Abstract

Study Design:

Retrospective database study.

Objective:

To analyze the economic and age data concerning primary and revision posterolateral fusion (PLF) and posterior/transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF/TLIF) throughout the United States to improve value-based care and health care utilization.

Methods:

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was queried by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for patients who underwent primary or revision PLF and PLIF/TLIF between 2011 and 2014. Age and economic data included number of procedures, costs, and revision burden. The National Inpatient Sample database represents a 20% sample of discharges from US hospitals weighted to provide national estimates.

Results:

From 2011 to 2014, the annual number of PLF and PLIF/TLIF procedures decreased 18% and increased 23%, respectively, in the Unites States. During the same period, the number of revision PLF decreased 19%, while revision PLIF/TLIF remained relatively unchanged. The average cost of PLF was lower than the average cost of PLIF/TLIF. The aggregate national cost for PLF was more than $3 billion, while PLIF/TLIF totaled less than $2 billion. Revision burden (ratio of revision surgeries to the sum of both revision and primary surgeries) remained constant at 8.0% for PLF while it declined from 3.2% to 2.9% for PLIF/TLIF.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated a steady increase in PLIF/TLIF, while PLF alone decreased. The increasing number of PLIF/TLIF procedures may account for the apparent decline of PLF procedures. There was a higher average cost for PLIF/TLIF as compared with PLF. Revision burden remained unchanged for PLF but declined for PLIF/TLIF, implying a decreased need for revision procedures following the initial PLIF/TLIF surgery.

Keywords: lumbar, lumbar interbody fusion, low back pain, fusion, spondylolisthesis, trauma, degenerative disc disease

Introduction

Lower back pain affects a large portion of the population with a lifetime prevalence of 60% to 80%1 in the United States. Posterior spinal fusion is considered the gold standard surgical treatment for spondylolisthesis, traumatic lumbar instability, and other clinical situations.2 Although the vast majority of lower back pain is successfully managed with conservative modalities, spinal fusion of the lumbar spine is frequently performed when nonoperative management fails.3 Traditionally, spinal fusion is obtained posterolaterally through intertransverse process decortication and bone grafting with or without instrumentation.2 However, over the past 2 decades, spinal fusion has been performed utilizing an interbody technique, which has improved fusion rates, lowered reoperation rates, and improved clinical satisfaction.4-9

Given the increasing national focus on health care utilization and the delivery of value-based care,4 spine surgeons, administrators, and policy makers can benefit from economic information and data for specific spinal surgical procedures.10,11 The analysis of trends for these procedures over a 4-year period allows for the visualization of patterns and provides insight into the trajectory of spinal fusion procedures in the United States. However, obtaining reliable data in the health care industry remains an opaque process. Accurate, validated data on the frequency of surgical intervention, operative costs, surgical revision rates, and even patient demographics is difficult to obtain, are decentralized, and are highly variable in the literature.12 These limitations make it difficult to compare cost-effectiveness of procedures at a national scale.

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database allows researchers to overcome some of these logistical limitations by providing a broad range of patient demographics, economic data, and number of treatments per year for specific surgeries performed at approximately 1000 hospitals throughout the United States.13 Information that can be organized yearly by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM) codes permits for utilization and demographic comparisons among procedures, while providing necessary data for cost analysis.

By performing a longitudinal analysis of an administrative inpatient database, a better understanding of the yearly trends and economic data surrounding primary and revision posterolateral fusion (PLF) and posterior/transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF/TLIF) is possible. In this study, the NIS database was utilized to analyze a large, national cohort of patients who underwent PLF and PLIF/TLIF procedures from 2011 to 2014. Variables analyzed include the following: overall number of procedures performed, cost, age, and revision burden. We hypothesized that PLF-only procedures would decrease during the study period, while PLIF/TLIF procedures would increase.

Methods

Data Source

Data was collected from the NIS database between 2011 and 2014 across 44 states. The NIS database was developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project and constitutes the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States. The database represents a 20% sample of discharges from US hospitals (excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care hospitals), which is weighted to provide national estimates.

Patient Selection and Characteristics

The NIS database was queried for primary and revision PLF from 2011 to 2014 using ICD-9 CM codes 81.07 and 81.37, respectively. The database was subsequently queried for primary and revision PLIF/TLIF from 2011 to 2014 using ICD-9 CM codes 81.08 and 81.38, respectively. PLIF and TLIF procedures are grouped together under one ICD-9 CM code. There were no additional criteria for patient exclusion. The data in this study was restricted to the years 2011 to 2014 because of revisions to the procedural codes in 2011 and the gradual transition to ICD-10 CM in 2015.

Age and economic data were obtained for both primary and revision PLF and PLIF/TLIF procedures. Insurance types included Medicare, Medicaid, private, uninsured, and other. The “other” category included workman’s compensation, TRICARE/CHAMPUS, CHAMPVA, Title V, and a number of other government programs. The annual number of surgeries, average and aggregate costs (in then-year dollars), insurance type, and patient demographics were recorded. Revision burden was defined as the ratio of revision procedures (removal, revision, supplemental fixation, or reoperation at the index level) to the sum of primary and revision procedures. Aggregate cost was defined as the sum of all costs for all hospital stays in the United States.

Results

Annual Number of Procedures

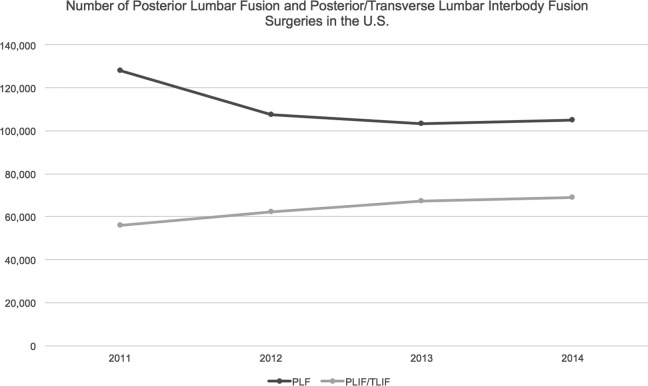

The annual number of PLF surgeries decreased from 127 916 in 2011 to 105 195 in 2014, accounting for an 18% drop over the 4 years. During this same time period, the number of annual PLIF/TLIF procedures increased from 56 001 to 69 030, which represented a 23% increase (Figure 1). The number of revision PLF surgeries decreased nonlinearly by 19%, from 10 717 to 8735, while the number of revision PLIF/TLIF surgeries stayed roughly unchanged at an average of 1884 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Total number of posterior lumbar fusion and posterior lumbar interbody fusion procedures per year.

Figure 2.

Total number of revision posterior lumbar fusion and revision posterior lumbar interbody fusion procedures per year.

Cost of Procedure

The average cost per procedure of PLF, $28 439, was slightly lower than the average cost of PLIF/TLIF procedures, $29 948. This trend persisted for revision procedures as well with an average revision PLF cost of $28 974 and average revision PLIF/TLIF cost of $32 320 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean Cost of Primary and Revision Procedures in the United States From 2011 to 2014.

| Primary | Revision | |

|---|---|---|

| PLF | $28 439 | $28 947 |

| PLIF/TLIF | $29 947 | $32 321 |

Abbreviations: PLF, posterolateral fusion; PLIF/TLIF, posterior/transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

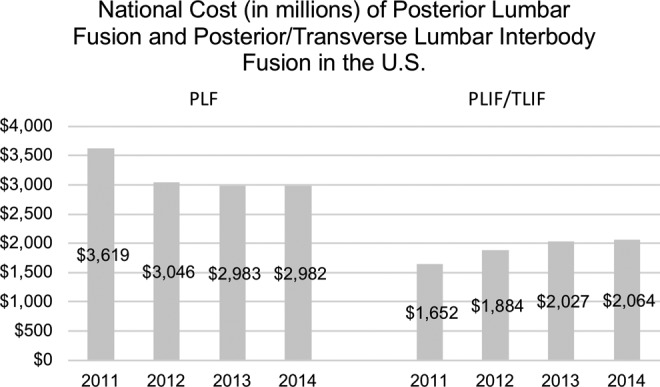

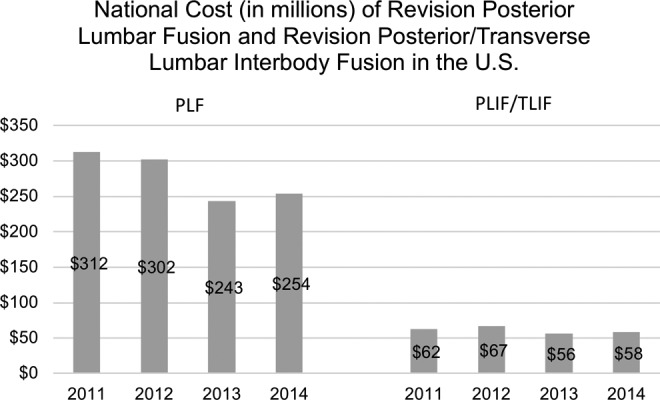

Aggregate National Costs

When considered on a national aggregate scale, primary PLF and primary PLIF/TLIF cost $3 157 791 341 and $1 906 870 045 on average per year, respectively. This corresponded to a 17.6% decrease for PLF and 24.9% increase for PLIF/TLIF over the 4-year period (Figure 3). Aggregate revision PLF costs also decreased by 18.6% from 2011 to 2014, averaging $278 095 018 per year in the nation. The national cost of revision PLIF/TLIF decreased by 6.1% during this period with an average of $60 861 491 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Total estimated costs of posterior lumbar fusion and posterior/transverse lumbar interbody surgeries between 2011 and 2014 across the United States.

Figure 4.

Total estimated costs of revision posterior lumbar fusion and revision posterior/transverse lumbar interbody surgeries between 2011 and 2014 across the United States.

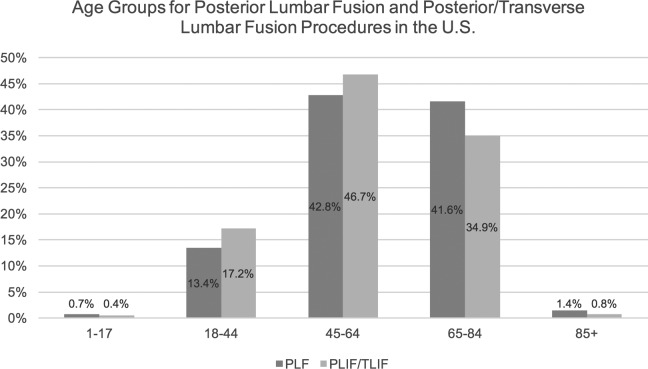

Patient Age

Patients who underwent PLF tended to be older, with patients aged 65 years and older making up a 4-year average of 43% for PLF compared with 35.7% for PLIF/TLIF procedures (Figure 5). More PLIF/TLIF procedures were performed in both the 18 to 44 and 45 to 64 age groups as compared with PLF procedures.

Figure 5.

Age distributions for posterior lumbar fusion and posterior/transverse lumbar interbody fusion procedures in the United States.

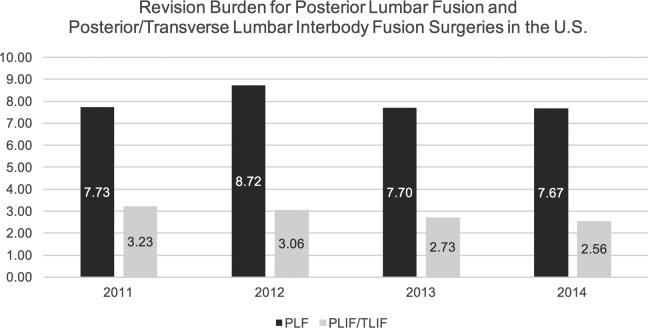

Revision Burden

The revision burden, defined as the ratio of revision surgeries to the sum of both revision and primary surgeries, fluctuated slightly for PLF procedures but remained relatively constant at an average of 8.0% in the United States. Contrastingly, the revision burden for PLIF/TLIF decreased progressively from 3.23 in 2011 to 2.56 in 2014, averaging 2.9% (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Revision burden percentage for posterior lumbar fusion and posterior/transverse lumbar interbody fusion procedures in the United States.

Discussion

Several recently published studies have demonstrated rapidly increasing rates of all methods of spinal fusions in the last 2 decades.14-16 In contrast, the current study reports that the total number of isolated primary and revision PLF procedures in the United States have both decreased by 18% and 19%, respectively. The increase in the number of posteriorly based interbody spinal fusions performed, such as PLIF/TLIF, may be contributing to the decrease in isolated PLF. The current study looks at primary ICD-9 CM codes, which are listed according to the costliest billable procedure. Given the limitations of the database and ICD 9-CM coding, this study focused on patients who had isolated PLF and patients with a posterior-based interbody with or without PLF. This study demonstrated a higher average cost for PLIF/TLIF as compared with PLF.

Despite the reported decrease in PLF procedures in the current study, the mean revision burden in the United States has remained at a relatively constant 8% rate over the study period. The decline in revision surgeries may primarily be due to the decline in primary cases since revision burden has remained constant over the study period. Additionally, the decline in procedures likely accounts for the decreasing aggregate national cost of PLF procedures. Yet these assertions are largely theoretical given that this study was not designed to answer the cause of any potential increase or decrease in utilization.

Similar to prior reports in the literature,14 our analysis demonstrated an increase in the rate of PLIF/TLIF. Pannell et al4 showed that the number of PLIF procedures increased from 4.8 to 7.5 per 10 000 from 2004 to 2009. This data was gathered from a private insurance database, limiting its wider applicability as compared with the NIS database. Our analysis, which included all payer types, showed a 23% increase in PLIF/TLIF procedures over the study period. Interestingly, despite the increase in PLIF/TLIF procedures over the study period, the number of revision procedures was constant, corresponding to a decreasing revision burden, averaging 2.9%. The average revision burden for PLIF/TLIF was much lower than the average revision burden for PLF procedures.

The average yearly national cost of PLIF/TLIF procedures has increased by 25% over the study period. These findings are consistent with several studies demonstrating a similar rise in the cost of spine surgery over the last decade.17 Much of this increase may be attributed to the increasing number of PLIF/TLIF procedures being performed throughout the United States. Furthermore, the increasing cost of interbody fusion procedures is likely multifactorial. This study was not designed to determine the cause of the observed trends. However, more device-based costs likely contribute given the move from Harms mesh cages and allograft to more sophisticated interbodies such as expandable devices, porous metal ingrowth surfaces, and modified polyether ether ketone. Because there is a lower revision burden for interbody procedures, it is possible that this may account for overall national cost savings since less revision procedures need to be performed as compared with traditional PLF procedures. Again, this study was not designed to answer these questions and are merely hypotheses.

Many of the limitations of this study are secondary to intrinsic issues of large patient databases. The NIS database does not include physician-based fees and costs are calculated from hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios, which may exaggerate surgical cases. Still, these hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios have been internally validated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Inherent to a large study, the surgeries were performed by a large variety of surgeons, allowing for differences in surgical technique and potential indication bias. Moreover, there can be potential inaccuracies of ICD-9 CM billing records, errors transferring data from hospital records to administrative records, underreporting of procedures, or exclusion of missing cases in the NIS database. Finally, it is difficult to compare separate procedures as their indications vary. As shown in this study, patients receiving PLF represented an older population as compared with patients receiving PLIF/TLIF. Therefore, these represent 2 separate patient groups, making them incompatible for comparison, despite the overlap in the procedures. These differences also explain the difficulty in performing definitive cost-effectiveness analysis.

Despite these limitations, this study draws strength from its ability to analyze trends on a national scale. As alternative payment models become a more significant mode of reimbursement, cost-effectiveness for posterior spinal fusion surgery develops increasing importance. Another variable to consider is the enactment of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, which went into widespread effect in 2014 and overlapped with this study. It is difficult to determine the impact on cost, number of procedures, and overall trends that national policies have but future studies may be able to elucidate the effects of the Affordable Care Act on spinal procedures. The large fund of information provided by the NIS database will undoubtedly play a critical role in tracking the effects of medical policy changes and evolving spine surgery paradigms on a national basis.

In this analysis of the NIS database, the rate of isolated primary and revision PLF procedures declined while primary PLIF/TLIF increased and revision PLIF/TLIF remained constant. Over the study period, revision burden has remained unchanged for PLF but has declined progressively for PLIF/TLIF, implying a decreased need for revision procedures following the initial PLIF/TLIF surgery. Prospective randomized trials are necessary to more rigorously evaluate the long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness from a national health care perspective.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Asher AL, Speroff T, Dittus RS, et al. The National Neurosurgery Quality and Outcomes Database (N2QOD): a collaborative North American outcomes registry to advance value-based spine care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(22 suppl 1):S106–S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. 2013 Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample. Agency for healthcare research and quality, 2015. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2013.jsp. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- 3. Hu SS, Tribus CB, Diab M, Ghanayem AJ. Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:656–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pannell WC, Savin DD, Scott TP, Wang JC, Daubs MD. Trends in the surgical treatment of lumbar spine disease in the United States. Spine J. 2015;15:1719–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ha KY, Na KH, Shin JH, Kim KW. Comparison of posterolateral fusion with and without additional posterior lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eismont FJ, Norton RP, Hirsch BP. Surgical management of lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Musluman AM, Yilmaz A, Cansever T, et al. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion versus posterolateral fusion with instrumentation in the treatment of low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis: midterm clinical outcomes. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuraishi S, Takahashi J, Mukaiyama K, et al. Comparison of clinical and radiological results of posterolateral fusion and posterior lumbar interbody fusion in the treatment of L4 degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Asian Spine J. 2016;10:143–152. doi:10.4184/asj.2016.10.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghasemi AA. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus instrumented posterolateral fusion in degenerative spondylolisthesis: an attempt to evaluate the superiority of one method over the other. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;150:1–5. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. National trends in the surgical treatment for lumbar degenerative disc disease: United States, 2000 to 2009. Spine J. 2015;15:265–271. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Awe OO, Maltenfort MG, Prasad S, Harrop JS, Ratliff J. Impact of total disc arthroplasty on the surgical management of lumbar degenerative disc disease: analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2000 to 2008. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:139 doi:10.4103/2152-7806.85980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deyo RA. Fusion surgery for lumbar degenerative disc disease: still more questions than answers. Spine J. 2015;15:272–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Epstein NE. Older literature review of increased risk of adjacent segment degeneration with instrumented lumbar fusions. Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7(suppl 3):S70–S76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim S, Hedjri SM, Coyte PC, Rampersaud YR. Cost-utility of lumbar decompression with or without fusion for patients with symptomatic degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Spine J. 2012;12:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmier JK, Halevi M, Maislin G, Ong K. Comparative cost effectiveness of Coflex® interlaminar stabilization versus instrumented posterolateral lumbar fusion for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;6:125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, Bronner KK, Fisher ES. United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992-2003. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2707–2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis RJ, Errico TJ, Bae H, Auerbach JD. Decompression and Coflex interlaminar stabilization compared with decompression and instrumented spinal fusion for spinal stenosis and low-grade degenerative spondylolisthesis: two-year results from the prospective, randomized, multicenter, Food and Drug Administration Investigational Device Exemption trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:1529–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]