Abstract

In the last decades, strategies have been evaluated to reduce rumen methane (CH4) production by supplementing tropical forages rich in secondary compounds; however, most of these beneficial effects need to be validated in terms of their persistence over time. The aim of this study was to assess CH4 emissions over time in heifers fed with and without Gliricidia sepium foliage (G) mixed with ground pods of Enterolobium cyclocarpum(E). Two groups of 4 crossbred (Bos taurus x Bos indicus) heifers (284 ±17 kg initial weight) were fed with 2 diets (0% and 15% of a mixture of the pods and foliage [E + G:0 and E + G:15, respectively]) over 80 d, plus 2 wk before the experiment, in which every animal was fed a legume and pod-free diet. Every 14 d, CH4 production, apparent digestibility, volatile fatty acids (VFA), and microbial population were quantified for each animal. The experiment was conducted with a repeated measurements design over time. Diets fed differed in terms of their crude protein (CP), condensed tannins, and saponins content supplied by E. cyclocarpum and G. sepium. For most of the experiment, dry matter intake (DMI) and digestible dry-matter intake (DDMI) were 6.3 kg DMI/d and 512 g DDMI/kg, respectively, for both diets (diet: P > 0.05). Apparent digestible crude protein (DCP) was reduced by 21 g DCP/kg DM when the diet was supplemented with E + G:15 (P = 0.040). Molar proportions of VFA’s in the rumen did not differ between diets or in time (P > 0.05). Daily methane production, expressed in relation to DMI, was 23.95 vs. 23.32 g CH4/kg DMI for the diet E + G:0 and E + G:15, respectively (diet: P = 0.016; Time: P > 0.05). Percent gross energy loss as CH4 (Ym) with grass-only diets was above 8.1%, whereas when feeding heifers with the alternate supplementation, Ym values of 7.59% (P = 0.016) were observed. The relative abundance of total bacterial, protozoa, and methanogenic archaeal replicates was not affected by time nor by the incorporation of legume and pods into the diet (P > 0.05). Results suggest that addition of G. sepium mixed with E. cyclocarpum pods can reduce CH4 production in heifers and this response remains over time, without effect on microbial population and VFA concentration and a slight reduction in CPD digestibility.

Keywords: cattle, greenhouse gas, legumes, long-term feeding, microbial population

INTRODUCTION

Ruminal microorganisms have been known for decades to be of major importance to the host, as they are largely responsible for the health and the conversion efficiency of feedstuffs in domestic animals (Cammack et al., 2018). In addition, methane (CH4) is produced in the rumen by microorganisms from the Archaea domain (Lui and Whitman, 2008). These microorganisms benefit from the end products of fermentation (ATP, N-NH3) carried out by bacteria, fungi, and protozoa (Martin et al., 2010). Some strategies to reduce CH4 production propose regulating ruminal fermentation by supplying secondary compounds to improve nutritional quality of diets (Eckard et al., 2010). Condensed tannins (CT) and saponins may directly or indirectly reduce CH4 emissions between 10% and 35% (Hess et al., 2006; Albores-Moreno et al., 2017; Piñeiro-Vázquez et al., 2018). These secondary metabolites can negatively affect the diversity or activity of methanogens as a result of the changes in the cellular membrane of microorganisms, reducing the availability of hydrogen, changing fermentation pattern, or by forming complexes with other nutritional compounds (Jayanegara et al., 2015; Wallace et al., 2014; Patra et al., 2017).

In this respect, Enterolobium cyclocarpum (“parota,” “orejero,” or “piñón de oreja”) pods and Gliricidia sepium (“matarraton” or “madero negro”) foliage have shown promising results as animal feed and in reducing CH4 in a short period of time, due to the crude protein (CP), saponin, and CT contained (Pizzani et al., 2006; Narayan et al., 2013; Asaolu et al., 2014; Archimède et al., 2016; Torres-Salado et al., 2018). However, some authors, such as Newbold et al. (1997), Wina et al. (2006), and Ramos-Morales et al. (2017), reported that the actions of secondary compounds may be transient, since microorganisms are able to degrade or develop protection mechanisms against these compounds. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to evaluate CH4 emissions and changes in microbial population over time in crossbred heifers fed with and without G. sepium foliage mixed with E. cyclocarpum pods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animals in this research were handled according to a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, University of Yucatan (UADY), Mexico.

Study Site, Animals, and Experimental Design

The study was conducted at the Climate Change and Livestock Production Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science (Merida, Mexico, latitude 21°15′ N; longitude 83°32′ W) from May to September 2017. During this period, temperatures ranged between 21 °C and 36 °C; monthly rainfall ranged between 69 and 183 mm (INEGI, 2017).

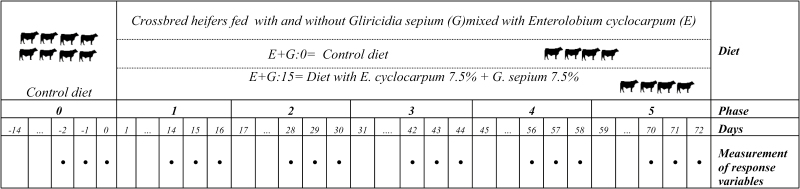

The experiment was conducted using a repeated measures design (Littell et al., 1998; Robinson et al., 2015). For this purpose, 2 groups of 4 crossbred (Bos taurus x Bos indicus) heifers with an initial weight of 284 ±17 kg and 18 ± 3 mo of age were used. These animals were fed 2 types of diets (with and without E. cyclocarpum (E) mixed with G. sepium (G): E + G:15 and E + G:0, respectively) for 80 d. During this period, every 14 d, and for 2 consecutive days, enteric CH4 production and apparent digestibility were determined; ruminal fluid was also sampled (Figure 1). In addition, there was a 14-d period prior to the experiment (phase 0), where all animals were fed the same diet (without legumes and pods) to cleanse the rumen from the carryover effect of previous diets on all variables evaluated. To ensure the repeatability of the experiment, the diets fed to the animals did not change in quality and quantity throughout the experiment.

Figure 1.

Experimental design of heifers fed (long-term) with and without Gliricidia sepium mixed with Enterolobium cyclocarpum.

Experimental Diets, Feed Intake, and Digestibility

The control diet consisted of 2 tropical grass hays (Megathyrsus maximus [syn. Panicum maximum] cv. Guinea and Sorghum halepense [L.] Pers. (Johnson grass), respectively), plus soybean meal, wheat bran, cane molasses, and a commercial mineral mixture. In the experimental diet, grasses were substituted by 7.5% E. cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. ground pods mixed with 7.5% of G. sepium (Jacq.) Steud. Leaves. Diets were formulated according to the National Research Council (NRC, 2016) guidelines to meet the maintenance and growth requirements of heifers. Table 1 shows the nutrient composition and proportion of ingredients and experimental diets. All animals had free access to fresh water and were housed individually in pens measuring 3-m long and 3-m wide.

Table 1.

Proportion of ingredients and chemical composition of the ingredients and experimental diets

| Items | Ingredients | Diets1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorghum halepense | Panicum maximum | Enterolobium cyclocarpum | Gliricidia sepium | Soybean meal | Wheat bran | Cane molasses | E + G:0 | E + G: 15 | |

| Chemical composition | |||||||||

| Dry matter | 911.9 | 883.5 | 955.7 | 912.1 | 916.4 | 915.0 | 860.0 | ||

| Crude protein, g/kg DM2 | 27.7 | 43.3 | 156.3 | 163.6 | 431.0 | 164.3 | 31.5 | 9.7 | 10.0 |

| Neutral detergent fiber, g/kg DM | 753.2 | 767.5 | 310.1 | 556.7 | 287.8 | 479.8 | n.d.3 | 64.4 | 61.8 |

| Acid detergent fiber, g/kg DM | 502.1 | 513.4 | 212.9 | 429.3 | 81.3 | 139.8 | n.d. | 39.5 | 39.1 |

| Gross energy, MJ/kg DM | 16.9 | 16.3 | 17.3 | 17.9 | 18.1 | 17.2 | 14.7 | 16.4 | 16.4 |

| Ash, g/kg DM | 57.3 | 63.5 | 36.3 | 98.2 | 67.4 | 59.6 | 119.0 | 6.16 | 6.26 |

| Total phenols, mg/g | 10.5 | 3.6 | 14.2 | 6.4 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.55 | 0.64 |

| Tannins phenols, mg/g | 0.6 | 0.5 | 8.2 | 1.1 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.28 | 0.32 |

| Condensed tannins, mg/g | 16.5 | 0.0 | 41.3 | 45.9 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.68 | 1.24 |

| Saponins, mg/g | 0.0 | 0.0 | 27.0 | 17.0 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.00 | 3.30 |

| Sorghum halepense | Panicum maximum | Enterolobium cyclocarpum | Gliricidia sepium | Soybean meal | Wheat bran | Cane molasses | Minerals | CaCO3 | |

| Proportion of ingredients, % | |||||||||

| E + G:0 | 42.27 | 30.48 | 0 | 0 | 11.94 | 11.94 | 2.43 | 0.65 | 0.28 |

| E + G: 15 | 37.05 | 26.80 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 2.43 | 0.65 | 0.28 |

1E + G:0 = Control diet; E + G:15 = Diet with E. cyclocarpum 7.5% + G. sepium 7.5%.

2DM = Dry matter.

3n.d. = not determined.

Pods of E. cyclocarpum and foliage of G. sepium were collected in central and east regions of Yucatan (Mexico). The legume was harvested at a regrowth age of 60 d, whereas the grasses hay had 120 d of regrowth. Legume leaves were air-dried and pods were dried at 55 °C for 72 h in a forced air oven. All materials were ground to pass a 2-mm hammer mill (Azteca, Nuevo Leon, Mexico) and properly stored in plastic bags to prevent moisture. Heifers were fed at 8:30 h and the next day, orts were collected and weighed to calculate dry mater intake (DMI) daily. Total fecal production was collected in trays and weighed for 3 consecutive days (2 d of CH4 measurements in open-circuit respiration chambers and 1 additional day in metabolic crates. A subsample (10%) was also taken and dried at 55 °C for 48 h to determine dry mater digestibility (DMD; Schneider and Flatt, 1975) and perform further chemical analyses (described below). Heifers were weighed using a 1-ton scale (Revuelta, DF. Mexico) at the beginning of the experiment and every 17 d to quantify the daily weight gain.

In Situ Incubation

Rumen degradation measurements were conducted through the method proposed by Ørskov et al. (1980) for all the ingredients of the diets. The main ingredients were incubated in the rumen of three crossbred (Bos taurus x Bos indicus) mature cows, each fitted with a plastisol rumen cannula, which were fed 74.9% of Megathyrsus maximus hay and 24.1% of a balanced feed based on soybean meal, ground corn, urea, and cane molasses (11.1% CP and 8.6 MJ ME/kg DM); heifers had free access to fresh water.

Samples (5 g DM) were weighed by triplicate in nylon bags (7 × 14 cm; 53-micron pore size). Bags were removed from the rumen at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h postincubation (for soybean meal); at 72 h for G. sepium, E. cyclocarpum, and wheat bran; and at 96 h for the 2 grasses. Zero-hour degradation bags were soaked in water for 5 min. At the end of the incubation period, bags were dried at 55 °C for 72 h and then weighed. Dry matter degradation kinetics was calculated using the equation, Yt= a + b × (1 − e−c*t) proposed by Ørskov and McDonald (1979), where Y is the percentage of rumen degradability at time (t, h) of incubation. SAS 9.4 nonlinear regression model procedure was used (SAS Institute Inc., 2012) in calculations. For the interpretation of parameters: “a” is the soluble and rapidly degradable fraction, “b” is the slowly degradable fraction, “c” is the constant rate of disappearance (/h), and “t” is the time of incubation (h). Effective rumen degradability (ERD) was calculated as ERD (g/kg DM) = (a + b × c) ÷ (c + Kp), where the parameters a, b, and c had the aforementioned meaning, and “Kp” is the forage passage rate, which is 0.05 per hour for ruminants fed at low levels of production (NRC, 2001).

Methane Production

The Laboratory of Climate Change and Livestock Production at the University of Yucatan has 2 open-circuit respiration chambers to accommodate 1 animal per chamber. Therefore, measurements of CH4 production were planned sequentially to enter the animals into the respiration chambers. Heifers remained inside the chambers for 2 consecutive days, approximately 23 h each day, and 1 h was used to clean up and collect the feces. Protocols detailing the construction and operation of the chambers are described elsewhere in Canul-Solis et al. (2017) and Valencia-Salazar et al. (2018). Respiration chambers were built with metal sheet panels and their dimensions were 300 cm in length, 214 cm in height, and 144 cm in width. Temperature (23 ± 1 °C) and relative humidity (55 ± 10%) within the chamber were continuously monitored. Air was extracted from the chambers at 250 L/min with the help of mass flow meters (Sable Systems International, Las Vegas, NV), and then a sample of chamber air is passed through an infrared CH4 analyzer (MA-10 Sable Systems International, USA) to measure CH4 concentration (Arceo-Castillo et al., 2019). Before each CH4 measurement in the chambers, pure nitrogen and CH4: (1,000 ppm; Praxair Industrial Gases, Inc., Mexico) were used for zeroing and calibrating the CH analyzer, respectively. At the beginning of the experiment, high-purity methane (99.997%; Praxair Industrial Gases, Inc., Mexico) was injected from a cylinder into the chambers to assess recovery rates which ranged between 97% and 102%.

Rumen Fermentation Parameters and DNA Quantification

One day after each CH4 measurement, approximately 1 liter of ruminal fluid was aspirated from heifers 4 h after feeding using an oesophageal tube, to measure pH, and to quantify volatile fatty acids (VFA) and microbial populations. Ruminal fluid was immediately filtered through sterile gauze and the pH was measured (Hannah Instruments, Woonsocket, USA). To determine VFA concentration, 4 mL of ruminal fluid were taken and 1 mL of a 25% of metaphosphoric acid solution was added. The mixture was kept at −20 °C for further analysis.

Another subsample (100 mL) was frozen at −20 °C to determine microbial population. The extraction method was based upon the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) adsorption onto silica without use of phenol, ethanol precipitation, or a cesium chloride gradient, as described by Rojas-Herrera et al. (2008). The procedure was carried out at the Biotechnology Laboratory of the Faculty of Chemical Engineering at UADY, Mexico, using 1 mL of ruminal fluid. Then, the samples were preserved at −20 °C for further analysis at the Molecular and Environmental Biology Laboratory at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Colombia. DNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). After DNA was extracted, a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was conducted to quantify the abundance of total bacteria, total methanogens (16S), and total protozoa (18S). The absolute quantities of each microorganism were determined using standards. Standard curves for each primer set were created using serial dilutions of plasmid DNA of each microbial group. Standards were obtained cloning fragments of the plasmid using the pGEM-T Easy Vector, System I kit (Promega, Madison, WI), followed by transformation of Escherichia coli competent cells. Quantification of samples was performed on a Rotor-Gene Q (QIAGEN, MD) including 3 replicates and a negative control (without template DNA) in every run. Each qPCR reaction mixture (20 μL of final volume) contained 10 μL of SYBR Green (QIAGEN, MD), 0.5 μM of each primer, 20 ng of DNA samples at a concentration of 20 ng, plus 6 μL of ultrapure water. The oligonucleotide primers used and annealing temperature conditions by qPCR amplification are described in Table 2. Estimation of copy numbers for the samples was obtained from the linear relationship between the threshold amplification and the logarithm of 16S or 18S DNA copy numbers from the standard (r2 0.998, with a primer efficiency of approximately 97.8 ± 2%, and a slope value of 3.4). Copy numbers for each sample were calculated using the equation developed by Faseleh et al. (2013) and the absolute abundance was expressed as the Log of copies/mL of the culture sample.

Table 2.

Specific primers used for qRT-PCR

| Organisms | Sequences, 5′–3′ | Annealing, °C | Amplicon size, bp | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bacteria | F: ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAG R: GACTACCAGGGTATCTAATCC | 57 | 552 | Stevenson and Weimer (2007) |

| Methanogenic archaea | F: GGATTAGATACCCSGGTAGT R: GTTGARTCCAATTAAACCGCA | 60 | 173 | Hook et al. (2009) |

| Total protozoa | F: GCTTTCGWTGGTAGTGTATT R: CTTGCCCTCYAATCGTWCT | 55 | 237 | Sylvester et al. (2004) |

Chemical Analysis

Chemical analyses were carried out on samples of ingredients, orts, and collected feces. In addition, DM of ingredients was monitored every week to make sure the variation of this parameter would not exceed 3% throughout the whole experiment. Sample DM was calculated as the difference between fresh weight and final weight after being dried at 55 °C for 48 h in a forced air oven. Samples were ground to pass a 1-mm screen in a Wiley mill. Ash and CP were obtained in accordance with methods 942.05 (AOAC, 2005) and 984.14 (AOAC, 1990; CP = N × 6.25; Kjeldahl AN 3001 FOSS). Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) content was determined using the method proposed by Goering and Van Soest (1970), adapted to an Ankom Fibre Analyzer AN 3805 (Ankom Technology Corp. USA). Gross energy (GE) was determined in accordance with ISO 9831:1998 specifications. Total phenolic and tannin contents were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu’s method (Makkar 2003); condensed tannins were measured using the proanthocyanidins method (Porter et al., 1986) with butanol–HCl reagent. Content of saponins was determined through the method proposed by Oleszek (1990) (haemolytic micro-method test). VFA proportions were quantified using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Shimadzu series 20A) equipped with an ultra-violet/visible (UV/Vis) detector (SPD-20AV) and a chromatography column (BIO-RAD Aminex HPX-87H. Dimensions: 300 × 7.8 mm). HPLC conditions consisted of a mobile phase with H2SO4 0.005 M, oven temperature of 50 °C, with a flow of 0.7 mL/min, detector wave length of 210 nm, and a sample injection volume of 20 μL. Results were determined using a commercial standard curve for acetic, propionic, butyric, and isobutyric acids. All measurements and calculations were performed at the Forage Quality and Animal Nutrition Laboratory of CIAT, Colombia.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the effect of treatments and time on feed intake, apparent digestibility, VFA’s, pH, CH4 production, rumen microbial population, and weight gain, the PROC MIXED procedure of SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2012) was used. Mean separation was made using the Tukey test with an alpha of 0.05. The model is described below:

where Yijk is the response of subject j under ration i, during time k; μ is the population mean; δi is the effect of the ith diet (i = E + G:0 and E + G:15); ῑk is the effect of the kth time (k = 1…, 5); (δ*ῑ)ik is the interaction between ith diet and kth time; βji is the effect of the jth heifer (k = 1, …, 4) into diets; and eijk is the experimental error.

A completely randomized design was used to determinate the differences between groups (groups 1 and 2) under the same control diet in the first phase:

where Yij is the response of subject j (j = 1...4) under group i, μ is the population mean, δi is the effect of the ith group (i = 1 and 2), and eij is the experimental error.

RESULTS

Experimental Diets

Diets fed were similar in nutrient, ADF, GE, and ash contents. The main difference between diets was the content of CT and saponins supplied by E. cyclocarpum pods and G. sepium foliage. This diet had also higher CP and lower NDF content.

Intake and Apparent Digestibility

Average DMI per animal was 6.0 kg DMI/d in the first phase (P = 0.131); this is 0.3 kg DMI/d less than during the following 80 d, where there was a difference in time (P = 0.01), but not between treatments (P = 0.121; Table 3; Figure 2a). In the first 14 d (phase 0), CP, NDF, ADF, and ash intake did not differ between groups (P ≥ 0.073). However, CP intake in the diet containing E. cyclocarpum mixed with G. sepium was 0.3 g/kg DM greater than with the control diet in phases 1 to 5. Moreover, CT and saponin content in the diet supplemented with the legume and the pods had 43 and 22 more g/d, respectively, than the tropical grass-based diet. All the nutrients ingested by the heifers showed differences in time (P ≤ 0.003).

Table 3.

Nutrient and energy intake and digestibility of heifers fed (long-term) with and without Gliricidia sepium mixed with Enterolobium cyclocarpum

| Items | Phase 0 | Phases 1 to 5 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E + G:0 | E + G:0 | SEM | P | E + G:0 | E + G:15 | SEM1 | P | |||

| Diet2 | Time | D*T3 | ||||||||

| ADG, g/d | 129.75 | 116.75 | 50.76 | 0.731 | 354.92 | 395.24 | 46.94 | 0.598 | 0.018 | 0.383 |

| Intake | ||||||||||

| DM, kg/d | 5.81 | 6.25 | 0.36 | 0.135 | 6.11 | 6.62 | 0.20 | 0.121 | 0.001 | 0.031 |

| OM, kg/d | 5.46 | 5.87 | 0.33 | 0.132 | 5.73 | 5.20 | 0.19 | 0.121 | 0.001 | 0.036 |

| CP, g/d | 586 | 605 | 37.2 | 0.494 | 595b | 670a | 19.2 | 0.031 | 0.003 | 0.458 |

| NDF, kg/d | 3.68 | 4.02 | 0.22 | 0.091 | 3.92 | 4.07 | 0.13 | 0.484 | 0.002 | 0.023 |

| ADF, kg/d | 2.26 | 2.47 | 0.14 | 0.073 | 2.40 | 2.57 | 0.08 | 0.198 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| Condensed tannins, g/d | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00b | 43.22a | 0.15 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Saponins, g/d | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00b | 21.81a | 0.08 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Apparent nutrient digestibility, g/kg | ||||||||||

| DM | 498.8 | 505.5 | 24.9 | 0.722 | 512.1 | 531.7 | 7. 25 | 0.086 | 0.198 | 0.412 |

| OM | 520.9 | 527.4 | 23.8 | 0.713 | 537.2 | 548.8 | 6.52 | 0.267 | 0.239 | 0.201 |

| CP | 619.9 | 625.4 | 18.7 | 0.691 | 627.8a | 606.8b | 5.68 | 0.039 | 0.197 | 0.052 |

| NDF | 494.7 | 504.3 | 25.2 | 0.613 | 517.5 | 504.6 | 6.71 | 0.223 | 0.112 | 0.043 |

| ADF | 448.0 | 451.1 | 29.3 | 0.896 | 472.4 | 461.8 | 7.26 | 0.342 | 0.094 | 0.023 |

| Digestible intake | ||||||||||

| OM, kg/d | 2.85 | 3.10 | 0.23 | 0.187 | 3.08 | 3.40 | 0.13 | 0.136 | 0.157 | 0.065 |

| CP, g/d | 366.7 | 375.3 | 27.5 | 0.670 | 372.9 | 406.1 | 14.7 | 0.161 | 0.117 | 0.016 |

| NDF, kg/d | 1.87 | 1.99 | 0.15 | 0.313 | 2.04 | 2.05 | 0.09 | 0.907 | 0.045 | 0.005 |

| ADF, kg/d | 1.01 | 1.12 | 0.10 | 0.206 | 1.14 | 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.545 | 0.058 | 0.003 |

| Energy intake, MJ/d | ||||||||||

| Gross Energy | 94.89 | 102.21 | 5.76 | 0.123 | 99.84 | 108.49 | 3.21 | 0.107 | 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Digestible energy | 47.21 | 50.58 | 4.00 | 0.283 | 51.40 | 56.20 | 2.31 | 0.175 | 0.282 | 0.061 |

a,bMeans in the same column with different letters are statistically different according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

1SE = standard error.

2E + G:0 = Control diet; E + G:15 = Diet with E. cyclocarpum 7.5% + G. sepium 7.5%.

3D*T = Interaction of Diet and Time.

ADG = average daily gain; DM = dry matter; OM = organic matter; CP = crude protein; NDF = neutral detergent fiber; ADF = acid detergent fiber.

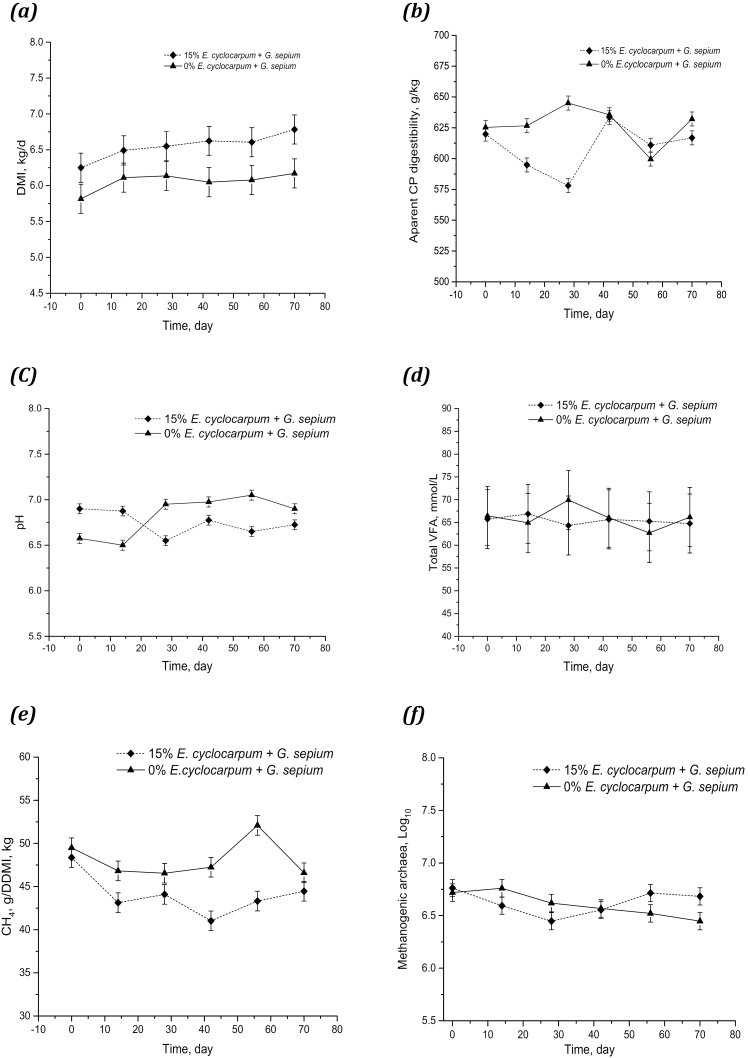

Figure 2.

(a) Mean DMI (kg/d), (b) apparent CP digestibility (g/kg), (c) pH, (d) total VFA (mmol/L), (e) CH4 (g)/digestible dry-matter intake (DDMI) (kg), (f) methanogenic archaea (Log10) averaged over the treatment period from crossbred heifers fed with or without 15% of Enterolobium cyclocarpum mixed with Gliricidia sepium.

In this study, DMD and apparent digestibility of Organic Matter (OMD) averaged 512 and 534 g/kg DM, respectively. These parameters did not differ between groups in phase 0, treatments (with and without legume mixed with pods), nor in the subsequent five phases (P ≥ 0.086). CP digestibility (DCP) was reduced by 21 g/kg DM when heifers were supplemented with E. cyclocarpum mixed with G. sepium (P = 0.039; Figure 2b). There was an interaction between time and treatment in NDF and ADF digestibility (DNDF and DADF, respectively), as well as in the total digestible CP, NDF, and ADF intake and gross energy intake (P ≤ 0.043). Furthermore, over time, items such as digestible NDF intake and gross energy intake differed with time (P ≤ 0.045).

In Situ Degradation

Ingredient ruminal degradations showed that E. cyclocarpum pods had the greatest rapidly degradable fraction values, whereas grasses were approximately 500 g/kg DM lower (623 vs. 130 g/kg DM; P = 0.001; Table 4). When calculating the potentially degradable fraction (a + b), it was observed that soybean meal, E. cyclocarpum, and wheat bran showed the greatest values, contrary to those reported for the legumes and 2 grass species (P = 0.001). Passage rate ranged between 0.2 and 23.7, whereas the rate of degradation per hour ranged between 0.2 and 1.18 (P = 0.001). Soybean meal had an effective rumen degradation (991 g/kg DM) greater than B. brizantha, G. sepium, and S. halepense (460 g/kg DM in average; P = 0.001).

Table 4.

Rumen DM degradation (g/kg DM) of different feed components

| Items | Ingredients | SE | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean meal | Wheat bran | Enterolobium cyclocarpum | Gliricidia sepium | Brachiaria brizantha | S. halepense | |||

| a | 542.0b | 475.6c | 623.3a | 301.9d | 129.8e | 142.5e | 16.4 | 0.001 |

| b | 449.1ab | 317.2c | 247.4c | 336.0bc | 278.9c | 466.9a | 41.7 | 0.001 |

| c | 1.80ab | 1.11ab | 0.63ab | 0.23bc | 0.16bc | 1.12ab | 0.42 | 0.001 |

| a+b | 991.1a | 792.9b | 871.2ab | 637.9c | 408.7d | 609.4c | 51.0 | 0.001 |

| Kp | 19.8b | 1.12d | 0.71d | 23.7a | 14.1c | 0.24d | 1.31 | 0.001 |

| ERD | 990.8a | 791.4b | 856.3 ab | 479.8c | 369.1c | 528.3c | 52.6 | 0.001 |

a,b,c,d,eMeans in the same column with different letters are statistically different according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

a = very rapidly degradable fraction; b = slowly degradable fraction; a + b = degradation potential; Kp = rate of passage; c = constant rate of degradation (per hour); ERD = effective degradability expected at a rate of rumen outflow of 0.05/h.

Ruminal Fermentation Parameters

Rumen pH ranged between 6.58 and 6.97 without difference between animals in phase 0 (P = 0.081), or between response variables, treatments, or in the subsequent 5 phases (P ≥ 0.06; Table 5). However, between diet and time there was an interaction (P = 0.001; Figure 2c). Molar proportions of acetic, propionic, and butyric acids averaged 61.0, 19.4, and 9.8 mmol/100 mol, respectively. These values were similar throughout the whole experiment, as well as when including E. cyclocarpum mixed with G. sepium. The same occurred in the acetic: propionic acid ratio (average = 3.2; P ≥ 0.374). Total VFA expressed in relation to DMI or DOMI averaged 12 and 24 (mmol/L)/(kg/d), respectively (P ≥ 0.079).

Table 5.

Concentrations of volatile fatty acids (VFA) and pH in the rumen of heifers fed (long-term) with and without Gliricidia sepium mixed with Enterolobium cyclocarpum

| Items | Phase 0 | Phases 1 to 5 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E + G:0 | E + G:0 | SEM | P | E + G:0 | E + G:15 | SEM1 | P | |||

| Diet2 | Time | D*T3 | ||||||||

| pH | 6.58 | 6.90 | 0.22 | 0.081 | 6.87 | 6.72 | 0.05 | 0.060 | 0.193 | 0.001 |

| Total VFA, mmol/L | 72.25 | 71.10 | 4.73 | 0.648 | 73.34 | 70.97 | 6.45 | 0.882 | 0.094 | 0.967 |

| Acetic acid, mmol/100 mol | 65.72 | 65.37 | 1.70 | 0.673 | 60.88 | 60.97 | 3.97 | 0.987 | 0.082 | 0.991 |

| Propionic acid, mmol/100 mol | 20.58 | 20.35 | 2.72 | 0.588 | 19.28 | 19.51 | 1.25 | 0.898 | 0.109 | 0.964 |

| Butyric acid, mmol/100 mol | 10.00 | 10.53 | 7.80 | 0.389 | 10.15 | 9.489 | 0.46 | 0.347 | 0.197 | 0.722 |

| Iso-acids, mmol/100 mol | 3.725 | 3.775 | 8.30 | 0.829 | 4.029 | 4.062 | 0.12 | 0.854 | 0.495 | 0.392 |

| Acetic:propionic acid ratio | 3.200 | 3.175 | 3.79 | 0.779 | 3.184 | 3.289 | 0.09 | 0.982 | 0.374 | 0.591 |

| Total VFA, mmol/L/ DMI, kg/d | 11.56 | 12.49 | 0.87 | 0.221 | 12.05 | 11.95 | 0.45 | 0.874 | 0.505 | 0.409 |

| Total VFA, mmol/L/ DOMI, kg/d | 25.55 | 23.23 | 1.90 | 0.151 | 24.55 | 23.23 | 0.94 | 0.216 | 0.313 | 0.079 |

1SE = standard error.

2E + G:0 = Control diet; E + G:15 = Diet with E. cyclocarpum 7.5% + G. sepium 7.5%.

3D*T = Interaction of Diet and Time

DMI = dry matter intake; DOMI = digestible organic-matter intake.

Methane Production

Methane production per heifer ranged between 140 and 149 g/d throughout the whole experiment (Table 6). Methane production, expressed in relation to DM, digestible dry-matter intake (DDMI), and DCP intake, was lower in heifers fed with E + G:15 (P ≤ 0.033) but without differences over time (P ≥ 0.2698; Figure 2e). Percent gross energy loss as methane gas (Ym) with grass-only diets (from phases 0 to 5) was above 8.1%, whereas when feeding heifers with the alternate supplementation, Ym values of 7.59% (P = 0.0163) were observed. The largest difference between diets was observed when projecting annual CH4 production corrected by weight gain, it was reduced by 38% when animals were fed E + G:15–0.4 vs. 0.65 kg CH4/kg ADG, respectively (P = 0.001). These differences remained over the time period measured (P = 0.5780).

Table 6.

Enteric CH4 production in heifers fed (long-term) with and without Gliricidia sepium mixed with Enterolobium cyclocarpum

| Items | Phase 0 | Phases 1 to 5 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E + G:0 | E + G:0 | SEM | P | E + G:0 | E + G:15 | SEM1 | P | |||

| Diet2 | Time | D*T3 | ||||||||

| CH4, g/d | 140.3 | 149.3 | 7.84 | 0.1550 | 145.99 | 147.78 | 3.02 | 0.6319 | 0.2662 | 0.4407 |

| CH4, g/kg DMI | 23.89 | 24.15 | 0.56 | 0.5532 | 23.95a | 23.32b | 0.33 | 0.0166 | 0.8858 | 0.6827 |

| CH4, g/kg DDMI | 47.36 | 48.52 | 2.93 | 0.5991 | 47.01a | 42.08b | 1.14 | 0.0258 | 0.2698 | 0.2323 |

| CH4, g/kg DCP | 383.44 | 396.34 | 15.0 | 0.2013 | 392.3a | 361.4b | 8.50 | 0.033 | 0.4143 | 0.2235 |

| CH4, g/kg DNDF | 75.17 | 75.51 | 4.77 | 0.9231 | 73.03 | 71.48 | 1.89 | 0.6901 | 0.0974 | 0.2019 |

| CH4, g/kg DADF | 134.94 | 139.39 | 10.5 | 0.5728 | 131.24 | 123.24 | 3.71 | 0.2457 | 0.0577 | 0.1891 |

| Energy loss as CH4, % GE | 8.13 | 8.21 | 0.19 | 0.5621 | 8.15 a | 7.59b | 0.11 | 0.0163 | 0.8863 | 0.6828 |

| CH4, kg/kg ADG∙yr | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.1439 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.0001 | 0.5780 | 0.6391 |

a,bMeans in the same column and item with different letters are statistically different according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

1SE = standard error.

2E + G:0 = Control diet; E + G:15 = Diet with E. cyclocarpum 7.5% + G. sepium 7.5%.

3D*T = Interaction of Diet and Time.

DMI = dry matter intake; DDMI = digestible dry-matter intake; DCP = digestible crude protein; DNDF = digestible neutral detergent fiber; DADF = digestible acid detergent fiber; GE = gross energy.

DNA Quantification

Table 7 shows the quantification of the ruminal microbial population. The copy number of total bacterial, protozoan, and methanogenic archaeal replicates was 9.6, 7.3, and 6.6 [log10], respectively. These microorganisms were not affected by the incorporation of the legume and the pods into the diet; moreover, this response remained over time (P ≥ 0.1954; Figure 2f) from the initial phase.

Table 7.

Total population of bacteria, protozoa, and archaea (copy number/mL ruminal fluid) in crossbred heifers fed (long-term) with and without Gliricidia sepium mixed with Enterolobium cyclocarpum

| Rumen microbes, copy number/mL | Phase 0 | Phases 1 to 5 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E + G:0 | E + G:0 | SEM | P | E + G:0 | E + G:15 | SEM1 | P | |||

| Diet2 | Time | D*T3 | ||||||||

| Total bacteria [log10] | 9.59 | 9.46 | 0.26 | 0.603 | 9.50 | 9.59 | 0.08 | 0.610 | 0.812 | 0.662 |

| Total protozoa [log10] | 7.48 | 7.43 | 0.24 | 0.195 | 7.25 | 7.21 | 0.06 | 0.730 | 0.901 | 0.692 |

| Methanogenic archaea [log10] | 6.72 | 6.76 | 0.28 | 0.751 | 6.62 | 6.59 | 0.08 | 0.873 | 0.831 | 0.655 |

| Relation archaea:bacteria | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.356 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.685 | 0.740 | 0.668 |

1SE = standard error.

2E + G:0 = Control diet; E + G:15 = Diet with E. cyclocarpum 7.5% + G. sepium 7.5%.

3D*T = Interaction of Diet and Time.

DISCUSSION

This study shows the differences between tropical grasses and legume or pods when used in diets for cattle. The main contrasts were observed in parameters related to CP, NDF, and secondary compounds. Condenses tannins and saponins values obtained in this study are similar to those previously reported for the E. cyclocarpum pods and G. sepium legume by other authors (Seresinhe et al., 2012; Piñeiro et al., 2013; Archimède et al., 2016; Albores-Moreno et al., 2017). In the literature, these chemical compounds (CP, CT, and saponins) are directly and indirectly related to rumen fermentation, CH4 production, and microbial population (Patra and Saxena, 2009; Hammond et al., 2015).

Dry matter intake was similar in both treatments, possibly because CT and total saponins contents in the diet did not exceed 5%, as this could negatively affect palatability of the diet (Waghorn, 2008). Pods of E. cyclocarpum have a high-soluble carbohydrate fraction and low-fiber content which could have a positive effect on feed intake (Martin et al., 2010; Kahn et al., 2015). However, this was not evidenced in the current study possibly due to the low level of inclusion of this substrate in the diet. Dry matter intake and nutrient intake differed in time; this could be because during the first phase, heifers had to adapt to the change in diet, due to the inclusion of E. cyclocarpum and G. sepium. Authors such as Grant et al. (2015) and Machado et al. (2016) concluded that 7 to 14 d are required to stabilize voluntary intake in cattle fed tropical diets. Nonetheless, the intake behavior and feed selectivity depend on factors specific to animals, social factors, and habitat conditions, as well as to feed characteristics and diet composition (energy density, CP, and fiber contents), among others (Tarazona et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2015).

There are several factors which affect feed digestibility (Schneider and Flatt, 1975). For instance, Makkar et al. (1995) argued that when CT and saponins are available in the same diet, they may have an additive effect on the reduction in feed digestibility. This was not observed in the present study, since DM and OM digestibilities were similar between treatments. Additionally, Kahn et al. (2015) stated that DDMI is closely related to feed rumen degradability and passage rates, which in turn are associated with NDF content in the diet. This was demonstrated by Seresinhe et al. (2012), who found that including E. cyclocarpum increased digestibility due to the soluble carbohydrate content. It is feasible to expect such a result when pods intake is higher, as this feedstuff showed the highest values in rapidly and potentially degradable fractions in the rumen, as well as in effective degradability (a, a + b, and ERD, respectively).

Crude protein digestibility was reduced when heifers were fed E. cyclocarpum pods and the legume G. sepium. This could be due to the presence of tannins in the diet, which may have reduced microbial degradability of dietary CP in the rumen, thus increasing the passage of CP (low degradable) to the small intestine and rendering the amino acids available for absorption (Patra and Saxena, 2009). As discussed above, feed intake of heifers differed in terms of nutritional compounds during the transition phase from a control to a supplemented diet; this had an effect on fiber digestibility (ADF and NDF). Furthermore, the low dose of antinutritional compounds fed to the animals did not have a negative effect on Gram positive bacteria (Ruminococcus albus and R. flavefaciens) and fungi with a fibrolytic role in carbohydrate degradation in the rumen (Wina et al., 2006; Rira et al., 2015).

Enteric CH4 production values fall within the range reported for cattle fed in tropical production systems (20 to 160 g CH4/d; Molina et al., 2016; Ku-Vera et al., 2018; Valencia-Salazar et al., 2018). Methane production (g/kg DMI, g/kg DDMI, or g/kg DCP) showed a reduction between 2.6% and 10.5% when animals were fed E. cyclocarpum mixed with G. sepium; these differences were maintained over time. Methane production depends on factors such as level of feed intake and diet composition and digestibility (Pinares-Patiño et al., 2011; Hristov et al., 2013; Ramin and Huhtanen, 2013). Huhtanen et al. (2016) found that for every additional hour of fermentation in the rumen, production of CH4 increases by 0.37 and 0.33 g CH4/kg DMI in cows and sheep, respectively. In addition, Cabezas-García et al. (2017) argued that passage rate affecting DMI and microbial nitrogen efficiency is closely related to CH4 emission variation among animals. According to Hess et al. (2006), reduction of CH4 per unit of fermented nutrient comes from the effect of tannins reducing nutrient degradation in the rumen.

The loss of dietary gross energy as CH4 with the control diet was higher than for the diet with alternate supplementation (8.1% vs. 7.6% GE). These values are within the range reported by authors such as Kennedy and Charmley (2012), Richmond et al. (2015), Kaewpila and Sommart (2016), and Molina et al. (2016) for cattle fed improved or native tropical grasses, including or not including legumes species. Annual CH4 projection corrected by weight gain was reduced when animals were fed E. cyclocarpum mixed with G. sepium. These findings are consistent with those of Warner et al. (2017) who stated that reducing the nutritional quality increased CH4 emission intensity (g CH4/kg of fat- and protein-corrected milk) by 28%. This is due to the fact that when increasing animal performance, the energy requirements for maintenance are lowered in relation to the total energy requirements, thus reducing the energy demand per additional unit of product (Clark et al., 2013). The relationship between CH4 emission and animal productivity is important when ruminants provide high-quality food for humans (Waghorn and Hegarty, 2011).

Despite the fact that there were no differences between treatments regarding the concentration of VFA’s in the rumen that could help interpret the results obtained in CH4 reduction, it would be expected that hydrogen sinks (i.e., propionate) would increase, whereas the hydrogen providers, like that with an acetate or butyrate type of fermentation, would be reduced (Martin et al., 2010), due to a decrease in rumen pH that favors propionate producing bacteria, but inhibits other microorganisms (Spanghero et al., 2008). On this subject, Palarea-Albaladejo et al. (2017) asserted that the VFA balance ([acetate plus butyrate]/propionate) describes better their contribution to CH4 production (g/kg DMI). However, Robinson et al. (2010) argue that VFA concentrations are poorly associated with daily CH4 production, since these proportions reflect the balance between production and absorption rates, which depend on other factors, such as intake level, ruminal volume, and osmolarity in the rumen. All pH values fell within the normal range reported in the literature (6.8 on average; Van Kessel and Russell, 1996; Shaani et al., 2017) and they did not change when G. sepium mixed with E. cyclocarpum were incorporated. According to Boda et al. (2012), under low pH conditions, saponins have a more pronounced effect on microbial populations and, indirectly, on methane production.

The copy number of total bacterial and methanogenic archaeal replicates was not affected by the incorporation of legumes species and pods into the diet. In agreement with the findings of Navas-Camacho et al. (1993), Hess et al. (2003), and Soliva et al. (2008), the number of total bacteria was not affected by including E. cyclocarpum or G. sepium in the diets of sheep or lambs, nor in in vitro studies. As for the discrepancy between methane reduction without affecting both populations, Wallace et al. (2014) claimed that both parameters are moderately correlated, probably because there is an intrinsic host effect that remains over time. In addition, it is possible that the reduction in CH4 emissions observed in this study by the treatment incorporating E. cyclocarpum mixed with G. sepium was not due to the effect of tannins and saponins on the quantity of microorganisms, but probably due to the inhibition of methanogenic activity, as described by Guo et al. (2008), who argued that the expression of the methyl-coenzyme M reductase (mcrA) gene is reduced by the action of saponins. On the other hand, it could be that the effect of these secondary compounds could affect other microbial populations, such as anaerobic fungi, Succinovibrionaceae and Prevotella, which were not measured in this study, but which are associated with methane production (Tapio et al., 2017). Moreover, when these secondary compounds are included in the diet, there is an inverse correlation between ruminal pH and the abundance of the archaea population (r = −0.95) (Díaz-Carrasco et al., 2017) due to the reduction of available hydrogen caused by a decrease and/or lower activity of cellulolytic bacteria (Brossard et al., 2004), thus reducing rumen CH4 emissions. However, Hünerberg et al. (2015) claimed that methanogens can adapt to a lower pH to produce methane; therefore, both variables (pH and g CH4/kg DMI) are slightly correlated. Additionally, it is possible that no variations in microbial populations between treatments were observed because of the technique used to obtain ruminal fluid (oesophageal tube), since according to Henderson et al. (2013) the abundance of one of the predominant CH4 producers (Methanobrevibacter) varies depending on whether the sample is obtained in the liquid or solid fraction in the rumen. However, the results reported by Hess et al. (2006) and Rira et al. (2015) are in agreement with ours, since they did not find any changes in their quantities when they conducted their research with E. cyclocarpum pods and G. sepium legume.

Similarly, while there was no difference in the quantity of archaea, there was also no difference in protozoa between treatments; both microorganisms are closely related, since archaea are able to develop endosymbiosis with protozoa, because some of them may contain organelles in their membranes, which produce H2 (Patra et al., 2017). In contrast to the findings of this study, Navas-Camacho et al. (1993) reported an increase in the number of protozoa when supplying diets with leaves of E. cyclocarpum (10% DMI), due to an increased availability of slowly degradable protein that these microorganisms use as a source of nitrogen for cell synthesis. Nevertheless, at high doses, they have an adverse effect, as demonstrated by Monforte-Briceño et al. (2005) and Albores-Moreno et al. (2017) who suggested that there is a reduction in the number of protozoa given the sensibility of their cell membrane to the presence of saponins in the diet. When evaluating protozoa over time, Wina et al. (2006) reported that, in the short term, protozoa adapted quickly to saponins, but in the long term, the number or protozoa was reduced, depending on the dose. Other studies state that the effect of saponins on protozoa is transient, as bacteria may degrade saponins into sapogenins, a compound that is not toxic to protozoa (Newbold et al., 1997; Ramos-Morales et al., 2017). It has also been reported that these microorganisms are able to thicken their cell walls or produce extra-cellular polysaccharides around the membrane, thus avoiding its degradation in the rumen (Wina et al., 2006).

In this study, supplementing diets with the pods and legumes did not result in weight gains, perhaps because feed intake was restricted in order to prevent feed selection by cattle. Nonetheless, numerous studies on sheep and cattle have reported weight gains (29 to 89 and 355 to 695 g/d, respectively) by supplying of those legume or pods (Navas-Camacho et al., 1993; Abdulrazak et al., 1997; Mpairwe et al., 1998).

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that the incorporation of 15% of E. cyclocarpum mixed with G. sepium into the diet of crossbred heifers for 80 d reduces methane emissions (g/kg DMI, g/kg DDMI, g/kg DCP, energy loss as CH4, kg/kg ADG/year). However, this reduction in CH4 production cannot be ascribed to the effect of CT and saponins on DM digestibility, variations in the concentration of VFA’s, or microbial populations (total bacteria, protozoa, and archaea). Further research is required to assess changes in population dynamics at the level of Phylum or other microbial populations that could have had an influence on these results and on nitrogen kinetics at the whole animal level.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Footnotes

We thank the Molina Center for Energy and the Environment (La Jolla, CA) for financial support to keep the respiration chambers running and CINVESTAV-IPN, Merida for supplying pure methane cylinders for chamber calibration. We acknowledge PAPIIT-UNAM (project: IV200715) for financial support. We are indebted to the Dairy Unit at FMVZ-UADY for lending the experimental heifers. The senior author thanks CONACYT-Mexico for granting a PhD scholarship at FMVZ-UADY, Mexico. We thank “Rancho Santa Cruz” (Tizimin, Yucatan, Mexico) for the cooperation received during the project. This research was supported by the CGIAR Research Programs of Livestock and CCAFS (Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security) and the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases (GRA) through their CLIFF-GRADS program. CCAFS is carried out with support from CGIAR Fund Donors and through bilateral funding agreements. Thanks to the International Center for Tropical Agriculture for hosting the recipient and to the Government of New Zealand for providing the financial support and LivestockPlus project funded by CCAFS.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abdulrazak S.A., Muinga R.W., Thorpe W., and Ørskov E.R.. 1997. Supplementation with Gliricidia sepium and Leucaena leucocephala on voluntary food intake, digestibility, rumen fermentation and live weight of crossbred steers offered Zea mays stover. Livest. Prod. Sci. 49:53–62. doi:10.1016/S0301-6226(97)00018-3 [Google Scholar]

- Albores-Moreno S., Alayón-Gamboa J. A., Ayala-Burgos A. J., Solorio-Sánchez F. J., Aguilar-Pérez C. F., Olivera-Castillo L., and Ku-Vera J. C.. 2017. Effects of feeding ground pods of enterolobium cyclocarpum jacq. Griseb on dry matter intake, rumen fermentation, and enteric methane production by pelibuey sheep fed tropical grass. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 49:857–866. doi:10.1007/s11250-017-1275-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archimède H., Rira M., Barde D. J., Labirin F., Marie-Magdeleine C., Calif B., Periacarpin F., Fleury J., Rochette Y., Morgavi D. P., et al. 2016. Potential of tannin-rich plants, leucaena leucocephala, glyricidia sepium and manihot esculenta, to reduce enteric methane emissions in sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 100:1149–1158. doi:10.1111/jpn.12423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arceo-Castillo J., Montoya-Flores D., Molina-Botero I.C., Piñeiro-Vázquez A., Aguilar-Pérez C.F., Ayala-Burgos A., Solorio-Sánchez J., Castelán-Ortega O.A., Quintana-Owen P., and Ku-Vera J.C.. 2019. Effect of the volume of pure methane released into respiration chambers on percent recovery rates. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 249:54–61. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.02.001 [Google Scholar]

- Asaolu V.O., Odeyinka S.M., Binuomote R.T., Odedire J.A., and Babayemi, O.J. 2014. Comparative nutritive evaluation of native Panicum maximum, selected tropical browses and their combinations using in vitro gas production technique. A.B.J.N.A. 5(5):198–208. doi:10.5251/abjna.2014.5.5.198.208 [Google Scholar]

- AOAC 2005. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 18th ed. Determination of ash in animal feed: Method 942.05. In: Official Methods of Analysis. Gaithersburg, MD. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC 1990. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 15th ed. Protein (Crude) Determination in Animal Feed: Copper Catalyst Kjeldahl Method. (984.13). In: Official Methods of Analysis; Gaithersburg, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Brossard L., Martin C., Chaucheyras-Durand F., and Michalet-Doreau B.. 2004. Protozoa involved in butyric rather than lactic fermentative pattern during latent acidosis in sheep. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 44:195–206. doi:10.1051/rnd:2004023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas-García E., Krizsan S., Shingfield K., and Huhtanen P.. 2017. Between-cow variation in digestion and rumen fermentation variables associated with methane production. J. Dairy Sci. 100:1–16. doi:10.3168/jds.2016–12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammack K.M., Austin K.J., Lamberson W.L., Conant G.C., and Cunningham H.C.. 2018. Ruminant nutrition symposium: tiny but mighty: the role of the rumen microbes in livestock production. J. Anim. Sci. 96(2):752–770. doi:10.1093/jas/skx053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canul-Solis J.R., Piñeiro A.T., Arceo J.I., Alayón J.A., Ayala A.J., Aguilar C.F., Solorio F.J., Castelán O.A., Lachica M., Quintana P., and Ku J.C.. 2017. Design and construction of low-cost respiration chambers for ruminal methane measurements in ruminants. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 8(2):185–191. doi:10.22319/rmcp.v8i2.4442 [Google Scholar]

- Clark H. 2013. Nutritional and host effects on methanogenesis in the grazing ruminant. Animal. 7(suppl. 1):41–48. doi: 10.1017/S1751731112001875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Carrasco J. M., Cabral C., Redondo L. M., Pin Viso N. D., Colombatto D., Farber M. D., and Fernández Miyakawa M. E.. 2017. Impact of chestnut and quebracho tannins on rumen microbiota of bovines. Biomed Res. Int. 2017:9610810. doi:10.1155/2017/9610810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckard R.J., Grainger C., and de Klein C.A.M.. 2010. Options for the abatement of methane and nitrous oxide from ruminant production: a review. Livest. Sci. 130:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2010.02.010 [Google Scholar]

- Faseleh Jahromi M., Liang J. B., Mohamad R., Goh Y. M., Shokryazdan P., and Ho Y. W.. 2013. Lovastatin-enriched rice straw enhances biomass quality and suppresses ruminal methanogenesis. Biomed Res. Int. 2013:397934. doi:10.1155/2013/397934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goering H.K. and Van Soest P.J.. 1970. Forage fiber analysis. Agricultural Handbook No. 379. US Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grant R.J., Dann H.M., and Woolpert M.E.. 2015. Time required for adaptation of behavior, feed intake and dietary digestibility in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 93(Supplement 3):312–314. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. Q., Liu J. X., Lu Y., Zhu W. Y., Denman S. E., and McSweeney C. S.. 2008. Effect of tea saponin on methanogenesis, microbial community structure and expression of mcra gene, in cultures of rumen micro-organisms. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 47:421–426. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond K. J., Humphries D.J., Crompton L.A., Green C., and Reynolds C.K.. 2015. Methane emissions from cattle: estimates from short-term measurements using a Green Feed system compared with measurements obtained using respiration chambers or sulphur hexafluoride tracer. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 203:41–52. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.02.008 [Google Scholar]

- Henderson G., Cox F., Kittelmann S., Miri V. H., Zethof M., Noel S. J., Waghorn G. C., and Janssen P. H.. 2013. Effect of DNA extraction methods and sampling techniques on the apparent structure of cow and sheep rumen microbial communities. PLoS One. 8:e74787. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess H. D., Kreuzer M., Dıaz T. E., Lascano C. E., Carulla J. E., Soliva C. R., and Machmüller A.. 2003. Saponin rich tropical fruits affect fermentation and methanogenesis in faunated and defaunated rumen fluid. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 109:79–94. doi:10.1016/S0377-8401(03)00212-8 [Google Scholar]

- Hess H. D., Tiemann T.T., Noto F., Carulla J. E., and Kreuzer M.. 2006. Strategic use of tannins as means to limit methane emission from ruminant livestock. Int. Congr. Ser. 1293:164–167. doi:10.1016/j.ics.2006.01.010 [Google Scholar]

- Hook S. E., Northwood K. S., Wright A. D. G., and McBride B. W.. 2009. Long-term monensin supplementation does not significantly affect the quantity or diversity of methanogens in the rumen of the lactating dairy cow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:374–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov A. N., Oh J., Firkins J. L., Dijkstra J., Kebreab E., Waghorn G., Makkar H. P., Adesogan A. T., Yang W., Lee C., et al. 2013. Special topics–mitigation of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from animal operations: I. A review of enteric methane mitigation options. J. Anim. Sci. 91:5045–5069. doi:10.2527/jas.2013-6583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtanen P., Ramin M., and Cabezas-Garcia E.H.. 2016. Effects of ruminal digesta retention time on methane emissions: a modelling approach. Anim. Prod. Sci. 56(3):501–506. doi:10.1071/AN15507 [Google Scholar]

- Hünerberg M., McGinn S. M., Beauchemin K. A., Entz T., Okine E. K., Harstad O. M., and McAllister T. A.. 2015. Impact of ruminal ph on enteric methane emissions. J. Anim. Sci. 93:1760–1766. doi:10.2527/jas.2014-8469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, INEGI 2017. Anuario estadístico y geográfico Yucatán. México: 711 https://www.inegi.org.mx/ (Accessed 1 September 2018.) [Google Scholar]

- ISO 1998. International Organization for Standardization, ISO 9831. Animal feeding stuffs, animal products, and faeces or urine – Determination of gross calorific value – Bomb calorimeter method. Int. Org. Stand., Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Jayanegara A., Goel G., Makkar H.P.S. and Becker K.. 2015. Divergence between purified hydrolysable and condensed tannin effects on methane emission, rumen fermentation and microbial population in vitro. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 209:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.08.002 [Google Scholar]

- Kaewpila C. and Sommart K.. 2016. Development of methane conversion factor models for Zebu beef ca le fed low-quality crop residues and by-products in tropical regions. Ecol. Evol. 6(20):7422–7432. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ece3.2500/epdf (Accessed 1 September 2018.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P. M., and Charmley E.. 2012. Methane yields from Brahman cattle fed tropical grasses and legumes. Anim. Prod. Sci. 52(4):225–239. doi: 10.1071/AN11103 [Google Scholar]

- Khan N. A., Yu P., Ali M., Cone J. W., and Hendriks W. H.. 2015. Nutritive value of maize silage in relation to dairy cow performance and milk quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95:238–252. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku-Vera J.C., Valencia-Salazar S., Piñeiro-Vázquez A.T., Molina-Botero I.C., and Solorio-Sánchez J.. 2018. Determination of methane yield in cattle fed tropical grasses as measured in open-circuit respiration chambers. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 258:3–7. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.01.008 [Google Scholar]

- Littell R. C., Henry P. R., and Ammerman C. B.. 1998. Statistical analysis of repeated measures data using SAS procedures. J. Anim. Sci. 76:1216–1231. doi:10.2527/1998.7641216x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., and Whitman W. B.. 2008. Metabolic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of the methanogenic archaea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1125:171–189. doi:10.1196/annals.1419.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J., Tejada I., Vásquez C., Garza J., and Shimada A.. 2004. Condensed tannins in humid tropical fodder crops and their in vitro biological activity: Part 1. J. Sci. Food Agric. 84:291–294. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1651 [Google Scholar]

- Machado M. G., Detmann E., Mantovani H.C., Valadares-Filho S.C., Bento C.B., Marcondes M.I., and Assunção A. S.. 2016. Evaluation of the length of adaptation period for changeover and crossover nutritional experiments with cattle fed tropical forage-based diets. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 222:132–148. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.10.009 [Google Scholar]

- Makkar H.P. 2003. Measurement of total phenolics and tannins using Folin-Ciocalteu method. In: Makkar H., editor, Quantification of tannins in tree and shrub foliage: A Laboratory Manual. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, Netherlands: p. 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar H.P.S., Blümmel M., and Becker K.. 1995. In vitro effects and interactions of tannins and saponins and fate of tannins in rumen. J. Sci. Food Agric. 69:481–493. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740690413 [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Morgavi D. P., and Doreau M.. 2010. Methane mitigation in ruminants: from microbe to the farm scale. Animal. 4:351–365. doi:10.1017/S1751731109990620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina I.C., Angarita E.A., Mayorga O.L., Chará J., and Barahona-Rosales R.. 2016. Effect of Leucaena leucocephala on methane production of Lucerna heifers fed a diet based on Cynodon plectostachyus. Livest. Sci. 185:24–29. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2016.01.009 [Google Scholar]

- Monforte-Briceño G.E., Sandoval C.A., Ramírez L., and Capetillo C.M.. 2005. Defaunating capacity of tropical fodder trees: Effects of polyethylene glycol and its relationship to in vitro gas production. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 123–124: 313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2005.04.016 [Google Scholar]

- Mpairwe D.R., Sabiiti E.N., and Mugerwa J.S.. 1998. Effect of dried Gliricidia sepium leaf supplement on feed intake, digestibility and nitrogen retention in sheep fed dried KW4 elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum) ad libitum. Agrofor. Syst. 41:139–150. doi:10.1023/A:1006097902270 [Google Scholar]

- Narayan S. 2013. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activities of The leaf extracts of Gliricidia sepium. IJIBCS. 3(3):87–91. http://www.parees.co.in/ijibs.htm (Accessed 4 September 2018.) [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Camacho A., Laredo M.A., Cuesta A., Anzola H., and Leon J.C.. 1993. Effect of supplementation with a tree legume forage on rumen function. LRRD. 5(2). http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd5/2/navas.htm. (Accessed 2 September 2018.) [Google Scholar]

- NRC 2001. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Seventh Revised Edition Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- NRC 2016. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Eighth Revised Edition Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, DC. doi:10.17226/19014 [Google Scholar]

- Newbold C. J., el Hassan S. M., Wang J., Ortega M. E., and Wallace R. J.. 1997. Influence of foliage from African multipurpose trees on activity of rumen protozoa and bacteria. Br. J. Nutr. 78:237–249. doi:10.1079/BJN19970143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleszek W. 1990. Structural specificity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) saponin haemolysis and its impact on 378 two haemolysis based quantification methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 53:477–485. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740530406 [Google Scholar]

- Ørskov E.R., Barnes B.J., and Lukins B.A.. 1980. A note on the effect of different amounts of NaOH application on digestibility by cattle of barley, oats, wheat and maize. J. Agric. Sci. 94(2):271–273. doi:10.1017/S0021859600028847 [Google Scholar]

- Ørskov E.R. and McDonald I.. 1979. The estimation of the protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. 92:449–503. doi:10.1017/S0021859600063048 [Google Scholar]

- Palarea-Albaladejo J., Rooke J. A., Nevison I. M., and Dewhurst R. J.. 2017. Compositional mixed modeling of methane emissions and ruminal volatile fatty acids from individual cattle and multiple experiments. J. Anim. Sci. 95:2467–2480. doi:10.2527/jas.2016.1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A. K., and Saxena J.. 2009. The effect and mode of action of saponins on the microbial populations and fermentation in the rumen and ruminant production. Nutr. Res. Rev. 22:204–219. doi:10.1017/S0954422409990163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A., Park T., Kim M., and Yu Z.. 2017. Rumen methanogens and mitigation of methane emission by anti-methanogenic compounds and substances. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 8:13. doi:10.1186/s40104-017-0145-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinares-Patiño C. S., S. H. Ebrahimi, McEwan J. C., Dodds K. G., Clark H., and Luo D.. 2011. Is rumen retention time implicated in sheep differences in methane emission? NZSAP. 71:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Vázquez A. T., Ayala-Burgos A. J., Chay-Canul A. J., and Ku-Vera J. C.. 2013. Dry matter intake and digestibility of rations replacing concentrates with graded levels of enterolobium cyclocarpum in pelibuey lambs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 45:577–583. doi:10.1007/s11250-012-0262-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Vázquez A.T., Canul-Solis J.R., Jiménez-Ferrer G., Alayón-Gamboa J.A., Chay-Canul A.J., Ayala-Burgos A.J., Aguilar-Pérez C.F., and Ku-Vera J.C.. 2018. Effect of condensed tannins from Leucaena leucocephala on rumen fermentation, methane production and population of rumen protozoa in heifers fed low-quality forage. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 31:1738–1746. doi: 10.5713/ajas.17.0192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzani P., Matute I., Martino G., Arias A., Godoy S., Pereira L., Palma J., and Rengifo M.. 2006. Composición fitoquímica y nutricional de algunos frutos de árboles de interés forrajero de los llanos centrales de Venezuela. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias. 47(2):105–113. Printed version. ISSN 0258-6576. [Google Scholar]

- Porter L., Hrstich L., and Chana B.. 1986. The conversion of procyanidins and prodelphinidins to cyanidin and delphinidin. Phytochemistry. 25:223–230. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94533-3 [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Morales E., de la Fuente G., Nash R. J., Braganca R., Duval S., Bouillon M. E., Lahmann M., and Newbold C. J.. 2017. Improving the antiprotozoal effect of saponins in the rumen by combination with glycosidase inhibiting iminosugars or by modification of their chemical structure. PLoS One. 12:e0184517. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramin M. and Huhtanen P.. 2013. Development of equations for predicting methane emissions from ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 96(4):2476–2. doi:10.3168/jds.2012–6095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond A. S., Wylie A. R., Laidlaw A. S., and Lively F. O.. 2015. Methane emissions from beef cattle grazing on semi-natural upland and improved lowland grasslands. Animal. 9:130–137. doi:10.1017/S1751731114002067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rira M., Morgavi D. P., Archimède H., Marie-Magdeleine C., Popova M., Bousseboua H., and Doreau M.. 2015. Potential of tannin-rich plants for modulating ruminal microbes and ruminal fermentation in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 93:334–347. doi:10.2527/jas.2014-7961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. L., Goopy J., and Hegarty R.S.. 2010. Can rumen methane production be predicted from volatile fatty acid concentrations? Anim. Prod. Sci. 50(6):630–636. doi: 101071/AN09214 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. L., Goopy J. P., Hegarty R. S., and Oddy V. H.. 2015. Comparison of repeated measurements of methane production in sheep over 5 years and a range of measurement protocols. J. Anim. Sci. 93:4637–4650. doi:10.2527/jas.2015-9092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Herrera R., Narváez-Zapata J., Zamudio-Maya M., and Mena-Martínez M. E.. 2008. A simple silica-based method for metagenomic DNA extraction from soil and sediments. Mol. Biotechnol. 40:13–17. doi:10.1007/s12033-008-9061-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute 2012. User’s guide: statistics version 9.4. SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B.H., and Flatt W.P.. 1975. The evaluation of feeds through digestibility experiments. University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Seresinhe T., Madushika S. A., Seresinhe Y., Lal P. K., and Orskov E. R.. 2012. Effects of tropical high tannin non legume and low tannin legume browse mixtures on fermentation parameters and methanogenesis using gas production technique. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 25:1404–1410. doi:10.5713/ajas.2012.12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaani Y., Nikbachat M., Yosef E., Ben-Meir Y., Friedman N., Miron J., and Mizrahi I.. 2017. Effect of wheat hay particle size and replacement of wheat hay with wheat silage on rumen pH, rumination and digestibility in ruminally cannulated non-lactating cows. Animal. 11(3):426–435. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116001865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliva C. R., Zeleke A.B., Clement C., Hess H.D., Fievez V., and Kreuzer M.. 2008. In vitro screening of various tropical foliages, seeds, pods and medicinal plants for low methane and high ammonia generating potentials in the rumen. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 147(1–3):53–71. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.09.009 [Google Scholar]

- Spanghero M., Zanfi C., Fabbro E., Scicutella N., and Camellini C.. 2008. Effect of a blend of essential oils on some end products of in vitro rumen fermentation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 145:364–374. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.05.048 [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson D. M., and Weimer P. J.. 2007. Dominance of prevotella and low abundance of classical ruminal bacterial species in the bovine rumen revealed by relative quantification real-time PCR. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75:165–174. doi:10.1007/s00253-006-0802-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester J. T., Karnati S. K., Yu Z., Morrison M., and Firkins J. L.. 2004. Development of an assay to quantify rumen ciliate protozoal biomass in cows using real-time PCR. J. Nutr. 134:3378–3384. doi:10.1093/jn/134.12.3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapio I., Snelling T. J., Strozzi F., and Wallace R. J.. 2017. The ruminal microbiome associated with methane emissions from ruminant livestock. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 8:7. doi:10.1186/s40104-017-0141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarazona A. M., Ceballos M.C., Naranjo J.F., and Cuartas C.A.. 2012. Factors affecting forage intake and selectivity in ruminants. Rev. Colom. Cienc. Pecua. 25(3): 473–487. Print version ISSN 0120-0690 [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Salado N., Sánchez-Santillán P., Rojas-García A.R., Herrera-Pérez J., and Hernández-Morales J.. 2018. Producción de gases efecto invernadero in vitro de leguminosas arbóreas del trópico seco mexicano. Arch. Zoo. 67(257):55–59. doi: 10.21071/az.v67i257.3491 [Google Scholar]

- Valencia S., Piñeiro A.T., Molina I.C., Lazos F.J., Uuh J.J., Segura M., Ramírez L., Solorio F.J., and Ku-Vera J.C.. 2018. Potential of Samanea saman pod meal for enteric methane mitigation in crossbred heifers fed low-quality tropical grass. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 258:108–116 doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.12.262 [Google Scholar]

- Van Kessel J.A. and Russell J. B.. 1996. The effect of pH on ruminal methanogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 20(4):205–210. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.1996.tb00319.x [Google Scholar]

- Waghorn G. 2008. Beneficial and detrimental effects of dietary condensed tannins for sustainable sheep and goat production – Progress and challenges. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 147(1–3):116–139. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.09.013 [Google Scholar]

- Waghorn G. C. and Hegarty R.S.. 2011. Lowering ruminant methane emissions through improved feed conversion efficiency. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 166:291–301. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.04.019 [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. J., Rooke J. A., Duthie C. A., Hyslop J. J., Ross D. W., McKain N., de Souza S. M., Snelling T. J., Waterhouse A., and Roehe R.. 2014. Archaeal abundance in post-mortem ruminal digesta may help predict methane emissions from beef cattle. Sci. Rep. 4:5892. doi:10.1038/srep05892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D., Bannink A., Hatew B., van Laar H., and Dijkstra J.. 2017. Effects of grass silage quality and level of feed intake on enteric methane production in lactating dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 95:3687–3700. doi:10.2527/jas.2017.1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wina E., Muetzel S., and Becker K.. 2006. The dynamics of major fibrolytic microbes and enzyme activity in the rumen in response to short- and long-term feeding of sapindus rarak saponins. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100:114–122. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]