Abstract

The mammalian intestine is colonized by over a trillion microbes that comprise the “gut microbiota,” a microbial community which has co-evolved with the host to form a mutually beneficial relationship. Accumulating evidence indicates that the gut microbiota participates in immune system maturation and also plays a central role in host defense against pathogens. Here we review some of the mechanisms employed by the gut microbiota to boost the innate immune response against pathogens present on epithelial mucosal surfaces. Antimicrobial peptide secretion, inflammasome activation and induction of host IL-22, IL-17, and IL-10 production are the most commonly observed strategies employed by the gut microbiota for host anti-pathogen defense. Taken together, the body of evidence suggests that the host gut microbiota can elicit innate immunity against pathogens.

Keywords: gut microbiota, host innate immunity, antimicrobial peptides, inflammasome, IL-22, IL-17, IL-10

Introduction

The mammalian intestine is home to a complex and dynamic population of microorganisms, termed the “gut microbiota” (1, 2). These microorganisms, which co-evolved with the host as part of a mutually beneficial relationship (3), include bacteria, fungi and viruses (4, 5). Accumulating evidence indicates that the gut microbiota can participate in the maturation and function of the innate immune system, while also playing many complex roles in the host defense against pathogens (6). On the one hand, the gut microbiota can help repair intestinal mucosal barrier damage (7, 8); on the other hand, gut microbiota mediates host anti-pathogen defenses (9).

In the past decade, studies of germ-free (GF) mice have provided clues to elucidate the complexity of the intestinal microbiota (10, 11) and its importance to host health (12, 13). Mounting research shows that at least a thousand different gut microbiota species, such as Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and others, contribute to host defense against harmful microorganisms (14, 15).

Recently, several studies have begun to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying how the gut microbiota regulates host innate immunity against pathogens (16, 17), including a role in helping the host resist pathogen colonization. In this review, we summarize the main mechanisms by which commensal bacteria, including certain probiotic species, actively prevent pathogen colonization of the host.

Gut Microbiota and Antimicrobial Peptides

Defensins

The α-defensins, microbicidal peptides mainly produced by Paneth cells, are key components of innate immunity. They control pathogen growth within the intestine (18–20) and their production can be directly elicited by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, as well as by bacterial metabolites (e.g., lipopolysaccharide, lipoteichoic acid, lipid A, and muramyl dipeptide) (21–23). By contrast, live fungi and protozoa do not appear to stimulate Paneth cells and thus fail to elicit Paneth cell degranulation (21). Nevertheless, recent research has found that the gut microbiota plays an important role in induction of α-defensins expression against pathogens (24). In one in vitro study, live E. coli or S. aureus, live or dead S. typhimurium, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipid A, lipoteichoic acid (LTA), or liposomes could stimulate isolated intact intestinal crypts, demonstrating that intestinal Paneth cells may contribute to α-defensins secretion by sensing the presence of exogenous bacteria and bacterial antigens (21). To investigate whether gut microbiota possess the same or similar functions, Shipra Vaishnava and colleagues used a CR2-MyD88 Tg mouse model, whereby Paneth cells were the sole cell lineage expressing MyD88, to demonstrate that Paneth cells may directly sense enteric bacteria to trigger the MyD88-dependent antimicrobial program. Furthermore, increased numbers of Salmonella were observed to be internalized by mesenteric lymph node (MLN) cells of MyD88−/− and germ-free mice as compared to corresponding numbers observed for wild-type mice (25). Similarly, transcriptional profiles have shown that α-defensin gene (Defa) transcripts were less abundant in intestinal microbiota-free mice and TLRs-deficient or MyD88-deficient mice, but could be recovered after stimulation with toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, specifically agonists of TLR2 or TLR4 (26). Thus, commensal microbiota appears to protect the host against pathogen invasion by triggering enteric Paneth cell TLR-MyD88 signaling. Notably, this mechanism is distinct from the NOD2-dependent antimicrobial response (25, 27, 28), since the former mechanism entails triggering of expression of multiple antimicrobial factors (25). However, several human-based studies have demonstrated that mutations in the NOD2 peptidoglycan sensor actually did reduce secretion of α-defensins (29–33). Therefore, these contradictory human and mouse study results warrant further research. Notably, another study has demonstrated that Cd1d−/− mice exhibited a defect in Paneth cell granule ultrastructure that specifically resulted in an inability to degranulate after bacterial colonization, with an increased load of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) also noted (34). Thus, no clear evidence demonstrates that CD1d mediates regulation of gut microbiota via α-defensins expression.

Meanwhile, more recent research has begun to examine the mechanism of how the gut microbiota influences α-defensins secretion. Studies using the Caco-2 IEC line have demonstrated that lactic acid strongly suppresses transcription of the α-defensin gene, while cecal content may include as yet unidentified factors which enhance concomitant α-defensin 5 expression (35). However, contrary to the aforementioned results, Menendez et al. found that Defa expression was partially restored in vivo by lactobacillus administration to antibiotic-treated mice (26). Notably, an emerging role of vitamin D, a lactobacillus metabolite, has been recently discovered that exerts an effect opposite on α-defensins expression to that exerted by lactate (36, 37). To reconcile these results, Su et al. used a mouse model and certain feed formulations to demonstrate that VDD- and HFD ± VDD-fed mice exhibited reduced levels of expression of α-defensin and MMP7 (a metalloproteinase that can proteolytically convert pro-α-defensins to their mature and active forms) within ileal crypts as compared to results for control and HFD groups. Moreover, their results demonstrated a critical role of vitamin D signaling in maintaining steady-state expression of α-defensins and MMP7 under physiological conditions. Subsequently, Su et al. have demonstrated that dietary vitamin D deficiency resulted in loss of Paneth cell-specific α-defensins, which may lead to intestinal dysbiosis and endotoxemia (38). Of note, oral administration of α-defensin suppressed Helicobacter hepaticus growth in vivo (38). Meanwhile, using complementary mouse models of defensin deficiency (MMP7−/−) and surplus (HD5+/+), Salzman noted defensin-dependent reciprocal shifts in proportions of dominant bacterial species within the small intestine with no changes in total bacterial numbers observed (Table 1). Upon further research, this group observed that mice overexpressing HD5 exhibited a significant loss of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), resulting in reduced numbers of Th17 cells within the lamina propria (48). However, direct evidence implicating the involvement of SFB in α-defensin production is still lacking and studies on α-defensin regulation by specific commensal microorganisms are still rare, warranting further research. Nevertheless, in view of existing research results, we believe that the discovery of specific microorganisms through research focusing on specific metabolic pathways may be a more fruitful approach.

Table 1.

Gut microbiota protects the host against pathogen infections and the relevant mechanisms.

| Pathogens | Gut microbiota | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helicobacter hepaticus | Lactobacillus | Inducing α-defensin production from Paneth cells | (38) |

| S. aureus S. pyogenes P. aeruginosa E. coli C. albicans | Lactobacillus acidophilus PZ 1129 Lactobacillus acidophilus PZ 1130 Lactobacillus paracasei Lactobacillus plantarum E. coli K-12 E. coli Nissle 1917 | Inducing β-defensin production | (39–42) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae Citrobacter rodentium Enterococcus Plasmodium chabaudi | L. reuteri Allobaculum spp Clostridium spp Bacteroides spp | Inducing IL-22 production | (43–46) |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Bacteroides | Inducing IL-17 production | (47) |

With regard to β-defensins, which directly kill or inhibit the growth of microorganisms (49), these agents have been shown to exert antimicrobial activity against some species of enteric pathogenic Gram-positive S. aureus and S. pyogenes, as well as against Gram-negative P. aeruginosa, E. coli and the yeast C. albicans (50). In fact, accumulating evidence has shown that, similarly to α-defensins, β-defensins secretion is also regulated by the gut microbiota. For example, using in vitro studies of HT-29 and Caco-2 human colon epithelial cell lines, human fetal intestinal xenografts have been observed to constitutively express hBD-1 but not hBD-2, with upregulation of only the latter in xenografts intraluminally infected with Salmonella (51). Meanwhile, it has been independently shown that preincubation of Caco-2 cells with live E. faecium significantly reduced S. typhimurium internalization by 45.8%, while heat-killed E. faecium pretreatment had no effect on pathogen internalization (49). This result aligns with the latest research, which has shown that only live gut microbiota, as modeled using Lactobacillus acidophilus PZ 1129 and PZ 1130, Lactobacillus paracasei, Lactobacillus plantarum, E. coli K-12, and E. coli Nissle 1917, can strongly induce expression of hBD-2 in Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner (39–42) (Table 1). Notably, the E. coli strain Nissle 1917, a non-pathogenic Gram-negative strain isolated in 1917 by Alfred Nissle, elicited the most marked expression of induced β-defensin expression in vitro (39–42). Interestingly, Schlee et al. constructed several E. coli Nissle 1917 deletion mutants and pinpointed flagellin as the major stimulatory factor for triggering of β-defensin secretion in the presence of that strain (40). Meanwhile, Wehkamp et al. and others have found that E. coli Nissle 1917-induced β-defensin expression in cell culture was mediated by NF-κB- and MAPK/AP-1-dependent pathways (39–42). Nevertheless, in vivo studies are still needed to confirm if gut microbiota can induce β-defensins expression to reduce pathogen colonization and control gut homeostasis (Table 1). Recently, to further clarify the relationship between gut microbiota and β-defensin secretion, Miani et al. used a mouse model and antibiotic treatment experiments to study the participation of dysbiotic microbiota and a low-affinity aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) allele in the defective pancreatic expression of mBD14 observed in NOD mice. By utilizing 16S rDNA gene sequencing and AHR ligand activity measurements, they demonstrated that gut microbiota-derived molecules, including AHR ligands and butyrate, promoted IL-22 secretion by pancreatic ILCs that subsequently induced mBD14 expression by endocrine cells. Therefore, dysbiotic microbiota and a low-affinity AHR allele appear to explain defective pancreatic mBD14 expression of mBD14 in NOD mice (24). Because only live gut microbiota can stimulate secretion of β-defensins, we believe that specific gut microbiota that possess special metabolic pathway functionality, including pathways for secretion of AHR ligands, may possess the ability to regulate secretion of β-defensins.

C-Type Lectins

The C-type lectins, also key components of innate immunity that control growth of enteric pathogens (52–54), are expressed by multiple small intestinal epithelial lineages (55, 56). REG3γ and REG3β, two C-type lectins, provide protection against infection by specific bacterial pathogens, including Enterococcus faecalis (57–59), Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (60, 61), and Listeria monocytogenes (57). Notably, additional evidence suggests that C-type lectins actually mediate syncytium endosymbiont defenses through prevention of pathogen colonization. To further demonstrate how these lectins control bacterial colonization of the intestinal epithelial surface, Vil-Myd88Tg mice (mice with IEC-restricted Myd88 expression) were used to determine whether surface Myd88 present on epithelial cells was sufficient to restrain bacterial colonization (55). The results showed that secretion of C-type lectins required both activation of the MyD88 pathway (62) and recognition of syncytium endosymbionts by TLRs (63). Furthermore, Earle et al. used a pipeline method to assess intestinal microbiota localization within immunofluorescence images of fixed gut cross-sections. The results indicated that elimination of dietary microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs) resulted in thinning of mucus within the distal colon that increased microbial proximity to the epithelium and heightened inflammatory marker REG3β expression (64). These results align with those from an earlier study of transcriptional profiles of duodenum, jejunum, ileum and colon samples, which demonstrated that MyD88 was essential for syncytium endosymbiont-induced colonic epithelial expression of antimicrobial genes Reg3β and Reg3γ, with Myd88 deficiency associated with both a shift in bacterial diversity and a greater proportion of SFB in the small intestine (65). In fact, other research found that conventionally raised Myd88−/− mice exhibited increased expression of antiviral genes in the colon, which correlated with norovirus infection of the colonic epithelium (65). Therefore, it can be concluded that both the activation of the MyD88 pathway and recognition of syncytium endosymbionts by TLRs are indispensable for triggering C-type lectins secretion (Figure 1). Recently, Ju et al. used antibiotic-treated mice to study differences between metronidazole-treated and control groups, and observed reduced abundance of Turicibacteraceae, overgrowth of E. coli and higher levels of Reg3β and Reg3γ mRNA for the metronidazole-treated group (66). These results provide a basis for the study of the effects of specific gut syncytium endosymbiont organisms on C-type lectins secretion.

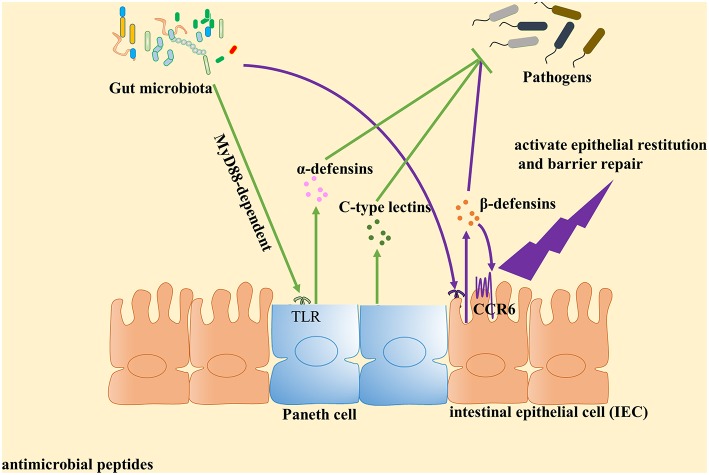

Figure 1.

Gut microbiota plays an important role in the induction of antimicrobial peptides expression against pathogens. Antimicrobial peptides are key components of innate immunity to control pathogen growth within the intestine. Accumulated evidence identified that gut microbiota can contribute to the expression of antimicrobial peptides and play a central role in host defense against pathogens. Paneth cells could directly sense gut microbiota through cell-autonomous myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)-dependent toll-like receptor (TLR) activation, triggering expression of α-defensins and C-type lectins. With regard to β-defensin, gut microbiota induce β-defensin expression in cell culture mediated by NF-κB- and MAPK/AP-1-dependent pathways in vitro. Then β-defensin interacts with intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) through CCR6 to activate epithelial restitution and barrier repair.

Other accumulating evidence has shown that the mammalian gut contains a rich fungal community that interacts with the immune system through the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1. To demonstrate whether symbiotic fungi influence C-type lectins secretion that prevents pathogen colonization, Iliev et al. studied mice lacking Dectin-1 and observed increased susceptibility to chemically induced colitis due to altered responses to indigenous fungi. Moreover, in humans they identified a gene polymorphism for Dectin-1 (CLEC7A) that is strongly linked to a severe form of ulcerative colitis (67). Independently, Eriksson et al. found that CLR-specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing non-integrin homolog-related 3 (SIGNR3) is the closest murine homolog to the human dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) receptor. Both receptors recognize similar carbohydrate ligands, such as terminal fucose or high-mannose glycans. Notably, using the dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis model, IGNR3 has been observed to recognize fungal members of the commensal microbiota, with SIGNR3−/− mice exhibiting a higher level of TNF-α in colon (68). Therefore, symbiotic fungi appear to communicate with the host via the C-type lectin receptor to maintain intestinal homeostasis. However, as yet no direct evidence has been found to determine whether symbiotic fungi can regulate selectin secretion, warranting further research.

Gut Microbiota Elicits Inflammasome Activation Against Pathogens

Inflammasome activation is an important innate immune pathway that prevents pathogen invasion via secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, as well as through induction of pyroptosis (69–74). It is well-documented that inflammasomes come from two main sources, namely myeloid- and epithelial-derived inflammasomes. While they share several common features, it should be noted that inflammasomes of distinct origins may exhibit different features and effector functions. For example, from a mechanistic of view, macrophage- and epithelial cell-derived inflammasomes are activated with different intermediate processes. While IL-18 processing is dependent on caspase-11 in IECs, caspase-1 is responsible for the processing of IL-18 in myeloid cells (75). In addition, compared with myeloid cells, IECs constitutively express IL-18, while produce little IL-1β (76–78). Moreover, unlike myeloid inflammasomes, IEC inflammasomes is capable of producing considerable amounts of prostaglandin upon activation (79). Intriguingly, the signaling circuitry between epithelial and myeloid inflammasomes are also different. For example, in homeostasis conditions, both NLRP3 and PYCARD genes have been shown to be highly expressed in murine primary macrophages, while mouse airway epithelial cells can only express a low level of PYCARD and cannot express NLRP3 (80).

Accumulating evidence suggests that gut microbiota can activate NLRC4 and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways against pathogens (81–83). Enterobacteriaceae and the pathobiont Proteus mirabilis, which are members of the normal flora of the human gastrointestinal tract (84, 85), were shown to induce robust IL-1β production through NLRP3 activation mediated by intestinal Ly6Chigh monocytes (86, 87). Indeed, recruited Ly6Chigh monocytes have been shown to express a variety of inflammasome components, such as NAIPs (71, 88, 89), NLRC4 (89), NLRP1 (90, 91), NLRP6 (92, 93), AIM2 (94), caspase-1 (95), caspase-4 (96) (in humans), ASC (93), and IL-18 (87, 97, 98). Meanwhile, Seo et al. have also demonstrated that Proteus mirabilis (a Proteobacteria phylum member) induced NLRP3 activation and IL-1β production (86). Interestingly, bacterial components from other Proteobacteria, such as LPS produced by Pseudomonas spp., have even been shown to induce host mental depression symptoms via NLRP3 inflammasome activation (99). Other interesting lines of research have shown that in addition to gut commensal bacteria, the mammalian gut contains a rich fungal community which also appears to activate the inflammasome pathway. This community includes the human commensal fungus Candida albicans (C. albicans), which colonizes gastrointestinal and vaginal tract mucosal surfaces and appears to promote inflammasome activation during AOM-DSS-induced colitis (100). In further support of this finding, direct peptide administration experiments had previously demonstrated that candidalysin, a peptide derived from the hypha-specific ECE1 gene, acted as a fungal trigger for NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated maturation that was sufficient for inducing IL-1β secretion mature macrophages in an NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent manner (101).

In recent studies, numerous other gut microbiota metabolites have also been demonstrated to elicit inflammasome pathways against pathogens. For example, gut microbiota-derived adenosine triphosphate (ATP) has been shown to co-operate with NLRP3 (also known as CIAS1) (102) via the macrophage P2X7 receptor (103) to induce assembly of a cytosolic protein complex containing ASK and caspase-1 (70, 104–106) that eventually leads to inflammasome activation (106). Another important gut microbiota metabolite, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), end products of fermentation of dietary fibers by anaerobic intestinal microbiota, have also been implicated in inflammasome activation (107). SCFAs binding to GPR43 on colonic epithelial cells to stimulate K+ efflux and hyperpolarization has been shown to lead to NLRP3 inflammasome activation, with subsequent acceleration of cell maturation and secretion of IL-1β (108) and IL-18 (77, 109).

Gut Microbiota Can Enhance Interleukin Expression to Clear Invading Pathogens

IL-22

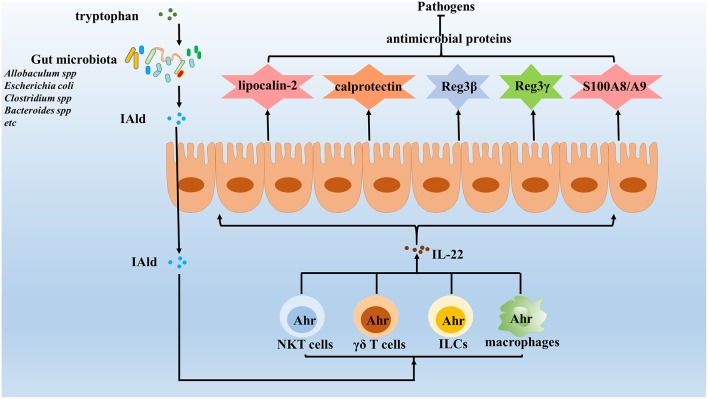

IL-22 is important in maintaining mucosal barrier integrity and is produced by many different types of innate immune cells (110–113). This cytokine has been shown to play a host-protective role during infection by a wide range of pathogens, including Klebsiella pneumoniae (114), Citrobacter rodentium (115, 116), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (117, 118) and Plasmodium chabaudi (119). One IL-22-dependent mechanism involved in pathogen clearance involves the increased presence of antimicrobial proteins within the mucosa (120) that include the following: calprotectin and lipocalin-2, the latter of which binds to the siderophore enterochelin, with both acting to limit iron availability in the gut (120); C-type lectins, which regenerate islet-derivative proteins Reg3β and Reg3γ that control some components of the microbiota (58, 120, 121); and S100A8 and S100A9, two antimicrobial peptides that heterodimerize to form calprotectin, an antimicrobial protein that sequesters zinc and manganese to prevent microbial access to these nutrients (122). Although epithelial antimicrobial defenses also exist, many pathogens can still colonize mucosal surfaces to establish infections (120, 123). Nevertheless, accumulated evidence has shown that IL-22 is rapidly induced in response to pathogen invasion through activation of host AhR via specific gut microbiota-derived molecules (Figure 2) (124, 125). For example, Lactobacillus species (specifically, L. reuteri) can activate IL-22 production by gut type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) (126–128), while other studies have shown that supplementation with three commensal Lactobacillus strains with high tryptophan-metabolizing activities was sufficient to restore intestinal IL-22 production (43, 129). Indeed, additional work has shown that Lactobacillus species could utilize tryptophan as an energy source and produce a metabolite, indole-3-aldehyde (IAld), which could then activate AhRs present on ILCs (126, 130). In addition to Lactobacillus strains, other recent studies have shown that Allobaculum spp. (43), Escherichia coli (44), Clostridium spp. (45), and Bacteroides spp. (46) can also utilize tryptophan to produce IAld and elicit IL-22 production (Table 1). Meanwhile, other studies have shown that activated ILCs secrete IL-22 to protect the host against opportunistic pathogens by reducing pathogen colonization (120, 131). In fact, other innate immune cells, such as NKT cells, γδ T cells and macrophages, have very recently been shown to secrete IL-22 under regulation by gut microbiota via the AhR pathway (132). Therefore, gut microbiota may prevent pathogen infection by collectively enhancing IL-22 expression via the AhR pathway.

Figure 2.

Gut microbiota enhance the expression of IL-22 against invading pathogens. IL-22 is important in maintaining the integrity of mucosal barriers and can be produced by many different types innate immune cells, which induce the expression of various antimicrobial proteins, including lipocalin-2, calprotectin, C-type lectins, S100A8, S100A9, and so on to clear pathogens. Increasing evidence identified that gut microbiota enhances the expression of IL-22 to protect the host against pathogens. The results show that gut microbiota utilize tryptophan as an energy source and produce a metabolite, indole-3-aldehyde (IAld), which in turns activated Ahr on innate immune cells. Once activated, innate immune cells will secrete IL-22, which protects the host against opportunistic pathogens by reducing their colonization.

IL-17

IL-17 is a well-established crucial cytokine that is involved in limiting invasion and dissemination of pathogens, including Salmonella typhimurium (133), by both recruitment of neutrophils and by the induction of production of antimicrobial peptides (131, 134). Recent studies have demonstrated that both the abundance and activation status of IL-17-producing intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) are modulated by commensal bacteria, with enrichment of the γδT cell population of IELs representing an important source of innate IL-17 production (135, 136). Notably, a comparative study of GF mice and SPF mice has shown that the number of TCRγδ IELs is decreased in GF mice (133). Moreover, in addition to the regulation of IELs numbers, the gut microbiota may also regulate activation of TCRγδ IELs, as reflected by a report showing that production of IL-17 by TCRγδ IELs is decreased in GF mice (137). Meanwhile, antibiotic-treatment and monocolonization of mice have been used to demonstrate that the great majority of γ/δ T cells within peritonea of SPF mice are CD62L− γδT cells, which are activated γδT cells, with GF mice possessing far fewer CD62L− γ/δ T cells than SPF mice (47). Notably, additional research suggests that specific commensal bacteria, excluding metronidazole-sensitive anaerobes, such as Bacteroides species, are required for maintaining IL-1R1± γδT cells (47), a result that aligns with previous research results by another research group (138) (Table 1). In conclusion, gut microbiota influences the abundance and activation status of IL-17-producing TCRγδ IELs to protect the host from pathogen infection and to maintain intestinal homeostasis. In addition, lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells and NCR− ILC3 cells also appear to function as important sources of innate IL-17 production (127). However, few studies have investigated how gut microbiota regulate these cell types, warranting further research in this area.

IL-10

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that plays a central role in regulating the host immune response to pathogens, thereby preventing host damage and maintaining normal tissue homeostasis (139–141). Accumulating evidence suggests that macrophages are an important source of innate IL-10 and that the gut microbiota plays a vital role in mucosal innate IL-10 generation under homeostatic conditions (142–144). For example, studies in GF mice and SPF mice have shown that colonic lamina propria from germ-free mice exhibited lower IL-10 production (142), a reduction later confirmed to be a 50% reduction in steady-state IL-10 levels (142–144). To elucidate the mechanism by which gut microbiota regulate intestinal macrophage IL-10 production, Hayashi et al. used macrophage-specific IL-10-deficient mice to demonstrate that Clostridium butyricum (CB), a distinct cluster I Clostridium strain, induces IL-10 production to ultimately prevent acute experimental colitis. However, while CB treatment had no effects on IL-10 production by T cells, IL-10-producing F4/80±CD11b±CD11cint macrophages accumulated within inflamed mucosa after CB treatment. Subsequently, more rigorous examination demonstrated that CB directly triggered IL-10 production by intestinal macrophages there via the TLR2/MyD88 pathway (144). Meanwhile, Ochi et al. recently found that dietary amino acids directly regulate Il-10 production by small intestine (SI) macrophages. Using mice fed via total parenteral nutrition, a significant decrease of IL-10-producing macrophages in the SI was observed, while IL-10-producing CD4± T cells remained intact. Likewise, enteral nutrient deprivation selectively decreased IL-10 production by the monocyte-derived F4/80± macrophage population, but had no effect on non-monocytic precursor-derived CD103± dendritic cells. Notably, in contrast to regulation of colonic macrophages, replenishment of SI macrophages and their IL-10 production were not regulated by gut microbiota (145). Contrary to results obtained under steady-state conditions, an injury model used to study participation of microbiota to explain observed IL-10 increases post-injury yielded different results. Specifically, comparison of Il10 mRNA levels in uninjured intact tissue and day-2 post-wound tissue isolated from SPF or GF mice indicated that IL-10 mRNA was induced in post-wound colonic tissue isolated from both SPF and GF mice. Therefore, injury-triggered IL-10 increases appeared to be largely microbiota independent (146), although the reasons remain unclear regarding the differing effects of the gut microbiota observed in different model systems. Nevertheless, we hypothesize that local damage-associated molecular proteins (DAMPs) may regulate immune cells more rapidly and strongly post-intestinal damage, resulting in either a failure of gut microbiota to temporally adjust or a masking of any microbiota-based regulatory effect.

Concluding Remarks

Gut microbiota resists colonization and growth of invading pathogens through the induction of expression of antimicrobial peptides, IL-22, IL-17, and IL-10 while eliciting inflammasome activation. Because the underlying mechanisms of how the gut microbiota resists pathogenic invasion still remain obscure, future studies are clearly needed to identify gut microbiota functions against various pathogens toward the development of promising strategies to treat infectious diseases. For instance, E. coli Nissle 1917 can induce β-defensin expression mediated by NF-κB- and MAPK/AP-1-dependent pathways (39), while Lactobacillus spp. activate IL-22 production against opportunistic pathogens to reduce colonization (147, 148). Therefore, transplanting suitable specific gut microbiota to compete with specific pathogens could be an effective defense strategy. However, since this strategy poses new disease risks, strategies that restore intestinal homeostasis and promote host immune system may serve to more safely clear pathogens. To this end, identifying specific gut microbiota functions and defining normal gut microbiota populations are necessary first steps toward development of safer strategies for strengthening host defenses against pathogens. Moreover, research on the function and mechanisms of gut microbiota metabolites may facilitate development of novel therapeutic strategies to combat drug-resistant pathogens.

Author Contributions

D-KC, W-TM, H-YC, and M-XN designed the structure of the mini-review. H-YC and M-XN wrote the manuscript and drafted the first version of the manuscript. M-XN and W-TM helped revise the manuscript. All authors have reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by the Qinghai province Major R&D and Transformation Project (2018-NK-125), Xianyang Science and Technology Major Project (2017K01-34), Key industrial innovation chains of Shaanxi province (2018ZDCXL-NY-01-06) and PhD research startup fund of Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University (00500/Z109021716).

References

- 1.Jandhyala SM, Talukdar R, Subramanyam C, Vuyyuru H, Sasikala M, Nageshwar Reddy D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol. (2015) 21:8787–803. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luthold RV, Fernandes GR, Franco-de-Moraes AC, Folchetti LG, Ferreira SR. Gut microbiota interactions with the immunomodulatory role of vitamin D in normal individuals. Metabolism. (2017) 69:76–86. 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayres JS. Cooperative microbial tolerance behaviors in host-microbiota mutualism. Cell. (2016) 165:1323–31. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foca A, Liberto MC, Quirino A, Marascio N, Zicca E, Pavia G. Gut inflammation and immunity: what is the role of the human gut virome? Mediators Inflamm. (2015) 2015:326032. 10.1155/2015/326032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen B, Chen H, Shu X, Yin Y, Li J, Qin J, et al. Presence of segmented filamentous bacteria in human children and its potential role in the modulation of human gut immunity. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:1403. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. (2014) 157:121–41. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okumura R, Takeda K. Roles of intestinal epithelial cells in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Exp Mol Med. (2017) 49:e338. 10.1038/emm.2017.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okumura R, Takeda K. Maintenance of intestinal homeostasis by mucosal barriers. Inflamm Regen. (2018) 38:5. 10.1186/s41232-018-0063-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ubeda C, Djukovic A, Isaac S. Roles of the intestinal microbiota in pathogen protection. Clin Transl Immunol. (2017) 6:e128. 10.1038/cti.2017.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biedermann L, Rogler G. The intestinal microbiota: its role in health and disease. Eur J Pediatr. (2015) 174:151–67. 10.1007/s00431-014-2476-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goulet O. Potential role of the intestinal microbiota in programming health and disease. Nutr Rev. (2015) 73 Suppl. 1:32–40. 10.1093/nutrit/nuv039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tojo R, Suarez A, Clemente MG, de los Reyes-Gavilan CG, Margolles A, Gueimonde M, et al. Intestinal microbiota in health and disease: role of bifidobacteria in gut homeostasis. World J Gastroenterol. (2014) 20:15163–76. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kataoka K. The intestinal microbiota and its role in human health and disease. J Med Invest. (2016) 63:27–37. 10.2152/jmi.63.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevers D, Knight R, Petrosino JF, Huang K, McGuire AL, Birren BW, et al. The human microbiome project: a community resource for the healthy human microbiome. PLoS Biol. (2012) 10:e1001377. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. (2016) 8:51. 10.1186/s13073-016-0307-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim MY, You HJ, Yoon HS, Kwon B, Lee JY, Lee S, et al. The effect of heritability and host genetics on the gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. Gut. (2017) 66:1031–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monedero V, Buesa J, Rodriguez-Diaz J. The interactions between host glycobiology, bacterial microbiota, and viruses in the gut. Viruses. (2018) 10:96. 10.3390/v10020096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamond G, Beckloff N, Weinberg A, Kisich KO. The roles of antimicrobial peptides in innate host defense. Curr Pharm Des. (2009) 15:2377–92. 10.2174/138161209788682325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. (2012) 336:1268–73. 10.1126/science.1223490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim D, Zeng MY, Nunez G. The interplay between host immune cells and gut microbiota in chronic inflammatory diseases. Exp Mol Med. (2017) 49:e339. 10.1038/emm.2017.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayabe T, Satchell DP, Wilson CL, Parks WC, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Secretion of microbicidal alpha-defensins by intestinal Paneth cells in response to bacteria. Nat Immunol. (2000) 1:113–8. 10.1038/77783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elphick DA, Mahida YR. Paneth cells: their role in innate immunity and inflammatory disease. Gut. (2005) 54:1802–9. 10.1136/gut.2005.068601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanabe H, Ayabe T, Bainbridge B, Guina T, Ernst RK, Darveau RP, et al. Mouse paneth cell secretory responses to cell surface glycolipids of virulent and attenuated pathogenic bacteria. Infect Immun. (2005) 73:2312–20. 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2312-2320.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miani M, Le Naour J, Waeckel-Enee E, Verma SC, Straube M, Emond P, et al. Gut microbiota-stimulated innate lymphoid cells support beta-defensin 14 expression in pancreatic endocrine cells, preventing autoimmune diabetes. Cell Metab. (2018) 28:557–72.e6. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Ismail AS, Eckmann L, Hooper LV. Paneth cells directly sense gut commensals and maintain homeostasis at the intestinal host-microbial interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008) 105:20858–63. 10.1073/pnas.0808723105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menendez A, Willing BP, Montero M, Wlodarska M, So CC, Bhinder G, et al. Bacterial stimulation of the TLR-MyD88 pathway modulates the homeostatic expression of ileal Paneth cell alpha-defensins. J Innate Immun. (2013) 5:39–49. 10.1159/000341630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacDonald TT, Monteleone I, Fantini MC, Monteleone G. Regulation of homeostasis and inflammation in the intestine. Gastroenterology. (2011) 140:1768–75. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong S, Zhang YH, Zhang W. Regulation of intestinal epithelial cells properties and functions by amino acids. Biomed Res Int. (2018) 2018:2819154. 10.1155/2018/2819154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petnicki-Ocwieja T, Hrncir T, Liu YJ, Biswas A, Hudcovic T, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, et al. Nod2 is required for the regulation of commensal microbiota in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2009) 106:15813–8. 10.1073/pnas.0907722106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramanan D, Tang MS, Bowcutt R, Loke P, Cadwell K. Bacterial sensor Nod2 prevents inflammation of the small intestine by restricting the expansion of the commensal Bacteroides vulgatus. Immunity. (2014) 41:311–24. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanahan MT, Carroll IM, Grossniklaus E, White A, von Furstenberg RJ, Barner R, et al. Mouse Paneth cell antimicrobial function is independent of Nod2. Gut. (2014) 63:903–10. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan G, Zeng B, Zhi FC. Regulation of human enteric alpha-defensins by NOD2 in the Paneth cell lineage. Eur J Cell Biol. (2015) 94:60–6. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keestra-Gounder AM, Byndloss MX, Seyffert N, Young BM, Chavez-Arroyo A, Tsai AY, et al. NOD1 and NOD2 signalling links ER stress with inflammation. Nature. (2016) 532:394–7. 10.1038/nature17631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nieuwenhuis EE, Matsumoto T, Lindenbergh D, Willemsen R, Kaser A, Simons-Oosterhuis Y, et al. Cd1d-dependent regulation of bacterial colonization in the intestine of mice. J Clin Invest. (2009) 119:1241–50. 10.1172/JCI36509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugi Y, Takahashi K, Kurihara K, Nakano K, Kobayakawa T, Nakata K, et al. a-Defensin 5 gene expression is regulated by gut microbial metabolites. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. (2017) 81:242–8. 10.1080/09168451.2016.1246175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jerzynska J, Stelmach W, Balcerak J, Woicka-Kolejwa K, Rychlik B, Blauz A, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and vitamin D supplementation on the immunologic effectiveness of grass-specific sublingual immunotherapy in children with allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. (2016) 37:324–34. 10.2500/aap.2016.37.3958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang M, Sun J. Vitamin D/VDR, probiotics, and gastrointestinal diseases. Curr Med Chem. (2017) 24:876–87. 10.2174/0929867323666161202150008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su D, Nie Y, Zhu A, Chen Z, Wu P, Zhang L, et al. Vitamin D signaling through Induction of Paneth cell defensins maintains gut microbiota and improves metabolic disorders and hepatic steatosis in animal models. Front Physiol. (2016) 7:498. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Wehkamp K, Wehkamp-von Meissner B, Schlee M, Enders C, et al. NF-kappaB- and AP-1-mediated induction of human beta defensin-2 in intestinal epithelial cells by Escherichia coli Nissle 1917: a novel effect of a probiotic bacterium. Infect Immun. (2004) 72:5750–8. 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5750-5758.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlee M, Wehkamp J, Altenhoefer A, Oelschlaeger TA, Stange EF, Fellermann K. Induction of human beta-defensin 2 by the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is mediated through flagellin. Infect Immun. (2007) 75:2399–407. 10.1128/IAI.01563-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steubesand N, Kiehne K, Brunke G, Pahl R, Reiss K, Herzig KH, et al. The expression of the beta-defensins hBD-2 and hBD-3 is differentially regulated by NF-kappaB and MAPK/AP-1 pathways in an in vitro model of Candida esophagitis. BMC Immunol. (2009) 10:36. 10.1186/1471-2172-10-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seo EJ, Weibel S, Wehkamp J, Oelschlaeger TA. Construction of recombinant E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) strains for the expression and secretion of defensins. Int J Med Microbiol. (2012) 302:276–87. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Etienne-Mesmin L, Chassaing B, Gewirtz AT. Tryptophan: A gut microbiota-derived metabolites regulating inflammation. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. (2017) 8:7–9. 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devlin AS, Marcobal A, Dodd D, Nayfach S, Plummer N, Meyer T, et al. Modulation of a circulating uremic solute via rational genetic manipulation of the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. (2016) 20:709–15. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roager HM, Licht TR. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:3294. 10.1038/s41467-018-05470-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee JS, Cella M, McDonald KG, Garlanda C, Kennedy GD, Nukaya M, et al. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat Immunol. (2011) 13:144–51. 10.1038/ni.2187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duan J, Chung H, Troy E, Kasper DL. Microbial colonization drives expansion of IL-1 receptor 1-expressing and IL-17-producing gamma/delta T cells. Cell Host Microbe. (2010) 7:140–50. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salzman NH. Paneth cell defensins and the regulation of the microbiome: detente at mucosal surfaces. Gut Microbes. (2010) 1:401–6. 10.4161/gmic.1.6.14076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fusco A, Savio V, Cammarota M, Alfano A, Schiraldi C, Donnarumma G. Beta-Defensin-2 and Beta-Defensin-3 reduce intestinal damage caused by Salmonella typhimurium modulating the expression of cytokines and enhancing the probiotic activity of Enterococcus faecium. J Immunol Res. (2017) 2017:6976935. 10.1155/2017/6976935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harder J, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. Isolation and characterization of human beta -defensin-3, a novel human inducible peptide antibiotic. J Biol Chem. (2001) 276:5707–13. 10.1074/jbc.M008557200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Neil DA, Porter EM, Elewaut D, Anderson GM, Eckmann L, Ganz T, et al. Expression and regulation of the human beta-defensins hBD-1 and hBD-2 in intestinal epithelium. J Immunol. (1999) 163:6718–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sotolongo J, Ruiz J, Fukata M. The role of innate immunity in the host defense against intestinal bacterial pathogens. Curr Infect Dis Rep. (2012) 14:15–23. 10.1007/s11908-011-0234-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katakura K, Watanabe H, Ohira H. Innate immunity and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of clinical evidence and future application. Clin J Gastroenterol. (2013) 6:415–9. 10.1007/s12328-013-0436-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thaiss CA, Levy M, Suez J, Elinav E. The interplay between the innate immune system and the microbiota. Curr Opin Immunol. (2014) 26:41–8. 10.1016/j.coi.2013.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, Ruhn KA, Yu X, Koren O, et al. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIgamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science. (2011) 334:255–8. 10.1126/science.1209791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas M, Pierson M, Uprety T, Zhu L, Ran Z, Sreenivasan CC, et al. Comparison of porcine airway and intestinal epithelial cell lines for the susceptibility and expression of pattern recognition receptors upon influenza virus infection. Viruses. (2018) 10:312. 10.3390/v10060312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abreu MT. Toll-like receptor signalling in the intestinal epithelium: how bacterial recognition shapes intestinal function. Nat Rev Immunol. (2010) 10:131–44. 10.1038/nri2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gallo RL, Hooper LV. Epithelial antimicrobial defence of the skin and intestine. Nat Rev Immunol. (2012) 12:503–16. 10.1038/nri3228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mukherjee S, Hooper LV. Antimicrobial defense of the intestine. Immunity. (2015) 42:28–39. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dessein R, Gironella M, Vignal C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sokol H, Secher T, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 is critical for induction of Reg3 beta expression and intestinal clearance of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Gut. (2009) 58:771–6. 10.1136/gut.2008.168443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burger-van Paassen N, Loonen LM, Witte-Bouma J, Korteland-van Male AM, de Bruijn AC, van der Sluis M, et al. Mucin Muc2 deficiency and weaning influences the expression of the innate defense genes Reg3beta, Reg3gamma and angiogenin-4. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e38798. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bel S, Pendse M, Wang Y, Li Y, Ruhn KA, Hassell B, et al. Paneth cells secrete lysozyme via secretory autophagy during bacterial infection of the intestine. Science. (2017) 357:1047–52. 10.1126/science.aal4677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valentini M, Piermattei A, Di Sante G, Migliara G, Delogu G, Ria F. Immunomodulation by gut microbiota: role of Toll-like receptor expressed by T cells. J Immunol Res. (2014) 2014:586939. 10.1155/2014/586939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Earle KA, Billings G, Sigal M, Lichtman JS, Hansson GC, Elias JE, et al. Quantitative imaging of gut microbiota spatial organization. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 18:478–88. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larsson E, Tremaroli V, Lee YS, Koren O, Nookaew I, Fricker A, et al. Analysis of gut microbial regulation of host gene expression along the length of the gut and regulation of gut microbial ecology through MyD88. Gut. (2012) 61:1124–31. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ju T, Shoblak Y, Gao Y, Yang K, Fouhse J, Finlay BB, et al. Initial gut microbial composition as a key factor driving host response to antibiotic treatment, as exemplified by the presence or absence of commensal Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2017) 83:e01107–17. 10.1128/AEM.01107-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iliev ID, Funari VA, Taylor KD, Nguyen Q, Reyes CN, Strom SP, et al. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science. (2012) 336:1314–7. 10.1126/science.1221789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eriksson M, Johannssen T, von Smolinski D, Gruber AD, Seeberger PH, Lepenies B. The C-type lectin receptor SIGNR3 binds to fungi present in commensal microbiota and influences immune regulation in experimental colitis. Front Immunol. (2013) 4:196. 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G. The inflammasome: a caspase-1-activation platform that regulates immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Nat Immunol. (2009) 10:241–7. 10.1038/ni.1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lopez-Castejon G, Brough D. Understanding the mechanism of IL-1beta secretion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2011) 22:189–95. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sahoo M, Ceballos-Olvera I, del Barrio L, Re F. Role of the inflammasome, IL-1beta, and IL-18 in bacterial infections. ScientificWorldJournal. (2011) 11:2037–50. 10.1100/2011/212680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmidt RL, Lenz LL. Distinct licensing of IL-18 and IL-1beta secretion in response to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e45186. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanneganti TD. The inflammasome: firing up innate immunity. Immunol Rev. (2015) 265:1–5. 10.1111/imr.12297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.He Y, Hara H, Nunez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem Sci. (2016) 41:1012–21. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crowley SM, Vallance BA, Knodler LA. Noncanonical inflammasomes: antimicrobial defense that does not play by the rules. Cell Microbiol. (2017) 19 10.1111/cmi.12730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Knodler LA, Crowley SM, Sham HP, Yang H, Wrande M, Ma C, et al. Noncanonical inflammasome activation of caspase-4/caspase-11 mediates epithelial defenses against enteric bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. (2014) 16:249–56. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thinwa J, Segovia JA, Bose S, Dube PH. Integrin-mediated first signal for inflammasome activation in intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. (2014) 193:1373–82. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harrison OJ, Srinivasan N, Pott J, Schiering C, Krausgruber T, Ilott NE, et al. Epithelial-derived IL-18 regulates Th17 cell differentiation and Foxp3(+) Treg cell function in the intestine. Mucosal Immunol. (2015) 8:1226–36. 10.1038/mi.2015.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rauch I, Deets KA, Ji DX, von Moltke J, Tenthorey JL, Lee AY, et al. NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasomes coordinate intestinal epithelial cell expulsion with eicosanoid and IL-18 release via activation of caspase-1 and−8. Immunity. (2017) 46:649–59. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity. (2009) 30:556–65. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Franchi L, Kamada N, Nakamura Y, Burberry A, Kuffa P, Suzuki S, et al. NLRC4-driven production of IL-1beta discriminates between pathogenic and commensal bacteria and promotes host intestinal defense. Nat Immunol. (2012) 13:449–56. 10.1038/ni.2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nordlander S, Pott J, Maloy KJ. NLRC4 expression in intestinal epithelial cells mediates protection against an enteric pathogen. Mucosal Immunol. (2014) 7:775–85. 10.1038/mi.2013.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Levy M, Thaiss CA, Katz MN, Suez J, Elinav E. Inflammasomes and the microbiota–partners in the preservation of mucosal homeostasis. Semin Immunopathol. (2015) 37:39–46. 10.1007/s00281-014-0451-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Endimiani A, Luzzaro F, Brigante G, Perilli M, Lombardi G, Amicosante G, et al. Proteus mirabilis bloodstream infections: risk factors and treatment outcome related to the expression of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2005) 49:2598–605. 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2598-2605.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hardt WD. Journal club. An infection biologist points out an outstanding issue in mucosal immunology. Nature. (2009) 459:893. 10.1038/459893e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seo SU, Kamada N, Munoz-Planillo R, Kim YG, Kim D, Koizumi Y, et al. Distinct commensals induce interleukin-1beta via NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory monocytes to promote intestinal inflammation in response to injury. Immunity. (2015) 42:744–55. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ignacio A, Morales CI, Camara NO, Almeida RR. Innate sensing of the gut microbiota: modulation of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:54. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen KW, Gross CJ, Sotomayor FV, Stacey KJ, Tschopp J, Sweet MJ, et al. The neutrophil NLRC4 inflammasome selectively promotes IL-1beta maturation without pyroptosis during acute Salmonella challenge. Cell Rep. (2014) 8:570–82. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Karki R, Lee E, Place D, Samir P, Mavuluri J, Sharma BR, et al. IRF8 regulates transcription of naips for NLRC4 inflammasome activation. Cell. (2018) 173:920–33.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chi W, Li F, Chen H, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Yang X, et al. Caspase-8 promotes NLRP1/NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1beta production in acute glaucoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:11181–6. 10.1073/pnas.1402819111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaushal V, Dye R, Pakavathkumar P, Foveau B, Flores J, Hyman B, et al. Neuronal NLRP1 inflammasome activation of Caspase-1 coordinately regulates inflammatory interleukin-1-beta production and axonal degeneration-associated Caspase-6 activation. Cell Death Differ. (2015) 22:1676–86. 10.1038/cdd.2015.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen GY, Liu M, Wang F, Bertin J, Nunez G. A functional role for Nlrp6 in intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Immunol. (2011) 186:7187–94. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levy M, Thaiss CA, Zeevi D, Dohnalova L, Zilberman-Schapira G, Mahdi JA, et al. Microbiota-modulated metabolites shape the intestinal microenvironment by regulating NLRP6 inflammasome signaling. Cell. (2015) 163:1428–43. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Micaroni M, Stanley AC, Khromykh T, Venturato J, Wong CX, Lim JP, et al. Rab6a/a′ are important Golgi regulators of pro-inflammatory TNF secretion in macrophages. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e57034. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brough D, Rothwell NJ. Caspase-1-dependent processing of pro-interleukin-1beta is cytosolic and precedes cell death. J Cell Sci. (2007) 120(Pt 5):772–81. 10.1242/jcs.03377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pallett MA, Crepin VF, Serafini N, Habibzay M, Kotik O, Sanchez-Garrido J, et al. Bacterial virulence factor inhibits caspase-4/11 activation in intestinal epithelial cells. Mucosal Immunol. (2017) 10:602–12. 10.1038/mi.2016.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guo H, Callaway JB, Ting JP. Inflammasomes: mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat Med. (2015) 21:677–87. 10.1038/nm.3893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thi HTH, Hong S. Inflammasome as a therapeutic target for cancer prevention and treatment. J Cancer Prev. (2017) 22:62–73. 10.15430/JCP.2017.22.2.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maes M, Kubera M, Leunis JC. The gut-brain barrier in major depression: intestinal mucosal dysfunction with an increased translocation of LPS from gram negative enterobacteria (leaky gut) plays a role in the inflammatory pathophysiology of depression. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. (2008) 29:117–24. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Roselletti E, Perito S, Gabrielli E, Mencacci A, Pericolini E, Sabbatini S, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome is a key player in human vulvovaginal disease caused by Candida albicans. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:17877. 10.1038/s41598-017-17649-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Joly S, Ma N, Sadler JJ, Soll DR, Cassel SL, Sutterwala FS. Cutting edge: Candida albicans hyphae formation triggers activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol. (2009) 183:3578–81. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gombault A, Baron L, Couillin I. ATP release and purinergic signaling in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front Immunol. (2012) 3:414. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Amores-Iniesta J, Barbera-Cremades M, Martinez CM, Pons JA, Revilla-Nuin B, Martinez-Alarcon L, et al. Extracellular ATP activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and is an early danger signal of skin allograft rejection. Cell Rep. (2017) 21:3414–26. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Dubyak GR, Nunez G. Differential requirement of P2X7 receptor and intracellular K+ for caspase-1 activation induced by intracellular and extracellular bacteria. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:18810–8. 10.1074/jbc.M610762200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dubyak GR. P2X7 receptor regulation of non-classical secretion from immune effector cells. Cell Microbiol. (2012) 14:1697–706. 10.1111/cmi.12001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Franceschini A, Capece M, Chiozzi P, Falzoni S, Sanz JM, Sarti AC, et al. The P2X7 receptor directly interacts with the NLRP3 inflammasome scaffold protein. FASEB J. (2015) 29:2450–61. 10.1096/fj.14-268714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. (2013) 54:2325–40. 10.1194/jlr.R036012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Grebe A, Hoss F, Latz E. NLRP3 inflammasome and the IL-1 pathway in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. (2018) 122:1722–40. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Munoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martinez-Colon G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Nunez G. K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. (2013) 38:1142–53. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mabuchi T, Takekoshi T, Hwang ST. Epidermal CCR6+ gammadelta T cells are major producers of IL-22 and IL-17 in a murine model of psoriasiform dermatitis. J Immunol. (2011) 187:5026–31. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Malhotra N, Yoon J, Leyva-Castillo JM, Galand C, Archer N, Miller LS, et al. IL-22 derived from gammadelta T cells restricts Staphylococcus aureus infection of mechanically injured skin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2016) 138:1098–107.e93. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Steinbach S, Vordermeier HM, Jones GJ. CD4+ and gammadelta T cells are the main producers of IL-22 and IL-17A in lymphocytes from Mycobacterium bovis-infected cattle. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:29990. 10.1038/srep29990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tyler CJ, McCarthy NE, Lindsay JO, Stagg AJ, Moser B, Eberl M. Antigen-presenting human gammadelta T cells promote intestinal CD4(+) T cell expression of IL-22 and mucosal release of calprotectin. J Immunol. (2017) 198:3417–25. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Xu X, Weiss ID, Zhang HH, Singh SP, Wynn TA, Wilson MS, et al. Conventional NK cells can produce IL-22 and promote host defense in Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia. J Immunol. (2014) 192:1778–86. 10.4049/jimmunol.1300039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zheng Y, Valdez PA, Danilenko DM, Hu Y, Sa SM, Gong Q, et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. (2008) 14:282–9. 10.1038/nm1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ota N, Wong K, Valdez PA, Zheng Y, Crellin NK, Diehl L, et al. IL-22 bridges the lymphotoxin pathway with the maintenance of colonic lymphoid structures during infection with Citrobacter rodentium. Nat Immunol. (2011) 12:941–8. 10.1038/ni.2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kinnebrew MA, Ubeda C, Zenewicz LA, Smith N, Flavell RA, Pamer EG. Bacterial flagellin stimulates Toll-like receptor 5-dependent defense against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infection. J Infect Dis. (2010) 201:534–43. 10.1086/650203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Abt MC, Buffie CG, Susac B, Becattini S, Carter RA, Leiner I, et al. TLR-7 activation enhances IL-22-mediated colonization resistance against vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Sci Transl Med. (2016) 8:327ra325. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad6663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sellau J, Alvarado CF, Hoenow S, Mackroth MS, Kleinschmidt D, Huber S, et al. IL-22 dampens the T cell response in experimental malaria. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:28058. 10.1038/srep28058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Behnsen J, Jellbauer S, Wong CP, Edwards RA, George MD, Ouyang W, et al. The cytokine IL-22 promotes pathogen colonization by suppressing related commensal bacteria. Immunity. (2014) 40:262–73. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stelter C, Kappeli R, Konig C, Krah A, Hardt WD, Stecher B, et al. Salmonella-induced mucosal lectin RegIIIbeta kills competing gut microbiota. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e20749. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hayden JA, Brophy MB, Cunden LS, Nolan EM. High-affinity manganese coordination by human calprotectin is calcium-dependent and requires the histidine-rich site formed at the dimer interface. J Am Chem Soc. (2013) 135:775–87. 10.1021/ja3096416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Feinen B, Russell MW. Contrasting roles of IL-22 and IL-17 in murine genital tract infection by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front Immunol. (2012) 3:11. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Quintana FJ. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: a molecular pathway for the environmental control of the immune response. Immunology. (2013) 138:183–9. 10.1111/imm.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Murray IA, Perdew GH. Ligand activation of the Ah receptor contributes to gastrointestinal homeostasis. Curr Opin Toxicol. (2017) 2:15–23. 10.1016/j.cotox.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gao J, Xu K, Liu H, Liu G, Bai M, Peng C, et al. Impact of the gut microbiota on intestinal immunity mediated by tryptophan metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2018) 8:13. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Million M, Tomas J, Wagner C, Lelouard H, Raoult D, Gorvel J-P. New insights in gut microbiota and mucosal immunity of the small intestine. Hum Microbiome J. (2018) 7–8:23–32. 10.1016/j.humic.2018.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yitbarek A, Taha-Abdelaziz K, Hodgins DC, Read L, Nagy E, Weese JS, et al. Gut microbiota-mediated protection against influenza virus subtype H9N2 in chickens is associated with modulation of the innate responses. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:13189 10.1038/s41598-018-31613-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Natividad JM, Agus A, Planchais J, Lamas B, Jarry AC, Martin R, et al. Impaired aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand production by the gut microbiota is a key factor in metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. (2018) 28:737–49.e4. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, De Luca A, Giovannini G, Pieraccini G, et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity. (2013) 39:372–85. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Valeri M, Raffatellu M. Cytokines IL-17 and IL-22 in the host response to infection. Pathog Dis. (2016) 74:ftw111. 10.1093/femspd/ftw111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Krishnan S, Ding Y, Saedi N, Choi M, Sridharan GV, Sherr DH, et al. Gut microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites modulate inflammatory response in hepatocytes and macrophages. Cell Rep. (2018) 23:1099–111. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ismail AS, Severson KM, Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Yu X, Benjamin JL, et al. Gammadelta intraepithelial lymphocytes are essential mediators of host-microbial homeostasis at the intestinal mucosal surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:8743–8. 10.1073/pnas.1019574108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Witter AR, Okunnu BM, Berg RE. The essential role of neutrophils during infection with the intracellular bacterial pathogen listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. (2016) 197:1557–65. 10.4049/jimmunol.1600599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, Havran WL. gammadelta T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17:733–45. 10.1038/nri.2017.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Krishnan S, Prise IE, Wemyss K, Schenck LP, Bridgeman HM, McClure FA, et al. Amphiregulin-producing gammadelta T cells are vital for safeguarding oral barrier immune homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:10738–43. 10.1073/pnas.1802320115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Heiss CN, Olofsson LE. The role of the gut microbiota in development, function and disorders of the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system. J Neuroendocrinol. (2019) e12684. 10.1111/jne.12684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. (2005) 122:107–18. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. (2008) 180:5771–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Cyktor JC, Turner J. Interleukin-10 and immunity against prokaryotic and eukaryotic intracellular pathogens. Infect Immun. (2011) 79:2964–73. 10.1128/IAI.00047-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Iyer SS, Cheng G. Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit Rev Immunol. (2012) 32:23–63. 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i1.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ueda Y, Kayama H, Jeon SG, Kusu T, Isaka Y, Rakugi H, et al. Commensal microbiota induce LPS hyporesponsiveness in colonic macrophages via the production of IL-10. Int Immunol. (2010) 22:953–62. 10.1093/intimm/dxq449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Rivollier A, He J, Kole A, Valatas V, Kelsall BL. Inflammation switches the differentiation program of Ly6Chi monocytes from antiinflammatory macrophages to inflammatory dendritic cells in the colon. J Exp Med. (2012) 209:139–55. 10.1084/jem.20101387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hayashi A, Sato T, Kamada N, Mikami Y, Matsuoka K, Hisamatsu T, et al. A single strain of Clostridium butyricum induces intestinal IL-10-producing macrophages to suppress acute experimental colitis in mice. Cell Host Microbe. (2013) 13:711–22. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ochi T, Feng Y, Kitamoto S, Nagao-Kitamoto H, Kuffa P, Atarashi K, et al. Diet-dependent, microbiota-independent regulation of IL-10-producing lamina propria macrophages in the small intestine. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:27634. 10.1038/srep27634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Quiros M, Nishio H, Neumann PA, Siuda D, Brazil JC, Azcutia V, et al. Macrophage-derived IL-10 mediates mucosal repair by epithelial WISP-1 signaling. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:3510–20. 10.1172/JCI90229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Sassone-Corsi M, Raffatellu M. No vacancy: how beneficial microbes cooperate with immunity to provide colonization resistance to pathogens. J Immunol. (2015) 194:4081–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.1403169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Crouzet L, Derrien M, Cherbuy C, Plancade S, Foulon M, Chalin B, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei CNCM I-3689 reduces vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus persistence and promotes Bacteroidetes resilience in the gut following antibiotic challenge. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:5098. 10.1038/s41598-018-23437-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]