Abstract

Cellular senescence is a stable growth arrest that is implicated in tissue ageing and cancer. Senescent cells are characterized by an upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, which is termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). NAD+ metabolism influences both tissue ageing and cancer. However, the role of NAD+ metabolism in regulating the SASP is poorly understood. Here we show that nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme of the NAD+ salvage pathway, governs the proinflammatory SASP independent of senescence-associated growth arrest. NAMPT is regulated by HMGAs during senescence. The HMGAs/NAMPT/NAD+ signaling axis promotes the proinflammatory SASP through enhancing glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration. HMGAs/NAMPT promotes the proinflammatory SASP through NAD+-mediated suppression of AMPK kinase, which suppresses p53-mediated inhibition of p38MAPK to enhance NFκb activity. We conclude that NAD+ metabolism governs the proinflammatory SASP. Given the tumor-promoting effects of the proinflammatory SASP, our results suggest that anti-ageing dietary NAD+ augmentation should be administered with precision.

Introduction

Cellular senescence was initially identified as a loss of proliferative capacity after extended culture, which is known as replicative senescence (RS) 1. In addition, senescence can be induced by a number of stresses, including activation of oncogenes or damage induced by chemotherapeutics 2, 3. RS is thought to have evolved to limit cancer growth, and oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) underscores the tumor suppressive role of senescence, while the eventual RS of non-cancerous cells may contribute to tissue ageing 2, 4. Senescent cells also have non-cell autonomous activities exemplified by secretion of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which is termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) 2. The SASP plays a context dependent role in cancer 2. The net effect of SASP is mostly detrimental in tumors because it promotes several hallmarks of cancer including tumor growth, while the elimination of senescent cells delays tumorigenesis 5. SASP gene transcription is temporally regulated 6, 7, where the first wave of SASP factors such as TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 are typically immunosuppressive. In contrast, the second wave of the SASP often consists of proinflammatory factors such as IL1β, IL-6, and IL-8 6, 7.

High mobility group proteins are non-histone chromatin-bound proteins that regulate gene transcription by altering chromatin architecture 8, 9,. For example, the high mobility group A (HMGA) proteins such as HMGA1 and HMGA2 bind to DNA without sequence specificity to increase accessibility of the chromatin to transcription factors 10. HMGAs are often overexpressed in cancer and high levels portend a poor prognosis in a number of cancer types 8. HMGA proteins promote senescence through regulating chromatin structure 11. However, HMGAs’ target genes and whether HMGAs play a role in regulating SASP during senescence are unknown.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) plays a critical role in tissue ageing and cancer 12, 13. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) is the rate-limiting enzyme in salvage NAD+ biogenesis 14, 15. Both NAMPT and NAD+ levels are decreased during RS and tissue ageing 12, 13. In addition, cells that undergo mitochondrial dysfunction-associated senescence have lower NAD+/NADH ratios 16. Indeed, supplementation with NAD+ precursors such as nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR) may represent a preventive approach for ageing and its associated pathophysiological disorders 12, 13, 17, 18. Notably, such supplements for NAD+ augmentation have recently entered clinical trials as nutraceuticals. In addition, NAMPT and NAD+ play a crucial role in cancers and NAD biosynthesis is often upregulated in tumor cells 13. However, the role of NAMPT-regulated NAD+ biogenesis in regulating the SASP is unknown. Here we show that the NAMPT-regulated NAD+ biogenesis pathway governs the strengths of proinflammatory SASP observed during senescence.

Methods

Cells and culture conditions

IMR90 human diploid fibroblasts were cultured according to ATCC under low oxygen tension (2%) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM, 4.5 g/L glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, nonessential amino acids, and sodium bicarbonate. All experiments were performed on IMR90 fibroblasts between population doublings #25 and 35 unless indicated otherwise. IMR90 fibroblasts cultured to the population doublings of 30 and 90 were considered early and late passage, respectively.

Retrovirus and lentivirus production and infection

Retrovirus was produced as previously described 37 using Phoenix cells (Dr. Gary Nolan, Stanford University). Lentivirus was produced using the ViraPower kit (Invitrogen) based on manufacturer’s instructions in the 293FT human embryonal kidney cell line. IMR90 fibroblasts infected with viruses encoding puromycin or blasticidin resistance gene were selected using 3 μg/mL of puromycin or 10 μg/mL of blasticidin.

Reagents, plasmids and antibodies

The following antibodies were purchased from the indicated suppliers: rabbit monoclonal anti-AMPK (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 2532, Clone 40H9, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (Sigma, Cat. No. A5441, Clone AC-15, 1:10000 for immunoblot), rabbit polyclonal anti-Cyclin A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. No. sc-751, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (Sigma, Cat. No. F3165, Clone M2, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-γH2Ax (Millipore, Cat. No. 05–636, Clone JBW301, 1:1000 for immunoblot), rabbit polyclonal anti-H3K27Ac (Millipore, Cat. No. 07–360, 1:1000 for ChIP), rabbit polyclonal anti-H3K4Me1 (Abcam, Cat. No. ab8895, 1:1000 for ChIP), rabbit monoclonal anti-HMGA1 (Abcam, Cat. No. 129153, Clone EPR7839, 1:1000 for immunoblot and ChIP), rabbit polyclonal anti-HMGA2 (Abcam, Cat. No. 97276, 1:1000 for immunoblot), rabbit polyclonal anti-IgG (Santa Cruz, Cat. No. sc-2027, 1:1000 for ChIP), rabbit polyclonal anti-NAMPT (Bethyl Laboratories, Cat. No. A300–372A, 1:1000 for immunoblot), rabbit monoclonal anti-p-AMPK (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 4188, Clone D79.5E,1:1000 for immunoblot), rabbit polyclonal anti-p-p38 (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 9211, 1:1000 for immunoblot), rabbit polyclonal anti-p-p53 (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 9284, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-p-p65 (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 3036, Clone 7F1, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-p16 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. No. sc-56330, Clone JC8, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-p38 (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 9228, Clone L53F8, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-p53 (Millipore, Cat. No. OP43, Clone DO-1, 1:1000 for immunoblot), rabbit monoclonal anti-p65 (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 8242, Clone D14E12, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-RAS (Becton Dickinson, Cat. No. 610001, Clone 18/RAS, 1:1000 for immunoblot), mouse monoclonal anti-V5 (Invitrogen, Cat. No. MA5–15253, Clone E10/V4RR, 1:1000 for immunoblot).

The pBABE-puro-H-RASG12V, pBABE-puro-Empty, and pBABE-BRAFV600E plasmids were purchased from Addgene. The following pLKO.1-short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) were obtained from the Molecular Screening Facility at the Wistar Institute: shHMGA1#1 (TRCN0000018949, sense sequence: CAACTCCAGGAAGGAAACCAA), shHMGA1#2 (TRCN0000018950, sense sequence: CCAGCGAAGTGCCAACACCTA), shHMGA2#1 (TRCN0000021965, sense sequence: GCCACAACAAGTTGTTCAGAA), shHMGA2#2 (TRCN0000021967, sense sequence: AGGAGGAAACTGAAGAGACAT), shNAMPT#1 (TRCN0000116177, sense sequence: CCACCTTATCTTAGAGTTATT), and shNAMPT#2 (TRCN0000116180, sense sequence: GTAACTTAGATGGTCTGGAAT). The following pLX304-based overeexpression were obtained from the Molecular Screening Facility at the Wistar Institute: pLX304-HMGA1 (clone ID# ccsbBroad304_00757) and pLX304-NAMPT (clone ID# ccsbBroad304_07557). The catalytically inactive NAMPT/H247A was constructed by PCR-based mutagenesis as previous described 38 using the following primers: NAMPT/H247A (forward: TTACCTGTTCCAGGCTATTCTGTTCCAGCAGCAGAAGCCAGTACC; reverse: TTAGGGTCCTTGAAGACGTTAATCCCAA). This construct was subcloned into the lentiviral plasmid pLVX-Puro (Prromega) at BamHI1 and Xho1 sites using standard molecular cloning protocols.

The following compounds were purchased from the indicated suppliers: FK866 (Millipore, Cat. No. 48–190-82, 1nM for in vitro studies in cell culture), NAM (Sigma, Cat. No. N0636, 1 mM for in vitro studies in cell culture), NMN (Sigma, Cat. No. N3501, 1mM for in vitro studies in cell culture), Compound C (Selleckchem, Cat. No. S7840, 50 nM for in vitro studies in cell culture), and Etoposide (Sigma, Cat. No. E1383, 50 μM for in vitro studies in cell culture to induce senescence). Gallotannin was provided as a gift from Dr. Joseph Baur (University of Pennsylvania) and use at 5 μM for in vitro studies in cell culture.

Immunoblotting

Protein was isolated for immunoblotting by lysing cells in 1x sample buffer (10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 0.1 M DTT, and 62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8). Following heat incubation at 95°C for 10 min, protein extract concentration was determined using Bradford assay. Equal protein concentration was used in an SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 100 volts for 2 hours at 4°C. Following transfer, membranes were blocked using 5% nonfat milk in TBS/0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for one hour at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in 4% BSA/TBS + 0.025% sodium azide. Following incubation with the primary antibody, membranes were washed with TBST for 5 minutes at room temperature three times and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) made up in 5% nonfat milk for one hour at room temperature. Following incubation with the secondary antibody, membranes were washed with TBST for 5 minutes at room temperature three times and then incubated with SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher) for visualization on film.

ChIP, ChIP-seq and bioinformatic analysis

For ChIP, cells were fixed using 1% formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher) for 5 minutes at room temperature and then incubated with 2.5 M glycine for an addition 5 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed with cold PBS twice and then lysed using ChIP lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes- KOH, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% deoxycholate with 0.1 mM PMSF and the EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail). Following incubation on ice for ten minutes, the lysed samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for three minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in a second lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM EGTA with 0.1 mM PMSF and the EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail) and incubated at room temperature for ten minutes before centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for five minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in a third lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% DOC, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 0.5% N-lauroylsarcosine with 0.1 mM PMSF and the EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail) and sonicated using a Biorupter (Diagenode) for fifteen minutes (thirty seconds on and one minute off). Each ChIP sample received 10% Triton X-100 and was centrifuged at maximum speed for fifteen minutes at 4°C. The supernatant of each ChIP sample was collected for quantification of DNA and precleared using 15 μl of protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher) for one hour at 4°C. Following centrifugation at maximum speed for fifteen minutes at 4°C, the supernatant of each sample is incubated with 50 μl of antibody-bead conjugate solution for immunoprecipitation overnight on a rotator at 4°C. The next day, each ChIP sample was washed on a rotator for fifteen minutes at 4°C. using ChIP lysis buffer, ChIP lysis buffer containing 0.65 M NaCl, wash buffer (250 mM LiCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5% DOC, 0.5% NP-30, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0), and TE (1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 and 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). Subsequently, DNA was eluted by incubation of the beads with TE + 1% SDS for fifteen minutes at 65°C. The samples were then incubated overnight at 65°C to reverse cross-linking. The next day, the samples were incubated 1 mg/mL of proteinase K for five hours at 37°C. Lastly, the DNA was purified from each sample using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean Up kit (Promega). Quantitative PCR was performed on the immunoprecipitated DNA using iTaq Universal SYBR Green (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Isotype-matched immunoglobulin G served as a negative control.

Established senescent IMR90 cells induced by oncogenic RAS were prepared for ChIP-seq using 5 μL of anti-HMGA1 antibody (Abcam, Cat. No. 129153) or anti-HMGA2 (Abcam, Cat. No. 97276). Preparation of the ChIP-seq libraries for next-generation sequencing was performed using the NEB Next Ultra DNA Library Prep kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) from 100 nanograms of ChIP DNA. Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) was used to amplify the ChIP-seq libraries (6 cycles). The ChIP-seq libraries were sequenced in a 75 base pair single-end run on the Next Seq 500 (Illumina).

ChIP-seq data for HMGA1 in RAS-induced senescent cells and vector control expressing IMR90 cells was aligned to the hg19 version of human genome using bowtie algorithm 39. Peaks specific to RAS condition compared to vector control were identified using the HOMER algorithm with ‘-factor’ option and peaks with significantly higher signal (FDR<10%, fold>4) were considered as RAS-specific 40. Raw RNA-seq data for IMR90 RAS-induced senescence and control conditions was downloaded from GEO (under accession code: GSE74324) 41. Data was aligned against hg19 version of genome and Ensemble GRCh37 transcriptome using STAR 42. RSEM v1.2.12 software was used to estimate gene level read counts and FPKM values 43. Deseq2 was used to estimate significance of differential expression difference between the two experimental groups 44. Coding genes that were significantly upregulated in RAS compared to control (FDR<5%) and had a RAS-specific HMGA1 peak within 1kb from TSS were considered.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was performed following RNA extraction using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher) and DNase treatment (RNeasy columns by Qiagen) of the samples. RNA expression was determined using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green One-step kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher). For analysis of human genes, β−2-microglobulin (B2M) was used as an internal control and fold change was calculated using the 2-ΔΔC(t) method for all analyses. Primer sequences for the indicated genes are: NAMPT (forward: GCCAGCAGGGAATTTTGTTA; reverse: TGATGTGCTGCTTCCAGTTC), IL1β (forward: AGCTCGCCAGTGAAATGATGG; reverse: GTCCTGGAAGGAGCACTTCAT), IL6 (forward: ACATCCTCGACGGCA TCTCA; reverse: TCACCAGGCAAGTCTCCTCA), IL8 (forward: GCTCTGTGTGAAGGTGCAGT; reverse: TGCACCCAGTTTTCCTTGGG), B2M (forward: GGCATTCCTGAAGCTGACA; reverse: CTTCAATGTCGGATGGATGAAAC), HMGA1 (forward: CAACTCCAGGAAGGAAACCA; reverse: AGGACTCCTGCGAGATGC), HMGA2 (forward: ACCAGGAAATGGCCACAACA; reverse: CCAACTGCTGCTGAGGTAGAA), TGFβ1 (forward: CAGAAATACAGCAACAATTCC; reverse: CTGAAGCAATAGTTGGTGTC), TGFβ3 (forward: TGCGTGAGTGGCTGTTGAGAAG; reverse: CCATTGGGCTGAAAGGTGTGAC), CEBP (forward: CTTCAGCCCGTACCTGGAG; reverse: GGAGAGGAAGTCGTGGTGC), IL10 (forward: TGCCTTCAGCAGAGTGAAGA; reverse: GCTTGGCAACCCAGGTAA) and TNFα (forward: CAGCCTCTTCTCCTTCCTGAT; reverse: GCCAGAGGGCTGATTAGAGA).

For mouse genes, mouse cyclophilin A expression was used as an internal control and fold change was calculated using the 2-ΔΔC(t) method for all analyses. Primer sequences for the indicated genes are: mouse p16 (forward: CGGTCGTACCCCGATTCAG; reverse: GCACCGTAGTTGAGCAGAAGAG), mouse p21 (forward: TTGCACTCTGGTGTCTGA; reverse: GTGGGCACTTCAGGGTTT), and mouse cyclophilin A (forward: GGGTTCCTCCTTTCACAGAA; reverse: GATGCCAGGACCTGTATGCT). mouse IL-6 (forward: GCTACCAAACTGGATATAATCAGGA; reverse: CCAGGTAGCTATGGTACTCCAGAA), mouse IL-8 (forward: AGAGGCTTTTCATGCTCAACA ; reverse: CCATGGGTGAAGGCTACTGT), and mouse IL-1B (forward: TGTGCAAGTGTCTGAAGCAGC; reverse: TGGAAGCAGCCCTTCATCTT).

Flow Cytometry

Samples were incubated with 5 μM 2-NBDG (Invitrogen) for two hours for assessment of glucose uptake, trypsinized and washed with PBS, and run on an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Analysis was performed using FlowJo Software.

Colony Formation Assay

Cells were cultured in six-well plates (3,000 cells/well) for two weeks before staining with 0.05% crystal violet for visualization. Analysis was performed based on integrated density using NIH ImageJ software.

SA-β-gal staining

Staining was performed as previously described 45. Cells were first fixed using 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS then washed twice with PBS. Cells were then incubated in X-Gal solution (150 mM NaCl, 40 mM Na2HPO4, pH 6.0, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, and 1 mg/ml X-gal) overnight at 37°C in a non-CO2 incubator. Pancreatic tissue samples were freshly frozen in OCT compound. Frozen sections of pancreatic tissue were fixed with 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 5 minutes, washed with PBS, and stained at 37°C overnight in X-Gal solution. After counterstaining with Nuclear Fast Red solution (Ricca), slides were subjected to an alcohol dehydration series and mounted with Permount (Fisher). Slides were examined on Zeiss AxioImager A2.

NFκB reporter assay

NFκB activity was determined using the NFκB reporter plasmid (Addgene, plasmid #49343) and normalized based upon transfection efficiency using renilla luciferase (pRL-SV40, Promega, Plasmid #E223A). Plasmids were co-transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (Invitrogen) and assayed for luminescence using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Cat. No. E1910). Luminescence was measured using a Victor X3 2030 Multilabel Reader (Perkin Elmer).

Metabolite tracing and measurements

For steady state metabolite measurements, cells were seeded into 10 cm dishes at the concentration of 1 × 106 cells per dish. Cells were washed twice using cold PBS and metabolites were extracted using extraction solution (80% LC/MS-grade methanol, 20% Milli-Q water, and 0.1 μM internal standard). Samples were processed in a 4°C cold room and incubated on dry ice for 10 minutes before being vortexed for 2 minutes. Lastly, samples were centrifuged at maximum speed for 15 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was analyzed through LC-MS/MS. Targeted quantitation of steady-state metabolites was performed on a SCIEX 5500 QTRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a Turbo V source and coupled to a Shimadzu Nexera UHPLC system. 5μl of each sample were injected onto a ZIC-pHILIC 2.1-mm i.d × 150 mm column (EMD Millipore). Buffer A was 20 mM ammonium carbonate, 0.1% ammonium hydroxide; and buffer B was acetonitrile. The chromatographic gradient was run at a flow rate of 0.150 ml/min for 80–20% B over 20 min, 20–80% B over 0.5 min, and hold at 80% B for 7.5 min. Metabolites were targeted in positive and negative ion modes separately for a total of 161 selected reaction monitoring transitions. Electrospray ionization voltage was +5500 V in positive ion mode and −4500 V in negative ion mode. The dwell time was 20 ms per transition in positive ion mode (46 total transitions), and 5 ms per transition in negative ion mode (115 total transitions). A minimum of 9 data points was acquired per detected metabolite. Peak areas from the total ion current for each metabolite-selected reaction monitoring transition were integrated using the MultiQuant v3.0.2 software (SCIEX). The metabolic tracing data are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

For stable isotope tracer analysis using [13C6]-glucose, cells were seeded at the concentration of 3 × 105 cells per well and incubated with 25 mM of the [13C6]-glucose tracer in glucose-free medium for 1 and 6 hours. Following incubation, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 500 ul of extraction solution for 5 minutes at 4°C. The extraction solution from each sample was collected and centrifuged at max speed for 10 minutes at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was used for analysis. Metabolite measurements were normalized based upon protein concentration. LC-MS metabolite flux analysis was performed on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer equipped with a HESI II probe and coupled to a Shimadzu Nexera UHPLC system. Column and LC conditions are as described above. The mass spectrometer was operated in full-scan, polarity switching mode with the spray voltage set to 3.2 kV in positive ion mode and 2.5 kV in negative ion mode. The heated capillary was set at 275°C, the HESI probe at 350°C, and the S-lens RF level at 45. The gas settings for sheath, auxiliary and sweep were 40, 10 and 1 unit, respectively. The mass spectrometer was set to repetitively scan m/z from 70 to 1000, with the resolution set at 70,000, the AGC target at 1E6, and the maximum injection time at 80 ms. Metabolite identification and quantitation were performed with TraceFinder (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The NAD+/NADH ratio was determined using the NAD/NADH-Glo Assay (Promega, G9071) according to manufacturer’s standard protocol. The ADP/ATP ratio was determined using the ADP/ATP Ratio Assay kit (Sigma, Cat. No. MAK135) according to manufacturer’s standard protocol. Luminscence signal from the NAD/NADH-Glo Assay and ADP/ATP Ratio Assay kits were measured using a Victor X3 2030 Multilabel Reader (Perkin Elmer). Extracellular acidification and cellular oxygen consumption rates were measured using the Glycolysis Stress Test Kit a Seahorse Bioanalyzer XFe96 (Agilent Technologies) according to manufacturer’s standard protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded at the concentration of 30,000 cells per well in DMEM the day before running the assay. The next day, the cells were incubated with DMEM devoid of glucose and sodium pyruvate (Sigma, Cat. No. R1383 supplemented with 10% FBS) and loaded on the Seahorse Bioanalyzer XFe96. Working concentrations of compounds used within the glycolysis stress test kit are as followed: glucose at 10 mM, oligomycin A at 2 μM, and 2-deoxyglucose at 50 mM. ECAR is reported in mpH/min while OCR is reported in pMoles/min. Samples were normalized based upon protein concentration.

Coculture Experiments

Senescent fibroblasts were seeded into 6 well plates to generate a 95% confluent fibroblast monolayer and incubated in a serum-deficient condition for 48 hours. Luciferase-expressing ovarian cancer cells (TOV21G cell line) were seeded on top of the fibroblasts lawn and incubated for eight days under the serum-deficient condition. Cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of doxycycline for inducible knockdown of NAMPT in the presence or absence of NAM. Cells were assayed for luminescence using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Cat. No. E1910). Luminescence was measured using a Victor X3 2030 Multilabel Reader (Perkin Elmer).

Cytokine Secretion Measurements

The antibody array for secreted factors was performed using the Quantibody Human Inflammation Array 3 kit (QAH-INF-3) by RayBioTech based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, conditioned media was generated from cells following PBS wash and incubation in serum-free DMEM for 48 hours. Conditioned media was filtered (0.2 μm) and incubated on the array overnight at 4 °C. Following incubation, the array was washed five times with wash buffer I and then two times with wash buffer II at room temperature. The array was then incubated with the biotinylated antibody cocktail for two hours at room temperature before being washed five times with wash buffer I and then two times with wash buffer II at room temperature. The array was then incubated with Cy3 dye-conjugated streptavidin and incubated in the dark at room temperature for one hour. Following incubation, the array was washed five times with wash buffer I and then washed two times with wash buffer II before allowing to dry at room temperature in the dark. Cy3 signal was measured using an Amersham Typhoon imaging system and normalized to cell number from which the conditioned media was generated.

In vivo Pancreatic Cancer Mouse Model

All animal procedures were approved by the NYU School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. LSL-KRasG12D and p48-Cre mice were gifts from Dr. T. Jacks (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) and Dr. D. Bar-Sagi (NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA), respectively. Mice are on a mixed background. At 8 weeks of age, mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of either 500 mg/kg NMN or an equal volume of PBS for 13 days. Where indicated, mice were treated at 8 weeks of age with 25 mg/kg FK866 daily. Mice were sacrificed on day 14, and pancreas was harvested for downstream analysis.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Mouse pancreata were fixed in IHC Zinc fixative (BD Pharminogen) for 48 hours and processed for paraffin embedding. Histological, Trichrome, and immunohistochemical staining was performed at the NYU School of Medicine Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory. The following antibodies were used: anti-F4/80 (clone ND, Cell Signaling) and anti-CD3 (clone SP7, Spring Biosciences). Percent acinar area was calculated by dividing the number of pixels that constituted normal acinar area and dividing by the total number of pixels that constituted tissue. Percent trichrome area was calculated by dividing the number of blue pixels by the total number of tissue pixels. F4/80 was calculated by dividing the number of brown pixels by the total number of tissue pixels. CD3 was calculated by counting the number of CD3+ cells per field of view and averaging the number over 15 fields.

Xenograft Mouse Model

The protocols were approved by the Wistar Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Cells (TOV21G: senescent fibroblast = 1:1 at 2 × 106 cells) were suspended in 100 μL PBS:Matrigel (1:1) and unilaterally injected subcutaneously into the right dorsal flank of 6–8 week-old female immunocompromised non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) gamma (NSG) mice. The mice were administered DOX-containing food following injection of cells. Four days after injection of cells, the mice (n=9 mice/group) were treated with vehicle control, NAM (500 mg/kg; intraperitoneal injection; every other day) for 17 days. NAM was dissolved in water. Tumor size was measured on the indicated days. Tumor size was determined using the equation: tumor size (mm3) = [d2 x D]/2, where d and D are the shortest and the largest diameter.

Statistics and Reproducibility

Results are representative of a minimum of three independent experiments. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad). The Student’s t test was performed to determine P values of the raw data where P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Code Availability

The software and algorithms for data analyses used in this study are all well established from previous work and are referenced throughout the manuscript. No custom code was used in this study.

Data Availability

ChIP-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number: GSE111841. Raw RNA-seq data for RAS-induced senescence and control conditions in IMR90 cells was downloaded from GEO (under accession code: GSE74324) 41. For correlation between NAMPT and SASP genes in human laser capture and microdissected PanIN lesion samples, gene expression data was obtained from GEO (under accession code: GSE43288) 1.

Source data used for statistical analyses of Figures 1a-b, 1e, 1h-i, 2b-c, 2e-f, 2h, 2j, 3a-n, 4a, 4c, 4e-f, 4h, 4j, 4l-m, 4p, 5a, 5d-g, 6b-e, 6g-i, 7b-c, 7e-f, 7g, and Supplementary Figs 2c-f, 2h-j, 2l-n, 2p-q, 3a-f, 3h, 4, 5a-d, 6b-g, 6i, 6k-l, 7a-b and 7d-e are provided as Supplementary Table 1 (Statistics source data). All other data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request.

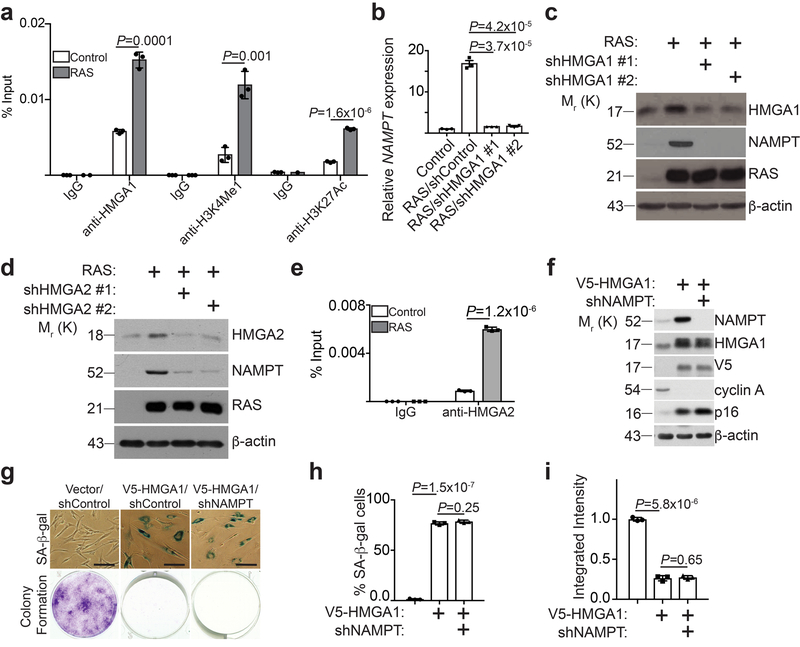

Figure 1. HMGA proteins regulate NAMPT expression.

a, ChIP analysis for the enhancer of NAMPT gene identified by HMGA1 ChIP-seq using the indicated antibodies or an isotype matched IgG control during OIS (n = 3 independent experiments). b,c, HMGA1 in fully established senescent cells was knocked down using two independent short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs). Expression of NAMPT mRNA was determined by qRT-PCR (b) (n = 3 independent experiments), or the indicated proteins were determined by immunoblot (c). d, In established senescent cells, HMGA2 was knocked down using two independent shRNAs and expression of the indicated proteins was determined by immunoblot. e, ChIP analysis for the enhancer of NAMPT gene identified by HMGA1 ChIP-seq using an anti-HMGA2 antibody or an isotype matched IgG control during OIS (n = 3 independent experiments). f,g, Cells with or without ectopic V5-tagged HMGA1 expression with or without NAMPT knockdown were examined for the expression of the indicated proteins by immunoblot (f), or subjected to SA-β-gal staining or colony formation (g), scale bar = 100 μm. The percentage of SA-β-gal positive cells (h) and the integrated intensity of the colonies formed by the indicated cells (i) were quantified using NIH Image J software (n = 3 independent experiments). All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

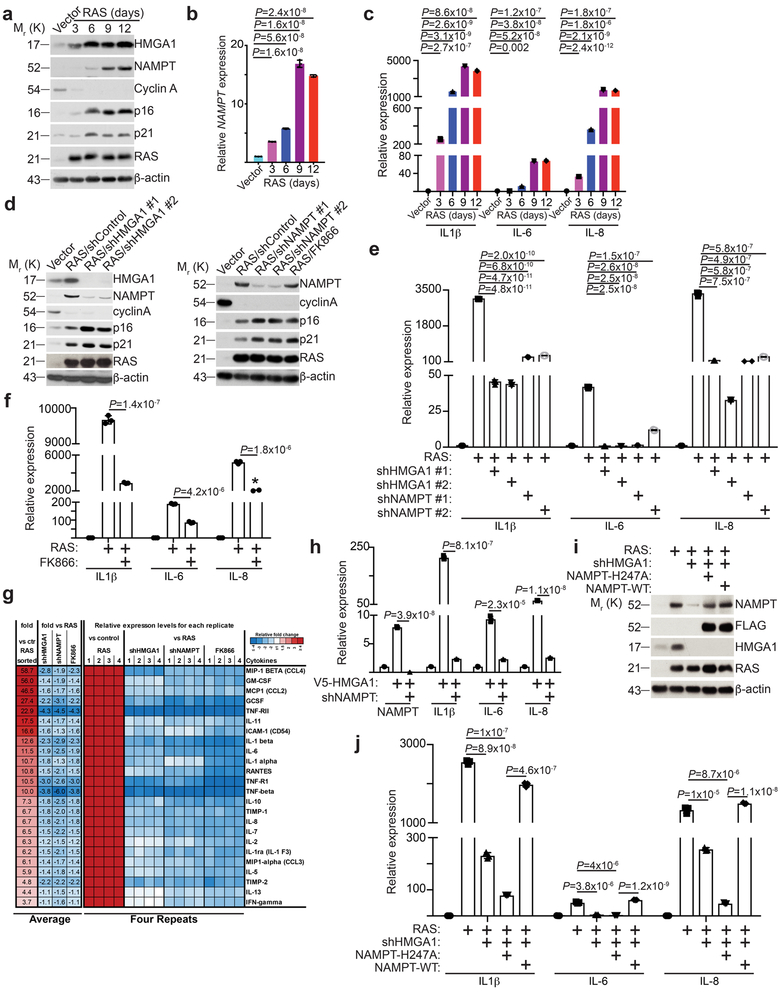

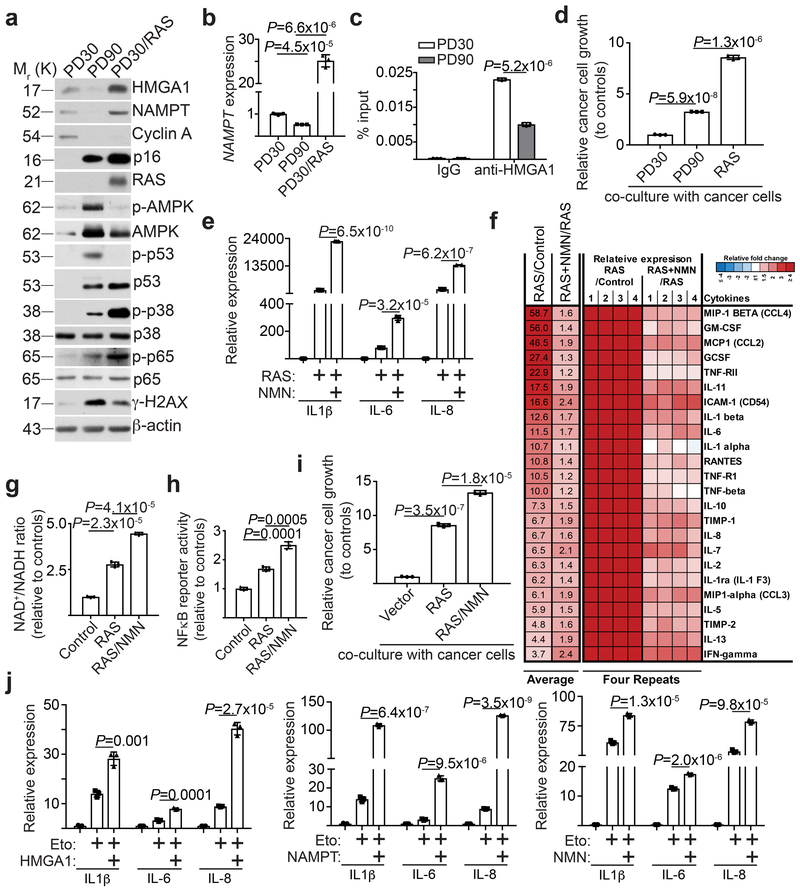

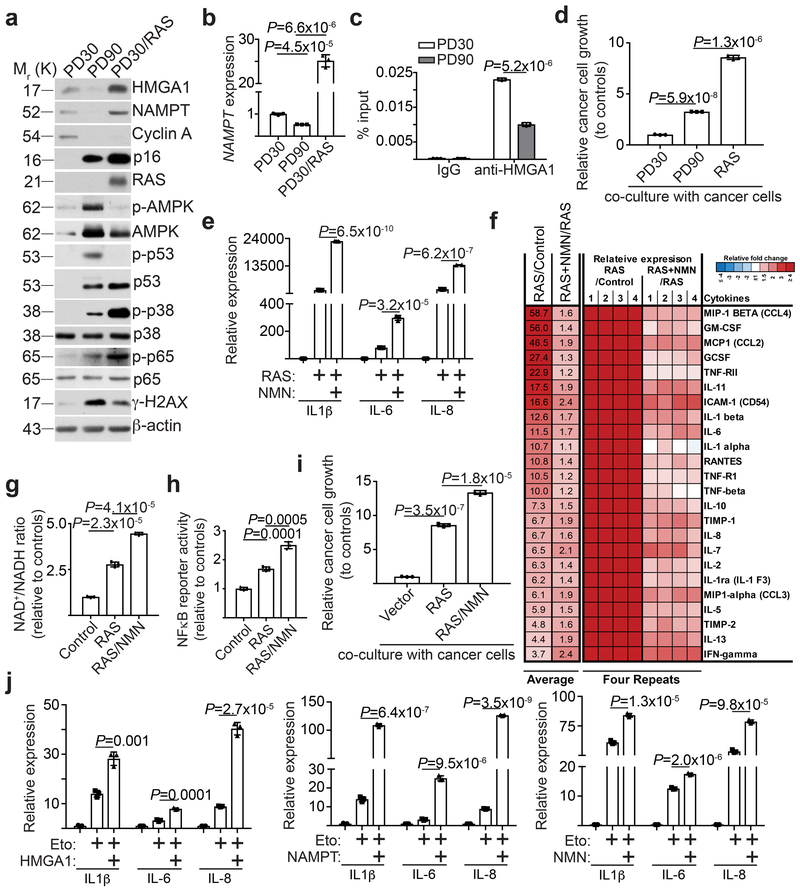

Figure 2. HMGA1-mediated NAMPT expression drives the proinflammatory SASP.

a-c, The expression of indicated proteins in cells induced to senesce by oncogenic RAS at the indicated time points was analyzed by immunoblot (a). Expression of NAMPT (b) and the indicated proinflammatory SASP genes (c) were determined by qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). d-g, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down using the indicated shRNAs. The NAMPT activity was also inhibited by FK866. The expression of the indicated proteins was determined by immunoblot (d). Expression of SASP genes was determined using quantitative RT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments) (e,f). g, The secretion of soluble factors under the indicated conditions were detected by antibody arrays. Heat map indicates fold change in comparison to the control or RAS condition. Relative expression level per replicate and average fold change differences are shown (n = 4 independent experiments). h, V5-HMGA1 overexpressing cells had NAMPT knocked down and expression of NAMPT and the indicated SASP genes were determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). i-j, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 was knocked down with or without ectopic expression of a FLAG-tagged wild type or catalytically-inactive NAMPT. The expression of the indicated proteins was determined by immunoblot (i). Expression of the indicated SASP genes was determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments) (j). All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

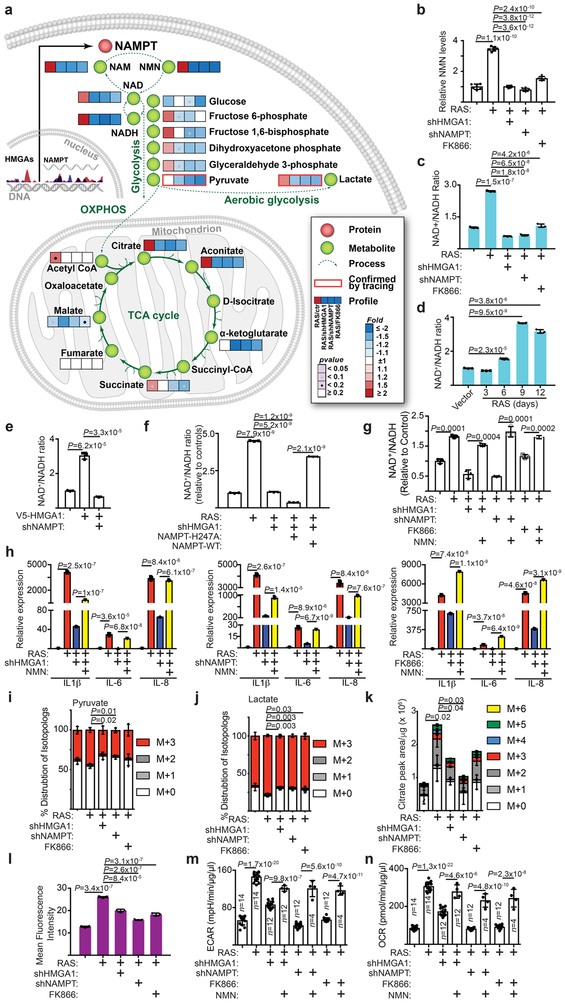

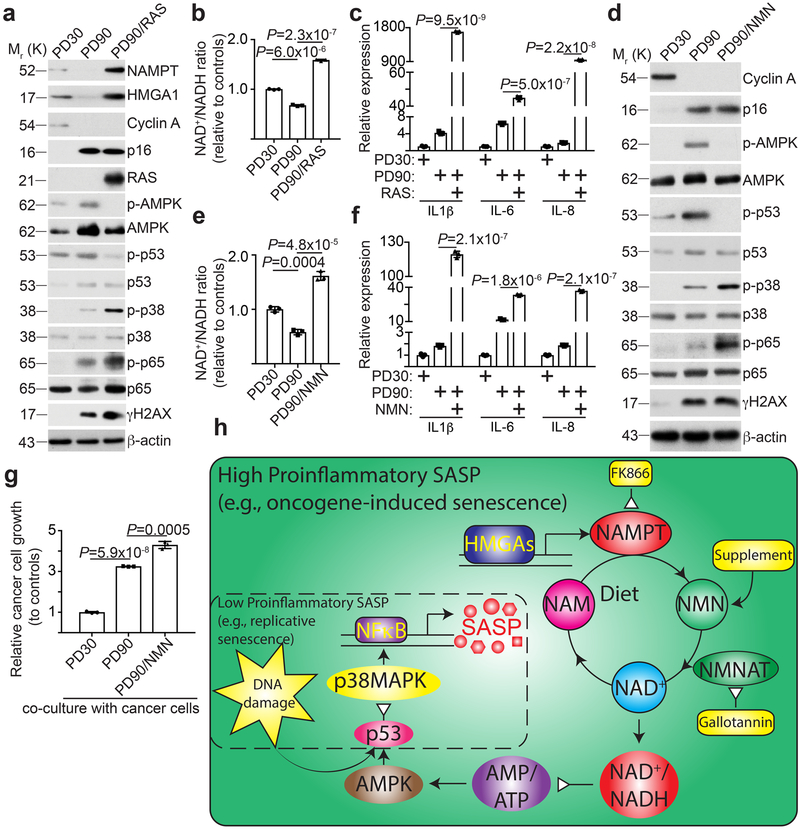

Figure 3. NAD+ metabolism drives proinflammatory SASP.

a-c, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down using the indicated short hairpin RNAs. The NAMPT activity was also inhibited by FK866. Steady-state metabolite levels were measured by LC-MS/MS. Heat map indicates fold change in comparison to the control condition (a) (n=6 independent experiments). NMN (b) (n=6 independent experiments) and NAD+/NADH ratio (c) were determined in the indicated cells. d, Cells were induced to senesce by oncogenic RAS and analyzed for the NAD+/NADH ratio at the indicated time points. e, Cells with or without ectopic V5-tagged HMGA1 expression with or without NAMPT knockdown were examined for the NAD+/NADH ratio. f, The NAD+/NADH ratio was determined in established senescent cells with or without HMGA1 knockdown with or without ectopic expression of a FLAG-tagged wild type or catalytically-inactive NAMPT. g,h, In established senescence, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down using the indicated shRNAs. The NAMPT activity was also inhibited by FK866. Under these conditions, cells were treated with NMN and the NAD+/NADH ratio (g) and expression of the indicated SASP genes (h) were determined by qRT-PCR. i-k, Cells from the conditions as in (a) were incubated for 6 hours in the presence of 13C6-glucose and intracellular metabolites were extracted for analysis by LC-MS to evaluate glycolytic flux in the form of pyruvate (i) and lactate (j) and mitochondrial respiration rates as indicated by citrate production (k). Data were normalized based on protein concentration. l, Cells from conditions as in (a) were incubated with a fluorescent glucose analog (2-NBDG) and analyzed by flow cytometry for glucose uptake. m,n, Cells from the conditions in (g) were analyzed using Seahorse Bioanalyzer XFe96 for extracellular acidification (ECAR) (m) and oxygen consumption (OCR) (n). Data were normalized based on protein concentration. n = 3 independent experiments unless otherwise stated. All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

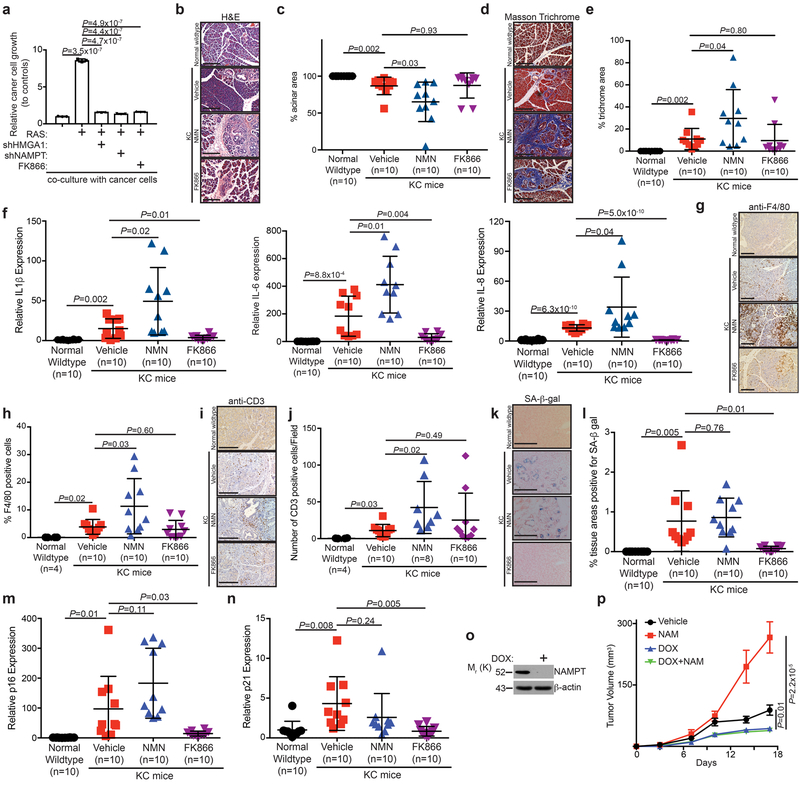

Figure 4. NMN enhances the inflammatory environment and cancer progression in vivo.

a, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down or cells were treated with FK866 to assess the effect on the growth of co-cultured luciferase-expressing TOV21G ovarian cancer cells. Cell growth was assessed by luminescence following eight days of growth. (n=3 independent experiments). b-n, Wildtype mice were compared to KC mice treated with vehicle, NMN (500 mg/kg daily), or FK866 (25 mg/kg daily). Representative H&E images of pancreas (b) and quantification of percent acinar area (c). Representative Masson trichrome staining images of pancreas (d) and quantification of percent trichrome area (e). Expression of IL1β, IL-6 and IL-8 was determined using qRT-PCR analysis (f). Representative immunohistochemical staining of infiltrating F4/80-positive immune cells (g) and quantification of percent F4/80 positive cells (h). Representative immunohistochemical staining of infiltrating CD3-positive immune cells (i) and quantification of the number of CD3 positive cells/field (j). Representative SA-β-gal staining (k) and quantification of SA-β-gal positive areas (l) in the indicated treatment groups. Expression of p16 (m) and p21 (n) was determined using qRT-PCR analysis. n=10 mice/group unless otherwise stated. Scale bar for all images is 200 μm. o, Immunoblot of the indicated protein in TOV21G cells containing doxycycline-inducible knockdown of NAMPT with or without doxycycline treatment. p, TOV21G and oncogene-induced senescent IMR90 cells were subcutaneously co-injected into the right dorsal flank of 6-8 week old NSG female mice. The mice (n=9 mice/group) were treated with vehicle control, NAM (500 mg/kg; intraperitoneal injection; every other days) for 17 days. Tumor growth in the indicated treatment groups was measured at the indicated time points. All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

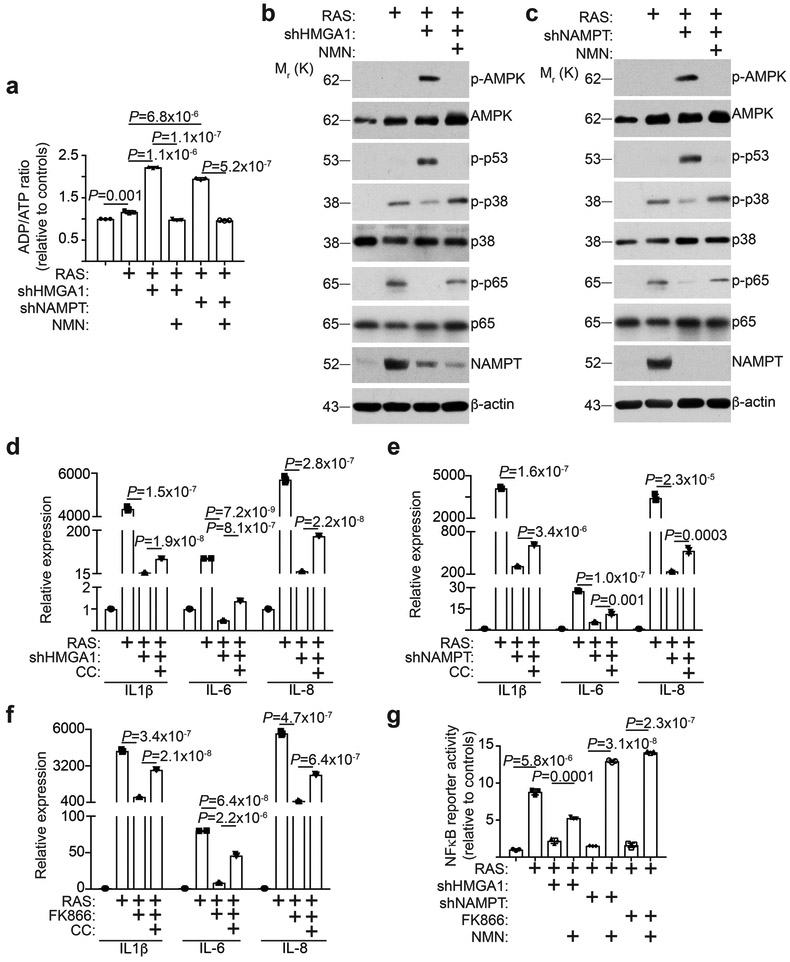

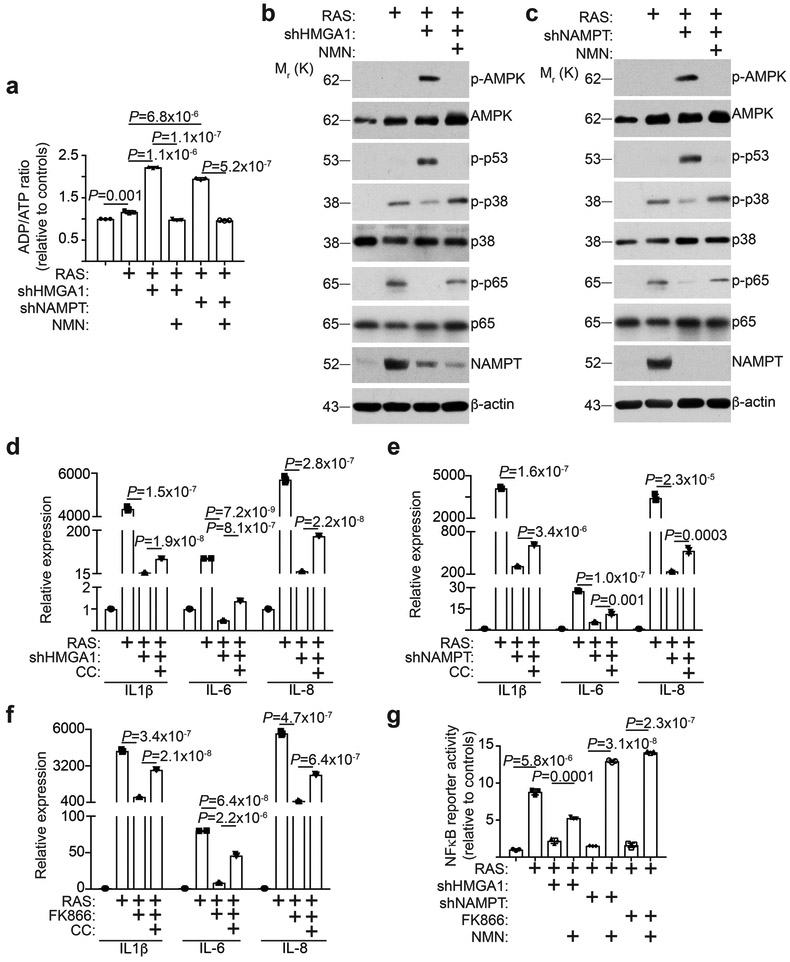

Figure 5. AMPK signaling mediates proinflammatory SASP induced by NAD+ metabolism.

a-c, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT was knocked down using the indicated shRNAs. Under these conditions, cells were treated with NMN and the ADP/ATP ratio (a) and expression of the indicated proteins by immunoblot in the indicated HMGA1 knockdown (b) or NAMPT knockdown (c) cells were determined (n = 3 independent experiments). d-f, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 (d) or NAMPT (e) was knocked down using the indicated shRNAs or treated with FK866 (f). Under these conditions, cells were treated with Compound C (CC, 50 nM), an AMPK inhibitor. Expression of the indicated SASP genes was determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). (g) In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT was knocked down using the indicated shRNAs or treated with FK866. Under these conditions, cells were treated with NMN and NFκB reporter activity was determined (n = 3 independent experiments). All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Figure 6. HMGA1/NAMPT axis regulates the strengths of SASP.

a, Cells cultured at early passage (population doubling 30, PD30), late passage (population doubling 90, PD90), and oncogene-induced senescence (PD30 expressing oncogenic RAS) were compared. Expression of the indicated proteins was determined using immunoblot. b, Expression of NAMPT mRNA in the indicated cells was determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). c, The indicated early passage and late passage cells were subjected to ChIP analysis for the NAMPT enhancer site using an anti-HMGA1 antibody. An isotype matched IgG was used as a control (n = 3 independent experiments). d, Cells from the conditions in (a) were assessed for their effects on the growth of co-cultured TOV21G cancer cells (n = 3 independent experiments). e-i, The indicated cells with or without NMN supplementation were compared. Cells were examined for expression of the indicated SASP genes using qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments) (e), secretion of soluble factors using antibody arrays (f), NAD+/NADH ratio (g), NFκb reporter activity (h), and the effects on the growth of co-cultured TOV21G cancer cells (i). The heat map for the antibody array indicates fold change in comparison to the control or RAS + NMN condition. Relative expression level per replicate and average fold change differences are shown (n = 4 independent experiments). j, TOV21G cells overexpressing HMGA1 or NAMPT, or supplemented with NMN, were induced to senesce using etoposide (50 μM for 48 hours) and expression of the indicated SASP genes was determined by qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Figure 7. NAD+ metabolism governs the strengths of SASP.

a-c, Cells cultured at early passage (population doubling 30), senescent late passage (population doubling 90), and late passage expressing oncogenic RAS (population doubling 90) were compared. Cells were examined for expression of the indicated proteins by immunoblot (a), NAD+/NADH ratio (b) and expression of the indicated SASP genes using qRT-PCR (c) (n = 3 independent experiments). d-g, The indicated cells with or without NMN supplementation were compared. Cells were examined for the indicated proteins by immunoblot (d), NAD+/NADH ratio (e), expression of the indicated SASP genes using qRT-PCR (f), and the effect on the growth of co-cultured TOV21G cancer cells (g). n = 3 independent experiments. All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. h, Schematic of the mechanism by which NAD+ metabolism drives the high-proinflammatory SASP. A high-proinflammatory SASP accompanies oncogene-induced senescence that is driven by HMGAs-mediated NAMPT expression and NAD+ metabolism as well as DNA damage signaling (large solid line box). NAD+ metabolism supports metabolic changes and signaling that leads to activation of NFκB signaling and high proinflammatory SASP expression. A low-proinflammatory SASP that accompanies replicative senescence is driven primarily through DNA damage-mediated p38MAPK activation, but devoid of HMGAs-mediated NAMPT expression (dash line box). Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Results

HMGAs regulate NAMPT expression.

To identify HMGA1 target genes during senescence, we performed HMGA1 chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by next generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis in proliferating and oncogenic-RAS induced senescent IMR90 cells. Through cross-referencing HMGA1 ChIP-seq with RNA-seq datasets comparing proliferating vs. oncogenic-RAS induced senescent IMR90 cells, we identified NAMPT as a top HMGA1 target gene whose expression increased in senescent cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The differential HMGA1 peak in OIS cells is ~500 bp upstream of the transcription starting site (Supplementary Fig. 1b), indicating that the HMGA1 binding site may function as an enhancer in regulating NAMPT expression. Indeed, we validated that the association of HMGA1 with the site was significantly enhanced during OIS (Fig. 1a). This also correlated with an increase in the epigenetic enhancer markers such as H3K4Me1 and H3K27Ac (Fig. 1a). In addition, we validated that NAMPT expression was upregulated during OIS (Fig. 1b-c). Knockdown of HMGA1 suppressed NAMPT upregulation during OIS (Fig. 1b-c). Similar observations were also made with HMGA2 knockdown (Fig. 1d-e). Conversely, ectopic HMGA1 upregulated NAMPT expression (Fig. 1f). Consistent with previous reports 11, ectopic HMGA1 promoted senescence as evidenced by markers such as SA-β-gal, cell growth arrest, decrease in Cyclin A and upregulation of p16 (Fig. 1g-i). Notably, these senescence markers were not affected by NAMPT knockdown in established senescent cells induced by ectopic HMGA1 (Fig. 1f-i and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Together, we conclude that HMGAs upregulate NAMPT during OIS through an enhancer element.

NAMPT promotes the proinflammatory SASP.

We next sought to examine the potential role of HMGA1-regulated NAMPT during senescence. Consistent with previous reports 11, knockdown of HMGA1 at the time of senescence initiation suppressed senescence induced by oncogenic RAS (Supplementary Fig. 2a-d). Similarly, inhibition of NAMPT by knockdown or a small molecule inhibitor FK866 19 suppressed RAS-induced senescence at the time of initiation (Supplementary Fig. 2a-d). Notably, NAMPT upregulation coincided with the upregulation of genes in the second, proinflammatory, SASP wave such as IL1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (Fig. 2a-c), but not with the upregulation of genes in the first, immuosuppressive, wave of SASP such as TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Indeed, knockdown of HMGA1 or inhibition of NAMPT by either knockdown or FK866 at the time of senescence initiation suppressed the proinflammatory SASP (Supplementary Fig. 2f). To limit the possibility that the observed suppression of SASP is an indirect effect of suppression of senescence and its associated growth arrest by inhibition of HMGA1/NAMPT, we established that knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT, or inhibition of NAMPT activity by FK866, did not affect the growth and expression of markers of senescence in the established OIS cells (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2g-i). However, proinflammatory SASP gene expression was significantly inhibited by knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT or FK866 in the established OIS cells (Fig. 2e-f). This finding was confirmed by using SASP proteins antibody arrays (Fig. 2g). Consistently, although NAMPT knockdown cannot overcome established senescence induced by ectopic HMGA1 (Fig. 1f-i), NAMPT knockdown suppressed the SASP induced by HMGA1 (Fig. 2h). Further supporting the notion that the observed effects on SASP are mediated by NAMPT downstream of HMGA1, ectopic NAMPT rescued the suppression of SASP induced by HMGA1 knockdown during OIS (Fig. 2i-j). Similar findings were also obtained during senescence induced by oncogenic BRAF or chemotherapeutics such as etoposide (Supplementary Fig. 2j-q). In addition to its cell intrinsic enzymatic activity during NAD+ biogenesis, NAMPT is also a secreted factor 13. Indeed, knockdown of either HMGA1 or NAMPT decreased the levels of extracellular secreted NAMPT (Supplementary Fig. 2r). However, secreted extracellular NAMPT unlikely contribute to NAD biosynthesis in this setting because of the lack of its substrate, phosphoribosylpyrophosphate, in tissue culture media 20. Thus, to determine whether the observed effects are due to its cell intrinsic enzymatic activity, we determined whether the observed rescue by ectopic NAMPT in HMGA1 knockdown OIS cells depends on its enzymatic activity. Indeed, in contrast to wildtype NAMPT, a mutant NAMPT that is deficient in enzymatic activity failed to rescue the SASP phenotype (Fig. 2i-j). Consistently, similar findings were made through inhibition of NAMPT activity by FK866 or NAMPT knockdown (e.g., Fig. 2f-h). Thus, we conclude that HMGA1/NAMPT promote the proinflammatory SASP and this depends on NAMPT’s enzymatic activity.

NAD+ metabolism drives proinflammatory SASP.

Since NAMPT’s enzymatic activity is required for SASP, we profiled the changes in steady-state metabolites induced by inhibition of HMGA1/NAMPT by LC-MS/MS. Consistent with NAMPT’s role in NAD+ metabolism 13, the most dramatic changes were observed in levels of NMN, the direct NAMPT metabolite 14, 15, after knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT or treatment with FK866 (Fig. 3a). This was validated by measuring NMN levels in these cells (Fig. 3b). Consistently, NAD+/NADH ratio and NAD+ levels were significantly increased in OIS cells, which was decreased by knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT or treatment with FK866 (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3a-b). Similar observations were also made in senescence induced by oncogenic BRAF or etoposide (Supplementary Fig. 3c-d). Notably, mitochondria dysfunction-associated senescence (MiDAS) secretory phenotype is linked to a lower NAD+/NADH ratio 16. However, OIS with inactivated HMGA1/NAMPT is different from MiDAS secretory phenotype because MiDAS secretory factors such as IL10 and TNFα were also suppressed by HMGA1/NAMPT inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 3e). In addition, temporal analysis revealed that an increase in NAD+/NADH ratio coincided with upregulation of NAMPT and proinflammatory SASP (Fig. 2a-c and 3d). Further, ectopic HMGA1 that increased NAMPT expression was sufficient to increase NAD+/NADH ratio and NAD+ levels, which was suppressed by NAMPT knockdown (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 3f). This suggests that HMGA1 increases NAD+/NADH ratio through upregulating NAMPT during senescence. Indeed, ectopic wildtype NAMPT but not an enzymatic activity deficient mutant rescued the decrease in NAD+/NADH ratio induced by HMGA1 knockdown (Fig. 3f). Likewise, addition of exogenous NMN was sufficient to restore NAD+/NADH ratio (Fig. 3g), which correlated with a restoration of the decrease in the proinflammatory SASP induced by knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT or FK866 (Fig. 3h). Thus, we conclude that NAMPT functions downstream of HMGA1 to promote the proinflammatory SASP through increasing NAD+/NADH ratio.

We next performed stable isotope tracer analysis using [13C6]-glucose. Knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT or FK866 significantly decreased intracellular pyruvate and lactate (Fig. 3i-k), suggesting an overall decrease in glycolysis, which correlated with a decrease in glucose uptake and extracellular acidification (Fig. 3l-m and Supplementary Fig. 3g). In addition, mitochondria respiration was suppressed in these cells as evidenced by a decrease in oxygen consumption (Fig. 3n and Supplementary Fig. 3h).

NAD+ metabolism promotes cancer progression.

We next determined the effects of NAD+ metabolism-regulated proinflammatory SASP in vitro using a co-culture of the OIS IMR90 cells with TOV21G ovarian cancer cells. Compared with controls, OIS IMR90 cells stimulated the growth of the co-cultured TOV21G cancer cells (Fig. 4a). Notably, knockdown of HMGA1 or NAMPT or treatment with NAMPT inhibitor FK866 in the established OIS cells significantly suppressed the growth stimulation (Fig. 4a). We next determined the effects of NAD+ metabolism-regulating the proinflammatory SASP in vivo. To do so, we utilized a pancreatic cancer mouse model in which the proinflammatory SASP promotes tumor progression in a paracrine SASP-dependent and intrinsic senescence-associated growth arrest-independent manner 21. Specifically, mice expressing Cre recombinase-inducible Lox-STOP-Lox-K-RasG12D were crossed with mice expressing Cre under the control of the pancreas-specific p48 promoter (hereafter referred to as KC mice). These mice develop pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanINs), precursors to malignancy, which contain senescent cells 22. At 8 week of age, KC mice were given intraperitoneal injections of either vehicle control, 500 mg/kg NMN daily, or treated with 25 mg/kg FK866 daily for 13 days. Mice were sacrificed the day after the last injection and pancreata were harvested for analysis. Notably, NMN treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the proportion of normal acinar area in pancreata compared to controls, indicative of an increase in the amount of precancerous and cancerous lesions (Fig. 4b-c). Indeed, there was a significant increase in the amount of desmoplastic tissue in NMN-treated pancreata compared to controls, as indicated by Masson trichrome staining (Fig. 4d-e). This correlated with an increase in IL1β, IL-6, and IL-8 expression and an increase in immune cell infiltration (such as CD3- and F4/80-positive cells) in NMN-treated pancreata (Fig. 4f-j). Notably, NAMPT expression positively correlates with expression of a number of SASP genes in human PanINs (Supplementary Fig. 4). Consistent with the findings that NAMPT inhibition suppresses senescence at the time of initiation (Supplementary Fig. 2a-d), FK866 suppressed the expression of IL1β, IL-6, and IL-8 and senescence markers such as SA-β-gal, p16 and p21 (Fig. 4f and 4k-n). Indeed, FK866 did not decrease acinar area, Masson trichrome staining or immune cell infiltration compared with KC controls (Fig. 4b-j), suggesting tumor progression that is associated with overcoming senescence. In addition, the expression of the senescence markers such as SA-β-gal, p16 and p21 was not decreased by NMN treatment (Fig. 4k-n). Notably, nicotinamide (NAM), a substrate of NAMPT, stimulated TOV21G tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model and inducible NAMPT knockdown suppressed the observed growth stimulation (Fig. 4o-p). This suggests that the observed effects are due to growth of cancer cells. Taken together, these data support the notion that NMN treatment enhances the inflammatory environment in the pancreas to accelerate pancreatic cancer progression.

AMPK signaling mediates the proinflammatory SASP induced by NAD+.

Consistent with the notion that a decrease in NAD+/NADH ratio suppresses energy production 23, the ADP/ATP ratio was significantly increased by knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT, which was suppressed by exogenous NMN supplementation (Fig. 5a). An increase in ADP/ATP ratio activates AMPK kinase 24. Knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT increased phosphorylated-AMPK expression, which was rescued by NMN supplement (Fig. 5b-c). Consistently, inhibition of AMPK activity by compound C 25 partially rescued the decrease in SASP induced by HMGA1/NAMPT knockdown or FK866 (Fig. 5d-f). In addition, serine 15 residue of p53 is a target of AMPK 26 and p53 is known to play a role in suppressing SASP 27. Indeed, knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT increased p53 phosphorylation, while NMN supplement suppressed the observed increase in p53 phosphorylation (Fig. 5b-c). Inhibition of activity of nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT) that converts NMN into NAD+ downstream of NAMPT by Gallotannin (5 μM) also suppressed SASP (Supplementary Fig. 5a-b) 28. p53 restrains SASP through p38MAPK activation 29. Consistently, p38MAPK activation was suppressed by knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT, which was rescued by exogenous NMN (Fig. 5b-c). Finally, p38MAPK increases NFκb activity that plays a key role in promoting SASP 29. Indeed, activation of p65, the regulatory subunit of NFκb, was suppressed by knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT, which was rescued by NMN supplementation (Fig. 5b-c). This correlated with the observed changes in NFκb activity in these cells (Fig. 5g). Although CEBPβ plays a key role in driving the proinflammatory SASP 6, its expression was not affected by knockdown of HMGA1/NAMPT or FK866 (Supplementary Fig. 5c-d). This suggests that HMGA1/NAMPT regulates proinflammatory SASP through NAD+/NADH ratio independent of CEBPβ expression.

NAD+ metabolism governs the strengths of the proinflammatory SASP.

Consistent with previous reports 30, 31, NAMPT was downregulated during replicative senescence (Fig. 6a-b) and NAMPT knockdown or inhibition by FK866 alone induced senescence (Supplementary Fig. 6a-c). This correlated with downregulation of HMGA1 and a decrease in the association of HMGA1 with the NAMPT enhancer element (Fig. 6a and 6c). Consistently, the NAD+/NADH ratio was decreased during replicative senescence (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Although the proinflammatory SASP genes are upregulated during replicative senescence, their expression was significantly higher in OIS (Supplementary Fig. 6e). Indeed, the growth stimulation of co-cultured TOV21G cancer cells by OIS was significantly stronger compared with replicative senescent cells (Fig. 6d). In addition, NMN enhanced SASP in RAS-induced OIS cells and the secretion of the SASP factors were validated by protein arrays (Fig. 6e-f). This correlated with an increase in NAD+/NADH ratio, NFκb promoter activity and an enhanced growth stimulation of co-cultured TOV21G cancer cells (Fig. 6g-i). Similar SASP enhancement was also observed for NAM and nicotinic acid supplements (Supplementary Fig. 6f-g). Finally, ectopic expression of HMGA1 or NAMPT or NMN supplement enhanced etoposide induced SASP in TOV21G ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 6j). This suggests that NAD+ metabolism downstream of HMGA1/NAMPT may determine the strengths of the proinflammatory SASP. Consistently, senescence induced by inhibition of NAMPT activity by knockdown or FK866 was not associated with the strong proinflammatory SASP (Supplementary Fig. 6h-i). Indeed, compared with OIS, AMPK, p53 and DNA damage marker γH2AX was activated at a higher level, while p38MAPK and p65 was activated at a lower level, in replicative senescent cells (Fig. 6a). This suggests that NAD+/NADH regulated AMPK signaling downstream of HMGA1/NAMPT, which governs the strengths of the proinflammatory SASP. Consistent with previous reports, although DNA damage was induced during OIS, it was restrained during late stage of OIS 32, 33 (Supplementary Fig. 6j). Supporting the notion that glycolysis and mitochondria respiration promote NAD+ dependent SASP, compared with OIS, both extracellular acidification (ECAR) and oxygen consumption (OCR) were significantly lower in RS cells (Supplementary Fig. 6k-l).

We next determined whether oncogenic RAS is sufficient to increase NAD+ biogenesis through HMGA1 regulated NAMPT in replicative senescent cells. Indeed, RAS increased HMGA1 and NAMPT levels in replicative senescent cells, which correlated with a decrease in AMPK, an increase in p38 and p65 activation, and an increase in NFκb reporter activity (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Notably, NAD+/NADH ratio was increased in these cells (Fig. 7b), which correlated with a significant increase in SASP (Fig. 7c). Since ectopically expressed NAMPT has both cell intrinsic and extracellular activity 13, we performed the NMN supplementation experiment instead of NAMPT ectopic expression to limit the extracellular NAMPT ligand activity. Indeed, exogenous NMN supplement in replicative senescent cells suppressed AMPK and p38 activity, while increased p38 and p65 activation, and NFκb promoter activity (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Fig. 7b). This correlated with an increase in NAD+/NADH ratio and an enhancement of the proinflammatory SASP and stimulation of the growth of co-cultured TOV21G ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 7e-g). Notably, RAS or NMN supplement did not affect senescence and the associated cell growth arrest (Supplementary Fig. 7c-e). Thus, these data support a model whereby an increase in NAD+/NADH ratio converts low proinflammatory SASP during replicative senescent into high proinflammatory SASP (Fig. 6h).

Discussion

HMGA1 promotes senescence-associated growth arrest 11. Here we show that HMGA1 plays an instrumental role in the proinflammatory SASP by upregulating NAMPT through an enhancer element. Thus, HMGA1 couples the senescence-associated cell growth arrest and the proinflammatory SASP during senescence. Interestingly, HMGA1 is often upregulated in human cancers and its overexpression correlates with a poor prognosis in many cancer types 8, 34. However, the tumor suppressive effects of HMGA proteins depend on the integrity of the senescence machinery and HMGA proteins become oncogenic in senescence-bypassed cells 11. Thus, HMGA1 is no longer tumor suppressive in senescence-bypassed cancer cells. Our data show that inhibition of HMGA1 suppresses the SASP. This raises the possibilities that targeting HMGA1-regulated NAMPT may be an effective approach to suppress a proinflammatory tumor microenvironment in HMGA1-overexpressing tumors. Indeed, NAMPT inhibitors are already in clinical trials. Thus, senescence-inducing cancer therapeutics including chemotherapy may benefit from a combination with NAMPT inhibitors.

Our results show that NAD+ metabolism plays a key role in determining the strength of the proinflammatory SASP. High SASP-associated senescence such as OIS is predominantly driven by a high NAD+/NADH ratio, while low SASP-associated senescence such as RS is primarily driven by DNA damage. This is consistent with the reported role of DNA damage in SASP 35. These differences in upstream signaling determined the strength of p38MAPK and NFκb signaling to ultimately dictate the strength of the SASP during different types of senescence. Indeed, increasing the NAD+/NADH ratio in RS by ectopic oncogenic RAS or NMN supplementation significantly enhances the proinflammatory SASP. Notably, the proinflammatory SASP is tumorigenic 36, 37. Consistently, NMN supplementation promotes PDAC progression in a mouse model driven by oncogenic Kras. Thus, NAD+ augmenting dietary supplements may be tumorigenic in vivo in stressed conditions such as premalignant senescent lesions induced by activated oncogenes. However, it has been extensively documented that NMN supplements can alleviate certain age-related pathophysiological conditions and NAD+ augmenting supplements such as NMN is currently in clinical development as nutraceuticals 12. Thus, dietary NAD+ augmenting supplement should be administered with precision to balance the advantageous anti-ageing effects with potential detrimental pro-tumorigenic side effects. In summary, our results show that NAD+ metabolism governs the proinflammatory SASP. Thus, our study will have far-reaching implications for understanding proinflammatory SASP regulation during senescence and precisely administering NAD+ augmenting anti-ageing dietary supplements such as NMN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank the Wistar Institute Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility for technical assistance. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants (R01CA160331, R01CA163377 and R01CA202919 to R. Z., P01AG031862 to R.Z., K.N. and D.S., P50CA228991 to R.Z., R01CA148639 and R21CA155736 to G.D., F31CA206387 to L.L., R00CA194309 to K.M.A., R01DK098656 to J.A.B., R01CA131582 to D.W.S., R50CA211199 to A.V.K., R50CA221838 to H.-Y.T. and T32CA009191 to T.N.), US Department of Defense (OC140632P1 and OC150446 to R.Z.), The Honorable Tina Brozman Foundation for Ovarian Cancer Research (to R.Z.) and Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance (Collaborative Research Development Grant to R.Z. and D.W.S., and Ann and Sol Schreiber Mentored Investigator Award to S.W.). Support of Core Facilities was provided by Cancer Centre Support Grant (CCSG) CA010815 to The Wistar Institute.

Footnotes

Financial and non-Financial Competing Interests

The authors have no financial and non-financial competing interests.

References

- 1.Hayflick L & Moorhead PS The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res 25, 585–621 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campisi J Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol 75, 685–705 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X et al. SMARCB1-mediated SWI/SNF complex function is essential for enhancer regulation. Nat Genet 49, 289–295 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Childs BG et al. Senescent cells: an emerging target for diseases of ageing. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16, 718–735 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sieben CJ, Sturmlechner I, van de Sluis B & van Deursen JM Two-Step Senescence-Focused Cancer Therapies. Trends Cell Biol 28, 723–737 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoare M et al. NOTCH1 mediates a switch between two distinct secretomes during senescence. Nat Cell Biol 18, 979–992 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito Y, Hoare M & Narita M Spatial and Temporal Control of Senescence. Trends Cell Biol 27, 820–832 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sumter TF et al. The High Mobility Group A1 (HMGA1) Transcriptome in Cancer and Development. Curr Mol Med 16, 353–393 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi ME & Agresti A HMG proteins: dynamic players in gene regulation and differentiation. Current opinion in genetics & development 15, 496–506 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas JO HMG1 and 2: architectural DNA-binding proteins. Biochemical Society transactions 29, 395–401 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narita M et al. A novel role for high-mobility group a proteins in cellular senescence and heterochromatin formation. Cell 126, 503–514 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdin E NAD(+) in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science 350, 1208–1213 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garten A et al. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of NAMPT and NAD metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11, 535–546 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin PR, Shea RJ & Mulks MH Identification of a plasmid-encoded gene from Haemophilus ducreyi which confers NAD independence. J Bacteriol 183, 1168–1174 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rongvaux A et al. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor, whose expression is up-regulated in activated lymphocytes, is a nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, a cytosolic enzyme involved in NAD biosynthesis. Eur J Immunol 32, 3225–3234 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiley CD et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induces Senescence with a Distinct Secretory Phenotype. Cell Metab 23, 303–314 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H et al. NAD(+) repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice. Science 352, 1436–1443 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills KF et al. Long-Term Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Mitigates Age-Associated Physiological Decline in Mice. Cell Metab 24, 795–806 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasmann M & Schemainda I FK866, a highly specific noncompetitive inhibitor of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, represents a novel mechanism for induction of tumor cell apoptosis. Cancer Res 63, 7436–7442 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hara N, Yamada K, Shibata T, Osago H & Tsuchiya M Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase/visfatin does not catalyze nicotinamide mononucleotide formation in blood plasma. PLoS One 6, e22781 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rielland M et al. Senescence-associated SIN3B promotes inflammation and pancreatic cancer progression. J Clin Invest 124, 2125–2135 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerra C et al. Pancreatitis-induced inflammation contributes to pancreatic cancer by inhibiting oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell 19, 728–739 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehninger AL, Nelson DL & Cox MM Lehninger principles of biochemistry, Edn. 6th. (W.H. Freeman, New York; 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardie DG, Ross FA & Hawley SA AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 251–262 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou G et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest 108, 1167–1174 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones RG et al. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell 18, 283–293 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coppe JP et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol 6, 2853–2868 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger F, Lau C, Dahlmann M & Ziegler M Subcellular compartmentation and differential catalytic properties of the three human nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase isoforms. J Biol Chem 280, 36334–36341 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freund A, Patil CK & Campisi J p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J 30, 1536–1548 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Veer E et al. Extension of human cell lifespan by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 282, 10841–10845 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim CS, Potts M & Helm RF Nicotinamide extends the replicative life span of primary human cells. Mech Ageing Dev 127, 511–514 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Micco R et al. Interplay between oncogene-induced DNA damage response and heterochromatin in senescence and cancer. Nat Cell Biol 13, 292–302 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Micco R et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature 444, 638–642 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah SN & Resar LM High mobility group A1 and cancer: potential biomarker and therapeutic target. Histol Histopathol 27, 567–579 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodier F et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol 11, 973–979 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davalos AR, Coppe JP, Campisi J & Desprez PY Senescent cells as a source of inflammatory factors for tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev 29, 273–283 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshimoto S et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 499, 97–101 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang R et al. Formation of MacroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev Cell 8, 19–30 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu P et al. Regulation of inflammatory cytokine expression in pulmonary epithelial cells by pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor via a nonenzymatic and AP-1-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 284, 27344–27351 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M & Salzberg SL Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10, R25 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinz S et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 38, 576–589 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tasdemir N et al. BRD4 Connects Enhancer Remodeling to Senescence Immune Surveillance. Cancer Discov 6, 612–629 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dobin A et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li B & Dewey CN RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Love MI, Huber W & Anders S Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dimri GP et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92, 9363–9367 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crnogorac-Jurcevic T et al. Molecular analysis of precursor lesions in familial pancreatic cancer. PLoS One 8, e54830 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

ChIP-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number: GSE111841. Raw RNA-seq data for RAS-induced senescence and control conditions in IMR90 cells was downloaded from GEO (under accession code: GSE74324) 41. For correlation between NAMPT and SASP genes in human laser capture and microdissected PanIN lesion samples, gene expression data was obtained from GEO (under accession code: GSE43288) 1.

Source data used for statistical analyses of Figures 1a-b, 1e, 1h-i, 2b-c, 2e-f, 2h, 2j, 3a-n, 4a, 4c, 4e-f, 4h, 4j, 4l-m, 4p, 5a, 5d-g, 6b-e, 6g-i, 7b-c, 7e-f, 7g, and Supplementary Figs 2c-f, 2h-j, 2l-n, 2p-q, 3a-f, 3h, 4, 5a-d, 6b-g, 6i, 6k-l, 7a-b and 7d-e are provided as Supplementary Table 1 (Statistics source data). All other data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request.

Figure 1. HMGA proteins regulate NAMPT expression.

a, ChIP analysis for the enhancer of NAMPT gene identified by HMGA1 ChIP-seq using the indicated antibodies or an isotype matched IgG control during OIS (n = 3 independent experiments). b,c, HMGA1 in fully established senescent cells was knocked down using two independent short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs). Expression of NAMPT mRNA was determined by qRT-PCR (b) (n = 3 independent experiments), or the indicated proteins were determined by immunoblot (c). d, In established senescent cells, HMGA2 was knocked down using two independent shRNAs and expression of the indicated proteins was determined by immunoblot. e, ChIP analysis for the enhancer of NAMPT gene identified by HMGA1 ChIP-seq using an anti-HMGA2 antibody or an isotype matched IgG control during OIS (n = 3 independent experiments). f,g, Cells with or without ectopic V5-tagged HMGA1 expression with or without NAMPT knockdown were examined for the expression of the indicated proteins by immunoblot (f), or subjected to SA-β-gal staining or colony formation (g), scale bar = 100 μm. The percentage of SA-β-gal positive cells (h) and the integrated intensity of the colonies formed by the indicated cells (i) were quantified using NIH Image J software (n = 3 independent experiments). All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Figure 2. HMGA1-mediated NAMPT expression drives the proinflammatory SASP.

a-c, The expression of indicated proteins in cells induced to senesce by oncogenic RAS at the indicated time points was analyzed by immunoblot (a). Expression of NAMPT (b) and the indicated proinflammatory SASP genes (c) were determined by qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). d-g, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down using the indicated shRNAs. The NAMPT activity was also inhibited by FK866. The expression of the indicated proteins was determined by immunoblot (d). Expression of SASP genes was determined using quantitative RT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments) (e,f). g, The secretion of soluble factors under the indicated conditions were detected by antibody arrays. Heat map indicates fold change in comparison to the control or RAS condition. Relative expression level per replicate and average fold change differences are shown (n = 4 independent experiments). h, V5-HMGA1 overexpressing cells had NAMPT knocked down and expression of NAMPT and the indicated SASP genes were determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). i-j, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 was knocked down with or without ectopic expression of a FLAG-tagged wild type or catalytically-inactive NAMPT. The expression of the indicated proteins was determined by immunoblot (i). Expression of the indicated SASP genes was determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments) (j). All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Figure 3. NAD+ metabolism drives proinflammatory SASP.

a-c, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down using the indicated short hairpin RNAs. The NAMPT activity was also inhibited by FK866. Steady-state metabolite levels were measured by LC-MS/MS. Heat map indicates fold change in comparison to the control condition (a) (n=6 independent experiments). NMN (b) (n=6 independent experiments) and NAD+/NADH ratio (c) were determined in the indicated cells. d, Cells were induced to senesce by oncogenic RAS and analyzed for the NAD+/NADH ratio at the indicated time points. e, Cells with or without ectopic V5-tagged HMGA1 expression with or without NAMPT knockdown were examined for the NAD+/NADH ratio. f, The NAD+/NADH ratio was determined in established senescent cells with or without HMGA1 knockdown with or without ectopic expression of a FLAG-tagged wild type or catalytically-inactive NAMPT. g,h, In established senescence, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down using the indicated shRNAs. The NAMPT activity was also inhibited by FK866. Under these conditions, cells were treated with NMN and the NAD+/NADH ratio (g) and expression of the indicated SASP genes (h) were determined by qRT-PCR. i-k, Cells from the conditions as in (a) were incubated for 6 hours in the presence of 13C6-glucose and intracellular metabolites were extracted for analysis by LC-MS to evaluate glycolytic flux in the form of pyruvate (i) and lactate (j) and mitochondrial respiration rates as indicated by citrate production (k). Data were normalized based on protein concentration. l, Cells from conditions as in (a) were incubated with a fluorescent glucose analog (2-NBDG) and analyzed by flow cytometry for glucose uptake. m,n, Cells from the conditions in (g) were analyzed using Seahorse Bioanalyzer XFe96 for extracellular acidification (ECAR) (m) and oxygen consumption (OCR) (n). Data were normalized based on protein concentration. n = 3 independent experiments unless otherwise stated. All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 4. NMN enhances the inflammatory environment and cancer progression in vivo.

a, In established senescent cells, HMGA1 or NAMPT were knocked down or cells were treated with FK866 to assess the effect on the growth of co-cultured luciferase-expressing TOV21G ovarian cancer cells. Cell growth was assessed by luminescence following eight days of growth. (n=3 independent experiments). b-n, Wildtype mice were compared to KC mice treated with vehicle, NMN (500 mg/kg daily), or FK866 (25 mg/kg daily). Representative H&E images of pancreas (b) and quantification of percent acinar area (c). Representative Masson trichrome staining images of pancreas (d) and quantification of percent trichrome area (e). Expression of IL1β, IL-6 and IL-8 was determined using qRT-PCR analysis (f). Representative immunohistochemical staining of infiltrating F4/80-positive immune cells (g) and quantification of percent F4/80 positive cells (h). Representative immunohistochemical staining of infiltrating CD3-positive immune cells (i) and quantification of the number of CD3 positive cells/field (j). Representative SA-β-gal staining (k) and quantification of SA-β-gal positive areas (l) in the indicated treatment groups. Expression of p16 (m) and p21 (n) was determined using qRT-PCR analysis. n=10 mice/group unless otherwise stated. Scale bar for all images is 200 μm. o, Immunoblot of the indicated protein in TOV21G cells containing doxycycline-inducible knockdown of NAMPT with or without doxycycline treatment. p, TOV21G and oncogene-induced senescent IMR90 cells were subcutaneously co-injected into the right dorsal flank of 6-8 week old NSG female mice. The mice (n=9 mice/group) were treated with vehicle control, NAM (500 mg/kg; intraperitoneal injection; every other days) for 17 days. Tumor growth in the indicated treatment groups was measured at the indicated time points. All graphs represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical source data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Unprocessed original scans of all blots with size marker are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Figure 5. AMPK signaling mediates proinflammatory SASP induced by NAD+ metabolism.