Abstract

Pharmacogenomics (PGx) can be seen as a model for biomedical studies: it includes all disease areas of interest, spans in vitro studies to clinical trials, while focusing on the relationships between genes and drugs and the resulting phenotypes. This review will examine different characteristics of PGx study publications and provide examples of excellence in framing PGx questions and reporting their resulting data in a way that maximizes the knowledge that can be built upon them.

Keywords: pharmacogenomics, standards

Background

PGx studies require a multidisciplinary approach because drug targets and side effects often involve different organ systems or clinical specialties. They require expertise in many different areas both preclinical and clinical including but not limited to pharmacology, genetics, genomics, statistics, bioinformatics and medicine and standards should consider all these facets. The establishment of standards for publishing PGx studies will aid both authors and reviewers, enable easier curation to databases and knowledgebases, allow aggregation, and where appropriate, lead to the development and dissemination of evidence-based therapeutic guidelines and ease their incorporation to clinical application.

Curation involves the selection of publications that are relevant for a particular field and collates studies that can inform each other, improving their connectivity. Without curation it is very difficult to identify relevant publications to use for a study: simple searching will find a lot of false positives but also miss a large number of publications that have not used standardized terms (especially for variants) and will likely miss those with negative results unless they stated it in the abstract. Curation can lead to cross-connectivity from different disease fields linked by the same gene, for example the NUDT15 gene variants important in thiopurine PGx for inflammatory bowel disease are also informative for childhood leukemia (1, 2). PharmGKB, the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase, extracts and describes the data for each gene variant, drug and phenotype relationship as detailed in a published article (3). Curation can be a manual process, although if text is structured it can allow for natural language processing (NLP) and automated curation (4). This frees curators to focus on aggregation of knowledge, critical evaluation of evidence (which cannot be automated due to various caveats) and translation to guidelines. Efforts to aggregate can require collaboration to ensure agreement on the interpretation of impact of variants, such as those undertaken by ClinGen and ACMG (5, 6). As such, when study-findings are reported in a more standardized and structured format, aggregation of knowledge is ultimately more efficient and can enable translation of this to the clinic and therefore is a much more effective use of data rather than being kept in data silos or lost in publication tables (7).

There are several previous publications and existing standards that can be applied to the reporting of PGx results. First, a paper by McDonagh et al enumerated 10 items that lead to better curation of a study [2]. The paper focused on gene and variant based information, but also touched on defining a subject or patient population. The aim is to unambiguously identify the sites of gene variation tested, the gene, the bases measured, the strand interrogated, how these formed haplotypes when relevant, the direction of phenotype or effect they were associated with and the statistical tests used to evaluate it. The standards referred to include Human Genome Organization (HUGO) Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) for gene names and symbols, and for variants the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS)(8) or unique dbSNP identifiers such as a Reference SNP cluster ID (rs) number. HGVS has detailed information about how to describe variant locations (http://varnomen.hgvs.org/recommendations/general/) and tools for verifying them (https://variantvalidator.org).

Second, a recent article by Woodcock and Harder proposes the “10D assessment,” suggesting the following criteria should be fully described by authors publishing studies of clinical pharmacology that also apply to clinical PGx: 1. design of the study, 2. diagnoses employed, 3. drug molecules involved, 4. dosages applied, 5. data collected, 6. discussion of the findings, 7. deductions made, 8. documentation, 9. declarations, and 10. dHS (drug hypersensitivity syndrome) risk assessment (9). The article concludes that the assessment will help articles meet the standards for Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) (10) and Good Publication Practices (GPP) (11).

Third, publications reporting PGx studies should follow the FAIR principles: the FAIR principles are a commitment to make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reproducible (FAIR) (12). Briefly, FAIRness is achieved by describing studies with rich metadata that use standardized vocabularies, identifiers that are stable and maintained, protocols that are freely available and well described, and data that can be retrieved and retested. PGx studies can do this by providing unambiguous descriptions of the findings, giving appropriate metadata in their publications and where feasible submitting the data to a public repository. For example, a recent publication from the PEAR study (Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses) (13) provides the allele definitions, the rs number, the gene, the phenotype, the drugs, study size, population details, type of statistical tests and p-values in the abstract of the paper. The full text indicates that the data are available via dbGAP and an identifier is provided.

PharmGKB can help a study to be more Findable (extracted data typically has more tags than are allowed for keywords in papers), Accessible (extracted data summaries are available at no cost), Interoperable (extracted data are machine readable and tagged with the relevant ontologies and vocabularies) and show where Reproducibility has been met (Variant annotations for the same location can be compared across studies). It also helps a study to become more interconnected to other resources such as ClinVar or Gene Cards. This has resulted in 459 downloads of the Warfarin Consortium data (14), 281 licenses to download PharmGKB variant annotations, 275 licenses for relationship data and over 350 pathway requests in the first half of 2018, providing evidence for the usefulness of this information being in a highly structured data format that enables researchers to readily access it (3).

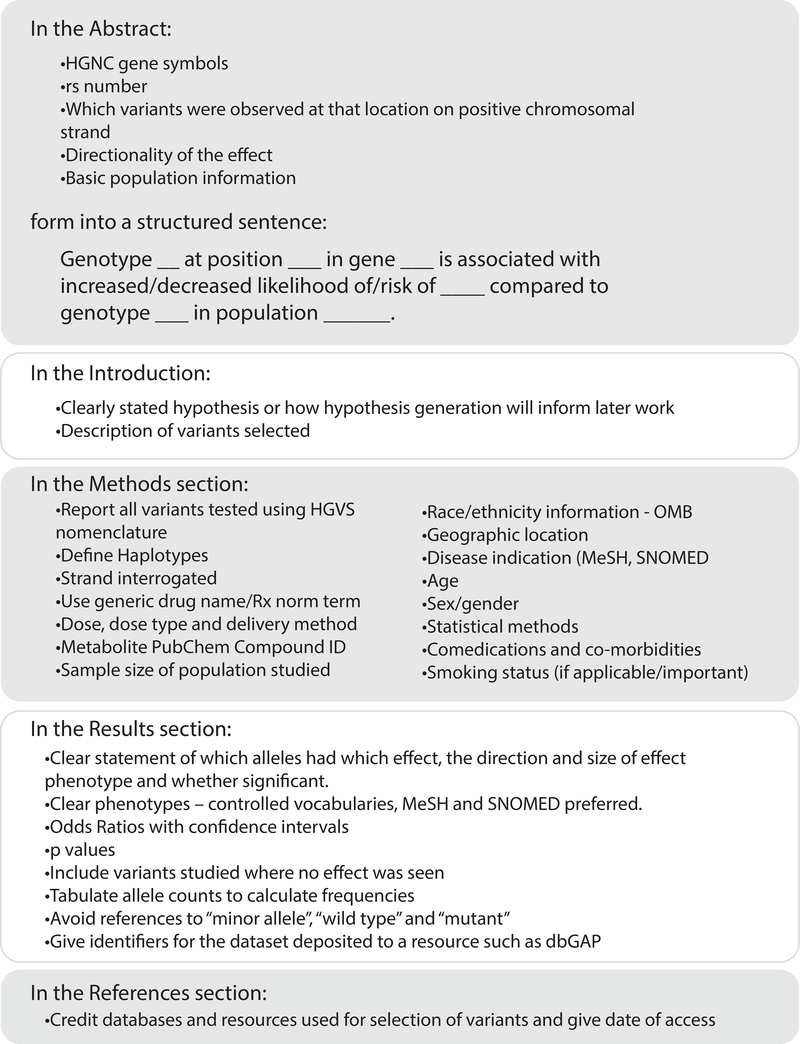

Below we discuss specific features relating to drugs, phenotypes and populations that are essential to fully describe PGx studies (summarized in Figure 1) not specifically discussed by the previously mentioned recommendations and standards.

Figure 1. Checklist for Authors of a PGx study.

Drug-related characteristics

PGx studies use a description of the drug using its generic drug name or term from Rx norm vocabulary, and give detailed dose and delivery methods. If studying drug metabolites, providing references and links to structures and database identifiers e.g. PubChem Compound IDs (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) allows for data to be incorporated into pathways in an unambiguous manner.

Some of these details have been very important when attempting to aggregate data across studies during the development of therapeutic guidelines. For example, drug and dosage and its delivery method are important to consider in the relationship between DPYD and fluoropyrimidines as there are differences when comparing test predictive ability between bolus and infusion delivery of 5FU and oral capecitabine (15). Dose and delivery method also impacts the PGx of side effects for irinotecan and UGT1A1 [PMID:27503581]. Another example is with tamoxifen and CYP2D6 and considering how study design and diagnoses and the pre-menopausal/post-menopausal status of women in the studies impacted the ability to provide genotype based guidelines (16, 17).

It is also key to provide details of co-treatments or any other drugs, vitamins or herbal products that may alter drug response or metabolism and give their doses. Treatments that are aimed at reducing side-effects of chemotherapy may change the magnitude of effect of PGx, for example filgrastim to ameliorate neutropenia or loperamide to treat diarrhea in patients receiving irinotecan (18).

Phenotype characteristics

Phenotypes for PGx studies are many and varied, ranging from in vitro studies of expressed proteins, to pharmacokinetics, to clinical studies. All need good descriptions, mappings to ontologies and controlled vocabularies, and may require some collaboration to be able to aggregate data across studies. PharmGKB uses Bioportal (https://bioportal.bioontology.org/) to map phenotypes. Bioportal has a range of ontologies in one searchable location. If you cannot find the term you are looking for or a synonym, work with a curator to map it to a simile or to have the term added to the dictionary.

Some PGx studies use a genotype to phenotype approach: a novel genomic variant is identified and then studied first using in vitro methods such as substrate assays, transport assays, and transcriptional regulation assays depending on the gene and variant location. Phenotypes for in vitro assays might be mapped to ontologies such as GO or Experimental Factor Ontology.

For phenotype to genotype studies, where an outlier phenotype is observed, individuals with that phenotype may be re-sequenced in candidate genes or genotyped by GWAS. Suitable phenotype ontologies for clinical PGx studies of adverse drug events include SNOMED-CT, MeSH, or Medra (for adverse drug events), and are all found in Bioportal. These ontologies are hierarchical with terms varying in level of granularity – it is best practice to choose the finest level of granularity/lowest level term possible. The hierarchy can allow for studies of similar phenotypes to be aggregated at a higher-level term eg. mucositis and diarrhea and vomiting might be aggregated under gastrointestinal toxicity.

PK studies can be some of most difficult to map at fine detail and aggregate across studies. In the early years of PharmGKB when housing primary data from the Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) our experience with PK studies found that even for the same drug AUCs were measured using different units, at different times, at different sites. But it is still helpful to provide this level of detail as it can be aggregated under a higher level term – eg. increased exposure. In addition we need better descriptions of drug metabolites in papers to be able to be confident of aggregating data correctly. Use of PubChem Compound or CHebi identifiers that link to the metabolite structures allows PharmGKB curators to map the metabolite to drug relationship. PharmGKB has a dictionary of standardized PK vocabulary terms for use in describing PK relationships in publications eg. clearance, trough concentration, exposure.

When studying the role of a genetic biomarker on the disposition of a medication it is important to include key drug properties in the study; these include the strength of the pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics relationship, the size of the therapeutic window, the extent of interindividual efficacy variation, the prevalence and severity of the adverse events, the pharmacology of the drug metabolites and the drug-drug interaction potential.

It is important to include all phenotypic measures including those that were the indication for drug use as well as additional diseases or lifestyle measures. Some lifestyle factors such as tobacco or caffeine use, and comorbidities have been shown to induce pheno-conversion of cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug-metabolizing enyzmes, for example, studies of HIV positive patients showed lower CYP2D6 activity than was predicted by genotype (19).

Population-based characteristics

Excellent examples of PGx studies include detailed descriptions of the population studied including but not limited to: age of subjects, indication for drug use, gender/sex, race/ethnicity, geographic population.

Large population initiatives such as the National Institutes of Health BD2K, Big Data to Knowledge, and the European Universal UPGx Project are invaluable in providing the kinds of power needed to detect the effects of multiple common variants on drug disposition. In order to translate big data to knowledge it needs to have FAIR descriptions. The formation of consortia comprising groups from multiple locations with a shared drug or drug class of interest can set internal standards to enable aggregation of data. The first successful demonstration of this mechanism was the International Warfarin PGx Consortium (14). The International Tamoxifen PGx Consortium has also reported on the involvement of CYP2D6 and clinical outcomes for tamoxifen therapy, although maybe raising more questions about the setting of standards prior to studies than answering them (17,20). Frameworks have been set for the International Consortium for Antihypertensives Pharmacogenomics Studies (21) and the International Clopidogrel Consortium (22) but data are not yet published. If the work is not part of a consortium it is even more important that a manuscript follows the FAIR standards set out above so that it can be aggregated by PharmGKB post-publication.

Small study populations can still result in impactful publications and it is still important to follow same rules for describing data. Some studies may have a small sample size because the phenotype or event is rare but the effect size is very large. For example: the relationship between HLA-B*58:01 and allopurinol-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) which was first reported in 51 patients with an odds ratio of 580.3 and p value 4.7E-24 compared to tolerant controls (23). Even aggregating across published studies to develop the CPIC guideline on HLA-B and allopurinol there were only 128 cases of SJS/TEN (24).

While the relationship between a variant and its action on drug response is not dependent on race, the likelihood of encountering a particular variant can be greater or lesser in certain racial or geographic populations and the factors that modulate the variant effects (diet, stress, environmental toxins) may also be different. This can become more apparent when trying to predict phenotype from genotype. Also it can be further complicated when predicting the effects of combinations of variants either as haplotype or across several genes used in an algorithm. For example in a study that compared CYP450 drug metabolism phenotypes in a Mexican Amerindian indigenous population and their predicted phenotypes based on genotypes, there was not good concordance (25). The authors proposed this was likely due to inadequate inclusion of variants that were more common in this population and rare in European populations. Similarly, the IWPC dosing algorithm for warfarin has been shown to be less accurate in predicting dose for African Americans compared to White or Asian individuals and additional variants that were more frequent in this population were needed to improve utility (26). The African American Cardiovascular Consortium (ACCOuNT) aims to improve the inclusion of African Americans in PGx and precision medicine []. There is still a need for greater diversity in clinical trials: anaylsis of the data submitted to the FDA in 2014 showed over 85% of participants in these trials were white (27).

One way to improve sample size and diversity of sample set is to form multisite, multinational consortia. There can still be difficulty having enough samples for replication as discussed in this pediatric asthma study (28). If combining data from different centers, intra-center controls should be undertaken e.g. comparison against the clinic’s normal therapeutic practice rather than comparing against data from all centers.

Additional characteristics

Study publications should have a stated hypothesis, or alternatively acknowledge that the study is only hypothesis-generating. If there is a stated hypothesis, there should be a well-defined statistical analysis plan, as well as basic details such as sample size and power. If there was a prespecified plan to correct for multiple testing, that should also be included.

Negative data are also valuable. Providing the detailed information of variants that were tested and not associated with phenotypes in a standardized manner so that they can be aggregated with studies with positive results can counteract bias. Additionally, publications that only report lack of association between genetic variants and drug response can be equally important.

Non-traditional PGx studies

Note that PGx studies do not always attempt to correlate a genetic variant with a drug response. While most PGx studies examine the effects of gene variants in relation to some kind of drug response, there are also studies of relevance to PGx that focus on gene variation, gene regulation or use substrates that are not drugs per se but endogenous substrates or in vitro probe molecules. All of these types of studies inform PGx but may not need all the requirements discussed in this paper for describing results in a standardized way. These publications should still apply the standards that are appropriate for the subset of PGx features.

Studies that examine variation in known pharmacogenes in diverse populations are important for identifying novel functional variants and for assessing the relative prevalence of different variants or haplotypes. For example: publications looking at CYP variation in different populations including CYP1A2 in Tibetan Chinese (29), CYP3A4 in three African populations (30), CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 in Ashkenaki Jewish population (31) and across the 1000 genomes project (32). Submission of novel variants and resequencing data to PharmVar, a new expanded resource building on the CYP nomenclature database, will aid in collection and disseminating of comprehensive nomenclature for pharmacogene variation (33). These types of papers should include detailed mapping and descriptions of which alleles were seen in which populations, gene symbol standards, and detailed population information.

Studies that examine pharmacogene regulation can aid in pathway analysis and prediction of drug-drug interactions and mechanisms of drug resistance (34). Several pharmacogenes including CYP3A4 and ABCB1, are regulated by nuclear receptor PXR coded for by NR1I2 [https://www.pharmgkb.org/vip/PA166170351/overview]. Small non-coding RNAs, miRNAs, can also modulate transcription of important pharmacogenes; a polymorphism in the 3’UTR of the DHFR gene alters a binding site for miR-24 and leads to methotrexate resistance (35). These types of papers should include detailed mapping and descriptions of which variants had which phenotype, gene symbol standards, drug standards if applicable, and phenotypes mapped to GO or Experimental Factor Ontology.

Experiments that investigate how variants contribute to gene function using probe substrates or endogenous molecules rather than clinically used drugs can give insight into how the protein functions or allow for crystallization and elucidation of protein structure. They can also help refine genotype to phenotype assignment such as the case for the CYP enzymes. Even though these studies are looking at expressed proteins and the variant protein it is still important to report the corresponding nucleotide variant allele and location and standardized gene symbol. Phenotypes can be described using GO or Experimental Factor Ontology.

Translational PGx

The development of PGx therapeutic guidelines involves international groups of investigators and stakeholders such as the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC; http://cpicpgx.org)(36), Royal Dutch Association for the Advancement of Pharmacy Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG)(37), Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety (CPNDS) and Ubiquitous Pharmacogenomics (U-PGx) (38, 39). Several university and hospital systems have reported on the application of CPIC guidelines to practice including Florida, Vanderbilt, Chicago, Mayo and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the need for standardization of testing and test result reporting (40).

To facilitate uptake of clinical implementation in health care systems, CPIC worked with a variety of stakeholders, via a modified Delphi process, to come to consensus terms to describe allele function and pharmacogenetic phenotypes (41). CPIC is implementing standardized terms to describe the functionality of variants, in particular this is important for drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters where previously a variant with lower activity might be described by different groups with multiple different terms e.g. wild-type, fully functional, and normal activity should now all be grouped under the term Normal (See paper found at https://cpicpgx.org/resources/term-standardization/). Thus, terms for describing functionality of PGx genes are: Increased function, Normal function, Decreased function, No function, Unknown function and Uncertain function. There are standardized terms for phenotypes relative to drug metabolizing enzymes including: Ultrarapid metabolizer, Rapid metabolizer, Normal metabolizer, Intermediate metabolizer, and Poor metabolizer. Terms for transporter phenotypes include: Increased function, Normal function, Decreased function, Poor function. Also standardized are terms for phenotypes for high risk based on HLA status, eg HLA-B*1502 allele and increased risk for Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis when treated with carbamazepine, where results should be reported as Positive (for high risk allele) or Negative (high risk allele not detected). Standardization of pharmacogenetic test result names would greatly facilitate interoperability and uptake across health care systems; standardization of such test results is facilitated by the uptake of SNOMED codes using these CPIC standardized terms for alleles and phenotypes (42).

An essential PGx study fills a knowledge gap

The progression of a PGx relationship goes from observational or in vitro findings, via confirmation and reinforcement of genotype-phenotype relationship, perhaps including mechanistic explanation, to guideline development resulting in the incorporation of PGx knowledge to general practice. The aggregation of knowledge (by PharmGKB) can highlight where the gaps are in a PGx story. Where the gaps are may vary in different drug-gene relationships. Many existing relationships require confirmation – or disambiguation in order to get to the position where the community can create PGx-informed guidelines.

PGx studies do not usually result in actionable information; for example there may be strong evidence for a genetic variant to influence the PK of a drug but little effect on outcomes and lacking clinical utility (e.g. NAT2) so ultimately the overall utility of the PGx relationship needs to be evaluated. Studies that confirm the relevance of PGx-implementation by comparing PGx-implementation with the relevant guidelines/genotype guided therapy to conventional dosing or prescribing comprise this step in the process. The GIFT trial compared genotype guided dosing and conventional dosing in patients receiving warfarin after hip or knee surgery and found genotype-based dosing reduced the combined risk of major bleeding, INR of 4 or greater, venous thromboembolism, or death compared to conventional dosing (43).

Finally there is also the need for studies that show implementation of PGx in general, how to go about it, overall benefits to populations and barriers to uptake. The U-PGx Network has initiatives across several European countries involved in implementation and clinical decision support (44). In the US, the IGNITE network, Implementing Genomics in Practice, is working to integrate genomic medicine into electronic medical records in a variety of healthcare settings (45). Sometimes the knowledge gap can be in provider education. Standardization of how results are presented to providers, training and clinical decision support mechanisms can help overcome this (40).

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Maria Alvarellos, Julia Barbarino and Melissa Landrum for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding:

CFT, MWC and TEK supported by NIH/NIGMS GM61374, GM 115264 and HG010135. MVR funding from CA21765, GM115279, and GM 115264.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

RBA is a stockholder in Personalis Inc. and 23andMe, and a paid advisor for Youscript. MJR is a coinventor on a pending patent application for a genomic prescribing system. SAS is a paid employee of Sema4. HH is a paid employee and stockholder in Translational Software.

References

- 1.Yang SK, Hong M, Baek J, Choi H, Zhao W, Jung Y, et al. A common missense variant in NUDT15 confers susceptibility to thiopurine-induced leukopenia. Nat Genet. 2014. September;46(9):1017–20. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4999337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang JJ, Landier W, Yang W, Liu C, Hageman L, Cheng C, et al. Inherited NUDT15 variant is a genetic determinant of mercaptopurine intolerance in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015. April 10;33(11):1235–42. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4375304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, Gong L, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012. October;92(4):414–7. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC3660037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Percha B, Altman RB. Learning the Structure of Biomedical Relationships from Unstructured Text. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015. July;11(7):e1004216 PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4517797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison SM, Dolinsky JS, Knight Johnson AE, Pesaran T, Azzariti DR, Bale S, et al. Clinical laboratories collaborate to resolve differences in variant interpretations submitted to ClinVar. Genet Med. 2017. October;19(10):1096–104. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5600649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015. May;17(5):405–24. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4544753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonagh E, Whirl-Carrillo M, Altman RB, Klein TE. Enabling the curation of your pharmacogenetic study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015. February;97(2):116–9. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4352230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, et al. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum Mutat. 2016. June;37(6):564–9. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodcock BG, Harder S. The 10-D assessment and evidence-based medicine tool for authors and peer reviewers in clinical pharmacology. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017. August;55(8):639–42. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5514613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996. January 13;312(7023):71–2. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC2349778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodcock BG, Luger V. Good publication practices in clinical pharmacology: transparency, evidence-based medicine and the 7-D assessment. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015. October;53(10):799–802. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4895874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016. March 15;3:160018 PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4792175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonough CW, Magvanjav O, Sa ACC, El Rouby NM, Dave C, Deitchman AN, et al. Genetic Variants Influencing Plasma Renin Activity in Hypertensive Patients From the PEAR Study (Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses). Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018. April;11(4):e001854 PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5901893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics C, Klein TE, Altman RB, Eriksson N, Gage BF, Kimmel SE, et al. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med. 2009. February 19;360(8):753–64. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC2722908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosmarin D, Palles C, Church D, Domingo E, Jones A, Johnstone E, et al. Genetic markers of toxicity from capecitabine and other fluorouracil-based regimens: investigation in the QUASAR2 study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2014. April 1;32(10):1031–9. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4879695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goetz MP, Sangkuhl K, Guchelaar HJ, Schwab M, Province M, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2D6 and Tamoxifen Therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018. May;103(5):770–7. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5931215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Province MA, Altman RB, Klein TE. Interpreting the CYP2D6 results from the International Tamoxifen Pharmacogenetics Consortium. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014. August;96(2):144–6. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4147833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Man FM, Goey AKL, van Schaik RHN, Mathijssen RHJ, Bins S. Individualization of Irinotecan Treatment: A Review of Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Pharmacogenetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018. October;57(10):1229–54. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC6132501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah RR, Smith RL. Addressing phenoconversion: the Achilles’ heel of personalized medicine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015. February;79(2):222–40. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4309629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Province MA, Goetz MP, Brauch H, Flockhart DA, Hebert JM, Whaley R, et al. CYP2D6 genotype and adjuvant tamoxifen: meta-analysis of heterogeneous study populations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014. February;95(2):216–27. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC3904554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Johnson JA. Hypertension pharmacogenomics: in search of personalized treatment approaches. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016. February;12(2):110–22. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4778736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergmeijer TO, Reny JL, Pakyz RE, Gong L, Lewis JP, Kim EY, et al. Genome-wide and candidate gene approaches of clopidogrel efficacy using pharmacodynamic and clinical end points-Rationale and design of the International Clopidogrel Pharmacogenomics Consortium (ICPC). Am Heart J. 2018. April;198:152–9. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5903579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, Chu CC, Lin M, Huang HP, et al. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005. March 15;102(11):4134–9. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC554812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hershfield MS, Callaghan JT, Tassaneeyakul W, Mushiroda T, Thorn CF, Klein TE, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for human leukocyte antigen-B genotype and allopurinol dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013. February;93(2):153–8. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC3564416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Andres F, Sosa-Macias M, Ramos BPL, Naranjo MG, A LL. CYP450 Genotype/Phenotype Concordance in Mexican Amerindian Indigenous Populations-Where to from Here for Global Precision Medicine? OMICS. 2017. September;21(9):509–19. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernandez W, Gamazon ER, Aquino-Michaels K, Patel S, O’Brien TJ, Harralson AF, et al. Ethnicity-specific pharmacogenetics: the case of warfarin in African Americans. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014. June;14(3):223–8. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC4016191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knepper TC, McLeod HL. When will clinical trials finally reflect diversity? Nature. 2018. May;557(7704):157–9. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mak ACY, White MJ, Eckalbar WL, Szpiech ZA, Oh SS, Pino-Yanes M, et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Pharmacogenetic Drug Response in Racially Diverse Children with Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018. June 15;197(12):1552–64. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC6006403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren Y, Liu F, Shi X, Geng T, Yuan D, Wang L, et al. Investigation of the major cytochrome P450 1A2 genetic variant in a healthy Tibetan population in China. Mol Med Rep. 2017. July;16(1):573–80. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5482113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drogemoller B, Plummer M, Korkie L, Agenbag G, Dunaiski A, Niehaus D, et al. Characterization of the genetic variation present in CYP3A4 in three South African populations. Front Genet. 2013;4:17 PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC3574981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott SA, Edelmann L, Kornreich R, Erazo M, Desnick RJ. CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 allele frequencies in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Pharmacogenomics. 2007. July;8(7):721–30. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujikura K, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Lauschke VM. Genetic variation in the human cytochrome P450 supergene family. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015. December;25(12):584–94. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaedigk A, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Miller NA, Leeder JS, Whirl-Carrillo M, Klein TE, et al. The Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium: Incorporation of the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018. March;103(3):399–401. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5836850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith RP, Lam ET, Markova S, Yee SW, Ahituv N. Pharmacogene regulatory elements: from discovery to applications. Genome Med. 2012. May 25;4(5):45 PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC3506911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra PJ, Humeniuk R, Mishra PJ, Longo-Sorbello GS, Banerjee D, Bertino JR. A miR-24 microRNA binding-site polymorphism in dihydrofolate reductase gene leads to methotrexate resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007. August 14;104(33):13513–8. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC1948927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Relling MV, Klein TE. CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium of the Pharmacogenomics Research Network. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011. March;89(3):464–7. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC3098762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swen JJ, Wilting I, de Goede AL, Grandia L, Mulder H, Touw DJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008. May;83(5):781–7. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, Muller DJ, Whirl-Carrillo M, Gong L, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014. February;15(2):209–17. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC3977533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bank PCD, Caudle KE, Swen JJ, Gammal RS, Whirl-Carrillo M, Klein TE, et al. Comparison of the Guidelines of the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018. April;103(4):599–618. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5723247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caudle KE, Keeling NJ, Klein TE, Whirl-Carrillo M, Pratt VM, Hoffman JM. Standardization can accelerate the adoption of pharmacogenomics: current status and the path forward. Pharmacogenomics. 2018. July 1;19(10):847–60. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caudle KE, Dunnenberger HM, Freimuth RR, Peterson JF, Burlison JD, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. Standardizing terms for clinical pharmacogenetic test results: consensus terms from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC). Genet Med. 2017. February;19(2):215–23. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5253119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freimuth RR, Formea CM, Hoffman JM, Matey E, Peterson JF, Boyce RD. Implementing Genomic Clinical Decision Support for Drug-Based Precision Medicine. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017. March;6(3):153–5. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5351408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gage BF, Bass AR, Lin H, Woller SC, Stevens SM, Al-Hammadi N, et al. Effect of Genotype-Guided Warfarin Dosing on Clinical Events and Anticoagulation Control Among Patients Undergoing Hip or Knee Arthroplasty: The GIFT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017. September 26;318(12):1115–24. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5818817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manson LE, van der Wouden CH, Swen JJ, Guchelaar HJ. The Ubiquitous Pharmacogenomics consortium: making effective treatment optimization accessible to every European citizen. Pharmacogenomics. 2017. July;18(11):1041–5. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volpi S, Bult CJ, Chisholm RL, Deverka PA, Ginsburg GS, Jacob HJ, et al. Research Directions in the Clinical Implementation of Pharmacogenomics: An Overview of US Programs and Projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018. May;103(5):778–86. PubMed PMID: PMCID: PMC5902434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]