Watch a video presentation of this article

Watch the interview with the author

Abbreviations

- AGA

The American Gastroenterological Association

- AKI

acute liver injury

- ALF

acute liver failure

- ALFSG

Acute Liver Failure Study Group

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- APACHE II

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- APAP

acetaminophen

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CVVH

continuous veno‐venous hemofiltration

- EBV

Epstein‐Barr virus

- ES

acetaminophen hydrocodone

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- HBP

high blood pressure

- HP

hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IgE

immunoglobulin‐E

- INR

international normalized ratio

- IV

intravenous

- MELD

Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease

- NAC

N‐acetylcysteine

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs

- OTC

over‐the‐counter

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Overview and Epidemiologic Considerations

Acetaminophen (APAP) is a highly effective analgesic and antipyretic agent that is safely used by millions of people every day. However, APAP is also a dose‐dependent hepatotoxin that is present in over 600 marketed products and can cause acute pericentral liver injury when taken in doses exceeding 6 to 10 grams/day (Table 1). APAP overdose is the most common cause of drug‐induced liver injury in the United States, with ≈ 60,000 cases reported each year, and also accounts for nearly 50% of adult acute liver failure (ALF) cases.1 Intentional APAP overdose as a suicide gesture accounts for a majority of these cases, but there has been a significant increase in nonintentional APAP overdose cases over the past 2 decades.2 Overall mortality remains low (< 1%) in intentional APAP overdose patients who receive NAC promptly. However, nearly 50% of the APAP ALF cases are attributed to “therapeutic misadventures”—patients who frequently ingest multiple APAP‐containing products and present with more advanced encephalopathy and liver injury.3 Because there are at least ≈500 deaths each year in the United States attributed to APAP overdose, there are increasing calls for regulatory actions regarding APAP dosing, dispensing, packaging, and coformulation with opioid analgesics.

Table 1.

Acetaminophen Content of Some Commonly Used OTC Products

| OTC Products | Acetaminophen Per Dose (mg) |

|---|---|

| Analgesics/antipyretics | |

| Children's Tylenol products | 80‐160 mg, 160 mg/5 mla |

| Excedrin products | 325‐500 mg |

| Goody's Extra Strength powder products | 250‐500 mg |

| Goody's Headache Relief Shot | 1000 mg/60 mla |

| Midol products | 500 mg |

| Midrin | 325 mg |

| Pamprin products | 250 mg |

| Tylenol Regular Strength | 325 mg |

| Tylenol Extra Strength | 500 mg |

| Tylenol Muscles Aches & Body pains/Arthritis Pain | 650 mg |

| Cold, cough, and sinus products | |

| Alka‐Seltzer products | 325 mg |

| Coricidin HBP Maximum Strength Flu | 500 mg |

| Delsym Cough and Night Time Cold & Cough | 650 mg/20 mla |

| Mucinex Fast‐Max, all tablet/caplet products | 325 mg |

| Mucinex Fast‐Max, all‐liquid products | 650 mg/20 mla |

| Robitussin Daytime Cold and Flu | 325 mg |

| Sudafed PE Pressure and Pain and Cough | 325 mg |

| Tylenol Sinus/Cold, all products | 325 mg |

| Vicks Dayquil/Nyquil, all tablet/caplet products | 325 mg |

| Vicks Dayquil Severe Cold & Flu Liquid | 325 mg/15mla |

| Vicks Nyquil Severe Cold & Flu Liquid | 650 mg/30 mla |

| Sleep aids | |

| Legatrin PM | 500 mg |

| Tylenol PM | 500 mg |

| Unisom PM Pain | 325 mg |

Recommended single dose by manufacturer. The maximum total daily dose of acetaminophen containing products should not exceed 3000 mg (3 grams total). For further information regarding additional OTC products, see http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm165107.htm

Abbreviation: HBP, high blood pressure.

Diagnosis and Clinical Presentation

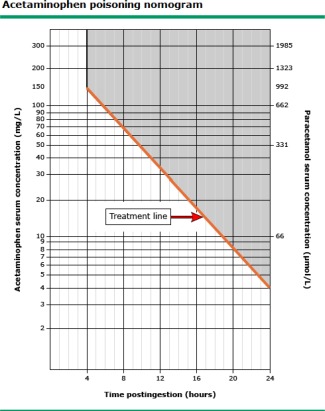

Most patients with APAP overdose have minimal or nonspecific symptoms such as malaise, abdominal pain or nausea, and vomiting at presentation. A detailed medication history can help ascertain total APAP exposure but can be challenging in patients with polydrug overdose or advanced encephalopathy. The Rumack‐Matthew nomogram to predict the likelihood of hepatotoxicity is recommended for initial assessment of all patients with a single time‐point overdose (Fig. 1).4 Although APAP is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, a repeat serum APAP level 4 hours after initial presentation is advisable to better define the risk of liver injury. Of note, the serum APAP level may be low or undetectable in patients who overdose over several days, and NAC should not be delayed whenever there is any clinical suspicion of APAP overdose. Serum acetaminophen‐protein adducts are covalent adducts of APAP with a much longer half‐life than the parent compound, which can be a helpful diagnostic tool in ambiguous cases, but this assay is not commercially available.5

Figure 1.

Modified Rumack‐Matthew nomogram in APAP overdose. The modified Rumack‐Matthew nomogram should only be used in patients with one time‐point APAP ingestion. Subjects with a serum APAP level above the line are at risk for developing hepatotoxicity and should be hospitalized and given NAC for a minimum of 24 hours. The serum APAP level should be plotted in relationship to the estimated time of oral ingestion and should be repeated 4 hours after presentation in subjects with an unreliable history. The nomogram should not be used in ingestions that occurred > 24 hours prior to presentation or in patients who have overdosed over several days. This figure has been adapted from N Engl J Med.4

Serum aminotransferase levels are frequently normal shortly after intentional APAP overdose but may rapidly increase during the first 24 hours of hospitalization. Some subjects may present with an isolated metabolic or lactic acidosis with or without acute kidney injury or an elevation in their international normalized ratio (INR) (Table 2). All patients with elevated serum aminotransferase levels should be evaluated for other etiologies of acute liver injury (ie hepatitis A, B, C; ischemia; pancreaticobiliary disease), as well as ingestion of other illicit substances (Table 2). A rapid assessment of the severity of liver injury is performed by a combination of clinical (grade of encephalopathy) and laboratory (liver chemistries, creatinine, INR, arterial PH, arterial lactate, and factor V assay) parameters. An early assessment of disease severity can help determine the appropriate level of care for a given patient (ie general floor vs intensive care unit [ICU]). A psychiatric and social work evaluation of all patients with intentional APAP overdose should be initiated in parallel with their NAC treatment to maximize patient safety and avoidance of further harm.

Table 2.

Clinical Features of APAP Overdose

| Detailed history | Review all prescription and OTC medications. |

| Total dose ingested > 4 grams | |

| Risk factors: fasting, alcohol use, concomitant medications, polypharmacy, opioid congeners | |

| Usually > 10 grams in 24 hours | |

| Single timepoint ingestion: Use Rumack‐Matthew nomogram at presentation and 4 hours later | |

| Staggered/nonintentional overdose: Serum APAP levels may be low or undetectable. Give NAC whenever APAP overdose suspected. | |

| Evaluation of other causes of acute hepatocellular liver injury | Hepatitis A, B, C; CMV; EBV |

| Pancreaticobiliary disease, vascular thrombosis, pancreatitis, ischemia | |

| Others etiologies based on risk factors | |

| Establish diagnosis | Serum APAP level |

| Urine toxicology screen | |

| Blood alcohol level | |

| Hep A IgM, HBsAg, anti‐HBc, HCV‐RNA | |

| Liver ultrasound with Doppler | |

| Severity assessment | Serum AST, ALT, total bilirubin (most have normal bilirubin at presentation) |

| Peak ALT not seen till 48‐72 hours | |

| INR | |

| Serum creatinine, bicarbonate, phosphate level | |

| 50% of ALF patients develop AKI | |

| Arterial pH and lactate | |

| Factor 5 level | |

| Encephalopathy assessment (Grade 0‐4) | |

| ICU care, if any of these features present | Encephalopathy grade 1 or higher |

| Renal failure | |

| Metabolic acidosis | |

| Hypotension | |

| Transfer to liver transplant center if | Encephalopathy grade 2 or higher |

| Intubated, pressors, hemodialysis |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein‐Barr virus.

Standard Treatment

All patients who present within 4 hours of APAP overdose should receive ipecac syrup to induce vomiting—or nasogastric lavage to remove pill fragments, followed by activated charcoal to reduce APAP absorption. NAC, which repletes the intrahepatic glutathione stores, also should be administered promptly via oral or intravenous (IV) route based on the patient's clinical condition.4 Of note, NAC is a pungent sulfa drug that can cause significant nausea and vomiting in 20% to 30% of patients, and IV NAC can lead to rash and a non‐IgE–mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Recently, a randomized trial has shown better tolerance and fewer side effects with a 12‐hour IV regimen of NAC versus the standard 20‐hour IV regimen, but confirmatory studies are needed6 (Table 3). The incidence of hepatotoxicity is < 10% in those receiving NAC within 8 hours of ingestion but increases to 40% if NAC is delayed > 16 hours.

Table 3.

Treatment and Management of APAP Overdose

| Initial Measures on Presentation |

|---|

| Within 4 hours of ingestion |

| Ipecac syrup, 15 ml once; repeat in 20 minutes if needed |

| Nasogastric lavage of pill fragments |

| Activated charcoal, 1 g/kg body weight (maximum dose 50 grams) |

| Within 16 hours of Ingestion |

| NAC, oral or intravenous |

| Oral loading: 140 mg/kg followed by 70 mg/kg every 4 hours for 17 doses or until INR < 1.5 |

| nausea and vomiting in 20%, mix with carbonated beverages to improve tolerance; prochlorperazine (Compazine) 10 mg, metoclopramide (Reglan) 10 mg, or ondansetron (Zofran) 4 mg by mouth or IV; consider IV NAC if refractory nausea and vomiting |

| Intravenous loading: 150 mg/kg in 250 ml dextrose 5% over 1 hour, then 50 mg/kg in 500 ml dextrose 5% over 4 hours; then 125 mg/kg in 1000 ml dextrose 5% over 19 hours; 100 mg/kg in 1000 ml dextrose 5% over 24 hours for 2 days or until INR is less than 1.5. Contraindicated in sulfa allergy. |

| IV NAC requires telemetry monitoring for arryhythmias and hypotension. Anaphylactoid reactions with urticaria or wheezing should have the infusion stopped and receive IM epinephrine, IV diphenhydramine, corticosteroids and albuterol. Resumption of infusion only in a monitored setting and consultation with local poison control center. If hypotension or angioedema, give fluids, steroids, and epinephrine and do not resume IV NAC (consider oral NAC with careful monitoring) |

| Minimum duration of NAC administration is 24 hours if no signs of liver injury or renal failure at 24 hours and 72 hours if evidence of liver injury. |

| IV NAC is generally preferred in pregnant women to maximize drug levels to fetus and also for individuals with short gut or ileus. |

| General Supportive Measures |

| Quiet and comfortable environment |

| Nutritional support |

| Monitoring of laboratory measures (every 12 hours) |

| Blood glucose monitoring every hour |

| Intravenous fluids if hypotension |

| Frequent screening for infection, low threshold for starting antimicrobial agents |

| Avoid correction of coagulopathy except for active bleeding or invasive procedures |

| Avoid nephrotoxic agents (NSAIDs, aminoglycosides) |

| Frequent monitoring of neurological status |

| Intensive Care |

| Urgent liver transplant evaluation |

| Encephalopathy grade I or II |

| Computed tomography of head to evaluate bleeding/cerebral edema |

| Avoid sedation; propofol and midazolam preferred for severe agitation |

| Keep head of bed > 30 degrees to avoid intracranial hypertension |

| Encephalopathy grade III or IV |

| Avoid fever; goal temperature ∼ 36°C |

| Intubation and mechanical ventilation |

| Vasopressor support if persistent hypotension despite IV fluids |

| Renal support: CVVH preferred over hemodialysis |

| Invasive monitoring of intracranial pressure, treat with hyperventilation, mannitol or hypertonic saline; barbiturate coma for refractory cases |

Abbreviations: CVVH, continuous veno‐venous hemofiltration; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs.

The goal of supportive care is to provide the optimal environment for hepatic recovery, vital organ support, and prevention and treatment of complications. General supportive measures include volume resuscitation and vasopressor support, monitoring for bleeding complications, monitoring and treatment of infections, respiratory support, avoidance of nephrotoxins, and renal support as needed.7 Monitoring and treatment of hypoglycemia and hypophosphatemia are also important. Therefore, liver chemistries, renal function, INR, acid base status, and factor V should be checked every 12 hours. Subjects with no evidence of liver injury, coagulopathy, or kidney injury at 24 hours after presentation may have NAC discontinued and be treated supportively. In contrast, patients with evidence of early liver injury should receive a full 72 hours of NAC therapy, and those with poor prognostic indicators should be identified for early liver transplantation (LT) evaluation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prognostic Scoring Systems Used to Identify Patients at High Risk of Mortality Without Liver Transplantation Due to APAP‐Related ALF

| Scoring System | Key Components | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| King's College criteria | Arterial pH < 7.30 | 55% | 93% |

| or | |||

| Prothrombin time > 100 plus | 58% | 95% | |

| Encephalopathy grade > 2 plus | |||

| Serum creatinine > 3.4 mg/dl | |||

| Arterial lactate | 3.5 mmol/l on presentation | 81% | 72% |

| or | |||

| > 3 mmol/l after fluid resuscitation | 81% | 77% | |

| Modified King's College criteria | King College criteria plus arterial lactate > 3 mmol/l following resuscitation | 91% | 71% |

| APACHE II | Score > 15 at 24‐hour postadmission | 79% | 97% |

| SOFA score | Score > 8 at admission | 67% | 66% |

| MELD score | MELD > 30 | 97% | 68% |

| ALFSG index | Coma grade, bilirubin, INR, serum phosphate, M‐30 (serum marker of apoptosis) | 86% | 65% |

| Routinely used indicators of poor prognosis | Arterial pH < 7.3 | Presence of 2 or more factors associated with poor transplant‐free survival | |

| Arterial lactate > 3 mmol/l following resuscitation | |||

| Encephalopathy grade III or IV | |||

| Factor V ratio < 20% | |||

Sensitivities and specificities stated for transplant‐free survival.

Abbreviations: ALFSG, Acute Liver Failure Study Group; MELD, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Prognosis and Outcomes

Transplant‐free survival from APAP‐related ALF is significantly higher (70%) compared to ALF from idiosyncratic drug reactions (< 25%) or other causes of ALF (0%‐50%).8 Multiple prognostic scoring systems have been evaluated to identify the patients at increased risk of death without LT from APAP ALF (Table 3).9 The King's College criteria with or without arterial lactate levels are the most commonly used criteria to list patients for LT. In a large multicenter prospective study of 275 APAP ALF patients, 178 (65%) patients survived without LT, 23 (8%) patients underwent LT, and 74 (27%) patients died.3 The Apache II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score yielded higher sensitivity but slightly lower specificity than King's College criteria. One‐year survival after LT for APAP ALF is ≈73%.10 For APAP hepatotoxicity patients not requiring LT, the mean length of stay for intentional overdose patients is 4 days, and for nonintentional overdose patients it is 9 days.

Prevention of Acetaminophen Overdose

Several steps have been taken by regulatory authorities to change the labeling and dispensing of the hundreds of prescription and over‐the‐counter (OTC) products containing APAP (Table 5). In 1998, the United Kingdom limited the sale of OTC APAP to 8 grams and required blister packaging of APAP products. This resulted in significant decrease in the APAP overdose cases, number of admissions to liver units, and number of liver transplants due to APAP overdose.11 In 2006, the FDA enacted changes in the labeling of all OTC products that contain APAP to include extra warnings. More recently, the FDA has limited the dose of APAP in prescription combination products to a maximum of 325 mg per tablet and also included black‐box warnings on these products regarding their APAP content. In addition to regulatory actions, patient education by health care providers is extremely important. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has launched an innovative campaign comprising of a short online video (http: //gutcheck.gastro.org) and other education materials to help raise awareness among patients regarding OTC and prescription medications containing APAP. However, a recent prospective study has demonstrated the limitations of written and even verbal instructions to patients regarding the potential for inadvertent APAP toxicity when using multiple products.12

Table 5.

Regulatory and Educational Measures Undertaken to Reduce the Incidence of APAP Overdose

| United Kingdom legislation, 1998 | Acetaminophen sale in blister pack only | |||

| Maximum tablets in OTC packets restricted to 16 (500‐mg strength) | ||||

| Maximum tablets issued by pharmacist restricted to 32 (500‐mg strength) | ||||

| FDA, 2006 | Labeling changes on all APAP containing OTC products | |||

| Black‐box “liver warning” | ||||

| Increase font size and highlighting of the ingredient name “acetaminophen.” | ||||

| Warning for patients with liver disease and those that consume 2‐3 alcoholic beverages/day to consult a doctor before using the product | ||||

| FDA, 2014 | Prescription APAP combination products limited to no more than 325 mg acetaminophen per dosage unit | |||

| Combination product labels to include black‐box warning regarding APAP content and potential for hepatotoxicity | ||||

| OTC products still allowed to contain > 325 mg/dose, and many have 500‐650 mg/dose (see Table 1) | ||||

| Discontinued | New Formulations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand | Generic | Brand | Generic | |

| Lortab Elixir | Hydrocodone‐acetaminophen 2.5‐500 mg/5 ml oral solution 7.5‐500 mg/5 ml oral solution | NAHycet | Hydrocodone‐acetaminophen 2.5‐108 mg/5 ml oral solution 7.5‐325 mg/15 ml oral solution | |

| Lortab | Hydrocodone‐acetaminophen 7.5‐500 mg tablet | NorcoVicodin‐ES | Hydrocodone‐acetaminophen 7.5‐325 mg tablet7.5‐300 mg tablet | |

| Lortab | Hydrocodone‐acetaminophen 10‐500 mg tablet | NorcoVicodin‐HP | Hydrocodone‐acetaminophen 10‐325 mg tablet10‐300 mg tablet | |

| Percocet | Oxycodone‐acetaminophen 7.5‐500 mg tablet | Percocet | Oxycodone‐acetaminophen 7.5‐325 mg tablet | |

| Percocet | Oxycodone‐acetaminophen 10‐650 mg tablet | Percocet | Oxycodone‐acetaminophen 10‐325 mg tablet | |

| Phrenilin Forte | Butalbital‐acetaminophen 50‐650 mg capsule | Phrenilin | Butalbital‐acetaminophen 50‐325 mg capsule | |

| AGA Medicine Safety Campaign, 2013 | Emphasis on patient education regarding the safety of OTC pain medications. | |||

| A short online video at http://gutcheck.gastro.org | ||||

| An infographic available online and for use in doctor's offices. | ||||

| Other educational materials for patients. | ||||

Abbreviations: ES, acetaminophen hydrocodone; HP, hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Nourjah P, Ahmad SR, Karwoski C, Willy M. Estimates of acetaminophen (Paracetomal)‐associated overdoses in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15(6):398‐405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Myers RP1, Li B, Fong A, Shaheen AA, Quan H. Hospitalizations for acetaminophen overdose: a Canadian population‐based study from 1995 to 2004. BMC Public Health 2007;7:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, et al. Acetaminophen‐induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology 2005;42(6):1364‐1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smilkstein MJ, Knapp GL, Kulig KW, Rumack BH. Efficacy of oral N‐acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1557‐1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davern TJ, James LP, Hinson JA, et al. Measurement of serum acetaminophen–protein adducts in patients with acute liver failure. Gastroenterology 2006;130:687‐694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bateman DN, Dear JW, Thanacoody HK, et al. Reduction of adverse effects from intravenous acetylcysteine treatment for paracetamol poisoning: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383(9918):697‐704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stravitz RT, Kramer AH, Davern T, et al. Intensive care of patients with acute liver failure: recommendations of the U.S. acute liver failure study group. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2498‐508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2002;137(12):947‐954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Craig DG, Ford AC, Hayes PC, Simpson KJ. Systematic review: prognostic tests of paracetamol‐induced acute liver failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31(10):1064‐1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bernal W, Wendon J, Rela M, et al. Use and outcome of liver transplantation in acetaminophen‐induced acute liver failure. Hepatology 1998;27:1050‐1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hawton K1, Simkin S, Deeks J, et al. UK legislation on analgesic packs: before and after study of long term effect on poisonings. BMJ 2004;329(7474):1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Serper M, et al. Effect of enhanced risk communication on patient comprehension of concomitant use warnings for APAP‐ containing products: A randomized Trial (Abstract). Hepatology 2013;58;1722. [Google Scholar]