Watch a video presentation of this article

Watch the interview with the author

Abbreviations

- PBC

primary biliary cirrhosis

- UDCA

ursodeoxycholic acid.

A number of recent publications have significantly advanced our understanding of the pathogenesis and epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), and they have often raised even more questions. In this brief review, we highlight some recent research findings and new controversies that highlight our changing appreciation of the epidemiology and natural history of PBC.

Epidemiology

In the past few decades, there has been a progressive change in our appreciation of the epidemiology of PBC, specifically with respect to the disease's prevalence and incidence.1 Originally, PBC was reported to be a very rare disease; this was likely related to small sample sizes and problems with the methodologies that were employed to measure this. In addition, reported incidence and prevalence rates for PBC have varied dramatically between studies and geographical regions.1 More recently, with better methodological approaches and larger patient cohorts, a clearer picture of the epidemiology of PBC has emerged.2 In a number of studies, the incidence of PBC has been reported to be stable or increasing.1, 2, 3 In conjunction with these observations, most studies have indicated that the prevalence of PBC in many well‐defined geographical regions is increasing.1, 2, 3 For example, using an administrative database for a Canadian health region (a government‐funded single‐payer system), we reported that the overall age/sex‐adjusted annual incidence of PBC between 1996 and 2002 remained stable at 30.3 cases per million (48.4 cases per million for women and 10.4 cases per million for men); however, the prevalence of PBC increased from 100 cases per million in 1996 to 227 cases per million in 2003.3 An increase in the incidence of PBC in some studies may be explained by a higher case detection rate or by a true increase in the incidence. A higher prevalence rate can be explained by the diagnosis of patients with PBC at an earlier time point and/or by improved outcomes. In any event, these observations suggest that the overall societal burden of PBC is increasing, and this has implications for both health care providers and health care funders.

PBC, like all autoimmune diseases, is thought to result from an interplay between genetics and environmental triggers. A familial linkage for PBC has been widely recognized for decades. However, our understanding of the genetic framework underlying PBC has been dramatically enhanced in the past few years through the development of large cohorts of well‐characterized PBC patients in a number of countries; these have allowed the performance of a number of highly powered genome‐wide association studies and ImmunoChip association studies (reviewed by Mells et al.4, 5). These studies have allowed us to better understand the complexity of PBC genetics and have identified strong human leukocyte antigen associations with the development of PBC. In addition, these studies have delineated a number of non–human leukocyte antigen gene loci important to PBC development, including genes associated with the regulation of the innate immune response, T cell activation and differentiation, antigen presentation and dendritic cell function, and B cell function and signaling.4 PBC appears to share a number of disease risk loci with many other autoimmune diseases, including celiac disease, Crohn's disease, and multiple sclerosis4; this demonstrates that different autoimmune diseases have many parallel genetic risk factors. Interestingly, genome‐wide association studies from different countries have also indicated that PBC is genetically heterogeneous, and this adds to the complexity of PBC genetics and disease predisposition.6 Importantly, the PBC gene risk loci identified in these studies explain only a small part of PBC heritability.

Environmental links to PBC development and disease progression have been suggested for many years, and they include cigarette smoking, nail polish use, and infections.2 An environmental cause of PBC is supported by reports from a number of countries of disease clustering. Specifically, areas of increased PBC prevalence have been identified in England, the United States, and Japan.7, 8, 9 Interestingly, increased PBC prevalence in these areas has been epidemiologically linked to a variety of environmental exposures, including atomic bomb radiation, contaminated water supplies, and toxic waste dumps.7, 8, 9, 10 However, no specific environmental trigger for PBC has been definitively identified to date. According to interesting work from the Newcastle group, PBC cases in the northeastern part of England show seasonal variation (with the peak incidence in June) and space‐time clustering that cannot be explained by variations in population density.11, 12 These fascinating observations suggest a possible role for a transient environmental agent, possibly an infectious agent, in the pathogenesis of PBC that may act as a trigger in those who are exposed and are genetically susceptible. Immigration studies have provided additional support for the hypothesis that environmental exposure may contribute to the development of PBC. Individuals who emigrate from the United Kingdom, where there is a relatively high prevalence of PBC, to Australia, which has a low prevalence of PBC, exhibit a reduced prevalence of PBC.13 In contrast, immigrants to the United Kingdom from the Indian subcontinent demonstrate a higher prevalence of PBC than has been reported for the Indian population.14

Natural History

The natural history of PBC appears to have changed over the past few decades from a slow, almost universally progressive disease often resulting in liver failure and death or liver transplantation to a more clinically heterogeneous disease with various rates of disease progression in some and with virtual clinical remission in others.15 These clinical observations can likely be explained, at least in part, by the earlier identification of PBC patients through more widely available routine laboratory testing (e.g., liver enzyme measurement as part of life insurance applications), enhanced physician education and awareness of PBC, the increased routine use of abdominal imaging, and the wider availability of anti‐mitochondrial antibody (AMA) testing. Individuals diagnosed with PBC in this fashion are more likely to be asymptomatic and have earlier histological disease and less fibrosis. Certainly, this earlier identification of patients would be expected to directly contribute to the increased prevalence of PBC that has been documented in a number of studies (as discussed previously).

The introduction and wider use of the hydrophilic bile acid ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) for treating PBC has had a significant impact on disease progression, and it changes the natural history of the disease in those who respond to treatment.15 Although some disagree about the benefits of UDCA, the use of UDCA to treat PBC patients is recommended in the disease treatment guidelines issued by the major liver disease–focused associations, including the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver.16, 17 In responders, UDCA treatment reduces disease progression and the need for liver transplantation.15, 16, 17 Different groups with a dedicated interest in PBC have developed a number of scoring systems that can be used to define the response to UDCA and identify more clearly those patients with more favorable expected clinical outcomes.18 These scoring systems are clinically very useful for better defining probabilities of PBC progression during therapy. Consistent with this improvement in the natural history of PBC with the institution of UDCA therapy is the widely reported reduction in the relative frequency of PBC patients undergoing liver transplantation at many liver transplant centers over the past decade.19 Furthermore, this reduction in the number of PBC patients undergoing liver transplantation has occurred despite the reported increase in the prevalence of PBC (as outlined previously), and it is consistent with a beneficial effect of UDCA treatment in PBC patients. However, despite these improved outcomes for many PBC patients, a significant proportion of PBC patients do not respond or incompletely respond to UDCA treatment. These patients appear to continue to exhibit progressive disease, and the need for newer therapies to treat these individuals is clear.15, 16

Summary

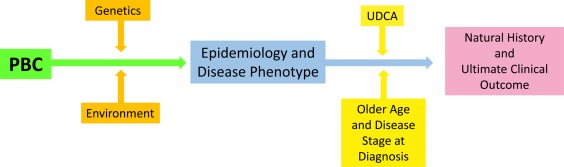

PBC is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. Recent findings from robust genome‐wide association studies have provided novel insights into the genetic framework of PBC: they have indicated a significant overlap of risk gene alleles with numerous other autoimmune diseases and have identified a number of potential genetic modifiers of the epidemiology and natural history of PBC. Moreover, over the past few decades, the natural history of the disease has changed, mostly because of the wide use of UDCA therapy (Fig. 1). However, many patients still exhibit progressive disease, and newer therapeutic developments are clearly needed to improve disease outcomes for UDCA nonresponders and partial responders.

Figure 1.

Genetics and the environment drive the disease phenotype and epidemiology of PBC. Subsequently, the age and disease stage at the time of diagnosis and the response to treatment with UDCA affect the natural history of PBC and the patient's ultimate outcome.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Podda M, Selmi C, Lleo A, Moroni L, Invernizzi P. The limitations and hidden gems of the epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis. J Autoimmun 2013;46:81‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gross RG, Odin JA. Recent advances in the epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2008;12:289‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Myers RP, Shaheen AA, Fong A, Burak KW, Wan A, Swain MG, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cirrhosis in a Canadian health region: a population‐based study. Hepatology 2009;50:1884‐1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mells GF, Kaser A, Karlsen TH. Novel insights into autoimmune liver diseases provided by genome‐wide association studies. J Autoimmun 2013;46:41‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mells, et al. Risk Factors for PBC: genes, bugs and family. Clin Liver Dis (In press). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakamura M, Nishida N, Kawashima M, Aiba Y, Tanaka A, Yasunami M, et al. Genome‐wide association study identifies TNFSF15 and POU2AF1 as susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis in the Japanese population. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:721‐728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ohba K, Omagari K, Kinoshita H, Soda H, Masuda J, Hazama H, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis among atomic bomb survivors in Nagasaki, Japan. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:845‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Metcalf JV, Bhopal RS, Gray J, Howel D, James OF. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis in the city of Newcastle upon Tyne, England. Int J Epidemiol 1997;26:830‐836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ala A, Stanca CM, Bu‐Ghanim M, Ahmado I, Branch AD, Schiano TD, et al. Increased prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis near Superfund toxic waste sites. Hepatology 2006;43:525‐531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Triger DR. Primary biliary cirrhosis: an epidemiological study. Br Med J 1980;281:772‐775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McNally RJ, James PW, Ducker S, James OF. Seasonal variation in the patient diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis: further evidence for an environmental component to etiology. Hepatology 2011;54:2099‐2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McNally RJ, Ducker S, James OF. Are transient environmental agents involved in the cause of primary biliary cirrhosis? Evidence from space‐time clustering analysis. Hepatology 2009;50:1169‐1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anand AC, Elias E, Neuberger JM. End‐stage primary biliary cirrhosis in a first generation migrant south Asian population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996;8:663‐666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sood S, Gow PJ, Christie JM, Angus PW. Epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis in Victoria, Australia: high prevalence in migrant populations. Gastroenterology 2004;127:470‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee YM, Kaplan MM. The natural history of PBC: has it changed? Semin Liver Dis 2005;25:321‐326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ; for American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2009;50:291‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol 2009;51:237‐267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Corpechot C, Chazouilleres O, Poupon R. Early primary biliary cirrhosis: biochemical response to treatment and prediction of long‐term outcome. J Hepatol 2011;55:1361‐1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carbone M, Neuberger J. Liver transplantation in PBC and PSC: indications and disease recurrence. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2011;35:446‐454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]