Abstract

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder causing endocrine, musculoskeletal, and neurological dysfunction. PWS is caused by the inactivation of contiguous genes, complicating the development of targeted therapeutics. Clinical trials are now underway in PWS, with more trials to be implemented in the next few years. PWS-like endophenotypes are recapitulated in gene-targeted mice in which the function of one or more PWS genes is disrupted. These animal models can guide priorities for clinical trials or provide information about efficacy of a compound within the context of the specific disease. We now review the current status of preclinical studies that measure the effect of therapeutics on PWS-like endophenotypes. Seven categories of therapeutics (oxytocin and related compounds, K+-ATP channel agonists, melanocortin 4 receptor agonists, incretin mimetics and/or GLP-1 receptor agonists, cannabinoids, ghrelin agents, and Caralluma fimbriata [cactus] extract) have been tested for their effect on endophenotypes in both PWS animal models and clinical trials. Many other therapeutics have been tested in clinical trials, but not preclinical models of PWS or vice versa. Fostering dialogs among investigators performing preclinical validation of animal models and those implementing clinical studies will accelerate the discovery and translation of therapies into clinical practice in PWS.

Keywords: Prader-Willi syndrome, preclinical studies, mouse models of disease, oxytocin, diazoxide, growth hormone, melanocortin, cannabinoid

Main Text

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by loss of expression of paternally expressed, imprinted genes on chromosome 15q11-q13.1, 2 Infants with PWS typically exhibit hypotonia and developmental delay, while older children and adults have intellectual impairment with behavioral abnormalities and neuropsychiatric symptoms, endocrine dysfunction with growth hormone deficiency, unrelenting hunger (hyperphagia) that can lead to obesity, and musculoskeletal and neurological abnormalities. Until recently, pharmacological treatments for PWS were limited to symptomatic therapies, such as hormone replacement therapy and psychiatric medications.1 Behavioral and physical therapies also improve outcomes in people with PWS. However, there are no pharmacological therapies approved to treat symptoms that most affect daily activities including hyperphagia and emotional reactivity.

The number of clinical studies and trials testing therapeutics (compounds or procedures) to prevent or treat PWS symptoms has increased in recent years. To be used in clinical studies, these therapeutics have met minimum standards for safety in the general population but have not necessarily been tested for safety or efficacy in the PWS population. Animal models can be used to guide decision making about priorities for clinical trials and can provide information about potential efficacy of a compound within the context of a specific genetic disease background. Two reviews in 2013 summarized how mice carrying targeted mutations in PWS genes recapitulate many core phenotypes of PWS.3, 4 At that time, only two original research studies had attempted to rescue endophenotypes in mouse models of PWS. Both studies examined bioactive peptides, testing responses to either oxytocin5 or melanotan II6 in gene-targeted mice (Table 1). From 2014 to 2018, 15 additional studies used gene-targeted mouse lines to test the effects of pharmacological agents, surgical procedures, and environmental temperature on various phenotypes (Table 1). Here, we summarize how animal models contribute to progress toward effective therapeutics for PWS. We discuss obstacles to treatment in PWS that are typical of rare disorders, such as recapitulation of phenotypes in preclinical models. Finally, we discuss how careful design and reporting of preclinical studies can stimulate progress of therapeutics for PWS.

Table 1.

Interventional Trials in Mouse Models of PWS

| Strain | Treatment | Treatment Administration | Note | Outcome | Group Size (M/F) | Age | Reference | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magel2tm1.1Mus | oxytocin | i.p. single injection, 2 μg | a | survival | n = 33–51, M and F | 3–5 h | 5 | A single postnatal injection of oxytocin rescues the lethal feeding behavior in mouse newborns deficient for the imprinted Magel2 gene |

| Magel2tm1.1Mus | oxytocin | i.p. daily, 7 days, 2 μg | b | survival, social behavior | n = 12–14, M | 0–6 d, test adult | 29 | An early postnatal oxytocin treatment prevents social and learning deficits in adult mice deficient for Magel2, a gene involved in PWS and autism |

| Magel2tm1.1Mus | oxytocin | i.p. single injection, 2 μg | c | social recognition deficits | n = 12–14, M | adult | 29 | An early postnatal oxytocin treatment prevents social and learning deficits in adult mice deficient for Magel2, a gene involved in PWS and autism |

| Magel2tm1Stw | MT-II | i.p. single injection, 2.5 mg/kg | d | 24 h food intake | n = 6, M | 3–4 months | 6 | Magel2 is required for leptin-mediated depolarization of POMC neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus in mice |

| Magel2tm1Stw | setmelanotide | i.p. single injection (0.04, 0.1, 0.2 or 1 mg/kg) | e | food intake, EE, RER | n = 6, M | 2–3 months | 34 | Magel2-null mice are hyper-responsive to setmelanotide, a melanocortin 4 receptor agonist |

| Magel2tm1Stw | sleeve gastrectomy | surgery | f | weight, food intake, fat/lean mass, fasting glucose, glucose tolerance, counter-regulation | n = 7–12, M | 5–7 months, HFD | 35 | Sleeve gastrectomy leads to weight loss in the Magel2 knockout mouse |

| Magel2tm1Stw | JD5037 or SLV319 | i.p. daily 28 d, 3 mg/kg | g | weight, food intake, body comp, activity, metabolism | n = 5–10, M and F | 3–4 months, HFD or STD | 36 | Targeting the endocannabinoid and CB1 receptor system for treating obesity in PWS |

| Magel2tm1Stw | OEA | i.p. single injection,10 mg/kg | h | 24 h food intake | n = 14–15, M | adult | 39 | Dysfunctional oleoylethanolamide signaling in a mouse model of PWS |

| Magel2tm1Stw | diazoxide | ground into food, 150 mg/kg/day, 6 weeks | i | weight, body composition, activity, fasting glucose | n = 6, M and F | 5–7 months, HFD | 38 | Chronic diazoxide treatment decreases fat mass and improves endurance capacity in an obese mouse model of PWS |

| Magel2tm1Stw | oleoyl a-methyl serine (HU-671) | once daily, 0.5 mg/kg, 6 weeks | j | structural analysis of the trabecular and cortical bones | n = 4–11, F | 6–12 weeks | 37 | Magel2 modulates bone remodeling and mass in Prader-Willi syndrome by affecting oleoyl serine levels and activity |

| Ndntm1.1Mus | fluoxetine | 10 mg/kg/day from P5–P15 | k | plethysmography (% with apnea, apnea/h, apnea duration) | n = 8, M and F | 5–15 d, measure 0, 15, 45 days later | 71 | Necdin shapes serotonergic development and SERT activity modulating breathing in a mouse model for PWS |

| Snord116tm1.1Uta | [D-Lys3]-GHRP6 | i.p. daily, 12 μmol/kg, 6 days | l | food intake | n = 7–9, M | 6–12 months | 113 | Abnormal response to the anorexic effect of GHS-R inhibitors and exenatide in male Snord116 deletion mouse model for PWS |

| Snord116tm1.1Uta | SPA | i.p. daily, 4.5 μmol/kg, 6 days | m | food intake | n = 8, M | 6–12 months | 113 | Abnormal response to the anorexic effect of GHS-R inhibitors and exenatide in male Snord116 deletion mouse model for PWS |

| Snord116tm1.1Uta | YIL-781 | i.p. daily, 134 μmol/kg, 6 days | n | food intake | n = 9–10, M | 6–12 months | 113 | Abnormal response to the anorexic effect of GHS-R inhibitors and exenatide in male Snord116 deletion mouse model for PWS |

| Snord116tm1.1Uta | exenatide | i.p. twice daily, 24 μg/kg, 17 days | o | food intake | n = 7–9, M | 6–12 months | 113 | Abnormal response to the anorexic effect of GHS-R inhibitors and exenatide in male Snord116 deletion mouse model for PWS |

| Snord116tm1.1Uta | GHSR agonist HM01 | s.c. daily, 30 μg/g, 14 days | p | body weight, length, mortality | n = 9–17, M and F | 1–14 days | 114 | Ghrelin receptor agonist rescues excess neonatal mortality in a Prader-Willi syndrome mouse model |

| Snord116tm1.1Uta | Carraluma fimbriata extract | orally in gel, 33 or 100 mg/kg/day, 10 weeks | q | food intake after stimulation | n = 6, M and F | 4–15 weeks | 165 | Caralluma fimbriata extract activity involves the 5-HT2c receptor in PWS Snord116 deletion mouse model |

| Snord116tm1.1Uta | thermoneutral (30°C) | 16 weeks | r | body weight, body comp, length, BMD, energy intake | n = 9–14, M | from 4 to 20 weeks | 106 | Ambient temperature modulates the effects of the PWS candidate gene Snord116 on energy homeostasis |

| Snrpntm2Cbr (PWS-ICdel) | thermoneutral (30°C) | 9 weeks | s | food intake, fat mass, weight gain | n = 5–6, M and F | 6–15 months | 118 | Paradoxical leanness in the imprinting-center deletion mouse model for PWS |

| Snrpntm2Cbr (PWS-ICdel) | WAY-161503 | s.c. single injection, 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg | t | postfast refeeding | n = 12–14, M and F | adult | 122 | Increased alternate splicing of Htr2c in a mouse model for Prader-Willi syndrome leads disruption of 5HT2C receptor mediated appetite |

| Del(7Ube3a-Snrpn)1Alb | UNC0642 | i.p. daily P7–P12, 2.5 mg/kg | u | % survival, body weight | n = 6–27, M and F | 7–90 days | 123 | Targeting the histone methyltransferase G9a activates imprinted genes and improves survival of a mouse model of PWS |

i.p., intraperitoneal; s.c., subcutaneous; EE, energy expenditure; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; HFD, high-fat diet; SD, standard diet; BMD, bone mineral density; P, postnatal day.

Rescued the death rate of Magel2 mice with a single injection of oxytocin 3–5 h after birth.

Daily oxyocin injections in the first 7 postnatal days increased survival and prevented social and learning deficits in Magel2 adult male mice.

Reversed social recognition deficits in Magel2 mice despite a temporary sedative effect.

Reduced food intake in Magel2 mice, compared to vehicle. This effect was still evident 24 h after injection. Lesser extent of reduced food intake for the first 2 h of refeeding in control mice. This effect was no longer present by 4 h.

Reduced food intake, increased energy expenditure, and increased activity in WT and Magel2 mice compared to vehicle. Magel2 mice responded at lower dosages of setmelanotide.

Similar weight loss in both Magel2 and WT mice by specifically causing loss of fat but not lean mass. Lowered fasting glucose and improved glucose tolerance in both WT and Magel2 mice.

Reversed obesity, reduced hyperphagia, increased total energy expenditure and voluntary activity, food intake and carbohydrate intake, and improved metabolic outcomes in obese Magel2 mice.

Reduced food intake in Magel2 mice, compared to vehicle. Effect attributed to decreased meal size and accompanying increase in satiety ratio (postmeal interval/meal size).

Decreased fat mass, increased percent lean mass, and eliminated hyperglycemia in male and female diet-induced obese mice. Both WT and Magel2 had improved endurance.

Restored bone density and bone mass, decreased bone resorption, and increased bone formation.

Daily fluoxetine treatment of Ndn pups from P5–P15 suppressed their respiratory deficits.

No suppression of food intake in WT or Snord116 mice.

No suppression of food intake in WT or Snord116 mice.

Reduced food intake only on day 1 in WT and Snord116 mice.

Food intakes for WT and Snord116 mice were reduced to ∼84%.

GHSR, growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Reduced body weight and length in male Snord116 pups, reduced mortality in Snord116 pups.

Differences between strains in 4-h food intake after stimulation of appetite with agents. Sexes not separately analyzed.

Normalized low BMD and BMC, high energy expenditure and low physical activity, but not low body weight, in Snord116 mice.

Increased BAT mass in WT and ICdel males but failed to induce a corresponding elevation in WAT mass. Proportionate hyperphagia in ICdel males abolished at thermoneutrality.

Reduced food consumption in WT but not PWS-ICdel mice compared to vehicle.

Improved survival and increased growth of Del(7Ube3a-Snrpn)1Alb neonatal mice, 2/60 survived to P90.

The Multigene Nature of PWS

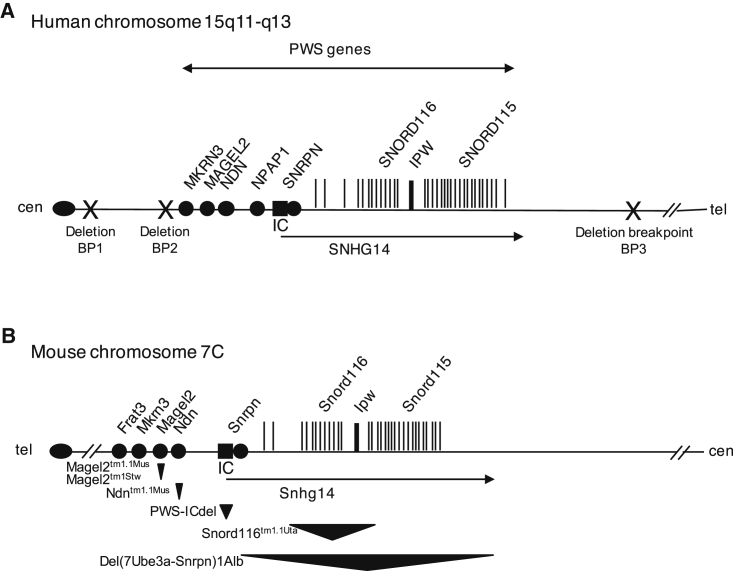

The majority of cases of PWS are caused either by a sporadic deletion of a set of genes on the paternally inherited copy of chromosome 15q11-q13 or by maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15 (Figure 1). A minority of cases are caused by sporadic or inherited mutations within an embedded regulatory region called the imprinting center (IC).2 The PWS region contains protein-coding genes and non-coding RNAs and genetic elements that coordinate gene expression and imprinting. Like some other microdeletion disorders, individual genes within the deleted region are implicated in specific endophenotypes, but disruption of several genes is required to elicit the full phenotype. All but one (NPAP1) of the PWS protein-coding genes are conserved in other mammals, while the non-coding elements vary in the extent of their sequence and functional conservation (Figure 1). The genetic complexity of the deleted region complicates the development of animal models of PWS. It is thus useful to describe the individual genes whose expression is absent in PWS, evaluate the possible contribution of each gene to endophenotypes in PWS, and describe preclinical studies in mice carrying mutations targeting these genes.

Figure 1.

Genes Implicated in Prader-Willi Syndrome

(A) Paternally expressed, imprinted genes located within the PWS deletion region are indicated on a genomic map of human chromosome 15q11-q13. Protein coding genes and non-coding RNAs are indicated as circles and vertical lines, respectively. Common breakpoints (BP; X) are found in cases of PWS by deletion of 15q11-q13. (B) The mouse chromosome 7C region has conserved synteny with the human PWS region with a few exceptions: mice do not have a homolog of human NPAP1, and Frat3 occurs exclusively in rodents. The six PWS mouse models in which interventional studies have been performed are indicated below the genomic map, with the approximated location and size of the gene-targeted deletions indicated by triangles. cen, centromere; IC, imprinting center (black box); tel, telomere.

MAGEL2

MAGEL2 (melanoma antigen gene L2) encodes a member of the melanoma antigen (MAGE) protein family.7, 8, 9 MAGE proteins are defined by a conserved 171-amino-acid domain (MAGE homology domain [MHD]) that interacts with other proteins. MAGEL2 is expressed primarily in the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that controls appetite, endocrine function, and homeostatic functions. MAGEL2 is also expressed in the peripheral nervous system, developing muscle, cartilage, and bone.10, 11, 12 MAGEL2 is predicted to encode a 1249-amino-acid protein, although endogenous MAGEL2 protein has not yet been detected in tissues. One of the cellular roles of MAGEL2 is as an adaptor protein for E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases.9, 12, 13, 14 For example, MAGEL2 interacts with TRIM27 and USP7 to control the activity of the WASH complex, mediating endosomal actin assembly and protein recycling.12, 13 MAGEL2 also facilitates trafficking of cell-surface receptors,13 including regulation of leptin receptors through interactions with the E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF41 and the deubiquitinase USP8.14, 15

Consistent with the idea that loss of MAGEL2 function plays a major role in the PWS phenotype, de novo or inherited protein truncating mutations in MAGEL2 alone cause Schaaf-Yang syndrome (SHFYNG; OMIM: 615547).16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Phenotypes in people with Schaaf-Yang syndrome overlap considerably with PWS phenotypes, including hypotonia, endocrine dysfunction, hypogonadism, developmental delay, intellectual disability with autism spectrum disorder, and maladaptive behavior.25, 26

Mouse Models of Magel2 Deficiency

Two mouse models of Magel2 deficiency have been developed.3 The Magel2tm1Stw mouse line carries a lacZ insertion that replaces the C-terminal domain of the Magel2 open reading frame, including the MHD (JAX stock: 00906211, 27). The Magel2tm1.1Mus line carries a deletion of the Magel2 promoter and most of the open reading frame.5 Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice have physiological abnormalities including disintegration of circadian rhythm in constant lighting conditions, infertility, reduced strength and locomotor activity, increased fat mass with decreased muscle mass, abnormal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function, reduced counter-regulatory response to hypoglycemia, reduced levels of Igf1 and thyroid hormones, abnormal brain structure, abnormal levels of dopamine and serotonin pathway compounds in brain tissues, and abnormal behavior.3, 4 Consistent with their excess fat mass, adult Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice are insensitive to the anorexigenic effects of injected leptin hormone.6 Moreover, their hypothalamic POMC neurons do not depolarize in response to leptin.6 Magel2tm1.1Mus mutant mice demonstrated suckling defects causing slow growth or lethality in pups.5

Since 2012, additional phenotypes have been uncovered in Magel2 mutant mice. Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice spent more time in the open arm of an elevated plus maze compared to wild-type (WT) littermates, suggesting reduced anxiety, and had a lack of preference for social novelty.28 Magel2tm1.1Mus male mutant mice exhibit deficits in social recognition and social interaction and reduced ability to learn.29 Sleep deficits in Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice have also been reported.30 While adult Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice demonstrate physiological leptin resistance, younger Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice are leptin sensitive.15 Consistent with this phenotype, a progressive postnatal decline in leptin sensitivity was detected in POMC neurons in live tissue slices of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus.15 Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice exhibit impaired development and function of hypothalamic anorexigenic circuits.31, 32 As well, Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice demonstrate dopamine pathway imbalances33 and histological and functional muscle impairment, including a progressive reduction in limb strength and endurance with age.10 Tissues from Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice contain an increased number of p62 aggregates in skeletal muscle and reduced proportion of p62-positive POMC-expressing neurons in the arcuate nucleus.10 This suggests abnormal autophagy is occurring in skeletal muscle and in the brain. Abnormal levels of proteins important for recycling of the leptin receptor were found in brain tissues from Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice,14 consistent with a role for MAGEL2 in membrane protein recycling.9 There is compelling evidence that inactivation of MAGEL2 is the major cause of endocrine, musculoskeletal, and neurological dysfunction in PWS. The high expression of MAGEL2 in the parts of the nervous system that are dysfunctional in PWS, the importance of MAGEL2 protein function in the neurological, endocrine and musculoskeletal systems, and the striking similarities between phenotypes in Magel2 mutant mice and individuals in PWS all support the hypothesis that loss of MAGEL2 makes a major contribution to PWS.

Interventional Studies in Magel2 Mutant Mice

Nine studies have examined the effect of therapeutic interventions in Magel2 mutant mice (Table 1). A postnatal injection of oxytocin improved survival of Magel2tm1.1Mus mutant mice, which otherwise have an early postnatal mortality rate of about 50%.5 In a follow-up study, early postnatal treatment of Magel2tm1.1Mus mutant mice with oxytocin prevented the social and learning deficits that adult Magel2tm1.1Mus mutant mice would otherwise display.29 Administration of MT-II, a melanocortin 4 receptor agonist, decreased food intake in Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice to a greater extent than in WT controls.6 In a follow-up study, Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice were hyper-responsive to setmelanotide, a newer melanocortin 4 receptor agonist, with a greater reduction in food intake after a single dose compared to WT.34 Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice responded to bariatric surgery (sleeve gastrectomy) with loss of fat mass and improved metabolic parameters.35 Administration of JD5037, which targets the endocannabinoid and CB1 receptor system, reduced fat mass in Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice.36 Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice suffer from a low-bone-mass phenotype, but KAL671 (oleoyl α-methyl serine), an endocannabinoid-like compound, prevented trabecular bone loss in these mice.37 Magel2tm1Stw mutant mice have high fat mass and reduced endurance,10 phenotypes that were ameliorated by chronic diazoxide treatment.38 Magel2tm1Stw mice have dysfunctional oleoylethanolamide signaling, and intraperitoneal administration of oleoylethanolamide significantly reduced food intake on fasting and refeeding.39 Overall, these results suggest that Magel2 mutant mice recapitulate many of the phenotypes of both Schaaf-Yang syndrome and PWS and are an excellent model for preclinical testing of therapeutics destined for clinical trials in these disorders.

NDN

NDN (neurally differentiated embryonal carcinoma-derived protein) encodes necdin, which is another member of the MAGE protein family containing a C-terminal MHD. Necdin was first described as a protein that is highly expressed in neurally differentiated embryonal carcinoma cells.40 Necdin interacts with a variety of proteins and plays roles in transcription, cell cycle entry, and cell-surface receptor signaling. In one study, a de novo NDN variant (p.Ala280Pro) was found in a patient with Smith-Magenis-like syndrome.41, 42 It is unclear whether this variant is pathogenic on its own or in combination with a de novo variant in MAPK8IP3 identified in the same individual.

Mouse Models of Ndn Deficiency

Four lines of mice carrying loss-of-function mutations in Ndn have been described: Ndntm1.1Mus,43 Ndntm1Alb,44 Ndntm1Ky (repository RBRC0231645), and Ndntm2Stw (JAX stock: 00908946).3 All four lines carry deletions within the coding region, and the promoter is also deleted in one of the lines (Ndntm1.1Mus 5). Prior to 2012, phenotypes described in Ndn mutant mice that recapitulate findings in PWS include severe neonatal respiratory compromise, behavioral abnormalities, abnormalities of central, autonomic, and peripheral nervous system development and function, enlarged brain ventricles, and abnormal development of limb musculature.43, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62 Necdin regulates preadipocyte proliferation in developing adipose tissues, and Ndntm1Ky become obese with adipocyte hyperplasia when fed a high-fat diet.63, 64 Embryonic fibroblasts, cortical neurons, and muscle progenitor cells from Ndntm2Stw mutant mice, as well as human PWS fibroblasts, displayed impaired myosin activation and polarization.49, 60 Interestingly, necdin is important for normal hematopoiesis, although hematopoietic defects are not described in PWS.65, 66 A last line of mice (tgMlcNec) overexpressed necdin only in skeletal myoblasts and skeletal muscle and were used to show that necdin expression is important for a protective response of the muscle against tumor-induced wasting, inhibition of myogenic differentiation, and fiber regeneration in mice with cachexia.53, 67 Necdin also modulates osteogenic cell differentiation by regulating two other genes, Dlx5 and Maged1.68

In the last five years, studies of mice carrying Ndn mutations have confirmed that necdin is an essential protein for physiological processes relevant to PWS phenotypes. Ndntm1.1Mus mutant mice have severe neonatal respiratory deficiency that is central in origin and is caused by serotonergic dysfunction.69, 70, 71 Relevant to hypotonia, necdin enhances myoblast survival by facilitating the degradation of the mediator of apoptosis CCAR1/CARP1, in a study that used both tgMlcNec mice and Ndntm1.1Mus mice.72 Necdin regulates the quiescence and response to genotoxic stress of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, as demonstrated using Ndntm2Stw mutant mice.73, 74, 75, 76, 77 Necdin also protects neurons against mitochondrial insults by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis, in a study that used the Ndntm1Ky mice.78 Necdin controls epidermal growth factor receptor signaling linked to astrocyte differentiation,79 interacts with the RING finger protein Bmi1 to control the proliferation of neural precursor cells in the neocortex,80 and modulates the thyroid axis.81 Along with MAGEL2, necdin facilitates leptin receptor recycling, as shown in cultured cells and in mouse brain tissue.14 Lastly, functional interactions between necdin and other proteins have been uncovered, including interactions with the alpha subunit of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein G082 and the ciliary protein cystin.83 Thus, necdin is implicated in many physiological processes that are relevant to the complex clinical features in PWS.

Interventional Studies in NDN Mice

Only one study has described an interventional trial in Ndn mutant mice. Serotonin deficiency in newborn animals causes neurological, respiratory, and behavioral abnormalities.84 Fluoxetine (Prozac) is an antidepressant and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor that increases extracellular serotonin levels (Table 1). Many Ndntm1.1Mus mutant mice present with apnea at birth and have more apneas per hour and a higher accumulated apnea duration compared to WT. Respiratory deficits in mutant pups were suppressed by transient treatment with fluoxetine.71 The researchers suggest that respiratory complications in PWS infants could respond to therapeutics that target the serotonin system.71

SNHG14, SNORD116, and IPW

SNHG14 (small nucleolar RNA host gene 14) is a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) initiated at the SNRPN gene. SNHG14 is also known as LNCAT or U-UBE3A-ATS.85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 A cluster of snoRNAs is generated from the SNHG14 introns, with the best studied of these being the SNORD116 (small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 116; previously known as HBII-85) cluster.91 SnoRNAs are nuclear RNAs present in ribonucleoprotein complexes (snoRNPs) that function to modify other RNAs or participate in ribosomal RNA maturation. IPW (imprinted in Prader-Willi92, 93) is a stable non-coding RNA generated from three exons of the SNHG14 lncRNA. Several individuals with atypical PWS carrying chromosomal deletions, as small as 118 kb, within SNHG14 have been described.94 In the case with the smallest deletion, expression of SNORD116 (and likely also IPW) was abolished, while expression of SNRPN was intact.94 The deletions within SNHG14/SNORD116 cluster could modify the expression of MAGEL2 through long-range chromatin interactions.95 This would explain how microdeletions that include the SNORD116 cluster produce phenotypes that overlap with Schaaf-Yang syndrome caused by MAGEL2 mutations.

Mouse Models of Snord116 and Ipw Deficiency

Two lines of mice were developed to assess Snord116 function: B6(Cg)-Snord116tm1.1Uta/J96 and Del(7Ipw-Snord116)tm1Jbro.97 Other transcripts, such as the murine equivalents of SNHG14 and IPW,98 are also disrupted in both of these mutant mouse lines. Abnormal phenotypes affecting the neuronal, endocrine pancreas, bone mass, cognitive, and behavioral systems were discovered in Snord116tm1.1Uta mice.99, 100, 101, 102 While these mice have impaired growth, they do not display hyperphagia or obesity, nor do they have defects in the hypothalamic leptin or melanocortin systems.103 A deficiency in prohormone convertase (PC1, encoded by Pcsk1) and impaired prohormone processing was identified in Snord116tm1.1Uta mice in one study.104 Another study of the same mice revealed no differences in hypothalamic Pcsk1 expression in either fed or fasted states.103 Interestingly, the hypothalamus-specific reintroduction of Snord116 into Snord116tm1.1Uta mutant mice increased energy expenditure.105, 106 Adult-onset deletion of Snord116 in conditional (floxed) Snord116tm1Uta mice resulted in reduced feeding and increased fat mass in one study.107 In another study with the same mice, virally induced cre-mediated deletion of Snord116 increased food intake and body weight in a subset of adult treated mice.103 These seemingly contradictory results have yet to be resolved. In Snord116tm1.1Uta mice, the lncRNA was shown to modulate diurnal gene expression, DNA methylation, and energy expenditure.108, 109, 110 Working-for-food behaviors and sleep patterns were abnormal in Del(7Ipw-Snord116)tm1Jbro mutant mice.111, 112 More studies are needed to resolve the possible role of Snord116 in the hypothalamic and circadian regulation of energy balance.

Interventional Studies in Snord116 Mutant Mice

Four studies have described therapeutic interventions in Snord116 mutant mice (Table 1). Snord116tm1.1Uta mutant mice had an abnormal response to the anorexic effect of growth hormone secretagogue receptor inhibitors and to exenatide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist.113 In the same mice, a growth hormone secretagogue (ghrelin) receptor agonist (HM01) rescued excess postnatal, preweaning mortality.114 These data support exploration of the therapeutic potential of ghrelin receptor agonist administration in the failure to thrive period of PWS. An extract of cactus (Caralluma fimbriata, CFE) was fed to a cohort of Snord116tm1.1Uta mutant mice, and the effect on 4-h food intake was measured after 9 weeks of treatment. CFE appeared to decrease food intake in Snord116tm1.1Uta mutant mice, although differences between mutant and WT untreated mice in their responses to appetite stimulants complicate the interpretation of these results. Another study showed that housing Snord116tm1.1Uta mutant mice at a thermoneutral temperature (30°C), instead of the ambient temperature commonly maintained in animal facilities, normalized many phenotypes in these mice, including low bone mineral density, length, food intake, and energy expenditure. This last study demonstrates that the low body mass and low body fat of Snord116 mutant mice causes cold stress in these animals. Phenotypes in Snord116 mutant mice raised at ambient temperature need to be interpreted with caution, as they may reflect cold adaptation rather than being intrinsic to the genetic defect in these animals.115

SNRPN and the IC

SNRPN (small nuclear ribonucleotide polypeptide N) encodes a small nuclear ribonucleotide protein that functions in pre-mRNA processing. The SNRPN promoter and coding exons are shared with the SNHG14 non-coding RNA described above. A complex set of regulatory elements collectively referred to as the IC lies upstream of the SNRPN coding exons. There is no evidence that loss of the SNRPN protein itself contributes to phenotypes in PWS. Chromosomal deletions that affect the SNRPN upstream exons and include the IC cause PWS by impairing the allele-specific expression of genes normally subject to imprinting control.

Mouse Models of SNRPN and IC Deficiency

Mice were generated that carry a targeted deletion of 35 kb including 16 kb upstream of Snrpn and exons 1–6.116 When this deletion is paternally derived, the “PWS-ICdel” mice have severe postnatal growth failure and lethality unless maintained on an outbred strain background (JAX stock: 012443, B6.129-Snrpntm2Cbr/J). Surviving PWS-ICdel have reduced locomotor activity and cognitive deficits.117 They have low fat mass for their body weight and increased thermogenesis, and some of the energy imbalance was rescued by housing the mice in thermoneutral conditions.118 After an overnight fast, the PWS-ICdel mice consumed more food than WT in the first 30 min of refeeding,119 perhaps because their small size increases their energy needs at ambient temperature, or because of an underlying mitochondrial dysfunction.120 Another group generated a line of mice (Del(7Ube3a-Snrpn)1Alb) carrying a targeted deletion from Snrpn to Ube3a, but not including the IC.121 Similar to the Snord116 mice, Del(7Ube3a-Snrpn)1Alb mutant mice have severe growth retardation, hypotonia, and high rates of lethality before weaning.121 The surviving mice were fertile and did not become obese.

Interventional Studies in PWS-ICdel Mice and pΔS-U Mice

PWS-ICdel adult mice were housed under thermoneutral conditions (i.e., 30°C rather than room temperature, 20°C–22°C), which abolished the excess food consumption observed in these mice at room temperature.118 Like the Snord116 mice, phenotypes in PWS-ICdel mutant mice raised at ambient temperature need to be interpreted with caution, as seemingly abnormal feeding behavior may in fact reflect a normal adaptation to cold temperatures. The anorectic effect of a 5-HT2CR-specific agonist, WAY-161503, was investigated in PWS-ICdel mutant mice.122 WT mice reduced their food intake on treatment with WAY-161503, but no difference in food consumption was observed in the PWS-ICdel mutant mice. This suggests that one or more genes that are inactivated in PWS-ICdel mutant mice are required for normal serotonin receptor 2C function. UNC0642 is a selective inhibitor of euchromatic histone lysine N-methyltransferase-2 (EHMT2, also known as G9a). UNC0642 activated the maternal copy of PWS region genes, including the snoRNA cluster Snord116, and improved survival of Del(7Ube3a-Snrpn)1Alb) mice.123 The proposed mechanism for this reactivation is a selective reduction of the dimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2) at the PWS IC by UNC0642, without changes in DNA methylation.123

Other Genes: MKRN3, NPAP1, and Non-imprinted Genes

MKRN3 (Makorin ring finger protein 3) is widely expressed throughout the body.124 MKRN3 encodes a protein that contains a RING zinc finger motif and several other zinc finger motifs and that may function as a E3 ubiquitin ligase. Inactivating mutations in MKRN3 cause familial precocious puberty.125 There is no mouse model for MKRN3 deficiency published to date. NPAP1 (nuclear pore-associated protein 1) encodes a protein that is closely related to the transmembrane nucleoporin gene POM121.126 NPAP1 has bi-allelic expression in testis but is paternally expressed in fetal brain. NPAP1 is a primate-specific gene, so there are no mouse models for NPAP1. OCA2 is the human homolog of the mouse p (pink-eyed dilution) gene127 and encodes an integral membrane protein involved in pigmentation. Mutations in OCA2 cause type 2 oculocutaneous albinism. Although OCA2 is outside the imprinted region, OCA2 becomes hemizygous in children carrying a PWS deletion, and this can have deleterious effects. For example, children with the deletion form of PWS who carry a deleterious variant on the remaining OCA2 maternal allele can have phenotypes that range from hypopigmentation to a more severe condition, oculocutaneous albinism with loss of vision.128 Likewise, some individuals with PWS have larger deletions (type I deletions) that include non-imprinted genes (TUBGCP5, NIPA1, NIPA2, and CYFIP1) proximal to the imprinted gene cluster.129 Haploinsufficiency for these genes may contribute to more severe behavioral phenotypes observed in individuals with type I deletions compared to those with type II deletions who carry two copies of these genes.

Comparison between Interventional Studies in Humans with PWS versus Animal Models of PWS

Many mechanisms of action exist for compounds in development for treatment of PWS symptoms. Preclinical studies can provide invaluable information about how animals respond, in vivo, to these potentially effective therapeutics. Conversely, animal testing of compounds already in therapeutic use or clinical trials may accelerate their adaptation into clinical practice or yield insight into the mechanism of action in PWS. Above, we have described 18 compounds or procedures that have been tested in six mouse models of PWS. At least seven of these classes of compounds have also been tested in double-blind placebo-controlled trials in PWS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Categories of Compounds Tested in Both Preclinical (Mouse) Models of PWS and in Humans with PWS

| Type of Drug | Compound | Mouse Model of PWS: Reference | Clinical Trials in PWS | Company/Trial Center | Outcomes | NCT or EudraCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropeptide hormones | oxytocin (examples only) FDA approved |

Magel2: 5 Magel2: 29 |

phase II phase III, 133,135,136,149 |

many sites | infant suckling; food intake; hyperphagia; behavior; social behavior |

NCT03197662 NCT02205034 NCT02013258 EudraCT: 2010-022370-14 EudraCT: 2017-003423-30 |

| carbetocin/FE 992097 EU approved | not trialed | phase II phase III, 150 |

Ferring Levo Therapeutics |

hyperphagia; behavior | NCT01968187 | |

| K+-ATP channel agonist | diazoxide FDA approved |

Magel2: 38 | not trialed | |||

| DCCR/extended release diazoxide choline investigational |

not trialed | phase II phase III |

Essentialis Soleno Therapeutics |

hyperphagia; REE |

NCT02034071 NCT02893618 NCT03440814 |

|

| Melanocortin 4 receptor agonists | MT-II/Melanotan 2 not approved |

Magel2: 6 | not trialed | |||

| RM-493 or setmelanotide investigational |

Magel2: 34 | phase II | Rhythm | weight loss; hyperphagia-related behavior | NCT02311673 | |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | exenatide (Byetta) FDA approved |

Snord116: 113 | exploratory, open label phase II 153,166 |

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Aintree University Hospital |

weight; metabolism ghrelin levels |

NCT01444898 EudraCT: 2010-023179-25 |

| exenatide extended release (Bydureon) | not trialed | phase III | Garvan Foundation, Australia | gastric emptying | ACTRN12616000710426 | |

| liraglutide (Saxenda) | not trialed | phase III | Novo Nordisk | BMI; hyperphagia; metabolism |

NCT02527200 EudraCT: 2014-004415-37 |

|

| Cannabinoids | oleoyl α-methyl serine (HU-671) investigational |

Magel2: 37 | ||||

| JD5037 or SLV-319 (ibipinabant) research only |

Magel2: 36 | |||||

| OEA (oleoylethanolamide) supplement |

Magel2: 39 | |||||

| cannabidiol (CBD) oral solution Under review by FDA |

phase II | Insys Therapeutics | hyperphagi, weight |

NCT02844933 NCT03458416 |

||

| rimonabant (Acomplia) withdrawn |

phase II 167 | Cornell Medical College Karolinska University Hospital | obesity |

NCT00603109 EudraCT: 2007-006305-25 |

||

| Ghrelin analog | ghrelin receptor agonist HM01 | Snord116: 114 | ||||

| livoletide (AZP-531) GLWL 01 |

phase IIa 168 phase II phase II |

Alize Millendo Therapeutics GLWL Research |

blood glucose levels; weight hyperphagia hyperphagia, behavior |

EudraCT: 2014-001670-34 NCT03790865 NCT03274856 |

||

| Natural supplement | cactus extract from Caralluma fimbriata | Snord116: 165 | ||||

| cactus extract from Caralluma fimbriata | phase I 169 | Victoria University, Australia | hyperphagia; behavior | ACTRN12611000334909 | ||

Clinical trials in PWS were recently reviewed.130, 131 The largest number of clinical trials in PWS have tested oxytocin or an oxytocin analog (carbetocin, intranasal FE992097), finding positive effects on both hyperphagia and behavior.132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150 A trial of beloranib, a methionine aminopeptidase 2 (MetAP2) inhibitor that promotes loss of fat mass, was terminated in 2016 after adverse events involving excess blood clot formation,151 while other MetAP2 compounds are in development.152 An open label 6-month trial of exenatide (Byetta, a GLP-1 receptor agonist) in 10 overweight or obese subjects with PWS was recently completed, demonstrating that treatment reduced appetite without any effect on weight loss in the short term.153 Trials of a controlled release formulation of diazoxide, a K+-ATP channel agonist (https://soleno.life) and of AZP-531 (livoletide), an unacylated ghrelin analog (https://www.millendo.com) have only been reported through press releases. Other registered interventional clinical trials have not yet yielded outcomes (reviewed in Miller et al.130). These include GLWL-01 for treatment of hyperphagia (NCT03274856), cannabidiol oral solution for treatment of hyperphagia-related behavior and reduction of body weight (NCT02844933), co-administration of tesofensine and metoprolol for reduction of body weight (tesomet, NCT03149445), RM-493 or setmelanotide, and a melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) agonist for weight loss and hyperphagia-related behavior (NCT02311673). Many more studies have described the use of other agents in small numbers of individuals with PWS or in open (non-blinded) trials.

How Can We Improve Translation to Clinical Trials and Reduce Attrition between Preclinical Trials and Clinical Trials?

Extrapolating from the last five years of advances in preclinical and clinical trials, we predict that the next decade will see an intensification of efforts to make PWS a treatable condition. Many agents tested in preclinical models of PWS have not been examined in clinical trials, and conversely clinical trials are being pursued for agents that have not been investigated in preclinical models. At least three important lessons have been learned from the last five years of preclinical studies in PWS. The first lesson echoes the words of Dr. Joseph Garner, who argues that “if we want animal models to translate to human outcomes, then we need to start performing animal experiments as if they were human trials.”154 Important recommendations have been developed to address issues of translatability of preclinical studies to clinical trials (e.g., ARRIVE guidelines155). However, such recommendations have not yet been universally adopted in the PWS research community. For example, publications should use the proper nomenclature for the animal strain being used, including the stock name, strain background and backcross information, and references to the original descriptions of the model. Authors should refrain from using terms like “PWS mice,” and ensure that at the very least, the publication abstract and methods section contain the proper strain name. Justification of cohort sizes using power calculations, inclusion of both sexes of mice, proper blinding to genotype, and statistical analyses are all important factors in preclinical studies.155 Where possible, preclinical studies should use doses that are properly scaled to human doses, rather than dosing to maximum tolerability in the animal156. Additional guidelines may be required for specific types of studies (e.g., mouse metabolism157 or behavior158).

The second lesson, “know your animals,” was driven home during studies of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (motor neuron disease, ALS) models in which human trials of tested compounds failed to replicate findings from the animal models.159 In mouse models of PWS, factors such as the pulsatile nature of growth hormone release, the frequent small meals consumed, and the fact that mice are quadrupedal complicate interpretation in studies of endocrine function, appetite control, and scoliosis, respectively. The small size and low fat mass of Snord116tm1.1Uta and Del(7Ipw-Snord116)tm1Jbro adult mutant mice and the novelty-induced anorexia described in Magel2tm1Stw mice are examples of how mouse models may not completely capture phenotypes described in patients. It is important to use a model that actually demonstrates the endophenotype that is targeted by the therapeutic. The use of a decision flowchart that asks whether functional or surrogate endpoints can be measured in a particular model, and whether the mode of action of the therapeutic is understood, is recommended.160 Great care must be taken not to anthropomorphize results from animal models, but instead to interpret results within context of the physiology of the species and extrapolate the mechanism to support the utility (or not) of a particular intervention in clinical studies.

The third, and perhaps most difficult lesson, is that preclinical studies should ideally be performed in the context of, and with the support of, clinical trialists and adequate funding. Interactions between clinical and preclinical trialists would be facilitated if preclinical researchers could make an argument that a positive result from a preclinical study would either accelerate translation into clinical practice or would elucidate a mechanism of action thus accelerating the development of related therapies. Many promising therapeutics (e.g., beloranib) have never been tested in animal models of PWS (Table 3), and even compounds that have been tested in animal models (Table 1) have typically only been examined in one genetic model. Preclinical research is much more expensive than research designed to understand disease pathology or therapeutic mechanism of action in an animal model. The inclusion of both sexes, larger cohorts, different doses, and testing at different ages have a multiplicative effect on research budgets. The favored strategy to reduce costs, moving go/no-go decisions as early as possible in the pipeline,159 is difficult in preclinical research, where the majority of the financial investment (breeding of large cohorts) takes place very early in the experimental plan. A central registry for PWS preclinical trials that includes detailed methods would also facilitate the reproduction of promising results by other investigators.

Table 3.

Compounds Tested in Humans with PWS but Not in Preclinical Models of PWS

| Type of Drug | Compound/Procedure | Clinical Trials in PWS | Company/Trial Center | Outcomes | Clinical Trial Registration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth hormone | growth hormone FDA approved |

prescribed as needed | Karolinska University Hospital; Novo Nordisk |

body composition; linear growth; bone mineral density; cognitive and adaptive function |

NCT00372125 NCT00705172 |

| Stimulant | modafinil FDA approved |

case series, open label 161 | Hôpital Purpan, Toulouse, France | sleepiness | N/A |

| Synthetic somatostatin | octreotide FDA approved |

phase II 162 | British Columbia’s Children’s Hospital | BMI; appetite; behavior; ghrelin concentration | NCT00175305 |

| Anticonvulsant | topiramate FDA approved |

phase II phase III |

University of Florida-Brain Institute Hopitaux de Paris |

self-injurious behavior eating disorders; self-mutilation; irritability and impulsivity; metabolic status |

NCT00065923 NCT02810483 |

| Aromatase Inhibitor | anastrozole FDA approved |

phase II | Hôpital Armand Trousseau, Paris | bone maturation related to pathological adrenarche | NCT01520467 |

| Serotonin-noradrenaline-dopamine reuptake inhibitor/beta-blocker | tesomet (tesofensine and metoprolol) Investigational/FDA approved |

phase II | Saniona | body weight |

NCT03149445 EudraCT:2016-003694-18 |

| Ghrelin pathway | GLWL-01 investigational |

phase II | GLWL Research | hyperphagia, HQ-CT score | NCT03274856 |

| Methionine aminopeptidase 2 inhibitor | beloranib not approved |

phase II phase III 151 |

Zafgen | HQ-CT; weight; fat and lean; QOL |

NCT01818921 NCT02179151 EudraCT:2015-000660-33 |

| Probiotic |

Bifidobacterium lactis B94 (probiotic) supplement |

phase II | University of Florida, Gainesville | stool frequency | NCT03277157 |

| Brain stimulation | vagal nerve stimulation FDA approved |

exploratory | University of Cambridge 163 | behavior | N/A |

| Brain stimulation | deep brain stimulation FDA approved |

phase I | Federal University of São Paulo | weight | NCT02297022 |

| Brain stimulation | transcranial brain stimulation FDA approved |

exploratory 164 phase II |

University Kansas Medical Center Federal University of São Paulo Laval, Canada |

hyperphagia; depression food cravings questionnaire; brain activity |

NCT01863017 NCT03324906 NCT02758262 |

Examples of therapeutics in development not yet studied in PWS: Pitolisant (Wakix), ZGN-1061. Examples of therapeutics in PWS clinical studies but not controlled trials: ketogenic diet, tofogliflozin (SGLT2 inhibitor), metformin, naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave), N-acetylcysteine, risperidone. N/A, not applicable; HQ-CT, Hyperphagia Questionnaire for Clinical Trials; QOL, quality of life.

We have reached an inflection point in preclinical studies of therapeutics in animal models of PWS. Increased investment in the preclinical arena is likely to accelerate the entry of compounds into a therapeutic pipeline and facilitate progress through the long clinical trials process. It is imperative that investigators preparing for preclinical studies learn from experiences in other rare disorders with neurological, muscular, endocrine, and other relevant issues by improving study design and reporting and by carefully choosing models and endpoints to maximally benefit individuals living with PWS.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by operating grant MOP 130367 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- 1.McCandless S.E., Committee on Genetics Clinical report—health supervision for children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatrics. 2011;127:195–204. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalsner L., Chamberlain S.J. Prader-Willi, Angelman, and 15q11-q13 Duplication Syndromes. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2015;62:587–606. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnick J.L., Nicholls R.D., Wevrick R., Prader-Willi Syndrome Animal Models Working Group Recommendations for the investigation of animal models of Prader-Willi syndrome. Mamm. Genome. 2013;24:165–178. doi: 10.1007/s00335-013-9454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bervini S., Herzog H. Mouse models of Prader-Willi Syndrome: a systematic review. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaller F., Watrin F., Sturny R., Massacrier A., Szepetowski P., Muscatelli F. A single postnatal injection of oxytocin rescues the lethal feeding behaviour in mouse newborns deficient for the imprinted Magel2 gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:4895–4905. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercer R.E., Michaelson S.D., Chee M.J., Atallah T.A., Wevrick R., Colmers W.F. Magel2 is required for leptin-mediated depolarization of POMC neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus in mice. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boccaccio I., Glatt-Deeley H., Watrin F., Roëckel N., Lalande M., Muscatelli F. The human MAGEL2 gene and its mouse homologue are paternally expressed and mapped to the Prader-Willi region. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:2497–2505. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S., Kozlov S., Hernandez L., Chamberlain S.J., Brannan C.I., Stewart C.L., Wevrick R. Expression and imprinting of MAGEL2 suggest a role in Prader-willi syndrome and the homologous murine imprinting phenotype. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1813–1819. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.12.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tacer K.F., Potts P.R. Cellular and disease functions of the Prader-Willi Syndrome gene MAGEL2. Biochem. J. 2017;474:2177–2190. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamaludin A.A., Smolarchuk C., Bischof J.M., Eggert R., Greer J.J., Ren J., Lee J.J., Yokota T., Berry F.B., Wevrick R. Muscle dysfunction caused by loss of Magel2 in a mouse model of Prader-Willi and Schaaf-Yang syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:3798–3809. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozlov S.V., Bogenpohl J.W., Howell M.P., Wevrick R., Panda S., Hogenesch J.B., Muglia L.J., Van Gelder R.N., Herzog E.D., Stewart C.L. The imprinted gene Magel2 regulates normal circadian output. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1266–1272. doi: 10.1038/ng2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hao Y.H., Fountain M.D., Jr., Fon Tacer K., Xia F., Bi W., Kang S.H., Patel A., Rosenfeld J.A., Le Caignec C., Isidor B. USP7 Acts as a Molecular Rheostat to Promote WASH-Dependent Endosomal Protein Recycling and Is Mutated in a Human Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:956–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao Y.H., Doyle J.M., Ramanathan S., Gomez T.S., Jia D., Xu M., Chen Z.J., Billadeau D.D., Rosen M.K., Potts P.R. Regulation of WASH-dependent actin polymerization and protein trafficking by ubiquitination. Cell. 2013;152:1051–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wijesuriya T.M., De Ceuninck L., Masschaele D., Sanderson M.R., Carias K.V., Tavernier J., Wevrick R. The Prader-Willi syndrome proteins MAGEL2 and necdin regulate leptin receptor cell surface abundance through ubiquitination pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:4215–4230. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pravdivyi I., Ballanyi K., Colmers W.F., Wevrick R. Progressive postnatal decline in leptin sensitivity of arcuate hypothalamic neurons in the Magel2-null mouse model of Prader-Willi syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:4276–4283. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaaf C.P., Gonzalez-Garay M.L., Xia F., Potocki L., Gripp K.W., Zhang B., Peters B.A., McElwain M.A., Drmanac R., Beaudet A.L. Truncating mutations of MAGEL2 cause Prader-Willi phenotypes and autism. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1405–1408. doi: 10.1038/ng.2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fountain M.D., Aten E., Cho M.T., Juusola J., Walkiewicz M.A., Ray J.W., Xia F., Yang Y., Graham B.H., Bacino C.A. The phenotypic spectrum of Schaaf-Yang syndrome: 18 new affected individuals from 14 families. Genet. Med. 2017;19:45–52. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soden S.E., Saunders C.J., Willig L.K., Farrow E.G., Smith L.D., Petrikin J.E., LePichon J.B., Miller N.A., Thiffault I., Dinwiddie D.L. Effectiveness of exome and genome sequencing guided by acuity of illness for diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:265ra168. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urreizti R., Cueto-Gonzalez A.M., Franco-Valls H., Mort-Farre S., Roca-Ayats N., Ponomarenko J., Cozzuto L., Company C., Bosio M., Ossowski S. A De Novo Nonsense Mutation in MAGEL2 in a Patient Initially Diagnosed as Opitz-C: Similarities Between Schaaf-Yang and Opitz-C Syndromes. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44138. doi: 10.1038/srep44138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mejlachowicz D., Nolent F., Maluenda J., Ranjatoelina-Randrianaivo H., Giuliano F., Gut I., Sternberg D., Laquerrière A., Melki J. Truncating Mutations of MAGEL2, a Gene within the Prader-Willi Locus, Are Responsible for Severe Arthrogryposis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:616–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enya T., Okamoto N., Iba Y., Miyazawa T., Okada M., Ida S., Naruto T., Imoto I., Fujita A., Miyake N. Three patients with Schaaf-Yang syndrome exhibiting arthrogryposis and endocrinological abnormalities. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2018;176:707–711. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matuszewska K.E., Badura-Stronka M., Śmigiel R., Cabała M., Biernacka A., Kosinska J., Rydzanicz M., Winczewska-Wiktor A., Sasiadek M., Latos-Bieleńska A. Phenotype of two Polish patients with Schaaf-Yang syndrome confirmed by identifying mutation in MAGEL2 gene. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2018;27:49–52. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobling R., Stavropoulos D.J., Marshall C.R., Cytrynbaum C., Axford M.M., Londero V., Moalem S., Orr J., Rossignol F., Lopes F.D. Chitayat-Hall and Schaaf-Yang syndromes:a common aetiology: expanding the phenotype of MAGEL2-related disorders. J. Med. Genet. 2018;55:316–321. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong W., Wang Y., Lu Y., Ye T., Song C., Xu Y., Li M., Ding J., Duan Y., Zhang L. Whole-exome Sequencing Helps the Diagnosis and Treatment in Children with Neurodevelopmental Delay Accompanied Unexplained Dyspnea. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5214. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fountain M.D., Schaaf C.P. Prader-Willi Syndrome and Schaaf-Yang Syndrome: Neurodevelopmental Diseases Intersecting at the MAGEL2 Gene. Diseases. 2016;4:E2. doi: 10.3390/diseases4010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy J.M., McCann-Crosby B.M., Rech M.E., Yin J., Chen C.A., Ali M.A., Nguyen H.N., Miller J.L., Schaaf C.P. Hormonal, metabolic and skeletal phenotype of Schaaf-Yang syndrome: a comparison to Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2018;55:307–315. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bischof J.M., Stewart C.L., Wevrick R. Inactivation of the mouse Magel2 gene results in growth abnormalities similar to Prader-Willi syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2713–2719. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fountain M.D., Tao H., Chen C.A., Yin J., Schaaf C.P. Magel2 knockout mice manifest altered social phenotypes and a deficit in preference for social novelty. Genes Brain Behav. 2017;16:592–600. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meziane H., Schaller F., Bauer S., Villard C., Matarazzo V., Riet F., Guillon G., Lafitte D., Desarmenien M.G., Tauber M., Muscatelli F. An Early Postnatal Oxytocin Treatment Prevents Social and Learning Deficits in Adult Mice Deficient for Magel2, a Gene Involved in Prader-Willi Syndrome and Autism. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;78:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahoney C., Kroeger D., Grinevich V., Scammell T. Oxytocin fibers in the lateral hypothalamus promote arousal in a mouse model of PWS. Sleep. 2017;40(Suppl 1):A50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maillard J., Park S., Croizier S., Vanacker C., Cook J.H., Prevot V., Tauber M., Bouret S.G. Loss of Magel2 impairs the development of hypothalamic Anorexigenic circuits. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:3208–3215. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oncul M., Dilsiz P., Ates Oz E., Ates T., Aklan I., Celik E., Sayar Atasoy N., Atasoy D. Impaired melanocortin pathway function in Prader-Willi syndrome gene-Magel2 deficient mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:3129–3136. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luck C., Vitaterna M.H., Wevrick R. Dopamine pathway imbalance in mice lacking Magel2, a Prader-Willi syndrome candidate gene. Behav. Neurosci. 2016;130:448–459. doi: 10.1037/bne0000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bischof J.M., Van Der Ploeg L.H., Colmers W.F., Wevrick R. Magel2-null mice are hyper-responsive to setmelanotide, a melanocortin 4 receptor agonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016;173:2614–2621. doi: 10.1111/bph.13540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arble D.M., Pressler J.W., Sorrell J., Wevrick R., Sandoval D.A. Sleeve gastrectomy leads to weight loss in the Magel2 knockout mouse. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016;12:1795–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knani I., Earley B.J., Udi S., Nemirovski A., Hadar R., Gammal A., Cinar R., Hirsch H.J., Pollak Y., Gross I. Targeting the endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor system for treating obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome. Mol. Metab. 2016;5:1187–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baraghithy S., Smoum R., Drori A., Hadar R., Gammal A., Hirsch S., Attar-Namdar M., Nemirovski A., Gabet Y., Langer Y. Magel2 Modulates Bone Remodeling and Mass in Prader-Willi Syndrome by Affecting Oleoyl Serine Levels and Activity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2019;34:93–105. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bischof J.M., Wevrick R. Chronic diazoxide treatment decreases fat mass and improves endurance capacity in an obese mouse model of Prader-Willi syndrome. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018;123:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Igarashi M., Narayanaswami V., Kimonis V., Galassetti P.M., Oveisi F., Jung K.M., Piomelli D. Dysfunctional oleoylethanolamide signaling in a mouse model of Prader-Willi syndrome. Pharmacol. Res. 2017;117:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruyama K., Usami M., Aizawa T., Yoshikawa K. A novel brain-specific mRNA encoding nuclear protein (necdin) expressed in neurally differentiated embryonal carcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;178:291–296. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91812-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang W.H., Guenthner C.J., Xu J., Nguyen T., Schwarz L.A., Wilkinson A.W., Gozani O., Chang H.Y., Shamloo M., Luo L. Molecular and Neural Functions of Rai1, the Causal Gene for Smith-Magenis Syndrome. Neuron. 2016;92:392–406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berger S.I., Ciccone C., Simon K.L., Malicdan M.C., Vilboux T., Billington C., Fischer R., Introne W.J., Gropman A., Blancato J.K., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Exome analysis of Smith-Magenis-like syndrome cohort identifies de novo likely pathogenic variants. Hum. Genet. 2017;136:409–420. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1767-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muscatelli F., Abrous D.N., Massacrier A., Boccaccio I., Le Moal M., Cau P., Cremer H. Disruption of the mouse Necdin gene results in hypothalamic and behavioral alterations reminiscent of the human Prader-Willi syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:3101–3110. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.20.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai T.F., Armstrong D., Beaudet A.L. Necdin-deficient mice do not show lethality or the obesity and infertility of Prader-Willi syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:15–16. doi: 10.1038/8722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuwako K., Hosokawa A., Nishimura I., Uetsuki T., Yamada M., Nada S., Okada M., Yoshikawa K. Disruption of the paternal necdin gene diminishes TrkA signaling for sensory neuron survival. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7090–7099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2083-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gérard M., Hernandez L., Wevrick R., Stewart C.L. Disruption of the mouse necdin gene results in early post-natal lethality. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:199–202. doi: 10.1038/13828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mercer R.E., Kwolek E.M., Bischof J.M., van Eede M., Henkelman R.M., Wevrick R. Regionally reduced brain volume, altered serotonin neurochemistry, and abnormal behavior in mice null for the circadian rhythm output gene Magel2. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2009;150B:1085–1099. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tennese A.A., Gee C.B., Wevrick R. Loss of the Prader-Willi syndrome protein necdin causes defective migration, axonal outgrowth, and survival of embryonic sympathetic neurons. Dev. Dyn. 2008;237:1935–1943. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bush J.R., Wevrick R. The Prader-Willi syndrome protein necdin interacts with the E1A-like inhibitor of differentiation EID-1 and promotes myoblast differentiation. Differentiation. 2008;76:994–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pagliardini S., Rent J., Wevrick R., Greer J.J. Neurodevelopmental abnormalities in the brainstem of prenatal mice lacking the Prader-Willi syndrome gene Necdin. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;605:139–143. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73693-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zanella S., Barthelemy M., Muscatelli F., Hilaire G. Necdin gene, respiratory disturbances and Prader-Willi syndrome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;605:159–164. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73693-8_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andrieu D., Meziane H., Marly F., Angelats C., Fernandez P.A., Muscatelli F. Sensory defects in Necdin deficient mice result from a loss of sensory neurons correlated within an increase of developmental programmed cell death. BMC Dev. Biol. 2006;6:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deponti D., François S., Baesso S., Sciorati C., Innocenzi A., Broccoli V., Muscatelli F., Meneveri R., Clementi E., Cossu G., Brunelli S. Necdin mediates skeletal muscle regeneration by promoting myoblast survival and differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:305–319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pagliardini S., Ren J., Wevrick R., Greer J.J. Developmental abnormalities of neuronal structure and function in prenatal mice lacking the prader-willi syndrome gene necdin. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:175–191. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62964-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee S., Walker C.L., Karten B., Kuny S.L., Tennese A.A., O’Neill M.A., Wevrick R. Essential role for the Prader-Willi syndrome protein necdin in axonal outgrowth. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:627–637. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ren J., Lee S., Pagliardini S., Gérard M., Stewart C.L., Greer J.J., Wevrick R. Absence of Ndn, encoding the Prader-Willi syndrome-deleted gene necdin, results in congenital deficiency of central respiratory drive in neonatal mice. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1569–1573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01569.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller N.L., Wevrick R., Mellon P.L. Necdin, a Prader-Willi syndrome candidate gene, regulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons during development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:248–260. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pessina P., Conti V., Tonlorenzi R., Touvier T., Meneveri R., Cossu G., Brunelli S. Necdin enhances muscle reconstitution of dystrophic muscle by vessel-associated progenitors, by promoting cell survival and myogenic differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:827–838. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aebischer J., Sturny R., Andrieu D., Rieusset A., Schaller F., Geib S., Raoul C., Muscatelli F. Necdin protects embryonic motoneurons from programmed cell death. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bush J.R., Wevrick R. Loss of Necdin impairs myosin activation and delays cell polarization. Genesis. 2010;48:540–553. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuwajima T., Hasegawa K., Yoshikawa K. Necdin promotes tangential migration of neocortical interneurons from basal forebrain. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:3709–3714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5797-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zanella S., Tauber M., Muscatelli F. Breathing deficits of the Prader-Willi syndrome. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2009;168:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bush J.R., Wevrick R. Loss of the Prader-Willi obesity syndrome protein necdin promotes adipogenesis. Gene. 2012;497:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fujiwara K., Hasegawa K., Ohkumo T., Miyoshi H., Tseng Y.H., Yoshikawa K. Necdin controls proliferation of white adipocyte progenitor cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y., Elf S.E., Miyata Y., Sashida G., Liu Y., Huang G., Di Giandomenico S., Lee J.M., Deblasio A., Menendez S. p53 regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kubota Y., Osawa M., Jakt L.M., Yoshikawa K., Nishikawa S. Necdin restricts proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells during hematopoietic regeneration. Blood. 2009;114:4383–4392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sciorati C., Touvier T., Buono R., Pessina P., François S., Perrotta C., Meneveri R., Clementi E., Brunelli S. Necdin is expressed in cachectic skeletal muscle to protect fibers from tumor-induced wasting. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1119–1125. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ju H., Lee S., Lee J., Ghil S. Necdin modulates osteogenic cell differentiation by regulating Dlx5 and MAGE-D1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;489:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rieusset A., Schaller F., Unmehopa U., Matarazzo V., Watrin F., Linke M., Georges B., Bischof J., Dijkstra F., Bloemsma M. Stochastic loss of silencing of the imprinted Ndn/NDN allele, in a mouse model and humans with prader-willi syndrome, has functional consequences. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matarazzo V., Muscatelli F. Natural breaking of the maternal silence at the mouse and human imprinted Prader-Willi locus: A whisper with functional consequences. Rare Dis. 2013;1:e27228. doi: 10.4161/rdis.27228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matarazzo V., Caccialupi L., Schaller F., Shvarev Y., Kourdougli N., Bertoni A., Menuet C., Voituron N., Deneris E., Gaspar P. Necdin shapes serotonergic development and SERT activity modulating breathing in a mouse model for Prader-Willi syndrome. eLife. 2017;6:e32640. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.François S., D’Orlando C., Fatone T., Touvier T., Pessina P., Meneveri R., Brunelli S. Necdin enhances myoblasts survival by facilitating the degradation of the mediator of apoptosis CCAR1/CARP1. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Asai T., Liu Y., Di Giandomenico S., Bae N., Ndiaye-Lobry D., Deblasio A., Menendez S., Antipin Y., Reva B., Wevrick R., Nimer S.D. Necdin, a p53 target gene, regulates the quiescence and response to genotoxic stress of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2012;120:1601–1612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-393983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Asai T., Liu Y., Nimer S.D. Necdin, a p53 target gene, in stem cells. Oncotarget. 2013;4:806–807. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yao C., Kobayashi M., Chen S., Nabinger S.C., Gao R., Liu S.Z., Asai T., Liu Y. Necdin modulates leukemia-initiating cell quiescence and chemotherapy response. Oncotarget. 2017;8:87607–87622. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lafontaine J., Rodier F., Ouellet V., Mes-Masson A.M. Necdin, a p53-target gene, is an inhibitor of p53-mediated growth arrest. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lafontaine J., Tchakarska G., Rodier F., Mes-Masson A.M. Necdin modulates proliferative cell survival of human cells in response to radiation-induced genotoxic stress. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hasegawa K., Yasuda T., Shiraishi C., Fujiwara K., Przedborski S., Mochizuki H., Yoshikawa K. Promotion of mitochondrial biogenesis by necdin protects neurons against mitochondrial insults. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10943. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fujimoto I., Hasegawa K., Fujiwara K., Yamada M., Yoshikawa K. Necdin controls EGFR signaling linked to astrocyte differentiation in primary cortical progenitor cells. Cell. Signal. 2016;28:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Minamide R., Fujiwara K., Hasegawa K., Yoshikawa K. Antagonistic interplay between necdin and Bmi1 controls proliferation of neural precursor cells in the embryonic mouse neocortex. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e84460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hasegawa K., Kawahara T., Fujiwara K., Shimpuku M., Sasaki T., Kitamura T., Yoshikawa K. Necdin controls Foxo1 acetylation in hypothalamic arcuate neurons to modulate the thyroid axis. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:5562–5572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0142-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ju H., Lee S., Kang S., Kim S.S., Ghil S. The alpha subunit of Go modulates cell proliferation and differentiation through interactions with Necdin. Cell Commun. Signal. 2014;12:39. doi: 10.1186/s12964-014-0039-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu M., Yang C., Tao B., Bu S., Guay-Woodford L.M. The ciliary protein cystin forms a regulatory complex with necdin to modulate Myc expression. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e83062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trowbridge S., Narboux-Nême N., Gaspar P. Genetic models of serotonin (5-HT) depletion: what do they tell us about the developmental role of 5-HT? Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 2011;294:1615–1623. doi: 10.1002/ar.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cavaillé J., Buiting K., Kiefmann M., Lalande M., Brannan C.I., Horsthemke B., Bachellerie J.P., Brosius J., Hüttenhofer A. Identification of brain-specific and imprinted small nucleolar RNA genes exhibiting an unusual genomic organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:14311–14316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250426397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Galiveti C.R., Raabe C.A., Konthur Z., Rozhdestvensky T.S. Differential regulation of non-protein coding RNAs from Prader-Willi Syndrome locus. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:6445. doi: 10.1038/srep06445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vitali P., Royo H., Marty V., Bortolin-Cavaillé M.L., Cavaillé J. Long nuclear-retained non-coding RNAs and allele-specific higher-order chromatin organization at imprinted snoRNA gene arrays. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:70–83. doi: 10.1242/jcs.054957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leung K.N., Vallero R.O., DuBose A.J., Resnick J.L., LaSalle J.M. Imprinting regulates mammalian snoRNA-encoding chromatin decondensation and neuronal nucleolar size. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:4227–4238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yin Q.F., Yang L., Zhang Y., Xiang J.F., Wu Y.W., Carmichael G.G., Chen L.L. Long noncoding RNAs with snoRNA ends. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Le Meur E., Watrin F., Landers M., Sturny R., Lalande M., Muscatelli F. Dynamic developmental regulation of the large non-coding RNA associated with the mouse 7C imprinted chromosomal region. Dev. Biol. 2005;286:587–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Runte M., Hüttenhofer A., Gross S., Kiefmann M., Horsthemke B., Buiting K. The IC-SNURF-SNRPN transcript serves as a host for multiple small nucleolar RNA species and as an antisense RNA for UBE3A. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2687–2700. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.23.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wevrick R., Kerns J.A., Francke U. The IPW gene is imprinted and is not expressed in the Prader-Willi syndrome. Acta Genet. Med. Gemellol. (Roma) 1996;45:191–197. doi: 10.1017/s000156600000129x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stelzer Y., Sagi I., Yanuka O., Eiges R., Benvenisty N. The noncoding RNA IPW regulates the imprinted DLK1-DIO3 locus in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of Prader-Willi syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:551–557. doi: 10.1038/ng.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bieth E., Eddiry S., Gaston V., Lorenzini F., Buffet A., Conte Auriol F., Molinas C., Cailley D., Rooryck C., Arveiler B. Highly restricted deletion of the SNORD116 region is implicated in Prader-Willi Syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;23:252–255. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Langouët M., Glatt-Deeley H.R., Chung M.S., Dupont-Thibert C.M., Mathieux E., Banda E.C., Stoddard C.E., Crandall L., Lalande M. Zinc finger protein 274 regulates imprinted expression of transcripts in Prader-Willi syndrome neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:505–515. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ding F., Prints Y., Dhar M.S., Johnson D.K., Garnacho-Montero C., Nicholls R.D., Francke U. Lack of Pwcr1/MBII-85 snoRNA is critical for neonatal lethality in Prader-Willi syndrome mouse models. Mamm. Genome. 2005;16:424–431. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-2460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Skryabin B.V., Gubar L.V., Seeger B., Pfeiffer J., Handel S., Robeck T., Karpova E., Rozhdestvensky T.S., Brosius J. Deletion of the MBII-85 snoRNA gene cluster in mice results in postnatal growth retardation. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wevrick R., Francke U. An imprinted mouse transcript homologous to the human imprinted in Prader-Willi syndrome (IPW) gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:325–332. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adhikari A., Copping N.A., Onaga B., Pride M.C., Coulson R.L., Yang M., Yasui D.H., LaSalle J.M., Silverman J.L. Cognitive deficits in the Snord116 deletion mouse model for Prader-Willi syndrome. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2018.05.011. Published online May 23, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zieba J., Low J.K., Purtell L., Qi Y., Campbell L., Herzog H., Karl T. Behavioural characteristics of the Prader-Willi syndrome related biallelic Snord116 mouse model. Neuropeptides. 2015;53:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khor E.C., Fanshawe B., Qi Y., Zolotukhin S., Kulkarni R.N., Enriquez R.F., Purtell L., Lee N.J., Wee N.K., Croucher P.I. Prader-Willi Critical Region, a Non-Translated, Imprinted Central Regulator of Bone Mass: Possible Role in Skeletal Abnormalities in Prader-Willi Syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]