Matrix metallopeptidase-10 fosters Helicobacter pylori gastric bacterial colonization and Helicobacter pylori–induced gastritis.

Abstract

The interaction between gastric epithelium and immune response plays key roles in H. pylori–associated pathology. We demonstrated a procolonization and proinflammation role of MMP-10 in H. pylori infection. MMP-10 is elevated in gastric mucosa and is produced by gastric epithelial cells synergistically induced by H. pylori and IL-22 via the ERK pathway. Human gastric MMP-10 was correlated with H. pylori colonization and the severity of gastritis, and mouse MMP-10 from non–BM-derived cells promoted bacteria colonization and inflammation. H. pylori colonization and inflammation were attenuated in IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice. MMP-10–associated inflammation is characterized by the influx of CD8+ T cells, whose migration is induced via MMP-10–CXCL16 axis by gastric epithelial cells. Under the influence of MMP-10, Reg3a, E-cadherin, and zonula occludens–1 proteins decrease, resulting in impaired host defense and increased H. pylori colonization. Our results suggest that MMP-10 facilitates H. pylori persistence and promotes gastritis.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a human pathogen that infects nearly half of the world’s population (1). Although the persistent colonization of H. pylori and the development of H. pylori–associated gastritis in gastric mucosa remain poorly understood, it is believed that the interaction between gastric epithelium and immune response induced by H. pylori is a key contributing factor. Gastric epithelial cells are not only the first line of host defense but also can produce factors that attract immune cells to mount a larger, multiplied inflammatory response. Among the many molecules produced by gastric epithelial cells in response to infection are the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).

MMP-10 is an MMP that has been proposed to both protect against pathogens and contribute to pathology in infectious diseases. In mice, it has been reported that MMP-10 plays roles in regulating biological processes in airway epithelial host responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2). In contrast, others have found that MMP-10 levels increased with disease progression in mouse models of Borrelia burgdorferi infection (3) and was associated with the severity of sepsis in humans (4). MMP-10 represents a newly discovered MMP during H. pylori infection (5), but, to date, virtually nothing is known about its regulation, function, and clinical relevance during H. pylori infection in either humans or mice.

In the current study, we have demonstrated that MMP-10 plays a role in procolonization and proinflammation in H. pylori infection. Increased MMP-10 is detected in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients and mice, and it is synergistically induced in gastric epithelial cells by H. pylori and interleukin-22 (IL-22) via the extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. We further demonstrate that MMP-10 promotes CXCL16 production, which, in turn, recruits CD8+ T cells that contribute to inflammation, and inhibits Reg3a, epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin), and zonula occludens–1 (ZO-1) leading to impaired host defenses and increased H. pylori colonization. Collectively, these data highlight a pathological role for MMP-10 in H. pylori–persistent infection and clinical gastritis.

RESULTS

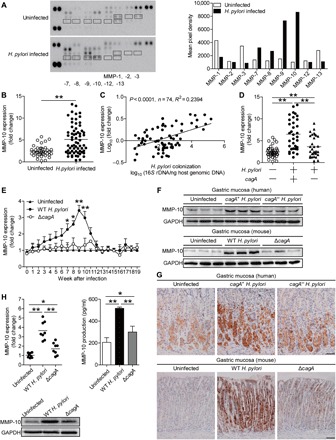

MMP-10 is increased in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients and mice

To evaluate the potential role of MMP-10 in H. pylori infection, we first compared MMP profiles secreted by human primary gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected and uninfected donors using antibody (Ab) microarrays. Among them, MMP-10 was the most increased MMP in gastric mucosa infected with H. pylori compared to paired uninfected counterparts (Fig. 1A). We then confirmed that, compared to uninfected donors, the overall MMP-10 mRNA level was higher in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients (Fig. 1B), and we further demonstrated that MMP-10 expression was positively correlated with H. pylori colonization (Fig. 1C), suggesting induction of MMP-10 by H. pylori.

Fig. 1. MMP-10 is increased in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients and mice.

(A) Representative MMP array results for human primary gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients and paired uninfected donors using Ab microarrays. Profiles of mean spot pixel density were created using a transmission-mode scanner and image analysis software (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health). (B) MMP-10 mRNA expression in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected (n = 65) and uninfected donors (n = 40) was compared. (C) The correlation between MMP-10 expression and H. pylori colonization in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients was analyzed. (D) MMP-10 mRNA expression in gastric mucosa of cagA+ H. pylori–infected (n = 34), cagA− H. pylori–infected (n = 31),and uninfected donors (n = 40) was compared. (E) Dynamic changes of MMP-10 mRNA expression in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected, ΔcagA-infected, and uninfected mice. n = 5 per group per time point in (E). (F and G) MMP-10 protein in gastric mucosa of cagA+ H. pylori–infected, cagA− H. pylori–infected, and uninfected donors or in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected, ΔcagA-infected, and uninfected mice at 9 weeks p.i. was analyzed by Western blot (F) and immunohistochemical staining (G). Scale bars, 100 μm. (H) MMP-10 mRNA expression and MMP-10 protein in/from human primary gastric mucosa from uninfected donors infected with WT H. pylori or ΔcagA ex vivo analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Western blot, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (n = 8). The horizontal bars in (B), (D), and (H) represent mean values. Each ring or dot in (B) to (D) and (H) represents one patient or donor. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for groups connected by horizontal lines or compared with uninfected mice. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

The presence of cagA is strongly associated with the development of gastritis (6). Notably, we found that MMP-10 expression in cagA-positive patients was significantly higher than that in cagA-negative individuals (Fig. 1D). Consistent with our findings in humans, MMP-10 was also detected in H. pylori NCTC (National Collection of Type Cultures) 11637 (cagA positive) [wild-type (WT) H. pylori] but not in cagA-knockout mutant H. pylori NCTC 11637 (ΔcagA)–infected mice, reaching a peak of 9 weeks postinfection (p.i.) (Fig. 1E), indicating a key role for cagA in induction of MMP-10 during H. pylori infection in vivo. Furthermore, Western blot analysis (Fig. 1F) and immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 1G) also showed that the level of MMP-10 protein was higher in the gastric mucosa of cagA-positive H. pylori–infected patients and WT H. pylori–infected mice, compared to either uninfected or cagA-negative patients and ΔcagA-infected counterparts. Similar observations were made when analyzing MMP-10 protein by immunofluorescence staining (fig. S1B). Furthermore, infection with WT H. pylori ex vivo, the levels of MMP-10 mRNA and protein in/from the human primary gastric mucosa were also significantly elevated compared to uninfected samples either or to those infected with ΔcagA (Fig. 1H). Together, these findings suggest that MMP-10 is increased in the H. pylori–infected gastric mucosa of both human patients and mice.

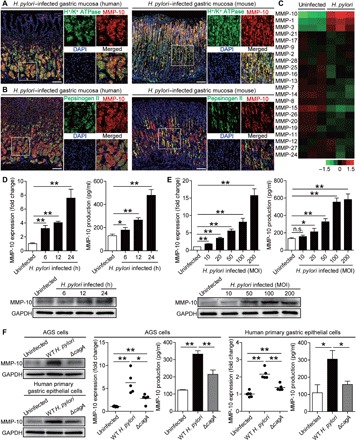

Gastric epithelial cells stimulated by H. pylori express and produce MMP-10

Gastric epithelial cells are known to be the site of initial bacterial contact in the gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection (6). We therefore sought to determine whether gastric epithelial cells were responsible for MMP-10 expression during H. pylori infection. Within gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected donors or mice, MMP-10 was expressed in both H+/K+ ATPase+ parietal cells and pepsinogen II+ chief cells during H. pylori infection (Fig. 2, A and B). These data suggest that gastric epithelial cells are the source cells that express MMP-10 in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

Fig. 2. H. pylori stimulates gastric epithelial cells express MMP-10.

(A) Representative immunofluorescence staining images showing MMP-10–expressing (red) H+/K+ ATPase+ parietal cells (green) in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients or H. pylori–infected mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Representative immunofluorescence staining images showing MMP-10–expressing (red) pepsinogen II+ chief cells (green) in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients or H. pylori–infected mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (C) MMP family mRNA expression in WT H. pylori–infected and uninfected AGS cells [multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 100 for 6 hours] were compared by microarray (n = 3). (D and E) MMP-10 mRNA expression and MMP-10 protein in/from WT H. pylori–infected and uninfected AGS cells at different time points (MOI = 100) (D) or with different MOI (24 hours) (E) were analyzed by real-time PCR, Western blot, or ELISA (n = 3). n.s., not significant. (F) MMP-10 mRNA expression and MMP-10 protein in/from WT H. pylori–infected, ΔcagA-infected, and uninfected human primary gastric epithelial cells (MOI = 100 for 24 hours) were analyzed by real-time PCR, Western blot, or ELISA (n = 5). The horizontal bars in (F) represent mean values. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for groups connected by horizontal lines.

Next, we screened members of MMP family in AGS cells, a human gastric epithelial cell line, and found that MMP-10 was the most increased MMP induced by H. pylori (Fig. 2C). We further demonstrated that H. pylori–infected AGS cells increased MMP-10 mRNA and protein expression and production in a time-dependent (Fig. 2D) and infection dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2E). Notably, compared to uninfected or individuals infected with ΔcagA, WT H. pylori–infected AGS cells and human primary gastric epithelial cells also potently increased MMP-10 mRNA and protein expression and production (Fig. 2F). Similar observations were made when other human gastric epithelial cell lines were infected with H. pylori (fig. S2, C to F). To explore the nature of MMP-10 induction more closely, we performed transwell assays and found that bacterium-cell contact was necessary for the induction of MMP-10 production from AGS cells infected with H. pylori (fig. S2G). Furthermore, MMP-10 produced by AGS cells was active, and the activated MMP-10 was more pronounced from AGS cells infected with WT H. pylori when compared to uninfected or individuals infected with ΔcagA (fig. S2H). We also found that H. pylori was in contact with the MMP-10–expressing cells in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients (fig. S2L). Collectively, these results demonstrate that H. pylori infection induces MMP-10 expression and production in and from gastric epithelial cells, implying that induction of MMP-10 in these cells is a major cause of increased MMP-10 within the H. pylori–infected gastric mucosa.

H. pylori and IL-22 induce MMP-10 synergistically

Our previous data showed that T helper (TH) cell responses such as TH1, TH17 (7), and TH22 (8) play critical roles in H. pylori–induced gastritis. To explore whether cytokines from these TH cells have synergistic effects on inducing MMP-10 during H. pylori infection, we first stimulated AGS cells with H. pylori together with or without interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-17A, or IL-22 in vitro and found that only IL-22 exerted a synergistic effect on MMP-10 mRNA expression (Fig. 3A and fig. S2I) and MMP-10 protein expression/production (Fig. 3, A and B). Similar observations were made using human primary gastric epithelial cells infected with H. pylori in the presence or absence of IL-22 (Fig. 3, B and C). However, IL-22 had no synergistic effect on the induction of MMP-10 expression and production in/from AGS cells infected with ΔcagA (fig. S2K). This observation was confirmed in vivo in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected WT, IFN-γ−/−, IL-17A−/−, or IL-22−/− mice, as we only found decreased MMP-10 expression in IL-22−/− mice (Fig. 3D and fig. S2J). Furthermore, MMP-10 expression was found to be positively correlated with IL-22 expression in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients (Fig. 3E). The results showed that H. pylori and IL-22 synergistically induce MMP-10 expression in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 3. H. pylori and IL-22 synergistically induce MMP-10.

(A and B) MMP-10 mRNA and protein expression in/from AGS cells stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and/or IL-22 (100 ng/ml) (24 hours) or stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and IL-22 (100, 200, and 400 ng/ml) (24 hours) were analyzed by real-time PCR, ELISA (A), or Western blot (B) (n = 3). (B and C) MMP-10 mRNA and protein expression in/from human primary gastric epithelial cells stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and/or IL-22 (100 ng/ml) (24 hours) were analyzed by real-time PCR and ELISA (C) or Western blot (B) (n = 3). (D) MMP-10 mRNA expression in gastric mucosa of uninfected or WT H. pylori–infected WT and IL-22−/− mice at 9 weeks p.i. was compared (n = 5). (E) The correlation between MMP-10 expression and IL-22 expression in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients was analyzed. (F) AGS cells were pretreated with signal pathway inhibitors and then stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and IL-22 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. MMP-10 mRNA expression in AGS cells was compared (n = 3). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase. (G) AGS cells were stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and/or IL-22 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours or pretreated with U0126 (an ERK inhibitor) and then stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and IL-22 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 proteins were analyzed by Western blot. (H) AGS cells were pretreated with anti–IL-22 and/or IL-22R1 neutralizing Abs and then stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and/or IL-22 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. MMP-10, ERK1/2, and p-ERK1/2 proteins in/from AGS cells were analyzed by ELISA or Western blot (n = 3). Each dot in (E) represents one patient. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s., P > 0.05 for groups connected by horizontal lines.

To further explore which signaling pathways might operate in the induction of MMP-10 in gastric epithelial cells by H. pylori and IL-22, we first pretreated AGS cells with corresponding pathway inhibitors and then stimulated them with H. pylori and IL-22. The results showed that only blocking the signal transduction of the ERK pathway with inhibitor U0126 effectively decreased MMP-10 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, ERK1/2, a direct ERK pathway downstream substrate, was phosphorylated in the infected AGS cells either in the presence of IL-22, which was abolished when the ERK signal transduction pathway was blocked with inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 3G), or when the IL-22–IL-22 receptor interaction was blocked with either anti–IL-22 or anti–IL-22 receptor 1 (IL-22R1) (Fig. 3H). Moreover, abolishing the IL-22–IL-22 receptor interaction with either anti–IL-22 or anti–IL-22R1, blocking Abs also efficiently inhibited MMP-10 expression/production in/from AGS cells induced by H. pylori and IL-22 (Fig. 3H).Together, these findings suggest that the induction of MMP-10 in H. pylori–infected gastric epithelial cells can be synergistically augmented by IL-22 via activating the ERK signaling pathway.

MMP-10 increases bacterial burden and inflammation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection

To evaluate the possible biological effects of MMP-10 in H. pylori–associated pathogenesis in vivo, we compared the levels of bacterial colonization in gastric mucosa at 9 weeks p.i. among WT, IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice and found that abolishing IL-22 and/or MMP-10 in IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice during H. pylori infection effectively reduced H. pylori colonization when compared to that in WT mice. This was more pronounced when MMP-10 was abolished in MMP-10−/− and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice compared to that in IL-22−/− mice (Fig. 4A). These data suggest that MMP-10 is the effector molecule, and IL-22 plays an augmenting role in vivo during H. pylori infection.

Fig. 4. MMP-10 increases bacterial burden, inflammation, and CD8+T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

(A and B) The bacteria colonization in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, IL-22−/−MMP-10−/−, and WT mice (A) or in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected BM chimera mice (B) at 9 weeks p.i. was compared (n = 6). (C and D) Histological scores of inflammation in gastric antra of WT H. pylori–infected IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, IL-22−/−MMP-10−/−, and WT mice (C) or in gastric antra of WT H. pylori–infected BM chimera mice (D) at 9 weeks p.i. was compared (n = 6). (E and F) CD3+CD8+ cell level in gastric mucosa of uninfected WT mice and WT H. pylori–infected IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, IL-22−/−MMP-10−/−, and WT mice (E) or in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected BM chimera mice (F) at 9 weeks p.i. was compared (n = 5 to 6). The horizontal bars in (A) to (F) represent mean values. Each dot in (A) to (F) represents one mouse. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s., P > 0.05 for groups connected by horizontal lines.

Our previous data indicated that gastric epithelial cells are likely the source cells that express MMP-10 (Fig. 2), and TH cells are likely the source cells that produce IL-22 in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection (8). We next generated bone marrow (BM) chimera mice to determine the contribution of BM-derived IL-22–producing cells (including TH cells) and non–BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells (including gastric epithelial cells) to bacterial colonization. First, IL-22−/− BM into MMP-10−/− mice effectively reduced H. pylori colonization when compared to that in MMP-10−/− BM into IL-22−/− mice (Fig. 4B, left panel), suggesting that BM-derived IL-22–producing cells and non–BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells contribute to increasing bacterial colonization. To formally exclude the possibility that BM-derived cells may also contribute MMP-10 and non–BM-derived cells may also contribute IL-22 in the gastric mucosa, we generated other BM chimera mice (IL-22−/− BM, MMP-10−/− BM, and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− BM into IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice) and found that either BM-derived IL-22–producing cells or BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells had no effects on increasing bacterial colonization (Fig. 4B, middle panel). Last, compared to MMP-10−/− BM into WT mice, WT BM into MMP-10−/− mice were not able to correct the increased H. pylori colonization, indicating that the defect is not associated with BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells (Fig. 4B, right panel). Collectively, using these BM chimera mice, we found that non–BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells were largely responsible for bacterial colonization in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection in this model (Fig. 4B). Together, our data demonstrate that MMP-10 produced by non–BM-derived cells plays an essential role in promoting bacterial colonization in vivo.

H. pylori–associated gastritis is characterized as inflammatory cell infiltration under chronic inflammatory conditions. Next, we also evaluated the inflammatory response in gastric mucosa in these knockout mice and BM chimera mice described above and found that abolishing IL-22 and/or MMP-10 in IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice during H. pylori infection effectively reduced gastric inflammation when compared to that in WT mice, and this was more pronounced when MMP-10 was abolished in MMP-10−/− and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice compared to that in IL-22−/− mice (Fig. 4C and fig. S3A). In BM chimera mice, we found that non–BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells were largely responsible for gastric inflammation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection (Fig. 4D and fig. S3C). Furthermore, we compared the levels of MMP-10 expression in gastric mucosa with different severity of gastritis and found that the expression of MMP-10 was positively correlated with the severity of gastritis (fig. S3B). Collectively, these results suggest that MMP-10 has effects of promoting bacterial colonization and inflammation during H. pylori infection in vivo.

MMP-10 promotes CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo and migration in vitro during H. pylori infection via CXCL16

To investigate whether increased MMP-10 regulated immune cell infiltration into the gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection, we compared the levels of CD11b+ monocytes, Gr1+ neutrophils, CD3+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, and NK1.1+ natural killer cells in gastric mucosa at 9 weeks p.i. among WT, IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice and found that abolishing IL-22 and/or MMP-10 in these mice only reduced CD3+ T cells, and this was more pronounced in MMP-10−/− and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice compared to that in IL-22−/− mice (fig. S4, A and B). Furthermore, we determined that CD3+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4E and fig. S5C) not CD3+CD8− T cells (fig. S4D) were the main cell population affected by the increased MMP-10. These results were also confirmed by our BM chimera experiments in which non–BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells were largely responsible for the CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection (Fig. 4F and fig. S5D).Similar observations were made when analyzing the number of CD8+ T cells per million total cells in gastric mucosa (fig. S5, A and B). Furthermore, a higher CD8+ T cell infiltration was found in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients (fig. S5E). Together, our data demonstrate that MMP-10 plays an essential role in CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection. Last, we compared the bacterial colonization and evaluated the inflammation in gastric mucosa at 9 weeks p.i. among WT, CD8−/−, and Rag1−/− mice and found that abolishing CD8+ T cells in CD8−/− mice during H. pylori infection effectively reduced inflammation but had no effects on H. pylori colonization when compared to those in WT mice and that inflammation was decreased, but H. pylori colonization was increased in Rag1−/− mice compared to those in WT mice (fig. S5F).

Chemotaxis plays important roles in T cell migration (9). We were therefore interested to know whether MMP-10 induces chemokine production in gastric mucosa. We screened chemokines in gastric mucosa at 9 weeks p.i. between WT and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice and found that only CXCL16 expression was reduced in IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice (fig. S6A), and this reduction of CXCL16 production was less pronounced in IL-22−/− mice (fig. S6B). Again, BM chimera experiments confirmed that non–BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells were largely responsible for CXCL16 production in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection (fig. S6C). Together, our data demonstrate that MMP-10 plays an essential role in inducing CXCL16 production in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

Next, we tried to determine whether CD8+ T cell migration and accumulation during H. pylori infection was regulated by MMP-10–CXCL16 axis. To begin, we found that MMP-10 expression was positively correlated with CXCL16 expression in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients (Fig. 5A) and that the expression of CXCL16 was positively correlated with the severity of gastritis (Fig. 5A). Then, CXCL16 production from AGS cells and mouse primary gastric epithelial cells was regulated in an MMP-10–dependent manner (Fig. 5B). Mice infected with H. pylori showed a higher expression of CXCR6, the chemokine receptor of CXCL16, in blood (Fig. 5C) or gastric (fig. S6E) CD8+ T cells. Consistent with this, we also found a higher expression of CXCR6 on blood CD8+ T cells of H. pylori–infected patients compared to uninfected donors (Fig. 5C). Last, we conducted a series of loss- and gain-of-function experiments in vivo involving CXCL16 and evaluated the CD8+ T cell response in gastric mucosa at 9 weeks p.i. CXCL16 administration significantly increased CD8+ T cell accumulation; conversely, neutralization of CXCL16 significantly reduced CD8+ T cell accumulation in the gastric mucosa (Fig. 5D and fig. S6F).

Fig. 5. MMP-10 promotes CD8+T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo and migration in vitro during H. pylori infection via CXCL16.

(A) The correlation between MMP-10 expression and CXCL16 expression in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients was analyzed. CXCL16 mRNA expression in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients with mild (n = 22), moderate (n = 20), and severe inflammation (n = 18) was compared. (B) MMP-10 siRNA, NC siRNA, or Lipo3000 only (Mock) pretreated AGS cells or AGS cells without treatment and primary gastric epithelial cells from uninfected IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, IL-22−/−MMP-10−/−, and WT mice were stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) for 24 hours. CXCL16 production was measured in cell culture supernatants by ELISA (n = 3). (C) Representative dot plots of CD3+CD8+ T cells by gating on CD45+ cells and CXCR6 expression on CD3+CD8+ T cells in blood of H. pylori–infected patients or WT H. pylori–infected mice at 9 weeks p.i. CXCR6 levels on CD3+CD8+ T cells in blood of H. pylori–infected patients (n = 15) and uninfected donors (n = 19) or WT H. pylori–infected and uninfected mice (n = 6) at 9 weeks p.i. were compared. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (D) CD3+CD8+ T cell level in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected mice injected with CXCL16 or PBS control or Abs against CXCL16 or corresponding isotype control Ab at 9 weeks p.i. was compared (n = 5). (E and F) CD8+ T cell migration was assessed by a transwell assay, as described in Materials and Methods, and was statistically analyzed (n = 5). The horizontal bars in (A), (C), and (D) represent mean values. Each dot in (A), (C), and (D) represents one mouse or donor. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s., P > 0.05 for groups connected by horizontal lines. sup, supernatant.

To further evaluate the contribution of an MMP-10–CXCL16 axis to the migration of CD8+ T cells in vitro, we performed human CD8+ T cell chemotaxis assay and demonstrated that culture supernatants from WT H. pylori–stimulated AGS cells pretreated with nonspecific control (NC) small interfering RNA (siRNA) induced significantly more CD8+ T cell migration than the supernatants collected from WT H. pylori–infected AGS cells pretreated with MMP-10 siRNA or that from ΔcagA-infected AGS cells pretreated with NC, and this effect was lost upon pretreatment with neutralizing Abs against CXCL16 (Fig. 5E).

Similarly, culture supernatant collected from WT H. pylori–stimulated primary gastric epithelial cells of WT mice also induced significantly more mouse CD8+ T cell migration than those from WT H. pylori–infected primary gastric epithelial cells of MMP-10−/− or IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice or those from ΔcagA-infected primary gastric epithelial cells of WT mice, and this effect was also lost upon pretreatment with neutralizing Abs against CXCL16 (Fig. 5F). Collectively, these results therefore suggest that an MMP-10–CXCL16 axis contributes to CD8+ T cell accumulation within the gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

MMP-10 impairs host defense and promotes the damage of gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection

Given the decreased H. pylori colonization in gastric mucosa of MMP-10−/− mice (Fig. 4A), we hypothesized that MMP-10 might exert inhibiting effects on proteins, which contribute to host defense. The β-defensins (10) and Reg3 proteins (11) play roles in mucosal defense during H. pylori infection. We therefore screened these proteins in gastric mucosa at 9 weeks p.i. between WT and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice and found that abolishing IL-22 and MMP-10 in IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice only leads to increased Reg3a expression when compared to that in WT mice (fig. S7A), and this increased Reg3a production was more pronounced in MMP-10−/− and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice compared to the increase in IL-22−/− mice (Fig. 6A). Again, BM chimera experiments confirmed that non–BM-derived MMP-10–producing cells were largely responsible for inhibiting Reg3a production in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection (Fig. 6B). Last, we conducted gain- or loss-of-function experiments in vivo involving Reg3a and evaluated bacterial colonization in gastric mucosa at 9 weeks p.i. Reg3a administration significantly reduced H. pylori colonization in the gastric mucosa of WT mice (Fig. 6C). Conversely, neutralization of Reg3a significantly increased H. pylori colonization in the gastric mucosa of MMP-10−/− mice (Fig. 6C). Moreover, in vitro bactericidal assay showed that Reg3a exerted killing activity against H. pylori (fig. S7B). Together, our data demonstrate that MMP-10 plays an essential role in inhibiting Reg3a production in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection, which may contribute to bacterial persistence.

Fig. 6. MMP-10 impairs host defense and promotes the damage of gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

(A and B) Concentration of Reg3a protein in gastric mucosa of uninfected WT mice and WT H. pylori–infected IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, IL-22−/−MMP-10−/−, and WT mice (A) or in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected BM chimera mice (B) at 9 weeks p.i. was compared (n = 6). (C) The bacteria colonization in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected WT mice injected with Reg3a or PBS control or in gastric mucosa of WT H. pylori–infected MMP-10−/− mice injected with anti-Reg3a or isotype control Abs at 9 weeks p.i. was compared (n = 6). (D) MMP-10 expression in patients with gastritis (n = 65) and in patients with gastric ulcer (n = 45) was compared. (E) E-cadherin and ZO-1 proteins in gastric mucosa of uninfected WT mice and WT H. pylori–infected IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, IL-22−/−MMP-10−/−, and WT mice at 9 weeks p.i. were analyzed by Western blot. (F) A proposed model of cross-talk among H. pylori, IL-22, gastric epithelial cells, MMP-10, and CD8+ T cells leading to MMP-10–mediated procolonization and proinflammation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection. The horizontal bars in (A) to (D) represent mean values. Each dot or ring in (A) to (D) represents one mouse or donor. **P < 0.01; n.s., P > 0.05 for groups connected by horizontal lines.

Notably, we found that MMP-10 expression in patients with gastric ulcer was significantly higher than that in patients with gastritis (Fig. 6D), suggesting a potential role of MMP-10 in damage to gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection. Western blot analysis (Fig. 6E) showed that abolishing IL-22 and/or MMP-10 in IL-22−/−, MMP-10−/−, and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice during H. pylori infection effectively increased the levels of E-cadherin and ZO-1 proteins when compared to those in WT mice, and this was more pronounced when abolishing MMP-10 in MMP-10−/− and IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice compared to that in IL-22−/− mice. Moreover, we found that compared to H. pylori–infected patients with gastritis, the Reg3a expression was lower, and CD8+ T cell infiltration was higher in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients with gastric ulcer (fig. S7C). Together, our data demonstrate that MMP-10 plays an essential role in inhibiting E-cadherin and ZO-1 proteins in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection, which may contribute to damage of the gastric mucosa.

DISCUSSION

MMP-10 appears to have different roles depending on the nature of the infection. For example, in P. aeruginosa infection (2), MMP-10 provides the host with protection. In contrast, in B. burgdorferi infection (3), MMP-10 may contribute to pathology with disease progression. Our data are in agreement with the latter study since they indicate that, during H. pylori infection, MMP-10 benefits bacterial colonization and contributes to gastritis. As increasing evidence indicates that MMPs, such as MMP-1 (12) and MMP-7 (13), are highly expressed upon H. pylori infection, we have now added MMP-10 onto that list. What remains unclear is why MMP-10 is protective in some infections but pathogenic in others. To this end, our findings that H. pylori–associated virulence factor cagA was necessary to induce maximal MMP-10 expression suggest that intrinsic factors encoded by the infection itself are likely to be important in influencing the role of MMP-10.

In this study, we not only identified a previously unrecognized role for MMP-10 during H. pylori infection but also found that MMP-10 expression was readily induced upon H. pylori infection ex vivo in primary gastric epithelial cells and cell lines. This response is consistent with previous observations on MMP-10 expression in inflamed tissues and/or cells, such as tracheal epithelial cells upon P. aeruginosa infection (2) and colonic epithelial cells in inflammatory bowel diseases (14). MMP-10 expression is known to be promoted by inflammatory cytokines/mediators such as transforming growth factor–β1 (15, 16) and C-reactive protein (14) in different epithelial/endothelial cells. In our case, we identified a new MMP-10–regulating cytokine, IL-22, during H. pylori infection: It exerts a synergistic effect on MMP-10 induction by activating the ERK pathway (5). These findings, together with our previous observations on the proinflammatory effects of IL-22 in H. pylori–associated gastritis (8), point to the combined activities of IL-22 and H. pylori as important determinants of MMP-10 induction in gastric mucosa. It is reported that IL-22 was a key determinant of mucosal vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori, as a decreased H. pylori colonization was shown in vaccinated IL-22−/− mice (17), which is different from our results. It could be speculated that, in H. pylori–vaccinated mice or in mice with primary H. pylori infection, IL-22 may have different functions: by promoting the expression of antimicrobial peptides such as Reg3β (17). IL-22 protects the host in vaccine-induced mice during H. pylori infection; however, IL-22 plays a role of procolonization probably by inhibiting TH1 cell response (8) in mice with primary H. pylori infection. It is also reported that IL-22 promoted Reg3a in human intestinal epithelial cells in a STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3)–dependent manner in vitro (18), which is different from our results of increased Reg3a in IL-22−/− mice in vivo. As for the higher Reg3a in IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice compared to that in IL-22−/− mice (Fig. 6A) and the regulation of MMP-10 by IL-22 (Fig. 3), it could be speculated that a weakened inhibition of Reg3a by MMP-10 in IL-22−/− mice might have contributed to the increased Reg3a in IL-22−/− mice, bearing in mind that in vivo experiments are often more complex. Thus, the underlying regulatory mechanisms between IL-22 and Reg3a in the inflammatory environments of H. pylori–induced gastritis need further investigation.

Multiple evidence support the notion that MMP-10 mediates many of the environmental changes that lead to tissue protection (19) or tissue damage (20): MMP-10 from BM-derived cells (macrophages) played protective roles in the dextran sulfate sodium–induced colitis model (21), however, MMP-10 from non–BM-derived cells (fibroblasts) contributed to tissue destruction in arthritis (22). The latter may also be the case for H. pylori–infected gastric environments, where MMP-10 source was verified from non–BM-derived cells (gastric epithelial cells) and high expression of MMP-10 in clinical samples in association with disease development. Given the apparent relationship between MMP-10 levels and the severity of gastric inflammation even gastric ulcer in H. pylori–infected patients observed in this study, considerations should be given to the use of MMP-10 as previously unknown diagnostic biomarker for H. pylori infection–associated diseases.

The pathologic nature of MMPs has been suggested to involve various mechanisms. For example, MMP-9 or MMP-10 regulated CXCL12- or CCL5-associated chemotaxis to promote systemic lupus erythematosus (23) or hepatocarcinogenesis (21), respectively. Meanwhile, MMP-9 was observed to regulate goblet cell differentiation in colon, which contributes to alteration in mucosal defense leading to inflammation (24). Our findings are consistent with these studies and demonstrate that H. pylori and IL-22 synergistically induce MMP-10 in gastric epithelial cells, which resulted in increased bacterial colonization due to likely impaired host defense (decreased antibacterial protein Reg3a), damaged gastric mucosa (decreased tight junction proteins E-cadherin and ZO-1), and also increased inflammation characterized by the influx of CD8+ T cells via the MMP-10–CXCL16 axis. By screening, we found that CD8+ T cells appeared to be the only downstream immune cells of MMP-10. CD8+ T cells were thought to play a minimal role during chronic H. pylori infection (25). In this study, we have demonstrated increased levels of CD8+ T cells (including percentage and total cell number) in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected mice and humans, indicating that these cells may actually play an important proinflammatory role during chronic H. pylori infection, which was further supported by the decreased inflammation in H. pylori–infected CD8−/− mice. It has also been reported that MMP-2–mediated intestinal epithelial dysfunction was associated with a significant reduction in the tight junction protein claudin-5 (26), which resembles our data on ZO-1 regulation by MMP-10 in gastric epithelium. Specifically, our in vitro and in vivo data together provide a multistep model of chronic gastritis accompanied by H. pylori–persistent infection involving interactions between H. pylori, IL-22, gastric epithelial cells, MMP-10, and CD8+ T cells within the gastric mucosa (Fig. 6F).

Although eradication therapy for H. pylori by oral antibiotics has progressed in recent years (27, 28), it is noteworthy that chronic gastritis and H. pylori colonization commonly persist because of increased antimicrobial resistance. Treatments that can address the underlying inflammatory process may therefore be of clinical value in these cases. In this regard, our findings suggest a possible therapeutic target, MMP-10. At the same time, it will be interesting to test whether the MMP-10–associated proinflammatory cellular networks and molecular pathways described here for H. pylori–associated gastritis operate in other chronic infections where eradication is more difficult. If this is true, then targeting these molecular pathways may also prove to be of clinical benefit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and specimens

The gastric biopsy specimens and blood were collected from 96 H. pylori–infected and 42 uninfected patients who underwent upper esophagogastroduodenoscopy for dyspeptic symptoms at XinQiao Hospital (table S1). H. pylori infection was determined by [14C] urea breath test and rapid urease test of biopsy specimens taken from the antrum and subsequently conformed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and serology test for specific anti–H. pylori Abs (8). For isolation of human primary gastric epithelial cells, fresh nontumor gastric tissues (at least 5-cm distant from the tumor site) were obtained from patients with gastric cancer who underwent surgical resection and were determined as H. pylori–negative individuals, as described above, at the Southwest Hospital. None of these patients had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before sampling. Individuals with atrophic gastritis, hypochlorhydria, antibiotic treatment, autoimmune disease, infectious diseases, and multiprimary cancer were excluded. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of XinQiao Hospital and Southwest Hospital of Third Military Medical University. The written informed consent was obtained from each individual.

Antibodies and other reagents

Mice

All breeding and experiments were undertaken with review and approval from the Animal Ethical and Experimental Committee of Third Military Medical University (table S2). Through material transfer agreements, C57BL/6 MMP-10−/− mice were obtained from W. C. Parks (University of Washington, USA), and C57BL/6 IL-22−/− mice were obtained from W. Ouyang (Genentech). IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice and their littermate control (WT) mice were generated by cross-breeding with IL-22−/− and MMP-10−/− mice. C57BL/6 IL-17A−/− mice and C57BL/6 IFN-γ−/− mice were provided by R. A. Flavell (Yale University, USA). C57BL/6Rag1−/− and C57BL/6CD8−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, USA). All mice used in experiments were female except male mice for chimeric experiments and were viral Ab free for pathogenic murine viruses, negative for pathogenic bacteria including Helicobacter spp. and parasites, and were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in a barrier-sustained facility and provided with sterile food and water (8).

Bacteria culture and infection of mice with bacteria

H. pylori NCTC 11637 (cagA positive) (WT H. pylori) and cagA-knockout mutant H. pylori NCTC 11637 (ΔcagA) were grown in brain-heart infusion plates containing 10% rabbit blood at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions. For infecting mouse, bacteria were propagated in Brucella broth with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), with gentle shaking at 37°C under microaerobic conditions. After culture for 1 day, live bacteria were collected and adjusted to 109 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. The mice were fasted overnight and orogastrically inoculated twice at a 1-day interval with 3 × 108 CFU of bacteria. H. pylori infection status and H. pylori–induced gastritis in murine experiments were confirmed using real-time PCR of H. pylori 16S rDNA, urease biopsy assays, Warthin-Starry staining and immunohistochemical staining for H. pylori, and evaluation of inflammation by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (8).

Generation of BM mice

The following BM chimeric mice were created: male IL-22−/− BM→female MMP-10−/− mice and male MMP-10−/− BM→female IL-22−/− mice; or male WT BM→female IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice, male IL-22−/− BM→female IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice, male MMP-10−/− BM→female IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice, and male IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− BM→female IL-22−/−MMP-10−/− mice; or male WT BM→female WT mice, male WT BM→female MMP-10−/− mice, male MMP-10−/− BM→female WT mice, and male MMP-10−/− BM→female MMP-10−/− mice. BM cells were collected from the femurs and tibia of donor mice by aspiration and flushing and were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at the concentration of 5 × 107/ml. The BM in recipient mice was ablated with lethal irradiation (8 grays). Then, the animals intravenously received 1.5 × 107 BM cells from donor mice in a volume of 300-μl sterile PBS under the anesthesia. Thereafter, the transplanted BM was allowed to regenerate for 8 weeks before subsequent experimental procedures. To verify successful engraftment and reconstitution of the BM in the host mice, genomic DNA was isolated from tail tissues of each chimera mouse 8 weeks after BM transplantation. Quantitative PCR was performed to detect the Sry gene present in the Y chromosome (primers are shown in table S3) and mouse β2-microglobulin gene as an internal control. The chimeric rates were calculated on the assumption that the ratio of the Sry to β2-microglobulin gene was 100% in male mice. We confirmed that the chimeric rates were consistently higher than 90%. After BM reconstitution was confirmed, mice were infected with bacteria, as described above.

Abs/CXCL16/Reg3a administration

One day after infection with WT H. pylori as described above, WT mice were intraperitoneally injected with 25 μg of recombinant mouse CXCL16 or Reg3a or anti-mouse CXCL16 or isotype control Abs (100 μg) and repeated every week until the mice were euthanized; MMP-10−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with anti-mouse Reg3a or isotype control Abs (100 μg) and repeated every week until the mice were euthanized.

Evaluation of bacteria colonization

The mice were euthanized at the indicated times. The stomach was cut open from the greater curvature, and half of the tissue was cut into four parts for RNA extraction, DNA extraction, protein extraction, and tissue fixation for immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence staining. DNA of the biopsy specimens was extracted with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit. As previously described (29), H. pylori colonization was quantified by measuring H. pylori–specific 16S rDNA using a specific primer and probe (table S3) by the TaqMan method. The amount of mouse β2-microglobulin DNA in the same specimen was used to normalize the data. According to a previous study (30), the density of H. pylori was shown as the number of bacterial genomes per nanogram of host genomic DNA (7). Another half of the stomach was used for isolation of single cells, as described below. The isolated single cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry staining.

Evaluation of inflammation

Mice were euthanized at the indicated times. The greater curvature of the stomach was cut to perform H&E staining. The intensity of inflammation was evaluated independently by two pathologists according to previously established criteria (8, 31).

Isolation of single cells from tissues

Fresh tissues were washed three times with Hank’s solution containing 1% FBS, cut into small pieces, collected in RPMI 1640 containing collagenase IV (1 mg/ml) and deoxyribonuclease I (10 mg/ml), and then mechanically dissociated by using the gentle MACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). Dissociated cells were further incubated for 0.5 to 1 hour at 37°C under continuous rotation. The cell suspensions were then filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Labware).

Cell/tissue culture and stimulation

Primary gastric epithelial cells were purified from gastric tissue single-cell suspensions from uninfected donors or mice with a MACS column purification system using anti-human or mouse CD326 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). The sorted primary gastric epithelial cells were used only when their viability was determined >90% and their purity was >95%. For human gastric epithelial cell lines (AGS cells, GES-1 cells, BGC-823 cells, HGC-27 cells, and SGC-7901 cells), 3 × 105 cells per well in a 12-well cell culture plate (for real-time PCR) or 1 × 106 cells per well in a 6-well cell culture plate [for Western blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)] were starved in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium)/F-12 medium supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) for 6 hours in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Then, the cells were incubated in antibiotic-free DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS instead. The cell lines were used when their viability was determined >90%. Human gastric epithelial cell lines, primary gastric epithelial cells, or primary gastric mucosa tissues from uninfected donors were stimulated with WT H. pylori or ΔcagA at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 for 24 hours. AGS cells, primary gastric epithelial cells, or primary gastric mucosa tissues were also stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and/or IL-22 (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of neutralizing Abs against IL-22 (20 μg/ml) and/or IL-22R1 (20 μg/ml) for 24 hours. AGS cells were also stimulated with WT H. pylori at different MOI (24 hours) or at the indicated time points (MOI = 100), stimulated with WT H. pylori (MOI = 100) and/or IL-22 (100, 200, and 400 ng/ml), IFN-γ, or IL-17A (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours, or stimulated with ΔcagA (MOI = 100) and/or IL-22 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. For signal pathway inhibition experiments, AGS cells were pretreated with 5 μl (20 μM) of glycogen synthase kinase–3β inhibitor, BAY 11-7082 (a nuclear factor κB inhibitor), SP600125 (a c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor), SB203580 (a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor), U0126 [an MEK-1 (MAPK kinase–1) and MEK-2 inhibitor], or U0126 (5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 μM) for 2 hours. For MMP-10 inhibition experiments, AGS cells were pretreated with MMP-10 siRNA, NC siRNA (40 nM), or Lipo3000 only (Mock) for 24 hours. After coculture, cells were collected for microarray, real-time PCR, and Western blot, and the culture supernatants were harvested for ELISA.

For transwell assays, AGS cell density was adjusted to 3 × 105 cells/ml, and a total of 600 μl of cell suspension in serum-free DMEM/F-12 medium was added to the lower chamber for 6 hours. The cells were then incubated in 600 μl of antibiotic-free DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. In one group, WT H. pylori (in 100 μl of antibiotic-free DMEM/F-12 medium at a MOI of 100) was placed into the lower chambers of the transwells (0.4-μm pore). In another group, the same WT H. pylori was placed into the upper chambers, and equal quantity of medium without WT H. pylori was added into the lower chambers. After incubation for 24 hours at 37°C, the culture supernatants were harvested for ELISA.

In vitro bactericidal assay

Two hundred microliters of 105 CFU/ml WT H. pylori suspension was incubated with human Reg3a (30 μg/ml) for 24 hours. The PBS was used as control. Bacteria were serially diluted and plated on brain-heart infusion plates containing 10% rabbit blood and incubated for 3 to 5 days at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions before enumeration. CFUs were enumerated at 37°C for 3 to 5 days after plating.

Casein zymography assay

AGS cells were stimulated with WT H. pylori or ΔcagA at a MOI of 100 for 24 hours. The culture supernatants were harvested and centrifuged for casein zymography according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, equal volumes of the cell culture supernatant and gel-loading buffer were mixed under nonreducing conditions without heating; the mixed samples were then loaded onto gels (copolymerized with a casein substrate) and separated by electrophoresis. Following electrophoresis, the gels were transferred into a renaturation buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Then, the gels were put into a digestion buffer for 4 hours at 37°C under gentle agitation. As MMP-10 triggers degradation of the substrate, it is therefore possible to analyze its proenzyme and active form. When the gels were stained, the digested areas appear as clear bands against a blue background.

Chemotaxis assay

CD8+ T cells from blood of H. pylori–infected donors or WT H. pylori–infected mice (9 weeks p.i.) were sorted using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) (FACSAria II, BD Biosciences). AGS cells were pretreated with MMP-10 siRNA, NC siRNA (both at 40 nM), or Lipo3000 only (Mock) for 24 hours and then stimulated with WT H. pylori or ΔcagA (MOI = 100) for 24 hours. The culture supernatants were collected and used as source of chemoattractants in a human CD8+ T cell chemotaxis assay. In another set of experiments, mouse primary gastric epithelial cells were purified from gastric tissue single-cell suspensions of uninfected mice with a MACS column purification system using anti-mouse CD326 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and then stimulated with WT H. pylori or ΔcagA (MOI = 100) for 24 hours. The culture supernatants were collected, as mentioned above. These culture supernatants were then used as chemoattractants in a mouse CD8+ T cell chemotaxis assay.

In a chemotaxis assay, sorted CD8+ T cells (2 × 105) were transferred into the upper chambers of transwells (5-μm pore). CXCL16 (100 ng/ml) and culture supernatants from various cultures were placed in the lower chambers. After 6-hour culture, migration was quantified by counting cells in the lower chamber and cells adhering to the bottom of the membrane. In some cases, blocking Ab for CXCL16 (20 μg/ml) or corresponding control immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a; 20 μg/ml) was added into culture supernatants before chemotaxis assay.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded samples were cut into 5-μm sections. For immunohistochemical staining, the sections were incubated with rabbit anti-human or mouse MMP-10, mouse anti-human CD8, or rabbit anti-human Reg3a, followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and, later, its substrate diaminobenzidine or Polymer Double Dyeing Detection kit (Mo/HRP + Rb/AP). All the sections were lastly counterstained with hematoxylin and examined using a microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i, Nikon).

Immunofluorescence

Paraformaldehyde-fixed cryostat tissue sections were washed in PBS, blocked for 30 min with 20% goat serum in PBS, stained for MMP-10 and H+/K+ ATPase, MMP-10 and pepsinogen II, or MMP-10 and H. pylori. Slides were examined with a confocal fluorescence microscope (LSM 510 META, Zeiss).

Real-time PCR

DNA of the biopsy specimens was extracted with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, and RNA of biopsy specimens and cultured cells were extracted with TRIzol reagent. The RNA samples were reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA with the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit. Real-time PCR was performed on an iQ5 (Bio-Rad) with Real-time PCR Master Mix according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The mRNA expression of 16S rDNA, cagA, MMP-10, IL-22, chemokine, β-defensin, and Reg3 genes was measured using the TaqMan and/or SYBR green method with the relevant primers (table S3). For mice, mouse β2-microglobulin mRNA level served as a normalizer, and its level in the stomach of uninfected or WT mice served as a calibrator. For human, human β-actin mRNA level served as a normalizer, and its level in the unstimulated cells or stomach of uninfected donors served as a calibrator. The relative gene expression was expressed as fold change of relevant mRNA calculated by the ΔΔCt method.

Flow cytometry

Cell surface markers were stained with specific or isotype control Abs and analyzed by multicolor flow cytometry on a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star) or FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Isolated human and mouse gastric tissues were homogenized in 1 ml of sterile protein extraction reagent and centrifuged. Tissue supernatants were collected for ELISA. Concentrations of CXCL16 and Reg3a in the tissue supernatants and concentrations of MMP-10 and CXCL16 in the gastric epithelial cell culture supernatants or tissue culture supernatants were determined using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed on 10 to 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel–transferred polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes with equivalent amounts of cell or tissue lysate proteins for each sample. Five percent skim milk was used for blocking the PVDF membranes. Mouse MMP-10, E-cadherin, and ZO-1 were detected with rabbit anti–MMP-10 Abs, mouse anti–E-cadherin Abs, and rabbit anti–ZO-1 Abs; human MMP-10, ERK1/2, and p-ERK1/2 were detected with rabbit anti–MMP-10 Abs, rabbit anti-ERK1/2 Abs, and rabbit anti–p-ERK1/2 Abs, respectively. This was followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary Abs. Bound proteins were visualized by using a SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate kit.

MMP array

MMP protein profiles of human primary gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected and uninfected donors were analyzed with the Proteome Profiler Human Protease Array Kit (ARY021B, R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, an equivalent amount (about 0.3 mm3) of human primary gastric mucosa from H. pylori–infected patients and paired uninfected donors was homogenized in 0.2-ml sterile protein extraction reagent and centrifuged. Quantitation of sample protein concentration was achieved by bicinchoninic acid total protein assay. First, each membrane was incubated in an array blocking buffer for 1 hour on a rocking platform. Then, 15 μl of reconstituted protease-detecting Ab cocktail was added to each prepared sample at room temperature for 1 hour. Array blocking buffer was then removed from the wells, and the preprepared sample/Ab mixtures were added to the corresponding membrane and incubated overnight at 4°C. Each membrane was then washed three times with washing buffer before being incubated with streptavidin-HRP for 30 min at room temperature and then developed with 1 ml of the prepared chemi reagent mix for 1 min.

Microarray experiments

Gene expression profiles of WT H. pylori–infected and uninfected AGS cells were analyzed with the Human Exon 1.0 ST GeneChip (Affymetrix), strictly following the manufacturer’s protocol. Microarray experiments were performed at the Genminix Informatics (China) with the microarray service certified by Affymetrix.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Student’s t test was generally used to analyze the differences between two groups, but when the variances differed, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Inflammation score data were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations between parameters were assessed using Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression analysis, as appropriate. SPSS statistical software (version 13.0) was used for all statistical analysis. All data were analyzed using two-tailed tests, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Microarray data analysis was performed with the assistance of Genminix Informatics. Raw data from each array were analyzed using TwoClassDif.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670510) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1302200). Ethics statement: The biopsy specimens were obtained under protocols approved by the ethics committees of XinQiao Hospital and Southwest Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. All animal experiments were undertaken with approval from the Animal Ethical and Experimental Committee of Third Military Medical University. Author contributions: Conception and design, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript: Y.Z. Manuscript revision: Y.Z. and W.C. Statistical analysis: Y.Z., Y.-p.L., P.C., J.-y.Z., Y.-s.T., F.-y.M., Y.-g.L., H.K., X.-l.W., and C.-j.H. Obtained funding: Y.Z. Technical support: B.H., Q.M., S.-m.Y., L.-s.P., T.-t.W., and Q.-m.Z. Final approval of submitted version: Y.Z. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/4/eaau6547/DC1

Fig. S1. MMP-10 is increased in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients and mice.

Fig. S2. H. pylori and IL-22 synergistically induce gastric epithelial cells to express MMP-10.

Fig. S3. MMP-10 increases bacterial burden and inflammation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

Fig. S4. MMP-10 promotes CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo during H. pylori infection.

Fig. S5. MMP-10 promotes CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo during H. pylori infection.

Fig. S6. MMP-10 promotes CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo and migration in vitro during H. pylori infection by CXCL16.

Fig. S7. MMP-10 impairs host defense and promotes the damage of gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

Table S1. Clinical characteristics of patients.

Table S2. Antibodies and other reagents.

Table S3. Primer and probe sequences for real-time PCR analysis.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hooi J. K. Y., Lai W. Y., Ng W. K., Suen M. M. Y., Underwood F. E., Tanyingoh D., Malfertheiner P., Graham D. Y., Wong V. W. S., Wu J. C. Y., Chan F. K. L., Sung J. J. Y., Kaplan G. G., Ng S. C., Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 153, 420–429 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassim S. Y., Gharib S. A., Mecham B. H., Birkland T. P., Parks W. C., McGuire J. K., Individual matrix metalloproteinases control distinct transcriptional responses in airway epithelial cells infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 75, 5640–5650 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behera A. K., Hildebrand E., Scagliotti J., Steere A. C., Hu L. T., Induction of host matrix metalloproteinases by Borrelia burgdorferi differs in human and murine lyme arthritis. Infect. Immun. 73, 126–134 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorente L., Martín M. M., Labarta L., Díaz C., Solé-Violán J., Blanquer J., Orbe J., Rodríguez J. A., Jiménez A., Borreguero-León J. M., Belmonte F., Medina J. C., Llimiñana M. C., Ferrer-Agüero J. M., Ferreres J., Mora M. L., Lubillo S., Sánchez M., Barrios Y., Sierra A., Páramo J. A., Matrix metalloproteinase-9, -10, and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 blood levels as biomarkers of severity and mortality in sepsis. Crit. Care 13, R158 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa A. M., Ferreira R. M., Pinto-Ribeiro I., Sougleri I. S., Oliveira M. J., Carreto L., Santos M. A., Sgouras D. N., Carneiro F., Leite M., Figueiredo C., Helicobacter pylori activates matrix metalloproteinase 10 in gastric epithelial cells via EGFR and ERK-mediated pathways. J. Infect. Dis. 213, 1767–1776 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amieva M., Peek R. M. Jr., Pathobiology of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 150, 64–78 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y., Liu X. F., Zhuang Y., Zhang J. Y., Liu T., Yin Z., Wu C., Mao X. H., Jia K. R., Wang F. J., Guo H., Flavell R. A., Zhao Z., Liu K. Y., Xiao B., Guo Y., Zhang W. J., Zhou W. Y., Guo G., Zou Q. M., Helicobacter pylori-induced Th17 responses modulate Th1 cell responses, benefit bacterial growth, and contribute to pathology in mice. J. Immunol. 184, 5121–5129 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuang Y., Cheng P., Liu X. F., Peng L. S., Li B. S., Wang T. T., Chen N., Li W. H., Shi Y., Chen W., Pang K. C., Zeng M., Mao X. H., Yang S. M., Guo H., Guo G., Liu T., Zuo Q. F., Yang H. J., Yang L. Y., Mao F. Y., Lv Y. P., Zou Q. M., A pro-inflammatory role for Th22 cells in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. Gut 64, 1368–1378 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromley S. K., Mempel T. R., Luster A. D., Orchestrating the orchestrators: Chemokines in control of T cell traffic. Nat. Immunol. 9, 970–980 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer B., Pang E., Holland C., Kessler M., Bartfeld S., Meyer T. F., The Helicobacter pylori virulence effector CagA abrogates human β-defensin 3 expression via inactivation of EGFR signaling. Cell Host Microbe 11, 576–586 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshino N., Ishihara S., Rumi M. A. K., Ortega-Cava C. F., Yuki T., Kazumori H., Takazawa S., Okamoto H., Kadowaki Y., Kinoshita Y., Interleukin-8 regulates expression of Reg protein in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 2157–2166 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokolova O., Vieth M., Naumann M., Protein kinase C isozymes regulate matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression and cell invasion in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 62, 358–367 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford H. C., Krishna U. S., Israel D. A., Matrisian L. M., Washington M. K., Peek R. M. Jr., Helicobacter pylori strain-selective induction of matrix metalloproteinase-7 in vitro and within gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology 125, 1125–1136 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montero I., Orbe J., Varo N., Beloqui O., Monreal J. I., Rodríguez J. A., Díez J., Libby P., Páramo J. A., C-reactive protein induces matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -10 in human endothelial cells: Implications for clinical and subclinical atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 1369–1378 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishikawa F., Miyoshi H., Nose K., Shibanuma M., Transcriptional induction of MMP-10 by TGF-β, mediated by activation of MEF2A and downregulation of class IIa HDACs. Oncogene 29, 909–919 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkins-Port C. E., Ye Q., Mazurkiewicz J. E., Higgins P. J., TGF-β1 + EGF-initiated invasive potential in transformed human keratinocytes is coupled to a plasmin/MMP-10/MMP-1–dependent collagen remodeling axis: Role for PAI-1. Cancer Res. 69, 4081–4091 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyat M., Bouzourene H., Ouyang W., Iovanna J., Renauld J. C., Velin D., IL-22-induced antimicrobial peptides are key determinants of mucosal vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 271–281 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murao T., Okamoto R., Ito G., Nakata T., Hibiya S., Shimizu H., Fujii S., Kano Y., Mizutani T., Yui S., Akiyama-Morio J., Nemoto Y., Tsuchiya K., Nakamura T., Watanabe M., Hes1 promotes the IL-22-mediated antimicrobial response by enhancing STAT3-dependent transcription in human intestinal epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 443, 840–846 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Rodriguez V., Orbe J., Martinez-Aguilar E., Rodriguez J. A., Fernandez-Alonso L., Serneels J., Bobadilla M., Perez-Ruiz A., Collantes M., Mazzone M., Paramo J. A., Roncal C., Functional MMP-10 is required for efficient tissue repair after experimental hind limb ischemia. FASEB J. 29, 960–972 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Irigoyen O., Latasa M. U., Carotti S., Uriarte I., Elizalde M., Urtasun R., Vespasiani-Gentilucci U., Morini S., Benito P., Ladero J. M., Rodriguez J. A., Prieto J., Orbe J., Páramo J. A., Fernández-Barrena M. G., Berasain C., Avila M. A., Matrix metalloproteinase 10 contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis in a novel crosstalk with the stromal derived factor 1/C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 axis. Hepatology 62, 166–178 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koller F. L., Dozier E. A., Nam K. T., Swee M., Birkland T. P., Parks W. C., Fingleton B., Lack of MMP10 exacerbates experimental colitis and promotes development of inflammation-associated colonic dysplasia. Lab. Invest. 92, 1749–1759 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barksby H. E., Milner J. M., Patterson A. M., Peake N. J., Hui W., Robson T., Lakey R., Middleton J., Cawston T. E., Richards C. D., Rowan A. D., Matrix metalloproteinase 10 promotion of collagenolysis via procollagenase activation: Implications for cartilage degradation in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 3244–3253 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu Y., Ivashkiv L. B., Costimulation of chemokine receptor signaling by matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates enhanced migration of IFN-α dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 176, 6022–6033 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garg P., Ravi A., Patel N. R., Roman J., Gewirtz A. T., Merlin D., Sitaraman S. V., Matrix metalloproteinase-9 regulates MUC-2 expression through its effect on goblet cell differentiation. Gastroenterology 132, 1877–1889 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan M. P., Pedersen J., Zhan Y., Lew A. M., Pearse M. J., Wijburg O. L., Strugnell R. A., CD8+ T cells are associated with severe gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice in the absence of CD4+ T cells. Infect. Immun. 76, 1289–1297 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groschwitz K. R., Wu D., Osterfeld H., Ahrens R., Hogan S. P., Chymase-mediated intestinal epithelial permeability is regulated by a protease-activating receptor/matrix metalloproteinase-2-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 304, G479–G489 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molina-Infante J., Romano M., Fernandez-Bermejo M., Federico A., Gravina A. G., Pozzati L., Garcia-Abadia E., Vinagre-Rodriguez G., Martinez-Alcala C., Hernandez-Alonso M., Miranda A., Iovene M. R., Pazos-Pacheco C., Gisbert J. P., Optimized nonbismuth quadruple therapies cure most patients with Helicobacter pylori infection in populations with high rates of antibiotic resistance. Gastroenterology 145, 121–128.e1 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W., Chen Q., Liang X., Liu W., Xiao S., Graham D. Y., Lu H., Bismuth, lansoprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole or clarithromycin as first-line Helicobacter pylori therapy. Gut 64, 1715–1720 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roussel Y., Wilks M., Harris A., Mein C., Tabaqchali S., Evaluation of DNA extraction methods from mouse stomachs for the quantification of H. pylori by real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 62, 71–81 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikula M., Dzwonek A., Jagusztyn-Krynicka K., Ostrowski J., Quantitative detection for low levels of Helicobacter pylori infection in experimentally infected mice by real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 55, 351–359 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrero R. L., Avé P., Ndiaye D., Bambou J. C., Huerre M. R., Philpott D. J., Mémet S., NF-κB activation during acute Helicobacter pylori infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 76, 551–561 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/4/eaau6547/DC1

Fig. S1. MMP-10 is increased in gastric mucosa of H. pylori–infected patients and mice.

Fig. S2. H. pylori and IL-22 synergistically induce gastric epithelial cells to express MMP-10.

Fig. S3. MMP-10 increases bacterial burden and inflammation in gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

Fig. S4. MMP-10 promotes CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo during H. pylori infection.

Fig. S5. MMP-10 promotes CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo during H. pylori infection.

Fig. S6. MMP-10 promotes CD8+ T cell accumulation in gastric mucosa in vivo and migration in vitro during H. pylori infection by CXCL16.

Fig. S7. MMP-10 impairs host defense and promotes the damage of gastric mucosa during H. pylori infection.

Table S1. Clinical characteristics of patients.

Table S2. Antibodies and other reagents.

Table S3. Primer and probe sequences for real-time PCR analysis.