Abstract

Background and purpose:

This study documents the utilization and efficacy of proton beam therapy (PBT) in western patients with localized unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods and methods:

Forty-six patients with HCC, Child-Pugh class of A or B, no prior radiotherapy history, and ECOG performance status 0-2 received PBT at our institution from 2007 to 2016. Radiographic control within the PBT field (local control, LC) and overall survival (OS) were calculated from the start of PBT.

Results:

Most (83%) patients had Child-Pugh class A. Median tumor size was 6 cm (range, 1.5-21.0 cm); 22% of patients had multiple tumors and 28% had tumor vascular thrombosis. Twenty-five (54%) patients received prior treatment. Median biologically effective dose (BED) was 97.7 GyE (range, 33.6-144 GyE) administered in 15 fractions. Actuarial 2-year LC and OS rates were 81% and 62%; median OS was 30.7 months. Out-of-field intrahepatic failure was the most common site of disease progression. Patients receiving BED ≥90 GyE had a significantly better OS than those receiving BED <90 GyE (49.9 vs. 15.8 months, p = 0.037). A trend toward 2-year LC improvement was observed in patients receiving BED ≥90 GyE compared with those receiving BED <90 GyE (92% vs. 63%, p = 0.096). On multivariate analysis, higher BED (p = 0.023; hazard ratio = 0.308) significantly predicted improved OS. Six (13%) patients experienced acute grade 3 toxicity.

Conclusions:

High-dose PBT is associated with high rates of LC and OS for unresectable HCC. Dose escalation may further improve outcomes.

Keywords: proton radiation, primary liver cancer, dose escalation

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide, with an estimated 35,660 new cases diagnosed in 2015.[1, 2] Although hepatitis B and C virus are major risk factors for the disease worldwide, they are associated with less than one third of the cases in the US. Chronic comorbidities such as alcoholic liver disease, obesity, and diabetes have been increasingly recognized as important risk factors for the development of HCC in the western population.[3] The incidence and death rates from this disease have continued to rise over the past decade, particularly in patients with underlying hepatitis C infection and cirrhosis. Despite advances in therapeutics, the overall survival (OS) is poor and remains largely stagnant, with 3-5% of patients alive at 5 years.[4] Surgical resection is potentially curative and offers the highest survival rates; however, a large number of patients are not eligible for surgery either due to anatomical restrictions, medical comorbidities or underlying hepatic dysfunction. These unresectable patients are often treated with locally ablative therapies like transarterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation and percutaneous ethanol injection, which unfortunately are suitable only in a subset of patients.

Historically, radiation therapy (RT) has not been considered feasible for localized, unresectable HCC due to the increased risk of radiation induced liver disease (RILD), especially in the setting of a low functional hepatic reserve commonly seen in these patients. With advances in RT planning and delivery, however, the possibilities for RT treatment of unresectable HCC are broadening. High dose ablative stereotactic body radiotherapy treatment (SBRT) has been shown to be safe and efficacious, with 1 year local control (LC) rates approaching 90%.[5] Heavy charged-particle therapy using protons offers another avenue for increased dose delivery to the tumor with simultaneous sparing of the surrounding healthy tissues. Proton beam therapy (PBT) offers a high degree of conformality and has a distinct dosimetric advantage compared to conventional radiation therapy using x-rays. The proton beam energy defines the depth of maximum dose at the Bragg peak. Because proton beams do not diverge significantly or deliver any dose beyond the Bragg peak, PBT treatments in general have lower integral dose. These favorable dose distributions are instrumental in the creation of treatment plans that limit the dose delivered to the uninvolved, often cirrhotic liver.[6]

Previous studies have shown high-dose hypofractionated proton therapy to be well tolerated and effective for HCC.[7-9] Patients with HCC have been treated with proton therapy at our center since 2007. Herein, we review the outcomes of these patients treated with definitive proton beam therapy (PBT).

Methods

Patient selection

We reviewed the charts of patients with localized, unresectable HCC treated with PBT at our center from 2007 to 2016. Patients had either single or multifocal tumors (up to three), no evidence of extrahepatic disease, Child-Pugh (CP) class of A or B and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 to 2. They were reviewed at the institutional multi-disciplinary tumor board where surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, diagnostic radiologists, interventional radiologists, pathologists and gastroenterologists were also present. The selection criteria for PBT versus photon treatment depend on the tumor characteristics, baseline liver function, and the insurance status. In general, PBT is considered for patients with a larger tumor dimension (single or multiple) that is >1 cm away from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract where the dose-limiting structure is likely to be the uninvolved liver rather than the GI tract, CP class of B, and when insurance approves the use of PBT. Prior therapies including chemotherapy, targeted biological therapy (e.g. sorafenib), surgery, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), percutaneous thermal ablation (i.e. radiofrequency or microwave ablation), or percutaneous ethanol injection were permitted. However, patients who had received prior radiation treatment were excluded from this study.

Treatment planning

Patients underwent four-dimensional computed tomography (4D-CT) simulation with intravenous contrast.[10, 11] In patients with inadequate renal function or history of allergy to contrast agent, simulation was performed without contrast. To ensure a consistent breathing pattern, patient education and training were provided before 4D-CT acquisition. Patients with ≤1 cm respiratory motion were treated while free breathing (N = 40), and orthogonal kV X-ray images were used for daily alignment to bony anatomy while also confirming the diaphragm position. Breathhold technique was adopted in 6 patients whose respiratory motion was greater than 1 cm, and three fiducial markers were implanted surrounding the liver tumors for imaging verification of treatment position. The relevant target volumes and normal structures were delineated and expanded to include position on all phases of the 4D CT scan (internal [structure name] or i[structure name]). Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed in cases with ill-defined tumor boundaries. The multiphase MRI images were fused with simulation CT using rigid registration based on the periphery of the liver [12]. Typically a 0-5 mm expansion of iGTV was used to create the iCTV, and edited out of surrounding structures such as chest wall. An additional margin (5-7mm) was then applied for PTV creation. In PBT planning, we avoided selecting a beam path across hollow organs or heart to minimize the range uncertainties resulting from organ deformation. Nonetheless, in certain cases with tumors close to alimentary tract, a small portion of bowel might still be included. In such circumstances, a lower dose weighting would be used for the beams across bowel lumen. Furthermore, we overrode the CT Hounsfield units of the encountered hollow organs to soft tissue versus air and to verify that neither tumor under-dose nor critical organ over-dose would occur in the most extreme conditions.

Protons were delivered using synchrotron-based passively scattered beams. The relative biological effectiveness of protons was set at 1.1 and the Gray equivalent dose (GyE) was calculated by multiplying the proton dose by this factor. The most common dose-fractionation schedules were 67.5 GyE in 15 fractions for peripheral tumors (>2 cm from porta hepatis) and 58 GyE in 15 fractions or 66 GyE in 20 fractions for central tumors (≤2 cm of porta hepatis).[7] The prescription dose was sometimes decreased for areas of the treatment field in close proximity to critical structures (e.g. istomach, ismall bowel, etc.). Normal tissue constraints varied based on the fractionation schedule. Constraints were also personalized depending on the volume and function of the patient’s remaining liver. Generally, for a 15 fraction treatment, constraints were as follows: mean dose for normal liver (liver-GTV) < 24 GyE, V20 kidney < 33%, Dmax stomach and duodenum < 45 GyE, Dmax common or main bile duct < 70 GyE, Dmax colon < 50 GyE. One patient who received 67.5 GyE in 15 fractions had a mean dose to liver-GTV of 27.5 GyE. Some of these patients were treated on a prospective protocol where they received 67.5 GyE in 15 fractions.

Follow up

After completion of PBT, patients were typically followed every 3 months for the first 2 years and then every 6 months thereafter. Follow up visits included history and physical examination as well as blood counts, serum chemistries and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) measurements. CT or MRI scans were typically performed every 6 months for the first 2 years and annually afterwards. Acute toxicities, occurring within three months from PBT start, were prospectively recorded and verified retrospectively according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), version 4.03.[13] Radiation-induced liver disease (RILD) was defined as ascites with elevation of alkaline-phosphatase for more than twice the upper normal threshold (classic type), grade ≥3 CTCAE hepatic toxicity or a worsening of CP score by ≥2 (non-classic type), in the absence of intrahepatic tumor progression within 4 months after PBT [14-17].

Statistical Analysis

LC was defined as survival in the absence of radiographic tumor progression within the radiation treatment field. Any recurrences outside the treatment field but within the liver, as well as those outside the liver (regional nodes, distant metastatic sites) were considered as distant failures. LC, overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were calculated from the start of PBT. OS was censored at the date of last follow up on record if death was not observed, while PFS was censored at the date of the last follow up on record if no recurrence (local or distant) or death was observed. OS and LC rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the differences between groups were compared using log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards model with a stepwise forward conditional manner was used for multivariate analysis, and variables were retained in the model if their significance levels were <0.10. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) and a two tailed p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 46 patients were treated with PBT during the study period. The median age at diagnosis was 72 years (range, 52-90 years). Eighty-three percent of patients had a CP class of A, and a majority (98%) had performance status of 0 or 1. Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) grade A and B were recorded in 42% and 54% of patients, respectively.[18] Twenty-eight percent of patients had hepatitis C, 4% had hepatitis B, 52% had alcohol-related liver disease, and 13% had non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Median alpha fetoprotein level was 14.5 ng/mL (range, 1.2-73,321.9 ng/mL) prior to treatment and decreased to 6.1 ng/mL (range, 1.7-22,521.3 ng/mL) within 3 months following treatment. Twenty-five (54%) patients received previous treatment which primarily included transarterial chemoembolization (TACE, 11 patients), sorafenib (4 patients) or both (6 patients), and 10 patients presented with recurrent disease prior to PBT. Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 72 |

| Range | 52-90 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 34 (74) |

| Female | 12 (26) |

| Race | |

| White | 25 (54) |

| Non-white | 21 (46) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 20 (44) |

| 1 | 25 (54) |

| 2 | 1 (2) |

| Child-Pugh score | |

| 5 | 26 (57) |

| 6 | 12 (26) |

| 7 | 6 (13) |

| 8 | 2 (4) |

| ALBI grade | |

| 1 | 19 (42) |

| 2 | 25 (54) |

| 3 | 2 (4) |

| Etiology of liver disease | |

| HCV (± others) | 13 (28) |

| HBV (± others) | 2 (4) |

| Alcoholic (± others) | 24 (52) |

| NAFLD (± others) | 6 (13) |

| None | 9 (20) |

| Alfa fetoprotein (ng/mL) | |

| Median | 14.5 |

| Range | 1.2-73,321.9 |

| Disease status | |

| Newly diagnosed | 36 (78) |

| Locally recurrent | 10 (22) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Tumor and Treatment characteristics

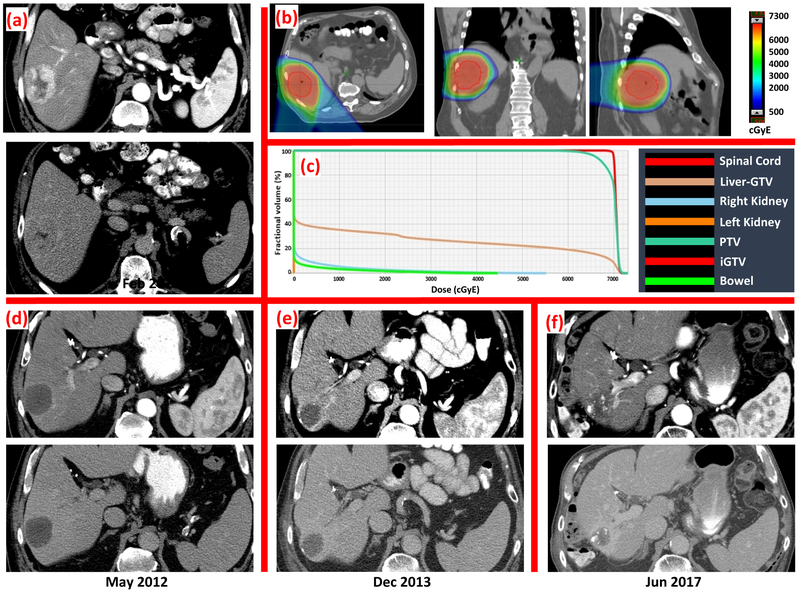

Median tumor size was 6 cm (range, 1.5-21.0 cm) with multiple tumors present in 22% of patients. Tumor vascular thrombus was present in 13 (28%) patients. Median radiation dose and fraction number was 67.5 GyE (range, 24.0-91.0 GyE) in 15 fractions (range, 6-25 fractions), delivered over a median duration of 21 days (range, 6-47 days). Correcting for differences in number of fraction using a tumor alpha/beta ratio of 10, the median biologically effective dose (BED) was 97.7 GyE (range, 33.6-144.0 GyE), and 44 patients (96%) received BED >50 GyE. No significant difference in GTV was observed between BED ≥90 GyE and <90 GyE groups (332 ± 614 vs. 466 ± 592 ml, P = 0.457). Concurrent sorafenib was administered in four patients. The mean liver dose for the entire group had a median of 23.3 GyE (range, 5.3-48.4 GyE) and that for the mean liver-GTV dose was 18.6 GyE (range, 5.0-27.5 GyE). Five patients did not complete the intended radiation treatment course due to sepsis (N = 2), tumor progression (N = 1), intolerance of breathhold technique (N = 1), and personal reasons (N = 1). Table 2 summarizes tumor and treatment characteristics. As an example, an 85-year-old female with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was diagnosed with a 9.5 cm hepatocellular carcinoma in segment IVA of the liver which was treated with definitive PBT to a total dose of 67.5 GyE in 15 fractions (Figure 3). Post-treatment imaging showed a decrease in size and density of the mass, consistent with response to radiation. Imaging 2.5 years post-treatment confirmed continued decrease in lesion size with no other hepatic lesions.

Table 2:

Tumor and Treatment characteristics

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| Median | 6.0 |

| Range | 1.5-21.0 |

| >10 cm | 10 (22) |

| 5-10 cm | 16 (34) |

| <5 cm | 20 (44) |

| Number of lesions | |

| Single | 36 (78) |

| Multiple | 10 (22) |

| Tumor vascular thrombosis | |

| Present | 13 (28) |

| Absent | 33 (72) |

| Portal vein tumor thrombosis | |

| Present | 9 (20) |

| Absent | 37 (80) |

| Previous therapy | |

| Surgical resection (± others) | 2 (4) |

| Transcatheter chemoembolization (± others) | 17 (37) |

| Radiofrequency ablation (± others) | 2 (4) |

| Chemotherapy (± others) | 11 (24) |

| Yttrium-90 microspheres | 1 (2) |

| None | 21 (46) |

| Radiation dose (GyE) | |

| Median | 67.5 |

| Range | 24.0-91.0 |

| Dose fractionation | |

| 67.5 GyE in 15 fractions | 19 (41) |

| 58 GyE in 15 fractions | 7 (15) |

| 66 GyE in 20 fractions | 5 (11) |

| Other | 15 (33) |

| BED (GyE) | |

| Median | 97.7 |

| Range | 33.6-144.0 |

| Mean dose to uninvolved liver (GyE) | |

| Median | 18.6 |

| Range | 5.0-27.5 |

| Gross tumor volume (mL) | |

| Median | 149.5 |

| Range | 7.5-2,927.9 |

| Normal liver volume (mL) | |

| Median | 1435.7 |

| Range | 773.8-2,725.8 |

Figure 3:

Representative pre-treatment arterial and delayed CT images, PBT plan, and serial post-treatment arterial and delayed CT images of a 85-year-old female patient with a 9.5 cm hepatocellular carcinoma treated to 67.5 GyE in 15 fractions. The red contour on dose-color-wash represents iGTV. Imaging 2.5 years post-treatment showed no enhancement on the arterial and delayed phase, decrease in size and development of calcification.

Recurrence and Survival Analysis

The median follow up was 14.5 months (range, 0.4-59.8 months) for all the study participants. The median OS was 30.7 months (95% confidence interval, CI, 12.6-48.9 months) with 1-year and 2-year OS rates of 73% and 62%, respectively (Figure 1). The 1-year and 2-year PFS rates were 74% and 57%, respectively. The LC rate at 1 and 2 years were 95% and 81%, respectively. Patients with tumor diameter ≥5 cm had a significantly lower 2-year LC rate compared with those with <5 cm tumors (62% vs. 100%, p = 0.034). Thirty-two (70%) patients had no evidence of progression at the time of last follow up. In the 14 patients with evidence of progression, the first site of recurrence was local (within the RT field) in 4 patients, intrahepatic but outside RT field in 6 patients, extrahepatic and distant sites in 3 patients, and synchronous intrahepatic (outside field) and distant in 1 patients. Univariate associations of OS are summarized in table 3. Patients who received a higher dose (BED ≥90 GyE) had a better OS compared to patients who received lower dose (BED <90 GyE) (49.9 vs. 15.8 months, p = 0.037) (Figure 2). In addition, we observed a trend toward 2-year LC improvement in patients receiving BED ≥90 GyE than those receiving BED <90 GyE (92% vs. 63%, p = 0.096). On multivariate analysis, higher BED (p = 0.023, HR = 0.308) was identified as independent predictor of improved OS. Nine patients underwent further treatment following RT including sorafenib (5 patients), TACE (3 patients), radiofrequency ablation (2 patients), percutaneous ethanol injection and phase I investigational drug MRX-34 (1 patient each).

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival for all 46 patients

Table 3:

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for local control and overall survival

| Prognostic Factor | Local control | Overall survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | N | 2-year(%) | P value | 2-year (%) | P value | |

| Age | <65 years | 17 | 86 | 0.858 | 70 | 0.376 |

| ≥65 years | 29 | 77 | 59 | |||

| ECOG performance status | 0 | 20 | 83 | 0.330 | 64 | 0.894 |

| 1-2 | 26 | 79 | 61 | |||

| Child-Pugh class | A | 38 | 84 | 0.327 | 61 | 0.534 |

| B | 8 | 75 | 71 | |||

| ALBI grade | 1 | 19 | 79 | 0.747 | 82 | 0.269 |

| 2-3 | 27 | 88 | 42 | |||

| Tumor vascular thrombus | Absent | 33 | 77 | 0.323 | 67 | 0.106 |

| Present | 13 | 100 | 44 | |||

| Portal vein tumor thrombosis | Absent | 37 | 78 | 0.400 | 68 | 0.087 |

| Present | 9 | 100 | 38 | |||

| Tumor size | <5 cm | 20 | 100 | 0.034 | 62 | 0.830 |

| ≥5 cm | 26 | 62 | 62 | |||

| Number of lesions | single | 36 | 76 | 0.276 | 63 | 0.844 |

| multiple | 10 | 100 | 60 | |||

| Prior treatment | No | 21 | 71 | 0.251 | 79 | 0.091 |

| Yes | 25 | 91 | 48 | |||

| Biological equivalent dose | <90 GyE | 20 | 63 | 0.096 | 47 | 0.037 |

| ≥90 GyE | 26 | 92 | 75 | |||

| Multivariate analysis | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Biological equivalent dose | ≥90 vs. <90 GyE | – | NS | 0.308(0.112-0.848) | 0.023 | |

| Prior treatment | No vs. Yes | – | NS | 0.334(0.112-1.001) | 0.050 | |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival stratified by biologically effective dose of radiation

Toxicity Analysis

The most common toxicities were grade 1 fatigue (33%), skin erythema (24%), nausea (22%), anorexia (11%) and vomiting (13%) (Table 4). Acute grade 3 toxicities were recorded in 6 (13%) patients; specifically, non-malignant ascites in 4 patients (9%), hyperbilirubinemia in 2 patients (4%) and, diarrhea and upper GI bleed in 1 patient (2%) each. Within 4 months of PBT completion, a worsening of CP score was documented in 6 patients (13%) without evidence of hepatic tumor progression. Four (9%) of them had a worsening of CP score by 2 or more (i.e. non-classic RILD), and the other 2 patients (4%) experienced transient CP score elevation by 1. No grade ≥3 CTCAE hepatic toxicity, hepatitis viral flare-up or reactivation (judged by viral load) or classical RILD was recorded in our study. Table 4 summarizes radiation-related toxicities.

Table 4:

Radiation-related toxicities

| Toxicity | Any Grade, % (No.) | Grade 3, % (No.) |

|---|---|---|

| Anorexia | 11 (5) | |

| Nausea | 22 (10) | |

| Vomiting | 13 (6) | |

| Fatigue | 33 (15) | |

| Right upper quadrant pain | 7 (3) | |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (4) | |

| Diarrhea | 11 (5) | 2 (1) |

| Constipation | 4 (2) | |

| Erythema | 24 (11) | 2 (1) |

| Ascites (nonmalignant) | 11 (5) | 9 (4) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 11 (5) | 4 (2) |

| Cough | 4 (2) | |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that high-dose proton beam therapy (PBT) is associated with high rates of LC and OS for unresectable HCC and can be delivered safely in appropriately selected patients.

The use of conventional radiation therapy for HCC has traditionally been limited by the inability to deliver effective dose to the tumor without compromising the surrounding uninvolved liver. Given that the majority of these patients have underlying liver disease and dysfunction that inherently limits survival, it is imperative that post-treatment hepatic function is preserved using more precise radiation delivery techniques.[8] Through the use of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), tumoricidal doses can be delivered in a highly conformal manner. SBRT has been shown to offer excellent 1-year LC rate of 87% and median OS of 17 months and is currently being evaluated in combination with sorafenib in a phase III trial for HCC (NCT 01730937).[5]

Protons offer a dosimetric advantage compared to X-rays primarily due to distinct physical attributes, which allow the deposition of dose over a relatively short distance (Bragg peak) with no exit dose along the beam path. Contrary to X-rays, protons have a finite range in tissue which is dependent on the initial proton beam energy. By modulating the beam energy and the number of beams, protons can be manipulated to cover large targets while keeping critical structures under tolerance doses.[6] Dosimetric comparison studies have shown better sparing of the uninvolved liver (volume of the liver receiving at least 30 GyE and the mean liver dose) as well as the surrounding viscera (stomach, duodenum, spinal cord, heart and kidneys) with protons vs. conventional X-ray therapy.[19] These unique and favorable dose distributions offer a host of benefits in the HCC population including better tolerability during treatment, and better sparing of the remaining liver to allow the possibility for retreatment in cases of recurrence. In addition, the decreased dose to surrounding normal tissue minimizes the risk of late radiation sequelae.[20]

Because of these advantages, protons have been employed in the treatment of unresectable HCC and have demonstrated encouraging outcomes. In Japan, protons have been used for treating HCC since 1985 and both retrospective and prospective studies have found PBT to be well-tolerated and effective.[8, 21-24] Chiba et al. in a large retrospective review reported the outcomes of 162 unresectable HCC patients treated with a median dose of 72 GyE in 16 fractions from 1985-1998. The authors reported excellent 5-year LC and OS rates of 86.9% and 23.5%, respectively.[24] Following this, these authors evaluated the safety and efficacy of hypofractionated PBT (median dose of 66 GyE in 10 fractions) in a prospective setting and reported 5-year LC and OS rates of 87.8% and 38.7%, respectively.[23] In both these studies, the patients had very few treatment-related toxicities. Similarly, Kawashima et al. studied the use of PBT administered in doses of 76 GyE in 20 fractions (median dose) in 30 patients with solitary HCCs and reported 2-year local progression-free survival and OS rates of 96% and 66%, respectively.[8] In this study, no grade 2 or higher gastrointestinal toxicity was observed.

The use of PBT for treatment of HCC in the United States is relatively recent, and limited due to its availability only at select centers. In a phase II trial, Bush et al. treated 34 unresectable HCC patients with a median dose of 63 GyE in 15 fractions and reported 2-year LC and OS rates of 75% and 55%, respectively. The authors did not observe any radiation-induced liver disease; 60% of patients were noted to have mild (grade 1-2) acute radiation-related toxicities.[25] In a subsequent follow up study of 76 patients, Bush et al. reported a 3-year PFS rate of 60% in patients meeting the Milan criteria.[9] A recent multi-institutional phase II trial of high-dose hypofractionated PBT (58 GyE in 15 fractions) in 44 HCC patients reported 2-year LC and OS rates of 94.8% and 63.2%, respectively.[7] Our results, with high LC and OS rates, and low toxicities are concordant with data from previous PBT studies for HCC.

In our study, the median OS was 30.7 months with 2-year LC and OS rates of 81% and 62%, respectively. These results are encouraging considering that our dataset included a high percentage of patients with risk factors known to portend poor prognosis like multiple lesions, large tumors, presence of portal vein tumor thrombosis, and CP class of B.[8, 26, 27] In photon radiotherapy, de-escalation of the target dose to comply with the mean live dose constraints is usually necessitated for patients with larger tumors, multiple lesions, portal vein tumor thrombosis as well as pre-existing liver dysfunction, and this could result in significantly inferior survival outcomes [28-31]. In PBT, however, since the “low dose bath” associated with X-rays is eliminated, ablative doses could be safely deposited to the tumors without jeopardizing the remaining liver parenchyma [32-34]. The favorable survival results in our patients indicate that the dosimetric advantages of protons broaden the therapeutic window and pave a new avenue for curative intent treatment for these poor prognostic patient subgroups

On adjusting for all potential prognostic factors, higher dose BED ≥90 GyE was an independent predictor of improved OS. This is similar to previous studies in the liver as well as other body sites where RT dose escalation has been associated with improved outcomes.[31, 35, 36] Of the 14 patients who developed recurrence, the most common (6 patients) site of initial recurrence was intrahepatic, but outside the treatment field. This high rate of out of field liver failure is likely due to the insidious nature of the disease, as patients likely have microscopic disease present but undetectable with current imaging techniques at the time of radiation treatment planning or new lesions arising in a cirrhotic background. In our study, although tumor vascular thrombosis was not a significant prognostic factor, the 13 patients who had tumor vascular thrombosis had a 1-year and 2-year OS rate of 58% and 44%, respectively. This is relatively higher than the rates seen in studies utilizing transcatheter infusion chemotherapy and may support the consideration of PBT as a preferred treatment modality in patients with vascular invasion.[26, 37]

Since the PBT planning has to account for deformation-related range uncertainties, a wider high-dose treatment margin is frequently required compared with SBRT. Thus, PBT may not be an ideal radiation modality for patients with tumors abutting GI tract wherein a compromised target dose in the vicinity of bowel is almost mandated. Therefore, photon therapy is a preferred treatment of choice for patients with tumors <1 cm away from the bowel in our institute. Lastly, cost is definitely an issue with protons. SBRT, while more expensive than standard fractionation photons, is cheaper than protons. The relative added benefit of protons (if any) over SBRT remains to be established and until that case is made conclusively, the advantages of proton therapy are theoretical and the disadvantages are quite self-evident (i.e., range uncertainty, greater susceptibility to motion issues, cost, etc). A true comparison between PBT and SBRT should also use IMPT rather than passively scattered protons. We hold a treatment modality agnostic view and think of the beam delivery technique only as a tool to achieve a clinically desired outcome – highest possible dose to the tumor with the least risk of toxicity. Notably, in the current study, acute severe toxicity was minimal with a grade 3 GI toxicity rate of 13%. Only 1 patient developed an upper GI bleed before and during the course of PBT, indicating that the risk of bowel complications could be minimized with protons, with respect to normal tissue constraints. Following treatment, only 13% of our patients had a decline in liver function with a worsening of the CP score by one or more. This number is remarkably lower than that of the SBRT series which a worsening in CP class was observed in 29% of patients at post-irradiation 3 months in the absence of intrahepatic tumor progression.[5] The lower rate of hepatic complications further highlights the dosimetric advantages of protons for patients with pre-existing liver morbidity.

Our study does have potential limitations. The retrospective nature of the analysis with varied patient and treatment characteristics may impact the wider application of these results. Despite these limitations our data are encouraging. Outcome and toxicity data for PBT use in patients with HCC in the United States is limited mainly because of its availability only at specialized centers. Although larger studies of PBT treatment for HCC have been performed in Asian populations, these results may not be generalizable to the western population, which comprises patients with markedly different risk factors for HCC and comorbidities. Thus, studies analyzing the safety and outcomes of PBT in this population are essential. Only two phase II studies of PBT have been published so far for HCC patients in the United States.[7, 9] Of these, the study by Bush et al. included patients with relatively advanced decompensated liver disease (24% patients with CP score ≥10).[9] The current study represents a relatively large homogenous cohort of patients selected for treatment with high-dose PBT. The outcome and toxicity data are in line with previously published studies and support the continued investigation of PBT in localized unresectable HCC. Future randomized trials investigating the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of PBT, especially compared to X-ray radiotherapy, transarterial chemoembolization or sorafenib, are needed to better define the role of PBT in these patients.

In conclusion, high-dose PBT is effective and well-tolerated in appropriately selected unresectable HCC patients. The unique advantage of protons in terms of biological effectiveness and normal tissue sparing allows for the treatment of patients with inherently compromised liver function who would not otherwise be candidates for radiation therapy. PBT should be considered as a potential definitive treatment option for unresectable HCC patients.

Highlights:

In a Western world cohort of moderate-to-large unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with passively scattered proton beams, median overall survival was a healthy 30.7 months and actuarial 2-year local control and overall survival rates were 81% and 62%.

Overall survival was better in patients receiving a biologically effective dose of greater than 90 GyE.

Toxicity was minimal.

The ability to escalate radiation dose to the tumor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma by using proton beam therapy may yield excellent overall outcomes, making this a promising treatment option worth considering for some patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center support grant P30 CA16672 and funding from the John E. and Dorothy J. Harris Endowed Professorship (to S.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology in Boston.

No conflicts of interest

Writing assistance: none

References

- 1.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012; 379: 1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Society AC. Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. Atlanta, Ga: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the United States: Where Are We? Where Do We Go? Hepatology 2014; 60: 1767–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2003; 362: 1907–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bujold A, Massey CA, Kim JJ et al. Sequential phase I and II trials of stereotactic body radiotherapy for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 1631–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner HD, Hong TS, Krishnan S. Charged-particle therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Radiat Oncol 2011; 21: 278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong TS, Wo JY, Yeap BY et al. Multi-Institutional Phase II Study of High-Dose Hypofractionated Proton Beam Therapy in Patients With Localized, Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawashima M, Furuse J, Nishio T et al. Phase II study of radiotherapy employing proton beam for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1839–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush DA, Kayali Z, Grove R, Slater JD. The safety and efficacy of high-dose proton beam radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase 2 prospective trial. Cancer 2011; 117: 3053–3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beddar AS, Briere TM, Balter P et al. 4D-CT imaging with synchronized intravenous contrast injection to improve delineation of liver tumors for treatment planning. Radiother Oncol 2008; 87: 445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Krishnan S, Wang X et al. Improving soft-tissue contrast in four-dimensional computed tomography images of liver cancer patients using a deformable image registration method. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 72: 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang DS, Yoon WS, Lee JA et al. The effectiveness of gadolinium MRI to improve target delineation for radiotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparative study of rigid image registration techniques. Phys Med 2014; 30: 676–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SERVICES USDOHAH. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.03. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan CC, Kavanagh BD, Dawson LA et al. Radiation-Associated Liver Injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 76: S94–S100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng JC-H, Liu H-S, Wu J-K et al. Inclusion of biological factors in parallel-architecture normal-tissue complication probability model for radiation-induced liver disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 62: 1150–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A et al. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol 2003; 13: 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson LA, Normolle D, Balter JM et al. Analysis of radiation-induced liver disease using the Lyman NTCP model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 53: 810–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 550–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Krishnan S, Zhang X et al. Proton radiotherapy for liver tumors: dosimetric advantages over photon plans. Med Dosim 2008; 33: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taddei PJ, Howell RM, Krishnan S et al. Risk of second malignant neoplasm following proton versus intensity-modulated photon radiotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Phys Med Biol 2010; 55: 7055–7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizumoto M, Okumura T, Hashimoto T et al. Proton Beam Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comparison of Three Treatment Protocols. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 81: 1039–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu S, Fukumoto T, Demizu Y et al. Clinical results and risk factors of proton and carbon ion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2011; 117:4890–4904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukumitsu N, Sugahara S, Nakayama H et al. A prospective study of hypofractionated proton beam therapy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009; 74: 831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiba T, Tokuuye K, Matsuzaki Y et al. Proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective review of 162 patients. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 3799–3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bush DA, Hillebrand DJ, Slater JM, Slater JD. High-dose proton beam radiotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: preliminary results of a phase II trial. Gastroenterol 2004; 127: S189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hata M, Tokuuye K, Sugahara S et al. Proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Cancer 2005; 104: 794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee HS, Kim JS, Choi IJ et al. The safety and efficacy of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and main portal vein obstruction. A prospective controlled study. Cancer 1997; 79: 2087–2094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bibault J-E, Dewas S, Vautravers-Dewas C et al. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Prognostic Factors of Local Control, Overall Survival, and Toxicity. PLOS ONE 2013; 8: e77472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lausch A, Sinclair K, Lock M et al. Determination and comparison of radiotherapy dose responses for hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic colorectal liver tumours. Br J Radiol 2013; 86: 20130147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang WI, Kim M-S, Bae SH et al. High-dose stereotactic body radiotherapy correlates increased local control and overall survival in patients with inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiat Oncol 2013; 8: 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park HC, Seong J, Han KH et al. Dose-response relationship in local radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 54: 150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toramatsu C, Katoh N, Shimizu S et al. What is the appropriate size criterion for proton radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma? A dosimetric comparison of spot-scanning proton therapy versus intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol 2013; 8: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen JBB, Lassen Y, Hansen AT et al. Normal liver tissue sparing by intensity-modulated proton stereotactic body radiotherapy for solitary liver tumours. Acta Oncologica 2011; 50: 823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Krishnan S, Zhang X et al. Proton Radiotherapy for Liver Tumors: Dosimetric Advantages Over Photon Plans. Medical Dosimetry 2008; 33: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dawson LA, McGinn CJ, Normolle D et al. Escalated focal liver radiation and concurrent hepatic artery fluorodeoxyuridine for unresectable intrahepatic malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 2210–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishnan S, Chadha AS, Suh Y et al. Focal Radiation Therapy Dose Escalation Improves Overall Survival in Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Patients Receiving Induction Chemotherapy and Consolidative Chemoradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016; 94: 755–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaneko S, Urabe T, Kobayashi K. Combination chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma complicated by major portal vein thrombosis. Oncology 2002; 62 Suppl 1: 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]