Abstract

Background: Sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) blockade or lesioning can offer significant pain relief for cluster headaches (CHs) and a variety of other pain syndromes involving the head and face.

Methods: We reviewed the literature on the efficacy of SPG block and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) using PubMed and Google Scholar.

Results: The infrazygomatic technique can be used to directly access the SPG for injection of local anesthetic or lesioning using RFA. Important technical points to achieve these procedures are described. SPG blockade efficacy is supported by randomized controlled studies but SPG RFA is not.

Conclusion: Targeting the SPG is a promising treatment option for refractory CHs. RFA and neuromodulation have the potential to offer long-term significant pain relief, but more randomized studies are needed to demonstrate their efficacy.

Keywords: Cluster headache, radiofrequency ablation, sphenopalatine ganglion block

INTRODUCTION

For many years, the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) has been a neural target for treatment of a variety of headache and facial pain conditions such as cluster headaches (CHs), atypical facial pain, trigeminal neuralgia, and migraine headaches with variable degrees of success. The SPG, also known as the pterygopalatine ganglion or Meckel ganglion, is an extracranial parasympathetic ganglion that lies in an inverted pyramidal space called the pterygopalatine fossa. It is the largest ganglion outside of the calvarium containing sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory neurons.1 Lying immediately posterior to the middle nasal turbinate, the SPG is the only ganglion that can be accessed externally via the nasal mucosa.2

Relevant Anatomy

Three principal neural pathways intersect within the SPG. The sensory pathway accounts for a generous portion of the sensory innervation to the face and neck. Head and neck sensory nerves course through the SPG and coalesce to form its pterygopalatine branches that, along with the maxillary nerve, terminate at the trigeminal ganglion.3

The postganglionic sympathetic pathway arises from the superior cervical ganglion and courses through the calvarium as the deep petrosal nerve. The deep petrosal nerve combines with the parasympathetic greater petrosal nerve immediately before the foramen lacerum to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal, or Vidian nerve. The Vidian nerve terminates in the pterygopalatine fossa, becoming a large portion of the SPG. These sympathetic neurons coursing through the SPG provide vasoconstrictive innervation to the nasal cavity, upper pharynx, and palate.3

The parasympathetic pathway originates in the superior salivatory nucleus (SSN) of the pons. The preganglionic parasympathetic neurons course through the skull as the nervus intermedius, the geniculate nucleus, the greater petrosal nerve, and the Vidian nerve before synapsing within the SPG. The postganglionic neurons provide secretomotor innervation to the lacrimal, nasal, palatine, and pharyngeal glands.3

Pathophysiology and Pain Syndromes

With its broad nerve supply and interconnections with the trigeminal and facial nerves, the SPG has been implicated as a contributor to a variety of headache and facial pain disorders. The signaling pathway of greatest interest regarding SPG-mediated pain is known as the trigeminal-autonomic reflex.4 The pathway begins with stimulation of the SSN from afferent trigeminal nerves, which in turn causes parasympathetic activation of meningeal vessels, nasopharyngeal mucosa, and lacrimal glands. Activation of the pathway stimulates release of vasoactive peptides, leading to extravasation of plasma proteins and neurogenic inflammation.5

Clinically, activation of this pathway can manifest as a variety of autonomic symptoms, including lacrimation, nasal congestion and rhinorrhea, conjunctival injection, periorbital edema, and craniofacial sweating. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are a collection of headache disorders that share these autonomic symptoms. Included under the classification of TACs are CH, paroxysmal hemicrania, and hemicrania continua. The intimate involvement of the SPG in the neural pathways associated with TACs has made it a notable target for clinicians treating patients with these disorders.5

CH is the most common and well studied of the TACs. CH is characterized by unilateral headache pain in the trigeminal V1 dermatome and is classically associated with parasympathetic symptoms of lacrimation, nasal congestion, and conjunctival injection. CH can also manifest with sympathetic symptoms similar to those of Horner syndrome, including unilateral anhidrosis, ptosis, and miosis.6

A strong argument exists for the role of the SPG in chronic migraines. Common triggers for migraines include sleep deprivation, food, olfactory stimuli, and general stress. All of these triggers activate areas of the brain that send projections to the SSN. Stimulation of the SSN activates the SPG, ultimately causing vasodilation and release of inflammatory mediators in the meninges.3 Additionally, the SPG receives afferent nociceptive signals from the V2 division of the trigeminal nucleus while acting as a conduit for a major portion of facial efferent fibers.7

A widely proposed mechanism for pain relief from SPG blocks is their ability to interfere with parasympathetic outflow.3

Therapies that target the SPG have been used with increasing frequency since the beginning of the 20th century.8 Modern therapies primarily include SPG block and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the SPG. Both of these treatment modalities have been studied with promising evidence of effectiveness in the treatment of CHs, migraines, and trigeminal neuralgia. Blockade and ablation of the SPG have also been studied to a lesser degree in cases of postherpetic neuralgia, head and neck cancer pain, postoperative analgesia after endoscopic sinus surgery, and atypical facial pain syndromes.2,9,10

METHODS

We searched the electronic databases of PubMed and Google Scholar for relevant articles. Sources cited in eligible articles were screened for additional studies. The search terms used in acquiring articles from databases were “(sphenopalatine AND ganglion AND block),” “(sphenopalatine AND ganglion AND (radiofrequency OR RFA)),” and “(sphenopalatine AND ganglion AND neuromodulation OR stimulation).” Thirty-two appropriate articles were identified in the search.

SPHENOPALATINE GANGLION BLOCK

The earliest example of SPG blockade was by Sluder in 1909. He successfully aborted symptoms of CH with intranasal application of varying concentrations of cocaine.8 In modern practice, the intranasal approach is often used as a diagnostic tool prior to percutaneous approaches or as an abortive treatment for acute symptoms. A pledget soaked with local anesthetic is advanced intranasally along the superior aspect of the middle turbinate overlying the SPG. Specialized local anesthetic delivery systems such as the Tx360 (Tian Medical) and the SphenoCath (Dolor Technologies, LLC) attempt to address anatomic limitations with flexible sheaths and angled catheters.11 Advantages to the transnasal approach are its technical simplicity, short procedure time, and low overall risks that are principally limited to epistaxis and infection.3,12 Wasserman et al described a statistically significant increase in temperature in the V2 distribution following intranasal SPG block.13 This finding suggests that delivery of anesthetic to the sphenopalatine foramen results in blockade of the sympathetic fiber activity, possibly via the maxillary artery plexus branches surrounding the sphenopalatine foramen prior to parasympathetic activity in the SPG.

The transoral approach, often performed by dentists, is a needle-based invasive route in which the SPG is reached by passing through the posterior end of the hard palate and the greater palatine foramen. This method can be technically challenging and unpredictable with regard to ensuring proper anesthetic placement.3,14 A suprazygomatic percutaneous approach has also been described and was used in studies, including the largest case series on SPG blocks to date.15

The percutaneous infrazygomatic approach is most commonly practiced by interventional pain physicians and uses fluoroscopy to guide needle placement. Fluoroscopic-guided needle placement allows for direct administration of local anesthetic to the SPG rather than diffusion across mucous membranes as seen in the intranasal approach. Fluoroscopic placement also allows subsequent RFA of the SPG if temporary relief is achieved with the block. Computed tomography–guided needle placement has also been described.16 In this technique, a needle is placed just inferior to the zygomatic arch and anterior to the mandible, between the ramus and the posterior border of the zygomatic bone. From this point, it is advanced medially and superiorly toward the pterygopalatine fossa. Once the desired location is confirmed, local anesthetic is injected.12

Infrazygomatic Technique–Technical Note

The authors’ preferred infrazygomatic method is as follows:

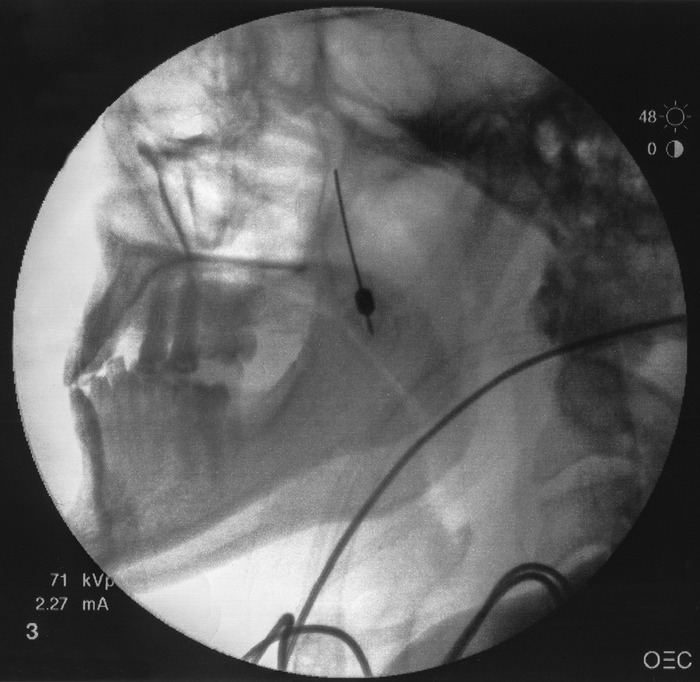

A lateral fluoroscopic view of the face is obtained with the C-arm by superimposing the mandibular rami on top of each other (Figure 1).

A skin wheal inferior to the zygomatic arch and anterior to the mandible is created with 1% lidocaine.

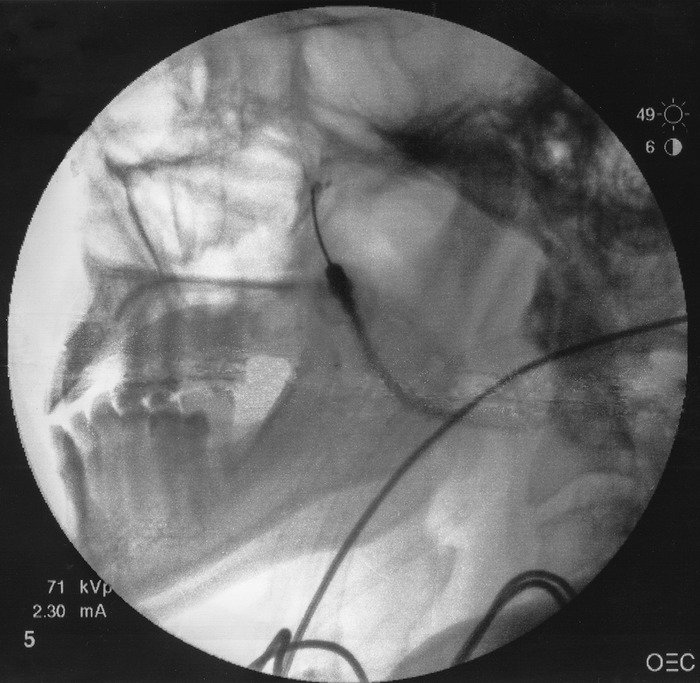

A 22- or 25-gauge 3½-inch spinal needle with a slightly bent tip is inserted coaxially with lateral fluoroscopic guidance. This view is the main view used while advancing the needle toward the pterygopalatine fossa. The needle is advanced superiorly and medially toward the pterygopalatine fossa (Figure 2).

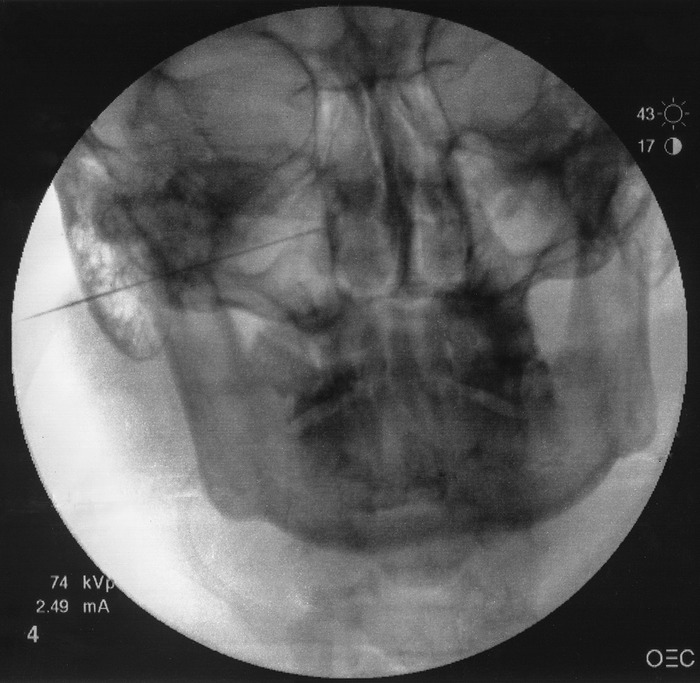

An anteroposterior (AP) view is intermittently obtained to check the depth of the needle and avoid any breach to the nasal wall. The needle tip should terminate immediately lateral to the ipsilateral nasal wall as shown in the AP view (Figure 3).

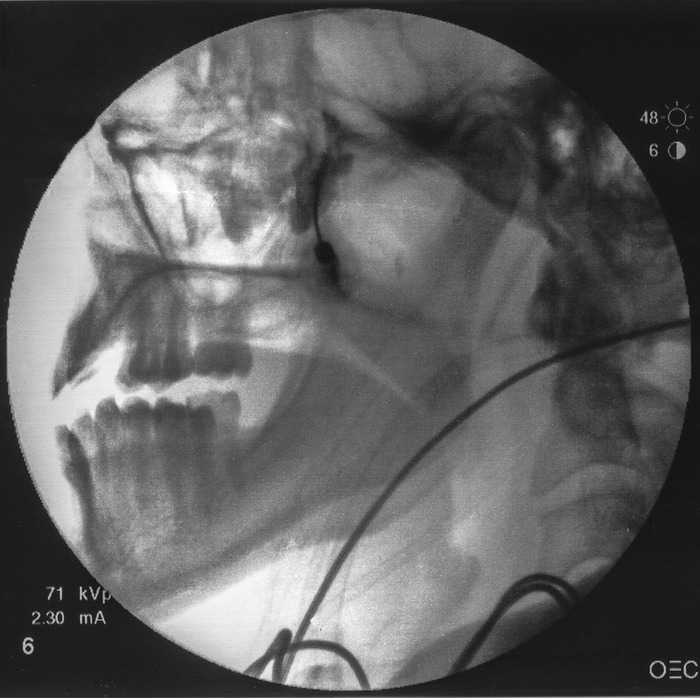

Following final needle positioning, 0.2 mL of contrast material is injected under live fluoroscopic imaging to rule out intravascular spread and confirm spread of the dye within the pterygopalatine fossa (Figure 4).

Local anesthetic, such as 1-2 mL of 1% lidocaine with or without dexamethasone, is slowly injected into the fossa.

Figure 1.

Lateral fluoroscopic view of the face showing superimposed mandibular rami.

Figure 2.

Fluoroscopic guidance of superomedial advancement of bent-tipped spinal needle toward pterygopalatine fossa.

Figure 3.

Anteroposterior view showing needle tip terminating immediately lateral to ipsilateral nasal wall.

Figure 4.

Contrast material injected with appropriate spread confirming correct placement within the pterygopalatine fossa.

Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block Efficacy

Determining the efficacy of SPG blocks has been a gradual process during the past century, and results have varied by the pain disorder in question. SPG blocks have been used in few studies above the level of case series; however, because of several controlled trials, it is becoming increasingly apparent that SPG blocks are effective in the short-term treatment of CHs, trigeminal neuralgia, migraines, and pain associated with specific nasal and oral-maxillofacial procedures.11,16-23

In a double-blind placebo-controlled study, Costa et al administered SPG blocks to patients with CHs.17 Nitroglycerin was used to induce CHs in 15 patients who were then treated with transnasal application of 10% cocaine hydrochloride, 10% lidocaine, or normal saline. The solutions were applied to both the symptomatic and the asymptomatic sides for 5 minutes. One hundred percent of the patients who received lidocaine or cocaine solutions reported symptomatic relief in 37 and 31 minutes on average, respectively, compared to 59 minutes in the saline group.

One randomized controlled study explored the efficacy of SPG blockade on refractory trigeminal neuralgia. In this study by Kanai et al, 25 patients received 8% transnasal lidocaine spray or a saline placebo.18 Pain was triggered by touching or manipulating the face, and results were assessed. The study showed a significant decrease in pain for a mean of 4.3 hours.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Cady et al in 2015 used the transnasal approach to apply 0.5% bupivacaine with a specialized local anesthetic applicator (Tx360) for the treatment of chronic migraine.11 Their results showed a statistically significant decrease in headache pain on the numeric rating scale at 24 hours (P<0.001). However, this treatment method did not provide lasting pain relief beyond 24 hours.

To date (2007-2016), 6 double-blind placebo-controlled trials have investigated the efficacy of SPG block in providing analgesia after endoscopic sinus surgery. Of the 6 studies, 5 demonstrated a significant reduction in the need for postoperative analgesia in patients treated with SPG blocks.19-24

Parameswaran et al conducted a double-blind, randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of SPG block as an adjunct to general anesthesia in 100 pediatric patients undergoing palatoplasty.25 Using a transoral approach, the surgeons administered 1 mL of 0.75% ropivacaine in a small target area directly posterior to the middle turbinate. Direct visualization of the nasal cavity was made possible by the inherent defects in the hard and soft palates of the patients. The team's results showed a statistically significant increase in the postsurgical pain-free duration from 19.46 minutes in the control group to 87.59 minutes in the study group.

RADIOFREQUENCY ABLATION

RFA of the SPG seeks to extend the pain relief achieved by SPG blockade. RFA is a valuable and potentially longer lasting option for patients with conditions such as intractable CHs who respond favorably to SPG blocks.12

RFA of the SPG can result in temporary or, in rare cases, permanent hypoesthesia or dysesthesia of the palate, maxilla, or posterior pharynx. Interestingly, reflex bradycardia has been reported during radiofrequency lesioning that could be explained by the rich parasympathetic connections in the SPG.26 Choosing pulsed radiofrequency vs conventional thermal ablation may help to reduce these effects; however, limited evidence is available.27-29

Radiofrequency Ablation–Technical Note

Ablative techniques are made possible by image-guided infrazygomatic approaches exclusively. The infrazygomatic technique described in the previous section can be modified to perform RFA as follows:

A 22-gauge, 10 cm, curved radiofrequency needle with a 5 mm active tip is inserted coaxially with lateral fluoroscopic guidance and is advanced superiorly and medially toward the pterygopalatine fossa in the same manner as described for the infrazygomatic technique.

An AP view is intermittently obtained to check the depth of the needle and avoid any breach of the nasal wall. The needle tip should terminate immediately lateral to the ipsilateral nasal wall.

Upon confirmation of proper needle position with negative intravascular spread, sensory stimulation is carried out at 50 Hz with a 1 millisecond pulse duration.

Deep perinasal and maxillary paresthesias at <0.5 V signify a favorable needle position.

After stimulation and proper positioning are confirmed, local anesthetic is injected, and neurotomy is performed at 80°C for 90 seconds if thermal conventional RFA is used. Pulsed RFA of the SPG is an acceptable alternative to conventional thermal lesioning.

Sphenopalatine Ganglion Radiofrequency Ablation Efficacy

While no controlled studies have been conducted to date on the efficacy of RFA in the treatment of any pain disorder, several case reports and series have been promising, and one cohort study had significant results.9,29

Narouze et al conducted a prospective cohort study in which 15 patients suffering from chronic CHs underwent SPG RFA.9 Using a fluoroscopically guided infrazygomatic approach, 0.5 mL of lidocaine was injected, and 2 RF lesions were performed at 80°C for 60 seconds each, followed by the injection of 0.5 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and 5 mg of triamcinolone postablation. The study reported statistically significant improvement in attack intensity, frequency, and pain disability index at interval follow-ups through 18 months.

RFA of the SPG has also been used in myriad other head and facial pain disorders, including Sluder neuralgia, posttraumatic headache, atypical trigeminal neuralgia, atypical facial pain, chronic facial pain secondary to cavernous sinus meningioma, trigeminal neuralgia, and SPG neuralgia attributable to herpes zoster. Akbas et al published a case series of 27 subjects with various types of head and facial pain.29 Pain was completely relieved in 35% of cases, moderately relieved in 42%, and ineffective in the remaining 23% undergoing RFA.

NEUROMODULATION

Neuromodulation of the SPG is an emerging option for the treatment of a variety of headaches and facial pain conditions, notably CHs.30,31 Neuromodulation of the SPG is potentially more effective than drug treatments in relieving chronic neuropathic pain conditions while potentially more cost effective.30,31 The longest period without CH attacks averaged 149 days in 30% of subjects treated with neuromodulation.32 Devices implanted through the back of the mouth under the cheek of the upper jaw are used to modulate neuronal activities in the SPG and could be used to treat various facial conditions such as CHs. In Europe, a multicenter clinical trial, the Pathway CH-1 study, showed an overall reduction in disability from CH in participants who used a handheld controller to activate an implanted SPG neurostimulator at the start of a headache attack.31 A follow-up study by Jürgens et al concluded that SPG stimulation is an effective acute therapy in 45% of patients suffering from CHs, offering sustained effectiveness during the 24 months of observation. In addition, a maintained, clinically relevant reduction of attack frequency was observed in one-third of patients.33 These new findings are encouraging and may lead to further studies on neurostimulation to treat craniofacial pain syndromes.

CONCLUSION

The SPG has been a therapeutic target for headache and facial pain disorders for more than a century. The therapies with the strongest levels of evidence include the SPG block and RFA for the treatment of CHs. While these methods also have promising evidence for use in migraines, trigeminal neuralgias, and postoperative pain associated with sinus surgeries, more large-scale, randomized controlled trials are warranted if these techniques are to become standards of care. Emerging techniques, such as neuromodulation of the SPG, are available and may provide a cost-effective reliable option for treatment of a variety of headache and facial pain conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Medical Knowledge, and Practice-Based Learning and Improvement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Láinez MJ, Puche M, Garcia A, Gascón F. Sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation for the treatment of cluster headache. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2014. May;7(3):162-168. doi: 10.1177/1756285613510961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho KWD, Przkora R, Kumar S. Sphenopalatine ganglion: block, radiofrequency ablation and neurostimulation - a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2017. December 28;18(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0826-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piagkou M, Demesticha T, Troupis T, et al. The pterygopalatine ganglion and its role in various pain syndromes: from anatomy to clinical practice. Pain Pract. 2012. June;12(5):399-412. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins MS, Robertson CE, Kaplan E, et al. The sphenopalatine ganglion: anatomy, pathophysiology, and therapeutic targeting in headache. Headache. 2016. February;56(2):240-258. doi: 10.1111/head.12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mojica J, Mo B, Ng A. Sphenopalatine ganglion block in the management of chronic headaches. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017. June;21(6):27. doi: 10.1007/s11916-017-0626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013. July;33(9):629-808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, Bajwa ZH, et al. 2003 Wolff Award: possible parasympathetic contributions to peripheral and central sensitization during migraine. Headache. 2003. Jul-Aug;43(7):704-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sluder G. The anatomical and clinical relations of the sphenopalatine (Meckel's) ganglion to the nose and its accessory sinuses. https://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b2248601x#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=9&z=-0.838%2C0.1021%2C2.7181%2C1.3753. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- 9.Narouze S, Kapural L, Casanova J, Mekhail N. Sphenopalatine ganglion radiofrequency ablation for the management of chronic cluster headache. Headache. 2009. April;49(4):571-577. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanella S, Buccelletti F, Franceschi F, et al. Transnasal sphenopalatine ganglion blockade for acute facial pain: a prospective randomized case-control study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018. January;22(1):210-216. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201801_14119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cady R, Saper J, Dexter K, Manley HR. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of repetitive transnasal sphenopalatine ganglion blockade with tx360(®) as acute treatment for chronic migraine. Headache. 2015. January;55(1):101-116. doi: 10.1111/head.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naouze SN. Sphenopalatine ganglion block and radiofrequency ablation. In: Narouze SN, ed. Interventional Management of Head and Face Pain: Nerve Blocks and Beyond. New York, NY: Springer Science; 2014:47-52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasserman RA, Schack T, Moser SE, Brummett CM, Cooper W. Facial temperature changes following intranasal sphenopalatine ganglion nerve block. J Nat Sci. 2017;3(5):e354. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruskin SL. Technique of sphenopalatine ganglion therapy for chorioretinitis. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1951. January;30(1):28-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devoghel JC. Cluster headache and sphenopalatine block. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 1981;32(1):101-107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallejo R, Benyamin R, Yousuf N, Kramer J. Computed tomography-enhanced sphenopalatine ganglion blockade. Pain Pract. 2007. March;7(1):44-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa A, Pucci E, Antonaci F, et al. The effect of intranasal cocaine and lidocaine on nitroglycerin-induced attacks in cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2000. March;20(2):85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanai A, Suzuki A, Kobayashi M, Hoka S. Intranasal lidocaine 8% spray for second-division trigeminal neuralgia. Br J Anaesth. 2006. October;97(4):559-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed HM, Abu-Zaid EH. Role of intraoperative endoscopic sphenopalatine ganglion block in sinonasal surgery. J Med Sci. 2007;7(8):1297-1303. doi: 10.3923/jms.2007.1297.1303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Qudah M. Endoscopic sphenopalatine ganglion blockade efficacy in pain control after endoscopic sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016. March;6(3):334-338. doi: 10.1002/alr.21644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali AR, Sakr SA, Rahman ASMA. Bilateral sphenopalatine ganglion block as adjuvant to general anaesthesia during endoscopic trans-nasal resection of pituitary adenoma. Egypt J Anaesth. 2010. October;26(4):273-280. doi: 10.1016/j.egja.2010.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho DY, Drover DR, Nekhendzy V, Butwick AJ, Collins J, Hwang PH. The effectiveness of preemptive sphenopalatine ganglion block on postoperative pain and functional outcomes after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011. May-Jun;1(3):212-218. doi: 10.1002/alr.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeMaria S Jr, Govindaraj S, Chinosorvatana N, Kang S, Levine AI. Bilateral sphenopalatine ganglion blockade improves postoperative analgesia after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012. Jan-Feb;26(1):e23-e27. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kesimci E, Öztürk L, Bercin S, Kiriş M, Eldem A, Kanbak O. Role of sphenopalatine ganglion block for postoperative analgesia after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012. January;269(1):165-169. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1702-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parameswaran A, Ganeshmurthy MV, Ashok Y, Ramanathan M, Markus AF, Sailer HF. Does sphenopalatine ganglion block improve pain control and intraoperative hemodynamics in children undergoing palatoplasty? A randomized controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018. September;76(9):1873-1881. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2018.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konen A. Unexpected effects due to radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion: two case reports. Pain Digest. 2000;10:30-33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayer E, Racz GB, Miles D, Heavner J. Sphenopalatine ganglion pulsed radiofrequency treatment in 30 patients suffering from chronic face and head pain. Pain Pract. 2005. September;5(3):223-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narouze S. Complications of head and neck procedures. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2007. July;11(3):171-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akbas M, Gunduz E, Sanli S, Yegin A. Sphenopalatine ganglion pulsed radiofrequency treatment in patients suffering from chronic face and head pain. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2016. Jan-Feb;66(1):50-54. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pietzsch JB, Garner A, Gaul C, May A. Cost-effectiveness of stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) for the treatment of chronic cluster headache: a model-based analysis based on the Pathway CH-1 study. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:530. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0530-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoenen J, Jensen RH, Lantéri-Minet M, et al. Stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) for cluster headache treatment. Pathway CH-1: a randomized, sham-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2013. July;33(10):816-830. doi: 10.1177/0333102412473667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barloese MC, Jürgens TP, May A, et al. Cluster headache attack remission with sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation: experiences in chronic cluster headache patients through 24 months. J Headache Pain. 2016. December;17(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0658-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jürgens TP, Barloese M, May A, et al. Long-term effectiveness of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation for cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2017. April;37(5):423-434. doi: 10.1177/0333102416649092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]