Watch a video presentation of this article

Definition

“Budd‐Chiari syndrome” (BCS) is used as an eponym for “hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction,” independent of the level or mechanism of obstruction.1 Cardiac and pericardial diseases and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome are excluded from this definition. BCS is further divided into “secondary” BCS when related to compression or invasion by a lesion originating outside the veins (benign or malignant tumor, abscess, cyst, etc) and “primary” BCS when related to a primarily venous disease (thrombosis or phlebitis). Secondary BCS will not be discussed here. Primary BCS is a rare disorder (estimated incidence ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 per million per year).2

Causes

BCS is closely associated with prothrombotic conditions. In a recent European prospective multicenter cohort study, 84% of the patients had at least one thrombotic risk factor, and 46% had more than one such factor (Table 1), which is in line with several previous retrospective surveys.2, 3, 4 Therefore, routine screening for all thrombotic risk factors is recommended in BCS patients at diagnosis and, if possible, before initiating anticoagulation therapy (Table 1).1 Myeloproliferative neoplasms, which constitute the leading cause, can be overlooked in BCS patients. Indeed, splenomegaly can be attributed to portal hypertension, whereas hemodilution and hypersplenism decrease peripheral blood cell counts and thus may mask the peripheral blood features of myeloproliferation.5 In many patients, JAK2V617F screening overcomes this difficulty and identifies myeloproliferative neoplasms in patients without typical hematologic features. However, in 5% to 10% of BCS patients, this specific mutation is undetectable, whereas bone marrow biopsy or assessment of endogenous erythroid colonies provided evidence for a myeloproliferative disease.6

Table 1.

Prevalence and Proposed Workup for Acquired and Inherited Risk Factors for BCS

| Risk Factor | Prevalence (%) | Proposed Workup for Investigating Underlying Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Inherited thrombophilia | ||

| Factor V Leiden | 12 | Activated protein C resistance. To be confirmed in patients with positive results, by molecular testing for R605Q factor V mutation |

| Prothrombin gene G20210A mutation | 3 | Molecular testing for G20210A mutation |

| Protein C deficiency | 3 | Results can be interpreted only in patients with normal coagulation factor levels. Diagnosis based on decreased activity levels. Inherited deficiency can be established only with a positive test in first‐degree relatives. |

| Protein S deficiency | 2 | |

| Antithrombin deficiency | 3 | |

| Acquired thrombophilia | ||

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 24 | Diagnosis based on repeatedly detectable anticardiolipin antibodies at high level, or lupus anticoagulant or antibeta2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies. Many patients with BCS have nonspecific fluctuating, low‐titer antiphospholipid antibodies in the absence of antiphospholipid syndrome. |

| Hyperhomocysteinemia | 18 | Increased serum homocysteine level prior to disease. Uncertain value of C677T homozygous polymorphism. In many patients, a definite diagnosis for underlying hyperhomocysteinemia will not be possible. Blood folate and serum vitamin B12 levels may be useful. |

| Paroxysmalnocturnal hemoglobinuria | 10 | CD55 and CD59 deficient clone at flow‐cytometry of peripheral blood cells |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) | 33 | JAK2V617F mutation in peripheral granulocyte DNA. In patients testing negative, MPL and JAK2 exon 12 mutations. If further negative, consider bone marrow biopsy for demonstrating clusters of dystrophic megakaryocytes, particularly in patients with normal blood cell counts and splenomegaly. |

| Polycythemia vera | 18 | |

| Essential thrombocythemia | 8 | |

| Idiopathic myelofibrosis | 3 | |

| Unclassified or occult | 5 | |

| Hormonal factors | Medical history | |

| Oral contraceptive use | 19 | |

| Pregnancy within 3 months before diagnosis | 4 | |

| Systemic diseases | 18 | Including connective tissue disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, Behcet disease, HIV infection. |

| Diagnosis based on a set of conventional criteria. | ||

| Local factors | 6 | Intraabdominal infection, sepsis, or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. |

Clinical and Laboratory Features

BCS presentation is highly heterogeneous with fulminant, acute, chronic, and asymptomatic forms.3 Abdominal pain, ascites, liver and spleen enlargement, and portal hypertension are important features, as well as a prominent dilation of subcutaneous veins of the trunk in those patients with longstanding inferior vena cava (IVC) obstruction. Each or all of these features may, however, be lacking. Liver function tests are altered to a various extent. Given the absence of specific clinical or laboratory signs for BCS, this diagnosis should be widely considered in patients with acute or chronic liver disease.1

BCS is diagnosed by the demonstration of an obstructed hepatic venous outflow tract.2 Doppler ultrasound by an experienced examiner aware of the diagnostic suspicion is the most effective and reliable diagnostic means. MRI and CT scan confirm the diagnosis, being most useful in the absence of an experienced Doppler ultrasound examiner (Fig. 1).1, 2 The arguments for an obstruction comprise a dilatation of the vein upstream to an obstacle; the presence of a solid endoluminal material; the transformation of the veins into a cord devoid of flow signal; and venous collaterals, seen as abnormal circulating structures branching to or from the hepatic veins or inferior vena cava (IVC). Patchy enhancement of hepatic parenchyma is only suggestive of a perfusion defect, which can be seen in many other vascular disorders of the liver. The hypertrophy of the central parts of the liver (mainly the caudate lobe) is another feature suggesting BCS, but it is not specific for this disease. Nowadays, invasive procedures such as liver biopsy and X‐ray venography are needed only in patients where the diagnosis remains uncertain after noninvasive imaging.1, 2

Figure 1.

MRI of a Budd‐Chiari syndrome (BCS) liver (axial slice, T1, arterial phase after intravenous gadolinium chelate injection). The liver is heterogeneous. The three major hepatic veins (black arrows) appear as hypointense cords. Segment 1 is enlarged (white arrow heads). Courtesy of Maxime Ronot, MD.

Treatment

Current therapeutic strategy in BCS aims at minimal invasiveness and is based on individual response to previous therapy rather than on the actual severity of the patient's status (Table 2; Fig. 2).4 Nonspecific complications of chronic liver disease (gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding, ascites, renal dysfunction bacterial infection, and encephalopathy) can be managed according to the guidelines proposed for patients with cirrhosis and will not be discussed in this review. BCS‐specific scores have been developed (Clichy, Rotterdam, Revised Clichy, and BCS‐transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt [TIPS] scores).7 These scores, as well as nonspecific Child‐Pugh and MELD scores, are significantly associated with survival of BCS patients.4, 7 However, none of these scores has a sufficient predictive accuracy to be used for individual patient management.7 A group of patients with particularly poor prognosis, ie, those with high alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (> 5 times the upper limit of normal values) that decrease slowly, might require rapid progression to invasive procedures.7

Table 2.

Proposed Treatment Strategy for BCS

| Step | Treatment |

|---|---|

| 1 | Treat ascites, GI bleeding, bacterial infection, renal dysfunction, and encephalopathy as recommended for cirrhosis. |

| Give specific state‐of‐the‐art therapy for underlying prothrombotic conditions (eg, myeloproliferative disease, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, antiphospholipid syndrome, Behcet's disease). | |

| Stop oral contraceptives. | |

| Initiate anticoagulation as soon as the diagnosis has been established and after prophylaxis for bleeding related to portal hypertension has been instituted. | |

| Prefer low molecular‐weight heparin to unfractionated heparin unless there is a need for immediate cessation of anticoagulation. | |

| Closely monitor for heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. Give daparanoid sulfate as an alternative. | |

| Target anti‐Xa level at 0.5 IU/mL. | |

| When this level cannot be achieved with usual doses, check for primary or secondary deficiency in antithrombin and give recombinant antithrombin as appropriate. | |

| Substitute heparin for permanent oral anticoagulation as soon as invasive therapy is deemed not required. | |

| Target an INR 2–3, or preferably a factor II level of 25%‐35%. | |

| Preferably refer the patient to an anticoagulation clinic. | |

| Consider discontinuing anticoagulants before paracentesis, particularly in patients undergoing planned therapeutic paracentesis, given an increased risk of major bleeding | |

| 2 | Check for short‐length stenosis of inferior vena cava or hepatic veins using percutaneous angiography, if needed, and treat appropriately with angioplasty, with or without stenting |

| 3 | When the patient fails to improve steadily with the previous measures, proceed to transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) insertion, usually through the transcaval route. |

| 4 | When TIPS insertion fails or the patient does not improve or the patient develops chronic or recurrent encephalopathy, consider liver transplantation. |

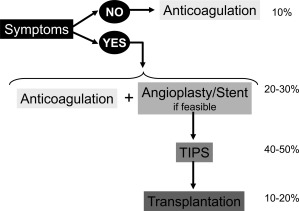

Figure 2.

Proposed treatment strategy in patients with primary BCS. Numbers on the right represent the approximate proportion of patients who can be permanently controlled at each step of the strategy. Data are based on recent cohort studies.3, 4

This therapeutic strategy has allowed for the achievement of 5‐year survival rates in the order of 75%.4 This good survival expectancy is usually obtained, together with complete resolution of clinical signs and symptoms and marked improvement in liver function tests, which result in a good quality of life.

Other Issues in BCS

One important consideration in BCS is the increasingly expressed desire for pregnancy in these predominantly young female patients. When BCS has been recognized and well‐controlled, pregnancy should not be contraindicated as maternal outcome, and fetal outcome beyond gestation week 20 appears to be good. Nevertheless, patients should be fully informed of the possible risks of such pregnancies.8

The second issue in BCS is the frequent development of macronodules in patients with well‐controlled BCS. This aspect is addressed in this issue of Clinical Liver Disease by Vilgrain and colleagues. Briefly, most of these nodules are benign, mimicking focal nodular hyperplasia at imaging and at pathologic examination, and attributed to decreased portal perfusion and/or increased arterial perfusion.9 However, hepatocellular carcinoma also occurs in BCS patients and appears to be just as significant a long‐term complication as it is in other chronic liver diseases.10 Patients with membranous obstruction of the IVC appear to be at particularly high risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma.10 An algorithm for the management of nodule in BCS patients is proposed in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Proposed algorithm for the management of hepatic nodules in BCS patients. In the context of BCS, the presence of liver nodule(s) with serum AFP level > 15 ng/ mL is highly suggestive of malignancy, and biopsy of the largest nodule should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). If serum AFP level is normal (< 15 ng/ mL), biopsy should be performed in heterogeneous nodules with diameter > 3 cm to rule out HCC. In patients with homogeneous nodules smaller than 3 cm and serum AFP level < 15 ng/ mL, an enhanced surveillance with 3‐month intervals should be performed in the first year after the initial nodule detection, followed by surveillance with 6‐month intervals if the lesion remains unchanged over this period.

The third issue in BCS is the outcome of the underlying diseases. This concern is illustrated by the fact that, by 12 years of follow‐up, myelofibrosis or acute leukemia has been reported to occur in up to 30% of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms who were diagnosed with splanchnic vein thrombosis.5

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- BCS

Budd‐Chiari Syndrome

- GI

gastrointestinal

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- IVC

inferior vena cava

- JAK2

Janus kinase 2

- TIPS

transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- MPL

myeloproliferative leukemia

- MPN

myeloproliferative neoplasms

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. LD DeLeve, DC Valla, G Garcia-Tsao. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology 2009;49:1729‐1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DC Valla. Primary Budd‐Chiari syndrome. J Hepatol 2009;50:195‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. S Darwish Murad, A Plessier, M Hernandez-Guerra, F Fabris, CE Eapen, MJ Bahr, et al. Etiology, management, and outcome of the Budd‐Chiari syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:167‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. S Seijo, A Plessier, J Hoekstra, A Dell'era, D Mandair, K Rifai, et al. Good long-term outcome of Budd‐Chiari syndrome with a step-wise management. Hepatology 2013;57:1962‐1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chait Y, Condat B, Cazals‐Hatem D, Rufat P, Atmani S, Chaoui D, et al. Relevance of the criteria commonly used to diagnose myeloproliferative disorder in patients with splanchnic vein thrombosis. Br J Haematol 2005;129:553‐560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kiladjian JJ, Cervantes F, Leebeek FW, Marzac C, Cassinat B, Chevret S, et al. The impact of JAK2 and MPL mutations on diagnosis and prognosis of splanchnic vein thrombosis. A report on 241 cases. Blood 2008;15;111:4922‐4929. doi: 10.1182/blood‐2007‐11‐125328. Epub 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rautou PE, Moucari R, Escolano S, Cazals‐Hatem D, Denie C, Chagneau‐Derrode C, et al. Prognostic indices for Budd‐Chiari syndrome: valid for clinical studies but insufficient for individual management. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1140‐1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rautou PE, Angermayr B, Garcia‐Pagan JC, Moucari R, Peck‐Radosavljevic M, Raffa S, et al. Pregnancy in women with known and treated Budd‐Chiari syndrome: maternal and fetal outcomes. J Hepatol Jul 2009;51:47‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cazals‐Hatem D, Vilgrain V, Genin P, Denninger MH, Durand F, Belghiti J, et al. Arterial and portal circulation and parenchymal changes in Budd‐Chiari syndrome: a study in 17 explanted livers. Hepatology 2003;37:510‐519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moucari R, Rautou PE, Cazals‐Hatem D, Geara A, Bureau C, Consigny Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Budd‐Chiari syndrome: characteristics and risk factors. Gut 2008;57:828‐835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]