Abstract

Aim. To determine the social, physical, and emotional impact of living with Perthes’ disease on affected children and their family (caregivers). Patients and Methods. Through a mixed methods approach, we interviewed 18 parents and explored the perspectives of 12 children affected by Perthes’ disease (mean = 7.1 years, SD = ±4.1 years) using a survey tool. Thematic analysis of parents’ interviews provided an insight into disease-specific factors influencing patients and family’s daily life activities. Using the childhood survey tool, good and bad day scores were analyzed using MANOVA (multivariate analysis of variance). Results. Thematic analysis of the parent interviews (main themes n = 4) identified a marked effect of the disease on many facets of the child’s life, particularly pain and the impact on sleep, play, and school attendance. In addition, the interviews identified a negative effect on the family life of the parents and siblings. Children indicated that activities of daily living were affected even during “good days” (P < .05), but pain was the key limiting factor. Conclusion. Perthes’ disease negatively affects the social, physical, and emotional well-being of children and their family. These findings provide outcome domains that are important to measure in day-to-day care and add in-depth insight into the challenges caused by this disease for health care professionals involved in clinical management.

Keywords: Perthes’ disease, children, femoral head osteonecrosis, health-related quality of life

Introduction

Perthes’ disease is an idiopathic osteonecrosis of a developing hip,1,2 with the typical onset between 4 and 8 years old, and a predominance in males (4:1 male-female ratio).1,2 The incidence of Perthes’ disease is greatest in white children from North Europe, particularly the Northern Part of the United Kingdom and Norway.3-5 The management of the disease varies between surgical interventions (ie, typically Varus osteotomy or Salter’s osteotomy) and conservative approaches (ie, physiotherapy, bracing, and bed rest).6,7 There is little high-quality evidence pertaining to treatment of Perthes’ disease, and the best treatment options are still under debate.6,7 The main aim of existing treatment is to regulate the collapse of the femoral head through “containment,” and to manage the pain.7-9

Typically the commonly reported outcomes of Perthes’ disease are radiographic, in particular the shape and congruency of the femoral head.7,10 The profound effects that Perthes’ disease has on the lives of affected children and their families has not been explored in the literature. The treatment uncertainties and absence of national or international consensus has a marked effect on increasing the anxiety of families. While child-specific quality of life questionnaires have been used in affected children,11-13 it is unclear if these capture the outcomes that are most important to the children and their family. Moreover, previous studies that have investigated quality of life in children with chronic illness have shown how the disease/condition negatively affects social functions and school attendance, as well as influence parent behavior toward the child.14 No prior study has performed an in-depth investigation to understand the physical, emotional, and social impact on quality of life in children with Perthes’ disease, and the impact that this may have on their family. This information would highlight the importance of well-being of these children and their families to clinicians responsible for diagnosis and treatment of the disease in order to improve the clinical management of the disease inside and outside the hospital care.

Patients and Methods

Participants

We designed a concurrent triangulation mixed methods study, including 18 parents and 12 children (2 girls and 10 boys), with an age range between 4 and 12 years (mean = 7.1 years, SD = ±4.1 years) at the time of the interview (Table 1). We engaged participants from Alder Hey Children’s Hospital Liverpool (UK), between June and August 2017. Participants were patients approached during routine visits, by verbal approach and additional patient information sheet. Inclusion into the study was a diagnosis of Perthes’ disease in the child (irrespective of the current stage of disease or method of treatment), below the age of 16 years, willing to participate in the interview process, and the ability to be conversant in English.

Table 1.

Patients’ Demographic Data.

| Patient Number | Sex | Age (Years) | Parent(s) Interviewed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 9 | Mother and father |

| 2 | Female | 5 | Mother and father |

| 3 | Male | 12 | Mother |

| 4 | Male | 5 | Father |

| 5 | Male | 6 | Mother and father |

| 6 | Male | 5 | Mother |

| 7 | Male | 4 | Mother and father |

| 8 | Male | 8 | Mother |

| 9 | Female | 6 | Mother and father |

| 10 | Male | 12 | Mother |

| 11 | Male | 5 | Mother |

| 12 | Male | 8 | Mother |

| 13a | Male | 5 | Mother |

For this child, only the parent’s interview data are available.

Data Collection

The data collection process included 2 stages: (1) children completed a bespoke questionnaire and (2) parents engaged in a semistructured interview. The questionnaire (see Appendix A) was completed first by the child, followed by the interview with the parent(s) (see Appendix B) in a session that lasted ~30 minutes. The completion of the booklets and parent interviews were conducted in the Orthopaedic Unit of Alder Hey Children’s Hospital Liverpool (UK), following a routine clinical appointment for Perthes’ disease. Informed consent was collected from participants to record the interview.

The questionnaire sought to score different situations of daily life in both good and bad days, which was completed with prompts from the interviewer (as required). The questionnaire contained questions related to social, physical, and emotional impact of Perthes’ disease (such as pain, the impact of the disease on social relationships, and the influences of it on daily life activities). Responses were collected through the use of emoji’s to ensure ease of completion. The questionnaire completion process took no longer than 30 minutes. The questionnaire was designed (AFL and TG) with the help of 2 families affected by Perthes’ disease, to ensure that it was sufficient to extract relevant information. It was specifically designed to be young child friendly, easy, and fun to complete by a young child. Phrasing of particular items were modified as additional data were collected, in order to ease interpretation and provide a clear meaning to the child.

The interviews aimed to explore participants’ experience of the disease and the impact of Perthes’ disease on their lives. The questions investigated areas such as impact of the disease on patients and related family, the importance of clinical management, and the impact of the disease on daily living activities and sport/recreational activities. The interview began with open questions to seek a general picture of the child’s life, obtain information about the current stage of the disease, and determine general information related to the family of the child (such as “Can you tell me when you started to realize that something was going on with your child?” or “Can you tell me some information about your family, such as how many people there are and if he/she has any siblings?”). Then, the interview continued with a series of open-ended questions on their experiences and impact of Perthes’ disease on their everyday life.

The design of more specific and detailed questionnaire and interview for Perthes’ disease aimed to seek a better understanding of the limitations related to this specific condition, which are usually assessed with tools that are not specific for Perthes’ disease (ie, KIDSCREEN-10; EQ-5D-3L; PedsQL 4.0).11-13

Both the children’s questionnaire and the parents’ interview were designed, conducted, and analyzed by members of the team with a background/training in psychology/qualitative research (DGL, RM, AL, and TG).

Children’s Questionnaire Analysis

The questionnaire aimed to capture a general overview of living with Perthes’ disease through the children perspective, and to understand the impact that the disease has on the children’s daily living activities. The main questionnaire’s outcome was the difference in daily life activities and pain between good and bad days.

The “emoji scores” of the children’s questionnaire were analyzed using a quantitative approach (score of 1 was related to the “happiest” emoji and 5 to the “saddest” emoji).

A Shapiro-Wilk test was used to ensure residuals were normally distributed (P > .05) and we found a moderate correlation of the dependent variables with a Pearson correlation test (0.3 < |r | < 0.5). This data were analyzing using a MANOVA (IBM SPSS software, v.22.0) looking for statistical significance (P < .05).

Parents’ Interviews Analysis

The obtained sample size of 18 parents and 12 children was enough to reach saturation of ideas for the purpose of our study. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and uploaded to QSR NVivo Software, v.2.0. Data were processed through a 6-stage model.15 Multiple reading of transcripts and listening to audio files was undertaken in order to achieve immersion into the data. Transcripts were coded line-by-line, identifying themes in accordance with the overall aims of the article.16 The themes defined were reviewed by 4 researchers (DGL, RM, AL, and TG) and used to code the related frameworks, which some of the codes moved to other themes and nonrelevant data removed from the analysis.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

Consultation with the Health Research Authority deemed this study a service evaluation project to determine important outcomes related to standard care (Reference 60/89/81). A signed consent form was collected from parents who agreed to participate seeking their permission for the interview to be recorded and analyzed in an anonymized format.

Results

Children’s Questionnaire

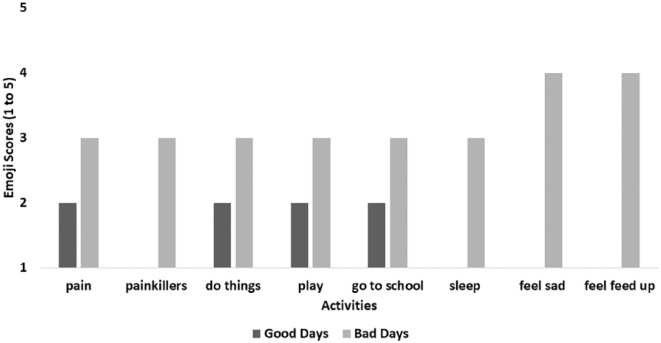

We identified 8 characteristics related to good and bad days (Figure 1): (1) presence/absence of pain; (2) use of painkillers; (3) limitations in doing things; (4) limitations in play activities; (5) limitations in going to school; (6) ability to sleep; (7) feel sad; and (8) feel feed up.

Figure 1.

Comparison between good and bad days.

Data are displayed in Table 2. Patients’ characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Among the 8 characteristics, only the “limitations in going to school” did not show statistical significance (P < .05) between good and bad days.

Table 2.

Children’s Booklet Analysisa.

| Characteristics | Good Days | Bad Days | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence/absence of pain | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .003 |

| Use of painkillers | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .024 |

| Limitations in doing things | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .014 |

| Limitations in play activities | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .004 |

| Limitations in going to school | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .071 |

| Ability to sleep | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .006 |

| Feel sad | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .002 |

| Feel feed up | Range (1-3) | Range (3-5) | .002 |

Range = emoji scores on the children booklet; where 1 is the happiest emoji and 5 is the saddest emoji.

Parents’ Interviews

Themes that emerged from analysis of the parents’ interviews are represented in this section using verbatim quotes to highlight the participants’ perspective. Four key themes emerged with a number of second-order themes contained within the key theme:

Family Perspectives and General Impact on Family Life

Lack of awareness

Parents were unaware of Perthes’ disease prior to diagnosis. They also reported difficulties in obtaining an accurate diagnosis in the early manifestation of the disease from the health care professionals they contacted.

In the beginning, we were very worried and scared, because we did not know the disease and there were not much information we could access until we got the right channels. Different people were saying different things and we were stressed and scared about this. (Patient 2, Mother)

The lack of information about the disease made the parents afraid because they could not find a good source of information and had no idea how to manage their child and the disease.

Additionally, parents felt frustrated with health care professionals in the time it took to reach a diagnosis. Perthes’ disease was often not recognized by general practitioners due to its infrequency and nonspecific initial manifestations, which can be mistaken for other nonserious conditions (ie, growing pains).

Before it was diagnosed it was a nightmare, nobody could say what it was, because nobody knew what was going on. And they were continuing to say that was a growing pain. (Patient 6, Father)

Siblings jealousy

The relationship with siblings often affected family life. Parents felt they tended to prioritize the affected child and believed that other siblings started to feel less loved and ask for more attention.

It impacted even his sister, because she was feeling that all the attention was for her brother and she got a little upset about this. (Patient 1, Mother)

Jealousy seemed to have a greater impact among younger siblings (less than 10 years old), yet older siblings seems to exhibit a protective behavior toward their sick younger sibling:

His sister is older, so she feels quite responsible for him and takes care of him.

Parental concerns for the child’s future

Parents were often concerned about how Perthes’ disease may affect their child in the long-term. Usually the concern was related to the possibility of a hip replacement in the near future, or the limitations that may be placed upon pursuing a normal life:

We are afraid she cannot do what she wants to do. Like any parents, we wish she can do whatever she wants, like do sport if she wants, or other normal things. (Patient 2, Father)

Parents were often frustrated about their child’s condition, and felt powerless about a condition that was difficult to manage:

It was just me carrying him around all the time for all the day. His dad and I, carrying him to the toilet, carrying him to the school. (Patient 5, Mother)

Parental work

Parents often reported that they had to change or quit their job in order to manage the disease, which may have significant influence on the financial status of the family.

I had to quit my job to follow him, and now I am doing just local work because it is easier to manage. (Patient 1, Mother)

As a single parent, I had to quit my job to take care of her. (Patient 9, Mother)

Impact of Perthes’ disease on Activities of Daily Living

This theme describes the impact that Perthes’ disease had on the daily life of patients and their family, such as changes in daily schedules, problems related to getting dressed unaided, or school attendance and participation in physical education or other activities. This theme has been divided into 5 “second-order themes”: (1) limitations imposed by parents; (2) impact on walking; (3) feeling of pain; (4) poor sleep quality; and (5) impact on school.

Limitations imposed by parents

Limitations and restrictions were often imposed by parents (sometimes following the advice of medical professionals) fearful of worsening the symptoms or worsening the disease.

We decided to limit her in some activities because we were afraid she could get injured. (Patient 2, Father)

Parents also described feelings of disappointment with the limitations imposed on their child:

She knows she cannot do some stuff that other children do (like jump), and she gets upset and sometimes she does not want to go to other children’s parties. (Patient 9, Mother)

Children who were very active and involved in sporting clubs were restricted:

He is a very good gymnast and dreams to go to the Olympics, but he had to stop his sport for now. (Patient 3, Mother)

Children were held back from enjoying their social time with their peers. This was a particularly important issue for younger children because they lacked the comprehension to understand why they could not do some of the same activities as their friends:

One of the problems is stopping him from playing outdoor games with his friends. It is difficult for him understand that he has to avoid jumping around or play on trampolines. (Patient 6, Mother)

Impact on walking

The impact of the disease on walking typically related to a limp, which was reported to affect most of the children:

He has a constant limp. (Patient 3, Mother)

This did not allow them to walk long distances or climb stairs, due to pain and tiredness.

Feeling of pain

Children with Perthes’ disease often reported pain, especially after long walks or long periods of outdoor activities. The pain was often localized to the knee with some exceptions, where the pain affected the whole leg. It was infrequent for parents to identify the pain localizing to the hip.

The pain is mainly in his knee. (Patient 4, Father)

Often, children decided to “deny the pain” or avoid the topic with their parents in order to be permitted to carry on with the activity they were doing in that moment:

I think he is in pain for most of the time, but because he has a high pain threshold, he does not let me know it really. But I think he is in pain a lot, for most of the time, and he has just learned how to deal with it. (Patient 3, Mother)

Poor sleep quality

Often the pain seemed to be intensified during the night. Children with Perthes’ disease reported poor sleep and needed support during the night from their parents when going to the toilet, or needed emotional support related to managing the pain. They often required painkillers to help them sleep.

During the night, we were using morphine to reduce his pain, and let him spend time in the bath, because these were the only ways we could help him. (Patient 1, Mother)

Impact on school

The impact on school was related to long absences due to pain, preparation and recovery from surgery, and the follow-up visits to health care practitioners:

He missed a lot of school, especially due to the pain. We had a teacher come to our house to help him continue studies during the 12 months after surgery. (Patient 1, Mother)

School absences affected their learning and often parents had to find solutions such as home tutoring from a private teacher during the recovery period.

Additionally, the physical conditions (limping and pain), and the limitations imposed, resulted in the children missing physical education (PE), which reduced their daily activity levels:

He had to skip PE at school. (Patient 3, Mother)

Emotional Impact of Perthes’ Disease

Perthes’ disease had a strong emotional impact on both children and their family. Broadly families could be divided into those that were “accepting of the disease” and those that were “not-accepting of the disease.”

Those who accepted the disease typically continued with life without letting the disease stop them:

He does not show me that he is upset or scared by the disease, but I think he is. It is just that his resilience is high. (Patient 3, Mother)

Those who did not accept the disease had greater frustration about their condition with more concern about the long-term implications. This group tended to be formed of older children (7-8 years old and over):

I think he is a little bit sad about his condition. He does not say very much about it. I think he is a little bit worried about the operation and I think he wants just get over it as soon as possible. (Patient 13, Mother)

Younger children (under 8 years of age) appeared less able to comprehend their situation, yet demonstrated a general sadness related activity restriction, without a real concern related to their health condition.

Perthes’ Disease and Social Relationship

Although Perthes’ disease affected the daily life of patients and family in many ways, a positive response seemed to come from social relationships with other children. Affected children seemed generally well supported by their peers:

His friends are very supportive. In his class, there are many girls that take care of him, helping him moving around with the wheelchair. And they continue to involve him in all their games and continue to come visit him at home. (Patient 1, Mother)

The support of their peers was fundamental in order to let patients manage the emotional aspect of their condition in the best way possible. In addition, the parents reported how they felt supported by the family of other children and how they tried to provide help in the managing of the disease:

The parents of his friends are very supportive too. A couple of weeks ago we had a day out with other parents, and there was a trampoline, and the other parents were saying to their children to not go on it because [my child] could not go on it. So, they were stopping their own children so that he did not feel excluded from the games.” (Patient 6, Father)

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the social, physical, and emotional impact of Perthes’ disease on affected children and their families. We show for the first time an in-depth insight into the profound effects of this disease, beyond simply a self-limiting condition affecting the immature hip. Perthes’ disease significantly affects daily life with experience of pain; inhibiting play and activities, limiting school attendance, and interfering with sleep. These factors negatively affect the social, physical, and emotional quality of life of the affected child and their wider family.

Impact on the Children

For the child’s perspective, Perthes’ disease affects children’s everyday life on both good and bad days. Pain is often the characteristic that limits most of the child’s ability to participate in normal daily activities such as playing outside or climbing the stairs on the bad days and reducing the quality of sleep, which increases the tiredness of the children during the day and negatively influences their mood. Similarly to other children with chronic illness, Perthes’ disease limits everyday tasks playing and attending school, but we also show Perthes’ disease has an emotional impact causing sadness and unhappiness especially when the child felt activity had been limited.

From the parent perspective there were similarities particular emphasis was around pain and sleep. School attendance and restrictions on activities (eg, physical education) were also an issue that caused considerable frustration. It is well-established that hospitalization in children with chronic diseases has a negative impact on child quality of life related to school absence.17,18 Nevertheless, while parents understood that the restrictions were necessary they felt more advice/guidance on physical activity was warranted as there is currently inconsistency in the information available to them.

Impact on the Parents and Siblings

Our findings suggest that the disease affects the wider family (parents and siblings), emotionally, in similar way to that of affected children. Socially, parents have to change their daily schedule and modify their life in order to deal with the disease, which is a similar finding to other studies of childhood conditions.17-21 Our data provide more in-sight and suggest that parents feel powerless in the management of the disease and demonstrate frustration with the limited amount of medical understanding of causes and treatments of Perthes’ disease. The lack of confidence in the clinical management often begins with diagnosis; clinicians generally misdiagnose Perthes’ disease in the early stages, which results in delayed diagnosis and also adverse impact on the child’s quality of life causing anxiety and worry for the parents. The paucity of and inconsistencies in available information causes uncertainty about the clinical management and constant fear that the treatment is correct, which leaves parents disappointed and lacking assurances. Seeking and taking heed of parents’ views, and the impact they have on the wider family is highly relevant for clinicians managing this condition.

Limitations

We have been able to capture the views of parents of children with Perthes’ disease during different stages of treatment/healing process supporting the data with the additional feedback of the children (through the children’s questionnaire), which is a strength of the study, although we only included patients from a single center, which induces limitations related to a small sample size and poor patients’ diversity. At the outset we intended to seek also a personal view from children through a personal narrative in the questionnaire, but most children were too young to complete this without the help of parents, which gave a strong influence on their child’s narrative. Nevertheless, the children’s questionnaire has shown useful insight into the level of particular symptoms and concerns through the use of emojis.

We demonstrate the social, physical, and emotional impact of Perthes’ disease on the life of the child and related family. Perthes’ disease is a profound childhood disability, with little high-quality evidence pertaining to its treatment nor national or international consensus. These findings add in-depth insight into the challenges caused by this disease for health care professionals involved in clinical management. Coordinated multicenter high-quality research is needed to improve the understanding of the disease, giving consideration to nonradiographic outcomes. The themes emerging from this qualitative analysis will be used to inform the development of a Core Outcome Set22,23 for use in clinical research and routine care.

Appendix A

Example Draft of the Children’s Booklet

|

HOW PERTHES AFFECTS

WHAT YOU DO AND HOW YOU FEEL |

Structure

Dear Parent,

We are very interested in how Perthes’ disease affects what your child does and how he/she feels. We have drawn up the following short booklet to help him/her to tell us, in his/her own words, how his/her bad hip affects what he/she does and how he/she feels.

Many thanks for all your help.

Introduction

This is new booklet to help us find out how your Perthes’ disease affects what you do and the way you feel. We have tried to make these questions as easy as possible to answer. Please try to answer all the questions. If you need your mum or dad to help you, that is fine.

In the tables on the next two pages, we are asking you what you can and cannot do and how you feel on a typical good day and a typical bad day. Please choose the smiley face that best matches how you feel or what you are able to do.

| Answer | Meaning |

|---|---|

|

I am very happy; I can do what I want without any pain. |

|

I am quite happy; I can do most of what I want to but with some pain. |

|

It is okay. I could do some of what I wanted with some pain which sometimes got worse. |

|

I am quite sad. I cannot most of what I want. I am in too much pain. |

|

I am very sad. The pain is very bad. I cannot do things and I normally do when I am not in so much pain. |

Example

On a good day, I was able to do everything I wanted to, play outside and with my friends.

Your answer might look like this.

On a bad day, I was unable to do what I wanted. The pain was too much. I could not go to school and just hoped some of my friends or my brother or sister might come and sit with me.

Your answer might look like this.

Now please turn to the next page of the booklet and try to tell us about the ways that your Perthes affects what you do and how you feel.

Appendix B

Parents Schedule

Introduction

Thank you for agreeing to let me interview you . . .

Gain ethical approval and for taping of the interview

The Questions

I would now like to ask you some questions about how your child’s Perthes/hip problem is affecting what he is able to do day-by-day and also how his condition is affecting you and your family.

A. First of all, can you tell me the story of his condition, from when you first noticed any problem up to now?

Note for Interviewer: Use the questions below as prompts or to follow-up on some aspect

OR

B. Use the following questions to guide/structure the interview. If you choose to do it this way:

Begin by asking the parent to just say a little about their child (eg, age, when first noticed a problem, when diagnosed . . . where now in treatment)

Get a little information about the interviewee and their family (including age and gender of any brothers or sisters)

Then, guide/structure the interview exploring/using the questions below

Role of Perthes in His Physical Activity/Activities of Daily Living

1. Have you had to change his daily schedule and what he does?

For example, getting dressed, walking, playing . . .

2. Is there any activity he can no longer do, or has had to give up?

3. Can he lift heavier things, like he used to be able to?

4. How difficult is it for him/her to push, kicking a football, lift and carry heavy objects?

5. How far is your child able to walk without struggling, limping or feeling pain?

6. Does your child limp: Some of the time? All of the time? or Not at all?

7. Is he child able to sit for a long time in a chair? Sit on the floor?

8. Is his Perthes limiting his ability to play?

9. Is he able to ride a bike or scooter or roller skates?

- 10. How does his Perthes affect how well he sleeps at night?

- When not in pain? and When in pain?

Pain Specific

Is your child in pain: Some of the time? A lot the time?

- Where is the pain?

- Knee/Hips/Both/Elsewhere—If so where?

- And what hurts the most?

- How much pain does your child experience in their hip or other joints after activity?

- On a good day? None A little Moderate Severe Very severe

- On a bad day? None A little Moderate Severe Very severe

Impact of Perthes on Pre-school/School

Has he had to miss much pre-school/school because of his Perthes, and how much?

- Was this because of:

- Pain?

- Diagnosis and treatment or other healthcare?

Can he sit cross-legged, for example, at school?

- How does his Perthes affect what he does at pre-school/school? And, for example,

- Are there limits around what he can and cannot do at pre-school/school, for example, PE class; go to the bathroom; play in playground?

- Does his Perthes limit his taking part and doing sport and games?

- Can he change directions during any games or sport or other playing, for example, at play time and in the playground?

Does your child find it hard to pay attention at school?

Social Functions

- How do your child’s friends respond to the difficulties your child is experiencing? For example,

- Do they come and sit with him or include him in their play or other activities when he is at pre-school/school?

- Do they still come round to play with him?

Is his Perthes limiting his child’s ability to take part in activities with his friends?

Has your child had to stop doing any hobbies because of hip pain?

Has your child taken up any new hobbies because of their hip pain?

Emotional Functions

- How does he feel about his hip problem? Does it make him feel:

- Sad?

- Afraid and a bit scared?

- Frustrated, angry or cross?

Does your child worry about what will happen in the future?

General Health

- How many medications/painkillers does your child have you to take daily due to their disease?

- On a good day?

- On a bad day?

- How is your child’s general health, apart from his Perthes?

- Excellent Very Good Good Fair Poor

Does your child feel tired a lot of the time?

Effect on You and Your Family, Including His Brothers and Sisters

- How is his Perthes affecting:

- You?

- Your family?

- How much of the time are you aware, and maybe change what you all do as a family, because of his Perthes?

- How much of the time?

- What did you used to do?

- What do you do now?

- How do you explain your child’s condition to others?

- Does it affect how they relate to him? Please give examples

- Do you feel supported by

- Your GP?

- Consultant?

- Other health care practitioners, for example, his physiotherapist or any specialist nurse?

Do you worry about what will happen to him in the future and the treatment of his Perthes? Please tell more.

Now we would like to ask you about your greatest hope and worst fear for your child and his Perthes and its impact on his and you and your family’s overall quality of life?

(a) My greatest hope is

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

(b) My worst fear is

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Finally, is there anything else you would like to add, for example?

How it affects his quality of life?

Anything else that particular importance or significance at the present time?

That’s it now! Thank you very much for your time and this information.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: DCP: conceived the study. DGL, DP and HJ: designed the outline of the study. RM, TG and AL: provided oversight to the design and analysis related to qualitative methodology. DGL: undertook the interviews, with the support of the qualitative oversight team. DGL: wrote the first draft of the article, and all other authors edited and approved the final draft.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Donato Giuseppe Leo is supported by a PhD fellowship from Liverpool John Moores University. Additional support has been provided by the Perthes’ Association UK. This article presents independent research supported by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) clinician scientist fellowship (to Daniel C Perry; grant number NIHR/CS/2014/14/012). All authors carried out this research independently of the funding bodies. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the UK Department of Health.

ORCID iD: Donato Giuseppe Leo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0709-3073

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0709-3073

References

- 1. Perry DC, Bruce C. Hip disorders in childhood. Surgery. 2011;29:181-186. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perry DC, Hall AJ. The epidemiology and etiology of Perthes’ disease. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;42:279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perry DC, Bruce CE, Pope D, Dangerfield P, Platt MJ, Hall A. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in the UK: geographic and temporal trends in incidence reflecting differences in degree of deprivation in childhood. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1673-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perry D, Machin D, Pope D, et al. Racial and geographic factors in the incidence of Legg-Calvé-Perthes’ disease: a systematic review. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wiig O. Perthes’ disease in Norway: a prospective study on 425 patients. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2009;80:1-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hefti F, Clarke NM. The management of Legg-Calve-Perthes’ disease: is there a consensus? A study of clinical practice preferred by the members of the European Paediatric Orthopaedic Society. J Child Orthop. 2007;1:19-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leroux J, Amara SA, Lechevallier J. Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104(1s):S107-S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moghadam MH, Moradi A, Omidi-Kashani F. Clinical outcome of femoral osteotomy in patients with Legg-Calve-Perthes’ disease. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2013;1:90-93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Onishi E, Ikeda N, Ueo T. Degenerative osteoarthritis after Perthes’ disease: a 36-years follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:701-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stulberg BN, Davis AW, Bauer TW, Levine M, Easley K. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head. A prospective randomized treatment protocol. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;268:140-151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hailer YD, Haag AC, Nilsson O. Legg-Calvé-Perthes’ disease: quality of life, physical activity, and behaviour pattern. J Paediatr Orthop. 2014;34:514-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palmen NK, Zilkens C, Rosenthal D, Krauspe R, Hefter H, Westhoff B. Post-operative quality of life in children with severe Perthes disease: differences to matched controls and correlation with clinical function. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2014;6:5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matos MA, Silva LLDS, Alves GB, de Alcantara WS, Jr, Veiga D. Necrosis of the femoral head and health-related quality of life of children and adolescents. Acta Ortop Bras. 2018;26:227-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Emerson ND, Distelberg B, Morrell HE, Williams-Reade J, Tapanes D, Montgomery S. Quality of life and school absenteeism in children with chronic illness. J Sch Nurs. 2016;32:258-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sparkes AC, Smith B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise, and -Health: From Process to Product. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramsey LT, Woods KF, Callahan LA, Menash GA, Barbeau P, Gutin B. Quality of life improvement for patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2001;66:155-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sehlo MG, Kamfar HZ. Depression and quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: the effect of social support. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fleary SA, Heffer RW. Impact of growing up with a chronically ill sibling on well siblings’ late adolescent functioning. ISRN Family Med. 2013;2013:737356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldbeck L, Melches J. Quality of life in families of children with congenital heart disease. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1915-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Malheiros CD, Lisle L, Castelar M, Sá KN, Matos MA. Hip dysfunction and quality of life in patients with sickle cell disease. Clin Paediatr (Phila). 2015;54:1354-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. COMET Initiative. Secondary COMET Initiative. http://www.comet-initiative.org/. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 23. Leo DG, Leong WY, Gambling T, et al. The outcomes of Perthes’ disease of the hip: a study protocol for the development of a core outcome set. Trials. 2018;19:374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]