Abstract

ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowire arrays were fabricated by a straightforward approach which combine two simple, cost effective and large-scale preparation methods: (i) thermal oxidation in air of a zinc foil for obtaining ZnO nanowire arrays and (ii) radio frequency magnetron sputtering for covering the surface of the ZnO nanowires with a CuxO thin film. The structural, compositional, morphological and optical properties of the high aspect ratio ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays were investigated. Individual ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires were contacted with Pt electrodes by means of electron beam lithography technique, diode behaviour being demonstrated. Further it was found that these n-p radial heterojunction diodes based on single ZnO-CuxO nanowires exhibit a change in the current under UV light illumination and therefore behaving as photodetectors.

Introduction

The design and fabrication of nanostructures with complex architectures can fuel the new trends in modern technologies by enabling the development of low dimensional devices with improved performances and additional functionalities. In this context, the fabrication of one-dimensional or quasi one-dimensional nanostructures such us semiconductor heterojunctions or metal/semiconductor junctions is an attractive focus point for researchers1–3. Such one-dimensional heterojunctions can be built in different geometries: axial, radial or hierarchical/branched1,2. Nanowires represent an important class of nanostructures4,5 due to their one-dimension induced properties (high surface to volume ratio, quantum confinement, etc.), in some cases, quite different from the characteristics of the same material in the bulk form6. Semiconductor nanowires7 are intensively studied because of some specific features that can be easily tuned during the preparation stage8. Such nanostructures can find applications in optoelectronic and electronic devices like nanowire lasers9, field effect transistors10–13, solar cells14, photodetectors15, photocatalysts16, bio-sensors17, etc.

Furthermore, core-shell semiconductor heterojunctions lead to enhanced functionalities for a wide range of applications such as energy storage, solar cells, photocatalysis, photodetectors18–25. Also, various UV, visible and infrared radiation photodetectors based on core-shell nanowire arrays containing CdS-ZnO26, CuO-Si27, ZnO-NiO28, ZnO-Cu2O29, ZnO-TiO230 or CuO-ZnO31 have been reported.

Zinc oxide is a wide band gap n-type semiconductor (3.37 eV) with a high exciton binding energy (60 meV)32. Cuprous oxide (Cu2O) and cupric oxide (CuO) are both naturally p-type semiconductors with direct narrow band gaps of 2.0 eV and 1.2 eV, respectively33, usually the mixture between these two copper oxides being labelled as CuxO33. A staggered gap (type II) band alignment can be obtained by combining ZnO and CuxO in n-p core-shell heterojunction structures34. This type II band alignment favors the spatial charge separation of electrons and holes at the interface that suppresses the recombination of photogenerated carriers34–36. Moreover, the advantage of such core-shell heterostuctures is related to an enhancement of the charge collection efficiency at the electrodes due to the internal field which appears at the interface between the p-n semiconductors (along the length of the nanowire ~µm range) and the separation of photogenerated charges which takes place along the radius of the nanowire (~nm range)1,36. Therefore, such ZnO-CuO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowires are good candidates for the next generation of optoelectronic devices. A higher solar absorbance can be achieved in a ZnO-CuxO core-shell low dimensional heterostructures compared to the individual components with similar geometry and consequently this leads to an improved functionality e.g. an enhancement of the photocurrent under UV illumination28. To date, the number of papers reporting on the preparation of ZnO-CuO core-shell radial heterojunctions is still scarce. ZnO cores with different types of morphologies, i.e. nanorods34,37,38, nanopillars39, nanowires35,40,41 and nanospheres42 were synthesized by aqueous chemical growth40, hydrothermal synthesis41 and chemical vapour deposition35. Further these were covered with CuO shells obtained by combining various techniques: electrodeposition with thermal oxidation in an oxygen atmosphere40, electrophoresis with electroless deposition41 and sputtering with thermal oxidation in oxygen atmosphere inside the chemical vapour deposition tube furnace35.

In this context, the present report is focused on the preparation by a straightforward, simple and cheap approach of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays and on the development of n-p diodes based on a single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowire that can be used as UV photodetectors. Thus, the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays were obtained by combining zinc foil thermal oxidation in air for ZnO core and radio frequency magnetron sputtering for CuxO shell. The as prepared ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires were investigated from the morphological, structural, optical and compositional point-of-view. Further, by contacting single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires using electron beam lithography, diodes were fabricated. The n-p diodes based on single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowires exhibited a change in current under UV light illumination acting therefore as a photodetector, the key parameters like responsivity, the external quantum efficiency and the detectivity being evaluated. Such UV photodetectors have applications in fields such as biological analysis, radiation detection, flame detection, air purification, advanced communications, ozone sensing and leak detection43,44.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals employed were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. The zinc foil was bought from Alfa Aesar Thermo Fisher Scientific. The copper oxide (99.7% purity), platinum (99.99% purity) and titanium (99.99% purity) sputtering targets and the gold wire (99.99% purity) were provided by Kurt J. Lesker Company Ltd. (UK).

Preparation of ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires arrays

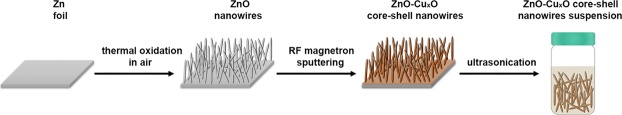

A representation of the two steps involved in the preparation of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays is depicted in Fig. 1. ZnO nanowire arrays were obtained by thermal oxidation in air, the approach being described in our previously papers13,45. Briefly, 2 cm2 zinc foils were subsequently cleaned in acetone and isopropyl alcohol for 5 min in an ultrasonic cleaner (Elma Schmidbauer GmbH), rinsed in deionized water and dried under a nitrogen spray gun. Then, the cleaned Zn foils were thermally oxidized in air in a furnace (Nabertherm GmbH). The zinc foils thickness was 1 mm and the temperature and time of oxidation in the furnace were 500 °C for 12 h. In the second step, the surface of the ZnO nanowires was covered with a thin film of CuxO by radio frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering (Tectra GmbH Physikalische Instrumente). The power applied on the magnetron was 100 W, the pressure in the chamber was 5.4 × 10−3 mbar in an Ar atmosphere with a purity of 9.6 (99,9999%) from Linde and the copper oxide target used had a diameter of 2 inch and a thickness of 0.125 inch. Prior to the fabrication of the electronic devices, the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays prepared on zinc foils were transferred in ultrapure isopropyl alcohol by ultrasonication resulting in a ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires suspension.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the steps involved in the preparation of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays.

Fabrication of n-p diodes based on single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowires

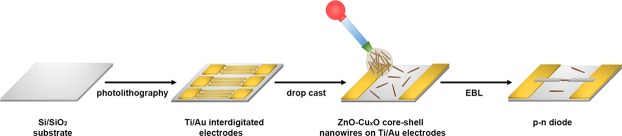

A schematic representation of the main steps implied in contacting single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowires is illustrated in Fig. 2. Hence, metallic interdigitated electrodes of Ti/Au (10/100 nm) on Si/SiO2 (the thickness of SiO2 was 50 nm) substrates were fabricated using photolithography, RF magnetron sputtering and thermal vacuum evaporation. Photolithography was made using a EVG 620 Mask Alignment System and for the thin film deposition techniques a Tectra equipment was employed. Further, droplets of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires suspension were dripped onto Si/SiO2 substrates containing Ti/Au electrodes. The single ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowires were contacted with Pt electrodes using electron beam lithography (EBL) and magnetron sputtering. All the lithographic equipment used in the electronic devices fabrication process is placed into a cleanroom facility ISO 5 and ISO 6.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the steps involved in the fabrication of the electronic devices based on single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowires.

Characterization techniques

The morphological, structural, optical, compositional and surface chemistry properties of the as prepared ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays were evaluated. The morphology was characterized using a Zeiss Merlin Compact field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) and a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (TEM: Cs probe-corrected JEM ARM 200F analytical electron microscope). The crystalline structure was identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD) employing a Bruker AXS D8 Advance instrument with Cu Ka radiation (λ = 0.154 nm). The optical properties were studied by means of reflectance and photoluminescence spectroscopy using a Perkin–Elmer Lambda 45 UV–VIS spectrophotometer equipped with an integrating sphere and a FL 920 Edinburgh Instruments spectrometer with a 450 W Xe lamp excitation and double monochromators on both excitation and emission, respectively. The compositional and surface chemistry properties were explored by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) in TEM and X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). XPS measurements were carried out in an AXIS Ultra DLD (Kratos Surface Analysis) setup equipped with an 180° hemispherical analyser, using Al Kα1 (1486.74 eV) radiation produced by a monochromatized X-Ray source at an operating power of 300 W (12 kV × 25 mA). The base pressure in the analysis chamber was at least 1.0 × 10−8 mbar. Partially charge compensation was reached by using a flood gun operating at 1.52 A filament current, 2.73 V charge balance, 2.02 V filament bias.

The electrical and photoelectrical measurements of the electronic devices based on single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowires were performed using a Keithley 4200 SCS and a Cascade Microtech MPS 150 probe station, a Siglent SPD3303S source, a laser diode module (having a wavelength of 405 nm) from Laser Components GmbH and a 365 nm NICHIA light emitting diode (LED), at room temperature.

Results and Discussion

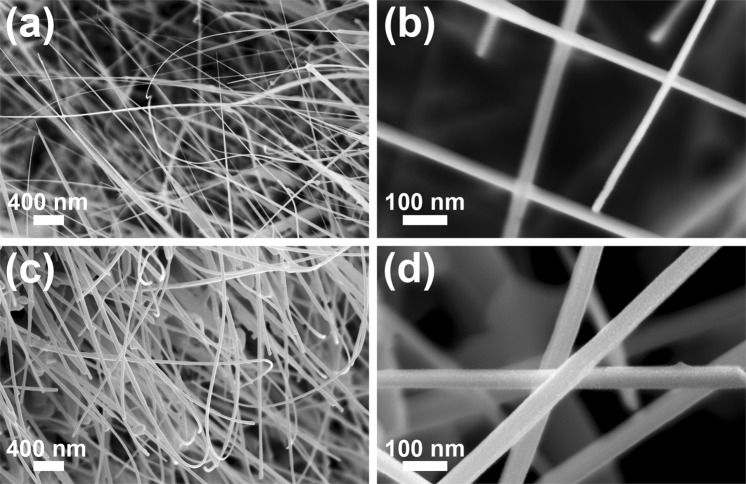

Morphological characterization

The FESEM images of the pristine ZnO (Fig. 3(a,b)) and of the ZnO-CuxO (Fig. 3(c,d)) nanostructures show that the zinc foil is completely covered by nanowires featured by a high aspect ratio having lengths up to 30 µm and the diameters in the nanometer range. The measurements reveal that the cylindrical shape of the ZnO nanowires is preserved after the deposition of the CuxO layer. Based on the diameter values of the ZnO nanowires before (~30 nm) and after the CuxO deposition (~60 nm), the thickness of the CuxO layer can be estimated at around 15 nm. The FESEM images at a lower magnification (Fig. S1(a,b)) display that the Zn foil surface is uniformly covered with nanowires arrays.

Figure 3.

FESEM images at two magnifications of the (a,b) pristine ZnO nanowire arrays and (c,d) ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays.

Structural, optical, surface chemistry and compositional properties

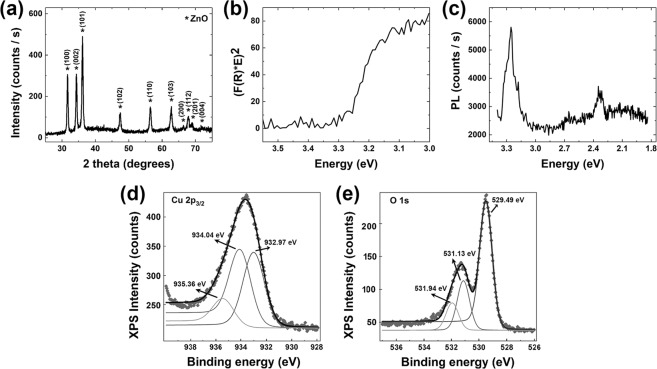

The structural and optical properties of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays (Fig. 4(a–c)) evidenced only the ZnO signature (according to our previously studies13,45) taking into account that the CuxO layers deposited by RF magnetron sputtering are very thin and usually amorphous46,47. The XRD pattern (Fig. 4(a)) reveals diffraction peaks at 2θ values of: 31.7°, 34.4°, 36.2°, 47.5°, 56.6°, 62.8°, 66.3°, 67.9°, 69.1° and 72.5° corresponding to the Miller indexes of the reflecting planes for ZnO growth in a hexagonal wurtzite phase (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), (201) and (004) according to the JCPDS reference code 00-036-1451. From the reflectance data, the band gap value was estimated to be around 3.28 eV by plotting (F(R)*E)2 versus the photon energy (E) (Fig. 4(b)), where F(R) is the Kubelka-Munk function, with F(R) = (1-R)1/2/2R and R the measured diffuse reflectance. The photoluminescence spectrum (Fig. 4(c)) exhibits two emission bands: one intense and sharp, centred at approximately 3.26 eV and another one weak, broad, centred at approximately 2.24 eV. The UV emission band is due to the radiative recombination of exciton pairs produced by fundamental photoexcitation48, while the emission observed in the visible range is associated with defects: oxygen vacancies, zinc vacancies, oxygen interstitials, zinc interstitials or surface related defects48,49.

Figure 4.

(a) XRD pattern, (b) representation of Kubelka-Munk function employed to estimate the band gap value, (c) photoluminescence spectrum, (d,e) High resolution XPS spectra of Cu 2p3/2 and O 1 s core levels for the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire arrays.

In order to evidence the presence of the CuxO, the surface composition of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires was investigated by XPS measurements (Fig. 4(d,e)). The XPS high resolution core level spectra have been recorded using Field of View 2 lens mode, 20 eV pass energy and a 110 µm aperture. The binding energy scale for all XPS spectra were calibrated to the C 1 s standard value of 284.6 eV. The core level spectra have been deconvoluted employing Voigt profiles, based on the methods described in50.

The atomic composition has been determined by using the integral areas provided by the deconvolution procedure normed to the atomic sensitivity factors provided by51. The high resolution XPS spectrum for Cu 2p3/2 from Fig. 4(d) show a broad peak deconvoluted in three peaks centred at 932.97 eV, 934.04 eV and 935.35 eV that can be attributed to CuO, Cu2O and to a surface contamination with carbon of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires. The high resolution XPS spectrum for O 1 s Fig. 4(e) exhibit a doublet peak deconvoluted in three peaks centred at 529.49 eV, 531.13 eV and 531.91 eV. The peak located at 529.49 is attributed to the oxygen in CuO and ZnO. The second peak can be assigned to Cu2O or to ZnO with oxygen-deficiency52 and the last peak is related to the surface contamination with carbon found also in the XPS spectrum for Cu 2p3/2. The CuO/Cu2O ratio (1:1) obtained by deconvolution of Cu 2p3/2, proves that the CuxO shell of the ZnO nanowires is a mixture of CuO and Cu2O.

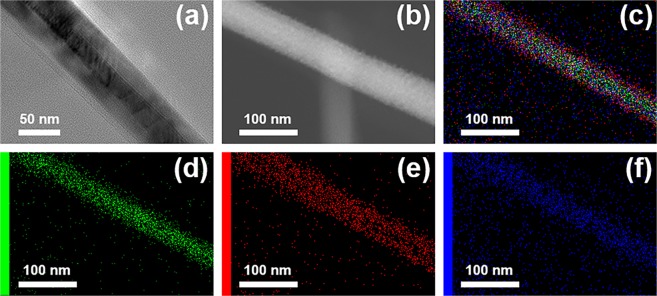

TEM (Fig. 5(a)) and STEM (Fig. 5(b)) images of a single ZnO-CuxO nanowire evidenced the core-shell type structure, confirming also the final diameter value (~60 nm) of the core-shell nanowire and the thickness value of the CuxO shell (~15 nm) estimated also from the FESEM images (Fig. 3(b,d)).

Figure 5.

(a) TEM image, (b) STEM image and (c) EDX elemental mapping of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell heterojunction nanowire; (d–f) EDX elemental mappings of Zn, Cu and O respectively.

Moreover, Fig. 5(b–f) show a STEM image of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire and its EDX elemental mappings with Zn K (zinc), Cu K (copper) and O K (oxygen), proving that the single nanowire contains only these elements. Furthermore, the EDX analysis emphasizes the distribution of Zn K only in the core, Cu K up to the edges of the wire and O K along the entire width of the nanowire.

Electrical and photoelectrical properties

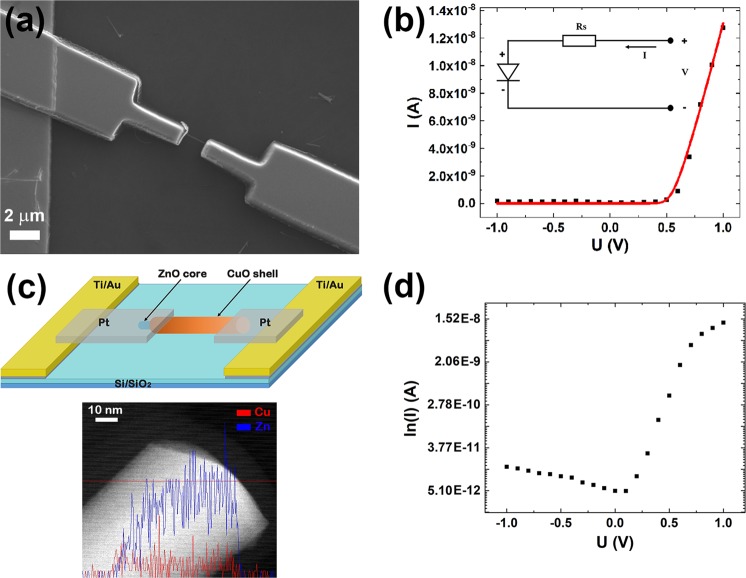

In order to investigate the electrical properties of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowire, single nanowires were placed on the Ti/Au metallic interdigitated electrodes. EBL was employed for designing the metallic contacts that connect the ends of the single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire to the Ti/Au electrodes using a sacrificial resist layer sensitive to the electron beam (poly(methyl methacrylate) - PMMA). The Pt thin film electrode was deposited by magnetron sputtering and had a thickness of 250 nm. Figure 6(a) presents a SEM image of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire contacted with Pt metallic electrodes.

Figure 6.

(a) SEM image, (b) current-voltage characteristic (black squares) and theoretical fitting (red curve), (c) up: schematic representation, down: EDS Line profile analysis by STEM mode of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire partially uncovered at one end and (d) semilogarithmic representation of the current-voltage characteristic of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowire contacted by EBL. Inset: the equivalent circuit model for a non-ideal diode, with an ideal diode and a parasitic series resistance (RS), used in the theoretical fitting.

The electrical measurements were carried out at room temperature in a 2-points configuration. The current-voltage characteristic of a single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowire contacted by EBL exhibited an asymmetric shape and thus, a rectifying behaviour (Fig. 6(b) black dots), arising from the ZnO-CuxO interface, typical for an n-p diode34. This electrical comportment can be explained taking into account that the deposition of the CuxO is carried on the ZnO nanowires still connected to the original zinc foils. Consequently the CuxO layer cannot cover the end of the ZnO nanowires where they are grown from the zinc foil. Further during the ultrasonication step, the split-off process of the core-shell nanowires from the zinc foil substrate results in exposing the uncovered ZnO core at one end of the nanowire. The EDS Line profile analysis by STEM (Fig. 6(c) down) exhibits a ZnO-CuxO nanowire partially uncovered by the CuxO shell at one end of the nanowire, proving our supposition regarding the ultrasonication process. Figure 6(c) up reveals a schematic representation of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowire contacted with Pt by EBL exhibiting a rectifying behaviour. It has to be mentioned that a back-to-back diode like behaviour as one would expect from a symmetrical structure was observed for only a small percentage of the single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires contacted by EBL (Fig. S2). Analyzing the electrical transport data, a direct-reverse ratio of about 103 was estimated from the semilogarithmic representation of the current-voltage characteristic of the single ZnO-CuxO radial heterojunction nanowire (Fig. 6(d)).

In order to determine the ideality factor of the diode, we considered a non-ideal n-p diode. Usually, for this type of device an equivalent circuit model consisting of an ideal diode with a parasitic series resistance RS and two parallel shunt resistances, attributed to losses that may occur at the n-p junction and to the metallic/semiconductor interface can be considered53.

The general equation describing the current flow for this model is:

| 1 |

In our case, we used an equivalent circuit model having an ideal diode and a parasitic series resistance (RS) (Fig. 6(b) inset)53,54. The parasitic series resistance represents the resistance of the single ZnO-CuxO nanowire. Thus, the equation describing the current flow through the n-p diode is:

| 2 |

where I is the current flow through the non-ideal n-p diode, IS being the reverse saturation current, U is the applied voltage, RS is the parasitic series resistance, n is the ideality factor, VT is the thermal voltage. An analytical solution for Eq. (2) can be calculated based on the Lambert W function55. Lambert W function represents the solution of the equation: . Hence, the analytical solution for Eq. (2) in terms of Lambert W function is53,54:

| 3 |

The experimental data (Fig. 6(b) black squares) for the current-voltage characteristic of an n-p diode based on a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire was fitted (Fig. 6(b) red line) using Eq. (3) for the proposed equivalent circuit model, containing an ideal diode and a parasitic series resistance. Specific n-p diode characteristic parameters were determined directly from the fitting: RS = 1.66 × 107 Ω, IS = 6.69 × 10−12 A and n = 1.3. The value obtained for the ideality factor and the direct-reverse ratio of about 103 are in agreement with values reported in the literature for diodes based on single nanowires11,56,57.

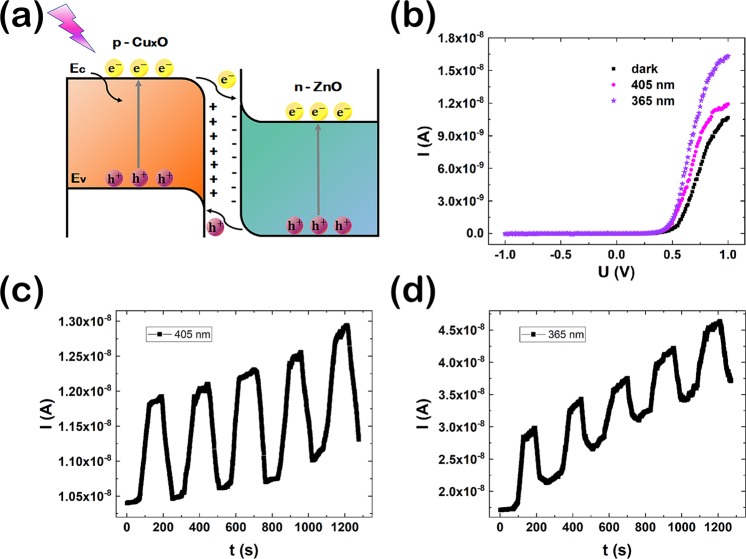

Single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires integrated in n-p diode devices can be key components for the next generation of ultra-miniaturised photodetectors. In a photodetector configuration, ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires can lead to an enhancement of the photocurrent due to the suppression of the electron-hole recombination. Thus, the photoelectric properties of the fabricated n-p diodes based on a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire were investigated. A schematic representation of the band diagram alignment for the n-p ZnO-CuxO heterojunction formed at the interface between the ZnO core and the CuxO shell is shown in Fig. 7(a).

Figure 7.

(a) Band diagram of a ZnO-CuxO heterojunction under UV illumination, (b) Current-voltage characteristics under dark (black dots), 405 nm UV illumination (magenta dots) and 365 nm UV illumination (purple stars), Current-time characteristic under (c) 405 nm UV illumination and (d) 365 nm UV illumination of a n-p ZnO-CuxO diode.

Under the UV light illumination of the n-p ZnO-CuxO heterojunction, electrons from the valance band (EV) are excited in the conduction band (EC), generating holes in the valence band. Owed to the type II band alignment between ZnO and CuxO, the photogenerated electrons excited in the conduction band of CuxO are jumping towards the conduction band of ZnO, while the photogenerated holes from the valence of ZnO are jumping towards the valence band of CuxO. In this way, the photogenerated charges (electrons and holes) are suppressed to recombine, improving the charge separation efficiently at the ZnO-CuxO interface26,34.

The current-voltage characteristics for an n-p diode based on a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire in dark (black dots) and under UV illumination at 405 nm wavelength (magenta dots) and at 365 nm wavelength (purple stars) in forward and reverse bias are presented in Fig. 7(b). The current-voltage characteristics for both dark and illumination conditions have a nonlinear shape due to the formation of an n-p heterojunction at the interface between the ZnO core and the CuxO layer. The increase in the photocurrent of the n-p diode can be attributed to the formation of the type II band alignment between ZnO and CuxO resulting in an improving of the charge separation at the interface between the two semiconductors26,34.

Figure 7(c,d) reveals the time-dependent photoresponse of a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire-based photodetector under UV illumination at 405 nm wavelength and at 365 nm wavelength, at a bias of 1 V. The rise time and the decay time are 43 s for both of them and the photocurrent gain is 1.8 nA at 405 nm wavelength and 17 nA at 365 nm.

An increase of the photocurrent intensity in time under UV illumination can be observed due most probably to a heating effect of the ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire induced during illumination or due to the Joule heating (we deal with a current density of about 300 A/cm2). The values of the key parameters for a photodetector, the responsivity (Rλ), the external quantum efficiency (EQE) and the detectivity (D*) can be estimated using the following equations57:

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

where ΔI is the difference between photocurrent and dark current, P is the incident light power, S is the effective illuminated area, h is the Planck constant, c is the speed of light, e is the elementary charge, λ is the light wavelength and Idark is the dark current. Based on the values of the incident light powers, 63.7 mW/cm2 for 405 nm and 4.55 mW/cm2 for 365 nm respectively, the effective illuminated area (10−9 cm2), at a bias of 1 V, the Rλ, EQE and D* were estimated to be: 3.14 A/W, 9.51% and 5.39 × 109 Jones for 405 nm and 43.95 A/W, 149.3% and 75.51 × 109 Jones for 365 nm, respectively. These values are in agreement with those reported in the literature for other photodetectors based on InP, GaAs/AlGaAs, PbTe or ZnO-TiO2 nanowires30,58–60. These results confirm the potential application of the n-p diodes based on single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowires as UV photodetectors.

Conclusions

Arrays of ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowires with high aspect ratio (lengths up to 30 µm and diameters broadly around 60 nm) were prepared by a straightforward approach. Thermal oxidation of zinc foils in air was employed for obtaining ZnO nanowires (core) and subsequently RF magnetron sputtering was used to deposit on their surface a thin layer of CuxO (shell). Due to the amorphous nature of the deposited CuxO layer, the structural and optical investigations made on core-shell nanowires evidenced only the ZnO signature: hexagonal wurtzite phase, band gap of about 3.28 eV and the two typical emission bands. The compositional and surface chemistry measurements carried out on the core-shell nanowires evidenced that the core consists of ZnO and the shell of a 1:1 mixture of CuO and Cu2O. Using electron beam lithography, n-p diodes based on single ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowires were fabricated, their ideality factor being 1.3. The photocurrent measurements evidenced that the n-p diode based on a single ZnO-CuxO core-shell radial heterojunction nanowire can be used as UV photodetector with the following values for the characteristic parameters: the responsivity was 3.14 A/W for 405 nm and 43.95 A/W for 365 nm, the external quantum efficiency was 9.51% for 405 nm and 149.3% for 365 nm and the detectivity was 5.39 × 109 Jones for 405 nm and and 75.51 × 109 Jones for 365 nm. The specific properties including size and selectivity of the single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire-based photodetector for the UV domain recommends it for a wide range of applications in biological analysis, radiation detection, flame detection, air purification, advanced communications, ozone sensing and leak detection.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the Executive Agency for Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation Funding (UEFISCDI), Romania, Project code: PN-III-P2-2.1-PED-2016-1249, Project code: IDEI 124/2017 and by the Core Program, contract No. PN18-11 supported from the Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation. The authors thank to Dr. C.M. Teodorescu for the valuable comments and suggestions regarding the XPS analysis. The authors thank Dr. M. Secu for providing the 365 nm NICHIA LED.

Author Contributions

A.C., C.F. and I.E. had the idea of the work and of the experiments steps. A.C. and F.C. wrote parts of the paper, I.E. writing the final version. N.P. performed the optical measurements, gave valuable advices about the all experiments and made the correction of the manuscript. N.A. obtained and analyzed the XPS data. A.K. helped with the TEM measurements. A.C., C.F. and A.N. done the theoretical fitting of the electrical measurements. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of the current study are presented in the manuscript and supporting information.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Andreea Costas and Camelia Florica contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Andreea Costas, Email: andreea.costas@infim.ro.

Camelia Florica, Email: camelia.florica@infim.ro.

Ionut Enculescu, Email: encu@infim.ro.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-42060-w.

References

- 1.Barth S, Hernandez-Ramirez F, Holmes JD, Romano-Rodriguez A. Synthesis and applications of one-dimensional semiconductors. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2010;55:563–627. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2010.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mieszawska AJ, Jalilian R, Sumanasekera GU, Zamborini FP. The Synthesis and fabrication of one-dimensional nanoscale heterojunctions. Small. 2007;3:722–756. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu C, et al. Interface engineering on p-CuI/n-ZnO heterojunction for enhancing piezoelectric and piezo-phototronic performance. Nano Energy. 2016;26:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.05.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia Y, et al. One-dimensional nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and applications. Adv. Mater. 2003;15:353–389. doi: 10.1002/adma.200390087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jie J, Zhanga W, Bello I, Lee C-S, Lee S-T. One-dimensional II–VI nanostructures: Synthesis, properties and optoelectronic applications. Nano Today. 2010;5:313–336. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2010.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan H, Feng YP. Semiconductor nanowires and nanotubes: Effects of size and surface-to-volume ratio. ACS Nano. 2008;2:2410–2414. doi: 10.1021/nn8004872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu W, Lieber CM. Semiconductor nanowires. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2006;39:R387–R406. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/39/21/R01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce HJ, et al. III–V semiconductor nanowires for optoelectronic device applications. Prog. Quant. Electron. 2011;35:23–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pquantelec.2011.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pauzauskie PJ, Yang P. Nanowire photonics. Mater. Today. 2006;9:36–45. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(06)71652-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Qian F, Xiang J, Lieber CM. Nanowire electronic and optoelectronic devices. Mater. Today. 2006;9:18–27. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(06)71650-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Florica C, et al. Electrical properties of single CuO nanowires for device fabrication: Diodes and field effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;106:223501. doi: 10.1063/1.4921914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Florica C, Matei E, Costas A, Toimil Molares ME, Enculescu I. Field effect transistor with electrodeposited ZnO nanowire channel. Electrochim. Acta. 2014;137:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.05.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Florica C, Costas A, Kuncser A, Preda N, Enculescu I. High performance FETs based on ZnO nanowires synthesized by low cost methods. Nanotechnology. 2016;27:475303. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/27/47/475303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otnes G, Borgström MT. Towards high efficiency nanowire solar cells. Nano Today. 2017;12:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2016.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaPierre RR, Robson M, Azizur-Rahman KM, Kuyanov P. A review of III–V nanowire infrared photodetectors and sensors. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2017;50:123001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6463/aa5ab3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutka A, et al. Co doped ZnO nanowires as visible light photocatalysts. Solid State Sci. 2016;56:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2016.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patolsky F, Zheng G, Lieber CM. Nanowire-based biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:4260–4269. doi: 10.1021/ac069419j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauhon LJ, Gudiksen MS, Wang D, Lieber CM. Epitaxial core–shell and core–multishell nanowire heterostructures. Nature. 2002;420:57–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayeh SA, Mack NH, Huang JY, Picraux ST. Advanced core/multishell germanium/silicon nanowire heterostructures: The Au-diffusion bottleneck. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;99:023102. doi: 10.1063/1.3567932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia X, et al. High-quality metal oxide core/shell nanowire arrays on conductive substrates for electrochemical energy storage. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5531–5538. doi: 10.1021/nn301454q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grinblat G, et al. Luminescence and electrical properties of single ZnO/MgO core/shell nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;104:103113. doi: 10.1063/1.4868648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adachi MM, Anantram MP, Karim KS. Core-shell silicon nanowire solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1546. doi: 10.1038/srep01546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parize R, et al. ZnO/TiO2/Sb2S3 core–shell nanowire heterostructure for extremely thin absorber solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;121:9672–9680. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo L, Huang G-Y, Liao G, Ye L-H, Xu HQ. Band-inverted gaps in InAs/GaSb and GaSb/InAs core-shell nanowires. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38698. doi: 10.1038/srep38698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang F, Ding Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wang ZL. Piezo-phototronic effect enhanced visible and ultraviolet photodetection using a ZnO–CdS core–shell micro/nanowire. ACS Nano. 2012;6:9229–9236. doi: 10.1021/nn3035765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, et al. CdS/ZnO core/shell nanowire-built films for enhanced photodetecting and optoelectronic gas-sensing applications. Adv. Optical Mater. 2014;2:738–745. doi: 10.1002/adom.201400086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong Q. Self-powered ultrafast broadband photodetector based on p–n heterojunctions of CuO/Si nanowire array. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:20887–20894. doi: 10.1021/am5054338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ni P-N, Shan C-X, Wang S-P, Liu X-Y, Shen D-Z. Self-powered spectrum-selective photodetectors fabricated from n-ZnO/p-NiO core–shell nanowire arrays. J. Mater. Chem. 2013;C 1:4445–4449. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai Z, Zhang Y. Self-powered UV–visible photodetectors based on ZnO/Cu2O nanowire/electrolyte heterojunctions. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016;675:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.03.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao D, Sun H, Xin G, Lian J, Sawyer S. High quality ZnO–TiO2 core–shell nanowires for efficient ultraviolet sensing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014;314:872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.06.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S-B, et al. ZnO branched nanowires and the p-CuO/n-ZnO heterojunction nanostructured photodetector. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2013;12:263–269. doi: 10.1109/TNANO.2013.2243916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Djurisic AB, Ng AMC, Chen XY. ZnO nanostructures for optoelectronics: Material properties and device applications. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2010;34:191–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pquantelec.2010.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wijesundera RP. Fabrication of the CuO/Cu2O heterojunction using an electrodeposition technique for solar cell applications. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2010;25:045015. doi: 10.1088/0268-1242/25/4/045015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pal S, Maiti S, Maiti UN, Chattopadhyay KK. Low temperature solution processed ZnO/CuO heterojunction photocatalyst for visible light induced photo-degradation of organic pollutants. CrystEngComm. 2015;17:1464–1476. doi: 10.1039/C4CE02159B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan MA, Wahab Y, Muhammad R, Tahir M, Sakrani S. Catalyst-free fabrication of novel ZnO/CuO core-shell nanowires heterojunction: Controlled growth, structural and optoelectronic properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;435:718–732. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.11.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kayes BM, Atwater HA, Lewis NS. Comparison of the device physics principles of planar and radial p-n junction nanorod solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 2005;97:114302. doi: 10.1063/1.1901835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang R-C, Lin H-Y. ZnO–CuO core–shell nanorods and CuO-nanoparticle–ZnO-nanorod integrated structures. Appl. Phys. A. 2009;95:813–818. doi: 10.1007/s00339-009-5079-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao K-T, Shimpi P, Gao P-X. Thermal oxidation of Cu nanofilm on three-dimensional ZnO nanorod arrays. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:9564–9569. doi: 10.1039/c1jm10762c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui J, Gibson UJ. A simple two-step electrodeposition of Cu2O/ZnO nanopillar solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:6408–6412. doi: 10.1021/jp1004314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu J-K, et al. Fabrication and photoresponse of ZnO nanowires/CuO coaxial heterojunction. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013;8:387. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-8-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S, et al. Synthesis of vertically conformal ZnO/CuO core–shell nanowire arrays by electrophoresis-assisted electroless deposition. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:7377–7385. doi: 10.1021/jp410293j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, et al. Synthesis and investigation of novel ZnO–CuO core-shell nanospheres. Mater. Lett. 2016;174:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2016.03.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen H, Liu K, Hu L, Al-Ghamdi AA, Fang X. New concept ultraviolet photodetectors. Mater. Today. 2015;18:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alaie Z, Nejad SM, Yousefi MH. Recent advances in ultraviolet photodetectors. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015;29:16–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2014.02.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Florica C, Preda N, Costas A, Zgura I, Enculescu I. ZnO nanowires grown directly on zinc foils by thermal oxidation in air: Wetting and water adhesion properties. Mater. Lett. 2016;170:156–159. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2016.02.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn H-J, Shim H-S, Kim WB, Sung YE, Seong T-Y. Co-sputtering growth and electro-oxidation properties of Pt–CuO nanocomposites for direct methanol thin film fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2009;471:L39–L42. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rydosz A. Amorphous and nanocrystalline magnetron sputtered CuO thin films deposited on low temperature cofired ceramics substrates for gas sensor applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2014;14:1600–1607. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2014.2301031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khanlary MR, Vahedi V, Reyhani A. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanowires by thermal oxidation of Zn thin films at various temperatures. Molecules. 2012;17:5021–5029. doi: 10.3390/molecules17055021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reshchikov MA, et al. Luminescence properties of defects in ZnO. Physica B. 2007;401-402:358–361. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2007.08.187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teodorescu CM, Esteva JM, Karnatak RC, Afif AE. An approximation of the Voigt I profile for the fitting of experimental X-ray absorption data. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A. 1994;345:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0168-9002(94)90983-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagner CD, et al. Empirical atomic sensitivity factors for quantitative analysis by electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis. Surf. Interface Anal. 1981;3:211–225. doi: 10.1002/sia.740030506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Gan L, He H, Ye Z. Free-Standing Atomically Thin ZnO Layers via Oxidation of Zinc Chalcogenide Nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:13537–13543. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b02425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ortiz-Conde A, Garcia Sanchez FJ, Muci J. Exact analytical solutions of the forward non-ideal diode equation with series and shunt parasitic resistances. Solid-State Electron. 2000;44:1861–1864. doi: 10.1016/S0038-1101(00)00132-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banwell TC, Jayakumar A. Exact analytical solution for current flow through diode with series resistance. Electron. Lett. 2000;36:291–292. doi: 10.1049/el:20000301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lambert JH. Observationes variae in mathesin puram. Nova Acta Helv. 1758;3:128–168. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garnett EC, Yang P. Silicon nanowire radial p−n junction solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9224–9225. doi: 10.1021/ja8032907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hafez M, Al-Marzouki F, Mahmoud WE. Single crystalline quasi aligned one dimensional p-type Cu2O nanowire for improving Schottky barrier characteristics. Mater. Lett. 2011;65:1868–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2011.03.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan X, Li B, Wu Y, Zhang X, Ren X. A single crystalline InP nanowire photodetector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016;109:053109. doi: 10.1063/1.4960713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dai X, et al. GaAs/AlGaAs nanowire photodetector. Nano Lett. 2014;14:2688–2693. doi: 10.1021/nl5006004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gong XX, et al. Metal-semiconductor-metal infrared photodetector based on PbTe nanowires with fast response and recovery time. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;404:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.01.246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of the current study are presented in the manuscript and supporting information.