Abstract

To assess the effectiveness of an intervention to reduce the calorie content of meals served at two psychiatric rehabilitation programs. Intervention staff assisted kitchen staff with ways to reduce calories and improve the nutritional quality of meals. Breakfast and lunch menus were collected before and after a 6-month intervention period. ESHA software was used to determine total energy and nutrient profiles of meals. Total energy of served meals significantly decreased by 28% at breakfast and 29% at lunch for site 1 (P<0.05); total energy significantly decreased by 41% at breakfast for site 2 (P = 0.018). Total sugars significantly decreased at breakfast for both sites (P ≤ 0.001). In general, sodium levels were high before and after the intervention period. The nutrition intervention was effective in decreasing the total energy and altering the composition of macro-nutrients of meals. These results highlight an unappreciated opportunity to improve diet quality in patients attending psychiatric rehabilitation programs.

Keywords: Nutrition, Obesity, Severe mental illness, Psychiatric rehabilitation programs, Food service

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity has increased substantially over the past several decades with 34% of U.S. adults being obese. In addition, obesity increases the risk for many chronic conditions including cardiovascular disease (Calle et al. 2003; Kenchaiah et al. 2002; Mokdad et al. 2001; Yanovski 2000). Although the development of obesity is complex, a reduced calorie intake is viewed as critical to weight control interventions. Nevertheless, few U.S. adults meet the scientific dietary recommendations or follow repeated guidance from authoritative agencies to limit total calories for maintaining energy balance (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2001, 2004).

Persons with serious mental illness (SMI) have a higher prevalence of obesity than the general population (Allison et al. 1999a). To add to the complexity of the development of obesity in this population, antipsychotic medications have been associated with weight gain (Allison et al. 1999b; Sachs and Guille 1999). Many persons with SMI attend psychiatric rehabilitation day programs (PRPs) where they receive on-site meals, thus, the majority persons with SMI obtain a large proportion of their daily calories from institutional meals, which can be high in calories and low in nutrient density. Reducing the caloric content of institutional meals may help facilitate weight loss and maintenance and, at the same time, increase the intake of nutrient-dense foods including fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Few studies have documented site nutritional interventions in institutional settings (Gillis et al. 2009) and, to our knowledge, no interventions have been implemented in this vulnerable population with chronic mental illness.

The objective of this study was to implement and assess the effectiveness of an environmental nutrition intervention with the kitchen staff to reduce the calorie content of meals while improving nutritional quality.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a pre- post-study to assess the caloric content and overall quality of meals served at two PRPs. This environmental intervention was part of a pilot behavioral weight loss intervention for persons with SMI (Daumit et al.). Both sites were part of the same behavioral health organization. The principal investigator approached the organization’s CEO who expressed interest in the project. Each PRP was managed by their own site manager. One PRP was located in an urban area and the other site in a suburban area. The urban site had a dedicated kitchen staff person and staff and management generally were willing to make changes to the menus. The kitchen staff at the suburban site were also responsible for transporting participants to and from the site, which made cooking from scratch less desirable because of time constraints; there was also less support from the manager to make nutritional changes. The PRPs were open three days per week and served breakfast and lunch. At both sites, kitchen staff with no formal nutrition training prepared meals in commercial kitchens. In order to obtain federal reimbursement, meals conformed to the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) regulations (Maryland State Department of Education 2003).

Environmental Nutrition Intervention

Several procedures were completed before the intervention was delivered. First, intervention staff met with the rehabilitation program directors to introduce the intervention. At this meeting, interventionists communicated the importance and need to reduce calories and improve the nutritional quality of meals served to this vulnerable population. Second, daily menus were collected and observations were made on preparation methods in the kitchen, portion sizes served and consumer behaviors. Both sites operated under the Federal food guidelines; the guidelines were reviewed by the intervention staff before the first consultation.

The purpose of the consultation meetings was to assist kitchen staff with making changes to the menus. Over the course of the 6 month intervention, a total of 2–4 meetings were arranged and at least one registered dietitian was present each meeting. Consultations were held at the PRP and were roughly 1 h in length.

At the first consultation meeting, interventionists reviewed with the kitchen staff the healthy eating topics that were being targeted in the weight loss trial. The environmental nutrition intervention was designed to parallel the concepts emphasized in the group weight management classes that were attended by study participants. Some of the concepts included in the 16 group sessions were energy balance, avoiding sugar-sweetened beverages, increasing fruits and vegetables, healthy eating choices (e.g., choosing baked vs. fried chicken), healthy snacking, grocery shopping and cooking methods. Next, interventionists reviewed food ordering lists and vendor product books with the kitchen staff to become familiar with previous purchases and budget constraints. Intervention staff then offered assistance and suggestions for improving meal offerings, food preparation methods and serving procedures that would effectively reduce total calories; emphasis was placed on decreasing portion sizes. After discussing where dietary improvements could be made and the feasibility of such improvements, kitchen staff were asked to document specific goals that would result in a reduction of calories in the meals served. Examples include switching from 2 to 1% milk, pre-portioning condiments and removing large containers of sugar in the dining room.

The objective of the remaining consultations was to assess progress made towards achieving the initial goals and to keep the staff engaged in the intervention. Furthermore, these additional meetings provided the opportunity to offer further guidance, problem-solve, address barriers and set new goals to improve menu offerings.

Nutrient Analysis of Meals

Six breakfast and six lunch menus were obtained from the kitchen staff at baseline and after the 6 month intervention period. ESHA was used to estimate total energy and nutrients in each meal. Portion sizes and preparation methods were determined by observation and by self-report from the kitchen staff. Specific brands of foods were obtained for most menu items. The nutrient profiles were averaged by meal at each time point and unpaired t tests were used for significance testing. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Urban Site

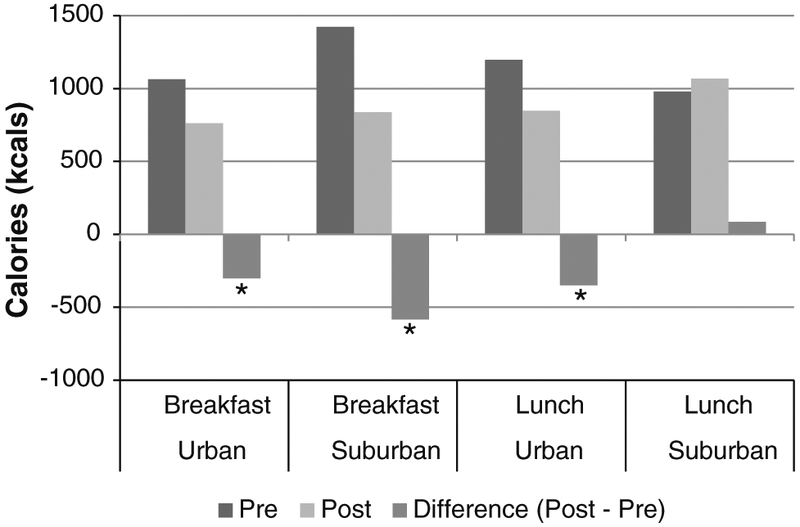

Total energy decreased by 28% (303 kcals) at breakfast and 29% (350 kcals) at lunch by the end of the intervention period for site 1 (P<0.05) (Table 1, Fig. 1). The amount of saturated fat was significantly reduced at breakfast by 3 g (11 g vs. 8 g, P = 0.015). The total amount of carbohydrates decreased by 70 g for both breakfast and lunch meals (P<0.002); total sugars were significantly reduced from 127 to 73 g at breakfast and from 90 to 38 g at lunch (P<0.001). Dietary fiber was low both pre- and post-intervention. Based on recommendations to consume 14 g of fiber per 1,000 kcals, total fiber intake for breakfast and lunch should have been ~23 g; meals contained only 15 g of fiber. In general, sodium levels were high and above recommendations to consume no more than 2,300 mg of sodium per day (3,152 mg pre- and 2,508 mg post-intervention). Vitamin K increased by 58% at breakfast (P<0.001) and was unchanged at lunch (P = 0.973). Although vitamin K was below recommendations of 90 mcg for women and 120 mcg for men, additional consumption of leafy greens or vegetable oils at another meal could satisfy recommendations for daily intake. Calcium decreased slightly but the total amount in meals served post-intervention was slightly above the daily recommendation of 1,000 mg for adults ≤50 years (Ca = 1,016 mg); 1,200 mg is recommended for adults >50 years.

Table 1.

Energy and nutrients in meals served at two psychiatric rehabilitation centers

| Urban site |

Suburban site |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- | Post- | Mean differencea | P-value | Pre- | Post- | Mean difference | P-value | |

| Breakfast | ||||||||

| Calories (kcal) | 1,064.3 | 761.6 | −302.7 | 0.01 | 1,422.7 | 839.0 | −583.7 | 0.02 |

| Total fat (g) | 21.1 | 18.8 | −2.3 | 0.38 | 59.1 | 22.0 | −37.0 | 0.02 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 10.9 | 7.8 | −3.1 | 0.02 | 20.8 | 6.1 | −14.7 | 0.04 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 4.1 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 19.4 | 7.0 | −12.4 | 0.02 |

| Protein (g) | 27.6 | 27.3 | −0.3 | 0.92 | 45.4 | 35.9 | −9.5 | 0.37 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 197.5 | 126.4 | −71.1 | <0.01 | 181.5 | 130.2 | −51.3 | 0.03 |

| Total sugars (g) | 127.4 | 72.8 | −54.6 | <0.01 | 92.9 | 44.5 | −48.4 | 0.01 |

| Fiber (g) | 7.3 | 8.2 | 0.9 | 0.64 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0.1 | 0.95 |

| Calcium (mg) | 815.7 | 660.7 | −155.1 | 0.07 | 1,095.1 | 539.9 | −555.2 | 0.12 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 1,998.6 | 2,134.0 | 325.4 | 0.17 | 2,447.0 | 1,839.6 | −607.5 | 0.26 |

| Vitamin K (mcg) | 2.3 | 7.3 | 5.0 | <0.01 | 13.6 | 5.9 | −7.6 | 0.01 |

| Potassium (mg) | 1,596.7 | 1,616.3 | 19.6 | 0.89 | 2,007.1 | 1,024.2 | −982.9 | 0.05 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 138.7 | 146.1 | 8.4 | 0.76 | 150.4 | 96.2 | −54.1 | 0.11 |

| Sodium (mg) | 854.7 | 765.1 | −89.6 | 0.47 | 1,627.2 | 1,564.3 | −62.9 | 0.86 |

| Lunch | ||||||||

| Calories (kcal) | 1,196.5 | 846.9 | −349.6 | 0.01 | 980.2 | 1,066.7 | 86.6 | 0.57 |

| Total fat (g) | 37.9 | 34.9 | −3.0 | 0.75 | 46.2 | 35.5 | −10.7 | 0.24 |

| Saturated Fat (g) | 11.8 | 11.0 | −0.8 | 0.81 | 18.4 | 11.8 | −6.5 | 0.06 |

| Monounsaturated Fat (g) | 8.3 | 8.4 | 0.1 | 0.79 | 5.7 | 3.0 | −2.7 | 0.30 |

| Protein (g) | 48.1 | 34.9 | −13.2 | 0.06 | 41.3 | 43.3 | 2.0 | 0.81 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 168.5 | 98.6 | −69.9 | <0.01 | 102.5 | 145.3 | 42.8 | 0.03 |

| Total sugars (g) | 89.7 | 38.0 | −51.7 | <0.01 | 48.1 | 54.7 | 6.6 | 0.37 |

| Fiber (g) | 9.4 | 6.5 | −2.9 | 0.19 | 5.6 | 10.0 | 4.4 | 0.03 |

| Calcium (mg) | 585.3 | 354.8 | −230.5 | 0.01 | 454.4 | 522.5 | 68.1 | 0.29 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 1,189.7 | 2,592.2 | 1,402.5 | 0.34 | 1,854.9 | 5,950.4 | 4,095.5 | 0.13 |

| Vitamin K (mcg) | 39.5 | 38.9 | −0.7 | 0.97 | 19.1 | 19.3 | 0.20 | 0.97 |

| Potassium (mg) | 1,066.0 | 829.8 | −236.2 | 0.35 | 1,077.5 | 895.1 | −182.4 | 0.27 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 90.5 | 62.9 | −27.7 | 0.18 | 57.3 | 49.9 | −7.5 | 0.48 |

| Sodium (mg) | 2,297.7 | 1,743.1 | −554.6 | 0.21 | 1,810.0 | 2,010.3 | 200.3 | 0.53 |

The significant P-values are printed in bold

Difference = Post–Pre

Fig. 1.

Calories and change in calories for breakfast and lunch at two PRPs. Asterisk indicates statistical significance, P<0.05

Suburban Site

Total energy decreased by 41% (584 kcals) at breakfast (P = 0.018) with no significant difference at lunch at site 2 (P = 0.573) (Table 1; Fig. 1). Saturated fat was significantly reduced at breakfast by 15 g (21 g vs. 6 g, P = 0.036). At the end of the intervention, total carbohydrates were significantly lower at breakfast (P = 0.029) but higher at lunch (P = 0.033). Total sugars significantly decreased at breakfast from 93 to 45 g (P = 0.001). Total dietary fiber at lunch nearly doubled at the end of the intervention (P = 0.030) but remained below recommendations of 14 g fiber per 1,000 kcals. Vitamin K decreased by 57% at breakfast (P = 0.009) and total vitamin K for breakfast and lunch was well below daily recommendations (Vitamin K = 25 mcg). Calcium in both meals sufficiently met daily recommendations for adults ≤50 years but was less than what is recommended for adults >50 years (Ca = 1,062 mg). There was no change in sodium; levels were well above daily recommendations with both meals containing 3,574 mg post-intervention.

Discussion

The objective of this report was to assess the effectiveness of an environmental nutrition intervention aimed at reducing calories and improving diet quality in meals served at PRPs. To our knowledge, this is one of the first environmental dietary interventions that attempted to work with psychiatric rehabilitation programs to improve the quality of meals served. Our results indicate that the intervention was effective in decreasing the total energy of meals served and altering diet composition; these results are encouraging given that this is a vulnerable population that consumes many meals in institutional settings. Similar interventions could have a significant effect on weight loss and maintenance in this population.

Both sites were effective in reducing the total number of calories in meals served. The urban site made significant improvements in decreasing calories at both meals; a 29% reduction in total calories was achieved. A large proportion of the decrease in breakfast calories came from the removal of sugar containers that participants could freely use in the cafeteria. In addition, this site was willing to decrease desserts, which contributed to the significant reduction in calories and sugars at lunch. Although the suburban site did not effectively reduce the number of calories at lunch, a 21% reduction in calories from both meals was obtained mainly through reducing calories at breakfast. This site reduced sugars at breakfast by purchasing lower-sugar prepared cereals after the supply from the start of the pilot was gone and reduced fat by only occasionally serving high-fat breakfast meats. Management’s unwillingness to eliminate desserts may be one reason why calories were not reduced at lunch. Despite these changes, there is certainly more room for improvement; persons attending either center would most likely exceed the average number of calories needed per day (for sedentary females, 1,800 kcals/d; males 2,200 kcal/day) by consuming another meal and/or snack. Nevertheless, these results are noteworthy because over just a 6 month period with a limited number of intervention contacts, both sites were able to make substantial changes. The PRPs were able to reduce meals by 500–650 calories per day, and a 3,500 calorie deficit is required for one pound of weight loss. Thus, the PRPs made meal changes which could translate to a 1–1.3 lb weight loss after 7 days of eating at the PRP; this is an important contribution to an overall weight loss program. Although calories were reduced, diet quality also could be improved without significantly increasing cost if sites were to limit the use of prepared foods, buy lower sodium canned products and remove salt from the cafeteria.

Each PRP was unique with regards to staff responsibilities and beliefs, financial and resource constraints and the willingness to attempt to serve healthier, lower-calorie meals. For example, at the suburban site, the person responsible for preparing and serving meals was also in charge of transporting individuals at the center to and from their home; thus, the responsibilities before and after meals left less time to cook from scratch and, consequently, to be more reliant on processed foods. Furthermore, changes to food service require a collaborative effort and the tradition of serving prepared foods was routine and comfortable. This may be one reason why this site was unable to reduce calories at lunch. Second, some kitchen staff believed that members would not receive another full meal after they left the center and, therefore, felt that large, hearty meals were necessary. This is often a misconception since most persons with SMI reside in group homes or with a legal guardian that provides another meal in the evening. In addition, PRP staff always work towards making the clients happy and participants often get pleasure from food. Despite a decrease in calories at the end of the intervention, both sites were still serving higher-calorie meals; therefore, the notion that persons with SMI should consume most of their calories at the PRP may have hindered efforts to further reduce calories. Third, a successful intervention relied on recognizing and working within the, often limited, resources that were available at the center, including high staff turnover and meager funding from Medicare and Medicaid. Fourth, to obtain federal reimbursement for meal costs, the PRP is required to follow the Child and Adult Care Food Program regulations; therefore, anything above the reimbursement threshold would be at the expense of the PRP. Preparing menus that not only meet the regulation criteria but are also financially feasible can be a challenge without a supportive environment and knowledgeable staff; nevertheless, the sites in the current study were able to make changes under restrictive circumstances. Finally, nutritional knowledge is often limited. Hence, while most kitchen staff were receptive to the intervention, changes did not always occur due to the issues described above.

Despite the success of the interventions, some modifications should enhance the success in future programs. Improvements include (1) committing to standardized follow-up consultations rather than using an ad hoc approach and (2) creating a standardized form for ESHA analysis that captures specific information on the preparation methods and serving sizes of menu items. Furthermore, it is important to increase support for the intervention from the kitchen staff and directors at the institution. To this end, emphasis should be placed on: (1) the importance of a healthy diet in this vulnerable population, (2) the belief that the dietary behaviors learned at the center will influence dietary behaviors in other settings and (3) the concept that a reduction in the calories of meals served could significantly affect weight loss success.

In summary, this report indicates that a nutritional intervention designed to reduce the calories of institutional meals is feasible and effective at PRPs. Such interventions have the potential to substantially improve the health of this underserved population.

Contributor Information

Sarah Stark Casagrande, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; Social and Scientific Systems, 8757 Georgia Ave, 12th Floor, Silver Spring, MD 20910, USA, scasagrande@s-3.com.

Arlene Dalcin, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Phyllis McCarron, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Lawrence J. Appel, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Debra Gayles, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Jennifer Hayes, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Gail Daumit, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

References

- Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Heo M, Mentore JL, Cappelleri JC, Chandler LP, et al. (1999a). The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(4), 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, et al. (1999b). Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: A comprehensive research synthesis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(11), 1686–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, & Thun MJ (2003). Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(17), 1625–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2001). Intake of calories and selected nutrients for the United States population, 1999–2000. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients- United States, 1971–2000, morbidity and mortality weekly report. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; Report No.: 53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumit GL, Dalcin AT, Jerome GJ, Young DR, Charleston J, Crum RM, et al. (2010). A behavioral weight-loss intervention for persons with serious mental illness in psychiatric rehabilitation centers. International Journal of Obesity (London). doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis B, Mobley C, Stadler DD, Hartstein J, Virus A, Volpe SL, et al. (2009). Rationale, design and methods of the HEALTHY study nutrition intervention component. International Journal of Obesity (London), 33(Suppl 4), S29–S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, Wilson PW, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, et al. (2002). Obesity and the risk of heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(5), 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryland State Department of Education. (2003). In School and Community Nutrition Programs (Ed.). Fact sheet: The child and adult care food program- adult day care componenet. United States: Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, & Koplan JP (2001). The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA, 286(10), 1195–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs GS, & Guille C (1999). Weight gain associated with use of psychotropic medications. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(Suppl 21), 16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski S (2000). Overweight, obesity and health risk: National task force on the prevention and treatment of obesity. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160, 898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]