the involvement of NAI1 in L-ER body formation, we monitored the expression pattern of NAI1 using the transgenic Arabidopsis line carrying ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS. The GUS activity of the NAI1 promoter was observed in the leaf margin, midrib, and in patches in the leaf blade (Fig. 6A). GFP signals were also detected in these parts of the rosette leaves (Fig. 6B). These specific NAI1 expression patterns were well associated with the distribution of L-ER bodies in rosette leaves. Taken together, these results suggest that NAI1 is involved in the formation of L-ER bodies.

Figure 6.

Expression pattern of NAI1 in rosette leaves. A, GUS staining of transgenic Arabidopsis harboring the ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS gene. A(a), Whole view of a 2-week-old ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS plant. Arrowheads and arrows indicated cotyledons and juvenile leaves, respectively. Bar = 0.5 mm. A(b), Juvenile leaf from a 2-week-old ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS plant. Bar = 0.5 mm. A(c), Magnified image of the area surrounded by a black box in (Ab). GUS signals were observed in three types of epidermal cells: marginal cells (blue arrow), epidermal cells covering the midrib (red arrow), and giant pavement cells (black arrows). Bar = 0.1 mm. B, Confocal images showing the expression pattern of NAI1 in a 2-week-old rosette leaf harboring the ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS gene. GFP signals were found in marginal cells (i), epidermal cells covering the midrib (ii), and giant pavement cells (iii), the locations of which are shown in Figure 1A. Images were processed using sd projection along the z axis with ImageJ software. Bars = 50 μm.

L-ER Bodies Play a Role in the Defense Against A. vulgare

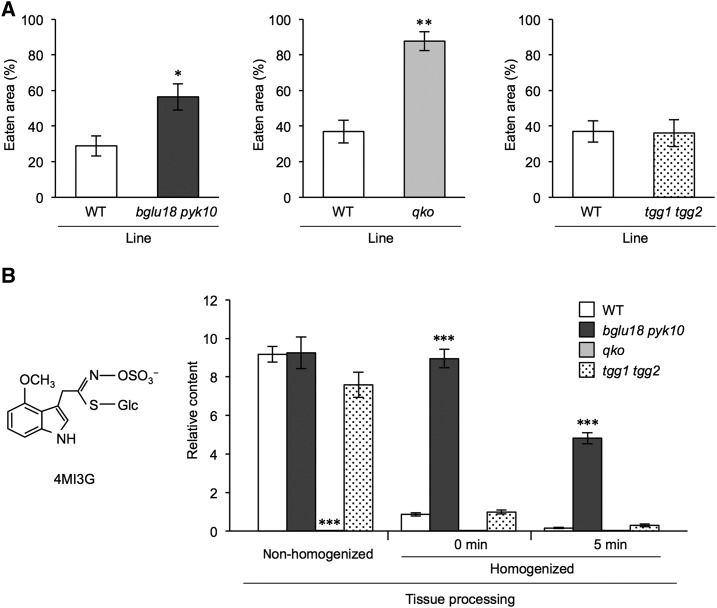

We performed a dual-choice feeding assay with A. vulgare to investigate the function of L-ER bodies in defense against herbivory. We found that the bglu18 pyk10 double mutant was more susceptible to A. vulgare attack than the wild type (Fig. 7A; Supplemental Fig. S2). Because bglu18 pyk10 showed impaired formation of L-ER bodies in the rosette leaves (Fig. 4), this result suggests that L-ER bodies play an important role in the defense against herbivory. We next investigated the involvement of the glucosinolate-myrosinase system in the defense against A. vulgare. The myb28 myb29 cyp79b2 cyp79b3 quadruple knockout mutant (qko), which is deficient in the production of both aliphatic and indole glucosinolates (Sun et al., 2009), showed far greater susceptibility to A. vulgare than that of the wild type (Fig. 7A; Supplemental Fig. S2). However, the susceptibility of the tgg1 tgg2 mutant did not differ from that of the wild type (Fig. 7A; Supplemental Fig. S2). These results suggest that, although glucosinolates play an important role in the defense against A. vulgare, the conventional myrosinases in myrosin cells, namely TGG1 and TGG2, are not involved in this defense. BGLU18 and PYK10 in L-ER bodies may function as myrosinases to activate the glucosinolate-myrosinase defense system against herbivory in rosette leaves.

Figure 7.

The bglu18 pyk10 double mutants show increased susceptibility to A. vulgare and decreased 4MI3G hydrolytic activities. A, Four plants of the wild type (WT) and mutants (bglu18 pyk10, qko, and tgg1 tgg2) were planted in the same pot to allow pairwise comparisons. Ten A. vulgare individuals were placed in one pot for 24 h. Eaten area (%) represents the ratio of leaf area eaten by A. vulgare compared to the leaf area before feeding. Values represent means ± se (n = 11 [wild type versus bglu18 pyk10], n = 14 [wild type versus qko; wild type versus tgg1 tgg2]). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, paired Student’s t test. B, The relative content of 4MI3G in extracts of the aerial parts of 2-week-old wild-type (WT), bglu18 pyk10, qko, and tgg1 tgg2 plants as analyzed using LC-MS. Glucosinolates were extracted from tissues that were nonhomogenized, immediately after homogenization (0 min), and 5 min after homogenization (5 min). The chemical structure of 4MI3G is depicted on the left. Values represent the means ± se (n = 6–8). Dunnett’s test was used for pairwise comparisons of wild-type and respective mutant plants under each condition. ***P < 0.001.

To examine the ability of BGLU18 and PYK10 to hydrolyze glucosinolates, we monitored the breakdown of 20 different glucosinolates in the tissue homogenates of Arabidopsis rosette leaves. All the glucosinolates examined, except 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate (4MI3G), were efficiently degraded in the bglu18 pyk10 mutant as in wild type (Supplemental Figs. S3 and S4); however, the hydrolysis of 4MI3G was remarkably retarded in the bglu18 pyk10 mutant compared with that in wild type and in the tgg1 tgg2 mutant (Fig. 7B). Just after the plants were homogenized, most 4MI3G remained intact in the bglu18 pyk10 mutant, although it was rapidly hydrolyzed in wild-type and tgg1 tgg2 plants. Five minutes after homogenization, a significant amount of 4MI3G was found in the bglu18 pyk10 mutant. 4MI3G accumulation levels in the nonhomogenized rosette leaves were not significantly different among wild-type, bglu18 pyk10, and tgg1 tgg2 plants (Fig. 7B). Glucosinolates were not observed to accumulate in qko (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that 4MI3G is hydrolyzed by BGLU18 and/or PYK10, but not by TGG1 and TGG2, and that the product(s) of this hydrolysis provide effective defense against A. vulgare.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized a novel type of ER body in specific epidermal cells of Arabidopsis rosette leaves and designated them as “L-ER bodies.” L-ER bodies accumulated two types of β-glucosidases, namely BGLU18 and PYK10, which have been shown to accumulate specifically in inducible ER bodies and constitutive ER bodies, respectively (Yamada et al., 2009). This indicates that the β-glucosidase accumulation of L-ER bodies shares similarities with both constitutive and inducible ER bodies. The expression of BGLU18 and PYK10 were differentially regulated by NAI1 in Arabidopsis rosette leaves. However, there may be some common mechanism to integrate the expression of BGLU18 and PYK10 in the same cells for the accumulation of both BGLU18 and PYK10 in L-ER bodies.

L-ER bodies were found in the leaf marginal cells (Fig. 1), where high concentrations of glucosinolates have also been found in Arabidopsis (Shroff et al., 2008; Koroleva et al., 2010; Sønderby et al., 2010). Considering our findings, it is strongly suggested that the leaf marginal cells store both glucosinolates and β-glucosidases within the same cell. This is in contrast to the defense system based on myrosin cells, whereby glucosinolates and myrosinases are accumulated in distinct cells, namely substrate-accumulating cells and myrosin cells, respectively. Tissue damage resulting from herbivory or pathogen infection brings the substrate and enzyme into contact to produce toxic isothiocyanates. In the defense system based on ER bodies, glucosinolates and β-glucosidases are accumulated within the same cell but separated in vacuoles and ER bodies, respectively, to avoid unfavorable reaction in the nondamaged cells. Thus, ER bodies function as a part of the intracellular mustard oil bomb system. Similar spatial organization of the glucosinolate-myrosinase system within the same cell was previously reported in other Brassicaceae plants (Iversen, 1970; Lüthy and Matile, 1984).

Specific distribution of L-ER bodies may be important to protect leaves from herbivory. L-ER bodies in the leaf marginal cells will efficiently protect leaves from herbivores that normally start feeding from the leaf margin. In addition to the marginal cells, L-ER bodies were also found in the epidermal cells covering the midrib and giant pavement cells in Arabidopsis rosette leaves (Fig. 1). Although it is not known whether these cells accumulate glucosinolates, this distribution of L-ER bodies in leaves may be an efficient defense against herbivores. The key enzymes involved in biosynthesis of indole and aliphatic glucosinolates are localized in vascular cells (Nintemann et al., 2018), suggesting high concentration of glucosinolates in vascular tissue. L-ER bodies in the epidermal cells covering the midrib may efficiently protect vascular tissue from herbivores that feed on the leaf sap. Myrosin cells also develop on the inner side of leaves along with the leaf vascular tissues (Ueda et al., 2006). Therefore, vascular tissues are double-protected, with L-ER bodies and mycosin cells in the midrib. L-ER bodies in giant pavement cells may also play a role in the mustard oil bomb system. These cells are relatively larger than normal pavement cells; such larger cells with L-ER bodies, which are scattered in the leaf blade, may be easily collapsed by herbivory.

Myrosin cells are thought to play a central role in the mustard oil bomb system in Arabidopsis rosette leaves (Ueda et al., 2006). In fact, a tgg1 tgg2 double mutant was reported to be more susceptible to feeding by two Lepidopteras, Trichoplusia ni and Manduca sexta, than the wild type (Barth and Jander, 2006). As a result, the importance of L-ER bodies in the mustard oil bomb system has been overlooked to date. However, two homopterans, Myzus persicae and Brevicoryne brassicae, have been reported whose herbivory behavior was unaffected by the tgg1 tgg2 double mutant (Barth and Jander, 2006). Our dual-choice feeding assays indicate that L-ER bodies play a role in decreasing herbivory damage by A. vulgare (Fig. 7A). Combined with the results of the feeding assay using the glucosinolate-deficient qko mutant, L-ER bodies are strongly suggested to function as a part of the mustard oil bomb system.

The differential action of L-ER bodies and myrosin cells against A. vulgare is likely a result of differences in glucosinolate distribution between the tissues or organs. The distribution pattern of glucosinolates varies depending on tissues, organs, and developmental stages. In Arabidopsis, higher amounts of indole glucosinolates are stored in roots than in other organs, whereas higher amounts of aliphatic glucosinolates are accumulated in leaves than in roots (Brown et al., 2003). This differential glucosinolate distribution among organs is thought to be optimal and efficient for defense against various herbivores. Indeed, indole glucosinolates and aliphatic glucosinolates have different effects on lepidopteran herbivores. The feeding behavior of T. ni and M. sexta is influenced by aliphatic glucosinolates but not by indole glucosinolates (Müller et al., 2010).

In addition to the distribution pattern of glucosinolates, myrosinase substrate specificity is also important to various herbivores. PYK10 was recently shown to have myrosinase activity, and it deglycosylates I3G (Nakano et al., 2017). It has also been suggested that BGLU18 acts as a myrosinase based on its protein structure (Xu et al., 2004; Nakano et al., 2017) although its substrate specificity has not been determined. In this report, we observed that the hydrolysis of 4MI3G, an indole glucosinolate, was impaired in the bglu18 pyk10 mutant compared with that in wild-type and the tgg1 tgg2 mutant (Fig. 7B). This result suggests that BGLU18 and/or PYK10 hydrolyze 4MI3G. 4MI3G is also known to be hydrolyzed in living plant cells by PENETRATION2, and the product of this hydrolysis functions as a defense against microbial pathogens (Bednarek et al., 2009; Clay et al., 2009). The end-product of 4MI3G hydrolysis by PENETRATION2 in living plant cells is suggested to be different from that in insect-mediated tissue destruction (Bednarek et al., 2009). Our results strongly suggest that BGLU18 and/or PYK10 function as defenses against herbivores through hydrolysis of 4MI3G after the collapse of plant cells. On the other hand, the hydrolysis of several aliphatic glucosinolates was suppressed in the tgg1 tgg2 mutant (Supplemental Fig. S3). These results are consistent with a previous report showing a larger effect of tgg1 tgg2 mutations on aliphatic glucosinolate degradation than on indole glucosinolate degradation (Barth and Jander, 2006). Arabidopsis leaves might efficiently optimize plant defenses against various predators by accumulating distinct myrosinases with different substrate specificities in different destinations, specifically L-ER bodies and myrosin cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) accession Columbia-0 (Col-0, CS60000) was used as the wild type. We used the Arabidopsis transgenic line, GFP-h, which carries a Pro-35S:SP-GFP-HDEL gene. SP-GFP-HDEL is composed of the pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) signal peptide 2S albumin, followed by GFP with an ER retention signal, HDEL (Mitsuhashi et al., 2000; Hayashi et al., 2001). GFP-h/nai1-1 is an ER body-deficient mutant isolated from mutagenized GFP-h (Matsushima et al., 2003b). Seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% (v/v) ethanol and aseptically sown on Murashige & Skoog plates containing 0.5% (w/v) gellan gum (Wako), 1% (w/v) Suc, 0.5% (v/v) MES-KOH buffer (pH 5.7), and 1× Murashige and Skoog salts mixture (Wako). Plants were grown in plates at 22°C under continuous light conditions.

Transgenic Plants

To construct ProPYK10:PYK10-TagRFP and ProBGLU18:BGLU18-TagRFP, each genomic fragment of PYK10 and BGLU18, including a 2-kb upstream region, was amplified and subcloned into the pENTR 1A plasmid using an In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Clontech). Each DNA fragment was transferred into a binary vector pGWB659-HDEL via the LR reaction using Gateway LR clonase Enzyme mix (Invitrogen). The binary vector pGWB659-HDEL was produced by inserting an ER retention signal (HDEL) downstream of TagRFP in the binary vector pGWB659 (Nakamura et al., 2010). The amino acid linker between the TagRFP and HDEL was GGSG. The constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101), and the transformed bacteria were infiltrated into Arabidopsis plants (GFP-h, GFP-h/nai1-1) via the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). T1 seeds were selected using medium containing 10 mg/L glufosinate-ammonium. Primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS transgenic plants were generated through the following steps. To fuse PCR products in frame with a C-terminal fusion tag, a pENTR1A vector (Invitrogen) was modified by site-directed mutagenesis using pENTR1A_modF1 and pENTR1A_modR1 primers. The resulting vector, designated pENTR1Axe, lacks two nucleotides (T, A) after the EcoRV site in the multiple cloning site. To generate the ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS entry vector, the DNA fragments of the NAI1 promoter, including the 3,223-bp upstream region from just before the start codon, as well as the sGFP, GUS, and the NAI1 terminator of the 1,365-bp downstream region after the stop codon, were amplified using the following primers: pENTR1Axe-ProNAI1_3k_F1 and ProNAI1-sGFP_R1 for the NAI1 promoter, ProNAI1-sGFP_F1 and mCherry-GGSG_R1 for sGFP, GGSG-GUS_F1 and GUS-TerNAI1_R1 for GUS, GUS-TerNAI1_F1 and TerNAI1-pENTR1Axe_R1 for the NAI1 terminator. These amplicons were introduced into the XmnI/EcoRV double-digested pENTR1Axe using the In-Fusion cloning reaction (Clontech). The resulting clone was transferred into the pGWB501 vector via the LR reaction using the Gateway system (Invitrogen) to express sGFP-GUS under the control of the NAI1 promoter. The introduction of the vector into A. tumefaciens and the infiltration of the transformed bacteria into Arabidopsis wild-type plants were executed as described above. The sequences of the primers used are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

RT-PCR Analyses

Total RNA was isolated from juvenile leaves of 14-d-old wild-type and nai1-1 plants using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Total RNA (500 ng) was used for the synthesis of cDNA using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (TOYOBO). PCR was performed using the cDNA and GoTaq polymerase (Promega). PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 3 min, 30 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The PCR products were separated by 2.0% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. The DNA bands were detected with a LAS-3000 Imager (Fujifilm). Gene-specific primers are shown in Supplemental Table S2.

Microscopy

Confocal images were obtained using a laser scanning microscope (LSM 780; Carl Zeiss). An argon laser (488 nm) and a 491/550-nm band-pass filter were used to observe GFP, whereas a Diode-Pumped Solid-State laser (561 nm) and a 560/656-nm band-pass filter were used for TagRFP.

Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

For scanning electron microscopy fixation, juvenile leaves of wild-type plants were incubated in fixation solution (2.5% [v/v] formalin, 2.5% [v/v] acetic acid, and 45% [v/v] ethanol) overnight at room temperature. Fixed leaves were subjected to serial dehydration in 50% (twice), 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 99.5%, and 100% (v/v) ethanol for 20 min per step, followed by an overnight dehydration in 100% (v/v) ethanol. Finally, the leaves were dried with a critical point dryer (JCPD-5; JEOL) and coated in gold using a Fine Coater (JFC-1200; JEOL). Samples were inspected with a table-top Miniscope (TM-1000; Hitachi).

GUS Staining

Samples were harvested from ProNAI1:sGFP-GUS plants at 14 DAS. Samples were placed in ice-cold 90% (v/v) acetone for 15 min. Then, samples were transferred into GUS staining solution containing 0.5 mg/mL X-Gluc, 0.1 m sodium P buffer, pH 7.0, 10 EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.5–1 mm potassium ferricyanide, 0.5–1 mm potassium ferrocyanide, and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100. Samples in the GUS staining solution were placed in a vacuum and incubated at 37°C for 13.5 h. The stained plants and tissues were mounted onto glass slides and inspected with a stereoscopic microscope (SteREO Lumar V12; Carl Zeiss).

Feeding Assay

Four seedlings (10 DAS) of both the wild-type and mutant plants were transferred to a single pot filled with soil and grown for another 4 d (total 14 DAS). Ten Armadillidium vulgare adults fasted for 2 d were put into the pot. Photos were taken before feeding and 24 h after feeding. Then, areas of the wild-type and mutant plants in the images were measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), and the eaten leaf areas were calculated as a percentage of the leaf areas before feeding. Plants and A. vulgare were bred at 23°C under a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer Analysis of Glucosinolates

The following three types of samples were prepared from wild-type, bglu18 pyk10, tgg1 tgg2, and qko plants (14 DAS): nonhomogenized, 0 min after homogenization, and 5 min after homogenization. The aerial parts of the plants were collected and freeze-dried for the nonhomogenized samples. The aerial parts of plants were collected and homogenized with the Mixer Mill MM300 (Retsch) at 30 Hz and 4°C for 5 min for the homogenized samples. The homogenized samples were then centrifuged at 20,000g at 4°C for 20 s and immediately freeze-dried (0 min after homogenization). Alternatively, the homogenized samples were incubated at 23°C for 5 min and then freeze-dried after centrifugation (5 min after homogenization).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometer (LC-MS) analysis of glucosinolates was conducted as described in Sawada et al. (2017) with some modification. Approximately 3.3 mg of dried samples (six to eight replicates of each sample) was used. After adding extraction solvent (80% [v/v] methanol, 0.1% [v/v] formic acid, 8.4 nmol/L lidocaine, and 210 nmol/L 10-camphorsulfonic acid as internal standards, 4 mg DW/mL), the samples were homogenized using a Mixer Mill MM300 (Retsch) at 20 Hz for 10 min and centrifuged for 3 min at 8,000g. The supernatant (100 μL) was transferred to a new tube, dried, dissolved in 1000 µL ultrapure water, and filtered using MultiScreen HTS 384-Well Filter Plates (Merck Millipore). Two microliters of the solution extract (final concentration: ∼400 μg DW/mL) were subjected to LC-triple quadrupole MS on the LCMS-8050 with a Nexera MP system (Shimadzu). Twenty glucosinolates and two internal standards were detected in the extract solution based on optimized selected reaction monitoring conditions and LC retention time. The following glucosinolates were purchased and used to determine retention times: Sinigrin (Sigma-Aldrich), 4-Methylsulfinyl-n-butyl glucosinolate (Nagara Science), 3-Methylsulfinyl-n-propyl glucosinolate (PhytoLab), 4-Methylthio-n-butyl glucosinolate (PhytoLab), I3G (EXTRASYNTHESE), 1-Methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate (EXTRASYNTHESE), and phenylethyl glucosinolate (LKT Laboratories). The retention times of the other glucosinolates were estimated from their Mr values, side-chain structures, and generation of the fragment ion HSO4− (m/z 97). The mass accuracy in Q1 and Q3 was within 0.6 m/z units.

Statistical Analyses

In the dual-choice feeding assays, Student’s t test was used for pairwise comparisons of wild-type and respective mutant plants. In the LC-MS analysis, Dunnett’s test was used for pairwise comparisons of wild-type and respective mutant plants under each tissue processing condition.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database under accession numbers: ACTIN2 (ACT2; At3g18780), BGLU18 (At1g52400), BGLU19 (At3g21370), BGLU20 (At1g75940), BGLU21 (At1g66270), BGLU22 (At1g66280), PYK10/BGLU23 (At3g09260), BGLU24 (At5g28510), BGLU25 (At3g03640), CYP79B2 (At4g39950), CYP79B3 (At2g22330), MYB28 (At5g61420), MYB29 (At5g07690), NAI1 (At2g22770), TGG1 (At5g26000), TGG2 (At5g25980).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Distribution of L-ER bodies in each leaf position of a 2-week-old plant.

Supplemental Figure S2. Dual-choice feeding assays with A. vulgare.

Supplemental Figure S3. The relative content of aliphatic glucosinolates in extracts of the aerial parts of 2-week-old wild type, bglu18 pyk10, qko, and tgg1 tgg2 plants as analyzed using LC-MS.

Supplemental Figure S4. The relative content of indole glucosinolates and aromatic glucosinolates in extracts of the aerial parts of 2-week-old wild type, bglu18 pyk10, qko, and tgg1 tgg2 plants as analyzed using LC-MS.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used for plasmid DNA construction.

Supplemental Table S2. Primer sequences used for RT-PCR analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tsuyoshi Nakagawa for sharing materials. We also thank the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for providing seeds of the Arabidopsis lines.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science with Specially Promoted Research of a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 15H05776 to I.H.-N.), The National Science Centre of Poland (OPUS grant no. UMO-2016/23/B/NA1/01847 to K.Y.), The Foundation for Polish Science (grant no. TEAM/2017-4/41 to K.Y.), and the Małopolska Centre of Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University.

References

- Barth C, Jander G (2006) Arabidopsis myrosinases TGG1 and TGG2 have redundant function in glucosinolate breakdown and insect defense. Plant J 46: 549–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek P, Pislewska-Bednarek M, Svatoš A, Schneider B, Doubsky J, Mansurova M, Humphry M, Consonni C, Panstruga R, Sanchez-Vallet A, et al. (2009) A glucosinolate metabolism pathway in living plant cells mediates broad-spectrum antifungal defense. Science 323: 101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekwilder J, van Leeuwen W, van Dam NM, Bertossi M, Grandi V, Mizzi L, Soloviev M, Szabados L, Molthoff JW, Schipper B, et al. (2008) The impact of the absence of aliphatic glucosinolates on insect herbivory in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 3: e2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bones AM, Rossiter JT (1996) The myrosinase-glucosinolate system, its organisation and biochemistry. Physiol Plant 97: 194–208 [Google Scholar]

- Borek V, Elberson LR, McCaffrey JP, Morra MJ (1997) Toxicity of rapeseed meal and methyl isothiocyanate to larvae of the black vine weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J Econ Entomol 90: 109–112 [Google Scholar]

- Brown PD, Tokuhisa JG, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J (2003) Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 62: 471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskov S, Serra B, Rosa E, Sørensen H, Sørensen JC (2002) Effects of intact glucosinolates and products produced from glucosinolates in myrosinase-catalyzed hydrolysis on the potato cyst nematode (Globodera rostochiensis Cv. Woll). J Agric Food Chem 50: 690–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay NK, Adio AM, Denoux C, Jander G, Ausubel FM (2009) Glucosinolate metabolites required for an Arabidopsis innate immune response. Science 323: 95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk KL, Kästner J, Bodenhausen N, Schramm K, Paetz C, Vassão DG, Reichelt M, von Knorre D, Bergelson J, Erb M, et al. (2014) The role of glucosinolates and the jasmonic acid pathway in resistance of Arabidopsis thaliana against molluscan herbivores. Mol Ecol 23: 1188–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkier BA, Gershenzon J (2006) Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 303–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara-Nishimura I, Matsushima R (2003) A wound-inducible organelle derived from endoplasmic reticulum: A plant strategy against environmental stresses? Curr Opin Plant Biol 6: 583–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Yamada K, Shimada T, Matsushima R, Nishizawa NK, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2001) A proteinase-storing body that prepares for cell death or stresses in the epidermal cells of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 894–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen T-H. (1970) Cytochemical localization of myrosinase (β-thioglucosidase) in root tips of Sinapis alba. Protoplasma 71: 451–466 [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva OA, Gibson TM, Cramer R, Stain C (2010) Glucosinolate-accumulating S-cells in Arabidopsis leaves and flower stalks undergo programmed cell death at early stages of differentiation. Plant J 64: 456–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzeri L, Curto G, Leoni O, Dallavalle E (2004) Effects of glucosinolates and their enzymatic hydrolysis products via myrosinase on the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita (Kofoid et White) Chitw. J Agric Food Chem 52: 6703–6707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthy B, Matile P (1984) The mustard oil bomb: Rectified analysis of the subcellular organisation of the myrosinase system. Biochem Physiol Pflanz 179: 5–12 [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R, Hayashi Y, Kondo M, Shimada T, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2002) An endoplasmic reticulum-derived structure that is induced under stress conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 130: 1807–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R, Hayashi Y, Yamada K, Shimada T, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2003a) The ER body, a novel endoplasmic reticulum-derived structure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol 44: 661–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R, Kondo M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2003b) A novel ER-derived compartment, the ER body, selectively accumulates a β-glucosidase with an ER-retention signal in Arabidopsis. Plant J 33: 493–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R, Fukao Y, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2004) NAI1 gene encodes a basic-helix-loop-helix-type putative transcription factor that regulates the formation of an endoplasmic reticulum-derived structure, the ER body. Plant Cell 16: 1536–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi N, Shimada T, Mano S, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2000) Characterization of organelles in the vacuolar-sorting pathway by visualization with GFP in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant Cell Physiol 41: 993–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller R, de Vos M, Sun JY, Sønderby IE, Halkier BA, Wittstock U, Jander G (2010) Differential effects of indole and aliphatic glucosinolates on lepidopteran herbivores. J Chem Ecol 36: 905–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Mano S, Tanaka Y, Ohnishi M, Nakamori C, Araki M, Niwa T, Nishimura M, Kaminaka H, Nakagawa T, et al. (2010) Gateway binary vectors with the bialaphos resistance gene, bar, as a selection marker for plant transformation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 74: 1315–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano RT, Yamada K, Bednarek P, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2014) ER bodies in plants of the Brassicales order: Biogenesis and association with innate immunity. Front Plant Sci 5: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano RT, Piślewska-Bednarek M, Yamada K, Edger PP, Miyahara M, Kondo M, Böttcher C, Mori M, Nishimura M, Schulze-Lefert P, et al. (2017) PYK10 myrosinase reveals a functional coordination between endoplasmic reticulum bodies and glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 89: 204–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nintemann SJ, Hunziker P, Andersen TG, Schulz A, Burow M, Halkier BA (2018) Localization of the glucosinolate biosynthetic enzymes reveals distinct spatial patterns for the biosynthesis of indole and aliphatic glucosinolates. Physiol Plant 163: 138–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noret N, Meerts P, Tolrà R, Poschenrieder C, Barceló J, Escarre J (2005) Palatability of Thlaspi caerulescens for snails: Influence of zinc and glucosinolates. New Phytol 165: 763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara K, Yamada K, Christeller JT, Kondo M, Hatsugai N, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M (2009) Constitutive and inducible ER bodies of Arabidopsis thaliana accumulate distinct β-glucosidases. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 480–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rask L, Andréasson E, Ekbom B, Eriksson S, Pontoppidan B, Meijer J (2000) Myrosinase: Gene family evolution and herbivore defense in Brassicaceae. Plant Mol Biol 42: 93–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y, Tsukaya H, Li Y, Sato M, Kawade K, Hirai MY (2017) A novel method for single-grain-based metabolic profiling of Arabidopsis seed. Metabolomics 13: 75 [Google Scholar]

- Shroff R, Vergara F, Muck A, Svatoš A, Gershenzon J (2008) Nonuniform distribution of glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves has important consequences for plant defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 6196–6201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderby IE, Burow M, Rowe HC, Kliebenstein DJ, Halkier BA (2010) A complex interplay of three R2R3 MYB transcription factors determines the profile of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 153: 348–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JY, Sønderby IE, Halkier BA, Jander G, de Vos M (2009) Non-volatile intact indole glucosinolates are host recognition cues for ovipositing Plutella xylostella. J Chem Ecol 35: 1427–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H, Nishiyama C, Shimada T, Koumoto Y, Hayashi Y, Kondo M, Takahashi T, Ohtomo I, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2006) AtVAM3 is required for normal specification of idioblasts, myrosin cells. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 164–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Escamilla-Treviño L, Zeng L, Lalgondar M, Bevan D, Winkel B, Mohamed A, Cheng C-L, Shih M-C, Poulton J, et al. (2004) Functional genomic analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana glycoside hydrolase family 1. Plant Mol Biol 55: 343–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Nagano AJ, Nishina M, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M (2008) NAI2 is an endoplasmic reticulum body component that enables ER body formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 20: 2529–2540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Nagano AJ, Ogasawara K, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M (2009) The ER body, a new organelle in Arabidopsis thaliana, requires NAI2 for its formation and accumulates specific β-glucosidases. Plant Signal Behav 4: 849–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M (2011) Unique defense strategy by the endoplasmic reticulum body in plants. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 2039–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Nagano AJ, Nishina M, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M (2013) Identification of two novel endoplasmic reticulum body-specific integral membrane proteins. Plant Physiol 161: 108–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]