Abstract

Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) is a major challenge in the treatment of prostate cancer (PCa). Phospholipase Cε (PLCε), an oncogene, has been found to be involved in the carcinogenesis, tumor proliferation and migration of several types of cancer. The effects, however, of PLCε on CRPC remains unclear. In the present study, the expression of PLCε and glioma-associated homolog (Gli)-1/Gli-2 in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), PCa and CRPC tissues and cells was investigated, and the correlations between PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2 in CRPC tissues and cell lines were further explored. In addition, the effect of PLCε on cell proliferation and invasion was assessed in CRPC cell lines, and the sensitivity of EN-R and 22RV1 cells to enzalutamide following the downregulation of PLCε expression was determined using lentivirus-mediated shPLCε and/or treatment with specific Gli inhibitor GANT61. It was found that the PLCε expression was excessively upregulated in the majority of CRPC tissues, and PLCε positivity was linked to poor progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with PCa. Furthermore, PLCε knockdown significantly suppressed CRPC cell proliferation and invasion. Of note, it was found that PLCε knockdown increased the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide in vitro by suppressing androgen receptor (AR) activities via the non-canonical Hedgehog/Gli-2 and p-STAT3 signaling pathways. PLCε knockdown was shown to increase the sensitivity of CRPC cell xenografts to enzalutamide in vivo. Finally, the combination of PLCε knockdown with GANT61 significantly sensitized CRPC cells to enzalutamide. Collectively, the results of the present study suggest that PLCε is a potential therapeutic target for CRPC.

Keywords: castration-resistant prostate cancer, phospholipase Cε, Hedgehog signaling, enzalutamide, GANT61, androgen receptor

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most common malignant tumors of the male urinary system. Statistical analysis has shown that more than 250,000 men succumb to PCa worldwide, with at least 900,000 new cases each year (1). In China, the incidence and mortality rates of PCa are annually increasing and tend to affect younger individuals (2,3). Current treatments for PCa include surgical treatment and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, almost all patients become resistant to long-term treatment, developing castration-resistant PCa (CRPC). CRPC is characterized by the increased activation and/or overexpression of androgen receptor (AR), resulting in the transcription of downstream target genes and tumor progression, despite castrate levels of androgen in the patient (4). Only a limited number of drugs can be effective once the tumor progresses to CRPC. Fortunately, enzalutamide is one of them. Enzalutamide is an AR inhibitor that competitively inhibits the binding of androgens to receptors and hinders the nuclear transport of the AR and the interaction of the receptor with DNA. Although enzalutamide has achieved some good clinical results (5–7), the subsequent drug resistance remains a challenge. It is therefore, necessary to determine the mechanism of CRPC resistance to enzalutamide.

Phospholipase Cε (PLCε), a multifunctional signaling protein harboring both PLC and guanine nucleotide exchange factor activities, was discovered by Song et al in 2001 (8,9). As a member of the human phospholipase C family, PLCε has been identified as an oncogene involved in carcinogenesis, tumor proliferation and migration (10,11). Our previous study showed that PLCε knockdown inhibited PCa cell proliferation via the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway (12). Furthermore, it was found that PLCε inhibited the biological behavior of PCa cells by downregulating AR (13). Nonetheless, the role of PLCε in CRPC cells remains unknown. The aim of the present study was to explore the effect of PLCε on the proliferation of CRPC cells and determine whether PLCε can sensitize CRPC cells to the AR axis inhibitor, enzalutamide.

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway plays a critical role in the development and homeostasis of many organs and tissues. It consists of the Hh ligand (Shh, Ihh and Dhh), two transmembrane receptor complexes [patched (Ptch) and smoothened (Smo)], and the downstream transcription factor glioma-associated homolog (Gli) family (Gli-1, Gli-2 and Gli-3). Gli-1 and Gli-2 are responsible for most transcriptional activator functions, whereas Gli-3 mainly acts as a repressor. Gli-1 is a direct transcriptional target of the Hh signaling and a marker for pathway activity (14). Vismodegib and cyclopamine are classic Hh signaling pathway inhibitors. Vismodegib blocks the biological activity of the Hh pathway. Since it binds to and hinders Smo, thus, preventing the systemic activation of the forward signaling, it has been used in the clinical treatment of basal cell carcinoma (15). Cyclopamine, a plant steroidal alkaloid that inhibits Smo, is a therapeutic strategy for PCa (16,17) and renal cell cancer (18). GANT61, a small molecule antagonist directly acting on downstream molecule Gli of the Hh signaling pathway, could interfere with cellular DNA binding of Glis (19). It has been reported that the Hh pathway is involved in PCa development, progression, treatment resistance (20,21) and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (17). An increasing number of studies have reported that the Hh signaling pathway is associated with chemotherapeutic drug resistance in pancreatic cancer and other tumors (22–24). In addition, there is a crosstalk between the Hh and AR signaling pathways in PCa cells (25,26). Since, however, the role of the Hh signaling pathway in CRPC cells is unclear, we hoped to determine whether it can regulate the drug sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide by interacting with the AR.

The aim of the present study was to assess whether PLCε and/or GANT61 can increase the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide, and determine the interaction mechanism among PLCε, Gli and AR, so as to provide a better strategy for the clinical treatment of CRPC. In the present study, the expression of PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2 in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), PCa and CRPC tissues and cells was investigated. The correlation between the PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2 in CRPC tissues and cell lines was also explored. Furthermore, the effect of PLCε on cell proliferation and invasion was assessed in CRPC cell lines, and the sensitivity of EN-R and 22RV1 cells to enzalutamide following the downregulation of PLCε expression was determined using lentiviral-mediated shPLCε and/or treatment with specific Gli inhibitor GANT61. The results showed that the PLCε knockdown inhibits CRPC cell proliferation and invasion and sensitizes CRPC cells to enzalutamide by suppressing the AR expression and nuclear translocation. It was also shown that GANT61 combined with PLCε knockdown significantly sensitized CRPC cells to enzalutamide. These findings may provide a new therapeutic approach for CRPC.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

A total of 30 BPH tissue samples, 64 PCa tissue samples and 27 CRPC tissue samples were obtained from patients who underwent needle biopsy, transurethral resection of the prostate or radical prostatectomy at the Department of Urology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China between April 2010 and September 2015. Complete clinical data were available for all patients. All patients met the EAU guidelines for diagnostic criteria for BPH, PCa and CRPC. All tissue samples were reviewed by a pathologist for the confirmation of BPH or PCa. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China. Informed consent was obtained from the patients or their family members.

Immunohistochemistry assay

All formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue samples were cut into 5-µm-thick sections. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a standard immunoperoxidase staining procedure (anti-PLCε; dilution 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA; anti-Gli-1, dilution 1:200 and anti-Gli-2, dilution 1:150; both were from Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The expression status of immunostaining was reviewed and scored based on the proportion of positive cells and staining intensity by a pathologist. Staining intensity was scored as follows: 0 (no staining); 1 (light yellow); 2 (light brown); 3 (brown); and 4 (deep brown). Immunoreactivity ratio was scored as follows: 0 (0% immunoreactive cells), 1 (<5% immunoreactive cells), 2 (5–50% immunoreactive cells), 3 (>50–75% immunoreactive cells) and 4 (>75% immunoreactive cells). The final immunoreactivity score was defined as the sum of both parameters. Final scores of ≤1 were regarded as negative expression, while scores of ≥2 were regarded as positive.

Cell culture, treatment and transfection

Human PCa cell lines LNCaP and 22RV1 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA), enzalutamide-resistant (EN-R) cells were generated as previously described (27). Briefly, the LNCaP cells, one of the androgen-dependent PCa cell strains, were treated with enzalutamide (10 µM; Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) for at least 6 months. 22RV1 and EN-R cells represent CRPC cells. All the cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; both from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). Lentivirus-shRNA targeting human PLCε (LV-shPLCε, 5′-GGTTCTCTCCTAGAAGCAACC-3′) and the negative control (LV-shNC, 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A PLCε shRNA sequence was inserted into a pGLV3/H1/GFP-Puro lentivirus vector. Puromycin (1 µg/ml) was used to screen the stable cell lines. Fluorescence expression was observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) 3 days after lentiviral infection. The infected cells were cultured for one week for subsequent experiments. The PLC knockdown efficiency was assessed using RT-qPCR and western blot analysis. The human Gli-1 and Gli-2 expression plasmids ad-Gli1 and ad-Gli2 containing full-length of Gli-1, Gli-2 and control vectors Gli1-NC, Gli2-NC were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. Transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Other reagents used in the present study were as follows: Lipopolysaccharides (LPS; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), GANT61 (MedChemExpress Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) and reverse transcription was performed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Takara Bio, Inc.). RT-qPCR was performed on a CFX Connect qPCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) with the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). The primer sequences used were as follows: PLCε (sense), 5′-GCAACTACAACGCTGTCATGGAG-3′ and PLCε (antisense), 5′-GCAACTACAACGCTGTCATGGAG-3′; Gli-1 (sense), 5′-ATCCTTACCTCCCAACCTCTGT-3′ and Gli-1 (antisense), 5′-AACTTCTGGCTCTTCCTGTAGC-3′; Gli-2 (sense), 5′-CGGTGTAGGCAGAGCTGATG-3′ and Gli-2 (antisense), 5′-CCACAAGGCAGAAACACCAA-3′; Smo (sense), 5′-CTCCTACTTCCACCTGCTCAC-3′ and Smo (antisense), 5′-CAAAACAAATCCCACTCACAGA-3′; β-actin (sense), 5′-TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG-3′ and β-actin (antisense), 5′-CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAGG-3′. The RT-qPCR comprised an initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, and then 45 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The mRNA expression levels were calculated using the comparative 2−ΔΔCq method (28), with β-actin as a calibrator. All gene expression experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated using the CCK-8 assay. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2,000 cells/well), and incubated at 37°C for 12 h, and then cultured with the different treatment agents in each 5 replicate wells. CCK-8 reagent (10 µl; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was added into each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Optical density was detected using a microplate reader at the absorbance of 450 nm. Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of enzalutamide in the cells was calculated by the CCK-8 assay. The pretreated cells were seeded into 96-well plates (4,000 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. Different concentrations (0.2–640 µM) of enzalutamide were added to the cells in each 3 replicate wells for 24 h, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Merck KGaA) was used as the control. According to the research of Gonnissen et al (29), GANT61 inhibited the survival rate of 22RV1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (from 1 to 50 µM), but the survival rate was significantly inhibited at a concentration of 10 µM. Considering the cytotoxicity, the concentration of 10 µM was chosen for the present study.

Transwell invasion assay

For the Transwell invasion assay, 1×104 cells were plated in serum-free medium in the upper chamber with a Matrigel-coated membrane, and the lower chamber was filled with medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Following 48 h of incubation, the cells at the lower chamber inserts were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and 4% formaldehyde (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room temperature for 15 min. After removing the membrane, the number of cells was counted under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Colony formation assay

The cells were plated in 6-well plates (400 cells/well), and the medium was refreshed every 3 days. Following culture for 14 days, the cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and then stained with 0.05% crystal violet solution for 20 min. The number of colonies was counted under a light microscope.

Western blot assay

The total protein of cells was extracted using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor PMSF and phosphatase inhibitors NaF and Na3VO4 (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit. The isolated proteins (50 µg per lane) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (10 or 12%) electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes was immersed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with Tween-20 blocking solution containing 5% non-fat milk for 2 h, and then incubated with the primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The membranes were then incubated with a goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (dilution 1:2,000; cat. no. TA130015; OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) or a goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (dilution 1:2,000; cat. no. TA130001; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) for 1 h at 37°C. The enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) kit was purchased from Merck Millipore. The intensity level of each protein band was quantified using Image-Pro plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). The following antibodies were used: PLCε (dilution 1:300; cat. no. sc28402; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), STAT3 (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. ab119352; Abcam), p-STAT3 (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. ab32143; Abcam), Gli-1 (dilution 1:500; cat. no. ab49314; Abcam), Gli-2 (dilution 1:500; cat. no. ab26056; Abcam), Smo (dilution 1:500; cat. no. ab113438; Abcam) and AR (dilution 1:500; cat. no. sc7305; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Immunofluorescence

EN-R cells (1.0×105 cells/well) were seeded on sterile glass coverslips and incubated for 48 h, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and incubated with anti-AR primary antibody overnight at 4°C. They were then cultured with a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (dilution 1:2,000; cat. no. TA130015; OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) for 45 min in the dark at room temperature, and nuclei were stained with 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Immunofluorescent images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification of ×400.

Animal xenograft model

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). Twelve male castrated athymic nude mice aged 4 weeks (BALB/c; Beijing Huafukang Bioscience Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) weighing 18–20 g were raised in a cabinet with laminar air flow under pathogen-free conditions in a humidity- and temperature-controlled environment with a 12 h light/dark schedule. The mice had ad libitum access to food and water. Prior to the study initiation, the mice were allowed to acclimatize for 1 week. Then the mice were injected subcutaneously with 2×106 EN-R (Cont group) or LV-shPLCε EN-R (LV-shPLCε group) cells (suspended in 0.1 ml Matrigel) into the right flank area. The animals were then divided into four groups: The Cont+PBS, the LV-shPLCε+PBS, the Cont+Enz and the LV-shPLCε+Enz (3 mice per group). A week later, the mice were treated with vehicle phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or enzalumatide at 10 mg/kg by oral gavage (5 days on and 2 days off) up to 32 days treatment. The tumor growth was monitored every 5 days and the tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: Volume (mm3) = 1/2 × length × width2. At the end of the experiment or when the tumor volume exceeded 1,000 mm3, the mice were euthanized with cervical dislocation and the tumors were collected and measured. The following animal humane endpoints were established: tumors exceeding 10% of the body weight of mice, tumors that became festered and infected, and mice that could not eat and drink water on their own. Mice were euthanized when these humane endpoints occurred.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to process data. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data from two groups were analyzed by unpaired t-test and >2 groups were analyzed by one-way and two-way ANOVA with post hoc contrasts by the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) method. For the data of characteristics of the patient groups, Mann-Whitney test for 2 independent variables was used; Chi-square test was used for trend for the number of rows or columns >2; McNemar's test was used to compare the differences between the matched categorical variables; Pearson's Chi-square test was used for 2 groups of independent variables. Progressive-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Correlation curve analysis for PLCε protein vs. corresponding Gli1 and Gli2 protein in CRPC specimens was conducted using Pearson's linear correlation analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Inhibition of PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2 suppresses the proliferation and invasion of CRPC cells

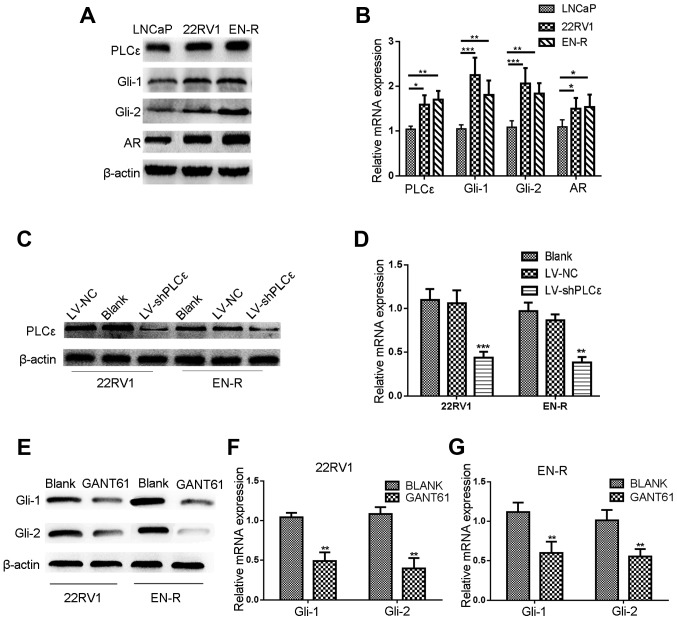

Western blot analysis and RT-qPCR were performed to investigate the protein expression and mRNA levels of PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2 in the LNCaP, 22RV1 and EN-R cells. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, PLCε was highly expressed in the three cell lines. Gli-1/Gli-2 was highly expressed in 22RV1 and ENR cells, but slightly expressed in the LNCaP cells. The expression of AR was also found to be higher in the 22RV1 and EN-R cells, as compared with the LNCaP cells.

Figure 1.

Lentivirus-shPLCε and GANT61 inhibit the protein and mRNA expression level of PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2. (A) PLCε was highly expressed in the PCa (LNCaP) and CRPC (22RV1 and EN-R) cell lines. Gli-1/Gli-2 and AR expression levels were higher in CRPC (22RV1 and EN-R) cells compared to PCa (LNCaP) cells as shown by western blotting. (B) The mRNA expression levels of PLCε, Gli-1/Gli-2 and AR in LNCap, 22RV1 and EN-R cells were detected by RT-qPCR (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001). (C) PLCε knockdown was induced by transfecting lentivirus (LV)-shPLCε into CRPC cell line. Total cellular proteins were detected by western blotting. (D) Relative PLCε mRNA expression level was determined by RT-qPCR. β-actin was used as an internal control (**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with the blank control). (E-G) GANT61 inhibited the protein and mRNA expression level of Gli-1/Gli-2. β-actin was used as an internal control (**P<0.01 compared with the blank control). PLCε, phospholipase Cε; Gli, glioma-associated homolog; PCa, prostate cancer; CRPC, castration-resistant PCa; EN-R, enzalutamide-resistant cell line; AR, androgen receptor; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

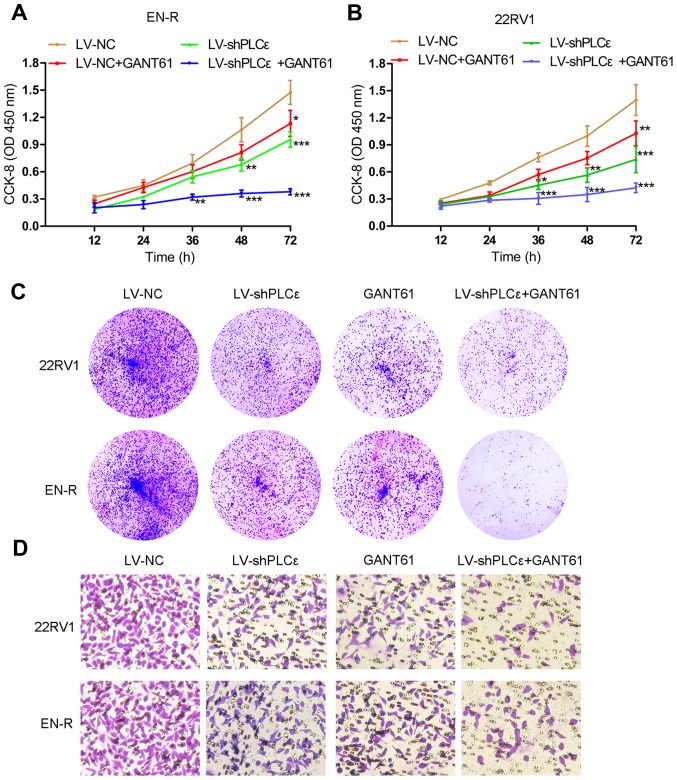

As previously described (12,13), PLCε knockdown inhibits the proliferation and invasion of PCa cells, but whether it has the same inhibitory effect on CRPC cells remains unknown. GANT61, a specific Gli inhibitor, has been reported to suppress the growth of tumor cells by inhibiting the expression of Gli-1/Gli-2 (29,30). To determine the effect of targeting PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2 on the proliferative and invasive capacity of 22RV1 and EN-R cells, lentivirus-shPLCε (LV-shPLCε) was used to knock down PLCε (Fig. 1C and D). Meanwhile, GANT61 (10 µM) was used to inhibit the expression of Gli-1/Gli-2 in 22RV1 and EN-R cells (Fig. 1E-G). CCK-8 and colony formation assays showed that PLCε knockdown and GANT61 treatment suppressed the proliferation of the 22RV1 and EN-R cells. The combination of PLCε knockdown and GANT61 enhanced the inhibitory effect (Fig. 2A-C). Accordingly, Transwell assay showed that PLCε knockdown and GANT61 treatment inhibited the invasion of the 22RV1 and EN-R cells. The combination of PLCε knockdown and GANT61 enhanced the inhibitory effect (Fig. 2D). These findings indicated that PLCε knockdown and Gli-1/Gli-2 inhibition suppressed cell proliferation and invasion in CRPC cells.

Figure 2.

PLCε knockdown and Gli-1/Gli-2 inhibition suppress cell proliferation and invasion in CRPC cells. (A and B) The cell viability of EN-R and 22RV1 cells was assessed by CCK-8 assay following treatment with LV-shPLCε and/or GANT61 10 µM for 72 h (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, compared to LV-NC at the same time-points). (C) Colony forming efficiency of 22RV1 and EN-R cells detected by colony forming assay following treatment with LV-shPLCε and/or GANT61 10 µM. (D) The invasive ability of the 22RV1 and EN-R cells following treatment with LV-shPLCε and/or GANT61 10 µM for 72 h (magnification, ×400) was evaluated by Transwell assay. PLCε, phospholipase Cε; Gli, glioma-associated homolog; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; EN-R, enzalutamide-resistant cell line; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8.

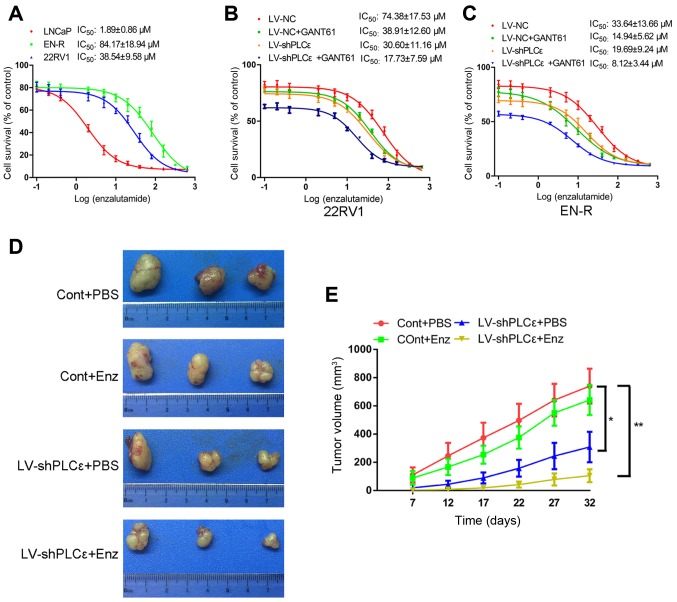

Inhibition of PLCε sensitizes CRPC cells to enzalutamide in vitro

It is well known that AR amplification is responsible for CRPC. As previously mentioned, the knockdown of PLCε inhibited the expression of AR in PCa cells. The inhibition of Gli has been shown to regulate the activity of AR, rather than its expression (25). However, whether PLCε knockdown or Gli inhibition regulates the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide by interacting with the AR signaling pathway remains unclear. We therefore hypothesized that the knockdown of PLCε and inhibition of Gli-1/Gli-2 could sensitize CRPC cells to enzalutamide. To test this, the IC50 value of enzalutamide for the LNCaP, 22RV1and EN-R cells was determined by CCK-8 assay, as 1.89±0.86, 38.54±9.58 and 84.17±18.94 µM, respectively (Fig. 3A). The IC50 value was detected again in 22RV1and EN-R cells following treatment with LV-shPLCε, GANT61 10 µM or combination treatment. The data showed that, although both LV-shPLCε and GANT61 reduced the IC50 value of enzalutamide to varying degrees, the combination treatment significantly decreased the IC50 value of 22RV1 and EN-R cells, as compared to either single treatment (Fig. 3B and C). These data indicated that PLCε knockdown and Gli-1/Gli-2 inhibition could sensitize CRPC cells to enzalutamide in vitro.

Figure 3.

PLCε knockdown sensitizes CRPC cells to enzalutamide in vitro and in vivo. (A) LNCaP, 22RV1and EN-R cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of enzalutamide for 48 h, and the IC50 was determined by CCK-8 assay. (B and C) 22RV1 and EN-R cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of enzalutamide for 48 h, and the IC50 of 22RV1 and EN-R cells following treatment with LV-shPLCε and/or GANT61 10 µM was determined by CCK-8 assay. (D) Tumors sizes. (E) Dynamic growth of implanted tumors in mice (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). PLCε, phospholipase Cε; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; EN-R, enzalutamide-resistant cell line; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; Enz, enzalutamide.

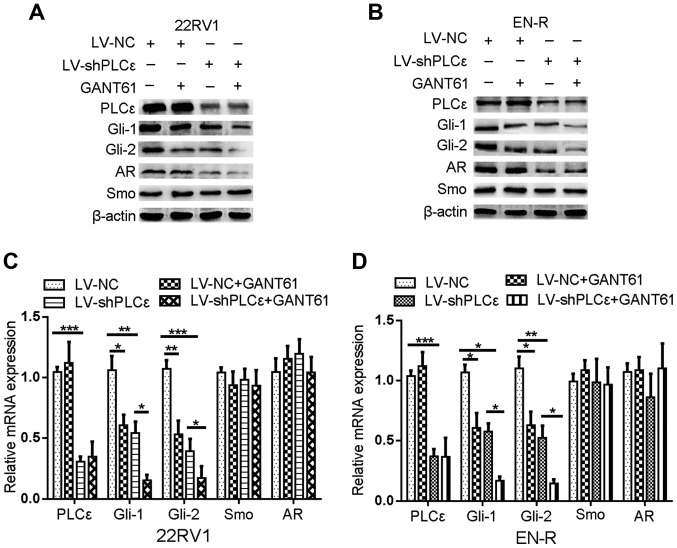

PLCε knockdown inhibits the expression of Gli-1/Gli-2 through the non-canonical Hh signaling pathway in CRPC cells

As described above, the increase in PLCε expression was positively correlated with an increase in Gli-1/Gli-2 expression in PCa and CRPC tissue samples. In addition, PLCε knockdown or inhibition of Gli-1/Gli-2 expression had a similar inhibitory effect on cell proliferation and invasion in the 22RV1 and EN-R cells. Both helped sensitize 22RV1 and EN-R cells to enzalutamide in vitro. We therefore, hypothesized that there is an interaction between PLCε and Gli-1/Gli-2. In order to determine that interaction, western blot analysis and RT-qPCR were performed. PLCε knockdown inhibited the mRNA and protein expression levels of Gli-1/Gli-2, while their inhibition did not affect the expression of PLCε in 22RV1 and EN-R cells, suggesting that PLCε is the upstream regulator of Gli-1/Gli-2 (Fig. 4). However, following PLCε knockdown, Smo (upstream regulatory gene of Gli in the classical Hh signaling pathway) showed no significant mRNA and protein expression change (Fig. 4). These data indicated that PLCε knockdown inhibited the expression of Gli-1/Gli-2 through the non-canonical Hh signaling pathway.

Figure 4.

PLCε knockdown inhibits the expression of Gli-1/Gli-2. (A and B) The expression of PLCε, Gli-1, Gli-2, AR and Smo in 22RV1 and EN-R cells was examined by western blotting. The cells were treated with LV-shPLCε and/or GANT61 10 µM for 72 h. β-actin served as a loading control. (C and D) The relative mRNA expression of PLCε, Gli-1, Gli-2, AR and Smo in 22RV1 and EN-R cells was examined by RT-qPCR (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001). PLCε, phospholipase Cε; Gli, glioma-associated homolog; AR, androgen receptor; Smo, smoothened; EN-R, enzalutamide-resistant cell line; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

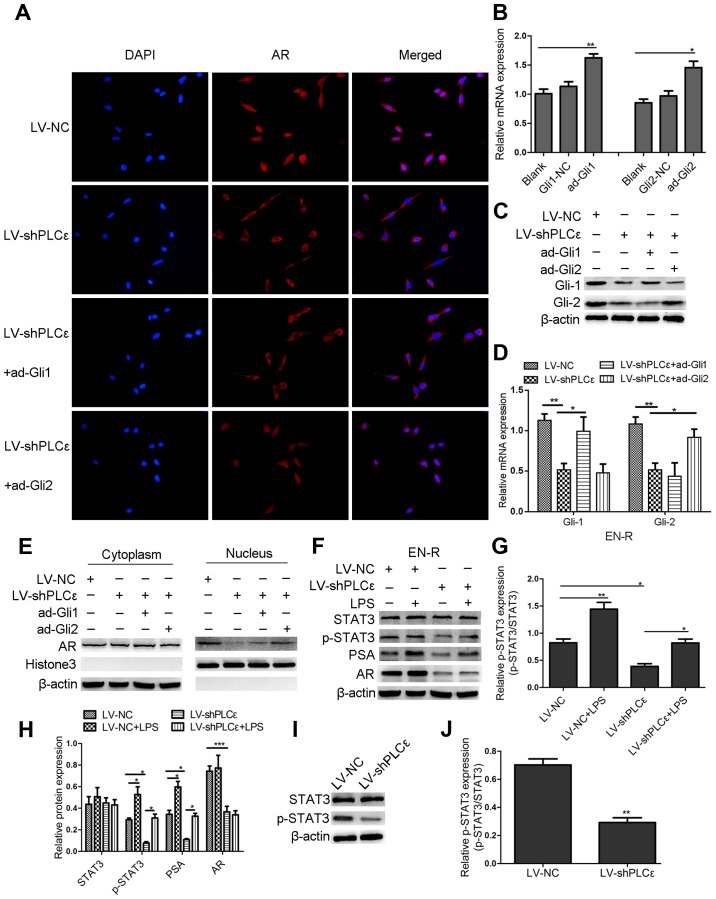

PLCε knockdown increases the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide by suppressing AR expression and nuclear translocation via different signaling pathways

To further investigate the mechanism by which PLCε increases the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide, the effect of PLCε on AR expression and subcellular localization in EN-R cells was assessed using immunofluorescence and western blotting. It was found that PLCε knockdown inhibited AR translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Fig. 5A). Next, the overexpression of plasmid ad-Gli1and ad-Gli2 was used to overexpress Gli-1 and Gli-2 in EN-R cells (Fig. 5B-D). Of note, it was found that the AR nuclear translocation was significantly increased in the LV-shPLCε+ad-Gli2 group compared to the LV-shPLCε+ad-Gli1 group (Fig. 5A). In addition, the cytoplasmic vs. nuclear distribution of AR in EN-R cells was examined using western blot analysis. The data showed that AR expression was decreased in the nucleus following PLCε knockdown, while the overexpression of Gli-2 reversed this effect (Fig. 5E), indicating that PLCε knockdown suppressed AR nuclear translocation via the Gli-2/AR signaling pathway.

Figure 5.

PLCε knockdown suppresses AR expression and nuclear translocation via different signaling pathways. (A) Immunofluorescence demonstrated AR intracellular distribution at 48 h following infection with LV-shPLCε and ad-Gli1/ad-Gli2 in EN-R cells. Magnification, ×400. PLCε knockdown inhibited AR nuclear translocation in EN-R cells. However, the overexpression of Gli-2 reversed the inhibitory effect produced by PLCε. (B) The relative mRNA expression level of Gli-1 and Gli-2 following treatment with an overexpression plasmid of ad-Gli1, ad-Gli2 was examined by RT-qPCR and β-actin served as loading control (NC stands for empty vector plasmid group (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). (C) Protein expression level of Gli-1 and Gli-2 following treatment with the overexpression plasmid of ad-Gli1, ad-Gli2 and PLCε knockdown. (D) The mRNA expression level of Gli-1 and Gli-2 following treatment with overexpression plasmid of ad-Gli1, ad-Gli2 and PLCε knockdown (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). (E) Western blotting showed that PLCε knockdown significantly decreased the AR expression in the nucleus. However, the expression of AR in the nucleus increased following Gli-2 overexpression. (F-H) Western blotting indicated that PLCε knockdown inhibited the PSA expression via the p-STAT3 signaling pathway (The results are represented as the mean ± SD; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001). (I and J) Western blotting showed that the downregulation of PLCε decreased the p-STAT3 protein expression in EN-R cells (The results are represented as the mean ± SD; **P<0.01). PLCε, phospholipase Cε; AR, androgen receptor; Gli, glioma-associated homolog; EN-R, enzalutamide-resistant cell line.

The data also showed that the knockdown of PLCε inhibited the protein expression of AR but not its mRNA expression. However, the inhibition of the Gli-1/Gli-2 expression by GANT61 did not lead to any significant change in the AR mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 4). We also found that the protein expression of phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) was decreased following PLCε knockdown in EN-R cells, but there was no obvious change in the total STAT3 (t-STAT3) protein expression (Fig. 5I and J). We therefore hypothesized that PLCε affects the expression of AR through p-STAT3 signaling. To verify the role of the p-STAT3 signaling pathway and in the regulation of AR, LPS a p-STAT3 agonist, were used to activate p-STAT3. The data showed that the expression of p-STAT3 was activated by LPS, and that the activated p-STAT3 increased the expression of AR target gene PSA, rather than that of AR. PLCε knockdown inhibited the expression of p-STAT3 and PSA protein (Fig. 5F-H). These findings indicated that the knockdown of PLCε inhibited the PSA expression via the p-STAT3 signaling pathway.

PLCε inhibition sensitizes CRPC cells to enzalutamide in vivo

The role of LV-shPLCε in the sensitivity to enzalutamide in EN-R-derived tumors was also examined in vivo. Castrated nude mice were injected subcutaneously with 2×106 EN-R (Cont group) or LV-shPLCε EN-R cells (LV-shPLCε group) into the right flank area and then divided into four groups: Cont+PBS, LV-shPLCε+PBS, Cont+Enz and LV-shPLCε+Enz (n=3 per group). According to the research of Guerrero et al (31), 10 and 50 mg/kg of enzalutamide significantly inhibited the volume in a mouse LNCaP-AR xenograft model. Considering the toxicity of drugs, the dose of 10 mg/kg enzalutamide was chosen for animal experiments. The mice were treated with vehicle PBS or enzalutamide at 10 mg/kg by oral gavage (5 days on, 2 days off). The mice were then sacrificed, and tumors were collected and measured. No animal was sacrificed due to reaching humane endpoints. No mice were found to exhibit multiple tumors. The largest diameter of the tumors was 1.5 cm. As shown in Fig. 3D and E, no significant difference was identified in the tumor volume between the Cont+PBS and the Cont+Enz groups. The tumor volume in the LV-shPLCε+PBS group was smaller than that of the Cont+PBS and Cont+Enz groups. In addition, the LV-shPLCε+Enz group exhibited the smallest tumor volume of the four groups. These results suggested that PLCε knockdown inhibited the tumor growth of the EN-R cell xenografts and contributed to the sensitization of CRPC cells to enzalutamide in vivo.

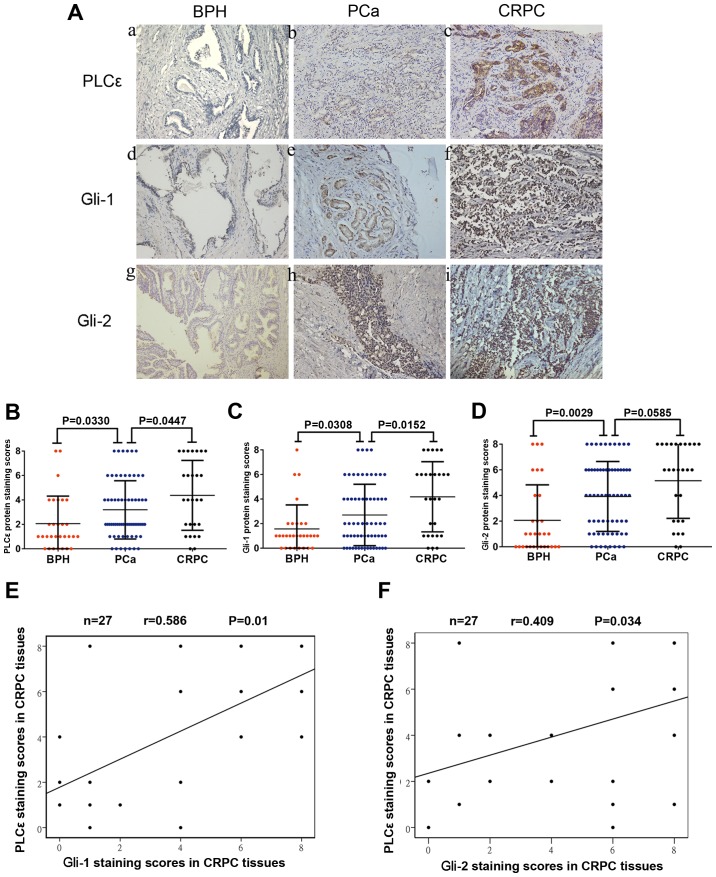

Increased PLCε expression contributes to unfavorable disease phenotype and poor outcome of patients with PCa

A total of 30 BPH samples, 64 PCa and 27 CRPC samples were collected (Table I). The expression of PLCε was detected in the BPH, PCa and CRPC tissues by immunohistochemistry. A high expression of PLCε was identified in most PCa (49/64) and CRPC (21/27) tissue samples. By contrast, none of the BPH tissues stained positive for PLCε (Fig. 6A). Noticeably, the expression of PLCε in the CRPC tissues was significantly higher than that in the PCa tissues (P=0.0447; Fig. 6B). It was also observed that the expression of Gli-1 and Gli-2 in the tumor (PCa and CRPC) tissues was significantly higher than that in the benign (BPH) tissues (Fig. 6A, C and D). Interestingly, the expression of Gli-1, but not Gli-2, in the CRPC tissues was significantly upregulated, as compared to that in the PCa tissues (P=0.152; Fig. 6C). In addition, Pearson's linear correlation results showed that PLCε expression was positively correlated with Gli-1 (r=0.581, P=0.01; Fig. 6E) and Gli-2 expression (r=0.409, P=0.034; Fig. 6F).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the PCa patients.

| PLCε | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics Total number | Overall n=64 | Negative 15/64 (23%) | Positive 49/64 (77%) | P-value |

| Age, years | 0.405 | |||

| Median | 69 | 65 | 70 | |

| Quartiles 25–75 | 59–74 | 58–74 | 60–75 | |

| PSA ng/ml | 0.108 | |||

| Median | 47.41 | 82.14 | 38.46 | |

| Quartiles 25–75 | 23.70–89.89 | 31.18–144.35 | 21.44–86.39 | |

| Histological stage, n (%) | 0.028a | |||

| Ta-T1 | 27 (42%) | 10 (67%) | 17 (35%) | |

| T2-T4 | 37 (58%) | 5 (33%) | 32 (65%) | |

| Gleason score, n (%) | 0.053 | |||

| <7 | 21 (33%) | 8 (53%) | 13 (27%) | |

| ≥7 | 43 (67%) | 7 (47%) | 36 (73%) | |

| Bone metastases, n (%) | 0.147 | |||

| Yes | 25 (39%) | 6 (40%) | 19 (39%) | |

| No | 39 (61%) | 9 (60%) | 30 (61%) | |

Statistically significant. PCa, prostate cancer; PLCε, phospholipase Cε; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Figure 6.

Increased PLCε expression in PCa and CRPC tissues is associated with Gli-1/Gli-2 expression. (A) Immunohistochemical staining in prostate tissues. Magnification, ×200. (a, d and g) BPH tissues. (b, e and h) PCa tissues. (c, f and i) CRPC tissues. (B-D) Average staining scores for PLCε, Gli-1 and Gli-2 in BPH, PCa and CRPC tissues. (E and F) Correlation curve analysis for PLCε vs. Gli-1/Gli-2 staining scores in CRPC tissues. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. PLCε, phospholipase Cε; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; PCa, prostate cancer; CRPC, castration-resistant PCa; Gli, glioma-associated homolog.

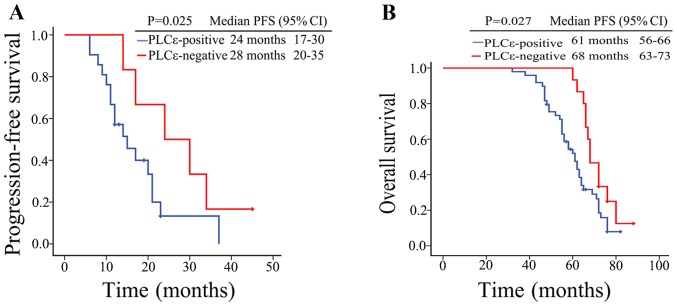

To investigate the effects of PLCε on the disease phenotype and patient clinical outcome in PCa and CRPC, the association between various clinical parameters and the PLCε expression in PCa and CRPC tissues was analyzed. On the one hand, it was found that the PLCε expression was positively correlated with the tumor histological stage of the PCa patients (P=0.028; Table I) and bone metastasis of the CRPC patients (P=0.030; Table II). On the other hand, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis results showed that the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 24 months (95% CI, 17–30 months) in the PLCε-positive CRPC patients, while the median PFS was 28 months (95% CI, 21–35 months) in the PLCε-negative patients; PLCε positivity in the CRPC tissues was associated with a shorter PFS in the CRPC patients (P=0.025; Fig. 7A). Similarly, the overall survival (OS) of PCa patients with a negative PLCε expression was significantly longer than that of PCa patients with a positive PLCε expression (P=0.027; Fig. 7B). These findings revealed that high PLCε expression contributes to unfavorable disease phenotype and poor outcomes in patients with PCa.

Table II.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the CRPC patients.

| PLCε | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics Total number | Overall n=27 | Negative 6/27 (22%) | Positive 21/27 (78%) | P-value |

| Age, years | 0.884 | |||

| Median | 71 | 73 | 70 | |

| Quartiles 25–75 | 65–77 | 65–78 | 66–79 | |

| PSA ng/ml | 0.726 | |||

| Median | 32.23 | 28.26 | 32.24 | |

| Quartiles 25–75 | 16.76–56.18 | 16.13–58.32 | 24.90–58.12 | |

| Bone metastases, n (%) | 0.030a | |||

| Yes | 15 (56%) | 1 (17%) | 14 (67%) | |

| No | 12 (44%) | 5 (83%) | 7 (33%) | |

Statistically significant. CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; PLCε, phospholipase Cε; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Figure 7.

Increased PLCε expression in PCa and CRPC tissues is linked to poor prognosis. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the PFS of 27 patients with CRPC (21 PLCε-positive, 6 PLCε-negative patients). (B) Overall survival cumulative Kaplan-Meier analysis for PCa patients (49 PLCε-positive and 15 PLCε-negative patients). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. PLCε, phospholipase Cε; PCa, prostate cancer; CRPC, castration-resistant PCa; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

As a member of the PLC family, PLCε does not only have typical catalytic domains XY and C2, but also a carboxyl-terminated Ras domain RA and amino acid guanylate exchange factor domain CDC25 (32,33). These special domains can activate multiple signaling pathways and promote the development of malignant tumors. Current experimental and clinical data suggest that PLCε may play a pivotal role in the regulation of the development and progression of different types of cancer, such as skin cancer (10), lung cancer (34), gastric cancer and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (35,36). We previously investigated the expression level of PLCε in bladder cancer and renal cell carcinoma using immunohistochemistry. It was found to be significantly higher than that in normal tissue, suggesting that PLCε is closely associated with the occurrence and development of renal cell carcinoma and bladder cancer (37,38). Recently, our research (12,13) has shown that the high expression of PLCε is associated with cell proliferation and invasion in PCa. In the present study, it was found that the expression of PLCε was significantly increased in PCa and CRPC, as compared to BPH tissues, and that this high expression was linked to poor prognosis in patients with PCa. PLCε knockdown inhibited the proliferation and invasion of CRPC cells. These results revealed that PLCε is involved in the progression of CRPC and further demonstrated that PLCε is an oncogene, which is consistent with previous literature reports.

The activity of Hh/Gli signaling has been shown to be elevated in PCa (20), and is more intensive in those of metastatic PCa than in specimens of localized-PCa (21). Consistent with these reports, it was found in the present study that Hh/Gli signaling was markedly increased in CRPC, as compared to PCa tissues, suggesting that Hh/Gli signaling plays an important role in the emergence and development of CRPC. In addition, it was found that the increase of PLCε was positively correlated with the increase in Gli-1/Gli-2 expression, and that PLCε knockdown and/or inhibition of Gli-1/Gli-2 using GANT61 inhibited the proliferation and invasion of CRPC cells. PLCε knockdown also interacted with the Hh/Gli signaling pathway by decreasing the mRNA and protein expression of the Hh target genes Gli-1 and Gli-2. However, Smo, the upstream regulatory gene of Gli did not decrease, suggesting that PLCε could be involved in the progression of CRPC cells through the non-canonical Hh/Gli signaling pathway.

Androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) remains the main treatment strategy for PCa patients (39). However, the transition from hormone-sensitive PCa to CRPC is inevitable during treatment. AR amplification is a major mechanism of resistance to ADT (40). Enzalutamide is one of the first-line drugs for the treatment of CRPC; it has not only been shown to potently inhibit the binding of androgens to AR, but also the nuclear translocation and subsequent binding of the AR-ligand complex to DNA, thereby inhibiting the transcription of AR target genes (41). However, enzalutamide resistance can occur within a few months. In the present study, it was found that PLCε knockdown increased the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide, which might be achieved by PLCε knockdown suppressing AR nuclear translocation via the Gli-2/AR signaling pathway, or PLCε knockdown inhibiting the expression of the AR target gene PSA via the p-STAT3 signaling pathway. Although PLCε knockdown decreased the protein expression of AR, we failed to determine the exact mechanism in this study.

GANT61, a specific Gli-1/Gli-2 inhibitor, has been reported to significantly decrease cell survival of PC3 and 22Rv1 cells (29). As a small molecule that blocks the transcription of essential Hh proteins, GANT61 has a broad spectrum of potential mechanisms (either through the specific inhibition of Hh signaling or not) by which it can elicit anticancer effects, as it targets many of the ‘classical hallmarks of cancer’ (42). In present study, GANT61 was shown to not only suppress proliferation and invasion in CRPC cells, but also sensitize CRPC cells to enzalutamide, suggesting that GANT61 may be a novel adjuvant drug for use in the treatment of CRPC. However, the potential mechanism of sensitization is unclear. Although it was demonstrated herein that downregulation of Gli-2, rather than Gli-1, inhibited AR translocation, that inhibition did not affect AR expression, which was consistent with a previous study on androgen-independent PCa cells (25). It was therefore deduced that GANT61 restored the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide not only via the AR pathway, but also other non-AR pathways, such as cell autophagy. Autophagy is an important mechanism of resistance to enzalutamide in CRPC; GANT61 induces autophagy in cancer cells, and the enhancement of autophagy increases the sensitivity of enzalutamide in CRPC (43,44). Taken together, the signal transduction relationship among PLCε, Gli and AR was that: GANT61 inhibited AR nuclear translocation by inhibiting Gli2, GANT61 also increased the drug sensitivity of enzalutamide through other non-AR signaling pathways. PLCε inhibited the activity of AR axis in three ways. On the one hand, PLCε inhibited AR nuclear translocation by inhibiting the non-classical Hh/Gli-2 signaling pathway. On the other hand, PLCε inhibited the expression of AR target gene PSA by inhibiting the expression of p-STAT3. In addition PLCε inhibited the expression of AR protein, but the mechanism has not been clarified. Certain issues were encountered in this study, including the failure to define the mechanism through which PLCε affects AR protein expression and GANT61 affects drug sensitivity to enzalutamide in CRPC through non-AR pathways. Further research is required to confirm these. In immunohistochemical experiments, the expression status of immunostaining was reviewed and scored based on the proportion of positive cells and staining intensity by pathologist, and the staining intensity was defined as follows: 0 (no staining), 1 (light yellow), 2 (light brown), 3 (brown) and 4 (deep brown) and the immunoreactivity ratio was 0 (0% immunoreactive cells), 1 (<5% immunoreactive cells), 2 (5–50% immunoreactive cells), 3 (>50–75% immunoreactive cells) and 4 (>75% immunoreactive cells). The final immunoreactivity score was defined as the sum of both parameters. However, the lack of positive control is still a limitation of this study.

In combination, the present results showed that PLCε expression and Hh/Gli signaling were excessively activated in the majority of CRPC tissues. PLCε positivity was linked to poor prognosis in patients with PCa. The knockdown of PLCε significantly suppressed CRPC cell proliferation and invasion by reducing Gli-1/Gli-2 expression. More importantly, PLCε knockdown increased the sensitivity of CRPC cells to enzalutamide by suppressing AR nuclear translocation via the Gli-2/AR signaling pathway and inhibiting PSA expression via the p-STAT3 signaling pathway. In addition, the combination of PLCε knockdown and GANT61 significantly sensitized CRPC cells to enzalutamide. Targeting PLCε may therefore serve as a potential treatment strategy for CRPC, and GANT61 may prove to be a promising agent for use in CRPC treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Dingyun Liu, Department of Pathology, Fuling Center Hospital of Chongqing City, Chongqing, China, for providing technical assistance with the immunohistochemistry assays.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81802543).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

WS, XW and CL designed the experiments. WS, LL, ZD and MY collected the specimens and analyzed the clinical data. WS, LL, MY, YG, HC and ZQ conducted the experiments and collected the data. WS and LL co-wrote the manuscript. CL and XW provided technical support of this research project and supervised the progress of the experiments. ZD, ZQ and MY analyzed the statistical data. WS, LL and ZD assembled and designed the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). Informed consent was obtained from the patients or their family members. All animal experiments were approved as well by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du LB, Li HZ, Wang XH, Zhu C, Liu QM, Li QL, Li XQ, Shen YZ, Zhang XP, Ying JW, et al. Analysis of cancer incidence in Zhejiang cancer registry in China during 2000 to 2009. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:5839–5843. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.14.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu M, Ren SC, Sun YH. Current early diagnostic biomarkers of prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:549–554. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.129211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Armstrong C, Zhu Y, Lou W, Gao AC. Niclosamide enhances abiraterone treatment via inhibition of androgen receptor variants in castration resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:32210–32220. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K, de Wit R, Mulders P, Chi KN, Shore ND, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tombal B, Borre M, Rathenborg P, Werbrouck P, Van Poppel H, Heidenreich A, Iversen P, Braeckman J, Heracek J, Baskin-Bey E, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of enzalutamide monotherapy in hormone-naïve prostate cancer: 1- and 2-year open-label follow-up results. Eur Urol. 2015;68:787–794. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, Loriot Y, Sternberg CN, Higano CS, Iversen P, Bhattacharya S, Carles J, Chowdhury S, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:424–433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song C, Hu CD, Masago M, Kariyai K, Yamawaki-Kataoka Y, Shibatohge M, Wu D, Satoh T, Kataoka T. Regulation of a novel human phospholipase C, PLCepsilon, through membrane targeting by Ras. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2752–2757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunney TD, Katan M. PLC regulation: Emerging pictures for molecular mechanisms. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai Y, Edamatsu H, Maeda S, Saito H, Suzuki N, Satoh T, Kataoka T. Crucial role of phospholipase Cepsilon in chemical carcinogen-induced skin tumor development. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8808–8810. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang LD, Zhou FY, Li XM, Sun LD, Song X, Jin Y, Li JM, Kong GQ, Qi H, Cui J, et al. Genome-wide association study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese subjects identifies susceptibility loci at PLCE1 and C20 or f54. Nat Genet. 2010;42:759–763. doi: 10.1038/ng.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Fan Y, Du Z, Fan J, Hao Y, Wang J, Wu X, Luo C. Knockdown of phospholipase Cε (PLCε) inhibits cell proliferation via phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN)/AKT signaling pathway in human prostate cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:254–263. doi: 10.12659/MSM.908109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Wu X, Ou L, Yang X, Wang X, Tang M, Chen E, Luo C. PLCε knockdown inhibits prostate cancer cell proliferation via suppression of Notch signalling and nuclear translocation of the androgen receptor. Cancer Lett. 2015;362:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buonamici S, Williams J, Morrissey M, Wang A, Guo R, Vattay A, Hsiao K, Yuan J, Green J, Ospina B, et al. Interfering with resistance to smoothened antagonists by inhibition of the PI3K pathway in medulloblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:51ra70. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahid M, Jawed A, Mandal RK, Dar SA, Khan S, Akhter N, Haque S. Vismodegib, itraconazole and sonidegib as hedgehog pathway inhibitors and their relative competencies in the treatment of basal cell carcinomas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;98:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shigemura K, Huang WC, Li X, Zhau HE, Zhu G, Gotoh A, Fujisawa M, Xie J, Marshall FF, Chung LW. Active sonic hedgehog signaling between androgen independent human prostate cancer cells and normal/benign but not cancer-associated prostate stromal cells. Prostate. 2011;71:1711–1722. doi: 10.1002/pros.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamichi F, Shigemura K, Behnsawy HM, Meligy FY, Huang WC, Li X, Yamanaka K, Hanioka K, Miyake H, Tanaka K, et al. Sonic hedgehog and androgen signaling in tumor and stromal compartments drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer. Scand J Urol. 2014;48:523–532. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2014.898336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behnsawy HM, Shigemura K, Meligy FY, Yamamichi F, Yamashita M, Haung WC, Li X, Miyake H, Tanaka K, Kawabata M, et al. Possible role of sonic hedgehog and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal cell cancer progression. Korean J Urol. 2013;54:547–554. doi: 10.4111/kju.2013.54.8.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauth M, Bergstrom A, Shimokawa T, Toftgard R. Inhibition of GLI-mediated transcription and tumor cell growth by small-molecule antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8455–8460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonnissen A, Isebaert S, Haustermans K. Hedgehog signaling in prostate cancer and its therapeutic implication. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:13979–14007. doi: 10.3390/ijms140713979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, Dhara S, Gardner D, Maitra A, Isaacs JT, Berman DM, Beachy PA. Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Bieber MM, Teng NN. Hedgehog signaling regulates drug sensitivity by targeting ABC transporters ABCB1 and ABCG2 in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:625–634. doi: 10.1002/mc.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sims-Mourtada J, Izzo JG, Ajani J, Chao KS. Sonic Hedgehog promotes multiple drug resistance by regulation of drug transport. Oncogene. 2007;26:5674–5679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh S, Chitkara D, Mehrazin R, Behrman SW, Wake RW, Mahato RI. Chemoresistance in prostate cancer cells is regulated by miRNAs and Hedgehog pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen M, Feuerstein MA, Levina E, Baghel PS, Carkner RD, Tanner MJ, Shtutman M, Vacherot F, Terry S, de la Taille A, Buttyan R. Hedgehog/Gli supports androgen signaling in androgen deprived and androgen independent prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:89. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen G, Goto Y, Sakamoto R, Tanaka K, Matsubara E, Nakamura M, Zheng H, Lu J, Takayanagi R, Nomura M. GLI1, a crucial mediator of sonic hedgehog signaling in prostate cancer, functions as a negative modulator for androgen receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404:809–815. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du Z, Li L, Sun W, Wang X, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Yuan M, Quan Z, Liu N, Hao Y, et al. HepaCAM inhibits the malignant behavior of castration-resistant prostate cancer cells by downregulating Notch signaling and PF-3084014 (a gamma-secretase inhibitor) partly reverses the resistance of refractory prostate cancer to docetaxel and enzalutamide in vitro. Int J Oncol. 2018;53:99–112. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonnissen A, Isebaert S, McKee CM, Dok R, Haustermans K, Muschel R. The hedgehog inhibitor GANT61 sensitizes prostate cancer cells to ionizing radiation both in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2016;7:84286–84298. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Q, Xu R, Zeng C, Lu Q, Huang D, Shi C, Zhang W, Deng L, Yan R, Rao H, et al. Down-regulation of Gli transcription factor leads to the inhibition of migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells via integrin β4-mediated FAK signaling. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerrero J, Alfaro IE, Gomez F, Protter AA, Bernales S. Enzalutamide, an androgen receptor signaling inhibitor, induces tumor regression in a mouse model of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 2013;73:1291–1305. doi: 10.1002/pros.22674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hicks SN, Jezyk MR, Gershburg S, Seifert JP, Harden TK, Sondek J. General and versatile autoinhibition of PLC isozymes. Mol Cell. 2008;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wing MR, Snyder JT, Sondek J, Harden TK. Direct activation of phospholipase C-epsilon by Rho. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41253–41258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo XP. Phospholipase C epsilon-1 inhibits p53 expression in lung cancer. Cell Biochem Funct. 2014;32:294–298. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Hu N, Wang Z, Yu K, Shu XO, Yuan JM, Zheng W, Dawsey SM, Dong LM, et al. A shared susceptibility locus in PLCE1 at 10q23 for gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:764–767. doi: 10.1038/ng.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smrcka AV, Brown JH, Holz GG. Role of phospholipase Cε in physiological phosphoinositide signaling networks. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1333–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du HF, Ou LP, Song XD, Fan YR, Yang X, Tan B, Quan Z, Luo CL, Wu XH. Nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway is involved in phospholipase Cepsilon-regulated proliferation in human renal cell carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;389:265–275. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X, Ou L, Tang M, Wang Y, Wang X, Chen E, Diao J, Wu X, Luo C. Knockdown of PLCepsilon inhibits inflammatory cytokine release via STAT3 phosphorylation in human bladder cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9723–9732. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharp A, Welti J, Blagg J, de Bono JS. Targeting androgen receptor aberrations in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:4280–4282. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ardiani A, Gameiro SR, Kwilas AR, Donahue RN, Hodge JW. Androgen deprivation therapy sensitizes prostate cancer cells to T-cell killing through androgen receptor dependent modulation of the apoptotic pathway. Oncotarget. 2014;5:9335–9348. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V, Wongvipat J, Smith-Jones PM, Yoo D, Kwon A, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonnissen A, Isebaert S, Haustermans K. Targeting the Hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: Beyond smoothened. Oncotarget. 2015;6:13899–13913. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang X, Deng L, Chen Q, Wang Y, Xu R, Shi C, Shao J, Hu G, Gao M, Rao H, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling pathway impedes cancer cell proliferation by promotion of autophagy. Eur J Cell Biol. 2015;94:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen HG, Yang JC, Kung HJ, Shi XB, Tilki D, Lara PN, Jr, DeVere White RW, Gao AC, Evans CP. Targeting autophagy overcomes enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells and improves therapeutic response in a xenograft model. Oncogene. 2014;33:4521–4530. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.