Abstract.

The incidence of murine typhus in Israel has decreased substantially since 1950 to a low of 0.04/100,000 population in 2010. We present the experience of a single university medical center in central Israel. Hospitalized patients serologically positive for Rickettsia typhi by indirect immunofluorescence antibody assay during 2006–2016 were retrospectively identified. Clinical and laboratory data from patients’ charts were used to analyze disease trends and distribution. Seventy-eight patients were studied (mean age: 27.9 years), mostly of Arab ethnicity (68, 87.2%). Seventy-one (91%) patients resided in two large mixed Jewish-Arab cities—Lod and Ramla. The incidence of murine typhus among the Arab population in Lod increased 8.4-fold from 6.4/100,000 in 2006 to a peak of 53.4/100,000 in 2013. The average annual incidence among Arabs in Ramla was 10.1/100,000. Among Jews, incidences were 0.8/100,000 in Lod and 0.4/100,000 in Ramla. The classical triad of fever, headache, and rash was noted in 20.8% patients. Substantial morbidity included prolonged fever before hospitalization and hospital stay (mean of 8.4 and 5.1 days, respectively), and severe complications in six patients, including pneumonitis in three patients, and splenic infarctions, pericardial effusion, and retinitis, each in one. One previously healthy patient died of multiorgan failure. The study describes a high incidence of murine typhus with a recent upsurge in an urban setting in central Israel. High morbidity and a single fatal outcome challenge the concept of murine typhus being a mild disease. The study calls for better rodent control and sanitation measures in the affected neighborhoods.

INTRODUCTION

Murine typhus is a member of the typhus group of rickettsial diseases, with worldwide distribution, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. Poor public health and sanitation measures provide ideal conditions for the transmission of murine typhus. In addition, clearing of land for urban development and construction enables rodent populations to increase and exposes humans to the zoonotic life cycle, thus leading to increasing seroprevalence observed in some of the rapidly developing countries.1,2 Murine typhus is a zoonotic disease caused by Rickettsia typhi (mooseri) and transmitted by fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) that dwell on rats (Rattus spp.), which serve as reservoir.3 Both the vector and the reservoir animals are prevalent in Israel.4 Recently, other animal–flea cycles were indicated in disease transmission, including cats, dogs, and opossums, and their fleas.5

Murine typhus is usually a mild disease, especially in children, and is characterized by nonspecific signs such as fever, headache, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting. Macular or maculopapular rash, involving mainly the torso and less often the extremities, is present in less than 20% of the patients initially but may develop during the course of infection in up to 80%.6 A spectrum of severe manifestations has been described, particularly in hospitalized patients, but mortality is rare.7,8

Laboratory diagnosis is based on sensitive serologic tests, such as indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) assays. Diagnostic titer is present in about half of the patients within the first week of infection, and in most patients within the second week. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of peripheral blood or of skin biopsy samples and immunohistochemical stain of tissues are considered as confirmatory tests.9,10 Because serologic diagnosis may be delayed, antibiotic treatment should preferably be initiated on clinical suspicion. Doxycycline is the preferred treatment. Alternative treatments to be considered include quinolones, chloramphenicol, and possibly azithromycin.11,12

Murine typhus was prevalent in Israel before the 1950s. According to a recent publication on reportable diseases in Israel, disease incidence decreased substantially since 1950 from more than 59.9 cases/100,000 to 0.04 cases/100,000 in 2010. Indeed, in 2010, only three cases were reported to the Department of Epidemiology.13 The most recent epidemiological study from the years 1991–2001 estimated the disease incidence in Israel at 0.65 cases/100,000 population, with a higher incidence of 1.85 cases/100,000 population among the population of Arab ethnicity.14

Over the last decade, we have witnessed an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with murine typhus admitted to our medical center, which is located in central Israel. The aim of our study was to delineate the local epidemiology and clinical characteristics of a large cohort of hospitalized patients with murine typhus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Assaf Harofeh Medical Center (AHMC) is an 850-bed university hospital serving a mostly urban population of about 750,000 from central and southern Israel. Results of murine typhus serologic studies were derived from the microbiology laboratory computerized database. Serologic tests for R. typhi were ordered by the treating physicians for clinically suspected cases at their discretion. Immunofluorescence assay was performed using murine typhus antigen slides from Life Science Research Israel, Ness Ziona, Israel. All consecutive hospitalized patients with a single IgM titer of ≥ 1:100 during the years 2006–2016 were included. Clinical and demographic data were retrieved from the patients’ hospital charts. To compare the clinical presentations of children and adults, we performed bivariate analyses using the Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, and a P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses.

Patients’ street addresses were used for geocoding and the ArcGIS software version 10 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA) was used for visual presentation. A layer with statistical areas and their characteristics according to most recent census of 2008 was retrieved from the Israeli Bureau of Statistics. Incidence rates for the study period were calculated by dividing the number of infection episodes by the population size retrieved from the Israeli Bureau of Statistics (http://www.cbs.gov.il/ishuvim/ishuvim_main.htm, last accessed January 15, 2018).

The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee at AHMC, and measures were taken to maintain patients’ confidentiality.

RESULTS

Epidemiology and study population.

From January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2016, a total of 79 patients with positive serology for murine typhus were retrieved from the Microbiology Laboratory records. One patient was excluded because of an alternative diagnosis that was judged responsible for his symptoms. In addition to a single positive IgM titer for R. typhi, in two patients, seroconversion to positive IgG was also documented. In a single patient, blood and biopsy samples from the skin rash were submitted to the Israel Institute for Biological Research, Ness Ziona, Israel, where PCR was positive for murine typhus. In all patients, concomitant serologic tests for Rickettsia conorii and Coxiella burnetii were negative.

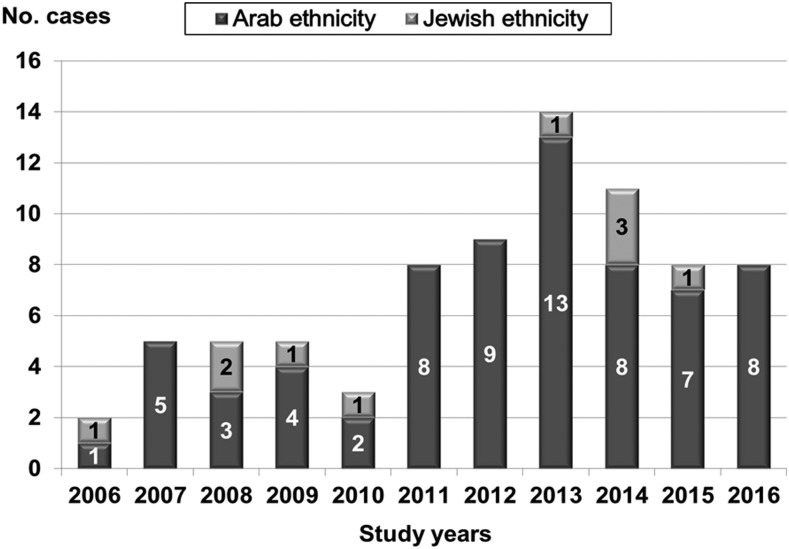

Forty-six (59.0%) patients were males, and the mean age was 27.9 years (median 20.5, range 1–76 years). Thirty-two patients (39.7%) were less than 18 years old and three were older than 65 years (Figure 1). Sixty-eight patients (87.2%) were of Arab ethnicity and 10 (12.8%) of Jewish ethnicity. Along the study years, a sharp increase in the number of cases was noted since 2011 (Figure 2). The majority of cases (74.4%) occurred during the warm months of the year, from July to October.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of 78 patients with murine typhus.

Figure 2.

Annual number of cases admitted to Assaf Harofeh Medical Center and diagnosed with murine typhus according to ethnicity.

Seventy-one (91.0%) patients resided in two cities with mixed Jewish-Arab population within the capture area of AHMC, namely Lod (52 patients) and Ramla (20 patients). Four additional patients resided in three large cities within the capture area of AHMC and two were referrals from the north and south parts of the country.

During the study years, the Arab population in Lod increased from 15,700 in 2006 to 22,100 in 2016 and in Ramla from 14,200 to 17,300. The Jewish population decreased in Lod from 51,000 to 45,700 and increased in Ramla from 47,900 to 54,200. The incidence of hospitalized cases among the Arab population residing in Lod increased from 6.4 cases/100,000 population in 2006 to a peak of 53.4 cases/100,000 in 2013 and then slightly declined to 27.1 cases/100,000 in 2016. The average incidence of hospitalized cases residing in Ramla among the Arab population was 10.2 cases/100,000, with no distinct trends. Among the Jewish population, the corresponding average incidence was 0.8/100,000 in Lod and 0.4/100,000 in Ramla. Most of the cases clustered in the Arab neighborhoods in Lod and Ramla, with some spillage into the nearby Jewish neighborhoods (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of 68 cases of Rickettsia typhi in the cities of Lod and Ramla according to statistical areas. Statistical areas with a majority of Jewish population (Jewish STAT [statistical area]) are marked in blue and statistical areas with a majority of Arab population are marked in red (Arab STAT). AHMC = Assaf Harofeh Medical Center.

Clinical course.

The characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 1. Forty-one (52.6%) patients were hospitalized in the Medicine ward, 31 (39.7%) in the Pediatric ward, and a single patient, each, in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), the Obstetrics, and the Ophthalmology departments. Three pediatric patients were discharged from the emergency room and followed in the outpatient clinic. The mean duration of illness before hospitalization was 8.4 days (median: 7 days, range: 1–30 days). The majority of the patients were previously healthy, and only 10 (12.8%) had one or more comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus (four patients, 5.1%), morbid obesity (three, 3.8%), hypertension (two, 2.1%), ischemic heart disease (two, 2.1%), and one, each: cirrhosis, chronic lung disease, asthma, congestive heart disease, and pregnancy. The patients with comorbidities were older than the rest of the group (average age 48.4 years).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics in the current and prior cohorts from Israel

| Patients characteristics | Current cohort, N = 78 | Rosenthal et al.,21 N = 100 | Shaked et al.,22 N = 45 | Shalev et al.,15 N = 76 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study period | 2006–2016 | 1969–1972 | 1975–1986 | 2003–2005 |

| Mean age, years (range) | 27.9 (1–76) | – | – | 7.3 (4.5–10.1) |

| Male gender, no (%) | 46/78 (59) | 68/100 (68) | 34/45 (75) | 39/76 (51) |

| No. hospitalized (%) | 75/78 (96) | 100/100 (100) | 45/45 (100) | 1/76 (1.3) |

| Arab ethnicity, no. (%) | 68/78 (87.2) | – | – | – |

| Symptoms at presentation, no. (%) | ||||

| Fever | 77/77 (100) | 100/100 (100) | 45/45 (100) | 76/76 (100) |

| Headache | 46/77 (59.7) | 39/100 (38)* | 34/45 (76) | – |

| Rash | 23/77 (29.9) | 55/100 (55) | 27/45 (60) | 5 (6.6) |

| Petechial rash | 1/77 (1.3) | – | – | – |

| Arthralgia | 4/77 (5.2) | – | – | – |

| Myalgia | 25/77 (32.4) | – | – | – |

| Vomiting | 29/77 (37.7) | – | – | – |

| Laboratory workup, no. (%) | ||||

| Anemia | 37/78 (47.4) | – | – | 52/76 (68.4) |

| Leukopenia | 7/78 (9) | – | 0/42 (0) | 14/76 (18.4) |

| Lymphopenia | 23/78 (29.5) | 25/100 (25.0) | – | – |

| Thrombocytopenia | 32/78 (41) | – | 20/21 (95) | 5/76 (6.6) |

| Elevated aspartate aminotransferase levels | 58/78 (74,3) | – | 35/40 (87) | – |

| Elevated alanine transaminase levels | 35/78 (44,9) | – | – | – |

| Elevated alkaline phosphatase levels | 31/78 (39.7) | – | 9/40 (22) | – |

| Elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels | 62/68 (91.1) | – | – | 39/76 (51.3) |

| Hyponatremia | 44/78 (56.4) | – | 5/40 (12) | 15/76 (19.7) |

| Elevated creatinine levels | 4/77 (5.2) | – | – | – |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 26/63 (43.3) | – | – | 1/76 (1.3) |

| Elevated CRP | 71/74 (95.9) | – | – | – |

– Denotes unavailable data.

* Severe headache only.

All patients presented with fever. Headache was reported by 59.7% of the patients and rash was found in 29.9%. The rash was described mostly as maculopapular, and petechial in a single patient. The classical triad of fever with headache and rash was observed in only 20.8% of cases (16 of 77); it was noted in 17.4% of adults and 25.8% of children, but this difference was statistically nonsignificant. Eight patients with headache underwent lumbar puncture, which did not reveal central nervous system involvement. Abnormal laboratory tests were common, the most frequent ones being elevated C-reactive protein (95.9% of patients), elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels (91.1%), elevated aspartate aminotransferase levels (74.3%), and hyponatremia (56.4%). Lymphopenia was present in 29.5% of patients and thrombocytopenia in 41.0%. Overall, the clinical presentation of children and adults did not differ substantially; however, children compared with adults had a higher rate of vomiting (58.1% versus 23.9%, P = 0.05), whereas adults compared with children had a lower lymphocyte count (median of 1.1 × 103/mL versus 1.9 × 103/mL, P < 0.001).

Fifty-seven (73%) patients received appropriate antibiotic therapy, mostly (52/78, 67.5%) doxycycline (Table 2). All except one patient recovered. A single, previously healthy patient whose diagnosis was delayed for 8 days developed purpura fulminans and multiorgan failure. Her diagnosis was confirmed by PCR from blood and skin biopsy. She remained intubated and expired after 162 days in the ICU because of nosocomial infection. Excluding this patient, the mean hospitalization duration was 5.1 days (median: 4 days, range: 1–16 days). Other complications included pneumonitis in three patients (3.9%), splenic infarcts, pericardial effusion, and retinitis in one patient (1.3%), each. In addition, one 15-week pregnant patient elected to terminate her pregnancy.

Table 2.

Anti-rickettsial treatment and outcome

| No. (%), N = 78 | |

|---|---|

| Anti-rickettsial treatment | |

| Doxycycline | 52 (67.5) |

| Azithromycin | 4 (5.2) |

| Doxycycline + ciprofloxacin | 1 (1.3) |

| None | 20 (26) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.3) |

| Outcome | |

| Recovery | 77 (98.7) |

| Death | 1 (1.3) |

| Complications | |

| Pneumonitis | 3 (3.9) |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 (1.3) |

| Retinitis | 1 (1.3) |

| Splenic infarct | 1 (1.3) |

DISCUSSION

We present a large cohort of hospitalized patients diagnosed with murine typhus in a single medical center (AHMC) in Central Israel displaying significant morbidity. Most of the patients resided in two large cities (Lod and Ramla) with mixed Jewish-Arab population within the capture area of AHMC. The heaviest disease burden was noted among the Arab population of these two cities; however, in both the Jewish and Arab population, the disease incidence was several folds higher than the reported national incidence. For example, the reported national incidence in Israel for the year 2010 was 0.04/100,000 population,13 whereas the peak incidence in Lod in 2013 was 53.4/100,000—890 times higher the reported 2010 national incidence. The average incidence among the Jewish population in Lod was 0.79/100,000—13-fold higher than the reported national incidence. The average incidence in Ramla was 10.1/100,000 among the Arab population and 0.36/100,000 among the Jewish population—170 and 6-fold higher than the reported national incidence, respectively.

An upsurge of murine typhus incidence among the Arab population in Lod was noted in the second half of the study period, when the incidence in Lod increased 8.4-fold in 2013 compared with 2006. Notably, the cases were clustered within the Arab neighborhoods with spillage into the Jewish neighborhoods. Our study captured only patients who were hospitalized and diagnosed in AHMC; these cases may be only the tip of the iceberg because many patients may have had a mild disease that did not require hospitalization.7 Thus, the true incidence of murine typhus in Lod and Ramla may have been even higher.

A previous study from Israel also showed a higher incidence of murine typhus among the Arab population.14 The mean national incidence in that study was calculated as 1.42/100,000 among the Arab population and 0.35/100,000 among the Jewish population. Although the incidence among the Jewish population was similar, the incidence among the Arab population was much lower than the incidences observed in Lod and Ramla in our study, suggesting a specific disposition in these two cities. Indeed, several of the patients in our study described increase in the rat population in their neighborhood or spillage of sewage. This has initiated interventions of the local authorities, which may have helped to somewhat reduce the incidence in Lod until the end of 2016, but did not revert the trend.

Of note is the urban residence of the patients in our study. Previous studies from Israel highlighted the high incidence and disease burden among the Bedouin Arabs in southern Israel, who mostly live in rural settlements.14–16 Urban outbreaks were also described in Austin and Galveston, Texas, where free-ranging cats, dogs, opossums, and their fleas might have augmented the rodent–flea cycle.5,17–19 Most recently, another urban outbreak was also reported from Houston, Texas.20 In tropical areas, murine typhus is associated with cities and ports with abundance of urban rats.1

The clinical presentation and laboratory workup for the studied cohort was similar to previously described cohorts in Israel and globally (Table 1).1,21,22 The rate of the classical triad of murine typhus was somewhat low in our study (20.8%) compared with similar studies from Greece (64.4%)23 and Texas (49%).24 However, a recent aggregated report from Texas noted a lower rate of the triad, in only 33.7% of 1,762 cases. It was more likely to be found in children (41.1%) compared with adults (29.3%), probably because of the observation that rash was more frequent in children.17 Similarly, in a systematic review including 2,074 patients, the triad was reported in 35.1% of all cases and in 41.6% of children.25 Rash was reported in 29.9% of cases in the present study. This rate was lower than the rates reported in two previous series from Israel but higher than in a third one (Table 1).15,21,22 In the previously mentioned systematic review, rash was noted in 47.5% of all cases.25 The reason for the lower rate of rash in our series may be due to the retrospective nature of our study. The seasonal pattern of murine typhus in our study was also characteristic.15,17,21

Our study showed significant morbidity among the studied patients, mainly because of the prolonged course of febrile illness before hospitalization (average 8.4 days) and the duration of hospital stay (5.1 days). Similarly, a recent study from Houston, Texas, describes an average duration of 8.1 days of illness before hospital admission and an average of 5.1 days of hospitalization.20 Additional morbidity in our study was related to severe complications occurring in seven patients (8.9%). One patient in our series was admitted to ICU and died of multiorgan failure. Severe complications were also reported from prior Israeli studies. A study of 100 hospitalized patients from the years 1969–1972 reported one patient with transient paraparesis and another with acute renal failure requiring dialysis.21 Another study of 45 hospitalized patients from the years 1976–1985 described three patients (3.3%) with severe complications, including pneumonitis in two patients, and encephalitis in one.22 None of these patients died. Several studies from Texas also described significant morbidity. In a study including 53 patients with murine typhus from Austin, Texas, one patient, each, had pneumonitis, life-threatening coagulopathy, and renal failure. Seventy percent of the patients were hospitalized and 27% were admitted to ICU.5 A pediatric series from Texas, including 97 children, reported a high rate of severe complications, including 12% of pneumonitis, 8% of stupor, and 2% of ataxia. Hospitalization rate was 58%.24 Even higher rates (25.6%) of severe complications were reported among 90 hospitalized adults from Greece.23 Complications included pulmonary involvement (13 patients), stupor or coma (10), acute renal failure (seven), and disseminated intravascular coagulation (two). The age of the patients with complications was significantly higher.23 In a prospective study of 49 elderly patients with murine typhus, the complication rate was substantial, reaching 32.7%.26 This was manifested by a high rate of central nervous system complications (20.4%) and renal failure (12.3%), although no fatalities occurred. Notably, time to defervesce after initiation of appropriate treatment was also prolonged. Worse outcome for elderly patients may also be inferred from a recent series of fatal murine typhus cases.8 In this report, most of the patients were older than 50 years, and their median age was 62 years. They presented with a high rate of pulmonary (55%) and neurologic (63%) complications.

Overall, fatality is rare in murine typhus. In a recent retrospective study of 3,048 confirmed or probable cases of murine typhus from Texas, the case fatality rate was 0.4%.8 Likewise, a recent systematic review described an infection-related death rate of 0.33%.25

The main limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. This may have caused underestimation of symptoms occurring later in the disease course, and particularly the appearance of rash. Another major limitation is the method of diagnosis, which was based on a single IgM titer of IFA assay. Most patients recovered and were discharged from hospital before the time for a second convalescent test and were not followed in the community. This may have caused inclusion of patients with false-positive diagnosis of murine typhus. However, the positive cases clustered in specific neighborhoods, which makes this less likely. A similar method of diagnosis was also used in a large prior study from Israel.14 Cross-reactivity with other rickettsial groups endemic to Israel or C. burnetii was not likely, as concomitant serologic tests for R. conorii C. burnetii were negative.27,28 In the only fatal case in our series, the diagnosis was confirmed by PCR.

In summary, we present a cohort of patients hospitalized with the diagnosis of murine typhus and exhibiting a high burden of morbidity. Although murine typhus is often referred to as mild, self-limited rickettsial disease, our series and recent publications show high hospitalization rates and substantial morbidity mainly because of pulmonary, neurologic, and kidney involvement. Fortunately, in recent years, fatal cases are rare-not reaching 1%.

Our study also found a high incidence and recent upsurge of murine typhus in the Arab neighborhoods of two cities in central Israel. This calls for more focused intervention in these neighborhoods, including better rodent control and improved maintenance of the sewage infrastructure. Better understanding of the role of rodents or possible other reservoirs such as stray cats in this outbreak is also imperative.

REFERENCES

- 1.Civen R, Ngo V, 2008. Murine typhus: an unrecognized suburban vectorborne disease. Clin Infect Dis 46: 913–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aung AK, Spelman DW, Murray RJ, Graves S, 2014. Rickettsial infections in southeast Asia: implications for local populace and febrile returned travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg 91: 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faccini-Martinez AA, Garcia-Alvarez L, Hidalgo M, Oteo JA, 2014. Syndromic classification of rickettsioses: an approach for clinical practice. Int J Infect Dis 28: 126–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mumcuoglu KY, Ioffe-Uspensky I, Alkrinawi S, Sarov B, Manor E, Galun R, 2001. Prevalence of vectors of the spotted fever group Rickettsiae and murine typhus in a Bedouin town in Israel. J Med Entomol 38: 458–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adjemian J, Parks S, McElroy K, Campbell J, Eremeeva ME, Nicholson WL, McQuiston J, Taylor J, 2010. Murine typhus in Austin, Texas, USA, 2008. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 412–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanton LS, Dumle rJS, Walker DH, 2015. Rickettsia typhi (Murine Typhus). Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser J, eds. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2221–2225. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker DH, Parks FM, Betz TG, Taylor JP, Muehlberger JW, 1989. Histopathology and immunohistologic demonstration of the distribution of Rickettsia typhi in fatal murine typhus. Am J Clin Pathol 91: 720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pieracci EG, Evert N, Drexler NA, Mayes B, Vilcins I, Huang P, Campbell J, Behravesh CB, Paddock CD, 2017. Fatal flea-borne typhus in Texas: a retrospective case series, 1985–2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg 96: 1088–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker DH, Feng HM, Ladner S, Billings AN, Zaki SR, Wear DJ, Hightower B, 1997. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of typhus rickettsioses using an anti-lipopolysaccharide monoclonal antibody. Mod Pathol 10: 1038–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paris DH, Blacksell SD, Stenos J, Graves SR, Unsworth NB, Phetsouvanh R, Newton PN, Day NP, 2008. Real-time multiplex PCR assay for detection and differentiation of Rickettsiae and Orientiae. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102: 186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botelho-Nevers E, Socolovschi C, Raoult D, Parola P, 2012. Treatment of Rickettsia spp. infections: a review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 10: 1425–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gikas A, Doukakis S, Pediaditis J, Kastanakis S, Manios A, Tselentis Y, 2004. Comparison of the effectiveness of five different antibiotic regimens on infection with Rickettsia typhi: therapeutic data from 87 cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg 70: 576–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel Center For Disease Control (ICDC) 2012. Notifiable Infectious Diseases in Israel: 60 Years of Surveillance 1951–2010. Jerusalem, Israel: DOEPHS; Publication 342. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishara J, Hershkovitz D, Yagupsky P, Lazarovitch T, Boldur I, Kra-Oz T, Pitlik S, 2004. Murine typhus among Arabs and Jews in Israel 1991—2001. Eur J Epidemiol 19: 1123–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shalev H, Raissa R, Evgenia Z, Yagupsky P, 2006. Murine typhus is a common cause of febrile illness in Bedouin children in Israel. Scand J Infect Dis 38: 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross EM, Arbeli Y, Bearman JE, Yagupsky P, Cohar K, Torok V, Goldwasser RA, 1984. Spotted fever and murine typhus in the Negev desert region of Israel, 1981. Bull World Health Organ 62: 301–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray KO, Evert N, Mayes B, Fonken E, Erickson T, Garcia MN, Sidwa T, 2017. Typhus group rickettsiosis, Texas, USA, 2003–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 23: 645–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanton LS, Vohra RF, Bouyer DH, Walker DH, 2015. Reemergence of murine typhus in Galveston, Texas, USA, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 21: 484–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanton LS, Idowu BM, Tatsch TN, Henderson JM, Bouyer DH, Walker DH, 2016. Opossums and cat fleas: new insights in the ecology of murine typhus in Galveston, Texas. Am J Trop Med Hyg 95: 457–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson T, da Silva J, Nolan MS, Marquez L, Munoz FM, Murray KO, 2017. Newly recognized pediatric cases of typhus group rickettsiosis, Houston, Texas, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 23: 2068–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenthal T, Michaeli D, 1977. Murine typhus and spotted fever in Israel in the seventies. Infection 5: 82–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaked Y, Samra Y, Maeir MK, Rubinstein E, 1988. Murine typhus and spotted fever in Israel in the eighties: retrospective analysis. Infection 16: 283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaliotis G, Kritsotakis EI, Psaroulaki A, Tselentis Y, Gikas A, 2012. Murine typhus in central Greece: epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and therapeutic-response features of 90 cases. Int J Infect Dis 16: e591–e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiteford SF, Taylor JP, Dumler JS, 2001. Clinical, laboratory, and epidemiologic features of murine typhus in 97 Texas children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 155: 396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, Prousali E, Miligkos M, Karageorgos SA, 2017. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop 166: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsioutis C, Chaliotis G, Kokkini S, Doukakis S, Tselentis Y, Psaroulaki A, Gikas A, 2014. Murine typhus in elderly patients: a prospective study of 49 patients. Scand J Infect Dis 46: 779–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keysary A, Strenger C, 1997. Use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques with cross-reacting human sera in diagnosis of murine typhus and spotted fever. J Clin Microbiol 35: 1034–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vardi M, Petersil N, Keysary A, Rzotkiewicz S, Laor A, Bitterman H, 2011. Immunological arousal during acute Q fever infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 30: 1527–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]