Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV), including homicides is a widespread and significant public health problem, disproportionately affecting immigrant, refugee and indigenous women in the United States (US). This paper describes the protocol of a randomized control trial testing the utility of administering culturally tailored versions of the danger assessment (DA, measure to assess risk of homicide, near lethality and potentially lethal injury by an intimate partner) along with culturally adapted versions of the safety planning (myPlan) intervention: a) weWomen (designed for immigrant and refugee women) and b) ourCircle (designed for indigenous women). Safety planning is tailored to women’s priorities, culture and levels of danger. Many abused women from immigrant, refugee and indigenous groups never access services because of factors such as stigma, and lack of knowledge of resources. Research is, therefore, needed to support interventions that are most effective and suited to the needs of abused women from these populations in the US. In this two-arm trial, 1250 women are being recruited and randomized to either the web-based weWomen or ourCircle intervention or a usual safety planning control website. Data on outcomes (i.e., safety, mental health and empowerment) are collected at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months post- baseline. It is anticipated that the findings will result in an evidence-based culturally tailored intervention for use by healthcare and domestic violence providers serving immigrant, refugee and indigenous survivors of IPV. The intervention may not only reduce risk for violence victimization, but also empower abused women and improve their mental health outcomes.

Keywords: Intervention, intimate partner violence, Immigrant, Indigenous

Introduction

Immigrant, refugee (IMR) and indigenous women are at high risk for victimization by intimate partner violence (IPV), severe IPV, and intimate partner homicide (IPH) [1–6]. Nearly half of indigenous women experience IPV in their lifetime[7]. Lifetime prevalence rates of IPV found in community based studies of IMR women range from 24 to 60% [6, 8, 9]. Factors unique to IMR– e.g., lack of familiarity with laws and rights in new country– were found to elevate this populations’ vulnerability to IPV [10–15]. IMR women perceive more risks and barriers to leaving an abusive relationship (e.g., fear of deportation) than non-IMR women [16]. Indigenous women are at elevated risk of IPV due to a complex interplay of factors arising out of the colonization experience. Racism and other stressors – particularly trauma from enforced migration and/or boarding school experiences – further contribute to increases in family abuse and post-traumatic responses (e.g., PTSD) [17]. Other factors associated with IPV among Native American women include low socio-economic status, rurality, and lack of health and public safety infrastructure to address IPV [3]. Many of these elevated risks for IPV may be linked to their experiences of colonization [18]. IPV is a serious risk factor for murder/attempted murder of a woman by her intimate partner, and is associated with disempowerment of women, negative physical health [19–21] and mental health outcomes (e.g., depression, PTSD) [22–30].

In an analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data (2003–2013) from 19 US states, 77.4% of women were killed by an intimate partner [31]. Further, foreign born status has been found to be the strongest risk factor for IPH [2]. Foreign-born women victims are more likely than US born women victims to be associated with IPV-related deaths[31]. This includes foreign-born immigrant (those who came to settle in the US) and refugee women (those who were forced to leave their countries to escape war, persecution or natural disaster). Evidence also shows higher rates of IPH among indigenous women(1.46 per 100,000) when compared to white women (0.96 per 100,000)[1]. In a CDC study, indigenous women experienced higher rates of homicide (4.3 per 100,000) than women from other racial/ethnic groups (Whites, Hispanics and Asians) [4]. Efforts to assist survivors of IPV imply a calculation of risk[32, 33] and survivors of IPV should be educated about their individual risk and potential risk factors [34]. A safety planning intervention tailored to women’s level of risk, culture and priorities can empower women via education about risk and access to resources.

This paper describes a study protocol for evaluating a culturally adapted web-based safety decision aid/safety planning (myPlan) intervention, entitled weWomen and ourCircle myPlan for IMR and indigenous women. The aim is to test the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing abused women’s risk for future IPV/IPH, and poor mental health and increasing empowerment. The study has two phases: 1) formative research to culturally adapt the original myPlan intervention[35] for IMR and indigenous women; and 2) randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of the culturally-adapted intervention. To date, no studies in the US have examined the effectiveness of a web-based safety planning intervention for IMR and indigenous women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background of the original intervention

The Danger Assessment [28, 36] (DA) instrument was developed to assist abused women in assessing their level of danger in the abusive relationship. The DA can be self-administered or used with an advocate or practitioner to support women in identifying incidents of past abuse using codes on a 12-month calendar and completing 20 yes/no questions about risk factors (e.g., increase in frequency and severity of IPV, partner use of weapon, partner threats to kill). A weighted scoring system identifies women at the following levels of danger: variable (<8), increased (8–13), severe (14–17) and extreme (>18) danger. The DA-informed safety decision aid (myPlan), a web-based application (app) was designed as an interactive and tailored safety decision aid to reduce abused women’s decisional conflict and increase safety-seeking behaviors, thus preventing exposure to repeat violence and improving mental health over time. The intervention provides education about healthy relationships, red flags for unsafe and abusive intimate relationships, allows the user to answer DA questions and provides immediate graphic feedback on the DA score with level of danger and evidence-based messages to inform interpretation of the danger level, and takes the user through a priority-setting activity where she can consider her values (e.g. privacy, feelings for partner, having resources, safety and well-being of children) with regard to her relationship. Information provided by the user, such as relationship status, children in the home, employment status) and the DA score are combined with the safety priorities of the user to develop a tailored safety action plan with links to resources and services. In a multistate, community-based longitudinal randomized controlled trial, the internet-based version of the myPlan intervention (i.e. developed and tested prior to introduction of web-based apps) reduced women’s decisional conflict and increased the number of helpful safety behaviors tried compared to women in the control group (e.g. usual safety planning). Findings also suggested that safety decision aid delivered via secure website can help abused women with the highest level of danger in their relationships safely navigate ending their abusive relationships and reduce future sexual violence and psychological abuse[37]. Please see published original myPlan safety decision aid protocol for details [35]. Web-based or online interventions offer numerous benefits and have demonstrated efficacy among survivors of IPV in the United States (US), Canada, Australia, and New Zealand[37–40]. The efficacy of a web-based safety decision aid (isafe) was evaluated via a randomized controlled trial (RCT; n=412) including indigenous (Māori) women in New Zealand. Access to isafe intervention was found to be effective in reducing violence at 6 and 12 months and in reducing depression symptoms at 3 months among indigenous Māori women[41]. Research, however, is still needed to evaluate the effect of web-based safety decision aid on IMR and indigenous women residing in the US.

2.2. Formative phase: Cultural adaptation

The present study extends the previous work on the DA and myPlan app by culturally adapting these for IMR and indigenous women in abusive intimate relationships. For cultural adaptation: a) We conducted focus groups and key informant interviews with practitioners and individual in-depth interviews with survivors of IPV, and b) used the findings from the qualitative data and input from experts to refine and culturally adapt the DA and the myPlan app. The qualitative data was collected using in-depth interviews with 86 IMR survivors from diverse countries (e.g., India, Thailand, Philippines, Laos, Mexico, Somalia, Congo, Rwanda, Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia) in Asia, Africa, Central America and Caribbean regions. Further, 9 focus groups and 8 key informant interviews were conducted with 64 practitioners with extensive experience serving IMR survivors of IPV. Data was also collected from 43 Native American survivors of IPV from multiple tribes. In addition, we conducted 6 focus groups and 7 key informant interviews at different geographic locations with 40 practitioners serving Native American survivors of IPV from various indigenous tribes in the US. The eligibility criteria for survivors included being over 18 years of age, experience of IPV in the past 2 years, and IMR or indigenous background. The eligibility criterion for practitioners was two or more years of experience serving IMR or indigenous survivors or perpetrators of IPV. Culturally specific risk and protective factors of IPV were identified from the qualitative data to tailor the existing DA for IMR and indigenous women.

After qualitative data collection and analysis, the team had a summer research retreat where the study partners and research team members worked together to finalize recruitment materials, culturally adapt the myPlan intervention and make recruitment plans for Phase 2 of the project (randomized controlled trial). Also, feedback was obtained on cultural appropriateness of the existing myPlan intervention from 10 culturally specific experts servicing IMR and indigenous survivors. Indigenous and immigrant collaborators and research team members provided input on cultural appropriateness of overall study measures, culturally specific risk and protective factors for severe and lethal IPV, and the wording and content of the existing myPlan intervention. For instance, we changed the word “abuse/violence” in the original myPlan to “mistreatment” for IMR women. Since many IMR women face in-law abuse, in the red-flag section, we added a question on whether in-laws or partner’s family were mistreating the survivor or contributing to the partner’s mistreatment. For priorities, we added “having community support” as a priority for abused IMR women. In the resource section, we added specific resources for IMR women such as information on immigration-related services. Similarly, for indigenous survivors, we modified the language of the questions and added new questions and resources that would specifically apply to indigenous participants. Two separate web-based applications were created for recruiting IMR and indigenous survivors of IPV. The web-based application for IMR survivors was named “weWomen” and the web-based application for indigenous or Native American survivors was named “ourCircle”.

2.3. Research design

The randomized controlled trial is recruiting and enrolling adult women (18 years and older) who are randomly assigned to either the internet/and or smartphone app accessible culturally tailored myPlan intervention (either weWomen or ourCircle) or the control app (usual safety planning). We hypothesize that at 3, 6 and 12 months post-baseline, the intervention group will have increased safety seeking behaviors, reduced exposure to IPV, improved mental health, and increased empowerment in comparison to the control group. Our first participant was recruited in 2017, and data collection is to be completed by Spring, 2019.

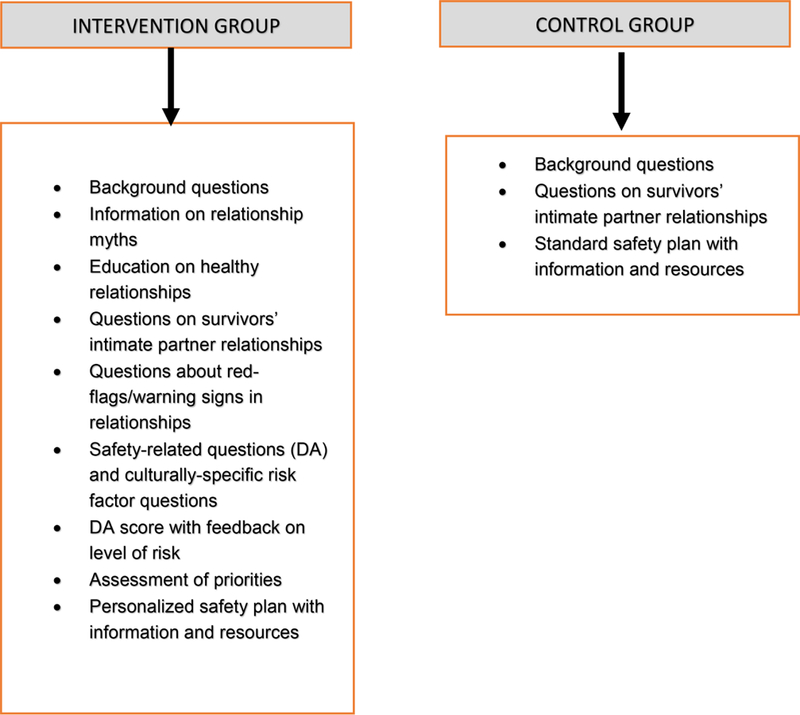

The intervention group receives the weWomen/ourCircle intervention with the appropriate culturally-specific DA integrated. Women receive immediate feedback on dangerousness in their relationships. A component of the intervention is a safety priority setting activity based on a multicriteria decision model [42]. Women use a sliding scale to identify their safety priorities. The examples of priorities that they choose from are: commitment to relationship, having community support, having resources, safety, her health and well-being or her child’s well-being. Intervention group participants are then provided with a safety action plan tailored to the factors in their situation, particularly those associated with lethality (e.g., abuser has a gun), their level of danger, socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. relationship characteristics, living with partner/ separated), social and financial resources; relative importance they place on cultural norms, children, relationship, personal autonomy. Women are able to access the web-based weWomen/ourCircle intervention throughout the 1-year postbaseline follow-up period via the secure password-protected website. The control group receives non-DA informed (i.e., safety planning is not tailored to their level of danger on the DA) usual safety planning resources modeled on national and state domestic violence online resources but are not provided with immediate and visual feedback to their level of danger or a tailored safety planning (See Figure 1 for description of the intervention and control group).

Figure 1:

Content of the Intervention and Control Arms for weWomen and ourCircle Participants

2.4. Study setting

Women are being recruited from diverse regions of the US (e.g., Arizona, Alaska, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Massachusetts, Montana, California, Virginia, and Washington DC). In order to ensure adequate participation, the study is recruiting survivors of IPV from a wide variety of agencies such as healthcare centers, criminal justice programs and shelters that serve IMR and indigenous women.

2.5. Participant recruitment

Survivors are being recruited through verbal or written invitations to participate. In order to reach broadest range of participants, survivors are also being recruited through list serves, emails, and snowball sampling methods. In some sites, our study partners assess eligibility, obtain consent, and refer women to the weWomen or ourCircle study websites, as appropriate to the target groups. If women report not having a computer/smartphone or not feeling safe using their smartphone/computer, the staff at our partner sites brainstorm with women about safe access locations (e.g., local library).

2.6. Inclusion criteria

Eligible women are foreign-born IMR women or belong to any Native American tribe in the US (either urban dwelling or recruited with tribal approvals), are between the ages of 18 and 64 years, have had experienced IPV within the past year, and have access to a safe device (computer or smartphone) with internet access.

2.7. Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for the study are as follows: no experience of IPV within the past year, US-born and not Native American, younger than 18 years of age and older than 64 years and cannot access or use internet.

2.8. Data collection procedures

This study collects data at four time points: Baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Data is being collected through online web-based questionnaires or smart phone application depending on the preference of the participant. The weWomen and ourCircle websites provide information about study-related expectations, incentives, and the eligibility criteria. Interested participants click on a link of the web page to further determine eligibility by responding to screening questions. If they are eligible, participants are asked to provide their contact information including a secure email address to which all study-related information is sent. An electronic message is then generated and sent to the secure email address. The email includes instructions that guide women through the steps on the web-based survey and intervention and to log in using an assigned user name and password. They are also provided with a specific lock PIN to reduce the risk that their abusive partner accesses the information. The women can reset the PIN and password if necessary and are instructed to contact the research team using the email address should they have technical problems accessing the web-based application or if they forget their password or have other study-related concerns or questions.

The study websites include an audio-option in different languages for women with low literacy. For non-English speaking participants, there is an option of using the online survey and intervention available in selected languages most widely used by our potential non-English speaking participants (e.g., Spanish, Arabic, Hmongic, Somali, Kswahili, and French). For some survivors, a bilingual trained partner staff at the agency provides assistance in completing the study sessions (i.e., the baseline survey, intervention website, and follow up periods).

2.9. Retention

Women are encouraged to log in to complete data collection and study-related tasks on the day of enrollment. Women who do not complete within the first three days are sent an automatic reminder email/text (depending on the preference and safety concerns of the women). The online system continues to send reminders to women who have not completed the session using the safe contact information provided until the sessions are completed or the person decides not to continue with the study. A secure study database is used for protecting participant contact information. Both intervention and control groups are contacted by the team at multiple time-points (i.e., baseline, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months post-baseline). Other retention strategies include building rapport with participants, increasing incentives over the 1-year period, and collecting the name and contact information of close trusted contacts that will be around for the duration of the study. Participants are compensated $20 at baseline, $25 at 3 months, $30 at 6 months and $40 at 12 months.

2.10. Outcome measures and variables

2.10.1. Primary outcomes

● Change in severity and/or frequency of physical violence

Severity and frequency of physical violence is measures using the adapted version of the revised Conflict Tactics Scale[43] (CTS-2). The items on the CTS-2 are scored using the severity-times-frequency weighted score.

2.10.2. Secondary outcomes

● Change in depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms are assessed using The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)[44]. It is a 9-item measure to assess depression symptoms based on the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV). Each of the 9 items scores from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).

● Change in symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire[45] (16 items) is used to measure symptoms of PTSD derived from the DSM-IIR/DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. The scale for each question includes four categories of response: “Not at all,” “A little,” “Quite a bit,” “Extremely,” rated 1 to 4, respectively.

● Change in overall empowerment

The Personal Progress Scale-Revised[46] (PPS-R) is used to measure overall empowerment. The PPS-R is a 28 item self-report measure of empowerment designed to assess multiple areas associated with empowerment such as positive self-evaluation, self-esteem, ability to regulate emotional distress, gender-role and cultural identity awareness, self-efficacy, self-care, problem-solving, assertiveness skills, and access to resources. Item responses are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Almost Never) to 7 (Almost Always).

● Change in empowerment related to safety

Empowerment related to safety is measured using the Measure of Victim Empowerment Related to Safety (MOVERS) scale[47]. MOVERS is a 13-item scale that measures empowerment within the domain of safety. Participants respond to each item using a five-point scale from “never true” to “always true.”

2.11. Data analytic plan

Before proceeding to hypothesis testing models, we will examine whether randomized groups differ across demographic characteristics at baseline. Independent group t-tests and chi-squared tests will be used for continuous and categorical variables accordingly. If there are significant differences between groups on any of the demographic variables we will include these variables as covariates in the main analyses.

Intention-to-treat analysis using GEE models will be used so that all available data from all waves will be included to estimate model parameters. We will also examine the effect of intervention dose by conducting a separate set of analyses in the intervention groups to using the number of sessions delivered as a predictor (women are able to log into the intervention any time they like).

GEE models will be used to examine differences in change over time between intervention group participants, who were administered the weWomen/ourCircle myPlan intervention, and controls, who received non-DA informed usual safety planning. The main predictor will be binary with two levels (intervention vs. control) with outcome variables. Ordinary, logistic, Poisson, or negative binomial functions will be applied as appropriate for the distribution of the outcome variable. Covariates for models will include socio-demographic variables found statistically different between groups at baseline and previous protective actions/resource use. We will perform post-hoc exploratory subgroup analysis (e.g., Asian, Latina, African) to explore potential differences in findings across subgroups.

2.12. Power calculation and sample size

Power analyses in G*Power indicate that, with moderate correlation among our predictors, we have 80% power to detect a protective odds ratio of 0.5 and risk odds ratio of 1.9 with a sample size of 200 from each ethnic group-of-interest, with 5 targeted groups. We aim to recruit and retain total of 1250 women in the study, with half in the intervention group and half in the control group for each targeted ethnic group-of-interest. This includes 750 immigrant women, and 500 indigenous women (½ urban-dwelling and ½ on tribal land). Within these groups, we will attempt to obtain both regional and generational heterogeneity via partnerships with community organizations in diverse areas and referrals by previous participants. This strategy will provide us with the ability to examine outcomes separately for diverse groups of IMR women (e.g., Asian, Latina and African), as well as urban and non-urban dwelling indigenous women.

2.13. Protection Against Risk

All participants are provided with information essential for informed consent prior to participation in the study. The women will also be advised on the web-based application about how to password-protect their email accounts and how to clear the history (or cache file) in their browser settings. Women’s confidentiality is considered primary to this study protocol. Implementing important safety procedures for the internet and handling study data serves to protect women from harm. During the study, women may stop at any time. The web-based application accessed by participants includes information on safety resources (i.e., information on multiple community and domestic violence resources). No information is given out to anyone outside the research team about whether a particular woman participates in the study. The study is generally be referred to as dealing with “women’s safety and health.” Trained research staff conduct all aspects of the study.

2.14. Safety procedures for internet use by participants

The web-based weWomen/ourCircle myPlan intervention is protected with a username and password. However, it’s important to know that controlling or abusive partners can and often do spy, harass, and stalk their partners or ex-partners by monitoring their devices directly (looking at them), stealing their passwords, installing spyware programs, etc. If the abuser finds the site in the browser history, he will only see the PIN code screen. So, the web-based application is password protected. If a survivor is forced to open it, and if she enters a code of 0000, it will take her to a non-violence specific, innocuous page. All study communication to the woman will refer to a general women’s health study and not specifically reference violence or abuse.

2.15. Data safety procedures

Only the research team members have access to participants’ data. The team rigorously follow procedures to ensure confidentiality of data. Data is kept on a secured password-protected database and server. Only a single encrypted computer file at the study site contains information linking subject-identifying information (names) with study ID code. All other study materials and files only includes the study ID code. Each participant is given a username and password to access a secure online survey application that allows them to self-report and store their de-identified data. This system uses usernames that do not identify the participant, but simply allow them to have a unique identifier to access the system. On enrolling a study participant, the system generates a unique, non-identifying study ID and password which is used by the participant to access the self-reporting system. At the termination of the study and after analysis has been completed, a copy of the de-identified data set will persist as a file only. The transactional databases used to store personal information and study information will both be deleted. There will be no key to link any of the de-identified records to any identifiable individual.

3. Discussion

With the growing diversity of the US populations, and the risk of IPV/IPH among abused IMR and indigenous women, practitioners in various arenas are becoming more likely to encounter situations that require culturally competent and tailored risk assessments and interventions. Current tools and interventions do not take into account culture, IMR or indigenous status. Cultural factors influence and obstruct accurate assessment of risk and may result in premature assumptions, inaccurate determinations of risk of future IPV/IPH and inability to identify the actual needs of abused women [48]. As interventions that appear to work with one cultural group may not work for other cultural groups, it is imperative that risk assessments and safety planning interventions are developed for specific cultural groups at high risk for homicide. Risk assessments and safety planning interventions that take into account a survivors’ culture is likely to resonate with a survivor in ways that assessments and interventions developed for the majority white culture will not. To our knowledge, this intervention is the first specifically intended to address this need by developing culturally-tailored risk assessment tools and an intervention for abused IMR and indigenous women. Women who do not have home internet access can participate in this intervention research via smartphones. Women can participate in the intervention at any time or place where they have access to a safe computer and internet. Thus, it is a useful approach to reach out to by IMR and indigenous women (rural and urban) who face numerous barriers in accessing formal community resources or participating in intervention research. This will be the first randomized controlled trial to evaluate the utility of a web-based intervention with IMR and indigenous women in abusive relationships. The study plays a critical role in developing an evidence-base for a culturally tailored intervention for underserved and under-researched groups of abused women in the US.

Despite the strengths of this study, there are some limitations and challenges. We are primarily relying on women’s self-reports; while subject to reporting bias, we expect this to be minimal due to the use of web-based format. Because of reliance on technology, technical issues can present barriers. However, our strong technical support within the team and the availability of staff at the university to address any issues have helped overcome these barriers. Based on the skills and previous experiences of the research team, the use of social media sources, and our demonstrated community engagement and collaboration with our partners, we believe that the weWomen/ourCircle intervention has strong potential for dissemination to a wide variety of programs serving IMR and indigenous survivors of IPV.

To conclude, the findings of this study will provide evidence support for a culturally tailored weWomen/ourCircle intervention for IMR and indigenous women in abusive relationships. The trial may also inform future studies on the feasibility of safely conducting research with abused minority women using online recruitment and enrollment strategies and collecting data using an online platform. The intervention can be used within police departments, courts, probations, and social service and physical and mental health settings for predicting repeat and severe violence among vulnerable populations of women. Further, the development and testing of a web-based culturally-tailored weWomen/ourCircle myPlan may assist women who are not seeking services. It is anticipated that this intervention will not only reduce the risk for future violence but also promote women’s empowerment and MH.

Acknowledgement

This was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant number 1R01HD081179–01A1. Dr. Sabri was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development (K99HD082350 and R00HD082350). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration: NCT03265847

References

- 1.Violence Policy Center. When men murder women: An analysis of 2015 homicide data [http://www.vpc.org/studies/wmmw2017.pdf] (accessed August 10, 2018)

- 2.Frye V, Hosein V, Waltermaurer E, Blaney S, & Wilt S Femicide in New York City: 1990 to 1999. Homicide Stud 2005, 9(3) 204–228. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1088767904274226 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oetzel J, & Duran B Intimate partner violence in American Indian and/or Alaskan Native communities: A socioecological framework of determinants and interventions. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res 2004, 11(3):49–68. doi: 10.5820/aian.1103.2004.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrosky E, Blair JM, Betz CJ, Fowler KA, Jack SPD, & Lyons BH Racial and ethnic differences in homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violence-United States, 2003–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017, 66(28):741–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahab S, & Olson L Intimate partner violence and sexual assault in Native American communities. Trauma Violence Abuse 2004, 5(4):353–366. 10.1177/1524838004269489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshioka M, Dang Q, Shewmangal N, Chan C, & Tan CI Asian family violence report: A study of the Cambodian, Chinese, Korean, South Asian, and Vietnamese communities in Massachusetts In Asian Task Force Against Domestic Violence, Inc: Boston, Massachusetts; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, & Stevens MR The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2010 Summary Report In Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y, & Hadeed L Intimate partner violence among Asian immigrant communities: Health/mental health consequences, help-seeking behaviors, and service utilization. Trauma Violence Abuse 2009, 10(2):143–170. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raj A, & Silverman JG Intimate partner violence against South Asian women in Greater Boston. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2002, 57(2):111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer HM, Rodriguez MA, Quiroga SS, & Flores-Ortiz YG Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2000, 11(1):33–44.doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Counts DA, Brown JK, & Campbell JC To have and to hit: Cultural perspectives on wife beating: University of Illinois Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denham AC, Frasier PY, Hooten EG, Belton L, Newton W, Gonzalez P, Begum M, & Campbell MK Intimate partner violence among Latinas in eastern North Carolina. Violence Against Women 2007, 13(2):123–140. 10.1177/1077801206296983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firestone JM, Harris RJ, & Vega WA The impact of gender role ideology, male expectancies, and acculturation on wife abuse. Int J Law Psychiatry 2003, 26(5):549–564. 10.1016/S0160-2527(03)00086-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mindlin J, Orloff LE, Pochiraju S, Baran A, & Echavarria E Dynamics of sexual assault and the implications for immigrant women. In Empowering Survivors: The Legal Rights of Immigrant Victims of Sexual Assault Washington DC: National Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project: American University, Washington College of Law; 2011: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabri B, Nnawulezi N, Njie-Carr V, Messing J, Ward-Lasher A, Alvarez C, & Campbell JC Multilevel risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence among African, Asian and Latina immigrant and refugee women: Perceived needs for safety planning interventions. Race Soc Probl 2018. 10.1007/s12552-018-9247-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Amanor-Boadu Y, Messing JT, Stith SM, Anderson JR, O’Sullivan CS, & Campbell JC Immigrant and nonimmigrant women factors that predict leaving an abusive relationship. Violence Against Women 2012, 18(5):611–633. doi: 10.1177/1077801212453139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sotero MA A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. J Health Dispar Res Pract 2006, 1(1):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brownridge DA Violence against aboriginal women: The role of colonization. In Violence against women: Vulnerable populations New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2009:pp. 164–200. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, Block CR, Campbell D, Curry MA, Gary F, Glass N, McFarlane J, Sachs C Sharps P, Ulrich Y, Wilt S, Manganello J, Xu X, Schollenberger J, Frye V, & Laughon K Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multi-site case control study. Am J Public Health 2003, 93:1089–1097. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyriacou DN, Anglin D, Taliaferro E, Stone S, Tubb T, Linden JA, Muelleman R, Barton E, Kraus JF : Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. N Engl J Med 1999. 341(25):1892–1898. 10.1056/NEJM199912163412505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Understanding intimate partner violence: Factsheet 2012. [http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv_factsheet2012-a.pdf]

- 22.Briere J, & Jordan CE Violence against women: Outcome complexity and implications for assessment and treatment. J Interpers Violence 2004, 19(11):1252–1276. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0886260504269682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin SL, Beaumont JL, & Kupper LL Substance use before and during pregnancy: Links to intimate partner violence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2003, 29(3):599–617. 10.1081/ADA-120023461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, Watson K, Batten E, Hall I, & Smith S Intimate partner sexual assault against women and associated victim substance use, suicidality, and risk factors for femicide. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2005, 26:953–967. 10.1080/01612840500248262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mechanic MB Beyond PTSD: Mental health consequences of violence against women. J Interpers Violence 2004, 19(11):1283–1289. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0886260504270690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez S, & Johnson DM PTSD compromised battered women’s safety. J Interpers Violence 2008, 23(5):635–651. 10.1177/0886260507313528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabri B, Bolyard R, McFadgion A, Stockman J, Lucea M, Callwood GB, Coverston CR, & Campbell JC Intimate partner violence, depression, PTSD and use of mental health resources among ethnically diverse black women. Soc Work Health Care 2013, 52(4):351–369. 10.1080/00981389.2012.745461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabri B, Stockman J, Bertrand D, Campbell D, Callwood G, Campbell JC Victimization experiences, substance misuse and mental health problems in relation to risk for lethality among African American and African Caribbean women. J Interpers Violence 2013. doi: 10.1177/0886260513496902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Woods SJ Intimate partner violence and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in women. J Interpers Violence 2005, 20(4):394–402. 10.1177/0886260504267882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshihama M, & Horrocks J The relationship between intimate partner violence and PTSD: an application of Cox regression with time-varying covariates. J. Trauma Stress 2003, 16(4):371–380. 10.1023/A:1024418119254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabri B, Campbell JC, & Messing J Intimate partner homicides in the United States, 2003–2013: A comparison of immigrants and non-immigrants. J Interpers Violence 2018. doi: 10.1177/0886260518792249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Hilton NZ, Harris GT, Popham S, & Lang C Risk assessment among incarcerated male domestic violence offenders. Crim Justice Behav 2010, 37(8):815–832. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0093854810368937 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kropp PR Some questions regarding spousal assault risk assessment. Violence Against Women 2004, 10(6):676–697. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1077801204265019 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell JC Helping women understand their risk in situations of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence 2004, 19(12):1464–1477. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0886260504269698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glass N, Clough A, Case J, Hanson G, Barnes-Hoyt J, Waterbury A, Alhusen J, Ehrensaft M, Grace KT, & Perrin N A safety app to respond to dating violence for college women and their friends: the MyPlan study randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health 2015, 15:871. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2191-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JC Nursing assessment for risk of homicide with battered women. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1986, 8(4):36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glass NE, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Bloom TL, Messing JT, Clough AS, Gielen AC, Case J, & Eden KB The longitudinal impact of an internet safety decision aid for abused women. Am J Prev Med 2017, 52(5):606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Scott-Storey K, Wuest J, Case J, Currie LM, Glass N, Hodgins M, MacMillan H, Perrin N, & Wathen CN A tailored online safety and health intervention for women experiencing intimate partner violence: The iCAN Plan 4 safety randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health 2017, 17(1):273 https://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2Fs12889-017-4143-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koziol-McLain J, Vandal AC, Nada-Raja S, Wilson D, Glass NE, Eden KB, McLean C, Dobbs T, & Case J A web-based intervention for abused women: The New Zealand isafe randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health 2015, 15(1):741–755. 10.1186/s12889-015-1395-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarzia L, Murray E, Humphreys C, Glass N, Taft A, Valpied J, & Hegarty K I-DECIDE: An online intervention drawing on the psychosocial readiness model for women experiencing domestic violence. Women’s Health Issues 2016, 26(2):208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koziol-McLain J, Vandal AC, Wilson D, Nada-Raja S, Dobbs T, McLean C, Sisk R, Eden KB, & Glass NE Efficacy of a web-based safety decision aid for women experiencing intimate partner violence: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2018, 20(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glass N, Eden K, Bloom T, & Perrin N Computerized aid improves safety decision process for survivors of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence 2010, 25(11). doi: 10.1177/0886260509354508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Straus MA, Hamby S, & Warren W: The conflict tactics scales handbook: Revised conflict tactics scale (CTS2) and CTS: Parent-child version (CTSPC) Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001, 16(9):606–613. http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, & Lavelle J The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire. Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992, 180(2):111–116. http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson D, Worell J, & Chandler RK: Assessing psychological health and empowerment in women: The Personal Progress Scale Revised. Women Health 2008, 41(1):109–129. 10.1300/J013v41n01_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodman LA, Cattaneo LB, Thomas K, Woulfe J, Chong SK, & Smyth KF Advancing domestic violence program evaluation: Development and validation of the Measure of Victim Empowerment Related to Safety (MOVERS). Psychol Violence 2014. http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0038318

- 48.Edelson JL, Bible AL, Collaborating for women’s safety, Renzetti CM, Edelson JL and Bergen RL, Editor. 2001, Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks<: /References> [Google Scholar]