ABSTRACT

Bacteria of the genus Brucella colonize a wide variety of mammalian hosts, in which their infectious cycle and ability to cause disease predominantly rely on an intracellular lifestyle within phagocytes. Upon entry into host cells, Brucella organisms undergo a complex, multistage intracellular cycle in which they sequentially traffic through, and exploit functions of, the endocytic, secretory, and autophagic compartments via type IV secretion system (T4SS)-mediated delivery of bacterial effectors. These effectors modulate an array of host functions and machineries to first promote conversion of the initial endosome-like Brucella-containing vacuole (eBCV) into a replication-permissive organelle derived from the host endoplasmic reticulum (rBCV) and then to an autophagy-related vacuole (aBCV) that mediates bacterial egress. Here we detail and discuss our current knowledge of cellular and molecular events of the Brucella intracellular cycle. We discuss the importance of the endosomal stage in determining T4SS competency, the roles of autophagy in rBCV biogenesis and aBCV formation, and T4SS-driven mechanisms of modulation of host secretory traffic in rBCV biogenesis and bacterial egress.

THE BRUCELLA INTRACELLULAR CYCLE

Brucella Pathogenesis

Bacteria of the genus Brucella belong to the alpha-2 subgroup of Alphaproteobacteria, a phylogenetic subgroup which includes a variety of bacteria that are either animal or plant pathogens or symbionts. As such, these bacteria have experienced a long-standing coevolution with eukaryotic hosts that has likely shaped their biology. The genus Brucella is composed of an increasing number of species that infect a wide variety of mammals as primary hosts, such as bovines (Brucella abortus), goats (B. melitensis), swine (B. suis), ovines (B. ovis), camels, elk, bison (B. abortus), canines (B. canis), rodents (B. neotomae and B. microti), and monkeys (B. papionis), as well as marine mammals such as seals, porpoises, dolphins, and whales (B. pinnipedialis and B. ceti) and also amphibians (B. inopinata) (1). Most species cause in their hosts a disease named brucellosis, which manifests as abortion, sterility, and lameness in animals and which can also be transmitted to humans via inhalation of aerosolized bacteria or via ingestion of, or contact with, contaminated tissues or derived products, classically by the most pathogenic species, B. melitensis, B. suis, and B. abortus, with additional cases due to B. canis and B. neotomae (2–4). Human brucellosis is characterized by nonspecific flu-like symptoms during an early acute phase, which is followed by a chronic infection with debilitating consequences, including recurrent fever, osteomyelitis, arthritis, neurological symptoms, and endocarditis, if not treated with antibiotic therapy in a timely manner (4). Animal and human brucellosis share common pathophysiological features at the cellular level, where bacteria undergo an intracellular cycle that ensures their survival, proliferation, and persistence within phagocytic cells of various tissues, including macrophages and dendritic cells (4, 5). Initially described in placental tissues of infected animals (6), the ability of B. abortus to extensively proliferate in mammalian cells was reproduced in a variety of tissue culture models of epithelial and phagocytic cells that have been instrumental in defining the main features of the bacterium’s intracellular cycle (7–12).

A Multistage Intracellular Cycle

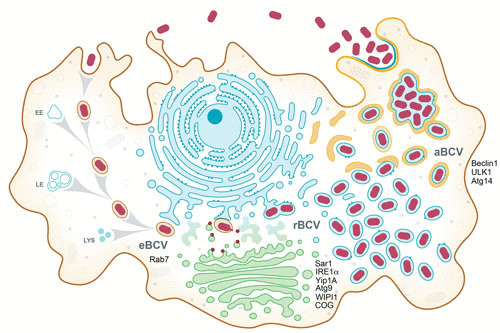

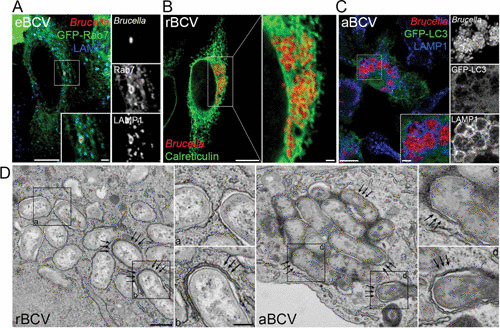

Upon entry into either phagocytic or nonphagocytic cells, Brucella bacteria are enclosed within a membrane-bound compartment that has been named the Brucella-containing vacuole (BCV) (8, 13) (Fig. 1), based on the concept that the original phagosome is functionally modified by the bacterium into an idiosyncratic membrane-bound vacuole. Early microscopy-based trafficking studies established that the initial BCV normally traffics along the endocytic pathway, sequentially acquiring early and then late endosomal membrane markers (7, 8), and becomes acidified, reaching a pH of 4.5 (14–16), consistent with a complete phagosomal maturation process. Based on the endosomal nature of the bacterial vacuole at this stage of the intracellular cycle (between 0 and 8 h postinfection), it was named the endosomal BCV (eBCV) (Fig. 1 and 2A) (17).

FIGURE 1.

Model of the Brucella intracellular cycle in macrophages. Following phagocytic uptake by macrophages, Brucella spp. reside during the first 8 to 12 h postinfection within a membrane-bound vacuole that undergoes endosomal maturation via sequential interactions with early (EE) and late (LE) endosomes and lysosomes (LYS) to become an acidified eBCV. The host small GTPase Rab7 contributes to eBCV maturation, which provides physicochemical cues promoting expression of the VirB T4SS, which translocates effector proteins (red) that mediate eBCV interactions with the ER exit site and acquisition of ER and Golgi apparatus-derived membranes. These events lead to the biogenesis of replication permissive, ER-derived BCVs, called rBCVs. The host proteins Sar1, IRE1α, Yip1A, Atg9, and WIPI1 and the COG complex contribute to rBCV biogenesis. Bacteria then undergo extensive replication in rBCVs between 12 and 48 h postinfection, after which rBCVs are captured within autophagosome-like structures in a VirB T4SS-dependent manner to become aBCVs. aBCV formation requires the host autophagy proteins beclin1, ULK1, and Atg14. aBCVs harbor features of autolysosomes and are required for bacterial egress and new cycles of intracellular infections.

FIGURE 2.

Structure and membrane composition of BCVs during the Brucella intracellular cycle. (A) Confocal fluorescence micrograph of HeLa cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Rab7 and infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus strain 2308 for 6 h. The inset shows an eBCV with the typical accumulation of the late endosomal/lysosomal markers Rab7 and LAMP1. Bars, 10 and 2 μm. (B) Confocal fluorescence micrograph of a HeLa cell infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus strain 2308 for 24 h and stained for the ER marker calreticulin. The inset shows a cluster of calreticulin-positive rBCVs containing replicating bacteria and associated with the ER network. Bars, 10 and 1 μm. (C) Confocal fluorescence micrograph of a primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophage expressing the autophagy marker GFP-LC3 and infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus strain 2308 for 72 h. The inset shows a group of aBCVs with the typical accumulation of the late endosomal/lysosomal LAMP1 but not LC3. Bars, 10 and 2 μm. (D) Transmission electron micrographs of bone marrow-derived macrophages infected with B. abortus strain 2308 for 72 h and showing the ultrastructures of rBCVs (left, single-membrane-bound vacuoles [inset a]), of forming aBCVs (inset b and arrows), and of completed double-membrane-bound aBCVs (right [insets c and d and arrows]). Bars, 500 and 200 nm. Reprinted from reference 17 with permission.

Subsequent to eBCV interactions with the endocytic compartment, the vacuole progressively loses endosomal markers (between 8 and 12 h postinfection), concomitant with sustained interactions with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) structures, and eventually acquires ER membrane-associated markers such as calreticulin, calnexin, and Sec61β (7, 8, 13), indicating a turnover of eBCV membranes and accretion of ER-derived membranes. These vacuoles also gain structural and functional features of the ER (7, 8), further indicating a conversion of the eBCV into an ER-derived organelle. These structural and functional changes correlate with the onset of bacterial replication, suggesting that these organelles provide intracellular conditions that promote bacterial growth and replication. Based on these considerations, these vacuoles were named replicative BCVs (rBCVs) (Fig. 1 and 2B) (17). Original ultrastructural characterizations of rBCVs suggested that these vacuoles were individual and rarely connected with ER cisternae in either macrophage or HeLa cells (7, 8) (Fig. 2D), while other studies observed bacteria within the ER lumen of trophoblasts (6), leaving the actual organization of rBCVs uncertain. Recent electron tomography three-dimensional reconstruction of rBCVs clearly determined that these vacuoles are intricately connected with the ER and also seem to interact with vesicular traffic between the ER and the Golgi apparatus (18), demonstrating intimate interactions with the host secretory pathway. The rBCV stage is tightly associated with bacterial proliferation (between 12 and 48 h postinfection) and causes a dramatic reorganization of the host cell ER into the rBCV network (8).

Following extensive bacterial replication, an additional stage in the Brucella intracellular cycle consists of the progressive capture of rBCVs by crescent-like membrane structures, leading to the formation of multimembrane vacuoles that are structurally reminiscent of autophagosomes that contain small to large groups of bacteria and acquire late endosomal/lysosomal features (17). These remodeled rBCVs, which are called autophagic BCVs (aBCVs) (Fig. 1 and 2C and D) form between 48 and 72 h postinfection and are associated with bacterial release from infected cells and new infection events, indicating that they facilitate completion of the Brucella intracellular cycle (17).

By their functional and spatial diversity, the sequential eBCV, rBCV, and aBCV stages of the Brucella intracellular cycle point towards their necessity to the bacterium’s infectious cycle. Hence, significant efforts have been made in the last 2 decades to understand the underlying mechanisms that define these stages and how the bacterium exploits the corresponding cellular pathways to complete its intracellular cycle.

The VirB Type IV Secretion System

A hallmark of Brucella virulence is the expression of a VirB family type IVA secretion system (T4SS), which was identified by homology to the VirB T4SS of the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens and shown to be required for virulence in a murine model of chronic brucellosis and intracellular replication of B. abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis in various host cell models (19–21). Indeed, deletions of various genes within the virB operon, or transposon insertions in different virB genes, rendered Brucella unable to convert eBCVs into rBCVs and replicate intracellularly (8, 13, 22) and unable to establish a chronic infection in mice (23, 24), emphasizing major roles of this T4SS in rBCV biogenesis and Brucella intracellular replication. Based on the ability of various T4SSs to deliver effector proteins or nucleoprotein complexes across biological membranes, and by analogy to those that contribute to bacterial virulence (25, 26), the VirB T4SS of Brucella was presumed to deliver effector proteins into host cells across the eBCV membrane to modulate specific cellular functions and mediate rBCV biogenesis. This assumption was confirmed by the discoveries of an array of Brucella effector proteins translocated into host cells in a T4SS-dependent manner (27–32), which opened avenues to understand at the molecular level the underlying mechanisms of the Brucella intracellular cycle.

THE eBCV

Early BCV Maturation

Upon uptake by phagocytes or entry into nonphagocytic cells, Brucella bacteria initially reside in a phagosome that rapidly acquires markers of the early endocytic compartment, including the small GTPase Rab5, which controls early endosomal maturation, and the early endosomal antigen EEA-1 (8, 13, 33). Since these markers are acquired with kinetics similar to those of classical phagosomes, it is likely that the early BCV undergoes an unaltered maturation process. Consistently, the vacuole then acquires markers of late endosomes, such as the lysosome-associated membrane proteins LAMP1 (Fig. 2A) and LAMP2, CD63, and the small GTPase Rab7 (7, 8, 13, 16), which controls fusion with late endocytic compartments and lysosomes, further indicating a normal vacuolar maturation process within the first hours postinfection. Importantly, the BCV also rapidly becomes acidified to a pH in the range of 4.5 to 5.0 (14), further supporting a maturation process into phagolysosomes. However, early attempts at detecting delivery of lysosomal luminal contents to the BCV as evidence for fusion with lysosomes failed to demonstrate accumulation of cathepsin D by immunostaining (7, 13, 34). This led to the proposal that the BCV avoids fusion with terminal degradative lysosomes, despite advanced maturation events, thus preventing bacterial killing and ensuring intracellular survival.

The eBCV: A Necessary Evil?

Several studies monitoring bacterial viability within eBCVs have revealed that a large proportion of intracellular bacteria (up to 90% in primary bone marrow-derived macrophages) are killed (8, 16), arguing for bactericidal conditions within eBCVs. Using live-cell imaging of fluorescent fluid-phase markers that were chased to terminal lysosomes, as a method that precludes any issue with detection of soluble lysosomal antigens, Starr et al. showed that eBCVs in epithelial HeLa cells undergo fusion with terminal lysosomes, although to a restricted extent (16), directly demonstrating that the eBCV matures into a compartment resembling a phagolysosome. While these findings are consistent with the loss of bacterial viability in eBCVs observed in in vitro models, they may appear counterintuitive with regard to Brucella intracellular survival. This has led to the speculation that eBCVs that undergo full lysosomal maturation are not those permissive for bacterial survival and represent dead-end paths for the bacteria, while a small fraction of BCVs that do not mature along the endocytic pathway are those that generate rBCVs and allow proliferation of the surviving bacteria. However, the following observations are inconsistent with this possibility. First, LAMP1-positive eBCVs interact with ER cisternae and acquire ER markers, arguing that they undergo conversion into rBCVs (8). Second, eBCV acidification to a pH range of terminal lysosomes is necessary for rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication (14–16), as inhibition of lysosomal acidification prevents eBCV to rBCV conversion and bacterial replication (14–16). Third, inhibition of Rab7 activity, which controls fusion with lysosomes, also prevents eBCV conversion into rBCVs and bacterial replication (16), demonstrating that a functional late endocytic pathway and lysosomal fusion are required for Brucella to undergo its intracellular cycle. Fourth, eBCV acidification is essential for the induction of the virB operon (15, 16), which rapidly occurs postuptake in maturing eBCVs, peaking at 4 h postinfection (16, 35). Taken together, these findings rather support a model in which the eBCV stage is a necessary step in the Brucella intracellular cycle, which provides intravacuolar cues, including a lysosomal pH, that are necessary for the induction of the VirB T4SS and the resulting conversion of eBCVs to rBCVs.

In addition to its role in promoting Brucella T4SS competency, the eBCV may provide cues that initiate intracellular bacterial growth prior to completion of the replication-permissive rBCV. Deghelt et al. established using fluorescence microscopy methods that monitor chromosomal replication in intracellular Brucella that bacteria within LAMP1-positive eBCVs initiate chromosomal replication by 8 h postinfection, i.e., during the eBCV-to-rBCV conversion stage, while the infectious forms are in G1-arrested phase prior to 6 h postinfection (36). Whether this cell cycle change is triggered by the endosomal conditions of the eBCV or by intravacuolar alterations during conversion to rBCV remains to be determined. However, these findings indicate that Brucella extensively responds to its intravacuolar environment and initiates growth at the eBCV stage, further emphasizing the importance of the endosomal stage in the Brucella intracellular cycle.

THE rBCV

Role of the ER in rBCV Biogenesis

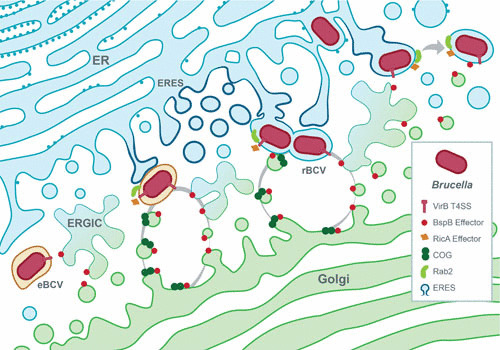

Biogenesis of the rBCV is a hallmark of the Brucella intracellular cycle, as it consists of the conversion of the original endosomal bacterial vacuole into a specialized organelle derived from the ER that promotes bacterial proliferation. The underlying mechanisms, host functions, and bacterial effectors that mediate this process have been the subject of extensive research. The nature of the rBCV was initially discovered via its ultrastructural characterization, showing fusion with ER cisternae and studding with ribosomes, and was further confirmed by the detection of ER-associated proteins on its membrane by immunofluorescence microscopy, intravacuolar detection of glucose-6 phosphatase activity, an ER luminal enzyme, and sensitivity to the ER-vacuolating toxin aerolysin (7, 8). The first clues about how a bacterial vacuole interacting with late endocytic and lysosomal compartments could convert into an ER-derived organelle came from the demonstration that ER exit sites (ERES), an ER subcompartment where secretory transport is initiated through the formation of COPII-coated cargo vesicles (37), are functionally important for rBCV biogenesis (22). eBCVs undergo T4SS-dependent, sustained interactions with COPII coat-positive ERES structures during the eBCV-to-rBCV conversion stage (Fig. 3), and inhibition of the small GTPase Sar1, which controls COPII coat assembly and ERES formation and function, inhibits rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication (22, 38). Consistent with these observations, Brucella infection upregulates production of Sar1 and the COPII components Sec23 and Sec24D by an unknown mechanism (39), suggesting that the bacterium upregulates Sar1- and COPII-mediated vesicular trafficking to promote rBCV biogenesis. Hence, Brucella may modulate ERES functions to promote rBCV biogenesis, by enhancing production of secretory vesicles that might fuse with the eBCV to initiate its conversion into a vacuole with ER fusogenic properties (Fig. 3), possibly creating a direct port of entry to the ER for the bacteria, while bypassing classical endosome-to-Golgi-to-ER retrograde trafficking processes.

FIGURE 3.

Model of VirB T4SS-dependent biogenesis of the rBCV. Bacteria in eBCVs induce expression of the VirB T4SS, which delivers effector proteins into the host cell. Among these, BspB traffics to Golgi membranes via the ER-to-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and binds to the COG complex to promote redirection of Golgi apparatus-derived vesicular traffic to BCVs. RicA binds the small host secretory GTPase Rab2, which contributes to its recruitment on maturing eBCVs and role in rBCV biogenesis. Additionally, eBCV interaction with ERES is accompanied by the upregulation of COPII coat components, induction of IRE1α, and Yip1A-dependent formation of ER-derived vesicles, which are also thought to contribute to rBCV biogenesis. T4SS-dependent acquisition of ER- and Golgi apparatus-derived secretory membranes by BCVs is thought to mediate eBCV-to-rBCV conversion.

Role of the UPR in the Brucella Intracellular Cycle

Another ER-mediated function associated with the Brucella intracellular cycle is the unfolded-protein response (UPR). Upon ER stress triggered by accumulation of misfolded proteins within the ER, signaling pathways controlled by the ER-localized UPR receptors IRE1α, PERK, and ATF6 are triggered and lead to a substantial reorganization of ER functions towards increased ER folding capacity, inhibition of protein synthesis, and activation of autophagy, all aimed at resolving ER stress (40). Although there have been disagreements about its extent, the consensus is that Brucella infection induces the UPR in macrophages or HeLa cells via at least the IRE1α pathway (39, 41, 42). Moreover, IRE1α is required for Brucella replication (43), and pharmacological compensation of protein misfolding using tauroursodeoxycholic acid impairs replication of B. melitensis (41), which supports the idea that the UPR is beneficial to the bacterium’s intracellular cycle. However, whether and how this stress response promotes rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication remain unclear. Taguchi et al. revealed a link between UPR induction, ERES, and rBCV biogenesis by showing that IRE1α is activated via the ERES-localized protein Yip1A, which controls formation of large vacuoles in a manner dependent on the autophagy-associated proteins Atg9 and WIPI1, and is also required for rBCV biogenesis (39). Hence, these findings support a model in which Brucella actively causes UPR induction via activation of the IRE1α pathway to promote an activation cascade leading to formation at ERES of vacuoles of a possible autophagic nature (43), which ultimately contributes to rBCV biogenesis (Fig. 3).

Is Autophagy Involved in rBCV Biogenesis?

Autophagy is a membrane-based process that normally captures intracellular contents, whether cytosolic contents, damaged organelles, or microorganisms, into double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes, to deliver them for degradation to the lysosomal compartment. While it can act as an innate immune antibacterial mechanism, it can also be beneficial to some pathogens (44, 45). Based on the roles of IRE1α and Yip1A in rBCV biogenesis and Brucella replication, autophagosome formation at ERES may provide ER-derived membranes that may contribute to eBCV-to-rBCV conversion; however, whether the canonical autophagic cascade is involved in rBCV biogenesis remains controversial. While a classical autophagic process was originally proposed as a mechanism for rBCV biogenesis in HeLa cells, based on the observation of multimembrane structures on BCVs and accumulation of the lysosomotropic compound monodansylcadaverine (7, 34), such structures are not seen on eBCVs in macrophages (8), nor does the autophagic marker LC3 accumulate on eBCVs, arguing against a canonical autophagic process. Furthermore, inhibition of autophagy via small-interfering-RNA (siRNA)-mediated depletion of specific autophagy components involved in the autophagosome nucleation and elongation steps, namely, ULK1, beclin1, Atg5, Atg7, ATG16L, and LC3B, does not prevent rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication (17). Hence, there is no substantial evidence to support a role of the canonical autophagic cascade in rBCV biogenesis. However, the demonstrated roles of the autophagosome nucleation protein WIPI1 and of the autophagy protein Atg9 in rBCV biogenesis (39) clearly invoke specific autophagy-associated machineries in this process, suggesting that rBCV biogenesis requires a subset of cellular machineries associated with autophagosome formation at ERES and Atg9-mediated delivery of membranes. Further studies are needed to clarify how these autophagy-related events actually contribute to rBCV biogenesis.

Role of the Secretory Pathway in rBCV Biogenesis

Based on the ER nature of the rBCV, the host secretory pathway certainly plays an essential role in the Brucella intracellular cycle. Whether secretory compartments other than the ER, such as the ER-to-Golgi intermediate compartment, the Golgi apparatus, and the trans-Golgi network, are important to the bacterium is a long-standing question, warranted by examples of other intracellular pathogens that exploit these compartments (46). These include Legionella pneumophila, which intercepts Arf1- and Rab1-dependent secretory traffic to acquire ER-derived membranes (47, 48), and Chlamydia trachomatis, which redirects Golgi apparatus-derived lipid trafficking pathways for acquisition of sphingolipids (49, 50). Cellular approaches based on altering specific functions along the secretory pathway using either pharmacological inhibition of host secretion, expression of dominant inactive alleles of small GTPases, or siRNA-mediated depletions have revealed that ER-Golgi secretory traffic is important for rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication (22, 38). Inhibition of Arf1-dependent secretory traffic using brefeldin A or via siRNA treatment impairs rBCV biogenesis to levels similar to those seen with depletion of Sar1 (22, 38). Additionally, depletion of the small GTPases Rab1a and Rab2, which control anterograde and retrograde vesicular traffic between the ER and Golgi apparatus (51), negatively affects replication of B. abortus in macrophages (38), further indicating a complex role of vesicular traffic between these compartments in promoting Brucella proliferation, possibly through acquisition by the eBCV of secretory membranes during their conversion process into the rBCV. Consistent with Brucella exploiting these pathways, host secretory traffic is altered in Brucella-infected cells in a T4SS-dependent manner (30), which argues that the bacterium actively modulates secretory functions via delivery of effectors to promote its intracellular cycle.

Bacterial Effectors of rBCV Biogenesis

The recent discoveries of several VirB T4SS effectors (27–32) and the characterization of the modes of action of some of them (Table 1) have provided opportunities to start deciphering at the molecular level the bacterial mechanisms of rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication. VceC, identified as being coregulated with the VirB T4SS, binds the ER chaperone Grp78/BiP and induces the UPR, which triggers an inflammatory response (42), yet whether it plays a role in rBCV biogenesis has not been elucidated. TcpB/BtpA, a TIR-domain-containing effector that down-modulates proinflammatory responses (52–58), also induces the UPR and promotes bacterial proliferation once rBCVs are formed (41), suggesting that it may not contribute to rBCV biogenesis. SepA, in contrast, is possibly involved in rBCV biogenesis, as a ΔsepA mutant is retained in eBCVs (32), yet its mode of action remains unknown.

TABLE 1.

Brucella T4SS effectors

| Name | ORF in B. abortus | Host target | Function | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RicA | BAB1_1279 | Rab2 | Modulates rBCV biogenesis | 28 |

| VceA | BAB1_1652 | Unknown | Unknown | 27 |

| VceC | BAB1_1058 | Grp78/BiP | UPR activation | 27, 42 |

| BspA | BAB1_0678 | Unknown | Intracellular replication | 30 |

| BspB | BAB1_0712 | COG | Redirects Golgi vesicular traffic; rBCV biogenesis; intracellular replication | 30, 38 |

| BspC | BAB1_0847 | Unknown | Unknown | 30 |

| BspE | BAB1_1675 | Unknown | Unknown | 30 |

| BspF | BAB1_1948 | Unknown | Intracellular replication | 30 |

| BtpA/TcpB | BAB1_0279 | MAL | Inhibition of TLR signaling; UPR induction | 52 |

| BtpB | BAB1_0756 | Unknown | Unknown | 31 |

| SepA | BAB1_1492 | Unknown | eBCV trafficking | 32 |

| BPE005 | BAB1_2005 | Unknown | Unknown | 29 |

| BPE043 | BAB1_1043 | Unknown | Unknown | 29 |

| BPE275 | BAB1_1275 | Unknown | Unknown | 29 |

| BPE123 | BAB1_0123 | Unknown | Unknown | 29 |

The T4SS effectors BspA, BspB, and BspF, which inhibit host protein secretion and promote bacterial replication (30, 38), support the hypothesis that Brucella specifically targets various host secretory functions, possibly for rBCV biogenesis purposes. While the modes of action of BspA and BspF are unknown, that of BspB has been elucidated. BspB is required for rBCV biogenesis and optimal bacterial replication in macrophages (38). This effector is delivered into host cells and traffics to the Golgi apparatus, where it interacts with the conserved oligomeric Golgi (COG) complex (38) (Fig. 3), a CATCHR-family multisubunit tethering complex that serves as an interaction hub on Golgi membranes for secretory Rab GTPases, Golgi tethers, and SNAREs and that regulates intra-Golgi and retrograde vesicular traffic along the secretory pathway (59). COG functions are important for rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication (38), implicating Golgi apparatus-associated functions in the Brucella intracellular cycle. By mechanisms that remain to be defined, BspB-COG interactions alter COG functions and lead to redirection of COG-dependent Golgi retrograde vesicular traffic to BCVs and acquisition of Golgi apparatus-derived membranes (38), demonstrating that Brucella likely recruits membranes from this secretory compartment during rBCV biogenesis, in addition to ER-derived membranes (Fig. 3). Interestingly, inhibition of Rab2-dependent Golgi-to-ER retrograde traffic via depletion of Rab2 suppresses the replication defect of a ΔbspB mutant (38), suggesting that BspB may affect retrograde secretory traffic to redirect COG-dependent Golgi vesicular traffic to the BCV. Interestingly, the T4SS effector RicA is involved in controlling rBCV biogenesis and binds the GDP-bound form of Rab2 (28) (Fig. 3). Although its mode of action is unknown, as it does not show any GEF (guanine nucleotide exchange factor) activity (28), this suggests that Brucella delivers several effectors that may coordinately act to modulate Rab2-dependent vesicular trafficking and promote rBCV biogenesis.

Altogether, the knowledge gained by studying VirB T4SS effectors that target the host secretory pathway has revealed yet another facet of Brucella interactions with this intracellular compartment and emphasizes how the identification and characterization of these effectors are key to a comprehensive understanding of how this bacterium subverts host secretory functions.

THE aBCV

While replication in ER-associated rBCVs is a key step in the pathogenesis of Brucella, how the bacterium completes its intracellular cycle following this proliferation stage has remained unknown for many decades. Unlike many pathogens, which cause cell death to exit the cells in which they have replicated, Brucella prevents cell death programs from being carried out (60, 61), thus preserving its intracellular niche. Starr et al. observed that instead, following proliferation in rBCVs, by 48 h postinfection and afterwards, the Brucella intracellular niche was converted from an ER-derived organelle to large vacuoles harboring features of late endosomal and lysosomal compartments, such as accumulation of LAMP1 and acidification (17). From an ultrastructural standpoint, these vacuoles are surrounded by multiple membranes and originate from the capture of rBCVs by crescent-shaped membrane structures reminiscent of autophagosomes, despite the lack of accumulation of the canonical autophagosome marker LC3 (17) (Fig. 2). The formation of these vacuoles, named aBCVs, requires functions of the canonical autophagy nucleation but not elongation complexes, as depletion or deletion of beclin1, ULK1, and Atg14L, but not that of Atg5, Atg7, Atg4, or Atg16L, blocked their formation (17). aBCV formation therefore seems to require a subset of autophagy-associated molecular machineries, which may typify an alternate autophagic process or indicate that the bacterium actively exploits discrete functions of the canonical autophagy pathway to generate aBCVs.

Importantly, aBCV formation is tightly linked to bacterial egress, as new infection events of adjacent cells occur during the aBCV formation stage and are reduced upon inhibition of aBCV formation (17). Whether bacteria are released in a free state or contained within a membrane-bound vacuole remains to be established, but the maintenance of the originally infected cells argues that bacterial release is a nonlytic event, suggesting an exocytic process (Fig. 1). Based on the autophagic nature of the aBCV, a tempting hypothesis to explain aBCV-dependent bacterial release is that the bacterium takes advantage of the secretory functions of the autophagy pathway (62) to deliver aBCV-enclosed bacteria to the extracellular milieu.

By mediating the final step of the Brucella intracellular cycle, aBCV formation is likely controlled by the bacterium, potentially via the VirB T4SS. Testing this hypothesis is challenging, as the preceding step of rBCV formation is T4SS dependent, precluding the classical use of reverse genetics and VirB T4SS-deficient mutants. Transient intracellular production of the VirB11 ATPase via a tightly controlled promoter, which energizes the T4SS, allows rBCV biogenesis and bacterial replication prior to T4SS intracellular inactivation and showed a requirement for a functional VirB apparatus in aBCV formation and bacterial egress, indicating that this final step of the Brucella intracellular cycle is likely controlled by T4SS effectors (63). Their future identification and characterization will likely shed light on the molecular mechanisms of aBCV formation and bacterial egress.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Bacteria of the genus Brucella belong to a phylogenetic group closely associated with eukaryotic hosts. In this context, Brucella’s long-standing coevolution with mammalian hosts has shaped its complex intracellular cycle into the sequential exploitation of intracellular compartments of the endocytic, secretory, and autophagy pathways. Brucella uses an array of T4SS-delivered effectors and other virulence factors to modulate discrete functions of these compartments, modifying its original phagosome into an ER-associated replication-permissive organelle that subsequently coopts autophagic functions for completion of the bacterium’s intracellular cycle, thus ensuring its survival, proliferation, and egress. While a few T4SS effectors have been identified, much remains to be understood about their modes of action and contributions to Brucella’s intracellular cycle. Future characterization of these proteins not only will reveal unsuspected aspects of Brucella intracellular strategies but also will teach us a great deal about host cell functions and their roles in many aspects of bacterial pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are most grateful to Andrew Rader for graphical assistance with figures. This work was supported by NIH grants AI129992 and AI127830.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moreno E. 2014. Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. Front Microbiol 5:213 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00213. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, Tsianos E. 2005. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med 352:2325–2336 10.1056/NEJMra050570. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappas G, Papadimitriou P, Akritidis N, Christou L, Tsianos EV. 2006.The new global map of human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis 6:91–99 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70382-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atluri VL, Xavier MN, de Jong MF, den Hartigh AB, Tsolis RM. 2011. Interactions of the human pathogenic Brucella species with their hosts. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:523–541 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102905. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celli J. 2015. The changing nature of the Brucella-containing vacuole. Cell Microbiol 17:951–958 10.1111/cmi.12452. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson TD, Cheville NF, Meador VP. 1986. Pathogenesis of placentitis in the goat inoculated with Brucella abortus. II. Ultrastructural studies. Vet Pathol 23:227–239 10.1177/030098588602300302. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pizarro-Cerdá J, Méresse S, Parton RG, van der Goot G, Sola-Landa A, Lopez-Goñi I, Moreno E, Gorvel JP. 1998. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect Immun 66:5711–5724. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celli J, de Chastellier C, Franchini D-M, Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel J-P. 2003. Brucella evades macrophage killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J Exp Med 198:545–556 10.1084/jem.20030088. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salcedo SP, Chevrier N, Lacerda TLS, Ben Amara A, Gerart S, Gorvel VA, de Chastellier C, Blasco JM, Mege J-L, Gorvel J-P. 2013. Pathogenic brucellae replicate in human trophoblasts. J Infect Dis 207:1075–1083 10.1093/infdis/jit007. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Detilleux PG, Deyoe BL, Cheville NF. 1990. Entry and intracellular localization of Brucella spp. in Vero cells: fluorescence and electron microscopy. Vet Pathol 27:317–328 10.1177/030098589002700503. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Detilleux PG, Deyoe BL, Cheville NF. 1990. Penetration and intracellular growth of Brucella abortus in nonphagocytic cells in vitro. Infect Immun 58:2320–2328. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arenas GN, Staskevich AS, Aballay A, Mayorga LS. 2000. Intracellular trafficking of Brucella abortus in J774 macrophages. Infect Immun 68:4255–4263 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4255-4263.2000. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comerci DJ, Martínez-Lorenzo MJ, Sieira R, Gorvel J-P, Ugalde RA. 2001. Essential role of the VirB machinery in the maturation of the Brucella abortus-containing vacuole. Cell Microbiol 3:159–168 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00102.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porte F, Liautard JP, Köhler S. 1999. Early acidification of phagosomes containing Brucella suis is essential for intracellular survival in murine macrophages. Infect Immun 67:4041–4047. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boschiroli ML, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Foulongne V, Michaux-Charachon S, Bourg G, Allardet-Servent A, Cazevieille C, Liautard JP, Ramuz M, O’Callaghan D. 2002. The Brucella suis virB operon is induced intracellularly in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:1544–1549 10.1073/pnas.032514299. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starr T, Ng TW, Wehrly TD, Knodler LA, Celli J. 2008. Brucella intracellular replication requires trafficking through the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment. Traffic 9:678–694 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00718.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starr T, Child R, Wehrly TD, Hansen B, Hwang S, López-Otin C, Virgin HW, Celli J. 2012. Selective subversion of autophagy complexes facilitates completion of the Brucella intracellular cycle. Cell Host Microbe 11:33–45 10.1016/j.chom.2011.12.002. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sedzicki J, Tschon T, Low SH, Willemart K, Goldie KN, Letesson J-J, Stahlberg H, Dehio C. 2018. 3D correlative electron microscopy reveals continuity of Brucella-containing vacuoles with the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci 131:jcs210799 10.1242/jcs.210799. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sieira R, Comerci DJ, Sánchez DO, Ugalde RA. 2000. A homologue of an operon required for DNA transfer in Agrobacterium is required in Brucella abortus for virulence and intracellular multiplication. J Bacteriol 182:4849–4855 10.1128/JB.182.17.4849-4855.2000. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delrue RM, Martinez-Lorenzo M, Lestrate P, Danese I, Bielarz V, Mertens P, De Bolle X, Tibor A, Gorvel JP, Letesson JJ. 2001. Identification of Brucella spp. genes involved in intracellular trafficking. Cell Microbiol 3:487–497 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00131.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Callaghan D, Cazevieille C, Allardet-Servent A, Boschiroli ML, Bourg G, Foulongne V, Frutos P, Kulakov Y, Ramuz M. 1999. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol 33:1210–1220 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01569.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celli J, Salcedo SP, Gorvel J-P. 2005. Brucella coopts the small GTPase Sar1 for intracellular replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:1673–1678 10.1073/pnas.0406873102. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartigh den AB, Rolán HG, de Jong MF, Tsolis RM. 2008. VirB3 to VirB6 and VirB8 to VirB11, but not VirB7, are essential for mediating persistence of Brucella in the reticuloendothelial system. J Bacteriol 190:4427–4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lestrate P, Delrue RM, Danese I, Didembourg C, Taminiau B, Mertens P, De Bolle X, Tibor A, Tang CM, Letesson JJ. 2000. Identification and characterization of in vivo attenuated mutants of Brucella melitensis. Mol Microbiol 38:543–551 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02150.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green ER, Mecsas J. 2016. Bacterial secretion systems: an overview. Microbiol Spectr 4(1):VMBF-0012-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juhas M, Crook DW, Hood DW. 2008. Type IV secretion systems: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and virulence. Cell Microbiol 10:2377–2386 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01187.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Jong MF, Sun Y-H, den Hartigh AB, van Dijl JM, Tsolis RM. 2008. Identification of VceA and VceC, two members of the VjbR regulon that are translocated into macrophages by the Brucella type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol 70:1378–1396 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06487.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Barsy M, Jamet A, Filopon D, Nicolas C, Laloux G, Rual J-F, Muller A, Twizere J-C, Nkengfac B, Vandenhaute J, Hill DE, Salcedo SP, Gorvel J-P, Letesson J-J, De Bolle X. 2011. Identification of a Brucella spp. secreted effector specifically interacting with human small GTPase Rab2. Cell Microbiol 13:1044–1058 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01601.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchesini MI, Herrmann CK, Salcedo SP, Gorvel J-P, Comerci DJ. 2011. In search of Brucella abortus type IV secretion substrates: screening and identification of four proteins translocated into host cells through VirB system. Cell Microbiol 13:1261–1274 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01618.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myeni S, Child R, Ng TW, Kupko JJ III, Wehrly TD, Porcella SF, Knodler LA, Celli J. 2013. Brucella modulates secretory trafficking via multiple type IV secretion effector proteins. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003556 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003556. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salcedo SP, Marchesini MI, Degos C, Terwagne M, Von Bargen K, Lepidi H, Herrmann CK, Santos Lacerda TL, Imbert PR, Pierre P, Alexopoulou L, Letesson JJ, Comerci DJ, Gorvel JP. 2013. BtpB, a novel Brucella TIR-containing effector protein with immune modulatory functions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:28 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00028. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Döhmer PH, Valguarnera E, Czibener C, Ugalde JE. 2014. Identification of a type IV secretion substrate of Brucella abortus that participates in the early stages of intracellular survival. Cell Microbiol 16:396–410 10.1111/cmi.12224. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaves-Olarte E, Guzmán-Verri C, Méresse S, Desjardins M, Pizarro-Cerdá J, Badilla J, Gorvel J-P, Moreno E. 2002. Activation of Rho and Rab GTPases dissociates Brucella abortus internalization from intracellular trafficking. Cell Microbiol 4:663–676 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00221.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pizarro-Cerdá J, Moreno E, Sanguedolce V, Mege JL, Gorvel JP. 1998. Virulent Brucella abortus prevents lysosome fusion and is distributed within autophagosome-like compartments. Infect Immun 66:2387–2392. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieira R, Comerci DJ, Pietrasanta LI, Ugalde RA. 2004. Integration host factor is involved in transcriptional regulation of the Brucella abortus virB operon. Mol Microbiol 54:808–822 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04316.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deghelt M, Mullier C, Sternon J-F, Francis N, Laloux G, Dotreppe D, Van der Henst C, Jacobs-Wagner C, Letesson J-J, De Bolle X. 2014. G1-arrested newborn cells are the predominant infectious form of the pathogen Brucella abortus. Nat Commun 5:4366 10.1038/ncomms5366. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Budnik A, Stephens DJ. 2009. ER exit sites—localization and control of COPII vesicle formation. FEBS Lett 583:3796–3803 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.038. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller CN, Smith EP, Cundiff JA, Knodler LA, Bailey Blackburn J, Lupashin V, Celli J. 2017. A Brucella type IV effector targets the COG tethering complex to remodel host secretory traffic and promote intracellular replication. Cell Host Microbe 22:317–329.e7 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.017. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taguchi Y, Imaoka K, Kataoka M, Uda A, Nakatsu D, Horii-Okazaki S, Kunishige R, Kano F, Murata M. 2015. Yip1A, a novel host factor for the activation of the IRE1 pathway of the unfolded protein response during Brucella infection. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004747 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004747. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter P, Ron D. 2011. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334:1081–1086 10.1126/science.1209038. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith JA, Khan M, Magnani DD, Harms JS, Durward M, Radhakrishnan GK, Liu Y-P, Splitter GA. 2013. Brucella induces an unfolded protein response via TcpB that supports intracellular replication in macrophages. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003785 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003785. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Jong MF, Starr T, Winter MG, den Hartigh AB, Child R, Knodler LA, van Dijl JM, Celli J, Tsolis RM. 2013. Sensing of bacterial type IV secretion via the unfolded protein response. mBio 4:e00418-12 10.1128/mBio.00418-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qin Q-M, Pei J, Ancona V, Shaw BD, Ficht TA, de Figueiredo P. 2008. RNAi screen of endoplasmic reticulum-associated host factors reveals a role for IRE1α in supporting Brucella replication. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000110–e1000116 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000110. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. 2011. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 469:323–335 10.1038/nature09782. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang J, Brumell JH. 2014. Bacteria-autophagy interplay: a battle for survival. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:101–114 10.1038/nrmicro3160. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asrat S, de Jesús DA, Hempstead AD, Ramabhadran V, Isberg RR. 2014. Bacterial pathogen manipulation of host membrane trafficking. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 30:79–109 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013439. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kagan JC, Roy CR. 2002. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat Cell Biol 4:945–954 10.1038/ncb883. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kagan JC, Stein M-P, Pypaert M, Roy CR. 2004. Legionella subvert the functions of Rab1 and Sec22b to create a replicative organelle. J Exp Med 199:1201–1211 10.1084/jem.20031706. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hackstadt T, Rockey DD, Heinzen RA, Scidmore MA. 1996. Chlamydia trachomatis interrupts an exocytic pathway to acquire endogenously synthesized sphingomyelin in transit from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. EMBO J 15:964–977 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00433.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scidmore MA, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T. 1996. Sphingolipids and glycoproteins are differentially trafficked to the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion. J Cell Biol 134:363–374 10.1083/jcb.134.2.363. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhuin T, Roy JK. 2014. Rab proteins: the key regulators of intracellular vesicle transport. Exp Cell Res 328:1–19 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.027. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salcedo SP, Marchesini MI, Lelouard H, Fugier E, Jolly G, Balor S, Muller A, Lapaque N, Demaria O, Alexopoulou L, Comerci DJ, Ugalde RA, Pierre P, Gorvel J-P. 2008. Brucella control of dendritic cell maturation is dependent on the TIR-containing protein Btp1. PLoS Pathog 4:e21 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040021. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jakka P, Namani S, Murugan S, Rai N, Radhakrishnan G. 2017. The Brucella effector protein TcpB induces degradation of inflammatory caspases and thereby subverts non-canonical inflammasome activation in macrophages. J Biol Chem 292:20613–20627 10.1074/jbc.M117.815878. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alaidarous M, Ve T, Casey LW, Valkov E, Ericsson DJ, Ullah MO, Schembri MA, Mansell A, Sweet MJ, Kobe B. 2014. Mechanism of bacterial interference with TLR4 signaling by Brucella Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing protein TcpB. J Biol Chem 289:654–668 10.1074/jbc.M113.523274. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaudhary A, Ganguly K, Cabantous S, Waldo GS, Micheva-Viteva SN, Nag K, Hlavacek WS, Tung C-S. 2012. The Brucella TIR-like protein TcpB interacts with the death domain of MyD88. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 417:299–304 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.104. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sengupta D, Koblansky A, Gaines J, Brown T, West AP, Zhang D, Nishikawa T, Park SG, Roop RM II, Ghosh S. 2010. Subversion of innate immune responses by Brucella through the targeted degradation of the TLR signaling adapter, MAL. J Immunol 184:956–964 10.4049/jimmunol.0902008. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radhakrishnan GK, Yu Q, Harms JS, Splitter GA. 2009. Brucella TIR domain-containing protein mimics properties of the Toll-like receptor adaptor protein TIRAP. J Biol Chem 284:9892–9898 10.1074/jbc.M805458200. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cirl C, Wieser A, Yadav M, Duerr S, Schubert S, Fischer H, Stappert D, Wantia N, Rodriguez N, Wagner H, Svanborg C, Miethke T. 2008. Subversion of Toll-like receptor signaling by a unique family of bacterial Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing proteins. Nat Med 14:399–406 10.1038/nm1734. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willett R, Ungar D, Lupashin V. 2013. The Golgi puppet master: COG complex at center stage of membrane trafficking interactions. Histochem Cell Biol 140:271–283 10.1007/s00418-013-1117-6. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cui G, Wei P, Zhao Y, Guan Z, Yang L, Sun W, Wang S, Peng Q. 2014. Brucella infection inhibits macrophages apoptosis via Nedd4-dependent degradation of calpain2. Vet Microbiol 174:195–205 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.08.033. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gross A, Terraza A, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Liautard JP, Dornand J. 2000. In vitro Brucella suis infection prevents the programmed cell death of human monocytic cells. Infect Immun 68:342–351 10.1128/IAI.68.1.342-351.2000. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kimura T, Jia J, Claude-Taupin A, Kumar S, Choi SW, Gu Y, Mudd M, Dupont N, Jiang S, Peters R, Farzam F, Jain A, Lidke KA, Adams CM, Johansen T, Deretic V. 2017. Cellular and molecular mechanism for secretory autophagy. Autophagy 13:1084–1085 10.1080/15548627.2017.1307486. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith EP, Miller CN, Child R, Cundiff JA, Celli J. 2016. Postreplication roles of the Brucella VirB type IV secretion system uncovered via conditional expression of the VirB11 ATPase. mBio 7:e01730-16. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]