Abstract

Background

Flow diversion with the Pipeline embolization device (PED) is a widely accepted treatment modality for aneurysm occlusion. Previous reports have shown no recanalization of aneurysms on long-term follow-up once total occlusion has been achieved.

Case description

We report on a 63-year-old male who had a large internal carotid artery cavernous segment aneurysm. Treatment with PED resulted in complete occlusion of the aneurysm. However, follow-up angiography at four years revealed recurrence of the aneurysm due to disconnection of the two PEDs placed in telescoping fashion.

Conclusion

Herein, we present the clinico-radiological features and discuss the possible mechanisms resulting in the recanalization of aneurysms treated with flow diversion.

Keywords: Aneurysm, flow diverter, Pipeline Embolization Device, recurrence

Introduction

Flow diverters have emerged as devices that promote aneurysm occlusion while preserving the parent artery. The Pipeline Flex Embolization Device (PED, Medtronic-Covidien, Irvine, CA, USA) has been the most widely used flow diverter globally. It prevents recanalization by promoting thrombosis of the aneurysm sac and neointimal overgrowth at the aneurysm neck.1

Previous reports have shown that there was no recanalization on long-term follow-up once total occlusion had been achieved with the PED.2–4 To our knowledge, however, there has been only one reported case of recurrence of a totally occluded aneurysm after treatment with the PED.5 We present a patient who had successful complete occlusion of a large internal carotid cavernous segment aneurysm with PED but recurred after four years of treatment when the telescoped PEDs completely disarticulated.

Case report

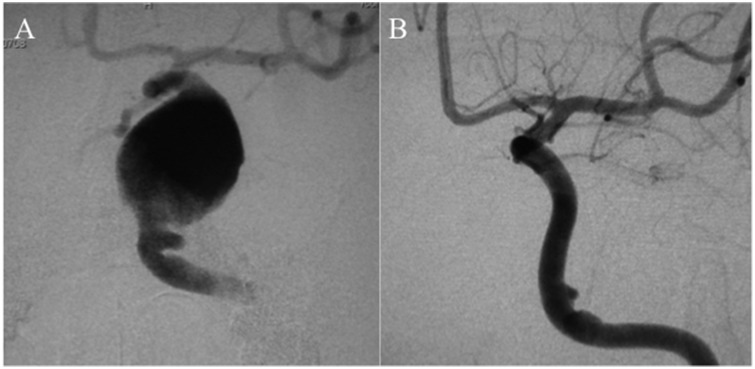

A 63-year-old male presented with progressive diplopia for four years and proptosis of the left eye for one year. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) revealed bilateral internal carotid artery (ICA) cavernous segment aneurysms. We planned for treatment of the left-sided symptomatic aneurysm (Figure 1(a)) first with the PED. The patient was given dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin 100 mg/day and clopidogrel 50 mg/day 10 days prior to the procedure. Under general anesthesia and systemic heparinization, a Medikit 7 Fr sheath (Medikit, Tokyo, Japan) was placed in the right ICA via femoral artery puncture. A Marksman microcatheter (Medtronic/Covidien, Irvine, CA, USA) was navigated far into the middle cerebral artery (MCA) over a 0.014-inch Chikai microguidewire (ASAHI INTECC, Nagoya, Japan). Two PEDs (3.5 mm × 35 mm and 4 mm × 35 mm) were then deployed in telescoping fashion to entirely cover the aneurysm neck. A Hyperform balloon 4 mm × 7 mm (Medtronic-Covidien) was used to perform angioplasty to achieve optimal apposition. Contrast stagnation was immediately observed inside the aneurysm. DSA at one-year follow-up showed total aneurysm occlusion (Figure 1(b)). Then, the right-sided carotid cavernous segment aneurysm was also treated with a flow diverter. DAPT was continued for one year thereafter, i.e. two years from the initial treatment of the left-sided aneurysm. Then, clopidogrel was stopped and aspirin was continued.

Figure 1.

Initial treatment of the left internal carotid artery cavernous segment large aneurysm (a) with two telescoped Pipeline embolization devices, resulting in complete occlusion of the aneurysm (b).

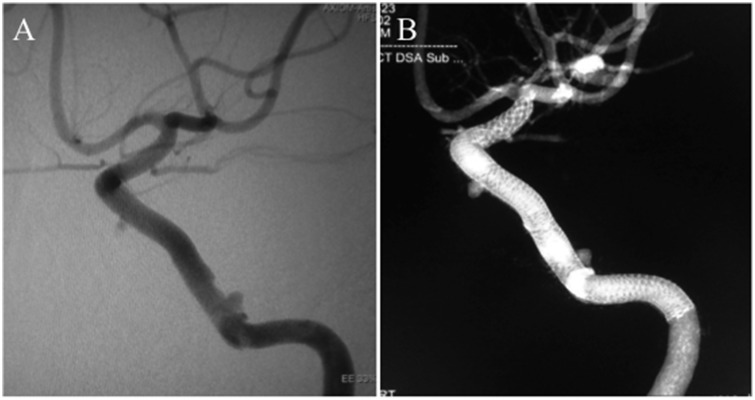

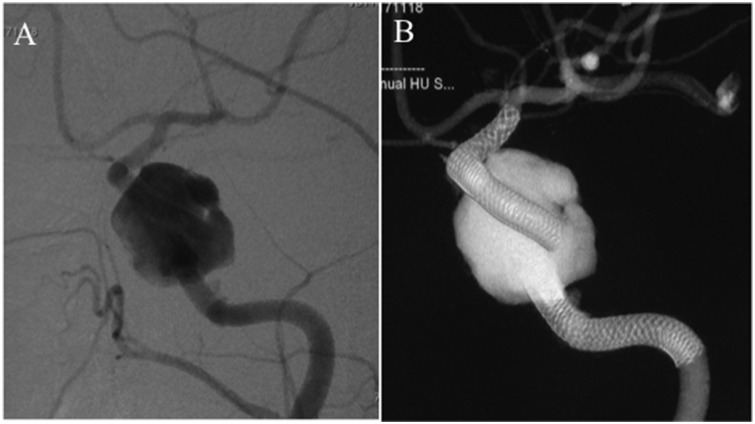

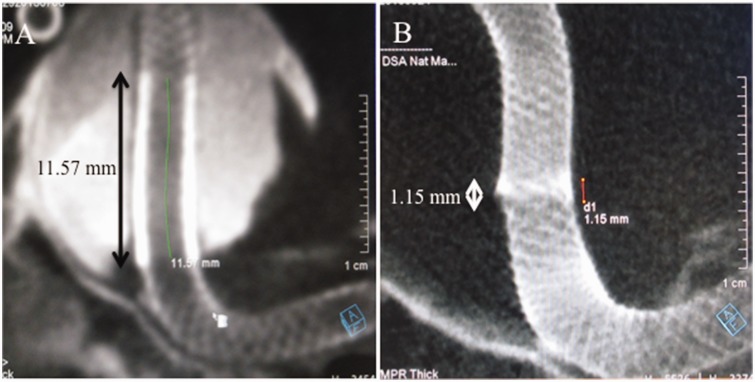

Regular angiographic follow-up for three years after the initial treatment showed no recurrence (Figures 2(a) and (b)); however, the angiography performed after four years revealed recanalization of the left-sided aneurysm. The two PEDs placed in telescoping fashion had disconnected, leaving the aneurysm neck unprotected, which resulted in the recurrence (Figures 3(a) and (b)). The extent of overlap was calculated, which showed that the overlap was 11.57 mm at the initial treatment. At three-year follow-up it was reduced to 1.15 mm. However, at four-year follow-up there was no overlap (Figures 4(a) and (b)). So, we planned to place an additional PED to restore the connection. The patient was again placed on the similar DAPT regimen 10 days prior to the procedure. Using an Axcelguide 6 Fr sheath (Medikit, Tokyo, Japan) and a Navien 5 Fr guiding catheter (Medtronic-Covidien), a Marksman microcatheter was advanced over a 0.014-inch Chikai microguidewire, and one PED sized 4.25 mm × 35 mm was deployed to connect the two detached PEDs (Figure 5(a)). Angioplasty was performed with the TransForm SC 4 mm × 7 mm (Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA). Postprocedure course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the same DAPT regimen. Follow-up angiography after one month showed complete disappearance of the aneurysm (Figure 5(b)). We plan to continue the DAPT regimen for one year and then change to single APT depending on the angiographic findings.

Figure 2.

Follow-up digital subtraction angiography (a) and cone-beam computed tomography (b) at three-year follow-up showing no recurrence of the aneurysm.

Figure 3.

Follow-up digital subtraction angiography (a) and cone-beam computed tomography (b) four years after the initial treatment showing recanalization of the aneurysm due to disconnection of the two Pipeline embolization devices.

Figure 4.

The measurement of the extent of overlap of the two Pipeline embolization devices showing that the length of overlap after the initial treatment was 11.57 mm (a) whereas that at three-year follow-up was reduced to 1.15 mm (b).

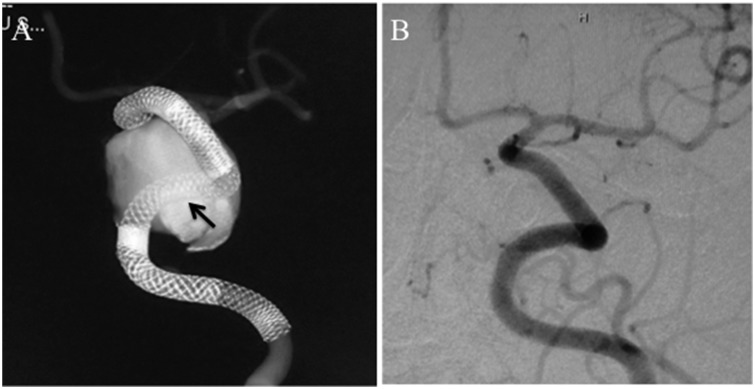

Figure 5.

Retreatment with addition of a Pipeline embolization device (PED, indicated by black arrow) to connect the detached PEDs ((a), cone-beam computed tomography), resulting in complete occlusion of the aneurysm after one month ((b), digital subtraction angiography).

Discussion

PED has been reported to be a safe and durable treatment modality in selected wide-necked large and giant aneurysms compared with traditional embolization techniques. Lylyk et al.1 reported a 95% occlusion rate at one-year angiographic follow-up. A multicenter, single-arm Pipeline for the Intracranial Treatment of Aneurysms study revealed that complete aneurysm occlusion was seen in 28 out of 30 (93.3%) patients at six-month follow-up angiography.3

To date, there has been only one case report of recurrence after successful PED treatment.5 Daou et al4 in their series of 281 patients with long-term follow-up after PED treatment reported that 16.4% of those had residual filling of aneurysms. However, none of the aneurysms with total occlusion recurred during follow-up. Becske and colleagues2 documented no recanalization of completely occluded aneurysms during a long-term follow-up period of five years in their prospective study of 109 complex ICA aneurysms. Lang et al.6 reported continuous growth of an aneurysm treated with the PED. However, computed tomography (CT) angiogram was used as the follow-up tool, which is not the gold standard to assess flow diverters. Therefore, it cannot be ascertained if the aneurysm was completely occluded before the rapid delayed growth occurred.

There have been several hypotheses on the mechanisms behind the regrowth of an aneurysm once it is completely occluded. The accumulation of inflammatory cells in the unorganized thrombus or around the coils can cause chronic inflammation and neovascularization in the aneurysm wall, causing recanalization.7,8 Iihara et al7 histopathologically demonstrated the presence of vasa vasorum in the adventitia of the aneurysm wall, which might be an important factor in persistent aneurysmal enlargement even after complete endovascular occlusion. Nagahiro and colleagues9 suggested that formation of intrathrombotic vascular channels and subsequent establishment of blood flow between the parent artery and channels might play a key role in the growth of thrombosed aneurysms. Schubiger et al10 postulated that recurrent intramural hemorrhages at the highly vascularized wall might give rise to aneurysm growth, based on CT scans and magnetic resonance images.

In our case, we believe the very delayed discontinuation of telescoped PEDs to have caused the recurrence. The mechanism is not known but retraction or shortening of the PEDs might cause the separation of the telescoped PEDs, leading to the missed neck coverage. The extent of overlap of the telescoped PEDS can also contribute to this phenomenon. In case of telescoped PEDs, more than half of the length of the PED should be overlapped to prevent its release. A device with a diameter at least 0.25 mm more should be selected for overlapping. In our case, the extent of overlap of the two PEDs was less than half, which might have been one of the factors in their disarticulation. The reestablishment of vascular channels might also have played a role in the delayed recanalization of the thrombosed aneurysm. These mechanisms can be proposed to explain this unusual finding of recanalization even after three years of successful occlusion.

Although PED has been shown to be a relatively safe and durable treatment modality, some delayed complications have been reported in the literature. These mainly include thromboembolic complications, delayed intracranial hemorrhage and in-Pipeline stenosis.2,4 There have been reports of device foreshortening or retraction uncovering the aneurysmal neck and resulting in recurrence.11,12

Conclusion

We here presented a very rare case with delayed recurrence of a completely occluded aneurysm after successful treatment with the PED. Although flow diversion is being more commonly used for such large, difficult aneurysms, long-term follow-up is mandatory even after successful treatment considering the probability of delayed recurrence.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Hidenori Oishi receives 1 million yen or more annually from Medtronic Japan for attending conferences and giving presentations and 2 million yen or more annually from Medtronic Japan as a scholarship donation to him as an endowed chair of his department. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Lylyk P, Miranda C, Ceratto R, et al. Curative endovascular reconstruction of cerebral aneurysms with the Pipeline embolization device: The Buenos Aires experience. Neurosurgery 2009; 64: 632–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becske T, Brinjikji W, Potts MB, et al. Long-term clinical and angiographic outcomes following Pipeline embolization device treatment of complex internal carotid artery aneurysms: Five-year results of the Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysms trial. Neurosurgery 2017; 80: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson PK, Lylyk P, Szikora I, et al. The Pipeline embolization device for the intracranial treatment of aneurysms trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daou B, Atallah E, Chalouhi N, et al. Aneurysms with persistent filling after failed treatment with the Pipeline embolization device. J Neurosurg. Epub ahead of print 4 May 2018. DOI: 10.3171/2017.12.JNS163090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivelato FP, Ulhôa AC, Rezende MT, et al. Recurrence of a totally occluded aneurysm after treatment with a Pipeline embolization device. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 24 May 2018. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-013842.rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang ST, Assis Z, Wong JH, et al. Rapid delayed growth of ruptured supraclinoid blister aneurysm after successful flow diverting stent treatment. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iihara K, Murao K, Sakai N, et al. Continued growth of and increased symptoms from a thrombosed giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery after complete endovascular occlusion and trapping: The role of vasa vasorum. Case report. J Neurosurg 2003; 98: 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dehdashti AR, Thines L, Willinsky RA, et al. Symptomatic enlargement of an occluded giant carotid-ophthalmic aneurysm after endovascular treatment: The vasa vasorum theory. Acta Neurochir 2009; 151: 1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagahiro S, Takada A, Goto S, et al. Thrombosed growing giant aneurysms of the vertebral artery: Growth mechanism and management. J Neurosurg 1995; 82: 796–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubiger O, Valavanis A, Wichmann W. Growth-mechanism of giant intracranial aneurysms; demonstration by CT and MR imaging. Neuroradiology 1987; 29: 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McTaggart RA, Santarelli JG, Marcellus ML, et al. Delayed retraction of the Pipeline embolization device and corking failure: Pitfalls of Pipeline embolization device placement in the setting of a ruptured aneurysm. Neurosurgery 2013; 72(Suppl 2 Operative): onsE245–onsE250. discussion onsE250–onsE251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heit JJ, Telischak NA, Do HM, et al. Pipeline embolization device retraction and foreshortening after internal carotid artery blister aneurysm treatment. Interv Neuroradiol 2017; 23: 614–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]