Abstract

Although pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia was historically associated with HIV/AID patients, there is a recent shift in demographics with increasing incidence in patients with hematologic malignancies and transplants. A granulomatous response to pneumocytis jiroveci infection is uncommon and most commonly presents as multiple randomly distributed nodules on chest imaging. Granulomatous pneumocytis jiroveci pneumonia presents with similar clinical manifestations as typical pneumocytis pneumonia but is usually not detected by bronchoalveolar lavage and may require biopsy for a definitive diagnosis. For this reason, the radiologist may be the first provider to suggest this diagnosis and guide management.

Keywords: Granulomatous PJP, PCP, Pneumocytis, Immunocompromised

Introduction

Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP), formerly known as Pneumocystis Carinii Pneumonia, is a significant cause of infection in immunocompromised patients. Initially brought to light during the AIDS epidemic, it has also shown to be associated with the use of cytotoxic and immunosuppressive therapies [1]. At risk individuals are immunocompromised such as those with HIV, primary immunodeficiency, hematologic malignancies, solid tumors, and transplant recipients [1]. Non-HIV immunocompromised hosts now make up the majority of patients with pneumocystis pneumonia in industrialized countries [2] with the incidence shown to be on the rise in this population [3].

Classically, PJP pneumonia presents as ground glass opacities with or without cyst formation on HRCT imaging [4]. A smaller subset of patients with PJP have atypical imaging manifestations such as masses and nodular opacities which have been shown to represent granulomatous response to the PJP infection, known as granulomatous PJP (GPJP) [5]. Recognition of these atypical imaging manifestations is important as diagnostic considerations for pulmonary nodules and masses in immunocompromised patients often first include infectious etiology such as fungi, lung cancer, metastatic disease, hematological malignancy, and lymphoproliferative disorders [6]. Herein we report a case of GPJP as the heralding event in a patient subsequently diagnosed with peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

Case report

A forty-nine-year-old female with a history of recurrent pneumonia and asthma developed worsening dyspnea for 6 months before presenting to the emergency department for shortness of breath, dry cough, and wheezing. An initial chest x-ray was reported as negative. She was diagnosed with an acute asthma exacerbation and was discharged home on prednisone. The patient was seen in an outpatient facility 5 days later for persistence of symptoms despite adherence to therapy as well as interval development of a rash on the face and arms. She was subsequently found to have new chest x-ray infiltrates. A HRCT revealed airway inflammatory changes, ground glass opacities, and consolidation (Fig. 1). At this time, the primary consideration was an atypical infection.

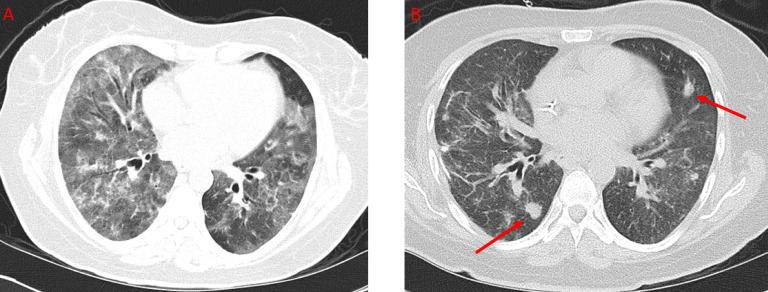

Fig. 1.

Axial CT of the thorax without IV contrast. A shows widespread ground glass opacities and interstitial thickening in a patient presenting with worsening dyspnea for six months. B shows the same patient with interval development of multiple nodules one month later.

The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital due to worsening respiratory distress and further history revealed a 30 lbs weight lost in the preceding 3 months. Laboratory testing revealed new onset leukopenia and HIV tests were negative. A bronchoalveolar lavage was performed which showed abundant pneumocystis jiroveci organisms. The patient received a 2-week course of TMP-SMX and followed by a 1-week course of atovaquone, both of which did not result in any significant clinical improvement. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery wedge lung biopsies were then obtained and showed well-formed granulomas with pneumocystis jiroveci within the granulomas (Fig. 2). No lymphomatous infiltrates or other organisms were found. A CT obtained shortly thereafter and approximately 1 month after initial CT imaging demonstrated multiple new nodules in her lungs, most in the 1 cm range, which were correlated with the pathologic results of granulomatous PJP infection (Fig. 1).

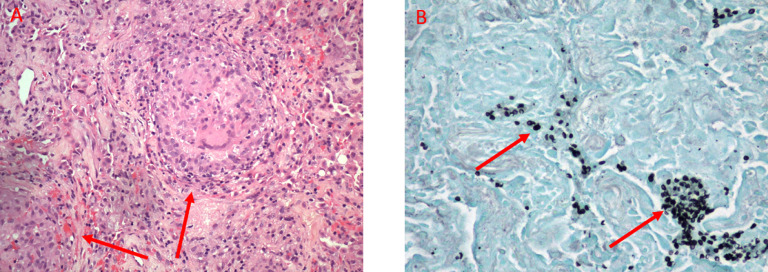

Fig. 2.

Histologic images from Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery biopsy of right middle and lower lobes nodules performed about one month after the initial CT demonstrates diffuse granulomas (arrows) containing micro-organisms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain (A). These were confirmed to represent Pneumocystis Jiroveci (arrows) on Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain (B).

A third line therapy consisting of 3 weeks of clindamycin and primaquine was initiated which eventually led to symptomatic improvement. An MRI of the left forearm performed due to swelling revealed extensive edema and enlargement of the extensor muscle group involving predominately the extensor carpi radialis longus. A biopsy of the area confirmed a diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. She was eventually discharged in stable condition. She received 1 cycle of CHOEP (Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, Vincristine, Etoposide, and Dexamethasone) and subsequent salvage chemotherapy with Romidepsin for new lesions.

Discussion

Patients with GPJP present with symptoms similar to that of typical PJP infection, most commonly dyspnea, cough, and fever. Rarely patients present with unique clinical findings including chest pain from chest wall and pleural involvement [7], [8] as well as hypercalcemia related to the numerous granulomas [9]. A stronger association of GPJP with hematologic malignancy compared to HIV/AIDS has been reported [10]. A multicenter retrospective study comparing the presentation of PJP in patient with AIDS vs malignancy demonstrated nodular lesions in 1 out the seventeen (6%) patients with AIDS and 5 out of twenty-one (24%) patients with malignancy [11]. Most of the malignancies reported in that study were hematologic (16/21) [11]. On average, GPJP developed 2 weeks to 2 months after stopping corticosteroids and 3-8 weeks after initiating HAART [12].

It has been reported that up to 81% of GPJP cases show pulmonary nodules on imaging [10]. When present, they are often multiple and randomly distributed [5], [12]; however, solitary pulmonary nodules [13], [14] and masses [15] have been reported. Nodules can range from a few millimeters to greater than 1 cm [4], although there have been reports of masses as large as 7 cm [15], [16]. A significant minority (17%) have diffuse infiltrates without nodules [10]. Two studies have reported the appearance of nodules on radiographs and CT scans a few days after a negative study, showing that these granulomas can develop quickly [13], [17]. Enlarging nodules over weeks to months was a consistent finding in multiple studies in patients who were not being treated adequately [18], [19], [20]. The nodules have been shown to demonstrate new cavitation over a period of days [13]. In some studies, the nodules shrunk or persisted on imaging even after treatment and resolution of symptoms [21], [22], [23].

It is also important to note that nodular opacities particularly in immunocompromised patients are not specific to GPJP. A retrospective analysis of 39 patients with PJP showed 7 patients (18%) to have nodules and nodular components [24]. In 6 of the 7 patients (86%), a second disease process affecting the lungs was discovered upon biopsy. These included mycobacterial and fungal infections, leukemic nodules, Kaposi's sarcoma, lymphoma, and bronchogenic carcinoma [24]. This underscores the need to biopsy pulmonary nodules in an immunocompromised patient as more than one process may be present [24]. Additional atypical parenchymal features of PJP infection include lobar consolidation and airway abnormalities including bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis, bronchiolitis obliterans, and rarely an endobronchial lesion [25]. Associated atypical extrapulmonary findings include regional lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions [25].

Histologically, nodules and masses have been demonstrated to represent a granulomatous response to PJP [5], [12]. The characteristic feature of GPJP is pneumocystis organisms within granulomas on Gomori methenamine silver stained sections [10] (Fig. 2). PJP appears as thin-walled, spherical nonbudding cysts [10]. Granulomas are more commonly necrotizing and multiple. Currently, the mechanism of granuloma formation for PJP remains unclear [10]. The diagnosis of a GPJP requires the presence of pneumocystis organisms inside a granuloma and the absence of other pathogens such as bacteria, mycobacteria, or fungi [26]. Formation of granulomas likely influences the ability to detect pneumocystis jiroveci on traditional diagnostic procedures such as bronchoalveolar lavage which is likely to be negative [10]. This is speculated to be the result of PCP encapsulation by the granuloma, in distinction to typical PJP infection where the organism is found in abundance within the alveoli.

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and open lung biopsy are the more reliable diagnostic modalities [10]. A disease fatality rate of 46% has been reported although treatment regimens for these patients were not provided [10]. Like typical PJP, treatment for GPJP is usually TMP-SMX although patients often experience a more prolonged course of therapy, higher treatment failures and increased need for multidrug regimens than typical PJP [26], [27].

Conclusion

GPJP presents in a similar fashion to typical PJP but has a higher association with hematological malignancy than HIV/AIDS. Although not specific, randomly distributed solid pulmonary nodules are the most common image finding. Our case highlights the need for evaluation for an occult hematologic malignancy in the setting of an HIV negative patient diagnosed with GPJP.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Catherinot E., Lanternier F., Bougnoux M., Lecuit M., Couderc L., Lortholary O. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2010;24(1):107–138. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikaelsson L., Jacobsson G., Andersson R. Pneumocystis pneumonia—a retrospective study 1991–2001 in gothenburg, sweden. J Infect. 2006;53(4):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russian D.A., Levine S.J. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without HIV infection. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321(1):56–65. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanne J.P., Yandow D.R., Meyer C.A. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia: high-resolution CT findings in patients with and without HIV infection. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(6):W555–W561. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis W.D., Pittaluga S., Lipschik G.Y. Atypical pathologic manifestations of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: Review of 123 lung biopsies from 76 patients with emphasis on cysts, vascular invasion, vasculitis, and granulomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14(7):615–625. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copp D., Godwin J., Kirby K., Limaye A. Clinical and radiologic factors associated with pulmonary nodule etiology in organ transplant recipients. American J Transpl. 2006;6(11):2759–2764. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gal A.A., Plummer A.L., Langston A.A., Mansour K.A. Granulomatous pneumocystis carinii pneumonia complicating hematopoietic cell transplantation. Pathol—Res Pract. 2002;198(8):553–558. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauffer L., Kini J.A., Costello P., Godleski J. Granulomatous pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a non-AIDS patient: an atypical presentation. J Thorac Imaging. 2004;19(3):196–199. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000122370.03620.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramalho J., Bacelar Marques I., Aguirre A. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia with an atypical granulomatous response after kidney transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16(2):315–319. doi: 10.1111/tid.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartel P.H., Shilo K., Klassen-Fischer M. Granulomatous reaction to pneumocystis jirovecii: clinicopathologic review of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(5):730–734. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9f16a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tasaka S., Tokuda H., Sakai F. Comparison of clinical and radiological features of pneumocystis pneumonia between malignancy cases and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome cases: a multicenter study. Internal Med. 2010;49(4):273–281. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bondoc A.Y., White D.A. Granulomatous pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with malignancy. Thorax. 2002;57(5):435–437. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.5.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrio J.L., Suarez M., Rodriguez J.L., Saldana M.J., Pitchenik A.E. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia presenting as cavitating and noncavitating solitary pulmonary nodules in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome 1, 2. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134(5):1094–1096. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleindienst R., Fend F., Prior C., Margreiter R., Vogel W. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia associated with pneumocystis carinii infection in a liver transplant patient receiving tacrolimus. Clin Transpl. 1999;13(1):65–67. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.t01-1-130111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuinness G. Changing trends in the pulmonary manifestations of AIDS. Radiol Clin N Am. 1997;35(5):1029–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatt M., Muller M., Sabatini M. Solitary pulmonary granulomatous pneumocystosis. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(4):343–344. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-4-343_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bier S., Halton K., Krivisky B., Leonidas J. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia presenting as a single pulmonary nodule. Pediatr Radiol. 1986;16(1):59–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02387509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabur N.F., Kelly M.M., Gill M.J., Ainslie M.D., Pendharkar S.R. Granulomatous pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia associated with immune reconstituted HIV. Can Respir J. 2011;18(6):e86–e88. doi: 10.1155/2011/539528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar N., Bazari F., Rhodes A., Chua F., Tinwell B. Chronic pneumocystis jiroveci presenting as asymptomatic granulomatous pulmonary nodules in lymphoma. J Infect. 2011;62(6):484–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam J., Kelly M., Leigh R., Parkins M. Granulomatous PJP presenting as a solitary lung nodule in an immune competent female. Respir Med Case Rep. 2014;11:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazzan M., Copin M., Pruvot F., et al. Lung granulomatous pneumocystosis after kidney transplantation: an uncommon complication 1997;29(5):2409. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Leroy X., Copin M., Ramon P., Jouet J., Gosselin B. Nodular granulomatous pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a bone marrow transplant recipient. APMIS. 2000;108(5):363–366. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-69.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oki Y., Kami M., Kishi Y. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia with an atypical granulomatous response in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;41(3-4):435–438. doi: 10.3109/10428190109058001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhlman J.E., Kavuru M., Fishman E.K., Siegelman S.S. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: spectrum of parenchymal CT findings. Radiology. 1990;175(3):711–714. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boiselle P.M., Crans C.A., Jr., Kaplan M.A. The changing face of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in AIDS patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172(5):1301–1309. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.5.10227507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ullmer E., Mayr M., Binet I. Granulomatous pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in wegener's granulomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(1):213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kester K.E., Byrd J.C., Rearden T.P., Zacher L.L., Cragun W.H., Hargis J.B. Granulomatous pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with low-grade lymphoid malignancies: a diagnostic dilemma. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(6):1111–1112. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]