Abstract

Background

Imbalanced activation of the cardiac autonomic nervous system (CANS) triggers postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF). Neuronal calcium overload induces apoptosis. We hypothesize that epicardial injection of timed-release nanoformulated-CaCl2 (nCaCl2) into LA ganglionic plexi (GP) modulates autonomic function and suppresses POAF.

Objective

Determine whether nCaCl2 GP therapy suppresses POAF.

Methods

We utilized a novel canine model of POAF with implanted radiotelemetry to record nerve activity (NA) from left stellate ganglion (SNA), vagus (VNA), and GP (GPNA). At week 3 (PO-3wk), nCaCl2 (n=7) or vehicle-control (sham, n=3) was injected into left pulmonary vein (PV) GP (LGP), followed by right PV GP (RGP) at week 4. Atrial effective refractory period (AERP) and atrial fibrillation vulnerability (AFV) were assessed in-vivo. Resting and exercise NA and HR were assessed before and after LGP treatment.

Results

AERP decreased (p<0.0001) and AFV increased (p=0.008) at PO-3wk vs baseline. However, nCaCl2-LGP-treatment reversed these changes and restored them to baseline after 1 week (p=0.04). Subsequent nCaCl2-RGP-treatment reduced AFV further (p=0.03). In contrast, AFV increased (p=0.001) and AERP remained decreased (p=0.01) 1 week after sham-LGP treatment vs baseline. nCaCl2-LGP-treatment reduced GPNA (p<0.02) and VNA (p<0.05) and increased SNA (p<0.02). Despite increased SNA, HR was decreased (p<0.01) with loss of HR-SNA correlation (R=0.62). After sham-LGP treatment, NA was unchanged and HR-SNA remained correlated (R=0.95). Histology confirmed nCaCl2-GP co-localization, apoptosis and loss of immunoreactivity in nCaCl2-treated soma.

Conclusion

Epicardial injection of nCaCl2 into LA GP induced neuroapoptosis and modulated autonomic function. This reversed a postoperative reduction in AERP and suppressed POAF.

Keywords: postoperative atrial fibrillation, autonomics, cardiac surgery, neural modulation, chronic animal model

Introduction

Imbalanced activity in sympathetic and parasympathetic arms of the cardiac autonomic nervous system (CANS) triggers AF1,2 and POAF3. The post-cardiac surgery state is characterized by sympatho-excitatory surge along with inflammatory, metabolic and hemodynamic derangements that activate cholinergic neural elements of the heart3 and promote POAF.1,2 Therefore, targeted CANS modulation could be anti-arrhythmic against POAF.4–6 The CANS consists of intrinsic and extrinsic components, the intrinsic being a network of multiple ganglionated plexi (GP) and interneurons located within subepicardial fat pads including those adjacent to pulmonary veins.4,5 We hypothesize that CaCl2, when encapsulated within timed-release nanoparticles (nCaCl2) and injected epicardially into GP, will modulate GP function and suppress POAF vulnerability. Targeted GP therapy using a ubiquitous substance such as calcium, can be administered during open heart surgery, would advantageously avoid the myocardial damage caused by radiofrequency ablation and potentially induce sustained effects on CANS and POAF.

Calcium ions, though essential for cellular function, are excessively internalized by neurons when exposed to greater than 0.1mM in the presence of L-glutamate.6 L-glutamate binds neuronal NMDA receptors enhancing neuronal calcium internalization.6 The resulting increased intracellular calcium concentration triggers neuroapoptosis,6 providing persistent CANS modulation. We have previously formulated CaCl2 with trace L-glutamate into polymeric nanoparticles consisting of poly-(lactide-co-glycolide)(PLGA)7 for burst followed by extended release after injection into GP and warming to body temperature. This enables specific targeting of GP and prolonged neural exposure to high calcium concentrations, while avoiding neighboring tissues. The goal of this study was to determine whether epicardial injection of nCaCl2 into LA GP, inhibited their function and suppressed POAF, whilst being non-toxic to adjacent myocardium. To achieve these goals, we developed a novel canine model of POAF with sequential survival thoracotomies, which creates a substrate for AF due to successive postoperative injury and repair, and enabled chronic assessments of nCaCl2 effects on AF vulnerability (AFV) and CANS function.

Methods

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. We studied 10 Mongrel canines (20–30kg).

First surgery - radiotelemetry implantation and electrophysiology study:

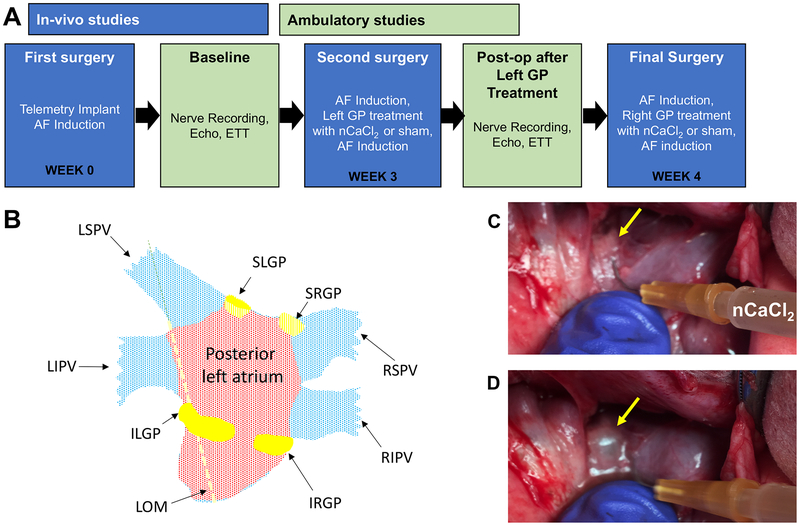

Figure 1A diagrams the experimental timeline. Animals were induced with intravenous sodium methohexital, and anesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane for a left thoracotomy. A radiotelemetry device (Data Sciences International, Minneapolis, MN) was implanted to record HR and autonomic nerve activity (NA) from the left stellate ganglion (SNA), left cardiac vagus nerve (VNA), and GP (GPNA). Electrophysiology study (EPS) was performed to determine pacing thresholds, AERP, and AFV at three LA sites: anterior LA (ALA), LA appendage (LAA), and posterior LA (PLA) (Figure 1B) using an electrical stimulator.2 GP were identified by: (1) visualization of epicardial fat pad at the antrum of the pulmonary vein (PV)4 (yellow arrow, Figure 1C) and (2) high frequency subthreshold stimulation (HFS) at 20Hz for 10 seconds,2 that evoked a 5% decrease in HR. The chest was closed and the animal recovered for 24 hours prior to the ambulatory recordings of NA and HR.

Figure 1. Experimental Protocol.

(A) Timeline of study. (B) Posterolateral view of LA structures. LAA and ALA (not visible) are located anterolateral to LGP. Abbreviations: LSPV and LIPV: left superior and inferior pulmonary veins; SLGP and ILGP: superior and inferior left GP; LOM: Ligament of Marshall; PLA, ALA, LAA: posterior LA, anterior LA, LA appendage, respectively. GP (yellow arrow) prior to (C) and after injection of nCaCl2 (D), showing the characteristic bleb.

Atrial fibrillation vulnerability score:

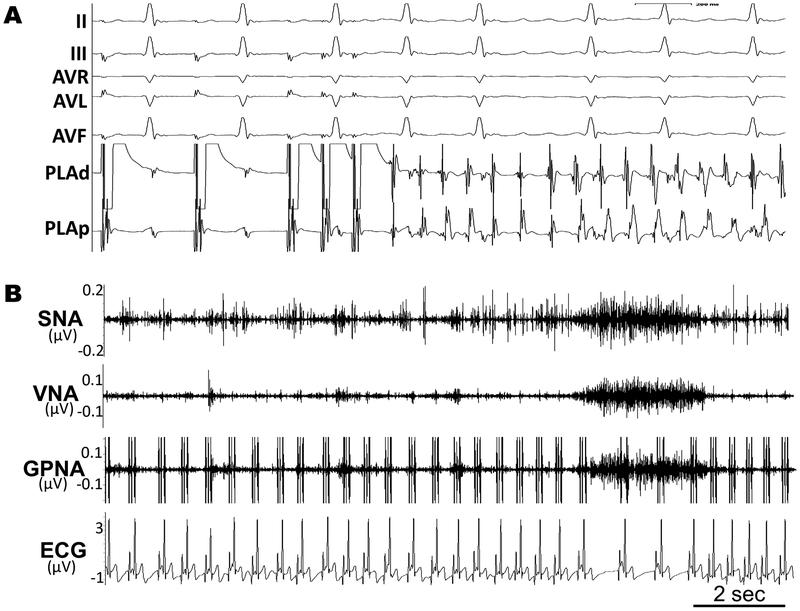

Figure 2A is an example of AF induced by atrial double extra-stimuli. All induced atrial arrhythmias with CL <200ms were defined as AF. AFV was quantitatively scored using an algorithm modified from the concept of AF window of vulnerability,2 as further described in the data supplement.

Figure 2.

(A) Programmed stimulation to induce AF. (B) Representative NA recordings from left stellate ganglion (SNA), cardiac vagal nerve (VNA), and left inferior ganglionic plexi (GPNA) during normal activity.

Autonomic Nerve Activity (NA):

Ambulatory NA recordings began 24 hours after surgery to minimize residual NA suppression from anesthesia. Figure 2B is a sample of NA showing the association between ambulatory NA and HR. A 72-hour period of recordings were obtained at rest after the first surgery (Pre-LGP tx) and repeated after second surgery (Post-LGP tx) i.e., after LGP treatment with nCaCl2 or vehicle control (sham). NA and HR were also recorded during exercise tolerance testing (ETT). Methods for analyzing NA1 are detailed in the data supplement.

Echocardiography and Exercise Tolerance Testing:

Refer to the data supplement for details.

Second surgery - nCaC2 left-sided GP treatment and repeat electrophysiology study:

A second left thoracotomy was performed 3wks after first surgery (Figure 1A). EPS and HFS of the LGP (Figure 1B) were repeated (Pre-LGP tx). The LGP were each injected (Figure 1C and 1D) with either: 1) 1ml of nCaCl2 consisting of PLGA particles (230 nm), carrying magnetite particles (14 nm) for histological tracing and a payload of0.5mM CaCl2 with trace L-glutamate, or 2) 1ml of vehicle control containing PLGA particles and magnetite only. The formulation was designed to produce local extracellular Ca++ concentrations of 0.27mM at targeted GP sites.7 Injection produced a bleb in the fat pad without bleeding (Figure 1D), confirming an epicardial injection plane. After 1hr, the EPS was repeated (1 hr Post-LGP tx). Successful GP injections were confirmed by the loss of evoked HR response to HFS. The thoracotomy was closed and the animal recovered.

Final surgery - right-sided GP treatment and repeat electrophysiology study:

A left thoracotomy was performed 1 week after second surgery. EPS was repeated (1wk Post-LGP tx) to determine the 1 week effects of LGP treatment. A right thoracotomy was then performed to administer nCaCl2 or the sham into the right PV GP (RGP). After 1 hour, EPS was repeated (1 hr Post-RGP tx). The animals were euthanized and tissues fixed in 4% formalin overnight, then stored in 70% alcohol.

Histological studies:

Tissue segments containing GP were paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnetite (Fe3O4) was added to nCaCl2 to disclose localization of PLGA particles within GP (Prussian blue reaction). Tunel staining was performed to confirm apoptosis. Immunostaining with Tyrosine Hydroxylase and Choline Acetyltransferase antibodies was used to differentiate adreno-cholinergic neurons,5 as further described in the data supplement.

Statistical analysis:

Statistical methods are described in detail in the data supplement. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

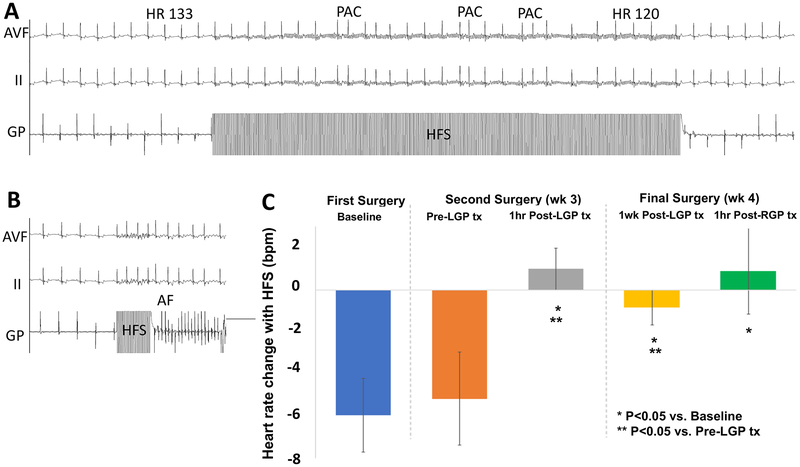

Subthreshold High frequency stimulation of GP:

Figure 3A illustrates transient HR slowing and induction of premature atrial complexes during HFS of GP. Figure 3B illustrates in the same animal, induction of AF during HFS of GP. Note that AF induction during GP HFS was not systemically quantified. HFS of GP decreased HR by 6±2bpm during first surgery (Figure 3C, baseline), and 5±2bpm during second surgery (Pre-LGP tx). Within 1 minute of nCaCl2 injection, HR increased (111±5 to 121±6bpm, p<0.01) in all GP. nCaCl2-treatment subsequently abolished the HR response to HFS of GP at 1 hour Post-LGP tx, 1 week Post-LGP tx, and 1 hour Post-RGP tx (p<0.05). In contrast, sham animals did not have a significant increase in HR at the time of GP injection (0.1±1.4bpm) as compared with nCaCl2 injection (p=0.03). HFS of sham-injected GP showed a transient loss of HR response at 1 hour (1.4±1.4bpm vs pre-injection −7±2.3bpm, p=0.03) but this was restored at 1 week (−4.3±2.4bpm, p=0.1 vs pre-injection).

Figure 3. High Frequency Subthreshold Stimulation (HFS) of GP.

(A) Example of HFS resulting in transient HR slowing from 133 to 122 bpm, and triggering PACs. (B) In the same animal, HFS of GP also triggered PAF. (C) Heart rate changes are abolished after treatment of GP with nCaCl2.

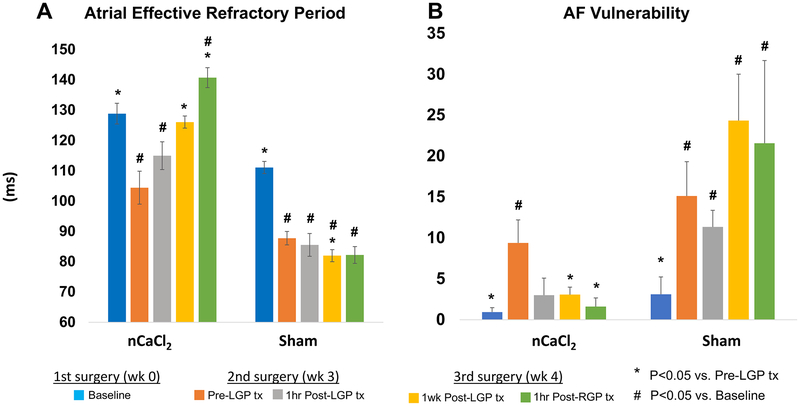

Effect of nCaCl2-treatment on atrial effective refractory period:

Figure 4A is a summary of mean AERP changes after treatment with nCaCl2 or vehicle control (sham). Mean AERP reflects average AERP of 3 LA regions. Supplemental Figure 1 details AERP in three LA regions. Table 1 summarizes all results. There was a significant decrease in mean AERP (p<0.0001) from first surgery (Baseline) to second surgery (Pre-LGP tx). This decrease was observed at all LA sites (Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 1). After nCaCl2-LGP treatment, mean AERP increased significantly at 1 week (p=0.0004). The increase in AERP was progressive, being significant in the PLA at 1 hour (1 hr Post-LGP tx), in the PLA and LAA at 1 week (1 wk Post-LGP tx) and in all sites at 1 hour after RGP treatment (1 hr Post-RGP tx). Furthermore, mean AERP at 1 hour after RGP treatment was greater than at baseline (p=0.015). In the sham group, AERP decreased in all sites between baseline and second surgery (Pre-LGP tx) (p=0.001). However, after sham treatment, mean AERP decreased further at 1 week Post-LGP tx (p=0.04 vs Pre-LGP tx) and remained decreased at all timepoints compared with baseline.

Figure 4: Effects of nCaCl2 on Atrial Effective Refractory Period (AERP) and Atrial Fibrillation Vulnerability (AFV).

Sequential changes in AERP and AFV with nCaCl2 or vehicle control (sham) treatment, from first surgery (baseline), to second surgery before (Pre-LGP tx) and 1 hr after LGP treatment (1hr Post-LGP tx), to final surgery (1wk Post-LGP tx) including the treatment of RGP (1hr Post-RGP tx). Mean AERP and AFV values represented the respective average of 3 LA regions.

Table 1. Changes in Atrial effective refractory period (AERP) after nCaCl2 vs sham treatment.

Sequence from first surgery (baseline), to second surgery before (Pre-LGP tx) and 1 hr after LGP treatment (1 hr Post-LGP tx), to final surgery (1wk Post-LGP tx) including the treatment of RGP (1 hr Post-RGP tx).

| Treatment | Area | Baseline | Pre-LGP tx vs. Baseline |

1hr Post-LGP tx vs. Baseline vs. Pre-LGP tx |

1wk Post-LGP tx vs. Baseline vs. Pre-LGP tx |

1hr Post-RGP tx vs. baseline vs. Pre-LGP tx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nCaCl2 | LAA | 125±6ms | 115±6ms p=0.02 |

118±9ms p=0.28 p=0.32 |

130±3ms p=0.32 p=0.028 |

135±9ms p=0.11 p=0.022 |

| PLA | 130±4ms | 97±11 ms p=0.009 |

118±8ms p=0.22 p=0.026 |

128±2ms, p=0.77 p=0.02 |

140±4ms, P=0.26 P=0.003 |

|

| ALA | 132±8ms | 102±11ms p=0.04 |

108±8ms p=0.05 p=0.7 |

120±4ms p=0.23 p=0.12 |

145±5ms p=0.65 p=0.012 |

|

| Mean | 129±3ms | 104±5ms p<0.0001 |

115±5ms P=0.02 P=0.06 |

126±2ms P=0.48 P=0.0004 |

143±4ms P=0.015 P=0.002 |

|

| Sham | LAA | 113±3ms | 87±3ms P=0.008 |

80±6ms P=0.007 p=0.5 |

77±3ms p=0.004 p=0.09 |

87±6ms P=0.03 p=0.9 |

| PLA | 107±3ms | 83±3ms P=0.009 |

96±3ms p=0.12 p=0.04 |

77±3ms p=0.01 p=0.13 |

80±1ms P=0.03 p=0.5 |

|

| ALA | 113±3ms | 93±3ms p=0.03 |

80±6ms P=0.03 P=0.16 |

83±3ms P=0.03 p=0.2 |

77±7ms P=0.01 P=0.18 |

|

| Mean | 111±4ms | 88±3ms p=0.001 |

86±6ms P=0.04 p=0.58 |

82±2ms P=0.01 p=0.04 |

81±3ms P=0.01 p=0.07 |

Suppression of POAF vulnerability:

Figure 4B shows vulnerability to AF (mean AFV) before and after treatment with nCaCl2 or sham, reflecting average AFV of three LA regions. Supplemental Figure 2 details AFV changes per LA region. Table 2 summarizes all AFV results. Mean AFV increased from first surgery (baseline) to second surgery (Pre-LGP tx) (p=0.008). This increase was apparent at all LA sites (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 2). After nCaCl2-LGP treatment, mean AFV decreased by 1 week post-LGP tx (p=0.04). However, this decrease was significant in the PLA (p=0.02) and LAA (p=0.03) but not in the ALA (p=0.07). Subsequent RGP-treatment further reduced mean AFV (p=0.02) and again, this was significant in the PLA (to 0, p=0.01) and LAA (to 0, p=0.02) but not in the ALA (p=0.06). In the sham group, mean AFV increased at second surgery (Pre-LGP tx) vs Baseline (p=0.003), and remained increased at all subsequent time-points (p=0.004, p=0.002, and p=0.02 respectively).

Table 2.

Changes in Atrial Fibrillation Vulnerability Scores (AFV) after nCaCl2 vs sham treatment.

| Treatment | Area | Baseline | Pre-LGP tx vs. Baseline |

1hr Post-LGP tx vs. Baseline vs. Pre-LGP tx |

1wk Post-LGP tx vs. Baseline vs. Pre-LGP tx |

1hr Post RGP tx vs. Baseline vs. Pre-LGP tx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nCaCl2 | LAA | 1.7±1.3 | 8.7±3.4 p=0.03 |

0 p=0.42 p=0.04 |

1.6±1 p=0.77 p=0.03 |

0 p=0.2 p=0.02 |

| PLA | 0.8±0.5 | 9±2.9 p=0.01 |

3±2.6 p=0.42 p=0.032 |

2.2±1.4 P=0.37 P=0.02 |

0 p=0.19 p=0.01 |

|

| ALA | 0.3±0.3 | 10.5±5.3 p=0.02 |

6±3.7 p=0.25 p=0.11 |

5.4±2.1 p=0.16 p=0.07 |

4.8±3.2 p=0.08 p=0.06 |

|

| Mean | 0.9±0.5 | 9.4±2.8 p=0.008 |

3±2.1 p=0.15 p=0.08 |

3.1±0.9 P=0.16 P=0.04 |

2.4±1.6 P=0.55 P=0.02 |

|

| Sham | LAA | 5±5 | 14.7±2 p=0.05 |

12±5 p=0.09 p=0.8 |

21.3±10.3 p=0.07 p=0.62 |

17.3±8 p=0.11 p=0.54 |

| PLA | 3.3±0.7 | 20.7±8.2 P=0.02 |

9±4.2 p=0.06 p=0.15 |

25.7±5 P=0.02 p=0.77 |

23±12.7 p=0.04 p=0.8 |

|

| ALA | 1±1 | 10±4.4 p=0.007 |

13±3.8 P=0.02 p=0.45 |

26±3.5 p=0.004 p=0.03 |

24.3±9.8 p=0.04 p=0.1 |

|

| Mean | 3.1±2. 1 | 15.1±4.2 p=0.003 |

11.3±2 P=0.004 p=0.22 |

24.3±5.7 P=0.002 P=0.05 |

21.6±10.1 p=0.02 p=0.12 |

Evidence of autonomic modulation:

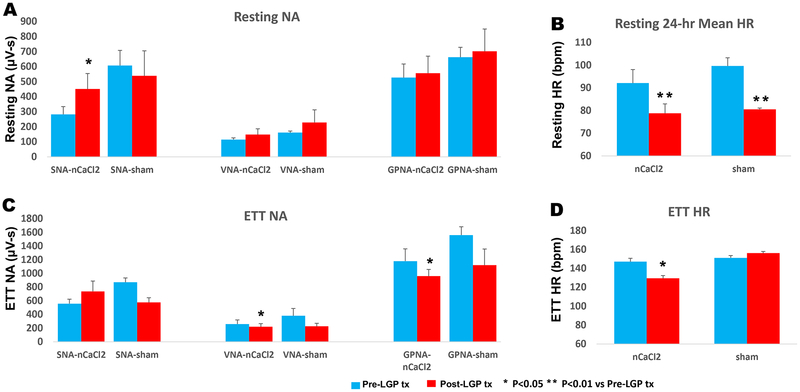

Figure 5 summarizes the effects of LGP treatment with nCaCl2 vs sham on NA and HR during 24-hr of rest (5A and B) and 9-min of ETT (5C and D). The data obtained at two timepoints after 1st surgery (Pre-LGP tx) and after 2nd surgery (Post-LGP tx), represent NA in the ambulatory postoperative state without LGP treatment (after first surgery) and with LGP treatment (after second surgery). After nCaCl2-LGP treatment (Post-LGP tx), resting SNA increased (p<0.02) whereas resting VNA (p=0.18) or GPNA (p=0.16) remained unchanged. Despite increased resting SNA (Fig. 5A), resting HR decreased (p<0.01) (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 3A), with loss of HR-SNA correlation (R=0.09). Heart rate variability (SDNN) at rest was unchanged (0.28±0.037 to 0.32±0.029, p=0.19). During ETT (Fig. 5C), VNA (p<0.05) and GPNA (p<0.02) responses to exercise decreased whereas SNA response was not significantly different (p=0.09). However, HR response during exercise (Fig. 5D, Supplementary Fig. 3B) decreased (p<0.01) and was only modestly correlated with exercise SNA (R=0.62).

Figure 5: Effects of Left GP Treatment with nCaCl2 on Autonomic Nerve Activity and Heart Rate.

Average NA (A) and HR (B) during 24-hours of rest and during 9 minutes of exercise treadmill testing (ETT) (C and D) before (Pre-LGP tx) and after (Post-LGP tx) nCaCl2 treatment to left GP. The nCaCl2 group was compared with vehicle control (sham) group. * P<0.05 ** P<0.01 vs Pre-LGP tx.

Sham treatment (Fig. 5A) resulted in no significant changes to resting SNA (P=0.40), resting VNA (P=0.25) and GPNA (P=0.43). Although resting HR (Fig. 5B) decreased (p<0.03), a change similar to after nCaCl2 treatment, SDNN increased (0.26±0.04 to 0.39±0.06, p<0.006) and resting HR remained tightly correlated with SNA (R=0.99), in contrast to the nCaCl2 group. During ETT (Fig. 5C and D), SNA (P=0.055), VNA (P=0.082), GPNA (P=0.13) and HR response (P=0.25) were not significantly different after sham treatment. However, exercise HR and SNA remained correlated (R=0.95).

Effects of nCaCl2 on Cardiac Function:

There were no acute changes in LVEF after nCaCl2 treatment (58±3% vs 61±2% p=0.21).

Histology:

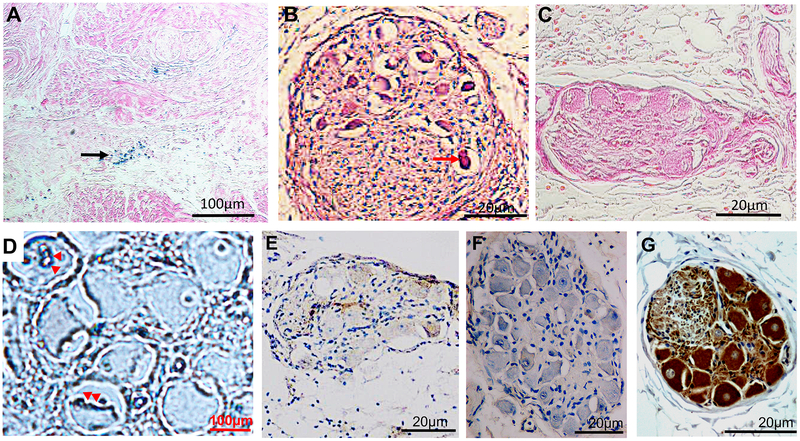

Prussian blue reaction revealed aggregated magnetite-containing nanoparticles localized to the epicardial fat layer containing GP (black arrows, Figure 6A) but not in the deeper atrial myocardium. All nCaCl2-treated GP had evidence of neural somas (6B) exhibiting condensed cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei (red arrow), consistent with apoptosis8 and confirmed by the positive TUNEL staining (red arrowheads, 6D). Sham-treated GP soma (6C) did not demonstrate cellular apoptosis. Figure 6E and F are stained with Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT) (6E) and Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) (6F) respectively, demonstrating negative immunoreactivity in all nCaC2-treated GP soma. In contrast, 93±7% of somas in sham-treated GP soma were immunoreactive to ChAT (6G) (p=0.006). Quantitative analyses of immunoreactivity of neural bundle are described in the data supplement and supplementary figure 4.

Figure 6. Histological Analyses.

(A): Prussian Blue reaction of LGP demonstrating blue coloration of aggregated magnetite-containing nanoparticles (black arrow). (B) Cellular apoptosis characterized by pyknotic nuclei with condensed cytoplasm.(C) H+E stain of GP in sham group showing normal soma in GP. (D): Tunel staining (red arrows) within nuclei within apoptotic neuron. Negative immunoreactivity of somas to Choline Acetyl Transferase (E) and Tyrosine Hydroxylase (F) 1-week after nCaCl2- treatment, compared ChAT-positive somas in sham-treated GP (G). Further immunostaining analyses in data supplement.

Discussion

Epicardial injection of a nanoformulation (nCaCl2) comprised of PLGA polymer encapsulant, carrying a payload of 0.5mM CaCl2 with trace L-glutamate, into LA ganglionated plexi (GP), reversed the postoperative reduction in AERP and suppressed AF vulnerability in a canine model of POAF. The effects were evident by 1 hr due to acute GP suppression by PLGA burst release calcium and greater at 1wk, consistent with GP neuroapoptosis, but absent in vehicle control (sham) animals. Treatment with nCaCl2 suppressed GP function and moderated heart rate response to increased SNA, consistent with autonomic modulation. The atrial electrophysiologic effect of nCaCl2 is most apparent closest to targeted GP and cumulative with additional treatment of RGP to LGP. There was no nanoparticle infiltration into atrial myocardium. We conclude that targeted GP suppression by nCaCl2 suppresses POAF by reversing postoperative AERP reduction and protects the heart against postoperative sympathetic surge.

Neuronal excitotoxicity:

The nCaCl2-induced GP excitotoxicity stems from its ability to increase extracellular calcium concentration, increase the transmembrane calcium gradient, promoting calcium internalization and neuroapoptosis.6 L-glutamate facilitates calcium internalization by activating neuronal NMDA receptors.6 Increased intracellular calcium activates an enzymatic (e.g. calpain) cascade which eventually causes neuroapoptosis.6 This localized ganglion cell death, could be characterized as a targeted chemical ablation of GP. Histological data showing preferential effect of nCaCl2 on neural somas versus axonal bundles (data supplement, supplementary figure 4) underscore the concept of targeted therapy.

Advantages and safety of targeted nanomedicine therapy:

Encapsulation of CaCl2 within nanoparticles has several therapeutic advantages in targeted GP modulation.9 First, PLGA has a burst release within minutes followed by sustained release of payload for days to weeks,13,18 prolonging GP exposure to CaCl2. In vitro studies7 demonstrated that 30% of the PLGA payload is released within 30 minutes, and another 40% by 20 days. The increased HR observed within minutes of nCaCl2 is consistent with the acute excitatory phase of calcium-glutamate excitotoxicity. Second, nanoparticles concentrate and stabilize the payload at the target site by virtue of their small diameter (230±101 nm) creating a large surface area to volume ratio which facilitates sufficient neuronal calcium internalization.

Autonomic modulation and POAF suppression:

We made several key observations. First, nCaCl2-LGP treatment is sufficient to reverse the postoperative reduction in AERP and increase in AFV following cardiac surgery. Second, the anti-arrhythmic action of nCaCl2 is evident within 1 hour closest to the GP (in the PLA), becoming more widespread and pronounced at 1 week, consistent with the time course of an apoptotic process.6 Third, sham control animals had transient loss of HR response to GP HFS, and transient (non-significant) decrease in AFV at 1 hour (Fig. 4B), possibly due to mechanical perturbation of GP by the 1ml aqueous injectate. Fourth, nCaCl2-LGP treatment were magnified by nCaCl2-RGP treatment indicating greater AF suppression when more GP were targeted, similar to prior RF studies10,11 favoring a more extensive anatomic approach to GP ablation. Fifth, nCaCl2-GP treatment modulates the autonomic balance within the CANS, evidenced by: (a) reversed AERP remodeling, (b) moderation of HR response to increased SNA, and (c) reduced exercise GPNA after nCaCl2. Following LGP treatment, HR was reduced in nCaCl2-treated animals despite increased SNA. On the other hand, HR was also reduced in sham-control animals, but was concordant with SNA. While nCaCl2-LGP treatment resulted in some degree of sympathetic blockade, circadian HR variability and HR response to exercise remain preserved (Supplemental Figure 3), indicating cardiac autonomic modulation not denervation. These autonomic changes were nevertheless significantly different from the increased heart rate and reduced heart rate variability reported after RF ablation.10,11 The discrepancy reflects two different modes of GP modulation (calcium vs RF), treatment of the left subset of LA GP versus all LA GP or RA GP in other studies11,10 or comparisons with different denominators (i.e. between two post-thoracotomy states vs between pre- and post-RF ablation states).10,11 Because nCaCl2-induced neuroapoptosis is a phased process beginning with cellular excitation and culminating in cell death,6,8 we hypothesize that increased SNA is a result of activation of cardio-cardiac reflexes12 elicited by excitotoxicity of GP soma. In contrast, RF energy unselectively destroys all neural and myocardial tissue. Any reflex changes triggered might conceivably be attenuated because of more extensive destruction of the components of the reflex limb.

Preferential effect of nCaCl2 on GP soma.

Immunostaining demonstrated complete loss of immunoreactivity in GP somas but only partial loss of immunoreactivity in neural bundles (data supplement, supplementary figure 4). These data indicate a preferential effect of nCaCl2 on local soma rather than trafficking neurons, underscoring the specificity of GP modulation compared with RF ablation. A potential mechanism for this specificity is the increased role of extra-synaptic (versus synaptic) NMDA receptors in neuro-excitotoxicity,13 and their preferential localization in neural soma and non-synaptic dendrites versus axons.13 The targeted nature of nCaCl2 provides a further explanation for the different autonomic reflexes elicited after nCaCl2 vs RF treatment of GP.

Comparisons with Botulinum Toxin

Botulinum toxin (botox) is a cholinergic neuron blocker that binds to presynaptic cholinergic neurons and prevents acetylcholine release for 3–6 months. Yet, botox injection into ganglia suppresses AF following CABG well beyond that period.14,15 The mechanism(s) are unclear. Data from a canine model of pacing-induced AF suggests that even transient cholinergic neuron suppression may cause a reset of the CANS16 sufficient to render longer term protection against AF. Restani et al17 discovered extensive retrograde axonal transport of botox from the neuromuscular junction of primary motor neuron cultures. We speculate that retrograde axonal transport of botox from GP to the CANS network could explain the more sustained resetting of the CANS. In contrast, due to evident neuroapoptosis in our study and the limited regenerative capacity of the CANS, we suspect that nCaCl2 can confer persistent neuromodulation and AF suppression. These unresolved questions merit further investigation.

Limitations

We were unable to treat all 4 LA GP simultaneously due to the limitations of a unilateral left thoracotomy approach necessitated by survival surgeries. Nevertheless, our sequential approach tested the relative contribution of LGP then RGP to AF vulnerability. We chose a 1 week duration post-treatment coinciding with the time course of apoptosis6 and peak incidence of POAF.18 However, a chronic study would be needed to substantiate the presence of chronic neurosuppression and reveal any long term side effects. Our survival surgeries necessitated the use of isoflurane anesthesia, which suppresses sympathetic nerve activity in a dose-dependent manner,19 and could have diminished GP responses to HFS.2 Non-invasive manual BP readings did not demonstrate any off-target effects of nCaCl2 on BP. Finally, multi-site GP recordings might be more informative on the state of the intrinsic CANS function.

Conclusion

Epicardial Injection of nanoformulated calcium chloride into LA ganglionated plexi, suppresses GP function and POAF. The mechanism is burst-then-slow release of calcium from nanoparticles that results in calcium-induced acute neurotoxicity and neuroapoptosis. This targeted GP treatment exerts an anticholinergic modulation on the atrial electrophysiology (increasing AERP) and provides cardioprotection against the postoperative sympathetic surge, sufficient to reverse the atrial electrophysiologic remodeling triggered by cardiac surgery and suppress AF. This treatment is easily administered without observed side effects, atrial damage or effects on ventricular function. We conclude that nanoformulated calcium administered during open heart surgery is a promising therapeutic option to prevent POAF.

Clinical Translation

POAF is one of the most prevalent complications of cardiac surgery responsible for prolonged hospital stays and additional costs of US$2 billion in the US alone.20 Although POAF peaks during the first postoperative week, it is an independent predictor of late AF.21 Nanoformulated calcium specifically targets the intrinsic CANS, a major pathophysiologic driver for POAF. Delivered by direct epicardial injection into GP, the nanoparticles release their calcium in a burst and timed-release manner, increases local extracellular calcium concentration in the GP and causes neuroapoptosis. This targeted therapy modulates intrinsic CANS function by reversing atrial electrophysiologic remodeling caused by postoperative injury and repair, moderates cardiac response to sympathetic surge and suppresses POAF. Long term studies will be needed to substantiate the durability of its anti-arrhythmic action.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Martha Joslyn MS, Li Wang PhD, Anindita Das PhD, Robert Lippman, MD, Austin Minuto, and Andrew Worley for their assistance.

Funding Sources

This study is supported by Virginia Commonwealth Commercialization Fund (CRCF: MF16-041-LS), American Heart Association (16SDG3128001), and National Institutes of Health (1R56HL133182-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts: Dr Dormer is a co-founder of Nanomed Targeting Systems (NTS) Inc.

References

- 1.Tan AY, Zhou S, Ogawa M, Song J, Chu M, Li H, Fishbein MC, Lin S-F, Chen LS, Chen P-S: Neural mechanisms of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia in ambulatory canines. Circulation 2008; 118:916–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherlag BJ, Yamanashi W, Patel U, Lazzara R, Jackman WM: Autonomically induced conversion of pulmonary vein focal firing into atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:1878–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amar D, Zhang H, Miodownik S, Kadish AH: Competing autonomic mechanisms precede the onset of postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42:1262–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauza DH, Skripka V, Pauziene N, Stropus R: Morphology, distribution, and variability of the epicardiac neural ganglionated subplexuses in the human heart. Anat Rec 2000; 259:353–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan AY, Li H, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, et al. : Autonomic innervation and segmental muscular disconnections at the human pulmonary vein-atrial junction: implications for catheter ablation of atrial-pulmonary vein junction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P: Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003; 4:552–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon JU, Ravikumar P, Pise A, et al. : Polymeric nanoparticles for pulmonary protein and DNA delivery. Acta Biomaterialia 2014; 10:2643–2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmore S: Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol Sixth Edition. 2007; 35:495–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu L, Scherlag BJ, Dormer K, Nguyen KT, Pope C, Fung K-M, Po SS: Autonomic denervation with magnetic nanoparticles. Circulation 2010; 122:2653–2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calò L, Rebecchi M, Sciarra L, De Luca L, Fagagnini A, Zuccaro LM, Pitrone P, Dottori S, Porfirio M, de Ruvo E, Lioy E: Catheter ablation of right atrial ganglionated plexi in patients with vagal paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012; 5:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pappone C, Santinelli V, Manguso F, et al. : Pulmonary vein denervation enhances long-term benefit after circumferential ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2004; 109:327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coote JH: Spinal and supraspinal reflex pathways of cardio-cardiac sympathetic reflexes. Neurosci Lett 1984; 46:243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardingham GE, Bading H: Synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010; 11:682–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pokushalov E, Kozlov B, Romanov A, et al. : Long-Term Suppression of Atrial Fibrillation by Botulinum Toxin Injection Into Epicardial Fat Pads in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: One-Year Follow-Up of a Randomized Pilot Study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015; 8:1334–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanov A, Pokushalov E, Ponomarev D, et al. : Three-year Outcomes After Botulinum Toxin Injections Into Epicardial Fat Pads for Atrial Fibrillation Prevention in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Heart Rhythm Boston, 2018, pp. B–LBCT02. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo L-W, Chang H-Y, Scherlag BJ, Lin Y-J, Chou Y-H, Lin W-L, Chen S-A, Po SS: Temporary Suppression of Cardiac Ganglionated Plexi Leads to Long-Term Suppression of Atrial Fibrillation: Evidence of Early Autonomic Intervention to Break the Vicious Cycle of “AF Begets AF”. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5:e003309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Restani L, Giribaldi F, Manich M, et al. : Botulinum neurotoxins A and E undergo retrograde axonal transport in primary motor neurons. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1003087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aranki SF, Shaw DP, Adams DH, Rizzo RJ, Couper GS, VanderVliet M, Collins JJ, Cohn LH, Burstin HR: Predictors of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery surgery. Current trends and impact on hospital resources. Circulation 1996; 94:390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seagard JL, Hopp FA, Bosnjak ZJ, Osborn JL, Kampine JP: Sympathetic efferent nerve activity in conscious and isoflurane-anesthetized dogs. Anesthesiology 1984; 61:266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaPar DJ, Speir AM, Crosby IK, Fonner E, Brown M, Rich JB, Quader M, Kern JA, Kron IL, Ailawadi G, Investigators for the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative: Postoperative atrial fibrillation significantly increases mortality, hospital readmission, and hospital costs. Ann Thorac Surg Elsevier, 2014; 98:527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melduni RM, Schaff HV, Bailey KR, Cha SS, Ammash NM, Seward JB, Gersh BJ: Implications of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery on long-term prognosis: a community-based study. Am Heart J 2015; 170:659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.