Abstract

A series of physiological barriers have impeded nanoparticle-based drug formulations (NDFs) from reaching their targeted sites and achieving therapeutic outcomes. In this study, we develop size-controllable stealth doxorubicin-loaded nanodrug coated with CD47 peptides (DOX/sNDF-CD47) based on supramolecular chemistry to overcome multiple biological barriers. The smart DOX/sNDF-CD47 can efficiently decrease sequestration by macrophages and disassemble into poly(amidoamine) dendrimers with nuclear location sequences (DOX/PAMAM-NLS) in the presence of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2). Such structure transformation endows DOX/sNDF-CD47 with the ability of deep penetration in multicellular tumor spheroid, lysosomal escape, and nucleus location, resulting in excellent cytotoxicity and drug resistance combating. In vivo experiments further confirmed that DOX/sNDF-CD47 has good tumor-targeting ability and can significantly improves therapeutic efficacy of DOX on xenograft tumor model. The ability to overcome multiple biological barriers makes sNDF-CD47 a promising NDFs to treat cancer expressing MMP-2 and combating drug resistance.

Keywords: Nanocarrier, Drug delivery, Physiological barrier, Drug resistance, Self-assembly

Graphical Abstract

Smart nanodrug DOX/sNDF-CD47, prepared via supramolecular assembly, can efficiently decrease macrophages sequestration, and disassemble into smaller nanodrug in the presence of MMP-2. Such structural transformation makes it efficiently overcome various biobarriers and drug resistance. In vivo experiments further confirmed that DOX/sNDF-CD47 has good tumor-targeting ability and can significantly improve therapeutic efficacy of DOX on xenograft tumor model.

Based on prolonged circulation lifetime and enhanced accumulation of drug at the tumor site via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, nanoparticle-based drug formulations (NDFs) for cancer treatments can overcome pharmacokinetic limitations associated with conventional drug formulations, thereby improving the safety and tolerability of drugs.[1] However, by its remarkable abnormality, tumor microenvironment is replete with physiological barriers against NDFs, such as elevated interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) and dense interstitial matrix.[2] Such physiological barriers severely hinder the penetration and diffusion of NDFs in tumor.[3] In addition, opsonization and sequestration by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) is detrimental to long circulation of NDFs.[4a] The trapping of NDFs by endolysosomal organelles during internalization also restrict drug access to intracellular targets and cause premature degradation.[4] All these physiological barriers combine to cause the uneven distribution of drugs in tumor and expose cancer cells to sublethal concentration of therapeutic agents, thereby facilitating the development of drug resistance and limiting therapeutic outcomes.[5] Thus, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved NDFs like Doxil and Abraxane usually offer only marginal improvements to therapeutic efficacy.[6] To further improve therapeutic performance, various innovative design features have been continually explored and incorporated to overcome these barriers and enhance site-specific bioavailability of drugs.[7] Since large 100-nm nanoparticles are suitable for EPR effect, while small 10-nm nanoparticles are suitable for diffusion in tumor interstitium,[8] NDFs with the ability to transform their size in tumor when exposed to various stimuli, such as UV light and tumor acidic microenvironment, provide a kind of elegant strategy that enhances penetration and distribution of NDFs in tumor, in turn resulting in better therapeutic outcomes.[9]

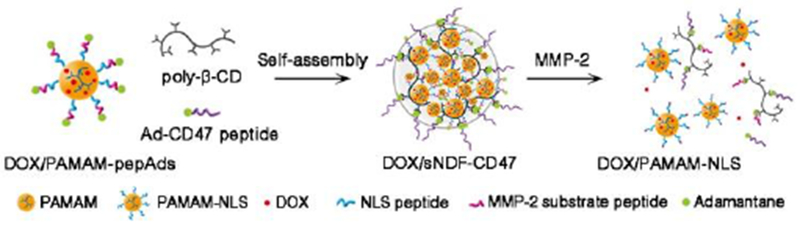

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-2, can degrade the components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and are key effectors of angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis.[10] MMP-2 usually express highly at tumor invasive edges and angiogenesis sites,[11] where NDFs possibly extravasate. Thus, MMP-2 provide a highly favorable trigger mechanism to construct NDFs with transformative ability in the tumor microenvironment. Herein, we report a size-controllable stealth nanodrug DOX/sNDF-CD47, which can disassemble into a small nanodrug with nuclear location sequences (DOX/PAMAM-NLS) in the presence of MMP-2, to overcome a series of physiological barriers (Scheme 1). DOX/sNDF-CD47 was constructed with three molecular modules via cyclodextrin (CD)/adamantine (Ad) recognition. The fifth generation PAMAM grafted with Ad-modified peptide consisting of NLS[12] and MMP-2 sensitive substrate[13] (Table S1) served as a DOX carrier module (DOX/PAMAM-pepAds). The peptide in this module could respond to MMP-2 and endow PAMAM with nucleus-targeting ability. To trace the carrier module, PAMAM was grafted with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or Cyanine 5 (Cy5) before conjugation with peptides to prepare fluorescent PAMAM-pepAds (fPAMAM-pepAds, Figure S1). Linear β-cyclodextrin polymer (poly-β-CD) served as a bridging module to hold PAMAM-pepAds together through CD/Ad recognition. Ad-modified CD47 ‘self’ peptide (Ad-CD47 peptide, Table S1) served as not only a capping module to constrain the continuous propagation of the cross-linked fPAMAM-pepAds/poly-β-CD hydrogel network (Figure S2), but also an ‘active stealth’ layer to inhibit phagocytic clearance.[14]

Scheme 1.

Schematic of the self-assembly of DOX/PAMAM-pepAds, poly-β-CD and Ad-CD47 peptide into stealth DOX/sNDF-CD47 and the disassembly of DOX/sNDF-CD47 into DOX/PAMAM-NLS in the presence of MMP-2 protease.

The mixing ratios of three modules could alter the propagation equilibrium of the fPAMAM-peptAds/Ad-CD47 hydrogel network, thereby facilitating adjustment of nanocarrier’s size.[15] Herein, the size of sNDF-CD47 was adjusted by changing the concentration of Ad-CD47 peptide. As shown in Figure S3, the size of sNDF-CD47 were changed from 200 nm to 50 nm when the mixing ratio of PAMAM-peptAds:poly-β-CD:Ad-CD47 peptide was changed from 5:3:9 to 5:3:15. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis also shows the tendency toward size reduction with the increase of Ad-CD47 peptide (Figure S4). In this study, the mixing ratio (5:3:12) of fPAMAM-peptAds:poly-β-CD:CD47 was chosen to prepare ~90-nm sNDF-CD47 because this size fares well in prolonged circulation and EPR effect.[8]

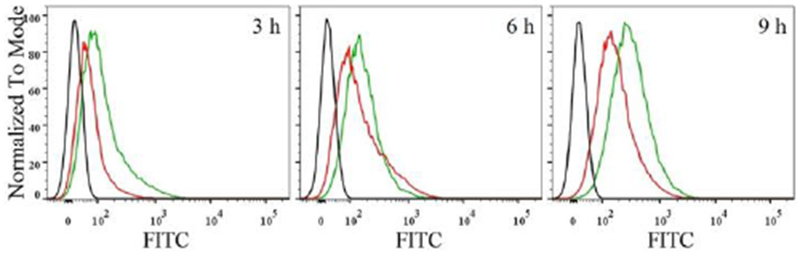

Nanoparticles usually undergo sequestration by macrophages during blood circulation, causing immune clearance of nanoparticles.[4a] Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is an FDA-approved polymer to reduce protein adsorption and immune clearance of nanoparticles.[16] Thus, the uptake of sNDF-CD47 in murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells pre-stimulated with 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 8 hours was analyzed and compared to the nanocarriers coated with PEG5000 (sNDF-PEG) or integrin αvβ3-targeting RGD peptides (sNDF-RGD, Table S1). As shown in Figure 1 and S5, sNDF-CD47 showed less endocytosis in RAW 264.7 cells than sNDF-PEG and sNDF-RGD at designed incubation time. These data indicate that the coating layer of CD47 peptide endows sNDF-CD47 with immunocompatibility, and decreases sequestration by macrophages, providing a stealth nanocarrier for drug delivery.

Figure 1.

Time-dependent endocytosis of sNDF-CD47 (red line) and sNDF-PEG (green line) in macrophage RAW 264.7 cells pre-stimulated with LPS. Black line represented the autofluorescence intensity of RAW 264.7 cells.

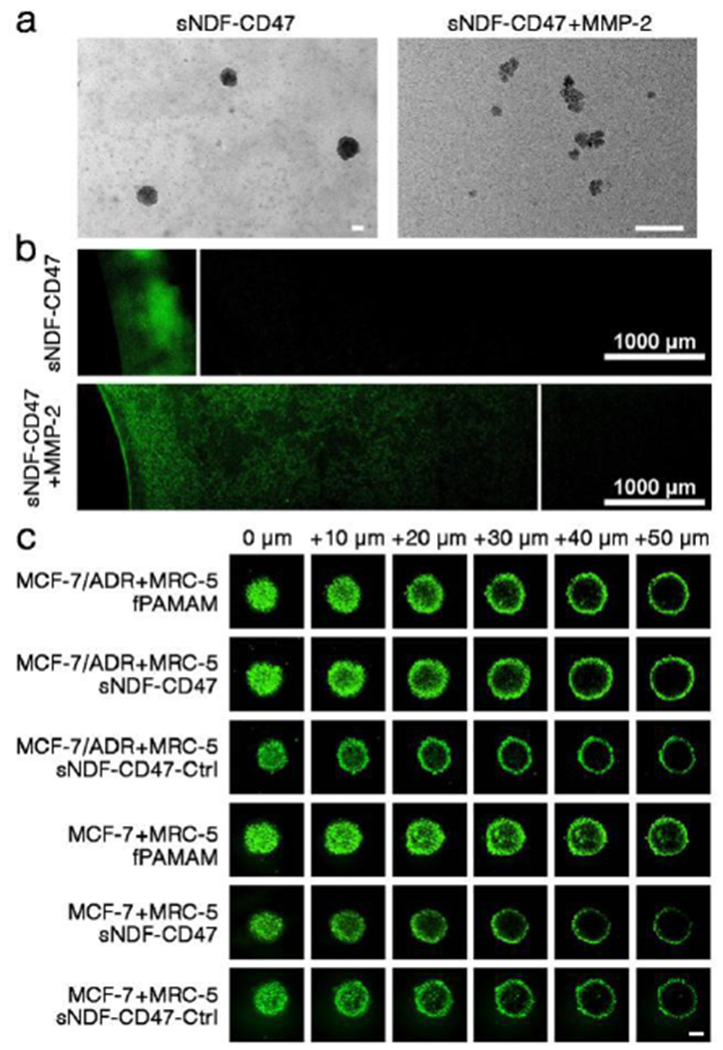

sNDF-CD47 could disassemble into PAMAM-NLS in the presence of exogenous MMP-2 (Scheme 1, Figure 2a and S6). The resulted PAMAM-NLS showed better penetration than the integral sNDF-CD47 in 0.74% rat tail collagen gel, a simulated interstitial matrix of tumor tissue, with a penetration depth of 4.2 mm vs. 0.8 mm (Figure 2b). To further investigate whether sNDF-CD47 could respond to endogenous MMP-2 and cause deep penetration in tumor condition, multicellular tumor spheroids (MCSs) were established via coculture of tumor associated fibroblast MRC-5 cells with either MCF-7 cells lowly expressing MMP-2 or MCF-7/ADR cells highly expressing MMP-2 (Figure S7),[17] and then the penetration of different nanocarriers in the MCSs was investigated by confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM). As shown in Figure 2c, sNDF-CD47, not MMP-2-insensitive sNDF-CD47-Ctrl (Table S1), penetrated deeply in MCF-7/ADR+MRC-5 MCSs as fPAMAM did. However, both sNDF-CD47 and sNDF-CD47-Ctrl presented weak penetration in MCF-7+MRC-5 MCSs compared to fPAMAM. The results confirmed that sNDF-CD47 could respond to endogenous MMP-2 and disassemble into PAMAM-NLS, resulting in deep penetration in MCF-7/ADR+MRC-5 MSCS. The MMP-2-responsive transformation ability made DOX/sNDF-CD-47 efficiently deliver cargos into the interior of MCF-7/ADR MSCs and A549 MSCs expressing high MMP-2 (Figure S7),[18] but not in MCF-7 MCSs compared to free DOX (Figure S8). Therefore, it is expected that DOX/sNDF-CD47 can result in uniform distribution of DOX in tumor expressing MMP-2 due to its deep penetration.

Figure 2.

(a) TEM images of sNDF-CD47 and the disassembled sNDF-CD47 treated with 250 μg MMP-2 protease for 12 h. Scale bars: 50 nm. (b) Penetration of sNDF-CD47 treated with or without MMP-2 in rat tail collagen gel (0.74%). (c) Penetration of FITC-labeled PAMAM, sNDF-CD47 and sNDF-CD47-Ctrl in MCSs after 4-h incubation. Scale bar: 100 μm.

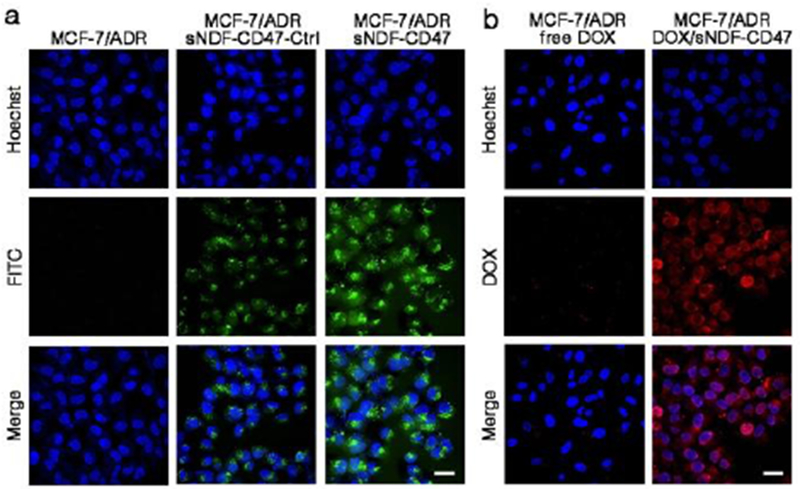

Next, cellular internalization of sNDF-CD47 was investigated in different cell lines by CLSM. As shown in Figure S9, MCF-7/ADR cells treated with sNDF-CD47 presented stronger fluorescence than those treated with sNDF-CD47-Ctrl, as well as MCF-7 cells treated with either sNDF-CD47 or sNDF-CD47-Ctrl. The data indicated that sNDF-CD47 can effectively enter MMP-2-expressing cancer cells. Studies of internalization pathway with various endocytosis inhibitors[19] (Figure S10) revealed that the internalization of the disassembled sNDF-CD47 in MCF-7/ADR cells mainly depended on micropinocytosis bypassing the recognition and capture of efflux proteins, thereby contributing to combating drug resistance.[20] The distribution of nanocarrier in MCF-7/ADR cells and A549 cells was further investigated by fluorescence colocalization analysis. As shown in Figure 3a and S11a, the green fluorescence of nanocarrier not only formed punctate pattern in cells, presumably owing to lysosomal accumulation, but also distributed in cell nucleus and overlapped with blue fluorescence of Hoechst 33258. The data suggest that sNDF-CD47 can efficiently overcome the biobarriors of cellular uptake and lysosomal trap, then enter nucleus of cells expressing MMP-2. Such appealing advantages make DOX/sNDF-CD47 efficiently decrease the exocytosis of DOX (Figure S12) and improve accumulation in nucleus of cancer cells (Figure S11b), and even drug-resistant cancer cells (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Intracellular distribution of sNDF-CD47 and sNDF-CD47-Ctrl in MCF/ADR. (b) Intracellular distribution of free DOX (250 nM) or equivalent DOX delivered by sNDF-CD47 in DOX-resistant MCF-7/ADR cells. Incubation time: 12 h. Blue: nuclei-staining Hoechst 33258. Scale bars: 30 μm.

The cytotoxicity of DOX/sNDF-CD47, free DOX and sNDF-CD47 was evaluated on MCF-7/ADR cells and MCF-7 cells using MTS assay. As shown in Figure 4, both DOX/sNDF-CD47 and free DOX exhibited high cytotoxicity on MCF-7 cells. Moreover, DOX/sNDF-CD47 had better antiproliferation efficacy than free DOX against DOX-resistant cancer cell MCF-7/ADR, with a growth inhibition of 75% vs. 40% at an equivalent DOX concentration of 10 μM. In addition, equivalent sNDF-CD47 had marginally cytotoxicity on both cell lines, demonstrating good biocompatibility (Figure S13). A soft-agar colony assay also confirmed that DOX/sNDF-CD47 could efficiently inhibit the colony growth of both MCF-7/ADR and MCF-7 cell lines (Figure S14). These results demonstrate that DOX/sNDF-CD47 can efficiently kill cancer cells and combat drug resistance. The enhanced antiproliferation activity of DOX/sNDF-CD47 against MCF-7/ADR cells could be attributed to the internalization pathway, decreased efflux, and nuclear localization of nanodrug.

Figure 4.

Antiproliferation of DOX/sNDF-CD47 (red line) and free DOX (blue line) against DOX-sensitive MCF-7 cells and DOX-resistant MCF-7/ADR cells after 48-h incubation. Values indicate mean ± SD (n =3).*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

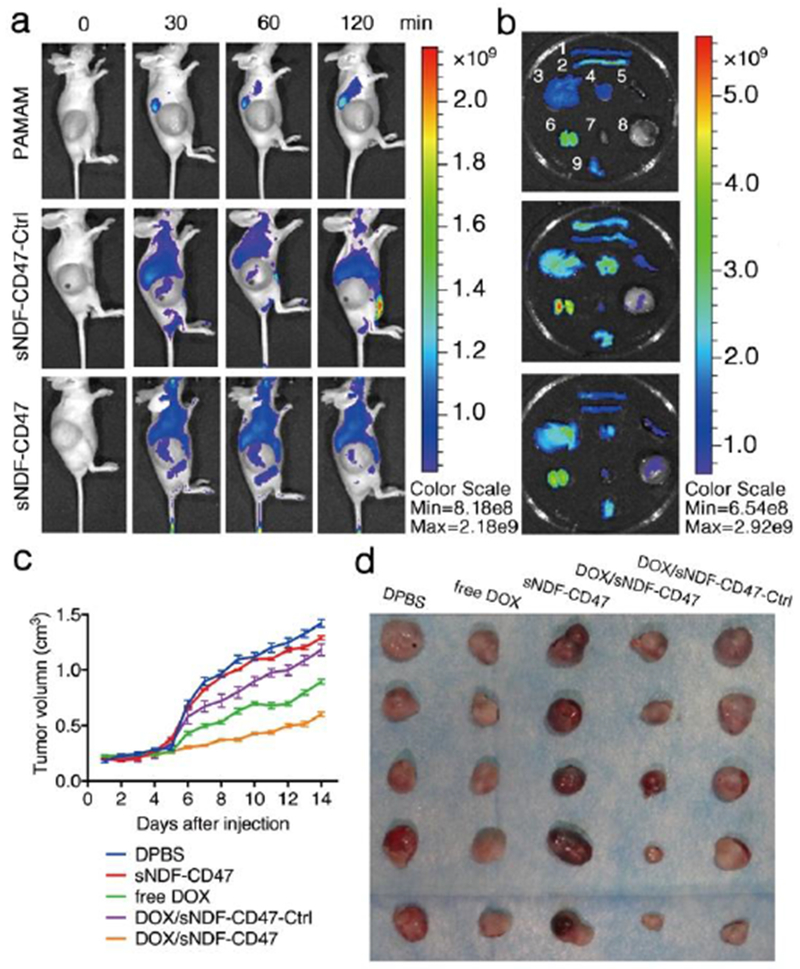

In vivo tumor-targeting ability of DOX/sNDF-CD47 in Balb/c nude mice bearing HT-1080 fibrosarcoma, which highly expresses MMP-2 (Figure S7), was investigated with fluorescence imaging after intravenous (i.v.) injection in tail and compared to Cy5-labeled PAMAM and sNDF-CD47-Ctrl. As displayed in Figure 5a, sNDF-CD47 had better accumulation in tumor, which could still be observed at 2 h post injection, compared to sNDF-CD47-Ctrl. PAMAM had negligible accumulation in tumor and was mainly cleared by kidney (Figure 5a). Ex vivo imaging of tumor and main organs also confirmed that sNDF-CD47 not only presented more accumulation in tumor, but also less accumulation in these organs than sNDF-CD47-Ctrl and fPAMAM (Figure 5b and S15). These results reveal that the sNDF-CD47 can efficiently accumulate in tumor and reduce the nonspecific distribution in healthy organs.

Figure 5.

(a) In vivo fluorescence imaging of HT-1080 tumor bearing Balb/c nude mice after i.v. injection of Cy5-labeled PAMAM, sNDF-CD47 and sNDF-CD47-Ctrl in tail, respectively. Monitoring the in vivo distribution by optical imaging at pre-injection, 30, 60, 120 min. (b) Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of tumors and major organs excised from the euthanized mice at 120 min post-injection. The numeric labelled for each organ was as follows: 1, large intestine; 2, small intestine; 3, liver; 4, lung; 5, spleen; 6, kidney; 7, heart; 8, tumor; 9, stomach. (c) Tumor growth inhibition by various treatments at DOX dosage of 1 mg/kg. (d) Tumor images excised from mice bearing HT-1080 tumors in each group of various treatments.

The antitumor activities of DOX/NDF-CD47 in HT1080 tumor bearing mice was then systematically investigated. Five groups of mice were daily treated with intratumoral injection of D-PBS, sNDF-CD47, free DOX, DOX/sNDF-CD47-Ctrl and DOX/sNDF-CD47, respectively. As shown in Figure 5c, 5d and S16, the tumors of each group treated with D-PBS or sNDF-CD47 sharply increased and reached ~1500 mm3 and ~1300 mm3 in size after 14-day treatment, respectively. The results suggest that sNDF-CD47 has marginally anticancer effect. The tumors of each group treated with free DOX, DOX/sNDF-CD47-Ctrl or DOX/sNDF-CD47 presented slow growth compared to those treated with D-PBS and sNDF-CD47. Among the three DOX formulations, DOX/sNDF-CD47 showed best anticancer effect, with tumor volume of ~600 mm3 after 14-day treatment. Owing to the poor penetration ability into tumor sites, DOX/sNDF-CD47-Ctrl showed lower therapeutic efficacy than free Dox. The weight of body and main organs, together with histological analysis further validated the efficient anticancer capability and biosafety of the DOX/sNDF-CD47 (Figure S17-S19).

In summary, a series of physiological barriers, such as opsonization and sequestration by MPS, elevated IFP and dense interstitial matrix, endolysosomal trapping and drug efflux pumps, severely hampered the achievement of optimal therapeutic outcomes. Importantly, these biobarriers are interconnective, making NDFs face complicated situation. Therefore, NDFs simply overcoming one individual barrier are not adequate to produce proper therapeutic outcomes. In this study, our DOX/sNDF-CD47 could disguise itself to achieve MPS avoidance, and adaptively respond to endogenous MMP-2 of tumor environment and sequentially overcome these biobarriers. MMP-2 usually expresses highly at tumor invasive edges and angiogenesis sites as a key effector of angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Therefore, the response to MMP-2 endows sNDF-CD47 with broad specificity and applicability in multiple tumor models for overcoming sequential biological barriers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NSFC grants (21521063, 21327009, 21405041, and 61527806), and by the US National Institutes of Health (GM079359 and CA133086), and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31701249), and by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and by the keypoint research and invention program of Hunan province (2017DK2011).

References

- [1].a) Matsumura Y, Maeda H, Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 6387–6392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K, J. Control. Release 2000, 65, 271–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R, Nat. Nanotechnol 2007, 2, 751–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Davis ME, Chen ZG, Chauhan DMVP, Jain RK, Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 958–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Peng Y, Zhao Z, Liu T, Li X, Hu X, Wei X, Zhang X, Tan W, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 10845–10849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Boucher Y, Baxter LT, Jain RK, Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 4478–4484 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2010, 7, 653–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jain RK, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 1999, 1, 241–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Heldin C-H, Rubin K, Pietras K, Ostman A, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Bartneck M, Keul HA, Zwadlo-Klarwasser G, Groll J, Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Martens TF, Remaut K, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, Braeckmans K, Nano Today 2014, 9, 344–364. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M, Nat. Biotechnol 2015, 33, 941–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, Shaw H, Desai N, Bhar P, Hawkins M, O’Shaughnessy J, J. Clin. Oncol 2005, 23, 7794–7803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) O’Brien MER, Wigler N, Inbar M, Rosso R, Grischke E, Santoro A, Catane R, Kieback DG, Tomczak P, Ackland SP, et al. , Ann. Oncol 2004, 15, 440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Sun T, Zhang YS, Pang B, Hyun DC, Yang M, Xia Y, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 12320–12364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhao Z, Meng H, Wang N, Donovan MJ, Fu T, You M, Chen Z, Zhang X, Tan W, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 7487–7491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cheng Y, Meyers JD, Broome A-M, Kenney ME, Basilion JP, Burda C, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 2583–2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ju C, Mo R, Xue J, Zhang L, Zhao Z, Xue L, Ping Q, Zhang C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 6253–6258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Jain RK, Science 2005, 307, 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2010, 7, 653–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wong C, Stylianopoulos T, Cui J, Martin J, Chauhan VP, Jiang W, Popovic Z, Jain RK, Bawendi MG, Fukumura D, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2426–2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Sunoqrot S, Bugno J, Lantvit D, Burdette JE, Hong S, J. Control. Release 2014, 191, 115–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tong R, Chiang HH, Kohane DS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19048–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Tong R, Hemmati HD, Langer R, Kohane DS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8848–8855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Li H, Du J, Du X, Xu C, Sun C, Wang H, Cao Z, Yang X, Zhu YH, Nie S, et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4164–4169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chen Q, Feng L, Liu J, Zhu W, Dong Z, Wu Y, Liu Z, Adv. Mater 2016, 28, 7129–7136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z, Cell 2010, 141, 52–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Packard BZ, Artym VV, Komoriya A, Yamada KM, Matrix Biol. 2009, 28, 3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rojiani MV, Alidina J, Esposito N, Rojiani AM, Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol 2010, 3, 775–781. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zanta MA, Belguise-Valladier P, Behr JP, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 91–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Netzel-Arnett S, Mallya SK, Nagase H, Birkedal-Hansen H, Van Wart HE, Anal. Biochem 1991, 195, 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rodriguez PL, Harada T, Christian DA, Pantano DA, Tsai RK, Discher DE, Science 2013, 339, 971–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang H, Wang S, Su H, Chen K-J, Armijo AL, Lin W-Y, Wang Y, Sun J, Kamei K-I, Czernin J, et al. , Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 4344–4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Beckerleg AM, Torchilin VP, Huang L, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1991, 1062, 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li Q, Wang W, Xu J, Cao X, Chen Q, Yang J, Xu Z, Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 1767–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lin S, Lai K, Hsu S, Yang J, Kuo C, Lin J, Ma Y, Wu C, Chung J, Cancer Lett. 2009, 285, 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hillaireau H, Couvreur P, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2009, 66, 2873–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wei T, Chen C, Liu J, Liu C, Posocco P, Liu X, Cheng Q, Huo S, Liang Z, Fermeglia M, et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2978–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.