Abstract

Although n-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) has been shown to efficiently alleviate oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and alter gut microbiota, little attention has been focused on their interactions with placental metabolic status of sows. The effects of NAC on the placental redox status, function, inflammasome, and fecal microbiota in sows were explored to clarify the correlation between the fecal microbiota and placenta. Sows were divided into either the control group or the NAC group which received dietary 500 mg/kg NAC supplementation from day 85 of gestation to delivery. Plasma redox status, placental growth factors, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, fecal microbial metabolites, and communities were evaluated. Compared with the control group, although NAC did not ameliorate reproductive performance of sows (P > 0.05), it significantly improved maternal-placental health, which was accompanied by increased activities of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), decreased level of malondialdehyde (MDA), and lowered expression of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome (P < 0.05). Additionally, NAC significantly increased placental insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and E-cadherin contents (P < 0.05), elevated the expression of genes involved in angiogenesis and amino acids transporters (P < 0.05), and decreased the microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B) and Beclin-1 protein expression (P < 0.05). Furthermore, NAC increased the relative abundances of fecal Prevotella, Clostridium cluster XIVa, and Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale (P < 0.05), which were negatively correlated with placental NLRP3 and positively with solute carrier family 7, member 8 (Slc7a8; P < 0.05). In conclusion, NAC supplementation during late gestation alleviated maternal-placental oxidative stress and inflammatory response, improved placental function, and altered fecal microbial communities.

Keywords: fecal microbiota, n-acetyl-cysteine, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3, placenta, sows

INTRODUCTION

Sows suffer from systemic oxidative stress during pregnancy, which is characterized by placental oxidative stress and poor performances (Berchieri-Ronchi et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2018). The placenta regulates nutritional and hormonal support of the fetus, and also plays an immunomodulatory role (Mor and Kwon, 2015). The NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin-containing protein 3) inflammasome, composed of NLRP3, ASC (an apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain), and caspase-1, represents the first line of the innate immunity (Latz et al., 2013). It could activate caspase-1 to produce interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 in response to cellular stress (Rathinam et al., 2012). Placental active caspase-1 is negatively correlated with gestational age, while activation of NLRP3 inflammasome at term is related to pregnancy complications (Cooper et al., 2016; Gierman et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2018).

Reduction of placental oxidative stress and inflammation has been suggested to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes and improve reproductive performance of sows (Al-Gubory et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2018). N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), known as an anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant agent, has been reported to efficiently reduce inflammatory responses in maternal-fetal interface and improve placental efficiency in rats (Paintlia et al., 2008; Beloosesky et al., 2009). However, information about the effects of NAC on placental oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome at term in sows is unknown.

Gut microbiota are considered as an important part of host metabolism, innate immunity, and pregnancy maintenance. The composition of gut microbiota has been shown to change with the gestational age, and alteration to the microbiota by maternal nutrition has been suggested to relieve oxidative stress and improve sow health (Koren et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2016). Thus, it is promising to study the interactions among the gut microbiota, metabolites, and immunity at the maternal-fetal interface (PrabhuDas et al., 2015; Macpherson et al., 2017). Recently, we reported that NAC positively regulated gut microbiota in weaned piglets (Xu et al., 2014). However, the effect of NAC on the fecal microbiota and placental immunity and their interactions in sows are unknown. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to explore the effects of NAC on the reproductive performance, maternal-placental-fetal redox status, placental function, NLRP3 inflammasome and protein expression, fecal microbial communities, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiment protocol was approved by the guidelines of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animal and Diets

The experiment was conducted in the pig breeding farm (Jinshan District, Shanghai). A total of 16 sows (Landrace × Large White) at day 85 of gestation with same parity (second parity) were selected based on body weight and assigned into 2 groups: the control group (7 sows) and NAC group (9 sows; the basal diet supplemented with 500 mg/kg NAC). Sows had similar back fat thickness between the 2 groups (Control: 15.14 ± 0.51 vs. NAC: 15.33 ± 0.44 mm; P = 0.781), which were determined by the digital back fat indicator (BQT-521, Renco Lean-meater, USA). N-acetyl-cysteine (99.4% purity) was obtained from Bangcheng Chemical Company (Shanghai, China). The dose of NAC was based on our previous study in piglets (Zhu et al., 2013). The sows were kept individually in gestation crates and provided 3-kg diet from days 85 to 107 of gestation (2 feedings, at 0600 and 1300 h). They were then transferred to farrowing pens and provided 2-kg diet from day 108 of gestation to delivery. All the dietary compositions met the National Research Council (NRC 2012) nutrient requirements for gestating sows. The mean temperature was kept at 25 ± 3 °C. The dietary ingredients and nutritional levels are shown in Table 1. All sows had free access to drinking water.

Table 1.

Dietary ingredients and nutritional levels of the basal diets

| days 85 to 107 | day 108 to delivery | |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients, % | ||

| Corn | 35.73 | 41.32 |

| Barley | 30.00 | 25.00 |

| Soybean hull | 5.00 | – |

| Soybean meal | 18.50 | 10.00 |

| Extruded soybean | – | 8.00 |

| Fermented soybean meal | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Soybean oil | 3.00 | 3.50 |

| Beer yeast powder | – | 2.50 |

| Steam fish powder | – | 1.50 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate | 1.30 | 1.40 |

| Limestone | 1.00 | 1.20 |

| NaCl | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| L-Threonine | – | 0.03 |

| L-Lysine HCl | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| Minerals and vitamins premix1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Antioxidant2 | 0.02 | – |

| Mold inhibitor | – | 0.05 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Nutrient levels,3 dry matter | ||

| DE, kcal/kg | 3354 | 3443 |

| ME, kcal/kg | 3217 | 3301 |

| CP, % | 16.74 | 17.52 |

| Either extract, % | 6.44 | 5.10 |

| Crude fiber, % | 5.14 | 3.15 |

| SID4 lysine, % | 0.80 | 0.92 |

| SID methionine + cysteine, % | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| SID threonine, % | 0.51 | 0.56 |

| SID tryptophan, % | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| SID valine, % | 0.73 | 0.70 |

| Calcium, % | 0.86 | 0.92 |

| Total phosphorous, % | 0.51 | 0.52 |

| Available phosphorous, % | 0.26 | 0.30 |

1This mineral and vitamin premix supplied, per kilogram of diet, 8,750 IU retinol, 2,835 IU cholecalciferol, 84 mg α-tocopherol, 5.96 mg menadione, 1.85 mg thiamine, 6.57 mg riboflavin, 37.6 mg niacin, 29.2 mg d-pantothenic acid, 4.2 mg pyridoxine, 0.43 mg D-biotin, 2.5 mg folic acid, 0.04 mg vitamin B12, 500 mg choline chloride, 212 mg Fe as ferrous sulfate monohydrate, 30 mg Cu as copper sulfate pentahydrate, 30 mg Mn as manganese sulfate monohydrate, 144 mg Zn as zinc sulfate monohydrate, 1 mg I as calcium iodate, and 0.3 mg Se as sodium selenite.

2Antioxidant including 66% ethoxyquin.

3Nutrient levels are calculated.

4SID = standardized ileal digestible.

Sample Collection

Maternal blood (10 mL) from the right jugular vein of 6 fasted sows in each group was obtained within 2 h after delivery, with heparin sodium anticoagulant tubes (Jiangsu Yili Medical Instrument, China). The supernatants were collected after centrifuging at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Then, each plasma was divided into 2-mL tubes (Nest Biotechnology, Wuxi, China) and stored immediately in liquid nitrogen. The umbilical cord was tagged with individual threads of different colors when sows were delivering (day 114 ± 1). One piglet with similar body weight from each litter was chosen (n = 6 per group). After the end of each farrowing, the corresponding placental tissues (2 to 4 cm from the cord insertion point) were collected within 15 min (n = 6 per group). Approximately 10 g of tissue were dissected immediately from the central part of each placenta (excluding the calcified area), washed in 0.9% saline solution, and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Fresh placental tissues were immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (A17876, Alfa Aesar, USA) for transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Piglets with similar body weight were anaesthetized by intramuscular injection of 3% sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, P3761, Sigma, USA) and plasma was collected. The plasma (3 mL) was collected within 8 h after all the piglets were born. The delivery time, body weights, the numbers of born alive, stillborn, and mummified were recorded.

The fresh feces from 6 sows per group were collected at day 110 of gestation using sterile 5-mL tubes and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen. Then the samples were transported to the laboratory and stored at −80 °C for later genomic DNA extraction and metabolite analysis.

Oxidative Stress Parameters in Plasma and Placenta

The contents of H2O2, malondialdehyde (MDA) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), and the activities of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in plasma from sows and newborn piglets were measured according to the instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) reported previously (Xu et al., 2014).

Placental tissues were homogenized in 0.9% cold saline solution. The supernatants were collected after centrifuging for 10 min at 3,000 × g at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured according to the instructions of the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (P0010, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The contents of H2O2, nitric oxide (NO), and MDA, and the activities of GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT in placental tissues were also determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China; Xu et al., 2014).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The contents of IL-1β and IL-18 in maternal plasma, and the concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-1 and 2 (IGF-1 and IGF-2), E-cadherin, IL-1β, IL-18, and caspase-1 in the placenta were measured using porcine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Briefly, the plates were coated with corresponding antibodies followed by detection with a horseradish peroxidase-labeled substrate after incubation for 10 min at 37 °C. The plates were then read in a 96-well plate reader (Synergy 2, BioTek, USA) at 450 nm. The quantification of each sample was performed in duplicate. The inter- and intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV), and the detection range of the kits are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The inter- and intra-assay CV, and the detection range of the kits

| Samples | Kits | CV1 | Detection range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-assay | Intra-assay | |||

| Placenta | E-cadherin | 11.45% | 9.85% | 1–400 ng/mL |

| IGF-1 | 12.50% | 10.42% | 3–900 ng/mL | |

| IGF-2 | 12.36% | 10.05% | 5–200 ng/mL | |

| IL-1β | 10.35% | 7.87% | 0.5–200 ng/L | |

| IL-18 | 12.04% | 10.10% | 2–600 ng/L | |

| Caspase-1 | 11.20% | 8.45% | 0.1–30 ng/mL | |

| Plasma | IL-1β | 10.35% | 7.87% | 0.5–200 ng/L |

| IL-18 | 12.04% | 10.10% | 2–600 ng/L |

1CV = coefficient of variation.

Placental RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Real-time qPCR

Placental tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was extracted according to the instructions of the E.Z.N.A total RNA kit I (R6841-01, OMEGA, USA). The concentration of RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop Lite Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). RNA samples with the ratio of A260/280 between 1.8 and 2.0 were considered of high quality. After removal of genomic DNA, the RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (RR047A, Takara, Japan). The real-time quantitative PCR was used to quantify the gene expression with the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system. The reaction was performed in a total volume of 20 μL, including 10 μL of SYBR Green mix, 0.4 μL of Rox Dye II, 6.8 μL of H2O, and 0.4 μL each of forward and reverse primers. Amplification conditions were initial at 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 34 s, and a stepwise increase in the temperature from 60 to 95 °C to obtain the melting curve data. The primers were designed according to the sequences of porcine genes in the NCBI database using the Primer 3.0 software or as described in previous studies (Table 3). β-actin was used as a housekeeping gene to normalize target gene transcript levels. The values in NAC group were expressed as fold change relative to the control value, using the formula 2−(△△Ct), where △△Ct = (Ct Target – Ct β-actin)NAC − (Ct Target − Ct β-actin)control.

Table 3.

Primers used in this study

| Item1 | Accession no. | Primer sequence | Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | ||||

| Slc2a1 | KU672521.1 | F: TTCTCCAAACTGGGCAAATC | 204 | This study |

| R: GATGGAGTCCAGGCCAAATA | ||||

| Slc2a3 | KU672523.1 | F: CTCTTGGGCTTCACCATCAT | 159 | This study |

| R: GATGTCCTGAGCCACATCCT | ||||

| Slc7a8 | XM_021099240.1 | F: CAGTCGCTGTGACTTTTGGA | 222 | This study |

| R: TGGAGATGCATGTGAAGAGC | ||||

| Slc38a1 | XM_003355629.4 | F: GAACACTGGAGCAATGCTGA | 190 | This study |

| R: ATAGCCGAGATAGCCCAGGT | ||||

| HIFα | NM_001123124.1 | F: TTACAGCAGCCAGATGATCG | 178 | This study |

| R: TGGTCAGCTGTGGTAATCCA | ||||

| VEGF | JF831364.1 | F: CTACCTCCACCATGCCAAGT | 232 | This study |

| R: ACACTCCAGACCTTCGTCGT | ||||

| IL-1β | NM_214055.1 | F:CCAAAGAGGGACATGGAGAA | 160 | This study |

| R: TTATATCTTGGCGGCCTTTG | ||||

| IL-18 | NM_213997.1 | F: CTGCTGAACCGGAAGACAAT | 194 | This study |

| R: CTCAAACACGGCTTGATGTC | ||||

| Caspase-1 | NM_214162.1 | F: TTTGAAGGACAAACCCAAGG | 150 | This study |

| R: TGGGCTTTCTTAATGGCATC | ||||

| NLRP3 | NM_001256770.2 | F: CAGCACGAACCAGAATCTCA | 152 | This study |

| R: AGCAGCAGTGTGATGTGAGG | ||||

| Slc7a7 | NM_001110421 | F: TTTGTTATGCGGAACTGG | 113 | Liu et al., 2016 |

| R: AAAGGTGATGGCAATGAC | ||||

| Slc7a9 | EU390780 | F: GAACCCAAGACCACAAATC | 180 | Liu et al., 2016 |

| R: ACCCAGTGTCGCAAGAAT | ||||

| Slc38a2 | XM_005664159 | F: TACTTGGTTCTGCTGGTGTCC | 212 | Liu et al., 2016 |

| R:GTTGTGGGCTGTGTAAAGGTG | ||||

| TIMP-1 | NM_213857.1 | F:CCAGCGTTATGAGATCAAGATG | 312 | Menino et al., 1997 |

| R: AGTTTGCAGGGGATGGATG | ||||

| ASC | AB873106.1 | F: ACAACAAACCAGCACTGCAC | 126 | Fu et al., 2016 |

| R: CTGCCTGGTACTGCTCTTCC | ||||

| IL-6 | JQ839263.1 | F: CCAGGAACCCAGCTATGAAC | 142 | Fu et al., 2016 |

| R: CTGCACAGCCTCGACATT | ||||

| IL-8 | AB057440.1 | F: CAGAGCCAGGAAGAGACT | 461 | Fu et al., 2016 |

| R: GACCAGCACAGGAATGAG | ||||

| β-actin | XM_003124280.3 | F: CTGCGGCATCCACGAAACT | 147 | Yin et al., 2015 |

| R: AGGGCCGTGATCTCCTTCTG | ||||

| qPCR bacteria | ||||

| Total bacteria | F: CGGTGAATACGTTCYCGG | 123 | Suzuki et al., 2000 | |

| R: GGWTACCTTGTTACGACTT | ||||

| Clostridium cluster IV | F: GCACAAGCAGTGGAGT | 239 | Matsuki et al., 2004 | |

| R: CTTCCTCCGTTTTGTCAA | ||||

| Clostridium cluster XIVa | F: AAATGACGGTACCTGACTAA | 440 | Matsuki et al., 2004 | |

| R: CTTTGAGTTTCATTCTTGCGAA | ||||

| Lactobacillus | F: AGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCA | 341 | Kanno et al., 2009 | |

| R: CACCGCTACACATGGAG | ||||

| Bifidobacterium | F:GATTCTGGCTCAGGATGAACGC | Echarri et al., 2011 | ||

| R: CTGATAGGACGCGACCCCAT | ||||

| Akkermansia muciniphila | F: CAGCACGTGAAGGTGGGGAC | 328 | Everard et al., 2013 | |

| R: CCTTGCGGTTGGCTTCAGAT | ||||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | F: AATTCCGCCTACCTCTGCACT | 248 | Ramirez-Farias et al., 2008 | |

| R: GGAGGAAGAAGGTCTTCGG | ||||

| Bacteroidetes | F: AGCAGCCGCGGTAAT | 184 | Armougom et al., 2009 | |

| R: CTAHGCATTTCACCGCTA | ||||

| Prevotella | F: GGTTCTGAGAGGAAGGTCCCC | 121 | Stevenson et al., 2007 | |

| R: TCCTGCACGCTACTTGGCTG | ||||

| Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale | F: GCGGTRCGGCAAGTCTGA | 80 | Walker et al., 2011 | |

| R: CCTCCGACACTCTAGTMCGAC |

1 Slc = solute carrier family; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; HIFα = hypoxia inducible factor α; TIMP = tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase; IL = interleukin; CAS1 = caspase-1; ASC = an apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; NLRP3 = nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3.

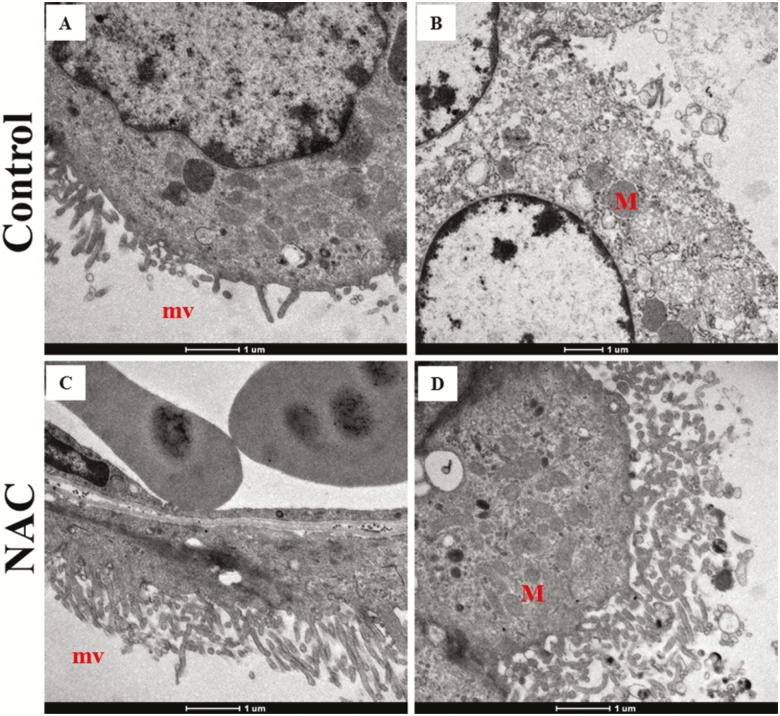

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Fresh placental samples (1 mm3, 1 section per placenta, 3 placentas per group) were immediately collected and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 6 h and washed 3 times with phosphate buffer. Then they were fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide for 2 h and progressively alcohol-dehydrated, embedded, and polymerized for 24 h at 60 °C. Representative sections (60 nm) were made and double stained with 3% uranium and lead (Zhu et al., 2013). Placental ultrastructure was observed through a TEM (Tecnai Spirit G2 BioTWIN, USA).

Western Blot

Western blot analysis was conducted according to our previous study (Luo et al., 2016). Six placentas per group were used for western blot analysis. The placental tissues (0.2 g) were homogenized in 0.5 mL of ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (KGP703-100, Jiangsu KeyGEN BioTECH, China) containing 1 mM of phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Amresco, Shanghai, China) and protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (05892791001, Roche, Germany). After incubation on ice for 30 min, the lysates were centrifuged for 25 min at 12,000 × g, and the supernatants were collected. The protein content was measured using the BCA protein assay kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (P0010, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) were electrophoresed in SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (0.45 μm, Millipore, USA), and then blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder (D8340, Solarbio, Shanghai, China) in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 1.5 h at room temperature. The phospho-extracellular regulated kinases (p-ERK1/2, 1:2,000; #4370), extracellular regulated kinases (ERK1/2, 1:1,000; #9102), β-actin (1:1,000; #4970), phospho-protein kinase B (p-Akt, 1:1,000; #9271), protein kinase B (Akt, 1:1,000; #9272), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR, 1:1,000; #2972), and phosphor-mammalian target of rapamycin (p-mTOR, 1:1,000; #5536) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B) (1:1,000; NB100-2220) and Beclin-1 (1:10,000; NB110-87318) antibodies were purchased from Novus Biologicals (CO, USA). The primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C in 5% skimmed milk powder or bovine serum albumin (0218054950, MP, USA) in TBS-T. The goat anti-rabbit (1:2,000, ab97051; Abcam, UK) or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)-horseradish peroxidase (HRP; 1:2,000, sc-2005; Santa Cruz, USA) secondary antibodies were incubated with the blots for 1.5 h. Image acquisition was performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). Image J software IJ1.46 r (NIH, USA) was used to quantify the density of the specific protein bands.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids

The concentrations of fecal SCFA (including acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate, isobutyrate, and isovalerate) were determined by gas chromatography (Shimadzu GC-2014, Tokyo, Japan) according to our previous study (Luo et al., 2015).

Fecal DNA Isolation and Real-Time qPCR

Fecal DNA was extracted using the DNA extraction kit (DP328-02, TIANGEN, Shanghai) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was dissolved in Tris-EDTA buffer. DNA quantity was determined using the NanoDrop Lite Spectrophotometer. Numbers of total bacteria, Clostridium cluster (IV, XIVa), Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia muciniphila, Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale, Bacteroidetes, Prevotella, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii were quantified using specific primers (Table 3). The abundance of the microbial communities was calculated as a relative value normalized to the total bacteria of the same sample. Data analysis was carried out according to the 2−△Ct (ΔCt = Cttarget − Cttotal bacteria) (Wong et al., 2017).

Statistical Analyses

The relative abundance of bacteria was presented as median and analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Homogeneity of variance was tested for the other measures with a Levene’s test. The data were tested between the 2 groups for significance with an independent sample t-test method, using the statistical software SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data were presented as mean ± SEM. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. A tendency was considered when 0.05 < P < 0.1.

RESULTS

Reproductive Performances

As shown in Table 4, the delivery time, numbers of total born and born alive, litter weight, mean individual weight, birth weight CV, the percentage of stillborn, mummified, and intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) occurrence were not significantly affected (P > 0.05) by maternal NAC supplementation. Of note, the numbers of total born, born alive, and litter weight tended to increase by 9.03%, 8.02%, and 8.43%, respectively, with NAC supplementation.

Table 4.

Effects of maternal NAC supplementation during late gestation on reproductive performance of sows

| Item | Control | NAC | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Litters | 7 | 9 | |

| Delivery time, h | 7.36 ± 0.40 | 8.1± 0.81 | 0.439 |

| Total born, n | 15.29 ± 0.52 | 16.67 ± 0.75 | 0.175 |

| Born alive, n | 14.71 ± 0.57 | 15.89 ± 0.54 | 0.159 |

| Stillborn, % | 2.83 ± 1.35 | 1.11 ± 0.73 | 0.291 |

| Mummified, % | 1.79 ± 1.16 | 1.25 ± 0.83 | 0.702 |

| IUGR1, % | 11.10 ± 3.43 | 8.44 ± 1.41 | 0.620 |

| Litter weight, kg | 21.23 ± 1.18 | 23.02 ± 0.93 | 0.202 |

| Mean individual weight, kg | 1.41 ± 0.07 | 1.42 ± 0.04 | 0.882 |

| Birth weight CV2 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.547 |

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Differences are considered significant at P < 0.05.

1IUGR = intrauterine growth retardation, piglets with a birth weight of less than 1 kg and lower than the lower quartile of litter birth weights (Degroote et al., 2012).

2CV = coefficient of variation.

Oxidative Stress Parameters in Plasma and Placenta

As shown in Table 5, compared with the control group, the content of H2O2 in maternal plasma was lower (P < 0.05) in the NAC group. The content of T-AOC, the activities of GSH-Px, and SOD in plasma was significantly increased (P < 0.05) in the NAC group, whereas the activity of CAT did not differ (P > 0.05). Malondialdehyde, the marker of lipid peroxidation, was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the NAC group than that in the control group.

Table 5.

Effects of maternal NAC supplementation during late gestation on oxidative stress parameters in maternal and neonatal plasma, and placenta

| Item | Control | NAC | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal plasma1 | |||

| H2O2, mmol/L | 58.18 ± 4.13 | 43.81 ± 3.26 | 0.021 |

| T-AOC, units/mL | 5.26 ± 0.38 | 6.59 ± 0.42 | 0.044 |

| GSH-Px, units/mL | 647.24 ± 22.38 | 710.79 ± 13.92 | 0.034 |

| SOD, units/mL | 62.95 ± 6.19 | 79.71 ± 2.50 | 0.031 |

| CAT, units/mL | 2.63 ± 0.52 | 3.09 ± 0.30 | 0.490 |

| MDA, nmol/mL | 2.43 ± 0.13 | 1.95 ± 0.11 | 0.020 |

| Placenta | |||

| H2O2, mmol/g protein | 6.33 ± 0.41 | 5.73 ± 0.54 | 0.392 |

| NO, μmol/g protein | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | 0.003 |

| GSH-Px, units/mg protein | 75.74 ± 2.30 | 87.97 ± 3.18 | 0.015 |

| SOD, units/mg protein | 5.16 ± 0.20 | 6.09 ± 0.30 | 0.022 |

| CAT, units/mg protein | 4.97 ± 0.61 | 4.19 ± 0.43 | 0.318 |

| MDA, nmol/mg protein | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.57 ± 0.07 | 0.017 |

| Neonatal plasma | |||

| H2O2, mmol/L | 3.52 ± 0.93 | 3.76 ± 0.79 | 0.851 |

| GSH-Px, units/mL | 207.38 ± 11.16 | 220.00 ± 19.42 | 0.594 |

| CAT, units/mL | 3.02 ± 0.57 | 3.42 ± 0.45 | 0.613 |

| MDA, nmol/mL | 1.61 ± 0.16 | 1.73 ± 0.52 | 0.838 |

Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

1H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide; NO = nitric oxide; GSH-Px = glutathione peroxidase; SOD = superoxide dismutase; CAT = catalase; T-AOC = total antioxidant capacity; MDA = malondialdehyde.

The concentration of placental H2O2 was not different (P > 0.05) between the 2 groups. Compared with the control group, the level of placental NO was greater (P < 0.05) in the NAC group. The activities of SOD and GSH-Px also significantly (P < 0.05) increased in the NAC group. But the activity of CAT showed no difference (P > 0.05) between the 2 groups. Maternal NAC supplementation significantly (P < 0.05) lowered the placental content of MDA compared with the control.

The oxidative stress parameters in neonatal plasma were also investigated. However, the contents of H2O2 and MDA, and the activities of GSH-Px and CAT did not differ (P > 0.05) between the 2 groups.

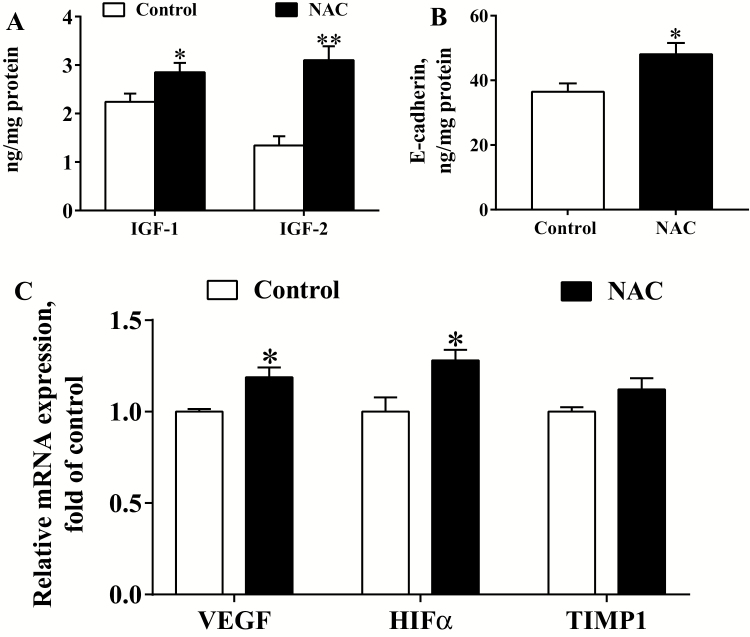

Placental Growth Factors, Angiogenic Factors, and Structural Characteristics

To further explore the effects of NAC on placental function, the placental concentrations of growth factors and expression of angiogenesis-related genes were investigated (Figure 1). Compared with the control, maternal NAC supplementation significantly (P < 0.05) increased the concentrations of placental IGF-1, IGF-2, and E-cadherin (Figure 1A and B). As shown in Figure 1C, the expression of placental vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hypoxia inducible factor α (HIFα) genes was significantly greater (P < 0.05) in the NAC group relative to the control group. But the gene expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) was not significantly different (P > 0.05) between the 2 groups.

Figure 1.

Placental growth factors and gene expressions of angiogenic factors (n = 6). (A) ELISA for IGF-1 and IGF-2 contents, (B) ELISA for E-cadherin content, (C) Gene expression of angiogenic factors. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with the control. IGF = insulin-like growth factor; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; HIFα = hypoxia inducible factor α; TIMP = tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase.

The representative placental structures such as microvilli (A and C) and mitochondria (B and D) between the 2 groups were shown in Figure 2. The morphology of microvilli and swollen mitochondria were improved by NAC supplementation.

Figure 2.

Representative placental structures obtained from transmission electron microscopy (n = 3). (A) Microvilli loss, (B) Swollen mitochondria, (C) Normal microvilli, (D) Normal mitochondrial structure. M = mitochondrial, mv = microvilli.

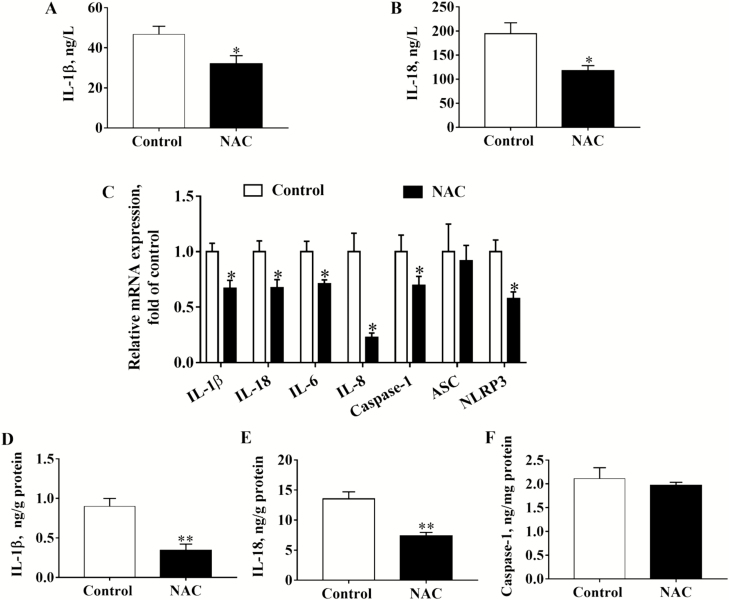

Maternal and Placental Inflammatory Cytokines

Maternal NAC supplementation during late gestation significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the protein contents of IL-1β and IL-18 in sow plasma (Figure 3A and B). As shown in Figure 3C, gene expression of placental inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, IL-8, caspase-1, and NLRP3 was significantly decreased (P < 0.05) by NAC, whereas gene expression of ASC was not affected (P > 0.05). Furthermore, NAC significantly (P < 0.05) reduced protein contents of placental IL-1β and IL-18 (Figure 3D and E). But the concentration of placental caspase-1 was not influenced (P > 0.05) by NAC (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Effects of maternal NAC supplementation on gene and protein expression of inflammatory cytokines in maternal plasma and placenta (n = 6). (A) ELISA for IL-1β in maternal plasma, (B) ELISA for IL-18 in maternal plasma, (C) Gene expressions of placental inflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 inflammasomes, (D) ELISA for placental IL-1β, (E) ELISA for placental IL-18, and (F) ELISA for placental caspase-1. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with the control. IL = interleukin; CAS1 = caspase-1; ASC = an apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; NLRP3 = nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3.

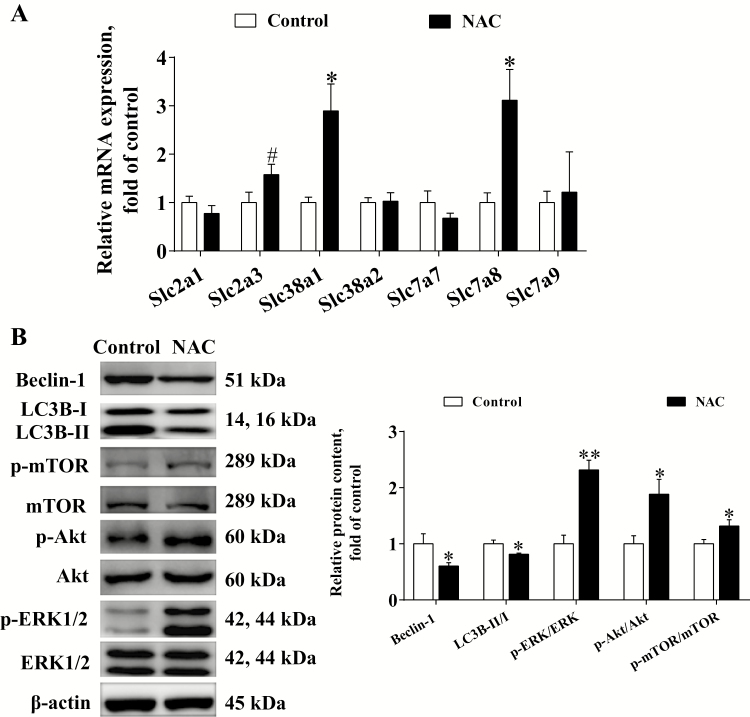

Placental Nutrients Transporters and Autophagy Signaling Pathways

As shown in Figure 4A, compared with the control, maternal NAC supplementation significantly increased (P < 0.05) the gene expression of placental solute carrier (Slc) families Slc38a1 and Slc7a8. N-acetyl-cysteine tended to increase (P < 0.1) the expression of Slc2a3 gene. No significant differences (P > 0.05) in the expression of Slc2a1, Slc38a2, Slc7a7, and Slc7a9 genes were observed between the 2 groups.

Figure 4.

Effects of maternal NAC supplementation on gene expression of placental transporters (A), autophagy protein and signaling pathways (B) during late gestation (n = 6). Data are mean ± SEM. #P < 0.1, *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01 compared with the control. Slc = solute carrier family; LC3B = microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B.

As the increased nutrients transport is often associated with the increase of cell proliferation and decrease of autophagy (Nicklin et al., 2009), the autophagy protein and its regulating pathways were investigated (Figure 4B). The protein expression of Beclin-1 and LC3B was lower (P < 0.05) in the NAC group than in the control group. However, the ratios of p-mTOR/mTOR, p-Akt/Akt, and p-ERK/ERK were greater (P < 0.05) in the NAC group than in the control group.

Microbial Communities, Metabolites, and Correlations with Placental Gene Expression

The fecal microbial communities were quantified by quantitative PCR (Figure 5A). Results showed that NAC significantly (P < 0.05) increased the relative abundances of Clostridium cluster XIVa, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, and Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale, whereas the relative abundances of Clostridium cluster IV, Lactobacillus, Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroidetes, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii were not different between the 2 groups (P > 0.05). As shown in Figure 5B, compared with the control group, the concentrations of fecal propionate and butyrate were significantly increased (P < 0.05) in the NAC group. The concentrations of acetate, valerate, isobutyrate, and isovalerate showed no differences between the 2 groups (P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Microbial communities and SCFA in the feces of sows at delivery. (A) Predominant microbial communities. Values are medians and analyzed with Mann-Whitney U test (n = 6), (B) SCFA. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with the control. SCFA = Short-chain fatty acids.

To further explore the relationship between fecal microbiota and the placenta, the spearman correlation between the relative abundances of bacteria and placental gene expression was analyzed (Figure 6). Results showed that the abundance of Clostridium cluster XIVa was negatively related to the expression of NLRP3 gene, but positively related to the expression of Slc7a8 gene. Bifidobacterium showed positive correlations with the gene VEGF. Alternatively, the abundance of Prevotella showed positive correlations with butyrate and propionate, and genes involved in nutrient transport (Slc7a8, Slc38a1) and angiogenesis (VEGF and HIFα), but negative correlations with genes involved in innate immunity (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, NLRP3). Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale was negatively correlated with the gene NLRP3 and positively correlated with gene Slc7a8.

Figure 6.

Spearman correlations between the relative abundance of Clostridium cluster XIVa, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella and Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale, and metabolites and placental gene expression. The depth of the colors represents the correlation. Spearman correlation coefficient was >0.6 and statistically significant (P < 0.05). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, and #P < 0.1.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that NAC supplementation during late gestation improved maternal-placental antioxidant capacity, increased placental growth factors, gene expression of angiogenesis, and amino acid transporters, decreased placental NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy, and altered fecal microbial communities. Furthermore, the changes in fecal microbiota were negatively correlated with placental NLRP3 inflammasome and positively correlated with nutrient transport.

N-acetyl-cysteine, a precursor of glutathione, is widely used to protect a series of tissues and organs such as gut (Zhu et al., 2013), brain (Chen et al., 2014), and liver (Zhang et al., 2018) from oxidative stress under adverse conditions. The placenta is a unique interface that preserves fetal development during pregnancy in response to adverse maternal environment. In the present study, NAC increased the activities of GSH-Px and SOD, and decreased the content of MDA in both the sow plasma and the placenta. These were in accordance with Guo’s study, which showed that NAC alleviates cadmium-induced placental glutathione depletion and endoplasmic reticulum stress in mice, suggesting that maternal NAC supplementation during late pregnancy promotes maternal-placental antioxidant activity and prevents against stress-induced injury (Guo et al., 2018). As redox status of the cell may mediate placental cytokines production, which is responsible for placental function and development, the placental NLRP3 inflammasome was investigated. Previous studies reported that porcine conceptus and endometrial caspase-1, IL-18, and IL-1β genes were highly expressed during elongation of the peri-implantation period (Ross et al., 2003; Ashworth et al., 2010), and an aberrant activation of placental NLRP3 inflammasome at term was associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as pontaneous labor and preeclampsia (Gierman et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2018). N-acetyl-cysteine has been reported to suppress LPS-induced maternal and fetal IL-6 and IL-1β levels, and placental infiltration of leukocytes in pregnant rats (Paintlia et al., 2008; Beloosesky et al., 2009). In our study, NAC significantly decreased maternal and placental inflammatory cytokines through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing that NAC inhibited placental NLRP3 inflammasome in sows during late pregnancy. Suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory response in sows and placenta may reduce the fetal exposure to inflammatory mediators and improve fetal growth. In this study, although the reproductive performance results did not meet our expectation, the tendency of these parameters was noteworthy. Thus, more investigations are still needed to explore the effects of NAC on the reproductive performance of sows during gestation with a larger sample size.

Placental VEGF, NO, and HIFα have been considered as important regulators of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, which provide the basic vascular system for effective delivery of nutrients/oxygen to the fetus (Burton et al., 2009). In addition, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is the specific enzyme to produce NO. The reduction of placental NO and aberrant vascular formation is often associated with IUGR (Chen et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2004). A recent study showed that NAC injection during pregnancy increased cadmium-induced gene expression of VEGFα in the placenta of mice (Guo et al., 2018). In vitro, NAC treatment increased eNOS expression in umbilical artery endothelial cells of guinea pigs (Herrera et al., 2017). These findings were consistent with our results, which showed that NAC increased placental NO production, and gene expressions of VEGF and HIFα. Vascular endothelial growth factor could stimulate the release of NO through activation of eNOS in human trophoblast cells (Ahmed et al., 1997). The results therefore suggested a mechanism of maternal NAC supplementation promoting placental vascular formation, possibly through VEGF/eNOS/NO-dependent relaxation.

Placental Slc2a1 and Slc2a3 are involved in glucose transportation, whereas Slc7a9 is responsible for basic amino acids and cysteine transportation. Slc7a8 belongs to the L system, and it has been shown to exchange intracellular cysteine for other extracellular neutral amino acids such as alanine, serine, and glutamine (Broer 2008). Na+-dependent transport system A family, such as Slc38a1 and Slc38a2, has been reported to promote placental delivery of both nonessential and essential amino acids to the fetus (Zhang et al., 2015). The decreased placental glucose transport and system A expression was related to IUGR of humans (Jansson et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2015). Moreover, free radicals were reported to impair human placental amino acid uptake and increase Na+ permeability, directly affecting amino acid transporters (Khullar et al., 2004). In the present study, NAC decreased placental oxidative stress and increased the gene expression of Slc38a1 and Slc7a8. Thus, further studies are needed to confirm whether the placental amino acid uptake and composition were increased by NAC supplementation. Placental IGF-1 and IGF-2 enhance the placental cell proliferation, migration, and nutrient exchange, and are essential for normal fetal growth (Forbes et al., 2008). Cadherins are a family of transmembrane glycoproteins, and especially E-Cadherin plays an important role in trophoblast cell differentiation, adhesion, and communication (Hong et al., 2017). In the present study, NAC increased the contents of placental IGF-1, IGF-2, and E-cadherin, indicating the promoting effects of NAC on the placental development and growth in sows. As mTOR is a nutrient and oxygenation sensing pathway, which is involved in nutrient delivery and autophagy, the autophagy-related proteins and regulating pathways were investigated (Nicklin et al., 2009). Beclin-1 promotes the formation and initiation of autophagosome, whereas LC3B is the membrane marker for autophagic vacuoles (Saito and Nakashima 2013). In the present study, results showed that NAC decreased Beclin-1 and LC3B-II/I expression while increased ERK and Akt/mTOR pathways. N-acetyl-cysteine was reported to increase the expression of Akt and mTOR proteins and decrease the expression of LC3-II and Beclin-1 proteins in cooking oil fumes–derived particulate matters 2.5-treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Ding et al., 2017). These results therefore suggested that NAC, a reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger, decreased autophagy partially through ROS-mediated ERK and Akt/mTOR pathway.

Fecal microbiota is considered as an important part of pregnancy maintenance. Prevotella and Bacteroides are major propionate producers, whereas Clostridium cluster IV, Clostridium cluster XIVa (including Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale), and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii are butyrate-producing bacteria (Mu et al., 2017). These 2 SCFA, derived from undigested carbohydrates and amino acids, were reported to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress (Vinolo et al., 2011). Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are the potential beneficial bacteria, which may be highly susceptible to oxidative stress (Xu et al., 2014). In our study, NAC increased the relative abundances of fecal Clostridium cluster XIVa, Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale, Prevotella, and Bifidobacterium in sows, and the increased Prevotella was positively correlated with the increased propionate and butyrate concentrations. These were consistent with our previous study in weaned pigs, which indicated that NAC favored the number of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and reduced the number of Escherichia coli in intestinal contents of weaned pigs, suggesting that modulation of redox status could maintain balance of intestinal microbiota and metabolites (Xu et al., 2014). Furthermore, the changes of gut microbiota and their metabolic toxins and effector proteins, such as nigericin, LPS, and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin could regulate host innate immunity such as activation of NLRP3 inflammasome (Brereton et al., 2011; von Moltke et al., 2013). Also, the overgrowth of the family Prevotellaceae in the phylum Bacteroidetes was reported in NLRP6-deficiency mice (Elinav et al., 2011). Interestingly, the present study indicated that the relative abundances of Clostridium cluster XIVa, Prevotella, and Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale were negatively related to the expression of gene NLRP3 and positively to gene Slc7a8, indicating strong interactions between gut microbiota and placental NLRP3 inflammasome and nutrients delivery. Of note, the lower abundances of microbiota, such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Prevotella, were reported to colonize in endometrium and placenta, which could affect maternal and neonatal metabolism and immunity (Aagaard et al., 2014; Moreno et al., 2016). Unfortunately, the placental microbiome was not investigated in this study as the placenta ultimately delivered at term and possibly contaminated by the vaginal microbiota (Aagaard et al., 2014). Thus, the involvement of the placental specific bacterial proteins or endogenous products in regulation of inflammasome and nutrient transport in sows during pregnancy still needs further study.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that NAC supplementation during late gestation improved redox status, inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome of maternal-placental interface, increased placental expression of gene VEGF, nutrients transport genes Slc7a8 and Slc38a1, decreased autophagy protein expression, and increased ERK and Akt/mTOR pathways. In addition, NAC supplementation altered fecal microbial communities and metabolites. Furthermore, the increase of fecal Prevotella, Clostridium cluster XIVa, and Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale was negatively correlated with placental NLRP3 inflammasome and positively correlated with nutrient transport gene Slc7a8, suggesting an important relationship in microbial-placental axis.

Footnotes

The study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFD0500600).

LITERATURE CITED

- Aagaard K., Ma J., Antony K. M., Ganu R., Petrosino J., and Versalovic J.. 2014. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci. Transl. Med. 6:237ra65. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A., Dunk C., Kniss D., and Wilkes M.. 1997. Role of VEGF receptor-1 (flt-1) in mediating calcium-dependent nitric oxide release and limiting DNA synthesis in human trophoblast cells. Lab. Invest. 76:779–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gubory K. H., Fowler P. A., and Garrel C.. 2010. The roles of cellular reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and antioxidants in pregnancy outcomes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42:1634–1650. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armougom F., Henry M., Vialettes B., Raccah D., and Raoult D.. 2009. Monitoring bacterial community of human gut microbiota reveals an increase in lactobacillus in obese patients and methanogens in anorexic patients. PLoS One. 4:e7125. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth M. D., Ross J. W., Stein D. R., White F. J., Desilva U. W., and Geisert R. D.. 2010. Endometrial caspase 1 and interleukin-18 expression during the estrous cycle and peri-implantation period of porcine pregnancy and response to early exogenous estrogen administration. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 8:33. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-8-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloosesky R., Weiner Z., Khativ N., Maravi N., Mandel R., Boles J., Ross M. G., and Itskovitz-Eldor J.. 2009. Prophylactic maternal n-acetylcysteine before lipopolysaccharide suppresses fetal inflammatory cytokine responses. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200:665.e1–665.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchieri-Ronchi C. B., Kim S. W., Zhao Y., Correa C. R., Yeum K. J., and Ferreira A. L.. 2011. Oxidative stress status of highly prolific sows during gestation and lactation. Animal. 5:1774–1779. doi:10.1017/S1751731111000772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brereton C. F., Sutton C. E., Ross P. J., Iwakura Y., Pizza M., Rappuoli R., Lavelle E. C., and Mills K. H.. 2011. Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin promotes protective th17 responses against infection by driving innate IL-1 and IL-23 production. J. Immunol. 186:5896–5906. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bröer S. 2008. Amino acid transport across mammalian intestinal and renal epithelia. Physiol. Rev. 88:249–286. doi:10.1152/physrev.00018.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton G. J., Charnock-Jones D. S., and Jauniaux E.. 2009. Regulation of vascular growth and function in the human placenta. Reproduction. 138:895–902. doi:10.1530/REP-09-0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. P., Bajoria R., and Aplin J. D.. 2002. Decreased vascularization and cell proliferation in placentas of intrauterine growth-restricted fetuses with abnormal umbilical artery flow velocity waveforms. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 187:764–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Ren Q., Zhang J., Ye Y., Zhang Z., Xu Y., Guo M., Ji H., Xu C., Gu C., et al. 2014. N-acetyl-L-cysteine protects against cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting ROS-dependent activation of akt/mtor pathway in mouse brain. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 40:759–777. doi:10.1111/nan.12103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Y., Rosario F. J., Shehab M. A., Powell T. L., Gupta M. B., and Jansson T.. 2015. Increased ubiquitination and reduced plasma membrane trafficking of placental amino acid transporter SNAT-2 in human IUGR. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 129:1131–1141. doi:10.1042/CS20150511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P., Teal S., Jansson T., and Powell T.. 2016. Changes in the human placental inflammasome across gestation. Placenta. 45:88. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2016.06.095 [Google Scholar]

- Degroote J., Michiels J., Claeys E., Ovyn A., and De Smet S.. 2012. Changes in the pig small intestinal mucosal glutathione kinetics after weaning. J. Anim. Sci. 90(Suppl 4):359–361. doi:10.2527/jas.53809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding R., Zhang C., Zhu X., Cheng H., Zhu F., Xu Y., Liu Y., Wen L., and Cao J.. 2017. ROS-AKT-mtor axis mediates autophagy of human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced by cooking oil fumes-derived fine particulate matters in vitro. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 113:452–460. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.10.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echarri P. P., Graciá C. M., Berruezo G. R., Vives I., Ballesta M., Solís G., Morillas I. V., Reyes-Gavilán C. G., Margolles A., and Gueimonde M.. 2011. Assessment of intestinal microbiota of full-term breast-fed infants from two different geographical locations. Early Hum. Dev. 87:511–513. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E., Strowig T., Kau A. L., Henao-Mejia J., Thaiss C. A., Booth C. J., Peaper D. R., Bertin J., Eisenbarth S. C., Gordon J. I., et al. 2011. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. 145:745–757. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everard A., Belzer C., Geurts L., Ouwerkerk J. P., Druart C., Bindels L. B., Guiot Y., Derrien M., Muccioli G. G., Delzenne N. M., et al. 2013. Cross-talk between akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:9066–9071. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219451110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes K., and Westwood M.. 2008. The IGF axis and placental function. A mini review. Horm. Res. 69:129–137. doi:10.1159/000112585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S., Xu L., Li S., Qiu Y., Liu Y., Wu Z., Ye C., Hou Y., and Hu C. A.. 2016. Baicalin suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κb) signaling during haemophilus parasuis infection. Vet. Res. 47:80. doi:10.1186/s13567-016-0359-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierman L., Silva G., Stødle G., Tangerås L., Thomsen L. C., Skei B., Collett K., Beversmark A.-L., Aune M., Bjørge L., and Iversen A. C.. 2016. NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activation at the maternal-fetal interface in preeclamptic and healthy pregnancies. Placenta. 45:88. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2016.06.095 [Google Scholar]

- Guo M. Y., Wang H., Chen Y. H., Xia M. Z., Zhang C., and Xu D. X.. 2018. N-acetylcysteine alleviates cadmium-induced placental endoplasmic reticulum stress and fetal growth restriction in mice. PLoS One. 13:e0191667. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera E. A., Cifuentes-Zúñiga F., Figueroa E., Villanueva C., Hernández C., Alegría R., Arroyo-Jousse V., Peñaloza E., Farías M., Uauy R., et al. 2017. N-acetylcysteine, a glutathione precursor, reverts vascular dysfunction and endothelial epigenetic programming in intrauterine growth restricted guinea pigs. J. Physiol. 595:1077–1092. doi:10.1113/JP273396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L., Han K., Wu K., Liu R., Huang J., Lunney J. K., Zhao S., Yu M.. 2017. E-cadherin and ZEB2 modulate trophoblast cells differentiation during placental development in pigs. Reproduction. 154:765-775. doi:10.1530/REP-17-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson T., Ylvén K., Wennergren M., and Powell T. L.. 2002. Glucose transport and system A activity in syncytiotrophoblast microvillous and basal plasma membranes in intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 23:392–399. doi:10.1053/plac.2002.0826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T., Matsuki T., Oka M., Utsunomiya H., Inada K., Magari H., Inoue I., Maekita T., Ueda K., Enomoto S., et al. 2009. Gastric acid reduction leads to an alteration in lower intestinal microflora. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 381:666–670. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khullar S., Greenwood S. L., McCord N., Glazier J. D., and Ayuk P. T.. 2004. Nitric oxide and superoxide impair human placental amino acid uptake and increase Na+ permeability: implications for fetal growth. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 36:271–277. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren O., Goodrich J. K., Cullender T. C., Spor A., Laitinen K., Bäckhed H. K., Gonzalez A., Werner J. J., Angenent L. T., Knight R., et al. 2012. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 150:470–480. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz E., Xiao T. S., and Stutz A.. 2013. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13:397–411. doi:10.1038/nri3452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Kong X., Li F., Tan B., Li Y., Duan Y., Yin Y., He J., Hu C., Blachier F., et al. 2016. Co-dependence of genotype and dietary protein intake to affect expression on amino acid/peptide transporters in porcine skeletal muscle. Amino Acids. 48:75–90. doi:10.1007/s00726-015-2066-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Li C., Cheng Y., Hang S., and Zhu W.. 2015. Effects of low dietary protein on the metabolites and microbial communities in the caecal digesta of piglets. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 69:212–226. doi:10.1080/1745039X.2015.1034521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Luo W., Li S., Zhao S., Sho T., Xu X., Zhang J., Xu W., and Xu J.. 2018. Reactive oxygen species mediated placental oxidative stress, mitochondrial content, and cell cycle progression through mitogen-activated protein kinases in intrauterine growth restricted pigs. Reprod. Biol. 18:422–431. doi:10.1016/j.repbio.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Zhu W., Guo Q., Luo W., Zhang J., Xu W., and Xu J.. 2016. Weaning induced hepatic oxidative stress, apoptosis, and aminotransferases through MAPK signaling pathways in piglets. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016:4768541. doi:10.1155/2016/4768541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson A. J., de Agüero M. G., and Ganal-Vonarburg S. C.. 2017. How nutrition and the maternal microbiota shape the neonatal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17:508–517. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki T., Watanabe K., Fujimoto J., Takada T., and Tanaka R.. 2004. Use of 16S rrna gene-targeted group-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7220–7228. doi:10.1128/AEM.70.12.7220-7228.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q., Guo T., Li G., Sun S., He S., Cheng B., Shi B., and Shan A.. 2018. Dietary resveratrol improves antioxidant status of sows and piglets and regulates antioxidant gene expression in placenta by keap1-nrf2 pathway and sirt1. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 9:34. doi:10.1186/s40104-018-0248-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menino A. R. Jr, Hogan A., Schultz G. A., Novak S., Dixon W., and Foxcroft G. H.. 1997. Expression of proteinases and proteinase inhibitors during embryo-uterine contact in the pig. Dev. Genet. 21:68–74. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)21:1<68::AID-DVG8>3.0.CO;2-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Moltke J., Ayres J. S., Kofoed E. M., Chavarría-Smith J., and Vance R. E.. 2013. Recognition of bacteria by inflammasomes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31:73–106. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor G., and Kwon J. Y.. 2015. Trophoblast-microbiome interaction: a new paradigm on immune regulation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 213(4 Suppl):S131–S137. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno I., Codoñer F. M., Vilella F., Valbuena D., Martinez-Blanch J. F., Jimenez-Almazán J., Alonso R., Alamá P., Remohí J., Pellicer A., et al. 2016. Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 215:684–703. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu C., Yang Y., Luo Z., and Zhu W.. 2017. Temporal microbiota changes of high-protein diet intake in a rat model. Anaerobe. 47:218–225. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklin P., Bergman P., Zhang B., Triantafellow E., Wang H., Nyfeler B., Yang H., Hild M., Kung C., Wilson C., et al. 2009. Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mtor and autophagy. Cell. 136:521–534. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC 2012. Nutrient Requirements of swine. Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Paintlia M. K., Paintlia A. S., Singh A. K., and Singh I.. 2008. Attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response and phospholipids metabolism at the feto-maternal interface by N-acetyl cysteine. Pediatr. Res. 64:334–339. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e318181e07c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PrabhuDas M., Bonney E., Caron K., Dey S., Erlebacher A., Fazleabas A., Fisher S., Golos T., Matzuk M., McCune J. M., et al. 2015. Immune mechanisms at the maternal-fetal interface: perspectives and challenges. Nat. Immunol. 16:328–334. doi:10.1038/ni.3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Farias C., Slezak K., Fuller Z., Duncan A., Holtrop G., and Louis P.. 2008. Effect of inulin on the human gut microbiota: stimulation of bifidobacterium adolescentis and faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Br. J. Nutr. 101:541–550. doi:10.1017/S0007114508019880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam V. A., Vanaja S. K., and Fitzgerald K. A.. 2012. Regulation of inflammasome signaling. Nat. Immunol. 13:333–342. doi:10.1038/ni.2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R., Xu Y., Plazyo O., Chaemsaithong P., Chaiworapongsa T., Unkel R., Than N. G., Chiang P. J., Dong Z., Xu Z., et al. 2018. A role for the inflammasome in spontaneous labor at term. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 79:e12440. doi:10.1111/aji.12440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. W., Malayer J. R., Ritchey J. W., and Geisert R. D.. 2003. Characterization of the interleukin-1beta system during porcine trophoblastic elongation and early placental attachment. Biol. Reprod. 69:1251–1259. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.103.015842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S., and Nakashima A.. 2013. Review: the role of autophagy in extravillous trophoblast function under hypoxia. Placenta. 34(Suppl):S79–S84. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson D. M., and Weimer P. J.. 2007. Dominance of prevotella and low abundance of classical ruminal bacterial species in the bovine rumen revealed by relative quantification real-time PCR. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75:165–174. doi:10.1007/s00253-006-0802-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. T., Taylor L. T., and DeLong E. F.. 2000. Quantitative analysis of small-subunit rrna genes in mixed microbial populations via 5’-nuclease assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4605–4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C., Wei H., Ao J., Long G., and Peng J.. 2016. Inclusion of konjac flour in the gestation diet changes the gut microbiota, alleviates oxidative stress, and improves insulin sensitivity in sows. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82:5899–5909. doi:10.1128/AEM.01374-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinolo M. A., Rodrigues H. G., Nachbar R. T., and Curi R.. 2011. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 3:858–876. doi:10.3390/nu3100858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. W., Ince J., Duncan S. H., Webster L. M., Holtrop G., Ze X., Brown D., Stares M. D., Scott P., Bergerat A., et al. 2011. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. Isme ISME J. 5:220–230. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S. H., Kwong T. N. Y., Chow T. C., Luk A. K. C., Dai R. Z. W., Nakatsu G., Lam T. Y. T., Zhang L., Wu J. C. Y., Chan F. K. L., et al. 2017. Quantitation of faecal fusobacterium improves faecal immunochemical test in detecting advanced colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 66:1441–1448. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F. W., Cudd T. A., Meininger C. J., and Spencer T. E.. 2004. Maternal nutrition and fetal development. J. Nutr. 134:2169–2172. doi:10.1093/jn/134.9.2169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C. C., Yang S. F., Zhu L. H., Cai X., Sheng Y. S., Zhu S. W., and Xu J. X.. 2014. Regulation of N-acetyl cysteine on gut redox status and major microbiota in weaned piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 92:1504–1511. doi:10.2527/jas.2013-6755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J., Liu M., Ren W., Duan J., Yang G., Zhao Y., Fang R., Chen L., Li T., and Yin Y.. 2015. Effects of dietary supplementation with glutamate and aspartate on diquat-induced oxidative stress in piglets. PLoS One. 10:e0122893. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Regnault T. R., Barker P. L., Botting K. J., McMillen I. C., McMillan C. M., Roberts C. T., and Morrison J. L.. 2015. Placental adaptations in growth restriction. Nutrients. 7:360–389. doi:10.3390/nu7010360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Su W., Ying Z., Chen Y., Zhou L., Li Y., Zhang J., Zhang L., and Wang T.. 2018. N-acetylcysteine attenuates intrauterine growth retardation-induced hepatic damage in suckling piglets by improving glutathione synthesis and cellular homeostasis. Eur. J. Nutr. 57:327–338. doi:10.1007/s00394-016-1322-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Cai X., Guo Q., Chen X., Zhu S., and Xu J.. 2013. Effect of N-acetyl cysteine on enterocyte apoptosis and intracellular signalling pathways’ response to oxidative stress in weaned piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 110:1938–1947. doi:10.1017/S0007114513001608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]