Abstract

Evolving family structure and economic conditions may affect individuals’ ability and willingness to plan for future long-term care (LTC) needs. We applied life course constructs to analyze focus group data from a study of family decision making about LTC insurance. Participants described how past exposure to caregiving motivated them to engage in LTC planning; in contrast, child rearing discouraged LTC planning. Perceived institutional and economic instability drove individuals to regard financial LTC planning as either a wise precaution or another risk. Perceived economic instability also shaped opinions that adult children are ill-equipped to support parents’ LTC. Despite concerns about viability of social insurance programs, some participants described strategies to maximize gains from them. Changing norms around aging and family roles also affected expectations of an active older age, innovative LTC options, and limitations to adult children’s involvement. Understanding life course context can inform policy efforts to encourage LTC planning.

Keywords: long-term care planning, long-term care insurance, long-term care policy, life course

Introduction

Inadequate planning for long-term care (LTC) is a well-acknowledged American policy concern, despite the reality that most people will need some form of LTC during their lifetime. We define LTC as the provision of help with daily activities, due to an individual’s enduring physical or cognitive limitations, which can be delivered through a network of formal and informal services and supports. Estimates suggest a 69% future lifetime risk of needing LTC for the currently retiring population and an average 3-year duration of LTC need (Kemper, Komisar, & Alecxih, 2005). The aging of the baby boomers, compounded by increased life expectancy among older adults (Social Security Administration, 2014), will create a surge in demand on the LTC system. With this combination, some estimate that the number of older adults needing LTC will double by 2040 (Johnson, Tooney, & Wiener, 2007). Simultaneously, the relative size of the younger population available to support social programs or deliver LTC is expected to fall due to a downward trend in birth rates, shrinking the pool of familial and financial support for older generations (Passel & Cohn, 2008; Vincent & Velkoff, 2010).

Potentially compounding these issues, recent demographic and economic changes may further decrease the supply of informal caregivers, who provide the majority of LTC in the United States. In the mid-2000s, 90% of the community dwelling population in need of LTC, or approximately 10 million individuals, received some type of informal care (Kaye, Harrington, & LaPlante, 2010). Demographic changes that may decrease the supply of informal care include delayed childbearing age among women, which raises the age for child rearing (Hymowitz, Carroll, Wilcox, & Kaye, 2013), and increased labor participation among middle-aged women (Chao & Rones, 2013). Furthermore, economic conditions, including the recession and changing labor dynamics, have impeded younger adults’ ability to provide for themselves, in turn increasing their reliance on middle-aged parents (Carnevale, Hanson, & Gulish, 2013; Fry & Passel, 2014). Declining coresidence across generations, though potentially attenuated by the great recession (Fry & Passel 2014), may also affect the ease with which adult children can care for aging parents (Ruggles, 2007). All of these shifts, which either increase demands on working-age adults or make caregiving more logistically difficult, may in turn negatively affect adult children’s availability to provide informal care to older family members.

Other than informal care, individuals may receive paid care financed either out-of-pocket, by private LTC insurance (LTCI), or by limited public programs like Medicaid, state and local assistance programs, or the Veterans Administration; however, these latter alternatives to pay-as-you-go private financing have shortcomings. The private LTCI market is small and has struggled to flourish in recent decades, with only 7 million to 9 million individuals holding LTCI policies (America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2012). High premiums (an average of $2,781 annually for a 65-69 year old in 2010) partially explain the small private market (Ujvari, 2012). The largest currently available social insurance option, Medicaid, is available to those who are indigent, sometimes from health care or LTC needs, employs highly restrictive asset limits, and provides limited coverage for home-based LTC in many states. Although unavailable to most Americans, the Veterans Administration covers LTC for those with a service-related disability.

Amid these options, individuals may seek to reduce the uncertainty surrounding their LTC needs by engaging in LTC planning. LTC planning includes a priori decision making about how to serve a future disability risk. LTC planning can include financial decision making, for example, setting aside money to pay for LTC or LTCI, or discussing caregiving options with family members or friends. Many individuals do not plan, in part due to lack of knowledge about how to finance or choose services and supports (Robison, Shugrue, Fortinsky, & Gruman, 2013). LTC planning requires the ability to project potential resources—including the availability of adult children, community support, and financial resources—and to weigh resource availability with care preferences before one is in need of LTC. Recent surveys reflect that while 25% of individuals may have discussed their preferred LTC with family, only 22% have discussed the ways they would pay for that LTC and only 17% have discussed their family members’ role in their LTC (Weiner et al., 2015). Individuals also may not plan because it is difficult to project one’s future health. Evidence suggests that most individuals do not accurately estimate their risk of developing chronic or acute illnesses that could result in the need for LTC (MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2009); 60% of middle-aged adults believe they are very or somewhat unlikely to need future LTC (Henning-Smith & Shippee, 2015). Besides having to project one’s future health state, changing demographic and economic dynamics may create an additional level of uncertainty in the supply of informal care providers that could affect whether and how individuals plan for older age.

LTC planning is admittedly complex but critical to accessing LTC that maximizes patient autonomy and family financial well-being. When LTC planning does not occur, individuals may not receive needed care or may receive care, but with negative consequences, such as families becoming unexpectedly responsible for caregiving and thus experiencing a higher risk of health, financial, and emotional strain (Chari, Engberg, Ray, & Mehrotra, 2014; Fast, Williamson, & Keating, 1999). Families may also help pay for LTC and exhaust family assets because of LTC expenses. Care recipients may end up in LTC situations that do not meet their preferences and wishes or, in the worst cases, their LTC needs. Finally, due to LTC expense, individuals can become dependent on financially strapped public programs, such as Medicaid, when such dependence could have been avoided. Thus, despite its difficulty, LTC planning offers a value proposition to both individuals and broader American society.

New Contribution

The idea of planning ahead for uncertain LTC needs and resource availability emerged as a recurring theme from focus groups that we conducted to understand family factors influencing LTCI purchase behavior. Our initial analysis of these data investigated the role of intrafamily dynamics in LTCI purchase and explored themes of burden and autonomy within individual purchase decisions (Sperber et al., 2014). However, important discussion emerged from the focus groups that was beyond the scope of the original analysis of LTCI purchase decisions. This discussion reflected a life course perspective, specifically how past and current interpersonal relationships and socioeconomic context may have affected choices, and discussions of LTC planning beyond LTCI alone. In this article, we unpack this theme of planning for LTC in the face of uncertainty by using constructs from life course theory to explore the impact of life course context, such as changing socioeconomic context and cumulative life experiences.

Although most current examinations of LTC planning reflect a point-in-time perspective (Brown, Goda, & McGarry 2012; Curry, Robison, Shugrue, Keenan, & Kapp, 2009; Feinberg, Reinhard, Houser, & Choula, 2011; Weiner et al., 2015), some existing literature on LTC planning incorporates elements of life course theory. However, these studies often investigate one or two elements of life course theory and primarily focus on financial decision making. Research reveals the importance of individual’s social network when planning for aging. Studies that focus on individuals’ expectations for future aging and LTC found that prior caregiving experiences increase individuals’ expectation of moving into a retirement community or other supportive housing environment (Robison & Moen, 2000) or willingness to purchase LTCI (Coe, Skira, & Van Houtven, 2015). Additionally, research underscores the influence that younger generations can have on older adults’ LTCI purchase decisions, both positive and negative (Brown et al., 2012; Sperber et al., 2014), and how demographic shifts have changed aging in families and recently created more complex and diverse family structures (Hareven, 1994). Barnett & Stum’s (2012, 2013) research on future LTC planning reminds us that couples often make LTC planning decisions in concert, adding multiple individuals’ experiences. Some literature on LTCI purchase decisions incorporates socioeconomic contextual factors such as perceptions of an unstable insurance market (Curry et al., 2009) or integrates the socioeconomic context into other theoretical models to understand an individual’s LTCI purchase decision (Schaber & Stum 2007). Other research reflects the role of generational norms, as survey data indicate that birth cohort and particularly baby boomer status decrease individuals’ expectations for LTC need and negatively affects their engagement in LTC planning (Robison et al., 2013).

However, given both the longer term demographics trends discussed earlier and the punctuated shifts of the great recession, a deeper understanding of the role of life course context on LTC planning offers a new contribution to our understanding of current LTC planning. Using a life course lens, our findings illuminate how factors from multiple dimensions of life, such as family or work, as well as from prior experiences can affect an individual’s navigation of this transition, shedding brighter light on LTC planning in the life course.

Conceptual Model

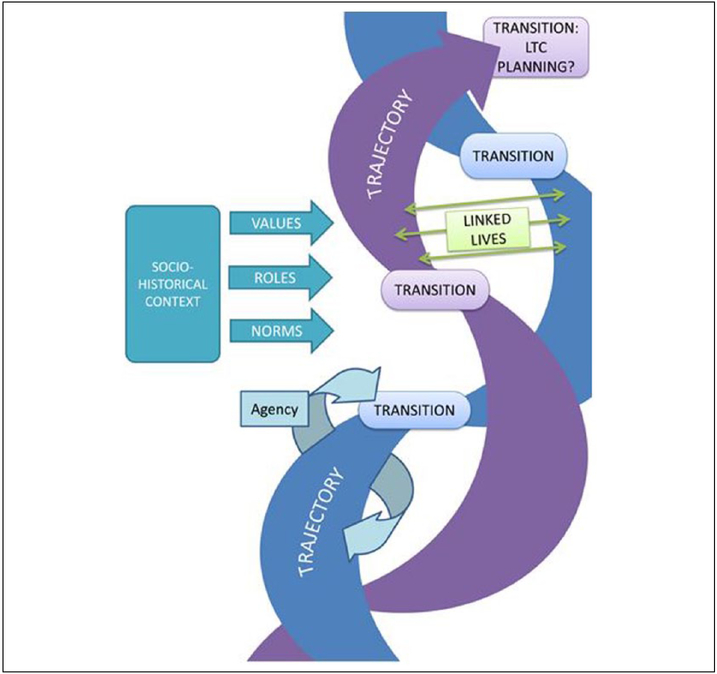

We developed a conceptual model (Figure 1) using constructs from a life course framework (Elder, 1994). This conceptual model reflects that life courses consist of trajectories (i.e., interweaving pathways in given roles, such as work or parenting) and transitions (i.e., pivot points as individuals move between roles on a trajectory; Elder, 1985). Trajectories and transitions are guided by personal agency, which shapes the course of one’s life (Elder, 1994). Another feature of this model, consistent with life course theory, is the consideration of life experiences as being cumulative (i.e., earlier experiences and contexts can have implications at a later point in time; Macmillan, 2005; Mayer, 2009). Figure 1 reflects our conception of how life course context may influence individual LTC planning; here, interweaving trajectories are shaped by embedded transitions, all of which are guided and influenced by human agency. We consider LTC planning as one transition point in a trajectory of aging. Although the LTC planning process may not be stepwise and linear (individuals may revisit LTC planning), the placement of LTC planning in the figure reflects the notion that LTC planning is cumulatively affected by prior life trajectories and transitions, all notions which emerged from our data. In this conceptual model, personal agency is sometimes bound by social influences, with the notion of “linked lives” in which one’s life trajectories are interconnected and thus affected by others’ life courses (Alwin, 2012), reflected in the intertwining trajectories in Figure 1. These networks of individual trajectories are situated in a sociohistorical context, including socioeconomic and cultural influences, which imparts values, norms, and roles (Macmillan, 2005). With these constructs in mind, we asked the following research question of the data: How do life course dynamics, including linked lives and sociohistorical context, influence LTC planning as one ages?

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of factors influencing long-term care planning based on life course framework constructs.

Note. LTC = long-term care. This conceptual model, developed using constructs from a life course framework (Alwin, 2012; Elder, 1985, 1994; Macmillan, 2005; Mayer, 2009), shows how various factors throughout one’s life course may together function to affect LTC planning. According to this model, LTC planning is one transition that can be shaped by prior experiences, including trajectories (pathways in specific roles) and other transitions, and can occur at any point or at multiple points in one’s life. Sociohistorical context may affect values, norms, and roles as one moves through trajectories and transitions. Linked lives reflects how one’s individual trajectories can be interconnected with and affected by the trajectories and transitions of others.

Method

This study was a secondary analysis of data originally collected to understand how adult children can influence LTCI purchase decisions. We conducted eight focus groups in geographically dispersed markets (Boston, Massachusetts; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Chicago, Illinois [downtown and suburb]). To meet the objectives of our primary analysis (Sperber et al., 2014), we conducted separate focus groups with older parents who had purchased LTCI (two groups), older parents who had not purchased LTCI (two groups), and adult children mixed with regard to whether their parents had purchased LTCI (four groups). Details of eligibility criteria for the primary study are published elsewhere (Sperber et al., 2014). Of relevance to this secondary analysis, parents were eligible if they were aged 50 to 75 years and had primary or shared responsibility in their family for deciding how their LTC needs would be met. Older parents were ineligible if they were receiving Medicaid, users of the Veterans Affairs health care system with a service-connected disability rating of 70% or greater, or had applied for long-term disability benefits, because these characteristics would make private LTCI irrelevant or impossible (due to underwriting). Eligible adult children had parents who were at least 50 years of age, had not applied for long-term disability benefits, did not receive Medicaid, and were not users of the VA health care system. A national market research firm recruited participants from their database of individuals who had agreed to be available for market research studies.

Focus groups lasted 1 to 1.5 hours each and were led by one moderator, with another team member present to take notes. The moderator used a prepared guide to structure the focus groups according to primary research questions. Different questions were asked of older parents and adult children. Older parents were asked to provide reasons why they had decided to purchase LTCI or not and, if they had LTCI, to explain how this might affect their family members’ roles in their care. Adult children were asked to describe their knowledge of and role in their parents’ decisions about LTCI and how, if their parents had LTCI, this could affect their roles in their parents’ care. Throughout the older parent and adult child focus group sessions, the moderator asked individuals to elaborate on family discussions about LTCI and LTC planning.

We analyzed data using directed content analysis (Hsiu-Fang & Shannon, 2005). Content analysis includes labelling text with codes, or descriptive names, and integrating the coded text to identify patterns or themes. We conducted a directed form of content analysis because we started a priori with codes that had been assigned based on our primary research questions, and, for this secondary analysis, two researchers with expertise in qualitative methods (IB, NS) worked together to organize the previously coded data according to categories in our conceptual model (Figure 1). These theory-derived categories (transitions, trajectories, roles, norms, values, agency, and linked lives) provided an initial conceptual framework to organize the data. We then reviewed coded text that we had initially organized according to our a priori categories and worked to inductively identify themes, which we describe below. The full research team, which was composed not only of qualitative methodologists but also experts in retirement planning, LTC financing and policy, and economic decision making, met to discuss findings and identify areas for further exploration.

Findings

Characteristics of focus group participants are displayed in Table 1. Participants were between the ages of 28 and 69 years. Of the 80 participants, 46% were male, 60% were currently married or partnered, and 77.5% were White. Most participants were college educated (60%) and working for pay (69%). Although all participants came from families that considered LTCI purchase, purchasers were more likely to be college educated than nonpurchasers (85% vs. 26%), which reflects typical socioeconomic differences among these two groups.

Table 1.

Focus Group Participants.

| Older adult parents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| LTC insurance purchasers (N = 21) |

LTC insurance nonpurchasers (N = 19) |

Adult children (N = 19) |

|

| M (SD) or N (%) | |||

| Age (years) | 65 (7) range = 51-73 | 65 (6) range = 52-73 | 44 (11) range = 28-69 |

| Male | 11 (52%) | 8 (42%) | 18 (45%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 19 (90%) | 16 (84%) | 27 (68%) |

| Black | 1 (5%) | 2 (11%) | 7 (18%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (8%) |

| Asian | 2 (5%) | ||

| Married or partnered | 15 (71%) | 14 (74%) | 19 (48%) |

| College educated | 18 (86%) | 5 (26%) | 25 (78%) |

| Working for pay | 11 (52%) | 10 (53%) | 34 (85%) |

Note. LTC = long-term care.

Across focus groups, participants’ statements about factors influencing their LTC plans and preferences reflected an interrelationship between their own and others’ lives, the cumulative nature of life experiences and influences, and the impact of sociohistorical context on LTC planning. As one participant said:

I guess in my mind, there isn’t a most important [reason for purchasing LTCI]. It’s a function of a series of interdependent decisions that you make. I think that what pushes you to buy [LTCI] is not always one aspect. I think it’s an accumulation of aspects, and your experiences, and what you’ve seen, whether it’s your parents or friends or whatever that is that propels you to do that, whether it’s asset preservation, security, choice. I think they’re all interdependent. I’m not sure you can separate them out in my mind. (Older parent, purchaser)

Participants described how their interactions with others (linked lives) could either facilitate or inhibit their personal agency in LTC planning. This dynamic also affected their LTC planning cumulatively, in that experiences with other individuals in the past were likely to affect their current decisions. Related to sociohistorical context, participants discussed economic instability and how it shaped the LTC planning choices they had available and were willing to make. Participants additionally compared current cultural norms and social roles with those of prior generations and considered the impact of these factors on their LTC choices. Table 2 connects these themes, discussed in detail, to constructs from a life course framework.

Table 2.

Summary of Findings.

| Theme | Description | Elements of the life course framework |

|---|---|---|

| Caring for others as a facilitator and inhibitor of LTC planning |

|

Linked lives |

| Planning for financial security in a climate of institutional instability |

|

Sociohistorical context |

| We are not our grandparents: new roles and norms |

|

Sociohistorical context |

Note. LTC = long-term care; LTCI = long-term care insurance.

Caring for Others as a Facilitator and Inhibitor of LTC Planning

Facilitator of LTC Planning: Foreshadowing Your Future Through Caregiving.

Past experiences with caregiving motivated individuals, particularly older parents, to engage in LTC planning for themselves. Individuals said that they wanted to avoid negative outcomes that they watched others endure, including family conflict, financial strain, and unappealing LTC choices. Many older respondents had cared for family members themselves; following these experiences, they did not want to find themselves similarly dependent on their children. As one respondent said:

I took care of my aunt. She had no children of her own. Her closest relatives, siblings, were … in other places. It created a lot of resentment in my own home. My wife wanted me to tend to things that she wanted me to tend to. I felt I had a responsibility to take care of my aunt, who was very dear to me. I would have to—I would go and see her regularly. I would have to leave before I wanted to, because I had to get home… I didn’t want that same kind of a situation to happen to me, where I was dependent, especially, on family members. Because, even though they do their best, there is resentment. Then you feel guilty because you have to leave … I didn’t want any of that to happen. (Older parent, purchaser)

Individuals had experienced a range of negative consequences, including family strife, as above, or financial strain, as in this participant’s experience:

That money goes fast. We have two women come in, and God bless them. One is a next-door neighbor and one’s a lady that we know from Boy Scouts. We pay them $10 an hour. To get help like that would be wonderful, that they provide. But we still wind up paying $14,000, $16,000 a year. My mom has her IRAs, her annuities, but when you pull that out, tax is put against it. Tax hurts. Like 30% tax. 30% of $100,000, you just spent $30,000. I’m worried about eating out. Talk about stress on the caregiver. That’s an understatement. (Adult child)

Directly experiencing these negative consequences imparted the value of LTC planning to many participants. Simply watching others engage or fail to engage in LTC planning also affected decisions around financial planning for LTC. Some individuals remarked that those who did not have a LTC plan suffered from lack of choice: They either had to burden their family members for care or live their lives in a facility, and not necessarily one of their choosing. They regarded financial planning for LTC as a way to avoid burden and lack of choice. As one purchaser said, “I knew that [LTCI] was something that I wanted to have when I was seeing what was happening around me” (Older parent, purchaser). Others, though, said that they knew people who had purchased LTCI only not to use it:

I remember my father-in-law had it, and it was useless … I remember we figured out how much he had spent on long-term care … throughout his life, he had spent $300,000, and never got to use a penny of it. (Adult child)

Thus, they questioned the value of LTCI and instead regarded saving (i.e., self-financing) as a more attractive way to plan for LTC expenses.

Inhibitor of LTC Planning: Focusing on the Next Generation.

Though past experiences with older generations facilitated LTC planning, currently caring for children was a barrier to planning. This was particularly true for making or following through on financial decisions, such as purchasing LTCI or saving for LTC. Individuals said that purchasing LTCI would mean that they would have to prioritize future LTC over current financial obligations:

I talked to my daughters. I have three daughters and a son. My son is 42 and he’s got cerebral palsy, bound in a wheelchair. I talked to my oldest daughter. If something happens to me or my wife my oldest daughter can take care of my son. We don’t have any insurance. I can’t afford it. All my money, like I said, goes to taking care of him and taking care of the family. I just can’t afford it. (Older parent, nonpurchaser)

Some older parents said that, in hindsight, LTCI would have been less expensive had they bought it at a younger age, but they were not ready to consider LTCI at the time. Instead, when they were younger, they were concerned with taking care of their children’s needs. This sentiment was echoed with adult child respondents who were currently caring for their own children, reflecting well the notion of linked lives. As one said,

Her idea would be for me to pull up roots and move to Florida and take care of her. I have a husband and two daughters here, so that’s probably not gonna happen. So we need to be a little bit more realistic. (Adult child).

The timing of cultural roles and associated priorities that compete with LTC needs was an important component of whether informal caregiving would be available and whether adult children might engage in LTC planning with their parents.

Planning for Financial Security in a Climate of Institutional Instability

Participants expressed pessimism and distrust toward employers, government programs, and insurers, as well as concern about the financial future of adult children. For some, these factors were motivators to devise a LTC plan. Individuals said that older adults were living longer with an increased risk of disability, and they expressed concern about the government’s ability to support this growing need:

We’re for the first time realizing we’re all going to live longer, and you start to think about these things in a different way. … This is a thing both in terms of health care and long-term care is the disaster for the next generations coming along. It’s just going to be an absolute disaster because they’re not going to be prepared for it. Medicare cannot conveniently support it very much longer, and these kinds of things are something that need to be raised in the public’s consciousness now. And for those of us who are our age or later, it’s almost too late. (Older parent, purchaser)

Older parent and adult child respondents said that they did not want to find themselves in the same position as those from prior generations, whom they viewed as not having a LTC plan. Although they wanted to be better prepared, they perceived that prior generations did not plan for LTC because it was more common to have supports in place. Such supports came from union jobs or “loyal” employers. Participants said that, in contrast to the past, now they could not trust institutions to meet their needs. As one person said:

But, with what’s going on in Washington, right now, with Obamacare and all this, who knows what’s going to happen with the government, 5, 10 years from now. If something were to happen to me, I’ve got grandkids. I’ve got myself to think about. I live alone. After I retired, I took out a long-term care policy … I bought it, really, I guess, as a safety net. If something were to happen at some point in the future, you’re not going to be able to rely on the government. That’s for damn sure. (Older parent, purchaser)

Given concerns about the effectiveness of government programs and other safety nets, many individuals stated that they wanted to have security or, as they said, “not be afraid.” This sentiment was especially salient among those who had purchased LTCI. As one participant said, “That was definitely a reason, the security of knowing, if something does happen, there is an option” (Older parent, purchaser). The hope was that by purchasing LTCI, one might have more control over the future, regardless of institutional instability.

Although some participants felt confident in their LTCI purchase, others, across groups, did not trust that companies would stay in business to provide funds when needed. One participant who had not purchased LTCI said:

If we’ve tried to put money away, if we’ve tried to save for our retirement, and then how many of us have had companies go out of business and take your money that you put in there? You’ve lost money in the stock market or wherever you had your money in retirement. You put into retirement and your retirement is no longer there because the company went out of business or cut your retirement. Whatever you thought you were going to get. When you’re 20- or 30-some years old, or even 40-some years old, and you’re thinking, “I’m going to put this money aside for when I get older and I need long-term health,” and then you don’t know if that company is going to be there when you turn 60 or 70 years old. Even today if I was doing it, I’m not sure I would trust a company. (Older parent, nonpurchaser)

Some older parent purchasers also acknowledged that the context was different when they purchased their LTCI—they suggested that now there is more instability within the LTCI market, leading them to question the current value of a product that they had previously purchased. This perception of instability shaped the perception of LTC planning options even among the relatively wealthy LTCI purchasers. Younger adult children also discussed market instability and whether it would be better to purchase now or wait to see if the market improved. As one said:

It will be [more money when you’re 50] but … there’s so many different types of policies now and every company has different programs. Do you want … assisted living … a cash policy … a specific nursing home policy? So … I’m not going to buy one now. I don’t know what it’s going to be like in 20 more years. (Adult child)

Perceptions about socioeconomic instability seemed to affect LTC planning not only with regard to older adults’ LTCI purchase decisions but also with regard to children’s availability to support their parents’ LTC. Older parents regarded working-age adults as having fewer financial opportunities today than they had when they were younger. Older parents assumed that they would not be able to count on their adult children to support their LTC needs either directly or financially:

Not only that, they’ve got their own issues. My son is raising two teenage daughters. My daughter is going to have a son. They’re not really—they’re concerned about our well-being, but—and again, like you said. … The economic situation today. They’re facing a different future than we faced when we were their age. My son just went back to work after being out of a job for 3 years. The least of his worries would be if I have long-term care insurance if I get sick. He’s got some major problems he’s facing right now. (Older parent, nonpurchaser)

Given these concerns, older parents felt they might be “on their own” and unable to count on their children to support their LTC needs. Some older parents suggested that although adult children might like to help, they were not financially able to do so. Other older parents reflected that adult children were more concerned with how they could receive financial support from their parents, including moving in, rather than helping their parents. As one participant joked, the conversation was more likely to be, “Dad, you have a house. Can I move in?” (Older parent, nonpurchaser) than about how adult children could help with LTC planning. The sentiment that older parents today have more financial resources than their adult children was echoed in the adult child groups.

Despite the lack of trust in and respect for both public and private institutions, some individuals were open about their attempts to maximize gains from public programs and institutions, gaining “value” for themselves. Several individuals discussed and offered strategies to maintain family assets and still become eligible for Medicaid:

We had to move money, and it was a 3-year look back and a 5-year look back. Just a whole—it was a mess. However, our experience luckily enough, my mother could live with my brother, and she had over 10 years of some good quality time. So only the last year and a half, we had to put her in a local—we were very fortunate. We did move all the money. She was on Medicaid. (Older parent, purchaser)

These statements were made by both older parents and adult children, with adult children explaining: “Well, you put your finances in a revocable trust … and it protects their assets. It’s not in their name. I think they’re allowed a car and X amount of dollars” (Adult child). Thus, despite the lack of trust in institutions and the future of the safety net, individuals seemed open to maximizing benefits available through the safety net.

We Are Not Our Grandparents: New Roles and Norms

Participants reflected on how changing norms for older and younger adults have affected their LTC considerations. A common assertion within older parent groups was that they are active and independent in a way that their grandparents were not. They recalled that as children, they regarded their grandparents as “older people,” with the only options being to stay home or go to a nursing home. Now that they have become grandparents themselves, they view themselves as being more active than the older adults whom they knew in their youth. They also believed that their children saw them as young and vibrant and not needing LTC:

Because their grandparents—they were old. When they were 60 or 70, they were old people. They didn’t do what we do. They weren’t active. … They were sick. They had a harder life. We’re 70 and we’re not—we live younger lives. We live active lives. … They’re like, “Grandma, you can’t be older. All these other kids have old grandmas and grandpas. I know you’re a lot younger than that.” I’m like, “You’re right.” … They think of their grandparents as being old when they were at our age, and so they don’t think of us as being that old, because we’re not like their grandparents were. (Older parent, nonpurchaser)

This belief in independent aging had a range of implications for LTC planning. On the one hand, some older adults sought a plan that would guarantee their ability to maintain independence and pursue their desires. However, others said that they felt that they were aging well and were spending their money on activities that they could enjoy now, rather than setting it aside for future LTC, which they hoped they would not need.

In line with their preference for active lifestyles, older adults were optimistic that new options would be available to them to support active aging. For example, they said that continuing care retirement communities and assisted living did not exist for their parents and were more appealing to them than the nursing homes that were the only options for prior generations. Older adults described their generation (the baby boomers) as being inventive, a quality that they believed could help overcome current limitations with LTC:

The one thing I think our society is coming around to is trying to come up with alternatives. … We are the baby boomer generation that now we’re looking at seriously some other alternatives to all the expenses of nursing homes and long-term care, the assisted living … (Older parent, nonpurchaser)

They believed that changing demands and expectations from the baby boomer generation could change LTC delivery. They discussed a model in which networks of caregivers could support aging in place as a future direction. However, in some cases, this optimism that there will be new LTC mechanisms encouraged individuals to delay LTC planning. As one person said, “I think I’m being an ostrich by just burying my head in the sand” (Older parent, nonpurchaser).

Individuals also discussed how changing roles and norms among the younger generation could affect availability of informal care and thus the need for LTC planning. Participants said that children, regardless of gender, might not be available to provide informal care because of work obligations, in contrast to prior generations in which women more often stayed home to care for family. The perception of a new normal of two working adults was brought up both from both the perspective of older parents and adult children: “And the next generation, both spouses are working. There is no one to take care of that group in the home, so you’re looking at an institutional situation somehow” (Older parent, purchaser). Although children would not necessarily be available to function as primary caregivers, it was notable that both male and female children were regarded as being, or having the potential to be, involved with various aspects of LTC, including planning and direct support. Thus, changes in gender-based roles both limited and expanded children’s availability to provide informal care. Older parents and adult children additionally discussed how geographic dispersion meant that parents must rely less on their children for support now than previous generations. Participants recalled having a grandparent or parent live in their home; they said that adult children now tend to live in other areas. As one older parent said, “I believe that our children would care and do what they could, but they live in Seattle, Chicago, and Washington, so they’re not down the street” (Older parent, purchaser).

Discussion

We applied a conceptual model influenced by life course theory to focus group data to understand how multidimensional factors can influence LTC planning. Our results reflect that, though LTC planning may be viewed as an isolated event driven by personal choice that frequently occurs during the transition to later life, LTC choices may be influenced by events that occur before one is necessarily ready to think about LTC needs. With LTC, often, one must plan or allocate resources for a transition to disability that has not occurred yet (and may not ever occur). In some ways, the act of planning for a future transition that is uncertain runs counter to the natural flow of one’s life course. Though similar to other life transitions in which one sets aside resources for future needs, such as saving for retirement or children’s college, LTC planning can be challenging for individuals to invest in and for policy makers to present as important and valuable to individuals. As such, our findings from this analysis offer insights with several implications for policies intended to encourage LTC planning.

We found that exposure to caregiving earlier in life, whether for older or younger recipients, can affect one’s own LTC planning. Seeing others age and face LTC can be a motivator to plan for oneself even later in life (Finkelstein, Reid, Kleppinger, Pillemer, & Robison, 2012). However, caring for children can detract from one’s own care planning, both in terms of priority setting and financially (e.g., day care over LTC). As a result, catching up—particularly setting aside resources—can be difficult, as evidenced by older adults in our focus groups who said that they did not choose to purchase LTCI when they were younger, in part due to competing child care costs, and consequently found that the annual cost of LTCI became prohibitive. Given the reduced availability of adult children for informal caregiving because of geographical dispersion and increased workforce participation, the very caregiving experiences that drive LTC planning processes may become less frequent. At the same time, younger adults are delaying childbearing (Hymowitz et al., 2013), which delays the ages at which they are caring for young children. Additionally, the socioeconomic environment has created a phenomenon in which adult children struggle to find work and are dependent on their parents past adolescence (Carnevale, Hanson, & Gulish, 2013). This suggests that competing responsibilities will continue to pose a challenge to LTC plans for future generations. Policies or interventions to encourage LTC planning earlier in life could include exposure to real-life stories to motivate individuals to consider their own risk. Communication about options might optimally be targeted to individuals whose life course exposure makes them more open to thinking about those options; for example, balanced information about LTCI might be provided to current caregivers with respect to their own LTC planning. Additionally, it would be important to tailor communication, particularly communication directed at younger parents, to acknowledge the challenge of LTC planning in the midst of current family demands, offer solutions for balancing competing needs, and highlight the potential advantages of earlier planning.

The broader socioeconomic and cultural context has changed both between and within generations, with several implications for LTC planning. First, some older parents from our groups purchased LTCI to protect themselves against perceived unstable conditions, believing that they cannot rely on government or employer programs to provide for them. Participants’ lack of trust in the future viability of public social insurance programs suggests challenges for policy makers interested in a future public LTCI option. However, participants acknowledged that the private LTCI market is now also unstable. Some purchased LTCI to have different options for LTC than their parents or grandparents; others said that they instead followed in the footsteps of prior generations, only to find that, though their parents had LTC support from family and employers, informal support is now harder to obtain (with children unavailable to provide care). Whether or not the difficult socioeconomic context for young adults will inadvertently make them more available to provide informal caregiving—for example, because of more limited earnings potential in the formal economy—remains to be seen. It is interesting that, despite their lack of trust in institutions, individuals in our focus groups also felt motivated to try and maximize their financial well-being from public programs and insurers, including shielding assets to ensure they could be eligible for Medicaid while still leaving an inheritance for children. Quantitative data on this type of wealth transfer have indicated that it happens in a small proportion of Medicaid users (Lee, Kim, & Tanenbaum, 2006), though data on wealth transfers are hard to gather accurately. The tension between worries about the long-run solvency of public programs and short-run behaviors to maximize personal gains from public programs did not appear to strike participants.

Although concerned about a climate of institutional instability, participants noted that there are now more options for LTC than in the past. Indeed, alternative settings for LTC, such as assisted living and continuing care retirement communities, have become important components of the LTC spectrum and substitute for nursing facility care for some individuals (Grabowski, Stevenson, & Cornell, 2012). Participants’ remarks about believing in a more vibrant older age indicate the need to refashion the current narrative about what it means to plan for LTC. For example, public policies that incentivize setting aside money for LTC to preserve a free and active old age, despite disability, could encourage individuals to make a LTC plan. Participants in our groups seemed open and interested in innovative new models, particularly those that could offer a “good value” to them and their independent children. This optimistic stance toward what lies ahead may be generation-specific and a unique characteristic of the baby boomers, given the pace of innovation they have witnessed over their lifetime. To the extent that this optimism dissuades older adults from making LTC plans—for example, if older adults assume that it will all work out—messaging could illustrate real risks from lack of planning. To the extent that older adults are open to new ideas for LTC planning, there is an opportunity for both policy makers and social entrepreneurs to offer innovative products specifically suited to the values and norms of this next generation of LTC recipients.

The inspiration for this analysis was grounded in participants’ own statements regarding LTCI purchase decisions that reflected a life course perspective, specifically how interpersonal interactions and social context may have affected choices; however, because this is a secondary analysis, there are some limitations. The criteria that we used to define focus groups based on familial role (i.e., older parent or adult child) and LTCI purchase status for our primary research question are slightly less proximal to the present research question, but close in that, we elicited perspectives across the generations and among those who have engaged in more and less LTC planning. Additionally, focus group participants included only families with both adult children and older parents and thus do not reflect experiences of childless older adults nor those with disability in early life. Though we analyze data using concepts from life course framework, data were not elicited over time. Despite these limitations, the depth of responses offers important insights for future policy to encourage LTC planning.

Current policies and supports to aid individual decisions about LTC are structured under the assumption that these decisions are made as people age and begin to consider later life needs and are driven largely by personal choice rather than contextual issues; however, our findings support the notion that later life decisions about LTC are affected by events that happen throughout the course of one’s life. Policies to encourage LTC planning must, at a minimum, acknowledge and, if possible, directly address interpersonal and sociohistorical contexts. This includes enabling and encouraging LTC planning for those who face competing family demands of adult children, older parents, and their own future LTC needs. If individuals are making LTC plans in a context of perceived economic instability or changing norms, this context is likely to shape their perceptions of the value of LTC planning and the palatability of public and private LTCI options. Given ongoing dialogue on the role of social insurance programs, awareness of the appropriate role of safety net programs in LTC planning is critical. Viewing these insights in combination, our findings imply that the most effective policies may be those that combine private planning with public programs, thus reducing private economic caregiving burden (Coe, Goda, & Van Houtven, 2015) while not shifting that burden entirely to public programs. The Partnership for LTC program, which allows individuals to qualify for Medicaid funding without exhausting assets if they first rely on a private LTCI policy, is one example of such a program. Though it has met with limited success to date, the changing spectrum of Medicaid LTC funding (Konetzka, 2014)—which increasingly funds home- and community-based services and thus makes community-based public LTC more accessible—may increase the appeal of this type of public–private partnership for financing LTC. Efforts to encourage and facilitate LTC planning, which can incorporate employers and nonprofits such as AARP, or local area agencies on aging marketing campaigns to “age in place” or “plan care needs” via toolkits or other means, can directly address competing family demands and educate consumers about the limitations of safety net programs, reflecting shared burden between public programs and private responsibility. These suggestions illustrate how our findings, which illuminate how multidimensional factors affect individual LTC choices over time and consider the process of LTC planning in line with how individuals actually live their lives, can contribute to LTC policy and innovation.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research at the National Institute of Nursing Research (IR01NR13583-1).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alwin DF (2012). Integrating varieties of life course concepts. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- America’s Health Insurance Plans. (2012). Who buys long-term care insurance in 2010–2011? A twenty-year study of buyers and non-buyers (in the individual market). Retrieved from https://www.ahip.org/WhoBuysLTCInsurance2010-2011/

- Barnett A, & Stum MS (2012). Couples managing the risk of financing long term care. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33, 363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett A, & Stum MS (2013). Spousal decision making and long term care insurance. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning Education, 24(2), 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR, Goda GS, & McGarry K (2012). Long-term care insurance demand limited by beliefs about needs, concerns about insurers, and care available from family. Health Affairs, 31, 1294–1302. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale AP, Hanson AR, & Gulish A (2013). Failure to launch: Structural shift and the new lost generation. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce; Retrieved from http://cew.georgetown.edu/failuretolaunch [Google Scholar]

- Chao EL, & Rones PL (2013). Women in the labor force: A databook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/cps/publications.htm [Google Scholar]

- Chari AV, Engberg J, Ray KN, & Mehrotra A (2015). The opportunity costs of informal elder-care in the United States: New estimates from the American Time Use Survey. Health Services Research, 50, 871–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe N, Goda GS, & Van Houtven C (2015). Family spillovers of long-term care insurance (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 21483). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w21483 [Google Scholar]

- Coe N, Skira M, & Van Houtven C (2015). Long-term care insurance: Does experience matter? Journal of Health Economics, 40, 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry LA, Robison J, Shugrue N, Keenan P, & Kapp MB (2009). Individual decision making in the non-purchase of long-term care insurance. The Gerontologist, 49, 560–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1985). Life course dynamics: Trajectories and transitions, 1968–1980. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fast JE, Williamson DL, & Keating NC (1999). The hidden costs of informal elder care. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 20, 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, & Choula R (2011). Valuing the invaluable: 2011 Update: The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein ES, Reid MC, Kleppinger A, Pillemer K, & Robison J (2012). Are baby boomers who care for their older parents planning for their own future long-term care needs? Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 24, 29–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry R, & Passel J (2014). In post-recession era, young adults drive continuing rise in multi-generational living (Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends project; ). Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/07/17/in-post-recession-era-young-adults-drive-continuing-rise-in-multi-generational-living/ [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski DC, Stevenson DG, & Cornell PY (2012). Assisted living expansion and the market for nursing home care. Health Services Research, 47, 2296–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hareven T (1994). Aging and generational relations: A historical and life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 20, 437–461. [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith C, & Shippee T (2015). Expectations about future use of long-term services and supports vary by current living arrangement. Health Affairs, 34, 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiu-Fang H, & Shannon S (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymowitz KS, Carroll JS, Wilcox WB, & Kaye K (2013). Knot yet: The benefits and costs of delayed marriage in America. Charlottesville: National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RW, Tooney D, & Wiener JM (2007). Meeting the long-term care needs of the baby boomers: How changing families will affect paid helpers and institutions. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=311451 [Google Scholar]

- Kaye HS, Harrington C, & LaPlante M (2010). Long-term care: Who gets it, who provides it, who pays, and how much? Health Affairs, 29, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper P, Komisar HL, & Alecxih L (2005). Long-term care over an uncertain future: What can current retirees expect? Inquiry, 42, 335–350. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_42.4.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konetzka T (2014). The hidden costs of rebalancing long-term care. Health Services Research, 49, 771–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim H, & Tanenbaum S (2006). Medicaid and family wealth transfer. The Gerontologist, 46, 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R (2005). The structure of the life course: Classic issues and current controversies. Advances in Life Course Research, 9, 3–24. doi: 10.1016/S1040-2608(04)09001-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KU (2009). New directions in life course research. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MetLife Mature Market Institute. (2009). Long-term care IQ. Retrieved from https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/consumer/long-term-care-essentials/mmi-long-term-care-iq-removing-myths-survey.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Passel J, & Cohn D (2008). U.S. population projections: 2005–2050 (Pew Research Center Social & Demographic Trends; ). Retrieved from http://pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/85.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Robison J, & Moen P (2000). A life-course perspective on housing expectations and shifts in late midlife. Research on Aging, 22, 499–532. [Google Scholar]

- Robison J, Shugrue N, Fortinsky RH, & Gruman C (2013). Long-term supports and services planning for the future: Implications from a statewide survey of baby boomers and older adults. The Gerontologist, 54, 297–313. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S (2007). The decline of intergenerational coresidence in the United States, 1850 to 2000. American Sociological Review, 72, 964–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaber P, & Stum S (2007). Factors impacting group long-term care insurance enrollment decisions. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28, 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration. (2014). Life tables for the United States social security area 1900–2100. Retrieved from http://www.ssa.gov/oact/NOTES/as120/LifeTables_Body.html [Google Scholar]

- Sperber NR, Voils CI, Coe NB, Konetzka RT, Boles J, & Van Houtven CH (2014). How can adult children influence parents’ long-term care insurance purchase decisions? The Gerontologist. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujvari K (2012). Long-Term Care Insurance: 2012 Update. Washington, DC: AARP. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent GK, & Velkoff VA (2010). The next four decades: The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J, Khatusky G, Greene A, Thach T, Allaire B, & Brown D (2015). Long-term care awareness and planning: What do Americans want? Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/LTCF/Awareness.cfm [Google Scholar]