Abstract

Black gay/bisexual male youth are one of the groups most affected by HIV in the U.S., but few behavioral interventions have been created specifically to address this health inequity. Oppression related to these youths’ multiple social identities – including racism, heterosexism, and HIV stigma – contribute to increased health risks. Primary and secondary HIV prevention interventions created specifically for Black gay/bisexual male youth that address the negative impact of oppression are urgently needed. We present empowerment as a framework for understanding how oppression affects health, and critical consciousness as a tool to be utilized in behavioral interventions. This approach helps to move Black gay/bisexual male youth from a place of oppression and powerlessness that leads to elevated health risks to a position of empowerment that promotes feelings of control and participation in healthy behaviors. Finally, we present a case example of our own critical consciousness-based secondary HIV prevention intervention created specifically for Black gay/bisexual male youth.

Keywords: critical consciousness, Black, gay, HIV prevention, empowerment

Though Black gay/bisexual male adolescents and emerging adults are one of the groups most affected by HIV in the U.S., few behaviorally-focused prevention interventions have been created specifically for this population (Harper & Riplinger, 2013). Much research has shown the detrimental health effects of various types of oppression (e.g., racism, heterosexism, HIV stigma) that pervade the lives of these young men within the U.S. (Arnold, Rebchook & Kegeles, 2014; Bogart, Wagner, Galvan et al., 2011; Bogart, Landrine, Galvan, et al., 2013; Wade & Harper, 2017). As such, we document the utility of using empowerment as a framework for understanding how oppression impacts the health and wellbeing of Black gay/bisexual male youth, and offer critical consciousness as an effective method of operationalizing empowerment in behavioral interventions for this population. Since our goal is to support the inclusion of critical consciousness strategies into both primary and secondary HIV prevention interventions, we discuss data and literature that addresses both Black gay/bisexual male youth living with HIV and those who are not living with HIV.

HIV Prevention Interventions for Black Gay and Bisexual Male Youth

Black gay/bisexual adolescents and emerging adults are disproportionately affected by HIV in the U.S. and represent one of the largest sub-groups of people living with HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2015). HIV cases among youth aged 12–24 years in the U.S. have more than doubled in the last 15 years, and now constitute 22% of the epidemic (CDC, 2016, 2017a, 2017b). The youth epidemic is particularly concentrated among gay and bisexual male youth, who comprise more than 81% of all new infections and 55% of newly diagnosed males are Black (CDC, 2016). In the U.S., the risk of acquiring HIV is highest among Black gay/bisexual men, with estimates that half of all Black men who have sex with men will acquire HIV in their lifetime (Hess, Hu, Lansky, Mermin & Hall, 2017).

These data demonstrate that HIV is a public health crisis among Black gay/bisexual male youth. Without culturally grounded HIV prevention interventions developed specifically for this population, higher numbers of these young men will become infected. These data also suggest that, in addition to primary prevention interventions, secondary prevention interventions are desperately needed for Black gay/bisexual male youth living with HIV to both improve their health and decrease the likelihood that they will pass the virus on to others.

Gay and bisexual male adolescents typically do not receive sexuality education in schools that addresses same-gender sexuality, with a recent study also showing that they were less likely than their heterosexual male youth counterparts to be taught about HIV (Rasberry, Condron, Lesesne, Adkins, Sheremenko, & Kroupa, 2018). A review of sexual health promotion and HIV prevention interventions specifically for adolescents between 1991 and 2010 revealed that only 5% of peer-reviewed articles on evidence-based behavioral interventions were focused on gay/bisexual male adolescents, with none exclusively for Black male youth (Harper & Riplinger, 2013). In addition, the vast majority of these interventions utilized information and cognitive-behavioral approaches to HIV prevention, with none encouraging critical approaches to sexual health promotion.

A more recent qualitative systematic review focused on behavioral HIV prevention interventions for young gay and bisexual men (ages 13–24), and found 15 interventions published in the peer-reviewed literature that produced statistically significant findings (Hergenrather, Emmanual, Durant, & Rhodes, 2016). Only two of these interventions were specifically focused on Black gay/bisexual male youth—Hightow-Weidman et al.’s (2012) HelathMpowerment.org interactive internet based intervention and Hosek et al.’s (2015) POSSE community-level popular opinion leader intervention for Black youth involved in the House and Ball Community. Although some of the interventions reported incorporating aspects of empowerment into their intervention, this concept was differentially defined and none of the interventions specifically addressed the health impacts of oppression on Black gay/bisexual young men.

Interventions specifically targeting Black gay/bisexual male youth are needed because existing interventions do not focus on the multitude of factors that promote heightened risk in this population, or the unique resilience processes demonstrated by these youth men (Harper, Tyler, Bruce et al., 2016; Wade & Harper, 2017; Wilson & Moore, 2009). The popularity of biomedical interventions to prevent HIV such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) has decreased the focus on behavioral interventions, but unfortunately, these prevention methods are not well utilized among youth at highest risk for HIV. Black gay/bisexual adults and youth are least aware of and least likely to use PrEP (Eaton, Driffin, Bauermeister, Smith, & Conway-Washington, 2015; Strauss, Greene, Phillips et al., 2017). Even though PrEP has demonstrated acceptability among gay/bisexual male youth (Hosek, Rudy, Landovitz et al., 2017), PrEP utilization is only 8% - 9% (Hosek et al., 2017, Strauss et al., 2017). Thus, culturally grounded sexual health promotion and HIV prevention interventions (both primary and secondary) that address the impact of oppression on the health and wellbeing of Black gay and bisexual male youth are needed.

Multiple Layers of Oppression

Black gay/bisexual male adolescents and emerging adults experience multiple layers of powerlessness and oppression due to their age, race, and sexual orientation (Frye, Nandi, Egan et al., 2015; Harper & Wilson, 2016; Wilson & Harper, 2013). Frequently, ethnic minority gay/bisexual youth must not only contend with negative societal reactions to their sexual orientation, but also may experience racial prejudice, limited economic opportunities and resources, and limited acceptance within their own ethnic cultural community (Harper & Wilson, 2016; Hightow-Weidman, Phillips, Jones, Outlaw, Fields, Smith, & YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group, 2011). Unfortunately, ethnic minority gay/bisexual youth also may experience racial prejudice, marginalization, and sexual objectification within the larger predominately White mainstream gay community (Harper, 2007; Wilson & Harper, 2013). Black gay/bisexual male youth who are HIV-positive occupy an additional stigmatized identity, experiencing HIV stigma as an added layer of oppression (Arnold et al., 2014; Dowshen, Binns, & Garofalo, 2009). A recent review of peer-reviewed literature (n=125 studies) regarding the health and wellbeing of sexual minority youth of color found that few articles intentionally examined how intersecting oppressions and privileges related to sexual orientation and race-ethnicity contributed to their outcomes of interest (Toomey, Huynh, Jones, Lee, & Revels-Macalinao, 2017).

It is important to recognize the discrimination and stigmatization experienced by Black gay/bisexual male youth with regard to sexuality, race, and HIV status as social processes that can be understood as oppression by dominant groups in order to maintain power and privilege (Parker & Aggleton, 2003). We adhere to a definition of oppression that is grounded in the concept of asymmetry or the unequal distribution of coveted resources among socially salient groups (Watts, Griffith, & Abdul-Adil, 1999; Watts, Williams, & Jagers, 2003), a core concept of oppression that is shared by other oppression theorists (cf. Serrano-Garcia, 1984; Serrano-Garcia & Lopez-Sanchez, 1992; Prilleltensky, 2003; Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2002). Oppression can be propagated through more direct or overt mechanisms of denial, exclusion, control and/or restriction (e.g., denial of rights, control of resources, restriction of mobility), as well as by more indirect or subtle ideological systems of influence (e.g., institutionalized racism, heterosexism, sexism, classism and their related practices) (Watts et al., 2003).

These oppressive forces are experienced at multiple socioecological levels, including the personal, interpersonal/relational, and social/community. Many members of privileged groups are not aware of the heterosexist and racist nature of most societies, since heterosexist/racist language, icons, images and messages are so pervasive within the various realms of our existence (Harper, 2010; Herek, 2015). Complex interconnected political, social, and cultural forces create hegemony within a society, legitimizing the structures of social inequities (Bowleg, 2017). Though members of marginalized groups are often aware of the heterosexist/racist nature of most societies, they are often led to accept and even internalize the stigma to which they are subjected (Parker & Aggleton, 2003).

We propose that oppression and resulting feelings of powerlessness drive the HIV epidemic among Black gay/bisexual male youth in several key ways. Multiple layers of powerlessness can negatively impact these youth’s self-concept, future life options, sense of social connectedness, and intimacy needs—all potentially increasing participation in risky sex (Harper, 2010; Miller 2007). Recognition of the role of powerlessness in HIV risk behaviors among Black gay/bisexual men is not new. Early qualitative research studies examining increased HIV risk among Black gay/bisexual men first documented how the men’s negative experiences related to race, sexuality, and gender lead to the self-concept issues that many of these men contend with, as well as the way these issues can affect risk and health-seeking behaviors (Beeker, Guenther-Grey, & Raj, 1998; Stokes & Peterson, 1998).

In examining the facilitators and barriers to HIV prevention faced by health departments and community-based organizations working with this population, Wilson and Moore (2009) found that many of the barriers to prevention were related psychosocial problems including poor or low self-esteem and self-worth. As in other studies, this was related to deep-seated external and internalized stigma around sexuality, race, and gender. Participants suggested that interventions aimed at improving self-concept were needed to respond to HIV among Black gay/bisexual men. One provider highlighted where current interventions may be missing the mark, providing direction for future interventions: “so basically, in terms of HIV for Black gay men, it’s not – and this is the punch line – it’s not a question of them not knowing how to save their lives. It’s a question of them knowing if their lives are worth saving,” (Wilson & Moore, 2009, p.1017).

Black gay/bisexual male youth who are living with HIV must contend with an additional stigmatized identity. HIV-related stigma has been shown to influence the quality of life and adherence to care of adolescents and young adults living with HIV (Harper et al., 2013; Harper, Lemos, Hosek, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions [ATN], 2014; Martinez et al., 2012). The perception and internalization of HIV-related stigma, coupled with the lack of supportive social relationships, can lead to increased substance use, decreased general psychological health, and decreased engagement in the HIV care contiuum (Bruce, Harper, & the ATN, 2011; MacDonell, Naar-King, Murphy, Parsons, & Harper, 2010; Nugent et al., 2010). The stigma associated with HIV also has been shown to be associated with specific psychological challenges for young people living with HIV in the form of increased symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as decreased self-esteem (Andrinopoulos et al., 2011; Brown, Whiteley, Harper, Nichols, Nieves, & ATN, 2015; Varni, Miller, McCuin, & Solomon, 2012). Such psychological distress, in turn, has been associated with decreased adherence to antiretroviral therapies (Hosek, Harper, & Domanico, 2005; MacDonell, Naar-King, Huszti, & Belzer, 2013) among adolescents living with HIV.

Black gay/bisexual male youth who acquire HIV have, on average, lower rates of engagement in the HIV care continuum as compared to their Latino and White counterparts (Hightow-Weidman, Jones, Wohl, Futterman, Outlaw, Phillips, Hidalgo, Giordano, & YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group, 2011; Hussen, Harper, Bauermeister, Hightow-Weidman, & ATN, 2015; Johnson et al., 2013). Here again the influence of oppression can be seen. First, on an intrapersonal level, the same low self-worth issues discussed above that may cause Black gay/bisexual male youth to engage in high-risk sexual behavior may also cause Black gay/bisexual male youth living with HIV to avoid engaging in care. These young men may not seek care because of internalized stigma related to sexuality, race, and HIV. Harper et al. (2013) found that, among a predominantly ethnic/racial minority sample of 200 gay/bisexual young men living with HIV, lower levels of ethnic identity affirmation, higher levels of negative attitudes toward same-sex sexual activity and behavior, and higher levels of HIV-positive identity salience were associated with significantly greater risk for missed appointments in the past 3 months.

Second, on an interpersonal level, Black gay/bisexual male youth may also avoid engagement in the HIV care continuum in order to hide their HIV status out of fear of the external stigma they would encounter from family, friends, employers, and other community members if their HIV status was known (Arnold et al., 2014; Radcliffe, Doty, Hawkins, Gaskins, Beidas, & Rudy, 2010). Furthermore, for some male youth, receiving an HIV diagnosis may lead them to struggle with not only accepting their medical diagnosis but also accepting their gay or bisexual sexual orientation. They may also fear that disclosure of their HIV status to family and friends may be a disclosure of their sexual orientation (Zea, Reisen, Poppen, Bianchi, & Echeverry, 2007). In addition, youth who have a negative attitude toward their sexuality may feel less comfortable seeking medical care in a clinic where they may have contact with other gay/bisexual youth—thus restricting them from receiving the social support benefits of interacting with other youth who are living with HIV (Hosek, Harper, Lemos, & Martinez, 2008; Lam, Naar-King, & Wright, 2007; Macdonell et al. 2010). Lacking the psychological resources to address these dual issues, some youth may avoid the medical care system as a way to cope.

Finally, Black gay/bisexual male adolescents experience institutional- and structural-level oppression. Prevalence of reported racial discrimination by Black individuals in healthcare settings is relatively high, ranging from 6.9% - 52% (Shavers et al., 2012). Adult Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men are less likely than others to report satisfaction with medical providers, to report an absence of nondiscriminatory practices among medical staff, and to trust the quality and competence of outpatient medical services (Malebranche, Peterson, Fullilove, & Stackhouse, 2004). Within HIV epicenters, AIDS-related mortality rates are higher within majority Black neighborhoods than majority White neighborhoods with similar prevalence rates (Nun et al., 2014). These and other forms of structural-level racism supports findings by Kahana et al. (2016) that youth living in more disadvantaged areas were less likely to report current ART use.

Empowerment Theory Provides a Theoretical Framework for Understanding How Oppression and Empowerment Impact Health

Even though research indicates that Black gay/bisexual male youth contend with multiple threats to their self-esteem that are linked to their social and cultural identities (Harper, 2007; Jamil, Harper, Fernandez, & ATN, 2009; Malebranche, Fields, Bryant, & Harper, 2009; Millett et al., 2007), poor self-concept, decreased self-esteem and self-efficacy, and psychological distress remain largely unaddressed in interventions targeting Black gay/bisexual men. It has been proposed that before engaging in traditional behavioral interventions aimed at increasing health promotion behaviors, it is essential for Black men to first be exposed to interventions that promote positive self-concept and increase self-esteem and awareness of social, political, and structural factors that may thwart positive development (Watts et al., 1999). For these reasons, empowerment provides a useful theoretical framework for interventions with Black gay/bisexual male youth.

The theory of empowerment consists of a number of definitions of the construct, as well as complex models of empowerment for individuals, organizations, and communities. Rappaport (1987), who is credited with first introducing the concept of empowerment into psychology and related fields, defined empowerment as “a mechanism by which people, organizations, and communities gain mastery over their affairs” (p. 122). Zimmerman’s (1995) model of psychological empowerment has become one of the most widely used models for studying empowerment at the individual level. The model puts forward three dimensions of psychological empowerment: intrapersonal, interactional and behavioral. The intrapersonal dimension refers to a sense of control that one has over important resources for one’s well-being, and it is frequently measured as sense of mastery, various forms of self-efficacy, or locus of control. The interactional dimension refers to a critical awareness of the social and political environment and how resources are distributed in the environment. The behavioral dimension refers to behaviors that individuals enact based on their critical awareness and sense of control.

Some aspects of psychological empowerment are closely linked to the Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986) constructs of self-control of behavior and self-efficacy. Sense of agency and control, have been identified as key constructs in the process of adolescents and young adults moving toward improved critical consciousness in prior interventions (Dunlap et al., 2017; Watts et al., 2002; Wallerstein & Sanchez-Merki, 1994). These key constructs, in combination with critical reflection and empowerment, are understood as mediating mechanisms between intervention exposure and engagement in health promotion behaviors (Super, Wagemakers, Picavet, Verkooijen, & Koelen, 2015). Intervention activities that are grounded in Social Cognitive Theory typically aim to increase participants’ behavioral capability by promoting mastery learning through skills training, thus improving participants’ perceived self-control. Such activities typically facilitate improved self-efficacy by increasing participants’ confidence that they will be able to perform protective behaviors and remove barriers to performing health promoting activities.

The framework of psychological empowerment has been applied to populations who experience varying degrees of oppression and marginalization (Taghipour, Sadat, Latifnejad et al., 2016; Zimmerman, Eisman, Reischl et al., 2018). Feelings of powerlessness, or lack of control over one’s destiny, emerge as a broad-based risk factor for negative health outcomes, whereas empowerment has been demonstrated as an important promoter of health (Eisman, Zimmerman, Kruger et al., 2016; Super et al., 2015). The process of becoming empowered involves gaining greater internal control or capacity and overcoming external structural barriers to accessing health-promoting resources (Speer & Hughey, 1995, Super et al., 2015). The promotion of empowerment has been the basis for both primary and secondary HIV prevention programs for a range of adolescent and adult populations who experience oppression related to their gender, sexual orientation, and/or race/ethnicity (cf. Hahm et al., 2017; Harrison, Hoffman, Mantell et al., 2016; Hosek, Lemos, Harper, & Telander, 2011; Li et al 2018).

With the success of empowerment interventions in improving the health and well-being of adolescents and young adults, some authors have recommended an expansion of empowerment-related constructs or methods used in these programs. Mohajer and Earnest (2009) conducted a global literature review of empowerment-based and empowerment-focused programs and interventions for vulnerable or marginalized adolescents, including a total of 910 articles, books, documents and theses. They asserted that despite evidence of such programs’ success in bringing about behavior change, the focus on individual empowerment in program implementation has missed “the critical focal point of empowerment,” (Mojajer & Earnest, 2009). Authors suggest that the true essence of empowerment includes an emphasis on social change, its multi-dimensional attributes, and its potential to address the social determinants of health—all of which are essential to improving the health of oppressed and marginalized adolescents (Mohajer & Earnest, 2009).

Spencer (2014) proposes a new dynamic and generative conceptualization of empowerment for youth health promotion that synthesizes individual, structural, and ideological elements of power and is based on two interrelated understandings of health—dominant and alternative. The current conceptualization of how empowerment interventions produce changes in health – through a linear process, whereby individual empowerment leads to avenues and opportunities for more community-empowerment through collective consciousness and critical action – is cautioned against by Spencer (2014) because it omits a critical discussion of power. She warns that such a conceptualization fails to recognize the ways in which power shapes social structures and contexts in which health behaviors occur and suggests that health promotion frameworks for youth need to engage with youths’ lived experiences even though they may challenge dominant perspectives on health (Spencer, 2014). The framework for empowerment interventions put forth by Spencer underscores the importance of interventions involving transformative forms of empowerment that allow youth to interrogate and challenge dominant systems of meaning and create new and affirming conceptualizations of health and well-being. Such interventions would thus involve critical analyses of dominant ideologies regarding youth and their identities, as well as their health-related behaviors.

Critical Consciousness as a Tool for Empowerment Interventions

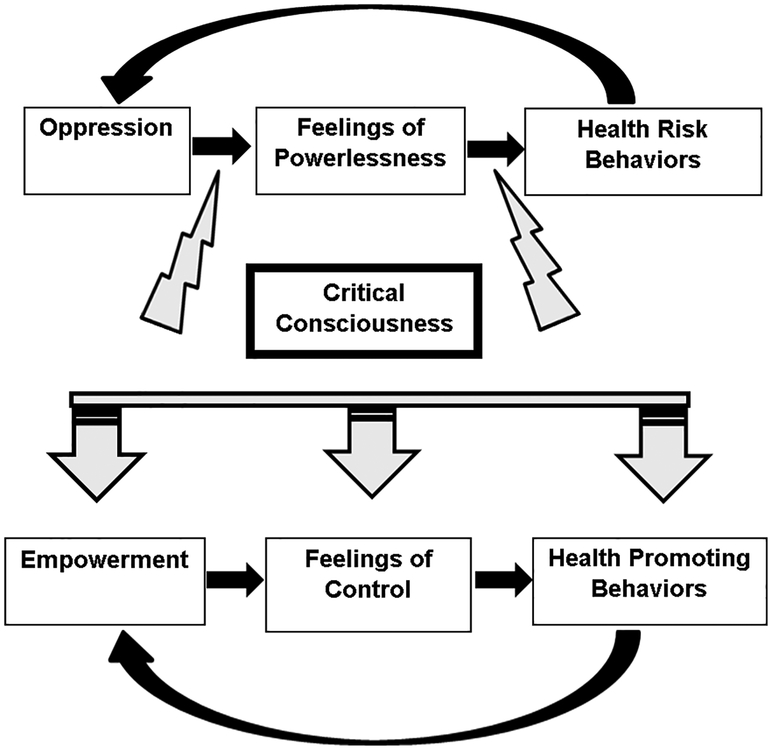

While empowerment theory provides a framework for understanding how oppression and empowerment impact health, critical consciousness provides the tools for moving individuals from oppression and resulting powerlessness and engagement in health risk behaviors to empowerment and resulting feelings of control and participation health promoting behaviors. We present the “Pathway to Health” figure to demonstrate the potential of critical consciousness interventions to disrupt the cycle of oppression-feelings of powerlessness-health risk behaviors, and to move participants to a cycle of empowerment-feelings of control-health promoting behaviors. The following will further support our recommendation to use critical consciousness as an effective method of operationalizing empowerment in behavioral interventions for Black gay/bisexual male youth.

Defining the Process of Critical Consciousness

Critical consciousness emerged out of the seminal work of Brazilian educator and activist, Paulo Freire (1973, 1990, 2000), who created the concept of “conscientization” to represent the multi-stage process of developing a critical awareness of societal, historical, political, and cultural forces which serve to oppress particular groups of people, and learning how to disrupt these oppressive forces through resistance and social change efforts. Freire (1973, 1990, 2000) describes a liberatory pedagogy for enhancing critical consciousness and asserts that this transformative process can help individuals and groups resist the negative effects of oppression and move into a state of liberation and well-being. Watts and Serrano-Garcia (2003) stress that this resistance to oppression does not occur without some type of action or intervention, and that the process is often challenging. The difficulty in this process of conscientization or critical consciousness may be related to the need to deconstruct the cultural and ideological foundations of oppression (Watts & Serrano-Garcia, 2003), which requires a critical analysis of dominant ideologies and societal assumptions that are pervasive and endemic within all realms of one’s existence. Critical consciousness then requires an active and intentional process of challenging these assumptions and presuppositions and exploring avenues for resisting oppression. Unfortunately, pervasive and long-standing oppressive and dominant ideologies and hegemonic beliefs can lead to an internalization of a stigmatized and subordinate status (Parker & Aggleton, 2003), thus decreasing the likelihood of spontaneous resistance to oppression.

As critical consciousness is enhanced and developed, individuals and groups become more aware of the power differentials and multiple points of asymmetry that exist in society (Watts et al., 1999) and move toward acts of resistance and liberation, both of which promote health and well-being (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010; Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2002). Critical consciousness is a process that takes time and taps into multiple aspects of one’s awareness (Watts et al., 2003). Through this process of critical consciousness, individuals and groups are able to redefine themselves and their realities in a more positive, health promoting, and affirming manner that is based on their own perspectives and realities as opposed to those assigned to them by others. This process of gaining critical consciousness and an understanding of one’s sociopolitical environment, coupled with active engagement in one’s community and heightened sense of competence, are critical aspects of psychological empowerment (Zimmerman, 2000).

Use of Critical Consciousness with Youth.

Enhancing critical consciousness among youth has been identified as an avenue for promoting physical and mental health by assisting young people with understanding and challenging negative social influences such as sexism, racism, and other social injustices that can lead to poor self-concept and low self-esteem (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Diemer, Kauffman, Koenig, Trahan, & Hsieh, 2006; Watts, Abdul-Adil, & Pratt, 2002; Watts & Guessous, 2006; White, 2007). It has been incorporated into numerous health promotion interventions for populations across the globe who experience multiple social pressures influencing their behavior (c.f., Benoit et al., 2017; Hatcher, Wet, Bonell, et al., 2011; Mahr, Wuestefeld, Ten Haaf & Krawinkel, 2005; Strange Daghio, Vezzani, & Ciardullo, 2003; White, 2007). These programs have been implemented with diverse populations, including adolescents, indigenous Canadian youth, urban youth, people with mental illness, college-aged women, domestic violence survivors, and health educators (Sharma & Romas, 2008), but not Black gay and bisexual male youth living with HIV in the United States.

Sharma (2001) suggests that the Freirian model of critical consciousness is an effective model for health promotion programs, but one that has been underutilized. Despite not being widely implemented, interventionists have detailed successful youth-focused interventions aimed at using critical consciousness or Freirian methods to promote and enhance critical consciousness and increase awareness of social injustices among African American adolescents in the U.S. (particularly those living in urban low-income environments) (Balcazar, Tandon, & Kaplan, 2001; Watts & Abdul-Adil, 1998; Watts et al., 2002). Wallerstein and Bernstein (1988) used Freire’s critical consciousness-/empowerment-focused educational theory in the Alcohol and Substance Abuse Prevention Program, a community- and school-based prevention program for adolescents in New Mexico. The intervention resulted in significantly higher rates of perceived risk for drug and alcohol abuse and promoted a greater personal awareness of the consequences of alcohol abuse among youth who participated. Although these studies have operationalized critical consciousness differently and used various methods to achieve increased levels of critical consciousness, they have shown the potential for critical consciousness interventions with youth.

Use of Critical Consciousness in HIV Prevention Interventions.

Critical consciousness is a necessary first step in helping young people to renegotiate stigmatized identities so they can be empowered to change their sexual risk behaviors (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002). Campbell and MacPhail’s (2002) work on critical consciousness development as an HIV prevention strategy for South African youth supports the need for marginalized young people to critically examine the relationships between race, sexual and gender constructions and sexual health, as well as the need to provide youth with a space for deconstructing the harmful aspects of these constructions. Specifically, empowerment to engage in healthy behaviors may need to be preceded by increases in young people’s intellectual understanding of how structural factors such as racism, heterosexism, misogyny, HIV-related stigma, poverty, and political forces influence their mental and sexual health. According to Freire (1973), individuals must first develop an intellectual understanding of how social conditions such as the inequitable distribution of resources perpetuate social injustices and the continued marginalization of oppressed groups before they can work to resist and change their situation. Thus for youth who are experiencing high rates of HIV such as Black gay/bisexual young men, they must develop a critical understanding of the role of dominant forces of White privilege (McIntosh, 1990), hegemonic masculinity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005), and social constructions of gender, race, and sexuality (Wilson, 2008) in influencing their sexual and health-seeking behaviors in order to create collective action that challenges and resists health damaging societal notions.

Use of Critical Consciousness with Black Male Youth.

Watts and his colleagues have developed an intervention to cultivate and enhance critical consciousness in young Black men in the U.S. entitled the Young Warriors program (Watts & Abdul-Adil, 1998; Watts et al., 2002; Watts et al., 1999). This research is part of a larger program of work that has led to the articulation of a theory of Sociopolitical Development (SPD) that holds critical consciousness as central tenet and emphasizes an understanding of the cultural and political forces that shape one’s status in society and the capacity to envision and help create a just society as an essential part of the process (Watts & Guessous, 2006; Watts et al., 2003). SPD theory emerged from both liberation and developmental psychology and is viewed as a critical developmental process during adolescence which reflects “growth in a person’s knowledge, analytical skills, emotional faculties, and capacity for action in political and social systems” (Watts et al., 2003, p. 185). The theory may have significant implications for HIV prevention, as behavioral research focusing on sociopolitical involvement among gay/bisexual men of color has found sociopolitical development to be linked to condom use and less HIV risk behavior (Ramirez-Valles, 2002; Wilson, Yoshikawa, & Peterson, 2002).

The Young Warriors program has a focus on enhancing critical consciousness as part of facilitating Black young men’s SPD and targets Black male youth in the U.S. living in low-income urban environments. Given the challenges that these young men face across multiple ecological systems and the negative societal messages pervasive in U.S. urban cultures about “Black men,” the intervention has a focus on promoting healthy constructions of masculinity. In line with this, the “warrior” image used in the intervention was selected due to its association with masculinity and manhood. The intervention presents aspects of the “true” warrior archetype to participants that promote belief in a higher purpose, goals, discipline and cooperation; thus enacting and reinforcing a culturally conscious reform of traditional masculinity (Watts et al., 2002). In this sense the intervention serves as a facilitator of manhood development and can impact constructions of masculinity among youth.

Similar notions of reinterpreting dominant social constructions can be taken from Watts and colleagues’ Young Warriors intervention, and the intervention can likely be applied to dominant notions and societal beliefs surrounding race, sexuality, and HIV status – all of which impact the self-esteem and health behaviors of Black gay/bisexual male youth (Hightow-Weidman, Phillips, Jones, et al., 2011; Voisin, Bird, Shiu, & Krieger, 2013). Watts has operationalized Freire’s notion of critical consciousness and applied it to the sociopolitical development of young Black men using a social action research methodology (Watts & Abdul-Adil, 1998; Watts & Guessous, 2006; Watts et al., 2002; Watts et al., 1999). The Young Warriors program uses movies and music videos about contemporary urban culture as stimuli for the critical analysis of popular culture messages about gender, culture, race, and social class in an attempt to increase young men’s critical thinking skills. The program’s critical consciousness coaching technique involves youth watching a movie or music video clip and then engaging in group dialogue and discussion using five prompts that map onto components of critical consciousness: (1) What did you see (hear)? (i.e., related to the youth’s perception of stimulus); (2) What does it mean? (i.e., links to the youth’s interpretation and meaning of the stimulus); (3) Why do you think that? (i.e., related to the defense of the youth’s interpretation); (4) How do you think and feel about what you saw or heard? (i.e., links to the emotional and intuitive response of the youth); and (5) What would you do to make it better? (i.e., related to action strategies) (Watts & Abdul-Adil, 1998; Watts et al., 1999; Watts et al., 2002).

These group discussions are facilitated by trainers who coach participants on critical thinking and critical consciousness exploration. In evaluating the critical thinking skills and critical consciousness development of the young men participating in the Young Warriors program, Watts et al. (1999, 2002) found that young men demonstrate an increase in the frequency of critical thinking/critical consciousness responses as a proportion of all categories of verbal responses over the course of the intervention. They have implemented the Young Warriors program with Black young men in a range of settings under different time schedules and lengths of time and have found similar results (Watts et al., 2002).

Use of Critical Consciousness with Black Gay/Bisexual Male Youth: A Case Example.

In the following section, we present a case example to illustrate a practical approach to using critical consciousness as part of a sexual health intervention for urban Black gay/bisexual male youth living with HIV. This case example illustrates how we used critical consciousness as the strategy for moving individuals from oppression and resulting powerlessness and engagement in health risk behaviors to empowerment and resulting feelings of control and participation health promoting behaviors. Since prior reports of critical consciousness-based interventions typically do not offer specific examples of how they operationalize critical consciousness and the steps they take to increase critical consciousness in their intervention, we present this case example. Although this case example is focused on an intervention for Black gay/bisexual male youth living with HIV, we have used a similar critical consciousness strategy as part of a primary prevention intervention for Black gay/bisexual male youth who are not living with HIV. The basic structures of the critical consciousness-related activities are the same, but the stimulus materials and discussions with participants are tailored to the population.

To address the paucity of interventions developed for Black gay/bisexual male youth who are living with HIV, we drew from the critical-consciousness intervention work of Watts and colleagues to create Mobilizing Our Voices for Empowerment (MOVE). Formative work and implementation was completed through the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV Intervention. To ensure feasibility and acceptability, youth input was vital to the development of the intervention and youth were involved throughout the entire process.

We began the first phase of intervention development by reviewing the relevant data and interventions and discussing the findings with a New York City-based Youth Advisory Board composed of Black gay/bisexual male youth living with HIV. In phase two, based on the Youth Advisory Board’s feedback, we drafted the intervention curriculum. We then tested the curriculum with focus groups consisting of the priority population in Philadelphia and Los Angeles in phase three. In phase four, we modified and further developed the curriculum based on the focus group findings with the help of a Chicago-based Youth Advisory Board, also composed of members of the priority population. Last, in phase five, we finalized MOVE curriculum with input from both the New York City- and Chicago-based Youth Advisory Boards. The intervention was then pilot tested in Chicago for feasibility and acceptability; participants took part in a focus group after completion of the intervention sessions, and the intervention activities were further refined based on that feedback. In the final step, we conducted a small-scale randomized control trial in four cities (Los Angeles, New York, Houston, & Memphis) to assess feasibility, acceptability, and initial evidence of intervention efficacy.

Similar to the Young Warriors program, MOVE utilizes media clips to initiate critical analysis of oppressive forces, such as those related to race and sexual orientation, and to help participants develop and practice potential responses to oppression in order to create positive change. Each intervention group includes two facilitators: an interventionist and a peer buddy. The peer buddy is a Black gay/bisexual young man living with HIV who is close in age to the target population. Those selected to be peer buddies are responsible and successful young men with whom participants can both relate and look to as a role model, and undergo extensive training and supervision.

Within the intervention, the Pathway to Health model makes explicit the links from oppression to health risk and from empowerment to healthy behaviors (see Figure 1). We use several concrete examples that clearly illustrate the ways that oppression can impact health (e.g., lack of educational opportunity is a form of oppression that leads to limited job prospects, a consequence of oppression, which may lead to engaging in unprotected sex or selling drugs for money, a health risk) and then encourage participants to come up with their own examples. Not only does this provide the grounding for the focus on oppression and empowerment within an HIV-related intervention, but more importantly it helps participants contemplate how oppressive forces are affecting their own health. Explicitly linking oppression and empowerment to health and presenting critical consciousness as a tool to move from oppression to empowerment is a distinctive aspect of this intervention uniquely suited to the fact that MOVE is a secondary HIV prevention intervention.

Figure 1.

Pathway to health.

The media clips used in MOVE to stimulate group discussion and critical analysis represent forms of oppression relevant to Black gay/bisexual male youth living with HIV, focusing on racism, heterosexism, and HIV stigma (Wilson, Cherenack, Jadwin-Cakmak, & Harper, 2018). We refined Watts et al.’s critical consciousness coaching technique of stimulating group discussion with five prompts by expanding the fifth prompt and including extensive follow-up to encourage participants to think realistically about taking action against oppression. Participants are provided with a worksheet called Exploring External Negativity and Actions for Critical Transformation (E2N-ACT) that lists each of the five steps: 1) What did you see or hear? Describe everything that you saw or heard in the stimulus. 2) What is the message or meaning behind what you saw or heard? Describe what you think the underlying message is in the stimulus. What do you think this says about (Black people, gay people, etc.)? 3) Why do you think that is the message? Describe what it is about the stimulus that makes you think it has the particular meaning you just described. What may have influenced that interpretation for you? 4) How do you feel about it? Describe your emotional reaction to the stimulus. 5) What can you do about it? Describe what actions you can take to improve the situation.

This fifth step is then expanded, prompting participants to explore ways they can take action to respond on individual, relational, and community levels. Specific examples of ways in which others have taken action against oppressive forces at these multiple levels give youth the opportunity to understand “real world” examples of effective social actions and social change. Participants are asked specific follow-up questions encouraging them to critically examine their action step, including: What is my goal? What do I need to achieve this goal? Who needs to be involved? Who do I need to contact? What should my message be? How do I share my message? What are my barriers (challenges)? How will I overcome these barriers? What are my facilitators (helpers)? How will I use these facilitators? How will I know I achieved my goal? By encouraging participants to think concretely about actions they can take against oppression across ecological levels, we hope they will be better prepared to respond to oppressive forces they face in their everyday lives.

Conclusions

There is a need for primary and secondary HIV prevention interventions created specifically for Black gay/bisexual male youth that address the structural factors – including racism, heterosexism, and masculinity norms – that propagate Black gay/bisexual male youth’s vulnerability to HIV (Johnson et al., 2009; Millett et al., 2007; Yoshikawa & Wilson, 2004). Empowerment provides a context for understanding the influence of such oppressive forces on individuals’ health and well-being. While many empowerment-based interventions have effectively produced behavior change (Mohajer, & Earnest, 2009; Spencer, 2014), such interventions have been critiqued for frequently concentrating on the individual and neglecting to focus on understanding how existing power structures and dominant narratives negatively impact marginalized youth’s health and well-being. Utilizing critical consciousness in empowerment-focused interventions addresses these critiques, as developing critical consciousness is a mechanism by which individuals can move from oppression to empowerment.

In the process of developing critical consciousness, individuals learn to critically analyze society’s often invisible and unquestioned dominant narratives about marginalized people and identities. Once these narratives are made visible, individuals learn how to deconstruct and challenge these dominant narratives, gaining feelings of control that lead to behaviors that promote health and well-being. The MOVE intervention provides one case example of a critical consciousness-based intervention developed specifically for Black gay/bisexual male youth. In small groups lead by a facilitator and peer buddy who are similar in age, race, and sexual orientation identity, dialogue is facilitated by viewing media clips that includes subtle or obvious racism, heterosexism, HIV-related stigma, or another type of oppression commonly experienced by this population. As a group, the young men critically analyze the message and generate various ways to respond to or challenge these messages using structured questions that encourage participants to think across ecological levels. Over the course of the intervention, the young men create their own definitions for what it means to be a Black gay/bisexual male youth, learn to be aware of and deconstruct damaging societal representations of their various identities, and begin to understand pro-social and health-promoting behaviors as a form of resistance.

The development and evaluation of additional empowerment-focused interventions for Black gay/bisexual male youth that incorporate critical consciousness-based activities should be a public health priority given the increasing rates of HIV among this population. Such interventions should provide youth with skills to decrease HIV-related risk behaviors, and assist these young men in combating the potential negative effects of discrimination and stigmatization. Critical consciousness-based interventions can assist youth in not only identifying oppressive forces that may negatively impact their HIV-related health behaviors, but also enacting social action efforts to combat these oppressive forces and build an overall sense of empowerment and control. The enhancement of a positive sense of self is especially critical during the developmental stages of adolescence and emerging adulthood, given the critical importance of identity development during this phase of life. Thus empowerment-focused HIV prevention interventions may have the potential to positively impact other elements of health and well-being among Black gay/bisexual male youth beyond HIV. Interventionists who wish to develop such programs should partner with youth in order to develop critical consciousness-based interventions for the prevention of HIV among Black gay/bisexual male youth, and actively engage these young people in all phases of intervention development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) from the National Institutes of Health [U01 HD040533 and U01 HD040474] through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (B. Kapogiannis, S. Lee), with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (K. Davenny, S. Kahana) and Mental Health (P. Brouwers, S. Allison). This study was scientifically reviewed by the ATN’s Behavioral Leadership Group. The authors thank the ATN Coordinating Center, Craig Wilson, M.D., and Cynthia Partlow for Network scientific and logistical support, the ATN Community Advisory Board and the youth who participated in the study. We acknowledge the contribution of the investigators and staff at the following sites that participated in this study: The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Douglas, Tanney, Di Benedetto), Ruth M. Rothstein CORE Center / John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital (Martinez, Henry-Reid, Bojan, Jackson), Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles (Belzer, Tucker, McAvoy-Banerjea), Montefiore Medical Center (Futterman, Campos, Enriquez-Bruce), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Gaur, Flynn, Dillard, London), and Baylor College of Medicine (Paul, Cooper, Calles).

Contributor Information

Gary W. Harper, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, 1415 Washington Heights, School of Public Health I, Room 2272, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, gwharper@umich.edu; 734-647-9778

Laura Jadwin-Cakmak, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, Center for Sexuality & Health Disparities, 400 North Ingalls St., Ann Arbor, MI 48109, ljadwin@umich.edu; 734-763-2884.

Emily Cherenak, Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, 722 W. 168th Street, 5th Floor, New York NY USA 10032, Emily.cherenack@duke.edu; 908-303-0786.

Patrick Wilson, Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, 722 W. 168th Street, 5th Floor, New York NY USA 10032, Pw2219@columbia.edu; 212-305-1852.

References

- Andrinopoulos K, Clum G, Murphy D, Harper G, Perez L, Xu J, …Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2011). Health related quality of life and psychosocial correlates among HIV-infected adolescent and young adult women in the US. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23(4), 367–381. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, & Kegeles SM (2014). ‘Triply cursed’: racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay men. Culture, health & sexuality, 16(6), 710–722. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar F, Tandon SD, & Kaplan D (2001). A Classroom-based approach for promoting critical consciousness among African-American youth. The Community Psychologist, 34(1), 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Beeker C, Guenther-Grey C, & Raj A (1998). Community empowerment paradigm drift and the primary prevention of HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine, 46(7), 831–842. doi: 10.12691/ajphr-1-2-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Landrine H, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, & Klein DJ (2013). Perceived discrimination and physical health among HIV-positive Black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 17(4), 1431–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0397-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Landrine H, Klein DJ, & Sticklor LA (2011). Perceived discrimination and mental health symptoms among Black men with HIV. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(3), 295. doi: 10.1037/a0024056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2017). Towards a critical health equity research stance: Why epistemology and methodology matter more than qualitative methods. Health Education & Behavior, 44(5), 677–684. doi: 10.1177/1090198117728760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Harper GW, & Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (2011). Operating without a safety net: Gay male adolescents and merging adults’ experiences of marginalization and migration, and implications for theory of syndemic production of health disparities. Health Education & Behavior, 38(4), 367–378. doi: 10.1177/1090198110375911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, & MacPhail C (2002). Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine, 55(2), 331–345. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00289-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2016). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report 2016:27 Accessed December 4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2017a). HIV Among Youth: Factsheet. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- CDC (2017b). HIV Among Gay and Bisexual Men: Factsheet. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Connell RW, & Messerschmidt JW (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daghio M, Vezzani M, & Ciardullo A (2003). Impact of an Educational Intervention on Breastfeeding. Birth, 30(3), 214–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, Kauffman A, Koenig N, Trahan E, & Hsieh C (2006). Challenging racism, sexism, and social injustice: Support for urban adolescents’ critical consciousness development. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12(3), 444. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Binns HJ, & Garofalo R (2009). Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS patient care and STDs, 23(5), 371–376. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap SL, Taboada A, Merino Y, Heitfeld S, Gordon RJ, Gere D, & Lightfoot AF (2017). Sexual health transformation among college student educators in an arts-based HIV prevention intervention: A qualitative cross-site analysis. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 12(3), 215–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, & Conway-Washington C (2015). Minimal Awareness and Stalled Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among at Risk, HIV-Negative, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(8), 423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisman AB, Zimmerman MA, Kruger D, Reischl TM, Miller AL, Franzen SP, & Morrel-Samuels S (2016). Psychological empowerment among urban youth: Measurement model and associations with youth outcomes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(3–4), 410–421. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1973). Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York, NY: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1990). Education for a Critical Consciousness. New York, NY: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Frye V, Nandi V, Egan J, Cerda M, Greene E, Van Tieu H, … Koblin BA (2015). Sexual orientation- and race-based discrimination and sexual HIV risk behavior among urban MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 19(2), 257–269. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0937-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Chang ST, Lee GY, Tagerman MD, Lee CS, Trentadue MP, & Hien DA (2017). Asian women’s action for resilience and empowerment intervention: Stage i pilot study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(10), 1537–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW (2007). Sex isn’t that simple: Culture and context in HIV prevention interventions for gay and bisexual male adolescents. American Psychologist, 62(8), 803–819. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW (2010). A journey towards liberation: Confronting heterosexism and the oppression of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered people In Nelson G & Prilleltensky I (Eds.), Community psychology: In pursuit of liberation and well-being (pp. 382–404). London, UK: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Fernandez IM, Bruce D, Hosek SG, Jacobs RJ, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (2013). The role of multiple identities in adherence to medical appointments among gay/bisexual male adolescents living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0071-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Lemos D, Hosek SG, & Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2014). Stigma reduction in adolescents and young adults newly diagnosed with HIV: Findings from the Project ACCEPT Intervention. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 28(10), 543–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, & Riplinger AJ (2013). HIV prevention interventions for adolescents and young adults: what about the needs of gay and bisexual males? AIDS and Behavior, 17(3), 1082–1095. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0178-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Tyler AT, Bruce D, Graham L, Wade RM, & Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2016). Drugs, sex, and condoms: Identification and interpretation of race-specific cultural messages influencing black gay and bisexual young men living with HIV. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(3–4), 463–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, & Wilson BDM (2016). Situating sexual orientation and gender identity diversity in context and communities In Bond MA, Keys CB, & Serrano-Garcia I (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Hoffman S, Mantell JE, Smit JA, Leu C-S, Exner TM, & Stein ZA (2016). Gender-Focused HIV and Pregnancy Prevention for School-Going Adolescents: The Mpondombili Pilot Intervention in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services, 15(1), 29–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher A, Wet J, Bonell CP, Strange V, Phetla G, Proynk PM, …Hargreaves JR (2011). Promoting critical consciousness and social mobilization in HIV/AIDS programmes: lessons and curricular tools from a South African intervention. Health Education Research, 26(3), 542–555. 10.1093/her/cyq057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2015). Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking more clearly about stigma, prejudice, and sexual orientation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(5S), S29–37. doi: 10.1037/ort0000092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Jones KC, Outlaw AY, Fields SD, Smith JC, & YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group. (2011). Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 25(S1), S39–45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weiman LB, Jones K, Wohl AR, Futterman D, Outlaw A, Phillips G 2nd, …YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group. (2011). Early linkage and retention in care initiative among young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 25(S1), S31–38. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek SG, Rudy B, Landovitz R, Kapogiannis B, Siberry G, Rutledge B, … Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2017). An HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) demonstration project and safety study for young MSM. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 74(1), 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek SG, Harper GW, & Domanico R (2005). Predictors of medication adherence among HIV-infected youth. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 10(2), 166–179. doi: 10.1080/1354350042000326584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek SG, Harper GW, Lemos D, & Martinez J (2008). An ecological model of stressors experienced by youth newly diagnosed with HIV. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth, 9(2), 192–218. doi: 10.1080/15538340902824118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek SG, Lemos D, Harper GW, & Telander K (2011). Evaluating the acceptability and feasibility of Project ACCEPT: an intervention for youth newly diagnosed with HIV. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23(2), 128–144. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.2.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek SG, Lemos D, Hotton AL, Fernandez MI, Telander K, Bell M, & Footer D (2015). An HIV Intervention Tailored for Black Young Men Who Have Sex with Men in the House Ball Community. AIDS Care, 27(3), 355–362. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.963016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, & Hall HI (2017). Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 27(4), 238–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussen SA, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA, Hightow-Weidman LB, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Psychosocial influences on engagement in care among HIV-positive young black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(2), 77–85. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil OB, Harper GW, Fernandez MI, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2009). Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay-bisexual-questioning (GBQ) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(3), 203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0014795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AS, Beer L, Sionean C, Hu X, Furlow-Parmley C, Le B, Skarbinski J, Hall HI, Dean HD, & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). HIV infection - United States, 2008 and 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summary, 62(Suppl 3), 112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, & Reid AE (2006). Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: Research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 41(5), 642–650. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, Lacroix JM, Anderson JR, & Carey MP (2009). Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51(4), 492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WD, Holtgrave DR, McClellan WM, Flanders WD, Hill AN, & Goodman M (2005). HIV intervention research for men who have sex with men: A 7-year update. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17(6), 568–589. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.6.568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana SY, Jenkins RA, Bruce D, Fernandez MI, Hightow-Weidman LB, Bauermeister JA, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2016). Structural determinants of antiretroviral therapy use, HIV care attendance, and viral suppression among adolescents and young adults living with HIV. PloS one, 11(4), e0151106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam PK, Naar-King S, & Wright K (2007). Social support and disclosure as predictors of mental health in HIV positive youth. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21(1), 20–29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MJ, Frank HG, Harawa NT, Williams JK, Chou C & Bluthenthal RN (2018). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 169–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, …Mullins MM (2007). Best-evidence interventions: Findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonell KE, Naar-King S, Murphy DA, Parsons JT, & Harper GW (2010). Predictors of medication adherence in high risk youth of color living with HIV. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(6), 593–601. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H & Belzer M (2013). Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 86–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahr J, Wuestefeld M, Ten Haaf J, & Krawinkel M (2005). Nutrition education for illiterate children in southern Madagascar – addressing their needs, perceptions and capabilities. Public Health Nutrition, 8(4), 366–372. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Fields EL, Bryant LO, & Harper SR (2009). Masculine socialization and sexual risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men: A qualitative exploration. Men and Masculinities, 12(1), 1–23. doi: 10.1177/1097184X07309504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Peterson JL, Fullilove RE, & Stackhouse RW (2004). Race and sexual identity: perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among Black men who have sex with men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 96(1), 97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J, Harper G, Carleton RA, Hosek S, Bojan K, Clum G, Ellen J, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2012). The impact of stigma on medication adherence among HIV-positive adolescent and young adult females and the moderating effects of coping and satisfaction with health care. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 26(2), 108–115. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh P (1990). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. Retrieved from http://ted.coe.wayne.edu/ele3600/mcintosh.html

- Miller RL (2007). Legacy denied: African American gay men, AIDS, and the Black church. Social Work, 52(1), 51–61. 10.1093/sw/52.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Malebranche DJ, & Peterson JL (2007). HIV/AIDS prevention research among Black men who have sex with men: Current progress and future directions In Meyer I & Northridge M (Eds.), The Health of Sexual Minorities: Public Health Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered Populations, (pp. 539–565). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohajer N, & Earnest J (2009). Youth empowerment for the most vulnerable: A model based on the pedagogy of Freire and experiences in the field. Health Education, 109(5), 424–438. doi: 10.1108/09654280910984834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, & Prilleltensky I (2010). Community psychology: In pursuit of liberation and well-being (2nd ed.). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent NR, Brown LK, Belzer M, Harper GW, Nachman S, Naar-King S, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (2010). Youth living with HIV and problem substance use: elevated distress is associated with nonadherence and sexual risk. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care, 9(2), 113–115. doi: 10.1177/1545109709357472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, & Aggleton P (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1), 13–24. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00304–0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky I (2003). Understanding, resisting, and overcoming oppression: toward psychopolitical validity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1–2), 195–201. doi: 10.1023/A:1023043108210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky I, & Nelson G (2002). Doing psychology critically making a difference in diverse settings. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe J, Doty N, Hawkins LA, Gaskins CS, Beidas R, & Rudy BJ (2010). Stigma and sexual health risk in HIV-positive African American young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 24(8), 493–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J (2002). The protective effects of community involvement for HIV risk behavior: a conceptual framework. Health Education Research, 17(4), 389–403. doi: 10.1093/her/17.4.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasberry CN, Condron DS, Lesesne CA, Adkins SH, Sheremenko G, & Kroupa E (2018). Associations between sexual risk-related behaviors and school-based education on HIV and condom use for adolescent sexual minority males and their non-sexual-minority peers. LGBT Health, 5(1), 69–77. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(2), 121–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Garcia I, & Lopez-Sanchez G. (1992). Asymmetry and oppression: Prerequisites of power relationships Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-García I (1984). The illusion of empowerment: Community development within a colonial context. Prevention in Human Services, 3(2–3), 173–200. doi: 10.1300/J293v03n02_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M (2001). Freire’s Adult Education Model: An Underutilized Model in Alcohol and Drug Education? Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education, 47(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M & Romas JA (2008). Theoretical Foundations of Health Education and Health Promotion. Boston, MA: Jones and Barlett Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, Klein WM, Boyington J, Moten C, & Rorie E (2012). The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 953–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer PW, & Hughey J (1995). Community organizing: an ecological route to empowerment and power. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 729–748. doi: 10.1007/BF02506989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer G (2014). Young people and health: Towards a new conceptual framework for understanding empowerment. Health, 18(1), 3–22. doi: 10.1177/1363459312473616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, & Peterson JL (1998). Homophobia, self-esteem, and risk for HIV among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 10(3), 278–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss BB, Greene GJ, Phillips G, Bhatia R, Madkins K, Parsons JT, & Mustanski B (2017). Exploring Patterns of Awareness and Use of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1288–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Super S, Wagemakers MAE, Picavet HSJ, Verkooijen KT, & Koelen MA (2015). Strengthening sense of coherence: opportunities for theory building in health promotion. Health Promotion International, 31(4), 869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghipour A, Sadat Borghei N, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Keramat A, & Jabbari Nooghabi H (2016). Psychological Empowerment Model in Iranian Pregnant Women. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 4(4), 339–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Huynh VW, Jones SK, Lee S, & Revels-Macalinao M (2017). Sexual minority youth of color: A content analysis and critical review of the literature. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(1), 3–31. 10.1080/19359705.2016.1217499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni SE, Miller CT, McCuin T, & Solomon SE (2012). Disengagement and Engagement Coping with HIV/AIDS Stigma and Psychological Well-Being of People with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31(2), 123–150. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2012.31.2.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Bird JD, Shiu CS, & Krieger C (2013). “It’s crazy being a Black, gay youth.” Getting information about HIV prevention: A pilot study. Journal of Adolescence, 36(1), 111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade RM, & Harper GW (2017). Young Black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men: A review and content analysis of health-focused research between 1988 and 2013. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1388–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Bernstein E (1988). Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Sanchez-Merki V (1994). Freirian praxis in health education: Research results from an adolescent prevention program. Health Education Research, 9(1), 105–118. 10.1093/her/9.1.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt RG (2002). Emerging theories into the social determinants of health: Implications for oral health promotion. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 30(4), 241–247. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, & Abdul-Adil JK (1998). Promoting critical consciousness in young, African-American men. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 16(1–2), 63–86. 10.1300/J005v16n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, Abdul-Adil JK, & Pratt T (2002). Enhancing critical consciousness in young African American men: A psychoeducational approach. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 3(1), 41. doi: 10.1037//1524-9220.3.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, Griffith DM, & Abdul-Adil J (1999). Sociopolitical development as an antidote for oppression—theory and action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(2), 255–271. doi: 10.1023/A:1022839818873 [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, & Guessous O (2006). Sociopolitical development: The missing link in research and policy on adolescents In Ginwright S, Noguera P & Cammarota J (Eds.), Beyond Resistance! Youth Activism and Community Change: New Democratic Possibilities for Practice and Policy for America’s Youth (pp. 59–80). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, Serrano-Garcia I (2003). The quest for a liberating community psychology: An overview. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1 &2), 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, Williams NC, & Jagers RJ (2003). Sociopolitical development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1–2), 185–194. doi: 10.1023/A:1023091024140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J (2007). Working in the midst of ideological and cultural differences: Critically reflecting on youth suicide prevention in Indigenous communities. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy/Revue canadienne de counseling et de psychothérapie, 41(4). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, & Harper GW (2013). Race and ethnicity in lesbian, gay and bisexual communities In Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation, edited by Patterson CJ and D’Augelli AR. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA (2008). A dynamic-ecological model of identity formation and conflict among bisexually-behaving African-American men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(5), 794–809. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9362-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, & Moore TE (2009). Public health responses to the HIV epidemic among black men who have sex with men: A qualitative study of US health departments and communities. American Journal of Public Health, 99(6), 1013–1022. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Yoshikawa H, & Peterson JL (2002). Proceedings of the XIV International AIDS Conference: The impact of social networks and social/political group participation on HIV-risk behaviors of African American men who sex with men MoPeC3426. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, & Wilson PA (2004). HIV prevention among men of color who have sex with men: Why has there not been more progress? The Community Psychologist, 37(2), 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zea MC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT, & Echeverry JJ (2007). Predictors of disclosure of human immunovirus-positive serostatus among Latino gay men. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(4), 304–312. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA (1995). Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581–699. doi: 10.1007/BF02506983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA (2000). Empowerment Theory: Psychological, Organizational and Community Levels of Analysis In Rappaport J & Seidman E (Eds.), Handbook of Community Psychology (pp. 43–66). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Eisman AB, Reischl TM, Morrel-Samuels S, Stoddard S, Miller AL, … Rupp L (2018). Youth Empowerment Solutions: Evaluation of an after-school program to engage middle school students in community change. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 45(1), 20–31. 10.1177/1090198117710491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]