Abstract

Women experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) are at an increased risk of engaging in sexual risk behaviors and experiencing depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Adverse childhood events (ACEs) can put women at increased risk for poor sexual and mental health. Women experiencing IPV report ACEs, but, few studies have examined the heterogeneity in women’s experiences of ACEs and its effects on sexual and mental health. Therefore, the current study used latent profile analysis to identify profiles of ACEs (i.e., witnessing maternal and paternal IPV victimization; childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; and physical and emotional neglect), and their association with sexual risk behaviors, and depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Women experiencing IPV aged 18–58 years (N=212) were recruited from community establishments and completed face-to-face, computer-assisted interviews. Three profiles were identified: Low Adverse Childhood Events class (n = 115); Moderate Adverse Childhood Events class (n = 62); and High Adverse Childhood Events class (n = 35). Path analyses revealed that profiles of ACEs directly predicted women’s IPV victimization severity, depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Secondary and tertiary mental health interventions may be more effective if the heterogeneity in women’s adverse childhood events are addressed by integrating intervention strategies specific to these adverse childhood event subgroups.

Keywords: Intimate Partner Violence, Adverse childhood events, Latent Profile Analysis, Sexual Risk, Mental Health

Background

Adverse childhood events (ACEs) are preventable public health issues with a significant impact on health problems and behaviors later in life, such as sexual risk, depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms, and intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization. ACEs are stressful and/or traumatic events, which include childhood maltreatment—physical, sexual, emotional abuse and neglect, and witnessing parental IPV (SAMHSA, 2017). In the United States, one in four children (25.6%) are estimated to experience childhood maltreatment and nearly one in five children (17.3%) witness parental IPV in their lifetime (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2013).

There is strong evidence suggesting that ACEs are risk factors for poor sexual and mental health among women. In the context of sexual health, women who experienced ACEs are more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors such as condomless sex (Senn & Carey, 2010), multiple sexual partners, and early age at sexual debut (Hillis, Anda, Felitti, & Marchbanks, 2001). In addition, ACEs are associated with mental health problems such as depression (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2014) and posttraumatic stress disorder (Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, 2008). Previous research suggest that ACEs can negatively impact women’s psychological and behavioral development (Senn & Carey, 2010), which may result in poor sexual health (Brady & Donenberg, 2006; Senn & Carey, 2010; Wilson & Widom, 2011; Wyatt et al., 2002), and mental health (Campbell, Greeson, Bybee, & Raja, 2008; Holt et al., 2008; Singer, Anglin, yu Song, & Lunghofer, 1995). For example, women may use substances to cope with their experiences, which can impair sexual decision-making (Senn, Carey, Vanable, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2006). Also, ACEs may hinder critical brain functions that regulate mood, emotional, and fear responses, which can increase the risk of poor mental health such as depressed affect and anxiety (Anda et al., 2006).

In addition to women’s sexual and mental health, research suggests a complex relationship between ACEs and IPV victimization (Carlson, McNutt, & Choi, 2003; Gover, Kaukinen, & Fox, 2008; Widom, Czaja, & Dutton, 2014). A number of studies found that women who experience child abuse are at increased risk of victimization in adulthood (Gover et al., 2008; Widom et al., 2014). One study found that women who endorse childhood physical abuse or witnessing parental IPV were at a six-fold increase for experiencing physical IPV, but women who only endorsed childhood sexual abuse were not at increased risk for physical IPV (Bensley, Van Eenwyk, & Wynkoop Simmons, 2003). Similarly, Gover et al. (2008) found that women who witnessed their father’s use of physical violence against their mothers were 72% more likely to experience physical IPV than women who did not witness such maternal victimization. Several explanations exist for these associations. The intergenerational transmission of IPV model suggests that IPV is passed from one generation to the next such that children who are abused and/or witnessed parental IPV are more likely to use and experience violence in later relationships (Egeland, 1993). The intergenerational transmission model is supported by the social learning theory (Bandura & McClelland, 1977) whereby the use of violence and victimization are learned experiences. Alternatively, attachment theory suggests that children exposed to parental IPV can develop internal working models based on these violent experiences, which they use to guide future behaviors in close relationships (Holt et al., 2008). In contrast, some studies on poly-victimization suggest that vulnerabilities and risk factors that place a person at risk for one form of violence will likely increase their risk of revictimization by another form of violence (Hamby & Grych, 2013; Murphy, Elklit, & Shevlin, 2017; Willie, Powell, Lewis, Callands, & Kershaw, 2017). Multiple theoretical explanations can be used to clarify associations between ACEs and IPV victimization among women, yet there remains a dearth of studies that have investigated the impact of ACEs on the health and behaviors of women experiencing IPV.

Better understanding of the impact of ACEs on the health and behavior of women experiencing IPV is warranted. IPV is a common experience in the United States, as one in three women (35.6%) have experienced IPV in their lifetime (Black et al., 2011). Women experiencing IPV are at increased risk for suboptimal sexual and mental health as this population is four times more likely to contract HIV/STIs (Gielen et al., 2007) and depression and posttraumatic stress disorder are highly prevalent mental health consequences of IPV (Campbell, 2002; Logan, Walker, Jordan, & Leukefeld, 2006). In addition, women who experience IPV often report experiencing multiple ACEs (Gobin, Iverson, Mitchell, Vaughn, & Resick, 2013) and some emerging evidence suggests that ACEs could moderate the efficacy of mental health interventions designed for women experiencing IPV (Zlotnick, Capezza, & Parker, 2011). Collectively, these findings illustrate that women experiencing IPV may be more vulnerable to poor sexual and mental health due to the unique contributions of both ACEs and IPV victimization.

ACEs may have significant health and behavioral implications for women experiencing IPV, but statistical approaches to understand and explore the diversity and patterning of ACEs has been limited. Variable-oriented approaches that generally compare the means of specific variables, such as linear regression, operate as if there is no variation in ACEs experienced by women. Conversely, person-oriented approaches (e.g., latent profile analysis) focus on identifying distinct homogenous subgroups, which could take into account the variation of ACEs. Latent profile analysis is a useful analytic tool for women experiencing IPV because the type and severity of ACEs may differentially impact women’s sexual and mental health (Briere, Kaltman, & Green, 2008; Hahm, Lee, Ozonoff, & Van Wert, 2010) and IPV victimization severity (Heyman & Slep, 2002; Israel & Stover, 2009; Whitfield, Anda, Dube, & Felitti, 2003; Widom et al., 2014). Latent profile analysis can use the type, severity, and co-occurrence of ACEs to uncover distinct profiles of women with shared experiences. These profiles can then be used to identify women at greatest risk for sexual risk behaviors, depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms, and the most severe IPV victimization. Latent profile analysis may provide a unique opportunity to better inform the development of sexual and mental health interventions for women experiencing IPV that are tailored to ACEs.

Thus, the current study aimed to identify profiles of women experiencing IPV based on their ACEs, and examine associations between profile membership and women’s sexual and mental health, and IPV victimization severity. We used latent profile analyses to identify profiles of women based on the severity of ACEs (i.e., witnessing maternal and/or paternal IPV victimization, physical, sexual, and emotional childhood abuse, and physical and emotional childhood neglect). Next, we examined the effects of latent profile membership on sexual risk behaviors, depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms, and IPV victimization severity.

Methods

Procedure

Women experiencing IPV were recruited to participate in a larger study exploring the prevalence and associations of substance use and IPV-related posttraumatic stress symptoms among women experiencing IPV. Participants were recruited throughout communities in the northeast region of the United States. Flyers were posted throughout the community in various establishments such as salons, grocery stores, laundromats, and health clinics. After responding to the flyers, women were screened for eligibility via the phone. The eligibility rate of those screened was 32.9% and the participation rate among those screened as eligible was 73%.

Women provided written informed consent and completed a face-to-face, computer-assisted interview administered by trained female research associates. Women were remunerated $50 for their participation and provided with a list of community resources. The Yale University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Participants

Women were eligible based on the following criteria: they reported experiencing physical IPV with a male partner in the past six months; face to face contact with their male partner at least twice a week; less than 2 weeks apart from their male partner in the last month; English speaking; and a household income of less than or equal to $4,200 per month. The income criterion was established a priori to control for the association between socioeconomic status and differential access to resources because higher income and/or higher socioeconomic status has been associated with greater access to and utilization of services, which can have an impact on mental health symptoms.

The sample was composed of 67% Black or African American, 20% White, and 13% another racial group, or bi or multi-racial women. The age range was from 18 to 58 years (M = 36.63, SD = 10.44). Almost two in three women (65%) were unemployed and 35% were employed either part-time or full-time. The average annual household income was $13,242 (SD = $10,405). The average level of education was 12.08 years (SD = 1.56). More than half of the women in the sample (57%) were living with their partner.

Measures

Latent profile indicators for ACEs were: witnessing (1) maternal paternal IPV victimization, (2) paternal IPV victimization; childhood (3) physical, (4) sexual, and (5) emotional abuse; childhood (6) physical and (7) emotional neglect. These constructs were measured as follows:

Witnessing maternal and paternal IPV victimization was measured using 24 items that assessed whether a participant witnessed physical aggression between caregivers (e.g., aggression against her maternal caregiver by her paternal caregiver; and aggression against her paternal caregiver by her maternal caregiver). An example item is “When I was growing up, I saw or heard my father (figure) hit my mother (figure).” These items were based on the childhood violence questions from the revised Conflict Tactics Scale Parent-Child version (Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003). The item responses were rated on a 5-point scale of 0=never true to 4=very often true. The validity of this scale is well-established with American parents and correlates with other measures of maltreatment such as corporal punishment and physical abuse (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). The Cronbach’s α = 0.99 (witnessing maternal IPV victimization) and α = 0.99 (witnessing paternal IPV victimization).

Child abuse and neglect was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein & Fink, 1998). The CTQ is a 28-item measure composed of five subscales that measure childhood physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and childhood physical and emotional neglect. An example item is “People in my family hit and left me with bruises or marks.” Responses were rated on a 5-point scale from 0=never true to 4=very often true. The Cronbach’s α = 0.85 (physical abuse), α = 0.96 (sexual abuse), α = 0.86 (emotional abuse), α = 0.74 (physical neglect), and α = 0.88 (emotional neglect). Validity of this measure has been established and is aligned well with therapist’s ratings (Bernstein et al., 2003).

Outcomes were: 1) sexual risk behaviors, 2) depressive symptoms, and 3) posttraumatic stress symptoms, 4) physical IPV victimization severity, 5) psychological IPV victimization severity, and 6) sexual IPV victimization severity. These constructs were measured as follows:

Sexual risk behaviors were assessed over the past six months with an index created from a modified scale focused on the sexual health of women (Sikkema, Hansen, Meade, Kochman, & Fox, 2009). Engagement in sexual risk behaviors included: (1) any unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a primary partner living with HIV; (2) any unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a primary partner with a history of intravenous drug use; (3) any unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a primary partner with multiple sexual partners; (4) any unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a causal partner living with HIV; and (5) engaging in transactional sex work. An example item is “Have you engaged in sexual intercourse in exchange for food, shelter, or drugs?” An index score for sexual risk behaviors was calculated by summing responses from the five indicators. Validity of this measure was established in Sikkema et al., 2009.

Depressive symptoms were assessed over the past six months with The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses the severity of depressive symptoms in the past six months. An example item is “I felt that people disliked me.” A total score for depressive symptoms was calculated by summing responses rated from: 0=rarely or none of the time to 3=most or all of the time. This scale has established validity and has been used to discriminate between psychiatric patients and the general population (Radloff, 1977). The Cronbach’s α = 0.90.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed over the past six months with the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS) (Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997). The PDS is a self-report measure that assesses the severity of DSM IV posttraumatic stress symptoms in the past six months; IPV was the referent traumatic event. An example item is “I had bad dreams or nightmares about the abusive events with my partner.” A total score for posttraumatic stress symptom severity was calculated by summing responses for the 17 symptoms rated from: 0=not at all or only one time to 3=five or more times a week/almost always. This scale has established validity and has demonstrated high diagnostic agreement with the SCID and strong correlation with other measures of psychopathology (Foa et al., 1997). The Cronbach’s α = 0.88.

Physical IPV victimization severity was measured in the past six months using the physical assault subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS-2) (Straus et al., 2003). The CTS-2 physical assault subscale assesses minor and severe forms of physical victimization with 12 items. An example item is “My partner threw something at me that could hurt.” Responses were recoded according to Straus et al. (2003) (i.e., 3–5 times =4; 6–10 times= 8; 10–20 times= 15; > 20 times= 25). Responses were summed to create a total score. This scale has been used in diverse settings and has shown good internal consistency and validity (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). The Cronbach’s α = 0.90.

Psychological IPV victimization severity was measured in the past six months using the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI) (Tolman, 1999). The PMWI is a 48-item measure that assesses the severity of psychological maltreatment. An example item is “My partner insulted me or shamed me in front of others.” Responses were rated on a 5-point scale: 1=never to 5=very frequently. Responses were summed to create a total score. This scale has demonstrated good internal consistency and validity with samples of women from diverse racial backgrounds (Tolman, 1999). The Cronbach’s α = 0.96.

Sexual IPV victimization severity was measured in the past six months using the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) (Koss & Oros, 1982). The SES is a 10-item measure that assesses unwanted sexual experiences. An example item is “Has your partner tried to make you have sex by using force, like slapping or pushing, or by threatening to use force?” The response options from the CTS-2 physical subscales were used and also recoded according to Straus et al. (2003) (i.e., 3–5 times =4; 6–10 times= 8; 10–20 times= 15; > 20 times= 25). Responses were summed to create a total score. This widely used scale has established validity with several different populations of college students (Koss & Oros, 1982). The Cronbach’s α = 0.88.

All participants reported their age, race, ethnicity, education, employment, income, relationship length, and relationship status.

Data Analysis

Latent profile analysis was used to investigate profiles of ACEs among women experiencing IPV. Latent profile analysis is a statistical method that uses continuous variables to classify homogenous subgroups (McCutcheon, 1987). There were seven indicator variables of ACEs (i.e., witnessing maternal and paternal IPV victimization, childhood physical, sexual, emotional abuse; childhood physical and emotional neglect). Women with similar responses to the seven indicators of ACEs were assigned to the same latent profile. To determine the best number of latent profiles, we chose the model with optimal goodness of fit measures. The best-fitted model consisted of: the lowest values for an Akaike Information Criterion and adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria and entropy greater than or equal to .80 (McCutcheon, 1987). In addition, a p value of < .05 on the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test indicated that, compared to the model with one less profile, the present model was a better fit (Celeux & Soromenho, 1996). About 20% of the data on witnessing maternal and paternal IPV victimization were missing for participants who indicated that their caregiver was not involved in an intimate relationship. Thus, full information maximum likelihood was used to estimate the latent profiles for participants with missing data for witnessing IPV between caregivers.

Summary statistics (means, frequencies) were calculated to describe participant characteristics for the overall sample and for each latent profile. ANOVAs were conducted to examine group differences in latent profile indicators and socio-demographics that were scored on a continuous scale. Chi-square tests were used to examine difference in socio-demographics scored on a binary scale.

Linear regression analyses using structural equation modelling software to model multiple outcomes at once were performed to investigate whether latent profile membership was directly related to physical, sexual, and psychological IPV victimization severity, sexual risk behaviors, depressive and posttraumatic stress symptom severity. The model controlled for covariates such as age, race, ethnicity, income, and education on the independent and dependent variables. Covariates were chosen if: they were significantly different between the latent classes (p < .05) or considered correlates of IPV (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012) and known social determinants of health (Healthy People 2020). Latent profile membership was exported from Mplus, treated as a categorical variable (i.e., dummy coded) in the analyses. The model was evaluated for goodness of fit with a CFI and TLI> .95, RMSEA < .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Summary statistics and ANOVAs were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, 1990). Latent class and regression analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012).

Results

Fit statistics indicate that the three-profile model was the optimal solution (Table 1). Akaike information criterion and adjusted Bayesian information criterion were small for the three-profile model and the Bootstrapped likelihood ratio suggest that the three-profile model was better than the two-profile model. The entropy is a measure of classification certainty, and the entropy for the three-profile model suggests a clear separation of the profiles. The Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test p-value of 0.18 for the four-profile model indicated that there was no significant improvements made to the overall fit when a fourth class was included. This fit statistic value provides evidence that the three-profile model is a better fit. Also, the four-profile model had a profile with less than 25 persons, which could have reduced the statistical power and may not have been a meaningful group. Finally, the three-profile model illustrated distinct and meaningful profiles, namely, low, moderate, and high adverse childhood events.

Table 1.

Fit Statistics for Latent Profiles (N=212)

| 1 Profile | 2 Profiles | 3 Profiles | 4 Profiles | 5 Profiles | |

| AIC | 8854.85 | 8484.74 | 8373.28 | 8310.42 | 8224.91 |

| BIC | 8901.84 | 8558.58 | 8473.98 | 8437.97 | 8379.31 |

| Adjusted BIC | 8857.48 | 8488.88 | 8378.92 | 8317.56 | 8233.56 |

| Entropy | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.93 |

| LMR LRT p-value | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.42 | |

| BLRT p-value | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Profile prevalence | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Profile 1 | 212 (100.0) | 145 (68.4) | 115 (54.2) | 36 (16.9) | 24 (11.3) |

| Profile 2 | 67 (31.6) | 35 (16.5) | 119 (56.1) | 42 (19.8) | |

| Profile 3 | 62 (29.2) | 11 (5.1) | 97 (45.8) | ||

| Profile 4 | 46 (21.7) | 34 (16.0) | |||

| Profile 5 | 15 (7.1) |

Note: AIC = Akaike’s information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; Adjusted BIC = sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion; LMR LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test p value for (K—1) profiles; BLRT = Bootstrapped Likelihood ratio test p value.

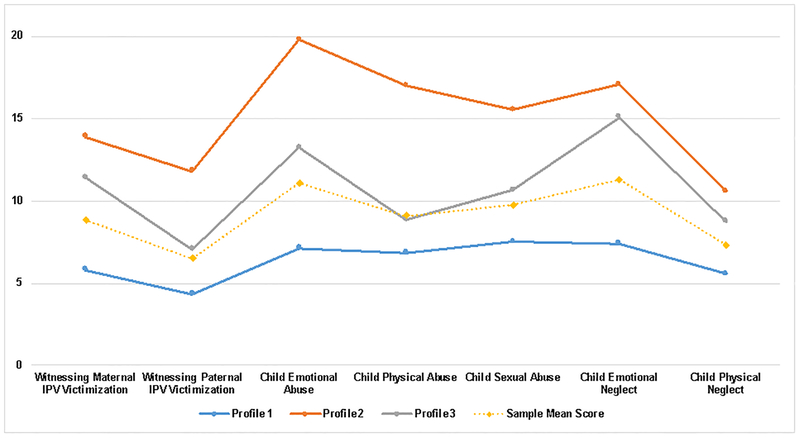

The Low Adverse Childhood Events profile was the largest profile and accounted for 54% of the sample; It was composed of women with lower levels of ACEs (Figure 1) (i.e.,ACEs lower than the mean of the total sample). The Moderate Adverse Childhood Events profile accounted for 29% of the sample; It was composed of women who reported moderate levels of ACEs (i.e., levels were higher than the mean of the total sample, but not the highest scores across all profiles). The High Adverse Childhood Events profile accounted for 17% of the sample; It was composed of women who reported the highest levels of all forms of ACEs (i.e., levels were higher than the mean of the total sample, and highest across all profiles). The mean scores for the ACEs profile indicators were statistically different across the profiles (Table 2). There were no significant differences in socio-demographics between the three latent profiles (Table 3). There were some significant differences in sexual and mental health, and IPV victimization severity across the profiles (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Profiles of adverse childhood events among women experiencing IPV (N=212). IPV = Intimate partner violence.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Differences in Latent Profile Indicators

| Latent Profile Indicators | Total Sample | Low Adverse Childhood Events | Moderate Adverse Childhood Events | High Adverse Childhood Events | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Witnessing Maternal IPV Victimization | 8.82 (12.61) | 5.79 (1.25)a | 11.4 (2.80)b | 13.87 (3.95)bc | 5.75 | .003 |

| Witnessing Paternal IPV Victimization | 6.48 (9.95) | 4.32 (1.05)a | 7.05 (1.79)ab | 11.80 (2.93)bc | 6.57 | .001 |

| Child Emotional Abuse | 11.05 (5.41) | 7.14 (0.26)a | 13.23 (0.79)b | 19.78 (0.99)c | 355.68 | < .001 |

| Child Physical Abuse | 9.07 (4.64) | 6.85 (0.24)a | 8.86 (0.71)b | 16.99 (1.44)c | 163.63 | < .001 |

| Child Sexual Abuse | 9.75 (6.89) | 7.51 (0.50)a | 10.66 (1.37)b | 15.52 (1.67)c | 21.97 | < .001 |

| Child Emotional Neglect | 11.27 (5.32) | 7.41 (0.35)a | 15.08 (0.74)b | 17.07 (0.93)c | 202.96 | < .001 |

| Child Physical Neglect | 7.31 (3.24) | 5.55 (0.13)a | 8.73 (0.84)b | 10.56 (1.05)c | 65.75 | < .001 |

Note. Means (standard deviations) are shown. Means that do not share subscripts differ by p < .05. p-values derived from Tukey’s test.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics by latent profile membership

| Total Sample | Low Adverse Childhood Events | Moderate Adverse Childhood Events | High Adverse Childhood Events | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 100 (212) | 54 (115) | 29 (62) | 17 (35) | |

| Age, M (SD), y | 36.63 (10.44) | 37.44 (10.91) | 34.37 (10.20) | 37.97 (8.83) | .08 |

| Annual Household Income, M, (SD) | 13,242 (10,405) | 13,476 (10,606) | 13,849 (11,755) | 11,394 (6,516) | .99 |

| Race | .21 | ||||

| Black or African-American | 67 (142) | 72 (83) | 65 (40) | 54 (19) | |

| White | 20 (43) | 16 (18) | 26 (16) | 26 (9) | |

| Other | 13 (27) | 12 (14) | 10 (6) | 20 (7) | |

| Hispanic or Latina | 8 (18) | 7 (8) | 10 (6) | 11 (4) | .65 |

| Employment | .12 | ||||

| Unemployed | 65 (138) | 62 (71) | 63 (39) | 80 (28) | |

| Part-Time or Full-Time | 35 (74) | 38 (44) | 37 (23) | 20 (7) | |

| Education, M, (SD), y | 12.08 (1.56) | 12.09 (1.31) | 12.41 (1.90) | 12.11 (1.82) | .91 |

| Relationship Length, M, (SD), y | 6.47 (6.37) | 6.92 (6.90) | 5.61 (5.40) | 6.52 (6.13) | .19 |

| Relationship Status | .94 | ||||

| Living Together | 57 (120) | 57 (66) | 57 (35) | 54 (19) | |

| Living Apart | 43 (92) | 43 (49) | 44 (27) | 46 (16) | |

| HIV-positive | 9 (19) | 9 (10) | 11 (7) | 6 (2) | .65 |

Note. Data are %(N) unless otherwise indicated; y: years; M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation

Table 4.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Differences in Outcomes

| Outcomes | Total Sample | Low Adverse Childhood Events | Moderate Adverse Childhood Events | High Adverse Childhood Events | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological IPV | 127.29 (34.83) | 122.02 (31.78) | 132.19 (37.94) | 135.94 (36.68) | 3.07 | .05 |

| Physical IPV | 34.99 (47.03) | 28.28 (38.21)a | 37.32 (52.47)b | 52.91 (58.30)bc | 3.89 | .02 |

| Sexual IPV | 10.45 (27.07) | 5.76 (15.27)a | 10.51 (24.75)b | 25.74 (48.51)ac | 7.77 | < .001 |

| Sexual Risk | 0.23 (0.55) | 0.16 (0.43)a | 0.27 (0.63)b | 0.43 (0.70)bc | 3.56 | .03 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 24.89 (12.02) | 22.20 (11.98)a | 25.75 (10.47)b | 32.22 (11.69)ac | 10.42 | < .001 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms | 19.09 (11.78) | 15.80 (11.46)a | 21.03 (11.23)b | 26.43 (9.78)bc | 13.53 | < .001 |

Note. Means (standard deviations) are shown. Means that do not share subscripts differ by p < .05. p-values derived from Tukey’s test.

Regression Model Fit and Results

Table 5 displays the final regression model. The overall model was just-identified and therefore, fit indices were not estimated. This model accounted for 3.7% of the variance in physical, 8.9% in sexual, and 6.2% in psychological IPV victimization severity; 4.5% in sexual risk, 11.5% in depressive symptoms, and 12.8% in posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Table 5.

Effects of Latent Profiles on IPV Victimization Severity, Sexual Risk, and Depressive and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

| Psychological IPV | Physical IPV | Sexual IPV | Sexual Risk | Depressive Symptoms | Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| High Adverse Childhood Eventsa | .14 | .20 | .28 | .20 | .29 | .33 |

| p | .04 | .01 | < .001 | .01 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Moderate Adverse Childhood Eventsa | .15 | .09 | .09 | .09 | .13 | .21 |

| p | .04 | .22 | .13 | .19 | .04 | < .001 |

Note. IPV = Intimate partner violence. Estimates are standardized.

Compared to the referent class (Low Adverse Childhood Events)

There were nine significant path estimates of latent profile membership on women’s sexual and mental health, and IPV victimization severity (Table 4). Women in the High Adverse Childhood Events profile reported more sexual risk behaviors (p =.01), and a greater severity of depressive (p < .001) and posttraumatic stress symptom severity (p < .001), and physical (p =.01), sexual (p < .001), and psychological IPV victimization severity (p =.04) than women in the Low Adverse Childhood Events profile. Women in the Moderate Adverse Childhood Events class reported greater severity of depressive (p =.04) and posttraumatic stress symptom (p < .001), and psychological IPV victimization severity (p =.04) than women in the Low Adverse Childhood Events profile.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to identify profiles of ACEs among women experiencing IPV, and examine associations of these profiles to sexual and mental health, and IPV victimization severity. A three-profile model adequately describes profiles of ACEs for women experiencing IPV: a low ACEs profile, a moderate ACEs profile, and a high ACEs profile. The Low ACEs profile was comprised of women experiencing IPV who reported lower average scores on witnessing maternal and paternal IPV victimization; childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; and physical and emotional neglect than the total sample. The Moderate ACEs profile was comprised of women experiencing IPV who reported higher average scores on witnessing maternal and paternal IPV victimization; childhood sexual and emotional abuse; and physical and emotional neglect than the total sample and the low ACEs profile. The High ACEs profile was comprised of women experiencing IPV who reported the highest average scores on witnessing maternal and paternal IPV victimization; childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; and physical and emotional neglect than the total sample, and the two other profiles. The diversity of ACEs among women experiencing IPV supports previous research suggesting that this population often reports multiple forms of childhood victimization (Bensley et al., 2003; Gobin et al., 2013). Further, findings have important implications for women’s sexual and mental health. In particular, women in profiles with higher severities of ACEs had poorer sexual and mental health, and greater IPV victimization severity. These findings suggest that profiles of women experiencing IPV with the highest severities of ACEs may benefit from targeted sexual and mental health interventions.

Our findings suggest potential dose-response relationships between victimization and women’s sexual and mental health. In particular, women in the two profiles characterized by ACEs levels higher than the overall sample tended to experience more mental health symptoms. Moreover, women who experienced higher severities of IPV victimization had more depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms. These findings are consistent with research demonstrating a significant relationship between ACEs and mental health (Holt et al., 2008) and between IPV victimization severity and mental health symptoms (Clemmons, Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, 2007). Experiences of childhood and IPV victimization can impair emotion regulation skills and difficulties with stress management (Lilly, London, & Bridgett, 2014). Thus, it is possible that experiencing moderate and high severities of ACEs created challenges for women when managing their emotions and stress, which later were manifested as and/or exacerbated mental health symptoms. Also, some research found that ACEs can be associated with decreased protective factors such as self-esteem and family support (Hobfoll, 2014; Hooven, Nurius, Logan-Greene, & Thompson, 2012). Women in the profiles with moderate and high severities of ACEs may have had little access to family support and low self-esteem, which also could contribute to poor adult mental health. ACEs are relevant experiences for women in adulthood, and both childhood and IPV victimization contribute to the maintenance and/or exacerbation of depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Our findings indicate that women in the profiles characterized with moderate and high severities of ACEs tended to also report a greater severity of IPV victimization. Our findings are consistent with a number of studies suggesting that the dose of ACEs directly relates to the severity of victimization in relationships (Heyman & Slep, 2002; Israel & Stover, 2009; Whitfield et al., 2003). The relationship between childhood and IPV victimization is very complex and additional research is needed to better understand this relationship and potential mechanisms among women experiencing IPV.

Also, our findings suggest that women who experienced the highest severity of ACEs tended to report more sexual risk behaviors. Experiencing multiple forms of child abuse can shape women’s view of their sexual self and make it difficult for them to feel comfortable expressing their sexual preferences (Seehuus, Clifton, & Rellini, 2015), especially if they are concerned about causing an argument with their partner. These findings also suggest that ACEs remain relevant for women in adulthood, contributing to women’s engagement in sexual risk behaviors. There is a clear need for integrated trauma and HIV risk reduction interventions, which have improved the health of women living with HIV who have experienced lifetime victimization, including ACEs (Chin et al., 2014; Heckman et al., 2011).

The current study aimed to understand how the heterogeneity in ACEs impacted health and behaviors among women experiencing IPV, however, other forms of diversity are important to address. While socio-demographic characteristics such as race and ethnicity, age, and income were not significantly related to our study variables, diversity in socio-demographics are epidemiologically and clinically meaningful. A large proportion of our sample identified as Black or African-American women living in low-income families according to the 2017 Federal Poverty Guidelines (Federal Register, 2016). Black women living in low-income families may experience structural inequalities through racism, sexism, and classism that place this population at a greater risk for poor sexual and mental health (Willie, Kershaw, Campbell, & Alexander, 2017). Further, some research suggest that Black women report a high prevalence of IPV (Black et al., 2011). While mental health interventions are needed to address the implications of both childhood and IPV victimization, these interventions also need to be tailored to the cultural experiences of this population and financially accessible. Moreover, HIV is a leading cause of mortality among Black women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014), and our finding linking psychological IPV and sexual risk behaviors might provide a potential target for sexual health interventions for Black women experiencing IPV. This is particularly important as 87% of new HIV diagnoses among women are attributed to heterosexual sex (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017).

Despite the novelty of these findings, certain limitations should be noted. First, causality cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design; however, ACEs must have preceded IPV. There is a potential for social desirability, participation, and selection bias given the use of self-reported data. The self-report nature of women’s ACEs and IPV victimization may have been shaped by their willingness and comfort to disclose these personal experiences. If the prevalence of ACEs and IPV victimization is under-reported in this study, then the regression estimates would be biased towards the null. Also, since ACEs occurred in the past, it is possible that these experiences were under-reported due to difficulty recalling these events. Further our modest sample size (< 250) and focus on only seven specific forms of ACEs may have limited the number and distinctiveness of our subgroups. Future research should address these limitations by conducting latent profile analyses on a larger sample of women experiencing IPV, and include other forms of ACEs such as living with someone with a substance use disorder, experiencing economic hardship, and living with a parent who has been involved in the criminal justice system. Finally, our data collection was based on convenience sampling in the northeast region of the United States, which could have limited the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that ACEs are common among women experiencing IPV. Within this population, two profiles were at increased risk of poor mental health. Our findings advance current research by highlighting the heterogeneity in women’s ACEs in this population and identifying subgroups with varying risk of mental health.

If our findings are replicated with larger and more diverse samples, there are potential implications for prevention and intervention efforts. Given the long-term effects of ACEs, it is important to implement evidence-based strategies that reduce the incidence of ACEs among young women and girls. For example, Essentials for Childhood is a CDC framework that uses state-level efforts to prevent ACEs by focusing on the positive development of children and families in communities (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2013). One way this framework tackles ACE prevention is by partnering with local coalitions and leaders to promote positive community norms on safe, nurturing relationships (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2013). Although only five states have received CDC funding for this prevention program, if shown effective, it could be used as an evidence-based framework to implement state-level efforts on ACE prevention.

In the context of secondary prevention interventions, women experiencing IPV can benefit from mental health interventions (Hackett, McWhirter, & Lesher, 2015). Given the patterns of ACEs for women experiencing IPV, the effectiveness of mental health interventions may be enhanced by tailoring intervention components to address ACEs as a determinant of women’s mental health. Also, an intervention could identify women’s internal working models of romantic relationships and promote egalitarian and non-violent schemas between romantic partners. Some studies have shown preliminary evidence of mental health interventions modifying internal working models of coping strategies among women who experienced child sexual abuse (Walker-Williams & Fouché, 2015). Addressing how romantic partners can behave in nonviolent ways may assist in disrupting the continuation of the intergenerational transmission of IPV. Next, women experiencing IPV with at least moderate levels of ACEs may benefit the most from an integrated mental health intervention. In the HIV literature, trauma coping interventions among women and men living with HIV who experienced childhood sexual abuse have successfully improved mental health (Sikkema et al., 2008). Building upon these effective integrated interventions to focus on the mental health implications of ACEs and IPV victimization may enhance the wellbeing and quality of life of women experiencing IPV who also experienced ACEs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research described here was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R03DA17668) and the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH020031, F31MH113508, and R25MH083620).

References

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, & McClelland DC (1977). Social learning theory.

- Bensley L, Van Eenwyk J, & Wynkoop Simmons K (2003). Childhood family violence history and women’s risk for intimate partner violence and poor health. American journal of preventive medicine, 25(1), 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, & Fink L (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual: Harcourt Brace & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child abuse & neglect, 27(2), 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, et al. (2011). National intimate partner and sexual violence survey. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, & Donenberg GR (2006). Mechanisms linking violence exposure to health risk behavior in adolescence: Motivation to cope and sensation seeking. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(6), 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Kaltman S, & Green BL (2008). Accumulated childhood trauma and symptom complexity. Journal of traumatic stress, 21(2), 223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet, 359(9314), 1331–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Greeson MR, Bybee D, & Raja S (2008). The co-occurrence of childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sexual harassment: a mediational model of posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol, 76(2), 194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, & Kim HK (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner abuse, 3(2), 231–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BE, McNutt L-A, & Choi DY (2003). Childhood and adult abuse among women in primary health care effects on mental health. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(8), 924–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, & Soromenho G (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of classification, 13(2), 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). HIV Surveillance Report.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). HIV Among Women. Retrieved 10/18/2017, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/gender/women/cdc-hiv-women.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. (2013). Essentials for childhood: Steps to create safe, stable, and nurturing relationships.

- Chin D, Myers HF, Zhang M, Loeb T, Ullman JB, Wyatt GE, et al. (2014). Who improved in a trauma intervention for HIV-positive women with child sexual abuse histories? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(2), 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, & Messman-Moore TL (2007). Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child maltreatment, 12(2), 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B (1993). A history of abuse is a major risk factor for abusing the next generation. Current controversies on family violence, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. (2016). Poverty Guidelines. Retrieved 9–14, 2017, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2013). Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: an update. JAMA pediatrics, 167(7), 614–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, & Perry K (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological assessment, 9(4), 445. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, & O’Campo P (2007). HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma Violence Abuse, 8(2), 178–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin RL, Iverson KM, Mitchell K, Vaughn R, & Resick PA (2013). The impact of childhood maltreatment on PTSD symptoms among female survivors of intimate partner violence. Violence and victims, 28(6), 984–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover AR, Kaukinen C, & Fox KA (2008). The relationship between violence in the family of origin and dating violence among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett S, McWhirter PT, & Lesher S (2015). The therapeutic efficacy of domestic violence victim interventions. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838014566720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lee Y, Ozonoff A, & Van Wert MJ (2010). The impact of multiple types of child maltreatment on subsequent risk behaviors among women during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of youth and adolescence, 39(5), 528–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, & Grych J (2013). The Web of Violence.

- Healthy People 2020. (September-30-17). Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved 9-4-17, 2017, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

- Heckman TG, Sikkema KJ, Hansen N, Kochman A, Heh V, Neufeld S, et al. (2011). A randomized clinical trial of a coping improvement group intervention for HIV-infected older adults. Journal of behavioral medicine, 34(2), 102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, & Slep AMS (2002). Do child abuse and interparental violence lead to adulthood family violence? Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 864–870. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, & Marchbanks PA (2001). Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Family planning perspectives, 206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll S (2014). Resource caravans and resource caravan passageways: a new paradigm for trauma responding. Intervention, 12, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Buckley H, & Whelan S (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child abuse & neglect, 32(8), 797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooven C, Nurius PS, Logan-Greene P, & Thompson EA (2012). Childhood violence exposure: Cumulative and specific effects on adult mental health. Journal of family violence, 27(6), 511–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Israel E, & Stover C (2009). Intimate partner violence: the role of the relationship between perpetrators and children who witness violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(10), 1755–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, & Oros CJ (1982). Sexual Experiences Survey: a research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 50(3), 455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MM, London MJ, & Bridgett DJ (2014). Using SEM to examine emotion regulation and revictimization in predicting PTSD symptoms among childhood abuse survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(6), 644. [Google Scholar]

- Logan T, Walker R, Jordan CE, & Leukefeld CG (2006). Women and victimization: Contributing factors, interventions, and implications: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AL (1987). Latent class analysis: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Elklit A, & Shevlin M (2017). Child Maltreatment Typologies and Intimate Partner Violence: Findings From a Danish National Study of Young Adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260517689889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2012). Mplus statistical modeling software: Release 7.0. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2014). Child Maltreatment. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. (1990). SAS/STAT user’s guide: Version 6 (Vol. 2): Sas Inst. [Google Scholar]

- Seehuus M, Clifton J, & Rellini AH (2015). The role of family environment and multiple forms of childhood abuse in the shaping of sexual function and satisfaction in women. Archives of sexual behavior, 44(6), 1595–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, & Carey MP (2010). Child maltreatment and women’s adult sexual risk behavior: Childhood sexual abuse as a unique risk factor. Child maltreatment, 15(4), 324–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, & Urban MA (2006). Childhood sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior among men and women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 74(4), 720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Meade CS, Kochman A, & Fox AM (2009). Psychosocial predictors of sexual HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-positive adults with a sexual abuse history in childhood. Archives of sexual behavior, 38(1), 121–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Wilson PA, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Neufeld S, Ghebremichael MS, et al. (2008). Effects of a coping intervention on transmission risk behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS and a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 47(4), 506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer MI, Anglin TM, yu Song L, & Lunghofer L (1995). Adolescents’ exposure to violence and associated symptoms of psychological trauma. Jama, 273(6), 477–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby S, & Warren W (2003). The conflict tactics scales handbook: Revised conflict tactics scale (CTS2) and CTS: Parent-child version (CTSPC). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of family issues, 17(3), 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child abuse & neglect, 22(4), 249–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM (1999). The validation of the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory. Violence and victims, 14(1), 25–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Williams HJ, & Fouché A (2015). A strengths-based group intervention for women who experienced child sexual abuse. Research on Social Work Practice, 1049731515581627. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield CL, Anda RF, Dube SR, & Felitti VJ (2003). Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 166–185. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja S, & Dutton MA (2014). Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation. Child abuse & neglect, 38(4), 650–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie T, Kershaw T, Campbell JC, & Alexander KA (2017). Intimate partner violence and PrEP acceptability among low-income, young black women: exploring the mediating role of reproductive coercion. AIDS and behavior, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie TC, Powell A, Lewis J, Callands T, & Kershaw T (2017). Who is at risk for intimate partner violence victimization: using latent class analysis to explore interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration among pregnant young couples. Violence and victims, 32(3), 545–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, & Widom CS (2011). Pathways from childhood abuse and neglect to HIV-risk sexual behavior in middle adulthood. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 79(2), 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Williams JK, Kitchen CR, Loeb T, Carmona JV, et al. (2002). Does a history of trauma contribute to HIV risk for women of color? Implications for prevention and policy. American Journal of Public Health, 92(4), 660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Capezza NM, & Parker D (2011). An interpersonally based intervention for low-income pregnant women with intimate partner violence: a pilot study. Archives of women’s mental health, 14(1), 55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]