Abstract

Background

Esophageal cancer (EC) is one of the malignant tumors with a poor prognosis. The early stage of EC is asymptomatic, so identification of cancer biomarkers is important for early detection and clinical practice.

Methods

In this study, we compared the protein expression profiles in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissues and adjacent normal esophageal tissues from five patients through high-resolution label-free mass spectrometry. Through bioinformatics analysis, we found the differentially expressed proteins of ESCC. To perform the rapid identification of biomarkers, we adopted a high-throughput protein identification technique of Quantitative Dot Blot (QDB). Meanwhile, the QDB results were verified by classical immunohistochemistry.

Results

In total 2297 proteins were identified, out of which 308 proteins were differentially expressed between ESCC tissues and normal tissues. By bioinformatics analysis, the four up-regulated proteins (PTMA, PAK2, PPP1CA, HMGB2) and the five down-regulated proteins (Caveolin, Integrin beta-1, Collagen alpha-2(VI), Leiomodin-1 and Vinculin) were selected and validated in ESCC by Western Blot. Furthermore, we performed the QDB and IHC analysis in 64 patients and 117 patients, respectively. The PTMA expression was up-regulated gradually along the progression of ESCC, and the PTMA expression ratio between tumor and adjacent normal tissue was significantly increased along with the progression. Therefore, we suggest that PTMA might be a potential candidate biomarker for ESCC.

Conclusion

In this study, label-free quantitative proteomics combined with QDB revealed that PTMA expression was up-regulated in ESCC tissues, and PTMA might be a potential candidate for ESCC. Since Western Blot cannot achieve rapid and high-throughput screening of mass spectrometry results, the emergence of QDB meets this demand and provides an effective method for the identification of biomarkers.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), Label-free quantitative proteomics, Prothymosin alpha (PTMA), Quantitative Dot Blot (QDB)

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is one of the malignant tumors with a 5-year survival incidence of 20.9% [1, 2]. EC is ranked as the eighth most common malignant tumor with the sixth highest mortality rate worldwide. There are two histological subtypes of EC: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adeno carcinoma (EAC). ESCC often occurs in the top or middle of the esophagus, and starts in the flat thin cells that make up the lining of the esophagus. Meanwhile, EAC is most common in the lower portion of the esophagus, and starts in the glandular cells that are responsible for the production of fluids such as mucus. China is a high-risk area for EC, and more than 90% of cases are esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [3–5]. Moreover, most of the patients exhibit locally advanced or metastatic EC at the time of being diagnosed [6, 7]. Therefore, it is urgent to discover biomarkers for early clinical diagnosis to improve survival.

Esophageal cancer biomarkers have been found in saliva, blood, and urine. Sedighi et al. showed that the serum level of Matric metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 in ESCC patients were significantly higher than in the control group, and suggested that the MMP-13 was associated with increasing ESCC invasion, lymph node involvement and decreased survival rates [8]. In saliva, the miRNAs (miR-10b*, miR-144 and miR-451) were identified up-regulated expression in EC, which possessed discriminatory ability of detecting EC [9]. Although these biomarkers contribute to the early diagnosis and prognosis of EC, the EC biomarker is still in the stage of exploration and verification, with limitations of specificity and low sensitivity.

Proteomic technologies have been applied to understand tumor pathogenesis, and to discover novel targets for cancer therapy or prognosis. Combining MS-based proteomic data with integrative bioinformatics can predict protein signal network and identify more clinical relevant molecules [10–12]. To date, quantitative proteomic methods have been applied in the study of various cancer, such as breast cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer and gastric cancer [13]. Mass spectrometric identification of differentially expressed proteins has been a highly successful approach for finding novel cancer-specific biomarkers [14]. For more than a decade, attempts have been made to uncover valid biomarkers for the diagnosis of EC. Currently, various molecules have been identified as closely correlated with ESCC, such as transgelin (TAGLN) and proteasome activator 28-beta subunit (PA28β) [15], pituitary tumor transforming gene (PTTG) [6], transglutaminase 3 (TGM) by proteomics [2]. However, the number of proteins identified was limited in these studies and they did not provide validation of the suggested biomarkers. Therefore, it is still necessary to perform further in-depth proteomics to explore novel candidate biomarkers for EC, and to validate the findings with orthogonal techniques.

Differential proteins obtained from mass spectrometry are commonly identified by Western Blot. However, it couldn’t meet the requirements for high-throughput analysis, due to the complicated processing steps and the requirements for large amount of total protein. Recently, Quantitative Dot Blot (QDB) technology developed by our team achieves high-throughput quantitative detection with the same principle of traditional Western Blot. In addition, QDB technology has the advantages of less sample consumption, short time consumption and low cost [16]. The experiment has been successfully applied to the detection of biomarker of papillary thyroid carcinoma. With its accuracy and reliability, the QDB is a very effective method for protein detection.

The aim of this study was to investigate the protein expression profiles in ESCC tissues and adjacent normal esophageal tissues with a label-free quantitative proteomics approach through nano-liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (Nano-LC–MS/MS). The differentially expressed proteins were selected and their expression trends were validated in ESCC by Western Blot, then high-throughput protein screening was achieved by QDB, and the results of QDB were verified by classical IHC experiment. This research provides a new methodological strategy for validation and identification ESCC biomarkers by combining quantitative proteomic with QDB.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

The five patients for LC/MS analysis were all male, with the average age of 61. Samples of ESCC tissues and adjacent normal esophageal tissues were taken for mass spectrometry analysis. The 64 pairs of matched ESCC and adjacent normal tissue samples for QDB were based on a clear pathological diagnosis, which included 35 men and 29 women, with an age range of 46–73 years (mean 61 years). The above samples were obtained at the Affiliated Yantai Hospital of Binzhou Medical University. All data were obtained from patient medical records. All specimens were quickly rinsed and then frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and then stored at − 80 °C until further processing. The tissue microarrays (TMA) (ES701 and ES1922) for immunohistochemistry analysis were purchased from the alenabio company, the total sample size reached 117 pairs after removing duplicates in two arrays (n = 14). This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University.

Reagents

Rabbit anti-PPP1CA (CSB-PA030161) and rabbit anti-PAK2 (CSB-PA622641DSR1HU) were purchased from CUSABIO (Wuhan, China). Rabbit anti-PTMA (YN2871) and rabbit anti-HMGB-2 (YT2187) were purchased from ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company (USA). The antibody of Caveolin (AF0126), Integrin beta-1 (AF5379), Collagen alpha-2(VI) (DF3552), Leiomodin-1 (DF12160) and Vinculin (AF5122) were purchased from Affinity Biosciences (USA). Mouse anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody (sc-32233) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Goat anti-rabbit (127,760) and goat anti-mouse (124,227) secondary antibodies were purchased from ZSGB-BIO (Beijing, China).

Sample preparation

The 5 pairs of clinical samples were homogenized and broken with lysis buffer containing 9 M Urea, 20 mM HEPES, and protease inhibitor cocktail. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C and supernatants retained. Then 20 μg of total protein were digested using the way of in-solution digestion. Firstly, the samples were reduced with 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 50 °C for 15 min, then alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) for 15 min in darkness, and then diluted 4 times with digestion buffer (50 mM NH4HCO3, pH 8.0). The proteins were digested by Trypsin with a final concentration of 5% (w/w), then incubated at 37 °C overnight. The reaction was stopped by diluting the sample 1:1 with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in acetonitrile (ACN) and Milli-Q water (1/5/94 v/v). Finally, peptides were desalted using Pierce C18 Spin Columns and dried completely in a vacuum centrifuge.

LC–MS/MS

The peptides were dissolved in 20 μL 0.5% TFA in 5% ACN and analyzed using QExactive Plus Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) coupled with the liquid chromatography system (EASY-nLC 1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). A 85-min LC gradient was applied, with a binary mobile phase system of buffer A (0.1% formic acid) and buffer B (80% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 250 nL/min. In MS analysis, peptides were loaded onto the 2 cm EASY-column precolumn (1D 100 μm, 5 μm, C18, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and eluted at a 10 cm EASY-column analytical column (1D 75 μm, 3 μm, C18, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For information data dependent analysis (DDA), full scan MS spectra were executed in the m/z range 150–2000 at a resolution of 70,000. The peptides elution was performed with a linear gradient from 4 to 100% ACN at the speed 250 nL/min in 90 min. Then the top 10 precursors were dissociated into fragmentation spectra by high collision dissociation (HCD) in positive ion mode.

Proteomic data processing

The acquired data were analyzed by using Maxquant (version 1.5.0.1) against the UniProt Homo sapiens database. The searching parameters were set as maximum 10 and 5 ppm error tolerance for the survey scan and MS/MS analysis, respectively. The enzyme was trypsin, and two missed cuts were allowed. The max number of modifications per peptide is 5. Using the Label-free quantification (LFQ), the LFQ minimum ratio count was set to 2. The FDR (false discovery rate) was set to 1% for the peptide spectrum matches (PSMs) and protein quantitation. Gene ontology and protein class analysis were performed with the PANTHER system (http://pantherdb.org/). Meanwhile, the heat map of significantly different proteins was screened by using Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus). The protein–protein interaction analysis of the differently expressed proteins was performed by STRING (https://string-db.org/).

Western blot (WB)

Tissues lysates were prepared by using highly efficient RIPA lysis buffer including PMSF (Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride). The total proteins were quantified by BCA protein assay kit and then separated by sodium dodesyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Equal amounts of protein were separated by 6%, 15% and 12% SDS-PAGE, respectively. Subsequently, proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and then blocked with TBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk. Next, the membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-PTMA (1:1000), rabbit anti-HMGB-2 (1:500), rabbit anti- PPP1CA (1:1000), rabbit anti-PAK2 (1:1000), and mouse anti-GAPDH (1:1000) antibodies at 4 °C overnight, respectively. The other five antibodies (Caveolin, Integrin beta-1, Collagen alpha-2(VI), Leiomodin-1 and Vinculin) were diluted in a ratio of 1:200. After washing, membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit (1:2000) and goat anti-mouse (1:2000) secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. The ECL system was used to detect protein expression.

QDB

The total proteins were quantified by BCA protein assay kit and then validated by Quantitative Dot Blot (QDB). Firstly, we determined the linear range of PTMA of the QDB analysis, through the testing of series of concentrations including 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 μg/μL. After that, equal amounts of protein were loaded. The sample was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min or until the membrane was completely dried. To block the plate, the QDB plate was dipped in 20% methanol. The plate was then washed with TBST, followed by 5% fat-free milk under constant shaking at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST, the QDB plate was placed in a 96 well plate and 100 μL of primary antibodies was separately added to each individual well and shaken overnight at 4 °C. After washing the QDB plate, 100 μL of the secondary antibody was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with shaking. Samples were washed with TBST and detected with the ECL substrate using a Tecan Infiniti 200 pro microplate reader. For each sample, a triplicate measurement was performed, and the average value was obtained. The relative quantitation of each PTMA protein in the lysates was then calculated.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The PTMA expression was detected by IHC in tissue microarrays (TMA) (ES701, ES1922). Firstly, the tissue microarrays were heated at 60 °C for 30 min, then deparaffinized and hydrated with xylol and gradient alcohol, respectively. Next, the antigen retrieval was accomplished by boiling the TMAs for 10 min in citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0). After cooling at room temperature, the microarrays were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at 37 °C. The samples were blocked with bovine serum albumin for 30 min at 37 °C, then the PTMA antibody (YN2871, ImmunoWay; dilution 1:50) were incubated overnight at 4 °C in a moist chamber. After using the Histostain-SP (Streptavidin–Peroxidase) kit (SP-0023) as the secondary antibody following the recommendation from the manufacture, operation manual, the samples were washed with PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.2–7.4). Finally, the immunoreactivity was detected by DAB Horseradish Peroxidase Color Development Kit.

Statistics analysis

The WB data was analyzed by means and standard deviation for four independent experiments. The other data was compared between esophageal cancer tissues and adjacent normal esophageal tissues using the two-tailed paired Student’s t test. All statistical analyses were performed by using the statistical software SPSS v20.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of differently expressed proteins

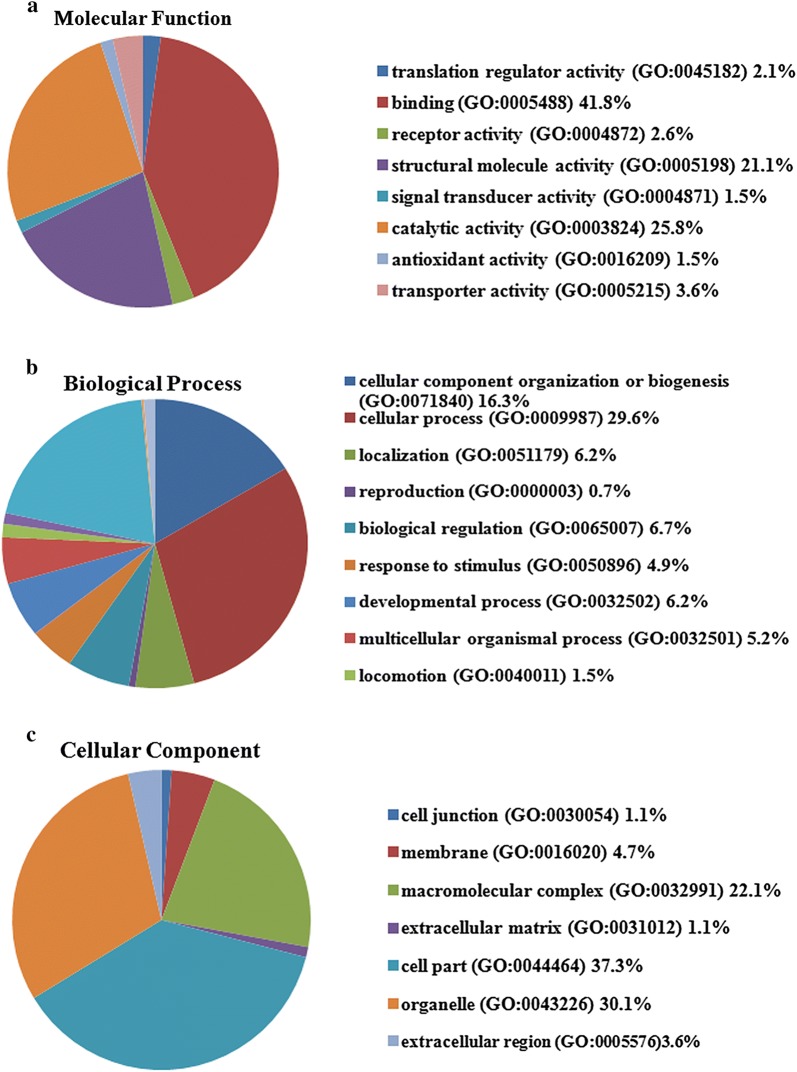

The clinical information of the five patients was summarized in Table 1. The five pairs of cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues were analyzed by label-free mass spectrometry. Total 2297 proteins were identified and 308 proteins with significant differences were selected. Among these proteins, 102 proteins were expressed only in ESCC tissues (Table 2), 155 proteins were significantly up-regulated (Table 3) and 40 proteins were down-regulated in ESCC tissues (Table 4) (P < 0.05). Using the PANTHER classification system, we analyzed the biological significance of these proteins including the cellular component, molecular function and biological process (Fig. 1). The majority of proteins belonged to cell part proteins (37.3%) and organelle proteins (30.1%), possessed the ability of binding (41.8%) and catalytic activity (25.8%), and involved in the cellular process (29.6%), metabolic process (20.2%), cellular component organization or biogenesis (16.3%).

Table 1.

The clinical features of ESCC patients for mass spectrometry

| No. | Gender | Age | Organ/anatomic site | Grade | TNM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 69 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T2N0MO |

| 2 | Male | 61 | esophagus | I | T1N0M0 |

| 3 | Male | 59 | Middle-lower esophagus | II | T1N0M0 |

| 4 | Male | 52 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 5 | Male | 64 | Middle segment of esophagus | II | T2N1M1 |

Table 2.

List of 102 proteins that were uniquely identified in ESCC tissues

| Protein IDs | Protein names |

|---|---|

| P30050 | 60S ribosomal protein L12 |

| P25788 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-3 |

| Q15254 | Prothymosin alpha |

| P12956 | X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 6 |

| O15371 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit D |

| Q59FF0 | Staphylococcal nuclease domain-containing protein 1 |

| Q06323 | Proteasome activator complex subunit 1 |

| Q15366 | Poly(rC)-binding protein 2;Poly(rC)-binding protein 3 |

| Q99729 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B |

| P62273 | 40S ribosomal protein S29 |

| O15144 | Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 2 |

| Q07955 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 |

| Q13838 | Spliceosome RNA helicase DDX39B |

| Q14666 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 17 |

| P00491 | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase |

| P13667 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A4 |

| P49755 | Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 10 |

| P34932 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 4 |

| P62750 | 60S ribosomal protein L23a |

| Q9BRL6 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 2 |

| P26583 | High mobility group protein B2 |

| O60716 | Catenin delta-1 |

| Q13151 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A0 |

| P62244 | 40S ribosomal protein S15a |

| Q8TBK5 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 |

| P39656 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyltransferase 48 kDa subunit |

| Q53GA7 | Tubulin alpha-1C chain |

| Q92598 | Heat shock protein 105 kDa |

| Q92928 | Ras-related protein Rab-1B |

| Q59F66 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX17 |

| P46782 | 40S ribosomal protein S5 |

| P78417 | Glutathione S-transferase omega-1 |

| P23526 | Adenosylhomocysteinase |

| P62081 | 40S ribosomal protein S7 |

| P11413 | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase |

| P67809 | Nuclease-sensitive element-binding protein 1 |

| Q08211 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase A |

| P17980 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 6A |

| Q59EG8 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 2 |

| P27695 | DNA-(apurinic or apyrimidinic site) lyase, mitochondrial |

| P61019 | Ras-related protein Rab-2A |

| P28066 | Proteasome subunit alpha type |

| P49588 | Alanine–tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic |

| O14818 | Proteasome subunit alpha type |

| Q8NB80 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 7 |

| Q86UE4 | Protein LYRIC |

| P83731 | 60S ribosomal protein L24 |

| B4DDM6 | Mitotic checkpoint protein BUB3 |

| P20618 | Proteasome subunit beta type |

| P31942 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H3 |

| Q13177 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PAK 2 |

| P53621 | Coatomer subunit alpha;Xenin;Proxenin |

| Q04760 | Lactoylglutathione lyase |

| Q99439 | Calponin;Calponin-2 |

| P62266 | 40S ribosomal protein S23 |

| P62857 | 40S ribosomal protein S28 |

| O43852 | Calumenin |

| Q567R6 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein |

| P22234 | Multifunctional protein ADE2 |

| P62195 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 8 |

| P98179 | RNA-binding protein 3 |

| P46781 | 40S ribosomal protein S9 |

| Q96FW1 | Ubiquitin thioesterase OTUB1 |

| O14979 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D-like |

| P51571 | Translocon-associated protein subunit delta |

| P05455 | Lupus La protein |

| Q96AE4 | Far upstream element-binding protein 1 |

| P17844 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX5 |

| P52597 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F |

| P60866 | 40S ribosomal protein S20 |

| Q13148 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| P62136 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-alpha catalytic subunit |

| P07602 | Prosaposin |

| P62633 | Cellular nucleic acid-binding protein |

| Q6FI03 | Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1 |

| P51572 | B-cell receptor-associated protein 31 |

| P27635 | 60S ribosomal protein L10 |

| Q09028 | Histone-binding protein RBBP4 |

| Q9UMS4 | Pre-mRNA-processing factor 19 |

| P62318 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein Sm D3 |

| Q15056 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4H |

| P38159 | RNA-binding motif protein, X chromosome |

| Q1KMD3 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U-like protein 2 |

| P17987 | T-complex protein 1 subunit alpha |

| Q13263 | Transcription intermediary factor 1-beta |

| P29590 | Protein PML |

| Q92499 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX1 |

| P51858 | Hepatoma-derived growth factor |

| P60468 | Protein transport protein Sec61 subunit beta |

| Q13185 | Chromobox protein homolog 3 |

| P55209 | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1 |

| P50454 | Serpin H1 |

| P42704 | Leucine-rich PPR motif-containing protein, mitochondrial |

| P61204 | ADP-ribosylation factor 1;ADP-ribosylation factor 3 |

| Q9HB71 | Calcyclin-binding protein |

| P11166 | Solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 1 |

| Q9Y265 | RuvB-like 1 |

| P62807 | Histone H2B |

| Q9UK76 | Hematological and neurological expressed 1 protein |

| P12004 | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| P43243 | Matrin-3 |

| P62333 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 10B |

Table 3.

List of 155 proteins that were overexpressed in ESCC tissues

| IDs | Log ratio | P value | Protein names |

|---|---|---|---|

| P60842 | 7.814 | 0.000 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-I |

| P23396 | 6.277 | 0.000 | 40S ribosomal protein S3 |

| P52272 | 7.623 | 0.000 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M |

| P43686 | 10.195 | 0.000 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 6B |

| P14866 | 8.871 | 0.000 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L |

| P53675 | 5.484 | 0.001 | Clathrin heavy chain;Clathrin heavy chain 1 |

| P84090 | 11.171 | 0.001 | Enhancer of rudimentary homolog |

| P22392 | 12.881 | 0.001 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase |

| Q01105 | 7.330 | 0.001 | Protein SET;Protein SETSIP |

| P84103 | 7.084 | 0.001 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 3 |

| P07900 | 9.462 | 0.001 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha |

| Q01518 | 2.076 | 0.001 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein |

| Q15233 | 22.489 | 0.001 | Non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein |

| P51149 | 7.249 | 0.001 | Ras-related protein Rab-7a |

| Q05CK9 | 9.797 | 0.001 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein Q |

| P10809 | 9.235 | 0.001 | 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial |

| P68371 | 1.935 | 0.001 | Tubulin beta-4B chain |

| P37802 | 3.333 | 0.001 | Transgelin-2 |

| P62826 | 6.962 | 0.002 | GTP-binding nuclear protein Ran |

| P25398 | 4.816 | 0.002 | 40S ribosomal protein S12 |

| P57723 | 4.611 | 0.002 | Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 |

| Q12906 | 28.577 | 0.002 | Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3 |

| P08865 | 5.309 | 0.002 | 40S ribosomal protein SA |

| P63244 | 6.237 | 0.002 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like 1 |

| P14314 | 14.510 | 0.002 | Glucosidase 2 subunit beta |

| P60900 | 9.105 | 0.002 | Proteasome subunit alpha type |

| P06748 | 12.711 | 0.002 | Nucleophosmin |

| P05388 | 8.012 | 0.002 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 |

| P46940 | 3.595 | 0.003 | Ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 |

| P61978 | 10.444 | 0.003 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K |

| P05141 | 2.807 | 0.003 | ADP/ATP translocase 2 |

| Q6LDX7 | 13.007 | 0.003 | Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor |

| Q99623 | 14.381 | 0.003 | Prohibitin-2 |

| P06733 | 2.361 | 0.003 | Alpha-enolase |

| P13639 | 5.459 | 0.003 | Elongation factor 2 |

| Q15084 | 43.388 | 0.003 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A6 |

| Q96DV6 | 3.944 | 0.003 | 40S ribosomal protein S6 |

| Q66K53 | 9.606 | 0.003 | HNRPA3 protein |

| P15880 | 4.502 | 0.003 | 40S ribosomal protein S2 |

| P39019 | 5.898 | 0.004 | 40S ribosomal protein S19 |

| P63104 | 2.043 | 0.004 | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta |

| P22626 | 6.638 | 0.004 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 |

| P30101 | 6.086 | 0.005 | Protein disulfide-isomerase |

| P25786 | 8.420 | 0.005 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-1 |

| P11940 | 12.404 | 0.006 | Polyadenylate-binding protein |

| P16401 | 4.877 | 0.006 | Histone H1.5 |

| P07237 | 5.704 | 0.006 | Protein disulfide-isomerase |

| Q16777 | 10.160 | 0.006 | Histone H2A type 2-C;Histone H2A type 2-A |

| P05386 | 5.889 | 0.006 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P1 |

| P31948 | 11.491 | 0.006 | Stress-induced-phosphoprotein 1 |

| P31946 | 2.156 | 0.007 | 14-3-3 protein beta/alpha |

| P68104 | 2.558 | 0.007 | Elongation factor 1-alpha |

| P00338 | 1.590 | 0.007 | L-lactate dehydrogenase |

| Q14103 | 6.189 | 0.007 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D0 |

| P38646 | 10.649 | 0.007 | Stress-70 protein, mitochondrial |

| P26641 | 19.766 | 0.007 | Elongation factor 1-gamma |

| O75347 | 4.168 | 0.008 | Tubulin-specific chaperone A |

| P09429 | 5.878 | 0.008 | High mobility group protein B1 |

| P62942 | 7.427 | 0.008 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase FKBP1A |

| Q9NUV1 | 7.289 | 0.008 | Cytosolic non-specific dipeptidase |

| P11021 | 7.467 | 0.008 | 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein |

| P11142 | 2.320 | 0.008 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein |

| P02533 | 5.320 | 0.008 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 14 |

| P30040 | 6.657 | 0.008 | Endoplasmic reticulum resident protein 29 |

| P50990 | 11.713 | 0.008 | T-complex protein 1 subunit theta |

| P46783 | 9.508 | 0.008 | 40S ribosomal protein S10 |

| P31943 | 14.091 | 0.008 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H |

| P19338 | 13.679 | 0.009 | Nucleolin |

| P14625 | 13.173 | 0.009 | Endoplasmin |

| Q92597 | 4.464 | 0.009 | Protein NDRG1 |

| P26599 | 19.501 | 0.009 | Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 |

| P68363 | 2.317 | 0.009 | Tubulin alpha-1B chain |

| P61604 | 9.723 | 0.009 | 10 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial |

| P08238 | 8.920 | 0.009 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta |

| Q00839 | 15.338 | 0.009 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U |

| P04843 | 64.275 | 0.009 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyltransferase subunit 1 |

| P09651 | 10.489 | 0.010 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 |

| P22314 | 3.758 | 0.010 | Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 1 |

| P30085 | 3.180 | 0.010 | UMP-CMP kinase |

| P23246 | 39.026 | 0.011 | Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich |

| P29692 | 13.726 | 0.011 | Elongation factor 1-delta |

| P27797 | 7.508 | 0.011 | Calreticulin |

| Q06830 | 1.788 | 0.011 | Peroxiredoxin-1 |

| P84243 | 2.541 | 0.012 | Histone H3 |

| P05023 | 15.342 | 0.012 | Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha-1 |

| Q14974 | 3.995 | 0.014 | Importin subunit beta-1 |

| P30154 | 2.882 | 0.014 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A |

| P49448 | 5.013 | 0.015 | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| P20700 | 14.379 | 0.015 | Lamin-B1 |

| P55072 | 6.054 | 0.016 | Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase |

| P35579 | 8.278 | 0.016 | Myosin-9 |

| P40227 | 8.241 | 0.016 | T-complex protein 1 subunit zeta |

| P13010 | 223.628 | 0.017 | X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 5 |

| Q03252 | 12.919 | 0.017 | Lamin-B2 |

| P27824 | 9.105 | 0.017 | Calnexin |

| P02545 | 1.376 | 0.017 | Prelamin-A/C;Lamin-A/C |

| P67936 | 10.102 | 0.017 | Tropomyosin alpha-4 chain |

| P04908 | 2.018 | 0.018 | Histone H2A |

| P13797 | 5.684 | 0.019 | Plastin-3 |

| P52907 | 3.377 | 0.019 | F-actin-capping protein subunit alpha-1 |

| P63241 | 4.197 | 0.019 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A |

| P62491 | 3.628 | 0.019 | Ras-related protein Rab-11A;Ras-related protein Rab-11B |

| P45880 | 2.304 | 0.020 | Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 |

| P05387 | 4.257 | 0.020 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2 |

| Q5SRT3 | 3.484 | 0.021 | Chloride intracellular channel protein |

| P07437 | 3.687 | 0.021 | Tubulin beta chain |

| P23284 | 8.401 | 0.022 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase |

| P18124 | 5.442 | 0.022 | 60S ribosomal protein L7 |

| P07355 | 1.909 | 0.022 | Annexin;Annexin A2 |

| P46777 | 12.124 | 0.023 | 60S ribosomal protein L5 |

| Q99714 | 1.923 | 0.023 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase type-2 |

| O75531 | 9.745 | 0.024 | Barrier-to-autointegration factor |

| Q14697 | 21.165 | 0.025 | Neutral alpha-glucosidase AB |

| P62263 | 6.347 | 0.025 | 40S ribosomal protein S14 |

| P0DMV9 | 2.049 | 0.026 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1B |

| P29034 | 6.458 | 0.026 | Protein S100-A2 |

| P62888 | 2.893 | 0.026 | 60S ribosomal protein L30 |

| Q6IBT3 | 23.335 | 0.027 | T-complex protein 1 subunit eta |

| P47756 | 2.818 | 0.027 | F-actin-capping protein subunit beta |

| P35222 | 7.555 | 0.028 | Catenin beta-1 |

| P07339 | 5.983 | 0.029 | Cathepsin D |

| Q86SZ7 | 4.151 | 0.029 | Proteasome activator complex subunit 2 |

| P15311 | 3.903 | 0.029 | Ezrin;Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor |

| P59665 | 4.537 | 0.029 | Neutrophil defensin 1 |

| P09960 | 5.492 | 0.030 | Leukotriene A-4 hydrolase |

| P63220 | 4.048 | 0.030 | 40S ribosomal protein S21 |

| Q16658 | 114.974 | 0.031 | Fascin |

| P07954 | 5.399 | 0.032 | Fumarate hydratase, mitochondrial |

| P54819 | 4.652 | 0.034 | Adenylate kinase 2, mitochondrial |

| P07737 | 1.223 | 0.034 | Profilin-1 |

| P63313 | 5.261 | 0.034 | Thymosin beta-10 |

| P21796 | 3.716 | 0.034 | Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 |

| P61247 | 12.449 | 0.035 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a |

| P14618 | 1.508 | 0.035 | Pyruvate kinase |

| P61626 | 4.029 | 0.036 | Lysozyme;Lysozyme C |

| Q15181 | 8.459 | 0.037 | Inorganic pyrophosphatase |

| P27348 | 3.220 | 0.037 | 14-3-3 protein theta |

| P49411 | 14.069 | 0.037 | Elongation factor Tu, mitochondrial |

| P05164 | 10.019 | 0.037 | Myeloperoxidase |

| P61160 | 5.976 | 0.038 | Actin-related protein 2 |

| Q04917 | 4.768 | 0.039 | 14-3-3 protein eta |

| P62805 | 1.761 | 0.039 | Histone H4 |

| P26373 | 3.700 | 0.040 | 60S ribosomal protein L13 |

| Q14204 | 2.799 | 0.041 | Cytoplasmic dynein 1 heavy chain 1 |

| P56537 | 7.504 | 0.041 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 6 |

| P08708 | 10.144 | 0.042 | 40S ribosomal protein S17 |

| P15153 | 2.613 | 0.042 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2 |

| P31949 | 2.100 | 0.045 | Protein S100 |

| P36952 | 6.679 | 0.046 | Serpin B5 |

| Q15149 | 4.694 | 0.047 | Plectin |

| P46779 | 6.182 | 0.048 | 60S ribosomal protein L28 |

| Q59FH0 | 5.442 | 0.048 | Histone H2A |

| P62937 | 1.778 | 0.049 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase |

| P07741 | 5.077 | 0.049 | Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| P62269 | 3.688 | 0.050 | 40S ribosomal protein S18 |

Table 4.

List of 40 proteins that were low-expressed in ESCC tissues

| IDs | Log ratio | P value | Protein names |

|---|---|---|---|

| P55268 | 0.078 | 0.001 | Laminin subunit beta-2 |

| Q13361 | 0.000 | 0.001 | Microfibrillar-associated protein 5 |

| O95682 | 0.000 | 0.001 | Tenascin-X |

| P12277 | 0.024 | 0.001 | Creatine kinase B-type |

| P20774 | 0.018 | 0.002 | Mimecan |

| P06396 | 0.501 | 0.002 | Gelsolin |

| O75106 | 0.000 | 0.002 | Membrane primary amine oxidase |

| P60660 | 0.260 | 0.002 | Myosin light polypeptide 6 |

| P51884 | 0.118 | 0.003 | Lumican |

| P35555 | 0.183 | 0.003 | Fibrillin-1 |

| Q5U0D2 | 0.081 | 0.004 | Transgelin |

| P35749 | 0.029 | 0.004 | Myosin-11 |

| P51888 | 0.032 | 0.004 | Prolargin |

| P24844 | 0.033 | 0.005 | Myosin regulatory light polypeptide 9 |

| P17661 | 0.063 | 0.005 | Desmin |

| P98160 | 0.213 | 0.006 | Basement membrane-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan core protein |

| P12109 | 0.299 | 0.006 | Collagen alpha-1(VI) chain |

| Q07507 | 0.084 | 0.006 | Dermatopontin |

| P11047 | 0.209 | 0.006 | Laminin subunit gamma-1 |

| Q6ZN40 | 0.114 | 0.006 | CDNA FLJ16459 fis |

| P18206 | 0.259 | 0.008 | Vinculin |

| Q14112 | 0.065 | 0.010 | Nidogen-2 |

| P21291 | 0.086 | 0.011 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 1 |

| P68032 | 0.312 | 0.011 | Actin, alpha cardiac muscle 1 |

| Q9NZN4 | 0.000 | 0.012 | EH domain-containing protein 2 |

| P07585 | 0.087 | 0.012 | Decorin |

| Q15746 | 0.021 | 0.014 | Myosin light chain kinase, smooth muscle |

| Q9Y490 | 0.318 | 0.015 | Talin-1 |

| P12110 | 0.223 | 0.016 | Collagen alpha-2(VI) chain |

| P21810 | 0.235 | 0.020 | Biglycan |

| Q93052 | 0.048 | 0.021 | Lipoma-preferred partner |

| P30086 | 0.507 | 0.021 | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 |

| P62736 | 0.043 | 0.022 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle |

| Q96AC1 | 0.029 | 0.023 | Fermitin family homolog 2 |

| Q6NZI2 | 0.213 | 0.025 | Polymerase I and transcript release factor |

| Q59F18 | 0.000 | 0.027 | Smoothelin isoform b variant |

| O14558 | 0.000 | 0.027 | Heat shock protein beta-6 |

| Q13642 | 0.004 | 0.028 | Four and a half LIM domains protein 1 |

| P12111 | 0.321 | 0.031 | Collagen alpha-3(VI) chain |

| P29536 | 0.000 | 0.032 | Leiomodin-1 |

| P05556 | 0.416 | 0.033 | Integrin beta-1 |

| Q15124 | 0.000 | 0.033 | Phosphoglucomutase-like protein 5 |

| P21333 | 0.213 | 0.033 | Filamin-A |

| Q53GG5 | 0.013 | 0.036 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 3 |

| P01009 | 0.429 | 0.037 | Alpha-1-antitrypsin;Short peptide from AAT |

| P43121 | 0.000 | 0.038 | Cell surface glycoprotein MUC18 |

| P52943 | 0.210 | 0.041 | Cysteine-rich protein 2 |

| P08294 | 0.000 | 0.043 | Extracellular superoxide dismutase [Cu–Zn] |

| P56539 | 0.155 | 0.043 | Caveolin |

| O15061 | 0.000 | 0.045 | Synemin |

| Q9NR12 | 0.044 | 0.047 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 7 |

Fig. 1.

Classification of identified proteins by gene ontology based on their a molecular function, b biological process and c cellular component. The analysis of proteins were performed via the PANTHER (http://pantherdb.org/)

Bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed proteins

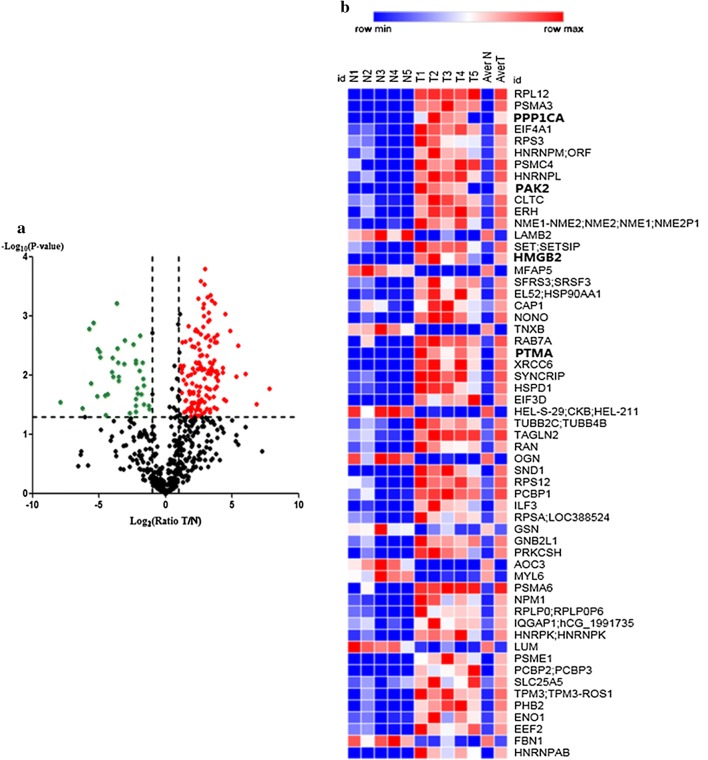

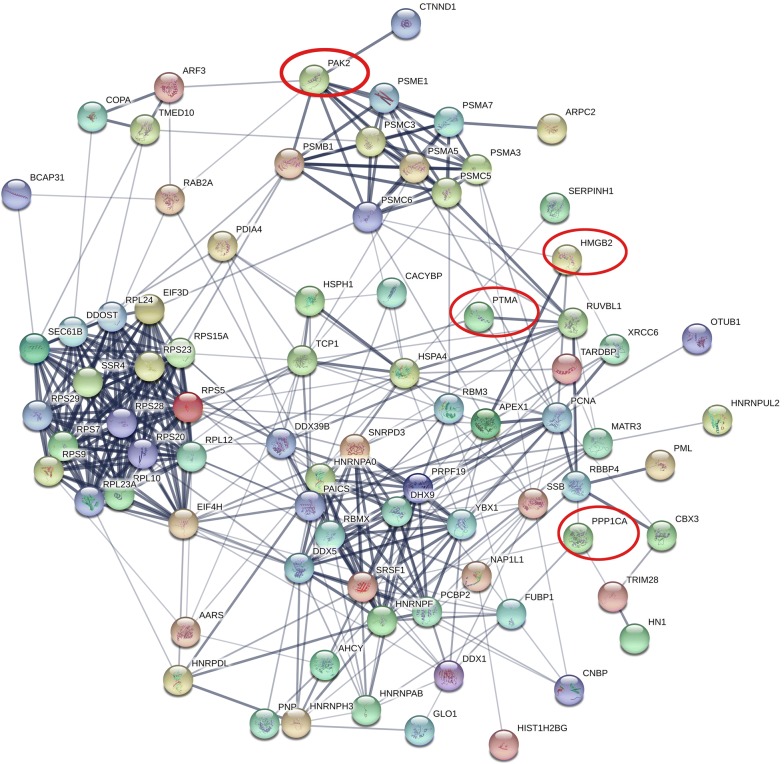

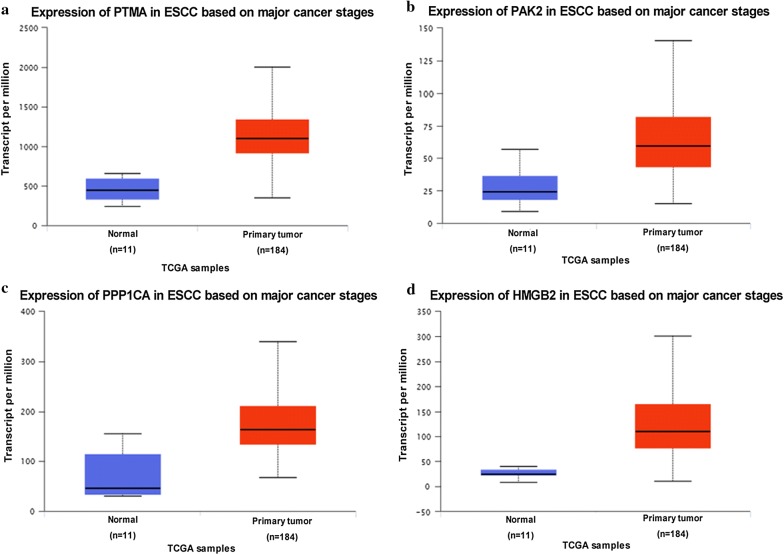

A volcano plot was generated based on the differential expression ratio and P value (Fig. 2a). Moreover, the heat map of significantly different proteins was shown in Fig. 2b by using Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus). Further protein–protein interaction analysis of the differently expressed proteins was performed by STRING, the result was shown in Fig. 3. Out of the four proteins selected for next analysis, the PPI network analysis revealed that PTMA was a valid target of c-myc transcriptional activation, while PPP1CA was involved in down-regulation of TGF-beta receptor signaling. PAK2 plays a role in apoptosis and activation of Rac, while HMGB2 is participating in chromatin regulation and retinoblastoma in cancer. Above mentioned, all these four proteins were associated with the occurrence and development of cancer. Bioinformatics analysis of the four genes from TCGA database revealed that the four genes up-regulated in gene level in EC tissue (Fig. 4). Whether these four genes can be used as biomarkers of esophageal cancer remains to be further studied.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of protein differential expression. a Volcano plot graph illustrating the differential abundant proteins in the quantitative analysis. The − log10 (P value) was plotted against the log2 (ratio cancer/normal). The red dots represented proteins up-regulated in cancer samples, green dots corresponded to proteins down-regulated in cancer samples. b The heat map of significantly different proteins was shown between cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues. The analysis was achieved by using Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus)

Fig. 3.

Protein-protein interaction network of the differently expressed proteins was identified by STRING. Four proteins were selected for further study with filled red circles (https://string-db.org/)

Fig. 4.

The expression of PTMA, PAK2, PPP1CA and HMGB2 in ESCC based on major cancer stages. In the TCGA databases, the four genes were up-regulated in EC patients (P < 0.001). (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/analysis.html)

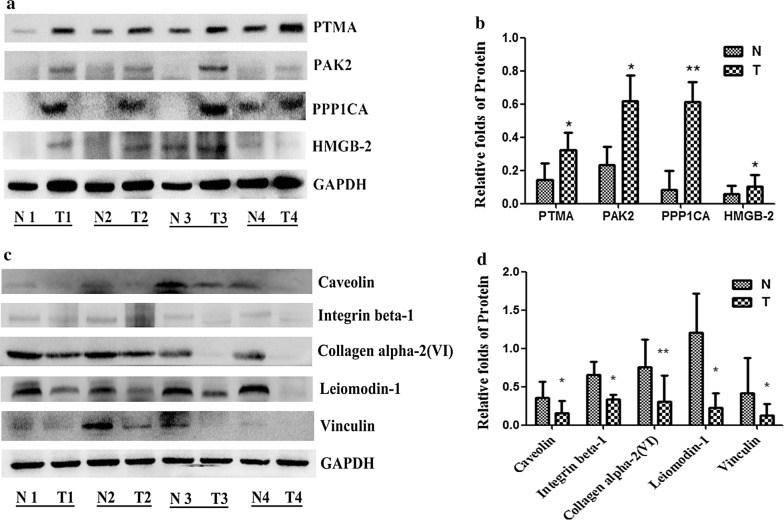

Validation of differentially expressed proteins by Western Blot

To further validate the LC–MS/MS results, we evaluated the four up-regulated proteins (PTMA, PAK2, PPP1CA, HMGB2) and the five down-regulated proteins [Caveolin, Integrin beta-1, Collagen alpha-2(VI), Leiomodin-1 and Vinculin] with Western Blot on the same samples. Compared with adjacent normal tissues, the protein expression of PTMA, PAK2, PPP1CA, HMGB2 were up-regulated (Fig. 5a, b), and the protein expression of Caveolin, Integrin beta-1, Collagen alpha-2(VI), Leiomodin-1, Vinculin were down-regulated in ESCC tissues from four pairs of samples (Fig. 5c, d). The results showed that the trends expression of these proteins were consistent with the LC–MS results.

Fig. 5.

The differentially expressed proteins were validated by Western Blot. Compared with adjacent normal tissues, the protein expression of PTMA, PAK2, PPP1CA, HMGB2 were up-regulated (a, b), and the protein expression of Caveolin, Integrin beta-1, Collagen alpha-2(VI), Leiomodin-1, Vinculin were down-regulated in ESCC tissues from four pairs of samples (c, d). Representative immunoblot images (a, c) and histograms (mean ± SD; b, d).The experiments were repeated at least three times, N represented normal tissues and T represented tumor tissues

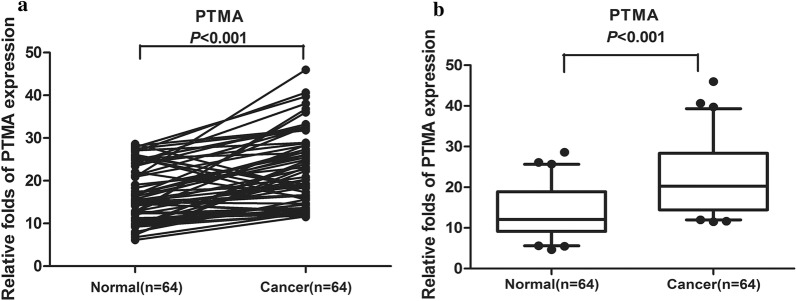

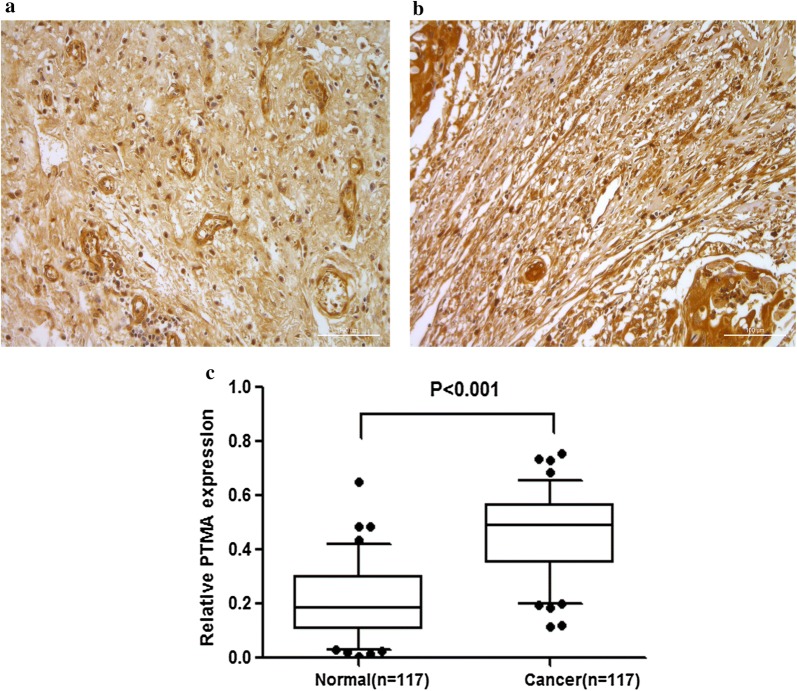

Validation of PTMA involved in ESCC by QDB and IHC

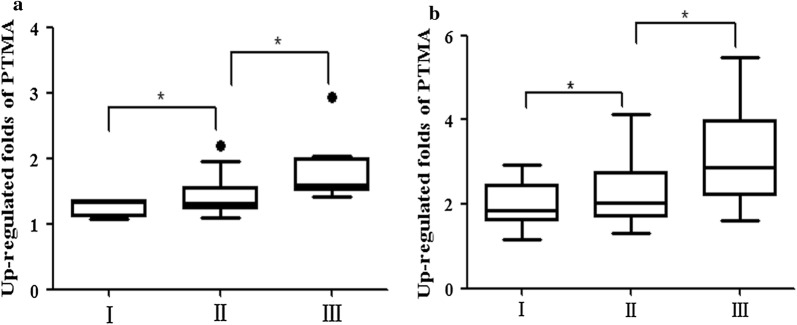

In order to validate the proteins identified by mass spectrometric, the QDB technique was applied in a larger set of samples. We collected the samples of 64 patients, and the relevant clinical information was summarized in Table 5. In the analysis of 64 patient samples, we found that 53 out of 64 esophageal cancer tissues showed higher PTMA expression than in the normal tissues (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). This trend was in accordance with the previous data. To further validate the QDB results, we performed the tissue microarray analysis by IHC. The results showed that among 117 pairs of tissues, the high expression rate of PTMA in tumor tissues was 98% (115/117). A significant overexpression of PTMA was found in tumor tissues in contrast to adjacent normal tissues (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7). The sample information in the chip is summarized in Tables 6 and 7. We further evaluated the expression pattern of PTMA with the progression, and analyzed the PTMA expression trend in the different tumor Grades. The results revealed that the PTMA expression was up-regulated gradually along the progression of ESCC (Fig. 8). The PTMA expression ratio between tumor and adjacent normal tissue was significantly increased along with the progression (P < 0.05). So we can suspect that PTMA might be participating in the development of esophageal cancer.

Table 5.

The clinical features of ESCC patients for QDB analysis

| No. | Gender | Age | Organ/anatomic site | Grade | TNM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 69 | esophagus | II | T1N0M0 |

| 2 | Male | 61 | esophagus | I | T0N0M0 |

| 3 | Male | 59 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 4 | Female | 65 | esophagus | I | T0N0M0 |

| 5 | Male | 52 | esophagus | II–III | T3N0M0 |

| 6 | Female | 73 | esophagus | I–II | T1N0M0 |

| 7 | Male | 46 | esophagus | I | T0N0M0 |

| 8 | Male | 64 | Lower segment of esophagus | II | T3N2M0 |

| 9 | Male | 57 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 10 | Male | 54 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II–III | T3N0M0 |

| 11 | Male | 72 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T3N3M0 |

| 12 | Male | 66 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T3N3M0 |

| 13 | Male | 62 | Middle-lower esophagus | II | T1N0M0 |

| 14 | Male | 60 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 15 | Female | 60 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 16 | Male | 64 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 17 | Female | 58 | Lower thoracic esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 18 | Male | 53 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 19 | Male | 65 | Lower thoracic esophagus | II–III | T3N0M0 |

| 20 | Female | 60 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | I–III | T3N0M0 |

| 21 | Male | 69 | Middle-lower esophagus | II | T3N3M0 |

| 22 | Female | 66 | esophagus | II–III | T3N2M0 |

| 23 | Female | 67 | Lower segment of esophagus | II–III | T3N3M1 |

| 24 | Male | 67 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 25 | Female | 55 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T2N1M0 |

| 26 | Female | 61 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | I–II | T1N2M0 |

| 27 | Male | 68 | esophagus | II–III | T3N2M0 |

| 28 | Female | 48 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | I–II | T3N0M0 |

| 29 | Female | 63 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T1N1M0 |

| 30 | Male | 70 | Lower segment of esophagus | II | T2N1M0 |

| 31 | Female | 59 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 32 | Female | 48 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 33 | Female | 53 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T3N2M1 |

| 34 | Female | 58 | Lower thoracic esophagus | I-II | T3N0M0 |

| 35 | Male | 62 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T2N0M0 |

| 36 | Female | 59 | esophagus | II | T3N1M1 |

| 37 | Female | 57 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 38 | Female | 57 | Lower thoracic esophagus | II | T3N1M1 |

| 39 | Female | 62 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | I–II | T3N0M0 |

| 40 | Female | 69 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II–III | T3N1M1 |

| 41 | Female | 61 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T3N2M1 |

| 42 | Female | 67 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T2N0M0 |

| 43 | Female | 47 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T2N0M0 |

| 44 | Female | 69 | Lower thoracic esophagus | III | T2N2M1 |

| 45 | Male | 66 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 46 | Male | 72 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 47 | Female | 69 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | II–III | T3N0M0 |

| 48 | Female | 73 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | I | T1N0M0 |

| 49 | Male | 62 | esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 50 | Male | 58 | esophagus | II | T2N0M0 |

| 51 | Male | 56 | Lower segment of esophagus | II | T1N0M0 |

| 52 | Male | 56 | Middle-lower esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 53 | Male | 56 | Middle-lower esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 54 | Male | 55 | esophagus | I–II | T3N0M0 |

| 55 | Female | 61 | esophagus | I–II | T3N0M0 |

| 56 | Female | 71 | Middle-lower esophagus | I–II | T1N0M0 |

| 57 | Male | 61 | esophagus | II–III | T3N3M1 |

| 58 | Male | 62 | Upper thoracic esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 59 | Male | 67 | Mid-thoracic esophagus | I | T1N0M0 |

| 60 | Male | 65 | esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 61 | Male | 58 | esophagus | II–III | T2N1M1 |

| 62 | Male | 49 | Lower segment of esophagus | I | T1N0M0 |

| 63 | Female | 66 | esophagus | III | T3N1M1 |

| 64 | Male | 70 | esophagus | I | T1N0M0 |

Fig. 6.

The relative PTMA expression was tested by QDB in ESCC and adjacent normal tissues from 64 esophageal cancer patients. a The differential expression of PTMA was shown in each pair of tissues. b The PTMA expression was up-regulated in esophageal cancer tissues from the average of 64 pairs of tissues

Fig. 7.

The relative PTMA expression was tested by IHC in ESCC and adjacent normal tissues among 117 pairs of tissues (× 200). a The expression of PTMA in adjacent normal tissues were presented. b The expression of PTMA in esophageal cancer were up-regulated. c The gray-scale analysis of immunohistochemical results (P < 0.001)

Table 6.

The 35 pairs samples in tissue microarrays (TMA) (ES701) for immunohistochemistry analysis

| No. | Gender | Age | Organ/anatomic site | Grade | TNM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 2 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 3 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 4 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 5 | Male | 50 | Esophagus | I | T3N2M0 |

| 6 | Male | 50 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 7 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 8 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 9 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 10 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 11 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 12 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 13 | Male | 59 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 14 | Male | 59 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 15 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 16 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 17 | Male | 72 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 18 | Male | 72 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 19 | Female | 60 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 20 | Female | 60 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 21 | Female | 75 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 22 | Female | 75 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 23 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 24 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 25 | Female | 54 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 26 | Female | 54 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 27 | Male | 45 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 28 | Male | 45 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 29 | Male | 52 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 30 | Male | 52 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 31 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | T3N0M0 |

| 32 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 33 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 34 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 35 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 36 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 37 | Male | 71 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 38 | Male | 71 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 39 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 40 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 41 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 42 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 43 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 44 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 45 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 46 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 47 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 48 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 49 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 50 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 51 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 52 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 53 | Male | 49 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 54 | Male | 49 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 55 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 56 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 57 | Male | 48 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 58 | Male | 48 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 59 | Female | 58 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 60 | Female | 58 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 61 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 62 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 63 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 64 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 65 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 66 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 67 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 68 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 69 | Male | 62 | Esophagus | III | T2M1N1B |

| 70 | Male | 62 | Esophagus | – | – |

Table 7.

The 96 pairs samples in tissue microarrays (TMA) (ES1922) for immunohistochemistry analysis

| No. | Gender | Age | Organ/anatomic site | Grade | TNM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 2 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 3 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 4 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 5 | Male | 52 | Esophagus | I | T1N0M0 |

| 6 | Male | 52 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 7 | Female | 66 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 8 | Female | 66 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 9 | Male | 72 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 10 | Male | 72 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 11 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 12 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 13 | Male | 66 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 14 | Male | 66 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 15 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 16 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 17 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 18 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 19 | Female | 71 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 20 | Female | 71 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 21 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 22 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 23 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 24 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 25 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 26 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 27 | Female | 63 | Esophagus | I | T2N0M0 |

| 28 | Female | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 29 | Female | 54 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 30 | Female | 54 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 31 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | I | T2N0M0 |

| 32 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 33 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 34 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 35 | Male | 49 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 36 | Male | 49 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 37 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 38 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 39 | Female | 69 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 40 | Female | 69 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 41 | Male | 49 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 42 | Male | 49 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 43 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 44 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 45 | Male | 66 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 46 | Male | 66 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 47 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 48 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 49 | Female | 58 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 50 | Female | 58 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 51 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 52 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 53 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | I | T2N0M0 |

| 54 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 55 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 56 | Female | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 57 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 58 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 59 | Female | 60 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 60 | Female | 60 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 61 | Male | 70 | Esophagus | II | T2N1M0 |

| 62 | Male | 70 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 63 | Female | 61 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 64 | Female | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 65 | Male | 54 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 66 | Male | 54 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 67 | Male | 45 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 68 | Male | 45 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 69 | Male | 75 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 70 | Male | 75 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 71 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 72 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 73 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 74 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 75 | Female | 50 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 76 | Female | 50 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 77 | Male | 72 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 78 | Male | 72 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 79 | Female | 53 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 80 | Female | 53 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 81 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 82 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 83 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 84 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 85 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 86 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 87 | Male | 51 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 88 | Male | 51 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 89 | Male | 70 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 90 | Male | 70 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 91 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 92 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 93 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 94 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 95 | Male | 48 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 96 | Male | 48 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 97 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 98 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 99 | Male | 65 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 100 | Male | 65 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 101 | Male | 71 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 102 | Male | 71 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 103 | Male | 78 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 104 | Male | 78 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 105 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 106 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 107 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 108 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 109 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 110 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 111 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 112 | Male | 63 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 113 | Female | 58 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 114 | Female | 58 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 115 | Male | 50 | Esophagus | II | T2N0M0 |

| 116 | Male | 50 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 117 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 118 | Male | 44 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 119 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 120 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 121 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 122 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 123 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 124 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 125 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | I | T3N0M0 |

| 126 | Male | 60 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 127 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 128 | Male | 58 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 129 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 130 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 131 | Male | 52 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 132 | Male | 52 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 133 | Female | 60 | Esophagus | II | T3N1M0 |

| 134 | Female | 60 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 135 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 136 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 137 | Female | 43 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 138 | Female | 43 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 139 | Male | 59 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 140 | Male | 59 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 141 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 142 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 143 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 144 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 145 | Female | 70 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 146 | Female | 70 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 147 | Male | 74 | Esophagus | III | T2N0M0 |

| 148 | Male | 74 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 149 | Male | 54 | Esophagus | I | T2N0M0 |

| 150 | Male | 54 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 151 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 152 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 153 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | I | T3N1M0 |

| 154 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 155 | Male | 48 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 156 | Male | 48 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 157 | Female | 61 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 158 | Female | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 159 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 160 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 161 | Male | 65 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 162 | Male | 65 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 163 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | III | T2N0M0 |

| 164 | Male | 55 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 165 | Female | 56 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 166 | Female | 56 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 167 | Female | 73 | Esophagus | II | T3N0M0 |

| 168 | Female | 73 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 169 | Male | 70 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 170 | Male | 70 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 171 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 172 | Male | 53 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 173 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | III | T2N0M0 |

| 174 | Male | 67 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 175 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 176 | Male | 69 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 177 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 178 | Male | 68 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 179 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 180 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 181 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | III | T3N1M0 |

| 182 | Male | 61 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 183 | Male | 59 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 184 | Male | 59 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 185 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | III | T2N0M0 |

| 186 | Male | 57 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 187 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | III | T3N0M0 |

| 188 | Male | 64 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 189 | Female | 67 | Esophagus | I | T2N0M0 |

| 190 | Female | 67 | Esophagus | – | – |

| 191 | Male | 47 | Esophagus | III | T2N0M0 |

| 192 | Male | 47 | Esophagus | – | – |

Fig. 8.

The PTMA expression was up-regulated gradually along the progression of ESCC. a The PTMA expression trend at the different Grades in QDB samples. b The PTMA expression trend at the different Grades in IHC samples. I, II, III represented ESCC Grade I, Grade II and Grade III respectively. (*P < 0.05)

Discussions

At present, most patients with esophageal cancer are diagnosed at the late and advanced stages [17]. It is thus urgent to reveal biomarkers related to the progression of esophageal cancer for early diagnosis. Recently, several biomarkers were identified in EC detection, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. For example, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and estrogen receptor (ER) were important detection factors for immunohistochemistry in EC [18–20]. In blood, the serum p53 antibody had a potential diagnostic value for EC, however, the detection was limited by its low sensitivity [21]. Therefore, we need to discover and verify more biomarker candidates for the prediction, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of esophageal cancer.

Mass spectrometry is an effective method for finding distinct molecular regulators, between normal tissues and cancer tissues [22]. In current study, we proposed a significant proteomics profiling difference including 308 proteins. However, compare to previous tissue-based ESCC proteomics study, a poor overlap of proteome profiling was noticed. There are several potential reasons. First, like many other cancers, ESCC is a heterogeneous cancer with different gene expression profiles from different populations [23]. Recently, the whole-genome sequencing revealed the diverse models of structural variations in ESCC, which indicted the biological differences among patients [24]. Therefore, the proteome variation may be a consequence of distinct molecular signatures that exist in ESCC. Another reasons could be related to the different experiment design, some of studies pooled several individual samples into a sample pooling, which would also lead to potential difference compare to our individual analysis [25]. The difference of data analysis method would be another reason too, most of the labeled-based MS approach selected the expression fold change as the major criteria. In our study, with a label-free approach, we proposed paired Student’s t-test significance as the main criteria. Such difference could lead to a different proteome profiling. The poor overlap indicated the importance of large-scale validation of biomarker. Thus we suggest in future studies, the proposed novel biomarker should be validated in a larger population no less than 100 samples. Besides TMA, our group recently developed QDB as a novel fast and accurate validation approach, which can easily validate biomarkers up to thousand samples [16].

Human prothymosin-α (PTMA) is a 109 amino acid protein belonged to the α-thymosin family, which is ubiquitously distributed in mammalian blood, tissues and especially abundant in lymphoid cells. However, its role still remains elusive. The growing evidences suggested that PTMA being an important immune mediator as well as a biomarker might eventually become a new therapeutic target or diagnostic method in several diseases such as cancer and inflammation [26]. So we focused on the possibility of PTMA as a biomarker of ESCC.

The proteomic studies show that PTMA exerts multifunction in nuclear and cytoplasmic. In proliferating cells, PTMA mainly locates in nuclear depending on the C-terminus signal sequence, but this protein can be transferred from the nucleus into the cytoplasmic during the cell extraction process [27, 28]. PTMA may mediate the chromatin activity by participated the nuclear-protein complex. In cytoplasmic, the function of PTMA is related to the state of phosphorylation, for example, the Thr7 is the only residue phosphorylated in carcinogenic lymphocytes while the Thr12 or Thr13 phosphorylated in normal lymphocytes [29, 30]. The co-immunoprecipitation experiments shows that PTMA interact with SET, ANP32A and ANP32B to form the complex, which is related to the cell proliferation, membrane trafficking, proteolytic processing and so on [31–33].

PTMA is known to play an important role in cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis and so on [34, 35]. Recent studies have confirmed that overexpression of PTMA is involved in the development of various malignancies, including colorectal, bladder, lung, and liver cancer [36–38]. In vivo tumorigenesis, the PTMA expression promotes the transplant tumor growth in mice and speeds up their death. Meanwhile, the PTMA interacts with TRIM21 directly to regulate the Nrf2 expression through p62/Keap1 signaling in human bladder cancer [39]. In the patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenosquamous cell carcinoma (ASC) and adenocarcinoma (AC) of the gallbladder, the positive expression of PTMA may be associated with the tumorigenesis, tumor progression and prognosis in gallbladder tumor. In addition, the high expression of PTMA may be as an indicator in the prevention and early diagnosis of gallbladder tumor [40]. In addition to inducing cancer, Wang et al. discovered that PTMA as a new autoantigen regulated oral submucous fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix using human proteome microarray analysis. In addition, PTMA knockdown reversed TGFβ1-induced fibrosis process through reducing the protein levels of collagen I, α-SMA and MMP [34]. However, there have been no evidences that PTMA participates in the pathogenesis of esophageal cancer.

Our mass spectrometry results showed that PTMA expression was up-regulated in ESCC tissues, and if the result was universal, it would provide a good biomarker for the diagnosis of ESCC. The traditional Western Blot is tedious, laborious and time-consuming for hundreds and thousands of large samples tests. In order to verify the results of mass spectrometry, we adopted the QDB technology invented recently, which was capable of high-throughput identification of target proteins from the perspective of biological experiments compared with Western Blot. QDB performed an affordable method for high-throughput immunoblot analysis and achieved relative or absolute quantification. In addition, the QDB needs less sample consumption, and the data can be conveniently read by a microplate reader. In HEK293 cells, the QDB successfully compared the levels of relative p65 levels between Luciferase and p65 clones in 71 pairs of samples. We have confirmed the accuracy and reliability of QDB from both cells and tissues [16]. As above mentioned, QDB is a convenient, reliable and affordable method. In our study, we confirmed that 53 out of 64 tested ESCC tissues had higher PTMA expression by the QDB, and the results were identified by classical IHC methods in 117 pairs of samples.

In this study, we included both explore experiment and validation experiment, using early and late stage samples. The results from explore experiment indicated that PTMA was overexpressed in all stages. We further evaluated the expression pattern of PTMA with the progression, and analyzed the PTMA expression trend in the different Grades. The results revealed that the PTMA expression was up-regulated gradually along the progression of ESCC, and the PTMA expression ratio between tumor and adjacent normal tissue was significantly increased along with the progression. As it is almost impossible to obtain the extreme early stage (such as the stage without any symptom, or the stage prior to Grade I), but from the trend between Grade I and III, we can suspect the expression ratio of PTMA would be a potential indicator for the progression, even in the early diagnosis.

Conclusions

In our research, we used label-free quantitative proteomics to detect differentially expressed protein profiles in ESCC tissues compared to control tissues. In total 2297 proteins were identified and 308 proteins with significant differences were selected for study. Based on in-depth bioinformatic analysis, the four up-regulated proteins [PTMA, PAK2, PPP1CA, HMGB2) and the five down-regulated proteins Caveolin, Integrin beta-1, Collagen alpha-2(VI), Leiomodin-1 and Vinculin] were selected and validated in ESCC by Western Blot. Furthermore, we performed the QDB and IHC analysis in 64 patients and 117 patients, respectively. The PTMA expression was up-regulated gradually along the progression of ESCC, and the PTMA expression ratio between tumor and adjacent normal tissue was significantly increased along with the progression. Therefore, the PTMA is suggested as a candidate biomarker for ESCC. Our research also presents a new methodological strategy for the identification and validation of novel cancer biomarkers by combining quantitative proteomic with QDB.

Authors’ contributions

JM and LW conceived the experiments; YPZ, XYQ, CCY, YZ and XXL performed the experiments; CCY, SJY, YXX and CHY collected the clinical materials; JM and CZ analyzed the protein data; WGJ, GT and JDZ conducted the statistical analysis; XRL and JB modified the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests. Jiandi Zhang declares competing interests, and he has filed patent applications. Jiandi Zhang is the founders of Yantai Zestern Biotechnique Co. LTD, a startup company with interest to commercialize the QDB technique and QDB plate.

Availability of data and materials

The data will be made available upon publication.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University (2016-37).

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670855, 31671139) for sample collection and publication charges, Key Research and Development Plan of Shandong Province (2016GSF201100, 2017GSF218113, 2018GSF118131, 2018GSF118183) for MS experiments and IHC TMA analysis, Yantai science and technology plan (2017WS102) and Doctoral fund of Shandong Natural Science Foundation (ZR2017BC063) for antibody consumption, BZMC Scientific Research Foundation (BY2017KYQD08) for QDB analysis, Scientific Research Foundation for Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars of the Education Office of Heilongjiang Province (LC2009C21) for interpretation of data, Development Plan of Traditional Chinese Medicine Science in Shandong Province (2017-237) for general lab facility.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yanping Zhu, Email: yanpingzhu1983@163.com.

Xiaoying Qi, Email: 1418599128@qq.com.

Cuicui Yu, Email: yhdyyhhf@126.com.

Shoujun Yu, Email: 84117961@qq.com.

Chao Zhang, Email: 651244893@qq.com.

Yuan Zhang, Email: 522684072@qq.com.

Xiuxiu Liu, Email: 1450625528@qq.com.

Yuxue Xu, Email: xuyuxue2320@163.com.

Chunhua Yang, Email: 284033974@qq.com.

Wenguo Jiang, Email: jiangwg@foxmail.com.

Geng Tian, Email: tiangeng@live.se.

Xuri Li, Email: slsherrylee2@gmail.com.

Jonas Bergquist, Email: jonas.bergquist@kemi.uu.se.

Jiandi Zhang, Email: Jiandi.zhang@zestern.net.

Lei Wang, Phone: +86 1504 580 6158, Email: 15045806158@163.com.

Jia Mi, Phone: +86 535 6913395, Email: jia.mi@kemi.uu.se.

References

- 1.Pennathur A, et al. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet. 2013;381(9864):400–412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(34):5598–5606. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre LA, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vizcaino AP, et al. Time trends incidence of both major histologic types of esophageal carcinomas in selected countries, 1973–1995. Int J Cancer. 2002;99(6):860–868. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran GD, et al. Prospective study of risk factors for esophageal and gastric cancers in the Linxian general population trial cohort in China. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(3):456–463. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert R, Hainaut P. The multidisciplinary management of gastrointestinal cancer. Epidemiology of oesophagogastric cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21(6):921–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuire S. World Cancer Report 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO Press, 2015. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(2):418–419. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedighi M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-13—a potential biomarker for detection and prognostic assessment of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(6):2781–2785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Z, et al. Salivary microRNAs as promising biomarkers for detection of esophageal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e57502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann M, et al. The coming age of complete, accurate, and ubiquitous proteomes. Mol Cell. 2013;49(4):583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mallick P, Kuster B. Proteomics: a pragmatic perspective. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):695–709. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu F, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of gastric cancer tissue reveals novel proteins in platelet-derived growth factor b signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):22059–22075. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurya P, et al. Proteomic approaches for serum biomarker discovery in cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(3A):1247–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roessler M, et al. Identification of PSME3 as a novel serum tumor marker for colorectal cancer by combining two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with a strictly mass spectrometry-based approach for data analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(11):2092–2101. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600118-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JY, et al. Identification of PA28beta as a potential novel biomarker in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2017;39(10):1010428317719780. doi: 10.1177/1010428317719780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian G, et al. Quantitative dot blot analysis (QDB), a versatile high throughput immunoblot method. Oncotarget. 2017;8(35):58553–58562. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Njei B, McCarty TR, Birk JW. Trends in esophageal cancer survival in United States adults from 1973 to 2009: a SEER database analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(6):1141–1146. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan C, et al. Potential biomarkers for esophageal cancer. Springerplus. 2016;5:467. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bird-Lieberman EL, et al. Population-based study reveals new risk-stratification biomarker panel for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterolog. 2012;43(4):927–935e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor is an independent prognostic factor for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:278. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, et al. Potential diagnostic value of serum p53 antibody for detecting esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi Y, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Proteomics. 2005;5(11):2960–2971. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong T, et al. An esophageal squamous cell carcinoma classification system that reveals potential targets for therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(30):49851–49860. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals diverse models of structural variations in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(2):256–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou G, et al. Biomarker discovery and verification of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using integration of SWATH/MRM. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):3793–3803. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samara P, et al. Prothymosin alpha: an alarmin and more. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1747–1760. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170518110033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Covelo G, et al. Prothymosin alpha interacts with free core histones in the nucleus of dividing cells. J Biochem. 2006;140(5):627–637. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manrow RE, et al. Nuclear targeting of prothymosin alpha. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(6):3916–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Estevez A, et al. A 180-kDa protein kinase seems to be responsible for the phosphorylation of prothymosin alpha observed in proliferating cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(16):10506–10513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barcia MG, et al. Prothymosin alpha is phosphorylated in proliferating stimulated cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(7):4704–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbeito P, et al. Prothymosin alpha interacts with SET, ANP32A and ANP32B and other cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins in proliferating cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;635:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karetsou Z, et al. Prothymosin alpha associates with the oncoprotein SET and is involved in chromatin decondensation. FEBS Lett. 2004;577(3):496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seo SB, et al. Regulation of histone acetylation and transcription by INHAT, a human cellular complex containing the set oncoprotein. Cell. 2001;104(1):119–130. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, et al. PTMA, a new identified autoantigen for oral submucous fibrosis, regulates oral submucous fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix. Oncotarget. 2017;8(43):74806–74819. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreira D, et al. The influence of phosphorylation of prothymosin alpha on its nuclear import and antiapoptotic activity. Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;91(4):265–269. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2012-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ha SY, et al. Expression of prothymosin alpha predicts early recurrence and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60326-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang M, et al. Increased expression of prothymosin-alpha, independently or combined with TP53, correlates with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(8):4867–4876. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai YS, et al. Aberrant prothymosin-alpha expression in human bladder cancer. Urology. 2009;73(1):188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai YS, et al. Loss of nuclear prothymosin-alpha expression is associated with disease progression in human superficial bladder cancer. Virchows Arch. 2014;464(6):717–724. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1578-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen K, et al. Prothymosin-alpha and parathymosin expression predicts poor prognosis in squamous and adenosquamous carcinomas of the gallbladder. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(4):4485–4494. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon publication.