Abstract

Excess nutrient loading to nearshore environments has been linked to declining water quality and ecosystem health. Macro-algal blooms, eutrophication, and reduction in coral cover have been observed in West Maui, Hawaii, and linked to nutrient inputs from coastal submarine groundwater seeps. Here, we present a forty-year record of nitrogen isotopes (δ15N) of intra-crystalline coral skeletal organic matter in three coral cores collected at this site and evaluate the record in terms of changes in nitrogen sources. Our results show a dramatic increase in coral δ15N values after 1995, corresponding with the implementation of biological nutrient removal at the nearby Lahaina Wastewater Reclamation Facility (LWRF). High δ15N values are known to be strongly indicative of denitrification and sewage effluent, corroborating a previously suggested link between local wastewater injection and degradation of the reef environment. This record demonstrates the power of coral skeletal δ15N as a tool for evaluating nutrient dynamics within coral reef environments.

Introduction

Coral reefs are facing increasing stress from global climate change (e.g., increasing temperatures, ocean acidification, sea-level rise) combined with local stresses from over-fishing, sedimentation, and terrestrial sources of pollution1,2. Specifically, declining water quality in the coastal environment, related to factors such as upstream changes in catchment basin land-use (e.g., deforestation, agriculture), enhanced terrestrial runoff 3, submarine groundwater discharge (SGD)4,5 and coastal urbanization6, among others, is believed to be an important cause of coral reef decline7. Increased inputs of terrestrial nutrients can impact the structure of marine biotic communities and may lead to eutrophication, harmful algal blooms8, decreased coral abundance and diversity9, and increased macro-algal abundance3,10. In particular, excess inputs of nitrogen (N) and phosphorous can alter ecosystem function and structure by shifting reefs dominated by corals to algae dominance11,12, and increase vulnerability of reefs to coral disease13,14. High nutrient loading when coupled with low pH has also been shown to increase the sensitivity of corals to bioerosion15. Nutrient inputs to coral reefs can originate from a variety of different sources, and it is vital to identify specific sources in order to design and evaluate effective mitigation strategies. Coral skeleton geochemistry, particularly δ15N (δ15N = [[(15N:14Nsample)/(15N:14Nreference)] − 1] × 1000), provides one method for understanding changes in historic nutrient loading16–19.

δ15N measurements are commonly used to distinguish between different N sources20. Specifically, dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) derived from sewage typically has δ15N values ranging from +7‰ to +38‰, with values as high as 74‰ occurring at our study site20,21. This is due to a variety of processes that occur during sewage treatment, including bacterial denitrification of nitrate, nitrification of ammonia or ammonium, and ammonia volatilization. The net result of these processes is the consumption of nitrate, leaving the residual DIN pool heavily enriched in 15N20. δ15N of synthetic N fertilizer, which is often derived from atmospheric N2, ranges between −4‰ and +4‰22,23. The δ15N of marine nitrate, which is controlled by a complex balance of local and global biogeochemical processes, is typically between +4‰ and +7‰, with a deep ocean average value of approximately +5.5‰24. However, euphotic zone δ15N values can be higher due to uptake and utilization by phytoplankton25.

δ15N values have been used in a variety of different systems to investigate the impact of anthropogenic N fluxes. This includes tracing inputs of nitrate from septic tanks into groundwater26 and tracing runoff of fertilizer into various ecosystems27. Dissolved nitrate isotopes (δ15N and δ18O) have also been used to evaluate mixing of different anthropogenic nitrate sources in coastal and estuarine systems20,28,29. Organic matter δ15N has been applied for tracing N inputs to soils30, sediments31, fish32, crustaceans33, algae34,35, and food-webs36. Similarly, the δ15N of organic matter contained within scleractinian coral skeletons has been shown to directly relate to sources of N for corals18,37,38. As such, records of coral organic matter δ15N have been used to determine sources of N and changes in nutrient dynamics over various timescales17,18,37,39–45.

Here we use a new method (see methods below) to measure intra-crystalline δ15N in coral cores collected off the west coast of Maui, Hawaii in order to shed light on changes in N sources to the local reef system as they relate to coral reef health. Adjacent to a densely inhabited shoreline with known input from land-based sources of pollution, the reef at Kahekili Beach Park (KBP), in North Kannapali, Maui, Hawaii (Fig. 1) has shown signs of degradation since state monitoring began in 199546–48, including large, periodic macro-algal blooms49 and up to 40% loss of coral coverage between 1995 and 2005, with specific areas showing nearly 100% coral loss (termed “dead zones”)46. These “dead zones,” which are highly patchy and heterogeneously distributed throughout the reef, are characterized by a local high abundance of dead coral skeletons and represent areas of historical coral mortality46,47. Results of a study in 2009 suggested that coral cover and degradation at this site are associated with local fresh groundwater seeps that have been suspected as conduits for sewage effluent injected into the aquifer at the LWRF46,50. The discharging water is typically nutrient rich, and previous studies at this location employing hydrological models and δ15N in algae suggest a terrestrial N source characterized by denitrification, possibly sewage effluent35,50–54. Glenn et al. (2012; 2013)53,54 used dye tracers along with natural geochemical tracers and aerial thermal infrared imagery to confirm a direct hydrological link between the LWRF and the small submarine seeps discharging along the reef. However, it is possible that other sources of N downstream from the LWRF, or natural processes within the aquifer, are driving the elevated N concentrations and δ15N values. Specifically, there is no instrumental record of water quality or N content available for this site prior to the early 1990’s so it is hard to determine if the N loading and associated coral decline can be categorically attributed to the LWRF treated sewage injection. Therefore, an independent measure directly linking N input at the seeps and the sewage treatment facility (i.e. a “smoking gun”) in both a modern and historical context is needed.

Figure 1.

Kahakili Beach Park (KBP) and Lahaina Wastewater Reclamation Facility. Overview of the study site, showing the KBP coastline, LWRF, and surrounding area on the west shore of Maui, Hawaii. The red line shows the extent of the injection plume within the coastal aquifer as mapped by dye tracer experiments54. Cores LobataHead04 and LobataHead06 were collected within an active seeps area, while Core LobataHead07 was collected ~150 m to the south, away from the seeps (see inset). Imagery 2018 Google, map data 2018 Google.

Land-use in West Maui has historically been dominated by both sugar cane and pineapple cultivation. From the early 1900’s until 1979, land-use practices in this area remained relatively unchanged, with limited urban development along the coastline. Beginning in 1979, large scale plantation agriculture began to decline, with the area experiencing a 21% decline in agricultural land-use and a corresponding 43% increase in urban land use between 1979 and 200455. Much of this decline in agricultural area can be attributed to the closing of a major sugar cane plantation in 1999. Pineapple cultivation also began to decrease in the late 1990’s before stopping entirely in 200956. Much of this formerly agricultural land remains fallow today, with some sections converted to either diversified agriculture or urbanized areas. Currently, much of the coastline consists of commercial development, resorts, and golf courses, with former agricultural land and state forests on the slopes above.

The LWRF is located approximately three miles north of the town of Lahaina in the Kaanapali District of West Maui. The facility is responsible for treating all municipal sewage for the local community, which can swell to over 40,000 people during the tourist season. The facility generates a primary stream of tertiary treated wastewater, which is subsequently disposed on-site via four injection wells, along with a secondary stream of tertiary treated wastewater that is additionally disinfected using UV radiation to produce water that meets R-1 standards for reuse in local landscaping. Tertiary treatment consists of primary settling to remove suspended solids, secondary aerobic biodegradation by microbial metabolism to remove organic matter, and biological nutrient removal in order to remove DIN. The first plant at the LWRF was constructed in 1976 and is capable of an average flow capacity of about 3.2 million gallons per day (mgd). A second plant, with a capacity of 6.7 mgd, was constructed in 1985 and has now largely replaced the first plant for day-to-day operation. This second plant was upgraded in 1995 in order to incorporate biological nutrient removal as well as a partial UV disinfection system57. Due to an Environmental Protection Agency mandate, chlorination disinfection techniques were used from October 2011 until May 2014, after which full UV disinfection was operational. Detailed records of treated wastewater injection rates over the lifetime of the facility are not readily available, however today the plant processes an average of ~4 mgd of raw municipal sewage from the broader Lahaina area58.

Here we use δ15N of intra-crystalline coral skeletal organic matter in Porites lobata coral cores collected from three locations, representing sites adjacent to seep discharge and far from the direct seep influence, along the fringing reef at KBP to construct a record of δ15N in the water at each of the three sites. The KBP is located along the west shore of Maui, Hawaii ~0.5 km southwest of the LWRF (Fig. 1, see Glenn et al. (2013) for detailed site description54). Two of the cores collected (LobataHead04 and LobataHead06) were from within an active seep area52–54, whereas core LobataHead07 was collected ~150 m to the south, in an area of high coral cover and low bioerosion and background nutrient concentrations59. Intra-crystalline organic matter from each core was analyzed for δ15N variability using a newly developed analytical procedure (see methods). In this study we present a record of historic changes in N sources to the coast in relation to changes in land-use and sewage treatment practices upstream of KBP over the last several decades.

Results and Discussion

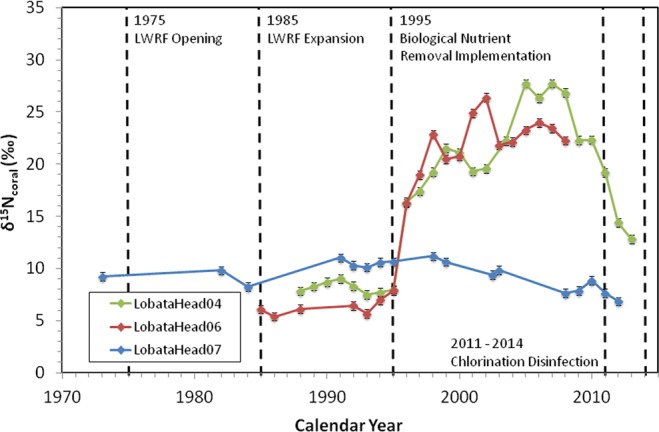

The coral skeletal δ15N values measured in cores collected adjacent to the SGD seeps (LobataHead04 and LobataHead06) show distinct trends compared to the coral collected outside the seep area (LobataHead07, Fig. 2). The largest differences are seen after 1995, with corals collected adjacent to the SGD seeps consistently showing δ15N values greater than +10‰, and as high as +27.7‰, while coral δ15N values from outside the seep area remain relatively constant, centered at ~+10‰. Prior to 1995, coral δ15N values from all three sites are more similar to each other, varying between +6 and +10‰.

Figure 2.

Historic record of coral skeletal δ15N. Coral skeletal δ15N values plotted through time. Major milestones in the LWRF operation are also noted. Cores LobataHead04 and LobataHead06 both show a sharp increase in δ15N between 1995 and 1996 in response to the implementation of biological nutrient removal at the LWRF, while core LobataHead07 does not show any response to LWRF activities.

Beginning in 1996, coral δ15N values adjacent to the SGD seeps increase rapidly, from less than +8‰ to over +16‰ in one year. Biological nutrient removal, consisting primarily of heterotrophic denitrification, was implemented at the LWRF beginning in 1995 to treat the wastewater prior to injection. This N removal process has been an integral part of the wastewater treatment facility since 1995. N removal continues within the anoxic groundwater plume downstream of the injection wells58. As a result, a large amount of N is removed prior to discharge at the SGD seeps, leaving behind DIN with an enriched δ15N fingerprint that discharges into the coastal zone at the submarine seeps. Upon discharge the groundwater with 15N enriched DIN mixes to various degrees with seawater which has DIN with lower δ15N values. This mixed, DIN pool which is still enriched in 15N relative to surrounding seawater is available for uptake by the corals and is recorded in the skeletal organic matter. The average aquifer transfer time between the injection wells and the SGD seeps, as determined through dye tracer experiments, is approximately 14 months53,54. Thus, the high δ15N coral signature observed starting in 1996 is most likely a direct response to the biological nutrient removal process implemented the previous year, providing a direct link between the nutrient-enriched SGD and the LWRF. If natural processes, such as denitrification along the flow path in the aquifer were the source of the high δ15N values and associated nutrient loads at the seeps, such values would have been seen prior to the start of biological nutrient removal process implementation at the LWRF.

Coral δ15N values from cores collected adjacent to the seeps continue to increase for the next decade, peaking between 2002 and 2007, and reaching a maximum of +27.7‰ in 2007 (LobataHead04) and +26.4‰ around 2002 (LobataHead06). Note that LobataHead06 was collected dead so there is some uncertainty as to the exact age model (see methods). However, coral δ15N values do not rise monotonically, instead displaying year-to-year variability, especially between 1998 and 2002. A direct comparison of δ15N values between the two corals collected at the seeps shows that while the overall trends are similar, the detailed patterns for these two coral heads are not identical. For example, coral δ15N values decrease slightly between 1999 and 2002 before increasing again in 2003 in LobataHead04, whereas coral δ15N values in LobataHead06 less than 16 m away increase sharply during the same time period, before decreasing again in 2003. This δ15N variability between LobataHead04 and LobataHead06 is likely due to changes in SGD flow rate, local hydrodynamics, and the degree of dilution with seawater at the individual coral collection site. Prouty et al.21,59 analyzed seep water and nearby seawater chemistry at this site during a 6-day intensive sampling campaign. The results of these studies revealed that bottom water carbonate chemistry, nutrient concentrations, and specifically nitrate δ15N were largely controlled by SGD discharge fluxes, as well as nearshore oceanographic conditions (e.g. wave height), and varied significantly over the sampling period. For example, nitrate concentrations within the seep discharge fluid varied from 0.45 µmol L−1 to over 70 µmol L−1, while nitrate δ15N values varied from less than +40‰ to almost +75‰, all during the 6-day period, demonstrating the highly dynamic nature of this reef location. Higher nitrate concentrations are observed at the shallowest sampling sites closest to the seep21,59 consistent with previous work at this site52–54. Collectively these data suggest that the two corals (LobataHead04 and LobataHead06) likely experienced somewhat different conditions both day-to-day and at any specific time. This could explain the variability observed in δ15N in each coral and the differences between these corals from 1998 to 2002. The variability in coral δ15N values is also consistent with other δ15N measurements from the study area, including those in particulate organic matter (POM) (this study, see Table 1), groundwater and seawater DIN53,54,59, and algal tissue35,51, capturing how differences in exposure to nutrient-enriched effluent and post-discharge mixing can lead to differences in δ15N. Despite the high variability in nitrate δ15N, the coral skeleton provides a time-integrated signal, meaning the overall signal is robust. Importantly, the δ15N variability between LobataHead04 and LobataHead06 is also much smaller than the primary denitrification signal observed after 1996.

Table 1.

Physical characteristics of coral cores and chemical characteristics of the surrounding seawater.

| Core ID | LobataHead04 | LobataHead06 | LobataHead07 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | SGD Seep | SGD Seep | Southern Drill Site |

| Latitude | 20° 56.326′ N | 20° 56.318′ N | 20° 56.236′ N |

| Longitude | 156° 41.587′ W | 156° 41.589′ W | 156° 41.611′ W |

| Distance From Seep (m) | 16 | 0 | 156 |

| Water Depth (m) | <2 | <2 | 3 |

| Collection Status | Alive | Dead | Alive |

| Isotope Date Range Sampled | 1988–2013 | 1983–2008 | 1973–2013 |

| Bioerosion (% vol)* | 5.9 | 14.6 | n/a |

| Growth Rate (cm yr−1)* | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.9 |

| Seawater Nitrate (µmol L−1)* | 0.41 ± 0.18 (n = 37) | 20.35 ± 23.32 (n = 37) | n/a |

| POM δ15N (‰) | +6.6 ± 2.1 (n = 17) | +3.4 ± 2.2 (n = 9) | |

| 2013 Seawater δ15NNO3 (‰) | +31.5 ± 2.1 (n = 3) | +8.0 ± 1.2 (n = 3) | |

| 2016 Seawater δ15NNO3 (‰)** | + 70.4 ± 6.5 (n = 28) | n/a | |

The above table contains a summary of the important physical and chemical characteristics of the coral cores and seawater surrounding each site. Bioerosion, growth rate and nitrate concentration data (indicated by *) were previously published in Prouty et al.21. 2016 seawater δ15NNO3 values (indicated by **) were previously published in Prouty et al.59. Values are reported as average ± standard deviation. Seawater nitrate concentrations and 2016 seawater δ15NNO3 values based on 6 day sampling period in March 2016, while 2013 seawater δ15NNO3 was measured on samples collected in December 2013.

In contrast to the high coral δ15N values observed after 1995 in the two cores collected adjacent to the SGD seeps, the coral core (LobataHead07) collected offshore in a low nutrient setting does not display an increase in δ15N. The isotopic composition of this core remains relatively stable around +10.5‰ prior to 1999, after which there is a gradual decrease to +6.9‰. The lack of any response to the implementation of biological nutrient removal at the LWRF is strong evidence that this area, located approximately 150 m south of the active SGD seeps, is outside the direct influence of the SGD-derived wastewater effluent, given both the low nutrient concentrations and high percentage of coral cover observed59. This core is therefore primarily reflecting trends in the DIN isotopic composition of coastal seawater and reflecting regional changes in background groundwater (including degree of denitrification within the aquifer and input from other sources) and seawater DIN δ15N not affected by the LWRF effluent. In addition, coral δ15N signatures may be influenced by coral feeding behavior. For example, corals can obtain nutrients from seawater directly60,61 when concentrations are high (as they are at the seeps), whereas that coral δ15N signal can be muted by heterotrophic feeding on a dynamically mixed N pool, particularly when DIN concentrations are lower (as they are at LobataHead07). The increased development, urbanization (24.5% increase in population between 2000 and 2010)46 and fertilizer use in golf courses in the region over time likely contribute to the decreasing δ15N trend seen in LobataHead07 from 1999 to 2012. These N sources typically have δ15N ratios lower than offshore seawater62.

The coral skeletal δ15N compositions of all cores show a decreasing trend by the mid-2000’s, with the trends being more dramatic in the two cores collected adjacent to the seep. We note that while the above described δ15N increases can only be due to denitrification, the more recent δ15N decreases may be explained by several other factors. The decreasing trend and lower values could be the result of changes in LWRF injection rates, decreases in the efficiency of the biological nutrient removal processes, or some other factor operating within the aquifer. However, since the coral skeleton records the combined result of these processes, it is difficult to identify the relative importance of each process. The ~3‰ decrease observed in LobataHead07 (southern core away from the seeps) over this time period suggests that a small portion of the overall decreasing trend in LobataHead04 and LobataHead06 may not be directly related to effluent injection at the LWRF, and instead related to more regional processes, such as increased urbanization and tourism as discussed above. However, the much larger (>10‰) decrease in the two cores adjacent to the seeps indicates the contribution of additional processes unique to the SGD influence. As previously mentioned, the LWRF effluent was subjected to chlorination disinfection prior to injection from October 2011 to May 2014, when UV disinfection was fully implemented. Chlorination disinfection may be responsible for suppressing microbial activity including that responsible for N removal58. This in turn would result in a decrease in the overall rate of denitrification, and thus an increase in rate of DIN discharge and a decrease in δ15N in the effluent DIN. Indeed, within 14 months of chlorination beginning at the LWRF, increased nutrient loads from SGD were observed on the ref.58, and at the same time LobataHead04 shows a decrease in δ15N from +19.2‰ to +12.8‰ between 2011 and 2013. Chlorination disinfection was discontinued in 2014 hence a rebound in δ15N would be expected after 2014. This rebound cannot be captured in our record since the coral cores were collected in 2013. However, this rebound in δ15N has been observed in dissolved nitrate at the site. In December 2013, the average seawater nitrate δ15N value at the seeps was +31.6‰ (this study, n = 3, Table 1) but in 2016 this value was over +70‰ (n = 28, Table 1)59. Both values are higher than those recorded in the coral skeleton likely because the corals do not derive their N directly from DIN and may include N from heterotrophy. However, as noted previously coral δ15N values in LobataHead04 start decreasing two years prior to the onset of chlorination, indicating that other factors in addition to the chlorination treatment have contributed to the overall trend. The exact N sources or processes that contribute to the decrease in δ15N, other than those associated with the LWRF, are hard to pinpoint but could be related to the large increase (~20%) in tourists visiting Maui and related increased contribution from fertilizer use in resorts and golf course landscaping62. Following the US financial crisis of 2007–2008, Maui’s economy turned around and entered a period of economic expansion in 2009, leading to the development of new beach resorts and an expansion of the Ka’anapali golf courses63.

The skeletal δ15N values for all 3 corals prior to 1995 are lower than those following the initiation of biological N removal at the LWRF but are slightly different across the three cores analyzed for this study (Fig. 2). Particularly LobataHead07 which is located far from the SGD seeps records higher δ15N values then the corals closer to the seeps. These different δ15N values represent differences in the δ15N signature of the dominant nutrient sources available to the corals at each location. Coral skeletal δ15N values of LobataHead07, which is located south of the primary seep site where nutrient levels are low (<0.1 μmol L−1 nitrate21) are ~+10‰, are likely influenced by the natural surface seawater nitrate value, which is slightly enriched in 15N relative to average deep ocean seawater due to nitrate assimilation (dissolved nitrate in seawater at that site measured in December 2013 was +8‰, Table 1). In contrast, coral δ15N values prior to 1995 for cores collected adjacent to the seep are lower than at the southern site, indicating exposure to one or more additional nutrient sources with lower δ15N values. At that time, the discharging water at the seeps contained N from a mixture of fresh groundwater and sewage-derived injection fluids that were not subject to denitrification at the treatment facility. This effluent-impacted groundwater is mixed to various degrees with local seawater prior to being incorporated into the coral. Hence the δ15N of these corals prior to 1995 (between ~+6‰ and +8‰) reflect the sewage-derived N source prior to implementation of denitrification at the LWRF operation, and hence less impacted by denitrification, and N in the local groundwater. The corals collected at the seep site do not represent the period of skeletal growth prior to LWRF operation (i.e. prior to 1975). Therefore, it is difficult to determine the relative contribution of inputs of sewage-effluent and those of groundwater or other sources (such as potential inputs from agricultural runoff containing fertilizer) to the δ15N of the corals prior to 1995. However, if we assume a value of 10‰ (as seen in LobataHead07) is representative of background conditions in the region at that time, then the sewage effluent must have contributed substantial amounts of N to reduce the signature by 2–4‰, although the exact contribution cannot be determined without knowing the isotopic signature of the effluent itself.

Cores collected adjacent to the seep display a variety of physical signs suggesting they have been exposed to multiple SGD-associated stressors (Table 1 and Fig. 3), including nitrate concentrations up to 50 times higher than ambient seawater, and lower pH bottom water21. For example, Prouty et al.21 found lower calcification rates and increased bioerosion in corals collected adjacent to the seeps; bioerosion rates were much higher than those observed in coral cores collected in the Pacific under equivalent low pH conditions but living in oligotrophic waters15. Bioerosion rate and percent bioerosion volume were significantly positively correlated (p ≤ 0.05) with the surrounding seawater nitrate concentration (Table 1) suggesting that eutrophication exacerbates ocean acidification and bioerosion of corals21.

Figure 3.

Coral core imagery. CT scan imagery of cores LobataHead04 and LobataHead06 (left), and X-Ray imagery of core LobataHead07 (right). The areas labeled in red represent the areas on the cores that were subsampled for δ15N analysis parallel to the coral growth axis, with a sample track width of ~0.5 cm on average.

Our results confirm that corals living within the SGD seep area are impacted by sewage-effluent injected at the LWRF. The fact that the δ15N signature of the corals collected from within the seep area increases dramatically within one year after the implementation of biological nutrient removal at the LWRF validates a direct link between wastewater injection and water quality on the reef, and is strong evidence that wastewater effluent, and its associated nutrient loads, is a dominant nutrient source to this location of the reef. More broadly, our results show that δ15N of coral intra-skeletal organic matter is useful for understanding changes in nutrient sources to coral reefs over time. Many of the most threatened reefs around the world are severely lacking in historic data that is crucial for making informed management decisions. The information provided by coral geochemical records as presented here can help close these important knowledge gaps and inform efforts to reduce nutrient transport to the nearshore environment.

Methods

Field Sampling

Coral cores from both alive and dead Porites lobata coral heads were collected in July of 2013 as part of an ongoing U.S. Geological Survey study aimed at quantifying the impact of SGD to the fringing refs.21,59. Coral cores from two shallow water (<5 m) locations in close vicinity to actively discharging seeps and another ~150 m to the south, away from active seeps, collected using a hand-held, air-powered pneumatic drill were used for this study. Cores are 50 mm in diameter, and range in length from 15 to 55 cm. In addition to the coral cores, samples of local seawater and discharging vent water were collected for nutrient and nitrate isotope analysis as reported in Prouty et al.21 and summarized in Table 1. Seawater samples were also collected and filtered for particulate organic matter (POM) in October 2013.

Coral Chronologies

Two of the coral cores from KBP used here were obtained from living Porites lobata coral heads (LobataHead04 and LobataHead07). This allowed for the development of chronologies based on visually counting the annual growth bands detected using X-ray and CT imaging, counting backwards from the date of collection (assuming each band represents one year). For the core collected from a dead specimen (LobataHead06), radiocarbon (14C) analysis was used to estimate the age of the coral (at the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, Woods Hole). 14C values were measured at five depths within the core and compared to bomb-derived 14C values previously measured in Hawaii, which determined that the coral died in approximately 200864. This established the age of the upper-most growth layer, with the rest of the chronology being developed by visually counting the annual growth bands in the X-ray imagery. Due to the relatively shallow slope of the recent radiocarbon bomb-curve, there is a relative uncertainty of several years for the age of the skeleton of LobataHead06. However, the agreement in the timing of the sharp increase in δ15N between LobataHead04 and LobataHead06 and their close physical proximity suggests that the chronology should be reasonably well constrained although small offsets of a few years are possible.

Coral Subsampling and Preparation

The coral cores were sliced in half along the major growth axis to ensure sampling along the major growth axis. Using the X-ray and CT images as a guide, annually resolved coral subsamples were collected by grinding down into the coral to a depth of approximately 3 mm, using a handheld Dremel tool, following the growth banding laterally, to produce ~100 mg of coral fine powder. The coral slabs were cleaned using a compressed air stream between each sample to avoid cross-contamination.

Isolation of Coral Intra-crystalline Organic Matter

In order to remove any external organic N that is subject to diagenesis and may not always preserve the original δ15N45, a bleach oxidation/extraction was employed, following part of the method described in Wang et al.65. Powdered coral samples were transferred into 10 mL acid-cleaned plastic centrifuge tubes with 5 mL of a 10 wt% NaClO bleach solution (10–15% available chlorine). Samples were then capped, shaken, and placed on an orbital shaker table for 24 hours. After 24 hours on the shaker table, samples were centrifuged, the solution was decanted, and the remaining powder was rinsed with 5 mL of deionized water. This rinse step was repeated 3 times before the samples were centrifuged, water decanted, and powder left to dry in an oven at 40 °C overnight. The cleaned powder samples were then stored inside a desiccator until isotope analysis of the intra-crystalline organic matter. The efficacy of this cleaning method was rigorously tested using an in-house carbonate standard material (described below) in order to ensure the efficient and effective removal of any external organic matter.

δ15N Isotopic Analysis – Nano-EA-IRMS

Due to the extremely low intra-crystalline organic N content in aragonitic corals, large amounts of coral skeletal material are necessary for isotope analysis. In order to reduce the amount of material required and allow for a sufficiently high temporal resolution, thereby increasing our ability to detect rapid changes, a modified Elemental Analyzer-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (EA-IRMS) “nanoEA” was developed following the work of Polissar et al.66. Due to the very high C:N ratio of bulk coral skeletal material, our modified design utilizes two cryogenic traps that separate N2 from CO2 and vent the CO2 to the atmosphere. The N2 gas is then concentrated by cryotrapping and transferred to the mass spectrometer. This allows for the introduction of a small, pure N2 sample to the mass spectrometer for determining both weight % N and δ15N. An advantage to this approach is that the procedure does not require the use of denitrifying bacteria for the production of sample gas, and therefore can be used at facilities that do not maintain such cultures.

Supplementary Fig. S1 (see Supplementary Information) shows a schematic diagram of the modified elemental analyzer and gas valve design that enables this separation technique. First, the samples are placed into a “zero-blank,” air-sealed autosampler that is purged with helium (He) carrier gas in order to eliminate any atmospheric N2 contamination. Next, the samples are dropped and combusted in a standard elemental analyzer that is in-line with the gas valve and IRMS system, with the combustion column at 1030 °C, the reduction column at 650 °C, and a He carrier gas flow pressure of 150 kPa. The CO2 and N2 gas that is produced in the EA then flows towards the two-way valve, and subsequently passes first through a CO2 trap, and then through an N2 trap. Each trap is submerged in liquid N2 and is designed to concentrate and separate the two gases from one another. We used a relatively large-diameter coiled gas line as the CO2 trap to accumulate the large volume of CO2 generated by these carbonate samples. The N2 trap consists of coiled molecular-sieve tubing that restricts the flow of N2 at liquid N2 temperatures, but will release the flow at higher temperatures. Once all of the sample gas has flowed from the EA and through the two traps, the position of the two-way value is changed, changing the source and direction of the gas flow through the traps and valve. The two traps are then raised in sequence, first allowing the sample N2 gas to flow back through the valve and towards the IRMS, and then allowing the collected CO2 to vent through the valve into the atmosphere. Rigorous testing of the valve, system timings, flow characteristics and IRMS settings using our in-house carbonate standard material (see below) was conducted to ensure that large quantities of carbonate are fully combusted, and that CO2 is completely separated from the N2 of interest, and that δ15N values obtained are accurate. Specifically, the trap and valve timings were optimized in order to ensure complete sample collection while minimizing the contribution of any background N2 in the system.

Unknown sample weights ranged between 60 and 80 mg of processed coral powder, depending on the % N content of the material, with the goal of introducing approximately 6 µg of N per sample. In order to monitor for system leaks and any potential reduction in combustion efficiency or sample carryover, all samples and standards were bracketed by blanks during each run. An internal consistency standard consisting of homogenized coral skeleton material was produced early on in the method development process. This material was used to assess the efficacy of the bleach cleaning as well as the efficiency of the carbonate combustion described above, but it was also used as an in-run and between-run internal standard. Numerous samples of this material were analyzed interspersed throughout each instrument run in order to monitor and correct for instrument drift, and in order to better compare sample results from run to run. While this material has not been independently standardized using a separate analytical method, we have run the material hundreds of times during method development, validation and sample analysis, and use the consistency of the measured value in order to evaluate the accuracy and stability of the analytical method. The across-run average δ15N value of this material as measured during the analysis of these corals was + 5.79‰ ± 0.31‰ (n = 25, see Supplementary Fig. S2 in Supplementary Materials) based on calibration using certified standards (see below), with typical intra-run precision below 0.5‰.

All data were corrected for both size and isotopic value using a suite of three independently calibrated, homogenized internal lab standards (EDTA, δ15N = 0.72‰; spirulina, δ15N = 10.88‰; fish fertilizer, δ15N = 16.24‰) as well as one calibrated international isotope standard (IAEA-N-2, δ15N = 20.3‰). Due to the very small amount of N being introduced to the mass spectrometer for each sample, accurately characterizing and correcting for the contribution of the blank is extremely important. In order to do this, we run a size range series of each of the above organic standard materials during each instrument run, generally ranging from 2 µg to 8 µg of N. The measured relationship between peak area and sample weight is used to calculate the mass of N present in each sample. Finally, the measured non-linear relationship between standard size and isotopic value is used to do a two-point isotope value calibration for each unknown sample. δ15N precision for replicate sample analysis is approximately 0.4‰ based on sample replicates, as well as repeated internal consistency standard coral analyses. The approximate size of the instrument blank, as calculated following Polissar et al.66, typically ranged from 500 to 900 ng N. The size and isotopic value of the blank was somewhat variable run-to-run, however this was rigorously characterized using the above analysis scheme during each individual run and was typically stable within a run after purging the autosampler.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out as part of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Coral Reefs Project in an effort to better understand the effects of geologic and oceanographic processes on coral reef systems in the USA and its trust territories, and was supported by the USGS Coastal and Marine Geology Program and a grant from NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program (NA15NOS4820079) and the Ocean Science and Technology Packard Endowment to AP and NP. We thank P. Dal Ferro, J. Logan, T. Reiss, C. Storlazzi, and N. Smiley (USGS), J. McClaren (Stanford), D. White (DAR), M. Dailer (U. Hawaii), and C. Gallagher (UCSC) for field assistance. We also thank C. Kendall and S. R. Silva (USGS) for instrumentation access and technical support, as well as D. Andreasen and C. Carney (UCSC) for advice and guidance in method development. Finally, we thank A. Andrews (NOAA), K. Rose, and A. Cohen (WHOI) for assistance with coral scans and chronology development. The use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author Contributions

J.M., A.P. and N.P. designed the project, J.M. wrote the main manuscript, with significant input from N.P. and A.P. Coral and POM samples provided by N.P. S.P. was the primary resource during method development and sample analysis and helped with the methods section. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-42013-3.

References

- 1.Harborne AR, Rodgers A, Bozec Y, Mumby P. Multiple stressors and the functioning of coral reefs. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2017;9:445–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ban SS, Graham NAJ, Connolly SR. Evidence for multiple stressor interactions and effects on coral reefs. Global Change Biol. 2014;20:681–697. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabricius KE. Effects of terrestrial runoff on the ecology of corals and coral reefs: review and synthesis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005;50:125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paytan A, et al. Submarine groundwater discharge: an important source of new inorganic nitrogen to coral reef ecosystems. Limn. & Ocean. 2006;51:343–348. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.1.0343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Street JH, Knee KL, Grossman EE, Paytan A. Submarine groundwater discharge and nutrient addition to the coastal zone and coral reefs of leeward Hawai’i. Mar. Chem. 2008;109:355–376. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2007.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heery EC, et al. Urban coral reefs: Degradation and resilience of hard coral assemblages in coastal cities of East and Southeast Asia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;135:654–681. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M., & Perry, A. Reefs at risk. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC, 124 (2011).

- 8.Anderson DM, Glibert PM, Burkholder JM. Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: nutrient sources, composition, and consequences. Estuaries. 2002;25:704–726. doi: 10.1007/BF02804901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duprey NN, Yasuhara M, Baker DM. Reefs of tomorrow: eutrophication reduces coral biodiversity in an urbanized seascape. Global Change Biol. 2016;22:3550–3565. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lapointe BE, Barile PJ, Littler MM, Littler DS. Macroalgal blooms on southeast Florida coral reefs: II. Cross-shelf discrimination of nitrogen sources indicates widespread assimilation of sewage nitrogen. Harmful Algae. 2005;4:1106–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2005.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howarth RW. Coastal nitrogen pollution: a review of sources and trends globally and regionally. Harmful Algae. 2008;8:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes TP, et al. Phase shifts, herbivory, and the resilience of coral reefs to climate change. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruno JF, Petes LE, Drew Harvell C, Hettinger A. Nutrient enrichment can increase the severity of coral diseases. Ecol. Lett. 2003;6:1056–1061. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00544.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redding JE, et al. Link between sewage-derived nitrogen pollution and coral disease severity in Guam. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2013;73:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeCarlo TM, et al. Coral macrobioerosion is accelerated by ocean acidification and nutrients. Geology. 2015;43:7–10. doi: 10.1130/G36147.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamazaki A, Watanabe T, Tsunogai U, Hasegawa H, Yamano H. The coral δ15N record of terrestrial nitrate loading varies with river catchment land use. Coral Reefs. 2015;34:353–362. doi: 10.1007/s00338-014-1235-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duprey NN, et al. Life and death of a sewage treatment plant recorded in a coral skeleton δ15N record. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2017;120:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marion GS, et al. Coral skeletal δ15N reveals isotopic traces of an agricultural revolution. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2005;50:931–944. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muscatine L, et al. Stable isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) of organic matrix from coral skeleton. PNAS. 2005;102:1525–1530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408921102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall, C., Elliott, E. M. & Wankel, S. D. Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science Ch. 12 (Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA, 2007).

- 21.Prouty, N. G., Yates, K. K., Smiley, N. A. & Gallagher, C. Coral growth parameters and seawater chemistry, Kahekili, west Maui: U.S. Geological Survey data release, 10.5066/F7X34VPV (2017).

- 22.Heaton THE. Isotopic studies of nitrogen pollution in the hydrosphere and atmosphere: a review. Chem. Geol. 1986;59:87–102. doi: 10.1016/0168-9622(86)90059-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owens NJP. Natural variations in 15N in the environment. Adv. Mar. Biol. 1987;24:390–451. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigman DM, Altabet MA, McCorkle DC, Francois R, Fischer G. The δ15N of nitrate in the Southern Ocean: nitrogen cycling and circulation in the ocean interior. J. Geophys Res. 2000;105:19599–19614. doi: 10.1029/2000JC000265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigman, D. M. & Casciotti, K. L. Nitrogen Isotopes in the ocean. Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Academic Press, London) 1884–1894 (2001).

- 26.Burg A, Heaton TH. The relationship between the nitrate concentration and hydrology of a small chalk spring; Israel. J. Hydrol. 1998;204:68–82. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1694(97)00105-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindau CW, Delaune RD, Alford DP. Monitoring nitrogen pollution from sugarcane runoff using15N analysis. Water Air Soil Poll. 1997;98:389–399. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wankel SD, Kendall C, Paytan A. Using nitrate dual isotopic composition (δ15N and δ18O) as a tool for exploring sources and cycling of nitrate in an estuarine system: Elkhorn Slough, California. J. Geophys. Res-Biogeo. 2009;114:2005–2012. doi: 10.1029/2008JG000729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wankel SD, Mosier AC, Hansel CM, Paytan A, Francis CA. Spatial variability in nitrification rates and ammonia-oxidizing microbial communities in the agriculturally impacted Elkhorn Slough estuary, California. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2011;77:269–280. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01318-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordan MJ, Nadelhoffer KJ, Fry B. Nitrogen cycling in forest and grass ecosystems irrigated with 15N-enriched wastewater. Ecol. Appl. 1997;7:864–881. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voss M, Larsen B, Leivuori M, Vallius H. Eutrophication signals in coastal Baltic Sea sediments. J. Marine Syst. (Special Issue) 2000;25:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabana G, Rasmussen JB. Comparison of aquatic food chains using nitrogen isotopes. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996;93:10844–10847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Risk MJ, Erdmann MV. Isotopic composition of nitrogen in stomatopod (Crustacea) tissues as an indicator of human sewage impacts on Indonesian coral reefs. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2000;40:50–58. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00150-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derse E, et al. Identifying sources of nitrogen to Hanalei Bay, Kauai, utilizing the nitrogen isotope signature of macroalgae. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2007;41:5217–5223. doi: 10.1021/es0700449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dailer ML, Knox RS, Smith JE, Napier M, Smith CM. Using δ15N values in algal tissue to map locations and potential sources of anthropogenic nutrient inputs on the island of Maui, Hawaii, USA. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2010;60:655–671. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Dover CL, Grasslei JF, Fryili B. Stable isotope evidence for entry of sewage-derived organic material into a deep-sea food web. Nature. 1992;360:12. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heikoop JM, et al. Nitrogen-15 signals of anthropogenic nutrient loading in reef corals. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2000;40:628–636. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erler DV, Wang XT, Sigman DM, Scheffers SR, Shepherd BO. Controls on the nitrogen isotopic composition of shallow water corals across a tropical reef flat transect. Coral Reefs. 2014;34:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s00338-014-1215-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Risk MJ, Lapointe BE, Sherwood OA, Bedford BJ. The use of δ15N in assessing sewage stress on coral reefs. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2009;58:793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamazaki A, et al. Seasonal variations in the nitrogen isotope composition of Okinotori coral in the tropical western Pacific: A new proxy for marine nitrate dynamics. J. Geophys. Res-Biogeo. 2011;116:2005–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamazaki A, Watanabe T, Tsunogai U. Nitrogen isotopes of organic nitrogen in reef coral skeletons as a proxy of tropical nutrient dynamics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011;38:L19605. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamazaki A, Watanabe T, Takahata N, Sano Y, Tsunogai U. Nitrogen isotopes in intra-crystal coralline aragonites. Chem. Geol. 2013;351:276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang XT, et al. Influence of open ocean nitrogen supply on the skeletal δ15N of modern shallow-water scleractinian corals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2016;441:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren H, et al. 21st-century rise in anthropogenic nitrogen deposition on a remote coral reef. Science. 2017;356:749–752. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ingalls AE, Lee C, Druffel ER. Preservation of organic matter in mound-forming coral skeletons. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 2003;67:2827–2841. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00079-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ross, M. et al. Characterization of dead zones and population demography of Porites compressa along a gradient of anthropogenic nutrient input at Kahekili Beach Park, Maui. Final Report for Project C11722. State of Hawaii, Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Aquatic Resources, Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 (2012).

- 47.Wiltse, W. Algal Blooms: Progress Report on Scientific Research. West Maui Watershed Management Project (1996).

- 48.Sparks, R.T., Stone, K., White, D.J., Ross, M., & Williams, I.D. Maui and Lanai Monitoring Report. Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Aquatic Resources, Maui, 130 Mahalani Street, Wailuku HI. 96790 (2016).

- 49.Smith JE, Runcie JW, Smith CM. Characterization of a large-scale ephemeral bloom of the green alga Cladophora sericea on the coral reefs of West Maui, Hawai’i. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2005;302:77–91. doi: 10.3354/meps302077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunt, C. D. & Rosa, S. N. A Multitracer approach to detecting wastewater plumes from municipal injection wells in nearshore marine waters at Kihei and Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5253 (2009).

- 51.Dailer ML, Ramey HL, Saephan S, Smith CM. Algal δ15N values detect a wastewater effluent plume in nearshore and offshore surface waters and three-dimensionally model the plume across a coral reef on Maui, Hawai’i, USA. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2012;64:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swarzenski P, et al. Observations of nearshore groundwater discharge: Kahekili Beach Park submarine springs, Maui, Hawaii. J. Hydrol: Reg. Stud. 2016;11:147–165. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glenn, C. R. et al. Lahaina groundwater tracer study—Lahaina, Maui, Hawai’i, Final Interim Report, prepared for the State of Hawaii Department of Health, the US Environmental Protection Agency, and the US Army Engineer Research and Development Center (2012).

- 54.Glenn, C.R. et al. Lahaina groundwater tracer study - Lahaina, Maui, Hawai’i. Final Report, prepared for the State of Hawaii Department of Health, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the USArmy Engineer Research and Development Center. (2013).

- 55.Engott, J. A. & Vana, T. T. Effects of agricultural land-use changes and rainfall on ground-water recharge in Central and West Maui, Hawai’i, 1926–2004. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2007–5103 (2007).

- 56.Gingerich, S. B. & Engott, J. A. Groundwater availability in the Lahaina District, West Maui, Hawai’i. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2012–010 (2012).

- 57.Tetra Tech, Inc. Effluent fate study, Lahaina Wastewater Reclamation Facility, Maui, Hawai’i. Prepared for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 9 (1994).

- 58.Fackrell JK, Glenn CR, Popp BN, Whittier RB, Dulai H. Wastewater injection, aquifer biogeochemical reactions, and resultant groundwater N fluxes to coastal waters: Kā'anapali, Maui, Hawai’i. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2016;110:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prouty NG, et al. Carbonate system parameters of an algal-dominated reef along West Maui. Biogeosciences. 2018;15:2467–2480. doi: 10.5194/bg-15-2467-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naumann MS, et al. Organic matter release by dominant hermatypic corals of the Northern Red Sea. Coral Reefs. 2010;29:649–659. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0612-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levas, S. et al. Can heterotrophic uptake of dissolved organic carbon and zooplankton mitigate carbon budget deficits in annually bleached corals? Coral Reefs35, 495–506.

- 62.Knee KL, Street JH, Grossman EE, Boehm AB, Paytan A. Nutrient inputs to the coastal ocean from submarine groundwater discharge in a groundwater-dominated system: Relation to land use (Kona coast, Hawaii, USA) Limn. & Ocean. 2010;55:1105–1122. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.3.1105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blackburn-Rodriguez, T. Economist Paul Brewbaker: Maui’s economic expansion has begun. Lahaina Newshttp://www.lahainanews.com/page/content.detail/id/501095/Economist-Paul-Brewbaker–Maui-s-economic-expansion-has-begun.html? (2010).

- 64.Andrews AH, Siciliano D, Potts DC, DeMartini EE, Covarrubias S. Bomb radiocarbon and the Hawaiian Archipelago: coral, otoliths, and seawater. Radiocarbon. 2016;58:531–548. doi: 10.1017/RDC.2016.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang XT, et al. Isotopic composition of carbonate-bound organic nitrogen in deep-sea scleractinian corals: A new window into past biogeochemical change. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014;400:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Polissar PJ, Fulton JM, Junium CK, Turich CC, Freeman KH. Measurement of 13C and 15N isotopic composition on nanomolar quantities of C and N. Anal. Chem. 2008;81:755–763. doi: 10.1021/ac801370c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.