Abstract

We present a fluorescence-based methodology for monitoring the rotational dynamics of Nanodiscs. Nanodiscs are nano-scale lipid bilayers surrounded by a helical membrane scaffold protein (MSP) that have found considerable use in studying the interactions between membrane proteins and their lipid bilayer environment. Using a long-lifetime Ruthenium label covalently attached to the Nanodiscs, we find that Nanodiscs of increasing diameter, made by varying the number of helical repeats in the MSP, display increasing rotational correlation times. We also model our system using both analytical equations that describe rotating spheroids and numerical calculations performed on atomic models of Nanodiscs. Using these methods, we observe a linear relationship between the experimentally determined rotational correlation times and those calculated from both analytical equations and numerical solutions. This work sets the stage for accurate, label-free quantification of protein-lipid interactions at the membrane surface.

I. Introduction to Nanodiscs.

Modern technology has provided a plethora of methodologies for investigating the structure and function of proteins and protein assemblies. Unfortunately, most of these approaches applied to membrane proteins have significant limitations. Proteins reconstituted using mild detergents may not structurally resemble their native conformations1. While sometimes partial activity can be realized by adding a small amount of lipid or loosening the structure with detergent, the reality is that the membrane protein does not find itself in its normal bilayer environment, can be aggregated, and hence often displays altered or absent function.

There are now several approaches to deal with the challenges in investigating membrane proteins as has been recently reviewed2. Historically, membrane proteins have been reconstituted into liposomes or studied in micelles, and in some cases truncated proteins were used to aid reconstitution. Roughly fifteen years ago a new method was introduced wherein a detergent solubilized membrane protein and phospholipid were mixed with an amphipathic helical protein derived from ApoAI3. When the detergent was removed by dialysis, or treatment with hydrophobic beads, self-assembly ensued wherein the target ended up embedded in a bilayer, in the correct configuration, with the entire discoidal particle rendered soluble via two encircling wraps of the amphipathic protein belt. This amphipathic protein was termed a “membrane scaffold protein”, or MSP, and took it sequence from the well-known literature of human Apo-AI lipoprotein structure4,5. However, the function of the full-length Apo-AI is to target a spherical ball of lipid, cholesterol and cholesterol esters. Genetic engineering of the Apo-AI protein, involving removing the globular head domain and part of the core protein sequence, yielded a membrane scaffold protein (MSP) that is optimized for forming homogeneous and monodisperse discoidal bilayers6. Various tags, including His, FLAG, biotin as well as engineered labeling sites together with larger discoidal bilayers generated by adding or subtracting helical segments followed. The resultant structures were termed Nanodiscs, with a capitalized “N” reflecting early copyrighting. Since this discovery, alternate protein sequences, and even short amphipathic peptide fragments have been used to render membrane proteins soluble in a bilayer environment7,8. In many recent publications, the targets in these structures are also called “nanodiscs”, and hence to be clear, we have retained the capital “N” in Nanodisc to reflect those true bilayers that are formed with MSPs. SMALPs and other peptide-based methods are described in several articles in this special issue. Although a full review of these kinds of nanodiscs is beyond the scope of this manuscript, various peptide and polymer-based nanodiscs have also been described for solubilizing membranes and reconstituting membrane proteins9–13 and are discussed in further detail elsewhere in this special issue.

While one cannot vary the diameter of Nanodiscs continuously, Nanodiscs can be made with diameters from 6nm14 to 17nm15 by using MSPs with different numbers of helical repeats. Interactions between the target protein and the Nanodisc (e.g. depth of insertion or distance to the MSP belt) can be assessed with structural techniques such as SAXS16,17. As the MSP is an engineered amphipathic helical protein, the pH of the solution must be kept near physiological pH.

When used in concentrations near 1mM, divalent metal ions (Ca2+, Mg2+) can form a cationic bridge between phospholipid head groups and a negatively charged surface such as mica, resulting in Nanodisc adsorption to the surface. This has been used for surface-based studies such as atomic force microscopy18. At high concentrations (>10mM), divalent metal ions may also bridge zwitterionic lipid head groups of different Nanodiscs, resulting in stacking interactions.

The use of Nanodiscs in the study of membrane proteins has exploded over the past few years. The MSPs used herein are readily obtainable from commercial suppliers (e.g. Sigma-Aldrich) and the genes for producing MSPs via simple E. coli fermentation are available from AddGene (to date over 1500 samples have been shipped to academics world-wide). Nanodiscs are available with varying sizes, from ~ 6 nm to ~ 17 nm in diameter, and any number of native and synthetic phospholipid compositions are possible. Incorporating a membrane protein target into Nanodiscs is a simple process of self-assembly, as has been reviewed in detail in many recent articles2,19,20. Successfully incorporated targets include monomeric and dimeric GPCRs21–23, multicomponent transporters24,25, monomeric enzymes26 and trans-membrane signaling complexes27. Importantly, since the membrane protein finds itself in a native like lipid environment, full functionality is realized as well as increased stability. The Nanodisc embedded target can be affixed to a sensor surface or investigated by any of the biochemical and biophysical methods previously reserved for soluble proteins. High resolution structures of membrane proteins have been obtained by NMR28 and by cryo-electron microscopy29–31. Topologies and dynamics have been explored by isotope exchange and various fingerprinting methods32–36. A careful summary of these success has been extensively reviewed recently2,19,20.

II. Nanodiscs as a sensing platform.

An important feature of Nanodisc incorporated membrane proteins is that they preserve the native structure and activity that is found in their native bilayer home. A second important advantage is the robustness of the nanoparticle, allowing the Nanodisc to be sorted via droplet or microfluidic methods or affixed to a sensor surface. These methodologies have also been reviewed recently37, and we will only describe the already completed work that forms a background for the new methods presented subsequently.

Many examples exist wherein Nanodiscs and a self-assembled target have been used to quantitate the binding of small molecules or other proteins. Important in these experiments has been the ability to affix the Nanodisc complex to a sensor surface. Multiple approaches have been used, most commonly using a poly-histidine sequence on the amino or carboxy terminus of the encircling membrane scaffold protein (MSP). Other genetically encoded tags such as FLAG, cMyc, RGD etc. have also been used. An alternative is to utilize a biotin label on the MSP, either chemically attached to a unique cysteine residue engineered into the sequence (D73C is commercially available). Alternatively, the MSP sequence has been extended to add a specific recognition sequence for the E. coli biotinylation machinery. As there are two antiparallel MSP belts, these approaches normally put two attachment sites on each Nanodisc, although self-assembly with an unmodified MSP can result in a singly labeled entity. Other labels can be attached to the unique cysteine site, including specific DNA sequences.

With poly-histidine and biotin tags, commonly available sensor platforms for surface plasmon resonance (SPR) are readily available. Even small molecular weight compound binding to the large Nanodisc-target complex can be monitored by SPR34 or larger macromolecules and antibodies38.

An important use of Nanodiscs that is becoming very popular utilizes the discoidal surface to quantitate the binding and assembly of macromolecular complexes. Nanodiscs can be prepared with defined lipid composition, varying the head group structure and charge39,40. The choice of overall diameter (from ~ 6 nm to ~ 17 nm) provides a surface of 17–170 square nanometers. The number of lipids packed into the disc depends on head group and chain length as described6. With full packing the membrane surface is essentially flat and discoidal, and hence this system has yet to provide a means to generate defined bilayer curvature. Extensive molecular dynamics studies41 and experiments42,43 have shown the overall motions of the Nanodisc, including cases where less than optimal lipid packing can generate ellipsoidal shapes characterized by an increase in “drum head” oscillatory motions of the bilayer. It is worth noting that there has not yet been described a means for generating Nanodiscs with asymmetric leaflet compositions.

A plethora of sensor modalities have successfully utilized Nanodiscs to stabilize a membrane protein and allow different means for affixing to the detecting surface. These include monitoring via cantilever detection44, arrays generated on silicon based ring resonators45,46, and many investigations by surface plasmon resonance34,47. Such surface-based methods, as well as radio labeled techniques, NMR relaxation, thermophoresis, mass spectrometry, atomic force microscopy48 and differential labeling were recently reviewed extensively2,37.

One of the most powerful methodologies uses the sensitivity and selectivity of fluorescence-based methods. Resonance energy transfer (FRET) based approaches use a binding component and a labeled membrane scaffold protein (MSP) to form a donor-acceptor pair23. An important example was the extensive studies of talin, an important integrin activator, and its interaction with anionic lipids, and the role of the phospholipid in the mechanism of autoinhibition by the talin rod domain49,50. Here a donor was attached to an engineered cysteine residue on the MSP with a dark quencher on the talin head domain, allowing quick and reliable binding studies23,50. Given the stability of the Nanodisc in solution, it is natural to ask if the rotational motion of the entire disk can be monitored by fluorescence polarization methods. This could allow the target and binding partner to be label-free and yet provide a sensitive probe of affinity and structure.

Rotational motion of Nanodisc-protein complexes has also been investigated by NMR. Early attempts at using NMR with Nanodiscs were hindered by their relatively large size, which caused line broadening and poor signal quality due to the slow overall rotational motion of the Nanodisc-protein complex. Hagn et al. generated truncated MSPs by deleting one or more helical repeats, which led to high-resolution NMR spectra and the structure of outer membrane protein X (OmpX), the first integral membrane protein (IMP) structure assigned in Nanodiscs28. This work was followed by further structural characterization of various IMPs using a combination of 2D NMR and TRACT experiments to measure chemical shifts and rotational dynamics of Nanodisc-IMP complexes51–53. Solid-state NMR can also be used to study larger protein-lipid complexes, and has been used to characterize discoidal apo-AI secondary structure54.

Measured rotational correlation times vary with the size of the MSP, IMP, and temperature28,51,52,55 (Table 1). Because NMR requires fast tumbling times, spectra are usually recorded at relatively high temperatures. A short correlation time of 27ns corresponds to the overall rotation of MSP1D1ΔH4H5 Nanodiscs loaded with OmpX, while bacteriorhodopsin (bR) reconstituted in MSP1D1 Nanodiscs measures 86ns28. Although IMPs may not project as far from the membrane as peripheral proteins, it is interesting to note that there is still a measurable difference in the rotational correlation time of Nanodiscs made with identical MSPs loaded with different IMPs. Dutta et al. report apparent changes in rotational correlation time as a function of disc-protein concentration, presumably due to protein-protein interactions between different IMP-Nanodisc complexes52. These results suggest that the overall rotational dynamics of Nanodisc-protein complexes are sensitive to changes in the size of the ensemble.

Table 1:

Rotational correlation times of various Nanodisc-IMP complexes measured by NMR. All spectra used to obtain this data were taken at 45°C. Two values were reported for MSP1D1ΔH5-Ail (Adhesion invasion locus); we list the value obtained at [Ail] = 0.66 mM52.

| MSP | IMP | Correlation Time (ns) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44–243 apoA-1 fragment | Aam-I | 40 | 45 |

| MSP1D1AH4H5 | OmpX | 27 | 17 |

| MSP1D1AH5 | OprHAL1AL4 | 32 | 41 |

| MSP1D1AH5 | OmpX | 34 | 17 |

| MSP1D1AH5 | Ail (0.66 mM) | 35.4 | 42 |

| MSP1D1AH5 | bR | 60 | 17 |

| MSP1D1 | OmpX | 48 | 17 |

| MSP1D1 | bR | 86 | 17 |

The remainder of this article provides an extensive description of the rotational dynamics of Nanodiscs. We will see that even a small change in the diameter of the Nanodisc can be accurately detected.

III. A new assay tool: Free rotational motion of Nanodiscs.

We present here a new assay system that makes use of the hydrodynamic motion of Nanodiscs to monitor the association of proteins to the membrane surface, first described in 201756. The rotational diffusion of small molecules and proteins in solution is well understood, and multiple analysis methods have been described57–59. The Nanodisc system is well approximated by a solid disk with two x,y degenerate rotational axis as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Diagram of the principle axes of Nanodiscs (left) and the oblate spheroid approximation (right) with two degenerate axes.

Additionally, at the mass and time scales of interest, all inertial components of the rotational motion have been damped by solvent collisions. The total mass of the object is thus of less importance and one only needs to consider the overall shape of the Nanodisc. The shape can change dramatically when macromolecule targets bind to the membrane surface or more subtly as the diameter increases with added helical repeats of the MSP.

Modeling via oblate spheroid as shown in the figure can simplify the analysis. The axial ratio of an ellipsoid is related to the anisotropic and isotropic diffusion coefficients via the well-known equations60:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

| (4) |

with ρ being the axial ratio and D being the isotropic diffusion constant.

The overall hydrodynamic radii define the isotropic diffusion coefficients according to the Stokes-Einstein relation. Once the anisotropic diffusion coefficients are in hand, one can directly calculate the rotational correlation times:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

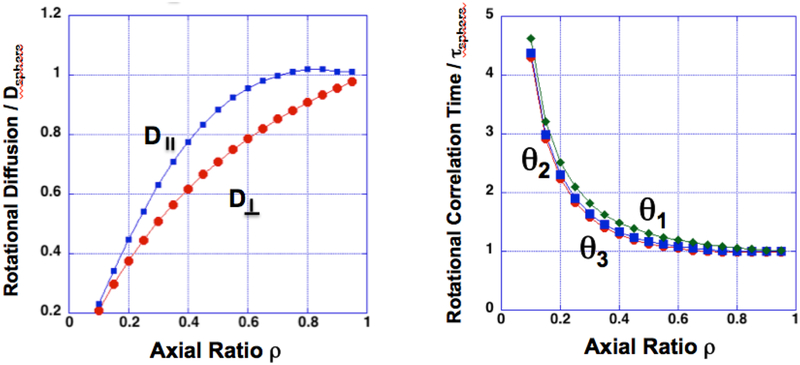

Interestingly, the two rotational diffusion coefficients for an oblate spheroid map to three rotational correlation times, but these three parameters are nearly identical for most axial ratios (Figure 2). To compare these values to experiment and other modeling techniques, we have chosen to use the harmonic mean correlation time as a benchmark of model performance. This both simplifies the comparisons and reflects the difficulty of resolving closely-spaced rotations in experiments.

Figure 2:

Comparison of anisotropic diffusion coefficients and rotational correlation times for an oblate spheroid, as a function of the axial ratio. Values are given relative to their isotropic counterparts. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements discussed below allow one to relate such correlation times to experimentally measured anisotropy decays.

An alternative analysis approach is to describe the motion of an arbitrarily shaped molecule with a diffusion tensor, whose diagonal entries are the diffusion coefficients about the molecule’s x, y, and z axes. From these diffusion coefficients one can directly calculate the expected rotational correlation times, although in practice one cannot usually distinguish these experimentally. Determining the anisotropic diffusion tensor of a biomolecule is not trivial but can be accomplished via programs such as HYDROPRO61. HYDROPRO creates a shell or bead-based model from a molecular structure file (PDB) and then calculates several diffusion and scattering properties. The shell-based model, which is used to model Nanodiscs in this work, is built from a shell of non-overlapping beads that covers the outer surface of the molecule. In our case the structure file used is an all-atom PDB file of a Nanodisc. Calculations are performed for decreasing bead radii and the results are extrapolated out to a radius of 0. In this way one can recover the radius of gyration, full diffusion tensor, and various rotational relaxation times.

It is also possible to estimate the full diffusion tensor from molecular dynamics simulations. All atom simulations are preferable, as many coarse-grained approaches do not parameterize water realistically, which might adversely affect the simulated rotational behavior at the solvent interface. This method involves computing rotation matrices that connect subsequent time frames of the simulation. It is convenient to describe the resultant motions in the form of quaternions, as they simplify the mathematical treatment. An account of the theory and comparisons between this modeling and experimental data has been given62. This method has been successfully applied to small soluble proteins such as myoglobin and asymmetric molecules such as DNA63. Unfortunately, this technique demands long simulations to capture the rotational dynamics of the molecule of interest. Nanodisc complexes with protein exhibit much larger correlation times than those of small proteins, which compounds the problem. The computing power required to perform such simulations (one to several weeks of supercomputing time) renders this method unattractive for the routine analysis of macromolecular binding to Nanodiscs. We thus utilize HYDROPRO to calculate rotational dynamics for various Nanodiscs and compare this result with values obtained via ellipsoid modeling.

To show the value of this approach, we demonstrate that fluorescence depolarization experiments can provide a sensitive probe of the rotational dynamics of Nanodiscs of various sizes. We have already applied this method to study protein binding to Nanodiscs56,64; together, these studies highlight the use of depolarization for probing rotational motion and protein-membrane interactions with Nanodiscs.

IV. Fluorescence methods to monitor dynamic motion of Nanodiscs

Molecular motion quantitated by changes in the polarization of emitted light from an attached fluorophore has been the basis of numerous biochemical assays for over a century. Much of the pioneering work was conducted by Weber65 and a concise history provided recently by Jameson66. Numerous textbooks and review articles are available, perhaps one of the most utilized is the latest version by Lakowicz which discusses all aspects of fluorescence methodology67. A major advance in the quantitation of fluorescence polarization and anisotropy decay was realized by Weber and colleagues65 by moving the measurement into the frequency domain. Here the incident light, polarized vertically, is modulated at a frequency ω and the intensity of horizontally and vertically polarized emission observed at right angles. The sample emission is delayed due to the length of the excited state lifetime. This results in a phase shift and demodulation between the excitation and emission as shown in Figure 3. The relationships between the phase shift and modulation of the emitted light and the lifetime are given by68:

| (8) |

| (9) |

where ϕω is the phase shift measured at frequency ω, τ is the lifetime, and mω is the modulation ratio between the emitted and incident light.

Figure 3:

Diagram of the change in phase and modulation of intensity-modulated light that occur during frequency-domain fluorometry measurements (blue: incident light, red: emitted light). The original description of phase fluorometry was given by Weber65.

Once the lifetimes are known, one can perform a separate experiment to measure rotational motions. Absorption of light ultimately places a fluorophore in an excited singlet state, and if the incident light is linearly polarized, photoselects an orientation for the emitting dipole moment. If emission occurs prior to any rotational motion, the fluorescence will favor the incident polarization, assuming excitation and emission dipoles are collinear. If, however, the molecule undergoes rotational motion, the emission is depolarized. Clearly there is a relationship between the excited state lifetime and the rotational correlation time60. For a large object this necessitates a long-lifetime fluorescence probe. Rotational diffusion can be estimated by the degree of polarization of the emitted light or followed dynamically in the time domain. The relationship between the anisotropy and rotational correlation times is given by69

| (10) |

where r0 is the so-called limiting anisotropy (measured in the absence of rotational diffusion), gj is the fractional amplitude of correlation time θj.

Analysis of samples that display complex rotational motions or multi-exponential lifetimes requires measurement at more than one frequency. Given that local motion of the fluorescent probe is always a factor, frequency domain measurements typically monitor the phase shifts and modulation amplitudes at many frequencies. Modern instrumentation, such as provided by ISS instruments (ISS, Inc., Champaign, IL) allow such rapid analysis.

V. Results

The change in phase of the anisotropy decay of Nanodiscs made with MSP1E3D1 and labeled with [Ru(2,2’-bipyridine)2(5-iodoacetamido-1,10-phenanthroline)](PF6)2, herein referred to as RuBPY, is shown in Figure 4. Initially, the lifetime of the sample is determined using a RuBPY reference (lifetime = 430 ns). The decay of labeled Nanodiscs fit best to two lifetimes, although all samples measured contain most of the fractional intensity in one of these decay times. Thus, we use the weighted average lifetime of each sample to fit anisotropy decays. Since modulation and phase provide independent measures of the anisotropy, we have chosen to fit only the phase due to its sensitivity. At high modulation frequencies (>1 MHz), most of the long-lifetime fluorophores have not decayed over the course of a single modulation cycle, leading to a low modulation ratio. This results in noise in the high frequency regime. Despite this, AD fits are achieved with goodness-of-fit parameters (χ2) of less than 2 in all cases using the fitting procedure described in the methods section.

Figure 4:

Delta phase component of the anisotropy decay of Nanodiscs made with MSP1E3D1 (red) along with a fit generated by fixing a single fast rotation to 5 ns and floating a slower rotation (blue line, see methods). The weighted average lifetime used to fit the data was 969 ns. Noise at high modulation frequencies (>1 MHz) results from the low modulation of the long-lifetime RuBPY label at these high modulation frequencies.

The anisotropy data are fit by fixing a fast rotation (θ1=5ns) to account for local motion of the fluorophore and fitting a slower rotation (θ2) to the data. The total anisotropy is fixed to 0.18, the anisotropy of the dye in the absence of rotational diffusion70. The average θ2 for Nanodiscs made using D1, E1, E2, and E3 MSP are 63.3±3 ns, 94.1±4 ns, 101±5 ns, and 121±9 ns. The fitting shows that fluorescence anisotropy is sensitive to small changes in overall rotational motion.

We have also plotted the average θ2 from these experiments against the harmonic mean relaxation time θh derived from both ellipsoid-based modeling (Figure 5A) and HYDROPRO calculations of all-atom Nanodisc PDBs (Figure 5B). In this context relaxation time and correlation time are used interchangeably and both refer to the exponential decay of a signal to 1/e of its initial value. The results show a linear relationship between the data and calculated values for both models (R2=0.958 and 0.937 for the ellipsoid model and HYDROPRO), indicating that theoretically predicted increases in rotational motion are borne out by experimental data. A comparison between experimental and calculated θs obtained for several proteins of various sizes has recently been given71. Intriguingly, this work demonstrates that there are some proteins for which none of the models used accurately predicts the experimentally determined correlation times. Additionally, these models were developed to address primarily soluble proteins which presumably display rigid-body motion over the time scales of interest. The overall rotation of Nanodiscs may be more significantly affected by internal mobility than globular proteins, and lipid-protein complexes have not traditionally been the subject of hydrodynamic analysis. Despite these discrepancies, the trend of increasing θ with Nanodisc size is preserved.

Figure 5:

Comparison of θs calculated using the ellipsoid model (A) and HYDROPRO (B) for Nanodiscs of varying size (MSPs used, in order from left to right: D1, E1, E2, E3). For the ellipsoid model, θh was calculated as the harmonic mean of the three characteristic decay times based on equations given in the text. HYDROPRO calculations were performed using the shell-based model and the recommended AER of 2.9 angstroms for atomic-level primary models.

VI. Discussion

We have demonstrated a method to measure and analyze the rotational dynamics of Nanodiscs in solution. The data show that increasing the diameter of the Nanodisc leads to an increase in the rotational correlation time, both experimentally and by calculation. Modeling the overall rotation using HYDROPRO provides a fast and effective way to computationally investigate these dynamics without time intensive molecular dynamics simulations.

The various modeling approaches discussed in this work may introduce artifacts that complicate the analysis. The bead radius used with HYDROPRO (2.9 Angstroms) reflects a globally optimized parameter that was fit using a dataset of soluble proteins whose rotational motions may differ significantly from that of lipid-protein complexes such as Nanodiscs. We must also consider the possibility that Nanodiscs do not display rigid body rotations in solution, which might result from bending or other movements of the MSP and bilayer that are not connected with the overall tumbling of the assembly. Previous simple hydrodynamic modeling has also failed to recover the experimentally measured correlation times for several proteins in solution71.

Water models associated with all-atom MD can be corrected to account for viscosity effects as demonstrated by Linke et. al63. However, in our experience, even coarse-grained MD simulations of empty Nanodiscs fail to reflect the measured overall rotational motions even after several microseconds. It would likely require much longer simulations, possibly on the order of 50–100 microseconds, to observe the slower rotation of these large complexes. It would take significantly longer to perform the equivalent all-atom simulations.

Fitting the anisotropy decays to account for complex rotational motions is highly subjective in the absence of further structural information. However, Nanodiscs are extremely well characterized and are known to form monodisperse particles of controlled size6,48. This knowledge allows confident assignment of a single fast rotation of 5 ns to account for local motion of the RuBPY fluorophore and a single slower rotation to capture the motion of the entire complex. While empty Nanodiscs are well approximated by oblate spheroids, fitting to more correlation times did not improve the quality of the fit. This is unsurprising given that 1) the fitting does not consider a priori structural information such as hydration volume and 2) the inherent difficulty in resolving closely spaced correlation times as demonstrated by Figure 2.

In contrast to previously reported correlation times in NMR, we have described rotational motions on the order of 60–120 ns. The most significant differences likely result from the different sizes of MSP and different temperatures used. The smallest MSP used here was MSP1D1 (note: 7XHis tags were removed prior to disc assembly in all cases). The truncated versions of this MSP used for NMR form particles of lower diameter, which thus reduces the rotational correlation time. The NMR experiments were also performed at higher temperatures to improve resolution for structural assignment. While all data measured here were taken at 20°C, fluorometry could easily be performed at higher temperatures. However, future studies directed toward investigating protein association with free Nanodiscs in solution must consider stability of the various complexes involved.

This assay can be extended to monitor the association of other proteins with Nanodiscs. As macromolecules bind to the Nanodisc surface, the rotational correlation time(s) measured experimentally are expected to increase, corresponding to a change in shape and size of the rotator. This suggests that a protein that protrudes farther from the membrane surface should slow the rotation more than a protein that lies closer to the surface. We have demonstrated the utility of single-frequency methods for measuring the affinity of Kras4b for Nanodiscs of varying lipid composition56. With the ability to quickly record many frequencies simultaneously using the digital frequency domain system described here, it becomes possible to obtain highly accurate and precise information on the changing rotational dynamics of Nanodisc-protein complexes.

In summary, we have presented an analysis of the rotational diffusion of Nanodiscs, and shown that with a suitable long lifetime probe, typically greater than 400 ns, one can monitor the diffusional motion of Nanodiscs. The use of modern multi-frequency phase and modulation methods provide the sensitivity and selectivity to observe differing rotational motions of Nanodiscs of varying size. Importantly, the label is attached to the Nanodisc assay platform and not an incorporated target, alleviating the need to genetically engineer or otherwise modify the structure of desired target proteins. We anticipate that such an approach will find great utility in quantitating the association of signaling molecules to a membrane surface as well as determining the topology of membrane proteins self-assembled into Nanodiscs.

VII. Methods.

Reagents.

1–2-sn-glycero-3-dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) was purchased from NOF America Corporation in powder form and reconstituted in chloroform. Lipid concentration was determined via phosphate analysis72.

MSP synthesis and purification.

MSPs were expressed and purified as described6. The following buffers were used: Buffer A (20mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl), Buffer B (Buffer A with an additional 50mM Na Cholate), Buffer C (Buffer A with an additional 50mM Imidazole). All buffers were brought to pH 7.3 before use. 7X-His tags were cleaved with Tobacco Etch Virus protease and purified via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography using Buffer C. Imidazole was removed via dialysis before labeling. MSPs were labeled with [Ru(2,2’-bipyridine)2(5-iodoacetamido-1,10-phenanthroline)](PF6)2 (referred to as RuBPY) as previously described70. Sulfhydryls were reduced with 4-fold molar excess of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine for at least 10 minutes while stirring followed by the addition of 10-fold molar excess RuBPY dissolved in dry dimethyl sulfoxide. This reaction continued for 4 hours at room temperature and was placed at 4°C and left stirring overnight. Labeled protein was purified via gel filtration on a G-25 column using the Buffer A. Concentrations and labeling efficiencies were calculated via spectrophotometry using a correction factor70.

Nanodisc preparation.

Nanodiscs were prepared based on the standard protocol6. Lipids were dried first under nitrogen and then under vacuum for at least 4 hours. Lipids were then reconstituted to 10mM in Buffer B. MSP and lipids were added to a 1.7mL tube in the optimal ratios described20, except for MSP1D1 for which a ratio of 95:1 lipids:MSP was used. Either equivalent volumes (MSP1D1, MSP1E2, MSP1E3) or 0.5g/mL (MSP1E1D1) of Amberlite XAD-2 were added to the reconstitution mixture. Reactions continued on an orbital shaker at room temperature for at least 4 hours. Nanodiscs were purified into Buffer A on a Superdex™−200 HPLC column. Peak fractions were kept and used for all fluorometry experiments.

Fluorometry.

The ISS K2 phase fluorometer equipped with a K50 digital frequency domain system was used for all measurements (ISS, Inc., Champaign, IL). All fluorescence lifetimes and anisotropies were recorded in Buffer A at 20°C. Each experiment involved selecting a fundamental frequency upon which 30 harmonics were generated. The duty cycle of the laser was varied to optimize the number of observed photon counts. Lifetimes were measured using a RuBPY reference dissolved in Buffer A (lifetime measured independently as 430 ns). For lifetime measurements, the fundamental frequency was set to 20kHz and measured in the frequency domain with the emission polarizer set to 54.7 degrees (magic angle) at which the signal is proportional to the total intensity. Anisotropy measurements were recorded in the frequency domain at two fundamental frequencies (50kHz and 100kHz) and merged together resulting in a single AD curve with 45 modulation frequencies for each replicate. Overlapping data points were averaged.

Data analysis was done using VINCI. Figures in the text were made with MATLAB. Modulation and phase (or only phase for anisotropy fitting) were fit to the model by least-squares analysis, and parameters were varied until the difference between data and model were minimized. Fitting equations are given by Lakowicz69. Lifetime experiments were fit to two decay times. Since in all cases most of the fractional intensity was attributed to one component, the weighted average lifetime was used to fit anisotropy decays. Anisotropies were fit by fitting two rotations, one of which was fixed at 5ns to account for local motions of the RuBPY fluorophore. The total anisotropy was fixed at 0.18, the limiting anisotropy of the dye in the absence of rotational diffusion70. Correlation times were determined by fitting only the phase (this is accomplished by setting the modulation error to 1 in VINCI).

Modeling rotational correlation times.

All modeling was performed using a temperature of 20°C and viscosity of water of 1 centipoise. The ellipsoid-based model was based on equations given in the text. Nanodiscs were approximated as ellipsoids with diameters given by their Stokes diameters determined via SEC20 and a height of 5 nm based on SAXS6. Correlation times were then computed directly from the equations based on the axial ratios of each Nanodisc. HYDROPRO calculations were performed on all-atom PDB files generated from Charmm-GUI73. The shell-based calculation for atomic-level primary models was used with an AER = 2.9 angstroms following guidelines presented in the HYDROPRO user guide. The partial specific volume was set to 0.702cm3/g.

Highlights.

Rotational correlation times of nanodiscs were accurately measured using fluorescence depolarization

Nanodiscs of increasing diameters display longer overall rotational correlation times

The long-lifetime dye, which is covalently attached to the Nanodiscs, allows sensitive, label-free detection of protein binding

Acknowledgement:

This work was supported by NIH via the MIRA program GM118145.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References.

- 1.Zhou H-X, Cross TA. Influences of Membrane Mimetic Environments on Membrane Protein Structures. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42(1):361–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs in Membrane Biochemistry and Biophysics. Chem Rev. 2017;117(6):4669–4713. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayburt TH, Sligar SG. Self-assembly of single integral membrane proteins into soluble nanoscale phospholipid bilayers. Protein Sci. 2003;12(11):2476–2481. doi: 10.1110/ps.03267503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald JH, Krul ES, Jonas A. Structure of apolipoprotein A-I in three homogeneous, reconstituted high density lipoprotein particles. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(32):20037–20043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson JW, Jonas A, Sligar SG. Imaging and manipulation of high-density lipoproteins. Biophys J. 1997;73(3):1184–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Lazarides AA, Sligar SG. Directed Self-Assembly of Monodisperse Phospholipid Bilayer Nanodiscs with Controlled Size. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(11):3477–3487. doi: 10.1021/ja0393574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viegas A, Viennet T, Etzkorn M. The power, pitfalls and potential of the nanodisc system for NMR-based studies. Biol Chem. 2016:ASAP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prade E, Mahajan M, Im SC, et al. A Minimal Functional Complex of Cytochrome P450 and FBD of Cytochrome P450 Reductase in Nanodiscs. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57(28):8458–8462. doi: 10.1002/anie.201802210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swainsbury DJK, Scheidelaar S, Foster N, van Grondelle R, Killian JA, Jones MR. The effectiveness of styrene-maleic acid (SMA) copolymers for solubilisation of integral membrane proteins from SMA-accessible and SMA-resistant membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta - Biomembr. 2017;1859(10):2133–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laursen T, Borch J, Knudsen C, et al. Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum. Science (80-). 2016;354(6314):890–893. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravula T, Hardin NZ, Ramamoorthy A. Polymer Nanodiscs: Advantages and Limitations. Chem Phys Lipids. 2019;219(January):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swainsbury DJK, Scheidelaar S, Van Grondelle R, Killian JA, Jones MR. Bacterial reaction centers purified with styrene maleic acid copolymer retain native membrane functional properties and display enhanced stability. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2014;53(44):11803–11807. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salnikov ES, Anantharamaiah GM, Bechinger B. Supramolecular Organization of Apolipoprotein-A-I-Derived Peptides within Disc-like Arrangements. Biophys J. 2018;115(3):467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagn F, Nasr ML, Wagner G. Assembly of phospholipid nanodiscs of controlled size for structural studies of membrane proteins by NMR. Nat Protoc. 2018;13(1):79–98. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchie TK, Grinkova YV., Bayburt TH, et al. Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins in Phospholipid Bilayer Nanodiscs In: Methods in Enzymology. Vol 464 1st ed. Elsevier Inc.; 2009:211–231. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)64011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baas BJ, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Homotropic cooperativity of monomeric cytochrome P450 3A4 in a nanoscale native bilayer environment. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;430(2):218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skar-Gislinge N, Kynde SAR, Denisov IG, et al. Small-angle scattering determination of the shape and localization of human cytochrome P450 embedded in a phospholipid nanodisc environment. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2015;71:2412–2421. doi: 10.1107/S1399004715018702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayburt TH, Sligar SG. Single-molecule height measurements on microsomal cytochrome P450 in nanometer-scale phospholipid bilayer disks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(10):6725–6730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062565599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuler MA, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs as a new tool to examine lipid-protein interactions. In: Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol 974; 2013:415–433. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-275-9_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritchie TK, Grinkova YV, Bayburt TH, et al. Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins in Phospholipid Bilayer Nanodiscs In: Methods in Enzymology. Vol 464 1st ed. Elsevier Inc.; 2009:211–231. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)64011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayburt TH, Leitz AJ, Xie G, Oprian DD, Sligar SG. Transducin activation by nanoscale lipid bilayers containing one and two rhodopsins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(20):14875–14881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Eps N, Caro LN, Morizumi T, et al. Conformational equilibria of light-activated rhodopsin in nanodiscs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(16):E3268–E3275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620405114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayburt TH, Vishnivetskiy SA, McLean MA, et al. Monomeric rhodopsin is sufficient for normal rhodopsin kinase (GRK1) phosphorylation and arrestin-1 binding. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(2):1420–1428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez FJD Orelle C, Davidson AL Functional reconstitution of an ABC transporter in Nanodiscs for use in electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(28):9513–9515. doi:DOI: 10.1021/ja104047c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orelle C, Durmort C, Mathieu K, et al. A multidrug ABC transporter with a taste for GTP. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2309. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20558-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Cytochromes P450 in nanodiscs. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics. 2010;1814(1):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye F, Hu G, Taylor D, et al. Recreation of the terminal events in physiological integrin activation. J Cell Biol. 2010;188(1):157–173. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagn F, Etzkorn M, Raschle T, Wagner G. Optimized phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs facilitate high-resolution structure determination of membrane proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(5):1919–1925. doi: 10.1021/ja310901f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Y, Cao E, Julius D, Cheng Y. TRPV1 structures in nanodiscs reveal mechanisms of ligand and lipid action. Nature. 2016;534(7607):347–351. doi: 10.1038/nature17964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatsogiannis C, Merino F, Prumbaum D, et al. Membrane insertion of a Tc toxin in near-atomic detail. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthies D, Bae C, Toombes GE, et al. Single-particle cryo-EM structure of a voltage-activated potassium channel in lipid nanodiscs. Elife. 2018;7. doi: 10.7554/eLife.37558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan CR, Hebling CM, Rand KD, Stafford DW, Jorgenson JW, Engen JR. Conformational transitions in the membrane scaffold protein of phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(9):M111 010876, 11 pp. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nasr ML, Shi X, Bowman AL, et al. Membrane phospholipid bilayer as a determinant of monoacylglycerol lipase kinetic profile and conformational repertoire. Protein Sci. 2013;22(6):774–787. doi: 10.1002/pro.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trahey M, Li MJ, Kwon H, Woodahl EL, McClary WD, Atkins WM. Applications of lipid nanodiscs for the study of membrane proteins by surface plasmon resonance. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2015;2015:29.13.1–29.13.16. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps2913s81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treuheit NA, Redhair M, Kwon H, et al. Membrane interactions, ligand-dependent dynamics, and stability of cytochrome P4503A4 in lipid Nanodiscs. Biochemistry. 2016;55(7):1058–1069. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li MJ, Guttman M, Atkins WM. Conformational dynamics of P-glycoprotein in lipid nanodiscs and detergent micelles reveal complex motions on a wide time scale. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(17):6297–6307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rouck JE, Krapf JE, Roy J, Huff HC, Das A. Recent advances in nanodisc technology for membrane protein studies (2012–2017). FEBS Lett. 2017;591(14):2057–2088. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilcox KC, Marunde MR, Das A, et al. Nanoscale synaptic membrane mimetic allows unbiased high throughput screen that targets binding sites for Alzheimer’s-associated Abeta oligomers. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw AW, Pureza VS, Sligar SG, Morrissey JH. The local phospholipid environment modulates the activation of blood clotting. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6556–6563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLean MA, Gregory MC, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs: A Controlled Bilayer Surface for the Study of Membrane Proteins. Annu Rev Biophys. 2018;47:107–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shih AY, Denisov IG, Phillips JC, Sligar SG, Schulten K. Molecular dynamics simulations of discoidal bilayers assembled from truncated human lipoproteins. Biophys J. 2005;88(1):548–556. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skar-Gislinge N, Simonsen JB, Mortensen K, et al. Elliptical structure of phospholipid bilayer Nanodiscs encapsulated by scaffold proteins: Casting the roles of the lipids and the protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(39):13713–13722. doi: 10.1021/ja1030613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skar-Gislinge N, Johansen NT, Hoiberg-Nielsen R, Arleth L. Comprehensive Study of the Self-Assembly of Phospholipid Nanodiscs: What Determines Their Shape and Stoichiometry? Langmuir. 2018;34(42):12569–12582. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b01503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tark S-H, Das A, Sligar S, Dravid VP. Nanomechanical detection of cholera toxin using microcantilevers functionalized with ganglioside nanodiscs. Nanotechnology. 2010;21(43):435502/1–435502/7. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/43/435502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sloan CD, Marty MT, Sligar SG, Bailey RC. Interfacing lipid bilayer nanodiscs and silicon photonic sensor arrays for multiplexed protein-lipid and protein-membrane protein interaction screening. Anal Chem. 2013;85(5):2970–2976. doi: 10.1021/ac3037359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wade JH, Bailey RC. Applications of optical microcavity resonators in analytical chemistry. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2016;9(1):1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-071015-041742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw AW, Pureza VS, Sligar SG, Morrissey JH. The local phospholipid environment modulates the activation of blood clotting. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6556–6563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bayburt TH, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Self-Assembly of Discoidal Phospholipid Bilayer Nanoparticles with Membrane Scaffold Proteins. Nano Lett. 2002;2(8):853–856. doi: 10.1021/nl025623k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye X, McLean MA, Sligar SG. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate Modulates the Affinity of Talin-1 for Phospholipid Bilayers and Activates Its Autoinhibited Form. Biochemistry. 2016;55(36):5038–5048. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye X, McLean MA, Sligar SG. Conformational equilibrium of talin is regulated by anionic lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1858(8):1833–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kucharska I, Edrington TC, Liang B, Tamm LK. Optimizing nanodiscs and bicelles for solution NMR studies of two β-barrel membrane proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2015;61(3–4):261–274. doi: 10.1007/s10858-015-9905-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dutta SK, Yao Y, Marassi FM. Structural insights into the yersinia pestis outer membrane protein ail in lipid bilayers. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121(32):7561–7570. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b03941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sušac L, Horst R, Wüthrich K. Solution-NMR characterization of outer-membrane protein A from E. coli in lipid bilayer nanodiscs and detergent micelles. ChemBioChem. 2014;15(7):995–1000. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y, Kijac AZ, Sligar SG, Rienstra CM. Structural analysis of nanoscale self-assembled discoidal lipid bilayers by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2006;91(10):3819–3828. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shenkarev ZO, Lyukmanova EN, Solozhenkin OI, et al. Lipid-protein nanodiscs: possible application in high-resolution NMR investigations of membrane proteins and membrane-active peptides. Biochem Biokhimiia. 2009;74(7):756–765. doi: 10.1134/S0006297909070086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gregory MC, McLean MA, Sligar SG. Interaction of KRas4b with anionic membranes: A special role for PIP2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;487(2):351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jonas A Studies on the Structure of Bovine Serum High Density Lipoproteiu Using Covalently Bound Fluorescent Probes*. J Biol Chem. 1972;247(23):7773–7778. http://www.jbc.org/content/247/23/7773.full.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Favro LD. Theory of the Rotational Brownian Motion of a Free Rigid Body. Phys Rev. 1960;119(1):53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ortega A, García de la Torre J. Hydrodynamic properties of rodlike and disklike particles in dilute solution. J Chem Phys. 2003;119(18):9914–9919. doi: 10.1063/1.1615967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tao T Time-dependent fluorescence depolarization and Brownian rotational diffusion coefficients of macromolecules. Biopolymers. 1969;8(5):609–632. doi: 10.1002/bip.1969.360080505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ortega A, Amorós D, García De La Torre J. Prediction of hydrodynamic and other solution properties of rigid proteins from atomic- and residue-level models. Biophys J. 2011;101(4):892–898. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen PC, Hologne M, Walker O. Computing the Rotational Diffusion of Biomolecules via Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Quaternion Orientations. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121(8):1812–1823. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b11703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Linke M, Köfinger J, Hummer G. Fully Anisotropic Rotational Diffusion Tensor from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122(21):5630–5639. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b11988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ye X, McLean MA, Sligar SG. Conformational equilibrium of talin is regulated by anionic lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta - Biomembr. 2016;1858(8):1833–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spencer RD, Weber G. Influence of brownian rotations and energy transfer upon the measurements of fluorescence lifetime. J Chem Phys. 1970;52(4):1654–1663. doi: 10.1063/1.1673201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jameson DM. Introduction to Fluorescence. Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3rd ed. Springer-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lakowicz JR. Frequency-Domain Lifetime Measurements In: Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3rd ed.; 2006:157–204. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-0-387-46312-4_5.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lakowicz JR. Time-Dependent Anisotropy Decays. In: Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy.; 2006:383. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46312-4_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castellano FN, Dattelbaum JD, Lakowicz JR. Long-Lifetime Ru(II) Complexes as Labeling Reagents for Sulfhydryl Groups. Anal Biochem. 1998;255:165–170. https://ac.elscdn.com/S0003269797924684/1-s2.0-S0003269797924684-main.pdf?_tid=ff725b9fd434-43b5-951bbc5f71effc83&acdnat=1540927791_b980b8ee6d6b130a1907694aa42730f4. Accessed October 30, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zuk PJ, Cichocki B, Szymczak P. GRPY: An Accurate Bead Method for Calculation of Hydrodynamic Properties of Rigid Biomacromolecules. Biophys J. 2018;115(5):782–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen PS, Toribara TY, Warner H. Microdetermination of phosphorus. Anal Chem. 1956;28(11):1756–1758. https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines. Accessed October 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-Based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2008;29(11):1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]