Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) remains one of the leading causes of reduced lifespan in diabetes. The quest for both prognostic and surrogate endpoint biomarkers for advanced DKD and end-stage renal disease has received major investment and interest in recent years. However, at present no novel biomarkers are in routine use in the clinic or in trials. This review focuses on the current status of prognostic biomarkers. First, we emphasise that albuminuria and eGFR, with other routine clinical data, show at least modest prediction of future renal status if properly used. Indeed, a major limitation of many current biomarker studies is that they do not properly evaluate the marginal increase in prediction on top of these routinely available clinical data. Second, we emphasise that many of the candidate biomarkers for which there are numerous sporadic reports in the literature are tightly correlated with each other. Despite this, few studies have attempted to evaluate a wide range of biomarkers simultaneously to define the most useful among these correlated biomarkers. We also review the potential of high-dimensional panels of lipids, metabolites and proteins to advance the field, and point to some of the analytical and post-analytical challenges of taking initial studies using these and candidate approaches through to actual clinical biomarker use.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00125-018-4567-5) contains a slideset of the figures for download, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Biomarker, Diabetic kidney disease, Epidemiology, Nephropathy, Review

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) and its most severe manifestation, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), remains one of the leading causes of reduced lifespan in people with diabetes [1]. Even early stages of DKD confer a substantial increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1, 2], so the therapeutic goal should be to prevent these earlier stages, not just ESRD. However, there has been an impasse in the development of drugs to reverse DKD, with many Phase 3 clinical trial failures [3]. The current hard endpoints for the licencing of drugs for chronic kidney disease (CKD) or DKD approved by most authorities, including the US Food and Drug Administration, are a doubling of serum creatinine or the onset of ESRD or renal death. Some of the trial failures are due to insufficient power, with low overall rates of progression to these hard endpoints during the typical trial duration of 3–7 years. As a result, there is increasing interest in the development of prognostic or predictive biomarkers to allow for risk stratification into clinical trials, as well as eventually for targeting preventive therapy. There is also interest in the development of biomarkers of drug response that are surrogates for these harder endpoints. Here we review some of the larger studies published in the last 5 years on prognostic or predictive biomarkers for DKD. Our emphasis is on illustrating some key aspects of the approaches being used recently and what further improvements are needed, rather than systematically reviewing every sporadic biomarker report.

Biomarkers currently in use

It is well established that the best predictor of future ESRD is the current GFR and past GFR trajectory [4]. Thus, GFR is the most common prognostic biomarker being used for predicting ESRD in both clinical practice and in trials. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equations, both based on serum creatinine, are commonly used to estimate GFR. The difference in accuracy for staging between CKD-EPI and MDRD is slight, with 69% vs 65% overall accuracy for given stages being found in one study [5]. Serum cystatin C-based eGFR has been proposed as advantageous since, unlike creatinine, it is not related to muscle mass. Equations based on cystatin C overestimated directly measured GFR, while equations based on serum creatinine underestimated GFR in a large study [6]. Others have found that creatinine agrees more closely than cystatin C with directly measured GFR [7]. In those with and without diabetes, cystatin C predicts CVD mortality and ESRD better than eGFR does [8, 9]. However, this may be because factors other than renal function that affect ESRD risk, including diabetes, might also affect serum cystatin C levels, rather than because cystatin C-based eGFR is more accurately measuring GFR itself [10].

Albuminuria strongly predicts progression of DKD but it lacks specificity and sensitivity for ESRD and progressive decline in eGFR. In type 2 diabetes a large proportion of those who have renal disease progression are normoalbuminuric [11, 12]. It has been shown that the coexistence of albuminuria makes DKD rather than non-diabetic CKD more likely in people with type 2 diabetes [13]. However, even in type 1 diabetes, where non-diabetic CKD is much less common, albuminuria was reported to have a poor positive predictive value for DKD as only about a third of those with microalbuminuria had progressive renal function decline [14]. Albumin excretion also had low sensitivity, as only about half of those with progressive renal function decline were albuminuric [14]. Clearly, in evaluating the predictive performance of novel biomarkers, investigators should adjust for baseline eGFR and albuminuria. Historical eGFR data are not always routinely available. Nonetheless, it is important where possible to evaluate whether biomarkers improve prediction on top of historical eGFR.

Clinical predictors of DKD in type 1 and type 2 diabetes

Apart from albuminuria and eGFR, other risk factors routinely captured in clinical records can predict GFR decline. These have been systematically well reviewed elsewhere [15]. In brief, established clinical risk factors include age, diabetes duration, HbA1c, systolic BP (SBP), albuminuria, prior eGFR and retinopathy status. However, there have been relatively few attempts to build and validate predictive equations using clinical data that would form the basis for evaluating the marginal improvement in prediction with biomarkers [16–18]. Those that have attempted this reported C statistics for ESRD or renal failure death or prediction of incident albuminuria in the range 0.85–0.90 in type 2 diabetes [17, 18]. In the Joslin cohorts with type 1 diabetes, eGFR slope, albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) and HbA1c had a C statistic (not cross-validated) for ESRD of 0.80 [19–21]. In the FinnDiane cohort the best model had a C statistic of 0.67 for ESRD [22]. In the Steno Diabetes Center cohort, HbA1c, albuminuria, haemoglobin, SBP, baseline eGFR, smoking, and low-density lipoprotein/high-density lipoprotein ratio explained 18–25% of the variability in decline [23]. In the EURODIAB cohort predictive models for albuminuria included HbA1c, AER, waist-to-hip ratio, BMI and ever smoking with a non-cross-validated C statistic of 0.71 [24].

In summary, most studies have reported at least modest C statistics for models that contain clinical risk factors beyond eGFR, albuminuria status and age for renal outcomes in type 1 and 2 diabetes. However, despite this, very few biomarker studies have evaluated the marginal improvement in prediction beyond such factors. In the SUrrogate markers for Micro- and Macro-vascular hard endpoints for Innovative diabetes Tools (SUMMIT) study, for example, while forward selection of biomarkers on top of a limited set of clinical covariates selected a panel of 14 biomarkers as predictive, increasing the C statistic from 0.71 to 0.89, a more extensive clinical risk factor model already had a C statistic of 0.79 and a panel of only seven biomarkers showed an improvement in prediction beyond this [25].

Novel biomarker studies

Ideally, we seek predictive or prognostic biomarkers of the hard endpoint demanded by drug regulatory agencies (i.e. doubling of serum creatinine or the onset of ESRD or renal death). In practice, since many cohorts do not have the necessary length of follow-up or numbers of incident hard endpoints, many studies have sought biomarkers of intermediate phenotypes such as incident albuminuria, DKD stage 3 or eGFR slopes above a certain threshold (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main studies on biomarkers and DKD published between 2012 and 2017

| Author, ref. | Sample size and population | Study design | DKD stage | Biomarkers | Main results | Adjustments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single biomarkers or several biomarkers not as a panel | ||||||

| Burns et al [102] | N = 259 (n = 194 T1D, n = 65 controls) | Cross-sectional | Normoalbuminuria; varying levels of GFR | Urinary angiotensinogen and ACE2 levels, activity of ACE and ACE2 | Urinary angiotensinogen and ACE activity associated with ACR | No adjustments |

| Velho et al [44] |

N = 986 T1D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion and GFR | Plasma copeptin | Upper tertiles of copeptin associated with a higher incidence of ESRD | Baseline sex, age, and duration of diabetes |

| Carlsson et al [103] |

N = 607 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion | Plasma endostatin | Endostatin levels associated with increased risk of GFR decline and mortality | Baseline age, sex, eGFR and ACR |

| Dieter et al [104] |

N = 135 T2D |

Prospective | Proteinuria | Serum amyloid A | Higher serum amyloid A levels predicted higher risk of death and ESRD | UACR, eGFR, age, sex and ethnicity |

| Wang et al [105] | N = 100 (n = 80 with T2D, n = 20 healthy controls) | Cross-sectional | Varying levels of eGFR and ACR | Serum and urinary ZAG | Serum and urinary ZAG associated with eGFR and UACR, respectively | No adjustments |

| Pikkemaat et al [47] | N = 161 T2D | Prospective | eGFR >60 ml min−1 1.73 m−2 | Copeptin | Copeptin predicted development of CKD stage 3, borderline significant on adjustment for baseline eGFR | Age, sex, diabetes duration, antihypertensive treatment, HbA1c, BMI, SBP |

| Garg et al [50] |

N = 91 T2D (including n = 30 with prediabetes) |

Cross-sectional | Varying levels of albumin excretion | Urinary NGAL and cystatin C | NGAL and cystatin C were significantly higher in participants with vs those without microalbuminuria | No adjustments |

| Viswanathan et al [52] | N = 78 (n = 65 T2D, n = 13 controls) | Cross-sectional | Varying degrees of albuminuria | Urinary L-FABP | L-FABP inversely associated with eGFR and positively associated with protein to creatinine ratio | No adjustments |

| Panduru et al [62] |

N = 1573 T1D |

Prospective + Mendelian randomisation |

Varying degrees of albuminuria | Urinary KIM-1 | KIM-1 did not predict progression to ESRD independently of AER Mendelian randomisation supported a causal link between KIM-1 and eGFR |

HbA1c, triacylglycerols, AER |

| Pavkov et al [31] |

N = 193 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion, eGFR: ≥60 ml/min in 89% participants |

Serum TNFR1 and TNFR2 | Elevated concentrations of TNFR1 or TNFR2 associated with increased risk of ESRD | Age, sex, HbA1c, MAP, ACR and GFR |

| Fufaa et al [106] |

N = 260 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion and eGFR | Urinary KIM-1, L-FABP, NAG and NGAL | NGAL and L-FABP independently associated with ESRD and mortality | Baseline age, sex, diabetes duration, hypertension, HbA1c, GFR, ACR |

| Bouvet et al [107] |

N = 36 T2D |

Cross-sectional | Normoalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria | Urinary NAG | Higher NAG levels associated with microalbuminuria | No adjustments |

| Har et al [40] |

N = 142 T1D |

Cross-sectional | Varying levels of eGFR Normoalbuminuria |

Urinary cytokines/chemokines | Increased urinary cytokine/chemokine excretion according to filtration status with highest levels in hyperfiltering individuals, although not significant after adjustments | Glycaemia |

| Petrica et al [108] | N = 91 (n = 70 T2D, n = 21 controls) | Cross-sectional | Normoalbuminuria and microalbuminuria | Urinary α1-microglobulin and KIM-1 (proximal tubule markers), nephrin and VEGF (podocyte markers), AGE, UACR and serum cystatin C | Significant association between biomarkers of proximal tubule dysfunction and podocyte biomarkers (independently of albuminuria and renal function) | UACR, cystatin C, CRP |

| Wu et al [109] |

N = 462 T2D |

Cross-sectional | Varying levels of albumin excretion | Serum Klotho, NGAL, 8-iso-PGF2α, MCP-1, TNF-α, TGF-β1 | Klotho and NGAL associated with ACR | No adjustments |

| Sabbisetti et al [58] |

N = 124 T1D |

Prospective | Proteinuria CKD 1-5 |

Serum KIM-1 | KIM-1 associated with eGFR slopes and progression to ESRD | Baseline ACR, eGFR, and HbA1c |

| Velho et al [45] |

N = 3101 T2D |

Prospective | Albuminuria | Plasma copeptin | Copeptin independently associated with renal events (doubling of creatinine or ESRD) | Baseline sex, age, diabetes duration, hypertension, diuretics use, HbA1c, eGFR, triacylglycerols, HDL-cholesterol, AER |

| do Nascimento et al [110] |

N = 101 (n = 19 prediabetes, n = 67 diabetes [T1D, T2D] and n = 15 controls) |

Cross-sectional | Varying levels of albumin excretion | Urinary mRNA levels of podocyte-associated proteins (nephrin, podocin, podocalyxin, synaptopodin, TRPC6, α-actinin-4 and TGF-β1) | Urinary nephrin discriminated between the different stages of DKD and predicted increases in albuminuria | No adjustments |

| Boertien et al [46] |

N = 1328 T2D |

Prospective | Varying degrees of albuminuria and eGFR | Copeptin | Copeptin associated with change in eGFR independently of baseline eGFR. This association not present in those on RASi | Age, sex, diabetes duration, antihypertensive use, HbA1c, cholesterol, BP,BMI, smoking |

| Lopes-Virella et al [33] |

N = 1237 T1D |

Prospective | Normoalbuminuria | Serum E-selectin, IL-6, PAI-1, sTNFR1, TNFR2 | TNFR1 and TNFR2 and E-selectin best predictors of progression to macroalbuminuria | Treatment allocation, baseline AER, ACEi/ARB use, retinopathy cohort, sex, age, HbA1c, diabetes duration |

| Panduru et al [111] | N = 2454 (n = 2246 T1D, n = 208 controls) | Prospective | Varying degrees of albuminuria | Urinary L-FABP | L-FABP was an independent predictor of progression at all stages of DKD, but L-FABP did not significantly improve risk prediction above AER | Baseline WHR, HbA1c, triacylglycerols, ACR |

| Araki et al [53] |

N = 618 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion, serum creatinine ≤ 8.8×10−2 mmol/l | Urinary L-FABP | L-FABP associated with decline in eGFR | Age, sex, BMI, HbA1c, cholesterol, triacylglycerols, HDL-cholesterol, hypertension, RASi use, BP |

| Lee et al [112] |

N = 380 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion | Plasma TNFR1 and FGF-23 | FGF-23 was associated with increased risk of ESRD, only in unadjusted model | Sex, baseline diabetes duration, HbA1c, eGFR, AER |

| Cherney et al [41] |

N = 150 T1D |

Cross-sectional | Normoalbuminuria | 42 urinary cytokines/chemokines | IL-6, IL-8, PDGF-AA and RANTES levels differed across ACR tertiles | No adjustments |

| Conway et al [60] |

N = 978 T2D |

Prospective | Varying degrees of albuminuria and eGFR | Urinary KIM-1 and GPNMB | KIM-1 and GPNMB associated with faster eGFR decline, only in unadjusted models Higher KIM-1 associated with mortality risk, only in unadjusted models |

Baseline eGFR, ACR, sex, diabetes duration, HbA1c, BP |

| Nielsen et al [48] |

N = 177 T2D |

Prospective | Proteinuria | Urinary NGAL and KIM1 and plasma FGF23 | Higher levels of the biomarkers associated with a faster decline in eGFR, although this was not independent of known promoters | Age, sex, HbA1c, SBP and urinary albumin |

| Jim et al [113] | N = 76 (n = 66 T2D, n = 10 controls) | Cross-sectional | Normoalbuminuria and microalbuminuria | Urinary nephrin levels | Nephrinuria occurred before the onset of microalbuminuria | No adjustments |

| Gohda et al [30] |

N = 628 T1D |

Prospective | Normal renal function; normoalbuminuria and microalbuminuria | TNFR1 and TNFR2 | TNFR1 and TNFR2 strongly associated with risk for early renal decline | HbA1c, AER, and eGFR |

| Niewczas et al [29] |

N = 410 T2D |

Prospective | CKD 1-3 | Plasma TNF-α, TNFR1, and TNFR2, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PAI-1, IL-6 and CRP | TNFR1 and TNFR2 were strongly associated with risk of ESRD | Age, HbA1c, AER, and eGFR |

| Fu et al [49] | N = 112 (n = 88 with T2D, n = 24 controls) | Cross-sectional | Varying degrees of albuminuria | Urinary KIM-1, NAG, NGAL | Higher levels of the three markers in T2D than controls. Positive association of NGAL and NAG with ACR; negative association of NGAL and eGFR |

No adjustments |

| Nielsen et al [59] |

N = 63 T1D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion and GFR | Urinary NGAL, KIM-1 and L-FABP | Elevated NGAL and KIM-1 were associated with faster decline in GFR, but not after adjustments for known progression promoters | Age, sex, diabetes duration, BP, HbA1c, AER |

| Kamijo-Ikemori et al [51] | N = 552 (n = 140 T2D and n = 412 controls) | Cross-sectional and prospective | Varying degrees of albuminuria and GFR | Urinary L-FABP | L-FABP associated with progression of nephropathy | Age, sex, HbA1c, albuminuria status at baseline, BP |

| Vaidya et al [61] | N = 697 (n = 659 T1D, n = 38 controls) | Cross-sectional and prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion | Urinary IL-6, CXCL10/IP-10, NAG and KIM-1 | KIM-1 and NAG both individually and collectively were significantly associated with regression of microalbuminuria | Age, sex, AER, HbA1c, SBP, renoprotective treatment and cholesterol |

| Panel of biomarkers /proteomics signatures | ||||||

| Coca et al [114] | N = 1536 (n = 1346 T2D, n = 190 controls) | Nested case–control study and prospective | CKD at various stages | TNFR1, TNFR2 and KIM-1 | Higher levels of the three biomarkers associated with higher risk of eGFR decline in persons with early or advanced DKD | Clinical variables |

| Bjornstad et al [69] |

N = 527 T1D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion and eGFR | Plasma biomarkers | B2M, cystatin C, NGAL and osteopontin predicted impaired eGFR | Age, sex, HbA1c, SBP, LDL-cholesterol, baseline log ACR and eGFR |

| Peters et al [70] |

N = 354 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion and eGFR | Plasma ApoA4, ApoC-III, CD5L, C1QB, complement factor H-related protein 2, IGFBP3 | ApoA4, CD5L, C1QB and IBP3 improved the prediction of rapid decline in renal function independently of recognised clinical risk factors | Age, diabetes duration, diuretic use, HDL-cholesterol |

| Mayer et al [66] |

N = 1765 T2D |

Prospective | CKD at various stages | YKL-40, GH-1, HGF, matrix metalloproteinases: MMP2, MMP7, MMP8, MMP13, tyrosine kinase and TNFR1 | Biomarkers explained variability of annual eGFR loss by 15% and 34% (adj R2) in patients with eGFR ≥60 and <60 ml min−1 1.73 m−2 respectively. A combination of molecular and clinical predictors increased the adjusted R2 to 35% and 64% in these two groups, respectively. |

Sex, age, smoking, baseline eGFR, ACR, BMI, total cholesterol, BP and HbA1c |

| Saulnier et al [115] |

N = 1135 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion and eGFR | Serum TNFR1, MR-proADM and NT-proBNP | TNFR1, MR-proADM and NT-proBNP improved risk prediction for renal function decline | Age, sex, diabetes duration, HbA1c, BP, baseline eGFR and ACR |

| Looker et al [25] |

N = 307 (n = 154 T2D, n = 153 controls) |

Nested case–control | CKD 3 | 207 serum biomarkers | Panel of 14 biomarkers improved clinical prediction (from 0.706 to 0.868) | Age, sex, eGFR, albuminuria, HbA1c, ACEi and ARB use, BP, weighted average of past eGFRs, diabetes duration, BMI, prior CVD, insulin use, antihypertensive drugs |

| Pena et al [116] |

N = 82 T2D |

Prospective | Normoalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria | Plasma peptides | 18 peptides (related to PI3K-Akt, VEGF, mTOR, MAPK, and p38 MAPK, Wnt signalling) improved risk prediction for transition from micro to macroalbuminuria (C statistic from 0.73 to 0.80) | Baseline albuminuria status, eGFR, RASi use |

| Pena et al [64] |

N = 82 T2D |

Prospective | Varying levels of albumin excretion and eGFR | 28 biomarkers | MMPs, tyrosine kinase, podocin, CTGF, TNFR1, sclerostin, CCL2, YKL-40, and NT-proCNP improved prediction of eGFR decline when combined with established risk markers | Baseline smoking, sex, SBP, eGFR, use of oral diabetic medication |

| Foster et al [117] |

N = 250 T2D |

Prospective | Unselected but 54% albuminuric | β-Trace protein and B2M | β-Trace protein associated with ESRD | GFR, albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes duration, hypertension, cholesterol |

| Agarwal et al [67] | N = 87 (n = 67 T2D, n = 20 controls) | Prospective | CKD 2-4 Varying levels of albumin excretion |

17 urinary and 7 plasma biomarkers | Urinary C-terminal FGF-2: strongest association with ESRD Plasma VEGF associated with the composite outcome of death and ESRD |

Baseline albuminuria and eGFR |

| Siwy et al [75] |

N = 165 T2D |

Prospective | Wide ranges of eGFR and urinary albumin | Urinary CDK273 | Validation of this urinary proteome-based classifier in a multicentre prospective setting | Albuminuria |

| Verhave et al [68] |

N = 83 T1D and T2D |

Prospective | Overt diabetic nephropathy | Urinary IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, TNF-α, TGF-β1, and PAI-1 | MCP-1 and TGF-β1 were independent and additive to proteinuria in predicting the rate of renal function decline | Albuminuria |

| Bhensdadia et al [84] |

N = 204 T2D |

Prospective | eGFR stage 1-2 and normo-/macroalbuminuria | Urine peptides | Haptoglobin to creatinine ratio: best predictor of early renal function decline | Albuminuria, ACEi use |

| Merchant et al [82] |

N = 33 T1D |

Prospective | Microalbuminuria | Small (<3 kDa) plasma peptides | Plasma kininogen and kininogen fragments associated with renal function decline | No adjustments but stratum matched for eGFR and albuminuria |

| Roscioni et al [78] |

N = 88 T2D |

Prospective | Normoalbuminuria and microalbuminuria | CKD273 (urine) | Able to detect progression from normo- to micro- and micro- to macroalbuminuria | Baseline albuminuria status, eGFR, RASi use |

| Zürbig et al [76] |

N = 35 T1D and T2D |

Prospective | Normoalbuminuria; normal eGFR | Urinary CKD273 | Early detection of progression to macroalbuminuria: AUC 0.93 vs 0.67 for urinary albumin | Albuminuria |

| Titan et al [118] |

N = 56 T2D |

Prospective | Macroalbuminuria | Urinary RBP and serum and urinary cytokines (TGF-β, MCP-1 and VEGF) | Urinary RBP and MCP-1: independently related to the risk of CKD progression | Creatinine clearance, proteinuria, BP |

| Schlatzer et al [83] |

N = 465 T1D |

Nested case–control | CKD 1 Normoalbuminuria |

Panel of 252 urine peptides | A panel including Tamm–Horsfall protein, progranulin, clusterin, and α-1 acid glycoprotein improved the AUC from 0.841 (clinical variables) to 0.889 | Age, diabetes duration, HbA1c, BMI, WHR, smoking, total and HDL-cholesterol, SBP, ACR, uric acid, cystatin C, BP/lipid treatment |

| Metabolomics | ||||||

| Niewczas et al [119] |

N = 158 T1D |

Prospective | Proteinuria and CKD 3 | Global serum metabolomic profiling | 7 modified metabolites were associated with renal function decline and time to ESRD | Baseline HbA1c, ACR, eGFR, BP, BMI, smoking, uric acid levels, RASi use, other antihypertensive treatment, and statins |

| Klein et al [120] |

N = 497 T1D |

Prospective | Normoalbuminuria | Multiple plasma ceramide species and individual sphingoid bases and their phosphates | Increased plasma levels of very long chain ceramide species associated with reduced macroalbuminuria risk | Treatment group, baseline retinopathy, sex, HbA1c, age, AER, lipid levels, diabetes duration, ACEi/ARB use |

| Pena et al [121] |

N = 90 T2D |

Case–control and prospective | Normoalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria | Plasma and urinary metabolomics | Urine hexose, glutamine and tyrosine and plasma histidine and butenoylcarnitine associated with progression from micro- to macroalbuminuria | Albuminuria, eGFR, RASi use |

| Niewczas et al [122] |

N = 80 T2D |

Prospective nested case–control study |

CKD 1-3 | 78 plasma metabolites (uremic solutes) and essential amino acids | Abnormal levels of uremic solutes and essential amino acids associated with progression to ESRD | Albuminuria, eGFR, HbA1c |

| Sharma et al [123] |

N = 181 (n = 114 T2D, n = 44 T1D, n = 23 control) | Cross-sectional | Different CKD stages | 13 urine metabolites of mitochondrial metabolism | Differences in urine metabolome between healthy controls and diabetes mellitus and CKD cohorts | Age, race, sex, MAP,BMI, HbA1c, diabetes duration |

| Hirayama et al [124] |

N = 78 T2D |

Cross-sectional | Varying levels of albumin excretion | 19 serum metabolites | Able to discriminate presence or absence of diabetic nephropathy | No adjustments |

| Van der Kloet et al [125] |

N = 52 T1D |

Prospective | Normoalbuminuria | Metabolite profiles of 24 h urines | Acylcarnitines, acylglycines and metabolites related to tryptophan metabolism were discriminating metabolites for progression to micro or macroalbuminuria | No adjustments |

| Ng et al [126] |

N = 90 T2D |

Cross-sectional | Varying levels of eGFR | Octanol, oxalic acid, phosphoric acid, benzamide, creatinine, 3,5-dimethoxymandelic amide and N-acetylglutamine | Able to discriminate low vs normal eGFR | Age at diagnosis, age at examination, baseline serum creatinine |

| Han et al [127] | N = 150 (n = 120 T2D, n = 30 controls) | Cross-sectional | Varying levels of albumin excretion | 35 plasma non-esterified and 32 esterified fatty acids | Able to discriminate albuminuria status | No adjustments |

8-iso-PGF2α, 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α; ACEi, ACE inhibitors; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; Apo, apolipoprotein; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; B2M; β2-microglobulin; C1QB, complement C1q subcomponent subunit B; CD5L, CD5 antigen-like; CCL2, chemokine ligand 2; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CXCL10, CXC chemokine ligand-10; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; GPNMB, glycoprotein non-metastatic melanoma protein B; GH, growth hormone; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IGFBP3, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IP-10, inducible protein 10; L-FABP, liver-type fatty acid-binding protein; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MR-proADM, mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; NAG, N-acetylglucosamine; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NT-proCNP, N-terminal pro-C-type natriuretic peptide; P13K-Akt, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and protein kinase B; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PDGF-AA, platelet-derived growth factor-AA; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted; RASi, renin–angiotensin system inhibitor; RBP, retinol binding protein; SBP, systolic BP; sTNFR1, soluble TNF receptor-1; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TNFR, TNF receptor; TRPC6, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily member 6; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; YKL-40, chitinase-3-like protein 1; ZAG, zinc α2-glycoprotein

Studies testing single biomarkers or small sets of biomarkers

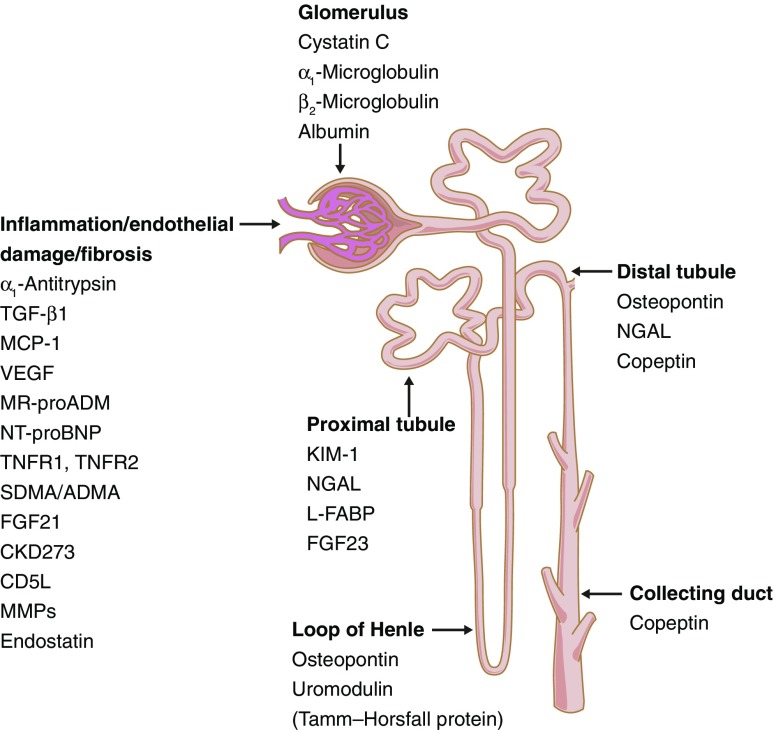

Most biomarker reports in the literature are of single candidate biomarkers or small sets of candidate biomarkers that may be assayed in single assays, usually ELISAs, or on multiplexed platforms, such as the Myriad RBM KidneyMAP panel (https://myriadrbm.com/, accessed 17 October 2017). Until recently, most of these studies have taken as their starting point molecules identified from in vitro studies, cell-based studies or animal models. For example, animal models identified kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) [26] and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) [27]. Candidates studied to date probe pathways thought causal in DKD, such as inflammation, glycation or glycosylation, or endothelial dysfunction. Others focus on glomerular features, such as glycocalyx abnormalities, extracellular matrix deposition, podocyte damage or glomerular fibrosis. Others focus on acute or chronic proximal or distal tubular dysfunction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Presumed site of origin of commonly associated biomarkers predictive of DKD. MMPs, matrix metalloproteases. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

As detailed in Table 1, among these studies of single or few biomarkers, some of the most frequently reported associations with DKD-relevant phenotypes are for biomarkers of inflammation and fibrosis pathways, such as soluble TNF receptors 1 and 2 (sTNFR1 and sTNFR2) [28–33], fibroblast growth factors 21 and 23 (FGF21, FGF23) [25, 34–41] and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) [42]. Positive associations have also been found for biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction, including mid-regional fragment of proadrenomedullin (MR-proADM) [43], and cardiac injury, including N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) [43]. Copeptin, a surrogate marker for arginine vasopressin, was associated with albuminuria progression and incident ESRD independently of baseline eGFR in four studies [44–47]. Proximal tubular proteins, such as urinary KIM-1, NGAL [48–50] and liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP) [51–53] have been associated with a faster decline in eGFR [48]. The data are most consistent for KIM-1, a protein expressed on the apical membrane of renal proximal tubule cells, with urinary concentrations rising in response to acute renal injury [49, 54–56]. Urinary and blood levels of KIM-1 increased across CKD stages and were associated with eGFR slopes and progression to ESRD during follow-up in some studies [57, 58], but it has not always been a strong independent predictor of progression [59, 60]. There are reports of its association with regression of microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes [61]. That these associations could reflect a causal role for KIM-1 was suggested by an analysis of the FinnDiane cohort with type 1 diabetes [62]. In this analysis, KIM-1 did not predict progression to ESRD independently of AER. However, using a Mendelian randomisation approach, based on genome-wide association study data for the KIM-1 gene, an inverse association of increased KIM-1 levels with lower eGFR emerged, suggesting a causal link with renal function.

Panels of candidate biomarkers

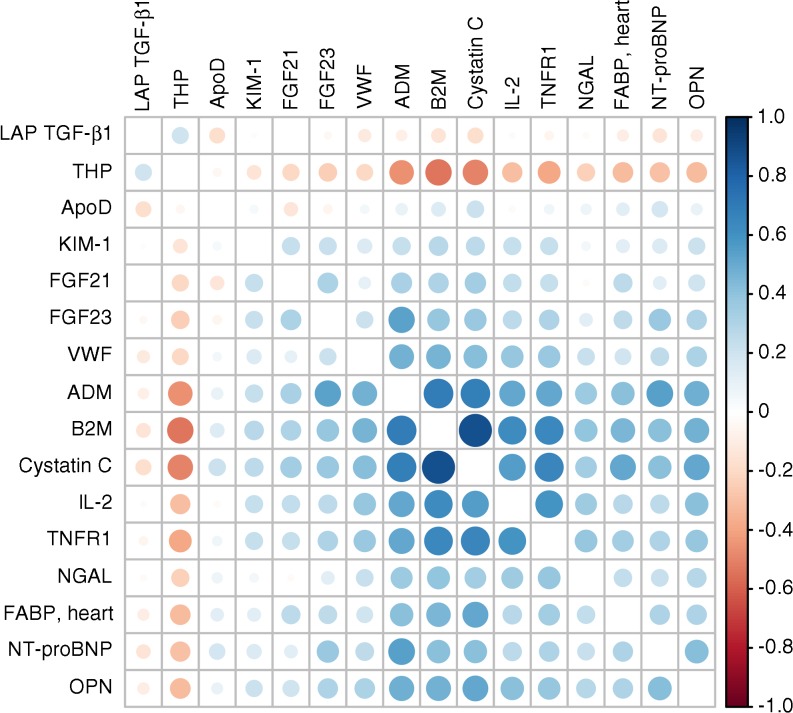

Each of the above biomarkers have some evidence supporting their prediction of renal function decline or other DKD-related phenotypes. However, although they have been investigated as reflecting specific pathways or processes, in reality there are very strong correlations between these biomarkers, even between different pathways. Figure 2 shows the correlation matrix for some of these from the SUMMIT study [25]. Yet, relatively few studies have assayed many of these candidates together to allow the marginal gain in prediction with each additional biomarker to be evaluated. Of those that have, some used a hybrid of discovery and candidate approaches harnessing bioinformatics and systems biology modelling techniques [63]. So, for example, in the SUMMIT study [25], we conducted both data mining and literature review to arrive at sets of candidates that several pathophysiological processes considered relevant for DKD. We assayed these but also a larger set of biomarkers (207 in total) that were already multiplexed with these candidates in the most efficient analysis platforms that were Luminex and mass spectrometry-based. Altogether, 30 biomarkers had highly significant evidence of association with renal function decline when examined singly and adjusted for historical and baseline eGFR, albuminuria and other covariates. In forward selection, 14 biomarkers were selected adjusting for this basic set of covariates (Table 1). On top of a more extensive set of covariates, seven biomarkers were selected: KIM-1, symmetric dimethylarginine/asymmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA/ADMA) ratio, β2-microglobulin (B2M), α1-antitrypsin, C16-acylcarnitine, FGF-21 and uracil.

Fig. 2.

Correlation matrix of biomarker measures in the SUMMIT project (www.imi-summit.eu/) showing there is high correlation between biomarkers that are of interest because of different pathway involvement. ADM, adrenomedullin; FABP, fatty acid-binding protein; LAP TGF-β1, latency-associated-peptide; OPN, osteopontin; THP, Tamm–Horsfall urinary protein; VWF, von Willebrand factor. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

Other such approaches are detailed in Table 1. Of particular note, the Systems biology towards novel chronic kidney disease diagnosis and treatment (SYSKID) consortium used data mining and de novo omics profiling to construct a molecular process model representation of CKD in diabetes [64], choosing ultimately to measure 13 candidates that represented the four largest processes of the model [65]. The panel that gave an increase in prediction of renal disease progression was then reported (C statistic increased from 0.835 to 0.896). In a recent validation study of nine of the biomarkers, the investigators reported that the panel was useful in prediction based on an increase in the adjusted r2 for the prediction model for eGFR progression from 29% and 56% for those with a baseline eGFR above and below 60 ml min 1.73 m−2, respectively, to 35% and 64%, respectively, for the biomarker panel on top of clinical variables [66].

In a study exploring 17 candidate urinary and seven plasma biomarkers in 67 participants with type 2 diabetes, Agarwal et al [67] found that urinary C-terminal FGF-2 showed the strongest association with ESRD, whereas plasma vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was associated with the composite outcome of death and ESRD. The analysis was adjusted for baseline eGFR only and ACR. Of a panel of seven candidates, Verhave et al found that urinary monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and TGF-β1 predicted renal function decline independently of albuminuria. Adjustment for baseline eGFR was not made as it surprisingly did not predict decline in univariate testing [68]. In the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study using Kidney Injury Panels 3 and 5, (Meso Scale Diagnostics, www.mesoscale.com/en/products/kidney-injury-panel-3-human-kit-k15189d/ accessed 08 January 2018) containing seven biomarkers, component 2 of a principal component analysis containing B2M, cystatin C, NGAL and osteopontin predicted incident impaired eGFR [69]. Recently, of eight candidate biomarkers studied after adjustment for clinical predictors, apolipoprotein A4 (ApoA4), CD5 antigen-like (CD5L), and complement C1q subcomponent subunit B (C1QB) independently predicted rapid decline in eGFR in 345 people with type 2 diabetes. A notable feature of this study was the adjustment for extensive clinical covariates [70].

Thus, there is some, but not complete, overlap in the explored and selected biomarkers in these panel studies so that further optimisation of a panel of the best reported biomarkers could be considered, especially if it focused on including biomarkers with low correlation with each other. It is also the case that all of the studies, including our own, are too small and there is a need for a large-scale collaboration to increase power, quantify prediction and to demonstrate generalisability [25].

Discovery ‘omic’ approaches

Apart from candidate biomarkers on multiplexed panels, global discovery or ‘hypothesis-free’ approaches measuring large sets of lipids, metabolites and amino acids, peptides and proteins are increasingly used [71]. The assay methods have most commonly used mass spectrometry-based approaches, but other proteomic methods are now also used [72, 73]. Here we describe some of the main ‘omic’ studies, focusing on whether associations are prospective and whether they have adjusted for baseline eGFR and other relevant covariates.

CKD273

This mass spectrometry-based method combines data on 273 urinary peptides into a score that has high accuracy in the cross-sectional classification of eGFR status [74] and has been developed as a commercial test by Mosaique Diagnostics (http://mosaiques-diagnostics.de/mosaiques-diagnostics/, accessed 18 October 2017). Most (74%) of the peptides are collagen fragments, with polymeric-immunoglobulin receptor, uromodulin (Tamm–Horsfall protein), clusterin, CD99 antigen, albumin, B2M, α1-antitrypsin and others comprising the remainder. The collagens, polymeric-immunoglobulin receptor, clusterin, CD99 antigen and uromodulin were lower with worse renal function, whereas the others were higher.

CKD273 was cross-sectionally associated with having albuminuria or/and eGFR <45 ml min−1 1.73 m−2 in individuals with type 2 diabetes [75]. In a small study (n = 35) of people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes the CKD273 score improved the C statistic for progression to albuminuria to 0.93 compared with 0.67 when using AER, but these data were not fully adjusted for baseline eGFR [76]. In 2672 participants from nine different cohorts, 76.3% with diabetes, CKD273 predicted rapid progression of eGFR better than AER [77]. In a nested case–control analysis, Roscioni et al reported a significant but smaller increase in C statistic for albuminuria incidence that was robust to adjustment for eGFR [78]. The most convincing data to date on the utility of CKD273 come from a subset of 737 samples obtained at baseline in the Diabetic Retinopathy Candesartan Trials (DIRECT)-Protect 2. The CKD273 score was strongly associated with incident microalbuminuria independently of baseline AER, eGFR and other variables. In this study, higher baseline eGFR was associated with incident microalbuminuria, an unusual finding, and CKD273 did not show the expected cross-sectional association with baseline eGFR [79]. Higher CKD273 score at baseline was associated with a larger reduction in ACR in the spironolactone group vs placebo (p = 0.026 for interaction) [80]. However, after adjustment for baseline ACR, the interaction between treatment and CKD273 was not statistically significant (p = 0.12). The concept that CKD273 will be useful in determining risk of disease progression and may also stratify treatment response to spironolactone is being more definitively tested in the ongoing Proteomic Prediction and Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System Inhibition Prevention Of Early Diabetic nephRopathy In TYpe 2 Diabetic Patients With Normoalbuminuria (PRIORITY) trial, of 3280 participants with type 2 diabetes [81].

Other proteomics

A nested case–control plasma proteomics study yielded kininogen and kininogen fragments as predictors of renal function decline. No adjustment was made for baseline eGFR but stratum matching was used [82]. Using a mass spectrometry approach on 252 urine peptides followed by ELISA validation in a nested case–control design, a panel including Tamm–Horsfall protein (also known as uromodulin), progranulin, clusterin and α-1 acid glycoprotein improved prediction of early decline in eGFR in a cohort of 465 adults with type 1 diabetes, but no adjustment was made for baseline eGFR [83]. In another urinary proteomics study with a very small initial discovery step and then single biomarker validation in 204 participants, haptoglobin emerged to be the best predictor of early renal functional decline but no adjustment for baseline eGFR was made [84].

Metabolomics

Several studies have also assessed the potential of metabolomics in the context of DKD. A recent systematic review [85] considered 12 studies (although all included control groups, most were cross-sectional), where a metabolomics-based approach was applied to identify potential biomarkers of DKD. The main metabolites were products of lipid metabolism (such as esterified and non-esterified fatty acids, carnitines, phospholipids), branch-chain amino acid and aromatic amino acid metabolism, carnitine and tryptophan metabolism, nucleotide metabolism (purine, pyrimidine), the tricarboxylic acid cycle or uraemic solutes. The meta-analysis highlighted differences in the results from studies included and this might be related to differences in study population, sample selection, analytical platform.

In the SUMMIT study we used mass spectrometry to measure low-molecular-weight metabolites, peptide and proteins (144 in all) as well as 63 proteins by ELISA and Luminex in a prospective design. Adjusted for extensive covariates, the arginine methylated derivatives of protein turnover ADMA and SDMA, and more strongly their ratio, were independently predictive of rapid progression of eGFR. This ratio, along with metabolites uracil, α1-antitrypsin and C-16 acylcarnitine, were included in the final panel of seven biomarkers [25].

In summary, there are too many global discovery studies in which prediction has not been properly assessed on top of available clinical data, such that replication of findings with proper adjustments is warranted.

Genetic biomarkers

Detailed reviews of the literature on genetic biomarkers of DKD have been recently published and are not the focus of this review [86]. In brief, a review of genetic discovery for DKD concluded that “the search for specific variants that confer predisposition to DKD has been relatively unrewarding” [86]. The effect sizes of the reported loci are very small in type 1 [87] and type 2 diabetes [88]. While international meta-analysis of data from the SUMMIT and other consortia are underway, given the effect sizes, it seems very unlikely that genetic risk scores for DKD will contribute usefully as biomarkers for use in the clinical prediction of DKD, even if they may reveal useful insights into pathogenesis.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

MiRNAs are small non-coding RNA, that block protein translation and can induce messenger RNA degradation, thereby acting as regulators of gene expression [89]. Several studies have assessed urinary and serum miRNA in participants with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in relation to different DKD stages [90–97]. These studies are mostly very small [95] and most have reported simply cross-sectional associations of urinary miRNAs with albuminuria status [91, 93–96]. Three studies have used a nested case–control within prospective cohort design, one of which was in pooled samples [90, 92, 97]. However, there is no overlap in the specific miRNAs being reported as being relevant to DKD. Taken altogether there is not convincing evidence as yet for a clinically useful role for miRNAs in the prediction of DKD progression.

Are any novel biomarkers actually being used yet?

In reality, despite all the attempts to develop novel prognostic biomarkers, few current trials use biomarkers other than albuminuria or eGFR as stratification variables or entry criteria. An exception is the PRIORITY trial [81], in which the CKD273 panel is being used to risk stratify people into a spironolactone vs placebo arm.

Biomarkers as surrogates of drug response is not the focus of this review but we note that there are also few trials using surrogate biomarkers as endpoints. One ongoing trial is using urinary proteomic panels as a surrogate outcome measure [98]. Another study includes urinary NGAL and KIM-1 as secondary outcome measures [99], and another is using N-acyl-β-d-glucosidase, B2M and cystatin C [100]. The SYSKID consortium have argued that past trials have shown that albuminuria/eGFR are insufficient to predict the individual’s response to renoprotective treatments in DKD, and that biomarkers more closely representing molecular mechanisms involved in disease progression and being targeted by therapies are needed [64]. Recently, Pena et al found that urinary metabolites previously shown to be at lower levels in those with DKD than without, decreased in the placebo arm of a trial but remained stable in the arm treated with the endothelin A receptor blocker atrasentan over a short, 12 week trial [101]. Further such studies of changes in biomarkers over time and in response to treatment are needed.

Future perspectives

In summary, despite the large number of reports in the literature, at present there are few validated biomarkers that have been clearly shown to substantially increase prediction of DKD-related phenotypes beyond known predictors. Few studies have attempted to estimate the marginal improvement in prediction beyond historical eGFR readings that can be expressed as the within-person slope or weighted average past eGFR, as we did in the SUMMIT study [25]. This is an important omission given the increasing availability of electronic healthcare records and potential for applying algorithms to such longitudinal clinical data more easily than measuring biomarkers. Even where some consistency in findings is observed, the extent of publication bias is unknown. Most importantly, biomarkers other than ACR and eGFR are not being routinely used to risk stratify individuals into trials or in clinical practice, despite considerable research investment into DKD biomarkers in recent years.

Large discovery panels have the potential to yield novel biomarkers, but progress has been hampered by small sample sizes, inadequate data analysis approaches (including failure to test the marginal increase beyond established risk factors) and lack of samples for replication. Futhermore, discovery approaches that yield panels of biomarkers measured on different platforms do not lend themselves to an easily implemented single panel in the clinical setting.

If this field is to be advanced, there is a need for a concerted effort to (1) generate and share data on the correlation between existing candidate biomarkers and biomarkers generated from available discovery platforms; (2) generate replication and validation sample and data sets that allow the best panel from available data to be defined; (3) harness the predictive information that exists in clinical records in the era of electronic health record data. Future discoveries should then be evaluated for their marginal prediction on top of clinical data and validated biomarkers.

Electronic supplementary material

(PPTX 333 kb)

Abbreviations

- ACR

Albumin to creatinine ratio

- ADMA

Asymmetric dimethylarginine

- ApoA4

Apolipoprotein A4

- B2M

β2-Microglobulin

- C1QB

Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B

- CD5L

CD5 antigen-like

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CKD273

CKD classifier based on 273 urinary peptides

- CKD-EPI

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DKD

Diabetic kidney disease

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- KIM-1

Kidney injury molecule-1

- L-FABP

Liver-type fatty acid-binding protein

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MDRD

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- MR-proADM

Mid-regional fragment of proadrenomedullin

- NGAL

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- NT-proNBP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- PRIORITY

Proteomic Prediction and Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System Inhibition Prevention Of Early Diabetic nephRopathy In TYpe 2 Diabetic Patients With Normoalbuminuria

- SBP

Systolic BP

- SDMA

Symmetric dimethylarginine

- SUMMIT

SUrrogate markers for Micro- and Macro-vascular hard endpoints for Innovative diabetes Tools

- SYSKID

Systems biology towards novel chronic kidney disease diagnosis and treatment

- TNFR

TNF receptor

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Contribution statement

Both authors were responsible for drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Both authors approved the version to be published.

Duality of interest

HMC’s institution has a patent co-filed for some of the biomarkers mentioned in this article.

References

- 1.Livingstone SJ, Levin D, Looker HC, et al. Estimated life expectancy in a Scottish cohort with type 1 diabetes, 2008-2010. JAMA. 2015;313:37–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingstone SJ, Looker HC, Hothersall EJ, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease and total mortality in adults with type 1 diabetes: Scottish registry linkage study. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan GCW, Tang SCW. Diabetic nephropathy: landmark clinical trials and tribulations. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:359–368. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RH, Hayakawa H, Mackay JD, Parsons V, Watkins PJ. Progression of diabetic nephropathy. Lancet. 1979;1:1105–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michels WM, Grootendorst DC, Verduijn M, Elliott EG, Dekker FW, Krediet RT. Performance of the Cockcroft-Gault, MDRD, and new CKD-EPI formulas in relation to GFR, age, and body size. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1003–1009. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06870909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, et al. Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: a pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:395–406. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barr EL, Maple-Brown LJ, Barzi F, et al. Comparison of creatinine and cystatin C based eGFR in the estimation of glomerular filtration rate in indigenous Australians: the eGFR Study. Clin Biochem. 2017;50:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menon V, Shlipak MG, Wang X, et al. Cystatin C as a risk factor for outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:19–27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krolewski AS, Warram JH, Forsblom C, et al. Serum concentration of cystatin C and risk of end-stage renal disease in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2311–2316. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 2009;75:652–660. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macisaac RJ, Jerums G. Diabetic kidney disease with and without albuminuria. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:246–257. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283456546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retnakaran R, Cull CA, Thorne KI, Adler AI, Holman RR. Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 74. Diabetes. 2006;55:1832–1839. doi: 10.2337/db05-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekinci EI, Jerums G, Skene A, et al. Renal structure in normoalbuminuric and albuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes and impaired renal function. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3620–3626. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krolewski AS. Progressive renal decline: the new paradigm of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:954–962. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radcliffe NJ, Seah J-M, Clarke M, MacIsaac RJ, Jerums G, Ekinci EI. Clinical predictive factors in diabetic kidney disease progression. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8:6–18. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keane WF, Brenner BM, de Zeeuw D, et al. The risk of developing end-stage renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: the RENAAL study. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1499–1507. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elley CR, Robinson T, Moyes SA, et al. Derivation and validation of a renal risk score for people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3113–3120. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jardine MJ, Hata J, Woodward M, et al. Prediction of kidney-related outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:770–778. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosolowsky ET, Skupien J, Smiles AM, et al. Risk for ESRD in type 1 diabetes remains high despite renoprotection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:545–553. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skupien J, Warram JH, Smiles AM, Stanton RC, Krolewski AS. Patterns of estimated glomerular filtration rate decline leading to end-stage renal disease in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:2262–2269. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skupien J, Warram JH, Smiles AM, et al. The early decline in renal function in patients with type 1 diabetes and proteinuria predicts the risk of end stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2012;82:589–597. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsblom C, Moran J, Harjutsalo V, et al. Added value of soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptor 1 as a biomarker of ESRD risk in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2334–2342. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrésdóttir G, Jensen ML, Carstensen B, et al. Improved prognosis of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;87:417–426. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vergouwe Y, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Zgibor J, et al. Progression to microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes: development and validation of a prediction rule. Diabetologia. 2010;53:254–262. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1585-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Looker HC, Colombo M, Hess S, et al. Biomarkers of rapid chronic kidney disease progression in type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;88:888–896. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichimura T, Bonventre JV, Bailly V, et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), a putative epithelial cell adhesion molecule containing a novel immunoglobulin domain, is up-regulated in renal cells after injury. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4135–4142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra J, Ma Q, Prada A, et al. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a novel early urinary biomarker for ischemic renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2534–2543. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000088027.54400.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavkov ME, Weil EJ, Fufaa GD, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 and 2 are associated with early glomerular lesions in type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2016;89:226–234. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien J, et al. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:507–515. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, et al. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict stage 3 CKD in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:516–524. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavkov ME, Nelson RG, Knowler WC, Cheng Y, Krolewski AS, Niewczas MA. Elevation of circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 increases the risk of end-stage renal disease in American Indians with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;87:812–819. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamanouchi M, Skupien J, Niewczas MA, et al. Improved clinical trial enrollment criterion to identify patients with diabetes at risk of end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2017;92:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes-Virella MF, Baker NL, Hunt KJ, Cleary PA, Klein R, Virella G. Baseline markers of inflammation are associated with progression to macroalbuminuria in type 1 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2317–2323. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antonellis PJ, Kharitonenkov A, Adams AC. Physiology and Endocrinology Symposium: FGF21: insights into mechanism of action from preclinical studies. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:407–413. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein S, Bachmann A, Lossner U, et al. Serum levels of the adipokine FGF21 depend on renal function. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:126–128. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han SH, Choi SH, Cho BJ, et al. Serum fibroblast growth factor-21 concentration is associated with residual renal function and insulin resistance in end-stage renal disease patients receiving long-term peritoneal dialysis. Metabolism. 2010;59:1656–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jian W-X, Peng W-H, Jin J, et al. Association between serum fibroblast growth factor 21 and diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 2012;61:853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Ding X, et al. Research resource: comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:2050–2064. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HW, Lee JE, Cha JJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 improves insulin resistance and ameliorates renal injury in db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3366–3376. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Har RLH, Reich HN, Scholey JW, et al. The urinary cytokine/chemokine signature of renal hyperfiltration in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cherney DZI, Scholey JW, Daneman D, et al. Urinary markers of renal inflammation in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and normoalbuminuria. Diabet Med. 2012;29:1297–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hui E, Yeung C-Y, Lee PCH, et al. Elevated circulating pigment epithelium-derived factor predicts the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E2169–E2177. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bidadkosh A, Lambooy SPH, Heerspink HJ, et al. Predictive properties of biomarkers GDF-15, NTproBNP, and hs-TnT for morbidity and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes with nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:784–792. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velho G, El Boustany R, Lefèvre G, et al. Plasma copeptin, kidney outcomes, ischemic heart disease, and all-cause mortality in people with long-standing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:2288–2295. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Velho G, Bouby N, Hadjadj S, et al. Plasma copeptin and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3639–3645. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boertien WE, Riphagen IJ, Drion I, et al. Copeptin, a surrogate marker for arginine vasopressin, is associated with declining glomerular filtration in patients with diabetes mellitus (ZODIAC-33) Diabetologia. 2013;56:1680–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2922-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pikkemaat M, Melander O, Bengtsson Boström K. Association between copeptin and declining glomerular filtration rate in people with newly diagnosed diabetes. The Skaraborg Diabetes Register. J Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29:1062–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nielsen SE, Reinhard H, Zdunek D, et al. Tubular markers are associated with decline in kidney function in proteinuric type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu W-J, Li B-L, Wang S-B, et al. Changes of the tubular markers in type 2 diabetes mellitus with glomerular hyperfiltration. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;95:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garg V, Kumar M, Mahapatra HS, Chitkara A, Gadpayle AK, Sekhar V. Novel urinary biomarkers in pre-diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:895–900. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamijo-Ikemori A, Sugaya T, Yasuda T, et al. Clinical significance of urinary liver-type fatty acid-binding protein in diabetic nephropathy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:691–696. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viswanathan V, Sivakumar S, Sekar V, Umapathy D, Kumpatla S. Clinical significance of urinary liver-type fatty acid binding protein at various stages of nephropathy. Indian J Nephrol. 2015;25:269–273. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.145097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Araki S, Haneda M, Koya D, et al. Predictive effects of urinary liver-type fatty acid-binding protein for deteriorating renal function and incidence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetic patients without advanced nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1248–1253. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin C, Wang N. Kidney injury molecule-1 in kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2016;38:1567–1573. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1193816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao X, Zhang Y, Li L, et al. Glomerular expression of kidney injury molecule-1 and podocytopenia in diabetic glomerulopathy. Am J Nephrol. 2011;34:268–280. doi: 10.1159/000330187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alter ML, Kretschmer A, Von Websky K, et al. Early urinary and plasma biomarkers for experimental diabetic nephropathy. Clin Lab. 2012;58:659–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waikar SS, Sabbisetti V, Arnlov J, et al. Relationship of proximal tubular injury to chronic kidney disease as assessed by urinary kidney injury molecule-1 in five cohort studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:1460–1470. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabbisetti VS, Waikar SS, Antoine DJ, et al. Blood kidney injury molecule-1 is a biomarker of acute and chronic kidney injury and predicts progression to ESRD in type I diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2177–2186. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nielsen SE, Andersen S, Zdunek D, Hess G, Parving H-H, Rossing P. Tubular markers do not predict the decline in glomerular filtration rate in type 1 diabetic patients with overt nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1113–1118. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conway BR, Manoharan D, Manoharan D, et al. Measuring urinary tubular biomarkers in type 2 diabetes does not add prognostic value beyond established risk factors. Kidney Int. 2012;82:812–818. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vaidya VS, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, et al. Regression of microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes is associated with lower levels of urinary tubular injury biomarkers, kidney injury molecule-1, and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase. Kidney Int. 2011;79:464–470. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Panduru NM, Sandholm N, Forsblom C, et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 and the loss of kidney function in diabetic nephropathy: a likely causal link in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1130–1137. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heinzel A, Muhlberger I, Fechete R, Mayer B, Perco P. Functional molecular units for guiding biomarker panel design. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1159:109–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0709-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pena MJ, Heinzel A, Heinze G, et al. A panel of novel biomarkers representing different disease pathways improves prediction of renal function decline in type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heinzel A, Mühlberger I, Stelzer G, et al. Molecular disease presentation in diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(Suppl 4):iv17–iv25. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mayer G, Heerspink HJL, Aschauer C, et al. Systems biology-derived biomarkers to predict progression of renal function decline in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:391–397. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Agarwal R, Duffin KL, Laska DA, Voelker JR, Breyer MD, Mitchell PG. A prospective study of multiple protein biomarkers to predict progression in diabetic chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:2293–2302. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verhave JC, Bouchard J, Goupil R, et al. Clinical value of inflammatory urinary biomarkers in overt diabetic nephropathy: a prospective study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;101:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bjornstad P, Pyle L, Cherney DZI et al (2017) Plasma biomarkers improve prediction of diabetic kidney disease in adults with type 1 diabetes over a 12-year follow-up: CACTI study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 10.1093/ndt/gfx255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Peters KE, Davis WA, Ito J, et al. Identification of novel circulating biomarkers predicting rapid decline in renal function in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1548–1555. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pena MJ, Mischak H, Heerspink HJL. Proteomics for prediction of disease progression and response to therapy in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia. 2016;59:1819–1831. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gold L, Ayers D, Bertino J, et al. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carlsson AC, Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, et al. Use of proteomics to investigate kidney function decline over 5 years. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:1226–1235. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08780816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Argiles A, Siwy J, Duranton F, et al. CKD273, a new proteomics classifier assessing CKD and its prognosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Siwy J, Schanstra JP, Argiles A, et al. Multicentre prospective validation of a urinary peptidome-based classifier for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:1563–1570. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zürbig P, Jerums G, Hovind P, et al. Urinary proteomics for early diagnosis in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2012;61:3304–3313. doi: 10.2337/db12-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pontillo C, Jacobs L, Staessen JA, et al. A urinary proteome-based classifier for the early detection of decline in glomerular filtration. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:1510–1516. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roscioni SS, de Zeeuw D, Hellemons ME, et al. A urinary peptide biomarker set predicts worsening of albuminuria in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2013;56:259–267. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lindhardt M, Persson F, Zürbig P, et al. Urinary proteomics predict onset of microalbuminuria in normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients, a sub-study of the DIRECT-Protect 2 study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:1866–1873. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lindhardt M, Persson F, Oxlund C et al (2018) Predicting albuminuria response to spironolactone treatment with urinary proteomics in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 33:296–303 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Lindhardt M, Persson F, Currie G, et al. Proteomic prediction and renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibition prevention of early diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetic patients with normoalbuminuria (PRIORITY): essential study design and rationale of a randomised clinical multicentre trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010310. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Merchant ML, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, et al. Plasma kininogen and kininogen fragments are biomarkers of progressive renal decline in type 1 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2013;83:1177–1184. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schlatzer D, Maahs DM, Chance MR, et al. Novel urinary protein biomarkers predicting the development of microalbuminuria and renal function decline in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:549–555. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bhensdadia NM, Hunt KJ, Lopes-Virella MF, et al. Urine haptoglobin levels predict early renal functional decline in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2013;83:1136–1143. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wang G. Metabolomic biomarkers in diabetic kidney diseases—a systematic review. J Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29:1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ahlqvist E, van Zuydam NR, Groop LC, McCarthy MI. The genetics of diabetic complications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:277–287. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sandholm N, Salem RM, McKnight AJ, et al. New susceptibility loci associated with kidney disease in type 1 diabetes. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Teumer A, Tin A, Sorice R, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify genetic loci associated with albuminuria in diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65:803–817. doi: 10.2337/db15-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Simpson K, Wonnacott A, Fraser DJ, Bowen T. MicroRNAs in diabetic nephropathy: from biomarkers to therapy. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:35. doi: 10.1007/s11892-016-0724-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Argyropoulos C, Wang K, Bernardo J, et al. Urinary MicroRNA profiling predicts the development of microalbuminuria in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Med. 2015;4:1498–1517. doi: 10.3390/jcm4071498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Argyropoulos C, Wang K, McClarty S, et al. Urinary microRNA profiling in the nephropathy of type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pezzolesi MG, Satake E, McDonnell KP, Major M, Smiles AM, Krolewski AS. Circulating TGF-β1-regulated miRNAs and the risk of rapid progression to ESRD in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64:3285–3293. doi: 10.2337/db15-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Peng H, Zhong M, Zhao W, et al. Urinary miR-29 correlates with albuminuria and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou J, Peng R, Li T, et al. A potentially functional polymorphism in the regulatory region of let-7a-2 is associated with an increased risk for diabetic nephropathy. Gene. 2013;527:456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Delic D, Eisele C, Schmid R, et al. Urinary exosomal miRNA signature in type II diabetic nephropathy patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eissa S, Matboli M, Aboushahba R, Bekhet MM, Soliman Y. Urinary exosomal microRNA panel unravels novel biomarkers for diagnosis of type 2 diabetic kidney disease. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016;30:1585–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barutta F, Bruno G, Matullo G, et al. MicroRNA-126 and micro-/macrovascular complications of type 1 diabetes in the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00592-016-0915-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Effects of dapagliflozin treatment on urinary proteomic patterns in patients with type 2 diabetes (DapKid). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02914691. Accessed 17 Oct 2017

- 99.Renoprotective effects of dapagliflozin in type 2 diabetes (RED) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02682563. Accessed 17 Oct 2017

- 100.Ivabradine to treat microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease (BENCH) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03105219. Accessed 17 Oct 2017

- 101.Pena MJ, de Zeeuw D, Andress D, et al. The effects of atrasentan on urinary metabolites in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:749–753. doi: 10.1111/dom.12864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Burns KD, Lytvyn Y, Mahmud FH, et al. The relationship between urinary renin-angiotensin system markers, renal function, and blood pressure in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;312:F335–F342. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00438.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carlsson AC, Östgren CJ, Länne T, Larsson A, Nystrom FH, Ärnlöv J. The association between endostatin and kidney disease and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2016;42:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dieter BP, McPherson SM, Afkarian M, et al. Serum amyloid a and risk of death and end-stage renal disease in diabetic kidney disease. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016;30:1467–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang Y, Li Y-M, Zhang S, Zhao J-Y, Liu C-Y. Adipokine zinc-alpha-2-glycoprotein as a novel urinary biomarker presents earlier than microalbuminuria in diabetic nephropathy. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:278–286. doi: 10.1177/0300060515601699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fufaa GD, Weil EJ, Nelson RG, et al. Association of urinary KIM-1, L-FABP, NAG and NGAL with incident end-stage renal disease and mortality in American Indians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2015;58:188–198. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3389-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bouvet BR, Paparella CV, Arriaga SMM, Monje AL, Amarilla AM, Almará AM. Evaluation of urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase as a marker of early renal damage in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;58:798–801. doi: 10.1590/0004-2730000003010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Petrica L, Vlad A, Gluhovschi G, et al. Proximal tubule dysfunction is associated with podocyte damage biomarkers nephrin and vascular endothelial growth factor in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu C, Wang Q, Lv C, et al. The changes of serum sKlotho and NGAL levels and their correlation in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with different stages of urinary albumin. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.do Nascimento JF, Canani LH, Gerchman F, et al. Messenger RNA levels of podocyte-associated proteins in subjects with different degrees of glucose tolerance with or without nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Panduru NM, Forsblom C, Saraheimo M, et al. Urinary liver-type fatty acid-binding protein and progression of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2077–2083. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee JE, Gohda T, Walker WH, et al. Risk of ESRD and all cause mortality in type 2 diabetes according to circulating levels of FGF-23 and TNFR1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jim B, Ghanta M, Qipo A, et al. Dysregulated nephrin in diabetic nephropathy of type 2 diabetes: a cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Coca SG, Nadkarni GN, Huang Y, et al. Plasma biomarkers and kidney function decline in early and established diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2786–2793. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016101101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Saulnier P-J, Gand E, Velho G, et al. Association of circulating biomarkers (adrenomedullin, TNFR1, and NT-proBNP) with renal function decline in patients with type 2 diabetes: a French prospective cohort. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:367–374. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]