Kimura et al. show that Sox8 is specifically expressed in intestinal M cells. Genetic deletion of Sox8 causes the loss of mature M cells and reduction of antigen uptake in Peyer’s patches, resulting in a decreased antigen-specific IgA response during the mouse juvenile period.

Abstract

Microfold (M) cells residing in the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue are specialized for antigen uptake to initiate mucosal immune responses. The molecular machinery and biological significance of M cell differentiation, however, remain to be fully elucidated. Here, we demonstrate that Sox8, a member of the SRY-related HMG box transcription factor family, is specifically expressed by M cells in the intestinal epithelium. The expression of Sox8 requires activation of RANKL-RelB signaling. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and luciferase assays revealed that Sox8 directly binds the promoter region of Gp2 to increase Gp2 expression, which is the hallmark of functionally mature M cells. Furthermore, genetic deletion of Sox8 causes a marked decrease in the number of mature M cells, resulting in reduced antigen uptake in Peyer’s patches. Consequently, juvenile Sox8-deficient mice showed attenuated germinal center reactions and antigen-specific IgA responses. These findings indicate that Sox8 plays an essential role in the development of M cells to establish mucosal immune responses.

Introduction

The mucosal surface of the intestinal tract is constantly exposed to antigens consumed with food, potentially harmful foreign pathogens, and antigens derived from symbiotic bacteria. The gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is an inductive site for mucosal immune responses against these mucosal antigens and thereby contributes to immunosurveillance on the mucosal surface. The dome-shaped follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) covering the luminal surface of GALT is characterized by the presence of microfold or membranous epithelial cells, termed M cells (Owen, 1999; Mabbott et al., 2013). M cells actively transport macromolecules and microorganisms from the intestinal lumen into the subepithelial region via a transepithelial pathway; this process is known as antigen transcytosis (Bockman and Cooper, 1973; Owen, 1977; Neutra et al., 1987). The luminal antigens are transferred by M cells to immature dendritic cells (DCs) that accumulate at the subepithelial dome region; subsequently, the immature DCs undergo maturation and, in turn, activate antigen-specific naive T cells. Thus, M cell–dependent antigen transcytosis may play a key role in the induction of mucosal immune responses to certain antigens. Indeed, we have previously shown that the absence of M cells or their antigen uptake receptor glycoprotein 2 (GP2) attenuates antigen-specific T cell responses in mice orally infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium due to a decrease in bacterial uptake to Peyer’s patches (PPs; Hase et al., 2009a; Kanaya et al., 2012). Analogously, dysfunction of transcytosis due to the absence of Aif1 reduces the uptake of Yersinia enterocolitica in PPs (Kishikawa et al., 2017). These defects in M cell–dependent antigen uptake have been shown to eventually diminish the production of antigen-specific secretory IgA (S-IgA) in the gut (Hase et al., 2009a; Rios et al., 2016; Kishikawa et al., 2017). These observations demonstrate that M cells play a critical role in the onset of mucosal immune responses.

M cells are derived from intestinal stem cells upon stimulation by the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL; Knoop et al., 2009; de Lau et al., 2012). The stem/progenitor cells residing at the FAE-associated crypts are continuously exposed to RANKL secreted from specialized stromal cells termed M cell inducer (MCi) cells (Nagashima et al., 2017). RANKL binds to its receptor RANK on intestinal stem/progenitor cells to activate TRAF6, an intracellular adaptor molecule of RANK, leading to activation of both canonical and noncanonical NF-κB signaling pathways (Walsh and Choi, 2014). The canonical NF-κB pathway mainly mediates the activation of the p50/RelA heterodimer, whereas the noncanonical pathway mediates p52/RelB activation (Shih et al., 2011). We previously demonstrated that p50/RelA is essential for M cell lineage commitment as well as for FAE formation (Kanaya et al., 2018). Furthermore, the noncanonical NF-κB signaling molecule, p52/RelB, up-regulates Spi-B, which is an Ets family transcription factor essential for the differentiation of M cells (de Lau et al., 2012; Kanaya et al., 2012; Sato et al., 2013). Newly generated Spi-B+ M cells lack GP2 expression and exhibit an immature phenotype. These cells terminally differentiate into functionally mature Spi-B+GP2high M cells during migration from the FAE-associated crypts into the dome region (Kimura et al., 2015). The expression of Spi-B and both NF-κB transcription factors, p50/RelA and p52/RelB, is necessary, but not sufficient, for complete M cell differentiation, especially in terms of the expression of Gp2 (de Lau et al., 2012; Kanaya et al., 2012, 2018; Sato et al., 2013); therefore, the molecular machinery involved in the M cell maturation process remains incompletely understood. This raises the possibility that additional factors activated by the RANKL–RANK pathway are required to induce full maturation of M cells.

Here, we identify Sox8 as an additional regulator essential for the differentiation of M cells. Sox8 was specifically expressed in Spi-B+ M cells; this expression was intact even in the absence of Spi-B and dependent on RANKL/RANK-RelB signaling. Sox8 plays a nonredundant role in M cell differentiation by enhancing promoter activity of Gp2. Notably, Sox8 deficiency mitigated antigen sampling and germinal center (GC) reaction in PPs. As a result, IgA+ B cells in PPs as well as commensal-specific S-IgA in feces were significantly decreased in Sox8-deficient mice compared with that in control littermates. These observations demonstrate that Sox8 is a novel player essential for the differentiation of M cells and antigen-specific IgA response in the gut.

Results

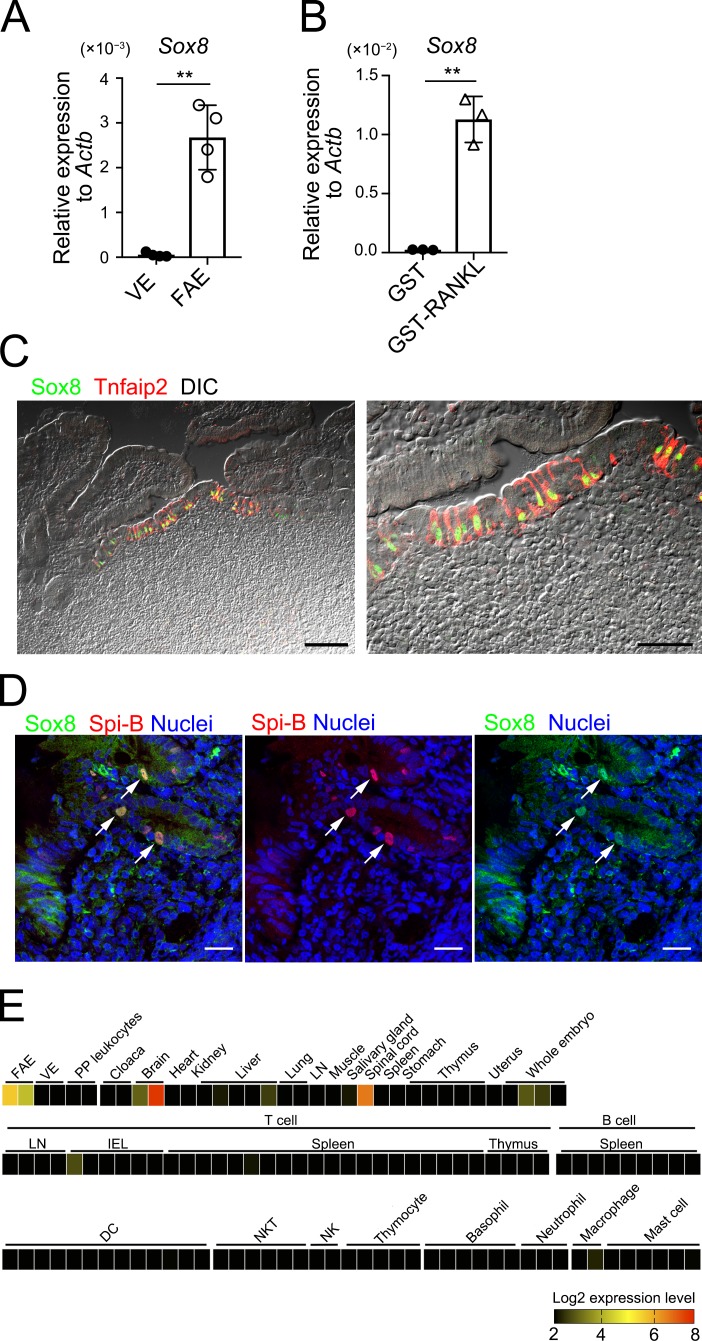

Sox8 is expressed in M cells via RANKL signaling

To identify the transcription factors that potentially regulate the development and functionality of M cells, we analyzed three different transcriptome datasets profiling murine M cell–specific gene candidates (Hase et al., 2005; de Lau et al., 2012; Kanaya et al., 2012). Sox8, which encodes a member of the SRY-related HMG-box family of transcription factors, was one of the genes enriched in the M-cell fraction in all three datasets. The present quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis confirmed that Sox8 is exclusively expressed in the murine FAE but not in the villus epithelium (VE; Fig. 1 A). Intraperitoneal administration of recombinant glutathione S-transferase–RANKL (GST-RANKL) induces the expression of FAE/M cell–associated genes in the VE, resulting in the formation of ectopic M cells (Knoop et al., 2009). Likewise, Sox8 expression was greatly up-regulated in VE upon treatment with GST-RANKL (Fig. 1 B). Immunofluorescence analysis of murine PPs also revealed that Sox8 is localized in the nuclei of FAE cells expressing Tnfaip2, which is a cytosolic protein unique to M cells (Fig. 1 C; Hase et al., 2009b; Kimura et al., 2015). Sox8 was also expressed in M cells throughout mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), including in the cecal patches, nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue of mouse, and human PPs (Fig. S1, A, B, and D). No immunoreactive signals were observed for Sox8 in the subepithelial dome region, follicle, and the lamina propria (Fig. 1 C). Comprehensive analysis using RefDIC, a microarray database for various tissues and immune cells (Hijikata et al., 2007), also confirmed that Sox8 is highly expressed in FAE but rarely in any immune cell subsets (Fig. 1 E).

Figure 1.

Sox8 is a transcription factor whose expression in M cells is mediated by RANKL. (A) qPCR analysis of Sox8 in the FAE of PPs and VE. Results are presented relative to the expression of Actb. Values are presented as the mean ± SD (Student’s t test; n = 4; **, P < 0.01). (B) qPCR analysis of the VE from GST-RANKL–treated or GST-treated mice. Results are presented relative to the expression of Actb. Values are presented as the mean ± SD (Student’s t test; n = 3; **, P < 0.01). Data are representative of two independent experiments (A and B). (C) Immunofluorescence of the FAE of murine PPs for Sox8 (green) and Tnfaip2 (red). The right panel is an enlarged view of the left panel. Bars, 100 µm (left); 50 µm (right). (D) Immunohistochemistry for Spi-B (red) and Sox8 (green) of human biopsy samples of PP collected from healthy small intestinal tissues. Bars, 20 µm. C and D show representative images from at least two independent experiments, respectively. (E) Expression of mouse Sox8 was analyzed using the RefDIC microarray database. Detailed conditions of cell preparation and treatment are available on the RefDIC web site. DIC, differential interference contrast; IEL, intraepithelial lymphocyte; NK, natural killer cell; NKT, natural killer T cell.

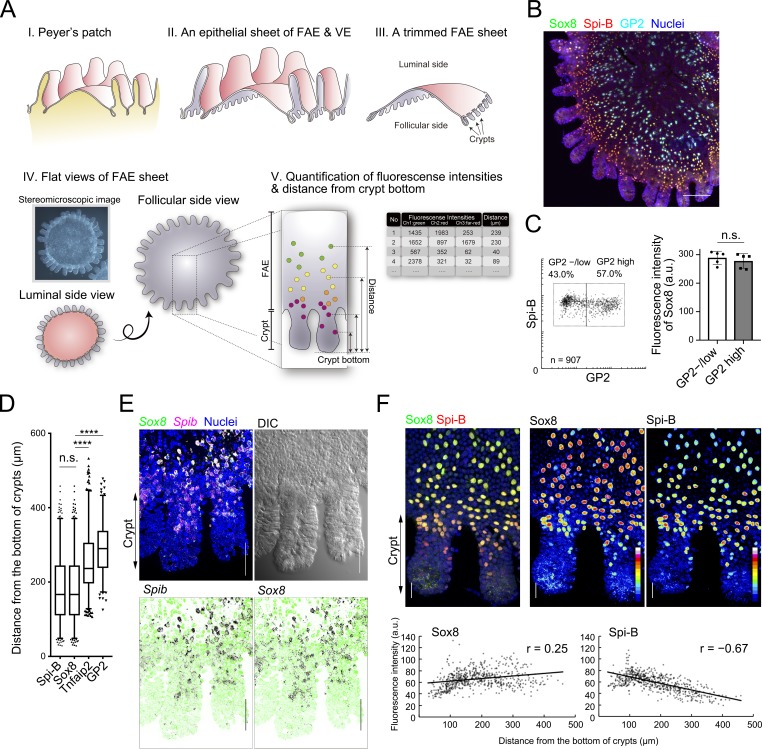

Sox8 is constitutively expressed during the development of M cells

We previously defined GP2 as a terminal differentiation marker of M cells; Spi-B+GP2high cells are considered as mature M cells that vigorously take up luminal antigens and Spi-B+GP2–/low cells as immature M cells with lower uptake capacity (Kimura et al., 2015). Whole-mount immunofluorescence staining, followed by quantitative image cytometry (Fig. 2 A), revealed that Sox8 is expressed homogeneously in both immature and mature M cells (Fig. 2, B and C; and Fig. S2 A). On the other hand, the fluorescence intensity of Spi-B was higher in the former than in the latter cells (Fig. S2 B).

Figure 2.

M cells constitutively express Sox8 during differentiation. (A) A sketch of the workflow for whole-mount preparation of FAE for image cytometric analysis. I: A fresh PP is excised with surrounding villus from the murine intestine. II: An FAE with VE is peeled off from follicles after EDTA treatment. III: The FAE is trimmed with razor or knife under stereomicroscopy. IV: A trimmed FAE sheet is fixed and used for immunostaining or in situ hybridization. The stained FAE is usually observed from the follicular side by confocal microscopy. V: Fluorescence intensities and the distance from the crypt bottom of each cell are measured. (B) Whole-mount immunostaining of the FAE of PPs for Sox8 (green), Spi-B (red), and GP2 (cyan). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Bar, 100 µm. Images of each channel are shown in Fig. S2. (C) The left panel shows a scatter plot of the fluorescence intensities of Sox8 versus GP2, where each dot represents a single cell. Lowercase n indicates the number of analyzed cells. The right panel shows the mean values of Sox8 fluorescence intensities in GP2high and GP2−/low cells. Error bars indicate SD. n = 907. Data were obtained from five FAE images from two independent experiments, and a representative image is shown in B. (D) Box plots depicting the distribution of M cell markers as their distances from the bottom of crypts. The two whisker boundaries are 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. Symbols are outliers; ****, P < 0.0001; n.s., not significant; Kruskal-Wallis test multiple comparisons, n = 634 (Spi-B), 634 (Sox8), 563 (Tnfaip2), and 315 (GP2) from at least five images. (E) Whole-mount FISH images of FAE-associated crypts using specific oligonucleotide probes for Sox8 (green) and Spib (red) are shown. Bars, 20 µm. Each FISH image is shown separately with DAPI (green) in lower panel. Black dots indicate the position of mRNA. Images were representative of at least two independent experiments. (F) Upper panels: High-magnified images of FAE-associated crypts from the whole-mount immunostaining image. Fluorescence intensity of Sox8 and Spi-B immunostaining are shown as pseudo color. Bars, 20 µm. Lower panels: Correlation plots of fluorescence intensity of Sox8 or Spi-B immunostaining with the distance of each cell from the bottom of crypts. Images were representatives of at least two independent experiments. a.u., arbitrary units; DIC, differential interference contrast; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Because M cell progenitors generated from intestinal stem cells at the crypt base migrate upward along the crypt–FAE axis, mature M cells are detectable at the middle regions of the dome (Sierro et al., 2000; Kimura et al., 2015). Therefore, the distances from the crypt bottom to the migrating cells correlate well with the maturity of the cells in the FAE (Fig. S2 C). The spatial distribution of Sox8+ cells was identical to that of Spi-B and closer to the crypts than Tnfaip2 and GP2 (Fig. 2 D). These data indicate that Sox8 is expressed from the early stage of M cell differentiation, in line with Spi-B expression. The early expression of Sox8 with Spib in the lower/middle region of crypt was further corroborated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (Fig. 2 E). In accordance with down-regulation of Spi-B in GP2high cells (Fig. S2 B), the expression level of Spi-B gradually declined along the crypts–dome axis, whereas that of Sox8 was maintained virtually intact or slightly increased (Fig. 2 F).

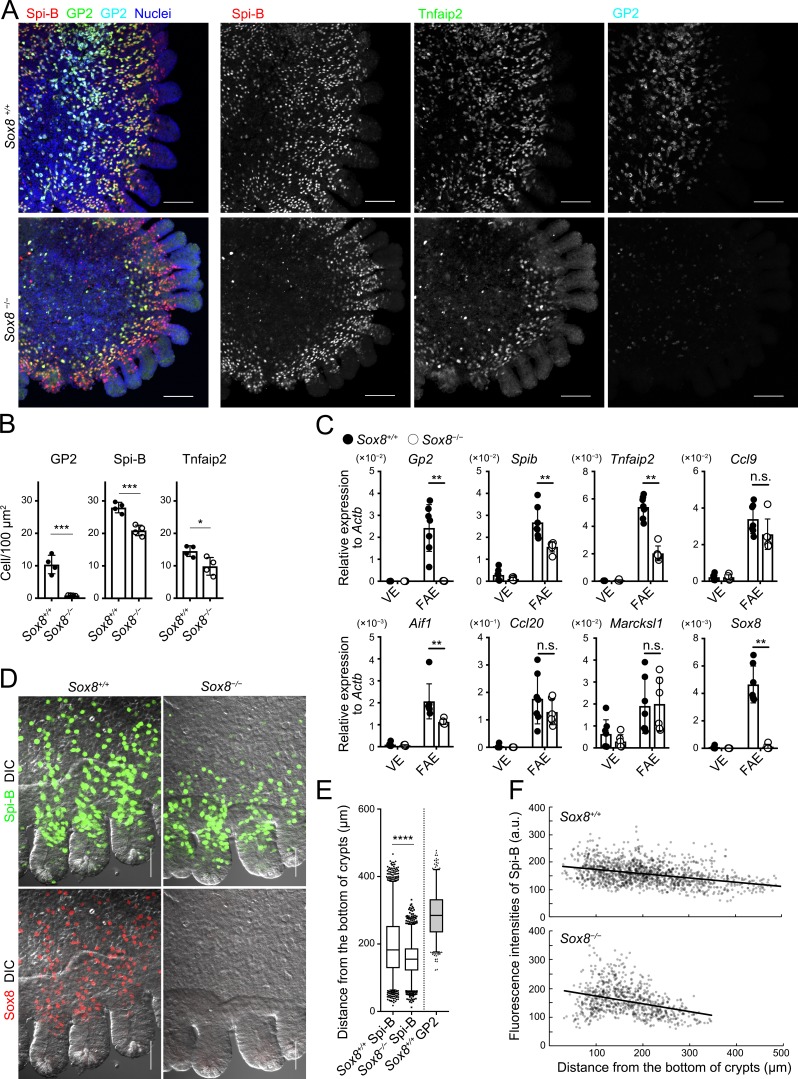

Sox8 is required for maturation of M cells

Given the spatiotemporal expression of Sox8 in M cells, we postulated that Sox8 may contribute to the development of M cells. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed PPs of Sox8-deficient (Sox8−/−) mice. Notably, we detected few, if any, GP2+ M cells in the FAE of Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 3 A), counting 10.4 ± 2.85 cells/100 µm2 and 0.85 ± 0.09 cells/100 µm2 in Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice, respectively (Fig. 3 B). On the other hand, the numbers of Spi-B+ cells and Tnfaip2+ cells were modestly decreased in PPs of Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 3 B). These observations indicate that Sox8 plays an essential role in the full maturation of M cells.

Figure 3.

The loss of Sox8 decreases the number of mature M cells in the FAE. (A) Whole-mount immunostaining images for Spi-B (red), Tnfaip2 (green), and GP2 (cyan) of the FAE of PPs from Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice. Bars, 100 µm. (B) Quantification of GP2-, Spi-B-, and Tnfaip2-positive cells in the FAE and FAE-associated crypts. ***, P < 0.005; *, P < 0.05; Student’s t test, n = 4. (C) qPCR analysis of M cell–associated genes in the FAE and VE of Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice. **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, n = 7 from Sox8+/+ mice, n = 6 from Sox8−/− mice. (D) High-magnification images of the FAE including associated crypts from Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice. Bars, 50 µm. (E) Box plots depicting the distribution of M-cell markers as their distances from the bottom of crypts. The two whisker boundaries are 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. Symbols are outliers; ****, P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney test, n = 2,704, Spi-B–positive cells in Sox8+/+ mice; n = 2,077, Spi-B–positive cells in Sox8−/− mice; n = 798, GP2-positive cells in Sox8+/+ mice from two independent experiments. (F) Correlation plots of fluorescence intensity of Spi-B immunostaining with the distance of each cell from the bottom of crypts. Data are representative (A and D–F) or mean (B and C) of two independent experiments. a.u., arbitrary units; DIC, differential interference contrast. All values are presented as the mean ± SD.

To identify the downstream target genes of Sox8 and Spi-B, we performed comparative transcriptome analysis of FAE from Sox8−/−, Spib−/−, and corresponding control mice. The findings showed that Sox8 or Spib deficiency resulted in the significant down-regulation of 114 or 359 genes, respectively (Fig. S3, A and B; Table S2; and Table S3). Among these, 41 genes were commonly down-regulated (Fig. S3B). We further narrowed the 41 genes down to 17 genes by their fold changes, with over twofold lower expression in both Sox8−/− and Spib−/− mice compared with that in corresponding controls (Fig. S3 C). Interestingly, Gp2 was among the commonly down-regulated genes. Sox8 was considered to regulate relatively limited numbers of M cell–associated genes compared with Spi-B (Fig. S3 B).

The genes listed include stromal cell–associated (e.g., Col5a1, Col4a2, Madcam-1, Cxcl13, and Bgn) and hematopoietic cell–associated molecules (e.g., Cxcr5, Cd22, Il21r, and Ltb), implying contamination of these cells in the FAE samples. We conducted qPCR analysis. In accordance with the transcriptome analysis, qPCR analysis showed that the expression level of Gp2 in the FAE of Sox8−/− mice was prominently lower than in that of Sox8+/+ mice (Fig. 3 C). Furthermore, the expression levels of Spib, Tnfaip2, and Aif1 were moderately, but significantly, decreased in Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 3 C). A similar tendency was also observed in terms of Ccl9 expression. However, the early M cell differentiation markers, Ccl20 and Marcksl1, were unchanged (Fig. 3 C). Topographically, the maturation levels of M cells closely correlated with the distance from the crypt bottom (Fig. S2 C). Spi-B+ cells in Sox8+/+ mice were observed to be present continuously from the lower/middle region of crypts to the middle region of the FAE, whereas Spi-B+ cells in Sox8−/− mice were localized only up to the peripheral region of the FAE dome, being rare in the middle region of the FAE (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, D–F). These observations suggest that Sox8 contributes to the development of late-stage M cells rather than early commitment to M cells. Further, the modest reductions in the number of Tnfaip2+ cells and Spi-B+ cells of Sox8−/− mice may be attributable to impairment of the M cell maturation process (Fig. 3 B).

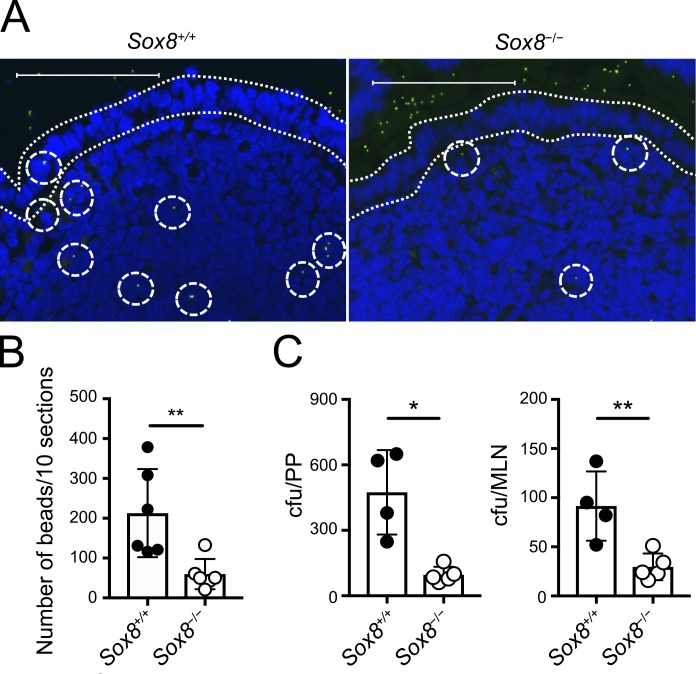

GP2+ M cells are known to vigorously take up luminal macromolecules, and GP2 serves as an uptake receptor for a subset of commensal and pathogenic bacteria such as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium; Hase et al., 2009a; Kimura et al., 2015). Therefore, we examined these functions in Sox8−/− mice. Fluorescent nanoparticles were orally administrated, and incorporation into PPs via M cells was evaluated. The number of nanoparticles in PPs of Sox8−/− mice was much lower than in those of Sox8+/+ mice (Fig. 4, A and B). Similarly, translocation of S. Typhimurium aroA mutant strain from the lumen to PPs and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) significantly decreased in Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 4 C; Fairweather et al., 1990). Collectively, these data illustrate that Sox8 is the master regulator of functional maturation in M cells.

Figure 4.

The loss of Sox8 causes decreased uptake of luminal nanoparticles into the follicle. (A and B) Green fluorescent latex beads (200-nm diameter) were orally administered to Sox8+/+ or Sox8−/− mice. 3 h later, two PPs were collected from the jejunum. Cryosections of PPs were examined by fluorescence microscopy, and the number of particles was counted manually. (A) Representative images of cryosections. Dotted lines indicate FAE. Dotted circles indicate fluorescent particles. Bars, 100 µm. (B) Quantification of particles in PPs. **, P < 0.01; Student’s t test; n = 6 per genotype. (C) Mice were orally infected with 5 × 108 CFU of S. Typhimurium (ΔaroA); 24 h later, PPs and MLNs were collected and tissue homogenates were prepared. The colonies of culturable bacteria in the tissue homogenates were counted and are shown as colony-forming units. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test; n = 4 from Sox8+/+ mice, n = 5 from Sox8−/− mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments. All values are presented as the mean ± SD.

Epithelium-intrinsic Sox8 is responsible for M cell maturation

RANKL produced by subepithelial MCi cells is important for M cell differentiation (Nagashima et al., 2017). Therefore, to verify the possibility that Sox8 deficiency in other cells indirectly impacts M cell differentiation, we analyzed RANKL expression in PPs of Sox8−/− mice by immunofluorescence and qPCR analyses. There was no significant difference in RANKL expression in PPs between Sox8+/+ mice and Sox8−/− mice (Fig. S4, A and B).

We subsequently analyzed nuclear translocation of RelB in the FAE by whole-mount image cytometry (Fig. S4 C). RelB is an essential transcription factor downstream of RANKL-RANK signaling during M cell differentiation (Kimura et al., 2015; Kanaya et al., 2018) We found two populations of RelB-positive cells in the FAE, namely RelBint and RelBhigh cells (Fig. S4 D). The percentages of both RelB-positive cell populations were not significantly different between Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice (Fig. S4 E). These data show that Sox8 deficiency does not affect RANKL production by MCi cells or epithelial RANK-RelB signaling essential for M cell commitment.

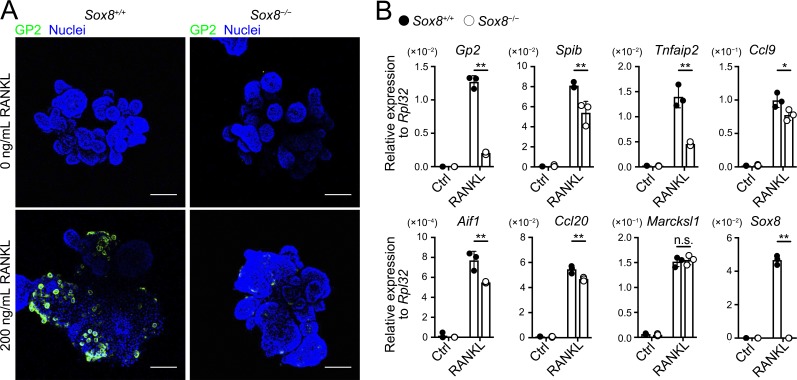

To ascertain whether the decrease in GP2+ mature M cells due to Sox8 deficiency results from the epithelium-intrinsic defect, we prepared intestinal organoid culture from Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice and induced M cells via stimulation with RANKL. As expected, GP2+ cells were rarely detected in Sox8−/− organoids (Fig. 5 A). Likewise, Gp2 transcripts were nearly absent in Sox8−/− organoids, whereas the expression of other M cell–associated genes was only moderately decreased or unchanged (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

Defect in M cell maturation in Sox8−/− results from epithelium-intrinsic defect. (A and B) Organoids from small intestinal crypts of Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice were cultured with or without RANKL for 3 d. (A) Immunostaining images for GP2 (green) on organoids. Bars, 100 µm. (B) qPCR analysis of M cell–associated genes expressed in the organoid cultures. Values are presented as the mean ± SD; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, n = 3. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

The induction of IgA response is delayed in Sox8−/− mice

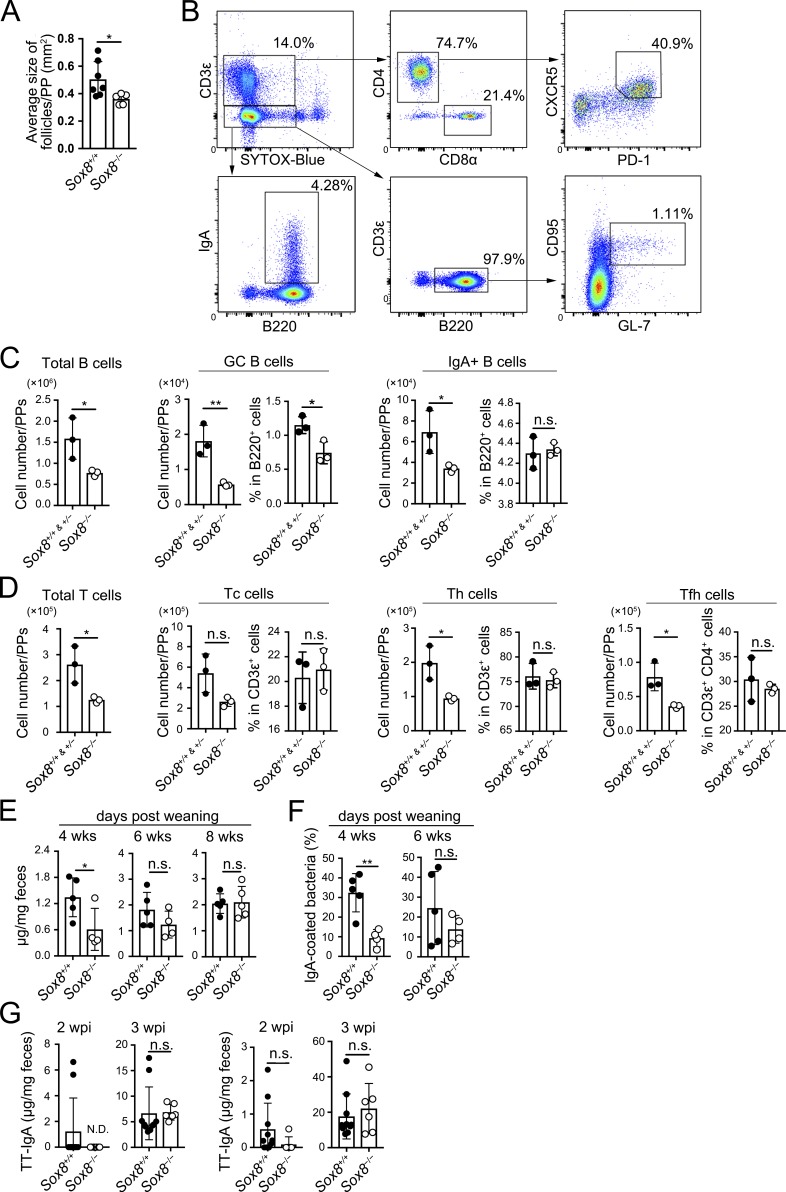

We further explored the biological significance of Sox8-dependent M cell maturation in the mucosal immune system. PPs continuously undergo GC reactions, including class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation, to generate high-affinity IgA+ B cells (Muramatsu et al., 2000; Kawamoto et al., 2012). GC in rodent PPs develops rapidly after weaning (Sminia et al., 1983; Kramer and Cebra, 1995). We observed that the size of lymphoid follicles decreased in the PPs of Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 6 A). We also found that the numbers of B and T cells reduced to approximately half compared with those in Sox8+/+ mice at 4 wk of age (Fig. 6, B–D). Importantly, the number of GC B cells as well as follicular helper T (Tfh) cells was also remarkably decreased in Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 6, C and D). Tfh cells in the PPs promote GC reactions and affinity maturation to generate high-affinity IgA (Tsuji et al., 2009). Correspondingly, IgA class-switched B cells were found to have declined in number in the PPs of Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 6 C). On the other hand, these defects were not observed at 6 wk of age (Fig. S5, A and B).

Figure 6.

The loss of Sox8 causes delay in the production of symbiotic bacteria-specific IgA antibody after weaning. (A) Follicle size of PPs measured by stereomicroscope; *, P < 0.05; Student’s t test; n = 7 from Sox8+/+ mice, n = 5 from Sox8−/− mice. (B) The gating strategy to analyze the B and T cell populations in ileal PPs. B (CD3ε−B220+) cells were analyzed for IgA+ B and CD95+GL7+ GC B cells. T (CD3ε+B220−) cells were analyzed for total CD4+ Th, CD8α+ cytotoxic T (Tc), and CD4+CD8α−CXCR5+PD-1+ Tfh cells. (C and D) Flow cytometry analysis of indicated immune cells in ileal PPs. (C) Number of total B cells, GC B cells, and IgA+ B cells. (D) Number of total T cells, Tc cells, Th cells, and Tfh cells; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant; Student’s t test, n = 3 per group. (E) Fecal IgA concentration measured by ELISA; *, P < 0.05; Student’s t test; n = 5 from Sox8+/+ mice, n = 4 from Sox8−/− mice (4 and 6 wk old); n = 5 per group (8 wk old). (F) Flow cytometry analysis of IgA-coated bacteria in feces; **, P < 0.01; Student’s t test; n = 5 from Sox8+/+ mice, n = 4 from Sox8−/− mice. (G) Mice were orally infected with 5 × 107 CFU of rSalmonella-ToxC. The presence of TT-specific IgA in feces and IgG in serum at 2 and 3 wk after immunization were evaluated by ELISA; Student’s t test; n = 10 from Sox8+/+ mice, n = 6 from Sox8−/− mice. Data are representative (B–F) or means (A and G) of two independent experiments. wpi, weeks post-immunization. All values are presented as the mean ± SD.

We additionally observed that the concentration of fecal S-IgA was significantly reduced in Sox8−/− mice at 4 wk old (Fig. 6 E) but was comparable between Sox8−/− and Sox8+/+ mice after 6 wk of age. A large proportion of the fecal S-IgA repertoire is directed against antigens present on gut commensal bacteria (Benckert et al., 2011; Mantis et al., 2011). To detect commensal-specific S-IgA, we performed bacterial flow cytometry on fecal suspension using a labeled secondary anti-IgA antibody. The amount of commensal-specific IgA was reduced in 4-wk-old, but not in 6-wk-old, Sox8−/− mice (Fig. 6 F). To further examine whether antigen-specific immunoglobulin production was affected in Sox8−/− mice, we employed a well-established oral immunization model using S. Typhimurium expressing the fragment C of the tetanus toxoid (Salmonella-ToxC), which is taken up by M cells to induce a ToxC-specific mucosal immune response in GALTs (VanCott et al., 1996; Hase et al., 2009a). The induction of antigen-specific S-IgA as well as IgG in response to ToxC was delayed in Sox8−/− mice compared with that in Sox8+/+ mice (Fig. 6 G).

Sox8 deficiency has little impact on the systemic lymphoid tissues

We further analyzed immune cell composition in major systemic lymphoid tissues of 4-wk-old mice (Fig. S5, C–G). The number of most immune cell subsets in the MLNs, spleen, and thymi was comparable between Sox8+/+ mice and Sox8−/− mice, with the exception of a slight decrease in T helper type 2 (Th2) cells in the MLNs of Sox8−/− mice. This change was associated with a significant reduction of Th2 cells in the PPs (Fig. S5 D). We also investigated whether Sox8 deficiency affected B cell class-switching and Th cell differentiation using an in vitro culture system. B cell class-switching to IgA, IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a was intact in the absence of Sox8 (Fig. S5 H). Although the frequency of GATA3+ Th2 cells was slightly affected, the other T cell subsets, namely T-bet+ Th1, RORγt+ Th17, and Foxp3+ regulatory T (T reg) cells, exhibited normal development without Sox8 (Fig. S5 H). These data suggest that B or T cell–intrinsic Sox8 deficiency has minimal, if any, impact on the differentiation of B and T cell populations.

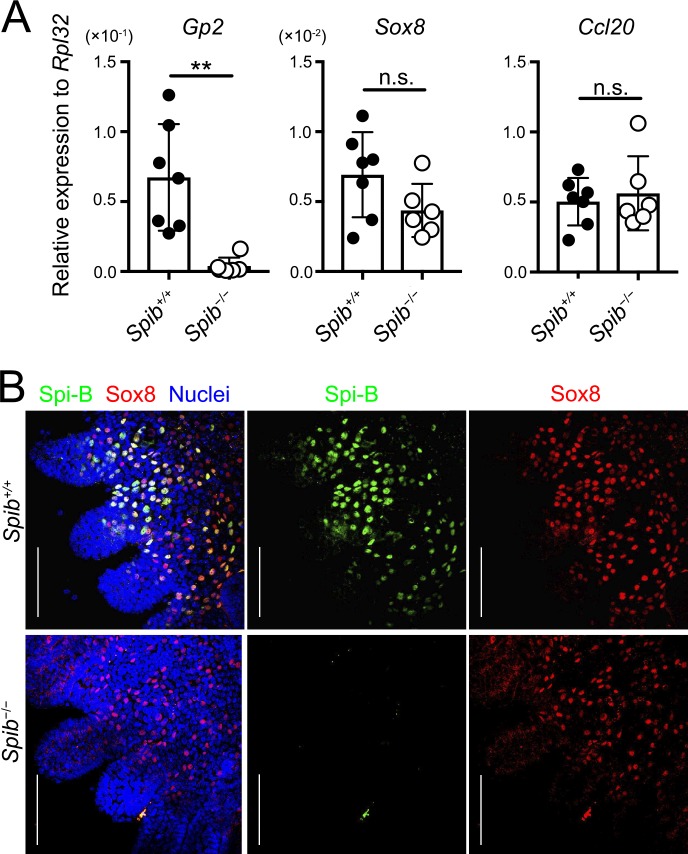

Spi-B is dispensable for Sox8 expression

Spi-B, which is a key transcription factor involved in M cell differentiation, regulates the expression of several M cell–associated genes (de Lau et al., 2012; Kanaya et al., 2012; Sato et al., 2013). RNA sequencing analysis revealed a decrease in the expression of Sox8 in the FAE of Spib−/− mice (Table S3). qPCR analysis also confirmed that Sox8 expression tended to decrease in Spib−/− mice (Fig. 7 A). Consistent with previous studies, we confirmed a marked reduction in Gp2 expression in Spib−/− mice by qPCR and RNA sequencing (Fig. 7 B and Table S3; de Lau et al., 2012; Kanaya et al., 2012; Sato et al., 2013). Ccl20 (an FAE marker) expression remained intact in Spib−/− mice. To further clarify whether Sox8 expression is regulated by Spi-B, we analyzed PPs of Spib−/− mice by a whole-mount immunofluorescence technique. The immunoreactivity of Sox8 on the FAE was retained despite the absence of Spi-B (Fig. 7 B).

Figure 7.

Spi-B is dispensable for Sox8 expression. (A) qPCR analysis of M cell–associated genes expressed in the FAE of PPs. Values are presented as the mean ± SD; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test; n = 7 from Spib+/+ mice, n = 6 from Spib−/− mice. (B) Whole-mount immunostaining images for Sox8 (red) and Spi-B (green) of the FAE of PPs from Spib+/+ and Spib−/− mice. Bars, 100 µm. Data are means (A) or representative (B) of two independent experiments.

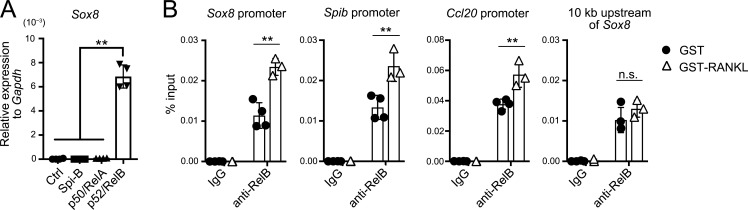

Sox8 expression is mediated by the noncanonical NF-κB pathway

We subsequently examined the role of canonical (p50/RelA) and noncanonical (p52/RelB) NF-κB pathways downstream of RANK in the expression of Sox8. To this end, we used intestinal organoid culture, which enables the induction of M cells in vitro upon exposure to RANKL (de Lau et al., 2012; Wood et al., 2016). Introduction of p52 and RelB into the intestinal organoids with lentivirus coding p52 and RelB prominently up-regulated Sox8 transcript levels (Fig. 8 A). In sharp contrast, exogenous expression of p50 and RelA failed to increase Sox8 expression. These data clearly suggested that noncanonical, but not canonical, NF-κB signaling contributes to Sox8 expression. Exogenous expression of Spi-B also did not affect Sox8 expression (Fig. 8 A).

Figure 8.

Sox8 expression is regulated by p52/RelB. (A) qPCR analysis of mouse small intestinal organoids exposed to lentivirus encoding transcription factors. The expression of Sox8 was presented relative to that of Gapdh. **, P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, n = 4. (B) Anti–RelB ChIP analysis of the VE from GST-RANKL–treated or GST-treated mice. Immunoprecipitated Sox8, Spib, and Ccl20 promoter regions were examined by qPCR analysis. The 10-kb upstream region of Sox8, which lacks NF-κB binding sequence, was used as a negative control. **, P < 0.01; n.s. not significant; two-way ANOVA; n = 4 from GST-treated mice, n = 3 from GST-RANKL–treated mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Ctrl, control. All values are presented as the mean ± SD.

To consolidate the contribution of noncanonical NF-κB to Sox8 expression, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay using anti-RelB antibodies. To obtain a sufficient amount of M cell–derived genomic DNA for the assay, we ectopically induced M cells in the VE by administration of GST-RANKL (Knoop et al., 2009). Mice treated with GST were used as a negative control. The ChIP assay demonstrated the association of RelB with the Sox8 promoter region; this association was significantly enhanced in the VE from the GST-RANKL–treated group (Fig. 8 B). Further, the binding of RelB to the 10-kb upstream region of Sox8, which lacks NF-κB binding sites, was not affected by the GST-RANKL treatment. In addition, the recruitment of RelB to Spib and Ccl20 promoter regions was also amplified significantly in the presence of GST-RANKL (Fig. 8 B). These data imply that p52/RelB directly transactivates M cell–specific genes, including Sox8, by interacting with their promoter regions.

Gp2 is a direct target of Sox8

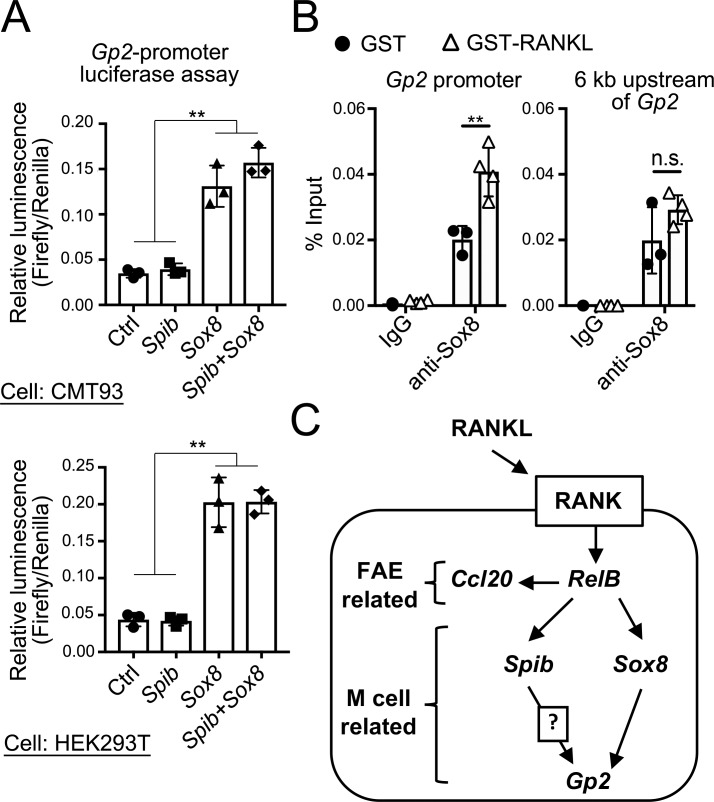

We aimed to elucidate the mode of action by which Sox8 induces the mature M cell marker, Gp2. The luciferase assay results indicated that overexpression of Sox8 prominently enhanced Gp2 promoter activity in a murine intestinal epithelial cell line, CMT-93, and in human embryonic kidney cells (Fig. 9 A). In contrast, overexpression of Spi-B alone or in combination with Sox8 failed to increase the Gp2 promoter activity (Fig. 9 A). Furthermore, ChIP-qPCR of the intestinal epithelium verified the specific binding of Sox8 to the Gp2 promoter region, which includes putative Sox8-binding motifs, upon treatment with RANKL to induce M cells (Fig. 9 B). However, such specific binding was not observed in the 6-kb upstream region devoid of Sox8-binding motifs.

Figure 9.

Sox8 is a transcription factor responsible for Gp2 expression. (A) Luciferase assay in CMT93 or 293T cells using Gp2 promoter–driven reporter plasmid (Firefly luciferase). Cells were cotransfected with expression vector of Sox8 or Spib or a combination of Sox8 and Spib. Luciferase activity was normalized to that of the cotransfected Renilla luciferase expression vector; **, P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, n = 3. (B) Anti–Sox8 ChIP analysis of the VE from GST-RANKL–treated or GST-treated mice. The immunoprecipitated Gp2 promoter region was examined by qPCR analysis. The 6-kb upstream region, which lacks the SOX-binding sequence, was used as a negative control; **, P < 0.01; n.s. not significant; two-way ANOVA; n = 3 from GST-treated mice, n = 4 from GST-RANKL–treated mice. Data are representative of three (A) or two (B) independent experiments. (C) Proposed model of M cell differentiation. Ctrl, control. All values in A and B are presented as the mean ± SD.

Discussion

Numerous studies have revealed the molecular mechanisms involved at the early stage of M cell differentiation. However, it remains unclear how the newly differentiated immature cell type undergoes functional maturation to acquire antigen uptake and transcytosis capacities at the late stage of differentiation. Here, we identified Sox8 as a transcription factor essential for the functional maturation of M cells. Sox8, along with Sox9 and Sox10, belongs to the SOX-E subgroup of the HMG-box family of transcription factors; the members of this family are known to be master regulators of mammalian development, directing sex determination, gliogenesis, and neural crest development (Jiang et al., 2013; Weider and Wegner, 2017). Among the SOX-E subgroup, Sox9 is expressed in intestinal stem/progenitor cells and Paneth cells for the regulation of intestinal epithelial proliferation and Paneth cell differentiation, respectively (Blache et al., 2004; Bastide et al., 2007; Mori-Akiyama et al., 2007). However, little is known about the expression and function of Sox8 in the intestine. We defined the specific expression of Sox8 by M cells in human and mouse PPs. Sox8 is a prerequisite for the development of functionally mature M cells; accordingly, the genetic ablation of Sox8 resulted in attenuated antigen sampling and GC reaction in the PPs. In addition, Sox8 was commonly expressed by M cells throughout MALTs, including in the PPs, cecal patches, and nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissues, as well as RANKL-induced M cells in the VE. Such distribution, together with the phenotype in Sox8−/− mice, underscores an essential role for Sox8 in the development of functional M cells in MALTs.

The loss of functionally mature M cells due to Sox8 deficiency is reminiscent of the phenotype of Spi-B–deficient mice (Kanaya et al., 2012). Nevertheless, Spi-B deficiency marginally affected the expression of Sox8 in FAE, and, vice versa, Sox8 deficiency had only a small impact on the expression of Spib. These observations illustrate that these two master regulators appear to independently regulate M cell signature genes. In accordance with this, the transcriptome analysis demonstrated that only a small proportion of Spi-B target genes was commonly regulated by Sox8. Interestingly, the expression of Gp2 requires not only Spi-B but also Sox8, whereas the expression of middle-stage M cell markers, namely, Tnfaip2, Aif1, and Ccl9, depends on Spi-B (Kanaya et al., 2012; Kishikawa et al., 2017).

We proved that p52/RelB directly interacts with the Sox8 promoter and enhances its transcription in the organoid culture of the intestinal epithelium. Similarly, Spi-B expression is also regulated by p52/RelB (Kanaya et al., 2018). Thus, the expression of Sox8 and Spi-B is regulated in parallel downstream of RANK-p52/RelB signaling in the intestinal epithelium. A recent study showed that the Tcf4/β-catenin complex interacts with the Sox8 promoter to up-regulate gene expression in B-type spermatogonia Gc1-Spg cells stimulated with Wnt (Kataruka et al., 2017). It has been well documented that Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays a critical role in the maintenance of intestinal stemness and proliferation of transit amplifying cells (Pinto et al., 2003; Fevr et al., 2007). However, further study is required to determine whether this signaling also participates in the regulation of Sox8 in the intestinal epithelium.

GP2 is a functional marker of fully mature M cells and serves as an uptake receptor for type 1–piliated bacteria and the botulinum toxin on the surface of M cells (Hase et al., 2009a; Kimura et al., 2015; Matsumura et al., 2015). Although Spi-B is an upstream regulator for GP2 expression (de Lau et al., 2012; Kanaya et al., 2012, 2018; Sato et al., 2013), it has been shown that the forced expression of Spi-B in epithelial cell culture failed to activate Gp2 promoter and to induce Gp2 expression (de Lau et al., 2012; Kanaya et al., 2018). These data corroborate that Spi-B alone is insufficient to induce Gp2 expression. Similarly, both canonical and noncanonical NF-κB transcription factors are also essential for Gp2 expression; however, these molecules are also unlikely to directly control the expression of GP2. Therefore, a direct regulator of Gp2 remains to be identified. Our study provides evidence for the direct interaction of Sox8 with the Gp2-promoter region, leading to transactivation of the gene. Further, Spib−/− mice also lack Gp2 expression, even in the presence of Sox8. This observation suggests that Sox8 alone is also insufficient for Gp2 expression in vivo. Enhancer activation by SOX proteins requires DNA-binding partners specific for each subclass of SOX proteins to stabilize their binding to target regions (Kamachi et al., 1999). These facts suggest that a molecule downstream of Spi-B is required as the DNA-binding partner of Sox8 to induce Gp2 at the late stage of M cell differentiation (Fig. 9 C); however, further investigation is necessary to ascertain this hypothesis.

Mice carrying intestinal epithelium–specific deletion of RANK (RANKΔIEC mice) completely lack both immature and mature M cells in the FAE, resulting in impaired GC formation of PPs and a significant reduction of commensal-specific S-IgA antibodies (Rios et al., 2016). The S-IgA response in RANKΔIEC mice was nearly absent at 4–5 wk of age, after which fecal IgA production gradually increases, reaching to approximately half of that in control mice until 13 wk of age (Rios et al., 2016). In Sox8−/− mice, a significant reduction of IgA+ cells in PPs as well as commensal-specific S-IgA in feces were observed in 4-wk-old mice. This was attributed to the decrease in S-IgA production in juvenile Sox8−/− mice, which results from the diminished GC reaction, as evidenced by the decreases in GC B cells and Tfh cells. IgA production in Sox8−/− mice, however, was slightly, but not significantly, lower at 6 wk of age (68.1% of Sox8+/+ mice) but completely equal to that of Sox8+/+ mice at 8 wk of age. The number of GC B cells and Tfh cells in the PPs also recovered at 6 wk of age in Sox8−/− mice. Thus, the impaired S-IgA response is obviously less severe in Sox8−/− mice than in RANKΔIEC mice. Considering that Sox8−/− mice retain GP2−/low immature M cells, these cells may compensate for the loss of GP2high mature M cells due to Sox8 deficiency in adulthood. Indeed, the uptake of nanoparticles and S. Typhimurium to the PPs was not completely abrogated in Sox8−/− mice. An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, explanation is that direct antigen uptake by lysozyme-expressing PP DCs (LysoDCs) across FAE (Lelouard et al., 2010, 2012) may functionally compensate for the loss of mature M cells at adulthood in Sox8−/− mice. Collectively, Sox8-dependent M cell maturation significantly contributes to the induction of the S-IgA response during the juvenile period and plays a redundant role in the S-IgA response in adulthood.

In conclusion, we identified Sox8 as a key transcription factor in the late stage of M cell differentiation, which is important for immune surveillance on the mucosal surface. Identification of downstream molecules as well as association partners of Sox8 should enable the complete elucidation of the molecular mechanism underlying the functional maturation of M cells and may offer novel strategies for the development of mucosal vaccines targeting M cells as the portals of antigen entry.

Materials and methods

Antibodies against Sox8

Antibodies against Sox8 were generated in guinea pig against a purified, bacterially expressed protein consisting of amino acids 2–60 of mouse Sox8 fused to GST, according to a previous report (Stolt et al., 2005). The resulting fusion protein was emulsified with Freund’s complete adjuvant (Difco), and injected subcutaneously into a female guinea pig six times every other week (Frontier Institute). The specificity of the antibody was confirmed by immunofluorescence of tissues from Sox8-knockout mice (Fig. 3 D).

Mice

The Sox8−/− mice were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers (strain name: B6;129S7-Sox8tm1Mkob/Mmnc; stock number 030471-UNC) with a mixed 129vRv (1–15%) and C57BL6 (85–99%) background (O’Bryan et al., 2008). Sox8−/− mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice several times. Backcrossed F1-4 mice were used for gene or protein expression analysis. F3-4 mice were used for immunological analysis. The Spib−/− mice were generated as described previously (Sasaki et al., 2012). For immunological experiments, littermate mice were used as controls. For other experiments, littermates or purchased C57BL/6 mice were used as controls. The mice were maintained under conventional conditions at the animal facility of the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (IMSUT), and Hokkaido University, and under specific pathogen–free conditions in the animal facility of Keio University. All animal experiments were approved by the ethics committee of IMSUT, Hokkaido University, and Keio University.

Human subjects

Human biopsy samples of human PPs were collected from healthy small intestinal tissues and analyzed by immunohistochemistry. This was approved by the Committee on Human Subjects at RIKEN and Chiba University.

Preparation of FAE and conventional epithelial monolayers

FAE was isolated from mouse PPs and cecal patches by modifying the method described (Hase et al., 2005; Kimura et al., 2015; Fig. 2 A). Briefly, PPs and cecal patches were soaked in ice-cold HBSS (Life Technologies) containing 30 mM EDTA and 5 mM dithiothreitol. After incubation with gentle shaking for 20 min on ice, FAE monolayers containing both dome and crypt regions were carefully separated from lymphoid follicles by manipulation with a fine needle under stereomicroscopic monitoring.

Mouse small intestinal organoid culture

Small intestinal organoids were derived from Sox8−/− or littermate control mice. The duodenum was removed from mice and cut into 5-mm segments. The segments were incubated in cold 2 mM EDTA in PBS for 5 min and washed by pipetting. The segments were incubated in 2 mM cold EDTA in PBS for 30 min, and crypts were isolated by pipetting with cold HBSS. Dissociated crypts were passed through a 70-µm cell strainer. The crypts were resuspended in DMEM/F12 medium (Stemcell Technologies); then, the number of crypts were counted, and the crypts were resuspended in Matrigel (Corning). Next, the crypts were plated in a 24-well plate with IntestiCult organoid growth medium (Stemcell Technologies). Media were changed every 2 d. For M cell induction, 200 ng/ml recombinant mouse RANKL (Affymetrix) was added to the medium and incubated for 3 d.

Immunofluorescence

For whole-mount staining of the FAE, the isolated epithelium was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 30 min. For organoid staining, organoids were incubated in cold Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (Stemcell Technologies) until dissolution of Matrigel. The organoids were washed with cold PBS twice and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. For conventional immunofluorescence, deeply anesthetized mice were perfused via the aorta with a physiological saline followed with 4% PFA, pH 7.4. The PPs were removed from the ileum and immersed in the same fixative for an additional 24 h. The heads, including nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue, were additionally subjected to decalcification with 5% EDTA for 2 wk at 4°C (Mutoh et al., 2016). The PPs and decalcified heads were dipped in 30% sucrose solution overnight at 4°C, embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek) and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen 10-µm-thick sections were mounted on poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides and air-dried.

After preincubation with 10% normal donkey serum for 1 h, the specimens were incubated with anti-Sox8 antibody, anti-Tnfaip2 antibody (Kimura et al., 2015), anti-GP2 antibody (MBL), anti–Spi-B antibody (R&D Systems), anti-RANK antibody (R&D Systems), or anti-RANKL antibody (BioLegend) in the presence of 0.2% saponin and 0.2% BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with appropriate secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. For nuclear staining, DAPI, TOPRO-3, or Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) was used after incubation with the secondary antibodies. The specimens were observed using a confocal laser microscope FV300 or FV1000 (Olympus) after mounting with SlowFade Gold antifade reagent (Life Technologies).

Image analysis

Confocal images were acquired in the photon-counting mode of an FV1000 confocal microscopy system with FV10-ASW software (Olympus). To calculate the population of GP2-high cells, we selected the region of M cells by setting a threshold of signal intensities for GP2 and/or Spi-B and then calculated mean fluorescence intensities within these regions and the distances from the bottom of crypt using ImageJ software (Fig. 2 A). Obtained values were plotted using Microsoft Excel software.

Pulse-chase experiments

Mice were administered 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU; 5 mg/kg body weight) by intraperitoneal injection. EdU detection was performed using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 imaging kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH was performed using the Quantigene View RNA ISH Cell Assay (Affymetrix) with slight modifications in the fixation and the protease digestion steps. Briefly, isolated epithelium was fixed in a solution containing 4% PFA and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 3 h on ice and then transferred to 4% PFA in PBS, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. After three washing steps with 50 mM glycine in PBS, the specimens were pretreated with a detergent solution (Affymetrix) for 10 min and then protease QS (dilution 1: 400 in PBS; Affymetrix) or 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K in PBS (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc.) for 10 min at room temperature. The following procedures were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Specific oligonucleotide probe sets against Spib (VB4-13734) and Sox8 (VB1-13736) were purchased from Affymetrix.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol (Life Technologies) from epithelium isolated from mice or organoids. First-strand cDNA synthesis was completed using the iScript Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad). The qPCR reactions were conducted in CFX-connect (Bio-Rad) using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The specific primers used are shown in Table S1.

RANKL administration

The primers 5′-CACCCCCGGGCAGCGCTTCTCAGGAGCT-3′ and 5′-GAGACTCGAGTCAGTCTATGTCCTGAAC-3′ (Sigma Genosys, Inc.) were used for PCR to amplify a cDNA clone of RANKL. The PCR fragment was subcloned into the pGEX-4T-2 vector (GE Healthcare) after digestion by SmaI and XhoI. The construct was transformed into the BL21 Escherichia coli strain for GST fusion protein expression. The culture was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 16 h at 20°C, and GST-RANKL was purified from bacterial lysate by affinity chromatography on a Glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) followed by dialysis against multiple changes of PBS. Recombinant GST used as a control was prepared by the same method using an empty pGEX-4T-2 vector. Purified protein was administered to mice by intraperitoneal injections of 250 µg/d for 3 d, according to a previous report with minor modification. After 24 h from the last administration, the mice were sacrificed and subjected to the following assays.

Quantification of uptake of fluorescent beads by M cells

2 × 1011 of 200-nm diameter polystyrene nanoparticles (Fluoresbrite YG; Polysciences) were orally administered to 6-wk-old Sox8−/− or littermate mice that had been fasted for 24 h. 3 h later, two PPs were collected from the jejunum. Then, PPs were embedded in OCT compound and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections of PPs were examined by fluorescence microscopy (BZ-9000; Keyence), and the number of particles was counted manually.

ChIP

For ChIP experiments, C57BL/6 mice were administrated 250 µg GST or GST-mRANKL per day for 3 d. Epithelial monolayers were isolated from duodenum and fixed with 1% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of glycine (final, 125 mM). Cells including chromatin were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (Nacalai Tesque). Chromatin was sheared into 200–800-bp fragments using Micrococcal Nuclease (Takara Bio) and nuclear membranes were broken by sonication. Cell lysate including sheared chromatin was diluted with dilution buffer (16.7 mM Tris-HCl, 0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA, and 167 mM NaCl). Immunoprecipitation was performed using control rabbit IgG (clone DA1E; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-RelB antibody (C1E4; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-Sox8 antibody (ab104245; Abcam) and Dynabeads Protein A (Veritas) at 4°C for overnight. Magnetic beads were washed with low-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, and 150 mM NaCl) five times, high-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, and 500 mM NaCl) three times, and Tris-EDTA buffer (Nacalai Tesque) twice. Immune complexes were eluted in elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) at 65°C for 4 h, and reverse cross-linking were performed in the presence of proteinase K (55°C, 1 h). Precipitated DNA fragments were purified by ChIP DNA Clean Concentrator (Zymo Research). ChIP-qPCR analysis was performed using KOD SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo). PCR primers were designed based on the promoter region including NF-κB consensus sequence or SOX-binding sequence (Table S1).

Cell culture of epithelial cell lines

CMT93 and HEK293T cells were propagated in DMEM containing 10% (vol:vol) FBS, 1% GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin.

Luciferase assay

The coding sequences of mouse Spib and Sox8 were amplified from RANKL-stimulated, organoid–derived cDNA and subcloned into pcDNA3.1 vector (Life Technologies). The Gp2 promoter region (0 to –2,494 nucleotides) was amplified from genomic DNA of C57BL/6 mouse and subcloned into pCRII-Blunt-TOPO vector (Life Technologies), and then into pGL4.11 vector (Promega). PCR primers for cloning are summarized in Table S1. HEK293T and CMT93 cells were cultured in a 24-well plate and transfected with the combination of expression plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies). After 24-h incubation, luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

RNA sequencing

The FAE specimens were collected as described previously (Hase et al., 2005). After the extraction of total RNA using a RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen), cDNA was synthesized using a SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low input RNA kit for sequencing, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara Bio): 50-bp single-end reads were acquired using a HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina) at the Kazusa DNA Research Institute. The genes significantly down-regulated in Sox8−/− mice and Spib−/− mice are listed in Tables S2 and S3, respectively. All data have been deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (accession no. DRA006978).

Fecal IgA ELISA

Feces were collected from Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− mice. Freeze-dried feces were homogenized in PBS with EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete EDTA-free; Roche) and centrifuged at 4°C. Fecal supernatants were diluted in 2% BSA/PBS. MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with goat anti-mouse IgA (Bethyl Laboratories) for 1 h. The plates were washed five times with 0.1% Tween20 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS-T) and then blocked with 2% BSA/PBS at room temperature for 30 min. The plate was incubated with the diluted samples at room temperature for 1 h. After washing five times with TBS-T, the plate was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA antibodies (Bethyl Laboratories) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing five times with TBS-T, the plate was incubated with 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA Substrate Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reaction was stopped by adding 1.2 M sulfuric acid. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Bug-IgA flow cytometry analysis

Bug-IgA flow cytometry analysis were performed as previously reported (Koch et al., 2016). Briefly, large debris in fecal extract from Sox8−/− or littermate control mice was removed by brief centrifugation. The bacteria in the supernatant were stained by biotin- or fluorescence-conjugated antibody as follows: anti-IgA (clone: C10-1) and anti-Igκ light chain (187.1) purchased from BD Biosciences. Live bacteria were identified in the debris by DAPI staining. Flow cytometry was performed using an Aria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Single cell isolation and flow cytometry

PPs from Sox8−/− or littermate control mice were minced and shaken at 37°C with RPMI 1640 containing 2% FBS, 0.1 mg/ml collagenase, 0.1 mg/ml DNase I, and 12.5 mM HEPES. The supernatant was collected and blocked using anti-CD16/CD32 (FcγR) antibody (BioLegend) in 2% FBS/PBS. The cells were stained with antibodies as follows: anti-CD3ε (clone 17A2), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8a (53-6.7), anti-CD45R (30-F11), anti-CD95 (Jo2), anti-CXCR5 (SPRCL5), anti-GL7 (GL-7), anti-IgA (C10-1), and anti-PD-1 (J43) purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, BioLegend, BD Biosciences, or Tonbo Bioscience. Flow cytometry was performed using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Lentiviral infection

Lentiviral supernatants were generated by transient transfection of RelB, RelA, p50- or p52-containing SIN vector (CSII-CMV-RfA-IRES2-Venus, 17 µg), pCAG-HIVgp (10 µg), and pCMV-VSV-G-Rev (10 µg) into Lenti-X 293T (5 × 106/15 ml; Clontech) using Polyethylenimine Max (Polysciences), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All vectors were kindly provided by Dr. H. Miyoshi and RIKEN Bioresource Research Center. Transfected host cells were incubated for 24 h; after culturing for another 48 h, the culture medium was changed to medium containing 10 µM forskolin to allow cells to produce free virions. Viruses were purified after removal of host cells and ultracentrifugation. Dissociated organoids were infected by mixing with 250 µl of virus-including medium, followed by centrifugation at 600 g for 1 h at 32°C. Then, cells were embedded into Matrigel and incubated for 2–3 d.

Colony-forming unit measurement after oral infection

Tetracycline-resistant S. Typhimurium (ΔaroA) was kindly provided by Dr. H. Matsui (Kitasato University, Tokyo, Japan). Sox8−/− or littermate control mice were infected with 5 × 108 CFU of S. Typhimurium (ΔaroA). After 24 h, the three distal PPs (ileal PPs) and MLNs were collected and incubated in PBS containing 500 µg/ml gentamicin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min. Samples were washed with PBS containing 1 mM dithiothreitol, homogenized in sterile PBS, and subsequently centrifuged briefly to roughly remove host cells. Tenfold serial dilutions of the resulting supernatants were plated on Luria-Bertani agar plates containing 15 µg/ml tetracycline (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd.) to determine the number of CFUs.

Immunization and tetanus toxoid (TT)–specific ELISA

Recombinant Salmonella (rSalmonella)–ToxC (ΔaroA, ΔaroD) and TT were kindly provided by the BIKEN Foundation (Osaka, Japan). Sox8−/− or littermate control mice were orally immunized with 5 × 107 CFU of rSalmonella-ToxC. TT-specific IgA and IgG in feces and serum were measured by ELISA. Flat-bottomed, 96-well MaxiSorp Nunc-Immuno plates were coated overnight with 500 ng/well of TT. Plates were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS, and optically diluted fecal extracts and sera were added into the plate wells. The Mouse IgA ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl Laboratories) and Mouse IgG ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl Laboratories) were used for antibody detection. To produce HRP signals, a 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA was used.

In vitro B cell differentiation

Pan B cells were isolated from spleens of Sox8−/− or littermate control mice using MojoSort mouse pan B cell isolation kit (BioLegend) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. For IgA+ B cell polarization, pan B cells were stimulated with 2 µg/ml F(ab′)2-goat-anti-mIgM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 µg/ml anti-mCD40 (3/23; BioLegend) in complete advanced RPMI 1640 media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 5% vol:vol FCS (MP Biomedicals) supplemented with 1 ng/ml recombinant human (rh) TGF-β1, 5 ng/ml recombinant mouse (rm) IL-5, 20 ng/ml rmIL-21 (all from BioLegend), and 10 nM all-trans retinoic acid (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical) for 6 d. For IgG1+ and IgE+ B cell polarization, pan B cells were stimulated with anti-mIgM and anti-mCD40 in complete media supplemented with 20 ng/ml rmIL-21 and 50 ng/ml rmIL-4 (BioLegend) for 6 d. For IgG2a+ B cell polarization, pan B cells were stimulated with anti-mIgM and anti-mCD40 in complete media supplemented with 20 ng/ml rmIL-21 and 50 ng/ml rmIFN-γ (BioLegend) for 6 d.

In vitro T cell differentiation

Naive T cells were isolated from spleen of Sox8−/− or littermate control mice using a MojoSort mouse naive T-cell isolation kit (BioLegend) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. For induced T reg polarization, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with immobilized anti-TCRβ mAb (H57-597, 5 µg/ml; BioXCell) on a high-binding 96-well plate (Corning) and soluble anti-CD28 mAb (37.51, 2 µg/ml; BioXCell) in complete advanced RPMI 1640 media containing 5% vol:vol FCS supplemented with 0.5 ng/ml rhTGF-β1 and 10 ng/ml rmIL-2 (BioLegend) for 2 d. The stimulated T cells were expanded in complete media supplemented with rhTGF-β1 and rmIL-2 for another 3 d. For Th1 cell polarization, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with immobilized anti-TCRβ mAb and soluble anti-CD28 mAb and anti-mIL-4 (11b11; BioXCell) in complete media supplemented with 10 ng/ml rmIL-2 and 10 ng/ml rmIL-12 (BioLegend) for 2 d. The stimulated T cells were expanded in complete media supplemented with anti-mIL-4 and rmIL-2 and rmIL-12 for another 3 d. For Th2 cell polarization, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with immobilized anti-TCRβ mAb and soluble anti-CD28 mAb and anti-mIFN-γ (R4-6A2; BioXCell) in complete media supplemented with 10 ng/ml rmIL-2 and 10 ng/ml rmIL-4 for 2 d. The stimulated T cells were expanded in complete media supplemented with anti-mIFN-γ, rmIL-2 and rmIL-4 for another 3 d. For Th17 cell polarization, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with immobilized anti-TCRβ mAb and soluble anti-CD28 mAb and anti-mIL4 and anti-mIFNγ in complete media supplemented with 25 ng/ml rmIL-6 (BioLegend), 0.1 ng/ml rhTGF-β1, and 300 nM 6-formylindolo(3,2-b)carbazole (FICZ; Abcam) for 2 d. The stimulated T cells were expanded in complete media supplemented with anti-mIL4, anti-mIFN-γ, rmIL-6, rhTGF-β1, and FICZ for another 3 d.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows Sox8 expression in the FAE of cecal patches and nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissues in the mice. Fig. S2 shows whole-mount image analysis of Spi-B expression level and the relationship of distance and cell age. Fig. S3 shows the transcriptome analysis for comparison of gene expression profiling of FAEs between Sox8+/+ and Sox8−/− or Spib+/+ and Spib−/− mice. Fig. S4 shows that RANKL-RelB signaling is unaffected by Sox8 deficiency. Fig. S5 shows immune cell composition in MALTs in Sox8+/+ mice. Table S1 is the list of primers used in this experiment. Tables S2 and S3 are gene lists down-regulated in Sox8−/− and Spib−/− mice, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Osamu Ohara (Kazusa DNA Research Institute) for providing support with RNA sequencing analysis; Motoyoshi Nagai, Hiyori Tanabe, Shunsuke Takano, and Yumiko Fujimura (Keio University) for providing technical assistance with animal experiments; Dr. Hidenori Matsui for providing S. Typhimurium; Dr. Hiroyuki Miyoshi (Keio University, Tokyo, Japan) for providing lentiviral vector; Dr. Atsushi Miyawaki (RIKEN, Wako, Japan) for providing Venus cDNA; and Dr. Michael Wegner (Friedrich-Alexander-University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany) for providing anti-Sox8 serum used in preliminary experiments.

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants JP16J09413 (N. Kobayashi), JP16H06598 (M. Mutoh), JP25460261 and JP16K08457 (S. Kimura), and JP25293114 and JP17H04089 (K. Hase).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Conceptualization, S. Kimura and K. Hase; Methodology, S. Kimura, N. Kobayashi, Y. Nakamura, T. Kanaya, M. Mutoh, Y. Obata, and R. Fujiki; Investigation, S. Kimura, N. Kobayashi, Y. Nakamura, T. Kanaya, R. Fujiki, M. Mutoh, D. Takahashi, T. Iwanaga, and K. Hase; Resources, T. Kanaya, N. Kato, T. Nakagawa, S. Sato, and T. Kaisho; Writing (original draft), S. Kimura and N. Kobayashi; Writing (review and editing), S. Kimura, T. Iwanaga, and K. Hase; Supervision, S. Kimura, H. Ohno, and K. Hase; and Funding Acquisition, S. Kimura, N. Kobayashi, M. Mutoh, and K. Hase.

References

- Bastide P., Darido C., Pannequin J., Kist R., Robine S., Marty-Double C., Bibeau F., Scherer G., Joubert D., Hollande F., et al. 2007. Sox9 regulates cell proliferation and is required for Paneth cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 178:635–648. 10.1083/jcb.200704152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benckert J., Schmolka N., Kreschel C., Zoller M.J., Sturm A., Wiedenmann B., and Wardemann H.. 2011. The majority of intestinal IgA+ and IgG+ plasmablasts in the human gut are antigen-specific. J. Clin. Invest. 121:1946–1955. 10.1172/JCI44447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blache P., van de Wetering M., Duluc I., Domon C., Berta P., Freund J.N., Clevers H., and Jay P.. 2004. SOX9 is an intestine crypt transcription factor, is regulated by the Wnt pathway, and represses the CDX2 and MUC2 genes. J. Cell Biol. 166:37–47. 10.1083/jcb.200311021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockman D.E., and Cooper M.D.. 1973. Pinocytosis by epithelium associated with lymphoid follicles in the bursa of Fabricius, appendix, and Peyer’s patches. An electron microscopic study. Am. J. Anat. 136:455–477. 10.1002/aja.1001360406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau W., Kujala P., Schneeberger K., Middendorp S., Li V.S., Barker N., Martens A., Hofhuis F., DeKoter R.P., Peters P.J., et al. 2012. Peyer’s patch M cells derived from Lgr5(+) stem cells require SpiB and are induced by RankL in cultured “miniguts”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:3639–3647. 10.1128/MCB.00434-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather N.F., Chatfield S.N., Makoff A.J., Strugnell R.A., Bester J., Maskell D.J., and Dougan G.. 1990. Oral vaccination of mice against tetanus by use of a live attenuated Salmonella carrier. Infect. Immun. 58:1323–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fevr T., Robine S., Louvard D., and Huelsken J.. 2007. Wnt/β-catenin is essential for intestinal homeostasis and maintenance of intestinal stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:7551–7559. 10.1128/MCB.01034-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase K., Ohshima S., Kawano K., Hashimoto N., Matsumoto K., Saito H., and Ohno H.. 2005. Distinct gene expression profiles characterize cellular phenotypes of follicle-associated epithelium and M cells. DNA Res. 12:127–137. 10.1093/dnares/12.2.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase K., Kawano K., Nochi T., Pontes G.S., Fukuda S., Ebisawa M., Kadokura K., Tobe T., Fujimura Y., Kawano S., et al. 2009a Uptake through glycoprotein 2 of FimH(+) bacteria by M cells initiates mucosal immune response. Nature. 462:226–230. 10.1038/nature08529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase K., Kimura S., Takatsu H., Ohmae M., Kawano S., Kitamura H., Ito M., Watarai H., Hazelett C.C., Yeaman C., and Ohno H.. 2009b M-Sec promotes membrane nanotube formation by interacting with Ral and the exocyst complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:1427–1432. 10.1038/ncb1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijikata A., Kitamura H., Kimura Y., Yokoyama R., Aiba Y., Bao Y., Fujita S., Hase K., Hori S., Ishii Y., et al. 2007. Construction of an open-access database that integrates cross-reference information from the transcriptome and proteome of immune cells. Bioinformatics. 23:2934–2941. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Hou C.C., She Z.Y., and Yang W.X.. 2013. The SOX gene family: function and regulation in testis determination and male fertility maintenance. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40:2187–2194. 10.1007/s11033-012-2279-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamachi Y., Cheah K.S., and Kondoh H.. 1999. Mechanism of regulatory target selection by the SOX high-mobility-group domain proteins as revealed by comparison of SOX1/2/3 and SOX9. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:107–120. 10.1128/MCB.19.1.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya T., Hase K., Takahashi D., Fukuda S., Hoshino K., Sasaki I., Hemmi H., Knoop K.A., Kumar N., Sato M., et al. 2012. The Ets transcription factor Spi-B is essential for the differentiation of intestinal microfold cells. Nat. Immunol. 13:729–736. 10.1038/ni.2352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya T., Sakakibara S., Jinnohara T., Hachisuka M., Tachibana N., Hidano S., Kobayashi T., Kimura S., Iwanaga T., Nakagawa T., et al. 2018. Development of intestinal M cells and follicle-associated epithelium is regulated by TRAF6-mediated NF-κB signaling. J. Exp. Med. 215:501–519. 10.1084/jem.20160659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataruka S., Akhade V.S., Kayyar B., and Rao M.R.S.. 2017. Mrhl Long noncoding RNA mediates meiotic commitment of mouse spermatogonial cells by regulating Sox8 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 37:e00632-e16 10.1128/MCB.00632-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto S., Tran T.H., Maruya M., Suzuki K., Doi Y., Tsutsui Y., Kato L.M., and Fagarasan S.. 2012. The inhibitory receptor PD-1 regulates IgA selection and bacterial composition in the gut. Science. 336:485–489. 10.1126/science.1217718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S., Yamakami-Kimura M., Obata Y., Hase K., Kitamura H., Ohno H., and Iwanaga T.. 2015. Visualization of the entire differentiation process of murine M cells: suppression of their maturation in cecal patches. Mucosal Immunol. 8:650–660. 10.1038/mi.2014.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishikawa S., Sato S., Kaneto S., Uchino S., Kohsaka S., Nakamura S., and Kiyono H.. 2017. Allograft inflammatory factor 1 is a regulator of transcytosis in M cells. Nat. Commun. 8:14509 10.1038/ncomms14509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoop K.A., Kumar N., Butler B.R., Sakthivel S.K., Taylor R.T., Nochi T., Akiba H., Yagita H., Kiyono H., and Williams I.R.. 2009. RANKL is necessary and sufficient to initiate development of antigen-sampling M cells in the intestinal epithelium. J. Immunol. 183:5738–5747. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M.A., Reiner G.L., Lugo K.A., Kreuk L.S., Stanbery A.G., Ansaldo E., Seher T.D., Ludington W.B., and Barton G.M.. 2016. Maternal IgG and IgA antibodies dampen mucosal T helper cell responses in early life. Cell. 165:827–841. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer D.R., and Cebra J.J.. 1995. Early appearance of “natural” mucosal IgA responses and germinal centers in suckling mice developing in the absence of maternal antibodies. J. Immunol. 154:2051–2062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelouard H., Henri S., De Bovis B., Mugnier B., Chollat-Namy A., Malissen B., Méresse S., and Gorvel J.P.. 2010. Pathogenic bacteria and dead cells are internalized by a unique subset of Peyer’s patch dendritic cells that express lysozyme. Gastroenterology. 138:173–184.e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelouard H., Fallet M., de Bovis B., Méresse S., and Gorvel J.P.. 2012. Peyer’s patch dendritic cells sample antigens by extending dendrites through M cell-specific transcellular pores. Gastroenterology. 142:592–601.e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabbott N.A., Donaldson D.S., Ohno H., Williams I.R., and Mahajan A.. 2013. Microfold (M) cells: important immunosurveillance posts in the intestinal epithelium. Mucosal Immunol. 6:666–677. 10.1038/mi.2013.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantis N.J., Rol N., and Corthésy B.. 2011. Secretory IgA’s complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 4:603–611. 10.1038/mi.2011.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura T., Sugawara Y., Yutani M., Amatsu S., Yagita H., Kohda T., Fukuoka S., Nakamura Y., Fukuda S., Hase K., et al. 2015. Botulinum toxin A complex exploits intestinal M cells to enter the host and exert neurotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 6:6255 10.1038/ncomms7255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori-Akiyama Y., van den Born M., van Es J.H., Hamilton S.R., Adams H.P., Zhang J., Clevers H., and de Crombrugghe B.. 2007. SOX9 is required for the differentiation of paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 133:539–546. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu M., Kinoshita K., Fagarasan S., Yamada S., Shinkai Y., and Honjo T.. 2000. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 102:553–563. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00078-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh M., Kimura S., Takahashi-Iwanaga H., Hisamoto M., Iwanaga T., and Iida J.. 2016. RANKL regulates differentiation of microfold cells in mouse nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT). Cell Tissue Res. 364:175–184. 10.1007/s00441-015-2309-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima K., Sawa S., Nitta T., Tsutsumi M., Okamura T., Penninger J.M., Nakashima T., and Takayanagi H.. 2017. Identification of subepithelial mesenchymal cells that induce IgA and diversify gut microbiota. Nat. Immunol. 18:675–682. 10.1038/ni.3732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutra M.R., Phillips T.L., Mayer E.L., and Fishkind D.J.. 1987. Transport of membrane-bound macromolecules by M cells in follicle-associated epithelium of rabbit Peyer’s patch. Cell Tissue Res. 247:537–546. 10.1007/BF00215747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryan M.K., Takada S., Kennedy C.L., Scott G., Harada S., Ray M.K., Dai Q., Wilhelm D., de Kretser D.M., Eddy E.M., et al. 2008. Sox8 is a critical regulator of adult Sertoli cell function and male fertility. Dev. Biol. 316:359–370. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen R.L. 1977. Sequential uptake of horseradish peroxidase by lymphoid follicle epithelium of Peyer’s patches in the normal unobstructed mouse intestine: an ultrastructural study. Gastroenterology. 72:440–451. 10.1016/S0016-5085(77)80254-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen R.L. 1999. Uptake and transport of intestinal macromolecules and microorganisms by M cells in Peyer’s patches—a personal and historical perspective. Semin. Immunol. 11:157–163. 10.1006/smim.1999.0171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D., Gregorieff A., Begthel H., and Clevers H.. 2003. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev. 17:1709–1713. 10.1101/gad.267103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios D., Wood M.B., Li J., Chassaing B., Gewirtz A.T., and Williams I.R.. 2016. Antigen sampling by intestinal M cells is the principal pathway initiating mucosal IgA production to commensal enteric bacteria. Mucosal Immunol. 9:907–916. 10.1038/mi.2015.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki I., Hoshino K., Sugiyama T., Yamazaki C., Yano T., Iizuka A., Hemmi H., Tanaka T., Saito M., Sugiyama M., et al. 2012. Spi-B is critical for plasmacytoid dendritic cell function and development. Blood. 120:4733–4743. 10.1182/blood-2012-06-436527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S., Kaneto S., Shibata N., Takahashi Y., Okura H., Yuki Y., Kunisawa J., and Kiyono H.. 2013. Transcription factor Spi-B-dependent and -independent pathways for the development of Peyer’s patch M cells. Mucosal Immunol. 6:838–846. 10.1038/mi.2012.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih V.F., Tsui R., Caldwell A., and Hoffmann A.. 2011. A single NFκB system for both canonical and non-canonical signaling. Cell Res. 21:86–102. 10.1038/cr.2010.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierro F., Pringault E., Assman P.S., Kraehenbuhl J.P., and Debard N.. 2000. Transient expression of M-cell phenotype by enterocyte-like cells of the follicle-associated epithelium of mouse Peyer’s patches. Gastroenterology. 119:734–743. 10.1053/gast.2000.16481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sminia T., Janse E.M., and Plesch B.E.. 1983. Ontogeny of Peyer’s patches of the rat. Anat. Rec. 207:309–316. 10.1002/ar.1092070209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolt C.C., Schmitt S., Lommes P., Sock E., and Wegner M.. 2005. Impact of transcription factor Sox8 on oligodendrocyte specification in the mouse embryonic spinal cord. Dev. Biol. 281:309–317. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji M., Komatsu N., Kawamoto S., Suzuki K., Kanagawa O., Honjo T., Hori S., and Fagarasan S.. 2009. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer’s patches. Science. 323:1488–1492. 10.1126/science.1169152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanCott J.L., Staats H.F., Pascual D.W., Roberts M., Chatfield S.N., Yamamoto M., Coste M., Carter P.B., Kiyono H., and McGhee J.R.. 1996. Regulation of mucosal and systemic antibody responses by T helper cell subsets, macrophages, and derived cytokines following oral immunization with live recombinant Salmonella. J. Immunol. 156:1504–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M.C., and Choi Y.. 2014. Biology of the RANKL-RANK-OPG system in immunity, bone, and beyond. Front. Immunol. 5:511 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weider M., and Wegner M.. 2017. SoxE factors: Transcriptional regulators of neural differentiation and nervous system development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 63:35–42. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M.B., Rios D., and Williams I.R.. 2016. TNF-α augments RANKL-dependent intestinal M cell differentiation in enteroid cultures. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 311:C498–C507. 10.1152/ajpcell.00108.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]