Abstract

New sequencing technologies have made it possible to interrogate with unprecedented depth the intrinsic changes experienced by cells as they transit the arena of development. Recently in Cell, Loh, Chen and colleagues investigated early lineage-restricted human mesoderm cell types and their precursors going back to pluripotency (Loh et al., 2016).

Human pluripotent stem cells can offer a window into inaccessible stages of early human development. They also hold the promise of one day providing cells for regenerative medicine. Irving Weismasn’s group (Loh et al, 2016) has recently assembled a transcriptional and chromatin roadmap covering the path to several therapeutically interesting cell types: cardiac and skeletal myocytes, fibroblasts, bone, cartilage and fat progenitors.

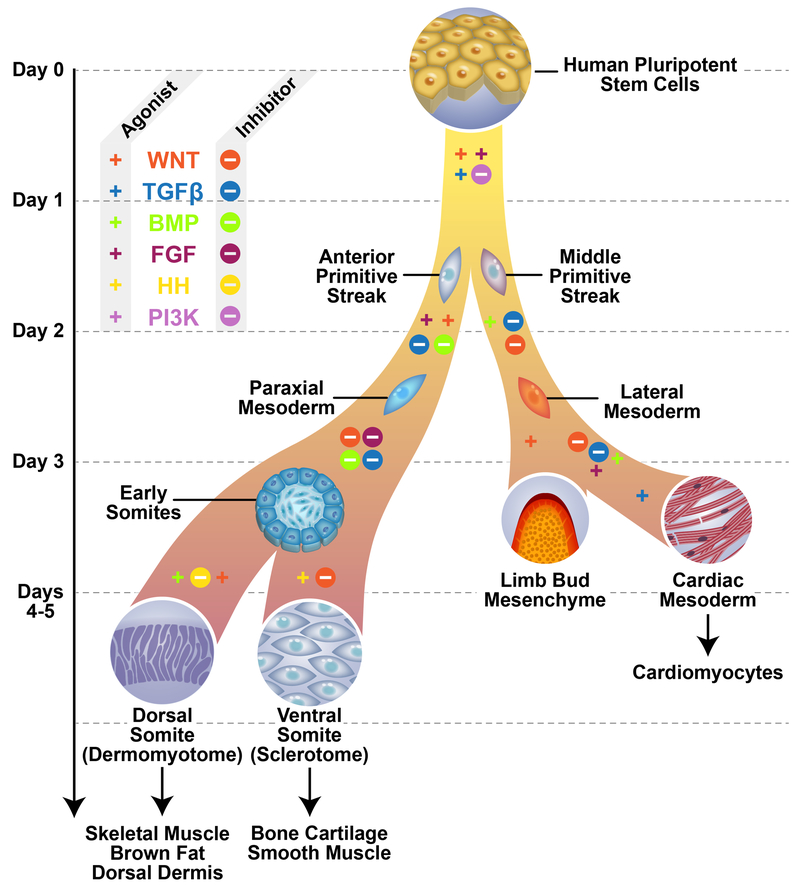

The study employs monolayer differentiation, driven with serum free medium supplemented with a daily-changing cocktail of (mostly small molecule) agonists and inhibitors of the WNT, TGFβ/BMP, FGF, and HH families, with some optimization on the established treatments with these factors (Mendjan et al., 2014; Umeda et al., 2012). At several steps (early patterning of mesoderm, and later patterning of cardiac or paraxial mesoderm), the authors provide two alternative conditions usually involving paired inhibitor/agonist combinations, leading to branching, hence “pairwise” lineage choices (Figure 1). One of the remarkable aspects of this study is the astonishing speed with which differentiation can be driven with this daily-changing regimen, particularly with regard to the paraxial mesoderm and derivatives. For example, other protocols typically take weeks to produce single lineage-committed progenitors (Chal et al., 2015; Darabi et al., 2012), and indeed the human embryo takes 3 weeks even to begin somitogenesis, whereas the current system produces presumptive skeletal myogenic and osteogenic progenitors in a matter of days. A second noteworthy aspect of their protocol is the homogeneity of derived populations. Using single cell RNA-seq, the authors find >90% purity at most stages, in some cases >98%. Such uniformly high levels of homogeneity seem to imply an absence of intrinsic patterning (i.e. programmed asymmetric cell divisions) at least through the stages investigated. To enable even greater homogeneity, the authors mine their RNA-seq data to identify surface markers useful for segregating various lineages: they discover GARP for cardiac mesoderm, and confirm the expression of DLL1 in paraxial mesoderm (Hrabe de Angelis et al., 1997) and PDGFRα in sclerotome (Takakura et al., 1997), and use these to enhance purity.

Figure 1.

Differentiation of various mesodermal lineages in vitro.

Signaling interventions that drive patterning of mesoderm often show very tight temporal dependencies. WNT signaling for example alternates multiple times along several lineages. The protocol also features paired combinations of agonist and inhibitor at branch points, e.g. BMP inhibitor/agonist for paraxial vs. lateral mesoderm and HH inhibitor/agonist for dermomyotome vs. sclerotome. Mesoderm cells are generally mesenchymal in morphology, however note the transient epithelialization associated with somitogenesis.

Taking advantage of this diverse set of related homogeneous populations, the authors use ATAC-seq, a method that identifies regions of open chromatin, to investigate whether the constellation of fates available to differentiating cells is restricted by accessibility to serially smaller regions of the genome during these early stages of development as Waddington’s landscapes are often used to suggest, or whether there might exist a common mesoderm-specific accessible genomic domain. They find neither. Rather, chromatin accessibility is driven by the presumptive pioneer factor activity of various key signaling effectors on a relatively plastic backdrop, such that old domains are closed and new domains are opened at each stage of differentiation. They find no evidence of “a monolithic pan-mesodermal program”.

Beyond this abundance of raw data, perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the work relates to the implications drawn to replicating somitogenesis in the dish. The formation of somites is one of the most beautiful and mysterious aspects of vertebrate embryogenesis. With clockwork precision, the paraxial mesoderm repetitively coalesces into segmented domains, as formerly mesenchymal cells become epithelial and bound the paraxial mesoderm into a series of paired blocks of tissue. Shortly afterwards this epithelialization is reversed as, for example, myogenic progenitors peel away from the epithelial dermomyotome and return to a mesenchymal morphology. Although mechanisms of somitogenesis are being revealed, we are still unable to replicate this exotic process in the dish, thus it is of considerable interest that the authors classify cells along one arm as somitomeres, and their downstream progeny as dermomyotome and sclerotome en route to skeletal myoblasts, fibroblasts and osteocytes. The authors are led to these classifications by the gene expression patterns, especially a transient pulse of expression in cells 6 hours after paraxial mesoderm is treated with FGF and WNT inhibitors. In various model organisms, the epithelial segmentation of paraxial mesoderm into somites is driven by oscillating activity of Notch, Wnt, and FGF signaling (Dequeant et al., 2006), leading to transient patterned expression of transcription factors including MESP2 and HEYL. Seeing expression of these genes, among others, the authors link this stage of differentiation to somitogenesis. They go on to characterize one of these transiently expressed genes, HOPX, in the mouse. Although evidence of wavelike expression during somitogenesis is not shown, using Hopx-cre, they find sporadic lineage tracing to vertebrae and ribcage, consistent with a model of transient expression in the somites. So, can the field now say that we understand somitogenesis well enough to recapitulate it in the dish? The morphology of cells under dermomyotome conditions is clearly distinct from and more epithelial than cells under sclerotome conditions. It would be fascinating to visualize the transitions in real time as paraxial mesoderm differentiates under the conditions described. Although the formation of frank 3D somites seems unlikely in monolayer culture, without actually visualizing the mesenchymal to epithelial to mesenchymal transitions that characterize somitogenesis, there will be a diversity of opinion as to whether this is indeed what is occurring along this arm of the protocol. Indeed, the expected cadherin fluctuations are not obvious in the gene expression patterns. Likewise, given the difficulty the field has had efficiently producing myogenic progenitors, absent nuclear MYOD+ myoblasts and multinucleated myotubes there will be a diversity of opinion on the value of comparing RNA profiles to those of pluripotent cells, which do not express these markers, when identifying cells as true skeletal myogenic progenitors. However, the transient pulse of presomitic gene expression and examples of static morphologies are intriguing, so there will be plenty of exciting follow up work in this arm to more deeply investigate the value of this model for the study of somitogenesis.

An important motivation for developing methods of differentiating pluripotent cells is to enable their eventual use in medicine. From the viewpoint of avoiding unwanted off-target effects, i.e. implanting an impure population containing cells that are wrong for the job, a single cell type of high purity is obviously desirable, and single cell RNA-seq offers an excellent window into assessing such purity. Blood, notably absent from this study, is the archetypical example of an organ that can be replaced through a single infusion of a homogeneous cell type. On the other hand, some tissue engineering applications demand complex cellular constructs, hence the growing interest in controlled organoid differentiation of iPS cells (Lancaster and Knoblich, 2014; Passier et al., 2016). It will be interesting to follow these two complimentary approaches; rapid production of homogeneous cell types vs. slow convoluted growth of more complex constructs; as attempts are made to translate them into medicines.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Michael Kyba is supported by the MDA (351022) and the NIH (R01 NS083549 and R01 AR055685)

References

- Chal J, Oginuma M, Al Tanoury Z, Gobert B, Sumara O, Hick A, Bousson F, Zidouni Y, Mursch C, Moncuquet P, et al. (2015). Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to muscle fiber to model Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Biotechnol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabi R, Arpke RW, Irion S, Dimos JT, Grskovic M, Kyba M, and Perlingeiro RC (2012). Human ES- and iPS-derived myogenic progenitors restore dystrophin and improve contractility upon transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell stem cell 10, 610–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dequeant ML, Glynn E, Gaudenz K, Wahl M, Chen J, Mushegian A, and Pourquie O (2006). A complex oscillating network of signaling genes underlies the mouse segmentation clock. Science 314, 1595–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabe de Angelis M, McIntyre J 2nd, and Gossler A (1997). Maintenance of somite borders in mice requires the Delta homologue DII1. Nature 386, 717–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster MA, and Knoblich JA (2014). Organogenesis in a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 345, 1247125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh KM, Chen A, Koh PW, Deng TZ, Sinha R, Tsai JM, Barkal AA, Shen KY, Jain R, Morganti RM, et al. (2016). Mapping the pairwise choices leading from pluripotency to human bone, heart and other mesoderm cell-types. Cell in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendjan S, Mascetti VL, Ortmann D, Ortiz M, Karjosukarso DW, Ng Y, Moreau T, and Pedersen RA (2014). NANOG and CDX2 pattern distinct subtypes of human mesoderm during exit from pluripotency. Cell stem cell 15, 310–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passier R, Orlova V, and Mummery C (2016). Complex Tissue and Disease Modeling using hiPSCs. Cell stem cell 18, 309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura N, Yoshida H, Ogura Y, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, and Nishikawa S (1997). PDGFR alpha expression during mouse embryogenesis: immunolocalization analyzed by whole-mount immunohistostaining using the monoclonal anti-mouse PDGFR alpha antibody APA5. J Histochem Cytochem 45, 883–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda K, Zhao J, Simmons P, Stanley E, Elefanty A, and Nakayama N (2012). Human chondrogenic paraxial mesoderm, directed specification and prospective isolation from pluripotent stem cells. Scientific reports 2, 455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]