Age-dependent downregulation of JMJ16, a specific H3K4 demethylase, is required for epigenetic reprograming of senescence-associated gene expression during leaf senescence.

Abstract

Leaf senescence is governed by a complex regulatory network involving the dynamic reprogramming of gene expression. Age-dependent induction of senescence-associated genes (SAGs) is associated with increased levels of trimethylation of histone H3 at Lys4 (H3K4me3), but the regulatory mechanism remains elusive. Here, we found that JMJ16, an Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) JmjC-domain containing protein, is a specific H3K4 demethylase that negatively regulates leaf senescence through its enzymatic activity. Genome-wide analysis revealed a widespread coordinated upregulation of gene expression and hypermethylation of H3K4me3 at JMJ16 binding genes associated with leaf senescence in the loss-of-function jmj16 mutant as compared with the wild type. Genetic analysis indicated that JMJ16 negatively regulates leaf senescence, at least partly through repressing the expression of positive regulators of leaf senescence, WRKY53 and SAG201. JMJ16 associates with WRKY53 and SAG201 and represses their precocious expression in mature leaves by reducing H3K4me3 levels at these loci. The protein abundance of JMJ16 gradually decreases during aging, which is correlated with increased H3K4me3 levels at WRKY53 and SAG201, suggesting that the age-dependent downregulation of JMJ16 is required for the precise transcriptional activation of SAGs during leaf senescence. Thus, JMJ16 is an important regulator of leaf senescence that demethylates H3K4 at SAGs in an age-dependent manner.

INTRODUCTION

Leaf senescence is the highly ordered final stage of leaf development. This process is characterized by the degradation of chlorophylls, nucleic acids, lipids, proteins, and other macromolecules, and subsequently by programmed cell death and changes in leaf color (Lim et al., 2007). The nutrients released during leaf senescence are recycled to reproductive organs or actively growing young tissues (Woo et al., 2013). Genome-wide transcriptional analyses revealed that dramatic changes in the expression of thousands of senescence-associated genes (SAGs) occur during leaf senescence; however, it is unclear how the transcriptional reprogramming of these genes is regulated in a time-dependent manner (Li et al., 2012, 2014).

Various transcription factors, including NO APICAL MERISTEM, ATAF1/2, and CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON2 (NAC), and WRKY, MYELOBLASTOSIS, Cysteine2Histidine2 zinc finger, BASIC LEUCINE ZIPPER, and APETALA2/ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING PROTEIN family proteins, play pivotal roles in the transcriptional regulation of SAGs during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Balazadeh et al., 2008). However, the expression of the genes encoding these transcription factors is also regulated during leaf senescence, indicating that additional mechanisms determine the onset of leaf senescence (Woo et al., 2013). For example, ORESARA1 (also known as ANAC092), a NAC transcription factor, positively regulates leaf senescence (Kim et al., 2009). ORESARA1 expression increases during leaf aging, and this increase is associated with an age-dependent, ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE PROTEIN2-mediated decline in transcription of the microRNA miR164 (Kim et al., 2009). Furthermore, WRKY53, a WRKY transcription factor, promotes leaf senescence by regulating the expression of its target genes, including WRKY6, WRKY22, and ORE9 (Woo et al., 2001; Robatzek and Somssich, 2002; Miao et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2011). WRKY53 expression increases at the onset of senescence but is maintained at low levels before senescence (Ay et al., 2009). The age-dependent induction of WRKY53 transcription is regulated by WHIRLY1, which directly binds to the promoter region of WRKY53 and represses its expression (Miao et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2018). During leaf senescence, WHIRLY1 gradually dissociates from the WRKY53 promoter, and WRKY53 transcription is subsequently induced (Miao et al., 2013). In addition, the induction of WRKY53 expression during senescence is associated with increased trimethylation of histone H3 at Lys4 (H3K4me3, a mark of actively transcribed chromatin) levels at the 5′ end and coding region of WRKY53 (Ay et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). Genome-wide analysis of changes in histone methylation during senescence revealed that a large proportion of upregulated SAGs are also associated with increased H3K4me3 levels (Brusslan et al., 2012). However, how the H3K4me3 levels at WRKY53 and other SAGs are regulated remains largely unknown.

Overexpression of SUPPRESSION(VAR)3-9 homolog2 (SUVH2), which is involved in RNA-directed DNA methylation, represses the expression of WRKY53 and other SAGs by promoting ectopic H3K27me2/3 modifications (Ay et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2014; Jing et al., 2016). However, the repression of WRKY53 expression before senescence is not associated with silencing chromatin marks (such as H3K9me2 and H3K27me3) in the wild type, suggesting that increased H3K4me3 levels, rather than decreased levels of silencing chromatin marks, underlie WRKY53 activation in the wild type (Ay et al., 2009). H3K4me3 methyltransferases and/or demethylases might regulate the age-dependent dynamic regulation of H3K4me3 levels at WRKY53 and other SAGs, but this remains to be elucidated (Yolcu et al., 2018). The Arabidopsis genome contains six genes encoding homologs of Lys demethylase5 (KDM5), including JMJ14, JMJ15, JMJ16, JMJ17, JMJ18, and JMJ19 (Lu et al., 2008). Among these, JMJ14, JMJ15, and JMJ18 have been shown to function as H3K4 demethylases that regulate the transition to flowering (Lu et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2012a, 2012b). However, the enzyme activities and functions of the other Arabidopsis KDM5 group members have not been characterized.

In this study, we demonstrated that Arabidopsis JMJ16 is a specific H3K4 demethylase that negatively regulates age-dependent leaf senescence through its demethylase activity. Genome-wide analyses demonstrated that a loss-of-function mutation in JMJ16 increases H3K4me3 levels and induces the expression of numerous SAGs. Genetic and molecular analyses indicated that precociously increased H3K4me3 levels in jmj16 mutants at WRKY53 and SAG201, two known positive regulators of leaf senescence (Miao et al., 2004; Hou et al., 2013), are responsible for the early-senescence (ES) phenotype. Finally, we detected substantially reduced levels of JMJ16 during the late stages of leaf development, which may be responsible for the transcriptional activation of these SAGs. Together, these findings uncover a mechanism by which an H3K4 demethylase regulates the transcriptional reprogramming of SAGs during senescence by modulating H3K4me3 levels in an age-dependent manner.

RESULTS

JMJ16 Represses Leaf Senescence

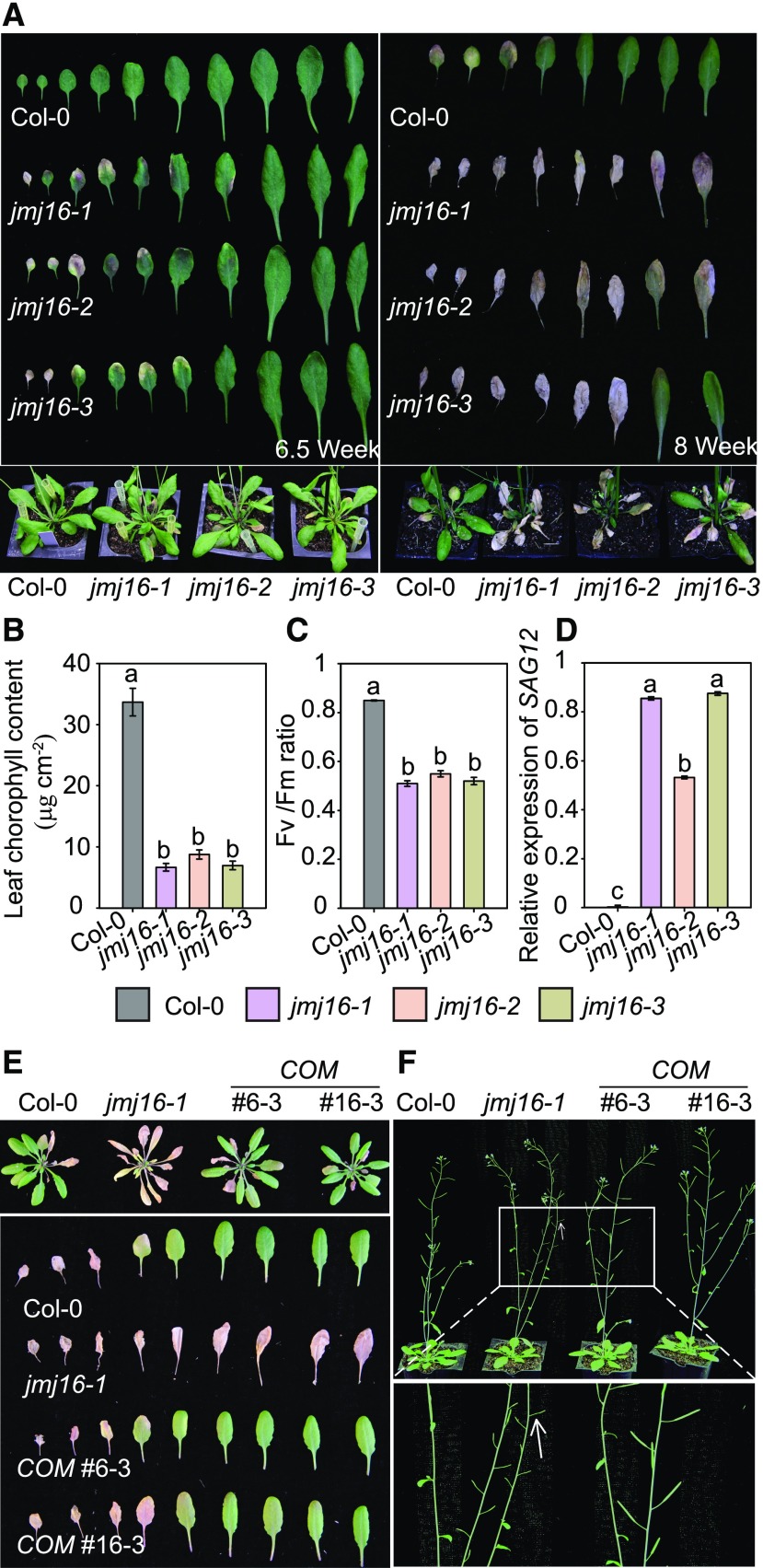

JMJ16 (also known as PKDM7D) is a member of the KDM5 group of proteins, which mediate demethylation of mono-, di-, and trimethylated H3K4 (H3K4me1/2/3) in humans (Lu et al., 2008). We found that jmj16 loss-of-function mutants (Supplemental Figures 1A and 1B) accumulated higher levels of reactive oxygen species than wild type (Supplemental Figures 1D and 1E). Because increased reactive oxygen species levels and dynamic changes in H3K4 methylation homeostasis are often associated with leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Ay et al., 2009; Brusslan et al., 2012;Woo et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2018), we speculated that JMJ16 might regulate leaf senescence. Consistent with our speculation, we observed an early leaf senescence phenotype in 6.5-week–old jmj16 T-DNA insertion mutant lines grown under long-day conditions, i.e. jmj16-1, -2, and -3, but not in the wild type (Figure 1A, left). The early leaf senescence phenotype of the jmj16 mutants was even more pronounced in 8-week–old plants grown under long days (Figure 1A, right). On the other hand, mutations in other KDM5 family genes, including JMJ14, JMJ17, and JMJ18, did not lead to altered leaf senescence (Supplemental Figure 2). Moreover, the chlorophyll content and photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm), two physiological parameters that decrease during leaf senescence (Oh et al., 1996), were lower in the jmj16 mutants as compared with the wild type (Figures 1B and 1C). In addition, the expression of SAG12 was upregulated in leaves 5 and 6 of 6.5-week–old jmj16 plants, but not in the wild type (Figure 1D). Genetic transformation of jmj16-1 with JMJ16 genomic DNA completely rescued its ES phenotype (Figure 1E; Supplemental Figures 3A, 3C, and 3D). These results indicate that JMJ16 represses leaf senescence. In addition to the ES phenotype, the jmj16 mutants exhibited silique abortion, which was also rescued by the expression of JMJ16 (Figure 1F; Supplemental Figure 3B). We also noticed that the jmj16 mutants exhibited slightly earlier flowering than the wild type (Supplemental Figure 1F). Although the jmj14 mutation causes early flowering (Lu et al., 2010), it did not affect leaf senescence (Supplemental Figure 2A). Thus, it is unlikely that the slightly accelerated transition to flowering causes the strikingly early leaf senescence of jmj16.

Figure 1.

Leaf Senescence Phenotypes of jmj16 T-DNA Insertion Mutants and Complementation Transgenic Plants.

(A) Leaf senescence phenotypes. Plants were grown under long-day conditions for 6.5 weeks (left) or 8 weeks (right). DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

(B) to (D) Chlorophyll content (B), Fv/Fm ratio (C), and expression level of SAG12 (D) in leaves 5 and 6 of 6.5-week–old plants. Relative expression was normalized to that of eIF4a. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among genotypes based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P < 0.0001). DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; WT = wild type.

(E) Leaf senescence phenotypes of 7-week–old wild-type, jmj16, and complementation plants.

(F) The jmj16-1 mutant exhibits an aborted silique phenotype, which is rescued by the expression of JMJ16. Six-week–old plants were photographed; a magnified view of the area in the rectangle is shown at the bottom. Arrow indicates aborted silique. COM indicates the expression of JMJ16 driven by its own promoter in jmj16-1.

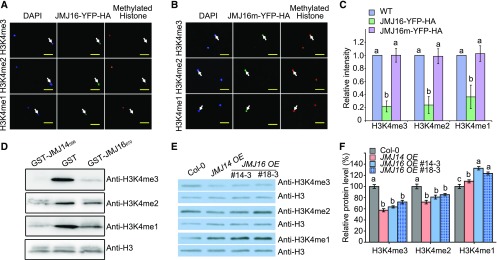

JMJ16 Specifically Demethylates H3K4 Methylation

To examine the histone demethylase activity of JMJ16, we transiently expressed JMJ16-YFP (Yellow Fluorescent Protein)-HA (Hemagglutinin) in wild tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaves and compared the histone modification levels in transfected and nontransfected cells, as described in Lu et al. (2010). In JMJ16-YFP-HA-expressing cells, H3K4me1/2/3 signals were substantially reduced (Figures 2A and 2C), whereas mono-, di-, or trimethylation levels at H3K9, H3K27, and H3K36 were not affected (Supplemental Figure 4A). Transient expression of JMJ16m-YFP-HA, in which His-381 and Glu-383 (two conserved iron binding amino acids) of JMJ16 were replaced with Ala, abolished the H3K4 demethylase activity, indicating that the conserved iron binding amino acids are critical for the H3K4 demethylase activity of JMJ16 (Figures 2B and 2C).

Figure 2.

JMJ16 is an H3K4 Demethylase.

(A) JMJ16-YFP-HA exhibits H3K4me1/2/3 demethylase activity in N. benthamiana leaves.

(B) Mutations in conserved Fe (II) binding amino acids (JMJ16m-YFP-HA) abolish its H3K4me1/2/3 demethylase activity in N. benthamiana leaves. In (A) and (B), JMJ16-YFP-HA and JMJ16m-YFP-HA expression in N. benthamiana nuclei (arrows) was visualized by monitoring YFP fluorescence (green, middle). The histone methylation status was analyzed by immunostaining with specific histone methylation antibodies (red, right). The location of nuclei was visualized using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (blue, left). Scale bars = 5 μm.

(C) Statistical analysis of the levels of fluorescent signals in (A) and (B). At least 25 pairs of JMJ16-YFP-HA- or JMJ16m-YFP-HA-expressing versus nonexpressing nuclei in the same field of view were analyzed. Error bars = ±SD. Different letters indicate significant differences based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P < 0.01).

(D) GST-JMJ16670 exhibits H3K4me1/2/3 demethylase activity in vitro. E. coli-expressed and affinity-purified GST-JMJ16670 was incubated with calf thymus histone, and the H3K4 methylation status was determined using methylation-specific antibodies. GST-JMJ14596 was used as a positive control and anti-H3 was used as a loading control.

(E) Global H3K4 methylation status of 10-d–old plants. JMJ14 OE and JMJ16 OE indicate the expression of JMJ14-YFP-HA and JMJ16-YFP-HA driven by the 35S promoter in Col-0, respectively. Methylation-specific antibodies were used to determine the global H3K4 methylation status. Anti-H3 was used as a loading control.

(F) Quantification analysis of (E). Immunoblots of three biological replicates were quantified; for each replicate, immunoblots were performed using freshly prepared protein extracts from Col-0, JMJ14-OE, and JMJ16 OE (#14-3 and #18-3). Error bars = ±sd. Different letters indicate significant differences among genotypes based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P < 0.05).

We then measured the H3K4 demethylase activity of JMJ16 in vitro as described in Yang et al. (2010). Similar to GST-JMJ14596 (Yang et al., 2010), affinity-purified recombinant protein GST-JMJ16670 (a 670-amino acid fragment of JMJ16 containing the JmjN, JmjC, and C5HC2 zinc finger domains) exhibited demethylation activity for mono-, di-, and trimethylated H3K4, but not for H3K9, H3K27 or H3K36, in vitro (Figure 2D; Supplemental Figure 4B). To confirm that JMJ16 has H3K4 demethylase activity in Arabidopsis, we generated transgenic Col-0 plants overexpressing JMJ16-YFP-HA (referred to as JMJ16 OE; Supplemental Figure 5), and examined the global mono-, di-, and trimethylation levels at H3K4. Overexpression of JMJ16-YFP-HA caused a global decrease in di- and trimethylation but an increase in monomethylation levels at H3K4, which is similar to what was observed for JMJ14-YFP-HA overexpression (Figures 2E and 2F). The global hypermethylation of H3K4me1 in JMJ16-YFP-HA overexpression plants might have occurred because the expression level of JMJ16 was not sufficient to catalyze the formation of enriched monomethylated H3K4 due to elevated demethylation of H3K4me2/3 in these plants. Taken together, these results indicate that JMJ16 is an H3K4-specific demethylase in Arabidopsis.

JMJ16 Negatively Regulates the Transcription and H3K4me3 Levels of Its Target Genes

Because JMJ16 is an H3K4me3 demethylase (Figure 2) and H3K4me3 is associated with active gene transcription (Zhang et al., 2009), we wanted to evaluate the direct effect of depletion of JMJ16 on the transcription of its target genes. To identify JMJ16-regulated genes at the genome-wide scale, we sequenced RNA from leaves 5 and 6 of 5-week–old wild type and jmj16-1 plants (Supplemental Data Set 1). At this stage, the leaves were in the mature stage and fully expanded and exhibited no visible yellowing in either the wild type or jmj16-1 mutant. A total of 10.6 million (65.3%) and 13.8 million (73.8%) clean reads were uniquely aligned to the Arabidopsis reference genome, which were mapped to 15,988 and 15,842 genes in the wild type and jmj16-1, respectively (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million > 1). Among these, 3,355 genes were upregulated (fold change > 1.5) and 2,594 genes were downregulated (fold change > 1.5) in jmj16-1 compared with the wild type (Supplemental Data Set 1).

To investigate whether these upregulated genes in jmj16-1 are directly associated targets of JMJ16, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) to capture genome-wide direct binding targets of JMJ16. A construct containing JMJ16-HA driven by the JMJ16 promoter was transformed into jmj16-1 (Supplemental Figures 6A to 6C). The expression of JMJ16-HA rescued the ES phenotype of jmj16-1, indicating that the HA fusion proteins were functional (Figure 3A). We performed ChIP-seq with anti-HA antibody in the leaves of jmj16-1 (as a negative control) and JMJ16-HA transgenic plants of the same stage as those used in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and identified 1,111 upregulated genes with significantly enriched binding (fold change > 2) in jmj16-1 harboring JMJ16-HA (Figure 4A; Supplemental Data Set 2). These results indicate that highly upregulated genes in jmj16-1 are direct targets of JMJ16.

Figure 3.

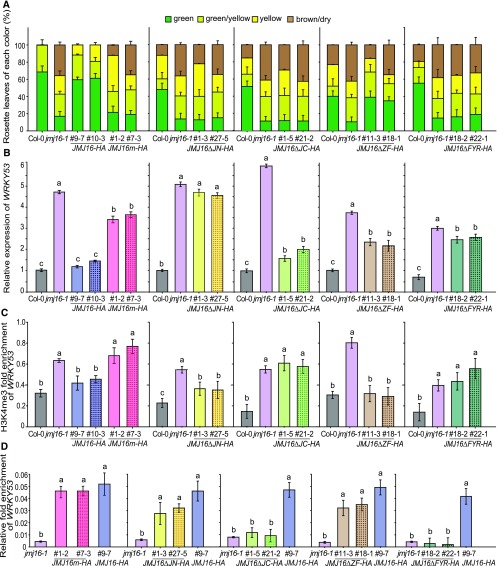

The Demethylase Activity and JmjN, JmjC, and FYR-rich Domains of JMJ16 Are Required for the Regulation of Leaf Senescence.

(A) Quantification of the leaf senescence phenotypes of 7-week–old plants grown under long-day conditions, as mentioned in Supplemental Figure 2. Error bars = ±se.

(B) RT-qPCR analysis of WRKY53 expression levels. eIF4a was used as an internal control.

(C) ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K4me3 methylation status at the WRKY53 locus. Anti-H3 and actin were used as internal references for ChIP-qPCR.

(D) ChIP-qPCR analysis of the association of JMJ16-HA and its mutant proteins with the WRKY53 locus. A specific primer corresponding to the WRKY53 R1 region (indicated in Figure 4) was used in the ChIP-qPCR analysis. Actin was used as an internal control.

Different letters indicate significant differences among genotypes based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P < 0.0001).

Leaves 5 and 6 of 5-week–old long-day-grown plants were used for RT-qPCR and ChIP-qPCR analyses. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3).

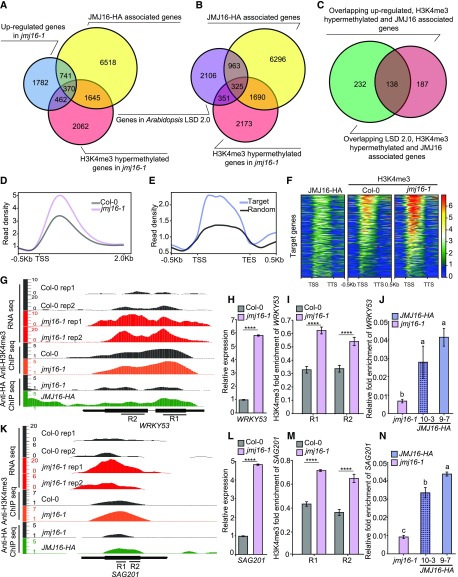

Figure 4.

The Transcription and H3K4me3 Methylation Levels of Many SAGs Are Upregulated in jmj16-1.

(A) Venn diagram showing the overlap among genes that are transcriptionally upregulated in jmj16-1, H3K4me3 hypermethylated genes in jmj16-1, and JMJ16-HA–associated genes.

(B) Venn diagram showing the overlap among SAGs from Arabidopsis LSD 2.0, H3K4me3 hypermethylated genes in jmj16-1 and JMJ16-HA-associated genes.

(C) Venn diagram showing the significant overlap (Fisher’s exact test, P value = 9.64e-178) between the 370 targets from (A) and the 325 targets from (B).

(D) Normalized read density of H3K4me3 ChIP-seq signals at the TSS of JMJ16 target genes in Col-0 and jmj16-1.

(E) Normalized read density of JMJ16-HA ChIP-seq signals in the gene bodies of JMJ16 target genes and the same number of randomly selected genes.

(F) Heatmaps of the gene body regions of JMJ16 target genes ranked by H3K4me3 levels in jmj16-1, showing concordant pattern of ChIP-seq signals of JMJ16-HA and H3K4me3 in Col-0 and jmj16-1.

(G) and (K) Genome tracks of RNA-seq, anti-H3K4me3, and anti-HA ChIP-seq data for WRKY53 (G) and SAG201 (K) loci in Col-0, jmj16-1, and JMJ16-HA plants. Structures of WRKY53 and SAG201. R1 and R2, specific regions used for ChIP-qPCR analysis. Y axis value means normalized read counts.

(H) and (L) RT-qPCR analysis of WRKY53 (H) and SAG201 (L) expression levels. eIF4a was used as an internal control. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3). Significant difference between Col-0 and jmj16-1 was determined by Student’s t test (****P < 0.0001).

(I) and (M) ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K4me3 methylation status at the WRKY53 (I) and SAG201 (M) loci. Anti-H3 and actin were used as internal references for ChIP-qPCR. Significant difference between Col-0 and jmj16-1 was determined by Student’s t test (****P < 0.0001).

(J) and (N) ChIP-qPCR analysis of the association of JMJ16-HA with the WRKY53 (J) and SAG201 (N) locus. Specific primers corresponding to the WRKY53 R1 region and SAG201 R2 region were used in the ChIP-qPCR analysis. Actin was used as an internal control. Different letters indicate significant differences among genotypes based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P < 0.0001).

Leaves 5 and 6 of 5-week–old long-day-grown Col-0, jmj16-1, and JMJ16-HA plants were used for RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, qRT-PCR, or ChIP-qPCR analyses. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3).

Because the homeostasis of H3K4me3 is dynamically maintained by the synergistic effects of members of the methyltransferase and demethylase families, we were interested in investigating whether the upregulation of these JMJ16 target genes exhibited significant changes in H3K4me3 modification at these loci. Thus, we performed ChIP-seq using the anti-H3K4me3 antibody to identify genome-wide hypermethylated H3K4me3 loci in wild-type and jmj16-1 leaves of the same stage as those used in RNA-seq. In the jmj16-1 mutant, H3K4me3 levels were increased at least 1.5-fold for 4,539 genes compared with the wild type (Supplemental Data Set 3). Among the 1,111 JMJ16 binding targets and transcriptionally upregulated genes in jmj16-1, 370 genes exhibited hypermethylation (fold change > 2) of H3K4me3 compared with the wild type (Figure 4A; Supplemental Data Set 4). These results suggest that JMJ16 directly is associated with these 370 genes and dominantly regulates H3K4me3 levels at these loci in wild-type plants. In jmj16-1 plants, the depletion of JMJ16 led to enhanced H3K4me3 levels at these loci, which subsequently upregulated the expression of these genes. Meta-gene analysis clearly revealed increased H3K4me3 levels, especially at transcription start site (TSS) regions, due to the depletion of JMJ16 in jmj16-1 (Figures 4D and 4F). Interestingly, the direct JMJ16 binding regions of genes with enhanced H3K4me3 levels were enriched in both the gene bodies and TSS regions (Figures 4E and 4F). Together, these results strongly support the notion that JMJ16 primarily regulates gene expression through the direct regulation of H3K4me3 levels in wild-type plants.

A comparison of JMJ16-associated genes and H3K4me3-hypermethylated genes in jmj16-1 with genes listed in the Leaf Senescence Database (LSD 2.0; Li et al., 2014) revealed that 325 genes were senescence-associated genes (Figure 4B; Supplemental Data Set 5). Of the 325 H3K4me3 hypermethylated SAGs that were associated with JMJ16, 138 were transcriptionally upregulated in jmj16-1 (Figure 4C; Supplemental Data Set 4). We selected five of these 138 overlapping SAGs to validate the RNA-seq and ChIP-seq results. Reverse transcription quantitative PCR(RT-qPCR) and ChIP-qPCR analysis confirmed the upregulated expression and increased H3K4me3 levels of all five genes, i.e. transcription factor gene WRKY53, SAG201, SAG13, Cysteine-Rich Receptor-Like Kinase gene CRK36, and transmembrane protein gene At5g20790 in 5-week–old jmj16-1 plants compared with the wild type (Figures 4G to I, and K to M; Supplemental Figure 7). These five genes include two genes encoding known positive regulators of leaf senescence, WRKY53 (Miao et al., 2004) and SAG201 (also known as SAUR36; Hou et al., 2013), as well as SAG13, CRK36, and At5g20790, which were all identified as JMJ16-target genes (Supplemental Data Set 4). ChIP-qPCR analysis confirmed that JMJ16-HA was directly associated with the chromatin regions of these genes (Figures 4J and 4N; Supplemental Figures 7D, 7H and 7L)).

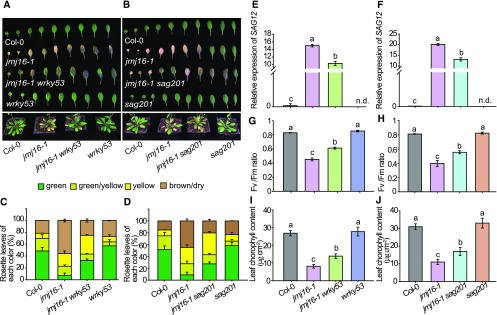

The ES Phenotype of jmj16 Is at Least Partly Due to Upregulated WRKY53 and SAG201 Expression

To determine if the ES phenotype of jmj16-1 is associated with increased WRKY53 and/or SAG201 expression, we generated jmj16-1 wrky53 and jmj16-1 sag201 double mutants by genetically crossing jmj16-1 with the delayed-senescence mutants, wrky53 and sag201. Evaluation of age-triggered leaf senescence in the wild type, double mutants, and the corresponding parental lines indicated that both the wrky53 and sag201 mutations partially suppressed the ES phenotype of jmj16-1 (Figure 5). Taken together, these results indicate that JMJ16 regulates leaf senescence at least partly through regulating WRKY53 and SAG201 expression.

Figure 5.

JMJ16 Negatively Regulates Leaf Senescence at Least Partly through WRKY53 and SAG201.

(A) and (B) wrky53 (A) and sag201 (B) mutations partially suppressed the ES phenotype of jmj16. Leaf senescence phenotypes of 7-week–old plants grown under long-day conditions.

(C) and (D) Quantification of the leaf senescence phenotype of 7-week–old plants grown under long-day conditions, as mentioned in Supplemental Figure 2. The means from three independent experiments and 15 plants were determined in each experiment. Error bars = ±se.

(E) to (J) Expression level of SAG12 (E) and (F), Fv/Fm (G) and (H), and Chlorophyll content (I) and (J) in leaves 5 and 6 of 6.5-week–old plants. Relative expression was normalized to that of eIF4a. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among genotypes based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P < 0.0001; n.d. = not detected).

Histone Demethylase Activity and Specific Domains of JMJ16 Are Required for the Regulation of Leaf Senescence

The fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) H3K4me3 demethylase, Lid, regulates developmental processes independently of its demethylase activity (Li et al., 2010). To determine whether the histone demethylase activity of JMJ16 is involved in the regulation of leaf senescence, we expressed constructs containing JMJ16-HA or JMJ16m-HA driven by the JMJ16 promoter in jmj16-1 plants (Supplemental Figures 6A to 6C). Although both JMJ16-HA and JMJ16m-HA were directly associated with the chromatin region of WRKY53 (Figure 3D), the expression of JMJ16-HA, but not JMJ16m-HA, rescued the ES phenotype of jmj16-1 and restored the transcription and H3K4me3 of WRKY53 to wild-type levels (Figures 3A to 3C), indicating that the ES phenotype of this mutant is associated with the impaired histone demethylase activity of JMJ16.

JMJ16 contains five distinct domains, including the JmjN, JmjC, C5HC2 zinc finger (zf-C5HC2), F/Y-rich N terminus (FYRN), and F/Y-rich C-terminal (FYRC) domains (Lu et al., 2008). To determine which domains are required for JMJ16 function, we generated four JMJ16 mutant constructs harboring internal deletions of the JmjN, JmjC, or zf-C5HC2 domains or both the FYRN and FYRC (FYRN/C) domains driven by the JMJ16 promoter (Supplemental Figure 6A). Like jmj16 plants, transgenic jmj16-1 plants expressing JmjN (Figures 3A to 3C; Supplemental Figures 6D and 6E), JmjC (Figures 3A to 3C; Supplemental Figures 6F and 6G), or FYRN/C (Figures 3A to 3C; Supplemental Figures 6J and 6K) internal deletion mutants of JMJ16 (referred to as JMJ16ΔJN-HA, JMJ16ΔJC-HA, and JMJ16ΔFYR-HA, respectively) exhibited an ES phenotype, and the transcript and H3K4me3 levels of WRKY53 were higher than those of wild type. By contrast, the expression of a JMJ16 deletion mutant lacking the zf-C5HC2 domain (referred to as JMJ16ΔZF-HA) rescued the ES phenotype of jmj16-1 and repressed the upregulated transcription and H3K4me3 levels of WRKY53 in the jmj16-1 genetic background (Figures 3A to 3C; Supplemental Figures 6H and 6I). These results indicate that the JmjN, JmjC, FYRN, and FYRC domains, but not the zf-C5HC2 domain, are required for the role of JMJ16 in the regulation of leaf senescence. We then investigated which domains of JMJ16 are required for its association with WRKY53. ChIP-qPCR analysis indicated that the JmjC and FYR domains are essential for the association of JMJ16 with WRKY53, but the JmjN and zf-C5HC2 domains are not (Figure 3D).

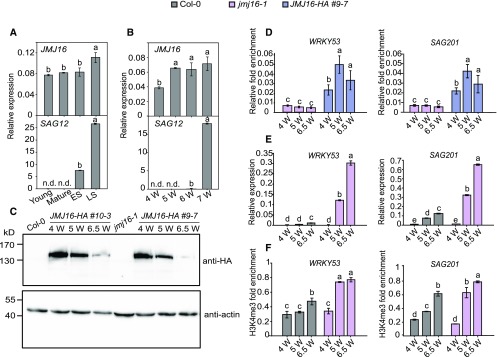

Age-Dependent Downregulation of JMJ16 May Be Responsible for the Activation of SAG Expression during Senescence

To further elucidate the role of JMJ16 in regulating chromatin modifications of SAGs during leaf senescence, we determined the transcript levels, protein abundance, and chromatin association of JMJ16 with SAGs during different developmental stages. JMJ16 transcript levels slightly increased in wild-type plants during the aging process (Figures 6A and 6B). We examined JMJ16 protein levels in JMJ16-HA transgenic plants (JMJ16-HA driven by the JMJ16 promoter expressed in the jmj16-1 background). Immunoblot analysis using anti-HA antibody revealed that JMJ16-HA protein levels were slightly lower in the leaves of 5-week–old plants as compared with 4-week–old plants but were substantially lower in the leaves of 6.5-week–old plants (Figure 6C). By contrast to the reduced JMJ16 levels, the levels of JMJ16 at WRKY53 and SAG201 were slightly higher in the leaves of 5- and 6.5-week–old plants as compared with 4-week–old plants (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

JMJ16 Regulates SAG Expression in an Age-Dependent Manner.

(A) Expression levels of JMJ16 and SAG12 in the leaves of long-day–grown wild-type plants at the indicated developmental stages. Young = nonsenescent and not fully expanded leaves; Mature = nonsenescent and fully expanded leaves; ES = early senescing stage leaves; LS = late senescing stage leaves. Relative expression was normalized to that of eIF4a. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3).

(B) Expression levels of JMJ16 and SAG12 in leaves 5 and 6 of long-day–grown wild-type plants at the indicated developmental stages. Relative expression was normalized to that of eIF4a. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3).

(C) JMJ16-HA protein levels in leaves 5 and 6 of long-day–grown JMJ16-HA (#9-7 and #10-3) transgenic plants at the indicated developmental stages. Total protein extracts isolated from Col-0 or jmj16-1 were used as negative controls. Anti-actin (EASYBIO BE0027) was used as a loading control. Anti-HA antibody (H6908; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect JMJ16-HA. JMJ16-HA indicates the expression of JMJ16-HA driven by the JMJ16 promoter in jmj16-1. 4 W, 5 W, and 6.5 W indicate 4-, 5-, and 6.5-week–old plants grown under long-day conditions, respectively.

(D) ChIP-qPCR analysis of the association of JMJ16-HA with the WRKY53 (left) and SAG201 (right) loci at the indicated developmental stages. Specific primers corresponding to the WRKY53 R1 region and SAG201 R2 region (indicated in Figure 3) were used in the ChIP-qPCR analysis. Actin was used as an internal control. Leaves 5 and 6 of jmj16-1 and JMJ16-HA plants were used for analyses. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3).

(E) RT-qPCR analysis of WRKY53 (left) and SAG201 (right) transcript levels. eIF4a was used as an internal control.

(F) ChIP-qPCR analysis of the H3K4me3 methylation status at the WRKY53 (left) and SAG201 (right) loci. Anti-H3 and actin were used as internal references for ChIP-qPCR. Leaves 5 and 6 of long-day–grown Col-0 and jmj16-1 plants at the indicated developmental stages were used in the RT-qPCR and ChIP-qPCR analyses. Error bars = ±sd (n = 3).

Different letters indicate significant differences based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P < 0.0001; n.d. = not detected).

Next, we monitored the transcript and H3K4me3 levels of WRKY53 and SAG201 at three developmental stages. In the leaves of 4-week–old wild-type and jmj16-1 plants, WRKY53 and SAG201 transcripts were barely detectable, although basal levels of H3K4me3 modification were present at these loci (Figures 6E and 6F). These results suggest that JMJ16 does not affect the transcription or H3K4me3 levels of the SAGs at this stage, because if JMJ16 has an impact, H3K4me3 and the transcript levels of the SAGs would be higher in jmj16-1. However, in the leaves of 5-week–old plants, the transcript and H3K4me3 levels of these SAGs were substantially higher jmj16-1 plants, but not in the wild type (Figure 6E and 6F), although no visible yellowing of leaves was observed in either line, suggesting that JMJ16 was able to affect gene expression and that the transition to senescence had begun in jmj16-1 at this stage. In the leaves of 6.5-week–old wild-type plants, the transcript and H3K4me3 levels of the SAGs significantly increased (Figure 6E and 6F), along with a substantial reduction in the level of JMJ16 (Figure 6C). Taken together, these results suggest that the decreasing abundance of JMJ16 protein during the aging process may be responsible for the increased H3K4me3 status and transcript levels of SAGs and the subsequent activation of leaf senescence.

DISCUSSION

The dynamic changes in H3K4me3 levels during leaf senescence may be regulated by H3K4me3 methyltransferases and/or demethylases; however, the enzymes that catalyze these changes have been elusive (Kim et al., 2018; Yolcu et al., 2018). We identified a JmjC domain-containing protein, JMJ16, which specifically demethylates H3K4me in Arabidopsis (Figure 2; Supplemental Figure 4). Loss-of-function jmj16 mutants exhibited an ES phenotype, which was rescued by complementation with JMJ16 (Figure 1). The conserved iron binding amino acids in the JmjC domain of JMJ16 are required for its enzymatic activity and its regulation of leaf senescence (Figures 2B and 2C, and 3A to 3C). RNA-seq and ChIP-seq analyses revealed that many SAGs are regulated by JMJ16 during leaf senescence through alterations of their associated H3K4me3 levels (Figure 4; Supplemental Figure 7). JMJ16 directly associates with the chromatin regions of WRKY53 and SAG201 and prevents precocious upregulation of the transcription and H3K4me3 levels of these genes to maintain proper leaf aging. This finding is supported by the genetic evidence that the wrky53 and sag201 mutations suppress the ES phenotype of jmj16 (Figures 4J, 4N, and 5).

In general, a histone demethylase is targeted to its target sites through its own DNA binding domain or those of its partner proteins. For example, the H3K27 demethylase, RELATIVE OF EARLY FLOWERING6, targets specific sites through its four tandem arrays of C2H2 zinc-finger domains, which directly bind to the CTCTGYTY motifs (Y=C/T) in its targets (Cui et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). The H3K4 demethylase, JMJ14, directly interacts with NAC domain-containing transcription factors through its FYRN/C domains, and the NAC transcription factors are required for the recruitment of JMJ14 to its specific target sites (Zhang et al., 2015). The factors that determine the target specificity of JMJ16 are currently unknown. JMJ16 contains JmjN, JmjC, zf-C5HC2, and FYRN/C domains (Lu et al., 2008). Studies in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) revealed that the JmjN domain is essential for the catalytic activity and protein stability of JmjC (Klose et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2011; Quan et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2013). Expression of a JMJ16 mutant protein lacking the JmjN domain did not rescue the ES-related phenotypes of jmj16, but it did not affect its association with WRKY53, suggesting that the JmjN domain is critical for the catalytic activity of JMJ16 but does not affect its association with chromatin (Figure 3). In budding yeast and mammals, the zf-C5HC2 domain of JmjC proteins is thought to be involved in DNA binding and is required for the protein’s function (Li et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2013). Strikingly, however, in JMJ16, the zf-C5HC2 domain is dispensable for its role in regulating leaf senescence and its association with chromatin (Figure 3), suggesting that other domain(s) of JMJ16 might be involved in its association with chromatin, such as the FYRN/C domains, because JMJ16 lacking FYRN/C domains could not associate with its targets and would subsequently not be able to rescue the ES phenotype of jmj16 (Figure 3). Similar to JMJ14, the FYRN/C domains of JMJ16 may interact with transcription factors, which recruit this protein to its specific target sites. The identification of JMJ16-interacting proteins should help us decipher the detailed mechanism underlying how JMJ16 is recruited to specific chromatin target sites and regulates the H3K4 methylation status of senescence-associated genes.

In animals, the histone H3K9 methyltransferase, G9a, stabilizes the association of both H3K4 methyltransferase and H3K4 demethylase at transcriptionally repressive target genes, where H3K4 demethylase removes the H3K4 methyltransferase-mediated active mark H3K4me3 (Chaturvedi et al., 2012). The detailed examination of H3K4me3 levels at the WRKY53 and SAG201 loci during leaf senescence performed in this study suggested that H3K4me3 modification is regulated by both H3K4me3 methylation and demethylation processes (Figure 6). The H3K4me3 levels of SAGs in 4-week–old wild-type and jmj16 leaves were similar (Figure 6F), suggesting that H3K4me3 levels are tightly controlled during this developmental stage in both the wild type and jmj16 mutant. In the leaves of 5-week–old (mature stage) JMJ16-HA complementation lines, the levels of association of WRKY53 and SAG201 with JMJ16 were slightly higher than those of the wild type (Figure 6D), but the H3K4me3 levels of the SAGs were not reduced in the wild type (Figure 6F). In jmj16-1, however, H3K4me3 levels at these loci were substantially upregulated at the mature stage (Figure 6F), suggesting that H3K4 methylation activity may also be required to maintain balance between H3K4me3 methylation/demethylation status at the mature stage. In the leaves of 6.5-week–old JMJ16-HA complementation lines, JMJ16 protein levels were substantially reduced (Figure 6C), and H3K4me3 levels at WRKY53 and SAG201 were increased in the wild type (Figure 6F), suggesting that the balance of H3K4me3 methylation/demethylation started to shift toward methylation in the wild type. Taken together, these findings suggest that the age-dependent increase in H3K4 levels of SAGs is regulated by both H3K4 methyltransferase(s) and JMJ16 in Arabidopsis and that the gradually decreasing levels of JMJ16 during leaf aging may contribute to the upregulation of H3K4me3 levels observed for the SAGs. Although the detailed mechanisms are unknown, H3K4me3 methylation/demethylation are thought to be involved in regulating aging in mammals (Greer et al., 2010). Thus, H3K4me3 methyltransferase/demethylase may have conserved functions in the regulation of aging in both plants and mammals.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

All Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) lines used in this study were in the Col-0 background. The jmj16-1 (SAIL_535_F09), jmj16-2 (SAIL_80_F06), jmj16-3 (SALK_029530), jmj17-1 (SALK_014109), jmj17-2 (SALK_037362), and sag201 (SALK_142329) lines were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre. The jmj14-1 (SALK_135712) and jmj18-1 (SALK_073422) were described in Lu et al. (2010) and Yang et al. (2012a). The wrky53 mutant (SALK_034157) was a gift from Dr. Ulrike Zentgraf (Department of General Genetics, University of Tuebingen) and has been described in a previous report (Miao and Zentgraf, 2007). The wrky53 jmj16 and sag201 jmj16 double mutants were generated by genetic crossing of jmj16-1 with wrky53 and sag201, respectively. The primers used for genotyping are listed in Supplemental Data Set 6. Surface-sterilized seeds were imbibed for 3 d at 4°C to break seed dormancy. The stratified seeds were grown on MS (Murashige and Skoog) plates for 6 d, and the seedlings were transferred to soil. All plants were grown in a culture room at 22°C under a 16-h-light (∼100 μmol m−2 s−1; five 6500 K T5 fluorescent lamps plus one 2700 K T5 fluorescent lamp)/8-h-dark cycle.

Analysis of Leaf Senescence Phenotypes

Rosette leaves of plants at the indicated developmental stages were detached and photographed. The mature stage and ES stages mentioned in this article were defined based on previous work, with minor modifications (Van der Graaff et al., 2006). Briefly, mature stage leaves indicate fully expanded leaves 5 and 6 of plants without a visible yellowing phenotype. ES leaves represent leaves 5 and 6 of plants with an ∼10% to 25% tip-yellowing phenotype. The chlorophyll content analysis method has been described previously (Porra et al., 1989). The Fv/Fm ratio was determined using a PAM 2000 portable chlorophyll fluorometer connected by a leaf-clip holder with a trifurcated fiber optic cable (Heinz) based on previous work (Cai et al., 2010).

Plasmid Construction

To generate pCambia1303-ProJMJ16:JMJ16, a fragment containing a 2.0-kb promoter region and 3.2-kb genomic fragment of JMJ16 was amplified with primer pairs MiniPro and genomic1-F SalI/MiniPro and genomic1-R NcoI and cloned into the pBluescript vector to generate pBluescript-JMJ16P/G1. pBluescript-JMJ16P/G1 was digested with SalI/NcoI and inserted into the SalI/NcoI sites of the pCambia1303 vector to generate pCambia1303-JMJ16P/G1. The remaining genomic fragment of JMJ16 was amplified with the No-genomic2 F/No-genomic2-R primer pair and digested with NcoI to generate a 5′-sticky/3′-blunt end insert (JMJ16G2). pCambia1303-JMJ16P/G1 was digested with BstEII, blunted with Mung bean (Vigna radiata) enzyme, and digested with NcoI. The digested JMJ16G2 insert was ligated into the pCambia1303-JMJ16P/G1 vector to generate pCambia1303-ProJMJ16:JMJ16.

To generate pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔJN-HA, pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔJC-HA, pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔZF-HA, and pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔFYR-HA, a genomic DNA fragment containing the promoter and coding region of JMJ16 was amplified with the J16 Promoter XmaI F/J16 No stop SalI R primer pair, and ligated into the pBluescript vector to generate pBluescript-JMJ16P/G. Fragments containing each internal deletion were generated using specific primers listed in Supplemental Data Set 6, and the wild-type JMJ16 genomic sequence in pBluescript-JMJ16P/G was replaced with each of these fragments. These pBluescript-JMJ16 deletion constructs were digested with XmaI/SalI and ligated into the XmaI/SalI sites of the modified pCambia1300-HA vector.

To construct pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16-HA (XF2090), ∼0.8 kb of the 3′ UTR of JMJ16 was cloned using the CX9288 and CX9289 primers and introduced into pCambia1300-HA after NcoI digestion. The full-length genomic region and native promoter of JMJ16 were then amplified using the CX9286 and CX9287 primers and inserted into pCambia1300-HA-UTR by XmaI and PstI digestion. pJMJ16:JMJ16m-HA (XF2091) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange Kit (Stratagene) with the HX2343 and HX2344 primers.

To construct pEG101-Pro35S:JMJ16-YFP-HA (XF2177), the full-length genomic coding region of JMJ16 was amplified using the CX3619 and CX3620 primers, cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen), and introduced by the Lambda Recombination reaction into the pEarleyGate101 (pEG101) vector with a C-terminal YFP-HA tag. pEG101-Pro35S:JMJ16m-YFP-HA (XF2178) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange Kit (Stratagene) with the HX2343 and HX2344 primers.

To construct pGEX-5X-1-JMJ14596, a 1,788-basepair (bp) complementary DNA (cDNA) fragment of JMJ14 was amplified with primer pairs J14 (596) SalI F and J14 (596) NotI R. The PCR product was digested with SalI/NotI and inserted into the SalI/NotI sites of the pGEX-5X-3 vector to generate pGEX-5X-3-JMJ14596.

To construct pGEX-5X-1-JMJ16670, a 2,010-bp cDNA fragment of JMJ16 was amplified with primer pairs J16 (670) XbaI F and J16 (670) SalI R. The PCR product was digested with XbaI/SalI and inserted into the XbaI/SalI sites of the pGEX-5X-1-Myc vector to generate pGEX-5X-1-JMJ16670.

Transgenic Plant Generation

The pCambia1303-ProJMJ16:JMJ16, pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16-HA, pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16m-HA, pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔJN-HA, pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔJC-HA, pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔZF-HA, and pCambia1300-ProJMJ16:JMJ16ΔFYR-HA constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells (strain GV3101) and then stably transformed into jmj16-1 mutant plants using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). pEG101-Pro35S:JMJ16-YFP-HA was stably transformed into Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0, as described above.

In Vivo Histone Demethylation Assay

The procedures used for the in vivo histone demethylation assay were described in Lu et al. (2011). Briefly, pEG101-Pro35S:JMJ16-YFP-HA and pEG101-Pro35S:JMJ16m-YFP-HA constructs were transformed into A. tumefaciens cells (strain EHA105), and the cells were then infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. To determine the specific histone methylation status, immunostaining was performed using histone methylation-specific antibodies (H3K4me3: Millipore 07-473, 1:100; H3K4me2: Millipore 07-030, 1:500; H3K4me1: Millipore 07-436, 1:100; H3K9me3: Millipore 07-442, 1:100; H3K9me2: Millipore 07-441, 1:200; H3K9me1: Millipore 07-450, 1:100; H3K27me3: Millipore 07-449, 1:100; H3K27me2: Millipore 07-452, 1:100; H3K27me1: Millipore 07-448, 1:100; H3K36me3: Abcam ab9050, 1:100; H3K36me2: Millipore 07-274, 1:100; and H3K36me1: Millipore 07-548, 1:100) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:200; Invitrogen). The YFP and Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescent signals were photographed under a fluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus). ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) software was used to quantify the fluorescent signals in immunolabeled nuclei as described in Lu et al. (2011).

In Vitro Histone Demethylation Assay

An in vitro demethylation assay was performed as previously described, with minor modifications (Yang et al., 2010). Briefly, GST-JMJ14596, GST-JMJ16670, and GST proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli and affinity-purified with Glutathione Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare). A quantity of 4.0 μg of calf thymus histones (Sigma-Aldrich H9250) was incubated with affinity-purified GST-JMJ14596 (1 μg), GST-JMJ16670 (2 μg), or GST (5 μg) in 40 μL reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 50 μM Fe[NH4]2[SO4]2, 1 mM α-ketoglutarate, and 2 mM ascorbate) for 5 h at 37°C. The reaction product was analyzed by protein gel blot analysis with anti-H3K4me3 (Abcam ab8580), anti-H3K4me2 (Millipore 07-030), anti-H3K4me1 (Millipore 07-436), H3K9me2 (Millipore 07-441), H3K9me1 (Millipore 07-450), H3K27me3 (Millipore 07-449), H3K27me2 (Millipore 07-452), H3K27me1 (Millipore 07-448), H3K36me3 (Abcam ab9050), H3K36me2 (Millipore 07-274), H3K36me1 (Millipore 07-548), and anti-H3 (Abcam ab1791).

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from seedlings and rosette leaves with TRIZOL (RNAiso Plus; TaKaRa) and reverse-transcribed with a Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-qPCR analysis was performed on a MP3000 instrument (Stratagene) with SYBR Premix ExTaq (TaKaRa); 40 cycles were used for all qPCR analyses. Primer sequences for RT-qPCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Data Set 6.

ChIP Assay and Library Preparation

ChIP was performed as described previously with minor modifications (Lu et al., 2011). Briefly, 1 g of tissue from leaves 5 and 6 at the indicated developmental stages from Col-0, jmj16-1, and transgenic jmj16-1 plants expressing full-length JMJ16, JMJ16m, JmjN, JmjC, zf-C5HC2, or FYRN/C internal deletion mutants driven by its own promoter were harvested, ground in liquid nitrogen, and cross-linked with formaldehyde. Anti-HA (H6908; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-H3K4me3 (07-473; Millipore), and anti-H3 (ab1791; Abcam) were used for immunoprecipitation as described in Zhang et al. (2015). Immunoprecipitated DNA was used for ChIP-seq DNA library preparation or qPCR analysis. A ChIP-seq library was constructed using the NEBNext DNA Library Prep Master Mix Set for Illumina (E6040S; New England BioLabs).

ChIP-seq and RNA-seq Analysis

ChIP-seq reads were aligned to the Arabidopsis genome (TAIR10 release) using Bowtie 2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) with default parameters and the local alignment model. Duplicated reads and low mapping quality reads (< 30) were identified and removed using SAMtools (Li et al., 2009). Enriched intervals were identified using model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (Zhang et al., 2008) with default parameters. Density maps of reads for visualization were based on counts of the 200-bp extension of sequencing reads in the 3′ direction (as described in Ernst et al., 2011) followed by Reads Per Genomic Content normalization. Hypermethylation of H3K4me3 between the jmj16 mutant and wild type were detected using the ChIPDiff program with a 1.5-fold change as described in Lu et al. (2011). Significantly enriched regions of JMJ16 were identified based on twofold change compared to the jmj16-1 genetic background. RNA-seq reads were firstly aligned to the Arabidopsis transcriptome (based on the TAIR10 annotation) using the software TopHat2 (Kim et al., 2013) with default parameters for further visualization in the Integrated Genome Browser (BioViz) with ChIP-seq data. Meanwhile, RNA-seq reads were remapped and quantitatively evaluated using Salmon (Patro et al., 2017). Differentially expressed genes between the jmj16-1 mutant and wild type were identified using 1.5-fold change as the cut-off. Meta-gene analysis and heatmap plotting were performed using deepTools (Ramírez et al., 2016).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (Supplemental Data Set 7).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this study can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database under the following accession numbers: CRK36 (At4g04490), eIF4a (At3g13920), JMJ14 (At4g20400), JMJ16 (At1g08620), JMJ17 (At1g63490), JMJ18 (At1g30810), SAG12 (At5g45890), SAG13 (At2g29350), SAG201 (At2g45210), UBC21 (At5g25760), WRKY53 (At4g23810). RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data from this article can be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus data library under accession number GSE115362.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Characterization of jmj16 T-DNA insertion mutants.

Supplemental Figure 2. Mutation in JMJ16, but not JMJ14, JMJ17, or JMJ18, causes ES phenotype.

Supplemental Figure 3. Additional examples of JMJ16 complementation transgenic plants.

Supplemental Figure 4. JMJ16 does not exhibit H3K9, H3K27, or H3K36 demethylase activity in vivo or in vitro.

Supplemental Figure 5. JMJ16 expression levels in JMJ16 OE transgenic plants.

Supplemental Figure 6. Characterization of transgenic plants expressing JMJ16 mutant proteins.

Supplemental Figure 7. Transcript and H3K4me3 methylation levels of JMJ16-HA associated genes are upregulated in jmj16-1.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Differentially expressed genes in jmj16-1.

Supplemental Data Set 2. JMJ16 target genes.

Supplemental Data Set 3. Hypermethylation of H3K4me3 in jmj16-1.

Supplemental Data Set 4. JMJ16 target genes with upregulated expression and hyperH3K4me3 in jmj16-1.

Supplemental Data Set 5. LSD 2.0 genes with JMJ16 binding and hyperH3K4me3 in jmj16-1.

Supplemental Data Set 6. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 7. Parameters used for ANOVA statistical analyses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31788103 and 91540203 to X.C., and grant 31471363 to J.B.J.), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant XDB27030201 to X.C.), the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant QYZDY-SSW-SMC022 to X.C.), and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (The Innovative Academy of Seed Design to X.C. and J.B.J.). We thank Dr. Ulrike Zentgraf for the wrky53 (SALK_034157) seeds.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.L., S.Z., X.C., and J.B.J. designed the study; P.L., S.Z., X.L., X.F.Z., B.C., Y.H.J., and D.N. performed the research; P.L., S.Z., B.Z., X.C., J.L., and J.B.J. analyzed the data; P.L., S.Z., B.Z., X.C., and J.B.J. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Ay N., Irmler K., Fischer A., Uhlemann R., Reuter G., Humbeck K. (2009). Epigenetic programming via histone methylation at WRKY53 controls leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 58: 333–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S., Riaño-Pachón D.M., Mueller-Roeber B. (2008). Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 10 (Suppl 1): 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusslan J.A., Rus Alvarez-Canterbury A.M., Nair N.U., Rice J.C., Hitchler M.J., Pellegrini M. (2012). Genome-wide evaluation of histone methylation changes associated with leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 7: e33151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai B., Zhang A., Yang Z., Lu Q., Wen X., Lu C. (2010). Characterization of Photosystem II photochemistry in transgenic tobacco plants with lowered Rubisco activase content. J. Plant Physiol. 167: 1457–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Wu J., Tong X.J., Zhou J.Q., Ding J. (2011). Crystal structure of the catalytic core of Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone demethylase Rph1: Insights into the substrate specificity and catalytic mechanism. Biochem. J. 433: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi C.P., Somasundaram B., Singh K., Carpenedo R.L., Stanford W.L., Dilworth F.J., Brand M. (2012). Maintenance of gene silencing by the coordinate action of the H3K9 methyltransferase G9a/KMT1C and the H3K4 demethylase Jarid1a/KDM5A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 18845–18850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X., et al. (2016). REF6 recognizes a specific DNA sequence to demethylate H3K27me3 and regulate organ boundary formation in Arabidopsis. Nat. Genet. 48: 694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J., et al. (2011). Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature 473: 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer E.L., Maures T.J., Hauswirth A.G., Green E.M., Leeman D.S., Maro G.S., Han S., Banko M.R., Gozani O., Brunet A. (2010). Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature 466: 383–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou K., Wu W., Gan S.S. (2013). SAUR36, a small auxin up RNA gene, is involved in the promotion of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 161: 1002–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Lan W., Li D., Deng B., Lin W., Ren Y., Miao Y. (2018). WHIRLY1 occupancy affects histone lysine modification and WRKY53 transcription in Arabidopsis developmental manner. Front. Plant Sci. 9: 1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y., Sun H., Yuan W., Wang Y., Li Q., Liu Y., Li Y., Qian W. (2016). SUVH2 and SUVH9 couple two essential steps for transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 9: 1156–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S.L. (2013). TopHat2: Accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14: R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Woo H.R., Kim J., Lim P.O., Lee I.C., Choi S.H., Hwang D., Nam H.G. (2009). Trifurcate feed-forward regulation of age-dependent cell death involving miR164 in Arabidopsis. Science 323: 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim J.H., Lyu J.I., Woo H.R., Lim P.O. (2018). New insights into the regulation of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 69: 787–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose R.J., Gardner K.E., Liang G., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Zhang Y. (2007). Demethylation of histone H3K36 and H3K9 by Rph1: A vestige of an H3K9 methylation system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 3951–3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Greer C., Eisenman R.N., Secombe J. (2010). Essential functions of the histone demethylase Lid. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Peng J., Wen X., Guo H. (2012). Gene network analysis and functional studies of senescence-associated genes reveal novel regulators of Arabidopsis leaf senescence. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 54: 526–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Zhao Y., Liu X., Peng J., Guo H., Luo J. (2014). LSD 2.0: An update of the leaf senescence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: D1200–D1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C.Y., Wang L.C., Lo W.S. (2013). Dissociation of the H3K36 demethylase Rph1 from chromatin mediates derepression of environmental stress-response genes under genotoxic stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 24: 3251–3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P.O., Kim H.J., Nam H.G. (2007). Leaf senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58: 115–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.W., Shao C.R., Zhang C.J., Zhou J.X., Zhang S.W., Li L., Chen S., Huang H.W., Cai T., He X.J. (2014). The SET domain proteins SUVH2 and SUVH9 are required for Pol V occupancy at RNA-directed DNA methylation loci. PLoS Genet. 10: e1003948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Li G., Cui X., Liu C., Wang X.J., Cao X. (2008). Comparative analysis of JmjC domain-containing proteins reveals the potential histone demethylases in Arabidopsis and rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50: 886–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Cui X., Zhang S., Liu C., Cao X. (2010). JMJ14 is an H3K4 demethylase regulating flowering time in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 20: 387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Cui X., Zhang S., Jenuwein T., Cao X. (2011). Arabidopsis REF6 is a histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase. Nat. Genet. 43: 715–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Zentgraf U. (2007). The antagonist function of Arabidopsis WRKY53 and ESR/ESP in leaf senescence is modulated by the jasmonic and salicylic acid equilibrium. Plant Cell 19: 819–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Laun T., Zimmermann P., Zentgraf U. (2004). Targets of the WRKY53 transcription factor and its role during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 55: 853–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Jiang J., Ren Y., Zhao Z. (2013). The single-stranded DNA-binding protein WHIRLY1 represses WRKY53 expression and delays leaf senescence in a developmental stage-dependent manner in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 163: 746–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S.A., Lee S.Y., Chung I.K., Lee C.H., Nam H.G. (1996). A senescence-associated gene of Arabidopsis thaliana is distinctively regulated during natural and artificially induced leaf senescence. Plant Mol. Biol. 30: 739–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan R., Reumann S., Lisik P., Tietz S., Olsen L.J., Hu J. (2018). Proteome analysis of peroxisomes from dark-treated senescent Arabidopsis leaves. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 60: 1028–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patro R., Duggal G., Love M.I., Irizarry R.A., Kingsford C. (2017). Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14: 417–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra R.J., Thompson W.A., Kriedemann P.E. (1989). Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975: 384–394. [Google Scholar]

- Quan Z., Oliver S.G., Zhang N. (2011). JmjN interacts with JmjC to ensure selective proteolysis of Gis1 by the proteasome. Microbiology 157: 2694–2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F., Ryan D.P., Grüning B., Bhardwaj V., Kilpert F., Richter A.S., Heyne S., Dündar F., Manke T. (2016). deepTools2: A next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (W160–W165): W160-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek S., Somssich I.E. (2002). Targets of AtWRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes Dev. 16: 1139–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Graaff E., Schwacke R., Schneider A., Desimone M., Flügge U.I., Kunze R. (2006). Transcription analysis of Arabidopsis membrane transporters and hormone pathways during developmental and induced leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 141: 776–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Gao J., Gao S., Li Z., Kuai B., Ren G. (2018). REF6 promotes lateral root formation through de-repression of PIN1/3/7 genes. J. Integr. Plant Biol.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H.R., Chung K.M., Park J.H., Oh S.A., Ahn T., Hong S.H., Jang S.K., Nam H.G. (2001). ORE9, an F-box protein that regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13: 1779–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H.R., Kim H.J., Nam H.G., Lim P.O. (2013). Plant leaf senescence and death—regulation by multiple layers of control and implications for aging in general. J. Cell Sci. 126: 4823–4833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., et al. (2012a). A companion cell-dominant and developmentally regulated H3K4 demethylase controls flowering time in Arabidopsis via the repression of FLC expression. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Mo H., Fan D., Cao Y., Cui S., Ma L. (2012b). Overexpression of a histone H3K4 demethylase, JMJ15, accelerates flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 31: 1297–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Jiang D., Jiang J., He Y. (2010). A plant-specific histone H3 lysine 4 demethylase represses the floral transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 62: 663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yolcu S., Li X., Li S., Kim Y.J. (2018). Beyond the genetic code in leaf senescence. J. Exp. Bot. 69: 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., et al. (2015). C-terminal domains of histone demethylase JMJ14 interact with a pair of NAC transcription factors to mediated specific chromatin association. Cell Discov. 1: 15003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Bernatavichute Y.V., Cokus S., Pellegrini M., Jacobsen S.E. (2009). Genome-wide analysis of mono-, di- and trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 10: R62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C.A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D.S., Bernstein B.E., Nusbaum C., Myers R.M., Brown M., Li W., Liu X.S. (2008). Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9: R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Jiang Y., Yu D. (2011). WRKY22 transcription factor mediates dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells 31: 303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]