Abstract

Data are limited regarding whether the availability of biomarker-directed therapy for lung cancer exacerbates racial and socioeconomic disparities. Patients diagnosed with stage IV lung adenocarcinoma from 2008 to 2013 were identified using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program-Medicare. The primary outcome was a Medicare claim for molecular testing within 60 days of diagnosis, analyzed using multivariable logistic regression; the secondary outcome was overall survival, analyzed using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. All statistical tests were two-sided. Of 5556 patients, 1437 (25.9%) had molecular testing. Testing rates were 14.1% among black, 26.2% among white, and 32.8% among patients of Asian/other descent (adjusted P < .001); 20.6% among patients with Medicaid eligibility vs 28.4% among those without (adjusted P = .01); and 19.9% among patients in the highest census tract-level poverty rate quintile vs 30.7% among patients in the lowest quintile (for all quintiles, adjusted P = .18). Median survival from 60 days was 8.2 months among patients with molecular testing within 60 days of diagnosis and 6.1 months among those without (hazard ratio = 0.92, 95% confidence interval = 0.86 to 0.99; adjusted P = .02). Equitable precision medicine requires concerted implementation efforts.

Precision medicine is central to modern lung cancer treatment. Since 2011, the standard of care for advanced, non-squamous, non-small cell lung cancer has included testing for somatic mutations that prompt treatment with efficacious oral drugs (1). Molecular tumor characteristics now also inform treatment with immunotherapy (2,3).

These innovations may not have been implemented equitably. Historically, disparities in the burden of lung cancer and delivery of guideline-concordant treatment (4) have existed according to race and socioeconomic status. A recent study examined Medicare claims and identified disparities in EGFR and KRAS testing among patients with lung cancer (5). However, claims do not explicitly capture histology or stage, which define criteria for testing (6). Testing disparities among patients known to meet criteria have not been well described.

The objectives of this report were to evaluate disparities according to race and poverty in the initial uptake of molecular testing in stage IV lung adenocarcinoma and to understand their importance by measuring the population-level association between biomarker-directed therapy and overall survival (7).

Patients were identified using a linked cancer registry-claims dataset (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program [SEER]-Medicare) (8). Inclusion criteria included diagnosis from 2008 to 2013 with a first primary stage IV de novo lung adenocarcinoma at age 66–99 years, at least 12 months of continuous fee-for-service Medicare parts A (inpatient) and B (outpatient) coverage before diagnosis, and survival to 60 days after diagnosis with continuous parts A, B, and D (prescription) coverage. Patients were followed for survival through December 31, 2014. The study was submitted to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board and was declared exempt from review.

The primary outcome was the molecular testing rate within 60 days of diagnosis, per Current Procedural Terminology codes in effect during the study period (Supplementary Table 1, available online). The secondary outcome was overall survival, with ascertainment beginning 60 days after diagnosis.

For the molecular testing outcome, primary exposures included race according to SEER (white, black, or Asian/other); and poverty, defined as 1) any patient-level Medicaid dual eligibility per the Medicare state buy-in variable (9) within the year before diagnosis, and 2) the ecological poverty rate among individuals age 65–74 years in each patient’s census tract. Additional exposures included age, sex, year of diagnosis, marital status, Hispanic ethnicity, comorbidity (10), disability status (11,12), any claim from an NCI-designated cancer center, and urban-rural status (13). For survival, the key independent variable was whether patients had claims for genomic testing within 60 days of diagnosis; we additionally modeled the interaction between genomic testing and systemic treatment within 60 days (tyrosine kinase inhibitor corresponding to erlotinib, afatinib, crizotinib, or ceritinib during the study period; other systemic chemotherapy; or no systemic therapy).

The molecular testing outcome was analyzed using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. Overall survival was depicted using the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed using univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. The assumption of proportionality was assessed via graphical inspection of Schoenfeld residuals. Hypothesis tests were performed using the two-sided χ2 test with alpha = 0.05.

Of 5556 patients, 1437 (25.9%) had molecular testing within 60 days of diagnosis. The testing rate was 26.2% among white patients, 14.1% among black patients (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 0.53; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.40 to 0.72 vs white patients), and 32.8% among patients of Asian/other descent (OR = 1.54; 95% CI = 1.23 to 1.93 vs white patients; adjusted P < .001; Table 1).

Table 1.

Associations between patient characteristics and genomic testing rates (N = 5556 patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinoma)

| Patient characteristic | Genomic testing within 60 days of diagnosis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort No. (%) | Tested, % | Unadjusted* |

Adjusted† |

|||

| OR (95% CI)* | P* | OR (95% CI)† | P† | |||

| Total | 5556 (100.0) | 25.9 | — | — | — | — |

| Race‡ | ||||||

| White | 4482 (80.7) | 26.2 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 |

| Black | 467 (8.4) | 14.1 | 0.47 (0.36 to 0.61) | 0.53 (0.40 to 0.72) | ||

| Asian/other | 607 (10.9) | 32.8 | 1.38 (1.15 to 1.65) | 1.54 (1.23 to 1.93) | ||

| Ethnicity‡ | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 5198 (93.6) | 26.1 | 1.00 (Ref) | .15 | 1.00 (Ref) | .52 |

| Hispanic | 358 (6.4) | 22.6 | 0.83 (0.64 to 1.07) | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.22) | ||

| Medicaid dual-eligible§ | ||||||

| No | 3761 (67.7) | 28.4 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | .01 |

| Yes | 1795 (32.3) | 20.6 | 0.66 (0.57 to 0.75) | 0.79 (0.67 to 0.95) | ||

| Census tract-level poverty rate (quintile)‖ | ||||||

| 0% (1) | 1131 (20.4) | 30.7 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | .18 |

| >0% to 4.3% (2) | 1091 (19.6) | 27.3 | 0.85 (0.71 to 1.02) | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.12) | ||

| 4.3% to 8.5% (3) | 1112 (20.0) | 26.4 | 0.81 (0.68 to 0.98) | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.18) | ||

| 8.5% to 15.8% (4) | 1111 (20.0) | 24.9 | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.90) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.16) | ||

| >15.8% (5) | 1111 (20.0) | 19.9 | 0.56 (0.46 to 0.68) | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.96) | ||

| Urban-rural code¶ | ||||||

| Large metro | 3044 (54.8) | 28.2 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 |

| Metro | 1520 (27.4) | 24.5 | 0.83 (0.72 to 0.95) | 0.81 (0.69 to 0.94) | ||

| Urban | 324 (5.8) | 24.1 | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.06) | 0.76 (0.57 to 1.02) | ||

| Less urban | 550 (9.9) | 19.5 | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.77) | 0.59 (0.46 to 0.76) | ||

| Rural | 118 (2.1) | 17.8 | 0.55 (0.34 to 0.89) | 0.59 (0.35 to 0.98) | ||

| Diagnosis year | ||||||

| 2008 | 759 (13.7) | 2.6 | 0.12 (0.08 to 0.20) | <.001 | 0.12 (0.08 to 0.20) | <.001 |

| 2009 | 850 (15.3) | 10.2 | 0.51 (0.38 to 0.68) | 0.49 (0.37 to 0.66) | ||

| 2010 | 824 (14.8) | 18.3 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | ||

| 2011 | 915 (16.5) | 31.3 | 2.03 (1.62 to 2.54) | 2.07 (1.64 to 2.60) | ||

| 2012 | 1038 (18.7) | 39.6 | 2.92 (2.35 to 3.63) | 3.10 (2.48 to 3.87) | ||

| 2013 | 1170 (21.1) | 41.2 | 3.12 (2.53 to 3.86) | 3.28 (2.64 to 4.08) | ||

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||

| 66–70 | 1516 (27.3) | 26.0 | 1.00 (Ref) | .05 | 1.00 (Ref) | .04 |

| 71–75 | 1485 (26.7) | 26.7 | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.17) | ||

| 76–80 | 1187 (21.4) | 24.9 | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.12) | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.10) | ||

| 81–85 | 877 (15.8) | 28.3 | 1.12 (0.93 to 1.35) | 1.15 (0.94 to 1.42) | ||

| 86–99 | 491 (8.8) | 21.2 | 0.77 (0.60 to 0.98) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.99) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2402 (43.2) | 24.1 | 1.00 (Ref) | .008 | 1.00 (Ref) | .002 |

| Female | 3154 (56.8) | 27.2 | 1.18 (1.05 to 1.33) | 1.25 (1.08 to 1.44) | ||

| Comorbidity score# | ||||||

| 0 | 2208 (39.7) | 29.5 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | .003 |

| 1 | 1628 (29.3) | 25.2 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.93) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.98) | ||

| 2+ | 1720 (31.0) | 21.9 | 0.67 (0.58 to 0.78) | 0.76 (0.65 to 0.90) | ||

| Poor disability status** | ||||||

| No | 4876 (87.8) | 27.4 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 |

| Yes | 680 (12.2) | 14.7 | 0.46 (0.37 to 0.57) | 0.61 (0.48 to 0.79) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/partnered | 2587 (46.6) | 28.4 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | .10 |

| Unmarried | 2770 (49.9) | 28.6 | 0.77 (0.68 to 0.87) | 0.85 (0.74 to 0.99) | ||

| Unknown | 199 (3.6) | 23.3 | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.39) | 0.90 (0.64 to 1.28) | ||

| Care at NCI center‡‡ | ||||||

| No | 4912 (88.4) | 23.9 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <.001 |

| Yes | 644 (11.5) | 40.5 | 2.17 (1.83 to 2.57) | 1.96 (1.62 to 2.36) | ||

*Statistics from univariable logistic regression models. P values calculated using the χ2test. CI = confidence interval; NCI = National Cancer Institute; OR = odds ratio; Ref = reference.

†Statistics from a multivariable logistic regression model including all variables listed in table. P values calculated using the χ2test.

‡Race and ethnicity as reported by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

§Medicaid dual eligibility defined using any state buy-in (9) within the 12 months prior to diagnosis according to Medicare enrollment data.

‖Ecological poverty rate among people age 65–74 years in each patient’s census tract of residence.

¶Urban-rural code as defined by the US Department of Agriculture and categorized by the NCI (13).

#Comorbidity score per the NCI modification of the Charlson comorbidity index (10).

‡‡Defined as having facility claim originating at a clinical or comprehensive NCI-designated center from 30 days before diagnosis to 60 days after diagnosis.

The testing rate was 28.4% for Medicaid-ineligible and 20.6% for Medicaid eligible patients (adjusted OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.67 to 0.95 for those with Medicaid eligibility vs those without; adjusted P = .01) (Table 1). The rate was 30.7% among patients in the lowest ecological poverty quintile and 19.9% among patients in the highest quintile (adjusted OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.61 to 0.96 for patients in the highest quintile vs those in the lowest; adjusted P = .18 for the association between poverty rates and testing across all quintiles and adjusted P = .02 for highest vs lowest quintiles).

Testing rates increased over the study period; trends by race and poverty measures are depicted in Supplementary Figure 1 (available online). A sensitivity analysis was performed in which patients with large cell carcinoma or non-small cell lung cancer not otherwise specified were added to the cohort for analysis of molecular testing rates (total N = 7381); results were similar (Supplementary Table 2, available online). Similarly, a sensitivity analysis extending the window for ascertainment of testing from 60 to 90 days after diagnosis yielded similar results (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

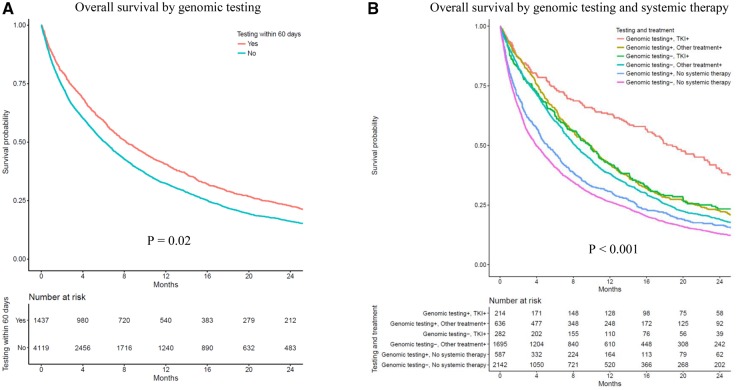

The median follow-up time (beginning 60 days after diagnosis) was 37.1 months. The median survival for patients with early genomic testing was 8.2 months vs 6.1 months for those without (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.86 to 0.99, adjusted P = .02; Figure 1 A; Supplementary Table 3, available online). The association of testing with survival depended on treatment; patients who received both genomic testing and tyrosine kinase inhibitors lived longer (18.8 months) than patients who received genomic testing and chemotherapy (9.8 months) or genomic testing without systemic therapy (5.2 months) (Figure 1B; Supplementary Table 3, available online). The distribution of testing/treatment by race and socioeconomic status is depicted in Supplementary Figure 2 (available online).

Figure 1.

Associations between genomic testing, targeted therapy within 60 days of lung cancer diagnosis, and survival (N = 5556). Overall survival is shown by (A) genomic testing and (B) by genomic testing and treatment. The cohort was restricted to patients who survived at least 60 days after initial diagnosis of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma; exposures were ascertained during the first 60 days after diagnosis, and survival times were assessed beginning at 60 days after diagnosis. Two-sided P values were calculated from multivariable Cox proportional hazards models additionally adjusted for age at diagnosis, race, Hispanic ethnicity, sex, comorbidity (10), disability status (11,12), urban-rural status (13), marital status, Medicaid dual eligibility, area-level poverty rate, and any claim from a National Cancer Institute-designated facility. TKI = tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

This observational study of Medicare enrollees with stage IV lung adenocarcinoma diagnosed from 2008 to 2013 identified racial and socioeconomic disparities in uptake of molecular testing. The findings are consistent with a report that was not specific to histology or stage (5). Although only 20–25% of patients with lung adenocarcinoma have currently targetable driver mutations (14), less than 5% of patients in our study had claims consistent with true targeted therapy—treatment with a targeted agent based on molecular testing. Given the association between targeted therapy and survival in this cohort, this suggests missed opportunities to improve outcomes.

The main limitation of this analysis is the use of billing claims to ascertain molecular testing. Research testing, and testing without billing, would not have been captured. However, it is unlikely these factors systematically bias the findings, because socioeconomically disadvantaged patients are less likely to participate in clinical trials (15) and the incentive to bill for testing in this insured population is substantial. We adjusted for available clinical and sociodemographic factors including comorbidity and functional status, but unmeasured confounding cannot be fully excluded in this observational analysis. Finally, Medicare claims do not reveal molecular testing results or measure availability of tissue for testing.

In conclusion, among Medicare patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, molecular testing was performed less frequently for black patients and those dually covered by Medicaid or residing in poor census tracts. Molecular testing and targeted therapy were associated with improved survival. Concerted efforts are necessary to implement precision medicine equitably.

Funding

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute (NCI)’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC’s) National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement no. U58DP003862–01 awarded to the California Department of Public Health. This work was supported by a K05 grant (K05CA169384; Deborah Schrag) and an R01 grant (R01CA114465; Bruce Johnson) from the NCI.

The National Cancer Institute had no direct role in the design or execution of this study.

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Amy Davidoff for sharing SAS code used to calculate the disability score in this analysis. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s), and endorsement by the State of California Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services, Inc; and the SEER program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Disclosures

Dr Lathan reports holding research funding from CVS Health and serving on advisory boards to Eli Lilly and the Bristol Meyers Squibb Foundation. Dr Schrag reports holding research funding from Pfizer and consulting fees from Proteus, and she has served as a member of the Journal of the American Medical Association editorial board, with compensation. Dr Johnson reports receiving postmarketing royalties for EGFR testing, paid by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and receiving research support from Novartis and Toshiba. Dr Kehl has no disclosures to report.

Notes

Affiliations of authors: Division of Population Sciences (KLK, CSL, DS) and the Thoracic Oncology Program (KLK, CSL, BEJ), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Keedy VL, Temin S, Somerfield MR et al. . American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation testing for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer considering first-line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;2915:2121–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG et al. . Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;37519 doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu T-E, Pluzanski A et al. . Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bach PB, Cramer LD, Warren JL, Begg CB. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;34116:1198–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lynch JA, Berse B, Rabb M et al. . Underutilization and disparities in access to EGFR testing among Medicare patients with lung cancer from 2010–2013. BMC Cancer. 2018;181:306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NCCN. NCCN Guidelines Version 6.2018: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl_blocks.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2018.

- 7. Gutierrez ME, Choi K, Lanman RB et al. . Genomic profiling of advanced non–small cell lung cancer in community settings: gaps and opportunities. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;186:651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(supplement):IV-I3–IV-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koroukian SM, Dahman B, Copeland G, Bradley CJ. The utility of the state buy-in variable in the Medicare denominator file to identify dually eligible Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries: a validation study. Health Serv Res. 2010;451:265–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;5312:1258–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davidoff AJ, Zuckerman IH, Pandya N et al. . A novel approach to improve health status measurement in observational claims-based studies of cancer treatment and outcomes. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;42:157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davidoff AJ, Gardner LD, Zuckerman IH, Hendrick F, Ke X, Edelman MJ. Validation of disability status, a claims-based measure of functional status for cancer treatment and outcomes studies. Med Care. 2014;526:500–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/countyattribs/ruralurban.html. Accessed December 12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson BE. Divide and conquer to treat lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;37519:1892–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;29122:2720–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.