Abstract

Aims:

To test how a housing voucher generating residential mobility to lower-poverty neighborhoods, compared to public housing controls, influenced adolescent binge drinking, and whether gender modified effects.

Design:

A multi-site household-level 3-arm randomized trial of a housing intervention executed 1994–1998, evaluated 2001–2002.

Setting:

Five US cities: Baltimore, MD, Boston, MA, Chicago, IL, Los Angeles, CA, New York, NY

Interventions:

The Moving to Opportunity trial randomized volunteer low-income families in public housing to receive 1) rental subsidies redeemable in neighborhoods with <10% tract poverty plus housing counseling, 2) unrestricted Section 8 rental subsidies, or 3) to remain in public housing. We pooled the subsidy (“treatment”) groups because they were conceptually similar and there was no evidence of statistical differences between groups on binge drinking.

Participants:

3537 adolescents in 4248 low-income eligible families were randomized; 2829 adolescents were analyzed at the interim evaluation (1950 in treatment; 879 in control group). Attrition bias was accounted for with a 3-in-10 oversampling of hard-to-reach participants (effective response rate: 89%).

Measures:

Primary outcome: past month binge drinking (5 or more drinks in one sitting).

Findings:

Adolescent binge drinking prevalence was 3.9% for treatment, 3.2% for control. The Intention to Treat (ITT) main effect of subsidy treatment (vs. control) on binge drinking was nonsignificant, but treatment effects were different for girls and boys (treatment-gender interaction p=.002). MTO treatment reduced girls’ binge drinking (Odds Ratio (OR)= 0.48, 95% CI: 0.24–0.96, p=.037), but increased boys’ binge drinking (OR=2.37, 95%CI: 1.13–4.97, p=.023), compared to controls. Results were similar for secondary alcohol outcomes. Instrumental variable (IV) results adjusting for treatment compliance were comparable to ITT, but larger.

Conclusions:

This housing subsidy treatment exerted opposite effects on binge drinking by gender, suggesting adolescent boys using housing subsidies require additional supports, and neighborhood influences on drinking may operate through gender specific, potentially social, pathways.

Keywords: binge drinking, housing, adolescent, social experiment, randomized

Excessive alcohol drinking is a major public health problem leading to alcohol disorder and other negative outcomes, including impaired driving and motor vehicle accidents, violence, sexual assault, suicide, and physical illness.(1) Since most alcohol disorders in adulthood originate in adolescence,(1) it is imperative to focus on childhood and family origins.(2) Indeed, a substantial literature suggests that family and peer factors are associated with uptake of alcohol use and excessive drinking during adolescence,(2) and finds the progression of alcohol use during adolescence is dynamic.(3)

Beyond these proximal risks, contextual factors also confer substantial risk for excessive drinking.(4) Specifically, neighborhood context may be an upstream cause of alcohol use,(4) operating, for example, through pathways including alcohol availability, socioeconomic status (SES), social relationships, or drinking norms.(5–7) Empirically, prior neighborhood-adolescent alcohol use evidence is mixed, with many null findings, particularly when neighborhood exposure constructs are operationalized at the neighborhood (not individual) level.(5, 7, 8) Although neighborhood SES is related to alcohol use consistently among adults, this association is less consistent for adolescents.(9) Higher outlet density and exposure to neighborhood advertising are most commonly associated with alcohol use, particularly for adolescents, although findings are still mixed.(5)

Unfortunately, this literature is based on cross-sectional observational designs, on adults, and on concurrent neighborhood exposures,(5, 7–9) with limited evidence on how interventions or dynamic places shape substance use early in life and across time; this presents serious threats to causal inference, and barriers to policy translation.(10) For example, residential selection – the motivations and constraints shaping household moves – is seldom modeled, but is the fundamental threat for causal inference.(11) Prior neighborhood-alcohol studies have also rarely tested moderation, including by gender.(5, 7, 8)

Affordable housing policies have the potential to mitigate neighborhood inequality for low-income households. For example, housing allowance policies defray housing costs for low-income households, and are used in most developed nations.(12) Although its primary goal is to improve housing affordability, if the subsidy is used to offset housing costs in the private rental market, as in the US, it may also promote residential mobility into high-opportunity neighborhoods. For example, the US-based Moving to Opportunity (MTO) study manipulated neighborhood and housing context by randomizing low income families living in high-poverty public housing to receive a Section 8 housing voucher to subsidize private market rent, compared to public housing controls.(13) MTO treatment (vs. control) group families moved to better neighborhoods characterized by lower neighborhood poverty, better neighborhood social systems (e.g., improved collective efficacy, safety; reduced neighborhood disorder and crime), and improved natural features (e.g., tree cover).(13) MTO was implemented in the housing sector to improve economic self-sufficiency. Despite this, health emerged as an outcome that was unexpected prior to study launch, until early impact research revealed the importance of health to participants’ lives.(14) MTO remains underutilized by health researchers despite its utility to inform how changes in housing exposures may influence health, including alcohol use.

In this study, we undertook a secondary data analysis of this randomized controlled trial (RCT) and tested how changes in housing/neighborhood context achieved via housing mobility policy affected the drinking behavior of adolescents. We aimed to 1) test the treatment main effect of the trial (vs. control), and 2) test whether gender modified the treatment effects on adolescent binge drinking, given that prior research using MTO has documented treatment effects on adolescent mental health outcomes varying by gender.(14–17) Theoretically, since gender is a master status, it may influence all social interactions that cascade from neighborhood context. Moreover, multiple pathways may link gender to alcohol use and these may vary by social and environmental context. Lastly, since experimental designs like MTO address serious threats to causal inference, including residential selection,(17) MTO can address causal questions regarding how reducing exposure to impoverished neighborhoods affects binge drinking, including among subgroups.

METHODS

Design.

MTO used a 3-arm RCT design, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 5 U.S. cities (“sites”): Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York. Low-income families comprised the unit of random assignment. Among 5301 volunteer families, 4610 were eligible and 4248 were randomized to one of three intervention arms.(14) Random assignment numbers were not intended to be equal across each treatment arm, but were initially determined for the Low poverty and Section 8 treatment arms to yield sufficient numbers of households who used the voucher. Random assignment ratios were adjusted over time and differed by site. Sample size calculations were based on detecting impacts of the primary outcomes of employment, income, and education,(18) with no pre-random-assignment sample size calculations related to binge drinking.

Participants.

Low-income families with children under age 18, who qualified for rental assistance, and lived in public housing or project-based assisted housing in high poverty neighborhoods at baseline, were eligible. Household heads and up to two randomly-selected children completed surveys at baseline (1994–1998), at interim (ranging 4–7 years after randomization 2001–2002), and at the final evaluation (10–15 years after randomization 2008–2010). We analyzed 2829 adolescents 12–19 years old at interim who were randomized through 12/31/97 in the MTO Tier 1 Restricted Access Data (RAD), which contains a fine geography level while maintaining de-identification.(14) There were 356 families randomized in 1998, but they were excluded from the RAD given their short follow-up time.(19) The data used in this manuscript were obtained under license from HUD, and are not publicly available, but interested parties may contact HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research to request it.

Procedures.

Random assignment was implemented by Abt Associates using specialized software (20). Study personnel obtained consent from adults for themselves and their children <18, assent from children <18, and consent directly from youth 18+.(14, 20, 21) Interviews were conducted in person via computer-assisted interviewing technology.

Interventions.

Families were randomized to one of three treatment groups: 1) the “low-poverty” group received a Section 8 housing voucher that subsidized renting a private apartment in low poverty neighborhoods, where <10% of households in the census tract were impoverished, as well as housing counseling to assist them with relocation; 2) the “Section 8” treatment group received a traditional Section 8 housing subsidy voucher with no locational constraints or housing counseling; and 3) the control group was given no further assistance or voucher, but could remain in public housing.(20) The rules required a voucher household to lease an apartment within 90 days, and to pay 30% of its income towards renting a suitable apartment; the government subsidized the remainder of the rent up to a local ceiling.(14) Families who abided by program rules could retain their voucher if they moved to another apartment after the first move, although the low-poverty treatment group was required to remain in its first unit for one year; after this point low-poverty treatment families could move to another apartment using their voucher, regardless of neighborhood poverty level.

Treatment Compliance is measured as voucher group members who used the MTO voucher to move within 90 days of receipt. Controls could not obtain an MTO voucher, so all controls were compliant by definition. Randomization to receive a voucher was also used as an instrumental variable (IV).

Measures. Outcomes.

Adolescent alcohol use was self-reported in 2002 (Interim). Our primary outcome was past month binge drinking (“On how many days did you have 5 or more drinks on the same occasion during the past 30 days?”), recoded where 1=any days binge drinking, and 0=no binge drinking among drinkers, or no alcohol use for those who reported not drinking ever or during the past month). Secondary outcomes included binary variables (coded 1=yes, 0=no) for lifetime alcohol use, past month alcohol use, and past month consumption of alcohol before or during work or school. Additional secondary outcomes included count variables representing the number of days in the past month alcohol was consumed, the average number of drinks drank on the days that youth drank alcohol, and the total number of drinks consumed in the past month. These are valid and reliable measures(22) commonly used in other national surveys.(23, 24) Alcohol use outcomes were missing for fewer than 1.8% of observations, which we dropped to conduct a complete case analysis.

Baseline Covariates.

Regression-adjusted covariates included youth’s gender, age, race/ethnicity (black vs. non-black/other/missing), expulsion history, received help for behavioral/emotional problems, health problems requiring special medicine or equipment; household head enrolled in school, would tell neighbor if their child was getting into trouble. Youth expulsion history and behavioral/emotional problems were missing 5% or more data, so missing data was coded to the mode of 0 and modeled with missing indicators. All other baseline covariates were missing <5% and imputed to site-specific means.

Statistical Methods.

We first presented crude analyses of treatment (vs. control) on binge drinking. We then tested whether random assignment to treatment arm was associated with binge drinking, using crude and covariate-adjusted intention-to-treat (ITT) logistic regression models. ITT indicates that we included all observations in their originally-randomized treatment, regardless of compliance. We controlled for covariates that were either unbalanced by chance at baseline (ensuring internal validity), or were associated with the alcohol outcome (improving precision), in our main analyses.(25) Sensitivity analyses controlled for all covariates to inform robustness.

Given that the two voucher groups were similar substantively (because both were voucher-based rental subsidies that generated residential mobility), combined with statistical evidence of no heterogeneity (binge drinking p heterogeneity=.83), we combined these voucher groups for parsimony, similar to prior studies.(15) Results retaining the original 3 treatment arms are presented in supplemental tables. We tested treatment-gender interactions and estimated gender-specific ITT effects using post-estimation commands in Stata 14.0.

ITT analyses estimated effects of randomly-assigned treatment, but in MTO only 50% of voucher holders moved with their voucher. Therefore, we applied instrumental variable (IV) analysis to estimate the effect of actually using the voucher on alcohol use. As-treated analyses, comparing those who did and did not use the MTO voucher regardless of who was randomized to receive it, re-introduce biases that RCTs are designed to eliminate,(17, 26) particularly given that compliers differed systematically from noncompliers.(27) IV is a well-documented method to estimate unbiased effects of receiving treatment in a trial, even if compliance was selective. (17, 26) Typical IV analysis leverages 2-stage least squares (2SLS) to estimate the Treatment-on-Treated (TOT) effect. Here, we estimated 2-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) IV, to accommodate nonlinear second stage alcohol outcomes.(28, 29) In 2SRI, the 1st stage predicts use of the voucher from MTO treatment assignment, and returns the residuals, which represent variation in MTO voucher use that is not attributable to randomization, i.e., all variation attributable to other factors (potential confounders of voucher compliance – alcohol use association). These residuals are included as an independent variable in the 2nd stage to predict alcohol use, along with voucher use. Under IV assumptions, the 2nd stage coefficient is a consistent estimate of the causal effect of voucher use on nonlinear outcomes.(29) We bootstrapped both stages with 500 replications to obtain standard errors.(30)

We applied survey weights to all analyses, which adjusted for changing treatment random assignment ratios over time and by site, as well as for attrition (weights that account for the 3-in10 oversample among hard-to-reach families), and selection of up to 2 youth per household; all analyses estimated robust standard errors to account for clustering within families.(14, 17) We considered multiple imputation (MI), but used complete case analysis given how time-intensive MI was within IV model estimation and bootstrapping, and since it was unlikely to influence results given the small amount of missing data.

To assess magnitude of treatment effects, in final ITT models, we graphed predicted probabilities of binge drinking, and estimated risk differences. We then used estimates from voucher compliers and the control group to calculate number needed to treat/harm (NNT/NNH) (31) and population attributable fraction (PAF) (32) by gender.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents baseline descriptive statistics by gender and treatment group. Only two child-level variables were imbalanced: receiving help for behavioral/emotional problems, and special medicine/equipment (Supplemental Table 1 presents baseline statistics by 3 originally-randomized arms). The raw retention rate of adolescents at interim was 80% in both voucher and control groups; however, with oversampling to prevent attrition bias, the effective response rate was 89%.

Table 1.

Moving to Opportunity Youth, Baseline Variables, Overall and by Treatment Group.

| Treatment Group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Variable | Overall | Voucher Treatment (Combined) | Controls | |

| Total in Interim Survey in 2002 | N | 2829 | 1950 | 879 | |

| Baseline mean poverty rate | Percent poverty rate in the 1990 census tract | 49.80% | 49.50% | 50.50% | |

| Family Characteristics | |||||

| Victimization | Household member victimized by crime during past 6 months | 43.00% | 43.80% | 41.30% | |

| Health | Household member had disability, health or developmental problem | 43.00% | 43.60% | 41.50% | |

| Household member had a disability | 17.20% | 17.80% | 15.80% | ||

| Site | Baltimore | 15.50% | 16.00% | 14.20% | |

| Boston | 18.90% | 18.10% | 20.70% | ||

| Chicago | 22.40% | 23.30% | 20.40% | ||

| Los Angeles | 18.60% | 17.50% | 21.20% | ||

| New York | 24.60% | 25.10% | 23.50% | ||

| Household size | 2 people | 7.30% | 6.90% | 8.30% | |

| 3 people | 22.30% | 22.10% | 22.90% | ||

| 4 people | 25.40% | 26.20% | 23.40% | ||

| 5 or more people | 45.00% | 44.80% | 45.40% | ||

| Youth Characteristics | |||||

| Age (in years) | 9.94 | 9.96 | 9.88 | ||

| Gender | Male | 49.90% | 49.50% | 51.00% | |

| Female | 50.10% | 50.50% | 49.00% | ||

| Race/ethnicity | African American | 62.80% | 63.20% | 62.10% | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, any race | 30.00% | 30.30% | 29.50% | ||

| White | 1.10% | 1.00% | 1.20% | ||

| Other race | 2.20% | 2.40% | 1.90% | ||

| Missing race | 3.80% | 3.20% | 5.30% | ||

| Gifted | Special class for gifted students or did advanced work | 15.40% | 14.70% | 16.80% | |

| Developmental Problems | Special school, class, or help for learning problem in past 2 years | 16.60% | 16.70% | 16.30% | |

| Special school, class, or help for behavioral or emotional problems in past 2 years | 7.70% | 8.70% | 5.30% | ||

| Problems that made it difficult to get to school and/or to play active games | 6.50% | 7.10% | 5.00% | ||

| Problems that required special medicine and/or equipment | 9.10% | 10.00% | 7.00% | ||

| School asked to talk about problems child having with schoolwork or behavior in past 2 years | 26.30% | 26.70% | 25.40% | ||

| Child or young adult ten age 6–17 was suspended or expelled from school | 9.93% | 10.92% | 7.74% | ||

| Household Head Characteristics | |||||

| Family Structure | Never married | 55.90% | 55.20% | 57.50% | |

| No teen (ages 13–17) children in household | 47.30% | 46.05% | 50.14% | ||

| Teen parent | 25.90% | 26.40% | 25.00% | ||

| Socioeconomic Status | Employed | 25.80% | 26.10% | 25.30% | |

| On AFDC (welfare) | 76.00% | 75.50% | 76.90% | ||

| adult respondent had a car | 19.09% | 19.16% | 18.93% | ||

| Education | Less than high school | 47.10% | 47.20% | 46.70% | |

| High school diploma | 36.20% | 36.60% | 35.30% | ||

| GED | 16.70% | 16.10% | 17.90% | ||

| In School | 13.90% | 14.40% | 12.60% | ||

| Neighborhood/Mobility Variables | Lived in neighborhood 5 or more years | 65.70% | 65.80% | 65.50% | |

| No family living in neigh | 64.10% | 63.10% | 66.30% | ||

| No friends living in neigh | 37.30% | 36.80% | 38.50% | ||

| Had applied for section 8 voucher before | 44.30% | 43.60% | 45.80% | ||

| Respondent had moved more than 3 times in 5 years prior to baseline | 8.01% | 7.42% | 9.37% | ||

| Respondent was very dissatisfied with his/her neighborhood | 45.13% | 45.91% | 43.34% | ||

| Streets near home were very unsafe at night | 49.10% | 49.02% | 49.27% | ||

| Respondent reported being very sure he/she would find an apartment in a different area of the city | 45.38% | 45.35% | 45.42% | ||

| Respondent’s reason for wanting to move was to get away from gangs or drugs | 76.88% | 76.22% | 78.36% | ||

| Respondent’s reason for moving was to have access to better schools for children | 53.23% | 53.64% | 52.27% | ||

| Neighbor Relationships | Chats with neighbors at least once a week | 51.90% | 51.30% | 53.20% | |

| Respondent very likely to tell neighbor if saw neighbor’s child getting into trouble | 56.70% | 56.80% | 56.40% | ||

NOTES: All variables range between 0 & 1 except baseline age (5–16) and mean poverty rate, so means represent proportions. Analysis weighted for varying treatment random assignment ratios across time, for attrition, and for differential selection probabilities of children within families.

At the interim evaluation when youth were on average 15.2 years old, neither prevalence of youth past-month binge drinking, nor any secondary drinking measure, was patterned by treatment group alone (Table 2; Supplemental Table 2). However, binge drinking and secondary drinking outcomes showed strong differences by gender and treatment group (Supplemental Table 3), with generally higher prevalence (or means) for treatment group boys.

Table 2.

Youth Alcohol Statistics, Moving to Opportunity Data, Interim Follow Up (2001–02), Overall and by Treatment Group (n=2829)

| Total | Voucher Treatment (Combined) | Control Group | Missing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | % |

| Past 30 Day Binge Drinking † | 0.037 | 0.229 | 0.039 | 0.236 | 0.032 | 0.212 | 1.38% |

| Lifetime Alcohol Use † | 0.301 | 0.557 | 0.301 | 0.559 | 0.301 | 0.552 | 0.67% |

| Past 30 Day Alcohol Use † | 0.128 | 0.406 | 0.130 | 0.411 | 0.124 | 0.396 | 0.95% |

| Past 30 Day Number of Days Drank Alcohol | 0.423 | 2.256 | 0.440 | 2.317 | 0.386 | 2.114 | 0.95% |

| Past 30 Day Total Number of Drinks | 1.809 | 19.450 | 2.158 | 22.792 | 1.013 | 7.989 | 1.31% |

| Past 30 Day youth drank alcohol before or during work or school † | 0.019 | 0.167 | 0.020 | 0.171 | 0.017 | 0.158 | 1.27% |

| Past 30 day average number of drinks on days drank | 0.303 | 1.269 | 0.323 | 1.340 | 0.258 | 1.094 | 1.31% |

NOTES: This table presents bivariate results. Means are weighted for varying treatment random assignment ratios across time, and for attrition. Variables marked by a † are binary, so means represent proportions. Nondrinkers assigned to zero. Combined voucher treatment indicates that the low-poverty and section 8 voucher groups were combined into one group. There are no statistically-significant differences between voucher and control groups overall (when collapsed on gender).

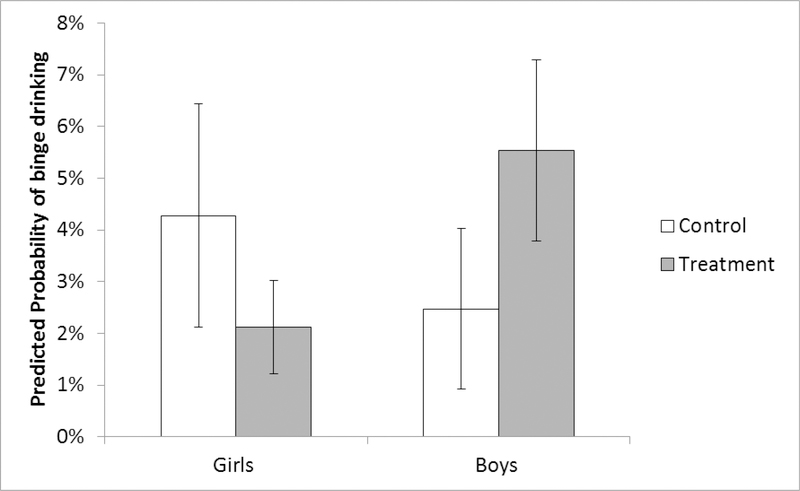

There was no main effect of treatment collapsed on gender in either crude or covariate adjusted ITT models (Supplemental Table 4, Models 1–2). This was due to strong gender effect modification, generating opposite effects for boys and girls (treatment-gender interaction p=.002) (Table 3). The voucher treatment generated beneficial effects on binge drinking for girls, but adverse effects for boys, compared to controls. Predicted probabilities of binge drinking by treatment and gender are presented in Figure 1 (Supplemental Figure presents results by 3 original randomized arms). The treatment-control risk difference (RD) on binge drinking for girls was −0.022 (95%CI: −0.044,−0.001), and for boys was 0.032 (95%CI: 0.008, 0.056).

Table 3.

MTO Treatment Effects on Adolescent Binge Drinking at Interim Survey, by Gender: Intention to Treat (ITT) and Instrumental Variable (IV) Model Results.

| ITT: MTO Voucher Treatment vs.

Control, as randomized |

IV 2nd Stage: Effect of moving

with the MTO Voucher vs. Control (Treatment on Treated) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Girls | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.96 | 0.037 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.059 |

| Boys | 2.37 | 1.13 | 4.97 | 0.023 | 5.63 | 1.12 | 28.38 | 0.036 |

NOTES: N=2790. Models control for variables associated with binge drinking, or chance baseline imbalances. Predicted treatment effects estimated with post-estimation commands from the interaction model coefficients. ITT Treatment-gender interaction: P=.002. IV models are run using 2SRI residual approach, bootstrapping for standard errors with 500 replications, using logistic regression in the 2nd stage. The F-test of the first stage association: 74, p<.001. IV Treatment-gender interaction P=.004. N girls= 1412; N boys=1378. OR=Odds Ratio. CI=Confidence Interval. Voucher treatment combines the low-poverty voucher group with the Section 8 voucher group.

FIGURE 1. Predicted Probability of Adolescent Binge Drinking by MTO Treatment Group and Gender, Intention to Treat (ITT) Analysis at Interim Evaluation.

Predicted probability of binge drinking output from post-estimation commands from covariate-adjusted ITT logistic regression models, including gender-treatment interaction, and treatment modeled as two arms (voucher treatment vs. control). Predicted probabilities reported in the figure are: Voucher Treatment Girls 2.1%; Control Girls: 4.3%; Voucher Treatment Boys: 5.5%; Control Boys: 2.5%.

IV-TOT models documented similar patterns as ITT. There were no main effects of treatment compliance on binge drinking collapsed on gender (2nd stage OR for treatment vs. control=1.27, 95%CI: 0.44, 3.66), but large gender differences emerged for effects of using the voucher on binge drinking (treatment-gender interaction p=.004). Effect sizes for IV-TOT models were about twice as large as in ITT models (Table 3). We found similar patterns for secondary alcohol outcomes in both ITT and IV models (Supplemental Tables 5–7).

The NNT for girls was −30; for every 30 girls who moved with a voucher, one fewer girl would report binge drinking versus controls. The boys’ NNH was 8; for every 8 boys moved, one additional boy would report binge drinking versus controls. For PAF, 44% of binge drinking cases would be eliminated if all families with adolescent girls living in public housing used HCV vouchers to move to private rental housing. For boys, 72% of binge drinking cases would be eliminated if all US housing choice vouchers were converted to public housing placements (See Supplemental Text 1; Supplemental Tables 8–9).

In sensitivity analyses, we documented consistency in treatment effects across the 5 cities; no tests of treatment-site interactions were significant (not reported). Moreover, adjustment for all, versus a subset of, covariates generated identical substantive findings (Supplemental Table 10; Supplemental Text 2).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that the MTO housing voucher experiment, implemented in 5 U.S. cities, profoundly affected adolescent binge drinking, with opposite patterns for girls and boys. Random assignment to receive a housing voucher, as well as actually using it to move out of public housing into a private apartment, generated beneficial effects for girls’ binge drinking, but harmful effects for boys’ binge drinking, compared to controls. The main findings were consistent across analyses using differing assumptions (e.g., ITT, IV) and were consistent across drinking outcome measures.

Our opposite-gender results are consistent with prior MTO literature among this cohort of adolescents.(15–17, 33) At the interim evaluation, MTO generated a general pattern of beneficial treatment effects for girls and harmful effects for boys on mental health, both on measures tested individually (e.g. psychological distress; behavior problems; major depression); tested as a mental health index; and on several indices of risky behaviors that combined measures of substance use (including alcohol use) and/or sexual behavior into summary scores. (15–17, 33). Other MTO evidence presented gender-stratified results for lifetime prevalence measures of risky behavior and substance use measures (e.g., intercourse, alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use), documenting an overall pattern of beneficial treatment effects for girls, but no effects for boys. But there were no treatment effects for lifetime alcohol use for either gender.(14) Only one evaluation documented any treatment effect for alcohol tested alone (past-month drinking) that was beneficial for Section 8 vs. control girls.(17) Therefore, although prior literature had tested alcohol use within risky behavior indices, it had not considered recent binge drinking as a risky substance use outcome. Binge drinking is a pattern of excessive alcohol consumption resulting in elevated blood alcohol concentration; leads to cognitive, sensory and motor impairment; and causes tissue damage in both acute and chronic use.(34) The majority of health and social consequences due to alcohol (e.g., alcohol-attributable deaths, potential life lost, economic costs) result from binge drinking.(35, 36) Any alcohol use may cause some level of impairment, but binge drinking has a much higher risk for negative outcomes than measures like lifetime or past month alcohol use.

Treatment may have influenced adolescent binge drinking in the MTO experiment via at least three potential mechanisms: improved neighborhood socioeconomic position or neighborhood quality (e.g., lower poverty rates), reduced exposure to easily-available alcohol (e.g., lower alcohol outlet density), and/or a shift in social norms regarding alcohol use (e.g., collective community normative beliefs). Although there is prior evidence supporting each pathway,(5–9) it is unclear from a theoretical perspective how these paths might generate opposite effects on alcohol use by gender. Other MTO research documented that treatment group families experienced improvements on numerous neighborhood indicators, compared to controls.(37) Since neighborhood quality rarely worsened for voucher holders, this suggests that despite improvements in neighborhood characteristics, treatment boys exhibited worse patterns of binge drinking than boys remaining in distressed public housing. The pathway from neighborhoods to risky drinking is likely not straightforward, and additional research should explore the role these mechanisms may play in the observed gender heterogeneity in alcohol misuse in MTO.

A fourth potential mechanism that may accommodate gender heterogeneity in binge drinking relates to disruptions in social relationships that influence alcohol. Although the intent of the housing voucher was to help families by moves to better housing and neighborhood contexts, moving is a documented stressor for child development,(38) and may disrupt both family and peer relationships.(39) Managing these disruptions may require effective use of coping strategies. Girls may respond better to stress by employing more effective coping strategies,(40) while boys may rely more on excessive alcohol use in response to stress.(41) Changes in the parent-child relationship may also explain gender heterogeneity in alcohol use. Parental support, attachment, and control are associated with decreased alcohol use among girls, but increased use among boys.(2, 42) To the extent that MTO induced differential changes in these parental factors, this may explain our findings.

One last possibility is that alcohol use may operate in conjunction with mental health. Binge drinking is associated with poorer mental health among adolescents and young adults.(43, 44) In MTO, mental health displays similar gendered patterns as binge drinking, and one prior study found that comorbid substance use partially mediated MTO effects on behavior problems among boys. However binge drinking was not examined, and directionality between mental health and substance use remains unclear. (45)

Qualitative research with MTO suggests additional reasons for the opposite gender effects, consistent with theories about changes in social relationships. Treatment group girls discussed how escaping high-poverty neighborhoods led to alleviating the threat of sexual violence and predation by older boys and men.(46) If girls in high poverty neighborhoods use binge drinking to cope with fear of gender violence,(47) and if that threat was alleviated by the move to lower poverty neighborhoods,(46) then our results for girls are consistent with this explanation. This mechanism is less relevant for boys. We suspect that boys experienced a more difficult integration in the new neighborhoods related to their relative social standing. If boys engaged in binge drinking to integrate into the social hierarchy of their new neighborhoods, or drank to cope with a decline in their social status, this could explain our pattern of adverse effects. More research is needed to explore the role of these specific social mechanisms.

Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV), the current iteration of Section 8 housing policy, represents the largest U.S. federal investment in affordable housing,(48) which have expanded sharply over the past two decades.(49). Yet, this policy is not uniquely American, as the vast majority of democratic nations invest in housing allowances to subsidize housing costs.(12) The primary purpose of the U.S. HCV policy is rental affordability, and therefore the voucher does not require families to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods. Although mobility promotion is a secondary goal of the policy, the ability to use the voucher to rent an apartment (also called compliance, or “leaseup”) presents one barrier to mobility, as evidenced in the 50% MTO leaseup rate. Although the leaseup rate for the low poverty treatment group was double what investigators expected, there are systematic differences between which families leased up and which did not.(27) Addressing administrative barriers (e.g., subsidy formulas disincentivizing opportunity moves) to leasing up is necessary to promote opportunity moves for low-income families.

Our research addresses a key policy question in HCV implementation: incorporating elements from non-housing sectors to improve outcomes for low-income children. Our findings suggest that although girls benefit from this policy, boys may need additional support to be successful. If the means of achieving benefits from the voucher program are the result of proximal social relationship mechanisms, rather than through broader changes to the physical and social context, boys may benefit from additional efforts to provide social support, effective coping strategies, differential parenting strategies, and inoculation against poor mental health outcomes.

Limitations.

Although we have no baseline measures of alcohol use, this is not a serious threat to internal validity for two reasons. First, the young age of the sample at baseline (mean age=10 years) precedes nearly all onset of alcohol use.(50) Second, since MTO is an RCT, most baseline covariates are balanced across treatment groups.(14) The alcohol outcomes were self-reported, so they could be measured with error given that alcohol use is illegal among youth under age 21. The survey used self-administered modules for sensitive topics including substance use,(14) which increases validity.(51) However, any measurement error would likely be nondifferential given the prospective design, thereby biasing effects towards the null. The MTO study measured binge drinking consistent with standard practice in large surveys of alcohol use at that time (5+ drinks, regardless of gender). In 2004, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism recommended a gender-specific measure that used a threshold of 4+ drinks for females. The 5-drink threshold we used underestimates female binge drinking, but would not bias the effect modification by gender observed in our study. Since there was low compliance, the ITT effects are diluted. In this case, IV models are valid for correcting effects for compliance. Yet IV models rely on several assumptions for internal validity, including the exclusion restriction,(26) which is not empirically verifiable, but is reasonable since it is temporally close to random assignment, and has been used in prior MTO analyses.(14, 17)

Generalizability of these findings may be limited since families were low income and recruited from high-poverty public housing developments. Therefore, binge drinking prevalence is lower in MTO compared to nationally-representative samples, albeit similar to that of black adolescents in the 2001 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (5.2%).(52) Nonetheless, this population is of great relevance as the target of affordable housing policy. Since housing allowances are the largest federal affordable US housing subsidy (48) and used throughout the world,(12) they represent a policy lever for changing health across sectors.

CONCLUSION

We observed that the MTO housing voucher experiment resulted in decreased risk for binge drinking and alcohol use among girls, but increased risk among boys. The specific mechanisms of action that produced these differential gender effects remain unclear. The observed findings are consistent with mechanisms associated with proximal peer and family relationships and concurrent changes in mental health, while they are less consistent with mechanisms related to changes in the neighborhood physical or social context that are not typically gender specific. Additional research should explore these mechanisms in order to better understand how to reduce or prevent adolescent alcohol use and its consequences. Policies that include supplemental efforts or services may be especially important to help boys successfully navigate residential mobility to prevent alcohol use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant acknowledgement and disclaimer. This research was supported by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant# R21 AA024530.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall WD, Patton G, Stockings E, Weier M, Lynskey M, Morley KI, et al. Why young people’s substance use matters for global health. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):265–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung RK, Toumbourou JW, Hemphill SA. The effect of peer influence and selection processes on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Health psychology review. 2014;8(4):426–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler R, Amminger G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun T. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryden A, Roberts B, McKee M, Petticrew M. A systematic review of the influence on alcohol use of community level availability and marketing of alcohol. Health & place. 2012;18(2):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins SE. Associations Between Socioeconomic Factors and Alcohol Outcomes. Alcohol research : current reviews. 2016;38(1):83–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson N, Denny S, Ameratunga S. Social and socio-demographic neighborhood effects on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of multi-level studies. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;115(0):10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryden A, Roberts B, Petticrew M, McKee M. A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health & place. 2013;21:70–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Areas of disadvantage: a systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes. Drug and alcohol review. 2011;30(1):84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osypuk TL. Future research directions for understanding neighborhood contributions to health disparities. Revue d’epidemiologie et de sante publique. 2013;61 Suppl 2:S61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28:443–78. [Google Scholar]

- 12.OECD. Public Spending on Housing Allowances. OECD Affordable Housing Database: OECD - Social Policy Division - Directorate of Employment Labour and Social Affairs, 2017.

- 13.Nguyen Q, Acevedo-Garcia D, Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL. The effects of a housing mobility experiment on participants’ residential environments. Housing Policy Debate. 2017;27(3):41948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orr L, Feins JD, Jacob R, Beecroft E, Sanbonmatsu L, Katz LF, et al. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Interim Impacts Evaluation. Washington, DC: US Dept of HUD, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osypuk TL, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Acevedo-Garcia D, Earls FJ, Lincoln AK, Schmidt NM, et al. Differential Mental Health Effects of Neighborhood Relocation among Youth in Vulnerable Families: Results from a Randomized Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1284–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osypuk TL, Schmidt NM, Bates LM, Tchetgen-Tchetgen EJ, Earls FJ, Glymour MM. Gender and crime victimization modify neighborhood effects on adolescent mental health. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):472–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica. 2007;75(1):83–119. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feins J, Holin M, Phipps A, Magri D. Implementation assistance and evaluation for the Moving to Opportunity Demonstration: final report. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates; http://www.abtassociates.com/reports/D19950045.pdf 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanbonmatsu L, Ludwig J, Katz LF, Gennetian LA, Duncan GJ, Kessler RC, et al. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Final Impacts Evaluation. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goering J, Kraft J, Feins J, McInnis D, Holin MJ, Elhassan H. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Current Status and Initial Findings. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing & Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feins JD, McInnis D. The Interim Impact Evaluation for the Moving to Opportunity Demonstration, C-OPC-21484. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates Inc, 2001. August 14, 2001. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zullig KJ, Pun S, Patton JM, Ubbes VA. Reliability of the 2005 Middle School Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(6):856–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use. 2014 Overview. Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsiatis AA, Davidian M, Zhang M, Lu X. Covariate adjustment for two-sample treatment comparisons in randomized clinical trials: A principled yet flexible approach. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:4658–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91(434):444–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shroder M Locational Constraint, Housing Counseling, and Successful Lease-up in a Randomized Housing Voucher Experiment. Journal of Urban Economics. 2002;51:315–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terza JV, Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: Addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. Journal of Health Economics. 2008;27(3):531–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klungel OH, Uddin J, de Boer A, Groenwold RH, Roes KC. Instrumental variable analysis in epidemiologic studies: An overview of the estimation methods. Pharmaceutica Analytica Acta. 2015;6:355–63. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terza JV, editor Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: A practitioners guide to Stata implementation. Stata Conference; 2016; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook RT, Sackett DL. The Number Needed to Treat: A clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310(6977):452–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinbaum DG, Sullivan KM, Barker ND. A pocket guide to epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Osypuk TL. Adolescence is a sensitive period for housing mobility to influence risky behaviors: An experimental design. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;60(4):431–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oscar-Berman M, Marinkovic K. Alcohol: effects on neurobehavioral functions and the brain. Neuropsychology review. 2007;17(3):239–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption. American journal of preventive medicine. 2015;49(5):e73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Preventing chronic disease. 2014;11:E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen QC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL. The effects of a housing mobility experiment on participants’ residential environments. Housing Policy Debate. 2017;27(3):419–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leventhal T, Newman S. Housing and child development. Children and youth service review. 2010;32(9):1165–74. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social Relationships and Health Behavior Across Life Course. Annual review of sociology. 2010;36:139–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RA, Updegraff JA. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological review. 2000;107(3):411–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Ruan WJ. The association between stress and drinking: modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 2005;40(5):453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshal MP, Chassin L. Peer influence on adolescent alcohol use: The moderating role of parental support and discipline. Applied developmental science. 2000;4(2):80–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weitzman ER. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2004;192(4):269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: association with sex and drug behavior. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004;27(3):224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Osypuk TL. Housing mobility and adolescent mental health: The role of substance use, social networks, and family mental health in the Moving to Opportunity Study. SSM - Population Health. 2017;3:318–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Popkin SJ, Leventhal T, Weismann G. Girls in the ‘hood: Reframing Safety and its Impact on Health and Behavior. Urban Affairs Review. 2010;45(6):715–44. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miranda R, Meyerson LA, Long PJ, Marx BP, Simpson SM. Sexual assault and alcohol use: Exploring the self-medication hypothesis. Violence and Victims. 2002;17(2):205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. United States Fact Sheet: Federal Rental Assistance. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,, 2015. July 6, 2015. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kingsley GT. Trends in Housing Problems and Federal Housing Assistance. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9(0):103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lessler JT, O’Reilly JM. Mode of Interview and Reporting of Sensitive Issues: Design and Implementation of Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing. NIDA Research Monograph. 1997;167:366–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 2001 (NHSDA-2001-DS0001). SAMHDA, Retrieved from https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/national-household-survey-drug-abuse-nhsda-2001nid135252001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.