Abstract

Phospholipase Cε (PLCε) and anaerobic glycolysis were determined to be involved in the development of human urinary bladder cancer (UBC), but the mechanisms remain unclear. In the present study, 64 bladder cancer specimens and 42 adjacent tissue specimens were obtained from 64 patients, and immunochemistry indicated that PLCε and lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA) are overexpressed in UBC. PLCε and LDHA were demonstrated to be positively correlated at transcription levels, indicating that one of these two genes may be regulated by another. To elucidate the mechanisms, PLCε was knocked down in T24 cells by short hairpin RNA, and then signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation and LDHA were determined to be downregulated, which indicated that PLCε may serve roles upstream of LDHA through STAT3 to regulate glycolysis in UBC. Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation and luciferase reporter assays were performed to confirm that STAT3 could bind to the promoter of the LDHA gene to enhance its expression. A xenograft tumor mouse model also demonstrated similar results as the in vitro experiments, further confirming the role of PLCε in regulating bladder cell growth in vivo. Collectively, the present study demonstrated that PLCε may regulate glycolysis through the STAT3/LDHA pathway to take part in the development of human UBC.

Keywords: urinary bladder cancer, phospholipase Cε, lactate dehydrogenase A, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

Introduction

Human urinary bladder cancer (UBC) is the most common urological tumor, which is frequently metastatic and recurrent (1). According to an epidemiologic study, the UBC incidence of 2015 in China is 8.05/100,000, and the mortality is 3.29/100,000 (2). However, the mechanisms of development of UBC remain unclear.

The rapid growth of cancer cells requires a lot of energy, and relying only on the aerobic oxidation of mitochondria is not sufficient (3). Therefore, cancer cells also acquire energy for growth by anaerobic glycolysis, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect (4). Metabolomics analysis demonstrated that cancer cells exhibit an increased energy metabolic phenotype for glycolysis under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (5). It has been reported that glucose transporter, lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and pyruvate kinase are highly expressed in numerous tumor types, including lung and gastric cancer, and 18-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computerized tomography had been used to confirm that tumor cells are more capable of using glucose, compared with normal cells (6,7).

Phospholipase Cε (PLCε) is a member of the phospholipase C family, which catalyzes polyphosphoinositol, such as phosphatidylinositol 4,5-diphosphate, and produces the second messenger, including 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol (8). Our previous studies demonstrated that PLCε may serve an important role in UBC growth (9,10) and activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway (11). STAT3 is involved in the development and progression of a variety of tumor types, including colon, gastric and liver cancer (12–14), which may be partially achieved by regulating anaerobic glycolysis (15). Since our previous results demonstrated that PLCε may act upstream of STAT3, it may be considered that PLCε participates in cancer cell growth by regulating anaerobic glycolysis. Therefore, in order to further investigate the role and mechanisms of PLCε in bladder cancer, the T24 cell line and a control strain that stably knocked down PLCε were established using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting PLCε and non-target control. Subsequently, the mRNA expression levels of tumor associated molecules were examined with gene chip and multiple signaling pathways, including P53, mitogen-activated protein kinase, pyruvate metabolism, tryptophan metabolism, and cysteine and methionine metabolism, and they were significantly decreased in PLCε-deficient T24 cells, compared with control cells. As an important functional gene in aerobic glycolysis (16,17), LDHA was also determined to be regulated by PLCε in T24 cells (unpublished data), indicating the role of PLCε in glycolysis.

In the present study, the correlation among PLCε, STAT3 and LDHA in UBC growth was confirmed. Additionally, these data may provide insights into mechanisms and potential treatments of UBC.

Materials and methods

Tissue specimens

A total of 64 UBC tissue samples and 42 adjacent tissue samples were obtained from 64 patients (male:female, 53:11; age range, 34–88 years; median age, 65 years) who underwent surgery at the Department of Urology in the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China) from January 2017 to December 2017. The histological grade and stage were determined according to the UICC guidelines (18). The patients provided informed consent. All samples were stored at −80°C until required. The present study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of Chongqing Medical University (approval no. 2016-152).

Cell culture

T24 and HeLa cells were purchased from the Shanghai Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). Subsequently, T24 cells was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium and HeLa cells was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, and both were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The PLCε stable knockdown T24 cell line was described in our previous study (9). A total of 5×104 T24 cells/well were cultured in a 6-well plate at 37°C overnight until ~60% confluence. The cells were then transfected with a mixture of 0.4 µg PLCε shRNA (sh-PLCε) or 0.4 µg non-target control shRNA (sh-NC), and 8 µl Effectene transfections reagent (Qiagen China Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) in 1 ml of fresh serum-free RPMI-1640 medium. The transfected cells were selected using G418 (400 µg/ml). Monoclonal cells were collected after 4 weeks of exposure to selective pressure and were further cultured at 37°C for subsequent experimentation.

Cell proliferation

Cell viability was analyzed via Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; cat. no. 96992) assays. For small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections, cells were plated and in a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells/well and cultured overnight at 37°C. Subsequently, 0.5 µl gene-specific siRNAs (20 µM) each well were transfected in the presence of Opti-MEM medium (cat. no. 51985034; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (cat. no. 4476093001; Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocols. siRNA targeting LDHA (5′-CGAACTGGGCAGTATAAAC-3′) and negative control (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′) were designed and synthesized by Shanghai Genepharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). After 48 h post transfection, 100 µl CCK-8 solution was added to each well of the plate after various time points (12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h), and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Subsequently, the absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm.

Reagents and antibodies

Stattic (cat. no. S7024) and recombinant human interleukin-6 (IL-6; cat. no. CTP0061) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA) and Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), respectively. Antibodies against β-actin (cat. no. sc-47778) and PLCε (cat. no. sc-28402) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA), and antibodies against LDHA (cat. no. 3582), total STAT3 (cat. no. 4904) and phospho-STAT3 (cat. no. 9145) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-HA antibody (cat. no. ab9110) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

Immunochemistry

Sections were observed using an upright phase contrast light microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at magnifications of ×200. The tissue specimens were fixed with 10% neutral formalin at room temperature for 15 min, embedded in paraffin and 5 µm thick sections were prepared. Paraffin wax-embedded tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated (incubated in 100, 95, 80 and 75% series gradient ethanol at room temperature for 3 min each and then in distilled water for 10 min) at room temperature and microwaved at 95°C for 30 min in sodium citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0; Anhui Leagene Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Huaibei, Anhui China, http://www.leagene.cn) to repair antigen epitopes. The tissue sections were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with 3% H2O2 and blocked by 5% normal goat serum (cat. no. AR0009; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China) at 37°C for 10 min in order to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity. Following this, tissue sections were incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies targeting PLCε (dilution 1:50) and LDHA (dilution 1:200) at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rat (cat. no. 31830) or rabbit anti-goat IgG antibody (cat. no. 31732) (dilution, 1:5,000; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 45 min at 37°C, followed by incubation with streptavidin peroxidase at 37°C for 15 min. Sections were stained with the chromogen diaminobenzidine at room temperature for 2 min (OriGene Technologies, Inc., Beijing, China) until a brown color developed. The cell nucleus was counterstained with hematoxylin at room temperature for 2 min. After rinsing twice with running water, the sections were immersed in 95% ethanol for 5 sec and then stained with eosin for 1 min at room temperature. All images were quantified using two parameters, staining positive rate and positive stating intensity. The positive staining intensity criteria were as follows: 0 points, no staining; 1 point, light yellow; 2 points, brownish yellow; and 3 points, brown. The cell positive staining rate was as follows: 0%, no positive staining; 1, <5% positive staining; 2, 5–50% positive staining; 3, >50% positive staining. The total score is the sum of the positive staining intensity score and the cell positive staining rate score. For statistical analysis, the slice tissue with a total score of 0–2 was judged to be negative, and the slice with a total score of 3–6 was judged to be positive.

Protein isolation and western blotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared from cells that had been washed with PBS 3 times and harvested by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay lysis buffer, containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% NP-40, 0.2% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 1% protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), on ice for 30 min with occasional vortex. The lysates were then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Subsequently, supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were measured using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Cell lysates (40 µg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P membranes; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with blocking buffer (5% non-fat milk and 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Following incubation with appropriate primary antibodies (β-actin, 1:1,000 dilution; PLCε, 1:500 dilution; LDHA, 1:1,000 dilution; total STAT3, 1:1,000 dilution; phospho-STAT3, 1:1,000 dilution) overnight at 4°C, membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. A16096; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h, and protein bands were detected using a Electrochemiluminescence Plus Western Blotting Detection system (cat. no. RPN2133; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK) with a ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). cDNA was generated using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RT-qPCR was performed using a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) with specific sense and antisense primers in a 20 µl reaction volume containing 10 µl SYBR®-Green PCR Master mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), 10 µl 1 µM primer stock and 40 ng cDNA. The conditions of RT-qPCR were as follows: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Gene relative expression was analyzed using the method of comparative 2−ΔΔCq (19) and then normalized by β-actin. The primers were as follows: β-actin, forward, 5′-GTCTGCCTTGGTAGTGGATAATG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCGAGGACGCCCTATCATGG-3′. PLCε, forward, 5′-GCTTCTTAACACGGGACTTGG-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTTCAAGGGCATTGTGCTCTC-3′. LDHA, forward, 5′-ATGGCAACTCTAAAGGATCAGC-3′, and reverse, 5′-CCAACCCCAACAACTGTAATCT-3′.

Glucose consumption and lactate production

A total of 1×105 cells were incubated in each well of a 6-well plate at 37°C with RPMI-1640 medium overnight. Following the corresponding treatment, medium was collected by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min at room temperature to remove the cells, and glucose consumption was measured using a Glucose (HK) Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. GAHK20). Lactate levels and pH values in the culture media were measured using a Lactate Assay kit (BioVision, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

HeLa cells were co-transfected with pcDNA-HA-STAT3 and pGL4-pLDHA plasmids (OBio Technology Corp., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Mammalian expression vector pcDNA-HA-STAT3 was purchased from Sino Biological, Inc. (Beijing, China). Briefly, complete coding sequence of STAT3 (2,313 bp; reference sequence: NM_139276) was cloned into pcDNA3.1 (+) using restriction site HindIII and NotI. HA tag (5′-TATCCTTACGACGTGCCTGACTACGCC-3′) was fused to the N-terminus of STAT3 open reading frame. The LDHA promoter sequence (−2,000 to +200 bp; NM_005566) was artificially synthesized by OBio Technology and cloned into the pGL4.10 plasmid (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). After 48 h post transfection, cells were treated with formaldehyde at a final concentration of 1% at room temperature for 10 min to crosslink DNA and proteins. The crosslinking reaction was stopped by adding glycine at 0.125 mol/l final concentration for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold 1X PBS and resuspended in cell lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCL (pH 8.0), 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MaCl2, 0.5% NP-40 and protease inhibitors) and incubated on ice for 15 min. The cell suspension was vortexed at 1,000 × g for 5 sec every 5 min to aid the release of the nuclei. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 800 × g at 4°C for 5 min, resuspended in nuclei lysis buffer [1% SDS, 5 mmol/l EDTA, 50 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and protease inhibitors] and sonicated to generate chromatin to length of 200–500 bp (10×15 sec at 55% maximum potency). Following centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, samples (400 mg of protein extracts) were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with 2 µg anti-HA antibody (dilution 1:200; cat. no. ab9110; Abcam). Subsequently, 1% supernatant from the immunoprecipitation was saved as total input of chromatin and was processed with the eluted immunoprecipitates beginning at the crosslink reversal step. Following this, 20 µl magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280 Sheep anti Mouse IgG; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were added into each sample and incubated at 4°C for 4 h with rotation. Immunoprecipitates were washed once with each of the ChIP Low Salt buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton-100, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Hepes and 150 mM NaCl; pH 7.5), ChIP High Salt buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton Χ-100, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Hepes and 500 mM NaCl; pH 7.5), ChIP LiCl buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholated, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris-HCl; pH 8.0) and TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA). Immunocomplexes were eluted with 90 µl elution buffer (1% SDS and 50 mmol/l NaHCO3) and 10 g RNase A was added to the pooled eluates. Crosslinks were reverted by incubation at 65°C for at least 6 h. Samples were added with 1 l 20 g/l proteinase K and incubated for 2 h at 45°C. After incubation at 95°C for 10 min, samples were purified with a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (28104; Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Based on the predicted binding sites by the JASPAR database (http://jaspar.genereg.net/), corresponding ChIP primers (ChIP1, 2 and 3) were designed for three predicted possible binding sites as follows: ChIP1, forward, 5′-CCCCAACCCAAGCCTTTCAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-ACCTCAGGGCAGGGCAGATT-3′; ChIP2, forward, 5′-CCCCATTTCAGAACCTAGAGTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGCTTTGAGATAGATCCATAA-3′; and ChIP3, forward, 5′-TTCCCTAATCATTTGGTCTTTCC-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTGGGCCTGTATTCTTGCTG-3′. DNA samples were amplified with target promoter-specific primers using RT-qPCR, as aforementioned, except for the number of cycles being adjusted to 50 cycles, and normalized to normal IgG control.

Luciferase reporter assay

Construction of eukaryotic expression plasmid pcDNA-HA-STAT3 and luciferase reporter plasmid pGL4-pLDHA [-2,000 to +200 bp of LDHA (reference sequence: NM_005566) promoter inserted into pGL4.10 luciferase reporter plasmid] was aforementioned. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pcDNA-HA-STAT3, pGL4-pLDHA and pGL4.7-hRluc (cat. no. E6881; Promega Corporation) using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After 48 h post transfection, the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system (cat. no. E1910; Promega Corporation) was used to detect luciferase activity, according to the manufacturer's protocol. All experiments were performed in triplicate and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Xenograft tumor model in vivo

Male BALB/c-nude mice (3–5 weeks old; weighing 16–20 g) were used to establish the T24 ×enograft tumor model. A total of 15 mice were purchased from Hufukang Bioscience Inc. (Beijing, China) and housed in individual ventilated cage systems in Experimental Animal Center of Chongqing Medical University at constant temperature (22°C) and humidity (50–60%), and with a 12 h light-dark cycle. All the mice had free access to food and water throughout the experiments. The experimental procedures were approved by the Chongqing Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The T24 cells (5×106) were suspended in Matrigel (BD Biosciences; Becton-Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and subcutaneously implanted into the left flank of nude mice. Following implantation, tumor volumes were measured every 6 days until the mice were sacrificed by CO2 at day 30.

Statistics

Each experiment was repeated at least three times with two technical replicates each unless indicated otherwise, as this was generally sufficient to achieve statistical significance for differences. Statistical significance between groups was calculated by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's test and statistical significance between the two groups was calculated by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test using commercially available statistical software (SigmaPlot 11.0 for Windows; Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Data are presented as means ± standard deviations. Correlation analysis was determined using Pearson's correlation analysis and χ2 test was used for enumeration data. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

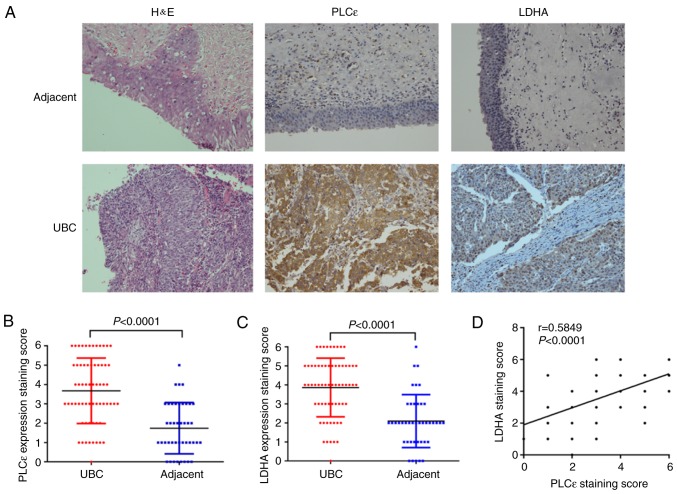

PLCε and LDHA are overexpressed in UBC

To examine the expression profile of PLCε and LDHA in UBC, the expression of PLCε and LDHA in UBC specimens (n=64) and adjacent specimens (n=42) was analyzed using immunochemistry. Positive rates of PLCε (76.6%) and LDHA (79.7%) in UBC specimens were significantly increased, compared with adjacent tissue samples (31.0 and 28.6% respectively; χ2 test; P<0.001; Table I).

Table I.

The association between PLCε and LDHA expression levels and clinical pathological parameters.

| P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. (%) | PLCε Positive (%) | LDHA Positive (%) | PLCε | LDHA |

| Specimens | <0.001a | <0.001a | |||

| UBC | 64 (100.0) | 49 (76.6) | 51 (79.7) | ||

| Adjacent | 42 (65.6) | 13 (31.0) | 12 (28.6) | ||

| Sex | 0.651 | 0.309 | |||

| Male | 53 (82.8) | 40 (75.5) | 41 (77.4) | ||

| Female | 11 (17.2) | 9 (81.8) | 10 (90.9) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.369 | 0.654 | |||

| ≥60 | 52 (81.3) | 41 (78.8) | 42 (80.8) | ||

| <60 | 12 (18.7) | 8 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) | ||

| Histologic stage (18) | 0.18 | 0.759 | |||

| Ta-T1 | 42 (65.6) | 30 (71.4) | 33 (78.6) | ||

| T2-T4 | 22 (34.4) | 19 (86.4) | 18 (81.8) | ||

| Histologic grade (18) | 0.819 | 0.574 | |||

| Low grade | 24 (37.5) | 18 (75.0) | 20 (83.3) | ||

| High grade | 40 (62.5) | 31 (77.5) | 31 (77.5) | ||

Statistically significant difference between UBC and adjacent specimens. PLCε, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase Cε; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; UBC, urinary bladder cancer.

Furthermore, the results of immunochemistry staining were quantified. Additionally, the arithmetic mean of staining scores of PLCε (3.672±0.211; n=64) and LDHA (3.859±0.193; n=64) in UBC were also significantly increased, compared with adjacent specimens (PLCε, 1.738±0.205; and LDHA, 2.095±0.215, respectively; n=42) (Fig. 1A-C), indicating the role of PLCε and LDHA in UBC development. Additionally, the staining scores of PLCε and LDHA were positively correlated (Fig. 1D). Subsequently, a total of 21 pairs of UBC and adjacent tissue samples were collected to perform protein and mRNA detection for PLCε and LDHA, and the identical results as immunochemical staining were obtained. Both protein (Fig. 1E-H) and mRNA (Fig. 1I-K) relative expression of PLCε and LDHA were significantly increased in UBC, compared with adjacent tissues, and also positively correlated.

Figure 1.

PLCε and LDHA are overexpressed in human UBC. (A-C) Comparison of H&E and immunohistochemical staining between UBC specimens (n=64) and adjacent tissue specimens (n=42). Magnification, ×200. (D) Correlation of staining scores between PLCε and LDHA (n=64). (E) Protein isolated from 21 pairs of UBC and adjacent specimens were tested by western blot analysis. Quantified protein expression of (F) PLCε and (G) LDHA were significantly increased in UBC, compared with adjacent tissues, and (H) positively correlated. Relative mRNA expression of (I) PLCε and (J) LDHA were also increased in UBC, compared with adjacent tissues, and (K) positively correlated. PLCε, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase Cε; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; UBC, urinary bladder cancer; H&E, haematoxylin and eosin.

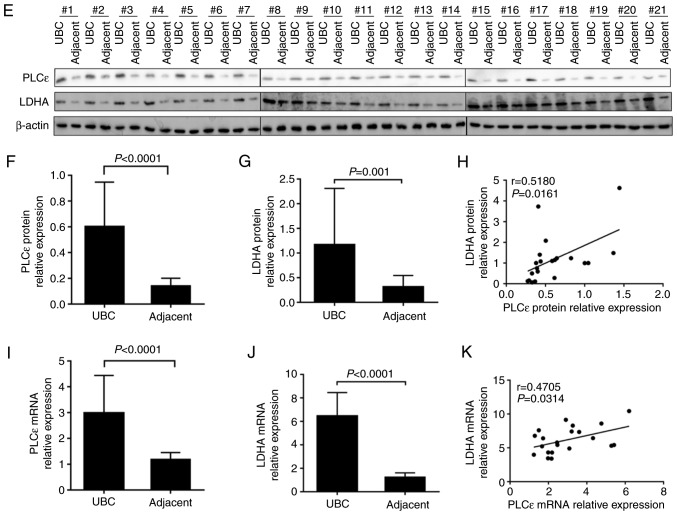

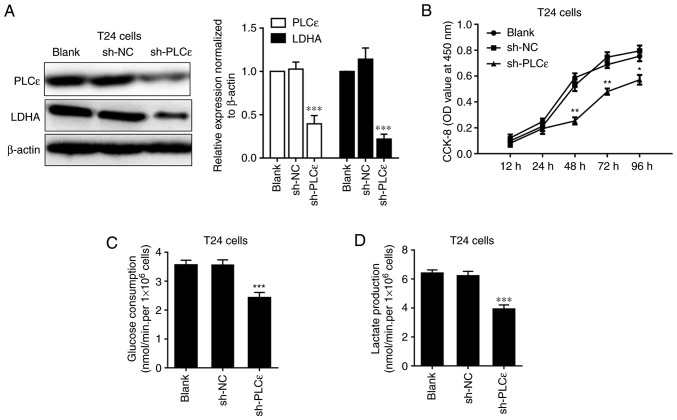

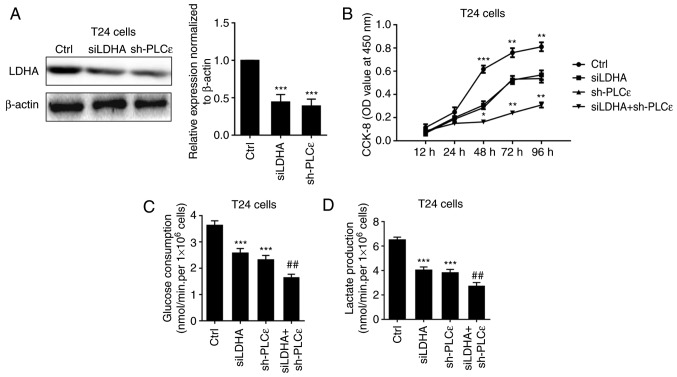

PLCε and LDHA knockdown inhibits cell proliferation, glucose consumption and lactate production in T24 cells

As PLCε and LDHA expression levels are positively correlated in human UBC, how these two proteins regulated each other were further investigated. Firstly, the expression of LDHA was detected in PLCε-deficient T24 cells, compared with sh-NC. A decrease of LDHA in T24 cells following PLCε knockdown indicated that PLCε may act upstream of LDHA (Fig. 2A). Consistent with our previous data (7), PLCε deficiency significantly inhibited T24 cells proliferation from 48 h post seeding (Fig. 2B). While LDHA is involved in anaerobic glycolysis, the effects of PLCε deficiency on glucose consumption and lactate production were also investigated. PLCε knockdown significantly inhibited glucose consumption (2.422±0.184 nmol/min/1×106 cells), compared with the sh-NC control group (3.559±0.179 nmol/min/1×106 cells) (Fig. 2C). Additionally, lactate production was also decreased by PLCε deficiency in T24 cells (3.919±0.291 vs. 6.210±0.323 nmol/min/1×106; Fig. 2D), compared with the sh-NC control group. To further elucidate the role of LDHA in PLCε mediated inhibition of cells proliferation and glycolysis, LDHA was knocked down by siRNA (Fig. 3A) to compare the effect of LDHA with PLCε on cells proliferation and glycolysis. As depicted in Fig. 3B-D, LDHA knockdown could achieve the identical inhibition to cell growth and glycolysis as PLCε, and these two genes had synergistic effects.

Figure 2.

LCε kncokdown decreases LDHA expression and inhibits cell proliferation, glucose consumption and lactate production in T24 cells. Impact of PLCε difiecncity on (A) LDHA expression, (B) cell proliferation, (C) glucose consumption and (D) lactate production in T24 cells. Values were presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, compared with the sh-NC group. PLCε, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase Cε; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; OD, optical density; NC, negative control; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

Figure 3.

Synergistic effects of LDHA and PLCε deficiency on cell proliferation, glucose consumption and lactate production. (A) LDHA and PLCε knockdown (B) inhibited cell proliferation, (C) glucose consumption and (D) lactate production in T24 cells. Values were presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, compared with the Ctrl group. ##P<0.01, compared with the sh-PLCε group. PLCε, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase Cε; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; si, small interfering; sh, short hairpin; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; Ctrl, control; OD, optical density.

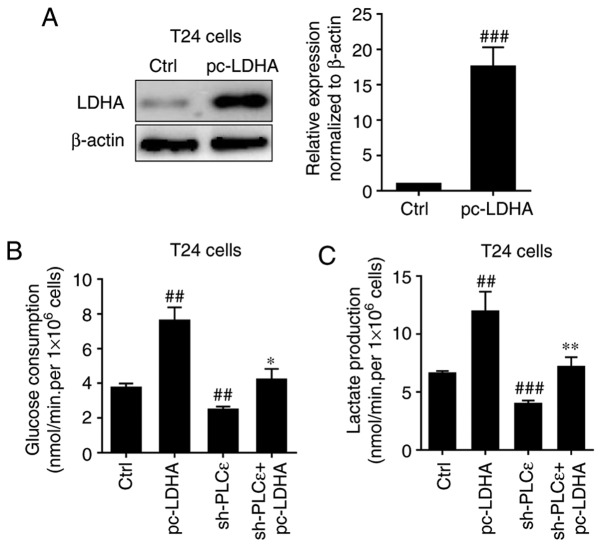

Subsequently, LDHA was overexpressed in T24 cells (Fig. 4A) to determine whether it could rescue cells glucose consumption and lactate production decline caused by PLCε deficiency. Overexpression of LDHA in T24 cells significantly upregulated glucose consumption (Fig. 4B) and lactate production (Fig. 4C) of bladder cancer cells, and completely blocked PLCε knockdown induced a decrease of glucose consumption and lactate production.

Figure 4.

Effect of LDHA overexpression on PLCε knockdown induces a decrease of glucose consumption and lactate production in T24 cells. (A) LDHA overexpression in T24 cells rescued PLCε deficiency mediated the inhibition of (B) glucose consumption and (C) lactate production. Values were presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001, compared with the control group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, compared with the sh-PLCε group. PLCε, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase Cε; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; sh, short hairpin; Ctrl, control.

STAT3 is involved in LDHA regulation by PLCε

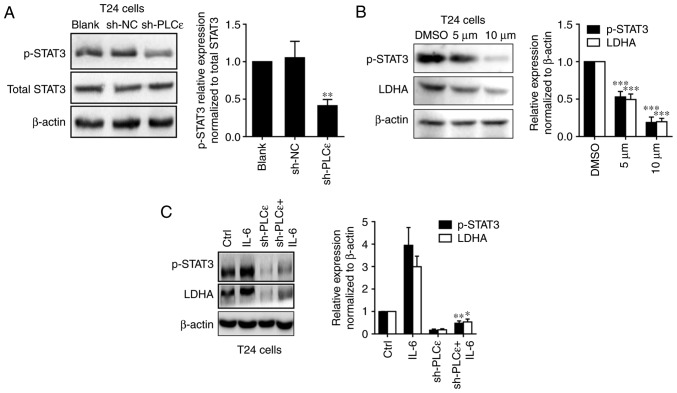

Our previous study determined that in bladder cancer cells, PLCε could participate in the regulation of STAT3 phosphorylation (11), and STAT3 activation can promote the growth of tumor cells by promoting anaerobic glycolysis (15,20). Therefore, it was speculated that PLCε regulated LDHA by affecting the activation of STAT3. As depicted in Fig. 5A, PLCε knockdown was able to downregulate the phosphorylation of STAT3 in T24 cells. Furthermore, the STAT3 inhibitor stattic (5 and 10 µM for 24 h) used to inhibit the phosphorylation of STAT3 also downregulated the expression of LDHA in UBC cells (Fig. 5B). Additionally, the STAT3 activator IL-6 could upregulate LDHA expression and blocked PLCε knockdown mediated a decrease of LDHA expression (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

PLCε regulates LDHA through the STAT3 pathway. (A) PLCε knockdown downregulated phosphorylation of STAT3 in T24 cells. (B) After 24 h post treatment of STAT3 inhibitor stattic (5 and 10 µM dissolved in DMSO), LDHA expression was downregulated in T24 cells with STAT3 phosphorylation inhibition. (C) IL-6 (20 ng/ml for 24 h) rescued PLCε knockdown mediated STAT3 phosphorylation and LDHA downregulation in T24 cells. Values were presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, compared with the (A) sh-NC group, (B) DMSO group or (C) sh-PLCε group. PLCε, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase Cε; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; sh, short hairpin; NC, negative control; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; p-, phospho-; IL, interleukin.

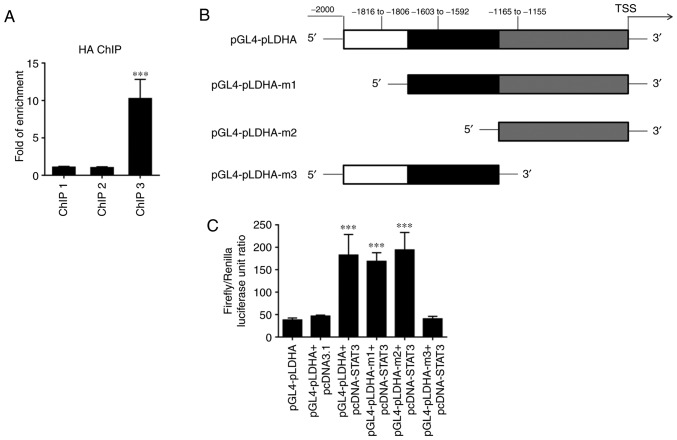

The aforementioned results indicate that PLCε may regulate the expression of LDHA by affecting the activation of STAT3. To further clarify the regulatory mechanism of the transcription factor STAT3 on LDHA, ChIP experiments were performed. The ChIP results revealed that STAT3 could bind to the promoter of LDHA at the site corresponding to ChIP3 primers due to a significant enrichment being observed in samples immunoprecipitated by HA-antibody (Fig. 6A). The dual luciferase reporter assay further confirmed that binding of this site of the LDHA promoter to STAT3 enhanced LDHA expression (Fig. 6B and C).

Figure 6.

STAT3 regulates LDHA expression through binding to its promoter. (A) ChIP results using 3 pairs of primers (ChIP 1, 2 and 3) targeting 3 binding sites predicted by JASPAR. (B) Model of the LDHA promoter luciferase reporter plasmid and its mutants. (C) Dual luciferase reporter assay using STAT3 overexpression plasmid and different LDHA promoter luciferase reporter mutant plasmids in HeLa cells. Values were presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. ***P<0.001, compared with the ChIP 1 and pGL4-pLDHA+pcDNA3.1 group. LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Knockdown of PLCε inhibits bladder cancer cell growth in vivo

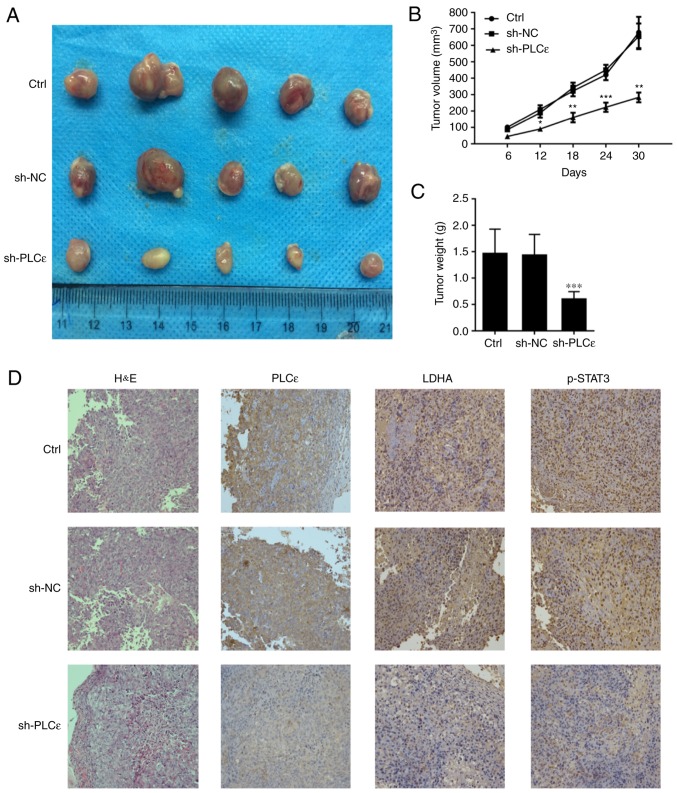

In the present study, BALB/c nude mice were injected with T24 cells without any treatment, T24 cells infected with sh-NC and T24 cells infected with sh-PLCε, in order for nude mice to be subcutaneously tumorigenic, and observed at the same time. As depicted in Fig. 7A and B, PLCε-deficient cancer cells growth was significantly reduced, compared with the control. At day 30 post cells injection, the weight of the tumor in the PLCε knockdown group was also reduced, compared with the control groups (Fig. 7C). The expression of PLCε, LDHA and phosphorylation of STAT3 was confirmed, which demonstrated similar results as the in vitro experiments (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

PLCε knockdown inhibits bladder cancer cell growth in a xenograft tumor mouse model. (A) Appearance of tumor from various groups of mouse model. (B) Tumor volume and (C) tumor weight were significantly inhibited by PLCε deficiency compared with sh-NC group. (D) PLCε, LDHA and STAT3 phosphorylation in xenograft tumors confirmed by immunochemistry. Values were presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, compared with the sh-NC group. PLCε, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase Cε; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase; sh, short hairpin; NC, negative control; H&E, haematoxylin and eosin; Ctrl, control.

Discussion

PLCε is a member of the PLC family (21). In addition to the typical catalytic X and Y, and C2 domains, PLCε has two carboxy-terminal Ras-binding domains and a guanine nucleotide exchange factor domain CDC25 (22,23), compared with other PLC family members. These special domains activate multiple signaling pathways to promote the development of tumors (24). Previous studies demonstrated that high expression of PLCε is associated with the development of a variety of cancer types, including gastric cancer and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (25,26). Previously, numerous studies demonstrated that the high expression of PLCε is associated with the development, invasion and metastasis of bladder cancer and prostate cancer in urinary system (9–11,27,28), but the mechanisms are not completely understood.

The Warburg effect has been demonstrated to provide energy for tumor initiation, invasion and metastasis in the majority of malignant tumor types, including pancreatic cancer and melanoma (29). The Warburg effect occurs when cancer cells grow too fast for them to survive under the condition of hypoxia and mitochondrial function gets damaged (30). Following glucose metabolizing to pyruvate, it no longer undergoes aerobic oxidation through the mitochondrial pathway and is converted into lactate by LDHA (31,32). In UBC, LDHA overexpression has already been demonstrated to promote progression by stimulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (33). In the present study, it was demonstrated that LDHA and PLCε were overexpressed in human UBC tissue specimens at the mRNA and protein level, and both of them are positively correlated. When PLCε was knocked down in T24 cells, LDHA expression, cells proliferation, glucose consumption and lactate production were also downregulated in the present study. These results indicated that PLCε may affect cell metabolisms to facilitate UBC progression. To clarify the role of LDHA in the regulation of bladder cancer cell growth by PLCε, cell growth or glucose metabolism of T24 cells was compared by knockdown of PLCε and LDHA. The knockdown of PLCε or LDHA inhibited cell growth and the Warburg effect to a similar extent, while synergistic effects were demonstrated when both were deficient. This may be associated with PLCε also promoting the growth of UBC cells through other pathways.

Ever since STATs were first identified in 1988 (34), this group of transcription factors has been demonstrated to be involved in multiple cellular processes, including cell proliferation (35,36), metabolism (37), immune response (38–40), autophagy (41) and apoptosis (42). Among them, the role of STAT3 in tumors is the most widely studied (14). Since PLCε was determined to regulate lipopolysaccharides-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation in UBC cells (11), and STAT3 has been confirmed to participate in the Warburg effect (37,43–45). Additionally, the effect of STAT3 phosphorylation on LDHA expression was investigated in the present study. As depicted in Fig. 5, inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation downregulated LDHA, and STAT3 activator IL-6 could rescue STAT3 inactivation mediated LDHA downregulation, indicating that STAT3 may be a transcription factor targeting LDHA. To date, LDHA have been determined to be regulated by a number of transcription factors in various cells, including cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP), cAMP response element binding protein (46), specificity protein 1 (47), hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (48), c-Myc (49), heat shock factor 1 (50), forkhead box M1 (51) and Kruppel like factor 4 (52). However, whether STAT3 participates in the regulation of LDHA expression has not been reported. In the present study, the results indicated that STAT3 may be involved in the regulation of LDHA transcription levels; therefore, whether LDHA promoter sequence has theoretical binding sites for STAT3 was investigated. According to the analysis from JASPAR, three predicted possible STAT3 binding sites were speculated and subsequent ChIP and luciferase reporter experiments also confirmed the binding of STAT3 to the LDHA promoter.

In conclusion, the present study determined for the first time that PLCε may regulate the expression of LDHA by affecting the activation of STAT3, and thus participate in the anaerobic glycolysis of cancer cells, affecting tumorigenesis. Subsequently, how PLCε regulates the activation of STAT3 requires further clarification. The present data enrich the understanding of the pathogenesis of UBC and may provide novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of UBC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant (grant no. cstc2018jcyjAX0188) from Chongqing science and technology commission.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

XW and CL supervised and directed the present study. HC performed the majority of the experiments. XW, CL and HC drafted the manuscript. XW, CL, YHa and YG contributed to the project design. YHe, MY and WS collected the tumor samples and the clinical data. All authors read and approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent for research purposes was obtained from each patient in the present study. Additionally, all applicable international, national and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. The study protocol regarding patients and animals was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (approval no. 2016-152).

Patients consent for publication

All patients were provided informed consent as part of a clinical protocol to participate in the present study and data publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Pashos CL, Botteman MF, Laskin BL, Redaelli A. Bladder cancer: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:311–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.106011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gwangwa MV, Joubert AM, Visagie MH. Crosstalk between the Warburg effect, redox regulation and autophagy induction in tumourigenesis. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2018;23:20. doi: 10.1186/s11658-018-0088-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantor JR, Sabatini DM. Cancer cell metabolism: One hallmark, many faces. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:881–898. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry J, Guillotte A, Luberto C, Del Poeta M. Characterization of inositol phospho-sphingolipid-phospholipase C 1 (Isc1) in Cryptococcus neoformans reveals unique biochemical features. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng H, Luo C, Wu X, Zhang Y, He Y, Wu Q, Xia Y, Zhang J. shRNA targeting PLCε inhibits bladder cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Urology. 2011;78:474 e477–e411. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang T, Liu T, Li L, Yang Z, Bai Y, Liu D, Kong C. Knockout of phospholipase Cε attenuates N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine-induced bladder tumorigenesis. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:2039–2045. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Ou L, Tang M, Wang Y, Wang X, Chen E, Diao J, Wu X, Luo X. Knockdown of PLCε inhibits inflammatory cytokine release via STAT3 phosphorylation in human bladder cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9723–9732. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ihle JN. STATs: Signal transducers and activators of transcription. Cell. 1996;84:331–334. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R, Jove R. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: New and unexpected biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:736–746. doi: 10.1038/nrc3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li M, Jin R, Wang W, Zhang T, Sang J, Li N, Han Q, Zhao W, Li C, Liu Z. STAT3 regulates glycolysis via targeting hexokinase 2 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:24777–24784. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le A, Cooper CR, Gouw AM, Dinavahi R, Maitra A, Deck LM, Royer RE, Vander Jagt DL, Semenza GL, Dang CV. Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A induces oxidative stress and inhibits tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2037–2042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914433107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augoff K, Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Tabola R. Lactate dehydrogenase 5: An old friend and a new hope in the war on cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;358:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magers MJ, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Williamson SR, Kaimakliotis HZ, Cheng L. Staging of bladder cancer. Histopathology. 2019;74:112–134. doi: 10.1111/his.13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wake MS, Watson CJ. STAT3 the oncogene-still eluding therapy? FEBS J. 2015;282:2600–2611. doi: 10.1111/febs.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley GG, Reks SE, Ondrako JM, Smrcka AV. Phospholipase C(epsilon): A novel Ras effector. EMBO J. 2001;20:743–754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hicks SN, Jezyk MR, Gershburg S, Seifert JP, Harden TK, Sondek J. General and versatile autoinhibition of PLC isozymes. Mol Cell. 2008;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wing MR, Snyder JT, Sondek J, Harden TK. Direct activation of phospholipase C-epsilon by Rho. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41253–41258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullen PJ. Ras effectors: Buying shares in Ras plc. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R342–R344. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Hu N, Wang Z, Yu K, Shu XO, Yuan JM, Zheng W, Dawsey SM, Dong LM, et al. A shared susceptibility locus in PLCE1 at 10q23 for gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:764–767. doi: 10.1038/ng.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smrcka AV, Brown JH, Holz GG. Role of phospholipase Cε in physiological phosphoinositide signaling networks. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1333–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ou L, Guo Y, Luo C, Wu X, Zhao Y, Cai X. RNA interference suppressing PLCE1 gene expression decreases invasive power of human bladder cancer T24 cell line. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;200:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ling Y, Chunli L, Xiaohou W, Qiaoling Z. Involvement of the PLCε/PKCα pathway in human BIU-87 bladder cancer cell proliferation. Cell Biol Int. 2011;35:1031–1036. doi: 10.1042/CBI20090101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg effect: How does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ristic B, Bhutia YD, Ganapathy V. Cell-surface G-protein- coupled receptors for tumor-associated metabolites: A direct link to mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2017;1868:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alfarouk KO, Verduzco D, Rauch C, Muddathir AK, Adil HH, Elhassan GO, Ibrahim ME, David Polo Orozco J, Cardone RA, Reshkin SJ, Harguindey S. Glycolysis, tumor metabolism, cancer growth and dissemination. A new pH-based etiopathogenic perspective and therapeutic approach to an old cancer question. Oncoscience. 2014;1:777–802. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JW, Dang CV. Cancer's molecular sweet tooth and the Warburg effect. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8927–8930. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang F, Ma S, Xue Y, Hou J, Zhang Y. LDH-A promotes malignant progression via activation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and conferring stemness in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;469:985–992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy DE, Kessler DS, Pine R, Reich N, Darnell JE., Jr Interferon-induced nuclear factors that bind a shared promoter element correlate with positive and negative transcriptional control. Genes Dev. 1988;2:383–393. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams JG. STAT signalling in cell proliferation and in development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:503–507. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.La Fortezza M, Schenk M, Cosolo A, Kolybaba A, Grass I, Classen AK. JAK/STAT signalling mediates cell survival in response to tissue stress. Development. 2016;143:2907–2919. doi: 10.1242/dev.132340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demaria M, Giorgi C, Lebiedzinska M, Esposito G, D'Angeli L, Bartoli A, Gough DJ, Turkson J, Levy DE, Watson CJ, et al. A STAT3-mediated metabolic switch is involved in tumour transformation and STAT3 addiction. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:823–842. doi: 10.18632/aging.100232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roca Suarez AA, Van Renne N, Baumert TF, Lupberger J. Viral manipulation of STAT3: Evade, exploit, and injure. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1006839. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villarino AV, Kanno Y, O'Shea JJ. Mechanisms and consequences of Jak-STAT signaling in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:374–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nan Y, Wu C, Zhang YJ. Interplay between janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling activated by type I interferons and viral antagonism. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1758. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maycotte P, Gearheart CM, Barnard R, Aryal S, Mulcahy Levy JM, Fosmire SP, Hansen RJ, Morgan MJ, Porter CC, Gustafson DL, Thorburn A. STAT3-mediated autophagy dependence identifies subtypes of breast cancer where autophagy inhibition can be efficacious. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2579–2590. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fathi N, Rashidi G, Khodadadi A, Shahi S, Sharifi S. STAT3 and apoptosis challenges in cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;117:993–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J, Liu T, Zhao L, Chen W, Hou H, Ye Z, Li X. Ginsenoside 20(S)Rg3 inhibits the Warburg effect through STAT3 pathways in ovarian cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:775–781. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akiyama Y, Iizuka A, Kume A, Komiyama M, Urakami K, Ashizawa T, Miyata H, Omiya M, Kusuhara M, Yamaguchi K. Effect of STAT3 inhibition on the metabolic switch in a highly STAT3-activated lymphoma cell line. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2015;12:133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darnell JE., Jr STAT3, HIF-1, glucose addiction and Warburg effect. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:890–891. doi: 10.18632/aging.100239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwast-Welfeld J, Soong CJ, Short ML, Jungmann RA. Identification of rat ovarian nuclear factors that interact with the cAMP-inducible lactate dehydrogenase A subunit promoter. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6941–6947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Short ML, Huang D, Milkowski DM, Short S, Kunstman K, Soong CJ, Chung KC, Jungmann RA. Analysis of the rat lactate dehydrogenase A subunit gene promoter/regulatory region. Biochem J. 1994;304:391–398. doi: 10.1042/bj3040391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semenza GL, Jiang BH, Leung SW, Passantino R, Concordet JP, Maire P, Giallongo A. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32529–32537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis BC, Prescott JE, Campbell SE, Shim H, Orlowski RZ, Dang CV. Tumor induction by the c-Myc target genes rcl and lactate dehydrogenase A. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6178–6183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao YH, Zhou M, Liu H, Ding Y, Khong HT, Yu D, Fodstad O, Tan M. Upregulation of lactate dehydrogenase A by ErbB2 through heat shock factor 1 promotes breast cancer cell glycolysis and growth. Oncogene. 2009;28:3689–3701. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui J, Shi M, Xie D, Wei D, Jia Z, Zheng S, Gao Y, Huang S, Xie K. FOXM1 promotes the Warburg effect and pancreatic cancer progression via transactivation of LDHA expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2595–2606. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi M, Cui J, Du J, Wei D, Jia Z, Zhang J, Zhu Z, Gao Y, Xie K. A novel KLF4/LDHA signaling pathway regulates aerobic glycolysis in and progression of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4370–4380. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.