Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

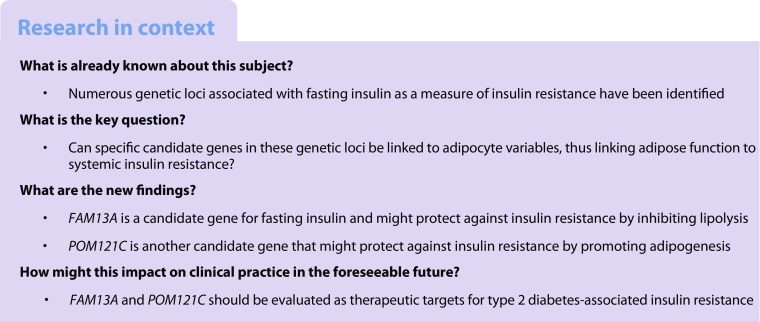

By genome-wide association meta-analysis, 17 genetic loci associated with fasting serum insulin (FSI), a marker of systemic insulin resistance, have been identified. To define potential culprit genes in these loci, in a cross-sectional study we analysed white adipose tissue (WAT) expression of 120 genes in these loci in relation to systemic and adipose tissue variables, and functionally evaluated genes demonstrating genotype-specific expression in WAT (eQTLs).

Methods

Abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies were obtained from 114 women. Basal lipolytic activity was measured as glycerol release from adipose tissue explants. Adipocytes were isolated and insulin-stimulated incorporation of radiolabelled glucose into lipids was used to quantify adipocyte insulin sensitivity. Small interfering RNA-mediated knockout in human mesenchymal stem cells was used for functional evaluation of genes.

Results

Adipose expression of 48 of the studied candidate genes associated significantly with FSI, whereas expression of 24, 17 and 2 genes, respectively, associated with adipocyte insulin sensitivity, lipolysis and/or WAT morphology (i.e. fat cell size relative to total body fat mass). Four genetic loci contained eQTLs. In one chromosome 4 locus (rs3822072), the FSI-increasing allele associated with lower FAM13A expression and FAM13A expression associated with a beneficial metabolic profile including decreased WAT lipolysis (regression coefficient, R = −0.50, p = 5.6 × 10−7). Knockdown of FAM13A increased lipolysis by ~1.5-fold and the expression of LIPE (encoding hormone-sensitive lipase, a rate-limiting enzyme in lipolysis). At the chromosome 7 locus (rs1167800), the FSI-increasing allele associated with lower POM121C expression. Consistent with an insulin-sensitising function, POM121C expression associated with systemic insulin sensitivity (R = −0.22, p = 2.0 × 10−2), adipocyte insulin sensitivity (R = 0.28, p = 3.4 × 10−3) and adipose hyperplasia (R = −0.29, p = 2.6 × 10−2). POM121C knockdown decreased expression of all adipocyte-specific markers by 25–50%, suggesting that POM121C is necessary for adipogenesis.

Conclusions/interpretation

Gene expression and adipocyte functional studies support the notion that FAM13A and POM121C control adipocyte lipolysis and adipogenesis, respectively, and might thereby be involved in genetic control of systemic insulin sensitivity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00125-018-4572-8) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Genomics, Insulin sensitivity, Lipid metabolism

Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR), wherein cellular responses to insulin are impaired, is a key component of type 2 diabetes and is also implicated in the development of cardiovascular disease [1]. IR is associated with metabolic disturbances in liver, skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue (WAT) and is characterised by hyperinsulinaemia, hyperglycaemia and dyslipidaemia. Fasting serum insulin (FSI) has been shown to correlate with the gold standard for assessing IR, namely euglycaemic insulin clamp, and is therefore used as a simple proxy for insulin sensitivity in various studies [2].

Abdominal obesity and a state of overweight are strong risk factors for systemic IR [3]. Abdominal obesity is associated with altered cytokine and adipokine release from WAT, which is linked to low-grade inflammation and systemic IR [4]. In addition, adipose morphology is central to IR and development of type 2 diabetes [5, 6]. WAT can expand by increasing the number and/or volume of adipocytes causing distinct adipose morphologies termed hyperplasia (many small adipocytes) or hypertrophy (few large adipocytes). Hypertrophic adipose tissue is associated with a pernicious metabolic profile, with blunted ability of insulin to stimulate fat synthesis through glucose conversion into lipids (lipogenesis), leading to an influx of NEFA into the liver and to systemic IR [7, 8]. The lipolytic activity in adipose tissue, resulting in the release of NEFA, can also influence insulin sensitivity, as reviewed [9].

Despite these findings, it is still to a large extent unclear how IR develops and only about 25% of obese women are insulin resistant [10]. One explanation is varying genetic predisposition; genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 17 SNPs associated with FSI and/or FSI adjusted for BMI (FSIadjBMI) [11]. With the aim of defining culprit genes in these loci, and the mechanisms by which they may directly predispose to IR, we herein analysed WAT expression of 120 genes in these loci in relation to FSI and adipocyte phenotypes related to IR (morphology, insulin-stimulated lipogenesis, lipolysis). We also performed in silico expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analysis and selected genes demonstrating genotype-specific expression in WAT for functional analysis by small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown followed by evaluation of adipocyte-specific genes and glycerol release.

Methods

Participants

The study included 114 Swedish non-diabetic women with WAT global transcriptome profile available from a previous study [12]. The women were recruited by advertisement from the general adult population in the Stockholm (Sweden) area (Table 1). They displayed a large inter-individual variation in BMI and were healthy, except that some were obese. The study was approved by the regional ethics board in Stockholm and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The experiments conformed to the principles set out in the WMA Declaration of Helsinki and the Department of Health and Human Services Belmont Report. Participants were investigated at 08:00 hours after an overnight fast in a university clinic. Anthropometric measurements (height, weight, waist and hip circumference, blood pressure) were performed followed by venous blood sampling. WHR adjusted for BMI (WHRadjBMI) was calculated in a sex-specific manner by inverse-normal transformation of the residuals of the linear regression model: WHR adjusted for age, age2 and BMI [13]. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and lipids were analysed at the hospital’s routine chemistry laboratory. Plasma insulin was measured by ELISA (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) as previously described [14]. The Mercodia Diabetes Antigen Control (10-1134-01/10-1164-01) was included as control in all ELISA runs; samples were visually inspected before each run and no sample showed signs of haemolysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 114 examined women

| Characteristic | Means±SD |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 43 ± 11 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 34 ± 9 |

| FPG, mmol/l | 5.17 ± 0.65 |

| FSI, pmol/l | 63 ± 50 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.96 ± 2.12 |

| Fasting plasma total cholesterol, mmol/l | 4.9 ± 0.9 |

| Fasting plasma HDL-cholesterol, mmol/l | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| Fasting plasma triacylglycerols, mmol/l | 1.3 ± 0.8 |

| Fat cell volume, pl | 731 ± 266 |

| WAT morphologya, plb | 17 ± 165 |

| Basal lipolysisc, μmol glycerol (2 h)−1 (107 adipocytes)−1 | 4.26 ± 2.62 |

| Insulin-stimulated lipogenesisd, nmol of glucose (2 h)−1 (107 adipocytes)−1 | 4.71 ± 6.22 |

aData were missing from 11 women

bDefined in the ‘WAT experiments’ section of the Methods

cData were missing from 22 women

dData were missing from five women

Following the clinical examination, an abdominal subcutaneous WAT biopsy was obtained by needle aspiration, as described [15]. All WAT samples were rapidly rinsed in sodium chloride (9 mg/ml) and specimens of 300 mg unfractionated WAT were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA isolation. Remaining tissue was used immediately for cell culture experiments as described below. No follow-up of participants was performed.

WAT experiments

The adipose tissue was brought to the laboratory, rinsed repeatedly in saline (154 mmol/l NaCl) and visible blood vessels and cell debris were removed. Adipose tissue specimens (about 1 g) were divided into portions, one of which was treated with collagenase to obtain isolated adipocytes as described [16]. The mean weight and volume of these cells were determined as previously described [17, 18]. A curve fit of the relationship between mean adipocyte volume and total fat mass was performed as previously reported to assess adipose tissue morphology [19]. The difference between the measured and the expected fat cell volume obtained from the mean curve fit at the corresponding fat mass determines adipose morphology. If the measured fat cell volume is larger than expected, adipose hypertrophy prevails, whereas the opposite is valid for hyperplasia. These values, which can be quantitatively assessed, were obtained from the calculations made previously [19].

Spontaneous unstimulated lipolytic activity was determined in adipose tissue explants as described [20]. In brief, pieces of adipose tissue (200 or 300 mg) were incubated for 2 h (100 mg/ml) at 37°C with air as the gas phase in Krebs–Ringer phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) supplemented with glucose (8.6 mmol/l), ascorbic acid (0.1 mg/ml) and bovine serum albumin (20 mg/ml). Glycerol release into the medium was measured using a sensitive bioluminescence method and expressed as amount of glycerol released per 2 h and 107 adipocytes.

Adipocyte lipogenesis was determined as described [21]. In brief, isolated adipocytes were incubated in vitro in an albumin-containing buffer with [3H]glucose (5 × 105 dpm/ml), unlabelled glucose (0.001 mmol/l) and varying concentrations (0–70 nmol/l) of human insulin (I 2643, Sigma-Aldrich, Stockholm, Sweden). The incubations were conducted for 2 h at 37°C with air as the gas phase. Incubations were stopped by rapidly chilling the incubation vials to 4°C. Thereafter, incorporation of radiolabelled glucose into adipocyte lipids was determined; this reflects lipogenesis and was expressed as the amount of glucose incorporated per adipocyte number, as described previously [21]. Values at the maximum effective insulin concentration are reported.

Microarray data

Global transcriptome profiles of WAT from the clinical cohort were assessed by Gene 1.0 or 1.1 ST Affymetrix arrays and has been reported earlier [12]. In this study we limited the analysis to candidate genes for FSI or FSIadjBMI listed in Scott et al [11], as well as genes ±500 Kb of the tag-SNPs. Genome information was extracted from SNPPER (http://snpper.chip.org/bio/snpper-enter) using genome build 38 (accessed 9 August 2016). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/) was used for network analysis (accessed 18 September 2017). SNPnexus (http://snp-nexus.org/) was used for SNP annotation (accessed 10 June 2017) [22]. GTEx database (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/) was used to identify WAT eQTLs (accessed 28 August 2016).

Adipocyte cell culture and small interfering RNA transfection

Isolation, growth and differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were carried out as previously described [23]. hMSCs at day 4 of differentiation were transfected using a Neon electroporator (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 1,000,000 hMSCs were mixed with 40 nmol/l ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting POM121C, UHRF1BP1, SNRPC and FAM13A or non-targeting siRNA pool (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA) and electroporated using 100 μl Neon electroporation tip. Electroporation conditions were 1600 V, 20 ms width, 1 pulse. Electroporation was repeated until the required number of cells was collected for a certain experimental set-up. Following electroporation, the cells were plated in antibiotic-free medium at a density of 220,000 cells/well in 24-well plates. Medium was replaced 24 h post-transfection. The cells were cultured until day 7 or 12 of differentiation, at which time the medium and RNA were collected. hMSCs were also reverse transfected 24 h before induction of adipogenesis using ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNAs targeting FAM13A or non-targeting siRNA pool (Dharmacon) as previously described [24].

Quantitative RT-PCR

WAT specimens (100 mg) from the clinical samples were disrupted mechanically and RNA isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The hMSCs were collected on days 7 and 12 after the induction of differentiation for isolation of RNA. Total RNA from the hMSCs cultures was extracted using NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The concentration and purity of RNA were measured using a Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Qiagen) and random hexamer primers (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using commercial TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gene expression in the clinical cohort was normalised to the internal reference gene LRP10, and in the cell culture experiments to 18S. Relative expression was calculated using the method [25].

Glycerol measurements

Glycerol in media was measured using Free Glycerol Reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and Amplex UltraRed (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Amplex Ultra Red was diluted 100-fold in Free Glycerol Reagent, mixed with 20 μl of conditioned medium in a 96-well plate, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Fluorescence was measured (excitation/emission wavelengths 530 nm / 590 nm) using an Infinite M200 plate reader (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Statistical analysis

FSI, lipolysis and lipogenesis measurements were log10 transformed before analysis to obtain normally distributed variables. Microarray results from the clinical cohort were analysed by regression in QLUCORE version 3.2 (www.qlucore.com), adjusting for array batch and, as indicated, age. Phenotypes correlating with BMI (i.e. FSI, FPG, insulin-stimulated lipogenesis and lipolysis) were analysed both without and with BMI as covariates, as specified. False discovery rate (FDR) was used to adjust for the analysis of multiple genes. FDR <5% was considered significant. Quantitative RT-PCR results and clinical variable were analysed by regression in JJMP v. 11 (www.jmp.com). Results of in vitro experiments were analysed by paired t test.

Results

FSI and adipose traits

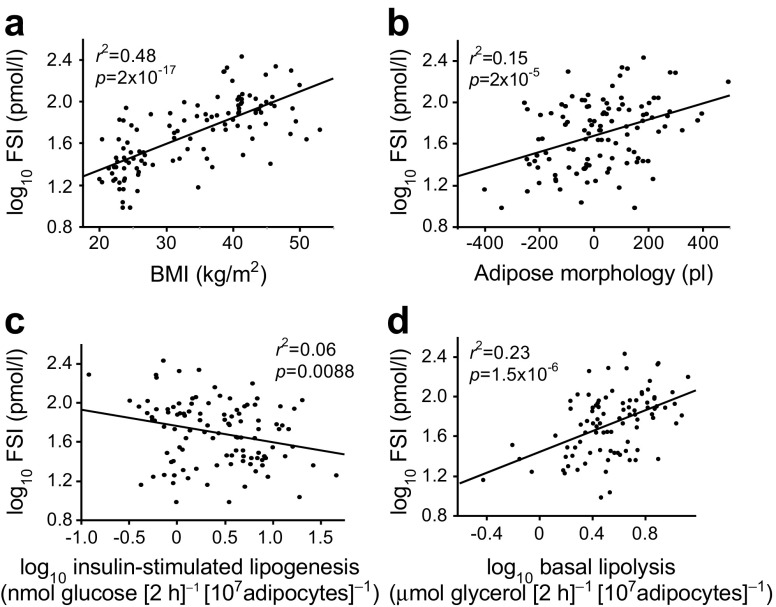

The cohort characteristics are shown in Table 1. The studied women displayed a wide variation in BMI and FSI. As expected, BMI was positively correlated with FSI (r2 = 0.48, p = 2.0 × 10−17) (Fig. 1a). BMI was also positively correlated with adipose spontaneous lipolysis (r2 = 0.15, p = 0.0002) and inversely correlated with insulin-stimulated lipogenesis (r2 = 0.08; p = 0.0038) (results not shown). There was no significant association with adipose morphology. FSI was positively correlated with adipose morphology (r2 = 0.15, p = 2.0 × 10−5) and spontaneous lipolysis (r2 = 0.23, p = 1.5 × 10−6) but was negatively correlated with insulin-stimulated lipogenesis (r2 = 0.06, p = 0.0088) (Fig. 1b–d). Associations between FSI and morphology (p = 1.3 × 10−6) or spontaneous lipolysis (p = 0.0019) remained significant in a multiple regression including BMI as independent variable. There was no influence of age on the examined variables (results not shown).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between FSI and BMI (a), adipose morphology (b), insulin-stimulated lipogenesis (c) and basal lipolysis (d). n = 114 women. Defined in the ‘WAT experiments’ section of the Methods. Linear regression was used in all analyses

Expression of candidate genes for FSI in relation to adipose traits

We next examined whether WAT expression of genes in loci robustly associated with FSI and FSIadjBMI were associated with clinical or adipose phenotypes related to IR. There were 135 protein-coding transcripts in the 17 FSI- and FSIadjBMI-associated loci (ESM Table 1) and expression of 120 of these transcripts were quantified by array. We did not analyse non-coding transcripts since microRNAs were not enriched in the total prepared RNA from WAT, and other non-coding transcripts and RNAs were not represented with probes on the arrays. Expression of 56 genes was associated with BMI (FDR <5%) (Table 2 and ESM Table 2) but only one gene was associated with WHR. The expression of 48 genes was associated with FSI, of which 11 remained nominally significant after adjustment for BMI, whereas 19 genes were associated with FPG, of which two remained nominally significant after adjustment for BMI.

Table 2.

Adipose expression of candidate genes in loci associated with FSI and their association with clinical and adipose variables

| Chr | Trait | SNP | Gene | BMI | FSI | FPG | Basal lipolysis | Insulin-stimulated lipogenesis | WAT morphology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | R | p value | R | p value | R | p value | R | p value | R | p value | R | ||||

| 1 | FSI | rs2820436 | LYPLAL1 a | 1.2 × 10−4b | – | 1.1 × 10−2b | – | 4.4 × 10−2 | – | 2.6 × 10−2 | – | ||||

| FSIadjBMI | rs4846565 | EPRS | 1.6 × 10−3b | + | 1.5 × 10−5b,c | + | 4.8 × 10−3b | – | |||||||

| IARS2 | 1.3 × 10−4b | – | 4.0 × 10−3b | – | 2.0 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||

| RAB3GAP2 | 8.7 × 10−4b | – | 8.4 × 10−3b | – | 7.1 × 10−3b | – | 1.9 × 10−4b,c | – | 1.0 × 10−2 | – | |||||

| 2 | FSI | rs1530559 | R3HDM1 | 1.5 × 10−5a,c | + | ||||||||||

| UBXN4 | 9.7 × 10−a | – | |||||||||||||

| MCM6 | 2.2 × 10−2 | – | 2.4 × 10−3b,c | – | 3.6 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||

| DARS | 3.6 × 10−12b | – | 3.9 × 10−8b | – | 2.0 × 10−3b | – | 9.3 × 10−4b | – | 6.9 × 10−4b | + | 3.2 × 10−2 | – | |||

| CXCR4 | 6.9 × 10−5b | + | 1.1 × 10−3b | + | 3.3 × 10−2 | + | 2.2 × 10−2 | + | 2.7 × 10−2 | – | 4.4 × 10−3 | + | |||

| 2 | FSI | rs10195252 | GRB14 a | 1.1 × 10−2b | + | 2.9 × 10−2 | + | 3.5 × 10−4b,c | – | ||||||

| FSIadjBMI | CSRNP3 | 1.4 × 10−3b | + | 3.3 × 10−2 | + | 4.0 × 10−2 | – | ||||||||

| GALNT3 | 1.3 × 10−2b | + | |||||||||||||

| TTC21B | 1.3 × 10−8b | – | 1.0 × 10−6b | – | 4.2 × 10−5b,c | – | 7.5 × 10−4b | – | 8.1 × 10−3 | – | |||||

| SCN1A | 3.1 × 10−3b | – | 3.1 × 10−2 | – | 3.6 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||

| 2 | FSI | rs2972143 | IRS1 a | 1.8 × 10−7b | – | 2.8 × 10−5b | – | 2.6 × 10−3b | – | 3.4 × 10−4b | + | 3.3 × 10−2 | – | ||

| FSIadjBMI | rs2943645 | RHBDD1 | 1.3 × 10−2b | + | 3.0 × 10−3b | + | 1.0 × 10−2 | + | |||||||

| MFF | 2.3 × 10−3b | – | |||||||||||||

| AGFG1 | 1.7 × 10−8b | + | 6.9 × 10−8b,c | + | 3.9 × 10−3b | + | 7.9 × 10−4b | + | 2.7 × 10−3b | – | 2.5 × 10−2 | + | |||

| 3 | FSIadjBMI | rs17036328 | PPARG a | 7.1 × 10−15b | – | 3.9 × 10−11b,c | – | 3.5 × 10−3b | – | 8.3 × 10−6b,c | – | 5.7 × 10−6b,c | + | 2.8 × 10−3 | – |

| SYN2 | 1.1 × 10−3b | – | 1.2 × 10−3b | – | |||||||||||

| TSEN2 | 2.8 × 10−5b | – | 1.2 × 10−3b | – | 4.5 × 10−2 | – | 1.3 × 10−3b | – | 2.0 × 10−2 | + | 3.0 × 10−3 | – | |||

| RAF1 | 6.9 × 10−4b | + | 1.2 × 10−3b | + | 6.0 × 10−4b,c | – | |||||||||

| TMEM40 | 3.6 × 10−4b,c | + | |||||||||||||

| 4 | FSIadjBMI | rs3822072 | FAM13A a | 2.2 × 10−15b | – | 5.6 × 10−12b,c | – | 6.7 × 10−4b | – | 5.6 × 10−7b,c | – | 1.6 × 10−2 | + | 8.2 × 10−4b | – |

| GPRIN3 | 1.0 × 10−9b | + | 6.3 × 10−6b | + | 3.7 × 10−2 | + | 3.5 × 10−3b | – | |||||||

| SNCA | 5.8 × 10−3b | + | 9.6 × 10−3b | + | 1.4 × 10−3b | + | 8.2 × 10−3 | + | |||||||

| MMRN1 | 1.4 × 10−3b | + | 2.2 × 10−3b | + | 3.0 × 10−2 | + | |||||||||

| CCSER1 | 1.1 × 10−2b | + | 1.6 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||||

| 4 | FSI | rs9884482 | INTS12 | 3.3 × 10−2 | – | 8.8 × 10−3b | – | 3.5 × 10−2 | – | ||||||

| FSIadjBMI | rs974801 | GSTCD | 7.3 × 10−3b | + | |||||||||||

| TBCK | 1.6 × 10−2b | – | 2.8 × 10−2 | – | 5.8 × 10−3b | – | |||||||||

| AIMP1 | 4.2 × 10−5b | – | 7.9 × 10−4b | – | 1.3x10−3b | – | 6.2 × 10−2 | – | 2.7 × 10−2 | + | |||||

| 4 | FSIadjBMI | rs6822892 | FAM198B | 3.3 × 10−8b | + | 1.4 × 10−7b,c | + | 3.8 × 10−3b | + | 2.1 × 10−2 | + | 4.7 × 10−3b | – | 6.1 × 10−3 | + |

| 5 | FSI | rs4865796 | ARL15 a | 1.5 × 10−5b | + | 1.0 × 10−4b | + | 2.4 × 10−2 | + | 1.8 × 10−6b,d | – | 5.2 × 10−3 | + | ||

| FSIadjBMI | ITGA2 | 2.1 × 10−5b | + | 5.1 × 10−5b | + | 1.3 × 10−2 | + | 3.0 × 10−2 | + | 6.4 × 10−3b,c | – | ||||

| MOCS2 | 1.1 × 10−5b | – | 1.3 × 10−3b | – | 5.2 × 10−3b | – | 4.6 × 10−2 | – | |||||||

| NDUFS4 | 2.0 × 10−8b | – | 2.4 × 10−7b | – | 4.0 × 10−2 | – | 2.2 × 10−4b | + | 5.9 × 10−5b | – | |||||

| 5 | FSIadjBMI | rs459193 | MAP3K1 a | 5.8 × 10−9b | + | 2.9 × 10−8b,c | + | 1.0 × 10−3b | + | 2.9 × 10−3b | + | 7.2 × 10−5b | – | 3.7 × 10−2 | + |

| SKIV2L2 | 1.9 × 10−6b | – | 1.5 × 10−5b | – | 3.3 × 10−3 | – | 5.5 × 10−4b | – | 1.4 × 10−2 | – | |||||

| 6 | FSIadjBMI | rs6912327 | UHRF1BP1 a | 1.1 × 10−2 | – | ||||||||||

| NUDT3 | 2.9 × 10−5b | + | 2.0 × 10−8b,c | + | 1.4 × 10−3b | + | 8.9 × 10−3 | + | 2.6 × 10−2 | – | |||||

| RPS10 | 1.0 × 10−2b | – | 4.2 × 10−3 | – | |||||||||||

| C6orf106 | 1.2 × 10−5b | + | 3.4 × 10−4b | + | 3.2 × 10−2 | + | 2.1 × 10−3b | + | 3.1 × 10−2 | + | |||||

| TCP11 | 6.0 × 10−3b | – | 1.8 × 10−2b | – | |||||||||||

| SCUBE3 | 2.4 × 10−3b,c | – | |||||||||||||

| 6 | FSI | rs2745353 | RNF146 | 2.6 × 10−6b | – | 8.7 × 10−4b | – | 6.2 × 10−3b | – | 3.0 × 10−3b | – | 8.6 × 10−3 | – | ||

| ECHDC1 | 2.5 × 10−2 | – | 1.7 × 10−3a | + | |||||||||||

| THEMIS | 5.1 × 10−5b | + | 7.0 × 10−5b | + | 7.5 × 10−3b | + | 5.6 × 10−3b | – | |||||||

| 7 | FSI | rs1167800 | GTF2I | 8.5 × 10−6b | – | 9.0 × 10−4b | – | 3.2 × 10−2 | – | 2.4 × 10−4b | – | ||||

| NCF1 | 5.2 × 10−4b | + | 2.0 × 10−3b | + | 2.9 × 10−3b | + | 1.8 × 10−2 | + | |||||||

| STAG3L2 | 2.3 × 10−4b | – | 2.0 × 10−2b | – | 3.3 × 10−4b | + | 1.3 × 10−2 | – | |||||||

| GATSL2 | 4.3 × 10−9b | + | 2.5 × 10−10b,c | + | 3.8 × 10−3b | + | 1.7 × 10−3b | – | 2.1 × 10−3 | + | |||||

| SPDYE8P | 3.5 × 10−3b | – | 2.4 × 10−4b,c | – | 1.0 × 10−3b | – | |||||||||

| TRIM73 | 1.5 × 10−2b | – | |||||||||||||

| POM121C | 1.1 × 10−3b | – | 2.0 × 10−2b | – | 3.4 × 10−3b | + | 2.6 × 10−2 | – | |||||||

| PMS2P3 | 8.0 × 10−3 | – | 4.8 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||||

| 8 | FSIa | rs983309 | PPP1R3B a | 2.9 × 10−3b | – | ||||||||||

| FSIadjBMI | rs2126259 | CLDN23 | 4.9 × 10−3b | – | 1.0 × 10−2b | – | 2.9 × 10−3b | – | 1.2 × 10−2 | – | |||||

| MFHAS1 | 3.0 × 10−11b | + | 5.1 × 10−6b | + | 3.7 × 10−2 | + | 2.4 × 10−4b | – | |||||||

| ERI1 | 4.1 × 10−5b | + | 1.4 × 10−3b | + | 2.1 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||

| TNKS | 1.1 × 10−2b | – | 6.2 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||||

| 10 | FSI | rs7903146 | TCF7L2 a | 1.2 × 10−3b | – | 4.2 × 10−2 | – | 2.1 × 10−2 | – | 2.4 × 10−2 | – | 3.6 × 10−3 | – | ||

| ABLIM1 | 1.7 × 10−5b | + | 1.2 × 10−3b | + | 3.3 × 10−2 | + | 3.1 × 10−2 | + | 2.4 × 10−6b | – | |||||

| 16 | FSI | rs1421085 | FTO c | 7.2 × 10−3b | + | ||||||||||

| RBL2 | 2.7 × 10−5b | – | 4.0 × 10−2 | – | 3.3 × 10−2 | – | 2.8 × 10−4b | – | 9.8 × 10−3 | – | |||||

| RPGRIP1L | 2.4 × 10−5b | + | 1.5 × 10−6b,c | + | 3.4 × 10−2 | + | |||||||||

| IRX3 | 1.0 × 10−3b | – | 9.4 × 10−3b | – | 1.1 × 10−2 | – | |||||||||

| 19 | FSI | rs731839 | PEPD a | 1.6 × 10−6b | + | 1.5 × 10−3b | + | 2.4 × 10−2 | + | 1.3 × 10−2 | + | ||||

| FSIadjBMI | KCTD15 | 7.1 × 10−3b | + | ||||||||||||

Microarray results from the clinical cohort were analysed by regression in QLUCORE, adjusting for array batch, and for WAT morphology, adjusting for age. Only results with p < 0.05 are shown

aOriginal candidate gene from Scott et al [11]

bFDR <5%

cNominally significant after adjustment for BMI in QLUCORE

R, regression coefficient, which can be either positive (+) or negative (−)

For WAT variables, 24 genes were associated with insulin-stimulated lipogenesis (FDR <5%); five of these genes remained nominally significant after adjustment for BMI. Expression of 17 genes was associated with spontaneous lipolysis and four remained significant after adjusting for BMI. Only two genes were associated with adipose morphology (Table 2, ESM Table 2). Expression of four genes was correlated with age (i.e. GSTCD, IRS1, SCN3A and TIMP4); however, adjustment for age did not affect the relationship between expression of these genes and FSI or adipose phenotypes (results not shown). Expression of three genes whose expression associated with FSI was validated by quantitative RT-PCR using RNA from subcutaneous WAT obtained from a previously examined cohort of 55 women (ESM Table 3) [26]. Results were directionally consistent between microarray and quantitative RT-PCR for all three genes and analysed phenotypes, except for the association between insulin-stimulated lipogenesis and ARL15 expression levels.

Network analysis

The 48 genes whose expression related to FSI, 24 genes related to insulin-stimulated lipogenesis and 17 genes related to lipolysis were analysed in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. The genes associated with insulin-stimulated lipogenesis were enriched in several signalling pathways, including activation of NF-κB and MAPK signalling (ESM Table 4). These results were related to altered expression of PPARG, IRS1, ITGA2, RAF1 and MAP3K1. Interestingly, the same signalling pathways, including NF-κB activation, were also enriched among FSI-associated genes; the genes mentioned above also contributed to the results for FSI (ESM Table 5). The lipolysis-associated genes were linked to a different set of pathways (results not shown). Network analysis provide little evidence of connection between genes associated with insulin-stimulated lipogenesis or lipolysis (ESM Figs 1, 2). PPARG was the only FSI-associated gene with several indirect connections to other FSI-associated genes, pointing to a weak functional connection between FSI-associated genes (ESM Fig. 3). Bearing this in mind, we continued to evaluate the SNPs and candidate genes for FSI one at a time.

Linking candidate genes for FSI to WAT function by eQTL analysis and siRNA knockdown

To further link candidate genes from GWAS to WAT function, we used in silico analysis to determine whether tag-SNPs for each of the 17 FSI- or FSIadjBMI-associated loci (ESM Table 1) comprised cis eQTLs. According to GTEx, eight genes in four different genetic loci demonstrate genotype-specific expression (Table 3). At three of these loci, WAT gene expression associated with FSI and adipose phenotypes (FDR <5%). At the fourth locus, UHRF1BP1 was nominally associated with adipose morphology. According to the SNP annotation tool SNPnexus, three of the SNPs are intronic and the fourth intergenic (Table 3). None of the SNPs has any regulatory function ascribed to them.

Table 3.

SNPs containing cis eQTLs

| Chr | SNP | Locus for FSI GWAS | eQTLa | FSIb | Lipolysisb | Insulin-stimulated lipogenesisb | WAT morphologyb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect allele | Gene | Effect allele | p value | Effect size | p value | R | p value | R | p value | R | p value | R | |||

| 2 | rs2972143 | Intergenic | G | IRS1 | G | 8.0 × 10−8 | −0.29 | 2.8 × 10−5c | – | 3.4 × 10−4c | + | 3.3 × 10−2 | – | ||

| 4 | rs3822072 | Intronic | A | FAM13A | G | 4.0 × 10−6 | 0.24 | 5.6 × 10−12c | – | 5.6 × 10−7c | – | 1.6 × 10−2 | + | 8.2 × 10−4c | – |

| 6 | rs6912327 | Intronic | T | UHRF1BP1 | C | 2.0 × 10−25 | 0.51 | 1.1 × 10−2 | – | ||||||

| T | SNRPC | C | 3.3 × 10−10 | −0.28 | |||||||||||

| 7 | rs1167800 | Intronicd | A | STAG3L1 | A | 3.3 × 10−10 | −0.28 | ||||||||

| A | TRIM73 | A | 5.2 × 10−8 | −0.34 | 1.5 × 10−2c | – | |||||||||

| A | POM121C | A | 3.6 × 10−7 | −0.22 | 2.0 × 10−2c | – | 3.4 × 10−3c | + | 2.6 × 10−2 | – | |||||

| A | PMS2P3 | A | 6.1 × 10−11 | −0.41 | 8.0 × 10−3 | – | 4.8 × 10−2 | – | |||||||

aSAT eQTL according to GTEx portal

bMicroarray results from the clinical cohort were analysed by regression in QLUCORE, adjusting for array batch, and for WAT morphology, adjusting for age. Only results with p < 0.05 are shown

cFDR <5%

dIntronic in the HIP1 gene

R, regression coefficient, which can be either positive (+) or negative (−)

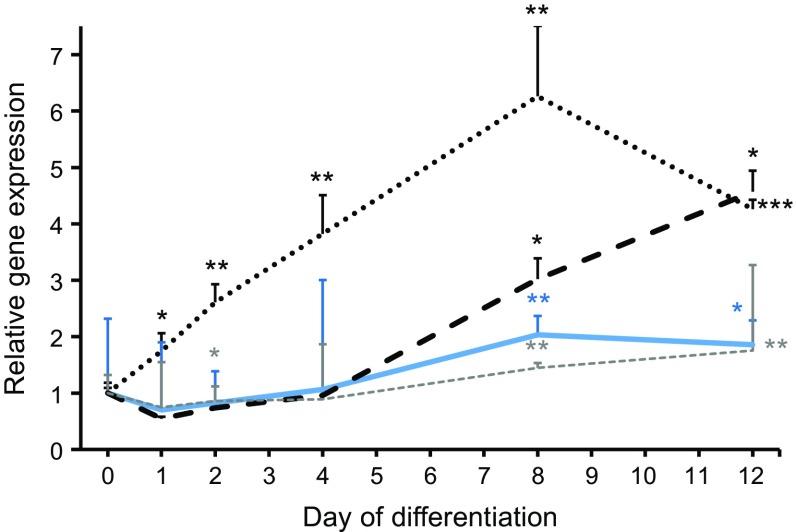

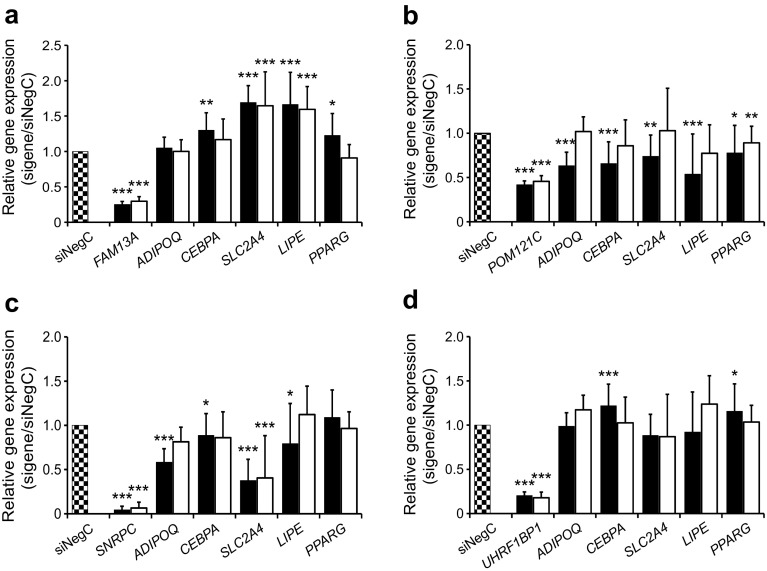

Four genes comprising eQTLs (FAM13A, UHRF1BP1, POM121C and SNPRC) were taken forward for functional evaluation in hMSCs to determine possible impact on adipocyte function. We first evaluated expression of the four genes during differentiation of hMSCs. The expression of FAM13A increased directly after induction of differentiation, whereas the expression of POM121C, UHRF1BP1 and SNRPC displayed detectable increases only at day 8 (Fig. 2). Based on these data, the genes were knocked down using siRNA in the hMSCs at day 4, corresponding to an early stage of differentiation. Three and eight days post-transfection (i.e. day 7 and 12 of differentiation), this resulted in a decreased expression of FAM13A, UHRF1BP1 and SNPRC by 70–95% and decreased expression of POM121C by 60% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Gene expression of FAM13A, POM121C, SNRPC and UHRF1BP1 were monitored using quantitative RT-PCR during differentiation of hMSCs to adipocytes in vitro from start of differentiation (day 0) until day 12. POM121C (solid blue line), FAM13A (dotted black line), UHRF1BP1 (dashed black line) and SNRPC (dashed grey line). Results were analysed using the paired t test and are presented as relative fold change+SD vs day 0. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs day 0

Fig. 3.

Expression of FAM13A (a), POM121C (b), SNRPC (c) and UHRF1BP1 (d) was knocked down using siRNA in hMSCs in vitro at day 4 of differentiation until day 7 and 12 of differentiation, upon which the expression of target and ADIPOQ, CEBPA, SLC2A4, LIPE and PPARG was monitored. We have performed three biological experiments with 3–4 technical replicates in each experiment; n = 11 technical replicates for NegC; n = 12 technical replicates for target genes. Results were analysed using the paired t test and are presented as relative fold change±SD vs negative control (NegC) at each time point during differentiation. Black bars, day 7; white bars, day 12. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs NegC

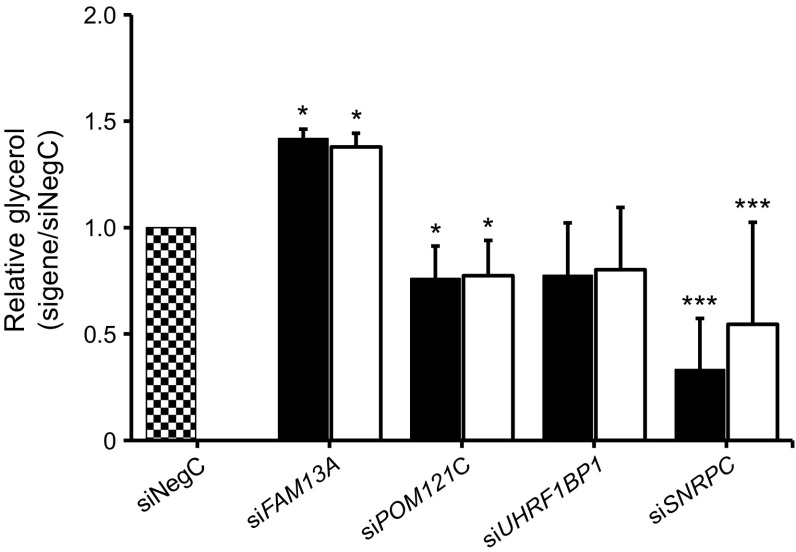

Expression levels of adipocyte-enriched genes central to adipogenesis (PPARG, CEBPA), lipolysis (LIPE) and insulin sensitivity (SLC2A4, ADIPOQ) were measured in each knockdown experiment. Knockdown of FAM13A increased expression of LIPE, SLC2A4, PPARG and CEBPA (Fig. 3a). We also evaluated levels of glycerol in the conditioned medium as a marker for lipolysis. Glycerol levels increased significantly, by approximately 1.5-fold, indicating an increased lipolysis (Fig. 4). As FAM13A expression increased from the very beginning of differentiation, we also knocked down FAM13A one day prior to induction of differentiation (day −1) and this had a similar effect on adipocyte-specific gene expression (results not shown). POM121C knockdown resulted in significantly reduced expression of all investigated genes (Fig. 3b) and reduced glycerol release (Fig. 4). Knockdown of SNRPC resulted in strongly reduced expression of ADIPOQ and SLC2A4, as well as modestly decreased expression of LIPE and CEBPA (Fig. 3c). The glycerol level in the medium was significantly reduced, which is in line with gene expression data (Fig. 4). UHRF1BP1 knockdown resulted in a temporary and modest increase in the expression of PPARG and CEBPA, with no effect on glycerol release in medium. Four eQTL genes were excluded from the functional evaluation in vitro: IRS1 because its function is already defined; PMS2P3, TRIM73 and STAG3L1 since commercial siRNAs reagents were unavailable, or because the genes were expressed at low levels in adipocytes or below the detection threshold in WAT.

Fig. 4.

Expression of FAM13A, POM121C, SNRPC and UHRF1BP1 was knocked down using siRNA in hMSCs in vitro and glycerol levels in conditional medium were evaluated. We have performed 3 biological experiments with 3–4 technical replicates in each experiment; n = 11 technical replicates for NegC; n = 12 technical replicates for target genes. Results were analysed using the paired t test and are presented as relative fold change±SD vs non-targeting siRNA pool (siNegC). Black bars, day 7; white bars, day 12. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 vs NegC

Discussion

To explore the role of WAT in the genetic predisposition to systemic IR we have analysed adipose expression of 120 candidate genes in genetic loci associated with FSI and FSIadjBMI. We report that adipose expression of a surprisingly high number of these genes (48; 40%) associate with FSI and with fat cell insulin sensitivity or lipolysis (35; 30%). These findings give support to the notion that WAT is an important organ mediating the effects of genetic variants on FSI. Furthermore, functional analysis in vitro by siRNA-mediated knockdown highlighted FAM13A and POM121C as potential causal links between SNPs and IR at specified GWAS loci. None of these genes have to our knowledge previously been implicated in WAT function in humans.

At one chromosome 4 locus (rs3822072), the FSI-associated allele is associated with lower FAM13A expression. Consistent with a protective role of FAM13A on IR, we show that FAM13A expression is associated with a beneficial metabolic profile, including decreased WAT lipolysis, and that FAM13A knockdown increases lipolysis and expression of LIPE, which is a rate-limiting enzyme in lipolysis [27]. We previously showed that basal lipolytic activity is a strong determination of insulin sensitivity [20]. The increased expression of other genes with central functions in adipogenesis and adipocytes (e.g. PPARG, CEBPA and SLC2A4) following FAM13A knockdown indicate that FAM13A has the potential to inhibit adipogenesis; however, the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear. The precise molecular mechanisms linking FAM13A to lipolysis are unknown. FAM13A has previously been reported to induce fatty acid oxidation, autophagia via activation of Akt and β-catenin degradation in various cell types [28–30]. Akt controls lipolysis [31] and could hypothetically be involved in FAM13A inhibition of lipolysis; however, detailed mechanistic studies are beyond the scope of this investigation.

At the chromosome 7 locus (rs1167800), the FSI-associated allele is associated with lower POM121C expression. Consistent with an insulin-sensitising function, POM121C expression is positively associated with systemic and adipocyte insulin sensitivity and with adipose hyperplasia. Adipose hypertrophy has previously been linked to impaired adipogenesis and IR [8]. POM121C knockdown early in the adipogenesis caused decreased expression of all adipocyte-specific markers suggesting that POM121C is necessary for adipocyte differentiation. We observed reduced glycerol release following POM121C knockdown. This is probably secondary to impaired adipogenesis (i.e. without functional adipocytes there is no lipolysis). POM121C encodes a nucleoporin and forms an important component of the nuclear pore complexes [32]; it has to our knowledge previously not been implicated in human metabolic disease.

At one chromosome 6 locus (rs6912327), the effects observed after siRNA-mediated knockdown of SNRPC and UHRF1BP1 did not suggest that these genes underlie genetic control of FSI at this locus. Thus, the FSI-associated allele is associated with higher SNPRPC expression, suggesting that SNRPC contributes to metabolic disease. However, SNPRPC knockdown reduced expression of ADIPOQ, encoding the insulin-sensitising hormone adiponectin, and SLC2A4, encoding the glucose transporter GLUT4; these findings are consistent with an insulin-sensitising function of SNRPC. Lipolysis was also reduced, potentially secondary to impaired lipid accumulation. Knockdown of UHRF1BP1 had marginal effects on adipocyte markers, suggesting that UHRF1BP is not a causative gene for FSI. Of note, expression of neither UHRF1BP nor SNPRPC was associated with WAT variables with FDR <5%.

The present study has several limitations. The investigated genomic regions are based on distance and not linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns and we cannot exclude that genes with more distal cis-eQTL effects might play a role in WAT function. To our knowledge, however, no reliable LD data are available for this Swedish population. Furthermore, in Ensemble (www.ensemble.org, accessed 22 November 2017) we did not find any non-synonymous, or otherwise likely functional, SNPs in high LD (r2 ≥ 0.9) with rs3822072 or rs1167800. Another limitation is that we studied women only and our results cannot be generalised to the entire population. The analysis was limited to abdominal subcutaneous WAT and the results, thus, cannot be generalised to other WAT depots. The relative importance of subcutaneous vs visceral WAT for IR is debatable. It is notable that removal of the greater omentum in addition to bariatric surgery is not associated with metabolic benefits after long-term follow-up, pointing to the limited importance of visceral WAT for metabolic disease in this population [33].

Only a few of the candidate genes for FSI shown in Table 2 were taken forward for functional evaluation. Beyond FAM13A and POM121C, however, a few of the genes in Table 2 have functions ascribed to them which support the notion that they might influence the metabolic function of WAT and systemic IR: PPARG and IRS1 control adipogenesis and insulin signalling, respectively [34, 35]; MAP3K1 and TCF7L2 are involved in Wnt signalling [36, 37], which inhibits adipogenesis; GRB14 is directly involved in insulin signalling [38] and ARL15 is encoded in a major genetic locus controlling adiponectin levels [39]. However, information about function is lacking for most of the genes in Table 2, making it difficult to define networks based on functional connectivity between the genes.

Many genetic variants seem to have pleiotropic effects on metabolic traits [11]. The genetic locus on chromosome 4 harbouring FAM13A has previously been linked to body fat distribution [40], and the chromosome 7 locus harbouring POM121C has been linked to BMI [41]. Thus, it is possible that the impact of these genes on lipolysis and adipogenesis is important for development of obesity as well. At the same time, the observation that several of the examined genes are associated with more than one studied phenotype emphasizes the functional connection between studied phenotypes (e.g. large fat cells are insulin resistant and display enhanced spontaneous lipolysis [8]).

In conclusion, gene expression and adipocyte functional studies support the notion that FAM13A and POM121C control adipocyte lipolysis and adipogenesis, respectively, and might thereby be involved in genetic control of systemic insulin sensitivity and, possibly, fat accumulation.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 375 kb)

(XLSX 50 kb)

Acknowledgements

The skilful technical support from research nurses K. Hertel and Y. Widlund and laboratory technicians K. Wåhlen, E. Dungner and G. Åström at the Lipid Laboratory, Karolinska Institutet is greatly appreciated. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH and NINDS. The data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the GTEx Portal (accessed 28 August 2016).

Contribution statement

ID formulated the hypothesis and designed the study. ID, VL, PA and AK contributed to acquisition of data. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. ID, VL and AK drafted the article. All authors participated in revising the article critically for important intellectual content and all approved the final version to be published. ID is the guarantor of this work.

Abbreviations

- eQTL

Expression quantitative trait locus

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- FSI

Fasting serum insulin

- FSIadjBMI

FSI adjusted for BMI

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- hMSC

Human mesenchymal stem cell

- IR

Insulin resistance

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- WAT

White adipose tissue

- WHRadjBMI

WHR adjusted for BMI

Funding

This study was supported by the SRP Diabetes program at Karolinska Institutet, CIMED, the Swedish Research Council, Stockholm County, Novo Nordic Foundation, EASD/Eli-Lilly Foundation, the Swedish Diabetes Foundation and the EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (EMIF grant no. 115372). The funding sources were not involved in study design or in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Tweet

The genes FAM13A and POM121C might be involved in genetic control of systemic insulin sensitivity in humans by controlling abdominal adipocyte function #genomics #GWAS

References

- 1.Laakso M. Is insulin resistance a feature of or a primary risk factor for cardiovascular disease? Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:105. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association (1998) Consensus development conference on insulin resistance. 5–6 November 1997. Diabetes Care 21: 310–314 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Langenberg C, Sharp SJ, Schulze MB, et al. Long-term risk of incident type 2 diabetes and measures of overall and regional obesity: the EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kloting N, Bluher M. Adipocyte dysfunction, inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weyer C, Foley JE, Bogardus C, Tataranni PA, Pratley RE. Enlarged subcutaneous abdominal adipocyte size, but not obesity itself, predicts type II diabetes independent of insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1498–1506. doi: 10.1007/s001250051560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lonn M, Mehlig K, Bengtsson C, Lissner L. Adipocyte size predicts incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. FASEB J. 2010;24:326–331. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-133058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis: the missing links. The Claude Bernard Lecture 2009. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1270–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1684-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao H, Mejhert N, Fretz JA, et al. Early B cell factor 1 regulates adipocyte morphology and lipolysis in white adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2014;19:981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arner P, Langin D. Lipolysis in lipid turnover, cancer cachexia, and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrannini E, Natali A, Bell P, Cavallo-Perin P, Lalic N, Mingrone G. Insulin resistance and hypersecretion in obesity. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1166–1173. doi: 10.1172/JCI119628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet. 2012;44:991–1005. doi: 10.1038/ng.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlman I, Ryden M, Brodin D, Grallert H, Strawbridge RJ, Arner P. Numerous genes in loci associated with body fat distribution are linked to adipose function. Diabetes. 2016;65:433–437. doi: 10.2337/db15-0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heid IM, Jackson AU, Randall JC, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet. 2010;42:949–960. doi: 10.1038/ng.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lofgren P, Andersson I, Adolfsson B, et al. Long-term prospective and controlled studies demonstrate adipose tissue hypercellularity and relative leptin deficiency in the postobese state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6207–6213. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolaczynski JW, Morales LM, Moore JH, Jr, et al. A new technique for biopsy of human abdominal fat under local anaesthesia with lidocaine. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994;18:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodbell M, Krishna G. Preparation of isolated fat cells and fat cell ‘ghosts’; methods for assaying adenylate cyclase activity and levels of cyclic AMP. Methods Enzymol. 1974;31:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)31010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lofgren P, Hoffstedt J, Naslund E, Wiren M, Arner P. Prospective and controlled studies of the actions of insulin and catecholamine in fat cells of obese women following weight reduction. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2334–2342. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsch J, Gallian E. Methods for the determination of adipose cell size in man and animals. J Lipid Res. 1968;9:110–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersson DP, Arner E, Hogling DE, Ryden M, Arner P. Abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue cellularity in men and women. Int J Obes. 2017;41:1564–1569. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girousse A, Tavernier G, Valle C, et al. Partial inhibition of adipose tissue lipolysis improves glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity without alteration of fat mass. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arner P, Engfeldt P. Fasting-mediated alteration studies in insulin action on lipolysis and lipogenesis in obese women. Am J Phys. 1987;253:E193–E201. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.2.C193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chelala C, Khan A, Lemoine NR. SNPnexus: a web database for functional annotation of newly discovered and public domain single nucleotide polymorphisms. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:655–661. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettersson AM, Stenson BM, Lorente-Cebrian S, et al. LXR is a negative regulator of glucose uptake in human adipocytes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2044–2054. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiao H, Kulyte A, Naslund E, et al. Whole exome sequencing suggests LAMB3 as a susceptibility gene for morbid obesity. Diabetes. 2016;65:2980–2989. doi: 10.2337/db16-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-ΔΔCT) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arner E, Mejhert N, Kulyte A, et al. Adipose tissue microRNAs as regulators of CCL2 production in human obesity. Diabetes. 2012;61:1986–1993. doi: 10.2337/db11-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryden M, Jocken J, van Harmelen V, et al. Comparative studies of the role of hormone-sensitive lipase and adipose triglyceride lipase in human fat cell lipolysis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1847–E1855. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00040.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Z, Knudsen NH, Wang G, et al. Genetic control of fatty acid beta-oxidation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:738–748. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0282OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li R, Tan S, Yu M, Jundt MC, Zhang S, Wu M. Annexin A2 regulates autophagy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection through the Akt1-mTOR-ULK1/2 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2015;195:3901–3911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Z, Lao T, Qiu W, et al. A chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility gene, FAM13A, regulates protein stability of β-catenin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:185–197. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0999OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi SM, Tucker DF, Gross DN, et al. Insulin regulates adipocyte lipolysis via an Akt-independent signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5009–5020. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00797-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito H, Takeuchi H, Masuda T, Noda T, Yamaoka S. N-terminally truncated POM121C inhibits HIV-1 replication. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson DP, Eriksson-Hogling D, Backdahl J, et al. Omentectomy in addition to bariatric surgery-a 5-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1115–1118. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2576-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun XJ, Miralpeix M, Myers MG, Jr, et al. Expression and function of IRS-1 in insulin signal transmission. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22662–22672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, et al. PPARγ is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–617. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science. 2000;289:950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sue Ng S, Mahmoudi T, Li VS, et al. MAP3K1 functionally interacts with Axin1 in the canonical Wnt signalling pathway. Biol Chem. 2010;391:171–180. doi: 10.1515/bc.2010.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasus-Jacobi A, Perdereau D, Auzan C, et al. Identification of the rat adapter Grb14 as an inhibitor of insulin actions. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26026–26035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richards JB, Waterworth D, O'Rahilly S, et al. A genome-wide association study reveals variants in ARL15 that influence adiponectin levels. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, et al. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518:187–196. doi: 10.1038/nature14132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 375 kb)

(XLSX 50 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.