Abstract

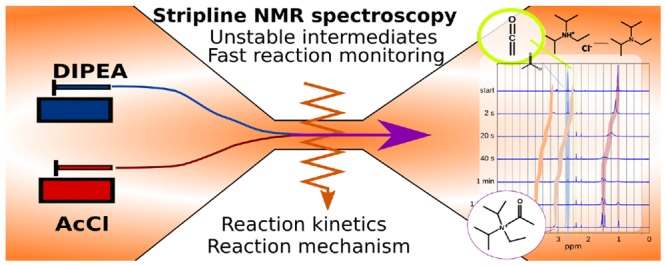

We present an in-depth study of the acetylation of benzyl alcohol in the presence of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) monitoring of the reaction from 1.5 s to several minutes. We have adapted the NMR setup to be compatible to microreactor technology, scaling down the typical sample volume of commercial NMR probes (500 μL) to a microfluidic stripline setup with 150 nL detection volume. Inline spectra are obtained to monitor the kinetics and unravel the reaction mechanism of this industrially relevant reaction. The experiments are combined with conventional 2D NMR measurements to identify the reaction products. In addition, we replace DIPEA with triethylamine and pyridine to validate the reaction mechanism for different amine catalysts. In all three acetylation reactions, we find that the acetyl ammonium ion is a key intermediate. The formation of ketene is observed during the first minutes of the reaction when tertiary amines were present. The pyridine-catalyzed reaction proceeds via a different mechanism.

Introduction

Spectroscopic techniques are extensively used in organic chemistry for analyzing molecular compounds and for monitoring chemical reactions because they provide quantitative chemical information at the molecular level. Gas/liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (GC/LC–MS), infrared (IR) spectroscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy are methods that are frequently employed.1−4 Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a particularly versatile technique and is the method of choice for elucidation of molecular structure of organic compounds in a broad range of fields.5 NMR has also proven to be very suitable for the study of organic reactions.6−8

Microscale chemical reactions are attracting increasing attention in chemical research.9−11 Compared to conventional batch reactors, microreactors have extremely high surface-to-volume ratios, which allows for better heat exchange and mass transfer.12,13 The small volumes, which are typically involved, enable potentially dangerous and/or fast reactions, such as exothermic reactions or reactions with flammable, explosive, toxic, or hazardous chemicals, to be performed under relatively safe conditions. Some recent examples employ the controlled environment of the microreactor and the increased mass and heat transfer capabilities. The autoxidation of olefins was performed in a microreactor, which improved safety and yield due to increased mass transfer and increased temperature.14 Also, fluorine reactions, which are in batch difficult to control and unstable, involving hazardous compounds that are difficult to handle, were successfully performed using microreactor-based continuous flow chemistry, due to the fast mixing, high heat, and mass transfer in a microreactor.15 Cantillo16 et al. developed a procedure for the synthesis of triaminophlorogluconol, an important compound for industrial and medical use, involving a very unstable and explosive intermediate, which could be safely performed in continuous flow in a microreactor using a thermostated ultrasound bath for controlling the temperature of this exothermic reaction.

Mixing of reactants in conventional reactions occurs by convection and turbulence. Microfluidic systems have low Reynold numbers and therefore operate in the laminar flow regime, where mixing takes place mainly by mass transfer through diffusion. The diffusion distance may be decreased by using split-and-recombine mixing elements in the microreactor: flows are split up, deformed, and recombined, creating thin layers of laminar flows. Whereas turbulent mixing can give rise to large concentration gradients, microfluidic diffusion-limited mixing is more homogeneous, and the reaction progress is more reproducible as a result. This enhances chemical selectivity and significantly suppresses side product formation.17 The reproducibility is also a great advantage in efficient screening or optimization of reactions, which is of considerable interest for a variety of pharmaceutical and industrial processes and for research and development in organic chemistry. High throughput optimization in microfluidic setups is achieved at reduced costs, due to low material requirements and low waste generation,18 even for dangerous and explosive compounds.19

With the developments in microreactor technology comes a growing interest in online spectroscopic analysis techniques.20,21 For accurate monitoring of fast reaction intermediates, it is required that the applied spectroscopic technique operates at the same volumetric scale as the microreactor,22 and in order to be able to follow the reaction in situ, this method should be integrated with the reaction element, which calls for the scaling down of the NMR volume. Miniaturization of the NMR detection coil increases mass sensitivity,23 i.e., scaling down of the NMR coil increases the sensitivity per unit mass but decreases the sensitivity per unit concentration.24 For a sample with a certain, limited concentration, but sufficient volume available, the sensitivity of a measurement is decreased for smaller coil. For samples with limited mass, however, sensitivity increases when the coil is better fitted to the size of the sample. This is beneficial not only for mass-limited samples but also for the limited volumes that are present in the microfluidic reactions. Considerable effort has been devoted to the development of microscale NMR techniques, and several approaches for microcoil NMR have been explored.25−28 Different types of microcoils can be distinguished: microsolenoids wound around a capillary,29−31 planar spiral microcoils,32−35 and transmission line type (stripline or microslot) NMR detector.36−43 Our stripline based NMR chip38,44 consists of a planar copper structure in which a central flat wire is defined that excites and detects the nuclear spins, having a constriction where a high and homogeneous radio frequency (rf) field is generated, with a fluidic channel running directly above the copper strip. Furthermore, microfluidic connections can be straightforwardly applied so that a straightforward microfluidic setup for the study of microscale reactions in flow is realized.

Several groups have investigated the applicability of microscale NMR devices for inline reaction monitoring;45 Ciobanu et al.46 studied the reaction of d-xylose and borate by multiple physically distinct solenoidal microcoils. Wensink et al.47 presented a microfluidic chip with an integrated planar microcoil for the real-time monitoring of imine formation from benzaldehyde and aniline. Kakuta et al.48 monitored ubiquitin protein conformation by coupling a micromixer to a solenoidal NMR microcoil. More recently, Brächer et al.49 combined a microreactor with a capillary NMR flow cell, where the flow path and the solenoid NMR coil are thermostated using FC-43 (perfluorotributylamine). In this setup, as a test system a catalytic esterification of methanol with acetic acid was studied under isothermal conditions. Hyphenation of a continuous flow microreactor and a microfluidic NMR chip to determine kinetic parameters of a reaction with a single on-flow experiment was employed by Gomez et al.50

In an earlier study, we showed that the stripline-based microfluidic NMR setup could be conveniently used for reaction monitoring and analyzing mass-limited biological samples.44 This setup is further optimized for monitoring the amine base-catalyzed acetylation of benzyl alcohol in situ. Acetylation of hydroxyl groups is an important and fundamental process in organic chemistry. The acetylation is mostly used to protect alcohol groups from undesired side reactions but also to turn hydroxyl substituents into better leaving groups. It is frequently performed using an acid chloride in the presence of an amine to significantly speed up the reaction. We performed the acetylation with acetyl chloride in the presence of DIPEA, which gives a fast and exothermic reaction. The time scale of this reaction is several minutes, which can be perfectly monitored with our microfluidic NMR setup.

Despite the abundance of esterification examples with acetyl chloride, there is still discussion about the exact mechanism. The reaction mechanism for a base-catalyzed acetylation in general can be thought to proceed via base-assisted nucleophilic attack of the alcohol with acetyl chloride.51 However, it has also been suggested that the reaction proceeds via a tetrahedral intermediate (the quaternary acetyl ammonium ion)52 or via a highly reactive ketene intermediate that is formed through base-assisted alpha-elimination of HCl from acetyl chloride.53 Our setup enables the observation of unstable intermediates such as ketene. Complemented with conventional NMR measurements, this allows us to fully unravel the reaction mechanism. Furthermore, we applied different base catalysts to compare the mechanisms when different amines are involved.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

All chemicals were used as received without further purification and consisted of acetyl chloride (Fluka Analytical from Sigma-Aldrich), acetyl-2-13C chloride, 99 atom % 13C (Aldrich), benzyl alchohol (reagent Plus, Sigma-Aldrich), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (Biotech grade 99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich), triethylamine (Sigma-Aldrich), pyridine (Fluka analytical, puriss.p.a.), and chloroform-d3 + 0.05% v/v TMS (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) as a solvent.

Microfluidic Stripline NMR Setup

The stripline NMR chip used in these experiments has been described before.54 The stripline NMR chip is a microfabricated chip, where the rf coil consists of a copper stripline structure sputtered and electroplated onto the glass substrate. The analyte flows through the detection area via a microfluidic channel. The volume sensitive for detection is 150 nL. The chip is coupled to a standard microfluidic setup. Syringe pumps are used for providing a continuous flow of the reactants. Prior to entering the stripline NMR chip, the reactants are brought together using a Y-junction and subsequently flow into the chip using a fused silica (FS) capillary with 75 μm inner diameter (I.D.). A reaction volume of approximately 1 μL results.

From the point of the Y-junction, mixing takes place by laminar diffusion. By a rough approximation the mixing time from Fick’s law can be calculated to be approximately 1.4 s. More accurately, the Damköhler number can be estimated, which compares diffusion to reaction rate.55 For our reaction process the Damköhler number is around 1, so the reaction rate is possibly limited by the mixing process.

In a pressure-driven laminar flow through the capillary, a parabolic Poiseuille flow profile arises, instead of plug flow with a linear profile. Radial diffusion takes place, which disrupts the parabolic profile. Bodenstein numbers can be estimated, which gives an indication on the validity of assuming plug flow for the reaction.55 We find that for our microfluidic system the Bodenstein number is below 1000 for reaction times up to 30 s. So, small deviations from plug flow can be present up to reaction times of 30 s, where the differences between center velocity and flow rate at the wall may cause a velocity distribution.

An effective reaction time can be calculated by dividing flow rate with the reaction volume, so that depending on the applied flow rates, detection can take place at effective reaction times ranging from 1.5 s and 5 min. Details regarding the chip, probe and microfluidics setup can be found in the Supporting Information. Pictures and schematics of the stripline NMR chip and probe are shown in Figure S1.

In-Flow Measurements

For the reaction monitoring, a continuous flow of the reaction mixture to the stripline was established. After having set a new flow rate, a stabilization time depending on the flow rate was taken into account (varying from at least 1 min for high flow rates up to 15 min for low flow rates). Flow rates ranging from 20 μL/min down to 0.1 μL/min correspond to effective reaction times of 1.5 s to 5 min at the NMR measurement. A steady state spectrum is recorded and saved. The spectra were taken acquiring 4 or 16 scans, depending on the concentration of the analyte. The acquisition delay between scans varied between 5 s for the lower flow rates to 1 s for the higher flow rates, when the detection volume is refreshed faster. All spectra were recorded at room temperature on a VNMRS 600 MHz Varian NMR spectrometer operated with VNMRJ software.

The flow of analyte through the NMR detection area continuously replaces depolarized spins with polarized spins that did not yet receive an rf pulse. As a result, it is not necessary to wait for 5 times the relaxation time T1 for the spins to repolarize; therefore, the pulse repetition rate can be increased for an improved signal to noise ratio (SNR) per unit time.24,56 However, the residence time will increase signal line width for any spin not in the detection volume of the NMR probe for a period long enough to record a full free induction decay (FID), as determined by the transverse relaxation T2.57 The resulting increase in line width due to flow is inversely proportional to the residence time. Although the expected decrease in resolution with increasing flow rate occurs, the effect is minor, so that the intrinsic high resolution of the stripline chip still permits a spectral resolution of approximately 2 Hz for flow rates up to 50 μL/min.

From the spectrum of 0.5 M acetyl chloride in flow, a single scan SNR of 683 is estimated for the methyl peak. For calculation of the concentration within 1% error, at least a SNR of 150 is needed,59 which is valid for a concentration of more than 0.11 M. When accumulating 4 or 16 scans, the minimum concentration becomes 55 and 27 mM, respectively. An SNR of 1:3 is necessary for detection of a peak, corresponding to a minimum concentration of 2 mM in a single scan. The first measurement is acquired at an effective reaction time of 2 s. Intermediate products that have a lifetime of substantially less than 2 s will therefore not be observed. The time between the effective reaction times at the measurements varies between a few seconds at the beginning of the reaction up to a minute at the end of the reaction (selected spectra are shown in the figures). Intermediates that are not present at a time of measurement will not be present in the spectra. Furthermore, the acquisition time is 1 s; intermediates appearing and/or disappearing during this period will give dispersive and/or broadened lines.58

Temperature changes can be present as the reaction generates heat or in hot spots. According to guidelines provided by Westermann and Mleczko,60 we operate in a regime that does not have a high risk on hot spots; due to the small diameter of the reaction channel (75 μm), temperature rise is expected to remain well below 1 K.

Conventional NMR Experiments

The reaction mixtures were prepared in the fumehood, mixed in a tube, and allowed to equilibrate. After 15 min the mixtures were relatively stable, and the conventional NMR measurements were performed typically after a reaction time of around 2 h. After the desired reaction time, a sample was taken and put into a 5 mm (500 μL) NMR tube and subsequently measured with a commercially available probe in a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz NMR spectrometer operated with Bruker TopSpin 3.0 software. For each sample, a 1H spectrum, a 13C spectrum, a heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC)61 spectrum, and a heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC)62 spectrum was taken.

Data Processing

The data were processed with VnmrJ and matNMR.63 Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc. ACD/NMR Processor was used for plotting the conventional 2D experiments.64 The concentration of the methyl products during the reaction were monitored from the spectra measured in the stripline probe by deconvolution fitting of the peaks with MatNMR.63

Results and Discussion

Acetylation of Benzyl Alcohol with DIPEA

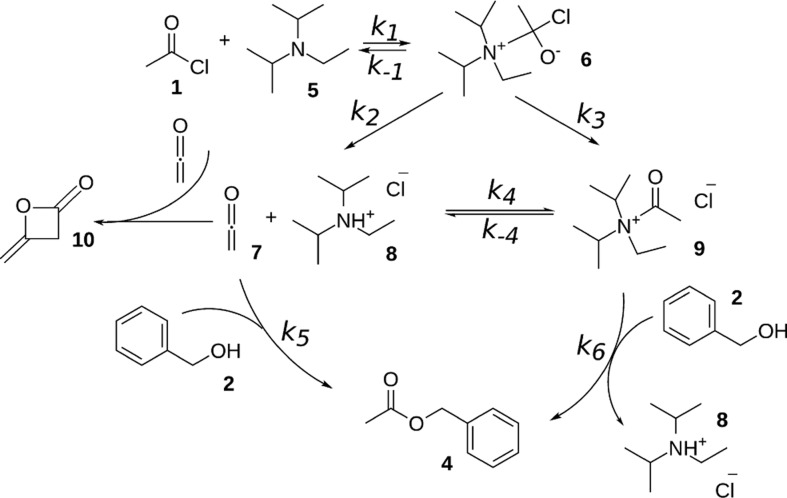

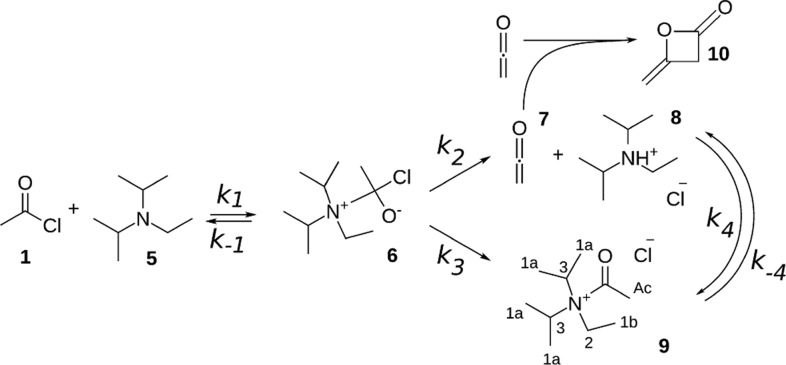

The acetylation of benzyl alcohol without a base catalyst is a slow reaction. The reaction proceeds via a tetrahedral intermediate and is completed in 1 day. In the Supporting Information, the reaction mechanism (Scheme S1) and a series of NMR spectra (Figure S2) that are taken during the conversion are shown. However, the presence of an amine significantly increases the reaction rate. Several mechanisms that can play a role have been suggested in the literature.52 First of all, HCl is formed in the nucleophilic addition–elimination reaction, and a basic amine can absorb HCl to form the corresponding ammonium salt. This would shift the equilibrium of the reaction to accelerate it. Therefore, we would expect to see protonation of DIPEA, and possibly the tetrahedral intermediate. Second, the basic amine can deprotonate the alcohol in trace amounts. However, this process is not expected to be a significant factor since acetyl chloride and DIPEA react vigorously. Third, it has been suggested that an acetyl ammonium ion might be formed.52,53 Acetyl chloride and the amine then react to give ketene and the protonated amine. Ketene is very reactive and reacts with the alcohol into an ester (reaction k5 in Scheme 1)65 or with the protonated amine to give an acetyl ammonium ion 9 (reaction k4 in Scheme 1).66,67 These various insights have been brought together in Scheme 1, which we will validate by detailed NMR analyses as described below.

Scheme 1. Proposed Reaction Mechanism of Benzyl Alcohol 2 with Acetyl Chloride 1 and DIPEA 5.

Acetyl chloride and DIPEA form an unstable tetrahedral intermediate 6, which gives ketene 7, protonated DIPEA 8, and acetyl-N,N-diisopropylethylammonium ion 9. Benzyl alcohol 2 reacts with ketene 7 or acetyl ammonium ion 9 into benzyl acetate 4. Diketene 10 is formed as a side product in trace amounts.

In Situ NMR Spectra

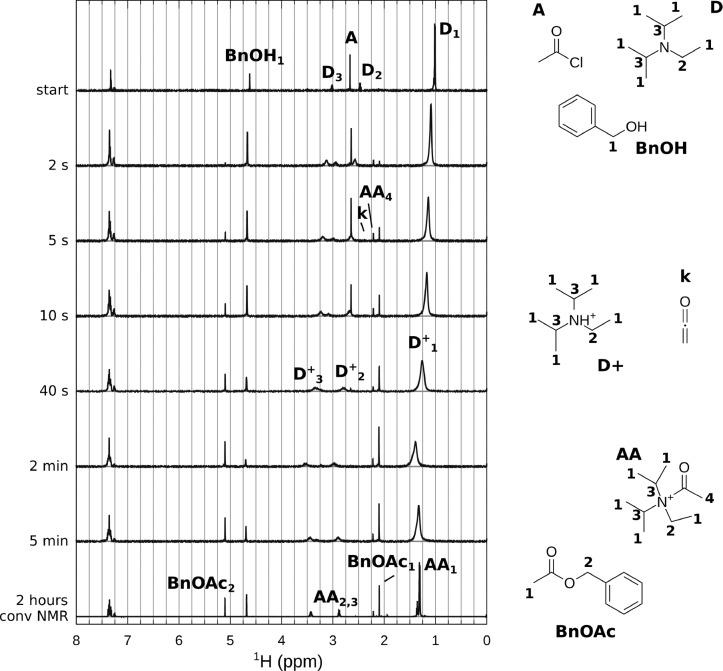

To get detailed insights in the reaction mechanism of this fast amine catalyzed acetylation, we performed the reactions in a microfluidic setup (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). The syringes were loaded with A, 0.5 M benzyl alcohol with 0.5 M DIPEA, and B, 0.5 M acetyl chloride. Comparing the spectra of DIPEA and DIPEA with benzyl alcohol, protonation of DIPEA from benzyl alcohol is not observed. By keeping the flow rates constant at a certain flow rate during the acquisition we obtained a steady state spectrum, while the reaction is in progress. By adjustment of the flow rates A and B, a series of steady state spectra was obtained at effective reaction times ranging from 1.5 s up to 5 min. Selected spectra and a conventional NMR spectrum are shown in Figure 1. Table S1 in the Supporting Information gives an overview of the methyl peaks observed in the reactions discussed in this Article.

Figure 1.

Selected spectra for the reaction of benzyl alcohol 2 (0.5 M) with acetyl chloride 1 (0.5 M) in the presence of DIPEA 5 (0.5 M). (Top) Unreacted compounds: acetyl chloride (A), DIPEA (D), and benzyl alcohol (BnOH). The series of in situ spectra shows the broadening and shifting of DIPEA peaks, formation of product benzyl acetate 4 (BnOAc), and intermediate peaks marked “k” (ketene 7) and “AA4” (acetyl group of acetyl ammonium ion 9). (Bottom) Conventional NMR spectrum after 2 h reaction time; the slightly broadened DIPEA peaks are shifted to a position of protonated DIPEA 8 and/or acetyl ammonium ion 9 (“AA”).

In the “conventional” NMR spectrum (bottom of Figure 1), taken after 2 h reaction time, we observe the DIPEA peaks at a position (marked “AA”) shifted with respect to the original position (marked “D” in the top spectrum of the unreacted compounds), which indicates the protonation of the amine. There are two main methyl resonances present; the benzyl acetate peak at 2.09 ppm (BnOAc1) and a smaller peak at 2.23 ppm, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

More information can be obtained from the analysis of the stripline NMR spectra of the ongoing reaction shown in Figure 1. The conversion into benzyl acetate can be monitored nicely using the resonances of the alpha protons. The spectra show the shifting and broadening of the DIPEA peaks (from “D” to “D+” and “AA”), and four peaks in the methyl region can be observed: acetyl chloride (2.69 ppm, labeled “A”), two intermediates at 2.4 ppm (“k”) and 2.23 ppm (“AA4”), and benzyl acetate at 2.09 ppm (“BnOAc1”).

To simplify the identification of the different steps in the reaction, the interaction of DIPEA 5 and acetyl chloride 1 was studied separately. Experiments are performed in a similar way, with syringe A, acetyl chloride (0.5 M), and syringe B, DIPEA (0.5 M). Figure 2 shows selected spectra acquired in the stripline NMR chip, and two conventional NMR spectra acquired after 2 h and 2 days reaction time. Since all of these peaks are still present in the conventional NMR spectrum after 2 h reaction time, we were able to perform conventional 2D NMR experiments of these reaction products. In order to come to a reaction mechanism, we first need to assign the various resonances in the stripline and conventional NMR spectra.

Figure 2.

Selected spectra for the reaction of acetyl chloride (0.5 M) with DIPEA (0.5 M). (Top) Unreacted compounds: acetyl chloride 1 (A) and DIPEA 5 (D). The series of in situ spectra shows the broadening and shifting of DIPEA peaks, intermediate peaks marked “k” (ketene 7) and “AA4” (acetyl group of acetyl ammonium ion 9). (Bottom) Two conventional NMR spectra. After 2 h reaction time, the DIPEA peaks are found at the original position (D) and at shifted position acetyl ammonium ion 9 (“AA1,2,3”), the main methyl product is associated with the acetyl group of the acetyl ammonium ion 9 (AA4). After 2 days reaction time, the DIPEA/acetyl ammonium ion peaks are broadened.

Protonation of DIPEA

The spectra in Figure 2 clearly show that the DIPEA peaks first broaden, then split. Three main resonances are present in the methyl region (2.69 ppm (AcCl), 2.4 ppm, 2.23 ppm); see also Table S1 in the Supporting Information. A similar effect is seen in the spectra of the full reaction obtained with the stripline probe (Figure 1) showing that the DIPEA peaks broaden and shift as the reaction proceeds. This suggests (partial) protonation of DIPEA.

| 1 |

If the resulting protonation/deprotonation process is a fast exchange process, the position of the resulting (narrow) peak in the NMR spectrum is the weighted average of the shift of the protonated and unprotonated resonances, whereas in the slow exchange limit these separate resonances would both be present in the spectrum.68 Since we observe a broadened, averaged signal, we conclude that this is an intermediate exchange process, meaning that the proton is exchanged from one molecule to another on the NMR time scale. The observed chemical shift δ is the population averaged shift, where the populations γi are the relative concentrations:

| 2 |

For intermediate exchange rates NMR peaks broaden as observed in the spectra, meaning the lifetime of the species is shorter than the transverse relaxation time T2 and of similar magnitude of the frequency difference of the individual resonances.68 As the reaction progresses, the position of the broadened DIPEA peak moves from the original chemical shift of the unprotonated DIPEA to a position similar to the protonated DIPEA chemical shift. This shift reflects the gradually increasing protonation of DIPEA during the course of the reaction.

Reaction Products of Acetyl Chloride

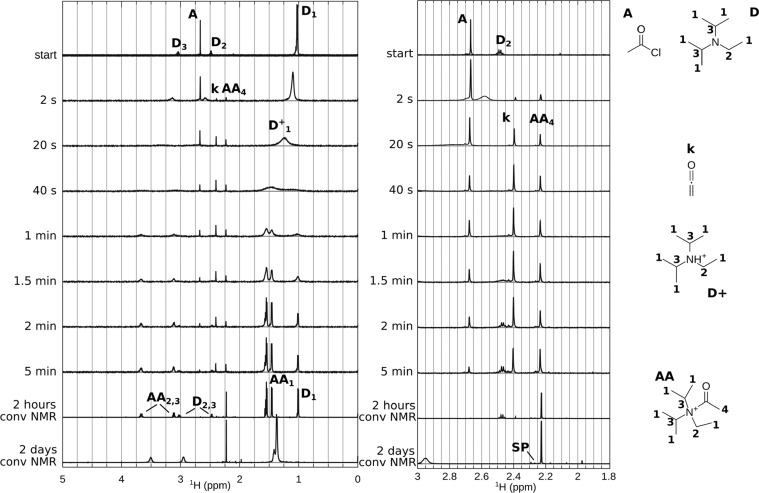

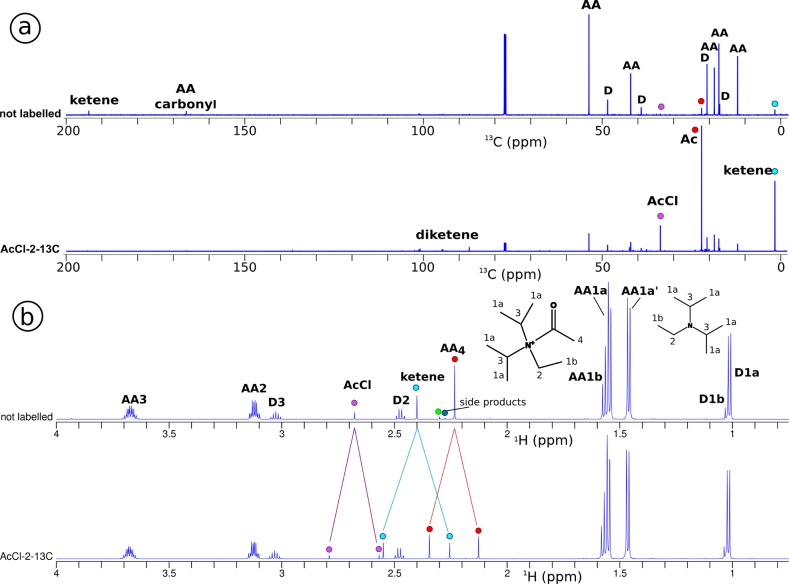

To unravel which resonances correspond to the reaction products of acetyl chloride, labeled acetyl chloride-2-13C was used for the reaction with DIPEA. Figure 3 shows the conventional 13C and 1H NMR spectra after 2 h reaction time for reactions using either natural abundance or 13C labeled acetyl chloride. Since we observed protonated DIPEA 8, the formation of ketene 7 as an intermediate in the reaction is a possible consequence in this part of the reaction. The 13C chemical shifts of ketene are known from literature to be 2.5 and 194 ppm.69 Both peaks are indeed observed in the 13C spectrum (Figure 3a), confirming the presence of ketene 7 in the reaction mixture.

Figure 3.

DIPEA (0.5 M) and AcCl (0.5 M) after 2 h reaction time, for natural abundance and 13C-labeled AcCl, measured in a conventional 600 MHz NMR spectrometer. In the 13C spectra (a), the peaks of labeled products in the bottom spectrum are enlarged; the bottom spectrum has been scaled down (1:6, relative to the CDCl3 peaks) to accommodate for these intensity differences. The peaks of labeled products that are increased are mainly acetyl chloride 1, the acetyl group of acetyl ammonium ion 9 (AA4) and ketene 7, but also diketene 10 and some side products are found. In the natural abundance spectrum, we see also the carbons from the carbonyl groups for ketene 7 and acetyl ammonium ion 9 (AA). In the 1H spectra (b), the peaks belonging to DIPEA 5 are indicated with D1a-1b, D2, and D3. The acetyl ammonium ion peaks are at a position shifted from the DIPEA, indicated with AA1a-1b (partly overlapping), AA2, and AA3. Due to 13C-labeling of acetyl chloride, splitting due to JCH coupling of the acetyl chloride 1 and product methyl peaks occurs: ketene 7 and acetyl ammonium ion 9 (AA4), marked with dots. Due to hindered rotation, the acetyl ammonium ion peaks (AA1–3) are split, which is visible in this spectrum.

The peaks that belong to the reaction products of acetyl chloride can be identified by their increased peak intensity in the spectrum of the reaction performed with labeled acetyl chloride relative to the spectrum with natural abundance acetyl chloride. The methyl region (below 50 ppm) shows that three of the main resonances have much higher intensity (marked with dots in Figure 3a). Since ketene 7 is a reactive compound we assume that it will react with protonated DIPEA 8 and form acetyl N,N-diisopropylethylammonium ion 9. With the peaks corresponding to the resonances of acetyl chloride and ketene already identified, we assign the third peak to the acetyl group of the acetyl ammonium ion (AA4). Interestingly, we also observe diketene 10 as a side product of the reaction.

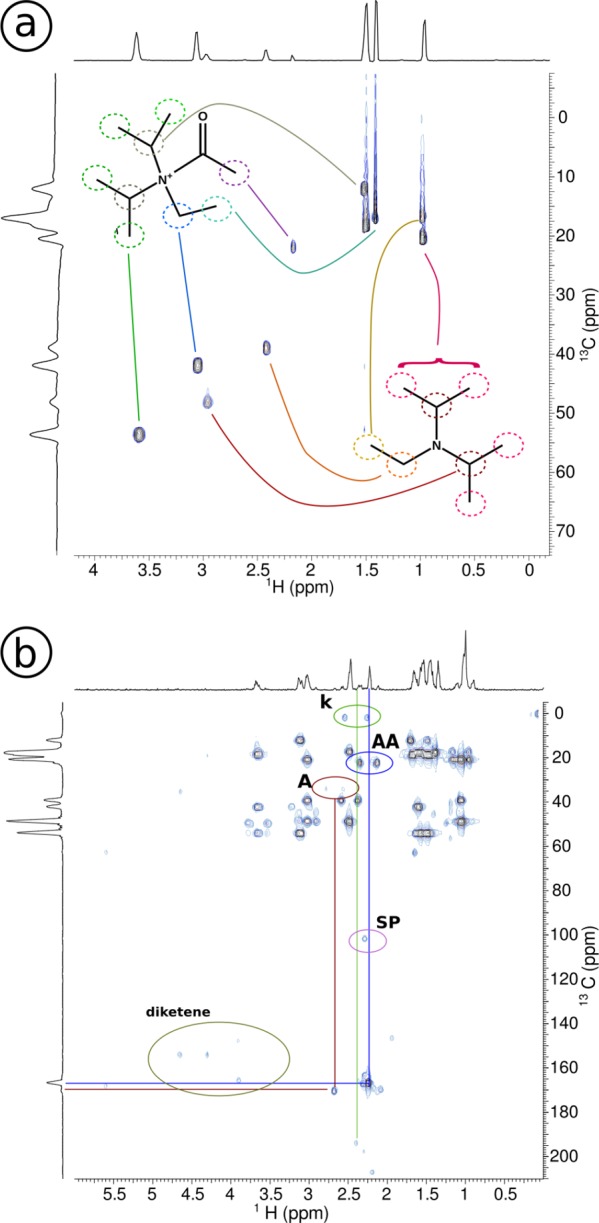

To verify that the peaks at 2.5 and 194 ppm in the conventional 13C NMR spectra in Figure 3a indeed belong to ketene 7, and to determine which peak in the proton spectrum corresponds to ketene, a heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC) spectrum is acquired (Figure 4b). It is clear from the connection between the 2.5 and 194 ppm 13C peaks to the 2.4 ppm 1H peak, that the ketene protons resonate at 2.4 ppm peak in the proton spectrum.

Figure 4.

Acetyl chloride with DIPEA: conventional 2D spectra after 2 h reaction time: (a) HSQC, (b) HMBC. The HSQC shows the separation of the DIPEA 5 and acetyl ammonium ion 9 peaks in the 13C spectrum. In the HMBC, other than multiple peaks from DIPEA 5 and acetyl ammonium 9, we observe ketene 7 (k) at 2.4 ppm in 1H spectrum and at 2.5 and 194 ppm in the 13C spectrum. Furthermore, acetyl chloride 1 (A), the acetyl group of the acetyl ammonium ion 9 (AA), side products (SP), and diketene 10 are found.

Figure 3b shows the proton spectra for reactions of DIPEA with the natural abundance and the 13C labeled acetyl chloride. For the 13C labeled acetyl chloride, the peaks in the spectra that belong to the 13C labeled compound are split due to the JCH coupling. This splitting can be observed for the resonances at 2.69, 2.4, and 2.23 ppm, in agreement with the previous findings. In addition, some low intensity peaks at 6, 2.30, and 2.27 ppm (too small to be marked in the 13C labeled spectrum) exhibiting JCH couplings are observed. For acetyl chloride a JCH coupling of 133 Hz is perceived, for ketene 177 Hz and for the acetyl ammonium ion the JCH coupling is 131 Hz.

The acetyl-N,N-diisopropylethylammonium ion 9 has a hindered rotation around the N-CO bond, therefore the protons 1a are inequivalent and show a split resonance.70,71 When the initial (fast) part of the reaction is completed, the acetyl ammonium ion peaks are split as can be seen in Figure 3. This is also observed in the series of spectra in Figure 2 (at 5 min reaction time and the first conventional NMR spectrum). The protons from the acetyl group of the acetyl ammonium ion, marked 1a and 1b in Figure 3, are found as two doublets with 51 Hz splitting with a 1:1 ratio (1a and 1a′) and one triplet (1b) partly overlapping with the doublet. The other acetyl ammonium peaks (2 and 3) exhibit a 4.2 Hz splitting. The observed chemical shift difference between the cis–trans isomers, due to hindered rotation around the N-CO bond, confirms the presence of acetyl ammonium ion as an intermediate.

As can be observed in the bottom spectrum in Figure 2, the DIPEA peaks broaden again after 2 days. Since the acetyl ammonium ion 9 is not stable this is not unexpected. Upon dissociation of the acetyl moiety, it may form side products and protonated DIPEA 8 which, due to exchange with the acetyl ammonium ion 9, will broaden the peaks.

Since both acetyl ammonium ion 9 and ketene 7 are unstable compounds, side products are formed during the reaction. Diketene 10 is identified by its resonances at 4.88, 4.53, and 3.93 ppm. Furthermore, a product with resonances at 2.27, 2.3, and 6 ppm is observed. This may be a product of (instable) ketene and/or diketene, since both disappeared while this product appears. Some minor products at 1.97 and 2.05 ppm that are present in all of the reactions are observed as well. The peak at 2.05 ppm might be from acetic acid, which can be formed from acetyl chloride and has approximately this chemical shift. Table S1 in the Supporting Information gives an overview of the main peaks that were found in the spectra.

Considering the observed intermediates, acetyl ammonium ion and ketene, several reaction steps can be envisioned. Acetyl chloride 1 and DIPEA 5 were shown to react, forming either ketene 7 and protonated DIPEA 8 or acetyl ammonium 9. An explanation for this could be that the reaction proceeds via an unstable tetrahedral intermediate 6, which results from addition of the amine to the carbonyl group. The proposed reaction mechanism is shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Proposed reaction mechanism of acetyl chloride 1 and DIPEA 5.

The reaction proceeds via tetrahedral intermediate 6, which gives either ketene 7 and protonated DIPEA 8 or acetyl-N,N-diisopropylethylammonium ion 9. Diketene 10 is a side product.

Reaction Mechanism

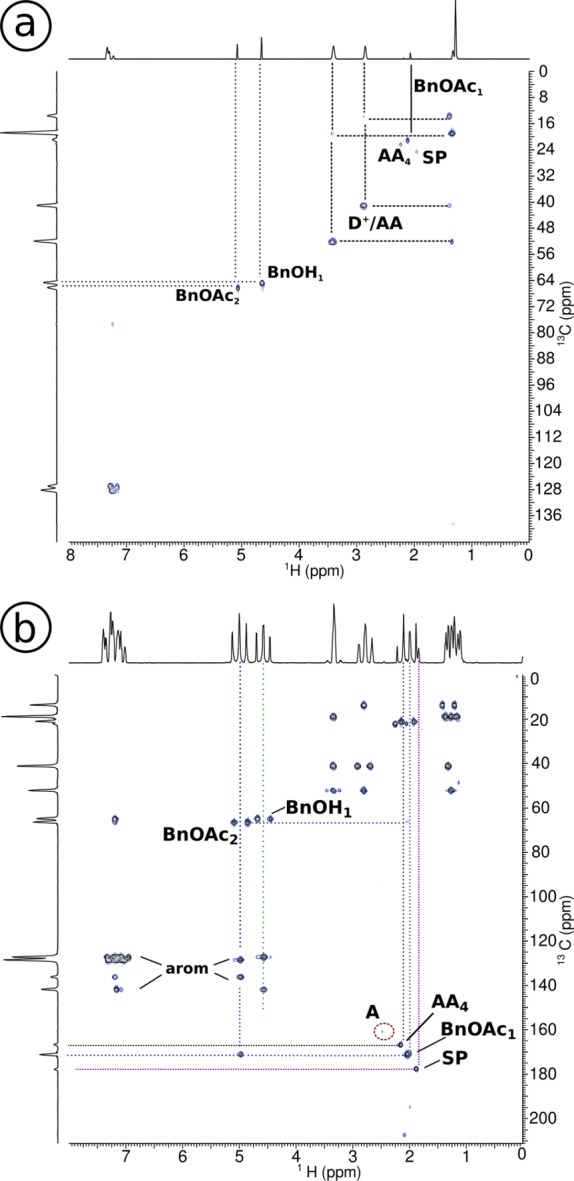

As ketene 7 and acetyl ammonium 9 are products in the reaction of acetyl chloride 1 with DIPEA 5, it is very likely that they are also present in the first minutes of the DIPEA catalyzed acetylation of benzyl alcohol. Small quantities of ketene 7 are indeed observed in the stripline NMR spectra shown in Figure 1. During the reaction, the DIPEA peaks are broadened and shifted to lower field. The acetyl group of the acetyl ammonium ion 9 appears at the start of the reaction and remains present throughout the progressing reaction. At the end of the reaction, acetyl ammonium is identified by the slightly broadened and shifted multiplets in the conventional NMR spectrum (bottom trace of Figure 1). As discussed before, the broadening indicates an exchange process, suggesting the presence of protonated DIPEA 8. The 2D NMR spectra in Figure 5 show the correlations between the 1H NMR and the 13C chemical shifts. The peaks of the acetyl group of acetyl ammonium ion are found at the same chemical shift position as in the reaction with DIPEA; see Table S1 in the Supporting Information, which confirms that the acetyl ammonium ion 9 is a reaction product.

Figure 5.

Acetyl chloride 1 and benzyl alcohol 2 with DIPEA 5: conventional 2D spectra after 2 h reaction time, a) HSQC, b) HMBC. The HSQC shows the direct correlation between 1H and 13C peaks for benzyl acetate 4 (BnOAc), benzyl alcohol 2 (BnOH), protonated DIPEA 8 or acetyl ammonium ion 9 (D+/AA) and its acetyl group (AA4). In the HMBC we find the correlated peaks of the benzyl acetate 4 (BnOAc), benzyl alcohol 2 (BnOH) and their peaks in the aromatic region, acetyl chloride 1 (A), and side products.

The observed reaction products and the protonation of DIPEA suggests that the increased reaction rate of the acetylation in the presence of DIPEA is induced by the reaction of benzyl alcohol with ketene and acetyl ammonium. Since these products were found in the reaction of acetyl chloride and DIPEA as well, the proposed reaction mechanism for the acetylation of benzyl alcohol in the presence of DIPEA is an extension of Scheme 2. Benzyl alcohol may react with either ketene and/or the acetyl ammonium ion, forming benzyl acetate. This gives credibility to the reaction mechanism as shown in Scheme 1.

Kinetics

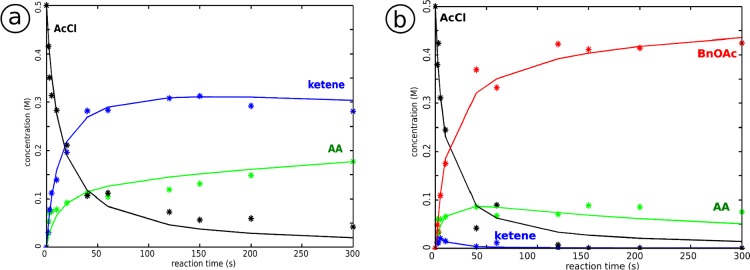

The proposed reaction schemes are explored further using a fitting procedure to a kinetic model described in the Supporting Information. Considering the large number of reaction constants (seven for the full reaction) in relation to the limited number of experimental points we do not claim that we can fully characterize the kinetics with this approach. Nevertheless, the analysis is useful to determine the relative importance of the various steps in the reaction. Based on the integrated intensities of the resonances, the concentrations of the reaction products during the reaction progress are calculated, as shown in Figure 6. A set of differential equations representing the reaction scheme (eq 2 in the Supporting Information) is solved while varying the k values to minimize the difference between experimental and fitted values via an object function F,72 for the concentrations of acetyl chloride 1, ketene 7, and the acetyl group of the acetyl ammonium ion 9.

Figure 6.

Modeling of the kinetics of the acetylation of benzyl alcohol: (a) reaction of acetyl chloride with DIPEA and (b) reaction of acetyl chloride with benzyl alcohol in the presence of DIPEA. Experimentally derived values of concentrations in the mixture during the reaction are marked with *, the solid line is the result of the fit. Starting product acetyl chloride 1 (AcCl), intermediates ketene 7 and acetyl ammonium ion 9 (AA), and end poduct benzyl acetate 4 (BnOAc). The concentrations have been estimated by the relative deconvoluted areas of the peaks.

For the reaction of acetyl chloride and DIPEA, the reaction scheme shown in Scheme 2 gives the best fit to the data, compared to a similar reaction mechanism without an intermediate and/or different equilibria. Thus, we postulate that the tetrahedral intermediate 6 is formed in the first step of the reaction acetyl chloride and DIPEA. Comparing the backward and forward reactions, k–1 is much smaller than k1, and so, the backward reaction is assumed to be negligible. Since the concentration of the tetrahedral intermediate 6 is very small in the model, the backward reaction can not be accurately fit and k–1 is set to zero. The tetrahedral intermediate 6 disintegrates forming ketene 7 with protonated DIPEA 8 (k2) or the acetyl ammonium ion 9 (k3). These are the fastest steps in the reaction mechanism; the values of k2 and k3 are much larger than all other reaction constants so the corresponding reactions can be considered instantaneous. For this reason, the relative ratio between k2 and k3 (2.4 ± 0.5) is more relevant than their absolute values. Likewise the ratio of the (much smaller) equilibrium constants of the reactions between ketene 7 and DIPEA 5 with acetyl ammonium ion 9 (K = k4/k–4 = 1.7 ± 0.5) can be determined more accurately than the absolute value of the individual rates.

After optimization we find the k values: k1 = 0.16(±0.03) M–1 s–1, k2 = 12 s–1, k3 = 5 s–1, k4 = 0.0035(±0.002) M–1 s–1, and k–4 = 0.0020(±0.002) M–1 s–1. The error margin given for the reaction constants reflects the influence on the accuracy of the model. One of the reaction constants is changed, while the other k-values remain at their optimal value. The relative effect of such a change in k-values on the fit result is different for each reaction constant. The given amount of deviation of the k-value will decrease the object function72 of the fit (summed squared residuals) with 5%. The values of k2 and k3 can be set much larger, which slightly improves the fit, as long as the ratio remains 2.4; however, the calculation slows down when these k values are set too high. The resulting k values suggest that the tetrahedral intermediate 4 is indeed very unstable and breaks down into ketene 7 and protonated DIPEA 8 and acetyl ammonium ion 9, with a preference for the ketene route. Some exchange between ketene and protonated DIPEA with acetyl ammonium ion is possible, favoring acetyl ammonium ion, which is the end product at the longest reaction times that we used in the microfluidic stripline setup. We conclude from the broadening for very long reaction times that the acetyl ammonium ion 9 partly dissociates, leaving protonated DIPEA 8 and some side products. This slower process has not been included in the reaction scheme modeling.

The proposed reaction mechanism of the complete acetylation of benzyl alcohol (Scheme 1) is modeled next. The reaction of DIPEA and acetyl chloride results in ketene 7 and protonated DIPEA 8 and acetyl ammonium ion 9. Benzyl alcohol 2 may react with ketene 7 or with acetyl ammonium ion 9, forming benzyl acetate 4. The direct reaction of benzyl alcohol and acetyl chloride is not taken into account because it is much slower (hours) relative to the reaction times we studied in-line (seconds to minutes).

Analogous to the reaction of acetyl chloride with DIPEA, the first reaction step is the formation of the tetrahedral intermediate 6, in which the forward reaction rate is much higher than the backward reaction rate; so, again k–1 was assumed to be negligible and set to zero. Also as before, the ratio of k2 and k3, in which the tetrahedral intermediate 6 breaks down into ketene 7 and protonated DIPEA 8 or acetyl ammonium ion 9, can be determined more accurately than the actual values. For the ratio between k2 and k3, the best fit is found for the value k2/k3 = 2.7(±0.3), thus favoring ketene and protonated DIPEA formation. Since the concentration of ketene is very small, k4 does not critically influence the outcome of the model, as long as it is very small and k4 is therefore set to zero.

Seven k values as indicated in Scheme 1 are thus needed for representation of the reaction with a set of differential equations (eq 3 in Supporting Information), which is optimized with respect to the concentrations of acetyl chloride 1, ketene 7, the acetyl group of acetyl ammonium ion 9, and benzyl acetate 4. The optimized k values that were found are k1 = 0.23(±0.05) M–1 s–1, k2 = 3 s–1, k3 = 1 s–1, k4 = 0 M–1 s–1, k–4 = 0.04(±0.2) s–1, k5 = 2.6(±1.3) M–1 s–1, and k6 = 0.030(±0.003)M–1 s–1. The given error margin, as before, decreases the variance of the fit with approximately 5%, reflecting the influence of the fit parameter on the accuracy of the model.

Interestingly, k5 is found to be much larger than k6, which suggests that the formation of benzyl acetate 4 via the reaction of benzyl alcohol 2 with ketene 7 is the fastest. After 5 min reaction time the conversion of benzyl alcohol 2 into benzyl acetate 4 is approximately 56%. The fast part of the reaction is finished by then since there is no ketene 7 and acetyl chloride 1 left in the mixture. If left to stand for 2 days, the acetyl ammonium 9 peak diminishes and benzyl acetate 4 increases slightly, which indicates that the reaction proceeds slowly via the acetyl ammonium route (reaction k6 in Scheme 1). The high reactivity/instability of both ketene 7 and acetyl ammonium 9 prevents the achievement of full conversion as witnessed by the formation of diketene 10 and protonated DIPEA 8 leading to various side products.

Variation of Amines as Base Catalyst

Having established the role of DIPEA in the acetylation of benzyl alcohol we set out to study different types of amines as catalysts to examine whether the reaction proceeds via a similar mechanism. DIPEA, triethylamine 11 (TEA), and pyridine 15 differ in reactivity; pyridine is a weakly aromatic base (acid dissociation constant pKa ≈ 5.2), TEA and DIPEA have, due to increasing steric hindrance, a reduced nucleophilicity and a higher base reactivity (pKa ≈ 10.6 and pKa ≈ 11.4, respectively).73 The proton affinity of DIPEA is highest (984 kJ/mol), that of TEA slightly lower (972 kJ/mol), and that of pyridine lowest (924 kJ/mol).74 With the high proton affinity, the DIPEA molecule was postulated to act as a proton scavenger while not taking part in the reaction, due to steric hindrance, contrary to the findings in the previous section. Pyridine, having lower proton affinity but little steric effects, would instead be acetylated rather than protonated.

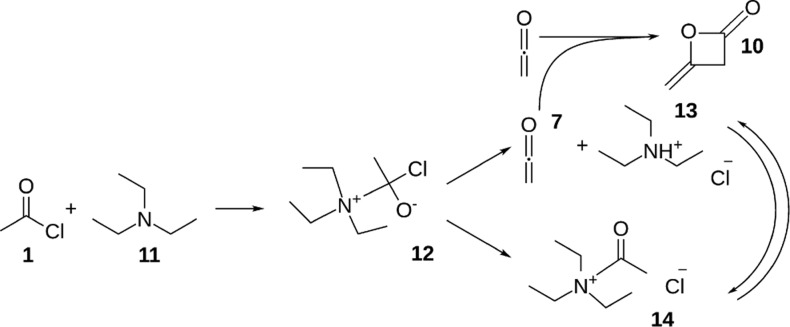

Triethylamine

Figure S3 in the Supporting Information shows a series of stripline NMR spectra, and Figure S4 shows the conventional 2D NMR spectra for the reaction of acetyl chloride (0.5 M) and TEA (0.5 M). Peaks of intermediate products, ketene 7, and the acetyl group of acetyl ammonium ion 14 are found at the same positions as in the reaction with DIPEA. This suggests that similar products are involved with the proposed reaction mechanism shown in Scheme 3. However, the reaction kinetics are markedly different. The first step of acetyl chloride reacting with TEA is much faster as compared to DIPEA. Ketene 7 and deketene 10 form at a much higher rate, being already visible within 1.5 s in the spectra taken with the stripline probe. With the highly reactive ketene 7 and diketene 10 being formed at high rate, we observe the formation of more side products, which can be seen in the conventional 2D spectra in Figure S4.

Scheme 3. Proposed Reaction Mechanism of Acetyl chloride 1 and Triethylamine 11.

A tetrahedral intermediate 12 is formed, which breaks down into ketene 7 and protonated TEA 13 or acetyl ammonium ion 14. Diketene 10 is a side product.

In Figure S5, a series of in situ spectra for the acetylation of benzyl alcohol in the presence of TEA is shown, and Figure S6 shows the conventional 2D NMR spectra at later stages in this reaction. In these spectra, benzyl acetate 4 and acetyl ammonium ion 14 are observed with a small amount of acetic acid as a side product. Much less side products are observed, compared to the spectra of acetyl chloride and TEA. With the rapid formation of ketene that is available for reaction with benzyl alcohol to form benzyl acetate, the reaction is completed within 30 s, and the overall conversion is 57% after 5 min reaction time.

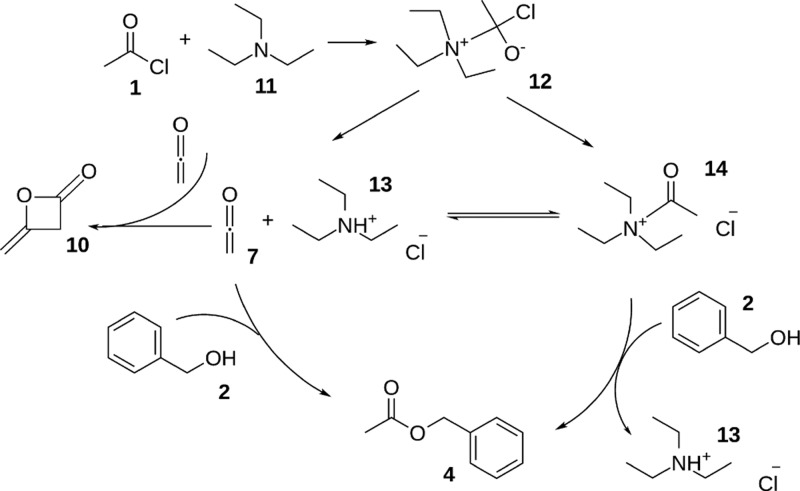

From the NMR analyses, we conclude that the TEA-catalyzed acetylation proceeds similarly to the acetylation in the presence of DIPEA, as summarized in Scheme 4. Despite TEA being a somewhat weaker base, the reaction rates are higher than in the reaction with DIPEA. This further corroborates that the amine is not merely a proton scavenger but takes part in the reaction, leading to the formation of ketene, where steric factors are more important than basicity.

Scheme 4. Proposed Reaction Mechanism of Acetyl Chloride 1 and Triethylamine 11 with Benzyl Alcohol 2.

First, acetyl chloride and TEA form a tetrahedral intermediate 12, from which an equilibrium between acetyl ammonium ion 14 and ketene 7 forms with protonated TEA 13. Benzyl alcohol 2 reacts with ketene 7 or acetyl ammonium ion 14 into benzyl acetate 4.

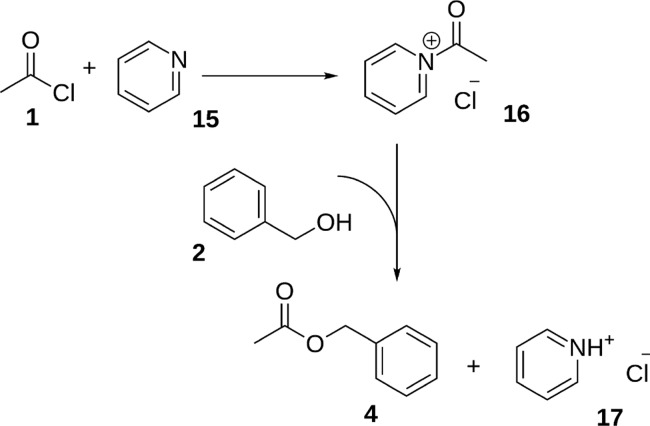

Pyridine

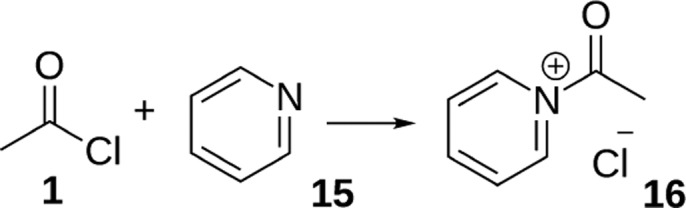

Despite the fact that pyridine 15 is regularly used as base catalyst in similar reactions, it is a very different base. From the literature,75,76 we expect an acetyl pyridinium ion 16 to play an important role in this reaction, similar to the acetyl ammonium ion that we observed in the preceding reactions.

Figure S7 in the Supporting Information shows the results of the in situ experiments in the stripline probe using pyridine as a base catalyst. Figure S8 shows the conventional 2D NMR spectra. In these spectra, a methyl peak at 2.22 ppm is observed at a similar position as the acetyl ammonium ion 9. Furthermore, during the reaction, the pyridine peaks are found to shift and broaden suggesting the formation of a complex. Based on this we conclude that the predicted acetyl pyridinium ion 16 is indeed formed, in agreement with literature.75,76 Ketene 7 is not observed at any point of this reaction. We conclude that acetyl chloride 1 and pyridine 15 directly react to give acetyl pyridinium ion 16 as shown in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5. Proposed Reaction Mechanism of Acetyl Chloride 1 and Pyridine 15, Giving Acetyl Pyridinium Ion 16.

The spectra for the pyridine (0.5 M) catalyzed reaction of benzyl alcohol (0.5 M) with acetyl chloride (0.5 M) are shown in Figure S9, with the conventional 2D NMR spectra at a later stage of the reaction displayed in Figure S10 of the Supporting Information. In these spectra, a methyl peak at 2.22 ppm and a broadening and shift of the pyridine peaks are observed as before, suggesting the presence of acetyl pyridinium ion 16. Already after 1.5 s (top spectrum in Figure S9), acetyl chloride 1 has almost completely reacted into benzyl acetate 4 and acetylpyridinium 16. Furthermore, benzyl alchohol 2 and some side product formation, probably acetic acid, is observed. This corroborates that the acetylation takes place via the reaction of benzyl alcohol with the acetyl pyridinium ion 16 intermediate as depicted in Scheme 6. The reaction rates are much faster compared to the reaction performed with DIPEA. The overall conversion of benzyl alcohol to benzyl acetate is similar, however, being 55% after 5 min.

Scheme 6. Proposed Reaction Mechanism of Acetyl Chloride 1 and Pyridine 15 with Benzyl Alchohol 2, via Acetyl Pyridinium 16, Forming Benzyl Acetate 4 and Protonated Pyridine 17.

Conclusion

In the work presented here we show that a microfluidic stripline NMR setup offers the possibility to study fast reactions in situ. Microreactor technology is advantageous for very fast and/or exothermic reactions. The acetylation of benzyl alcohol in the presence of DIPEA was studied in detail, and intermediates of the reaction were identified as ketene and acetyl ammonium ion. The kinetics of this reaction were monitored and modeled by solving the rate equations for the proposed reaction scheme. Based on these results, a reaction mechanism via a tetrahedral intermediate was proposed. It was found that the product is formed most rapidly by the reaction of benzyl alcohol with ketene. Replacing DIPEA with TEA accelerates the reaction, but the mechanism remains similar, as suggested by the observation of the same intermediates, ketene and acetyl ammonium. Using pyridine as a base catalyst, no evidence is found that this reaction also proceeds via ketene, but acetyl pyridinium ion 16 was observed.

Acknowledgments

Ruud Aspers is acknowledged for acquiring the conventional NMR spectra. This work was financially supported by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), ACTS, Process on a Chip programme.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b00039.

Technical details of the stripline NMR chips, probe design, microfluidics. Description of the fitting procedure for the kinetics and PDEs. Spectra and reaction mechanism of the acetylation of benzyl alcohol without the presence of a base catalyst. Stripline NMR spectra and conventional 2D NMR spectra (HSQC and HMBC) of the reactions of acetyl chloride with/without benzyl alcohol and base catalysts TEA and pyridine. Table giving an overview of the observed peaks in stripline and conventional NMR experiments (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Nouryon, Expert Capability Group Process Technology, Research Development & Innovation, Zutphenseweg 10, 7418 AJ Deventer, The Netherlands.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Eisert R.; Levsen K. Solid-phase microextraction coupled to gas chromatography: a new method for the analysis of organics in water. J. Chromatogr. A 1996, 733, 143. 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00875-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gur'eva L. L.; Tkachuk A. I.; Dzhavadyan E. A.; Estrin G. A.; Surkov N. F.; Sulimenkov I. V.; Rozenberg B. A. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Anionic Polymerization of Acrylamide Monomers. Polym. Sci., Ser. A 2007, 49, 987. 10.1134/S0965545X07090052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. S.; Jensen K. F. Automated Multitrajectory Method for Reaction Optimization in a Microfluidic System using Online IR Analysis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012, 16, 1409. 10.1021/op300099x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puri J. K.; Singh R.; Chahal V. K.; Sharma R. P.; Wagler J.; Kroke E. New silatranes possessing urea functionality: Synthesis, characterization and their structural aspects. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1341. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.12.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie J. S.; Donarski J. A.; Wilson J. C.; Charlton A. J. Analysis of complex mixtures using high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and chemometrics. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2011, 59, 336. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J.; Hilmersson G.; Santamaria J.; Rebek J. Jr. Diels-Alder Reactions through Reversible Encapsulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 3650. 10.1021/ja973898+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babailov S. P. NMR studies of photo-induced chemical exchange. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2009, 54, 183. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2008.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson M. D.; Tan E. H. P.; Landis C. R. Stopped-Flow NMR: Determining the Kinetics of [rac-(C2H4(1-indenyl)2)ZrMe][MeB(C6F5)3]-Catalyzed Polymerization of 1-Hexene by Direct Observation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11461. 10.1021/ja105107y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Jiang X. Why microfluidics? Merits and trends in chemical synthesis. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 3960. 10.1039/C7LC00627F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutschack M. B.; Pieber B.; Gilmore K.; Seeberger P. H. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11796. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu D. T.; deMello A. J.; Carlo D. D.; Doyle P. S.; Hansen C.; Maceiczyk R. M.; Wootton R. C. Small but Perfectly Formed? Successes, Challenges, and Opportunities for Microfluidics in the Chemical and Biological Sciences. Chem. 2017, 2, 201. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jähnisch K.; Hessel V.; Löwe H.; Baerns M. Chemistry in Microstructured Reactors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 406. 10.1002/anie.200300577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts P.; Wiles C. Recent advances in synthetic micro reaction technology. Chem. Commun. 2007, 443. 10.1039/B609428G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander U.; Jensen K. F. Olefin Autoxidation in Flow. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 601. 10.1021/ie402736j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amii H.; Nagaki A.; Yoshida J. Flow microreactor synthesis in organo-fluorine chemistry. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2793. 10.3762/bjoc.9.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantillo D.; Damm M.; Dallinger D.; Bauser M.; Berger M.; Kappe C. O. Sequential Nitration/Hydrogenation Protocol for the Synthesis of Triaminophloroglucinol: Safe Generation and Use of an Explosive Intermediate under Continuous-Flow Conditions. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 1360. 10.1021/op5001435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida J.; Nagaki A.; Iwasaki T.; Suga S. Enhancement of Chemical Selectivity by Microreactors. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2005, 28, 259. 10.1002/ceat.200407127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratner D. M.; Murphy E. R.; Jhunjhunwala M.; Snyder D. A.; Jensen K. F.; Seeberger P. H. Microreactor-based reaction optimization in organic chemistry - glycosylation as a challenge. Chem. Commun. 2005, 578. 10.1039/B414503H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delville M. M. E.; Nieuwland P. J.; Janssen P.; Koch K.; van Hest J. C. M.; Rutjes F. P. J. T. Continuous flow azide formation: Optimization and scale-up. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 167, 556. 10.1016/j.cej.2010.08.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J.; Schouten J. C.; Nijhuis T. A. Integration of Microreactors with Spectroscopic Detection for Online Reaction Monitoring and Catalyst Characterization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 14583. 10.1021/ie301258j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sans V.; Cronin L. Towards dial-a-molecule by integrating continuous flow, analytics and self-optimization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2032. 10.1039/C5CS00793C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belder D. Integrating chemical synthesis and analysis on a chip. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 385, 416. 10.1007/s00216-006-0428-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoult D.; Richards R. The Signal-to-Noise ratio of the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Experiment. J. Magn. Reson. 1976, 24, 71. 10.1016/0022-2364(76)90233-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey M. E.; Subramanian R.; Olson D. L.; Webb A. G.; Sweedler J. V. High-Resolution NMR Spectroscopy of Sample Volumes from 1 nL to 10 μL. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 3133. 10.1021/cr980140f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentgens A. P. M.; Bart J.; van Bentum P. J. M.; Brinkmann A.; van Eck E. R. H.; Gardeniers J. G. E.; Janssen J. W. G.; Knijn P.; Vasa S.; Verkuijlen M. H. W. High-resolution liquid- and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance of nanoliter sample volumes using microcoil detectors. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 052202. 10.1063/1.2833560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratila R. M.; Velders A. H. Small-Volume Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2011, 4, 227. 10.1146/annurev-anchem-061010-114024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gökay O.; Albert K. From single to multiple microcoil flow probe NMR and related capillary techniques: a review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 647. 10.1007/s00216-011-5419-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalesskiy S. S.; Danieli E.; Blümich B.; Ananikov V. P. Miniaturization of NMR Systems: Desktop Spectrometers, Microcoil Spectroscopy, and NMR on a Chip for Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Industry. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5641. 10.1021/cr400063g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnia B.; Webb A. G. Limited-Sample NMR Using Solenoidal Microcoils, Perfluorocarbon Plugs, and Capillary Spinning. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 5326. 10.1021/ac9808371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D. L.; Peck T. L.; Webb A. G.; Magin R. L.; Sweedler J. V. High Resolution Microcoil 1H-NMR for Mass-Limited, Nanoliter-Volume Samples. Science 1995, 270, 1967. 10.1126/science.270.5244.1967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier R. C.; Höfflin J.; Badilita V.; Wallrabe U.; Korvink J. G. Microfluidic integration of wirebonded microcoils for on-chip applications in nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2014, 24, 045021. 10.1088/0960-1317/24/4/045021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leidich S.; Braun M.; Gessner T.; Riemer T. Silicon Cylinder Spiral Coil for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of Nanoliter Samples. Concepts Magn. Reson., Part B 2009, 35B, 11. 10.1002/cmr.b.20131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan H.; Song S.-H.; Zaß A.; Korvink J.; Utz M. Contactless NMR Spectroscopy on a Chip. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 3696. 10.1021/ac300204z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratila R. M.; Gomez V.; Sýkora S.; Velders A. H. Multinuclear nanoliter one-dimensional and two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy with a single non-resonant microcoil. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3025. 10.1038/ncomms4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swyer I.; Soong R.; Dryden M. D. M.; Fey M.; Maas W. E.; Simpson A.; Wheeler A. R. Interfacing digital microfluidics with high-field nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 4424. 10.1039/C6LC01073C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bentum P. J. M.; Janssen J. W. G.; Kentgens A. P. M. Towards nuclear magnetic resonance m-spectroscopy and μ-imaging. Analyst 2004, 129, 793. 10.1039/B404497P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bentum P. J. M.; Janssen J. W. G.; Kentgens A. P. M.; Bart J.; Gardeniers J. G. E. Stripline probes for nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Magn. Reson. 2007, 189, 104. 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart J.; Janssen J. W. G.; van Bentum P. J. M.; Kentgens A. P. M.; Gardeniers J. G. E. Optimization of stripline-based microfluidic chips for high-resolution NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2009, 201, 175. 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krojanski H. G.; Lambert J.; Gerikalan Y.; Suter D.; Hergenroder R. Microslot NMR Probe for Metabolomics Studies. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 8668. 10.1021/ac801636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire Y.; Chuang I. L.; Zhang S.; Gershenfeld N. Ultra-small-sample molecular structure detection using microslot waveguide nuclear spin resonance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 9198. 10.1073/pnas.0703001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch G.; Yilmaz A.; Utz M. An optimized detector for in-situ high-resolution NMR in microfluidic devices. J. Magn. Reson. 2016, 262, 73. 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Mehta H. S.; Butler M. C.; Walter E. D.; Reardon P. N.; Renslow R. S.; Mueller K. T.; Washton N. M. High-resolution microstrip NMR detectors for subnanoliter samples. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 28163. 10.1039/C7CP03933F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorte E. G.; Banek N. A.; Wagner M. J.; Alam T. M.; Tong Y. J. In Situ Stripline Electrochemical NMR for Batteries. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 2336. 10.1002/celc.201800434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bart J.; Kolkman A. J.; Oosthoek-de Vries A. J.; Koch K.; Nieuwland P. J.; Janssen J. W. G.; van Bentum P. J. M.; Ampt K. A. M.; Rutjes F. P. J. T.; Wijmenga S. S.; Gardeniers J. G. E.; Kentgens A. P. M. A Microfluidic High-Resolution NMR Flow Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5014. 10.1021/ja900389x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M. V.; de la Hoz A. NMR reaction monitoring in flow synthesis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 285. 10.3762/bjoc.13.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu L.; Jayawickrama D. A.; Zhang X.; Webb A. G.; Sweedler J. V. Measuring Reaction Kinetics by Using Multiple Microcoil NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 4669. 10.1002/anie.200351901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensink H.; Benito-Lopez F.; Hermes D. C.; Verboom W.; Gardeniers J. G. E.; Reinhoudt D. N.; van den Berg A. Measuring reaction kinetics in a lab-on-a-chip by microcoil NMR. Lab Chip 2005, 5, 280. 10.1039/b414832k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuta M.; Jayawickrama D. A.; Wolters A. M.; Manz A.; Sweedler J. V. Micromixer-Based Time-Resolved NMR: Applications to Ubiquitin Protein Conformation. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 956. 10.1021/ac026076q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brächer A.; Hoch S.; Albert K.; Kost H. J.; Werner B.; von Harbou E.; Hasse H. Thermostatted micro-reactor NMR probe head for monitoring fast reactions. J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 242, 155. 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M. V.; Rodriguez A. M.; de la Hoz A.; Jimenez-Marquez F.; Fratila R. M.; Barneveld P. A.; Velders A. H. Determination of Kinetic Parameters within a Single Nonisothermal On-Flow Experiment by Nanoliter NMR Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 10547. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K.; Kurihara H.; Yamamoto H. An Extremely Simple, Convenient, and Selective Method for Acetylating Primary Alcohols in the Presence of Secondary Alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 3791. 10.1021/jo00067a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard P.; Brittain W. J. Mechanism of Amine-Catalyzed Ester Formation from an Acid Chloride and Alcohol. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 677. 10.1021/jo9716643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull D. H.; Weatherwax A.; Lectka T. Catalytic, asymmetric reactions of ketenes and ketene enolates. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6771. 10.1016/j.tet.2009.05.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosthoek - de Vries A. J.; Bart J.; Tiggelaar R. M.; Janssen J. W. G.; van Bentum P. J. M.; Gardeniers J. G. E.; Kentgens A. P. M. Continuous flow 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy in microfluidic stripline NMR chips. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2296. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy K. D.; Shen D.; Jamison T.; Jensen K. Mixing and Dispersion in Small-Scale Flow Systems. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012, 16, 976. 10.1021/op200349f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laude D. A.; Wilkins C. L. Direct-Linked Analytical Scale High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1984, 56, 2471. 10.1021/ac00277a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N.; Webb A.; Peck T. L.; Sweedler J. V. On-line NMR Detection of Amino Acids and Peptides in Microbore LC. Anal. Chem. 1995, 67, 3101. 10.1021/ac00114a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühne R. O.; Schaffhauser T.; Wokaun A.; Ernst R. R. Study of transient chemical reactions by NMR. Fast stopped-flow fourier transform experiments. J. Magn. Reson. 1979, 35, 39. 10.1016/0022-2364(79)90077-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malz F.; Jancke H. Validation of quantitative NMR. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005, 38, 813. 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann T.; Mleczko L. Heat Management in Microreactors for Fast Exothermic Organic Syntheses - First Design Principles. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20, 487. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhausen G.; Ruben D. Natural abundance nitrogen-15 NMR by enhanced heteronuclear spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1980, 69, 185. 10.1016/0009-2614(80)80041-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bax A.; Summers M. 1H and 13C assignments from selectivity-enhanced detection of heteronuclear multiple-bond connectivity by 2D multiple quantum NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 2093. 10.1021/ja00268a061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek J. D. matNMR: A flexible toolbox for processing, analyzing and visualizing magnetic resonance data in Matlab. J. Magn. Reson. 2007, 187, 19. 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACD/NMR Processor Academic Edition; Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Satchell D. P. N.; Satchell R. S. Acylation by ketens and isocyanates. A mechanistic approach. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1975, 4, 231. 10.1039/cs9750400231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino E. C.; Brittain W. J. Kinetics of Acyl ammonium salt formation: mechanistic implications for carbonate macrocyclization. Macromolecules 1992, 25, 3827. 10.1021/ma00040a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taggi A. E.; Hafez A. M.; Wack H.; Young B.; Drudy W. J. III; Letcka T. Catalytic, Asymmetric synthesis of β-Lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7831. 10.1021/ja001754g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandström J.Dynamic NMR Spectroscopy; Academic Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Seikaly H. R.; Tidwell T. T. Addition reactions of ketenes. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 2587. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90545-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drakenberg T.; Dahlqvist K.-J.; Forsen S. The barrier to internal rotation in amides. IV. N,N-Dimethylamides; substituent and solvent effects. J. Phys. Chem. 1972, 76, 2178. 10.1021/j100659a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparro F. P.; Kolodny N. H. NMR determination of the rotational barrier in N,N-dimethylacetamide. J. Chem. Educ. 1977, 54, 258. 10.1021/ed054p258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seoud A.-L.; Abdallah L. A. M. Two Optimization Methods to Determine the Rate Constants of a Complex Chemical Reaction Using FORTRAN and MATLAB. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 7, 509. 10.3844/ajassp.2010.509.517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koutentis P. A.; Koyioni M.; Michaelidou S. S. Synthesis of [(4-Chloro-5H-1,2,3-dithiazol-5-ylidene)amino]azines. Molecules 2011, 16, 8992. 10.3390/molecules16118992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lias S. G.; Liebman J. F.; Levin R. D. Evaluated gas phase basicities and proton affinities of molecules; heats of formation of protonated molecules. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1984, 13, 695. 10.1063/1.555719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht A. R.; Jencks W. P. The acetylpyridinium ion intermediate in pyridine-catalyzed hydrolysis and acyl transfer reactions of acetic anhydride. Observation, Kinetics, structure-reactivity correlations, and effects of concentrated salt solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 5432. 10.1021/ja00721a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spanu P.; Mannu A.; Ulgheri F. An unexpected reaction of pyridine with acetyl chloride to give dihydropyridine and piperidine derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 1939. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.