Abstract

The spectral parameters of hyperpolarized 129Xe exchanging between airspaces, interstitial barrier, and red blood cells (RBCs) are sensitive to pulmonary pathophysiology. This study sought to evaluate whether the dynamics of 129Xe spectroscopy provide additional insight, with particular focus on quantifying cardiogenic oscillations in the RBC resonance. 129Xe spectra were dynamically acquired in eight healthy volunteers and nine subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). 129Xe FIDs were collected every 20 ms (TE = 0.932 ms, 512 points, dwell time = 32 μs, flip angle ≈ 20°) during a 16 s breathing maneuver. The FIDs were pre-processed using the spectral improvement by the Fourier thresholding technique and fit in the time domain to determine the airspace, interstitial barrier, and RBC spectral parameters. The RBC and gas resonances were fit to a Lorentzian lineshape, while the barrier was fit to a Voigt lineshape to account for its greater structural heterogeneity. For each complex resonance the amplitude, chemical shift, linewidth(s), and phase were calculated. The time-averaged spectra confirmed that the RBC to barrier amplitude ratio and RBC chemical shift are both reduced in IPF subjects. Their temporal dynamics showed that all three 129Xe resonances are affected by the breathing maneuver. Most notably, several RBC spectral parameters exhibited prominent oscillations at the cardiac frequency, and their peak-to-peak variation differed between IPF and healthy volunteers. In the IPF versus healthy cohort, oscillations were more prominent in the RBC amplitude (16.8 ± 5.2 versus 9.7 ± 2.9%; P = 0.008), chemical shift (0.43 ± 0.33 versus 0.083 ± 0.05 ppm; P < 0.001), and phase (7.7 ± 5.6 versus 1.4 ± 0.8°; P < 0.001). Dynamic 129Xe spectroscopy is a simple and sensitive additional tool that probes the temporal variability of gas exchange and may prove useful in discerning the underlying causes of its impairment.

Keywords: 129Xe spectroscopy, dynamic spectroscopy, hyperpolarized 129Xe, hyperpolarized gas imaging, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPF, lung, spectroscopy quantitation

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI is emerging as a valuable means of imaging lung structure and function.1,2 Arguably, its most significant feature as a probe for lung function is enabled by its solubility in blood and biological tissues, combined with distinct in vivo chemical shifts that reflect the local environment.3 Recent years have seen significant efforts to both characterize and exploit these unique properties to gain insights into cardiopulmonary physiology and pathophysiology.

The spectral properties of 129Xe have been well characterized in vitro and in vivo. In many mammals 129Xe dissolved in blood exhibits separate resonances for red blood cells (RBCs) and plasma; in human blood they are separated by approximately 22 ppm.4–7 Similarly, 129Xe spectra acquired in the human lung also exhibit a unique RBC peak at 217 ppm, relative to the gas-phase resonance at 0 ppm, as well as a resonance consisting of 129Xe dissolved in both plasma and parenchymal tissues.8 Because these environments also form the barrier to diffusive 129Xe or O2 transfer to RBCs, it is often termed the “barrier resonance.”9 Although recent high-resolution spectroscopy suggests that the barrier resonance may contain additional structure that is not well represented by a single Lorentzian peak,10 it is generally considered to have a frequency shift of about 198 ppm.

Recently, these unique spectroscopic properties of 129Xe have been exploited to yield 3D images of pulmonary gas exchange.11 Such imaging has revealed impaired gas exchange in various diseases affecting the cardiopulmonary system. In patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), for example, 129Xe uptake in the barrier is significantly enhanced throughout much of the lung, while its transfer to RBCs is focally impaired.12 By contrast, in the setting of COPD with emphysema, both barrier uptake and RBC transfer are diminished.13 Moreover, 129Xe gas exchange MRI has recently revealed that RBC transfer is also impaired in pulmonary vascular disease.14 The extraordinary sensitivity of 129Xe diffusive barrier uptake and RBC transfer to a wide range of pathologies is promising, even as it presents new challenges. Patients are increasingly appreciated to present with a wide range of co-morbidities such as asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, combined fibrosis and emphysema, or secondary pulmonary hypertension (PH), all of which may require different approaches to therapy. Therefore, it becomes important to develop additional non-invasive metrics that can differentiate the underlying pathophysiologies responsible for impaired gas exchange.

To this end the spectral structure of 129Xe uptake in the cardiopulmonary circuit offers a wealth of additional information. Specifically, in vitro work by Wolber et al. found a non-linear dependence of the RBC chemical shift on blood oxygen saturation (sO2).5 This was confirmed by Norquay et al., and used to approximate the change in sO2 of a healthy volunteer over a 35 s breath-hold.4 Interestingly, the RBC shift was found by Kaushik et al. to be significantly lower in patients with IPF than in healthy volunteers.8 Although recent work treating the barrier as consisting of two resonances decreased the magnitude of this effect, the RBC shift remained significantly lower in IPF versus healthy subjects, along with five other spectral parameters that were found to differ.10

Beyond characterizing the static 129Xe gas transfer spectra, the temporal dynamics of the fit parameters provide an opportunity to gain significant additional insights. To this end, preliminary work has reported a monotonic decay in the RBC chemical shift during extended breath-holds, as well as intriguing cardiac pulsations in the amplitude of the RBC resonance.4,15,16 However, this pioneering work was focused primarily on characterizing 129Xe uptake in the alveolar septal unit on the 90–100 ms timescale via the chemical shift saturation recovery (CSSR) method.17,18 As such, these studies were limited by relatively low temporal resolution, and moreover did not investigate whether the dynamics of other spectral parameters derived from each resonance could be of interest.

Thus, the objective of this work is to expand upon efforts to characterize the temporal dynamics of 129Xe transfer, using higher temporal and spectral resolution as well as complex time-domain curve fitting to robustly quantify the oscillations associated with cardiopulmonary interactions. We sought to evaluate temporal changes in FIDs acquired every 20 ms to fully characterize the dynamics of each resonance as reflected by its amplitude, chemical shift, linewidth(s), and phase. To test the sensitivity of these parameters to changes in lung inflation, we quantified them continuously during a simple breathing maneuver consisting of inspiration, breath-hold, and exhalation. As an initial illustration of the sensitivity and potential utility of this approach, we sought to identify the key static and temporally varying spectral parameters, establish initial normal reference values, and determine those that differentiate healthy volunteers from subjects with IPF.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Subject recruitment

This study was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was provided by all subjects prior to participation. Dynamic 129Xe spectra were acquired in eight healthy volunteers (seven males and one female; 26.4 ± 4.9 years old) and nine subjects with IPF (seven males and two females; 66.1 ± 5.6 years old). Healthy volunteers had no known pulmonary disorders, no cardiac arrhythmias, and no history of smoking. Subjects with IPF were diagnosed according to ATS criteria, confirming a UIP pattern on CT or from surgical lung biopsy.19 All IPF patients and six out of eight healthy volunteers completed pulmonary function tests (PFTs), which included measuring the forced vital capacity (FVC) by spirometry and the diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) by the single-breath method.

2.2 |. Xenon polarization and delivery

Using a commercially available polarizer (Model 9810, Polarean, Durham, NC, USA), 300 mL of isotopically enriched 129Xe (85%) was hyperpolarized to approximately 20% via rubidium vapor spin-exchange optical pumping. Hyperpolarized 129Xe was cryogenically accumulated and thawed into a 1 L Tedlar bag (Jensen Inert Products, Coral Springs, FL, USA). This provided a 51 mL dose equivalent (the product of polarization, enrichment, and xenon volume) of hyperpolarized 129Xe.20 The bag volume was expanded to 1 L using ultra-high-purity N2.

After two preparatory breaths, subjects inhaled 129Xe from functional residual capacity, held their breath for 8 s, and then slowly exhaled.8 Data acquisition began during inhalation before the subject began their breath-hold. During MRI, each subject’s heart rate and oxygen saturation were monitored using an MR-compatible monitoring system (Expression Model 865214; Invivo, Orlando, FL, USA).

2.3 |. 129Xe spectroscopy

Spectra were acquired using a 1.5 T GE scanner running the 15 M4 EXCITE platform (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). Subjects were fitted with a quadrature vest coil (Clinical MR Solutions, Brookfield, WI, USA) tuned to 17.66 MHz. Spectra were acquired with the transmit frequency tuned to selectively excite the dissolved-phase 129Xe using a 1.2 ms three-lobe sinc pulse, applied at a frequency 3832 Hz (217 ppm) above the gas phase. Over the course of the 16 s breathing maneuver, 802 free induction decays (FIDs) were acquired with 512 samples per FID, echo time (TE) = 0.932 ms, repetition time (TR) = 20 ms, dwell time per point = 32 μs, flip angle ≈ 20°. The echo time was defined from the middle of the1.2 ms sinc pulse to the acquisition of the first data point.

2.4 |. Spectroscopic processing

Prior to fitting the spectra, two filtering steps were applied to improve spectral SNR while minimizing the need to sacrifice the temporal resolution needed to capture the cardiopulmonary dynamics. First, the raw FIDs were processed using the spectral improvement by Fourier thresholding (SIFT) method.21,22 This involves Fourier transforming the raw data along the indirect time dimension (time with respect to the breath-hold) and retaining only the Fourier coefficients that exceed a predetermined threshold of two standard deviations above the noise in the temporal-frequency domain. The data are then Fourier transformed back along the indirect frequency dimension to undergo spectral curve fitting. This preprocessing step thus filters the non-dominant frequencies out of the indirect time dimension to smooth temporal changes between FIDs, while leaving the spectral-frequency domain intact. The time-domain SIFT-filtered FIDs were then averaged using a 5 FID sliding boxcar window filter and subsequently underwent complex fitting in the time domain using a custom MATLAB toolkit.10 The effects of SIFT processing as well as sliding window averaging are illustrated for representative FIDs and spectra in Figure 1.

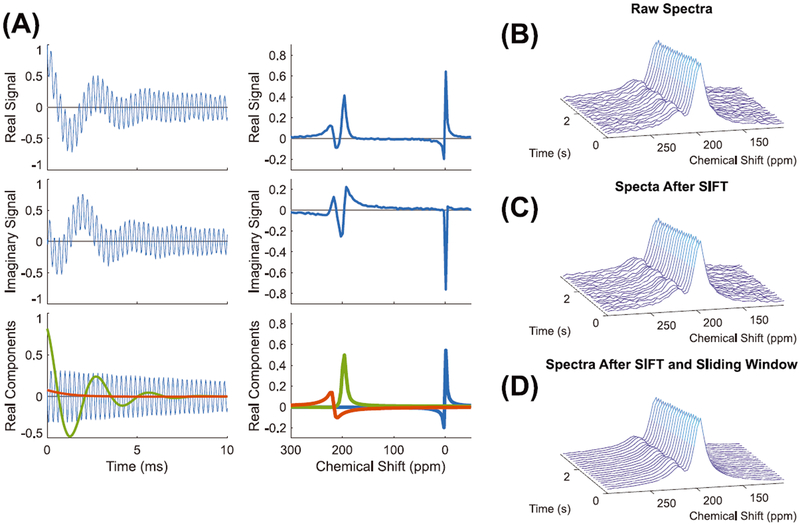

FIGURE 1.

A, The real and imaginary components for a raw FID and spectrum along with the real components of the associated spectroscopic fitting. B-D, Consecutive spectra before SIFT (B), after SIFT (C), and after sliding window averaging (D). The raw spectra have an SNR of 10.7, which was increased to 12.3 using SIFT and further enhanced to 15.0 after sliding window averaging

Although much prior literature has treated the dissolved-phase 129Xe spectra as consisting of two simple Lorentzian RBC and barrier resonances, recent work has shown that the barrier resonance is more structured.10 This was addressed by Robertson et al. by allowing the barrier to consist of two independent Lorentzian resonances. However, this requires the fitting of four additional degrees of freedom, which with the available SNR and spectral resolution of the dynamically acquired data was found to return ill-conditioned fits. Instead, to allow for the extra structure of the barrier resonance, it was fit to a Voigt model. This lineshape represents the convolution of a Lorentzian peak with a Gaussian distribution23 and requires only one additional fitting degree of freedom. Specifically, it returns two distinct linewidth parameters—the Lorentzian linewidth (FWHM) and Gaussian linewidth (FWHMG). This model was chosen under the assumption that at the microscopic level the 129Xe barrier resonances can be described as Lorentzian, but that each experience slightly different frequency shifts caused by differences in the local cellular and susceptibility environments, leading to a broader, Voigt-shaped profile.24

The overall fitted signal is calculated using Equation 1, with each resonance being characterized by four spectral parameters: amplitude (a), frequency (f), phase (φ), and FWHM. For the barrier resonance, a fifth parameter, FWHMG, was also extracted. Fitting of the barrier resonance was initialized with equal Lorentzian and Gaussian linewidths.

| (1) |

All frequencies (Hz) were reported as the chemical shift (in ppm) above the frequency of the gaseous 129Xe resonance.

2.5 |. Normalizing and quantifying cardiogenic spectroscopic changes in the RBC resonance

Although numerous quantitative parameters can be analyzed and extracted from the three resonances during the three periods of the breathing maneuver, we focused specifically on characterizing temporal variations in the 129Xe RBC resonance occurring at the cardiac frequency (~1 Hz). Such cardiogenic fluctuations in the spectral parameters were visually isolated by first correcting the amplitude of the RBC peak for magnetization decays caused by T1 decay, blood flow, and RF-induced depolarization during the breath-hold. This was done by assuming that the dissolved- and gas-phase 129Xe were in dynamic equilibrium and that all of the factors contributing to signal loss could be incorporated into a single apparent T1 decay constant T1app. This was measured by fitting the RBC amplitude within the breath-hold period to A e−t=T1app, returning a mean T1app for all subjects of 13.6 ± 2.7 s. This was then used to correct the RBC signal, and the remaining temporal changes in signal amplitude were expressed as a percentage change from A, the amplitude value determined in the T1app fit. Each of the RBC spectral parameters were further high-pass filtered with a 0.5 Hz cutoff frequency to remove any residual baseline variation. The corrected and filtered parameter plots were then fit to a sinusoid with phase offset:

| (2) |

where Apk − pk is the peak-to-peak amplitude, f c is the cardiac frequency, t is time in seconds, and φ is a phase offset. For each subject, the cardiac frequency f c was derived from fitting the RBC amplitude oscillations and this value was used in fitting all the other RBC spectral parameter oscillation amplitudes (chemical shift, linewidth, and phase).

2.6 |. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in MATLAB. A Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine if the differences between healthy normal and IPF subjects were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The Mann–Whitney U test was chosen in light of the small sample size and potentially non-parametric distribution. Additionally, because the U test uses ranks to compare groups, it is fairly robust against outliers.

3 |. RESULTS

For each subject, the age, sex, PFT results, and the magnitude of the oscillations in the RBC spectral parameters are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Subject demographics, PFT results, and oscillation information. ND (no data) shown for two healthy volunteers, indicates that they did not undergo PFTs. SD is the standard deviation

| PFTs (% predicted) | Intensity RBC:barrier | RBC oscillations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject ID | Sex | Age | FVC (L) | DLco (mL/m in/mm Hg) | Amplitude (%) | Chemical shift (ppm) | FWHM (ppm) | Phase (°) | ||

| Healthy | 1 | M | 23 | 5.8 (96%) | 33.9 (88%) | 0.532 | 14.3 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.0 |

| 2 | M | 21 | 6.2 (100%) | 39.2 (114%) | 0.685 | 8.2 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 2.4 | |

| 3 | M | 26 | 5.0 (98%) | 28.8 (89%) | 0.558 | 13.8 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 1.7 | |

| 4 | M | 27 | 3.2 (65%) | 26.5 (92%) | 0.643 | 9.1 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 1.5 | |

| 5 | M | 37 | 3.3 (67%) | 16.8 (55%) | 0.395 | 9.4 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 2.5 | |

| 6 | M | 23 | ND | ND | 0.789 | 6.8 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.9 | |

| 7 | M | 24 | 6.3 (112%) | 34.0 (93%) | 0.530 | 6.3 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.4 | |

| 8 | F | 29 | ND | ND | 0.546 | 10.1 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.7 | |

| Mean | 26.3 | 5.0 (89.7%) | 29.9 (88.5%) | 0.585 | 9.7 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 1.4 | ||

| SD | 5.0 | 1.4 (19.2%) | 7.8 (119.0%) | 0.119 | 2.9 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.8 | ||

| IPF | 11 | M | 56 | 2.1 (94%) | 7.0 (26%) | 0.100 | 24.9 | 1.16 | 0.65 | 19.8 |

| 12 | F | 61 | 2.5 (85%) | 11.6 (63%) | 0.132 | 14.9 | 0.74 | 0.35 | 13.4 | |

| 13 | M | 68 | 1.9 (49%) | 11.6 (48%) | 0.211 | 19.9 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 5.8 | |

| 14 | M | 70 | 4.3 (99%) | 17.0 (72%) | 0.143 | 13.9 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 8.5 | |

| 15 | M | 62 | 2.7 (53%) | 16.1 (60%) | 0.230 | 16.1 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 4.7 | |

| 16 | F | 67 | 1.6 (74%) | 8.4 (51%) | 0.114 | 17.2 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 6.7 | |

| 17 | M | 67 | 3.0 (71%) | 14.6 (58%) | 0.283 | 6.3 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 1.2 | |

| 18 | M | 69 | 3.6 (76%) | 13.6 (53%) | 0.284 | 20.5 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 4.4 | |

| 19 | M | 75 | 2.3 (54%) | 11.4 (48%) | 0.164 | 18.0 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 4.8 | |

| Mean | 66.1 | 2.7 (72.8%) | 12.4 (53.2%) | 0.185 | 16.8 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 7.7 | ||

| SD | 5.6 | 0.9 (18.1%) | 3.3 (12.8%) | 0.070 | 5.2 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 5.6 | ||

3.1 |. Quantifying static spectral parameters

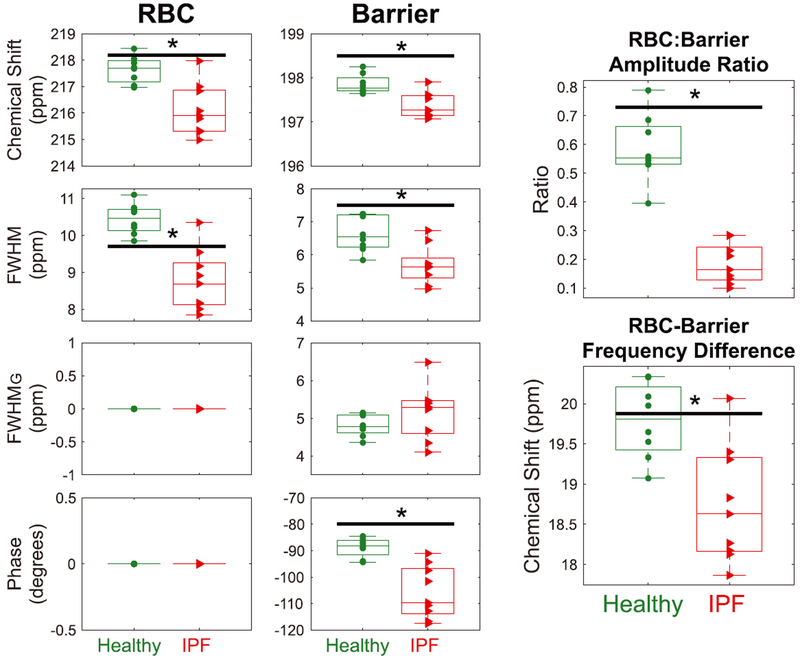

Prior to analyzing the 129Xe spectral dynamics, the static parameters were determined from an average over the first second of the breath-hold. The resulting RBC and barrier fit parameters, as well as relevant derived ratios, are compared between the healthy and IPF cohorts in Figure 2. The mean RBC:barrier amplitude ratio for healthy volunteers was 0.58 ± 0.12, which was significantly reduced in IPF patients to 0.18 ± 0.07 (P < 0.001). The RBC to barrier amplitude ratio (RBC:barrier ratio) correlated strongly with DLCO (R2 = 0.82; P < 0.001) and moderately with FVC (R2 = 0.54; P = 0.003). The RBC frequency was 1.5 ppm lower in the IPF cohort (P = 0.004) and its Lorentzian line width was 1.7 ppm narrower (P = 0.001). The barrier frequency was also 0.5 ppm lower in IPF (P = 0.0025), and the Lorentzian component of its linewidth 0.9 ppm smaller (P = 0.006); the FWHMG did not differ from that of the healthy cohort (P = 0.2). These differences contributed to the phase difference between barrier and RBC resonances being 17.0° smaller compared to the healthy cohort (P = 0.006). Note that all phases were reported relative to that of the RBC resonance which was set to zero as a reference. However, since all fitting is performed on the complex FIDs in the time domain, the phases relative to one another are preserved. For completeness, the RBC and barrier frequencies were plotted, relative both to the gas phase and to one another, to ensure that the RBC chemical shift difference between healthy volunteers and subjects with IPF is not driven by a difference in the gas-phase reference frequencies.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of the static RBC and barrier chemical shifts, linewidths, and phases derived using the barrier Voigt model in healthy volunteers and subjects with IPF during the first second of breath-hold. The RBC phase has been set to 0° as a reference. Two derived metrics, RBC:barrier ratio and the difference in chemical shift between the RBC and barrier peak, are also compared. The black bar with the asterisk indicates statistical difference between groups (P < 0.05)

3.2 |. 129Xe spectral changes over the course of the breathing maneuver

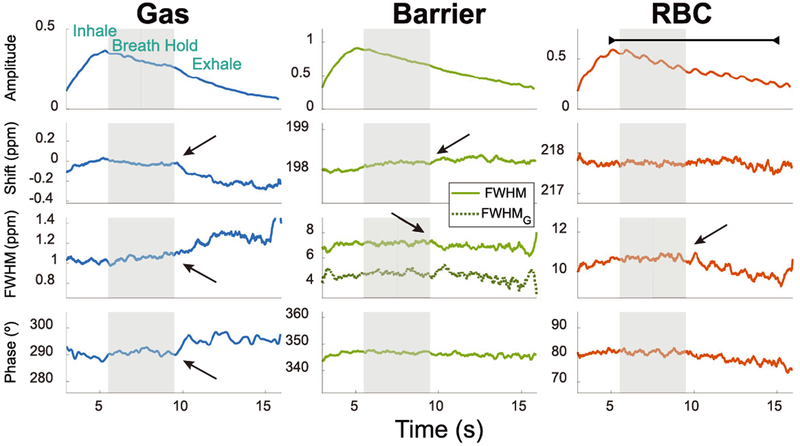

The spectral dynamics of all three 129Xe resonances are displayed for a representative healthy volunteer (Subject 6) in Figure 3. The breathing maneuver is reflected in each of the fit parameters, readily demarking the inhalation, breath-hold, and exhalation periods. As the subject exhales, the gas resonance shifts negatively by 0.11 ppm in frequency and broadens by 0.1 ppm. Additionally, exhalation causes the barrier resonance to shift positively by 0.06 ppm and its FWHM to narrow by 0.29 ppm. The RBC resonance appears to be influenced by both inhalation and exhalation, primarily in its linewidth, which, like the barrier, narrows slightly (0.37 ppm) during exhalation. The RBC amplitude also exhibits a prominent periodicity at a frequency of 58 cycles per minute, which is consistent with the subject’s heart rate, recorded by pulse oximetry immediately prior to and after the acquisition (61 and 65 bpm, respectively). These dynamics are also present, although more faintly, at the same frequency in the RBC chemical shift and phase.

FIGURE 3.

Temporal changes in the spectroscopic parameters of the 129Xe gas, barrier, and RBC resonances in a representative healthy subject (Subject 6) during inhalation, breath-hold (gray bar), and exhalation. All amplitudes were normalized to the maximum 129Xe barrier signal. The barrier resonance contains both a Lorentzian FWHM (solid light green line) and a Gaussian FWHM (dark green dotted line). The arrows highlight changes in the spectroscopic chemical shift, linewidth, and phase that occur upon exhalation. The line above the RBC amplitude highlights the cardiogenic oscillations, occurring at a frequency of 58 cycles per minute in this subject

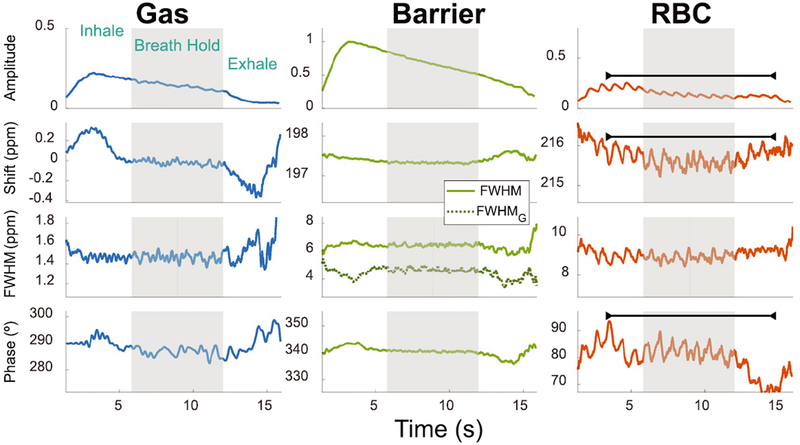

Figure 4 displays the same spectral dynamics, plotted for a subject with IPF (Subject 13). As in the healthy volunteer, the gas-phase parameters reflect both the inhale and exhale dynamics, which are also clearly seen in the barrier resonance through an increasing chemical shift and a narrowing of both linewidth parameters upon exhalation. The RBC resonance subtly shows the inhalation, while exhalation is well demarked by its increasing chemical shift and FWHM, coupled with decreasing phase. In this IPF patient, the RBC amplitude is also periodic at a frequency near the subject’s heart rate pre-and post-scan (71 cycles per minute compared to 70 and 72 bpm, respectively). Interestingly, this cardiac periodicity is also prominent in both the RBC chemical shift and phase.

FIGURE 4.

Temporal changes in the spectroscopic parameters of the 129Xe gas, barrier, and RBC resonances in a subject with IPF (Subject 13) during inhalation, breath-hold (gray bar), and exhalation. All amplitudes are normalized to the maximum barrier-phase 129Xe signal. Unlike the healthy volunteer, the RBC resonance exhibits notable oscillations at the heart rate not only in amplitude but also in chemical shift and phase, as indicated by the black bar. The oscillation frequency is consistent with a heart rate of 71 bpm

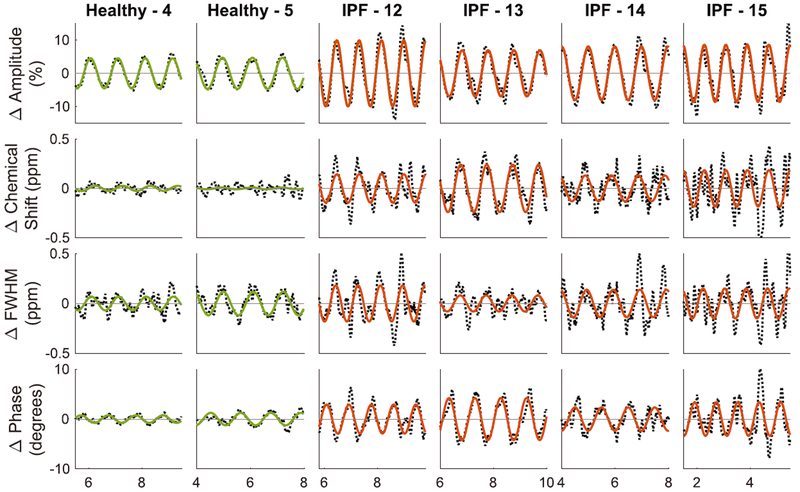

These cardiogenic oscillations in the RBC spectral parameters are better appreciated in the normalized and detrended plots as shown for two representative healthy volunteers and several IPF patients in Figure 5. In the healthy volunteers, the RBC amplitude varied peak-to-peak (pk-pk) by 9.1% and 9.4%, while oscillations in the RBC chemical shift and phase remained below 0.05 ppm and 2.5° respectively. By contrast, the first subject with IPF (IPF-12) not only exhibited more than twice the RBC amplitude variation (19.9% pk-pk), but also exhibited oscillations in RBC chemical shift that were nearly six times larger at 0.29 ppm, while phase varied nearly fourfold more at 5.8°. Such oscillations in RBC amplitude, frequency, and phase were also notable in the other IPF subjects depicted.

FIGURE 5.

The normalized and detrended RBC spectral parameter dynamics during a breath-hold from two representative healthy volunteers and four subjects with IPF. The solid line represents the sinusoidal fit for each parameter

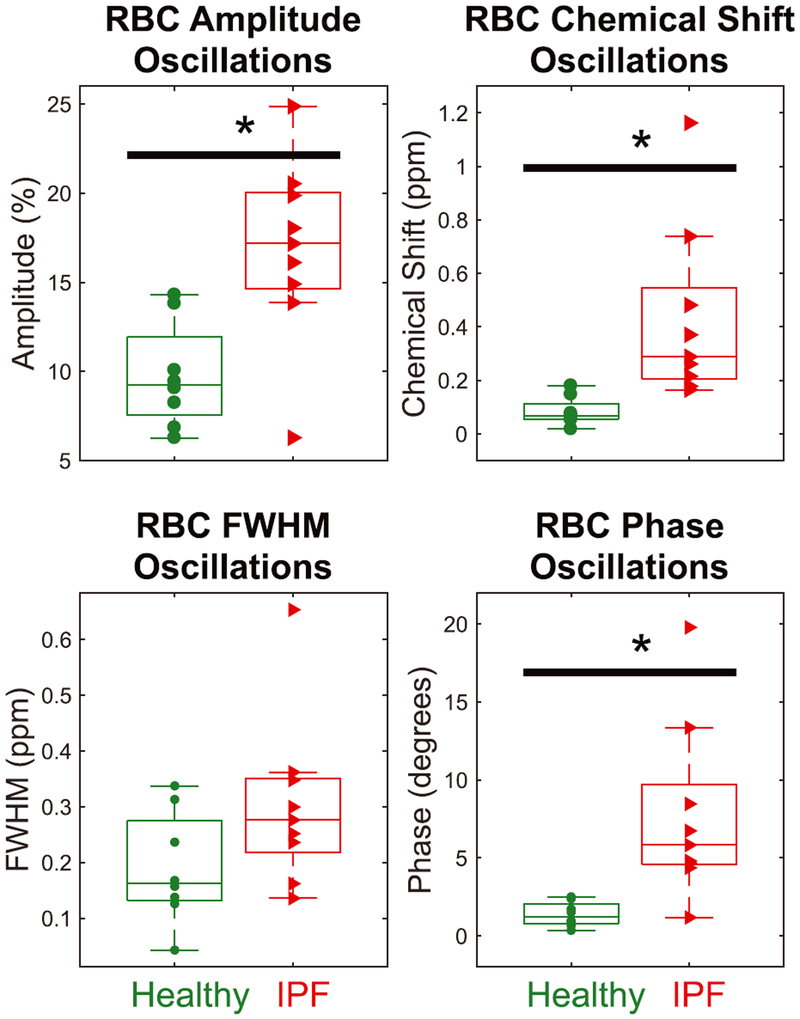

3.3 |. Amplitude of oscillations varies between IPF and healthy subjects and correlates with DLCO

The magnitude of the cardiogenic oscillations in the RBC spectral parameters is compared between healthy volunteers and IPF patients in Figure 6. In the IPF versus healthy cohort, RBC amplitude variations were nearly twice as high (16.8 ± 5.2% versus 9.7 ± 2.9%; P = 0.008), chemical shift oscillations were more than five times as high (0.43 ± 0.33 ppm versus 0.083 ± 0.05 ppm; P < 0.001), and RBC phase oscillations were more than five times as high (7.7 ± 5.6° versus 1.4 ± 0.8°; P < 0.001). Only the RBC linewidth was not statistically different between the two cohorts (0.3 ± 0.2 ppm versus 0.2 ± 0.1 ppm; P = 0.1).

FIGURE 6.

Comparing peak-to-peak cardiogenic oscillations in RBC spectral parameters during the breath-hold for healthy versus IPF subjects. Oscillations in the RBC amplitude, chemical shift, and phase are significantly larger for IPF subjects than healthy volunteers (P = 0.008, P = 0.001, and P = 0.002). The black bar with the asterisk indicates statistical difference between groups (P < 0.05)

The magnitude of the RBC amplitude oscillations correlated moderately with DLCO (R2 = 0.56; P = 0.002) and FVC (R2 = 0.43; P = 0.01), while RBC phase oscillations correlated weakly only with DLCO (R2 = 0.37; P = 0.02). None of the other RBC spectral parameters oscillations correlated with either FVC or DLCO.

4 |. DISCUSSION

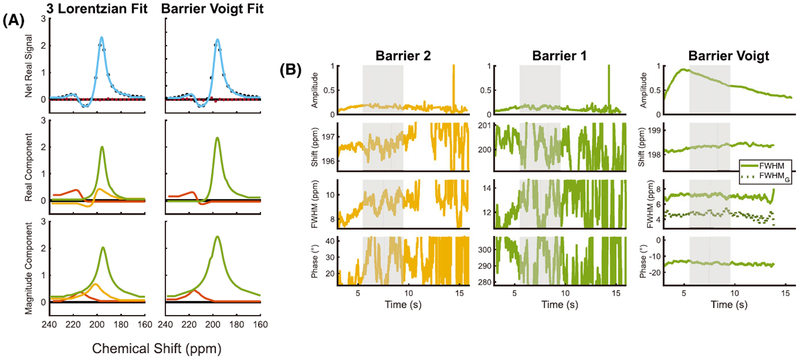

4.1 |. Benefits of using a barrier Voigt model

Before discussing the major findings of cardiogenic spectral oscillations, we briefly revisit the choice and benefits of the barrier Voigt model compared with the previously described two- and three-Lorentzian models. The barrier Voigt model was selected based on the residual fitting error, stability of the returned spectral parameters over the course of the acquisition, and consistency of the resulting fit parameter ranges with published literature values. This barrier Voigt model was found to more robustly fit the 129Xe-barrier resonance dynamics than the “three-Lorentzian” fit model that allows for one RBC and two distinct barrier resonances. Although the three-Lorentzian model returns a lower residual error than barrier Voigt when fitting high-resolution, high-SNR static spectra,10 it is not well suited for the lower SNR and spectral resolution present in the dynamic 129Xe acquisition. This is evidenced by highly variable fits for the two barrier resonances, as seen in Figure 7B. By contrast, the barrier Voigt model was able to capture the additional structure of the barrier resonance, while remaining stable over the course of the acquisition. This is likely attributable to it requiring only one additional degree of freedom rather than the four required to fit the barrier to two Lorentzian resonances. Moreover, the two-component dissolved-phase fitting of RBCs to a Lorentzian and barrier to a Voigt model leaves intact the current three-compartment model of gas exchange that forms the basis of gas exchange imaging methods and CSSR analysis.25

FIGURE 7.

A, Dissolved-phase fits for a large average of FIDs exhibit minimal residual error for both the three-Lorentzian and the barrier Voigt models. B, Dynamically acquired spectroscopy for a healthy volunteer (Subject 6) returns ill-conditioned fits for the barrier resonances in the three-Lorentzian model, which is overcome by the barrier Voigt model

Importantly, comparing the fits of a large average of data found the barrier Voigt model to return similar RBC parameters as the three-Lorentzian fit. The barrier Voigt model returned an RBC:barrier ratio of 0.59 ± 0.11 for healthy volunteers that is reasonably consistent with previous two- and three-peak Lorentzian fittings of the dissolved resonances, which are 0.55 ± 0.13 and 0.44 ± 0.07 respectively,8,10 and correctly captures the striking reduction in this ratio in subjects with IPF. The Voigt model also maintained the previously reported correlation between the RBC:barrier ratio with both DLCO and FVC.

4.2 |. Origins of temporal dynamics

The temporal changes in the 129Xe spectra directly report on the physiological dynamics of gas exchange in the lung and pulmonary capillaries. It is striking to find that nearly all the spectral parameters reflect dynamics associated with the breathing maneuver. This is particularly well defined during exhalation, which is accompanied by an increasing gas-phase linewidth, combined with a corresponding narrowing of both dissolved-phase peaks. This narrowing, which is inversely related to the apparent transverse relaxation time, T*2, could suggest improving local field inhomogeneity, which, in the lung, is dominated by the bulk susceptibility difference of Δχ ≈ 9 ppm between air and tissue.26 During exhalation, the passive compression of the lung moves air out of the alveolar sacs and reduces aggregate alveolar volume.27 This, in turn, increases the volume fraction of tissue relative to air while mean capillary diameter increases along with the average alveolar wall thickness.28,29 Thus, during exhalation, fewer dissolved-phase xenon atoms reside near the air-tissue boundaries, causing RBC and barrier linewidths to narrow. By contrast, gas-phase xenon atoms are now more likely to reside near a tissue interface, and therefore the gas-phase linewidth increases.

The high-frequency dynamics of 129Xe-RBC transfer provide an intriguing window on how the cardiac cycle affects gas exchange. The RBC signal in these acquisitions arises predominantly from 129Xe nuclei interacting with RBCs in the pulmonary capillary bed. This strong localization stems from using a relatively large flip angle (~20°), combined with a repetition time that is short (TR = 20 ms) in relation to the RBC transit time (~750 ms). Thus, the magnetization of 129Xe atoms in the dissolved phase is quickly destroyed by RF pulses and can only be replenished through continued diffusive gas transfer from the airspaces.30 However, once 129Xe atoms move to larger vessels beyond the gas exchange units, such replenishment no longer occurs, and any residual magnetization is quickly destroyed by RF pulsing. Therefore, the fluctuations we detect in the RBC resonance provide evidence that 129Xe-RBC transfer at the alveolar-capillary interface is temporally dependent on blood volume oscillations driven by the cardiac cycle dynamics and pulmonary vascular impedance.

The oscillations in the RBC signal amplitude reflect a cyclic change in the number of polarized 129Xe atoms interacting with the RBCs over the course of the cardiac cycle. This observation is likely caused by cardiogenic fluctuations in capillary blood volume. At systole, the pulmonary capillaries experience slightly elevated blood pressure with a concomitant decrease at diastole.31 Such pressure changes likely affect capillary blood volume, as recently demonstrated by synchrotron imaging over the course of a respiratory cycle.32 Here, we found the relative RBC amplitude fluctuations to be nearly twice as large in subjects with IPF, suggesting that these patients experience relative changes in capillary blood volume over the cardiac cycle that are larger than in healthy volunteers. This is likely attributable to a decreased effective capillary volume while cardiac output is preserved. In fact, patients with IPF often exhibit pulmonary hypertension with only limited reversibility,33 and this has generally been attributed to the destruction of the pulmonary capillary bed in regions of fibrosis.12 Thus, the cardiac stroke volume is distributed to a smaller capillary bed, causing a larger relative change in systole and diastole, and results in larger relative RBC signal oscillations.33

Although previous work on temporally resolved 129Xe spectroscopy has also reported the barrier resonance to exhibit weak amplitude periodicity,4,34 we did not find such oscillations in this work. We hypothesize this to be attributable to a more complete decomposition of the RBC and barrier peaks by fitting the complex FIDs in the time domain. To date, most reports on 129Xe spectroscopy have relied on fitting non-complex data in the frequency domain after manual zero- and first-order phasing of the spectra. However, phasing of broad and overlapping dissolved-phase 129Xe resonances is challenging and the resulting fits may not be completely decomposed. By contrast, our approach fits both the real and imaginary data simultaneously in the time domain without relying on manual phasing, and thus may more robustly fit these resonances. Nonetheless, we do acknowledge that the barrier signal arises from both interstitial tissues and plasma, the latter of which should exhibit volume oscillations in synchrony with the RBCs. However, we can approximate the contribution of plasma to the barrier signal using the solubility of xenon in RBC and plasma (0.27 and 0.094).35 In an idealized case of blood consisting of equal volumes of RBC and plasma (hematocrit of 0.5), this would yield an RBC:plasma ratio of about 3. However, in vivo, for healthy volunteers, we observe an RBC:barrier ratio of only 0.58. This is five times smaller than that predicted for pure blood and the additional barrier signal derives from the interstitial tissues, which therefore comprise about four-fifths of the in vivo barrier signal. Thus, we estimate that plasma contributes only about one-fifth of the barrier signal, and thus any cardiogenic oscillations likely fall below the detection limit of our method.

The observation of cardiogenic oscillations in the RBC chemical shift in patients with IPF is particularly intriguing given that in vitro studies have shown that the RBC frequency depends non-linearly on blood oxygenation level, sO2.4,5 Over the physiologically relevant range of sO2 = 0.6–0.98, the RBC chemical shift increases sigmoidally by more than 4 ppm. This would suggest that the observed pulsations in the RBC chemical shift of0.43 ppm reflect global sO2 changes of order 0.07 in the pulmonary capillaries, assuming a maximum sO2 of 0.95. The fact that RBC frequency pulsations are seen in IPF, but not healthy subjects, suggests this is a potentially unique signature of retarded diffusive transfer of oxygen across the alveolar-capillary barrier. That is, as deoxygenated blood enters the capillary beds at systole, it is slower to oxygenate in patients with significant interstitial thickening. In a healthy normal volunteer, capillary RBCs reach full oxygenation in about 250 ms, or a third of the total capillary transit time,36 and thus, the average sO2 in RBCs experienced by 129Xe is likely skewed towards full oxygenation. In contrast, the thicker interstitial barrier tissues in patients with IPF slow the diffusion of gases, and consequently sO2 levels in the pulmonary capillary beds are likely more broadly distributed. The way in which this translates into RBC chemical shift oscillations can be understood as follows. During roughly each cardiac cycle, the pulmonary capillary blood volume turns over and must become re-saturated with O2 and 129Xe. In healthy volunteers, both oxygen and 129Xe will rapidly diffuse across the thin blood-gas barrier, resulting in the majority of 129Xe atoms interacting with fully oxygenated blood over most of the capillary transit path. By contrast, the thickened barrier tissue in subjects with IPF will cause the diffusion of both gases to be delayed, but once129Xe arrives to interact with blood early in the capillary transit path, it will experience lower oxygenation. In IPF, it is only towards the end of the capillary transit path the blood reaches full saturation and 129Xe experiences its maximal shift. Thus, in the presence of interstitial disease, 129Xe experiences a greater variability in blood oxygenation throughout the cardiac cycle, leading to the observed chemical shifts. Hence, while a healthy volunteer and subject with IPF may have the same distal O2 saturation level, 129Xe spectroscopy potentially detects differences in the capillary sO2 variation by directly probing the alveolar-capillary interface.

It should be mentioned that the maximum observed RBC chemical shift oscillation, 1.66 ppm, is approximately one-third of the calculated resolution of the underlying spectra. However, we note that the problem here is not assigning absolute chemical shifts, but rather reporting on their cyclical deviations from baseline. This relative shift is derived from curve fitting the underlying peaks, comprised of many data points, to a well-defined function. Thus, quantifying the chemical shift oscillations becomes an issue of measurement precision more than absolute accuracy, and will be affected by SNR and lineshape stability over the course of the cardiac cycle. To this end, it should be noted that the 129Xe chemical shift in RBCs can also change in response to the local susceptibility environment.16 Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that the cardiac cycle could change the susceptibility environment in a way that contributes to the observed RBC chemical shift oscillations. However, such susceptibility changes would be expected to affect the RBC and barrier resonances equally, causing both frequencies to oscillate. Since this is not observed in our work, and since the effects of the sO2 on the RBC chemical shift are well documented, we suggest that the RBC periodicity is, at least in part, attributable to changes in oxygenation. However, the static shift of the RBC resonance observed in the IPF population could be more strongly influenced by fibrosis-related susceptibility changes. We must, at this stage, acknowledge that it is difficult to discern the underlying causes of static and dynamic changes in the RBC chemical shift and determine the absolute precision with which it can be measured.

From a technical perspective, the cardiac pulsations are even more prominently detected in the phase of the 129Xe-RBC resonance. The phase is linearly related to the chemical shift and thus the two should be well correlated, and this is readily seen in subject with IPF (r2 = 0.95). However, the correlation is less apparent in healthy volunteers, given that neither parameter exhibits strong oscillations. Regardless of the methodology, the observation of pulsations in 129Xe RBC chemical shift and phase may ultimately prove to be a unique signature of the delayed oxygenation associated with interstitial lung disease. It would certainly require further study to demonstrate the ability to differentiate the causes of dyspnea attributable to interstitial disease from other causes of gas exchange impairment such as pulmonary vascular disease.14

It is noteworthy that the RBC spectral oscillations correlated either weakly or not at all with PFTs. This likely indicates that such measures are probing aspects of cardiopulmonary physiology that are different from those measured by PFTs. We hypothesize that the RBC amplitude oscillations are enhanced in IPF as a preserved cardiac stroke volume is directed to a diminished capillary vascular bed. This suggests that RBC amplitude oscillations are more closely related to pulmonary vascular conditions, which are typically evaluated by cardiac catheterization. It might thus be tempting to speculate that for conditions such as pulmonary arterial hypertension the amplitude of the oscillations could be diminished rather than enhanced. Moreover, it is somewhat surprising that the degree of RBC chemical shift oscillation is not correlated with DLCO, a key disease indicator in IPF. This may suggest that 129Xe chemical shift oscillations are measuring a unique aspect of lung physiology, potentially reflecting those regions of disease activity where perfusion persists in the presence of interstitial thickening. As such, it could ultimately prove to be a marker of disease activity that could be targeted by therapy.

Given the potential promise of quantifying RBC spectral parameter oscillations for diagnostic and prognostic applications, it will be valuable to investigate additional means to optimize the acquisition strategies used to measure them. Specifically, the trade-offs between flip angle and repetition time, TR, merit consideration. The acquisition strategy used in this work sought to maximize temporal resolution (TR = 20 ms) but doing so sacrificed both SNR and spectral resolution. It is conceivable that TR could be reduced to about 200 ms while still adequately resolving the approximately 1 s periodicity of the cardiac cycle. Similarly, the 20° flip angle used in this work could be increased to better confine the 129Xe magnetization to the gas exchange units, and potentially confer greater sensitivity to chemical shift oscillations. Alternatively, higher temporal resolution could be tested in order to better characterize the shape of the oscillations, which may contain information to differentiate pre-capillary versus post-capillary vascular obstruction.

4.3 |. Study limitations

The work presented here focused primarily on developing and optimizing the spectral processing and quantification methods needed to extract robust quantitative metrics. Thus, the clinical observations presented here should be considered preliminary. In addition to using a relatively modest sample size, the healthy volunteers were not age matched to the IPF cohort; therefore, we are unable to separate the effects of age and disease on the various parameters. However, we did not observe any general age-related trends in this small sample of volunteers. Nonetheless, it will clearly be necessary to verify the observations reported here in a larger cohort of age-matched healthy subjects and patients with IPF, as well as applying the method in other disease populations.

5 |. CONCLUSION

In this study, we established a method of acquiring, processing, and analyzing over a simple 16 s spectroscopic acquisition and breathing maneuver 129Xe spectra that yield a series of novel parameters, which can be used to further characterize gas exchange. The collected FIDs were optimally fit by using a Lorentzian lineshape for the RBC and gas resonances and a Voigt lineshape for the barrier resonance. This approach accommodated the additional structure of the barrier resonance, while limiting the degrees of freedom such that the fitting algorithm converged, even for the lower SNR and spectral resolution of the dynamic acquisition. Spectroscopic fit parameters for each 129Xe resonance were determined with 20 ms temporal resolution. Analysis of the static spectral parameters found features differentiating the IPF and healthy cohorts that were largely consistent with previous studies. Their dynamics showed all three resonances to be sensitive to the breathing maneuver, with distinct changes in the RBC and gas linewidths. Most notably, the RBC amplitude, chemical shift, and phase were found to oscillate at the cardiac frequency. These oscillations were significantly larger in patients with IPF than in healthy controls. Thus, careful analysis of both static and dynamic 129Xe spectra can potentially provide a wide array of additional information that can help further discern the different underlying causes of gas exchange impairment.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

HHS, Grant/Award Number: N268201700001C; NIH/NHLBI, Grant/Award Numbers: R01 HL105643 and R01 HL126771

Abbreviations used:

- CSSR

chemical shift saturation recovery

- DLCO

diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- FWHM

Lorentzian linewidth

- FWHMG

Gaussian linewidth

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- PFT

pulmonary function test

- RBC

red blood cell

- RBC:barrier ratio

RBC to barrier amplitude ratio

- SIFT

spectral improvement by Fourier thresholding

REFERENCES

- 1.Kruger SJ, Nagle SK, Couch MJ, Ohno Y, Albert M, Fain SB. Functional imaging of the lungs with gas agents. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43(2):295–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matin TN, Rahman N, Nickol AH, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: lobar analysis with hyperpolarized 129Xe MR imaging. Radiology. 2016;282(3):857–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherubini A, Bifone A. Hyperpolarised xenon in biology. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2003;42(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norquay G, Leung G, Stewart NJ, Wolber J, Wild JM. 129Xe chemical shift in human blood and pulmonary blood oxygenation measurement in humans using hyperpolarized 129Xe NMR. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(4):1399–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolber J, Cherubini A, Leach MO, Bifone A. Hyperpolarized 129Xe NMR as a probe for blood oxygenation. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43(4):491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruppert K, Mata JF, Brookeman JR, Hagspiel KD, Mugler JPIII. Exploring lung function with hyperpolarized 129Xe nuclear magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(4):676–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdeen N, Cross A, Cron G, et al. Measurement of xenon diffusing capacity in the rat lung by hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI and dynamic spectroscopy in a single breath-hold. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(2):255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaushik SS, Freeman MS, Yoon SW, et al. Measuring diffusion limitation with a perfusion-limited gas—hyperpolarized 129Xe gas-transfer spectroscopy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Appl Physiol. 2014;117(6):577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleveland ZI, Virgincar RS, Qi Y, Robertson SH, Degan S, Driehuys B. 3D MRI of impaired hyperpolarized 129Xe uptake in a rat model of pulmonary fibrosis. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(12):1502–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson SH, Virgincar RS, Bier EA, et al. Uncovering a third dissolved-phase 129Xe resonance in the human lung: quantifying spectroscopic features in healthy subjects and patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78(4):1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qing K, Ruppert K, Jiang Y, et al. Regional mapping of gas uptake by blood and tissue in the human lung using hyperpolarized xenon-129 MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;39(2):346–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JM, Robertson SH, Wang Z, et al. Using hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI to quantify regional gas transfer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2017. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Robertson SH, Wang J, et al. Quantitative analysis of hyperpolarized 129Xe gas transfer MRI. Med Phys. 2017;44(6):2415–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahhan T, Kaushik SS, He M, et al. Abnormalities in hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy in two patients with pulmonary vascular disease. Pulm Circ. 2016;6(1):126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruppert K, Altes TA, Mata JF, Ruset IC, Hersman FW, Mugler JPIII. Detecting pulmonary capillary blood pulsations using hyperpolarized xenon-129 chemical shift saturation recovery (CSSR) MR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(4):1771–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norquay G, Stewart NJ, Wild JM. Evaluation of 129Xe-RBC signal dynamics and chemical shift in the cardiopulmonary circuit using hyperpolarized 129Xe NMR. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. 2017;25:3327. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qing K, Mugler JP, Altes TA, et al. Assessment of lung function in asthma and COPD using hyperpolarized 129Xe chemical shift saturation recovery spectroscopy and dissolved-phase MRI. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(12):1490–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart NJ, Leung G, Norquay G, et al. Experimental validation of the hyperpolarized 129Xe chemical shift saturation recovery technique in healthy volunteers and subjects with interstitial lung disease. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74(1):196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Resp. Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He M, Robertson SH, Kaushik SS, et al. Dose and pulse sequence considerations for hyperpolarized 129Xe ventilation MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;33(7):877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle M, Chapman B, Balschi J, Pohost GSIFT. a postprocessing method that increases the signal-to-noise ratio of spectra which vary in time. J Magn Reson B. 1994;103(2):128–133. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowland B, Merugumala SK, Liao H, Creager MA, Balschi J, Lin AP. Spectral improvement by Fourier thresholding of in vivo dynamic spectroscopy data. Magn Reson Med. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall I, Higinbotham J, Bruce S, Freise A. Use of Voigt lineshape for quantification of in vivo 1H spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(5):651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertolina J, Durney C, Ailion D, Cutillo A, Morris A, Goodrich K. Experimental verification of inhomogeneous line-broadening calculations in lung models and other inhomogeneous structures. J Magn Reson. 1992;99(1):161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang YV MOXE. a model of gas exchange for hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance of the lung. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(3):884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen XJ, Möller HE, Chawla MS, et al. Spatially resolved measurements of hyperpolarized gas properties in the lung in vivo. Part I: diffusion coefficient. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42(4):721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajari AJ, Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Quirk JD, Conradi MS, Woods JC. Morphometric changes in the human pulmonary acinus during inflation. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(6):937–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glazier J, Hughes J, Maloney J, West J. Measurements of capillary dimensions and blood volume in rapidly frozen lungs. J Appl Physiol. 1969;26(1):65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsunoda S, Fukaya H, Sugihara T, Martin C, Hildebrandt J. Lung volume, thickness of alveolar walls and microscopic anisotropy of expansion. Respir Physiol. 1974;22(3):285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleveland ZI, Cofer GP, Metz G, et al. Hyperpolarized 129Xe MR imaging of alveolar gas uptake in humans. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossvoll O, Hatle LK. Pulmonary venous flow velocities recorded by transthoracic Doppler ultrasound: relation to left ventricular diastolic pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21(7):1687–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porra L, Broche L, Dégrugilliers L, et al. Synchrotron imaging shows effect of ventilator settings on intra-breath cyclic changes in pulmonary blood volume. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agustí AG, Roca J, Gea J, Wagner PD, Xaubet A, Rodriguez-Roisin R. Mechanisms of gas-exchange impairment in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(2):219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruppert K, Altes TA, Mata JF, Ruset IC, Hersman FW, Mugler JP. Detecting pulmonary capillary blood pulsations using hyperpolarized xenon-129 chemical shift saturation recovery (CSSR) MR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen R, Fan F-C, Kim S, Jan K, Usami S, Chien S. Tissue-blood partition coefficient for xenon: temperature and hematocrit dependence. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49(2):178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West JB. Respiratory Physiology: the Essentials. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. [Google Scholar]