Abstract

Hybrid E. coli pathotypes are representing emerging public health threats with enhanced virulence from different pathotypes. Hybrids of Shiga toxin-producing and enterotoxigenic E. coli (STEC/ETEC) have been reported to be associated with diarrheal disease and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) in humans. Here, we identified and characterized four clinical STEC/ETEC hybrids from diarrheal patients with or without fever or abdominal pain and healthy contact in Sweden. Rare stx2 subtypes were present in STEC/ETEC hybrids. Stx2 production was detectable in stx2a and stx2e containing strains. Different copies of ETEC virulence marker, sta gene, were found in two hybrids. Three sta subtypes, namely, sta1, sta4 and sta5 were designated, with sta4 being predominant. The hybrids represented diverse and rare serotypes (O15:H16, O187:H28, O100:H30, and O136:H12). Genome-wide phylogeny revealed that these hybrids exhibited close relatedness with certain ETEC, STEC/ETEC hybrid and commensal E. coli strains, implying the potential acquisition of Stx-phages or/and ETEC virulence genes in the emergence of STEC/ETEC hybrids. Given the emergence and public health significance of hybrid pathotypes, a broader range of virulence markers should be considered in the E. coli pathotypes diagnostics, and targeted follow up of cases is suggested to better understand the hybrid infection.

Introduction

Escherichia coli strains isolated from intestinal diseases have been grouped into at least six main pathotypes on the basis of epidemiological evidence, phenotypic traits, clinical features, and specific virulence factors1. The well-described intestinal pathotypes of diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) are Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC). The virulence-associated genes that are unique to a pathotype have been used as molecular markers to define the pathotype of E. coli strains.

STEC, defined by the production of phage-encoded Shiga toxins (Stxs), poses a significant public health concern as it can cause a wide spectrum of symptoms ranging from asymptomatic carriage to severe diarrhea, as well as bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS)1. Stxs are classified into two major families, Stx1 and Stx2 (encoded by stx1 and stx2) on the basis of toxin neutralization assays and sequence analysis2. The Stx1/Stx2 have been further classified into three Stx1 subtypes (Stx1a, Stx1c, and Stx1d) and seven Stx2 subtypes (Stx2a to 2 g) in E. coli strains based on sequences similarities and phylogenetic analysis2. Stx subtypes display dramatic differences in disease causing potency3. Stx2a (with or without Stx2c) and Stx2d are regarded to be more potent than other subtypes and highly associated with HUS4. However, the clinical significance of other Stx subtypes as well as the interplay of other multiple virulence-associated factors has been noted5,6. Notably, a novel Stx2 subtype, named Stx2h was identified from wild marmots recently, which exhibited a hybrid virulence genes spectrum and pathogenic potential7. ETEC, which is defined by the presence of the plasmid-encoded heat-labile (LT) and/or heat-stable toxins (ST)8, has been identified as a major cause of significant diarrheal illness worldwide9,10. The two classes of ST, STa (encoded by sta) and STb (encoded by stb), differ in sequences and mechanism of action8. STa is associated with human disease, while STb is typically associated with infection in pigs, although stb has been found in human ETEC isolates8.

Many virulence markers for a pathotype are often carried on mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as phage, plasmid as mentioned in STEC and ETEC, thus allowing acquisition of virulence genes via MGEs and horizontal gene transfer leading to the emergence of hybrid pathotypes. Certain Stx-phages can infect and lysogenize almost all known E. coli pathotypes, including both DEC and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC)11. The hybrid STEC pathogens are causing infections and outbreaks in many countries, with the most notorious hybrid being the STEC/EAEC strain O104:H4, which caused a large outbreak with numerous HUS cases and deaths in Germany in 201112. Other STEC hybrid types, for instance, STEC/ExPEC O80:H2 hybrid has been reported to cause HUS and bacteremia13, STEC/UPEC hybrids have been identified from hospitalized patients14,15. Hybrid types like EPEC/EAEC and ETEC/EPEC have also been reported from patients16,17. STEC/ETEC hybrids have been recovered from various sources including humans, animals, food, and water18–21, and some STEC/ETEC strains have been associated with diarrheal disease and HUS in humans22,23.

In Sweden, the prevalence of STEC in hospitalized patients with diarrhea is around 1.2%-1.8% according to previous studies24,25. But little data is available concerning the presence of emerging hybrid pathotypes and its correlation with illness. Here, we present the identification and characterization of STEC/ETEC hybrid strains from Swedish diarrheal patients with or without fever or abdominal pain and healthy contact. The molecular properties of these strains were investigated by initial microarray analysis followed by whole genome sequencing (WGS). The phylogenomic analysis was used to assess the phylogenetic position of these hybrids among a diverse collection of E. coli and Shigella spp. representing all major pathotypes. Based on these results, we discuss the potential public health importance of these hybrid E. coli strains.

Results

STEC/ETEC hybrids in Diarrheal Patients and Clinical Features

Four out of 195 clinical STEC isolates (2.05%) over a 15 years-period investigation in Region Jönköping County, Sweden, were found to carry both stx2 and sta, designated as STEC/ETEC hybrid pathotype. The four hybrids were isolated from individuals infected in local cities in Sweden where they were living. Three hybrids were from diarrheal patients, among which one had abdominal pain and fever simultaneously. One strain was from an individual sampled by contact tracing, and without any clinical symptoms included in this study. The duration of stx shedding was available in three patients, which ranged from 11 to 65 days. The four STEC/ETEC hybrids and associated clinical features are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of STEC/ETEC hybrid strains in this study.

| Strain | Serotype | stx subtype | sta subtype | ST | Sampling year | Clinical symptom | Duration of stx shedding (day) | Age of patients (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE572 | O187:H28 | stx2g | sta4, sta5 | 200 | 2005 | D | 11 | 1 |

| SE573 | O15:H16 | stx2g | sta4 | 325 | 2009 | D, AP, F | 16 | 56 |

| SE574 | O136:H12 | stx2a | sta4, sta4, sta5 | 329 | 2014 | N | 18 | 10 |

| SE575 | O100:H30 | stx2e | sta1 | 993 | 2017 | D | — | 82 |

D: Diarrhea. AP: Abdominal pain. F: Fever. N: No symptoms, individual was sampled due to contact tracing around an index case. -: Unavailable.

Genome Assemblies of STEC/ETEC Hybrids

All four STEC/ETEC genomes remained as draft genomes comprising of 244, 393, 552, 350 contigs, respectively. The chromosome sizes, coding DNA sequences (CDSs), rRNA and tRNA found in these hybrids are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genome features of STEC/ETEC hybrid strains in this study.

| SE572 | SE573 | SE574 | SE575 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage | 46 | 79 | 82 | 31 |

| No. contigs | 244 | 393 | 552 | 350 |

| Total length (bp) | 5 266 892 | 5 380 960 | 5 520 089 | 5 012 207 |

| G + C ratio (%) | 51% | 50% | 50% | 51% |

| No. CDS | 5 088 | 5 149 | 5 297 | 4 755 |

| No. rRNA | 8 | 11 | 10 | 9 |

| No. tRNA | 83 | 95 | 98 | 72 |

| No. Prophages | 11 | 12 | 12 | 9 |

| Accession number | SAMN09758572 | SAMN09758573 | SAMN09758574 | SAMN09758575 |

Serotypes, stx Subtypes, Virulence Genes and Sequence Types

Four serotypes, i.e., O187:H28, O15:H16, O136:H12 and O100:H30 were assigned. The four hybrids carried stx2 genes, which were assigned with three stx2 subtypes: two strains from diarrheal patients carried stx2g, one from a diarrheal patient harbored stx2e. Strain SE574 without any investigated-symptoms which was sampled from contact tracing possessed stx2a (Table 1). Except stx2 and sta genes, other virulence factors were identified in these hybrids which mainly belonged to three categories: toxin, adherence factor and serum resistance (Table 3). The four hybrids belong to different MLST sequence types (ST200, ST325, ST329 and ST993) (Table 1). Serotypes, stx subtypes, virulence genes determined by whole genome sequences analysis matched the initial microarray analysis.

Table 3.

Presence of virulence genes carried on four STEC/ETEC hybrids.

| Category | Gene | Product/Function | SE572 | SE573 | SE574 | SE575 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxin | stx2 | Shiga toxin 2 | + | + | + | + |

| sta | Heat-stable enterotoxin STa | + | + | + | + | |

| astA | EAEC heat-stable enterotoxin I | + | + | + | − | |

| cba | Colicin B | − | + | + | − | |

| cma | Colicin M | − | + | + | − | |

| ehxA | EHEC hemolysin | + | − | + | − | |

| Adherence | lpfA | Long polar fimbriae | + | + | + | − |

| Serum resistance | iss | Increased serum survival | − | + | + | + |

Heat-stable Enterotoxin Phylogeny

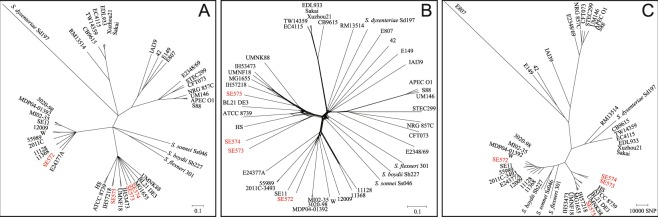

Strain SE574 carried three distinct copies of sta gene, among which two copies exhibited high nucleotide identity (99.1%), while shared only 88.2% identity with the remaining one. SE572 carried two divergent copies of sta with 87.3% nucleotide identity. SE573 and SE575 possessed one copy of sta each. A phylogenetic scheme was further used to assign sta subtypes. The phylogenetic relatedness of 21 reference sta gene sequences assigned in this study were consistent with that reported previously26 (Fig. 1). The seven copies of sta gene carried on four hybrids were assigned as three different sta subtypes (sta1, sta4 and sta5). Strain SE572 and SE574 carried both sta4 and sta5, with two sta4 copies present in SE574. SE573 and SE575 possessed sta1 and sta4, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of sta alleles by the neighbour-joining method. The neighbour-joining tree was inferred from nucleotide sequences of all sta alleles using a p distance matrix. Strain designations and GenBank accession numbers (or WGS prefixes) are given at the branch tips. Bootstrap values based on 1000 replications (>50%) are given at the internal nodes. sta subtypes are given next to the outer brackets. The four STEC/ETEC hybrid strains in this study were highlighted in bold.

Prophage Regions, Stx-converting Phages and Stx production

For strain SE572, 11 prophage regions were identified, of which 7 regions were intact, 2 were incomplete, and 2 were questionable. Stx2g was identified in an intact phage region, where Stx phage-specific genes encoding the integrase, transcriptional regulator, antirepressor, antitermination protein Q and lysis were present. For strain SE573, 12 prophage regions were identified, of which 7 regions were intact, 4 were incomplete and 1 was questionable. Nevertheless, Stx2-converting phage on SE573 remained unidentified as no Shiga toxin gene was found by using PHAST tool. For strain SE574, 12 prophage regions were identified, of which 6 were intact, and 6 were incomplete. Stx2a was found on an incomplete phage region, where Stx phage-specific genes encoding antirepressor and antitermination protein Q were present. For SE575, 9 prophage regions were identified, of which 5 were intact, and 4 were incomplete. Stx2e was found on an incomplete phage region, where antitermination protein Q was observed. The Stx-phages insertion sites of these hybrids remained unidentified due to the limitation of draft genomes used. Stx2 production was detectable in one stx2a-containing strain, while undetectable in two stx2g-containing strains by both the Duopath® STEC Rapid Test and Vero cell assay. For the stx2e-containing strain, Stx was detectable by VCA while not by Duopath® STEC Rapid Test.

Plasmid-associated Sequences

PlasmidFinder indicated several plasmid replicon sequences of known Inc groups in four STEC/ETEC genomes (Table 4). Strain SE572, SE573 and SE574 had three, four and five plasmid replicons, respectively. SE575 had two plasmid replicons: IncFII (pHN7A8) and IncI1 (Alpha). Notably, the plasmid-associated gene sta was placed in the same contig as IncFII in strain SE575. In addition, according to genome annotation of SE575, several plasmid-associated genes, such as plasmid segregation protein ParM, plasmid stability protein, IncFII RepA protein family protein, replication regulatory protein RepB were located in the same contig as sta gene. In the plasmid assembly sequences generated with plasmidSPAdes algorithm, one copy of sta gene was identified in each of the plasmid sequences of strain SE572, SE573 and SE574.

Table 4.

Plasmid replicons found in the four STEC/ETEC hybrids.

| Strain | Replicon | Reference Acc. | Coverage (%) | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE572 | IncFIB | AP001918 | 100 | 98 |

| IncFII | AY458016 | 100 | 99 | |

| Col156 | NC_009781 | 100 | 94 | |

| SE573 | IncFIB | AP001918 | 100 | 97 |

| IncI2 (Delta) | AP002527 | 100 | 98 | |

| IncFII (pCoo) | CR942285 | 100 | 96 | |

| Col (MG828) | NC_008486 | 100 | 92 | |

| SE574 | IncFIB | AP001918 | 100 | 97 |

| IncFII (pSE11) | AP009242 | 100 | 92 | |

| IncI1 (Alpha) | AP005147 | 100 | 100 | |

| IncB/O/K/Z | GU256641 | 98 | 95 | |

| Col156 | NC_009781 | 100 | 94 | |

| SE575 | IncFII (pHN7A8) | JN232517 | 100 | 98 |

| IncI1 (Alpha) | AP005147 | 100 | 98 |

Phylogenetic Position of STEC/ETEC Hybrids

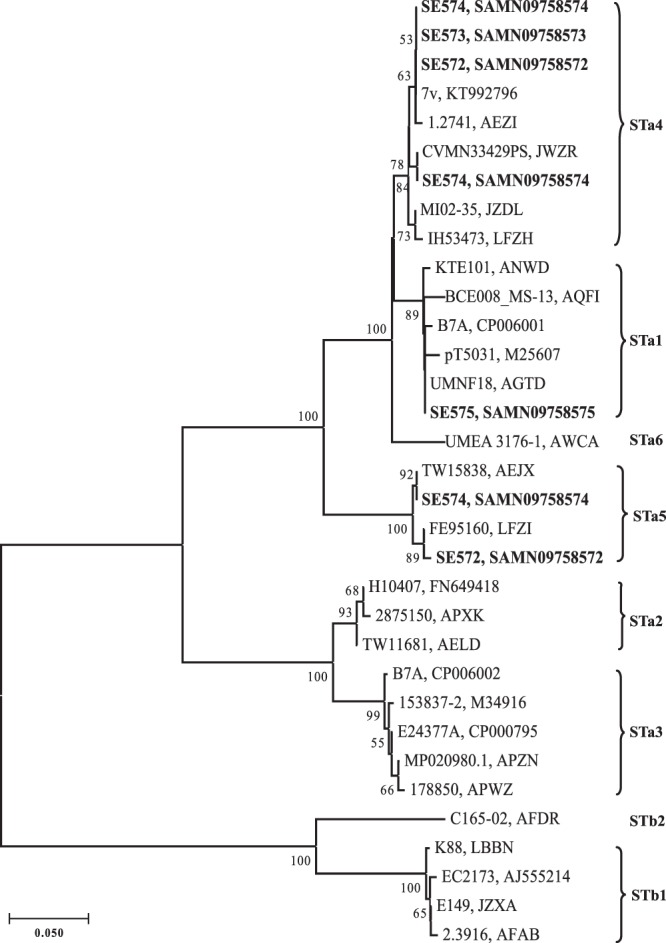

A ClonalFrame tree (Fig. 2A) was inferred from 55 concatenated ribosomal protein gene sequences that are single-copy and shared by 45 strains, which revealed that the four hybrids in this study formed two clusters. Three hybrid strains SE573, SE574 and SE575 were grouped together with previously characterized STEC/ETEC hybrids IH53473 and IH57218 from human, UMNF18 from pig, ETEC strain UMNK88, laboratory-adapted and commensal E. coli strains. Strain SE572 clustered together with strains comprising of ETEC (E24377A), STEC (11128, 11368), EAEC (55989), STEC/ETEC hybrids (3020-98, MDP04-01392 and MI02-35), STEC/EAEC hybrid (2011C-3493), laboratory-adapted and commensal E. coli. Similarly, neighbour-net phylogeny (Fig. 2B) and Gubbins tree (Fig. 2C) generated with concatenated sequences of 2181 shared loci found in wgMLST analysis were also consistent with this finding. Our analysis indicted that despite different E. coli pathotypes are inter-mixed, for example, STEC and ETEC genomes can be found nearly all branches, STEC/ETEC hybrid strains showed more tendency to cluster together.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of STEC/ETEC hybrid strains in this study to other E. coli/Shigella reference strains. The phylogenetic positions of the four hybrid strains in relative to the other 41 reference strains were studied with three different approaches: panel (A) 80% consensus tree generated from three runs of 55 ribosomal protein subunits (rps) gene ClonalFrame analysis; panel (B), Neighbor-Net phylogeny inferred from the allele profiles of the 2181 loci that shared by the 45 isolates; and panel (C) Gubbins tree of the concatenated sequences of the shared loci that found in the wgMLST analysis. The four hybrid isolates were highlighted with red letter.

Discussion

STEC/ETEC hybrids have been identified from animals and humans in Finland22. Here, we report four STEC/ETEC hybrid strains among 195 clinical STEC strains in Sweden over a 15 years-period investigation. The incidence of STEC/ETEC hybrids among clinical STEC collection was 2.05%. In this study, microarray analysis was initially used for molecular characterization of all STEC strains, the results in terms of serotypes, stx genotypes and virulence genes were consistent with the in-depth WGS analysis for these hybrids subsequently. It has been suggested that microarrays, while still faster and cheaper than WGS, might serve as a pre-screening tool to define candidates worth sequencing for better understanding of molecular features associated with pathogenicity and the prospective detection of emerging pathogens27. Currently, hybrid DEC pathotypes remain unrecognized in some local clinical microbiological laboratories where WGS is not routinely performed, and/or where other pathogenic DEC markers and combinations are not looked upon in analysis pipelines due to the surveillance strategies and diagnostics capacities. Our study suggested that more genetic determinates should be included in the STEC or other DEC pathotypes diagnostic, and hybrids pathotypes should be take into account the surveillance and patient care. Furthermore, information obtained in this study contributes significantly to a better understanding of epidemiological and genomics characteristics of hybrid E. coli strains.

Stx2a subtype was reported to be highly associated with severe disease outcomes such as HUS1. In our study, the stx2a-positive strain SE574 was isolated from an individual around an index case, and without any clinical symptoms investigated, indicating the role of other virulence or host-related factors in STEC pathogenesis. Stx2e is closely associated with oedema disease in pigs, and only sporadic in humans with uncomplicated diarrhea or asymptomatic carriers28,29. Nevertheless, Stx2e-producing STEC strains have been isolated from patients with acute diarrhea and HUS30,31, thus the clinical significance of rare human stx subtype shouldn’t be neglected. One hybrid strain carrying stx2e and sta was isolated from an 82-year-old diarrheal patient, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of clinically relevant STEC/ETEC hybrid that harbors stx2e subtype. Stx2g was originally identified in bovine E. coli isolates32, a low prevalence of stx2g was reported in humans33. In our study, two out of four STEC/ETEC hybrids carried stx2g, one was from a 56-year-old diarrheal patient who had fever and abdominal pain simultaneously. Our findings accorded with a German study33, where all of the stx2g-carrying isolates from patients with diarrhea, fever and abdominal pain, were classified as STEC/ETEC hybrid. Notably, our stx2g-carrying strain SE573 from a diarrheal patient with fever and abdominal pain exhibited the same serotype O15:H16 and same sequence type ST325 as the German strains33. STEC/ETEC strains harboring stx2a and stx2e subtypes produced Stx2, while no detectable Stx2 production was observed in the two stx2g-containing strains in this study. Our data accords with a previous report33 that Stx2g was not expressed in some STEC/ETEC hybrid strains. In additional, Garcia-Aljaro et al.34, Beutin et al.35, and Miko et al.36 also reported stx2g-positive strains lacking any Stx expression. Notably, the Stx detection by the two methods used in this study implied the potential false-negative result by the commercial product which might fail to detect some Stx subtypes.

ETEC virulence marker STa (sta), is associated with human disease. Six sta subtypes (sta1-sta6) have been designated, among which sta4 was more frequently found especially in patients with diarrhea and HUS26. In our study, different sta subtypes/combinations were found, three out of four hybrids harbored sta4 subtype, with one carrying two non-identical copies of sta4, indicating that sta4 subtype might be more clinically relevant. Notably, we found one strain carried three different copies of sta gene, one possessed two distinct sta copies. STa are found predominantly on plasmids37. In our study, the sta genes were identified in the plasmid assemblies of strain SE572, SE573 and SE574. In strain SE575, plasmid-related genes, such as incFII family plasmid replication initiator gene repA, surrounded the sta gene. These findings suggested that the sta genes in the four hybrid strains were strongly associated with plasmid and were likely horizontally transferred through plasmid, which was in consistent with the findings in the phylogenetic analysis.

In addition to stx and sta, the four hybrids harbored other virulence genes, some of which have been associated with ETEC, STEC, and EAEC strains. For instance, three strains were positive for astA encoding EAEC heat-stable enterotoxin I, which can be present among strains of STEC, EAEC, EPEC, ETEC, and EIEC pathotypes38 and even ExPEC14. Nevertheless, except the long polar fimbriae gene lpfA, which was present in three strains, none of well-defined adherence-associated genes, such as eae, efa1, iha was identified in our hybrid strains. Moreover, the four hybrids were all negative for ETEC colonization factors, as was the case with STEC/ETEC hybrids reported in Finland39. It is not uncommon that ETEC strains are negative for ETEC colonization factors40, thus other or some novel colonization-associated factors remain to be further explored.

Both the virulence factors and serotypes could be utilized in risk assessment and epidemiological surveillance. The four hybrids belonged to rare serotypes, interestingly, two out of four O groups O15 and O136, but with different H types, have previously been described as STEC/ETEC hybrid strains33. It remains to be further investigated, when more hybrid strains are collected, if some serogroups/serotypes or clones share similar genomic backbone that are more likely to acquire virulence genes, leading to emergence of hybrid pathotypes.

The phylogenetic placement of our clinical STEC/ETEC hybrids demonstrated close relatedness with certain ETEC, STEC/ETEC hybrids, STEC, EAEC, laboratory-adapted and commensal E. coli strains, which was in agreement with previous finding39. It is not surprising that STEC/ETEC hybrids, STEC or ETEC strains scattered in different phylogenetic groups. The dramatic plasticity of the E. coli genome accelerates the adaptation of this species into various environments, which provides numerous opportunities for new variants to emerge via the gains and losses of genes41. The Stx-phages and their ability to transfer genes horizontally play an important role in the evolution of E. coli and development of hybrid pathotypes42. In addition, the plasmids carrying ST/LT toxin genes sta/stb can be transferred between E. coli strains43. Commensal E. coli strains may also evolve to be pathogenic strains as certain parts of their genomes may act as genetic repositories for virulence factors44. Our analysis implied that horizontal transmission of stx2a and/or sta genes by the independent acquisition of the phages and/or plasmids carrying these genes may lead to the emergence of STEC-ETEC hybrids.

It has been indicated that the E. coli genome seems to be formed by an “ancestral” and a “derived” background, each one responsible for the acquisition and expression of different virulence factors45. In this study, we found evidence that STEC/ETEC hybrid strains may have similarities in their genetic background. By combining our data with the previously sequenced STEC/ETEC genomes, we observed that our clinical STEC/ETEC strains clustered with human STEC/ETEC strains O101:H33 IH53473 and O2:H27 IH57218 isolated from HUS and diarrheal patients, respectively in Finland, and both of strains possesses stx2a and sta426. Besides, our strains were phylogenetically close to some animal-derived STEC/ETEC hybrids, such as strain O147:H4 UMNF18, which was recovered from a pig with diarrhea and possessed sta1 and stx2e26. It has been noted that certain genetic background is required for the acquisition and/or maintenance of virulence genes located on MGEs45, and further effort is needed to unveil the structure and characteristic of particular genetic background that are more easily to pick up other genes leading to hybrid pathotypes. No host-specific cluster was observed among hybrid strains in this study, which might partly be due to the limited number of STEC/ETEC genomes available from different sources. Strain SE572 isolated from an infant with diarrhea, formed a separate cluster together with ETEC O139:H28 E24377A, STEC outbreak strain O26:H11 11368 and O103:H2 12009, indicating the genetic diversity of these hybrid strains.

In conclusion, this is the first report of clinical STEC/ETEC hybrids in Sweden. The hybrids exhibit a considerable diversity in terms of virulence genes/genotypes, serotypes and genetic background. Rare stx subtypes and serotypes are found in these hybrids which might be associated with diarrheal disease. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first report of clinically relevant STEC/ETEC hybrid that carry the stx2e subtype. Given the emergence of hybrid pathotypes may lead to serious consequences to public health, a wider range of virulence markers should be included in the E. coli pathotypes diagnostics. Furthermore, hybrid pathogens should be considered in the epidemiological surveillance and patient care.

Materials and Methods

Ethical considerations

All STEC strains and clinical data of STEC patients are collected through routine praxis used for the STEC diagnostics and surveillance performed in Region Jönköping County, Sweden. Formal consent is not required, and no specific ethical permit is needed to characterize the strains.

Clinical Data Collection

Clinical data of STEC infected patients were collected through a questionnaire and by reviewing medical records as part of the routine infection control measures in Region Jönköping County as described previously24. Clinical manifestations included were diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, fever and HUS. STEC-positive patients were sampled weekly until they were negative, and the duration of stx shedding was defined as the time from the first positive sample to the first negative sample.

Isolates Characterization and Determination of STEC/ETEC Hybrid Status

All STEC isolates recovered from stools of diarrheal patients in Region Jönköping County, Sweden from 2003 to 2017 were initially subjected to three different microarrays with the E. coli SeroGenoTyping AS-1 Kit, ShigaToxType AS-2 Kit and E. coli PanType AS-2 Kit, respectively, to determine serotypes, stx allele/subtypes and virulence genes as previously described46. Bacterial DNA was extracted from overnight culture with the EZ1 DNA Tissue Kit on an EZ1 instrument (Qiagen, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Initial serotyping was also performed with O (O1 to O187) and H (H1-H56) antisera by agglutination in micro titer plates using antisera (SSI Diagnostica, Denmark). STEC strains that harbored ST encoding genes sta/stb were designated as STEC/ETEC hybrid pathotype. Production of Shiga toxin was determined by the Duopath® STEC Rapid Test according to the manufacturer’s instructions (https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/mm/104156?lang=en®ion=SE), as well as the Vero cell assay at Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Whole Genome Sequencing and Assembly

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted as described in microarray analysis. Sequencing was performed according to Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) technology on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform at SciLifeLab (Stockholm, Sweden) with 100 bp paired-end reads. The sequencing reads were quality-control processed and quality evaluated with QCtool pipeline (https://github.com/mtruglio/QCtool). The processed reads were assembled de novo with SPAdes (version: 3.12.0) in ‘careful mode’47. The assemblies were annotated with Prokka (version 1.11)48.

Determination of Serotypes, stx subtypes, Virulence genes and MLST Sequence Types

The assemblies were compared to the VirulenceFinder database (DTU, Denmark) (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org/) using BLAST + v2.2.3049 to determine stx genotypes and presence of virulence genes. The cut-off values for gene identity and alignment coverage were set to 90% in the VirulenceFinder database searching. Serotype was determined by comparing assembly sequences to the SerotypeFinder database using BLAST + v2.2.30. MLST was calculated by comparing assembly sequences to the allele reference database using BLAST according to the Warwick E. coli MLST scheme (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/species/ecoli/allele_st_search).

Heat-stable Enterotoxin Phylogeny

The sta gene sequences were extracted from the assembly sequences according to the gene function prediction annotated by Prokka and further verified by comparing with the published sta gene sequences. Twenty-one unique reference sta sequences assigned as six sta subtypes and five unique stb sequences as outgroup were kindly provided by Dr. Susan R. Leonard26. The full nucleotide sequences (~219 bp) of sta gene were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm in the MegAlign module of the Lasergene software package (DNASTAR Inc.). The resulting alignment was imported into MEGA 7.0 for neighbour-joining analysis using a p distance matrix and 1000 bootstrap replications.

Identification of Prophages and Plasmid-Associated Sequences

The prophages in the STEC/ETEC genomes were identified by using PHAST tool (http://phaster.ca/)50. The Stx-converting phage sequences were extracted from predicted prophages and then manually verified and corrected. The gene adjacent to the phage integrase was designated as the phage insertion site18. To detect in silico possible plasmids in genomes, the assemblies were used as query to search against a database of reference plasmid replicon sequences with BLAST49. The reference sequence database was downloaded from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology server (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/data.php). The BLAST search in reference plasmid replicon sequences were reported according to the guidance of the PlasmidFinder database (alignment coverage to the reference sequence > = 66%, and identity percentage >= 85%)51. To extract plasmid sequences from the WGS data, the processed sequence reads were assembled separately with plasmidSPAdes algorithm52 that incorporated into the SPAdes assembler (version: 3.12.0)47 and then annotated with Prokka48.

Phylogenetic Analysis

To generate a high-resolution phylogenomic tree depicting position of STEC/ETEC hybrids, the draft genomes were compared with eight previously reported STEC/ETEC hybrid genomes and 33 representative E. coli/Shigella genomes representing all the major E. coli pathotypes (Supplementary Table S1). The relationships of these isolates were assessed with three different approaches: ribosomal protein subunits (rps) gene sequence analysis, whole-genome multilocus typing (wgMLST) and whole-genome phylogeny analysis. The rps gene sequences have strong clonal signal and are rich in genetic variations thus being ideal target for bacterial phylogenetic relationship characterization53. The complete coding sequences (CDS) of the rps genes shared by the 45 isolates were extracted with fast-GeP. The completed whole-genome sequence of the strain EDL933 (Acc. CP008957.1) was used as reference genome to perform an ad hoc fast-GeP analysis54. The extracted rps gene sequences were analysed independently three times with ClonalFrame (version 1.1) and an 80% consensus tree was converged and merged from the outputs of the three runs55. Ad hoc wgMLST analysis was performed using EDL933 as reference genome by fast-GeP54. A NeighborNet phylogenetic network was calculated from the wgMLST allele profiles and displayed with Splits Tree 456. Whole-genome phylogeny was inferred from concatenated CDSs of the shared loci found and aligned by the fast-GeP pipeline with Gubbins analysis57.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The draft genome sequences of the four STEC/ETEC strains SE572, SE573, SE574 and SE575 were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers given in Table 2.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Susan R. Leonard (Division of Molecular Biology, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Laurel, Maryland, USA) for kindly providing the sta and stb sequences of the reference STEC/ETEC hybrid strains used in this study. We thank Prof. Anders Sönnerborg and Dr. Ujjwal Neogi (Division of Clinical Microbiology, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Karolinska Institute) for their kind bioinformatics support. This work was supported by grants from Futurum, the Academy for Health and Care, Region Jönköping County (FUTURUM-425271), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81701977). J.Z. was funded by the New Zealand Food Safety Science & Research Centre. All funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author Contributions

A.M. and X.B. designed the project. C.J. conducted the whole genome sequencing. J.Z. and A.A. performed WGS analysis. R.E. conducted the microarray analysis. F.S. performed the detection of Shiga toxin production. X.B., A.M. and Y.X. contributed to analysis. X.B. and A.M. wrote the paper. All authors polished the paper.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript and the Supplemental Materials.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-42122-z.

References

- 1.Scheutz, F. Taxonomy Meets Public Health: The Case of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr2, 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0019-2013 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Scheutz F, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing Stx nomenclature. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2951–2963. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00860-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller CA, Pellino CA, Flagler MJ, Strasser JE, Weiss AA. Shiga toxin subtypes display dramatic differences in potency. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1329–1337. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01182-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bielaszewska M, Friedrich AW, Aldick T, Schurk-Bulgrin R, Karch H. Shiga toxin activatable by intestinal mucus in Escherichia coli isolated from humans: predictor for a severe clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1160–1167. doi: 10.1086/508195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karmali, M. A. Host and pathogen determinants of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int Suppl, S4–7, 10.1038/ki.2008.608 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mellmann A, et al. Analysis of collection of hemolytic uremic syndrome-associated enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1287–1290. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai X, et al. Identification and pathogenomic analysis of an Escherichia coli strain producing a novel Shiga toxin 2 subtype. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6756. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25233-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qadri F, Svennerholm AM, Faruque AS, Sack RB. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in developing countries: epidemiology, microbiology, clinical features, treatment, and prevention. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:465–483. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.465-483.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotloff KL, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tozzoli R, et al. Shiga toxin-converting phages and the emergence of new pathogenic Escherichia coli: a world in motion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:80. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasko DA, et al. Origins of the E. coli strain causing an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariani-Kurkdjian P, et al. Haemolytic-uraemic syndrome with bacteraemia caused by a new hybrid Escherichia coli pathotype. New Microbes New Infect. 2014;2:127–131. doi: 10.1002/nmi2.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toval F, et al. Characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from hospital inpatients or outpatients with urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:407–418. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02069-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bielaszewska M, et al. Heteropathogenic virulence and phylogeny reveal phased pathogenic metamorphosis in Escherichia coli O2:H6. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:347–357. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazen TH, et al. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics of Escherichia coli isolates carrying virulence factors of both enteropathogenic and enterotoxigenic E. coli. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3513. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03489-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liebchen A, et al. Characterization of Escherichia coli strains isolated from patients with diarrhea in Sao Paulo, Brazil: identification of intermediate virulence factor profiles by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2274–2278. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00386-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steyert SR, et al. Comparative genomics and stx phage characterization of LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:133. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monday SR, et al. Produce isolates of the Escherichia coli Ont:H52 serotype that carry both Shiga toxin 1 and stable toxin genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3062–3065. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.3062-3065.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beutin L, et al. Evaluation of major types of Shiga toxin 2E-producing Escherichia coli bacteria present in food, pigs, and the environment as potential pathogens for humans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4806–4816. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00623-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lienemann T, et al. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O100:H(-): stx2e in drinking water contaminated by waste water in Finland. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:1239–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9832-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyholm O, et al. Hybrids of Shigatoxigenic and Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC/ETEC) Among Human and Animal Isolates in Finland. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:518–524. doi: 10.1111/zph.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh KH, et al. First Isolation of a Hybrid Shigatoxigenic and Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Strain Harboring the stx2 and elt Genes in Korea. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2017;70:347–348. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2016.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai X, et al. Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Infection in Jonkoping County, Sweden: Occurrence and Molecular Characteristics in Correlation With Clinical Symptoms and Duration of stx Shedding. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:125. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matussek A, Einemo IM, Jogenfors A, Lofdahl S, Lofgren S. Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli in Diarrheal Stool of Swedish Children: Evaluation of Polymerase Chain Reaction Screening and Duration of Shiga Toxin Shedding. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5:147–151. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piv003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonard SR, Mammel MK, Rasko DA, Lacher DW. Hybrid Shiga Toxin-Producing and Enterotoxigenic Escherichia sp. Cryptic Lineage 1 Strain 7v Harbors a Hybrid Plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:4309–4319. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01129-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michael Dunne, W., Jr., Pouseele, H., Monecke, S., Ehricht, R. & van Belkum, A. Epidemiology of transmissible diseases: Array hybridization and next generation sequencing as universal nucleic acid-mediated typing tools. Infect Genet Evol, 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.09.019 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Friedrich AW, et al. Escherichia coli harboring Shiga toxin 2 gene variants: frequency and association with clinical symptoms. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:74–84. doi: 10.1086/338115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonntag AK, et al. Shiga toxin 2e-producing Escherichia coli isolates from humans and pigs differ in their virulence profiles and interactions with intestinal epithelial cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8855–8863. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8855-8863.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saupe A, et al. Acute diarrhoea due to a Shiga toxin 2e-producing Escherichia coli O8: H19. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005099. doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fasel D, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome in a 65-Year-old male linked to a very unusual type of stx2e- and eae-harboring O51:H49 shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1301–1303. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03459-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung PH, et al. A newly discovered verotoxin variant, VT2g, produced by bovine verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7549–7553. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7549-7553.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prager R, Fruth A, Busch U, Tietze E. Comparative analysis of virulence genes, genetic diversity, and phylogeny of Shiga toxin 2g and heat-stable enterotoxin STIa encoding Escherichia coli isolates from humans, animals, and environmental sources. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Aljaro C, Muniesa M, Jofre J, Blanch AR. Newly identified bacteriophages carrying the stx2g Shiga toxin gene isolated from Escherichia coli strains in polluted waters. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258:127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beutin L, et al. Identification of human-pathogenic strains of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from food by a combination of serotyping and molecular typing of Shiga toxin genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4769–4775. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00873-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miko A, et al. Assessment of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from wildlife meat as potential pathogens for humans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6462–6470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00904-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Mentzer A, et al. Identification of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) clades with long-term global distribution. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1321–1326. doi: 10.1038/ng.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paiva de Sousa C, Dubreuil JD. Distribution and expression of the astA gene (EAST1 toxin) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Int J Med Microbiol. 2001;291:15–20. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nyholm O, et al. Comparative Genomics and Characterization of Hybrid Shigatoxigenic and Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC/ETEC) Strains. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Del Canto F, et al. Distribution of classical and nonclassical virulence genes in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolates from Chilean children and tRNA gene screening for putative insertion sites for genomic islands. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3198–3203. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02473-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nogueira T, et al. Horizontal gene transfer of the secretome drives the evolution of bacterial cooperation and virulence. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1683–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt H. Shiga-toxin-converting bacteriophages. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner SM, et al. Phylogenetic comparisons reveal multiple acquisitions of the toxin genes by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains of different evolutionary lineages. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4528–4536. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01474-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasko DA, et al. The pangenome structure of Escherichia coli: comparative genomic analysis of E. coli commensal and pathogenic isolates. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6881–6893. doi: 10.1128/JB.00619-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Escobar-Paramo P, et al. A specific genetic background is required for acquisition and expression of virulence factors in Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1085–1094. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matussek A, et al. Genetic makeup of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in relation to clinical symptoms and duration of shedding: a microarray analysis of isolates from Swedish children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:1433–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2950-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camacho C, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W347–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carattoli A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antipov D, et al. plasmidSPAdes: assembling plasmids from whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3380–3387. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jolley KA, et al. Ribosomal multilocus sequence typing: universal characterization of bacteria from domain to strain. Microbiology. 2012;158:1005–1015. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.055459-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, J., Xiong, Y., Rogers, L., Carter, G. P. & French, N. Genome-by-genome approach for fast bacterial genealogical relationship evaluation. Bioinformatics, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty195 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Didelot X, Falush D. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics. 2007;175:1251–1266. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huson DH. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Croucher NJ, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript and the Supplemental Materials.