Abstract.

Isolated renal mucormycosis in immunocompetent hosts is a rare entity. We present the largest case series of isolated renal mucormycosis in immunocompetent hosts. Retrospective data of isolated renal mucormycosis from March 2012 to June 2017 was reviewed. Fifteen patients of isolated renal mucormycosis were identified. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showed enlarged globular kidneys with decreased or patchy enhancement, perinephric stranding and thickened Gerota’s fascia in all patients. Ten patients with unilateral involvement underwent nephrectomy and two of four patients with bilateral renal mucormycosis underwent bilateral nephrectomy. Two patients were managed with intravenous antifungal therapy alone. Overall, the mortality rate in our series was 40% (6/15). Isolated renal mucormycosis in healthy immunocompetent hosts is an emerging new entity. Prompt diagnosis based on the characteristic clinical and radiological picture and starting high-dose antifungal therapy at least 24 hours before surgical debridement offer the best chance of survival in these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Renal mucormycosis is commonly seen as a part of disseminated mucormycosis. Isolated renal involvement is rare and available in the literature as case reports.1–4 This infection is seen commonly in immunocompromised hosts such as allograft recipients, HIV patients, patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, patients with malignancy and intravenous (IV) drug abusers.5

Incidence of renal mucormycosis in immunocompetent hosts is very low.6 Earlier 11 such cases were reported from our institute by Chakrabarti et al.7 over a period of 10 years. They emphasized that the outcome of renal mucormycosis is worst as all patients succumbed to illness. Gupta et al.8 reported a mortality rate of around 77% in cases of isolated renal mucormycosis. We report 15 cases of isolated renal mucormycosis in immunocompetent hosts being managed for the last 5 years with improved outcomes. In this article, we present the clinical profile, management and outcome of these cases.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Retrospective data of isolated renal mucormycosis documented on histopathology (operative specimen/fine needle aspiration cytology [FNAC]/biopsy) were reviewed from the hospital records during March 2012 to June 2017. Operative specimens were received in the department of histopathology in 10% formalin. Sections were taken properly after extensive examination of the gross specimen. Subsequently, the sections were processed and examined under a microscope with routine H&E staining [Harry’s hematoxylin made from Hematoxylin Krist (Merck K GaA), Germany(Colour Index 75290); Eosin Y (Merck K GaA), Germany (Colour Index 45380)]. Special stainings periodic acid-schiff (PAS) were performed on proper sections for better characterization of the fungus (Figure 1). For evaluation of immunocompromised status, a detailed history regarding IV drug abuse, malignancy, immunosuppressive drug intake, diabetes, and screening for HIV was obtained. Patients with immunocompromised status were subsequently excluded. The preoperative diagnosis of renal mucormycosis was based on the characteristic clinical presentation of nonresolving pyelonephritis and radiological findings with or without biopsy/FNAC (Table 1). Before 2012, suspected cases of renal mucormycosis underwent emergency nephrectomy and antifugal therapy was started in the postoperative period. During the study period, the changed management protocol included emergency nephrectomy based on clinical and radiological suspicion irrespective of the tissue confirmation of mucormycosis and initiation of IV liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day) at least 24 hours before surgical intervention. Amphotericin B was then continued along with supportive care in the postoperative period to a total cumulative dose of 3–4 g in all patients and clinical improvement was noted in terms of absence of fever and normalization of total leukocyte counts. Clinical, radiological, operative and outcome data of all these patients during the study period were compiled and analyzed.

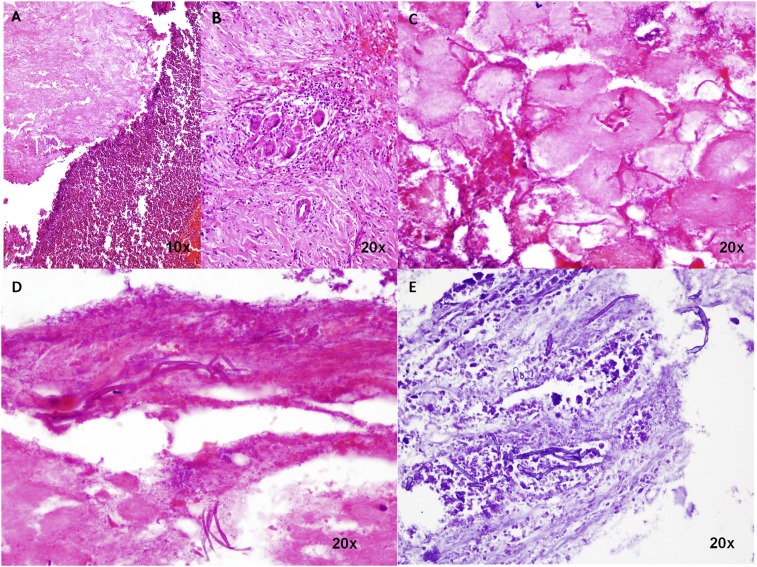

Figure 1.

(A) Large areas of bland necrosis and area of inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and polymorphs (10×). (B) Scattered multinucleated giant cells in a background of fibrosis (20×). (C) Scattered fungal hyphae seen in the background of bland necrosis (20×). (D) Fungal hyphae are aseptate, show right-angled branching and have a thick cell wall in a background of bland necrosis. (E) PAS stain showing fungal hyphae with right-angled branching, devoid of septa, thick cell membrane and typical foldable appearance. Histomorphologically highly suggestive of mucormycosis. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Table 1.

Clinical profile of 15 patients of isolated renal mucormycosis in immunocompetent hosts

| Sr. No. | Age (years)/gender | Clinical presentation | Symptom duration (days) | Total leukocyte count (mm3) | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | Renal involvement | Preoperative diagnosis based on | Surgery | Adjunctive procedure | Outcome | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 40/Male | Flank pain and fever | 38 | 18,200 | 1.37 | Unilateral | Biopsy and radiology finding | Open biopsy | – | Alive | 35 |

| Case 2 | 28/Male | Flank pain and fever | 14 | 35,200 | 1.17 | Unilateral | Radiology finding | Left nephrectomy | Splenectomy and colostomy | Alive | 22 |

| Case 3 | 50/Male | Flank pain and fever | 16 | 38,900 | 3.1 | Unilateral | Radiology finding | Right nephrectomy | – | Alive | 28 |

| Case 4 | 42/Male | Flank pain and fever | 23 | 27,600 | 1.2 | Unilateral | Radiology finding | Right nephrectomy | – | Alive | 47 |

| Case 5 | 35/Male | Flank pain, fever, and oliguria | 15 | 33,800 | 1.5 | Unilateral | Radiology finding | Left nephrectomy | Splenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, and hemicolectomy | Dead | |

| Case 6 | 35/Male | Flank pain and fever | 19 | 34,400 | 1.3 | Unilateral | Radiology finding | Left nephrectomy | Splenectomy, segmental colectomy, and transverse colostomy | Alive | 19 |

| Case 7 | 38/Male | Flank pain and fever | 37 | 23,900 | 1.1 | Unilateral | FNAC and radiology finding | Right nephrectomy | – | Alive | 33 |

| Case 8 | 16/Male | Flank pain, fever, loose motions, and vomiting | 33 | 36,500 | 1.3 | Unilateral | FNAC and radiology finding | Right nephrectomy | – | Alive | 10 |

| Case 9 | 40/Male | Flank pain and fever | 10 | – | – | Unilateral | Biopsy and radiology finding | Left nephrectomy | – | Alive | 10 |

| Case 10 | 48/Male | Flank pain, fever, oliguria, and breathlessness | 13 | 35,200 | 1.1 | Unilateral | Radiology finding | Left nephrectomy | – | Dead | – |

| Case 11 | 30/Female | Flank pain and fever | 8 | 60,700 | 1.4 | Unilateral | Radiology finding | Left nephrectomy | Splenectomy, segmental colectomy, and transverse colostomy | Dead | – |

| Case 12 | 28/Male | Flank pain, fever, and oliguria | 26 | 16,600 | 9.7 | Bilateral | Radiology finding | Bilateral nephrectomy | Ileostomy | Dead | – |

| Case 13 | 35/Male | Flank pain, fever, and oliguria | 46 | 25,400 | 13 | Bilateral | FNAC and radiology finding | B/L nephrectomy | – | Dead | – |

| Case 14 | 25/Female | Flank pain, fever, and oliguria | 88 | 18,700 | 9.6 | Bilateral | Radiology finding | Open drainage if bilateral renal abscess | Ileostomy | Dead | – |

| Case 15 | 49/Male | Flank pain, fever, and dysuria | 98 | 15,400 | 2.5 | Bilateral | Radiology finding | Left nephrectomy | – | Alive | 08 |

RESULTS

Ours is a tertiary care center with an annual admission rate of 75,000 patients. The department of urology has an admission rate of 2,500 per annum. During the study period, the total number of admissions in our department is approximately 13,000. Of this, 17 patients of renal mucormycosis were identified. One patient with cutaneous and bilateral renal mucormycosis and another with a history of type II diabetes mellitus as risk factor were excluded. Data of 15 patients with isolated renal mucormycosis without any known immunocompromising condition were analyzed (Table 1). Thirteen patients were males (86.66%) and two were females, and the mean age was 35.93 years (16–50 years). Sixty-six percent of patients (10/15) were clustered from Punjab, which is considered a major agricultural belt in northern India. Eleven patients (73.33%) presented during rainy and autumn seasons.

All patients were on IV antibiotics with a diagnosis of bacterial pyelonephritis before being referred to us. The median duration of illness was 23 days (IQR 13.25–37.75 days) before diagnosis or referral. In 11 cases, there was unilateral involvement and in four cases it was bilateral. Severe flank pain and unrelenting fever had been the common presentation. Three of four patients with bilateral involvement had oliguria and elevated serum creatinine at presentation. Leukocytosis (mean total leukocyte count 28,033/mm3, IQR 18, 325–35, 200/mm3) was documented in all patients. Mean serum creatinine was higher in patients with bilateral renal involvement than in those with unilateral involvement (8.7 mg/dL versus 2.51 mg/dL).

All patients had undergone contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of abdomen based on clinical suspicion of mucormycosis (severe flank tenderness, subcutaneous edema/crepitus and persistent fever not responding to antibiotics). The characteristic findings on CECT seen in all patients were diffuse or patchy areas of absent or attenuated contrast enhancement with thickened Gerota’s fascia and perinephric fat stranding. Bulky psoas muscle, presence of renal abscess or perinephric collection and reactive pleural effusion were other associated findings seen on imaging (Table 2 and Figure 2). Patchy/decreased enhancement in the adjacent organs such as the spleen, colon, and pancreas (suggesting involvement by the disease) was seen in four patients. Preoperative FNAC/biopsy was performed in six of 15 patients, of whom five revealed mucormycosis (Table 1). Urine for bacterial culture and fungal smear and culture were negative in all (available in 12 patients).

Table 2.

Contrast-enhanced computer tomography scan of abdomen findings of renal mucormycosis

| CECT Finding | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | Case 10 | Case 11 | Case 12 | Case 13 | Case 14 | Case 15 | Prevalence (% ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enlarged globular kidney with patchy/decreased /absent enhancement | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100% |

| 2. Perinephric fat stranding | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | + | + | + | 100% |

| 3. Thickened Gerota’s fascia | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | 100% |

| 4. Bulky psoas muscle | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | − | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | − | − | + | 66.6% |

| 5. Renal abscess | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | NA | − | − | NA | + | + | + | 46.1% |

| 6. Perinephric collection | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | NA | − | − | NA | + | + | − | 30.7% |

| 7. Reactive pleural effusion | + | + | NA | NA | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | 84.6% |

CECT = contrast-enhanced computer tomography; NA = not available.

Figure 2.

Characteristic contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan findings showing completely nonenhancing right kidney with perinephric fat stranding (arrow) in A, patchy area of decreased enhancement in the right kidney (arrow) in B, thickened Gerota’s fascia in C (arrow), and bulky psoas muscle in D (arrow). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Ten of 11 patients with unilateral involvement (except case 1) underwent emergency nephrectomy. In case 1, nephrectomy could not be performed and only open biopsy was performed because of extensive perinephric inflammation and adhesions with inferior vena cava. He was subsequently managed with a full course of IV amphotericin B and percutaneous drainage.

Two of four patients with bilateral renal mucormycosis underwent bilateral nephrectomy with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis catheter placement. One patient with bilateral involvement underwent unilateral nephrectomy and the other kidney was salvaged with IV amphotericin B (case 15). The fourth patient (case 14) had bilateral mucormycosis masquerading as renal abscess. Repeated FNACs did not reveal the fungus. She underwent open drainage of abscesses initially but later developed colonic fistula and necrotizing fasciitis. She was reexplored and subsequently she succumbed to the illness. Final biopsy from the necrotic renal tissue and parietal wall muscle tissue revealed mucormycosis.

The disease extended beyond the kidney in six (two in bilateral and four in unilateral) patients. Four patients required segmental colectomy, splenectomy and/or distal pancreatectomy in addition to nephrectomy. Two patients (cases 12 and 14) needed temporary diversion ileostomy.

Data regarding fungal isolation from the operated specimen were available in only four patients; among these, the organism was isolated in culture in only one patient and the isolated fungus was found to be Rhizopus arrhizus. The culture on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar showed dense white cottony growth initially, which turned gray with sporulation. The microscopic finding was used to characterize the genus Rhizopus by the presence of nodal rhizoids with globose sporangia. Sporangiospores were oval with striae. Furthermore, internal transcribed spacer gene sequencing was performed for species-level confirmation, which revealed 99% similarity with reference R. arrhizus isolates. The median hospital stay was 23 days (range 15–75 days). The overall mortality rate in our series was 40% (6/15). The mortality rate for unilateral renal involvement was 27.2% (3/11). The mortality rate for bilateral involvement was 75% (3/4). The median interval from diagnosis until death was 9.5 days (range 2–41 days). The median follow-up of surviving patients was 20.5 months (range 7–48 months).

DISCUSSION

Mucormycosis is a fulminant fungal infection caused by the order mucorales. These angioinvasive fungi are characterized histologically by straight aseptate branched hyphae. Renal involvement as a part of multi-organ disease is seen in immunocompromised hosts. However, cases of isolated renal mucormycosis occurring in individuals without obvious immunosuppression are rare and are mostly reported from India and China.9 Mignogna et al.10 published 18 such cases over a period of 30 years. However, in our series, we found 15 such cases in just 5 years, suggesting that increased detection by the improved diagnostic modality or the incidence of this disease entity may be on a rise.

The clustering of cases in our series from a particular region and during rainy and autumn seasons suggests that crop harvesting with a conducive humid environment during these seasons might be favoring the growth of fungus. However, a proper epidemiological study may prove this co-occurrence. Mucormycosis usually has equal gender distribution and can occur in any age group; however, in our series, most of our patients (86.66%) are young healthy males, with a mean age of 35.93 years.10 Male preponderance could be attributed to higher exposure to agricultural outdoor activity.

Flank pain and persistent fever for several days have been the common presentation of renal mucormycosis. Patients with bilateral involvement often present with oliguria.11 On examination, severe tenderness, sometimes even with erythema and pitting edema in the flank region, may be noticed. This is due to intense inflammation of the kidney extending to the perinephric and parietal wall. All these cases are initially treated as bacterial pyelonephritis before seeking specialty opinion. Failure to respond to IV antibiotics warrants further investigation with CECT abdomen even in patients with increased serum creatinine levels.12,13

Clinical indicators such as unrelenting fever not responding to antibiotics, presence of severe flank tenderness and sterile pyuria associated with characteristic CECT findings (diffuse or patchy areas of absent or attenuated contrast enhancement, perinephric fat stranding and thickened Gerota’s fascia) as seen in our series are strong pointers toward mucormycosis. In such situations, the need for a preoperative tissue diagnosis may be redundant. Data regarding fungal isolation from operated specimen were available in only four patients; among these, the organism was isolated in culture in only one patient, and the isolated fungus was found to be R. arrhizus. The European Confederation of Medical Mycology and European Conference on Infections in Leukemia recommend amphotericin B lipid formulation in combination with surgery and modification of risk factors as the treatment of choice for mucormycosis.14 Aggressive surgical debridement in the form of nephrectomy with or without resection of surrounding involved organs such as the bowel and spleen should be carried out. The overall mortality rate in our series is 40%, which is significantly less than that in the previous published literature (around 70%).8 We believe that one of the factors of the improved outcome could be early institution of IV liposomal amphotericin B at least 24 hours before emergency nephrectomy and continuing the same during the perioperative period. This protocol ensured high serum levels of antifungal medication during surgery and it counteracts the possible fungemia occurring during intraoperative handling of the involved kidney, leading to an improved outcome.

Selected cases of renal mucormycosis managed with IV antifungal therapy alone have been reported.15 Such an approach can be followed with extreme caution only in highly selected patients such as those with patchy renal involvement and those with solitary kidney where biopsy/FNAC revealed fungus. However, these patients should be actively monitored and considered for urgent nephrectomy in the event of clinical deterioration (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Algorithm for the management of suspected renal mucormycosis.

One limitation of our study is that the diagnosis of mucormycosis was based solely on histopatology and was not confirmed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture (except in one case).

CONCLUSION

Isolated renal mucormycosis can occur not only in patients with an immunosuppressive state but also in healthy immunocompetent hosts. Prompt diagnosis based on the characteristic clinical and radiological picture and starting high-dose antifungal therapy at least 24 hours before surgical debridement offer the best chance of survival in these patients.

Acknowledgments:

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh AK, Goel MM, Gupta C, Kumar S, 2014. Isolated renal zygomycosis in an immunocompetent patient. BMJ Case Reports 2014: bcr2013200060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhaliwal HS, et al. 2015Diagnosed only if considered: isolated renal mucormycosis. Lancet 385: 2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickles R, Long G, Murugasu R, 1994. Isolated renal mucormycosis. Med Journal Aust 160: 514–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogenes V, Vick S, Pultizer DR, 1998. Isolated renal mucormycosis. Infect Urol 113: 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta KL, Joshi K, Kohli HS, Jha V, Sakhuja V, 2012. Mucormycosis (zygomycosis) of renal allograft. Nephrol Dial Transplant Plus 5: 502–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pahwa M, Pahwa AR, Girotra M, Chawla A, 2013. Isolated renal mucormycosis in a healthy immunocompetent patient: atypical presentation and course. Korean J Urol 54: 641–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakrabarti A, Das A, Sharma A, Panda N, Das S, Gupta KL, Sakhuja V, 2001. Ten years experience in zygomycosis at a tertiary care centre in India. J Infect 42: 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta KL, Radotra BD, Sakhuja V, Banerjee AK, Chugh KS, 1989. Mucormycosis in patients with renal failure. Ren Fail 11: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakrabarti A, Dhaliwal M, 2013. Epidemiology of mucormycosis in India. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 7: 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mignogna MD, Fortuna G, Leuci S, Adamo D, Ruoppo E, Siano M, Mariani U, 2011. Mucormycosis in immunocompetent patients: a case-series of patients with maxillary sinus involvement and a critical review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis 15: e533–e540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta KL, Joshi K, Sud K, Kohli HS, Jha V, Radotra BD, Sakhuja V, 1999. Renal zygomycosis: an under-diagnosed cause of acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 2720–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chugh KS, Sakhuja V, Gupta KL, Jha V, Chakravarty A, Malik N, Kathuria P, Pahwa N, Kalra OP, 1993. Renal mucormycosis: computerized tomographic findings and their diagnostic significance. Am J Kidney Dis 22: 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paonam S, Bag S, Mavuduru RS, Agarwal MM, Mandal AK, 2014. Isolated bilateral renal mucormycosis masquerading as renal abscess in an immunocompetent individual: a lesson learnt. Case Rep Urol 2014: 304380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornely OA, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Fungal Infection Study Group; European Confederation of Medical Mycology , 2014. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect 20: 5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devana SK, Bora GS, Mavuduru RS, Panwar P, Kakkar N, Mandal AK, 2016. Successful management of renal mucormycosis with antifungal therapy and drainage. Indian J Urol 32: 154–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]