Abstract

This study uses novel approaches to examine genetic and environmental influences shared between childhood behavioral inhibition (BI) and symptoms of preadolescent anxiety disorders. Three hundred and fifty-two twin pairs aged 9–13 and their mothers completed questionnaires about BI and anxiety symptoms. Biometrical twin modeling, including a direction-of-causation design, investigated genetic and environmental risk factors shared between BI and social, generalized, panic and separation anxiety. Social anxiety shared the greatest proportion of genetic (20%) and environmental (16%) variance with BI with tentative evidence for causality. Etiological factors underlying BI explained little of the risk associated with the other anxiety domains. Findings further clarify etiologic pathways between BI and anxiety disorder domains in children.

Keywords: behavioral inhibition, anxiety, twins

First characterized by Kagan and colleagues, childhood behavioral inhibition (BI) is a temperamental trait whereby children express shyness, restraint or other negative effect in response to novel people, objects or environments (Fox et al., 2005; Garcia Coll et al., 1984; Kagan et al., 1988). Roughly 20% of children initially scored as having high BI continue to exhibit elements of inhibition as they age into adolescence (Kagan, 2012), and approximately 40% later develop social anxiety (Clauss et al., 2015; Clauss & Blackford, 2012). While BI is a well-documented risk factor for later social anxiety disorder in adolescents and adults (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Clauss & Blackford, 2012; Essex et al., 2010; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007, 2008; Kagan et al., 1988; Muris et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 1999), it has also been associated with other forms of anxiety-related psychopathology such as specific phobia, panic disorder, separation anxiety, generalized anxiety and avoidant disorder earlier in childhood (Biederman et al., 2001; Dyson et al., 2011; Frenkel et al., 2015; Muris et al., 1999; Paulus et al., 2015). Development is complex, with many possible branching points and outcomes, but a hypothetical example could be that a child with elevated BI presents as more generally anxious during childhood. However, when they get to middle school, a time of increased social pressure, social anxiety symptoms become more prominent, and they are diagnosed with social anxiety disorder as an adolescent. Conversely, it is possible for a child to exhibit elevated BI and continue on a linear progression to develop later social anxiety. However, as they age further, they may learn to hide or better manage many of their symptoms and not meet criteria for a diagnosis. Thus, the overall goal of the present study was to clarify the etiological relationship between childhood BI and preadolescent anxiety domains using novel genetic epidemiological approaches.

BI has been well studied from developmental and clinical perspectives over the past three decades, but genetic epidemiological approaches have been underutilized. Past studies of singletons have examined childhood and/or adolescent and adult ages (i.e., Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Frenkel et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 1999), leaving preadolescence less well understood from a developmental perspective. Prior twin studies have reported moderate heritability through age 2 for BI (42–56%; Emde et al., 1992; Plomin et al., 1993; Robinson et al., 1992) and similar estimates for all childhood anxiety disorders (28–60%; Lahey et al., 2011; Ogliari et al., 2006, 2010; Scaini et al., 2014). However, no twin studies have directly examined the sources of shared genetic and environmental risk factors between BI and anxiety disorders in children. Further, a twin design allows for the examination of possible causal pathways from BI to strongly related anxiety domains even using a cross-sectional design. Pertinently, there is ongoing debate as to whether BI is a distinct construct or simply an earlier version of social anxiety (Clauss & Blackford, 2012).

Preadolescence is a key time to study this shared risk, as symptoms of anxiety disorders are common but largely still at preclinical levels (Rapee et al., 2009; Rapee & Spence, 2004). Understanding this shared risk would complement prior work by further elaborating the etiology of anxiety disorders from a transdiagnostic, genetic perspective (i.e., Kagan et al., 1999; Rapee & Spence, 2004) and possibly inform future prevention/intervention efforts. The current study specifically addresses two key knowledge gaps regarding the shared etiologic pathways between childhood BI and related anxiety domains by dissecting their developmental and phenotypic relationships at the genetic epidemiological level. The first aim of this study was to clarify the exact relationship between BI and key anxiety domains. For example, previously reported associations between BI and generalized anxiety, separation anxiety or panic symptoms (Biederman et al., 2001; Dyson et al., 2011; Frenkel et al., 2015; Muris et al., 1999; Paulus et al., 2015) may be indirect effects of correlations between these symptoms and social anxiety rather than a direct result of shared genetic and environmental effects. The second aim was to disaggregate the overlapping sources of liability between the anxiety domains for which BI shares the most genetic and environmental variance. Specifically, it will be tested whether shared genetic and environmental factors are simply correlational, or if evidence for causal pathways can be identified.

Materials and methods

Participants

Families consisting of at least one parent and two twins between the ages of 9 and 13 were recruited from the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry (Lilley & Silberg, 2013). They were enrolled as part of the Virginia Commonwealth University Juvenile Anxiety Study between January 2013 and March 2016, which met all ethical and Institutional Review Board requirements for conduct and consent (Carney et al., 2016). During an in-person laboratory visit, child participants were administered an array of experimental tasks and survey instruments that probed constructs putatively related to the development of anxiety and other internalizing disorders. Their parents completed survey measures about their children’s and their own behavior, emotions and life experiences. A portion of families were invited back for a second laboratory visit 2–4 weeks later to collect reliability data on all measures. Primary analyses in the current study were restricted to the first of two laboratory visits, with parent measures further restricted to maternal reports (89%). The final analytical sample included 352 families and 704 children (Mage = 11.22; SDage = 1.41; female = 53%; monozygotic [MZ] = 114 pairs; dizygotic [DZ] = 238 pairs; 88% of full sample). This sample did not differ from the full sample on included demographic or clinical variables. To reduce genetic variance for future association studies, the sample recruited only Caucasian participants (see Carney et al., 2016 for a more detailed discussion).

Measures

Two measures were included in the current study: a retrospective version of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ; Bishop et al., 2003) and the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders — Parent and Child Versions (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1997). A series of preliminary analyses confirmed their validity, reliability and appropriate usage in the primary analyses as discussed below.

BIQ

The BIQ is a comprehensive, 30-item questionnaire completed by parents to report on their child’s recent behaviors related to BI. It has previously demonstrated reliability and validity (Bishop et al., 2003; Broeren & Muris, 2010) and adequate correlation with the gold standard behavioral assessment of BI (r = .46 among maternal raters, Bishop et al., 2003; 74% agreement rate, Hudson & Dodd, 2012). The BIQ has been successfully used in multiple studies of inhibition and anxiety in childhood, including assessing their neurophysiological and cognitive underpinnings (Clauss et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2015; Morales et al., 2017; Taber-Thomas et al., 2016), predicting anxiety symptoms (Edwards et al., 2010) and evaluating early interventions (Kennedy et al., 2009).

For the current study, we included a retrospectively worded version of the BIQ in which the parents of preadolescents reported on behaviors related to BI when their child was between the ages of 2 and 6 (i.e., early childhood). We confirmed the reliability, validity and factor structure of this slightly modified version of the instrument in the current sample. Overall fit for the factor structure was comparable to that found in previous examinations of the BIQ (see Supplemental Table S1; Bishop et al., 2003; Broeren & Muris, 2010; Kim et al., 2011; Vreeke et al., 2012); it also demonstrated appropriate reliability in a subset of N = 228 in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = .96; intraclass correlation for test–retest reliability = .87; 95% CI = .84, .89) and convergent and divergent validity. For consistency with other studies using the BIQ (Clauss et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2015), the total sum score was used in all analyses.

SCARED

The SCARED assesses anxiety disorder symptoms in children over the past 3 months via five subscales (social, generalized, separation, panic and school avoidance), where the first four are related to diagnostic syndromes and were used in these analyses. It has shown acceptable internal consistency (α = .90–.94) and test–retest reliability (r = .70–.90) in both prior studies and the current one (Birmaher et al., 1997; Carney et al., 2016). We collected both parent and child responses to the SCARED since both types of report for any form of psychopathology are limited and potentially biased (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). As expected, parent-rated BI more strongly correlated with parent-rated than child-rated recent anxiety (see Supplemental Table S2), yet preadolescent children potentially offered additional insight into their own symptomology. Information was combined across raters by including the average of the parent and child SCARED sum scores for each subscale in the analyses with parent-rated BI (see “Analyses” and “Results” below for analytic rationale).

Analyses

Primary statistical analyses were performed with the R software package (version 1.0.136; R Development Core Team, 2015) and twin analyses in OpenMx (OpenMx Development Team, 2011).

Descriptive statistics

The mean, standard deviation and range were calculated for each phenotype. Pearson correlations estimated the within-individual (i.e., phenotypic) associations between anxiety clusters and BI. MZ and DZ twin correlations were calculated individually for each phenotype as well as the cross-twin, cross-trait correlations between phenotypes. This information roughly predicts how the variance of the measures will decompose at the univariate and multivariate levels (Neale & Cardon, 1992).

Biometrical modeling overview

Biometrical structural equation modeling (SEM; Neale & Cardon, 1992) was performed to fit selected twin models to the phenotypes of BI and each anxiety subscale. In this process, the variance was decomposed into additive genetic (A), shared (familial) environmental (C) and unique environmental (E) factors contributing to the phenotype(s) in each model. The A covariance reflects the additive effect of individual alleles at genetic loci influencing a trait. On average, MZ twins shared 100% of their segregating genes, whereas DZ twins shared 50%, so the A factor contributed twice as much to the MZ twin correlation. The C covariance reflects environmental influences that make family members more alike compared with random pairs of individuals, and contributes equally to the MZ and DZ correlations. The E variances are uncorrelated between twins and reflect the aspects of the environment that are specific to each individual; it also includes measurement error. Beginning with full twin SEM in which all three (ACE) components were included, a series of nested submodels were tested in which paths of interest (A, C or both) were constrained to zero to examine their contributions to the phenotype. Model fit was compared using the likelihood ratio test (Wilks, 1938) and Akaike information criteria statistic (Akaike, 1987). These statistics tested whether there was a significant decrease in model fit after parameters in the full model were constrained to zero, indicative of the importance of the constrained parameter(s).

Due to the fact that both children and parents rated the SCARED but only parents rated the BIQ, a multiple rater model was tested to examine and reduce potential rater bias for the SCARED prior to the primary analyses. Specifically, parent and child SCARED scores were included as indicators for a latent ‘anxiety’ variable in the univariate SEM. This was done for each anxiety symptom cluster (social, generalized, separation and panic), and two models per cluster were tested: one where parent and child scores were allowed to freely load on the latent variable, and another where they were constrained to be equal. The best-fitting model was used in all further analyses to index each anxiety symptom cluster, respectively. Additionally, sex was treated as a covariate in all biometrical models due to its known association with various anxiety domains.

Primary analyses

For the first aim, biometrical SEM was used to fit a multivariate Cholesky decomposition of BI and all anxiety clusters to assess which etiological factors were shared between the phenotypes. The order of the clusters in the model was based on the strength of the phenotypic associations between each cluster and BI. At the multivariate level, each source of variance (A, C and E) was estimated as well as its contributions to the covariance between phenotypes. A series of nested submodels tested whether the shared covariance paths could be eliminated from the model, again comparing likelihood ratio test and Akaike information criteria fit statistics.

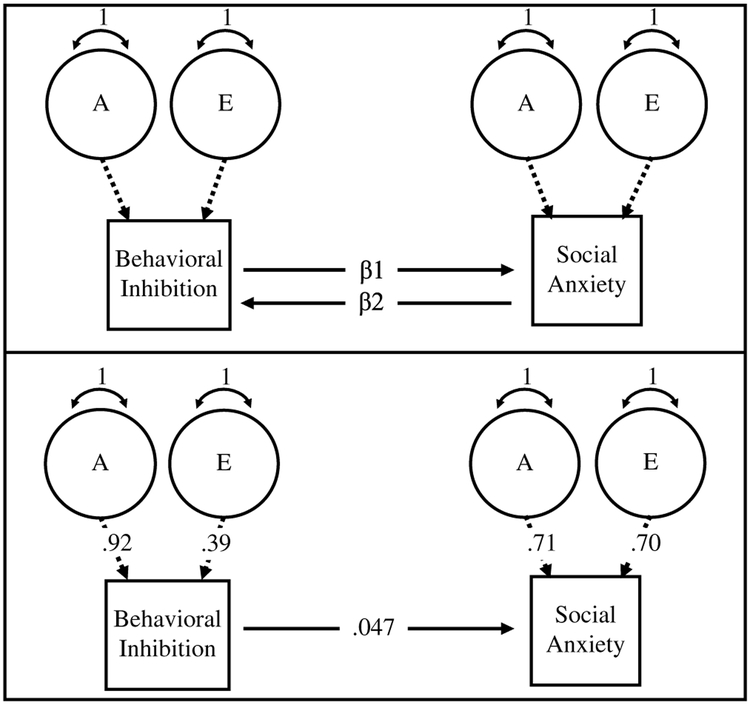

As part of the second aim, a direction-of-causation model was utilized to further explicate the relationship between BI and anxiety constructs with which it shared substantial variance (as revealed from the multivariate biometrical model in the first aim). Traditionally, the direction-of-causation models requires longitudinal or experimental data to show causality. In a cross-sectional, biometrical context, the direction-of-causation models leverage known differences between MZ and DZ twins’ shared genetics and environments. Specifically, these models utilize cross-twin, cross-trait correlations across three unique sources of variance (A, C, E or dominance [D]) (Gillespie & Martin, 2005; Heath et al., 1993; Verhulst & Estabrook, 2012). To the extent that the sources of variance differ across the phenotypes (or that the magnitudes of the same sources of variance differ substantially), inferences can be made about whether a beta regression coefficient (as opposed to a correlation) best explains the relationship between two phenotypes. This was tested via five scenarios that were nested within a full Cholesky decomposition model (see Figure 1; Verhulst & Estabrook, 2012): (a) phenotype 1 causes phenotype 2, (b) phenotype 2 causes phenotype 1, (c) reciprocal causation between phenotypes, (d) an external factor causes both (correlated liabilities), and (e) no association between the two phenotypes. Additionally, the proportion of variance accounted for in the ‘outcome’ phenotype in each direction-of-causation model was estimated and compared with the proportion of variance accounted for by the default correlated liability model (here, the bivariate Cholesky decomposition). The direction-of-causation model was then compared with a correlated liability model (i.e., a bivariate Cholesky decomposition with shared sources of variance) using likelihood ratio test and Akaike information criteria fit statistics.

Fig. 1.

Full direction-of-causation model tested within a nested Cholesky decomposition model (top). Final model found in the present study (bottom).

Results

Correlations and heritability estimates

For all anxiety clusters, parent and child SCARED scores could be constrained to be equal in their multiple indicator models (see Supplemental Table S3). In other words, the average of the parent and child SCARED sum scores provides a reasonable representation of these anxiety domains for analyses with parent-rated BI and were used in all analyses. Within-person correlations among BI and each anxiety domain were consistent with the past findings (see Table 1; Dyson et al., 2011; Muris et al., 1999; Paulus et al., 2015). Consistent with prior reports, childhood BI had the strongest association with preadolescent social anxiety symptoms (r = .57; p<.001) and smaller but significant correlations with generalized anxiety, separation anxiety and panic symptoms(r = .11–.18; p < .05).

Table 1.

Within-person correlations between BI and anxiety symptom clusters

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Behavioral inhibition | — | ||||

| 2. Social anxiety | .57** | — | |||

| 3. Generalized anxiety | .18** | .40** | — | ||

| 4. Separation anxiety | .15* | .36** | .47** | — | |

| 5. Panic | .11* | .35** | .52** | .51** | — |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .001.

All twin correlations for BI and each anxiety domain were significant except for the DZ correlations for BI and social anxiety symptoms (see Table 2 for these data and other descriptive statistics on these measures). For some scales, the DZ correlations were less than half of the MZ correlations, indicating possible influence of non-additive genetic factors such as genetic dominance or epistasis (denoted by D). ADE models that estimate non-additive genetic influences were tested but did not significantly improve model fit over ACE models for any of the phenotypes tested. This was unsurprising, as the power to detect non-additive genetic variance factors has been typically poor in practical twin sample sizes (Martin et al., 1978). The magnitudes of the remaining correlations indicated the possibility of both genetic and common environmental contributions to the variance of each phenotype. The cross-twin, cross-trait genetic correlations followed the same patterns of weaker cross-twin DZ correlations across phenotypes (see Supplemental Table S4).

Table 2.

Descriptive and twin statistics for behavioral inhibition and anxiety symptom clusters

| Measure | Applicable age range | Report | Mean (SD); SE | MZ correlation | DZ correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral inhibition | 2–6 | Parent | 95.24 (35.29); 1.37 | .84** | .05 |

| Social anxiety | 8–13 | Parent | 4.06 (3.59); .14 | .70** | .03 |

| Child | 5.94 (3.91); .15 | .44** | .21* | ||

| Average | 5.00 (2.75); .11 | .64** | −.02 | ||

| Generalized anxiety | 8–13 | Parent | 3.97 (3.74); .14 | .63** | .13* |

| Child | 5.84 (3.63); .14 | .43** | .26** | ||

| Average | 4.91 (2.86); .11 | .56** | .19* | ||

| Separation anxiety | 8–13 | Parent | 2.21 (2.81); .11 | .83** | .36** |

| Child | 5.17 (3.38); .13 | .44** | .38** | ||

| Average | 3.70 (2.46); .09 | .62** | .36** | ||

| Panic | 9–13 | Parent | 1.53 (2.70); .10 | .84** | .56** |

| Child | 5.18 (3.91); .15 | .41** | .25** | ||

| Average | 3.35 (2.48); .10 | .68** | .39** |

Note: Bold type indicates the model used in primary analyses.

p < .05;

p < .001.

Heritability estimates were calculated for each phenotype within the multivariate Cholesky decomposition (see below) to assess consistency with past literature. The estimated heritability of retrospective childhood BI was higher than that of concurrent BI in toddlers (see Table 3; h2 = .76; confidence interval = .65–.84; Emde et al., 1992; Plomin et al., 1993; Robinson et al., 1992). For the anxiety clusters, heritability estimates were slightly different than previously reported (Lahey et al., 2011; Ogliari et al., 2006, 2010; Scaini et al., 2014) except for social anxiety, which was consistent with the past studies (h2 = .52). Specifically, heritability was slightly lower for generalized anxiety (h2 = .49) and slightly higher for both separation anxiety (h2 = .62) and panic (h2 = .68).

Table 3.

Variance and covariance components for the best-fitting multivariate model between BI and anxiety symptom clusters (95% confidence intervals)

| BI (Trait 1) | Social (Trait 2) | Generalized (Trait 3) | Separation (Trait 4) | Panic (Trait 5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive genetic (A) components shared between BI and anxiety symptom clusters | |||||||||

| A11 | A21 | A22 | A31 | A33 | A41 | A44 | A51 | A55 | — |

| .76 (.65, .84) | .20 (.10, .30) | .32 (.22, .41) | — | .43 (.29, .55) | — | .42 (.29, .53) | .01 (.001, .04) | .29 (.18, .40) | — |

| Unique environment (E) components shared between BI and anxiety symptom clusters | |||||||||

| E11 | E21 | E22 | E31 | E33 | E41 | E44 | E51 | E55 | — |

| .24 (.16, .35) | .16 (.07, .28) | .32 (.25, .42) | .07 (.03, .14) | .40 (.29, .52) | .05 (.02, .10) | .29 (.22, .39) | — | .26 (.20, .34) | — |

| Additive genetic (A) components shared between anxiety symptom clusters | |||||||||

| — | — | — | — | A32 | A42 | A43 | A52 | A53 | A54 |

| — | — | — | — | .06 (.01, .16) | .06 (.01, .15) | .14 (.54, .26) | .10 (.03, .20) | .20 (.09, .33) | .08 (.02, .17) |

| Unique environment (E) components shared between anxiety symptom clusters | |||||||||

| — | — | — | — | E32 | E42 | E43 | E52 | E53 | E54 |

| — | — | — | — | .04 (.01, .09) | .03 (.01, .07) | .01 (<.001, .04) | .03 (.01, .07) | .03 (.01, .08) | .004 (<.001, .02) |

Note: Variance components above are equal to the squares of the standardized path estimates seen in Figure 2. Within each phenotype, these should add up to 1.00, but may not due to rounding error.

Note on variance component naming: A11/E11 = behavioral inhibition symptoms; A22/E22 = social anxiety symptoms; A21/E21 = shared between BI and social anxiety symptoms; A33/E33 = generalized anxiety symptoms; A31/E31 = shared between BI and generalized anxiety symptoms; A44/E55 = separation anxiety symptoms; A41/E41 = shared between BI and separation anxiety symptoms; A55/E55 = panic symptoms; A51/E51 = shared between BI and panic symptoms.

All other paths represent shared variance between anxiety symptom clusters.

Relationship between BI and all anxiety clusters

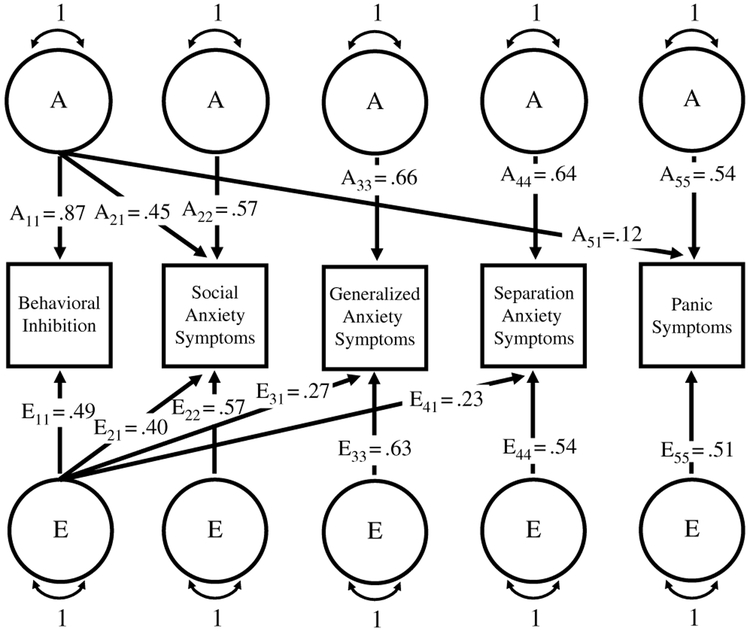

The phenotypic ordering in the multivariate model was based on decreasing magnitude of correlations found between BI and each anxiety domain (Table 1): BI, social anxiety, generalized anxiety, separation anxiety and panic (see Table 3, Figure 2 and Supplemental Table S5).

Fig. 2.

Standardized path estimates from the final multivariate model depicting the shared paths between BI and anxiety symptom clusters and unique paths only (shared inter-anxiety paths not included for simplicity but can be found in the supplementary material).

Consistent with past findings for each individual phenotype, only additive genetic (A) and unique environment (E) significantly contributed to this multivariate relationship (Lahey et al., 2011; Ogliari et al., 2006, 2010; Robinson et al., 1992; Scaini et al., 2014). At least some proportion of the genetic or environmental risk of each anxiety cluster was shared with BI (see Figure 2). Specifically, social anxiety shared the most of its variance with BI (A = .20; E = .16), followed in smaller magnitudes by generalized anxiety (E = .07), separation (E = .05) and panic (E = .01).

There was also significant shared variance between the anxiety clusters (see Table 3), although not as much as previously reported in this age group (Ogliari et al., 2010). Generalized and separation anxiety shared the most genetic variance (A = .14), while social and generalized anxiety shared the most environmental variance (E = .04). A Cholesky decomposition of the anxiety measures alone revealed that, except for social anxiety, these lower between-domain covariance estimates were not due to residual covariance accounted for by including BI in the model (see Supplemental Table S6).

Relationship between BI and social anxiety

Due to the modest but significant amounts of additive genetic and unique environmental variance shared between BI and social anxiety but not with other anxiety clusters, the direction-of-causation model was only tested between these two phenotypes. This model with social anxiety symptoms regressed onto BI fit significantly better than the other direction-of-causation models tested (BI regressed onto social anxiety, joint causation, no association), notably ruling out these other three possibilities as explanations for the relationship between BI and social anxiety. When compared with the correlated liabilities model, which represents an external unmeasured factor causing both phenotypes, the model with BI causing social anxiety was not significantly worse; it estimated a small but notable regression coefficient (β = .047; see Table 4, Figure 1 and Supplemental Table S7). Both models had comparable parameter estimates and fit indices, making it important to assess the amount of social anxiety’s variance accounted for by BI in each model to further explain their relationship from a genetically informed perspective.

Table 4.

Variance components and proportion of social anxiety’s variance accounted for by BI in the best-fitting correlated liabilities and direction-of-causation models

| Correlated liabilities model with cross-paths between phenotypes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique A | Unique E | R2 for A (A21) | R2 for E (E21) | Total R2 | ||

| Behavioral inhibition | .79 | .21 | — | — | — | |

| Social anxiety | .32 | .31 | .24 | .13 | .37 | |

| Direction-of-causation model with causal beta paths between phenotypes | ||||||

| Unique A | Unique E | β1 causal path | R2 for A | R2 for E | Total R2 | |

| Behavioral inhibition | .85 | .15 | .047 | — | — | — |

| Social anxiety | .51 | .49 | .30 | .08 | .38 | |

Note: Variance components above are equal to the squares of the standardized path estimates. Within each phenotype, these should add up to 1.00, but may not due to rounding error. Note on path naming: A21/E21 = shared between BI and social anxiety symptoms; β1 = causal path from BI to social anxiety symptoms; R2 = amount of social anxiety’s variance that is accounted for by BI.

BI in both models accounted for a similar proportion of social anxiety’s variance. Specifically, 37% of social anxiety’s variance (24% of the A and 13% of the E variance) was accounted for by BI in the correlated liabilities model compared with 38% (30% of the A and 8% of the E variance) in the direction-of-causation model. Taken together with their comparable fit to these data, this implies that a direction-of-causation model with a single beta coefficient from BI to social anxiety symptoms modestly informs their relationship beyond the correlated risk structure.

Discussion

Using novel approaches that complement existing developmental research, the current study examined the shared genetic and environmental influences between BI and anxiety symptomology. The first aim of the study sought to clarify the etiology between BI and related anxiety domains, and the second examined the potential causality between BI and the anxiety domain(s) with most substantial genetic and environmental overlap with BI from the first aim. Findings explicate prior reported phenotypic associations of BI with various anxiety symptoms in childhood and its role as a particular risk factor for later social anxiety. It was found that retrospectively reported childhood BI shared both genetic and environmental variance with preadolescent social anxiety symptoms, but there was little to no genetic overlap between BI and other domains of anxiety symptomatology. Tentative evidence was also found for causality between BI and social anxiety.

These findings clarify that associations between childhood BI and preadolescent anxiety symptoms other than social anxiety are primarily a function of shared environmental influences and not simply indirect effects from the correlations between social anxiety and other anxiety clusters. The residual variance of social anxiety increased when BI was taken out of the model, but the genetic and environmental components for the rest of the anxiety clusters and their interrelationships remained unchanged. This implies that associations found in the model that included BI are fairly robust. If the relationship between BI and the other clusters was due to correlations with social anxiety, then their variance components should have differed in the model without BI. Given the generally more stable effects of genetic-versus-environmental influences across development, this finding helps clarify the more robust, longitudinal relationship seen between early BI and later social anxiety disorder compared with other anxiety disorders.

Further, there is tentative evidence that the relationship between BI and social anxiety is causal. A significant proportion of the variance of preadolescent social anxiety symptoms was explained by childhood BI, specifically about a quarter of the additive genetic variance and a tenth of the unique environmental variance. While it had been previously shown that about 40% of children with BI later develop social anxiety (Clauss et al., 2015; Clauss & Blackford, 2012), the current findings suggest a particularly strong, etiologically relevant link. Our twin direction-of-causation model provided a potential approach for distinguishing correlation and direct causation between etiological sources of covariance between BI and social anxiety. The model fits were not significantly worse, and variance estimates were on par with those of the correlated model, implying that either is an appropriate way to represent the relationship between BI and social anxiety disorder. The direction-of-causation model provides an etiologically informed twin version of a linear regression, bridging the gap between genetically informed and behavioral-based studies.

These findings contribute to two key threads in the BI and social anxiety literature. There has been a long-standing debate regarding the developmental distinction between BI and social anxiety disorder (Clauss & Blackford, 2012). The current study adds a genetically informed perspective to this discussion by demonstrating that both shared genetic and environmental factors partially, yet substantially, underpin the relationship between BI and social anxiety. This expands upon past longitudinal studies and expert reviews (Fox et al., 2005; Kagan et al., 1999; Rapee & Spence, 2004). Importantly, these findings also suggest that there are etiologic distinctions, supporting the hypothesis that these phenotypes are not two measures of the same underlying construct.

In addition, these results add to the growing evidence that childhood BI is a putative endophenotype for later social anxiety. Endophenotypes are ‘intermediate’ phenotypes that lie in the etiological pathway between genetic variation and a disorder (Cannon & Keller, 2006; Gottesman & Gould, 2003). BI has previously been shown to meet a subset of the basic requirements as an endophenotype for social anxiety, including association with the disorder and being itself heritable. The present study adds further support to these two criteria and provides the first firm evidence for a third requisite criterion: co-segregation of the two phenotypes within families (instantiated here as cross-phenotype correlations within twin pairs). Furthermore, these results suggest that this familial coaggregation is primarily due to additive genetic factors. This is the first study conducted on a substantially sized, genetically informative sample that includes measures of both phenotypes since Kagan’s longitudinal studies of BI (Kagan et al., 1988).

There are additional potential strengths and insights provided by this study design. We modified the BIQ to a retrospective parent report in an attempt to, at least partially, capture the mother’s recollection of her child’s BI at an earlier age. That version was shown to be similarly reliable and valid as prior versions of the BIQ (however also see limitations below). Additionally, treating the included phenotypes as quantitative traits provided unique advantages. Statistical power to detect effects with this method was generally increased compared with binary categories. The use of quantitative measures of psychopathology is consistent with recent efforts by the National Institute of Mental Health to shift research toward dimensional constructs that potentially cut across diagnostic boundaries (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013; Insel et al., 2010). Finally, our finding suggests that retrospective parent report of BI assesses a strongly heritable form of inhibited temperament in this age group. This adds genetic evidence to existing rationale for measuring BI in early childhood and provides further support that parent report is a viable approach to assessing the trait when direct laboratory assessment is unavailable (Bishop et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2012).

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, using a retrospective report of BI could have limited the reliability and validity of the measured trait due to recall biases such as parents of high-anxiety preadolescents reporting higher levels of early BI (McPhail & Haines, 2010). However, there is little evidence that such potential bias in retrospective reports outweighs their utility (Hardt & Rutter, 2004). This limitation, together with moderate stability of BI over development (Fox et al., 2005), suggests that our assessment likely provides a compromise between past and current inhibition severity. Second, the use of the BIQ to index BI only moderately aligned with BI obtained by behavioral observation methods. As already mentioned, however, the BIQ is a reliable measure of inhibited temperament that has often been used in recent studies of BI (i.e., Bishop et al., 2003; Broeren & Muris, 2010; Clauss et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2015; Hudson & Dodd, 2012; Kennedy et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Morales et al., 2017; Taber-Thomas et al., 2016; Vreeke et al., 2012). Third, our findings may not be generalizable to a wider population since the sample was made up of entirely Caucasian participants selected to limit genetic variance for the larger aims of the study (Carney et al., 2016). Fourth, twin direction-of-causation models ideally should examine phenotypes with different sources of variance (Gillespie & Martin, 2005; Heath et al., 1993; Verhulst & Estabrook, 2012). The sources of variance between BI and social anxiety symptoms were the same (additive genetics and unique environment) but of sufficiently different magnitudes to make the model appropriate for use in the current study. Finally, the DZ correlations for BI and social anxiety symptoms were low and not significantly different from zero (see Table 2). This has also been reported in past studies in which BI was assessed via behavioral observation (Plomin et al., 1993; Robinson et al., 1992; Smith et al., 2012), suggesting this may likely be inherent in various measures of BI. There are a few possible explanations for this, which we address in the supplemental text.

Conclusions

This was the first study to examine the relationship between childhood BI and a broad array of preadolescent anxiety symptom clusters from a genetic epidemiological perspective. Of the anxiety symptoms examined, only social anxiety shared a significant proportion of genetic and environmental factors with childhood BI. It also found tentative evidence for a potentially causal pathway that partially explains the relationship between these two phenotypes, expanding extant knowledge about the progression of BI and the etiology of social anxiety. Current findings support and extend past research indicating that childhood BI is most robustly a risk factor for later social anxiety, despite associations with other anxiety domains. They also suggest that childhood BI and later social anxiety disorder are related but distinct phenotypes, with early BI functioning as a potential developmental endophenotype for later social anxiety. While current treatment implications are unclear, such research adds etiological insight into anxiety risk prediction that may be useful for clinicians to consider. Future studies in this line of research could expand the clinical impact of this work by informing clinicians’ treatment decisions. For example, the specific mechanisms of the relationship between BI and social anxiety need further exploration, including the developmental progression to social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Such knowledge can help to guide early intervention and prevention efforts aimed at social anxiety outcomes in middle to late childhood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to thank all children and parents of the Virginia Commonwealth University Juvenile Anxiety Study for their participation.

Financial support. The Virginia Commonwealth University Juvenile Anxiety Study was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants NIH-R01MH098055 (PI: J.M.H.) and NIMH-IRP-ziamh002781 (PI: D.S.P.). J.L.B. was supported by the NIMH grant T32MH020030 (PI: M. Neale).

Footnotes

Supplementary material. To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/S1832427418000737.

Conflict of interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Akaike H (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52, 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, … Faraone SV (2001). Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1673–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, & Neer SM (1997). The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop G, Spence SH, & McDonald C (2003). Can parents and teachers provide a reliable and valid report of behavioral inhibition? Child Development, 74, 1899–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeren S, & Muris P (2010). A psychometric evaluation of the behavioral inhibition questionnaire in a non-clinical sample of Dutch children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 214–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, & Keller MC (2006). Endophenotypes in the genetic analyses of mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 267–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney DM, Moroney E, Machlin L, Hahn S, Savage JE, Lee M, … Hettema JM (2016). The twin study of negative valence emotional constructs. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 19, 456–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, … Fox NA (2009). Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 928–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, Avery SN, & Blackford JU (2015). The nature of individual differences in inhibited temperament and risk for psychiatric disease: A review and meta-analysis. Progress in Neurobiology, 127–128, 23–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, Benningfield MM, Rao U, & Blackford JU (2016). Altered prefrontal cortex function marks heightened anxiety risk in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 55, 809–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, & Blackford JU (2012). Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 1066–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, & Insel TR (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: The seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine, 11, 126–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, & Kazdin AE (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson MW, Klein DN, Olino TM, Dougherty LR, & Durbin CE (2011). Social and nonsocial behavioral inhibition in preschool-age children: Differential associations with parent-reports of temperament and anxiety. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 42, 390–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SL, Rapee RM, & Kennedy S (2010). Prediction of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: Examinations of maternal and paternal perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Plomin R, Robinson J, Corley R, DeFries J, Fulker DW, … Zahn-Waxler C (1992). Temperament, emotion, and cognition at fourteen months: The MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study. Child Development, 63, 1437–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Klein MH, Slattery MJ, Goldsmith HH, & Kalin NH (2010). Early risk factors and developmental pathways to chronic high inhibition and social anxiety disorder in adolescence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, & Ghera MM (2005). Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 235–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel TI, Fox NA, Pine DS, Walker OL, Degnan KA, & Chronis-Tuscano A (2015). Early childhood behavioral inhibition, adult psychopathology and the buffering effects of adolescent social networks: A twenty-year prospective study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 1065–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Taber-Thomas BC, & Perez-Edgar K (2015). Frontolimbic functioning during threat-related attention: Relations to early behavioral inhibition and anxiety in children. Biological Psychology, 122, 98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Kagan J, & Reznick JS (1984). Behavioral inhibition in young children. Child Development, 55, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie NA, & Martin NG (2005). Direction of causation models In Everitt BS & Howell DC (Eds.), Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science (pp. 1363–1370). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II, & Gould TD (2003). The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: Etymology and strategic intentions. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, & Rutter M (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Kesler RC, Neale MC, Hewitt JK, Eaves LJ, & Kendler KS (1993). Testing hypotheses about direction of causation using cross-sectional family data. Behavior Genetics, 23, 29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Farone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, & Rosenbaum JF (2007). Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: A five-year follow-up. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 28, 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, Bloomfield A, Biederman J, & Rosenbaum J (2008). Behavioral inhibition. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, & Dodd HF (2012). Informing early intervention: Preschool predictors of anxiety disorders in middle childhood. PLoS ONE, 8, e42359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, … Wang P (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 748–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick S, & Snidman N (1988). Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science, 240, 167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J (2012). The biography of behavioral inhibition In Zentner M & Shiner RL (Eds.), Handbook of Temperament (pp. 69–82). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N, Zentner M, & Peterson E (1999). Infant temperament and anxious symptoms in school age children. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SJ, Rapee RM, & Edwards SL (2009). A selective intervention program for inhibited preschool-aged children of parents with an anxiety disorder: Effects on current anxiety disorders and temperament. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Klein DN, Olino TM, Dyson MW, Doughtery LR, & Durbin CE (2011). Psychometric properties of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire in preschool children. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 545–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Singh AL, Waldman ID, & Rathouz PJ (2011). Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley EC, & Silberg JL (2013). The mid-atlantic twin registry, revisited. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16, 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NG, Eaves LJ, Kearsey MJ, & Davies P (1978). The power of the classical twin study. Heredity, 40, 97–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhail S, & Haines T (2010). Response shift, recall bias, and their effect on measuring change in health-related quality of life amongst older hospital patients. Health and Quality Outcomes, 8, 65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Taber-Thomas BC, & Perez-Edgar KE (2017). Patterns of attention to threat across tasks in behaviorally inhibited children at risk for anxiety. Developmental Science, 20, e12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach I, Wessel M, & van de Ven M (1999). Psychopathological correlates of self-reported behavioural inhibition in normal children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, van Braken AML, Arntz A, & Schouten E (2011). Behavioral inhibition as a risk factor for the development of childhood anxiety disorders: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Family Studies, 20, 157–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, & Cardon LR (1992). Methodology for genetic studies of twin and families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ogliari A, Citterio A, Zanoni A, Fagnani C, Patriarca V, Cirrincione R, … Battaglia M (2006). Genetic and environmental influences on anxiety dimensions in Italian twins evaluated using the SCARED questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20, 760–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogliari A, Spatola CA, Presenti-Gritti P, Medda E, Penna L, Sazi MA, … Fagnani C (2010). The role of genes and environment in shaping co-occurrence of DSM-IV defined anxiety dimensions among Italian twins aged 8–17. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OpenMx Development Team. (2011). OpenMx official documentation. Retrieved from http://openmx.psyc.virginia.edu/docs/OpenMx/latest/

- Paulus FW, Backes A, Sander CS, Weber M, & von Gontard A (2015). Anxiety disorders and behavioral inhibition in preschool children: A population-based study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46, 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Kagan J, Emde RN, Reznick JS, Braungart JM, Robinson J, … DeFries JC (1993). Genetic change and continuity from fourteen to twenty months: The MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study. Child Development, 64, 1354–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Schniering CA, & Hudson JL (2009). Anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence: Origins and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 311–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, & Spence SH (2004). The etiology of social phobia: Empirical evidence and an initial model. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 737–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JL, Kagan J, Reznick JS, & Corley R (1992). The heritability of inhibited and uninhibited behavior: A twin study. Developmental Psychology, 28, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Scaini S, Belotti R, & Ogliari A (2014). Genetic and environmental contributions to social anxiety across different ages: A meta-analytic approach to twin data. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, & Kagan J (1999). Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AK, Rhee SH, Corley RP, Friedman NP, Hewitt JK, & Robinson JL (2012). The magnitude of genetic and environmental influences on parental and observational measures of behavioral inhibition and shyness in toddlerhood. Behavioral Genetics, 42, 764–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber-Thomas BC, Morales S, Hillary FG, & Perez-Edgar KE (2016). Altered topography of intrinsic functional connectivity in childhood risk for social anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 995–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst B, & Estabrook R (2012). Using genetic information to test causal relationships in cross-sectional data. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 24, 238–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeke LJ, Muris P, Mayer B, Huijding J, Bos AER, van der Veen M, … Verjeij F (2012). The assessment of an inhibited, anxiety-prone temperament in a Dutch multi-ethnic population of preschool children. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 21, 623–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilks SS (1938). The large-sample distribution of the likelihood ratio for testing composite hypotheses. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 9, 670–672 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.